Introduction

Case example

Devon is a 37-year-old African American male, working as a mechanic in the Midwest. Despite living an honest life and abiding by the law, Devon feels others treat him as if he is dangerous and threatening. When shopping he observes that mall security tends to follow him around. He also notices strangers often cross the street or clutch their belongings when he passes. The few times he has commented or questioned if the motivation of people’s behaviours were racial, they seemed surprised and affronted. Recently Devon has also noticed that he has been pulled over by police officers for ‘routine’ stops, much more than his non-Black friends, and police treat him disrespectfully (Voigt et al., Reference Voigt, Camp, Prabhakaran, Hamilton, Hetey, Griffiths, Jurgens, Jurafsky and Eberhardt2017). He finds his frustration at these injustices mounting and worries he will lose his temper. He is close to his parents, although they live far away, but when he shares his experiences, he’s told to ‘Let it go’. His father says, ‘I grew up during Segregation, and that was real racism’. A friend suggests he talk to a professional about his concerns. Devon does not particularly enjoy sharing his feelings but after much consideration eventually engages a counsellor. The counsellor is an Asian American male, and within the therapy session it becomes increasingly obvious the counsellor is uncomfortable talking about race and racism (Hemmings & Evans, Reference Hemmings and Evans2018) The few times the counsellor does entertain discussions around race, it seems he feels Devon is exaggerating or misinterpreting others’ perceptions of him. Feeling unvalidated and unsupported, Devon does not return to therapy after three sessions (Williams and Halstead, Reference Williams and Halstead2019). His mental health and sense of wellbeing continues to decline.

About microaggressions

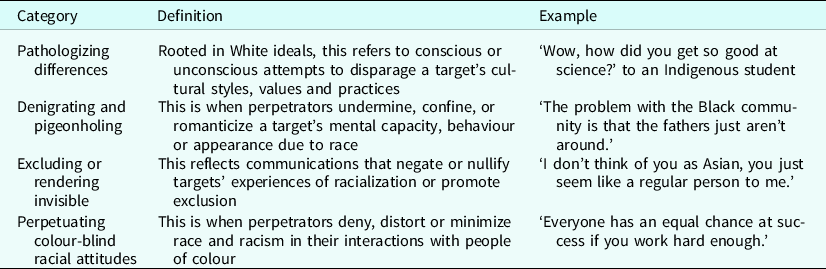

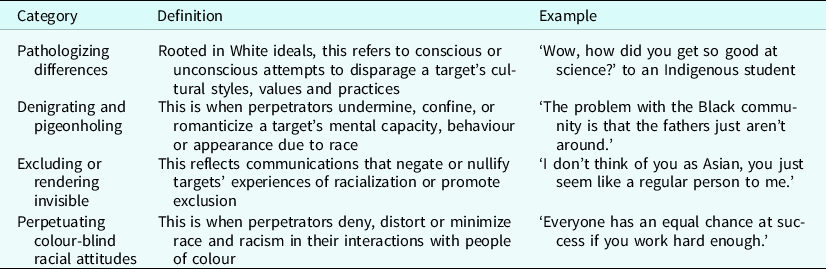

In recent decades, there has been increased research on how subtle forms of racism may be enacted in everyday situations. Microaggressions were first described by African American psychiatrist and educator Chester Pierce (Reference Pierce and Barbour1970) to conceptualize the unacknowledged racism he experienced from White Americans. Racial microaggressions are covert racial slights, generally thought to be unintended, and they are frustratingly deniable by offenders (Sue et al., Reference Sue, Capodilupo, Torino, Bucceri, Holder and Nadal2007; Williams, Reference Williams2020a). Research has demonstrated that racialized groups in the US experience microaggressions regularly, including African Americans, Asian Americans, and Hispanic Americans (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Skinta and Martin-Willett2021). Microaggressions have been identified globally as well, including in Canada, the UK, Australia, Germany, Malaysia and Israel (e.g. Choi et al., Reference Choi, Poertner and Sambanis2020; Gatwiri, Reference Gatwiri2021; Houshmand et al., Reference Houshmand, Spanierman and De Stefano2019; Nasir et al., Reference Nasir, Nor, Yaacob and Rashid2021; Rollock, Reference Rollock2012; Shoshana, Reference Shoshana2016). Based on an extensive review of the literature, Spanierman and colleagues (Reference Spanierman, Clark. and Kim2021) place microaggressions into four major categories, described in Table 1 (with examples).

Table 1. Four major categories of racial microaggressions

Although there are many types of microaggressions based on stigmatized facets of a person’s identity (gender, religion, disability, sexual orientation, etc.), racial microaggressions specifically contribute to a chronically stressful and oppressive environment for many people of colour. Psychological correlates include symptoms of depression, severe distress, decreased quality of life, anxiety, trauma symptoms, substance use disorders, and even suicidal ideation (Lui and Quezada, Reference Lui and Quezada2019; Spanierman et al., Reference Spanierman, Clark. and Kim2021; Williams, Reference Williams2020b; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Skinta and Martin-Willett2021). Thus, from a mental health perspective, microaggressions are a significant concern. Microaggressions also become a barrier to effective mental health care when committed by therapists, as illustrated in the case of Devon, and have been implicated as a significant contributor to mental health disparities (Dovidio and Casados, Reference Dovidio and Casados2019; Sue et al., Reference Sue, Capodilupo, Torino, Bucceri, Holder and Nadal2007; Williams and Halstead, Reference Williams and Halstead2019). Likewise, microaggressions can create a hostile environment in the workplace, leading to stress, lost productivity and employee turnover (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Nguyen and Block2018; Pitcan et al., Reference Pitcan, Park-Taylor and Hayslett2018).

