Introduction

Depression in older adults is a disabling condition associated with increased suicide, morbidity, self-neglect and decreased cognitive, social and physical functioning (Fiske et al., Reference Fiske, Wetherall and Gatz2009; Rodda et al., Reference Rodda, Walker and Carter2011). However, it remains under-diagnosed for a variety of reasons, including communication and cognitive impairment at the patient level, focus on medical conditions at the medical level, and availability of mental health professionals at the systemic level (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Poss, Hides, Jones, Stones and Fries2008). Research has identified a high occurrence of mood disorders in older adults with and without physical health conditions (Byers et al., Reference Byers, Yaffe, Covinsky, Friedman and Bruce2010; Mehta et al., Reference Mehta, Simonsick, Pennix, Schulz, Rubin, Satterfield and Yaffe2003), yet anxiety symptoms are neglected and under-treated in older adults (Laidlaw, Reference Laidlaw and Bernard2013; Vink et al., Reference Vink, Aartsen and Schoevers2008). Factors such as ailing health, dementia, being a carer, social isolation, and loss of a partner, which are common in later life, may account for high prevalence rates for anxiety (24%) (Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Jackson and Ames2008) and depression (22–28%) (MHF, 2018; Singleton et al., Reference Singleton, Bumpstead, O’Brien, Lee and Meltzer2000). Moreover, increasing co-morbid depression and anxiety in later life carries associated risks of cognitive decline and functional disability (Diefenbach and Goethe, Reference Diefenbach and Goethe2006) and treatment is central to minimising these risks.

Various models have been developed for the treatment of depression and anxiety disorders (e.g. Beck, Reference Beck1967; Dugas et al., Reference Dugas, Gagnon, Ladoucer and Freeston1998; Wells, Reference Wells1997; Westbrook et al., Reference Westbrook, Kennerley and Kirk2007), with strong empirical support for their use, particularly in working-age populations. However, in accordance with clinical guidelines, these models tend to focus on single conditions. Many older adults present to services with complex mental and physical health issues; treatment options therefore need to account for multi-morbidity (Guthrie et al., Reference Guthrie, Payne, Alderson, McMurdo and Mercer2012) in order to meet the needs of this population. Currently, co-morbidity is inconsistently accounted for in NICE guidelines (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, McMurdo and Guthrie2013), with clinicians left to select specific models that ‘best fit’ complex presentations.

Transdiagnostic, case formulation-driven interventions, as advocated by Persons (Reference Persons2005), offer an alternative approach that may overcome issues of multi-morbidity. Although support for this approach over standard protocols is equivocal, Tarrier and Calam (Reference Tarrier and Calam2002) recognise that existing studies are underpowered but argue that case formulation approaches should not be precluded from clinical trials. Case formulation approaches are gaining credence as research indicates that commonalities in the psychological vulnerabilities, co-morbidity and maintaining factors across emotional disorders may outweigh the differences (McEvoy et al., Reference McEvoy, Nathan and Norton2009). Persons (Reference Persons2012) advocates the use of the case formulation approach in cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which benefits from being principle-driven rather than protocol-driven, and helps clinicians address various issues that are overlooked in protocol-informed work.

Older adults seeking psychological support may benefit from CBT to explore core beliefs and assumptions that have contributed to dysfunctional patterns of thinking and subsequent psychological distress (Beck, Reference Beck1967), and CBT can help develop strategies that promote well-being. However, adaptations for age-related differences in working memory, attention, sensory impairment, etc. may be necessary along with consideration of cohort beliefs, physical health and intergenerational relationships (Evans, Reference Evans2007). Although CBT with older adults is found to be more effective than placebo and wait list controls (Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, Asnaani, Vonk, Sawyer and Fang2013), CBT is not always more effective than anti-depressant medication alone (Peng et al., Reference Peng, Huang, Chen and Lu2009). It is, therefore, also worth considering additional therapeutic interventions for this population.

Another therapeutic approach that may be beneficial for older adults is compassion-focused therapy (CFT), as it has an emerging evidence base for shame reduction (Ashworth, Reference Ashworth2014). This is pertinent as research indicates that older adults experience increased stigma and shame, particularly associated with mental illness (Connor et al., Reference Connor, Copeland, Grote, Koeske, Rosen, Reynolds and Brown2010), which is a significant barrier to help-seeking. CFT fosters the development of compassion and acceptance towards self and others to thwart self-criticism and shame (Boersma et al., Reference Boersma, Hakanson, Salomonsson and Johansson2014). CFT interventions that promote the development of self-compassion result in reductions in anxiety, depression and stress (Craig, Reference Craig2017; Neff and Germer, Reference Neff and Germer2013) and improvements in self-esteem (Andersen and Ramussen, Reference Andersen and Rasmussen2017). Research indicates that self-compassion is linked to psychological flourishing and reduced psychopathology (Germer and Neff, Reference Germer and Neff2013) and CFT is considered to be a beneficial intervention for older adults (Collins et al., Reference Collins, Gilligan and Poz2018). Although CFT is receiving increasing interest as an intervention for depression and anxiety (Leaviss and Uttley, Reference Leaviss and Uttley2015), its relative newness means it has not yet accrued an evidence base as strong as CBT, for example. While CFT has been delivered within a CBT programme (Gilbert and Proctor, 2006), this was in a group therapy setting and focused on shame reduction. To date, there is a dearth of literature on integrated CFT and CBT interventions with older adults and no studies use a case formulation-driven approach using combined CBT and CFT with a single-case design. This study, therefore, aims to add to the literature by exploring the utility of this approach with an older adult with complex mental and physical health needs.

