Introduction

Early intervention in psychosis (EIP) services provide care and treatment for people experiencing first episode psychosis (FEP) and more recently those who are deemed at risk of developing psychosis (At Risk Mental State, ARMS) (NICE and NHSE, 2016). Healthcare professionals (HCPs) provide evidence-based care appropriate to the biopsychosocial needs of the individual whilst also supporting family and carers (NICE, 2014). A symptom led approach allows for treatment as early as possible before a diagnosis is made (McGorry et al., Reference McGorry, Killackey and Yung2008). Literature has indicated the value of Early Intervention Teams in: reducing chronicity amongst the population; increasing control and autonomy; and reducing associated long-term costs of mental health care provision (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2016).

Treatment guidelines (NICE, 2014) advocate the application of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for both FEP and ARMS service users due to its positive outcomes. It is also considered a less restrictive measure to implement with a younger population, who are widely represented within these services, compared with the traditional uses of psychotropic medication previously utilised with psychosis spectrum conditions (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Burke and Morrison2015). Despite the endorsement of CBT for both groups, in practice this can prove challenging particularly within the ARMS group where high levels of co-morbidity and complexity are displayed (Addington et al., Reference Addington, Cornblatt, Cadenhead, Cannon, McGlashan, Perkins and Woods2011a).

Within the qualitative literature, reviews of the application of CBT to people with psychosis outline the importance of the therapeutic alliance, facilitating change through interventions (assessment, formulation, normalisation, psychoeducation) and the challenges of applying CBT which are often associated with emotional difficulties, readiness to engage in the process, difficulties with self-concept and motivation issues (Berry and Hayward, Reference Berry and Hayward2011; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Burke and Morrison2015).

Comparatively little is known about the lived experience of engaging in CBT within the setting of early intervention services, particularly in the field of ARMS. Most of the research into CBT within EIP groups has focused on empirical data, i.e. keen focus given to CBT effects on transition to psychosis and symptom severity across the ARMS group (Hutton and Taylor, Reference Hutton and Taylor2014; Stafford et al., Reference Stafford, Jackson, Mayo-Wilson, Morrison and Kendall2013). Findings indicate reduced subthreshold symptoms for ARMS users at some points (12 months) but not others (6, 18 and 24 months, respectively) (Hutton and Taylor, Reference Hutton and Taylor2014), and moderate effects on reducing transition (Stafford et al., Reference Stafford, Jackson, Mayo-Wilson, Morrison and Kendall2013). Similarly, within FEP groups data has given focus to effects on positive symptoms and psychopathology, indicating superiority to treatment as usual (Mehl et al., Reference Mehl, Werner and Lincoln2015). These findings, although important, do not indicate the broader experiences of receiving CBT from users’ perspectives, and fail to capture effects beyond symptom reduction.

Previous quantitative CBT ARMS studies, although based on the same treatment approach (French and Morrison, Reference French and Morrison2004), utilised different variables, i.e. number of sessions offered (Addington et al., Reference Addington, Epstein, Liu, French, Boydell and Zipursky2011b; Morrison et al., Reference Morrison, French, Stewart, Birchwood, Fowler, Gumley and Murray2012) or this being enriched with adjunct exercises and specific psychoeducational materials (van der Gaag et al., Reference van der Gaag, Nieman, Rietdijk, Dragt, Ising, Klaassen and Linszen2012), which makes generalisations difficult. A systematic review and meta-analysis of CBT for psychosis prevention (Hutton and Taylor, Reference Hutton and Taylor2014) found the risk of developing psychosis was reduced by more than 50% for those receiving CBT at 6, 12, 18 and 24 months; however, no effects on functioning, symptom-related distress or quality of life were observed, which are important factors to consider from users’ perspectives.

CBT is one form of support offered by EIP teams and is a mainstay of treatment. However, it is unclear which aspects of EIP input are helpful from a subjective perspective, therefore we are also interested in the experiences of broader support provided to both FEP and ARMS populations and whether services meet their psychological needs. It is also important to understand service users’ experiences as therapeutic change (i.e. reduction in symptoms, improvements in quality of life), and preferences concerning treatment and support may differ across groups.

The aims of the review were to:

-

(1) Explore the views of EIP service users on support received within early intervention, to establish valued components.

-

(2) Explore user experiences of CBT within EIP.

-

(3) Establish practice points for consideration and possible areas for future research to enhance user experiences of EIP support.

Method

Refining the research question

Initially a summative approach was adopted whereby the research question was established a priori, and the focus of the review was planned to explore perspectives of the ARMS population on their experiences of CBT. Progressive evaluation indicated a paucity of relevant qualitative literature (Bettany-Saltikov, Reference Bettany-Saltikov2012). Therefore a broader research focus was adopted and the research question was re-defined to incorporate both FEP and ARMS users, as both are supported through the majority of EIP services in the UK (NICE, 2014), and to incorporate broader support (inclusive of CBT provision). The review was undertaken to illuminate key aspects of support across both groups to enhance intervention delivery, as it was deemed important that qualitative findings were synthesised to develop a deeper understanding of the needs of the early intervention population.

Design

A systematic review of qualitative literature was conducted using thematic synthesis (Thomas and Harden, Reference Thomas and Harden2008). It aimed to bring together findings to make connections between existing studies and compare main concepts with the purpose of re-interpreting findings and generating new insights (Dixon-Woods et al., Reference Dixon-Woods, Cavers, Agarwal, Annandale, Arthur, Harvey and Smith2006; Major and Savin-Baden, Reference Major and Savin-Baden2010).

Search strategy

Patient exposure outcome (PEO) delineated key search components (Hewitt-Taylor, Reference Hewitt-Taylor2017). Database thesaurus of AMED, MEDLINE and PsycInfo were consulted to identify both Medical Subject Headings and keyword terms (Moule et al., Reference Moule, Aveyard and Goodman2016), which were subsequently grouped into three key concepts to locate relevant literature (Polit and Beck, Reference Polit and Beck2009). NHS Evidence, grey literature searches and regular online searches for policy pertaining to early intervention were also conducted. Forwards and backwards citation tracking was performed on all full-text screened articles (Aromataris and Riitano, Reference Aromataris and Riitano2014). Due to time delays in developing this review for publication, the original search strategy was repeated in October 2019. This identified two additional relevant papers for inclusion (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012; Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria:

-

Population: Service users receiving treatment from EIP services, ARMS or FEP, aged between 14 and 35 years (in line with national EIP guidelines).

-

Exposure: Being provided with care and/or CBT from EIP services.

-

Outcomes: (i) Lived experiences of ARMS/FEP in relation to provision of care from EIP services; (ii) views and beliefs regarding CBT: preferences, valued tenets of therapy.

-

Eligible study designs included: Qualitative studies; mixed method studies that reported some qualitative data relating to the outcomes of interest.

-

Articles were excluded if they were: purely quantitative; not concerned with service user views; not in English; not a journal article in a peer reviewed journal; non-EIP studies where the clinical population was not ARMS/FEP.

