Although Harriet Beecher Stowe's 1852 novel Uncle Tom's Cabin is widely credited with helping turn the nation against slavery and hastening the Civil War, the theatrical productions based on her novel have precisely the opposite reputation. Many scholars believe that despite the initial antislavery influence of George L. Aiken's 1852 dramatization, the Uncle Tom plays rapidly degraded, becoming more harmful than helpful to African Americans. The plays are also frequently blamed for turning Uncle Tom, the heroic Christian martyr of Stowe's novel, into the submissive race traitor his name connotes today.Footnote 1 The “process of vulgarization” that afflicted the Uncle Tom's Cabin dramas is said to have begun almost immediately, with the 1852 premiere of H. J. Conway's adaptation.Footnote 2 Today, Conway's version is widely designated a pro-Southern or compromise dramatization of Uncle Tom's Cabin, especially compared to Aiken's influential adaptation, which is considered to have the strongest antislavery message of the many adaptations and to be the most faithful to Stowe's novel.

The long-lasting critical judgment of the Conway play as a work that divested Uncle Tom's Cabin of its antislavery politics begins with a 1947 book by an amateur historian and enthusiast of the Uncle Tom's Cabin stage shows. Harry Birdoff's The World's Greatest Hit is a celebratory chronicle of the history of Uncle Tom's Cabin onstage, from its earliest inceptions in the 1850s to the touring “Tom troupes” that traveled throughout the nation into the 1930s and beyond.Footnote 3 In Birdoff's telling, dramatizations of Uncle Tom's Cabin quickly shed the serious political implications of Stowe's novel. Although his book has clear scholarly limitations, including frequent “creative reconstructions of the past,” it has been and continues to be cited, often extensively, in virtually every work of scholarship on dramatizations of Uncle Tom's Cabin.Footnote 4The World's Greatest Hit is enthusiastically written and offers plenty of the kinds of juicy historical anecdote that scholars love. More practically, it remains the only book-length study of the Uncle Tom's Cabin shows. While a new and comprehensive assessment of the theatrical history of Uncle Tom's Cabin is certainly overdue, the place to begin is with H. J. Conway's much-maligned adaptation. When Conway's version is viewed in light of fresh empirical research that undermines existing readings of the play's creation, advertisement, and reception, it loses its pro-South or conciliatory designation and instead becomes an agent of antislavery sentiment that was in some ways more radical than Stowe's novel. Not only does Conway's play advance an antislavery argument that urgently calls the nation to match its laws and practices to its values, it also imagines freed slaves as part of the nation's future. Its presence on the American stage suggests the progressive politics that can be found in nineteenth-century popular theatre.

Selling Uncle Tom's Cabin on the American Stage

Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote Uncle Tom's Cabin out of a passionate desire to end slavery, and although she hoped to make some money from it—her husband, Calvin Stowe, according to their son Charles, “often expressed the hope that she would make money enough by the story to buy a new silk dress”Footnote 5—she never expected it to become such a sensation. It is hard to imagine how she could have expected anything close to the “Uncle Tom mania” that quickly sprang up in the United States and around the world.Footnote 6 Until Uncle Tom's Cabin, no American book had found such international popularity and acclaim, and it is unlikely that anyone would have predicted that an antislavery novel written by the 41-year-old wife of a theologian would be the first. Stowe's novel was the best-selling book of the nineteenth century after the Bible; it sold 300,000 copies in the United States in its first year alone and one million copies between the United States and Britain. But the readership of the novel paled in comparison to the number of Americans who went to the theatre to see one (and often more) of the many dramatizations of Stowe's novel, which were performed virtually without pause from 1852 to the 1930s and have appeared intermittently ever since. Thomas Gossett has estimated that as many as fifty Americans attended stage versions of Uncle Tom's Cabin for every one who read the novel.Footnote 7