Method

Design

An A–B single case experimental design (Barlow and Herson, Reference Barlow and Hersen1984) was employed for this case study. Baseline assessments (A) were established at four time points prior to 28 weeks of CBT and CFT intervention (B) with a clinical psychologist in training.Footnote 1

Participant

This study reports the case of Ray,Footnote 2 a 68-year-old Caucasian male who was referred for psychological therapy by his GP for help with low mood and anxiety. Ray lived alone and had no contact with his family; his parents were no longer alive and he had not spoken to his siblings in many years. Ray had good relationships with his long-term partner, and a close friend, whom he saw regularly.

Presenting problems

Ray presented with low mood, anxiety and difficulties in regulating his emotions. He reported increased anxiety in social settings and a reluctance to leave his home, low motivation, fatigue and difficulties in eating and sleeping. Ray struggled with complex physical health issues, including lung, musculoskeletal and endocrine issues.

Case history

Ray reported having an unhappy childhood that involved years of physical and emotional abuse from his mother. Ray described growing up in the context of poverty, parental mental health issues, and school bullying. Ray described difficult relationships with family members and felt that he never experienced love or adequate care. He recalled a period of separation when he and his siblings spent time in different care homes. Ray encountered childhood sexual abuse (CSA) from a family member and considered jumping off a building in an attempt to receive love, care and attention from his mother. Ray struggled academically and left school early to seek employment. Ray then embarked on a positive phase of his life; he enjoyed the independence afforded by earning a wage, and he attributed his happiness during this time to being away from his family and leaving his unhappy childhood behind. He described improved self-esteem during this time as a result of forming and maintaining good relationships with friends, colleagues and girlfriends and having an active social life. During this time Ray lived with a friend, whose kind mother treated Ray like her own child and showed Ray what it felt like to be cared for.

Ray described a long history of anxiety, depression and alcoholism following an injury during his 30s, which resulted in him losing his business, as he could no longer work. However, Ray experienced sobriety for many years following a spell in rehabilitation. Since the accident, where Ray fell and hit his head, he reported having what he termed as ‘delusional episodes’. He described these as hearing a critical voice, which sounded like his own but said the content was similar to the voice of a particularly critical family member. Ray encountered these episodes intermittently over the years and said they occurred when difficult life events caused him significant stress and anxiety with concurrent low mood. Ray had no diagnosis of psychosis and professionals had suggested the voice was trauma-related and induced by stress. Ray previously engaged in CBT and art therapy to address childhood trauma and alcohol dependency, which had helped him to develop some emotion regulation skills, but he identified this as an ongoing area of difficulty. Ray had a supportive long-term girlfriend but had severed all ties with his family. Ray experienced suicidal thoughts. He attempted suicide many years before, but cited not wanting to go through with it and not wanting to leave his girlfriend as key reasons not to try again. He had previously seen a psychiatrist, but it was several years since his last appointment. Ray described his eating as erratic, sometimes neglecting to eat and care for himself. He consumed caffeine but not alcohol or drugs, except prescription medication for depression, anxiety and physical health issues.

Measures

The following measures were used to assess the impact of therapy:

Patient Health Questionnaire

(PHQ-9), administered weekly to assess symptoms of depression. The PHQ-9 is considered to be a reliable and valid measure of depression, with Cronbach’s α of 0.89 (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001), high test–re-test reliability (0.94) (Zuithoff et al., Reference Zuithoff, Vergouwe, King, Nazareth, van Wezep, Moons and Geerlings2010), and good construct validity (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Rief, Klaiberg and Braehler2006). Scores ≥10 have a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 88% for major depression (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001). This measure has a clinical cut-off of 10 (Manea et al., Reference Manea, Gilbody and McMillan2012), with a threshold of 20 for severe depression (Kroenke and Spitzer, Reference Kroenke and Spitzer2002).