Data screening and selection

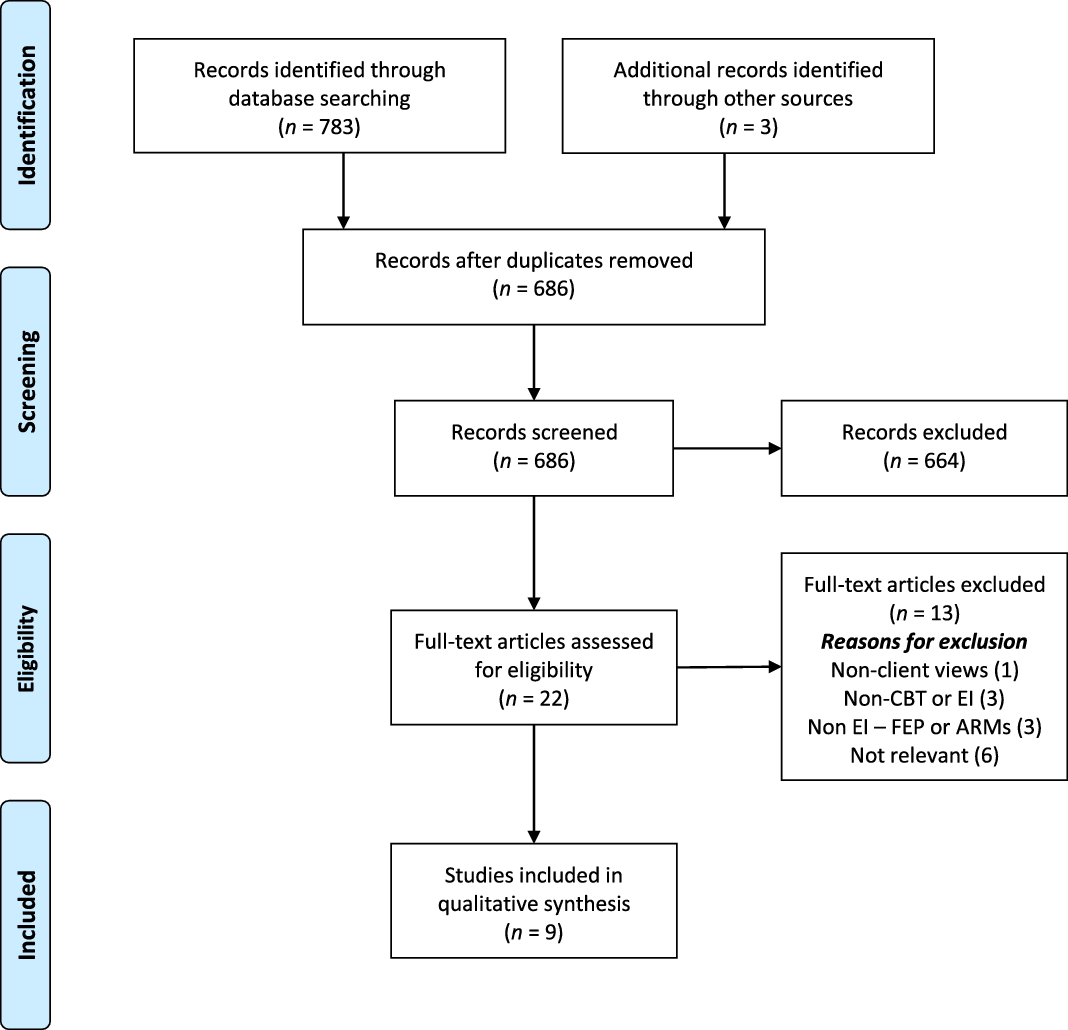

The process of selecting studies for inclusion consisted of sifting through titles and abstracts of all articles retrieved, screening systematically and selecting those that met the pre-determined inclusion criteria (Bettany-Saltikov, Reference Bettany-Saltikov2012). If neither the title nor abstract contained sufficient information to be judged as either relevant or irrelevant, the full text was accessed, and the same criteria used to make the final decision and duplicate studies were removed. After two rounds of screening, nine eligible studies were included. The selection process, including search results and reasons for exclusion at each stage of screening are represented in a PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA 2009 flow diagram.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data were extracted using a bespoke data extraction form to ensure consistency. Information extracted from primary studies included: bibliographic information; setting and location; population; research question(s) and aim(s); data collection methods; data analysis methods; and primary or secondary data relating to the outcomes of interest.

The quality of included studies was appraised using the Critical Skills Appraisal Programme (CASP, 2017) appraisal tool for qualitative studies, which includes assessments of rigour, credibility, relevance and appropriateness of methodology. Each item was assigned a score, with ‘3’ indicating yes, ‘2’ meaning can’t tell and ‘1’ not addressed. A modified approach using the ConQual method to grade synthesised findings on aggregate level of quality gave an overall ranking which was considered a rating of confidence (Munn et al., Reference Munn, Porritt, Lockwood, Aromataris and Pearson2014).

Credibility was further supported through second coder review of research themes and codes, and consensus was reached on the selection of illustrative quotes, which enhanced data quality (Finlay, Reference Finlay2006) and demonstrated congruency between author interpretation and supporting data (Munn et al., Reference Munn, Porritt, Lockwood, Aromataris and Pearson2014).

Dependability was supported through following PRISMA guidelines to report the review to ensure findings were consistent and could be repeated, which demonstrated congruity between methodology and aims, data collection, representation and analysis (Munn et al., Reference Munn, Porritt, Lockwood, Aromataris and Pearson2014).

The author engaged in critical reflection of how their position could influence the data as they are a clinician based in EIP services (McCabe and Holmes, Reference McCabe and Holmes2009). Potential bias was mitigated through the process of reformulation of the intended initial research aims to reflect the evidence base, and during data collection and analysis which required regular reflection on the review aims, use of supervision and peer review.

Data were analysed using thematic synthesis (Thomas and Harden, Reference Thomas and Harden2008) conducted in three stages, with the aim to generate themes regarding service users’ experiences of treatment and support through EIP. Codes identified as exemplifying similar constructs were merged into descriptive categories, and subsequent analytical themes.

It was originally planned to synthesise data according to the review’s aims regarding valued aspects of EIP support with a focus on CBT; however, few study findings addressed this wholly and directly. In order to avoid imposing an a priori framework without allowing for the possibility that a modified framework may be more appropriate, study findings themselves formed the basis of the analysis (Thomas and Harden, Reference Thomas and Harden2008).

Identified studies were coded line by line inductively to capture meaning, resulting in descriptive categories (Thomas and Harden, Reference Thomas and Harden2008), which reflected the findings of the primary studies. The use of line-by-line coding enabled translation of concepts from one study to another (Britten et al., Reference Britten, Campbell, Pope, Donovan, Morgan and Pill2002). Codes were reviewed across studies, similarities and differences were identified, and grouped into a hierarchical structure; new codes were created to capture meaning of groups of initial codes which were then collapsed into analytical themes.