Unlike the moral and political impulses behind Stowe's novel, however, the many dramatizations of Uncle Tom's Cabin were, as Sarah Meer rightly suggests, “commercial before they were political,” created by theatre people who saw the spectacular success of Stowe's novel and wanted to share in the profits.Footnote 8 Aiken's adaptation of Uncle Tom's Cabin, for example, was commissioned by George C. Howard as a vehicle for his young daughter, Cordelia, who played Eva—a circumstance that probably heightened Eva's central role in the resulting sentimental drama. Little Cordelia retired from the stage when she wasn't so little anymore, but Howard was able to turn Uncle Tom's Cabin into the backbone of lifelong careers for him and his wife: Howard played the role of St. Clare for several decades, and his wife, Caroline, was particularly well known for her Topsy. (Like all American actors of that era who played black characters, whether comic minstrel types or Shakespeare's Othello, Caroline Howard blacked up for the role.) Although George C. Howard claimed to have antislavery sympathies, he was also open to amending his Uncle Tom's Cabin for a Southern audience. In 1855, a Baltimore theatre manager asked Howard if his play could “be so adapted and softened in its style, without losing much of its interest, as to be made not only acceptable, but telling to a Baltimore audience[?]” Could the “very objectionable speeches and situations . . . be modified in their tone and spirit, without materially weakening the plot and character of the play[?]”Footnote 9 Evidently the two were able to come to a compromise: Howard brought his troupe to Baltimore the next month.

H. J. Conway's script was also a commercial venture; it was commissioned by Moses Kimball, manager of the Boston Museum theatre. Although Kimball was an opponent of slavery, Conway's correspondence with him during the writing of his Uncle Tom's Cabin adaptation included no discussion of the play's politics. Instead, it focused on the playwright's determined struggle to construct a cohesive dramatic arc from a novel with multiple narrative threads. (“I find much difficulty in handling it dramatically, but there is no such word as ‘fail’ in my vocabulary,” he wrote.)Footnote 10 The Boston Museum's stage manager, William Henry Sedley Smith (a struggling alcoholic who was the author of the era's popular temperance play The Drunkard), was a great admirer of politicians Daniel Webster and Henry Clay, both of whom favored compromise about the slavery issue rather than abolition. But he was far more concerned with house profits than with the play's politics. “This has been the greatest week ever known in the Boston Museum,” Smith wrote in his diary a week into the show's 1852 run. “Receipts a good deal over three thousand dollars! So much for Uncle Tom. The piece is certainly done gloriously. I hardly need write here my utter detestation of its political bearing.”Footnote 11 The play's unprecedented revenue ultimately trumped any concerns about its politics. By January, with its 73rd performance, Smith was delighted to report that the show had been so popular that he had “turned scores away. Wonderful piece!”Footnote 12 Perhaps the play even managed to shift his own political stance. Despite his earlier admiration of compromise politicians, in 1854, he recorded his deep disapproval of the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which opened the door for the spread of slavery into the nation's new territories: “The infamous Nebraska Bill pass'd the Senate 34 to 14! Shameful.”Footnote 13

Audiences generally greeted the Boston production of Conway's drama as a faithful adaptation of Stowe's antislavery novel, though it did receive one mixed review from an antislavery critic, who found that “the slang conversation of the negroes and the Ethiopian ‘break-downs,’ seemed to seriously mar the otherwise favorable impression the drama was producing.”Footnote 14 Abolitionist Parker Pillsbury reported that the museum was “almost literally crammed nearly an hour before the rising of the curtain.” Its five-hundred-person audience loudly applauded the play's “most radical sentiments” as well as the moment when the slave catchers who were chasing George Harris and Eliza were shot dead.Footnote 15 Pillsbury was delighted that the theatre was standing up against slavery even though Protestant churches would not. It was heartening to witness an audience cheering the black man and woman who were breaking the law rather than the white men who were pursuing their legal property. “Vive la agitation! [sic]” he concluded. A proslavery spectator also recognized the power of the Boston Museum's production of Uncle Tom's Cabin to turn audiences against slavery; he condemned it as “treason,” and wrote that it was “an overcolored description of the evils of slavery. It conveys wrong impressions of life at the South, and is a slander upon the slaveholding community.”Footnote 16