Generalised Anxiety Disorder scale

(GAD-7), administered weekly to assess symptoms of general anxiety. The GAD-7 has good ‘criterion, construct, factorial and procedural validity’ (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe2006, p. 1092), good internal reliability (α = 0.93) (Mills et al., Reference Mills, Fox, Malcarne, Roesch, Champagne and Sadler2014) and good re-test reliability (intra-class correlation = 0.83) (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe2006). GAD-7 has cut-off scores of 5 for mild anxiety, 10 for moderate anxiety and 15 for severe anxiety, with a cut-off score of 10 when screening for anxiety disorders (Williams, Reference Williams2014), although the NHS (2018) advocate a clinical cut-off of 8.

Risk

Risk was assessed throughout the therapy process. Ray reported historic suicidal ideation, which was explored during the initial assessment. Specific questions were asked about his mood, goals and readiness for therapy, his current circumstances and risk of harm to himself or others. Ray openly shared that while suicide felt like an option that would enable him to escape his difficulties, he stressed that his prior attempt many years ago confirmed to him that he would not want to try and harm himself again. Ray’s mood was checked every session, following completion of PHQ-9 measures, and Ray shared on two occasions (sessions 10 and 21) that he was experiencing increased suicidal ideation linked to overwhelming stress caused by an unexpected PIPFootnote 3 re-assessment. Risk was assessed continuously and time was spent working on a safety plan, problem-solving potential barriers to keeping safe and identifying helpful ways for Ray to openly communicate with his partner and best friend. Contact was made with the wider multi-disciplinary team, including Ray’s GP, the service manager and trainee psychologist’s clinical supervisor, and a referral was made to a psychiatrist, with Ray’s consent.

Assessment

Ray completed one intake assessment with a member of the team prior to being placed on the therapy waiting list, during which he completed the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 measures. He completed these measures again 1 week prior to the first assessment session, and weekly thereafter. A further two structured assessments took place, to explore Ray’s difficulties and to assess if anything had changed during the 6-month waiting list. Ray identified the key problems as: anxiety and low mood linked to thoughts and memories of childhood abuse. Ray identified the following goals:

(i) Reduce anxiety;

(ii) Improve mood;

(iii) Make sense of past experiences to understand how they affect current thoughts and behaviour.

The assessment also identified a number of strengths that helped Ray manage difficulties over the previous 30 years, including: his ability to form and maintain positive and supportive close relationships, his willingness to engage with services, his desire to forge a positive future, and his engagement in self-care activities that had a positive impact on his mood.

During the assessment Ray explained that he sometimes forgets things. He attributed occasional memory difficulties to poor sleep and anxiety, noticing that his memory improves when he is well-rested and less stressed. The assessment indicated that memory difficulties were mild and there was no evidence or worry about cognitive decline. Following a discussion about Ray’s memory in the assessment session, and during clinical supervision, it was not deemed necessary to undertake further neurocognitive assessments.

Formulation

Using a case formulation approach, Johnstone and Dallos’ (Reference Johnstone and Dallos2014) 5Ps formulation was developed through collaborative discussion with Ray. This sought to identify the factors that made Ray vulnerable to his difficulties (i.e. various challenging and traumatic early life experiences, an absence of warm and secure early relationships, and managing mixed messages from others); factors that triggered difficulties (including stress, pressure, health issues and social situations), factors that maintained the problem (e.g. stressful situations, time deadlines, focusing on ‘shoulds’, and avoidance); factors that helped Ray to manage daily life (including good relationships with his partner and friend, pleasurable hobbies and self-care activities); and core beliefs (Beck, Reference Beck2011) that developed over time in response to challenging life experiences (including beliefs that the world is a dangerous place, others cannot be trusted and, in relation to self, beliefs that ‘I need to fight back but I need to keep quiet to stay safe’ and ‘I need to block out and ignore wrongdoings by others’ (as illustrated in Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Diagram of Ray’s 5Ps formulation (Johnstone and Dallos, Reference Johnstone and Dallos2014) and core beliefs.

