Introduction

Despite the high prevalence of depression and anxiety in family carers of people with dementia (Collins and Kishita, Reference Collins and Kishita2020; Kaddour and Kishita, Reference Kaddour and Kishita2020), many family carers have limited access to face-to-face psychological support due to various challenges. For example, family carers often spend long hours providing care, which can be equivalent to a full-time job (Jutkowitz et al., Reference Jutkowitz, Scerpella, Pizzi, Marx, Samus, Piersol and Gitlin2019; Kishita et al., Reference Kishita, Contreras, West and Mioshi2020; Wolff et al., Reference Wolff, Mulcahy, Huang, Roth, Covinsky and Kasper2017) and can exceed 100 hours per week (NHS Digital, 2017) making it difficult for them to leave their house, particularly if they are unable to identify other family members or friends to provide care while they attend in-person support. Family carers living in rural areas face further difficulties due to the lack of local services, specialist providers and public transport (Alzheimer’s Society, 2018; Samia et al., Reference Samia, Aboueissa, Halloran and Hepburn2014). The COVID-19 pandemic has made the situation even more challenging as many social services for people with dementia and their carers were temporarily closed due to the public health restrictions, leading to detrimental effects on carers’ mental wellbeing (Giebel et al., Reference Giebel, Lord, Cooper, Shenton, Cannon, Pulford, Shaw, Gaughan, Tetlow, Butchard, Limbert, Callaghan, Whittington, Rogers, Komuravelli, Rajagopal, Eley, Watkins, Downs, Reilly, Ward, Corcoran, Bennett and Gabbay2021).

Internet-delivered self-help interventions have the potential to facilitate access to treatment among family carers who are often unable to leave the care recipient unattended, as well as those limited by geographic and mobility constraints (Ottaviani et al., Reference Ottaviani, Monteiro, Oliveira, Gratão, Jacinto, Campos, Barham, de Souza Orlandi, da Cruz, Corrêa, Zazzetta and Pavarini2021). This mode of delivery also has greater cost-effectiveness than in-person support and can be provided either unguided or guided, where the participant receives tailored feedback from a trained therapist to support their self-learning. Previous literature suggests that internet-delivered guided self-help interventions could be more beneficial in improving mental health outcomes, such as depression and anxiety among different groups (including informal carers), when compared with interventions that utilise an unguided approach (Biliunaite et al., Reference Biliunaite, Kazlauskas, Sanderman, Truskauskaite-Kuneviciene, Dumarkaite and Andersson2021; Guay et al., Reference Guay, Auger, Demers, Mortenson, Miller, Gélinas-Bronsard and Ahmed2017; Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Destree, Albertella and Fontenelle2021).

Online therapists providing tailored written feedback in internet-delivered guided self-help interventions can vary from highly qualified professionals, such as trained psychologists and graduate students in the final year of a Clinical Psychology programme (Biliunaite et al., Reference Biliunaite, Kazlauskas, Sanderman, Truskauskaite-Kuneviciene, Dumarkaite and Andersson2021; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Glendenning, Hoon and John2016; Buhrman et al., Reference Buhrman, Skoglund, Husell, Bergström, Gordh, Hursti, Bendelin, Furmark and Andersson2013) to minimally trained therapists, such as undergraduate psychology students (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Glendenning, Hoon and John2016; Lappalainen et al., Reference Lappalainen, Pakkala, Lappalainen and Nikander2021). Therapists are required to be clear and concise when communicating with the patient via text messages online, while they also need to develop sensitivity in identifying what style of feedback suits the patient, and ‘reading between the lines’ of what the patient is writing (Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Bergström, Buhrman, Carlbring, Holländare, Kaldo, Nilsson-Ihrfelt, Paxling, Ström and Waara2008; Folker et al., Reference Folker, Mathiasen, Lauridsen, Stenderup, Dozeman and Folker2018). Furthermore, online therapists often find it challenging to build a good therapeutic relationship with their patient, which could decrease therapists’ confidence and motivation in delivering interventions virtually (Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Bergström, Buhrman, Carlbring, Holländare, Kaldo, Nilsson-Ihrfelt, Paxling, Ström and Waara2008; Bengtsson et al., Reference Bengtsson, Nordin and Carlbring2015; Mol et al., Reference Mol, van Genugten, Dozeman, van Schaik, Draisma, Riper and Smit2020; Thew, Reference Thew2020).