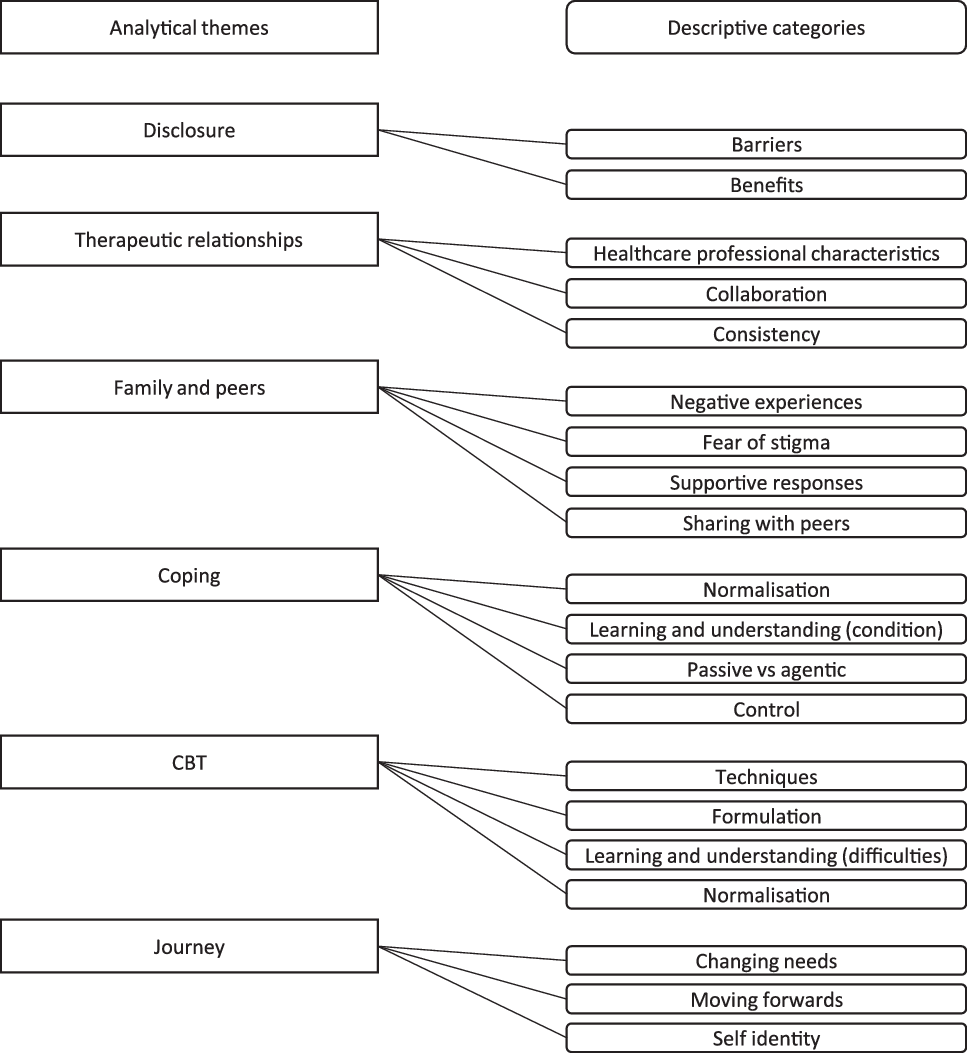

Further consideration led to removal of analytical themes that did not meet the review aims and the generation of additional descriptive categories (Britten et al., Reference Britten, Campbell, Pope, Donovan, Morgan and Pill2002). An iterative reflective process resulted in revisions to analytical themes until these were sufficient to inform descriptive categories. The resulting thematic structure organised a total of 20 descriptive categories into six analytical themes.

Results

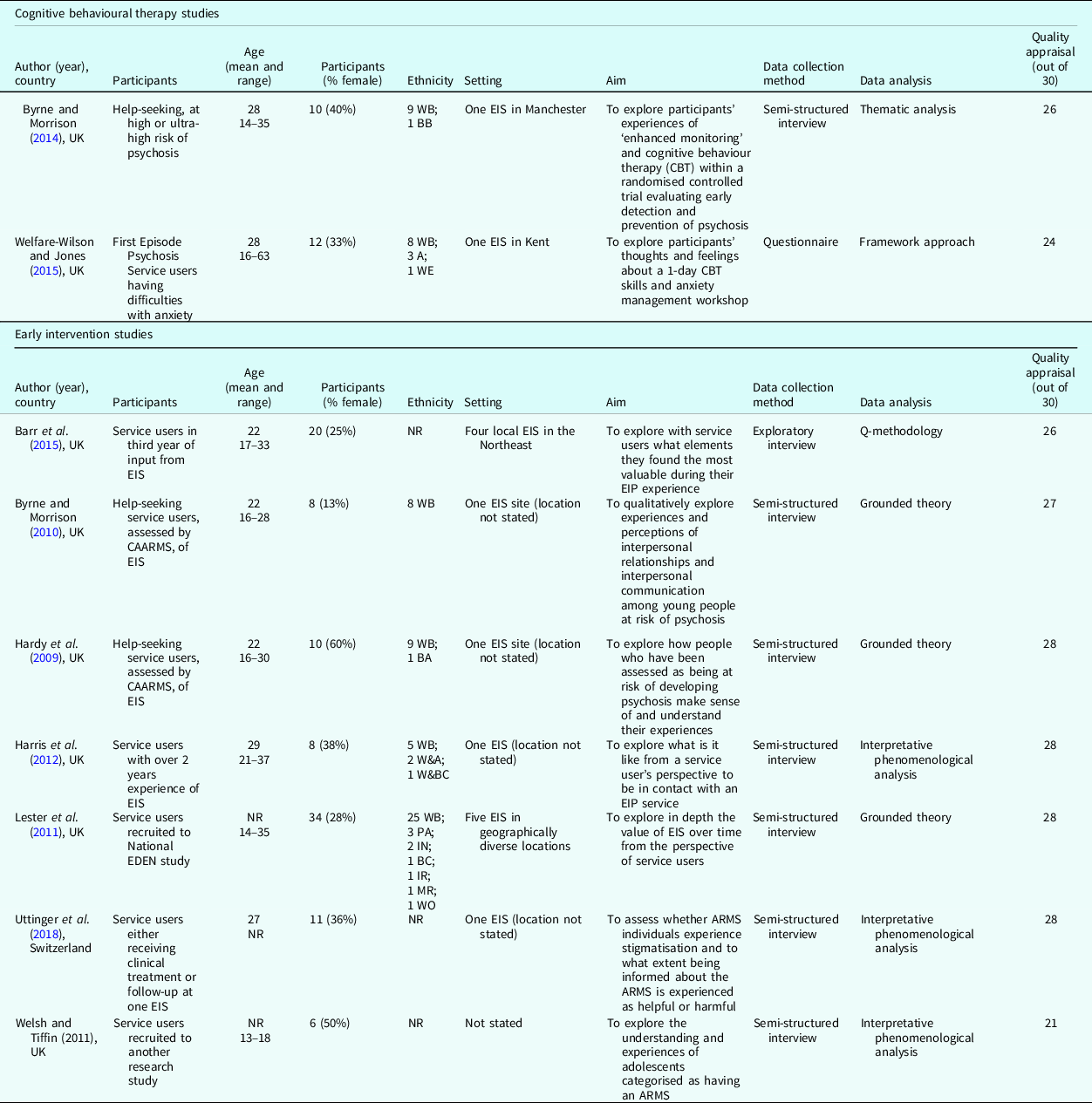

The PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1) illustrates the flow of studies through the synthesis. Table 1 summarises the characteristics of included studies.

Table 1. Summary of included studies

A, Asian; BA, Black African; BC, Black Caribbean; BB, Black British; IN, Indian; IR, Irish; MR, mixed race; PA, Pakistani; WB, White British; WE, White European; WO, White other; W&A, White and Asian; W&BC, White and Black Caribbean; NR, Not Recorded.

Although aspects of EIP support are documented in line with the over-arching aims of the review, much of the focus in studies was on factors that may be deemed non-intervention specific. However, these factors had an impact on EIP support experiences and are important when considering how attention to these may enhance service delivery and experiences. This will be expanded upon in the Discussion.