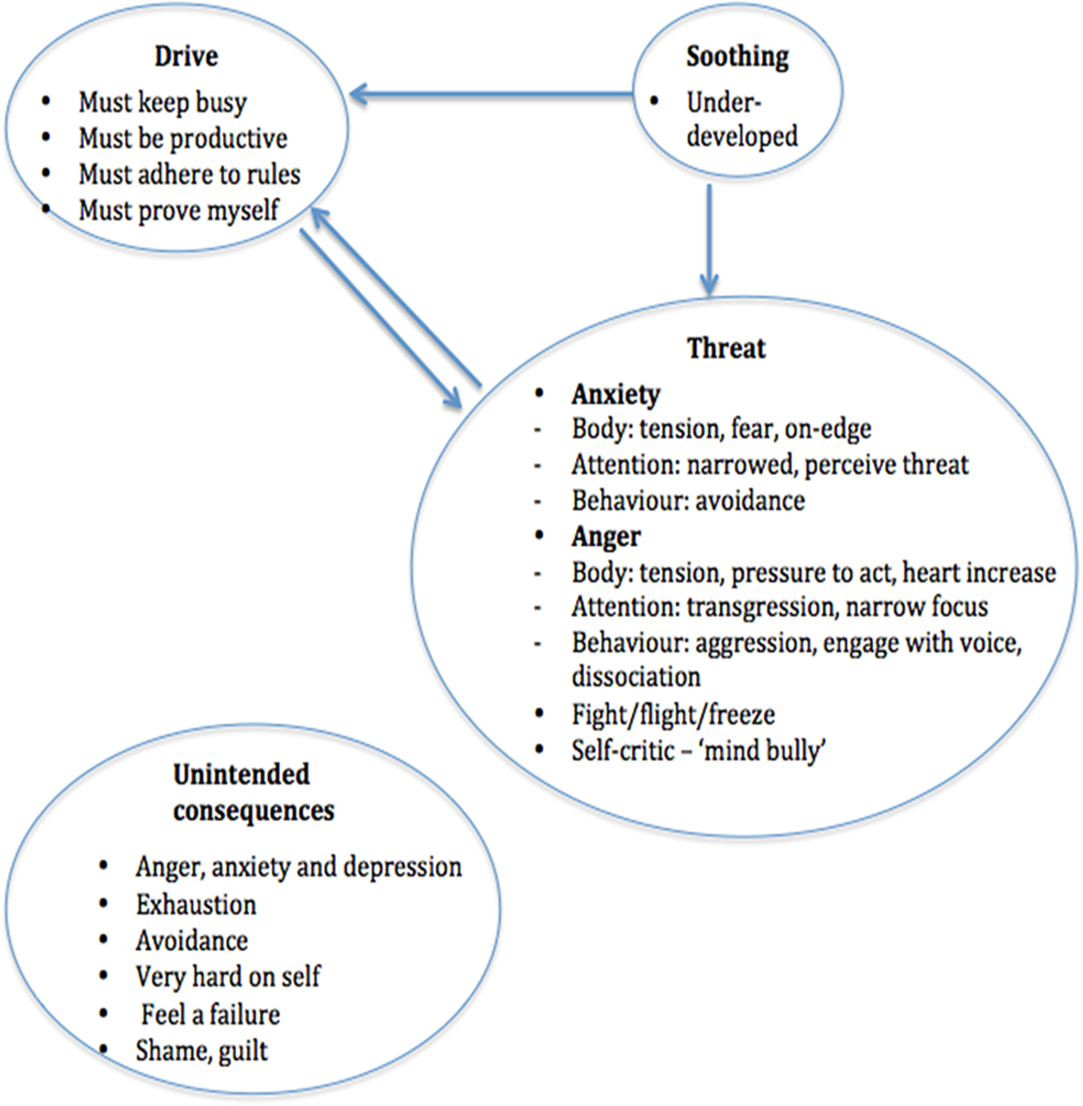

A compassion-focused formulation (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2010) was also developed with Ray, which identified that Ray’s threat system, which focuses on threat detection and protection, was most active and contributed to increased anxiety (see Fig. 2). His drive system was activated when threatened by self-initiated pressure to ‘do’, ‘accomplish’ and ‘achieve’, even when not feeling physically or mentally well enough to accomplish unrealistic tasks. Through psycho-education and collaborative discussion, Ray identified that his soothing system was under-activated, due to having limited opportunities to effectively manage distress, and feel safe and secure. Ray identified that his inner-critic maintained focus on the threat system, which required regulation of threat-focused emotion (Ashworth et al., Reference Ashworth, Gracey and Gilbert2011).

Figure 2. Diagram of CFT formulation (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2010) of Ray’s emotion regulation systems.

Hypotheses

It was initially hypothesised that a case formulation-driven approach that draws on the theoretical underpinnings of CBT would improve Ray’s symptoms of anxiety and depression. It was further hypothesised that incorporating CFT would augment the intervention as promoting the development of self-compassion would help Ray to manage his self-critic (Pauley and McPherson, Reference Pauley and McPherson2010), which had a negative impact on his mood and anxiety.

Intervention

During the intake assessment, Ray was offered the choice of group or individual therapy, and was informed that the service offered various interventions including CBT, trauma-focused therapy, mindfulness, etc. Although it became apparent during the assessment that trauma-focused work would be suitable, Ray specifically wanted to focus on the ‘here and now’ and expressed a desire to learn tools to help him manage current anxiety and depression rather than ‘open up old wounds’. He explained that he had addressed the past in previous therapy and indicated a preference for CBT, which adhered to NICE guidance for depression and anxiety (NICE, 2018, 2019), albeit in the context of trauma. The therapist was mindful of the value of respecting Ray’s needs and wishes.

