Introduction

Overview

Transitioning between roles can be a complex process in a mental health context (see Currie et al., Reference Currie, Finn and Martin2010). Learning in mental health is never independent of professional ideals, which may interfere with an evidence-based delivery professional practice. Training in CBT is designed to build on core skills developed through previous core professional training (e.g. mental health nursing, social work) or equivalent, which needs to be evidenced for accreditation purposes. Experience in previous roles is therefore necessary, but some aspects may not fit within cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) paradigms.

Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) has established an evidence-based programme of psychological interventions at a primary care level in the UK. Training for high-intensity therapists (primarily CBT) is delivered over a year, with applicants coming from core professional backgrounds or equivalent. IAPT training represents a paradigm shift in knowledge, identity, coping strategies and practical applications. It is known that different core professions start with different levels of reflective skills and competency in CBT, which appear to be poorer when specific areas of existing knowledge conflict with CBT (Wilcockson, Reference Wilcockson2018). If learning processes are fundamentally different between professions, such processes are likely to impact upon what is learned in CBT, and on the CBT practice of the students.

Review of existing theory and research, and rationale for this research

There is limited theory, and a paucity of evidence, in the area of core professions transitioning to IAPT. Piaget and Cook (Reference Piaget and Cook1952) theorised that intelligence and cognitive development are dependent on children successfully transitioning and adapting to change. They noted that most learning is not solely determined by a new environment, but by a process of interaction between new environments and prior experiences. They developed the concepts of assimilation (fitting new information into existing experience) and accommodation (modifying knowledge to fit with the new environment). The areas of work–role transitions are relatively well developed from a theoretical perspective but are usually written from the perspective of an organisation and its objectives (see Ashforth, Reference Ashforth2000). However, it is also difficult to fully understand the transitional process in this context without taking intrapersonal conflict and emotional experiences into account, as intrapersonal conflict at a practical and ideological level impacts on therapeutic delivery. The understanding of the problem from the perspective of the individual and the core profession is under-researched.

Transitional psychology approaches originate from work on bereavement and family crisis. They were developed as a theoretical approach to transitions by Adams et al. (Reference Adams, Hayes and Hopson1976), who adapted the principles of the grieving model (Kubler-Ross, Reference Kubler-Ross1969), to transitions. One of the advantages of this model is that it incorporates the personal experience of role change. It has a strong humanist emphasis in orientation.

Psychodynamic approaches emphasise the development of the person as a therapist, and factors leading to a successful outcome. There is also a model of the acquisition of skill and experience from novice to experienced therapist, of which the most important factor appears to be a move to independence (Rønnestad and Skovholt, Reference Rønnestad and Skovholt2003). One important study in this area (Carlsson et al., Reference Carlsson, Norberg, Sandell and Schubert2011) researched therapists’ professional self-development during training. One relevant finding was that there was a desire to move away from the pre-formed professional self, and also demonstrate this progress to teachers and have it acknowledged.

The generic CBT literature on student development during training is relatively well established. CBT requires learning at the declarative, procedural and reflective level for the appropriate skills to become embedded (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Turner, Beaty, Smith, Paterson and Farmer2001; Chaddock et al., Reference Chaddock, Thwaites, Bennett-Levy and Freeston2014). This is not known to be a linear or smooth process, and perceptions of competence fluctuate during the transition process (Bennett-Levy and Beedie, Reference Bennett-Levy and Beedie2007). Self-practice and self-reflection (SP-SR) add to traditional teaching methods (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Turner, Beaty, Smith, Paterson and Farmer2001) in terms of helping students understand CBT from the inside (client’s view; Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Lee, Travers, Pohlman and Hamernik2003) and promoting self-awareness and a commitment to personal development. A number of refinements to SP-SR have been undertaken (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2012).