ACT is an evidence-based behavioural therapy, that aims to promote psychological flexibility – the ability to step back from restricting thoughts and approach or allow painful emotions; focus on the present and connect with what is happening at the moment; and clarify and act on what is most important to do and build larger patterns of effective values-based action (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Levin, Plumb-Vilardaga, Villatte and Pistorello2013). Recent randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of ACT demonstrated that in-person ACT delivered by highly qualified clinical psychologists can reduce depression and anxiety among family carers of people with dementia (Losada et al., Reference Losada, Márquez-González, Romero-Moreno, Mausbach, López, Fernández-Fernández and Nogales-González2015; Marquez-Gonzalez et al., Reference Marquez-Gonzalez, Romero-Moreno, Cabrera, Olmos, Perez-Miguel and Losada2020). A recent pilot study on internet-delivered unguided ACT for family carers of people with dementia showed that ACT can be delivered in a self-help online format and reduce depression among this population (Fauth et al., Reference Fauth, Novak and Levin2021). Another recent RCT, which explored the effectiveness of internet-delivered guided self-help ACT for informal carers aged 60 and over providing care to a spouse or child living with or without disease, demonstrated that internet-delivered ACT was effective in reducing depression (Lappalainen et al., Reference Lappalainen, Pakkala, Lappalainen and Nikander2021). However, only 26% of participants were caring for a family member with memory-related problems in this RCT. Therefore, the extent to which these findings are specifically applicable to family carers of people with dementia is unclear.

The current qualitative study was conducted as part of a feasibility trial offering internet-delivered guided self-help acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) to family carers of people with dementia (iACT4CARERS). The iACT4CARERS feasibility trial (Kishita et al., Reference Kishita, Gould, Farquhar, Contreras, Van Hout, Losada, Cabrera, Hornberger, Richmond and McCracken2021) aimed to test whether it is feasible to deliver internet-delivered guided self-help ACT within primary and secondary care services in the UK. Novice therapists, who were mainly assistant psychologists working in NHS services, were recruited and trained remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therapists provided weekly written feedback to family carers to support their self-learning online throughout the intervention. The findings supported feasibility, including recruitment and treatment completion, and demonstrated that therapists were able to provide immediate feedback to family carers, in less than three days on average for every session completed, which adhered to ACT principles according to the fidelity ratings completed by independent ACT experts (Kishita et al., Reference Kishita, Gould, Farquhar, Contreras, Van Hout, Losada, Cabrera, Hornberger, Richmond and McCracken2021).

Considering all the potential challenges online therapists can encounter, understanding the therapists’ in-depth views on the acceptability of delivery and identifying ways to improve their experiences is critical to further inform a full-scale effectiveness trial. Therefore, the key objective of this qualitative study was to understand therapists’ perceptions and acceptability of providing this new, internet-delivered, guided self-help intervention through a series of qualitative interviews. Guided by the theoretical framework of acceptability of interventions (TFA) (Sekhon et al., Reference Sekhon, Cartwright and Francis2017), the individual interviews explored affective attitude, burden, perceived effectiveness, and self-efficacy among novice therapists involved in its delivery.

Method

Participants

Eight out of nine novice therapists, who took part in the iACT4CARERS study were recruited from primary and secondary care services in the East of England region. Novice therapists did not hold any formal qualification in clinical psychology or cognitive behaviour therapy. They were mainly assistant psychologists providing clinical support (e.g. carrying out neuropsychological assessments) under the direct supervision of a qualified clinical psychologist (see Table 1). Five of them (62.5%) had no previous experience in learning ACT. Two to eight family carers (mean age=62.0; SD=10.2) experiencing mild to moderate anxiety or depression were assigned to each therapist during the trial. One primary and two secondary care services that took part in the feasibility trial agreed on the number of family carers to be allocated to each therapist depending on their workload at the start of the trial. Family carers recruited at each service were sequentially allocated to therapists until the number reached the agreed limit. Therapists were eligible to take part in the interview regardless of whether their allocated family carers completed all online sessions or not.

Table 1. Characteristics of participants

NHS, National Health Service; ACT, acceptance and commitment therapy; therapists’ previous experience in ACT was limited to attending a 1- or 2-day workshop/training course and not using this type of therapy in their clinical practice.

