Introduction

NHS Education for Scotland (NES) is an education and training body and a special health board for Scotland’s NHS and partnership staff, with responsibility for developing and delivering education and training for the healthcare workforce in Scotland. NES Psychology Directorate has responsibility for commissioning pre-registration training for clinical and applied psychology for NHS Scotland. Through partnership working with NHS Boards and Universities, we have been involved in ensuring that training pathways reflect changing service needs. NES has been directed to work in partnership with Scottish Government, the Scottish Social Services Council, NHS Boards and other key stakeholders to increase the capacity within the current workforce to deliver evidence-based psychological interventions.

The directorate plays a leading role in developing NES educational strategy to support increased availability of psychological interventions and therapies and supporting the development of the implementation infrastructure to support this. Supervision is a key element of this, as articulated in our guidance document ‘The Matrix: A guide to delivering evidence-based psychological therapies in Scotland’ (NES, 2015). We were a key partner in the development of Roth and Pilling’s (Reference Roth and Pilling2008) recommendation to provide training in both generic (demonstrable competencies common to many evidence-based psychological therapies) and modality-specific supervision competencies [e.g. cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)]. Ferguson et al. (Reference Ferguson, Harper, Platz, Sloan and Smith2016) describe the NES Training in Generic Supervision Competencies for Psychological Therapies (GSC) and the conceptualisation of this NES Specialist Supervision Training for CBT (NESSST-CBT) evaluated here (see also NES Psychology Clinical Supervision webpages). NES also offer a CBT Supervision training programme for staff working in child-based settings (CBT Supervision for CAMHS), which is beyond the scope of this paper. Significant organisational and resource commitment has been required to sustain the Supervision training programmes year on year, including leadership, administration and teaching expertise, as well as a training budget for catering and facilitator fees.

Ferguson et al. (Reference Ferguson, Harper, Platz, Sloan and Smith2016) outlined the aims of NESSST-CBT as being to help delegates identify their own CBT supervision competencies, to review models and expectations of CBT supervision, to increase confidence and skills in using the Cognitive Therapy Scale Revised (CTS-R; Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Baker, Standart, Garland and Reichelt2001) and the Supervision Adherence and Guidance Evaluation (SAGE; Milne, 2017; Milne et al., Reference Milne, Reiser, Cliffe and Raine2011; Milne and Reiser, Reference Milne, Reiser, Watkins and Milne2014), and to be able to adapt and problem solve in CBT supervision scenarios. In addition, several key implementation challenges were identified by Ferguson et al. (Reference Ferguson, Harper, Platz, Sloan and Smith2016), including the challenge of utilising digital platforms and effectively utilising a blended learning approach, tensions around the normative, and formative use of the CTS-R, and the wider issue of supervision as a whole being given equitable status or importance in comparison with direct therapeutic work.

Ferguson et al. (Reference Ferguson, Harper, Platz, Sloan and Smith2016) also proposed evaluating NESSST-CBT with reference to Kirkpatrick’s (Reference Kirkpatrick, Craig and Bittel1967, Reference Kirkpatrick, Craig and Bittle1987) four-stage framework for evaluating the impact of training. The first level, ‘Reaction’, describes the extent to which delegates experience a training as enjoyable, engaging, relevant and of interest to them in their work. Level 2, ‘Learning’, seeks to understand how the training shapes their views and how they imagine using it in their workplace. Level 3, ‘Behaviour’, assesses how much delegates actually change their routine practice. Finally, Level 4, ‘Results’, describes the broader impact on the service and its clients. Kirkpatrick’s model is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Kirkpatrick’s Training Impact Evaluation model (Reference Kirkpatrick, Craig and Bittel1967, Reference Kirkpatrick, Craig and Bittle1987).

Aims

This paper aims to evaluate the impact of 4 years of delivery of NESSST-CBT, from November 2014 to November 2018, using Kirkpatrick’s model reflexively to explore some of the key challenges foreseen by Ferguson et al. (Reference Ferguson, Harper, Platz, Sloan and Smith2016) and how NES is engaging with these challenges into the future.

Method

Participants

Three hundred and ninety-two NHS Scotland Applied Psychological Therapists attended the NES Specialist Supervision in CBT Face to Face training course between November 2014 and November 2018. Of these, 282 participants had completed the additional pre-course e-learning module, and 241 had completed the post-course e-learning module. Two hundred and thirty-six participants had completed all three components. See Table 1 for details of attendance. Ethical approval was not sought, as this project was deemed to be an evaluation of training and not hypothesis-driven research. Delegates were informed of their rights under data protection regulations prior to the start of the training.