While the generic literature on trainee therapist development is relatively developed, the impact of professional background is negligible in the research. Attempts to address the specific issue of transition from core professions to the IAPT role are limited to two studies. Robinson et al. (Reference Robinson, Kellett, King and Keating2012) analysed nurses’ experience of the IAPT transition, retrospectively. Important data, such as the role of supervision, could be gleaned from the research. However, themes rather than processes (i.e. the links between the themes) was the main focus of this research. The study was also limited by the issue of retrospective inference: studies indicate that memory changes and is filtered through current experience and is often ‘edited’ later (Butler et al., Reference Butler, Rice, Wooldridge and Rubin2016); and the intensity of the transitional process may be better captured ‘live’. The other study (Binnie, Reference Binnie2008) consists largely of a commentary on the process from a student: a single case study on oneself. Important issues in this study included a lack of psychotherapeutic practice in nursing, and a misunderstanding of existing competency leading to a change in expectations. The study only focuses on nursing and does not provide a comparison between professional roles and non-professionalised roles. Binnie’s report also requires repetition with a larger number of participants. A study by Wolff and Aukenhaler (Reference Wolff and Auckenthaler2014) on CBT therapists in Germany identified conflicts in training for psychotherapists with a strongly pre-formed identity, and notes that complete transition is not guaranteed.

The following study proposes to resolve this limited understanding by constructing the transition processes of three different groups training to be IAPT (primary care CBT) therapists: mental health nurses, counsellors and KSA (unqualified but with Knowledge, Skills and Attitudes in core therapeutic skills equivalent to the core professions described; see BABCP, 2018). This is achieved by generating a theory of transition for each core profession from the source data.

Research on identity and practice in the core professions

This section highlights cultural rituals, practices and issues of ideological emphasis within each of the different core professions; particularly emphasising areas of potential conflict.

Mental health nursing is known to have conflicts between the general, caring ideals of the profession and the specific, professionalised, medicalised and evidence-based practices (Chan and Rudman Reference Chan and Rudman1998). Even where a caring practice is adopted, it is delivered through a task discrete, managerial lens (Deacon and Fairhurst, Reference Deacon and Fairhurst2008; Gijbels, Reference Gijbels1995). While therapy, supervision and reflective practices are aspired to, evidence suggests that there is neither a framework nor adequate time to adopt more therapeutic aspects of the role, such as therapeutic engagement, supervision and reflective practice (Bray, Reference Bray1999).

Counselling and psychotherapy [defined in this study as being accreditable with the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy (BACP) in the UK] is a profession with relatively broad ideals but held together internationally by key underlying principles. Models vary, but there is a strong adherence to the centrality of the client in all interventions which appears to supersede the adherence to any one model. There is an interest in the role and vulnerability of the self (e.g. Reupert, Reference Reupert2006), allegiance to therapeutic processes (e.g. empathy) and the therapeutic relationship (Bor et al., Reference Bor, Miller, Gill and Evans2008). Some counsellors consider CBT to be in conflict with these values (House, Reference House2011). The relative female influence on the profession is important, not only because of the number of women in the profession (approximately 80%; Brown, Reference Brown2017), but because of the importance of both traditionally feminine values and feminist ideology (De la Paz, Reference De la Paz2011). Examples of these values in practice include an interest in a gut response, rather than a positivist response to the client (e.g. diagnosis), the independence from interference in the therapeutic process, and the role of advocacy for the client (Henderson, Reference Henderson2010).

Knowledge, skills and attitudes (KSA) trainees have an equivalent level of skill without a professional identity. As a result, there are limited established ‘cultural’ features to this group, although some have undertaken psychological wellbeing practitioner (PWP) training, which is in itself a relatively new role. The absence of a core professional identity may be a relevant feature of transitioning.

CBT also has its own culture that includes a theoretical model, a reasonably high congruence between theory and practice, formulation, use of measures, a present focus, an emphasis on evidence-based practice, self-reflection and supervision, and a structured approach to changing emotions through cognitions and behaviours (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Mills, Mulhern and Short2010; Westbrook et al., Reference Westbrook, Kennerley and Kirk2011). It incorporates and integrates empirical and humanistic ideas, ensuring both positive and conflicting relationships with the core professions and with psychiatry and management, and a resolution of these conflicts is a feature of the transition process.

The existing research indicates that counselling and nursing have clear cultural features, some of which are similar and some of which contrast with each other and with CBT. In particular, the emphasis on positivist practice in mental health nursing and humanist practice in counselling is tangible from the research. The lack of known cultural features of the KSA group allowed for a comparison of transition processes between core professions with prior expectations and culture affecting CBT principles and practice, and those that do not.