The intervention and therapist training

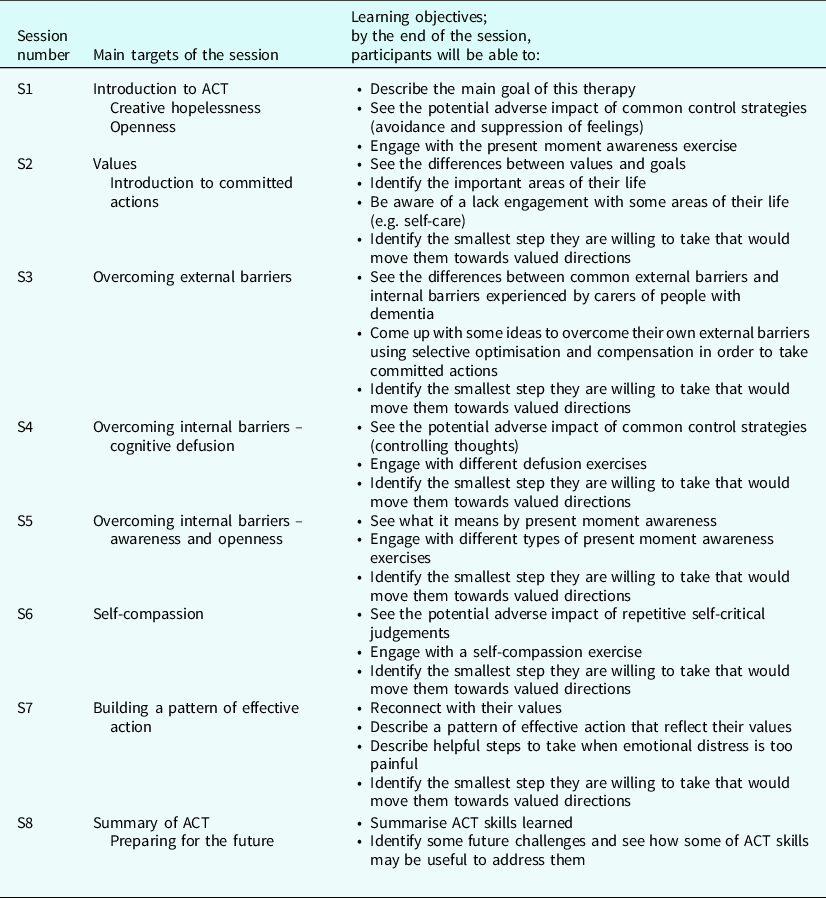

iACT4CARERS consisted of eight online sessions. Family carers were encouraged to complete all sessions within 12 weeks and were informed that access to the intervention would cease after this period. Table 2 provides a summary of the intervention, including key learning objectives of each session. A full description of each session is documented in detail in the main feasibility study paper, which reports all the quantitative feasibility and acceptability findings, means and SD values of outcome measures, and treatment fidelity results (Kishita et al., Reference Kishita, Gould, Farquhar, Contreras, Van Hout, Losada, Cabrera, Hornberger, Richmond and McCracken2021). At the end of each online session, family carers were asked to reflect on their self-learning and leave comments for their therapists online. The role of therapists was to provide written feedback for each session completed to support carers’ self-learning and encourage them to continue completing the sessions.

Table 2. A summary of iACT4CARERS – key learning objectives of each session

ACT, acceptance and commitment therapy; iACT4CARERS, internet-delivered guided self-help ACT for family carers of people with dementia.

Along with the online programme, family carers were given the option to attend three peer support groups, which were delivered via Microsoft Teams video call. The purpose of these groups was for family carers to connect with peers taking part in the intervention and encourage each other in completing the online programme. The therapist facilitated group peer support sessions, but these had no specific, planned, therapeutic elements, and were participant-led. Two of eight therapists were involved in facilitating the peer support groups during the trial.

Therapists attended a two-day online training (7 hours in total) led by the Chief Investigator via Microsoft Teams video call at the beginning of the trial. The training was related to both the intervention and the study delivery, covering the following topics: key ACT principles and therapeutic stance, contents of each online session, practical training on generating feedback using example cases, guidance on peer support groups delivery, how to navigate the online system, study procedure for therapists and Serious Adverse Event (SAE) reporting. Therapists were also given access to all video- and audio-recorded ACT metaphors and exercises embedded in the online programme during the trial. Initial training was followed by drop-in group supervision sessions led by the Chief Investigator, which took place on different days and times each week. Therapists had the opportunity to attend whenever it was convenient for them but were encouraged to attend at least one group supervision session each month.

Data collection

Recruitment of family carers for the iACT4CARERS feasibility trial took place between August 2020 and January 2021 and the trial was completed in April 2021. An initial invitation was sent by email to all nine novice therapists; one declined to participate with no reason given. After obtaining informed consent electronically, therapists were invited to attend a semi-structured individual interview via Microsoft Teams video call. All interviews were conducted by the same investigator (EVH) to ensure the consistency and reliability of the data collected. Using a semi-structured interview guide developed for the current study (see Supplementary material), the participants were asked to reflect on: (i) relevance and perceived benefits of iACT4CARERS to the targeted population; (ii) acceptability of the online system; (iii) feasibility and burden associated with the time and effort required (e.g. attending the training, providing feedback to the participants); (iv) satisfaction with the training and supervision received; and (v) potential adaptations to improve therapists’ experience in delivering the intervention. Interviews lasted no more than 45 minutes and were audio-recorded with the participants’ permission.

Data processing and analysis

The audio-recorded interviews were transcribed and analysed following Braun and Clarke’s six-stage thematic analysis approach (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). The thematic analysis was used in this study as the aim was to generate findings from the bottom up and identify themes and patterns of meaning across a dataset in relation to a research question (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2013). To ensure the validity and reliability of data analysis, the first coder (MC) and the second coder (NK) separately reviewed the first four transcripts to familiarise themselves with the data and start generating initial codes. They then met to compare these initial codes to achieve consensus.

Following this, all transcripts were imported into NVivo 12 and MC used the agreed set of codes to code all the transcripts consistently, generating additional codes as required. Once all the transcripts were coded, MC identified potential themes and sub-themes that were discussed with NK and EVH, and refined accordingly. The refined themes and sub-themes were discussed with three novice therapists who took part in the interview and were willing to review the initial findings to assess whether their experiences were adequately represented and to incorporate their views into the analysis. Final discussions and consensus between MC, NK and EVH finalised the definition of over-arching themes and sub-themes and visual mapping of themes.