Ray engaged in 28 1-hour treatment sessions. A CBT approach was initially used to collaboratively map the interaction between Ray’s thoughts, feelings and behaviour from a recent distressing incident. This helped to socialise Ray to the model (Padesky and Mooney, Reference Padesky and Mooney1990). Ray completed 10 CBT sessions in the first phase of therapy and 11 CBT sessions in the third phase of therapy, with an interlude of seven CFT sessions, which were driven by the case formulation approach being used (Persons, Reference Persons2005), (refer to overview of intervention in Table 1).

Table 1. Overview of CBT intervention

The first phase of therapy focused on anxiety management (Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, Asnaani, Vonk, Sawyer and Fang2013); exploring Ray’s stress bucket (Carver et al., Reference Carver, Scheier and Weintraub1989) as Ray was experiencing high levels of stress related to his health and benefits re-assessment; rating emotions using visual analogue scales (VAS) (Aitken, Reference Aitken1969); practising grounding techniques (Kennerley, Reference Kennerley2000) to help Ray focus on the here and now when his cognitions about the world not being safe took his attention to past traumatic experiences; behavioural experiments (Rouf et al., Reference Rouf, Fennell, Westbrook, Cooper, Bennett-Levy, Bennett-Levy, Butler, Fennell, Hackmann, Mueller and Westbrook2004), e.g. alternating behaviours on different days to permit time for hobbies that Ray found therapeutic, scheduling a ‘worry slot’ (Hoyer et al., Reference Hoyer, Beesdo, Gloster, Runge, Höfler and Becker2009) to help manage the ‘shoulds’ that perpetuated Ray’s anxiety and low mood; managing the ‘mind bully’ (Vivyan, Reference Vivyan2014) and responding to the ‘poisoned/pesky parrot’ (Vivyan, Reference Vivyan2010), which Ray linked to his critical family member and likened this critical voice to his school bullying experiences. These techniques equipped Ray with skills to manage anxiety and low mood. This phase of therapy also included mapping a timeline (Pifalo, Reference Pifalo2011) of Ray’s experiences to help explore thoughts, feelings and behaviours linked to Ray’s past experiences.

It became apparent during the first phase of therapy that Ray’s ‘inner critic’ (Lawrence and Lee, Reference Lawrence and Lee2014) was significantly hindering his engagement with CBT. For example, Ray shared that he was placing additional pressure on himself when trying to engage in CBT tasks; this was informed by various ‘shoulds’, and unrealistically high expectations of mastering techniques and practising techniques when he felt physically and mentally exhausted. Ray, understandably, described this as stressful. He became frustrated when trying to manage his anxiety when out in the community; he noticed that he was admonishing himself for being stupid when he was distracted while practising grounding techniques; he judged himself for not containing worry to the worry slot; and he found himself engaging with the mind bully by arguing back and then getting angry and upset.

Through collaborative discussion with Ray, moving to a compassion-focused approach (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2010) was deemed necessary. This involved psycho-education on the threat, drive and soothing emotion regulation systems (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2014). Ray was very interested in the theory underpinning CFT and said he related to the threat and drive systems, acknowledging that his soothing system was neglected as he felt self-care equated to laziness. Ray found soothing rhythm breathing (Welford, Reference Welford2010) calming and he engaged well with compassionate letter writing (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2009), which was designed to help Ray shift from his threat to soothing system.

An unwanted stressful event (Schermuly-Haupt et al., Reference Schermuly-Haupt, Linden and Rush2018), i.e. an unexpected re-assessment of Ray’s PIP benefits, arose during the course of therapy. As research indicates, such events can, and did, cause significant distress (Glickman et al., Reference Glickman, Tanaka and Chan1991) that required further therapeutic intervention. Guided by research, which suggests that increased therapy duration is associated with better outcomes for older adults (e.g. Pinquart and Sorensen, Reference Pinquart and Sorensen2001; Satre et al., Reference Satre, Knight and David2006), it was decided during a collaborative review that further sessions were required. Ray identified a need to focus on stress management, address poor sleep and improve self-care. The third phase of therapy therefore returned to CBT-focused anxiety management, psycho-education (Whitworth, Reference Whitworth2016) on understanding and managing stress and sleep hygiene (Stepanski and Wyatt, Reference Stepanski and Wyatt2003) and self-care (Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Sturt and Hearnshaw2002).

Homework was also an important part of Ray’s intervention and problem solving took place to identify any barriers to compliance, which is linked with effective outcomes (Mausbech et al., Reference Mausbech, Moore, Roesch, Cardenas and Patterson2010). Although Ray did not have fond memories of school and could potentially have been triggered by an intervention that requires homework completion, he was engaged in the therapeutic process and complied with homework tasks. He described being interested in learning and practising tools to help manage anxiety, and he was motivated to improve the quality of his life. As advised by Cox and D’Oyley (Reference Cox and D’Oyley2011) when undertaking CBT with older adults, memory aids were incorporated and session content and homework details were written down, as Ray identified having mild memory difficulties during the assessment.