This study aimed to examine the experiences of members of different core professions of the process of transitioning to IAPT and develop a theoretical understanding of these experiences for each professional group. While there is no attempt to analyse the differences between the different core professions, some of the main features are described together in a table for comparison.

Method

Participants

The research addresses how each core profession transitions to CBT, and this is addressed by the analysis of reflective reports for seven IAPT students from each core profession independently, sampled across seven cohorts from one university between 2008 and 2016. The number of participants in each group was determined by data saturation; six were initially sampled with scope for up to 10. Nursing demographic data was four females (57%) and three males, with a mean age of 34 years, and a mean of 12 years of professional experience. Counselling data revealed six female (86%) and one male participant (representing similar ratios in the counselling profession more broadly; Dalziel, Reference Dalziel2009), with a mean age of 41 years, and a mean of 13 years professional experience. While age is possibly an extraneous variable in the counselling group, it is known that age and gender are not contributory factors in explaining professional differences in initial CTS-R skills, but core profession is (Wilcockson, Reference Wilcockson2018). The KSA group included four females (57%) with a mean age of 31 years. Precisely what constituted professional experience varied considerably in that group and collecting further qualitative data relating to their experience would have risked compromising anonymity, therefore it was not collected.

The reflective report is a mandatory requirement of the course, based on a student’s learning diary taken across the training year, allowing for personal and professional reflections on the transition and learning process as they occur. It was a 5000-word assignment, formally assessed towards the end of the course. Although evidence of learning and developing across the year was expected to be evidenced, no framework was set for how this should be achieved or communicated. There was no mandatory requirement to discuss the clinical background and the role that played in the transition, although all participants did so. The process of being both mandatory and evaluated could have caused a reticence in reporting openly, such as being critical of support, but this does not appear to have been the case from the samples. This is, however, acknowledged as a limitation.

Procedure

Permission to access the participants was obtained from the course director, and ethical approval obtained from the appropriate university. The course director then explained the research to the students. Reflective reports were collected from consenting participants by the course director (gatekeeper) who anonymised them, retained data from core profession, age range, and gender (e.g. nurse, 25–35, female), and released all of the journals with the appropriate consent to the researcher. The core professions were mental health nursing, counselling and KSA. Several core professions (occupational therapy, social work, chartered psychologist) did not have sufficient consenting participants. Three age groups (25–34, 35–44 and 45–54) represented the range of the participants (age 25–54 years). The researcher then chose six journals per core profession – initially at random – with the intention of taking a further case later if required. Stratified sampling was undertaken in the nursing group to ensure that there was a mixture of in-patient and out-patient nurses.

Each report was analysed using a traditional grounded theory (Glaserian) methodology (Glaser, Reference Glaser1998) according to the methodology of Simmons (Reference Simmons2008). Data for each core profession were analysed independently of each other. The written nature of the data allowed for a focus on the content of the data only, and the lack of opportunity to follow-up with participants limited the number of other qualitative methodologies. The ability to explore whether there was a systematic learning/transition process is suited to grounded theory where categories have a relational component, not just a descriptive one.

At the data collection stage theoretical sampling was conducted; initial sampling for theory construction to screen for conceptual category frameworks (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2014). At this point, one sample from each core profession was analysed initially in order to identify some key core themes, improving the efficiency of the subsequent data search. However, no assumption that any sample is representative of a population, or that participants are equal in their ability to generate data, was made. These samples were also given to a supervisor to code in parallel to act as a check of competence and accuracy in the process.

It is recommended in grounded theory that the literature review is not written until after analysis (Walls et al., Reference Walls, Parahoo and Fleming2010). However sometimes a limited review can help the researcher understand the participant’s meanings, and a minimal overview of parts of the subject was undertaken. The research question at this stage remained broad in order to allow the relevant central themes and processes to emerge from the data. Glaser (Reference Glaser1992) considers it important that the data is not ‘forced’ too early.

Data analysis was then conducted on a sample of five reflective reports for each core profession. Open coding was undertaken: i.e. describing the data in a way that is as close to the original coding as possible. Data is de-constructed into units that form the minimum unit for theory construction. The units are described in the form of a professional label (e.g. N for nursing), participant identification number (e.g. 5), page (e.g. 12) and line(s) (e.g. 11–17). For example: N5/12.11–17.