Results

Eight participants were interviewed between February and March 2021. The characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. Four over-arching themes of the therapists’ experiences of being an online therapist for iACT4CARERS were identified: (1) Positive attitudes towards the intervention, (2) Therapists’ workload, (3) Therapists’ confidence to perform their role, and (4) Connecting with family carers in a virtual context. An overview of the over-arching themes and their sub-themes is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Overview of over-arching themes and sub-themes.

Positive attitudes towards the intervention

Opportunities for personal growth

The therapists involved in the study expressed positive attitudes towards the intervention. Concerning their role in the intervention, the therapists manifested that being a therapist was something they valued for various reasons. There was clear evidence that the learning and development opportunities were perceived as positive. More specifically, the therapists appreciated learning about ACT theory and developing new clinical skills, while also learning to work with family carers of people with dementia. Therapists also expressed that it was rewarding to know that they were helping other people, and that the whole experience was enjoyable for them:

‘I really enjoyed the training and learning a bit more about ACT, it’s not something I was very familiar with. So, from my perspective, I definitely viewed it as a good learning development opportunity. Yes, as going through and providing feedback, yes, I guess it gave me a different insight into how carers, like I work in dementia, so I work with first and foremost the person with dementia in that, sort of, process and seeing it from the carer’s point of view was really interesting as well.’ (Therapist 7)

‘[…] when I was hearing some positive feedback about the overall project, I would say, that yes that was definitely very rewarding to help them [family carers] in this journey, through these eight sessions but yes just to be part of such an important project. Yes, I really enjoyed it.’ (Therapist 6)

Perceived benefits to the family carers

Other aspects that contributed to the therapists’ positive attitudes towards the intervention were related to the impact that the intervention had on the family carers. Firstly, the therapists manifested positive feelings about the fact that the intervention was targeting family carers of people with dementia. The therapists felt that this type of intervention was critical as it can improve access to support before crisis point among family carers. The therapists could notice positive changes, including managing internal struggles effectively and increased value-based activities, in the carers over time during the intervention, which was mainly reflected in the online comments that the carers had left for their therapist at the end of each session. This perception that the carers were benefiting from the intervention led to increased positive feelings in the therapists:

‘I have supported lots of people that have had caring responsibilities and there is often thoughts and feelings of guilt, feeling overwhelmed and lots going on and, I guess, nobody ever teaches us how to manage our emotions better until things get really bad. So, I think this programme was useful because it, you know people weren’t in crisis when they were doing this. There is a potential for things to get worse and it’s a way of, I guess, helping them manage and keeping well before it gets to that stage.’ (Therapist 4)

‘She [family carer] was struggling with quite a few things, but she felt, for a lack of a better word, just kind of burnt out, and a lot of people around her were, I guess, drawing things from her, drawing energy, and really requiring her to be there all the time. That was very apparent at the start of the programme, but I think as the time went on and she went through the programme and learnt actually it’s so important to care for herself, as well as caring for others.’ (Therapist 2)

‘[…] given the quality of her [family carer] answers and the reflections, I did feel like something started to make sense specifically the values […] With her specifically, I remember actually feeling very excited that she reflected on these things so yes, I do think she may have benefited.’ (Therapist 1)

Therapists’ workload

Workload and user-friendly online platform being acceptable

The therapists expressed that there were several aspects of the intervention that made their workload manageable and compatible with other work commitments. The therapists perceived the time and effort required to attend the training and to provide feedback to the carers taking part in the intervention less demanding than expected and manifested positive feelings about their involvement. The therapists also found the online platform in which the intervention was delivered easy to access and to navigate, and this helped to make their tasks more manageable.

‘I thought that was absolutely fine, yeah. I guess kind of it was good in the fact that actually kind of taking out that two days to be trained properly.’ (Therapist 3)

‘I didn’t think that [providing feedback to carers] took a lot of time either. I think it took me about, sort of, 15 to 20 minutes, you know, maximum, to really think about what I was giving.’ (Therapist 8)

‘I think it was really easy to just log in, an email come through straight away to say that someone’s left a reflection. I’d log in, check to see what it briefly looked like. If I had the time to respond to it there and then, then great, if not I could plan the time to sit down and actually deeply look at the reflection and have a bit more time for it. But yes, it’s really simple, really easy to use.’ (Therapist 5)

Time-consuming cases increased therapists’ burden

Despite the positive aspects reported, some therapists also faced some challenges regarding their workload. Some therapists who were working with ongoing carers simultaneously felt that having to provide feedback to multiple carers at the same time was time-consuming and therefore increased their burden, particularly when the carers left long reflective comments that required more attention. In these cases, the therapists struggled to achieve the recommended timeframe to provide feedback (i.e. within 72 hours from receiving the carer’s reflective comments). Some therapists struggled to remember the content of each online session after the initial two-day training. The therapists then needed to go through the training materials to make sure that they were providing tailored feedback to each carer in line with the content of the relevant session and felt that this additional work was time-consuming. To reduce their burden and optimise their time, some therapists suggested having an aide-memoire to remind them of the main content of the relevant session embedded within the online platform.