Most microaggressions research has been focused on racial microaggressions committed by White people towards people of colour, but little work has been done to understand the characteristics and motivations of people of colour who commit racial microaggressions against other people of colour. Such findings could provide a better understanding of the psychology of those delivering these microaggressions and inform cognitive behavioural interventions aimed at reducing the frequency and impact of these acts.

Racial microaggressions are racist and aggressive

In a landmark study, Kanter and colleagues (Reference Kanter, Williams, Kuczynski, Manbeck, Debreaux and Rosen2017) reported on the links between likelihood of committing microaggressions and racial prejudices. In this study, a cross-sectional survey was administered to 151 Black and White undergraduate students from large US universities in the South and Midwest. The Black students (n = 33) were given a series of statements to determine if they were microaggressive, whereas the White students were given the same statements, but asked the likelihood of delivering these statements. The White students also completed measures of racial prejudice. It was found that White students who indicated they were more likely to commit microaggressions also held racist beliefs and negative feelings and opinions towards Black people. Therefore, this study exhibited how the propensity to commit microaggressions can reveal underlying negative racial attitudes. This study was ground-breaking in the sense that it validated the feelings of those experiencing microaggressive statements and actions and suggested that these behaviours were actually a form of racism, not just simply a subjective perception of the victim.

Another study by the same research team evaluated microaggressions from the White aggressors’ point of view to understand the characteristics of those committing microaggressions (Kanter et al., Reference Kanter, Williams, Kuczynski, Corey, Parigoris, Carey, Manbeck, Wallace and Rosen2020). They refined the measure of microaggression likelihood piloted in the aforementioned study and developed a new version called the Cultural Cognitions and Actions Scale (CCAS) that consisted of four factors: Negative Attitudes, Colorblindness, Objectifying, and Avoidance. The same measures of racism were used in combination with the CCAS for 978 non-Hispanic White American undergraduate students to derive associations between racism and the likelihood to commit microaggressions. The study team uncovered results consistent with previous findings (Kanter et al., Reference Kanter, Williams, Kuczynski, Manbeck, Debreaux and Rosen2017), in that microaggressive tendencies in non-Hispanic White Americans were associated with racist beliefs and attitudes.

Aggression is a behaviour inherent in the perpetuation of racism, and which manifests in various forms, whether direct, indirect, physical or verbal (Allen and Anderson, Reference Allen and Anderson2017; Archer, Reference Archer2004). While direct forms of aggression, like physical or verbal attacks, are commonly recognizable, indirect aggression is a more covert attack on the social or relational aspects of a person’s life through means of gossip, ostracization, rumours, patronizing behaviours, or defamation, to name a few (Archer, Reference Archer2004). In a cross-sectional study, a sample of diverse adults across the US were surveyed to determine the relationship between propensity to commit microaggressions and traditional measures of aggression (Williams, Reference Williams2021). To ascertain propensity to commit microaggressions, the CCAS (Kanter et al., Reference Kanter, Williams, Kuczynski, Corey, Parigoris, Carey, Manbeck, Wallace and Rosen2020) was administered. Three measures of aggression were also administered. The CCAS was found to be highly and significantly positively correlated with all measures of aggression for White participants. There was a significant positive correlation between negative affectivity and the tendency for participants to commit microaggressions, but in a regression predicting microaggressive propensity from aggressive tendencies, aggression remained a significant predictor, whereas negative affectivity did not. The study suggested that microaggressions represent aggression and hostility on the part of offenders.

Are microaggressions aggressive when delivered by people of colour?

Although it seems clear that microaggressions are a form of racial aggression when directed at Black people by White people, it is unclear how they are perceived when directed from one person of colour to another. Microaggressions are context-dependent, and a behaviour by a minoritized group member may be perceived differently than the same behaviour from a dominant member. For example, when asked by someone of the same ethnic group, the question, ‘Where are you from?’ may be perceived as an attempt at social connection but when coming from someone of a different ethnic group it may be a negative reminder of differences (e.g. Kanter et al., Reference Kanter, Williams, Kuczynski, Manbeck, Debreaux and Rosen2017). As such, it has not been determined if within-group racial microaggressions are even aggressive at all. Although a matter of debate, some scholars assert that only White people can commit racial microaggressions (Spanierman et al., Reference Spanierman, Clark. and Kim2021).