The researcher sorted the data to identify the most recurrent themes that were likely to be central or critical to the theory, and made initial attempts to identify a ‘core theme’ (if present). Through the process of further refinement of concepts through memo-ing, and comparisons for similarity in both content and process, the concepts were refined until the point of saturation, that is, until all relevant data fits with a concept (Birks and Mills, Reference Birks and Mills2015). Saturation was achieved after seven participants for each core profession.

The next stage involved comparing each concept with other concepts to establish similarities, differences and relationships. Also, there was a check for meta-themes, that is, features that a range of concepts had in common in order to build up a number of key theoretical concepts. These broader concepts were then compared with each other in terms of relationships (e.g. causal, symbiotic, independent, alternative, and necessary for, precedes/triggers, sufficient for, etc.). A refinement of these concepts assisted with the development of a mid-level theory.

The mid-level theory, in this case, was a ‘work in progress’ theory derived wholly from the data; although there is, of course, an acknowledgement of the researcher’s understanding of theory in respect to this. After this, the researcher conducted a literature review of the key areas identified, and undertook a process of comparing concept with theory, concept with concept, and data relationship with theoretical relationship. The method used was memo-ing (Birks and Mills, Reference Birks and Mills2015). Memos serve as a record of the development of the research and typically include procedural decision making, content development, reflections on the overall research process, and the researcher’s feelings and assumptions about the research. This provides an audit trail of the methodological development for replicability, and also prevents the researcher from becoming lost in the research, having to re-visit ideas at specific points in their thinking if necessary. A further report from each sample was then analysed to check for theoretical saturation, which was achieved. Once a theory was established, the researcher then returned to the individual cases to see if the theory fitted at the level of the individual and whether negative case analysis was necessary. There was one counselling report which did not fully fit the theory where a very limited adjustment to CBT occurred. Very strong ideological objections to CBT remained present throughout, and the participant did not practise CBT after graduating.

Results

Mental health nursing group

A model of transition for the nurses is described in Fig. 1. The process of transition was initially very difficult for nurses because the underlying philosophy in CBT was not grasped by the nurses. The task-based expert role used in nursing was assumed to continue in CBT.

‘Early in the training I seem to believe that “declarative knowledge” will be enough to be told I’m a good therapist.’ [N60/8.10]

Figure 1. A model of mental health nursing transition to CBT.

One participant (N8) was less professionalised than the other participants, having qualified more recently and working in the community with less chronic clients, and was interested in the therapeutic relationship. However, the above lack of understanding of therapeutic processes and poor initial self-awareness was also present with this participant. This appears consistent with ethnographic research suggesting that nurses lack a framework or support to remain with emotional discomfort in a therapeutic context even if they wish to (Bray, Reference Bray1999).

‘I was confident that I already had a good grasp of the CBT approach. This was blown out of the water around week 4 of seeing clients.’ [N8/15.3–5]

The idea of consistency between personal and professional lives was also problematic, as nurses had previously described playing a role in their professional lives that was separate from their private lives, and the need to be authentic was challenging. Nurses also struggled with exposure to evaluation by others or themselves (e.g. supervision and reflective practice), which is perhaps surprising given identification with these concepts and the importance of adherence to positivist approaches.

Nursing participants appeared to initially manage this conflict by superficial adherence and emotional avoidance. This avoidance is extreme at times and attempts to ‘carry on as normal’ are made. No skills other than professionality (diagnosing, labelling, playing a role) and emotional distancing are available to the nursing participants in order to deal with emotions. However, the nature of the training course drives the conflict and forces confrontation through cognitive dissonance in the form of submitted tapes for evaluation, supervision of practice, etc.

‘… it was actively encouraged … to describe and document how incidents and events affected me as a person… [this seemed] somewhat superfluous to learning, feeling like crying over spilt milk, and I did experience a strong sense of resistance in the early stages.’ [N1/6.9,10–11]

This dissonance invokes a crisis of confidence and competence. This transcends all areas of the nursing participants’ life, which is an uncontaining experience. The majority of participants mention being able to remain in control of their personal life previously by ‘playing a role’ at work and keeping personal and professional lives separate.