‘It started with only one person and it felt very manageable and very easy to do […] and I suddenly had three people to feedback about and a couple of the people I was giving feedback to were writing very long comments and I would spend a lot of time thinking about what the right thing is to write and how to address it all. And I guess on that note, what started to happen because I was finding it hard to keep up, I would reply to all of the comments at the same time or on the same day and so they started also completing it on the same day which meant that I then the next time had to complete them all within the same day. Yes, so that’s something I noticed and found a bit difficult.’ (Therapist 7)

‘The other thing that I quite struggled with was probably that quite often when people left detailed feedback they would leave feedback of kind of certain aspects of the session and as I hadn’t gone through all of the sessions, I’d had the training obviously, but sometimes kind of certain aspects I wasn’t familiar with, what they were actually talking about. So, that actually made it quite difficult to respond to and quite time consuming because sometimes I would go back through the training slides to try and find the section that they’re talking about.’ (Therapist 3)

‘So, the only thing I wished that was maybe there was, like, a little reference, you know, to the … to the therapist, or whoever, just, like, as a little prompt of what session the client had just completed. […] just maybe having the contents of whatever session was just completely available to the therapist just so that it’s easier for us to see what they’ve just completed or what session they’ve just completed rather than, sort of, having to go back and, I guess, dig through.’ (Therapist 8)

Therapists’ confidence to perform their role

Practical resources led to immediate confidence after the training

Most of the therapists felt that the initial two-day training helped them to increase their confidence in working as therapists. Examples of ACT-consistent feedback was most appreciated by the therapists among other training materials provided. The therapists expressed that the practical aspect, practising drafting written feedback for carers using case examples during the training and discussing them in a group, particularly improved their confidence. However, some competing feelings were identified. Some therapists felt that they did not feel fully competent immediately after the training as a result of the limited duration of training provided (i.e. two days).

‘Yes, I think that, again, for some participants, I felt quite confident because of the training, because it was something that we already have seen on the examples, that [Project Chief Investigator] showed to us, so yes I felt very confident with some of them.’ (Therapist 6)

‘However, [Project Chief Investigator] provided a Word document which had some of the ideas that we had during the training, so some ACT consistent feedback that we discussed. So, I referred back to that if I was ever stuck and then again if I was unsure as to how to give feedback or what to give.’ (Therapist 2)

‘Having that chance to practise the feedback, I think was one of the most beneficial parts of the training. Although you had the knowledge, if we went away and didn’t do the practice run, I think I’d have felt a bit overwhelmed when I started getting some reflections come in, so having that chance to discuss it and see how the other therapists would have responded and how [Project Chief Investigator] would respond, it really helped to give a bit more confidence.’ (Therapist 5)

‘I think there was some aspect of the training that left me, “oh that’s it, we’re going straight… we’re doing it now, isn’t there another training?” […] after the training, no, I did not feel competent. I don’t know why, let me think… no, I just felt unequipped.’ (Therapist 1)

Continued practice and supervision boosted confidence over time

There was clear evidence that all the therapists were able to boost their confidence after the initial training and feel more competent in their role as a result of getting more practice in providing feedback to the carers over time. All the therapists acknowledged that the supervision instances helped improve their confidence and valued the various opportunities they were offered to reach out for support when needed. The drop-in supervision sessions in a group format were particularly appreciated as they allowed the therapists to learn from other therapists’ experiences and challenges while having opportunities to receive support by email from a supervisor (Chief Investigator) when they were not available to attend scheduled drop-in sessions.

‘Yes, by the end I felt like I could write something that was really ACT consistent. Whereas to start off with I was, yes, double-checking of there is this statement, what would be the right thing, but I think that’s me as well just making sure I’m getting things right rather than putting something that’s incorrect.’ (Therapist 4)

‘I think it got easier over time and maybe with a bit of practice of actually replying to people. Yes, maybe I didn’t feel very confident to begin with, but the tools were there to help me, I guess.’ (Therapist 7)

‘I think it was really good and also the fact that we had so many options to attend the supervision meetings and on different days and different times. I think that was really good because you kind of feel supported […] if you are struggling with some participants it’s good that you have that instance where you can talk to someone else and ask their opinion and so yes. I think that having that was really helpful.’ (Therapist 6)

‘it was also helpful to listen other people’s experiences. So there were a few cases where I didn’t really have anything to bring to the supervision, I had given feedback and it felt very straightforward, but I still went because it was interesting to hear about other people, their struggles or whether they’d come across anything which might then be helpful for me in the future. So yes, I found it really helpful. It was nice just to connect with the other therapists.’ (Therapist 2)

Connecting with family carers in a virtual context

Perceived challenges in the therapist-carer interaction

There was overwhelming evidence in the interviews suggesting that the therapists were particularly interested in building a good therapeutic relationship with the carers, which was challenging in the virtual context. One of the common challenges that the therapists encountered was feeling that their feedback was repetitive and non-personalised. This challenge was more apparent when lengthy and wide-ranging comments were provided by the carers. The therapists struggled to respond to the complex situations shared by the carers without a good therapeutic relationship. Receiving a brief comment from the carers (e.g. ‘everything was clear and helpful’) was equally perceived as challenging as therapists found it difficult to provide tailored feedback in such cases given their limited knowledge about their assigned carers.