Outcomes

Ray’s depression, as measured by the PHQ-9 (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001), remained above the clinical cut-off (10) throughout the duration of therapy. Scores remained stable at the severe level (>20) during the four baseline assessments (A) but increased in the second intervention session (23), which Ray attributed to feeling low when thinking about his past and feeling worried about ‘opening up old wounds’. Scores reduced to below the threshold for severe depression during the first phase of the (CBT) intervention (as illustrated in Fig. 3). The lowest PHQ-9 scores (16) were seen during the CFT part of the intervention although scores fluctuated and rapidly escalated to above the threshold for severe depression in week 18 only, when Ray was notified of his PIP benefit re-assessment, which caused significant distress. Scores fluctuated in the final phase of the (CBT) intervention, but remained below the severe depression threshold. PHQ-9 data were not obtained in sessions 10 and 20, as Ray’s request not to complete the measures was granted and his autonomy was respected (Entwistle et al., Reference Entwistle, Carter, Cribb and McCaffery2010).

Figure 3. Graph of Ray’s depression and anxiety scores over time. Data points are missing for weeks 10 and 20 when Ray requested not to complete outcome measures.

Ray’s anxiety, as measured by the GAD-7 scale (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe2006), remained above the threshold for severe anxiety (15) during the baseline assessments (A) and the first 7 weeks of the (CBT) intervention (B). Anxiety scores reduced to below the severe threshold (<15) during the CFT phase of the intervention, with the exception of week 13 (16). Anxiety scores increased then fluctuated (14–17) during the final (CBT) phase of the intervention, which coincided with increased stress linked to Ray’s PIP re-assessment. All GAD-7 scores remained above the clinical cut-off (8) for the duration of therapy.

Discussion

This case study aimed to reduce anxiety and depression in an older adult with a history of complex mental and physical health issues, using a case formulation approach combining CBT with CFT. Findings reveal that depression and anxiety scores decreased and yet fluctuated during the course of the A–B intervention, but were lowest during the CFT phase of the intervention. Although one cannot fully discern whether it was the CFT approach, specifically, or the CBT plus CFT intervention that accounted for reductions in Ray’s depression and anxiety, it is noteworthy that PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores decreased when Ray began to attend to his inner critic (Pauley and McPherson, Reference Pauley and McPherson2010). During this time, he engaged with compassionate thinking and practised strategies such as rhythm breathing (Welford, Reference Welford2010) that helped him regulate his threat system and increase capacity for soothing (Braehler et al., Reference Braehler, Gumley, Harper, Wallace, Norrie and Gilbert2012; Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2009). This supports the work of Fiske et al. (Reference Fiske, Wetherall and Gatz2009), who argue that self-critical thinking plays a role in exacerbating and maintaining low mood, and Collins et al. (Reference Collins, Gilligan and Poz2018), who advocate CFT for older adults. Development of the affiliative soothing system may be a potential mechanism of change (Teachman et al., Reference Teachman, Beadel, Steinman, Emmelkamp and Ehlring2014). Ray reported how helpful it was to develop a toolbox of techniques to help him cope better, which included techniques learned during both CBT and CFT interventions.

Qualitative feedback from Ray indicated that the intervention had been beneficial. Ray found the STOPP technique particularly helpful, as it provided an opportunity to pause and notice what was happening during stressful situations. The most effective strategy, he believed, was responding to the shoulds/musts/oughts of the poisoned parrot (i.e. his inner critic), which had unrealistically high standards, thus perpetuating the pressure and stress that Ray experienced. Ray reported how helpful and normalising it was to learn about the threat, drive and soothing systems and understand how these were shaped by his early experiences. Realisation that self-care and self-compassion did not equate to laziness, which others have also experienced with CFT (Asano and Shimizu, Reference Asano and Shimizu2018), was of central importance in this case. Ray previously worried that others would think he was lazy; this was a narrative perpetuated in his formative years when he struggled at school. In accordance with literature that indicates that CFT is a promising intervention for highly self-critical individuals with mood disorders (Leaviss and Uttley, Reference Leaviss and Uttley2015), Ray noticed improved mood and reduced anxiety when he engaged in self-compassion. He also noticed increased productivity. This provided the evidence he needed that it was acceptable to practise self-compassion. Ray also stated that therapy had helped him to ‘metaphorically file family [incidents] that previously caused anger’, and he asserted that therapy had ‘re-balanced the [perceived] power inequality’ with family members. Finally, he reported being ‘more hopeful for a positive future’ and said he would continue to practise compassionate thinking as he found it beneficial.