Racism, however, may occur within and between minoritized groups, as individuals ascribe to the narrative that it is possible to elevate their own status by oppressing others within the dominant framework. Thus, microaggressions can be perpetrated by people of colour against other people of colour from different or the same ethnic groups. Ultimately, this type of racism only advantages the dominant group, e.g. non-Hispanic Whites. Such attitudes and behaviours on the part of racialized people is termed internalized racism – the psychological consequence of accepting the negative, oppressing beliefs, ideologies and stereotypes of a White dominant society (Haeny et al., Reference Haeny, Holmes and Williams2021; Pyke, Reference Pyke2010). Internalized racism can result in self-degradation, shame, and a lack of self-respect (Bryant, Reference Bryant2011), and has been found to inversely correlate with self-esteem and positive ethnic identity (Hipolito-Delgado, Reference Hipolito-Delgado2016; James, Reference James2017). Internalized racism contributes to negative attitudes not only towards the self but also towards members within a person’s own racial group and community, which can manifest in various ways such as colourism, and disparaging and distancing from one’s community (Pyke, Reference Pyke2010). Bryant (Reference Bryant2011) found a correlation between internalized racism and propensity for violence among African American male youth. Accordingly, a more negative self-identity due to internalized racism may contribute to developmental deviations including self-destructive behaviour, increases in aggressive behaviour, and a propensity for aggression. It could be that people of colour who commit racial microaggressions are acting out on racially biased and aggressive tendencies, leading to harm in other people of colour.

For example, Suárez-Orozco and colleagues (Reference Suárez-Orozco, Casanova, Martin, Katsiaficas, Cuellar, Smith and Dias2015) conducted an observational study of microaggressions in classrooms at three different colleges, documenting 51 instances of microaggressions across 60 classrooms observed. Notably, they found that instructors committed most of the microaggressions (n = 45), emanating from a diverse range of instructors across gender, age, race and ethnicity. This may stem from a desire to establish dominance over the students and create boundaries in the classroom, but nevertheless can be harmful to minoritized students by contributing to stereotypes and fostering negative feelings toward themselves and others.

In a preliminary study of 122 undergraduates, Mujica and Bridges (Reference Mujica and Bridges2020) found that Latinx and Black students were more likely to rate microaggressive statements as more discriminatory than White students given the same scenarios, but there was no difference in ratings of discriminatory statements based on type of perpetrator (ingroup versus outgroup). Participants of colour found the microaggression to be equally offensive whether or not it was delivered by a White person or someone from the same group as the victim. This indicates that microaggressions may be perceived negatively, even when the exchange occurs between people of the same racialized group.

Microaggressions between different ethnoracial groups have also been shown to be harmful. In a recent mixed-methods study assessing inter-ethnic experiences of racial microaggressions among science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) students of colour (n = 1688) attending a large public university in the Midwest, ‘Black and Latinx students wrote extensively about how White and Asian students did not want to work with them in the lab, during discussion sections, or during group projects because of negative stereotypes about their intelligence and work ethic’ (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Collins, Harwood, Mendenhall and Huntt2020; p. 12). The authors described these behaviours from the White and Asian students as ‘microinsults’ (Sue et al., Reference Sue, Capodilupo, Torino, Bucceri, Holder and Nadal2007) based on unsupported racialized assumptions about intelligence, which contributed to perceived marginalization and reduced feelings of belongingness, and ultimately increased attrition from the STEM major.

Anti-Black microaggressions have been found in interactions with Hispanic/Latinx peers in higher education as well. Willis and colleagues (Reference Willis, Mattheis, Dotson, Brannon, Hunter, Moore, Ahmed and Williams-Vallarta2019) used a narrative inquiry approach to examine experiences of microaggressions among Black female students at a predominantly Hispanic-serving institution. They uncovered themes of exclusion (e.g. not knowing how to speak Spanish and feeling excluded from certain conversations), sexualization of Black males (e.g. overhearing non-Black female peers’ conversations in which they objectify facial features, skin tone, and other stereotypical physical attributes of Black males), as well as ‘feeling boxed in and silenced’ (e.g. receiving stereotyped messages about how Black females should dress, behave, or aspire to career-wise).

Purpose of this study

The purpose of this study was to better understand the relationships among anti-Black racial microaggressions, aggression, negative affect, and ethnic identity among different groups of colour. Specifically, we sought to determine if anti-Black racial microaggressions were associated with aggression, as evidenced by greater aggressive tendencies in perpetrators, in various ethnoracial groups, after controlling for negative affect. We also sought to understand what demographic factors are correlated with propensity to commit microaggressions and determine if a stronger ethnic identity (which tends to be negatively correlated with internalized racism) impacts this relationship. These findings can help inform therapeutic and educational interventions to address within- and between-group racial microaggressions.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited for this study online through Amazon Mechanical Turk (mTurk) Prime (now CloudResearch). Eligibility criteria included: being over 18 years of age; identifying as African American/Black, Asian American, or Latino/Hispanic American; having spent most of childhood in the US; and being able to read and speak English.

Only eligible mTurk workers were able to view the posted recruitment invitation. If they accepted the invitation, they were able to access the consent form and complete an online battery of survey questions. The mTurk population is demographically similar to the general US population in geographic location and gender distribution (Huff and Tingley, Reference Huff and Tingley2015). This study was approved by the University of Connecticut’s Institutional Review Board. Average compensation amount was US$6.00 an hour, and the survey took approximately one hour to complete.