Given the astonishing profits that the Conway script brought to Moses Kimball's Boston Museum, there is little reason to think that the showman Phineas T. Barnum made significant changes to the play when he staged it at his American Museum in New York City.Footnote 17 Barnum, who collaborated with his longtime friend Kimball throughout his career, was sympathetic to many reform movements, including temperance (he was a fervent teetotaler), women's rights, and abolition and black civil rights.Footnote 18 But as he was the first to admit, his primary interest was making money, not political statements, though the latter could at times aid the former. In the summer of 1853, Aiken's adaptation of Uncle Tom's Cabin was already drawing hordes every night to Purdy's National Theatre, just a few blocks from Barnum's American Museum. Barnum realized that mounting a New York production of Conway's play could divert some of A. H. Purdy's profits into his own pocket.

But the Conway adaptation seemed to make a very different political impression in New York than it had in Boston. An early review in Horace Greeley's antislavery newspaper the New York Tribune charged the drama and its author with completely obscuring the antislavery message of Stowe's novel.Footnote 19 A similar objection appeared on 16 December 1853 in William Lloyd Garrison's abolitionist newspaper The Liberator.Footnote 20 Moreover, Barnum's advertisement for his production seemed to confirm the play's retreat from the novel's antislavery politics.Footnote 21 These three documents have been the central source of scholars' interpretations of the Conway play as making substantial concessions to Southerners by offering a positive portrayal of slavery. But a return to the archives, to the full text and context of these documents, seriously challenges such readings of Conway's version of Uncle Tom's Cabin. It also offers a new lens through which to read the Conway script, as I do later in this essay.

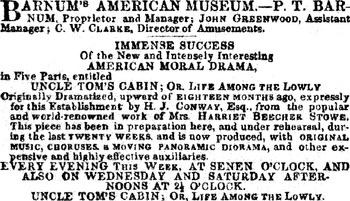

A closer look at Barnum's full advertisement and its timing (it first appeared the day after the unfavorable Tribune review) suggests that it was a defensive maneuver rather than a political manifesto and that Barnum did in fact present his production as an antislavery work. After all, that was what had sold all those books and drawn all those audiences to the theatre. When Barnum's production of Conway's Uncle Tom's Cabin opened at the American Museum on 7 November 1853, Barnum began daily advertisements for the production in several New York newspapers, including the New York Times and the New York Tribune. For more than a week, the showman's ads were more or less identical: they made no reference to the production's politics, instead emphasizing its continuity with Stowe's novel and its magnificent scenery. Dramatized “from the popular and world-renowned work of Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe,” this production, the ads proclaimed, featured “original music, choruses, a moving panoramic diorama, and other expensive and highly effective auxiliaries”Footnote 22 (Fig. 1). Barnum was fully aware that his production did not follow Stowe's novel exactly, but he framed its departures as dramatic interventions rather than political ones. An additional advertisement in the New York Times that was printed on 12 November featured a letter from “truth” that described the play's amendments to the novel as enhancements. “truth” wrote that the production “has departed, in some measure, from the thread of the original work, in order to adhere to the unities and produce a telling plot” and added that the extra comic portions brought further interest to “what would otherwise be the dull parts of the narrative.”Footnote 23 Despite the comic relief, the play was ultimately meant to touch the heart, “truth” claimed: it was, “on the whole, a chaste and superior production, and he must have a hard heart and lamentable taste who can witness it without tears and without approbation.”

Figure 1. Classified advertisement for Barnum's American Museum, New York Tribune, 10 November 1853.