The dissonance described above is resolved by self-practice and self-reflection (SP-SR), a fundamental part of the training. Both nursing and CBT are used to approach SP-SR, which is undertaken mainly using the content of CBT, but the process of nursing (a task-driven approach for all participants initially, with a lack of an essence of ‘the person of the therapist’). All nursing participants invest fully in the process of self-practice, albeit in a task-driven and possibly emotionally distant manner, by firstly formally identifying thoughts, feelings and behaviours. Cognitions fall into four broad categories, failure to cope (e.g. N5/2), defectiveness, incompetence and failure (e.g. N8/3), negative judgement from others (e.g. N7/7) and ‘getting it right’/perfectionism (N2/9).

‘Sound of my voice on the tape … I sound so young, how can clients take me seriously? … Avoided taping myself …’ [N8/5.9–10,10–11,11–2]

The application of trying to challenge thoughts and behaviours for the nursing participants is very technical and structured, borrowing process from the nursing approach. About twenty examples of this were present in the reports across a wide range of triggers and using a wide range of strategies working to change them.

‘How I did address this was to apply CBT skills, weighing up the evidence for the belief “I’ll be found out as a failure”. I weighed up the evidence and highlighted positives about the process report and CTS-r.’ [N7/8.24–26]

Nurses invest fully in this process; one reason appears to be that some participants view CBT as a progression from nursing. CBT practice is adopted over nursing practice where there is conflict in all documented examples, and this is consistent with social learning theory where one profession is considered to be superior by participants. Where nursing practice adds to the CBT role, it is often maintained. An example of this is knowledge of medication (if raised by the client). The support of supervisors and acceptance by others of the crises and transition difficulties are influential in the completeness of the transition.

Counselling group

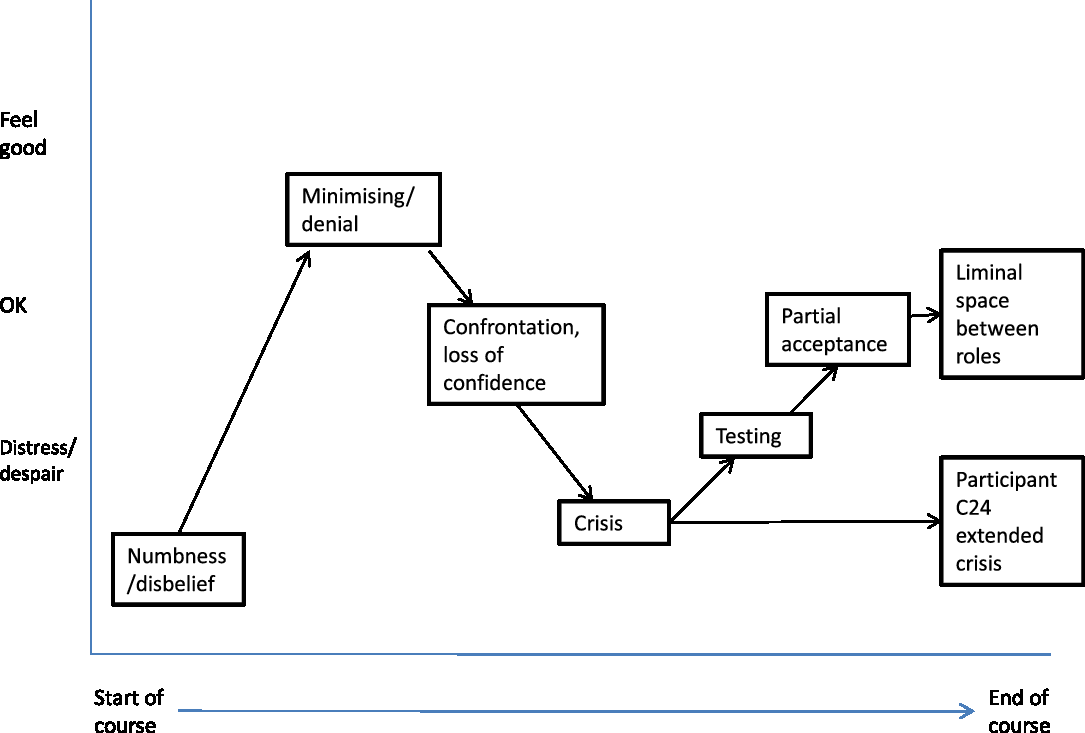

The seven counsellors included in this study all were accredited or accreditable by the BACP. Most were predominantly humanist in orientation but used some CBT skills; one was historically psychodynamic in orientation. In the process of searching for theory comparable to the students’ experience, Williams’ (Reference Williams2008) transition loss model was assessed and adaptions made (with permission) to explain the transitional process for the counsellors. Please see Fig. 2 for a theoretical model.