A total of 844 participants were enrolled, but only the 356 participants of colour were included in this study (results from the White sample have been reported previously; Williams, Reference Williams2021). Demographics by group are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Demographics by ethnic/racial group

Measures

A comprehensive demographics form was administered to collect information about participant race based on US Census categories, Hispanic versus non-Hispanic ethnicity, age, gender, sexual orientation, nativity, length of time living in the US, marital status, income, and years of education. The remaining measures are listed below. All measures were delivered online via Qualtrics, with individual items randomized by section, as appropriate.

Cultural Cognitions and Actions Scale (Kanter et al., Reference Kanter, Williams, Kuczynski, Manbeck, Debreaux and Rosen2017; Kanter et al., Reference Kanter, Williams, Kuczynski, Corey, Parigoris, Carey, Manbeck, Wallace and Rosen2020)

The CCAS is a measure that determines the likelihood that a person will engage in racial microaggressions, with a focus on interactions between Black and White people. The CCAS has 20 items, with four subscales of five items each: Negative Attitudes (hostility, microassaults), Colorblindness (deflection of differences, microinvalidations), Objectifying (exoticizing statements), and Avoidance (exclusion and distancing). The questions assess microaggressions across seven different social contexts, whereby participants answer questions about how they might respond in each of the situations. The scenarios included: (1) interacting with a young woman with African-style dress and hair; (2) having a discussion at a required diversity training; (3) talking about racially charged current events with friends; (4) giving directions to a Black man in the respondent’s own neighbourhood; (5) singing along to rap music with diverse friends; (6) talking about police brutality in the news at a sports bar; and (7) working together on a difficult project with a racially ambiguous partner. After each scenario, a series of actions or statements one might make in that situation were provided and participants were asked to report how likely they would be to say or do each response (where 1 is ‘very unlikely’ and 5 is ‘very likely’). All 20 items can be summed for a total score, or each subscale can be examined separately. The CCAS has shown good concurrent validity in that people with higher scores have more racist attitudes and scores reduce after participating in a diversity workshop (Kanter et al., Reference Kanter, Williams, Kuczynski, Manbeck, Debreaux and Rosen2017; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Kanter, Peña, Ching and Oshin2020).

Predictive validity of the CCAS has been established with laboratory experiments, whereby White participants who had taken the CCAS engaged in real-time interactions about race-related current events with a White confederate while a Black research assistant observed the conversation via a live video-feed (Kanter et al., Reference Kanter, Williams, Kuczynski, Corey, Parigoris, Carey, Manbeck, Wallace and Rosen2020). An independent team of coders reviewed the video recordings of the conversations and rated the amount of microaggressive behaviours displayed by participants in the conversations. There was a high correlation between CCAS scores and commission of microaggressions for two of the three scenarios presented. We utilized the same 20-item version of the CCAS described in Williams (Reference Williams2021). The CCAS has demonstrated good internal consistency in White samples, and reliability ranged from good to excellent in the different subgroups in our sample as well (Black: α = .89; Asian: α = .87; non-White Hispanic: α = .97; White Hispanic: α = .91). See the Supplementary material online for a list of all items and means by group and subscale.

Several diversity experts (n = 8) were given a slightly different version of the CCAS (the CCAS-R), with modified prompts to determine to extent to which they deemed there was racism within each vignette (Kanter et al., Reference Kanter, Williams, Kuczynski, Corey, Parigoris, Carey, Manbeck, Wallace and Rosen2020). Items were rated from 1 (‘very racist’) to 5 (‘very positive (non-racist, understanding, sensitive’). The majority of experts agreed the items were racist, and likewise, large proportions of Black Americans in a national sample agreed that the microaggressions depicted were racist as well (n = 226; Williams, Reference Williams2021).

Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ; Buss and Perry, Reference Buss and Perry1992)

The BPAQ is a 29-item survey measuring hostile behaviour and aggression. The questionnaire contains four domains: physical aggression, verbal aggression, anger, and hostility. The BPAQ is considered a gold standard for quantifying the construct of aggression and has been validated in several languages and cultures, with men typically scoring higher than women (Archer, Reference Archer2004; Gerevich et al., Reference Gerevich, Bácskai and Czobor2007). After reverse-scoring two items, items are summed for a total score. Reliability was excellent in the different subgroups in our sample (Black: α = .93; Asian: α = .92; non-White Hispanic: α = .96; White Hispanic: α = .94).

Overt-Covert Aggression Inventory (OCAI; Miyazaki et al., Reference Miyazaki, Shimizu, Komaki, Tsuboi, Kobayashi, Fujita and Kawamura2003)

The OCAI is a 10-item scale measuring both overt and covert hostility. The OCAI was originally developed in Japan to account for the fact that anger may manifest differently in people from other cultural groups. Items are scored on a scale of 1 to 5 (‘never’ to ‘always’). Reliability ranged from good to excellent in the different subgroups in our sample (Black: α = .87; Asian: α = .85; non-White Hispanic: α = .92; White Hispanic: α = .89).

Inventory of Hostility and Suspicious Thinking (IHS; Tellawi et al., Reference Tellawi, Williams and Chasson2016)

This is a 19-item scale that measures symptoms of interpersonal hostility and suspicion. This includes worries of being talked about, bitterness, suspicion of others, and unusual thinking. A few of the items overlap with the BPAQ. The questionnaire is correlated with mental health problems, such as anxiety-related conditions and psychosis (Huppert et al., Reference Huppert, Smith and Apfeldorf2002). Reliability was good in the different subgroups in our sample (Black: α = .95; Asian: α = .95; non-White Hispanic: α = .98; White Hispanic: α = .96).