Politics suddenly became an issue one week into the show's run, with the publication of the aforementioned Tribune review. In addition to describing Barnum's production as having “destroy[ed] the point and moral of the story” and transformed Stowe's novel into “a play to which no apologist for Slavery could object,” the Tribune claimed the play had been “degraded to a mere burlesque negro performance.”Footnote 24 The worst parts were the weak characterizations (especially of Eva and Topsy); the light tone of the slave auction scene, which ended with a “ridiculous squabble” that transformed any moral seriousness into comedy; and the ending, in which, instead of dying, “Uncle Tom is allowed to run with flying colors, after having had a pretty good time, so far as is seen or represented, throughout his entire pilgrimage.”Footnote 25 This last was perhaps an exaggeration. In the Conway script's final act, Legree strikes Tom with a whip and the stage directions call for the removal of Tom's jacket, “showing to audience his back very bloody.”Footnote 26 But at the end of the play, Legree is dead, killed by supernatural forces, and Tom, his wife, and his children are alive and free. Rather than dying and ascending to heaven with Little Eva, Tom receives a gift of money for “a lot of good land down East” in New England that will “be honored by having erected on it Uncle Tom's cabin.”Footnote 27 There, he and his family will live in freedom.

The day after the Tribune's critique of his Uncle Tom's Cabin, Barnum radically changed his advertisement to address the issue of the play's politics, which the Tribune's review had highlighted (Fig. 2). The timing of this overhaul suggests that it should be read not as a bold and uninvited appeal to proslavery audiences but as a defense against the Tribune's disapproval. Moreover, the opening words of the advertisement insisted that the play was an antislavery work: it offered a true picture of the horrors of slavery, “represent[ing] Southern Negro slavery as it is, Exposing all its abhorrent deformities, its cruelties and barbarities.”Footnote 28 And, quoting Othello's final speech, in which he asks all who are present to write about him as he is, with neither excuse nor cruelty, Barnum's ad maintained that his play did “nothing extenuate [n]or set down aught in malice.” This allusion situated the play appearing at Barnum's American Museum in Othello's more serious blackface tradition.

Figure 2. Classified advertisement for Barnum's American Museum, New York Tribune, 17 November 1853.

Barnum did, however, concede that there was a difference between his version and the one at the National, which the Tribune evidently preferred. In the advertisement he asserted that the difference between the two plays was not that his version made light of slavery but that it offered a different—and, according to Barnum, more realistic—representation of the slaves in the play. Critiquing the notion that black slaves could match and even exceed whites in intelligence, morality, and respectability, Barnum's ad insisted that his production “does not foolishly and unjustly elevate the negro above the white man in intellect or morals. It exhibits a true picture of Negro life in the South, instead of absurdly representing the ignorant slave as possessed of all the polish of the drawing-room, and the refinement of the educated whites.” Barnum's advertisement further insisted that his play's happy ending had nothing to do with politics; this change to Stowe's plot was done simply to accommodate the “dramatic taste” of “having Virtue triumphant at last.” A letter to the editor published the next day defended Barnum's production and supported the happy ending: “Down-trodden virtue may possibly present a picture sufficiently striking for the closing chapter of a novel, but to hold up vice as triumphant in the denouement of a moral drama, is scarcely the way, you will admit, to deter the youthful fancy from contemplating crime with indifference, if not satisfaction.”Footnote 29 For this theatregoer, the movement from page to stage demanded a different set of conventions. Heavenly reward might be a satisfying conclusion to a novel, but a theatrical audience needed to see vice punished on earth.

But what, then, of an account of the Conway Uncle Tom's Cabin published in The Liberator, which charged that Barnum's New York City production “omits all that strikes at the slave system, and has so shaped his drama as to make it quite an agreeable thing to be a slave”?Footnote 30 Harry Birdoff cites this in support of his proslavery reading of the Conway play, and since then many scholars have repeated the quotation, some even describing it as Garrison's own opinion. A return to the original document, however, reveals that the report on the Barnum production is not an original critique by Garrison or the Liberator but rather a reprint of a brief mention in Ohio's antislavery Ashtabula Sentinel. In fact, Garrison had seen and enjoyed both the Conway version at the Boston Museum and the Aiken play at Purdy's National Theatre in New York. Garrison wrote to his wife that in some respects he preferred the Conway version. (Unfortunately, the letter is brief and doesn't explain why.)Footnote 31