‘I think kind of the two things that I struggled the most with was first of all kind of not knowing the participants and not having like any chance to kind of have a video call with them or anything like that. So, they don’t know my face and I don’t know theirs. Also, kind of not knowing kind of the context around their difficulties. Which meant quite a lot that I felt that the feedback was quite … almost robotic and non-personal. I did wonder if that kind of would hinder their engagement with me.’ (Therapist 3)

‘I would say that, yes one of the challenges is when they give you, like a very, very short comment, like, “Everything was helpful”. Something like that. It’s hard to know what to answer […] I felt that I wasn’t being that helpful because she or he, that participant wouldn’t give me too much to work with. So yes, I found that challenging. […] So I think that was the most challenging, having those participants, that wouldn’t say that much, or the opposite, having those participants that would share more complex situations.’ (Therapist 6)

Ways to improve the therapist–carer interaction

The therapists highlighted some key aspects of the intervention to be improved in the future, which were mainly related to ways to improve the therapist–carer interaction. The therapists suggested including some face-to-face interaction (e.g. video call) with each assigned carer as this additional component could enhance the therapeutic relationship. Some therapists highlighted that it is critical to explain the importance of the reflective part of the intervention to the carers so that they could make the most of their interaction with the therapists. In this regard, the therapists suggested using more focused questions in the reflection section (e.g. What might you do differently after this session?) to facilitate the interaction. Finally, some therapists felt that they did not know if the carers were finding feedback from them helpful. The therapists expressed that they wished they had bi-directional interaction, such as receiving a rating on their feedback from the carers.

‘Yes, I guess, it’s just making things feel a bit personal and thinking about how you get a human connection over something which is very text-based, isn’t it? So, whether or not it’s like that or the therapist could even do an introduction video going, “Hi”, you know, doing it that way as well so people knew the person behind the text […] Yes, because I think, as well, it’s the participants. There is some stranger reading some of their thoughts so to maybe feel a little bit more comfortable and have a bit of rapport with somebody, they might feel more comfortable in writing more text.’ (Therapist 4)

‘Well perhaps even like having the conversation of how important the feedback is and the reflection is and how that’s where we can quite learn about the information we’ve taken in and a bit of education around that bit would be good. Because yeah like I said I don’t always feel like the participants really acknowledged the importance of that part of it. I think they thought the session was over and then just fill in a little questionnaire and then they’re done […] Whereas actually that’s probably one of the most important parts of the session.’ (Therapist 3)

‘[…] other lines of questioning might elicit different responses because it’s alright saying, “Okay, well what did you find useful?” But, I guess, asking people, “What are you going to take forward from this session? What are you going to implement after this session? What might you do differently after that session?” Then you’re going to get an idea of how people are going to apply the learning into their lives as well, rather than just going, “Yes, it’s useful”. […] So, I guess, within the reflections there could be, I guess, further questions to get people thinking about how to apply it more.’ (Therapist 4)

‘There is not that two-way thing that you would have if you were a real therapist and having that conversation. So, yes, it just felt a bit strange really because then you’re, kind of, like, “Well, are they finding this useful that I’m doing? Do they even read it? Are they bothered?”. […] even if it were just that one question, I mean how useful did you find this feedback one to five or something like that […] Or even if they could respond and go, “Yes, thanks for that”. […] Like it’s a conversation but, I guess, it didn’t always feel like a conversation.’ (Therapist 4)

Discussion

This study aimed to understand therapists’ perceptions and acceptability of delivering internet-delivered guided self-help ACT for family carers of people with dementia (iACT4CARERS). Four over-arching themes were identified in the semi-structured interviews with novice therapists: positive attitudes towards the intervention, therapists’ workload, therapists’ confidence to perform their role and connecting with the family carers in the virtual context.

The findings demonstrated that the positive attitudes towards the interventions, such as therapists seeing their involvement as opportunities for personal growth and perceiving benefits of the intervention to the carers contributed to higher acceptability among the therapists. A previous study conducted with assistant psychologists from the UK and Ireland found that the most frequent reported reason for job satisfaction was career-oriented gains. This includes experiences that enhance the curriculum vitae and potentially improve their chances of gaining entry to clinical psychology training programmes (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Campbell and Byrne2015). For this reason, therapists’ perceptions of their involvement as a learning and development opportunity seems critical for improving acceptability of the intervention to them.