Themes identified

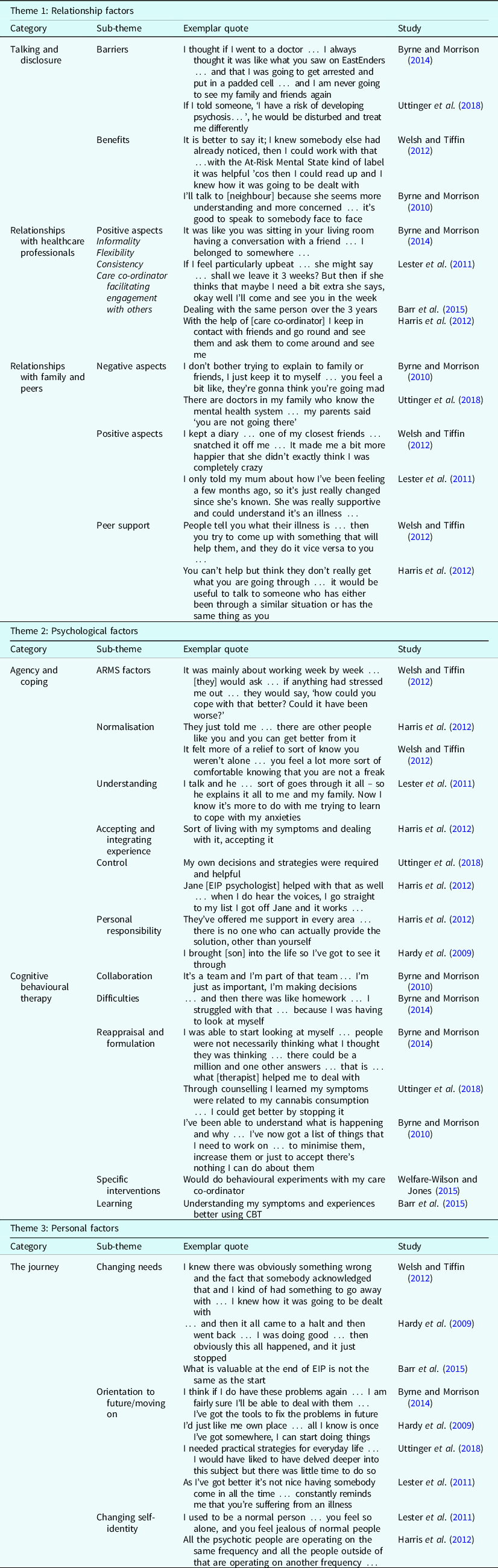

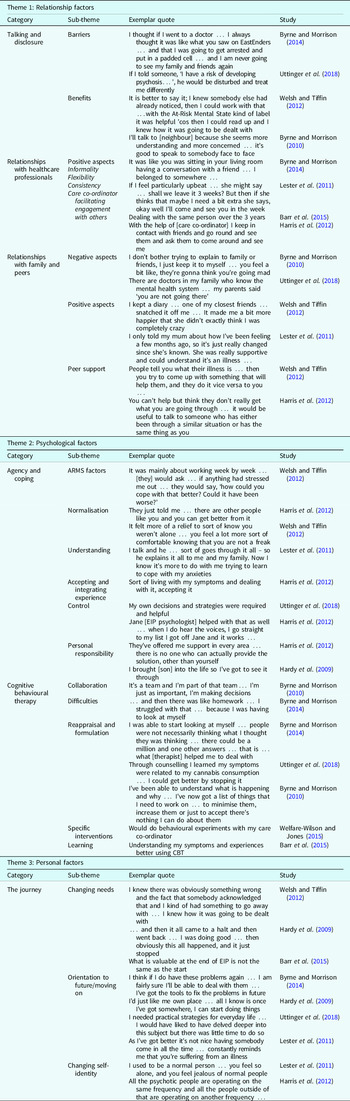

Analysis of the data revealed six analytical themes and 20 descriptive categories, which are summarised in Fig. 2. A narrative discussion of each theme is provided below, and exemplar quotes for each theme are given in Table 2.

Figure 2. Thematic analysis.

Disclosure

Disclosing first experiences was highlighted across studies as often difficult but important in facilitating support. Fear of judgement and negative responses often had an impact on both groups’ willingness to talk about their experiences, which could be a barrier to accessing services (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2010; Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2014; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012; Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018).

For the FEP group, perceived seriousness of the psychosis label served as a barrier; however, when this was overcome early contacts provided relief and optimism (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012). Similarly, ARMS users expressed a fear of ‘going mad’ which led to delayed help-seeking and disclosure due to fear of negative reactions or lack of relevant support (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2010; Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2014; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012; Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018). Many chose not to disclose the ARMS label or if they did, ‘watered down’ their experiences (Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018). Some ARMS users advised of a ‘breaking point’ due to intensification of experiences which meant they felt they needed to talk to someone (Hardy et al., Reference Hardy, Dickson and Morrison2009). After overcoming fear associated with not knowing what to expect (Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018), having a chance to talk was valued, providing relief (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2014; Welsh and Tiffin, Reference Welsh and Tiffin2012), realisation that help was forthcoming (Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018; Welsh and Tiffin, Reference Welsh and Tiffin2012) and validation that their experiences had been named as a condition (Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018). Simply sharing problems safely without upsetting those close to users reduced stress (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2014) and was viewed as a form of treatment (Welsh and Tiffin, Reference Welsh and Tiffin2012). Fears could continue after receipt of the ARMS label and disclosing this to others (Welsh and Tiffin, Reference Welsh and Tiffin2012); some reported negative reactions from those around them (Hardy et al., Reference Hardy, Dickson and Morrison2009; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012; Welsh and Tiffin, Reference Welsh and Tiffin2012), but these were often offset by acceptance and supportive experiences (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2010; Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018; Welsh and Tiffin, Reference Welsh and Tiffin2012) leading to reductions in anxiety, improvements in emotional well-being and increased access to psychological help (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2010; Hardy et al., Reference Hardy, Dickson and Morrison2009).

Therapeutic relationships

The therapeutic relationship was the most commonly endorsed theme across studies. Specific qualities were outlined as important in the development of positive working relationships and was highlighted across eight studies.

Both groups placed high value on therapeutic relationships with EIP staff, strengthened by their specific qualities and approaches, i.e. youth-friendliness, informality, genuineness, and flexibility tailored to individual needs which facilitated engagement (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2014; Barr et al., Reference Barr, Ormrod and Dudley2015; Lester et al., Reference Lester, Marshall, Jones, Fowler, Amos, Khan and Birchwood2011; Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018); when opening-up, being listened to and receiving empathic non-judgemental responses (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2014; Barr et al., Reference Barr, Ormrod and Dudley2015; Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018). Users valued working collaboratively with HCPs (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2010; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012) and consistency in seeing the same person regularly, having HCPs sticking with them when things were difficult (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Ormrod and Dudley2015) and building a long-term relationship with one person with whom they could talk freely, and feel understood, which facilitated engagement (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2014; Lester et al., Reference Lester, Marshall, Jones, Fowler, Amos, Khan and Birchwood2011). When this was compromised, users reported disruption in having to repeat things to various HCPs, which affected the ability to build trust (Lester et al., Reference Lester, Marshall, Jones, Fowler, Amos, Khan and Birchwood2011; Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018).