Positive and Negative Affectivity Schedule – Negative Affectivity Scale (PANAS-Neg; Watson et al., Reference Watson, Clark and Tellegen1988)

The PANAS-Neg is designed to measure negative affect across different periods of time. Items are rated from 1 to 5, with higher numbers indicative of greater agreement. Participants are asked to rate items based on how they feel ‘in general’, ‘now’, or over a specified period of time to quantify affect. For this study, most participants were instructed to rate their feelings over the past 2 weeks, and reliability was good in the different subgroups in our sample (Black: α = .91; Asian: α = .88; non-White Hispanic: α = .93; White Hispanic: α = .93). A subset of participants was asked about their affect ‘in general’ rather than the last 2 weeks, for a score that reflected a more trait-like form of affectivity, and reliability was good in the different subgroups in our sample (Asian: α = .89; non-White Hispanic: α = .92; White Hispanic: α = .92).

Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM-6; Williams, Duque & Wetterneck, Reference Williams, Duque and Wetterneck2015)

The MEIM is designed to assess the strength of the participant’s ethnic identity, or positive sense of connection to their ethnoracial group (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Phinney, Masse, Chen, Roberts and Romero1999). We used a modified 6-item version, and reliability ranged from fair to good in the different subgroups in our sample (Black: α = .86; Asian: α = .86; non-White Hispanic: α = .77; White Hispanic: α = .85).

Data analysis

Comparison of CCAS and CCAS-R scores

To determine general acceptability of racial microaggressions, we computed the mean for each item of the CCAS for each ethnoracial group. As per the methodology described in Michaels et al. (Reference Michaels, Gallagher, Crawford, Kanter and Williams2018) and Williams (Reference Williams2021), we conducted Pearson’s correlations between the previously published diversity expert CCAS-R scores and the CCAS score from our sample for each ethnoracial group for the 20 items to ascertain the degree of agreement (Kanter et al., Reference Kanter, Williams, Kuczynski, Corey, Parigoris, Carey, Manbeck, Wallace and Rosen2020).

Analyses of aggression and affect

To determine if (micro)aggressive tendencies were different among ethnoracial groups (i.e. Black, Asian, Hispanic non-White, Hispanic White), we first conducted one-way ANOVAs of the CCAS and the three measures of aggression with ethnoracial group as the between-groups factor. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction were conducted to follow up on a significant omnibus effect.

Next, to determine if the tendency to commit microaggressions is related to aggression, for each group separately, we generated bivariate correlations among the CCAS and the same three measures of aggression, as well as negative affect and ethnic identity. For each group separately, we also examined correlations among the CCAS and all demographic variables which might influence findings (i.e. age, gender, sexual orientation, marital status, annual household income, education, binarized where appropriate). In these correlations, the Hispanic non-White and Hispanic White groups were also combined for additional findings. For Black, Asian and the combined Hispanic groups, significant correlations with CCAS among demographic variables, negative affect and ethnic identity were used to determine appropriate covariates for subsequent regressions.

Finally, to better understand the most prominent and unique predictors of committing microaggressions, we conducted separate hierarchical regressions for each ethnoracial group (Black, Asian, Hispanic), entering appropriate co-variates identified above in the first step, and BPAQ total scores in the second step, with the CCAS total score as the outcome. Of the three aggression measures, BPAQ was selected for these regressions because it is the most widely used measure of the construct of aggression in the literature and to avoid issues of multicollinearity among measures of aggression. For regressions of the Hispanic group, race was binarized (White versus non-White) and entered as a co-variate in the first step.

Results

Microaggressions and demographics

The relationship between the CCAS and several of the demographic variables was examined in the various ethnoracial groups (see Table 3). There was a correlation between the CCAS and age (as a continuous variable) in the Black sample only. There was a correlation between gender (as a binary variable) and the CCAS in the Hispanic sample, and a significant correlation between sexual orientation and the CCAS in the Asian sample. There were no relationships between income category (as an ordinal variable with eight levels) or education (as an ordinal variable with seven levels) for any of the groups.

Table 3. Correlations of demographics with CCAS by ethnic/racial group

The n values stated in the top row apply to all bivariate correlations in each group except that some comparisons (gender and sexual orientation) have slightly lower n values as a non-binary participant was excluded. Gender was binarized as ‘cisgender male’ (0) and ‘cisgender female’ (1); the two genderqueer participants (1 Black, 1 Asian) were not included in these correlations. Sexual orientation was binarized as ‘heterosexual’ (0) and ‘LGBQ’ (1); participants who mistakenly responded with their gender were treated as heterosexual, and responses that were uninterpretable or ‘prefer not to say’ were treated as missing. Marital status was binarized as ‘single, widowed, divorced/annulled or separated’ (0) and ‘married or living with partner’ (1). Annual household income was binarized as ‘$59,999 or less’ (0) and ‘$60,000 or more’ (1). Educational attainment was binarized as ‘graduated 2-year college or lower’ (0) and ‘graduated 3- or 4-year college or higher’ (1). *p<.05, **p<.01 (two-tailed).