Figure 2. A theoretical model of counselling participants’ transition to CBT (acknowledgements: Adams et al., Reference Adams, Hayes and Hopson1976; Kubler-Ross, Reference Kubler-Ross1969; Williams, Reference Williams2008).

Figure 3. KSA grounded theory model of transition to CBT.

As with the nursing participants, there was an expectation among the counselling participants that they could complete the course without fundamentally having to change practice: however, much higher levels of loss were experienced than anticipated in the early stages of the course. Loss was a significant theme for all seven members of this group: not of professional identity, but certain core values. The loss of role, identity, purpose and autonomy are all present (Worden, Reference Worden2018) (see Table 1), especially in regard to the right to practice freely and without judgement according to the needs of the client in the room. The freedom to practise CBT according to the desires of the therapist was not present in the early stages of teaching, leading to a direct conflict with their existing values. There was also significant difficulty with seeing concepts in isolation, and a preference for a ‘holistic’ processing style (Eide and Eide, Reference Eide and Eide2012) conflicting with the conceptually detached principles of CBT initially.

Table 1. Factors exacerbating difficulties in transition for counsellors (paralleling loss in Worden, Reference Worden2018)

There was initially an avoidance addressing these issues and attempts to ‘carry on as normal’ leading to a small reduction in problematic emotions. However, as cognitive dissonance deepened the conflict, the participants could no longer contain emotions. A conflict of expectations led to a personal crisis as with the nurses, but an emotional emphasis in both experience and resolution within the sample meant that it was experienced more deeply and ideologically.

‘I felt that I had sold out – traded in something vital but didn’t really like what I had in return.’ [C21/8.27–8]

Counsellors’ historical ways of coping – such as personal therapy – were not supported on the course and were crowded out by the need to explore other methods (such as self-practice and supervision in assignments). This led to a search for alternative ways of coping. Counselling participants turned to CBT in an attempt to cope and resolve distress. However, unlike nursing participants, the counsellors placed themselves in the role of a client and considered what clients could take from a CBT in this context. The availability of self-reflection and the availability of parallel process as a concept facilitates this learning process. There was a strong emphasis on the nature of the client experience, and flexibly applying CBT to respond to this.

‘I was lost and ungrounded … and the parallels with my clients were obvious.’ [C23/5.4]

The resolution for counselling participants was almost entirely experiential. When comparing theoretical ideas, all conflicts were resolved in favour of counselling ideals (n = 4), whereas when experimenting with the practice of CBT 94% of examples demonstrated significant movement towards the use of CBT practice (n = 32).

‘I was surprised that the structure of the formulation seems to have helped contain the client.’ [C25/7.23]

The overall outcome of the counselling participants’ transition was a mixture of assimilation and accommodation (Piaget and Cook, Reference Piaget and Cook1952), and the investment placed into learning the role appeared to increase identification with CBT, consistent with Cooper’s (Reference Cooper2007) view on dissonance resolution (i.e. where there is a conflict between an ideal and behaviour, the outcome generally favours the ideal adapting to the behaviour).There was an acknowledgement of personal growth through the experience and from the counselling participants, and a resolution of some conflicts, but not others. The fact that some deviation from the models according to client formulation is allowed assists the process for some. Some of the more positivist aspects of CBT were not adopted, and some aspects of autonomy of practise were retained.

‘I think I might always struggle with the need for distance and the business-like approach of CBT.’ [C25/12.18–20]

These conflicts remain but are experienced from within an identification with CBT, not from outside it. The former counsellors wish to help CBT become user-friendly from within the framework. Reflective practice is fully adopted, albeit using a client-centred stance.