The process by which this judgment of Conway's Uncle Tom's Cabin became attributed to William Lloyd Garrison is something like a game of telephone, and it all begins with the New York Tribune's disapproving 15 November review and, a couple of days later, the publication of a letter to the editor defending Barnum's amendments as dramatically necessary. In an editorial accompanying the letter, the Tribune elaborated on its objections to Barnum's production. It was fine for a dramatist adapting a novel to change a few things, the paper conceded, but “Mr. Barnum's dramatist has devoted himself to getting the drift and purpose of Mrs. Stowe as much out of sight as possible.”Footnote 32 The three chief problems with Conway's script were that he gave St. Clare “the current canting apology for slavery” that English laborers were as bad off as Southern slaves (no matter that this line actually comes from Stowe's novel), that he concludes the auction scene in “farcical confusion,” and “finally, by way of ‘moral effect,’ he accomplishes a triumph of virtue by crowning the generally comfortable career of Uncle Tom with long life and earthly felicity.” One week later, a Sandusky, Ohio, antislavery newspaper, the Daily Commercial Register, repeated, in shortened format, the three objections to the Barnum production that the Tribune editorial of 17 November had brought up, closely echoing its language and using a passive construction that suggests it was not a firsthand account:

It is said to misrepresent the spirit of Mrs. Stowe's work by attempting an apology for Slavery. In the scene representing a Slave auction the dramatizer makes it break up in farcical confusion, and instead of Uncle Tom dying by the hands of Legree, he is crowned with a long life of earthly felicity, to show the triumph of virtue and to produce a “moral effect.”Footnote 33

A few days later, on 24 November, the Ashtabula Sentinel offered a similar but amplified report on Barnum's production, charging that it “omits all that strikes at the slave system” and “make[s] it quite an agreeable thing to be a slave.”Footnote 34 When The Liberator reprinted this article verbatim some weeks later, it provided a proper citation of the Ashtabula Sentinel as its source. But this fact is not included in citations in the scholarship. Instead, what is likely a four-times-removed report of the Tribune's review is attributed to Garrison himself.

By the time The Liberator printed this account of Barnum's production, however, the Tribune had already amended its judgment. In early December, after the paper had accepted Barnum's invitation to take a second look at the show, it published a more favorable review, reporting that “a successful effort has been made to make the play conform to the spirit of the original story.”Footnote 35 Most of the offensive parts of the play had been excised or toned down, the paper claimed: St. Clare's comments that U.S. slave labor was no worse than free labor in England had been cut, and the auction scene was now “rendered in a much more suitable and impressive manner.”Footnote 36 Did Barnum really transform Conway's play so significantly from the Boston Museum's version and then return it to its original politics? Whether the message of Conway's play seemed to change because of Barnum's amendments or because the critic approached it with fresh eyes on a different night, the progression of the Tribune's responses to Barnum's production illustrates just how slippery the play's political stance could be. Indeed, recent insights of performance studies suggest the difficulty of assigning a firm political position to something so dynamic as a theatrical performance.

Antislavery Justice in Conway's Uncle Tom's Cabin

For many years, because of the lack of an extant script, proslavery interpretations of the Conway play relied solely on newspaper coverage and a plot synopsis from the playbill. The discovery of a partial script in the 1990s has tended to temper the assessment instead of changing it.Footnote 37 But once we recognize that the newspaper accounts and advertisements do not support reading Conway's play as proslavery or conciliatory to Southerners, we can return to the text of the play from a new perspective that is more open to its political progressiveness.

Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin advances an antislavery argument that is both sentimental and legalistic. Amid the novel's many heartrending depictions of the way slavery tears families apart, Stowe offers frequent reflections on how the nation's laws are complicit in this cruelty. Aiken's adaptation embraces the novel's sentimentality and its otherworldly Christianity, culminating in little Eva's ascent to heaven “on the back of a milk-white dove, with expanded wings, as if just soaring upward,”Footnote 38 but he largely overlooks the legalistic arguments of Stowe's novel. Conway's play has its moments of sentiment, but in contrast with Aiken, it privileges intellectual discussion over emotional appeals, advancing an antislavery argument that explicitly calls upon the nation to match its laws and practices to its principles of liberty and justice as well as to Christian values. Its religious rhetoric is also focused more on life on earth than on heaven's rewards, and there is far greater attention to the punishments of both hell and the supernatural world for those who violate moral law. The difference between these plays is crystallized in their approaches to little Eva: while her death is the sentimental centerpiece of Aiken's adaptation and her ascent to heaven its spectacular finale, she doesn't die in the Conway script.