Microaggression acceptability

Despite some variability, there was a significant correlation between expert ratings of microaggression interactions being racist as per the CCAS-R and participants’ unlikelihood of engaging in those same interactions on the CCAS. The correlations for Asian (r = .445) and White Hispanic (r = .446) were significant (p<.05), whereas for Black (r = .417; p = .067) and Non-White Hispanic (r = .443; p = .050) the correlation was only marginally significant. This means that, for the most part, the more racist the behaviour was deemed by diversity experts, the less participants endorsed a likelihood of doing the behaviour, indicating some shared understanding that the microaggressive behaviours are unacceptable.

Microaggressions and aggression

Next, the correlations between the CCAS and measures of aggression and affect were examined (see Table 4). All three measures of aggressions were positively correlated in all ethnoracial groups. The BPAQ and OCAI were robustly positively correlated with the CCAS for the Hispanic and Black groups, but less strongly correlated for the Asian group. The IHS was more strongly correlated in the Hispanic groups, but less so in the Black and Asian groups. Using the Fisher’s r-to-z test, the BPAQ-CCAS correlations were significantly different among all groups (z = 1.80 to 5.04, p = <.001 to .04), except between White Hispanic and Black participants (z = 1.20, p = .12), and Black and Asian participants (z = 1.44, p = .08). Negative affect was correlated to the CCAS only in the non-White Hispanic group, and ethnic identity was correlated only in the Asian group.

Table 4. Descriptives and correlations of primary study variables with CCAS by ethnic/racial group

The n values stated in the top row apply to all bivariate correlations in each group unless otherwise stated in accompaniment with the relevant correlations. Hispanic and Asian American participants responded to the PANAS-Neg based on either of two reference points (i.e. ‘over last 2 weeks’ or ‘in general’), whereas all Black participants responded to the PANAS-Neg ‘in general’. An omnibus F-test and post-hoc pairwise comparisons indicated that non-White Hispanic participants endorsed greater microaggression likelihood than Black or Asian participants for the CCAS, both p values<.05 (not reported in main text). *p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001 (two-tailed).

Predicting microaggressions

We conducted separate hierarchical regressions for each ethnoracial group, predicting the CCAS total score from the total BPAQ and other related variables, as per the findings of our bivariate correlations (see Table 5). As noted previously, we did not include the OCAI or IHS in any of these regressions because we wanted to include only one measure of aggression (as these measures are highly correlated; Williams, Reference Williams2021), and the BPAQ is considered the gold-standard. Among Black participants, the BPAQ was the strongest predictor of microaggressiveness, with greater age also significantly predicting more microaggressiveness. For the Asian sample, ethnic identity was the strongest predictor of microaggressiveness, with greater BPAQ also significantly predicting more microaggressiveness. We ran two models for the Hispanic group, one with the more trait-like version of the PANAS whereas the other version of the PANAS assessed negative affect over only the previous 2 weeks. White versus non-White status was included as a binary variable. The significance of negative affect dropped out once the BPAQ was added to the model, which was highly significant. Gender was significant in the model that included negative affect in general, with males being more microaggressive than females.

Table 5. Hierarchical regressions predicting CCAS from aggression and relevant co-variates by group

Sexual orientation was binarized as ‘heterosexual’ (0) and ‘LGBQ’ (1); participants who mistakenly responded with their gender were treated as heterosexual, and responses that were uninterpretable or ‘prefer not to say’ were treated as missing. Gender was binarized as ‘cisgender male’ (0) and ‘cisgender female’ (1); the two genderqueer participants (1 Black, 1 Asian) were not included in these correlations. Marital status was binarized as ‘single, widowed, divorced/annulled or separated’ (0) and ‘married or living with partner’ (1). Race for Hispanic participants was binarized as ‘non-White’ (0) and ‘White’ (1). Predictors entered in the first step for each regression have values in the corresponding rows under Model 1. *p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001 (two-tailed).

Discussion

Microaggressions are aggressive

Racial microaggressions appear to represent a form of relational aggression, even when perpetrated by other people of colour. The propensity to commit microaggressions was significantly correlated with three validated measures of aggression in all ethnoracial groups examined. Furthermore, the correlation between whether one would commit a microaggression (as per the CCAS) and racism ratings by diversity experts (CCAS-R) was roughly equivalent across groups, indicating some shared degree of understanding that the depicted behaviours are unacceptable. This is consistent with findings that White adults are unlikely to commit most microaggressions, especially those deemed most racist by Black respondents (Williams, Reference Williams2021). It is also consistent with earlier work which found that across racial groupings, microaggressions were deemed largely unacceptable among college students (Mekawi and Todd, Reference Mekawi and Todd2018; Michaels et al., Reference Michaels, Gallagher, Crawford, Kanter and Williams2018). Therefore, contrary to assertions of some theorists, it should not be assumed that microaggressions are always unintentional or that perpetrators generally mean well (e.g. Haidt, Reference Haidt2017). It should also not be assumed that people of colour do not commit racial microaggressions. Consistent with the observations of Suárez-Orozco and colleagues (Reference Suárez-Orozco, Casanova, Martin, Katsiaficas, Cuellar, Smith and Dias2015), our study indicates that people of colour do commit microaggressions towards other racialized people, including those in their own group. This behaviour is not better explained by negative affect beyond the role of aggressive tendencies.