KSA

It is noticeable that those without a core profession often lack the confidence of their peers as a result of this, even though they often have more experience than their professionalised peers. The lowering of expectations of their knowledge or skill in CBT, or the simplicity of transition may have been influential in a milder transition experience than their professionalised peers. Please see Fig. 3 for a grounded theory model.

Members of the KSA group experienced similar stressors to nurses and counsellors, such as fear of recording, academic challenges, work–life balance, etc. However, there was no avoidance (nursing group) or emotional amplification (counselling group). Instead, there was an openness to experience, and observation of the difficulties experienced is broadly accurate with some self-protection from negativity. Any difficulties – such as perfectionism (a common trait in this group) – were held at the individual level and not at the level of professional identity. Negative distortion and emotions were objectively noticed quickly and efficiently, but the positive attitude and lack of pre-conceived expectation led to a quick availability of an alternative perspective in this sample. Therefore, few biases were present to interfere with cognitive processing, consistent with CBT theory (Mobini and Grant, Reference Mobini and Grant2007).

The coping style was of a vigilant, not avoidant, nature which is known to be a significant predictor of improvement in some clinical situations (Price et al., Reference Price, Tone and Anderson2011). Reflection is broadly accurate, and generalisation is very high.

‘[IAPT] has given me a greater awareness and appreciation of the positive things in my life…’ [K37/18.4–5]

Gratitude for being able to undertake the course, and the support provided, was palpable within the sample, and this gratitude was linked to positive outcomes, consistent with therapeutic findings (Kashdan et al., Reference Kashdan, Uswatte and Julian2006). Re-integration of CBT with the client’s personal life was relatively effortless and the transition process was completed.

Universal and contrasting factors among the core professions’ transition

There were a number of universal factors present in the transition from core professional to CBT therapist. Stressors were consistently present across all professions, although the experience was partly influenced by the coping style of a core profession.

The main emphasis for resolving transition dissonance was through the acquisition of knowledge, technical skills and a deliberate reflective process incorporating cognitive and experiential learning (Chaddock et al., Reference Chaddock, Thwaites, Bennett-Levy and Freeston2014). However, for many of the nursing and counselling groups, reflection and skills development were resisted initially and did not start independently. Therefore, an additional factor is necessary to invest the student in the reflective process, which appears to be cognitive dissonance. If, for example, a counsellor does not believe in adopting a CBT approach in a session, but is required to do so for a CTS-R, they are seen by others to be acting inconsistently. Cognitive dissonance postulates that this conflict will be resolved by changing beliefs rather than behaviours (Cooper, Reference Cooper2007; Festinger, Reference Festinger1957) in this situation and this appears to be the case here. After this, the students adopt reflective practice and learning becomes embedded. Although reflection is likely to be a necessary condition for transition, it may not always be sufficient.

Self-practice in CBT is acknowledged across all core professions as being important and is adopted as a protective factor to deal with stressors by the end of the course. There are slightly different approaches across professions, but the same model is broadly adopted. This skill takes some time to acquire and will be discussed in more detail shortly. The extent of perceived positive experiences and resources (client feedback, supervisory, teaching and personal support) are universally influential, and these are generally present across most of the sample. All groups noted that the final stage in the transition was to re-integrate what they had learned into their existing experience and values: some of which had been ‘unlearned’, and that this is a complex process.

Differences in transitional experiences are present at the level of the core profession (see Table 1). The fact that CBT is aspired to (nursing and KSA) rather than equal to or conflicting with some values (counselling) appears influential in a positive and complete transition and this is consistent with existing theory (Crawford et al., Reference Crawford, Brown and Majomi2008; Ellemers et al., Reference Ellemers, Van Knippenberg and Wilke1990). Professional ideals in both nurses and counsellors appear to lead to overconfidence initially, making the transition more emotionally complex and with a greater delay. Resolution of transitional conflicts are employed according to pre-existing core professional styles (technique focus in nursing, client focus in counselling, or multiple strategies in KSA), and this influences the style of CBT delivery post-transition.