Furthermore, the findings highlighted that the time and effort required to attend the training and to provide feedback to the carers was adequate and the user-friendliness of the online platform helped to make their workload more manageable and feasible among the therapists. Previous studies demonstrated that increased workload and perceived time pressure are the most significant job demands contributing to burn-out among therapists (McCormack et al., Reference McCormack, MacIntyre, O’Shea, Herring and Campbell2018). As this feasibility study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, these aspects were particularly important given that the pandemic has created additional workload and an increase in associated pressures among healthcare professionals (Pappa et al., Reference Pappa, Barnett, Berges and Sakkas2021; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Song, Liu, Mao, Sun and Cao2020).

Practical resources provided during the training, such as examples of ACT-consistent feedback, practice in drafting written feedback using the case examples, and continued opportunities for practice and supervision, also increased confidence and facilitated greater acceptability among the therapists. These findings support the wider findings, which suggested that getting more experience in delivering the intervention over time was key to developing mastery of the therapeutic approaches and increased confidence (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Huws, Appleton, Cooper, Dagnan, Hastings, Hatton, Jones, Melville, Scott, Williams and Jahoda2021). It has been previously reported that those trial therapists who felt satisfied with training and supervision received were more likely to participate in the delivery of a similar type of intervention in the future (Rodda et al., Reference Rodda, Merkouris, Lavis, Smith, Lubman, Austin, Harvey, Battersby and Dowling2019).

Overall, the delivery of iACT4CARERS was perceived as positive and acceptable among the therapists. However, several aspects critical for facilitating the acceptability were also identified. One of the key areas for improvement highlighted was the difficulty in building a good therapeutic relationship with the family carers in the virtual context. These feelings have been reported in other studies conducted with therapists delivering psychological interventions virtually, such as cognitive and behaviour therapy (Bengtsson et al., Reference Bengtsson, Nordin and Carlbring2015; Donovan et al., Reference Donovan, Poole, Boyes, Redgate and March2015; Meisel et al., Reference Meisel, Drury and Perera-Delcourt2018; Thew, Reference Thew2020). Although the therapeutic relationship is considered to be an important factor across all psychotherapies, research into this topic is limited in the context of online therapy (Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Paxling, Wiwe, Vernmark, Felix, Lundborg, Furmark, Cuijpers and Carlbring2012; Geller, Reference Geller2020).

There is some preliminary evidence suggesting that clients report strong therapeutic relationships with their therapists in virtual modalities that are similar to those reported for face-to-face interventions (Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Paxling, Wiwe, Vernmark, Felix, Lundborg, Furmark, Cuijpers and Carlbring2012; Sucala et al., Reference Sucala, Schnur, Constantino, Miller, Brackman and Montgomery2012; Thew, Reference Thew2020; Wehmann et al., Reference Wehmann, Köhnen, Härter and Liebherz2020). Despite the existing evidence, therapists frequently hold negative beliefs regarding the possibility of building strong therapeutic relationships with patients in a virtual context, and negative expectations of the impact of virtuality on therapeutic outcomes (Rees and Stone, Reference Rees and Stone2005; Thew, Reference Thew2020). In the current study, the therapists highlighted the need for some (still virtual) face-to-face interactions (e.g. video calls) with their assigned carers and bi-directional interactions between carers and therapists in order to build a stronger therapeutic relationship with the carers. Although this seems an important aspect to consider, tackling common negative expectations among therapists seems equally important, particularly when the intervention involves novice therapists (Rees and Stone, Reference Rees and Stone2005).

Another key area for improvement identified was the difficulties in working with the family carers when they had provided lengthy and wide-ranging comments sharing complex issues or when, at the other extreme, they provided only a brief comment not necessarily requiring a response. These challenging cases led to increased workload and burden, making it difficult for therapists to manage competing demands, and thus resulting in decreased acceptability. The latter issue regarding brief comments also became a challenge for the supervisor during drop-in group supervision sessions, particularly when family carers only provided limited comments across all eight sessions. The supervisor felt that therapists’ inclination to elaborate responses to achieve a better sense of connection with family carers was not achieved in these cases.

To date, there is no clear guidance on how therapists delivering any type of online interventions should be trained, thus further research assessing different methods of training online therapists is needed (Thew, Reference Thew2020). However, there are some recommendations based on expert consensus such as ensuring that therapists have a clear knowledge and understanding of the treatment protocol, their role as therapists and what content should be covered in the feedback they provide, and to learn and practise strategies to deal with common problems that may arise with the patients (Thew, Reference Thew2020). ACT also recommends promoting psychological flexibility not only in patients but also in therapists during supervision as this can promote the therapists’ capacity to actively embrace their private experiences (e.g. negative expectations) in the present moment and engage or disengage in patterns of behaviour in the service of chosen values (e.g. supporting patients) (Morris and Bilich-Eric, Reference Morris and Bilich-Eric2017).