Why would people of colour levy interpersonal racial aggression against other likewise racialized individuals? One explanation mentioned previously is internalized racism. Pyke (Reference Pyke2010) describes one form of this as distancing oneself from those within one’s own racial group that have a closer proximity to negative stereotypes. For example, certain Asian Americans may use the racially microaggressive term ‘FOB’ (meaning ‘Fresh Off the Boat’) to describe less acculturated members of the Asian community. In this way, Asian Americans may ostracize new immigrant members of their own racial group because of internalized racism. That being said, among Black participants, we found little to no relationship between propensity to commit microaggressions and ethnic identity, where a strong ethnic identity should be negatively correlated to internalized racism. Among our Asian American participants, there was a significant positive correlation between ethnic identity and microaggressiveness, contrary to expectations. It has been suggested that stronger feelings of closeness to one’s own group may in some cases be associated with heightened devaluation and microaggressions toward members of other groups, including Black individuals (Brewer, Reference Brewer1999). Nonetheless, findings suggest that among people of colour, the commission of microaggressions may be more universally related to aggressive tendencies as opposed to internalized racism.

The strength of the positive correlation between aggression and microaggressiveness varied by ethnoracial group, with the magnitude being the highest among Hispanic Americans, particularly non-White Hispanics, and the lowest among Asian Americans. It is interesting to speculate possible explanations for this discrepancy. On the one hand, it may be that aggressiveness and anti-Black microaggression likelihood are collateral outcomes of an increasingly discriminatory climate toward Hispanic Americans in the United States during Trump’s presidency (Crandall et al., Reference Crandall, Miller and White2018), which among non-White Hispanic Americans may be considered a means of group preservation (Brewer, Reference Brewer1999). On the other hand, among most Asian American communities, the cultural emphasis on minimizing social disharmony or emotional expressions that may disrupt intra- and inter-group cohesion (Wei et al., Reference Wei, Su, Carrera, Lin and Yi2013) may cause heightened inhibition from committing anti-Black microaggressions, even with increases in aggressive tendencies.

Practical implications

This study finds that racial microaggressions are a common form of aggression that might be expressed between different ethnic groups as well as within those groups. Given the detrimental effects of microaggressions on others, interventions to reduce the commission of microaggressions are necessary (Williams, Reference Williams2020b), and this is true for racialized people as well as non-racialized people. This study finds that that people of colour who commit microaggressions have greater aggressive tendencies.

Aggression is a behaviour intended to punish or control others, and can be conceptualized as a product of anxiety in the perpetrator in the face of feeling vulnerable to a threat. People prone to verbal aggression believe that verbally aggressive messages are a justified means of addressing that threat (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Anderson and Horvath1996). Aggressors of colour may be uniquely motivated by feelings of vulnerability, due to being minoritized, and so they use microaggressions as an attempt to control other people of colour into conformity. They might exhibit microaggression against those in their own group who they deem are making their group ‘look bad’ by fulfilling negative racial stereotypes as dictated by the dominant culture (i.e. microaggressions as a form of within-group aggression in response to the threat of negative group portrayal). As such, microaggressions may be aimed at stopping those behaviours to reduce unfavourable appraisals of the minoritized group. In a focus group study of racial microaggressions, one Black participant shared that, ‘if I put forth a bad example, they’re all going to judge Black people to be this way’ (Johnson-Ahorlu et al., Reference Johnson-Ahorlu2013). Given the perception that all Black people may be judged for the actions of one, there may be within-group pressure to force others to conform to the dominant culture and exhibit anti-stereotypical behaviour. As such, a Black professional might, for example, make a microaggressive jab at another Black colleague for wearing their hair in a natural style that is considered too unruly for the workplace.

Likewise, minoritized peoples may feel their culture is threatened when members of their group assimilate to the dominant culture. This may be particularly true for Hispanic Americans as many are able to identify as White. A microaggression may be provoked when a minoritized person feels that another in their group is too assimilated, for example in the case of a Hispanic American who levies a microaggression towards another Hispanic American that only speaks English, because they are angry that the person has seemingly abandoned their mother tongue. Conversely, one Hispanic scholar recounts stories of being rejected at school by other Hispanic youth who felt embarrassed in front of White peers by being spoken to in Spanish; ultimately, she stopped speaking Spanish to suffer fewer microaggressions at school and lost her first language entirely (e.g. Steketee et al., Reference Steketee, Williams, Valencia, Printz and Hooper2021).

Ultimately, these problems are caused or exacerbated by a culture of White supremacy, and should be framed as such, rather than the failings of those targeted. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) interventions for perpetrators might include psychoeducation about the systemic and insidious nature of racism, the harm caused by microaggressions, and helping offenders recognize commonalities in the values and struggles of all racialized people (e.g. Williams et al., Reference Williams, Kanter, Peña, Ching and Oshin2020). CBT interventions for aggression may be warranted, and successful approaches have included relaxation techniques to cope with anger, assessing cognitive distortions and faulty core beliefs, cognitive restructuring, practising appropriate assertiveness, and learning new problem-solving skills (e.g. Costa et al., Reference Costa, Medeiros, Redden, Grant, Tavares and Seger2018).