For the FEP group, experiencing a strong working alliance, often with care coordinators, was instrumental for recovery (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Ormrod and Dudley2015; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012). This relationship allowed for therapeutic support and facilitated access to other interventions, i.e. psychosocial intervention (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Ormrod and Dudley2015; Lester et al., Reference Lester, Marshall, Jones, Fowler, Amos, Khan and Birchwood2011) and further engagement with others (i.e. HCPs, agencies and peers) (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Ormrod and Dudley2015; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012; Lester et al., Reference Lester, Marshall, Jones, Fowler, Amos, Khan and Birchwood2011). How users were treated, being taken seriously, provided with validation and valued beyond their illness was often endorsed over specific intervention factors (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Ormrod and Dudley2015).

Family and peers

Service users described the importance of the role of peers and family in seven of the studies in the review.

Some users from both groups opted to rely on professional support due to a lack of closeness or understanding and fears regarding possibly stigmatising responses within their relationships (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2010) and previous negative experiences within the family (i.e. feeling misunderstood and judged) (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012).

Across the ARMS population there was evidence of poor or lost social and family relationships often due to trauma and ARMS experiences which negatively affected users’ mental health and well-being (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2010).

Both groups worried about responses from peers and family when sharing their experiences openly. Some FEP users experienced shame or fear of worrying those close to them (Lester et al., Reference Lester, Marshall, Jones, Fowler, Amos, Khan and Birchwood2011). Some ARMS users feared discrimination, stigma or not being taken seriously; some instances of stigma were noted within the workplace and from friends and family (Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018). However, many reported receiving sympathy and understanding (Lester et al., Reference Lester, Marshall, Jones, Fowler, Amos, Khan and Birchwood2011; Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018; Welsh and Tiffin, Reference Welsh and Tiffin2012); support with referral into services and others around them opening up regarding their own mental health difficulties (Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018).

The FEP group often benefited from emotional and practical support from family and friends (i.e. financial support, accommodation, shopping) (Lester et al., Reference Lester, Marshall, Jones, Fowler, Amos, Khan and Birchwood2011), and social and family support was often viewed as important as other interventions (i.e. CBT, medication) (Lester et al., Reference Lester, Marshall, Jones, Fowler, Amos, Khan and Birchwood2011). Relationships across user, family and care coordinators was highly influential in recovery (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Ormrod and Dudley2015), with some users feeling that support and closeness with families and carers had increased due to EIP services facilitating family and carer understanding and engagement so that they were better equipped to support the user. This allowed families/carers to better advocate for treatment (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Ormrod and Dudley2015; Lester et al., Reference Lester, Marshall, Jones, Fowler, Amos, Khan and Birchwood2011) and engage in intervention work, i.e. relapse plans (Lester et al., Reference Lester, Marshall, Jones, Fowler, Amos, Khan and Birchwood2011).

The positive role of sharing experiences with peers was highlighted across both groups, with many users expressing a keen interest in sharing with others who were affected similarly through group therapy (Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018; Welsh and Tiffin, Reference Welsh and Tiffin2012). For the FEP group peer support reduced social isolation, helping users to feel understood and creating a sense of belonging which reduced shame, increased confidence and provided opportunities to help others, thus increasing agency (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012). Group CBT also facilitated learning from others, instilling hope and reducing anxiety and stress levels, with participants expressing a preference to work alongside peers of a similar age (Welfare-Wilson and Jones, Reference Welfare-Wilson and Jones2015).

Coping

This theme related to users managing and coping with their experiences and was explored in all of the studies reviewed.

ARMS users often presented as active in their attempts to cope with experiences across the trajectory of their involvement with EIP, often demonstrating a keenness for involvement and understanding (Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018) and through use of personal coping mechanisms, i.e. family support, spirituality and inner strength (Hardy et al., Reference Hardy, Dickson and Morrison2009). Psychological input increased ARMS users’ coping repertoires (Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018), with therapy sessions often cited as informal which was normalising, giving users the space to talk things through (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2014; Welsh and Tiffin, Reference Welsh and Tiffin2012). For ARMS users, non-intervention specific aspects of coping were related to a sense of safety and security in knowing that everyday support was available through EIP (Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018), and through monitoring assessments which augmented perceived coping ability, mood and optimism via engagement, informality, normalisation and practical support (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2014).

A key factor in managing and coping with experiences was normalisation facilitated through involvement with EIP. This generated relief through knowing others had similar experiences (often valued above interventions) (Welfare-Wilson and Jones, Reference Welfare-Wilson and Jones2015; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012; Lester et al., Reference Lester, Marshall, Jones, Fowler, Amos, Khan and Birchwood2011; Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018; Welsh and Tiffin, Reference Welsh and Tiffin2012) and that everyone is susceptible and it is possible to get through such experiences (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Ormrod and Dudley2015; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012). Normalisation fostered hope for the future in reducing fears that users were not ‘going mad’ or were ‘abnormal’ (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Ormrod and Dudley2015), and was facilitated through reassurance, empathic responses (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2014) and an informal approach to language (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2010; Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2014).

Another coping factor was learning and understanding; for ARMS users this increased a sense of agency through being actively involved and learning about the condition; however, some users reported that knowing about the condition did not change anything and they were determined to carry on as before (Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018). The FEP group also wanted to understand their illness: why they had become unwell and learning about early warning signs and triggers was important (Lester et al., Reference Lester, Marshall, Jones, Fowler, Amos, Khan and Birchwood2011), alongside acquiring coping skills in helping to manage stress and increase confidence (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Ormrod and Dudley2015).

Participants in both groups could be observed to move from passive to agentic stances in dealing with experiences (this appears to be related to impacts on self-identity in their ‘personal journey’); for the ARMS users this was seen in early stages where individuals either attempted to actively help themselves or waited for symptoms to disappear; the latter often failed (Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018). The FEP group’s progress also appeared to correspond with the way in which individuals accepted and integrated their experiences but this happened often later during their involvement with EIP. FEP users usually moved from avoidance of psychosis experiences to acceptance and control, which positively correlated with recovery (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012).

Perceived level of control affected coping; FEP users expressed a sense of hopelessness when control was taken away (which relates to views on intensive sustained engagement indicated in ‘the journey’), and being resigned to a life with psychosis, whereas others expressed feeling as if level involvement was their choice (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012). In contrast, some FEP users emphasised the value of help during a crisis (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Ormrod and Dudley2015), and ARMS users could fear withdrawal of support in case of problems returning (Hardy et al., Reference Hardy, Dickson and Morrison2009), indicating an acceptance and knowledge of the need for support when problems held the risk of intensifying.

Taking active control helped to address and challenge experiences for both groups; for FEP user’s social (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Ormrod and Dudley2015) and family support (Lester et al., Reference Lester, Marshall, Jones, Fowler, Amos, Khan and Birchwood2011) and partnership working (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012) helped individuals cope; and for ARMS users the use of personal coping strategies and self-efficacy was important (Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018). Both groups valued psychological support which engendered a sense of control and security (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012; Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018). Whilst many users attributed aspects of progress to involvement with EIP, they recognised a need for taking personal responsibility for the future (Hardy et al., Reference Hardy, Dickson and Morrison2009; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012).

Table 2. Exemplar quotes for each theme

Cognitive behavioural therapy

CBT techniques were instrumental in increasing resilience, often through increased understanding around experiences, learning and normalisation (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Ormrod and Dudley2015; Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2010; Byrne and Morison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2014; Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018; Welfare-Wilson and Jones, Reference Welfare-Wilson and Jones2015). Benefits of CBT approaches were highlighted in eight studies.