Furthermore, previous studies of therapists’ perceptions and acceptability of internet-delivered interventions demonstrated that the most common beliefs and concerns that therapists have about this delivery format are: their lack of knowledge about the current evidence base for this modality of delivering interventions, worries about if it will be as effective as face-to-face therapy, the suitability of this type of intervention for people with more severe problems, and worries about failing to meet service users’ expectations of therapy (Bengtsson et al., Reference Bengtsson, Nordin and Carlbring2015; Donovan et al., Reference Donovan, Poole, Boyes, Redgate and March2015; Meisel et al., Reference Meisel, Drury and Perera-Delcourt2018; Rees and Stone, Reference Rees and Stone2005; Thew, Reference Thew2020). Unfortunately, these common concerns were not well addressed in our training package. It is recommended that a training package for therapists in a future iACT4CARERS trial includes a discussion about the current evidence on the online mode of delivery in general, expectations for online therapists, strategies to manage common challenging cases and supervision which can promote greater psychological flexibility among therapists.

One major limitation of this study that must be acknowledged is the sample size. Due to the scale of the main feasibility study, only nine therapists were involved in the delivery of iACT4CARERS. Although nearly all of the therapists took part in this qualitative study, eight is still a small number of participants. We invited the therapists back during the data analysis phase to ensure that their experiences were adequately represented, but we cannot assert that the sample held sufficient information power (Malterud et al., Reference Malterud, Siersma and Guassora2016). Moreover, only two male therapists took part in the interviews, and therefore their views might be under-represented. As we did not collect other demographic data on therapists (e.g. age), the extent to which the findings can be applied to a broader therapist population is unclear. Another limitation is that following the establishment of initial codes through mutual agreement, the subsequent coding process was completed by a single coder. We also did not pilot the interview guide prior to the start of this study, and how the interview was structured may have biased the qualitative information obtained.

Conclusion

This qualitative study identified that perceiving the role as an opportunity for personal growth, perceiving benefits to the family carers, feeling satisfied with the workload and the user-friendliness of the online platform, and feeling confident in performing the role following the training and continued supervision, led to greater acceptability of the intervention delivery among the therapists. However, difficulties in building a good therapeutic relationship in the virtual context and dealing with time-consuming cases leading to increased workload were perceived as challenges. It is recommended that the contents of the training for online therapists for a future iACT4CARERS trial include the information about current evidence on the online mode of delivery in general, clearer expectations for online therapists, practical strategies to deal with common problems and supervision which can promote greater psychological flexibility among therapists. It is important to explore if these improvements could lead to an improved therapeutic relationship and increased acceptability of the intervention to therapists in a future trial.

Key practice points

-

(1) It appears that novice therapists who do not hold a formal qualification in clinical psychology, and with limited previous experience in acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), may be able to administer internet-delivered guided self-help ACT after attending a brief training workshop (7 hours).

-

(2) Learning opportunities for personal growth, user-friendliness of the online platform, and satisfaction with the training and supervision received, appear critical for the successful engagement of such therapists within the services.

-

(3) Developing guidance further so that the therapeutic relationship in the virtual context is enhanced and helping online therapists to embrace their own negative expectations are likely to be critical to boosting therapists’ performance.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank patient and public involvement research partners, Ruby Ali-Strayton, Geoff Angel and Peter Davis, for their invaluable insights at every stage of the design and conduct of the research. The authors also would like to thank Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust, Hertfordshire Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust and Octagon Medical Practice for their enormous support even throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. The huge contribution of research staff and principal investigators is duly acknowledged: Amanda Wheeler, Dr James Miller, Dr Aditya Nautiyal and Dr Shaheen Shora. Thank you also to the trial therapists involved with the delivery of the interventions and to the clinical managers who supported staff engagement with the study.

Financial support

This project is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Research for Patient Benefit (RfPB) Programme (grant reference number PB-PG-0418-20001). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical statements

Full ethical approval was obtained from the NHS London-Queen Square Research Ethics Committee (20/LO/0025). This study has been performed in accordance with the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data availability statement

The is a qualitative interview study, and thus the data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Author contributions

Milena Contreras: Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Writing-original draft (lead), Writing-review & editing (lead); Elien Van Hout: Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Writing-original draft (supporting), Writing-review & editing (supporting); Morag Farquhar: Conceptualization (supporting), Funding acquisition (supporting), Writing-original draft (supporting), Writing-review & editing (supporting); Rebecca L. Gould: Conceptualization (supporting), Funding acquisition (supporting), Writing-original draft (supporting), Writing-review & editing (supporting); Lance M. McCracken: Conceptualization (supporting), Funding acquisition (supporting), Writing-original draft (supporting), Writing-review & editing (supporting); Michael Hornberger: Funding acquisition (supporting), Project administration (supporting); Erica Richmond: Data curation (supporting), Funding acquisition (supporting); Naoko Kishita: Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (supporting), Formal analysis (supporting), Funding acquisition (lead), Project administration (lead), Resources (lead), Supervision (lead), Writing-original draft (equal), Writing-review & editing (equal).

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X21000337

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.