Professional coping strategies had a significant influence on the overall process. Nurses employed professionalism or emotional distancing as a stress management strategy. This involved playing a professional role rather than being authentic, and using formal approaches such as evidence focus, medication, etc. to manage any personal emotional distress. Counselling participants allowed and encouraged discomfort and allowed for the personal self and professional self to be fully integrated. Personal therapy and peer support were influential protective strategies. The coping strategies of nurses and counsellors were not permitted prior to being replaced by self-practice, and the period of absence of coping strategies parallels the extent of the crisis experienced in both of these core professions. The KSA group, by contrast, had not been taught alternative coping strategies, and their dependence on self-reliance was consistent throughout the training, which reduced the extent and effect of any emotional crises.

Implications – mental health nurses

Participants were over-confident of their ability in CBT because although the basic content of CBT was understood, the process was not. Over-confidence in the existing role due to professional reinforcement of approach led to inflexibility in adaptation to new roles. Teaching and supervision are likely to help address this. Further research is needed from other perspectives to confirm this.

Nurses also expected to be able to continue with previous professional strategies for emotional self-regulation (professionality and emotional distancing); this is incompatible with CBT. The replacement strategy for emotional self-regulation (SP-SR) needs to be taught much earlier in CBT training. If there is a gap between loss of the old coping strategies and the development of new ones, a crisis occurs and learning is delayed.

Where there is dissonance between roles, CBT is adopted. This confirms existing theory (Tajfel and Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1986) and research (Van Zomeran et al., Reference Van Zomeren, Leach and Spears2010) that states where learning is aspired to or considered superior, transitions are more complete.

Participants separated theory and practice, and personal and professional selves. This confirms the existing understanding of the nursing role mentioned earlier. The integration of personal and professional selves is not typically part of the CBT curriculum. It is difficult to teach but requires awareness from lecturers and supervisors.

Participants practised according to the evidence base, but added previous nursing knowledge to the CBT role where CBT was less present (advising about medication, etc.). It is not clear whether the nurses added to the evidence base affected outcomes either positively or negatively.

Implications – counsellors

CBT is parodied initially by the majority of counsellors as being the opposite of counselling, particularly the positivist aspects. Course content and supervision support would benefit from adaptations to support counsellors with this conflict. Some of the investment in counselling ideals remain present at the end of CBT training, and the end-product appears to be a combination of counselling, CBT and the individual. CBT is practised in a more liberal way according to the evidence base, and further research is required to identify whether this affects client outcomes.

The process of emotional amplification and (counselling) colleagues-as-support (previous coping strategies) maintains the antagonism towards parts of CBT and delays the start of transition through lack of dissonance. Appropriate course content, the teaching of self-practice and availability of supervisory support all need to be present at an early stage. Supervision from the same professional background could be considered if available. Loss is consistently present and attempts to address loss are likely to facilitate transition, possibly through clinical supervision, self-practice and the use of role models.

Experiential learning resolves dissonance and leads to learning and reflection. This needs to be consistently applied at an early stage and throughout the training programme.

Implications – KSA

The lack of professional ideas and preconceptions facilitates transition despite similar learning and practice difficulties to the other core professions. Professional training needs to consider whether professional idealisations undermine work flexibility as roles change within and outside those professions.

Summary

This research has concluded that each professional background had different core professional factors in their approach to learning CBT and the transition process, and this influenced the outcome. This puts into question existing approaches to CBT training, and challenges existing perspectives on role transition and learning and delivering CBT. The study is limited by the small sample size and the use of a single university, although completed over many cohorts and practice settings. It is also limited in that only findings deemed important to the researcher were presented, and the subjective nature of the data is difficult to verify. Attempts have been made to overcome researcher-induced bias such as supervision, shared coding of one participant, and a reflective diary; however, bias remains a risk. Further research is required to assess whether clinical outcomes are affected and whether educational interventions can mitigate these problems.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Gail Steptoe-Warren for supervisory support, and Catalina Neculai for support with editing.

Financial support

None.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethics statement

All necessary ethical approval was obtained in the conducting of this research.

Key practice points

(1) Core professions have many features in common, but also have many features related to CBT and to learning approaches which differ from each other. This affects the transitional process.

(2) A strong core professional identity may delay learning if the conflicts between core professional identity and CBT are not addressed.

(3) The transition between previous strategies to cope with distress and alternative CBT coping strategies (e.g. SP-SR) is influential. A void of coping strategies where previous strategies is not allowed but new strategies not being embedded appears to increase the likelihood of emotional crises.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.