Despite the key role of an informal approach adopted within sessions for ARMS users, specific CBT techniques were endorsed, i.e. agenda setting, evidence-gathering and reappraisal of distressing experiences (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2014), and the group valued the collaborative nature of the intervention (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2010). Disclosure in therapy regarding talking about symptoms or previous life experiences and engaging in homework were cited as difficult, as it encouraged further self-examination; however, users recognised the need for this in order for therapy to be effective (this also spans across disclosure and associated benefits) (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2014).

For ARMS users the formulation process (maintenance and longitudinal) helped to normalise their experiences and facilitated understanding around symptoms in the context of life experiences (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2014), leading to discoveries about what could be worked on and how (Bryne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2010; Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018). This provided a route to rethink and reappraise unhelpful thoughts, beliefs and behaviours (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2014) through learning about the links with symptoms (Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018). Users cited improved social functioning as a valued outcome of CBT, i.e. they spent more time with others and in previously avoided places as a result of applying techniques in feared situations, e.g. using rationalisation when feeling paranoid (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2014).

For the FEP group CBT was often valued later in the treatment pathway (after building therapeutic relationships, understanding the label and receiving medical care) (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Ormrod and Dudley2015). Some users expressed initial avoidance and anxiety prior to engaging in CBT work; however, when this was overcome, they were willing to utilise skills upon completion, especially coping strategies (also behavioural experiments, diary work) with others involved in their care (i.e. care co-ordinators), and they also valued the CBT model (Welfare-Wilson and Jones, Reference Welfare-Wilson and Jones2015). Although indicated by only one participant, it is noteworthy that CBT was cited as less helpful when on a high dose of medication or not being in the right frame of mind (in line with ‘the journey’ and psychological input being valued at different time points) (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Ormrod and Dudley2015).

Both groups highlighted CBT as instrumental in increasing their coping repertoire through learning; upon completion of CBT, ARMS users reported an increased psychosocial understanding of difficulties, and use of adaptive strategies when faced with these (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2010; Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2014; Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018). FEP users reported increased learning and understanding of the links between experiences, symptoms, and impact upon mood, through both individual and group CBT formats (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Ormrod and Dudley2015; Welfare-Wilson and Jones, Reference Welfare-Wilson and Jones2015).

The journey

This theme highlights a common journey when moving through EIP services, which referred to experiences preceding service involvement, accessing help, understanding and prioritising needs and consideration of moving on, as endorsed by seven studies in the review.

For the ARMS group, the beginning of the journey often consisted of identification of the need for help due to the knowledge something was wrong (Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018; Welsh and Tiffin, Reference Welsh and Tiffin2012), with users outlining either gradual build-up of symptoms, others with sudden changes in perception/thinking (Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018), and some when at breaking point (Hardy et al., Reference Hardy, Dickson and Morrison2009). Triggers were often related to stress at work, illness, or drug use (Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018).

Both groups valued mental health support at inception of problems; for the ARMS group this meant knowing something was wrong so that it could be dealt with (Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018; Welsh and Tiffin, Reference Welsh and Tiffin2012); for the FEP group this often meant recognising and managing early symptoms, i.e. being given a diagnosis to explain their illness, understanding this and learning about triggers in order to manage them. These mechanisms were often prioritised above learning different skills to stay well or the use of psychological interventions in the earlier stages of problems. However, later, orientation towards recovery was aligned with being supported to consider and reach other goals (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Ormrod and Dudley2015).

Both groups valued psychological input later in their recovery journey after perceived hierarchical needs had been met, outlining the need for different interventions and support at different time points (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Ormrod and Dudley2015). This was often due to progression and regression (Hardy et al., Reference Hardy, Dickson and Morrison2009) and in line with the stage the user was at in relation to confronting and managing their experiences (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012). Both groups referred to prioritising and reaching goals distinct from symptom reduction (i.e. addressing housing issues) (Hardy et al., Reference Hardy, Dickson and Morrison2009; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012).

For the ARMS group moving forwards was associated with post-therapy changes through understanding difficulties, learning to cope long-term using relevant tools, and through improved social functioning (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2014; Hardy et al., Reference Hardy, Dickson and Morrison2009). However, some users feared having no support if problems resurfaced (Hardy et al., Reference Hardy, Dickson and Morrison2009) and would have appreciated further practical support (Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018). In contrast, FEP users appreciated flexibility and negotiation regarding service provision, often viewing three years sustained engagement as too intensive (Lester et al., Reference Lester, Marshall, Jones, Fowler, Amos, Khan and Birchwood2011), despite recognising that regular contact with EIP was necessary to understand their experiences and move forwards (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012).

Some ARMS users were aware of negative stereotypes about psychosis (Uttinger et al., 2012); however, positive responses from others and support received appeared to mediate these experiences (see talking and disclosure, relationships with family and peers). However, FEP users often described changes in self-identity due to their experiences (i.e. loss of normality, changes in appearance) and service involvement, leading to fear of stigma and self-stigma (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012; Lester et al., Reference Lester, Marshall, Jones, Fowler, Amos, Khan and Birchwood2011). The way EIP was viewed could affect this, i.e. if it was viewed as different from mainstream services this could induce shame and separation, but if viewed as helping to reduce stigma this could positively affect involvement (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012).

Some FEP users discovered a more positive self-concept following EIP involvement due to their experiences being noticed, allowing users to face things and re-establish aspects of life that had been lost (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012) enhancing their coping strategies and ability to meet and share experiences (Lester et al., Reference Lester, Marshall, Jones, Fowler, Amos, Khan and Birchwood2011). Conversely, some described an ongoing sense of detachment from their world and others, and a lack of understanding of a new self (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012; Lester et al., 2012).

Discussion

The aims of this qualitative synthesis were to explore views on EIP provisions, namely CBT, and what was valued in order to make inferences regarding enhancing support. Findings outlined factors which were not always intervention specific; however, these impacted on the users’ experiences of support, are in line with aims of the review and have important implications for provision. An example is the role of disclosure; whilst inclinations to initially disclose experiences come prior to service engagement, this was noted to be further facilitated through various aspects of EIP support (i.e. CBT, indicated as providing a safe context for disclosure; Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2010; Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2014; Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018; Welfare-Wilson and Jones, Reference Welfare-Wilson and Jones2015). Disclosure experiences are also closely linked with the beginning of ‘the journey’; indicated in the review as an imperative time frame, with both groups valuing support at inception of their problems. Thus, it is important for practitioners and policy makers to consider the experiences of those accessing support, and initial engagement. Fears about accessing support have been noted elsewhere (i.e. ARMS users’ concern regarding others’ attitudes), and calls have been made for services to address health beliefs and consider access issues related to stigma and difficult emotions (Ben-David et al., Reference Ben-David, Cole, Brucato, Girgis and Munson2019). Wider issues regarding difficulties associated with accessing services may also affect disclosure and initial experiences, with calls made for more targeted and streamlined pathways into services (Allan et al., Reference Allan, Hodgekins, Beazley and Oduola2020). Policy supports a public health approach to identification of early psychosis which may facilitate earlier disclosure and more timely access. Within EIP, attention to beliefs about accessing and engaging with services, supporting other services in their referral systems (NICE, 2020) and stigma challenging initiatives may help to address these issues, i.e. liaison with employers (Izon et al., Reference Izon, Au-Yeung and Jones2020). Research into the value of specific up and running programmes within EIP, i.e. individual placement support (IPS) and its effects may clarify the effectiveness of these programmes on stigma across individual networks. However, the evidence base regarding effectiveness of IPS generally within the UK is small (Heffernan and Pilkington Reference Heffernan and Pilkington2011), with limited recent updates.