It is noteworthy that emotion regulation difficulties and frustration were more evident in the first CBT phase, which was more cognitively demanding than the CFT phase. Given Ray’s negative experience of school, it is possible that scores were affected by frustration intolerance (Harrington, Reference Harrington2011) or reduced mood related to lower self-efficacy (Bandura, Reference Bandura1997). Tahmassian and Moghadam (Reference Tahmassian and Moghadam2011) acknowledge that perceived sense of efficacy can influence anxiety arousal.

During the first CBT phase, Ray said he knew, logically, what he needed to do but engagement with the CBT techniques was affected by his inner critic, which reinforced feelings of incompetence and self-loathing. As Gilbert (Reference Gilbert2009) denotes, self-criticism is rooted in histories of neglect, abuse, lack of affection and bullying, all of which Ray experienced.

While anxiety and depression scores did reduce during the CFT phase of the intervention, it is important to note that they did not reach subclinical levels, which indicates that persistent moderate–severe depression and anxiety (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001; Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe2006) remained throughout the intervention. This is, perhaps, explained by anxiety and low mood associated with the challenge of revisiting past traumatic events that had occurred over decades, some of which Ray had not spoken about previously.

Scores may also have been affected by issues related to complex health conditions, which Ray found difficult, and which are associated with depression in older adults (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Perry and Strine2005). Positive associations also exist between anxiety and commonly occurring diseases, including the chronic health conditions experienced by Ray (El-Gabalawy et al., Reference El-Gabalawy, Mackenzie, Shooshtari and Sareen2013). Ray’s health conditions affected his daily life, which, in turn, affected his mood. For example, there were occasions where Ray wanted to go out for the day with his partner, but fatigue prevented him from going. Ray noticed his mood dipped when he was not able to accomplish the things he wanted to do. It was not possible to disentangle whether fatigue was associated with depression or Ray’s physical health conditions. As Harvey et al. (Reference Harvey, Wessely, Kuh and Hotopf2009) assert, fatigue and mental health issues frequently occur and share related phenomenological characteristics. Similarly, there is a high prevalence of anxiety and depression among people with chronic lung conditions (Kunik et al., Reference Kunik, Roundy, Veazey, Soucheck, Richardson, Wray and Stanley2005), and breathing difficulties caused by an underlying lung condition could exacerbate emotional distress. For Ray, physical and mental health difficulties were closely interrelated. This case highlights the importance of taking a whole-person perspective (Naylor et al., Reference Naylor, Das, Ross, Honeyman, Thompson and Gilburt2016).

Depression and anxiety were also affected by the unexpected and unwanted PIP benefit re-assessment event (Schermuly-Haupt et al., Reference Schermuly-Haupt, Linden and Rush2018), which Ray found extremely distressing and reported feeling suicidal when fearing an even more difficult future with a reduced income. Ray was not alone in experiencing benefits-related distress, as the move to Universal Credit in the context of government austerity measures has been linked with increased depression, anxiety and suicidality for people with a range of mental and physical health difficulties (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Taylor-Robinson, Stuckler, Loopstra, Reeves and Whitehead2016; Williams, Reference Williams2017).

Finally, findings may also be affected by the relatively short CFT phase of the intervention (seven sessions). In contrast with decades of development of Ray’s self-critic (Lawrence and Lee, Reference Lawrence and Lee2014), commencing with critical inter-personal familial relationships that later became internalised (Vygotsky, Reference Vygotsky1978), it will likely take longer-term self-compassion practice to strengthen affiliative soothing and reduce threat-focused regulation. The findings should, therefore, be interpreted with caution.

Limitations

Limitations include threats to external validity, which are inherent in single-subject designs (Alnahdi, Reference Alnahdi2013); however, a key strength of a single case design is its strong internal validity (Byiers et al., Reference Byiers, Reichle and Symons2014). There is also increased vulnerability to sequence effects in this formulation-driven combined CBT–CFT design (Haines and Baer, Reference Haines and Baer1989). This could have been prevented with a return to baseline as utilised in alternating treatment designs, but this design was neither practical nor ethical to use in this case. When discussing the outcomes of the three phases of the intervention, it is important to consider the possibility of carry-over effects; it is not known whether the reduction in depression and anxiety scores to below the severe threshold in the second phase of the intervention was caused by the CFT approach used or whether outcomes were due to a combination of CBT and CFT. Although the intervention combined CBT and CFT in three sequential phases, it is interesting that depression and anxiety scores increased during the final CBT phase, which might give credence to the view that CFT was beneficial in alleviating self-reported depression and anxiety.