The happy ending that Conway wrote for Uncle Tom remained a serious drawback for the Tribune even after it amended its harsh assessment of P. T. Barnum's New York production. The newspaper stated that if Barnum would change the ending to more accurately reflect Stowe's novel, the production would receive its complete approval: “Now let him kill Uncle Tom and all will be right.”Footnote 39 This sense of the necessity of Tom's death might seem surprising to those who argue that one of the novel's chief offenses is its inability to imagine a racially integrated nation, as evidenced by Stowe's choice to have Uncle Tom die at the end of the novel and all the other major black and mulatto characters emigrate.Footnote 40 The conclusion of Aiken's script, with Legree's death and Tom's reward in heaven, falls short even more because it skips over the young George Shelby's crucial vow to “do what one man can to drive out this curse of slavery from my land!” and his final decision to free his slaves.Footnote 41 Aiken's play concludes with sympathy for Uncle Tom—a sympathy whose value should not be underestimated in an era when black humanity was still widely questioned—but without any compulsion to action.

For Stowe, Tom's death is both a personal victory and a spur to action; her investment in the rewards of heaven promised by Christianity does not stop her from advocating major civil reform. In her concluding remarks to the novel, she writes that Christ's will shall be “done on earth as it is in heaven”Footnote 42 and warns that the day of vengeance will come to a nation that harbors slavery. The complicity of Christian clergy in this injustice is, she writes, what motivated her to write Uncle Tom's Cabin. In explicitly calling for a change in the nation's laws, Stowe's novel is more progressive than Aiken's adaptation. But it does not picture a permanent, racially integrated nation in which emancipated slaves can develop meaningful lives away from their former masters. Instead, Stowe describes a temporary period of education for freedmen before they are sent to Africa as Christian missionaries.

Conway, however, imagines a future for freed slaves in the United States. Early in the Conway script, the young George Shelby envisions Tom's freedom; instead of vowing to buy Tom back (as he vows in Stowe's novel and attempts to do at the conclusion of Aiken's play), the boy vehemently commits to the slave's freedom:

I am only a boy, but listen to me and remember if I live to be a man you shall be free. See Uncle Tom, I have bored a hole through this dollar and I now put it around your neck. Kneel Uncle Tom and listen to the promise of a boy who will redeem it if he lives to be a man.

(Kneels placing ribbon with the dollar round Tom's neck.)

Uncle Tom! As there is a heaven above us and one who hears and sees all, I promise if I live you shall be free. So Heaven help me in my last hour. (1.3)

This urgent promise, which the kneeling boy reiterates three times as his last dying wish, launches the play's movement toward Tom's emancipation long before the scenes of Legree's cruelty. Young George does not explain why Uncle Tom must be freed, but his pledge finds validation in the words of Tom himself, who later celebrates the news that his wife is working to buy his freedom as the culmination of his prayers,Footnote 43 and in the clear-headed reasoning of a character Conway introduced to Uncle Tom's Cabin, the Connecticut traveler Penetrate Partyside.

At first glance, Conway's Penetrate Partyside seems to be roughly the equivalent of the Aiken adaptation's Gumption Cute: a typical stage Yankee who makes the audience laugh and extends the narrative arc of the Ophelia character. In Aiken's play, in which Ophelia ultimately brings Topsy back to Vermont and is courted by the widowed Deacon Perry, Gumption Cute is a con artist who uses his distant relationship to Ophelia (his second cousin married her niece) as an opportunity to live off her. Cute's appearance is a comic echo of the threats to George and Eliza's family; he first ineptly attempts to lure Topsy away to participate in a dehumanizing speculation (making money by exhibiting her as a “woolly gal” just as Barnum had exhibited a “woolly horse”)Footnote 44 and then attempts to eject Deacon Perry from Ophelia's house. Ultimately, however, Ophelia, Deacon Perry, and Topsy form a happy family unit, offering a satisfying resolution that contrasts with the two deaths (of Uncle Tom and of Simon Legree, who is killed by the lawyer, Marks) that end Aiken's play.