High value was placed on the therapeutic relationship, which echoes previous literature (Boydell et al., Reference Boydell, Stasiulis, Volpe and Gladstone2010), where positive qualities of HCPs, and the way individuals are treated, influences levels of engagement. The importance of building therapeutic relationships is widely cited as holding potential to enhance interventions and affect willingness to continue (Gee et al., Reference Gee, Notley, Byrne, Clarke, Hodgekins, French and Fowler2018; Morrison and Barratt, Reference Morrison and Barratt2010; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Burke and Morrison2015) and is a catalyst for enhancing other valued aspects of support. The instrumental role of wider relationships in augmenting support was outlined across both groups, but particularly with the FEP group in enhancing a sense of control. The literature recommends provision of family intervention (FI) across both groups (NICE, 2014); however, uptake across the country is low for the FEP group (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2020), and ARMS is research still in its relative infancy (Izon et al., Reference Izon, Au-Yeung and Jones2020; Law et al., Reference Law, Izon, Au-Yeung, Morrison, Byrne, Notley and French2019). Where provision of traditional FI is not possible, a less intensive approach may be of benefit, i.e. use of guided family self-help resources during clinical contact, psychoeducation and early support which may help improve carers’ quality of life, benefiting the user (Izon et al., Reference Izon, Au-Yeung and Jones2020). Guidance outlines a minimum expectation that carer focused education support programmes are offered to all FEP carers (NICE, 2014). This may consist of stand-alone interventions where FI is not possible, i.e. general emotional support, provision of signposting to relevant resources and networks, psychoeducational interventions, carer groups, relapse prevention work (Onwumere, Reference Onwumere2018). Inclusion of carers in therapy sessions or associated homework tasks in CBT can further encourage a holistic approach to care. Where family histories may be traumatic there is a role for HCPs to explore this (with consent) due to correlations between trauma and psychosis symptoms and recommendations to formulate these experiences to guide treatment planning (Mayo et al., Reference Mayo, Corey, Kelly, Yohannes, Youngquist, Stuart and Loewy2017).

Both groups expressed an enthusiasm to share their experiences with peers. Research has suggested the value of peer support in developing individuals’ confidence, engaging in more relationships, work and education and feeling more hopeful about themselves and the future (Repper and Carter, Reference Repper and Carter2010). Guidance advises that EIP services should provide encouragement to access peer support organisations, offering the opportunity to meet and engage with other service users (Royal College of Psychiatrists and Early Intervention in Psychosis Network, 2018). However, research into peer support initiatives remains limited. The existing evidence base looks to established populations with serious mental illness (Davidson et al. Reference Davidson, Bellamy, Guy and Miller2012), and is lacking where organisational and team benefits are concerned (White et al., Reference White, Price and Barker2017).

Coping and attempts to manage experiences spanned across all studies. There appeared to be an inverse experience of coping across groups, whereby ARMS users often presented with high motivations to cope early in their experiences (corroborated elsewhere, i.e. Gee et al., Reference Gee, Notley, Byrne, Clarke, Hodgekins, French and Fowler2018), through learning about these and later expressing some concern regarding withdrawal of support. FEP users often accepted and confronted experience later, appreciating flexibility around service involvement. These differences may require similar proactive efforts to augment coping in both groups at initial involvement in order to address any avoidance or passivity (it is noted elsewhere that ARMS users may rely on passive rather than active coping styles thus increasing stress) (Kang et al., Reference Kang, Bang, Lee, Lee, Yoo and An2018), encourage early acceptance and integration for FEP users, negate risks of fearing being resigned to a life with psychosis, and capitalising on ARMS users’ motivation to increase self-efficacy and reduce anxiety around discharge. Both groups had positive outcomes when taking active control to cope with experiences which may be fostered by drawing on existing coping mechanisms and supporting their use, i.e. family support in helping to explore more adaptive coping strategies (Izon et al., Reference Izon, Au-Yeung and Jones2020). Moving from a passive to an agentic stance has been correlated with an increase in power and coping, particularly as a process of CBT for those with psychosis (Berry and Hayward, Reference Berry and Hayward2011). We can view interventions which seek to augment involvement as important, i.e. sharing control through collaborative working in CBTp and targeting cognitive appraisals which may be determinants of coping styles within ARMS groups (Kang et al., Reference Kang, Bang, Lee, Lee, Yoo and An2018).

Normalisation, learning and understanding – features of many aspects of support found in the review – increased coping and are intrinsically interlinked. Normalisation can be supported throughout all stages of EIP involvement, correlated with review findings, i.e. normalising responses during initial involvement may facilitate disclosure and engagement, and the opportunity to share with peers can reduce distress. Learning and understanding regarding ARMS and FEP labels positively affected coping and understanding experiences. Use of psychosocial intervention (PSI), i.e. coping strategy enhancement, self-monitoring, motivational techniques and problem solving, have been found to improve overall quality of life for those with psychosis and have been recommended for FEP users (Ruggeri et al., Reference Ruggeri, Bonetto, Lasalvia, Fioritti, De Girolamo and Santonastaso2015). Specifically, use of psychoeducational materials as early as possible may serve to increase coping through increased understanding and normalisation (Favrod et al., Reference Favrod, Crespi, Faust, Polari, Bonsack and Conus2011), and can be actively utilised within therapeutic relationships. These strategies may be used prior to, or when CBT is not prioritised, which was also found to increase coping through its focus on learning and normalising approach.

There were some differences across CBT findings, i.e. ARMS users reported more intervention specific components as useful, and FEP users valued this later, with the input of key worker help in practising skills. Variations are not surprising given both differences in the trajectory of problems and EIP input (early use of CBT as an often stand-alone 6-month treatment offer for ARMS in comparison with a 3-year multidisciplinary intensive approach for FEP users) (NICE and NHSE, 2016). Both groups highlighted the value of understanding experiences, their impacts and learning strategies to manage these through CBT, which is corroborated by existing literature which espouses the value of normalisation, psychoeducation and formulation, linking these with increased understanding, acceptance, social and functional ability, for those with psychosis (Berry and Hayward, Reference Berry and Hayward2011; Kilbride et al., Reference Kilbride, Byrne, Price, Wood, Barratt, Welford and Morrison2013; Morrison and Barratt, Reference Morrison and Barratt2010). Importantly, these transdiagnostic features of CBT may be modelled in routine practice and can be supported by trained therapists; evidence has suggested that delivery of CBT interventions by staff with non-specific training can be highly effective (Ekers et al., Reference Ekers, Richards, McMillan, Bland and Gilbody2011; Waller et al., Reference Waller, Craig, Landau, Fornells-Ambrojo, Hassanali, Iredale and Garety2014). Encouragement of basic formulation development may aid initial understanding and normalisation, socialising users to the CBT model and can be facilitated in routine clinical practice by HCPs (Cox, Reference Cox2021).