Table 1. Professional background and location of CBT Supervision course delegates (2014–2018)

Course overview and materials

Course application

The CBT Supervision course flyer was circulated by email throughout Scotland, via Board Psychological Therapy Training Coordinators (PTTCs) and heads of service. Course applications were screened by NES Psychology staff, namely the CBT Tutor and the Head of Programme for Supervision. Minimum course requirements included previous attendance at the NES Generic Supervision Course (or equivalent), at least 2 years experience of CBT Supervision, a qualification to deliver CBT (typically DClinPsy or CBT Diploma), and managerial approval to deliver CBT supervision.

Pre-face-to-face learning phase

Successful delegates were emailed with instructions to complete a pre-course e-learning module before attending a 1-day face-to-face teaching course. All e-learning modules were hosted on a learning platform and were assigned to delegates via the NES course administrators. The suite of supervision e-modules were not publicly available.

Face-to-face course

The 1-day face-to-face course was facilitated by one or two facilitators (with two regarded as optimum) who were experienced with the course content and clinical supervision of CBT practice. The course consisted of a combination of teaching methods including didactic teaching, slide shows, video demonstrations (including supervision scenarios developed by Derek Milne and Rob Dudley from the University of Newcastle, and Sean Harper from NHS Scotland), role-play exercises in small groups, and wider group discussions. The two main course tools included: (1) Supervision Adherence and Guidance Evaluation (Milne et al., Reference Milne, Reiser, Cliffe and Raine2011), a 22-item instrument for assessing objective supervisory competence, or for use as a subjective self-reflective tool, and (2) the CTS-R Scale (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Baker, Standart, Garland and Reichelt2001), and associated CTS-R Manual (James et al., Reference James, Blackburn and Reichelt2001), a 12-item instrument for measuring CBT competency, with each item rated on a scale of 0 to 6, where 0 is incompetent/absent and 6 is considered expert. Additional teaching material included the Suitability for Cognitive Therapy (Safran et al., Reference Safran, Segal and Vallis1993), a 10-point instrument which provides a guide for measuring client suitability for therapy, with each item measured on a 0 (not rated) to 5 (very suitable for CBT) scale. Delegates were given a spiral bound NES CBT Supervision Manual to support learning and this housed copies of the tools, slides and delegate feedback measure.

Post-face-to-face training phase

After the 1-day course, delegates were emailed by the course administrators and instructed to complete two further e-learning modules. The first post-course e-learning module included a series of videos and multiple-choice questions (essential to pass the course). The second post-course e-learning module consisted of a therapy video for delegates to practise and reflect upon their administration of the CTS-R (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Baker, Standart, Garland and Reichelt2001).

Measures

The Training Acceptability Rating Scale (TARS; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Rawana and Capponi1989) questionnaire was administered at the beginning and end of the training day. This tool assesses delegate satisfaction using a 6-point Likert scale (from 1 = strongly disagree, to 6 = strongly agree) for items entitled: general acceptability, perceived effectiveness, negative side-effects, appropriateness, consistency and social validity of the content of the training. In addition, a further section assesses the teaching process on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = ‘not at all’, to 3 = ‘a great deal’). NES augmented the TARS with 4-point Likert scale questions (0 = ‘not at all’, to 3 = ‘a great deal’) regarding: how competent and confident they felt in terms of their general supervision skills, CBT specific supervision skills, use of the CTS-R and perceived importance of the CTS-R. Additionally, qualitative questions invited the delegates to comment on what they felt about the e-learning modules, the least and most useful aspects of the training, what they felt they had learned, and to provide any other additional comments. Delegates were also asked to self-assess their performance on the Roth and Pilling CBT Specific Supervision competencies, namely their abilities to: draw on knowledge and principles of CBT, identify their supervisees current knowledge of CBT, structure CBT supervision sessions, develop and apply specific CBT knowledge, use a range of supervisory techniques, and to monitor the work of the supervisee. These data were rated on a 4-point Likert scale: ‘Strong’, ‘Comfortable/OK’, ‘Requires Further Development’ and ‘Unsure’. Finally, delegates were sent an automated email 3 months after the face-to-face training to assess their implementation of skills taught on the course. Questions included: frequency of usage, intended plans to use, barriers of usage, and nature of use, of both the CTS-R (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Baker, Standart, Garland and Reichelt2001) and the SAGE (Milne et al., Reference Milne, Reiser, Cliffe and Raine2011) instruments.