But Conway's Penetrate Partyside, a New Englander who is traveling in the South with his eyes and his notebook wide open, goes far beyond the comic diversion of Aiken's Gumption Cute. The aptly named character introduces a mood of penetrating, nonpartisan engagement with the issue of slavery. A proslavery reading of Conway's play works only if one views Penetrate as an insignificant figure. But Penetrate is fundamental to both the plot and the antislavery argument of Conway's play. His innocent questions and logical conclusions, which are evident from the moment he appears onstage in act 2, suggest the ethical problems of slavery without attacking Southerners. His constant comparisons of things “ginerally” and things “particlarly” reveal his preoccupation with matching principles and actions; in his view, laws that legalize slavery force the United States to violate both Christian values and the nation's basic principle of freedom. As he boards the boat on which St. Clare, Eva, Aunty Vermont (Conway's name for the Ophelia character), and Uncle Tom are traveling, Penetrate notices the people chained below the gangway and asks a waiter about them. They must, he says, be guilty of murder or theft; such an arrangement must be the result of breaking a law. But the waiter informs him that they are not criminals, only slaves on the way to market. This strikes the ever-logical Penetrate as unjust. He instructs himself:

Penetrate, put that down in your remarks on the wisdom, mercy, and justice of the laws of the United States, the home of the free and the land of the brave! Mem.

(writes)

Niggers chained like dogs ginerally; because they are going to be sold according to law particlarly. Queer! Who deserves to be chained most, the niggers to be sold, or the owners who sell them? (2.2)

Always alert to the gap between “ginerally” and “particlarly,” Penetrate questions how “the home of the free” can countenance such treatment of people who have done nothing wrong. Despite the fundamental American right to liberty, this egregious injustice happens, as he writes in his notebook, “according to law.” A similar breakdown between values and actions is at the heart of Penetrate's initial conversation with St. Clare. How, he asks, would St. Clare feel if he was divvied up and sold, his value calculated part by part? If St. Clare would not himself want to be sold, why, then, does he buy and sell human beings? The very idea of slavery is wrong, Penetrate insists with the simple ethics of the Golden Rule. In Stowe's novel, these are St. Clare's reflections, couched in the futility of his “think right, do nothing” philosophy (“up to heaven's gate in theory, down in earth's dust in practice”).Footnote 45 Conway's decision to assign these arguments to Penetrate, who is trying to sway St. Clare, gives them more urgent persuasive power.

And yet, crucially, Penetrate's critique of slavery is not a sectional critique of the South. Visiting St. Clare's plantation in Louisiana, for example, he finds that slavery is not always so awful in its actual application as it is in theory. Southerners are, Penetrate tells St. Clare, “warm-hearted and generous,” but he intimates that their loyalties are too narrow: they would fight for their “own liberty particularly” but not, as he notes St. Clare might, for “human nature generally” (3.2). Southerners, he argues, should expand their understanding of the right to liberty to embrace all human beings, not just whites. Further resisting sectionalism, Penetrate acknowledges that Northerners are not exactly beacons of virtue either. In northern factories, some “sewing machines” are not mechanical apparatus but “flesh and blood—and female flesh and blood tu [sic] at that” (2.2). Moreover, in the process of searching law books for a way to free Tom from Legree's evil grip, Penetrate discovers a law that requires masters to care for their freed slaves, and he comments that it would be wonderful if Northerners would pass a law mandating care for their former servants. Ultimately, his critique of injustice and inequality in U.S. society extends across region, race, and class.