Both groups indicated a hierarchy of needs related to support, i.e. valuing practical support earlier and psychological input later which makes sense given wider motivational theory (McLeod, Reference McLeod2007) and specific psychosis literature (French and Morrison, Reference French and Morrison2004). This may have implications for ARMS users (due to a short CBT focused treatment window) who were also found to value a flexible and informal approach, and especially younger ARMS users who have been found to have lower attendance rates and may be less receptive to CBT (Stain et al., Reference Stain, Bucci, Baker, Carr, Emsley, Halpin and Crittenden2016). The FEP group also appreciated flexibility regarding psychological input. This is important given evidence suggesting that engagement in CBT can be hard work despite it being acknowledged as beneficial in similar populations (Gee et al., Reference Gee, Notley, Byrne, Clarke, Hodgekins, French and Fowler2018; Kilbride et al., Reference Kilbride, Byrne, Price, Wood, Barratt, Welford and Morrison2013; Valmaggia et al., Reference Valmaggia, Tabraham, Morris and Bouman2008). Awareness of the stage the person is at in their personal journey offers insights as to where and how support should be targeted, which may negate risks of offering this early and potentially causing iatrogenic harm.

Less structured interventions have been advocated across both groups where flexibility is required; i.e. non-directive listening and active engagement has been suggested with ARMS users (Stain et al., Reference Stain, Bucci, Baker, Carr, Emsley, Halpin and Crittenden2016) in line with a stepped care approach often advocated with this group (McGorry et al., Reference McGorry, Killackey and Yung2008). For the FEP group interventions other than formal CBT or FI may be of value and preferable to users at the beginning of their journey, which may also be less stigmatising (Bird et al., Reference Bird, Premkumar, Kendall, Whittington, Mitchell and Kuipers2010; Marshall and Rathbone, Reference Marshall and Rathbone2011). This approach may reduce the risks of experiencing detachment and negative changes in self-identity found in the review. Later consideration of CBT may positively affect self-image, acceptance and self-esteem through normalisation, understanding and coping (Morrison and Barratt, Reference Morrison and Barratt2010). These are important considerations given that achievement of identity has been prioritised within this group (Boydell et al., Reference Boydell, Stasiulis, Volpe and Gladstone2010). Sensitively staging support may foster disclosure, therapeutic relationship building and lay foundations for psychological input and use of more complex interventions.

The strengths of this review are that focus was given solely to service user led papers, thus attempting to provide a rich narrative from a users’ perspective. The fact that the previous CBT reviews discussed have included only one at risk study (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Burke and Morrison2015) indicates that this review is important in synthesising the perspectives of this group which needs to be built upon.

Limitations and future research

The nine eligible studies consisted of five ARMS and four FEP studies. Two were CBT studies (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2014; Welfare-Wilson and Jones, Reference Welfare-Wilson and Jones2015), three made reference to CBT (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Ormrod and Dudley2015; Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2010; Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018) and the remainder refer to psychological intervention (Hardy et al., Reference Hardy, Dickson and Morrison2009; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Collinson and das Nair2012; Lester et al., Reference Lester, Marshall, Jones, Fowler, Amos, Khan and Birchwood2011; Welsh and Tiffin, Reference Welsh and Tiffin2012). We might assume psychological intervention pertained to use of CBT, especially given national guidelines (NICE and NHSE, 2016); however, we cannot draw firm conclusions around this, making generalisations difficult.

One study utilised mixed methods, the qualitative component using a framework which generated a coding matrix of themes and categories (Welfare-Wilson and Jones, Reference Welfare-Wilson and Jones2015). Another condensed data using qualitative content analysis (Uttinger et al., Reference Uttinger, Koranyi, Papmeyer, Fend, Ittig, Studerus, Ramyead, Simon and Riecher-Rössler2018). Another utilised Q-methodology, which may be critiqued as it forces respondents to offer opinions based on pre-determined items (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Ormrod and Dudley2015). These studies, although arguably not fully meeting criteria against PEO, were deemed useful regarding conclusions as they identified the views of patients and all made direct reference to CBT, giving insights across all categories.

Only three studies reported Patient, Carer and Public Involvement (PCPI) activity; a service user researcher conducting interviews and contributing to analysis of results (Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2010; Byrne and Morrison, Reference Byrne and Morrison2014) and involving a service user in refining data (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Ormrod and Dudley2015). The majority of studies were not ethnically diverse (three failed to record ethnicity), reducing generalisability and an understanding of how culture may shape opinions of mental health services. Age of participants in the studies also indicates a limited voice for those who are over 35, despite increased age range provision outlined in recent guidelines (NICE and NHSE, 2016).

This review revealed an absence of research conducted with the EIP population concerning their psychological and treatment preferences, which has been outlined elsewhere (Boydell et al., Reference Boydell, Stasiulis, Volpe and Gladstone2010). Issues regarding ARMS service variation and patchy provision (Stain et al., Reference Stain, Mawn, Common, Pilton and Thompson2019) may explain limited literature regarding service users’ experiences. The focus of the included studies may explain the identified themes highlighting relationships and personal factors rather than intervention specific themes. Further research should explore the impacts of EIP commissioned interventions from service users’ perspectives to further elucidate valued aspects of support. More CBT studies are required to clarify specific valued mechanisms and interventions (i.e. exactly how psychological support serves to affect sense of security, control and resultant coping). Both groups expressed an enthusiasm for group support, which may benefit from further exploration, i.e. research into use of peer networks and group CBT undertaken within EIP services. Such research has the potential to inform effective and holistic care and influence psychological therapy delivery.

Conclusion

Despite the limitations of the evidence base in this area, the review confirms the importance of relationships in facilitating disclosure and engagement. Therapeutic relationships are best cultivated through efforts to work collaboratively and consistently with individuals, understanding the stage of their personal journey which is key regarding targeting support at the relevant level. Developing coping skills is also important, which may be encouraged through learning, understanding and normalisation, enhanced through the principles of, and transdiagnostic interventions of, CBT.

This is a sound starting point for EIP care delivery, although further research into specific interventions and mechanisms of support is required for individual groups who are at different points in their journey and receive different levels of care. This is also indicated by group differences regarding experiences of CBT, coping responses and service flexibility preferences.

Key practice points

-

(1) Normalising responses to experiences throughout involvement, especially early on, is key in fostering disclosure and engagement and may address fears of stigma.

-

(2) A keen focus to building early coping skills may instil hope, reduce potential avoidance and increase ability to engage in targeted interventions, i.e. CBT. Understanding individual coping skills and building on these enhances individuals’ sense of control regarding their experiences.

-

(3) Consideration should be given to the role of families and peers in the therapeutic journey for both groups, and how this could augment interventions, i.e. through targeted family intervention, guided carer self-help resources, care and relapse prevention planning.

-

(4) Encouraging involvement in CBT activity from HCPs and carers/family, i.e. with homework tasks, engaging with the therapy blueprint will support ongoing progress and maximise use of skills outside and beyond sessions.

-

(5) Learning and understanding are imperative in cultivating coping and can be supported through provision of psychoeducational materials and facilitated through use of individual formulation.

-

(6) Understanding the stage of the person’s individual journey will help target support (i.e. whether basic needs require addressing prior to psychological input).

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

L.C. was partly funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care North West Coast. C.M. is partly funded by the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration North West Coast. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, National Health Service or Department of Health and Social Care.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethics statement

Not applicable due to nature of article.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Author contributions

Lauren Cox: conception and design of the paper, data collection, analysis, synthesis and interpretation; writing full first draft, responding to reviewers’ comments; handling the revision and re-submission of the revised manuscript up to the acceptance of the manuscripts; final approval of version to be published. Colette Miller: support revising first author drafts; scientific advisor regarding methodology; second draft data collection, ensuring paper adhered to PRISMA guidelines; manuscript correction/proofreading (technical and language editing).

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.