Further limitations pertain to possible sources of measurement error, including potential social desirability or acquiescence bias, as Ray was keen to co-operate and see improvements in his self-rated scores. Notwithstanding, Ray did not acquiesce and was able to articulate when he did not want to complete outcome measures (hence the missing data in weeks 10 and 21). Other potential sources of measurement error include idiosyncratic transient factors, such as the effect of mood and pain (Viswanathan, Reference Viswanathan2005). Additional limitations include collecting baseline data during the assessment phase. It is possible that baseline scores may be affected by rapport built during the assessment sessions or by very brief socialisation to the intervention, which could have impacted on the outcome. Moreover, outcome measures were not collected in all sessions; there were two sessions when Ray felt too distressed to complete them. It is not known how these data would have affected the validity of the findings (Resnik et al., Reference Resnik, Liu, Hart and Mor2008), although acknowledging Ray’s choice and promoting autonomy in therapy sessions was beneficial in enhancing the therapeutic relationship (Entwistle et al., Reference Entwistle, Carter, Cribb and McCaffery2010). Additional limitations include the absence of follow-up data due to the therapist leaving the service; these data would have indicated longer-term change and would have increased study validity (von Allmen et al., Reference von Allmen, Weiss, Tevaearai, Kuemmerli, Tinner and Carrel2015). In addition, the impact of medication taken for multi-morbid physical and mental health conditions was not known. Each medicine has potential side-effects that could have impacted on physical and mental well-being, sleep and memory, etc. Although Ray’s memory difficulties were considered to be mild, in the absence of neuropsychological testing, it was not possible to assess the impact of memory difficulties on Ray’s ability to respond effectively to challenges.

Reflections

This work highlighted the value of using a case-formulation driven approach (Persons, Reference Persons2005), which permitted planning and modifying treatment based on collaborative decision-making, in order to best meet Ray’s therapeutic needs. It was inordinately helpful to be given the opportunity to extend the duration of therapy when it became apparent during a review session that Ray would benefit from a phase of CFT, and then a further phase of CBT when stressful external events necessitated further anxiety management. As a trainee clinical psychologist, the author was perhaps less affected by service and resource constraints that might otherwise have restricted the duration of Ray’s therapy.

Ray was extremely thankful that he had the opportunity to develop a more compassionate way of thinking and to learn various tools to help him manage his difficulties better. Although anxiety and depression scores remained in the clinical range, Ray’s qualitative feedback indicated that combined CBT and CFT had been beneficial for him. One might question how much weight therapists should attribute to outcome measures compared with qualitative accounts of service users’ experiences. In this case, Ray benefited from the flexibility he was afforded by the therapist working with him for as long as he needed, which has implications for therapists wanting to meet the needs of individuals in the context of working in a resource-limited NHS.

In this case, a range of techniques were used in the CBT and CFT phases of the intervention. The trainee psychologist was keen to meet Ray’s expectations of wanting to learn a variety of techniques to help him manage his anxiety and low mood but, on reflection, it may have been beneficial to focus on fewer techniques and allow more time for them to be applied more consistently. This could, perhaps, have reduced the pressure and frustration Ray experienced in wanting to master the CBT techniques in the first phase of the intervention.

This work emphasised the value of psycho-education; it was especially helpful for Ray, who explained that he likes to ‘understand the science behind things’ to fully appreciate them. Psycho-education helped Ray to further his knowledge regarding stress and sleep hygiene in the CBT phases and understand the ‘tricky brain’, emotional regulation and the value of soothing systems in the CFT phase (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2010). Ray was open in sharing difficulties he had with his memory and with reading, so it was relatively easy to use strategies such as memory aids and written instructions to help with homework tasks (Cox and D’Oyley, Reference Cox and D’Oyley2011). This emphasised the importance of checking what specific needs future service users may have, and never assuming that adaptations do not need to be made.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Ray (pseudonym) for his consent to the publication of this article. Thanks also to Dr Anna Strudwick for providing feedback on an earlier draft of this article.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

The author has no conflicts of interest with respect to this publication.

Ethical standards

All procedures contributing to this work comply with the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS.

Key practice points

(1) Increased stigma and shame about mental health difficulties may prevent older people from seeking help; interventions that attend to shame reduction (e.g. CFT) may be useful for this population.

(2) This case study has clinical implications for working with older adults with multi-morbid physical and mental health conditions. Case formulation-driven approaches coupled with flexibility in therapeutic intervention may be required to best meet the needs of service users.

(3) This case highlights the value in drawing on a compassion-focused model in conjunction with traditional CBT. Although anxiety and depression scores did not reach subclinical levels (in the context of an ongoing stressful PIP assessment), they did reduce below the threshold for severe anxiety and depression, particularly during the CFT phase of the intervention.

(4) Older adults may present to mental health services with co-morbid mental and physical health conditions that may affect therapeutic engagement. Adaptations may need to be made, e.g. writing notes to aid memory difficulties.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.