That Penetrate searches law books to help free Tom rather than turning to moral suasion or violence is telling. For Penetrate, and for Conway's play as a whole, the solution to an injustice as huge as slavery lies in creating and obeying ethical laws. Where Aiken's Uncle Tom's Cabin envisions heaven as the site of ultimate justice, the Conway script is invested in legal solutions to social wrongs. Indeed, even after Legree is vanquished and the major threat to Uncle Tom is gone, law is at the heart of the play's conclusion. Conway's controversial happy ending is ornamented by the discovery of a series of illegalities: not only was Legree's ownership of Eliza and Cassy the result of criminal acts (kidnapping and “a false bill of sale” [5.1] respectively), the sale of Tom to Legree was also unlawful. In addition to offering further evidence of Legree's criminality, this extra layer of illegality might be read as underscoring how the legal sale of human beings can breed disregard for the very concept of individual liberty.

Conway's play is most progressive in its final scene. Proslavery dramas of the 1850s allowed their black characters to live but never to be free; after depicting a fugitive slave's miseries under freedom in the North, the plays would conclude with the fugitive's joyful return to the former master. Conway could have ended his play by sending Tom back to the Shelby plantation, even as a free man. In addition, once Tom and his family were freed, Penetrate could simply have kept the money that he and Aunty Vermont had scrimped and saved to purchase Tom's freedom. Instead, Penetrate enthusiastically invests in Tom's future in the United States, offering Tom funds to purchase “a lot of good land down East,” where he can build a cabin for himself and his family (5.3). Ultimately, Conway's play understands that both emancipation and investing in the futures of freedpeople are necessary.

Penetrate concludes the play by telling the audience to stand in support of “Uncle Tom getting his freedom as we here are particularly” and asking them to offer their best wishes and hopes to Tom, “that his life may be happy though it be life among the lowly—Uncle Tom's Cabin” (ibid.). This call to rise demands the audience's investment in a happy life for Tom and his family in the United States. It is true that Penetrate's unquestioning acceptance of the notion that Tom must live “among the lowly” even once he is free is deeply problematic from a contemporary perspective. Moreover, the play's vision of a nation that includes freed slaves comes at the cost of some of the black characters: while Conway's Uncle Tom is a dignified, well-spoken Christian, many of his minor characters are purely comic and lack the nuance of Stowe's characterizations. But those who object to Uncle Tom's death in Stowe's novel may well appreciate that Conway's script imagines that there is indeed a place for free blacks in the nation. In an era when even many abolitionists embraced colonization, Conway's play advanced a potentially progressive alternative to Stowe's antislavery vision.

Ultimately Aiken's Uncle Tom's Cabin was more commonly performed than the Conway play, at least in part because his script was published in 1858 whereas Conway's play was not, and because the longtime producer and actor George C. Howard and his wife promoted it throughout their careers. But in 1876, in honor of the American Centennial, Howard combined the Aiken and Conway scripts into “a new version adapted to the sentiment of the times,” for the first and only time.Footnote 46 In order to appeal to the atmosphere of sectional reconciliation that characterized the nation's centennial, the combined script was edited to omit discussion of section wherever possible, cutting critiques of both Northerners and Southerners.Footnote 47 Reconciliation also required avoiding attacks on slavery: even after the war, many white Southerners continued to insist it had been a benign institution that had protected slaves and burdened slaveowners more than anyone else. Consequently, the edits to the Aiken–Conway combination minimized explicit discussion of the “peculiar institution.” More specifically, the amended script eliminated all of Penetrate's dialogue discussed here. These changes thus underscore not only the powerful critique of slavery in the Conway script but also the progressive political implications of an antislavery play even after emancipation and reconstruction, as American laws and practices increasingly diminished the civil and political rights of African Americans, making way for the reign of Jim Crow.

• • •

The full history of Uncle Tom's Cabin on the U.S. stage, of its performance thousands of times by hundreds of theatrical companies using a wide variety of scripts (or indeed no script at all), remains to be written. The H. J. Conway version of Uncle Tom's Cabin is just one of many Uncle Tom dramas that deserves a more comprehensive look. But it is clear that any such enterprise will be enriched by a methodology that makes extensive use of the archive, especially of newspaper coverage of the shows. In more fully documenting how audiences responded to the plays, such a methodology can both open interpretive space for reading extant scripts within the context of their performance and help us recognize the lasting progressive power of this much-maligned play, and indeed of the nineteenth-century popular stage.