Minoritized people of colour who are victims of microaggressions from other people of colour may experience shock and hurt of a greater magnitude than if the offence had been perpetrated by a member of the dominant culture (Gómez, Reference Gómez2020). Counsellors have identified within-group racist comments as contributing to race-based trauma in their clients of colour (Hemmings and Evans, Reference Hemmings and Evans2018). Victims may question if they did anything to deserve these offences. Clinicians should recognize these as problems within the perpetrator (ultimately systemic oppression that becomes internalized) and not shortcomings of the victim. Therapists should provide support and validation for victims, and encourage exercises to positively increase self-esteem, ethnic pride, and feelings of self-efficacy (Williams, Reference Williams2020c). Cognitive restructuring for internalized racism can be potentiated by challenging of negative stereotypes and advancing positive affirmations about the client’s ethnoracial group (Williams, Reference Williams2020c). Additionally, clients can keep a log of microaggressions experienced during the week and the automatic thoughts elicited, and process these with the therapist in session. Clients and therapists can role-play effective responding to microaggressions (e.g. responding to an offender with, ‘What you just said says more about you than me’) so that clients feel better able to manage these unpleasant situations when they arise (e.g. Ching, Reference Ching2021; Houshmand et al., Reference Houshmand, Spanierman and De Stefano2019; Sue et al., Reference Sue, Alsaidi, Awad, Glaeser, Calle and Mendez2019). Likewise, clients should learn to be appropriately guarded around people of colour who commit microaggressions as this could indicate aggressive tendencies.

Encouraging positive cross-racial relationships is another way to build resilience. Research has shown that the effects of ethnic discrimination perpetuated by peers from other racialized groups can be buffered by the strength of friendships with individuals from those same groups. For example, Benner and Wang (Reference Benner and Wang2017) found that among adolescents of colour (85% Latino American, 11% African American) friendships across ethnic groups moderated the effects of peer ethnic discrimination on well-being and school outcomes. The authors suggested that increased inter-group contact via peer relationships (and presumably, increased empathy for out-group members; Pettigrew and Tropp, Reference Pettigrew and Tropp2008) is likely to alter perceptions of discriminatory interactions from such peers as more benign. Most Americans have racially homogenous social circles (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Navarro-Rivera and Jones2016). Therefore, clients suffering the impact of microaggressions from other people of colour might be supported in further diversifying their friendship networks. If clients are fearful, therapists can implement social anxiety exposures to address inter-racial anxieties (Ching, Reference Ching2021).

Limitations and future directions

Although this study included a large and diverse national sample of adult respondents, there were some limitations. Amazon mTurk data are less representative than national probability samples, although the use of Turk Prime does permit more specificity in selecting respondent demographics (Huff and Tingley, Reference Huff and Tingley2015; Litman et al., Reference Litman, Robinson and Abberbock2017).

Although microaggressions may stem from underlying aggressive tendencies, it seems likely that some degree of microaggressive behaviour is caused by other factors as well, such as high anxiety, poor social skills, or a lack of exposure to other cultures. These possibilities should be further explored. Fears rooted in pathological stereotypes may be maintained by persisting racial segregation in various settings. Future studies might examine cultural knowledge and multicultural experiences as mitigating factors. Cultural intelligence has been postulated as a factor in these differences (Williams, Reference Williams2021), and measures like the Cultural Intelligence Scale (Van Dyne et al., Reference Van Dyne, Ang, Ng, Rockstuhl, Tan and Koh2012) may be useful in examining this further.

Finally, this study only assessed anti-Black microaggressions. Other types of microaggressions are also a source of problematic interactions, including those impacting other ethnoracial groups, sexual and gender minorities, people from stigmatized religious traditions, and disabled individuals. Future studies should examine aggression as a predictor of these types of microaggressions as well, and microaggressions should be studied in other national contexts.

Conclusion

Racial microaggressions appear to be expressions of aggression on the part of offenders – a form of aggressive behaviour that is generally socially unacceptable, irrespective of the race or ethnicity of the person perpetrating the act. Racial microaggressions should not be assumed to be the result of negative affect or internalized racism, even when levied by people in the same ethnic group as the target. More research is needed to fully understand motivations of offenders and the best way to reduce microaggressions to mitigate harms done.

Key practice points

-

(1) Racial microaggressions maybe committed by people from any racial or ethnic group.

-

(2) Therapists should recognize that microaggressions are a form of aggression, and not simply attributable to negative affect.

-

(3) The connection between anti-Black microaggressions and aggression is strong in African Americans and Hispanic Americans but less so for Asian Americans.

-

(4) When people of colour commit racial microaggressions, it may not be indicative of internalized racism but rather feelings of threat and vulnerability.

-

(5) Microaggressions should be addressed in therapy.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X21000234

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jamilah George, who provided assistance in the initial stages of this project, Destiny Printz and Noor Sharif who helped coordinate data collection, and Sophia Gran-Ruaz for help with clinical examples.

Financial support

This research was undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs Program, Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), grant number 950-232127.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethical statement

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS.

Data availability statement

The data presented in this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

M.T.W. devised the project, designed the protocol, and outlined the paper. T.H.W.C. conducted the data analysis. All authors were involved in collecting the data. J.G. managed the data. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.