Results

Statistical analysis employed SPSS 22.0. The data were inspected for normality and mean values were compared using paired sample t-tests (for pre–post comparisons). Bonferroni corrected significance level (alpha/number of tests) was employed (p < 0.001). Qualitative data were themed using a thematic analysis methodology (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006).

Kirkpatrick’s Levels 1 and 2 (Reaction and Learning)

Training Acceptability Rating Scale

The mean ‘Content’ score at post-face-to-face was 90.01 (SD = 0.94). The process sub-scale was pro-rated as several items from the original TARS were not administered. The pro-rated TARS ‘process’ score was 82.46 (SD = 0.66). The combined overall TARS score was 86.28 (SD = 0.80). Scores above 80 are regarded as good (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Rawana and Capponi1989).

Qualitative feedback

Table 2 below provides a summary of the qualitative data. Superordinate themes located in the data were as follows.

Table 2. Summary of qualitative data

Experiential focus

Many delegates described the role-plays as the most useful part of the training. Other delegates described aspects of engaging with the Competency scales as most useful. Delegates also reported that the video examples of CBT and supervision were the most useful and reported that the discussions generated that linked these components during the day as the most useful aspects of the training.

A reframing of supervision

Many delegates outlined a degree of familiarity with the CTS-R prior to training. However, many described a sense of reinforcement or validation in what they already knew about it. Moreover, when delegates were asked what (if anything) had changed in their practice post-training, many described an increased focus and structure brought into their work. Others outlined a sense of increased openness towards the CTS-R. This seemed to be related to the emphasis placed on the flexible use of the scale. Many delegates related an adoption of a more nuanced view of the CTS-R, its usefulness in bringing structure to CBT Supervision, and the benefits of a flexible and formative use of it.

Limitations and barriers

Delegates did not generally report issues or problems with the training. Of the specific concerns raised, the most frequently occurring issue was a sense of repetition in the training, mainly either with the e-learning module, or with the Generic Supervision Course. A small group reported disliking the role-plays generally. Some delegates commented that the issue of summative use of the CTS-R remained important to them, and that they found engaging with the SAGE more difficult and might require more training in this.

Kirkpatrick’s Levels 2 and 3 (Learning and Behaviour)

Self-assessed supervision competence and confidence

Delegates were asked before and after the face-to-face training to subjectively rate their own subjective sense of how competent and confident they felt in terms of their own general supervision skills, their CBT supervision skills, their use of the CTS-R and how important they felt the CTS-R was. There were no significant differences between post-face-to-face evaluations and at follow-up. Data are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3. Changes in beliefs about supervision at the face-to-face training

Roth and Pilling CBT Supervision competencies

Delegates were asked during the e-modules to subjectively rate their performance on the Roth and Pilling CBT Supervision competencies (Reference Roth and Pilling2008) prior to the face-to-face training, and again after the training. These competencies are the abilities to: draw on the knowledge and principles of CBT, to identify the supervisees’ current knowledge of CBT, to structure CBT supervision sessions, to develop and apply specific CBT knowledge, to use a range of supervisory techniques, and to monitor the supervisees’ work. The data responses were in the form: Strong, Comfortable, OK, and Requires Further Development. A further option ‘Unsure’ was removed from the analysis due to its ambiguity. Data are displayed in Table 4.

Table 4. Changes in beliefs about CBT and supervision competencies in the e-modules

Discussion

This project is a retrospective evaluation of feedback data and not a randomised controlled trial which limits causal attribution. However, the large sample size and moderate to large effect sizes are strongly suggestive of meaningful and positive learning for Supervisors. The TARS scores, at well above 80% (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Rawana and Capponi1989), indicate that the majority of delegates experienced the training as useful, acceptable, socially valid, consistent with common sense and improving of their understanding and work-related skills. Delegates were particularly positive about the active learning components of the training, for example, the rating of CBT video clips and supervision scenario role-plays in combination with group discussions. These data indicate attainment of Kirkpatrick’s Level 1 of positive ‘Reactions’ to the training delivery package.

The training content aims were to enhance the formative use of the Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale Revised (CTS-R; Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Baker, Standart, Garland and Reichelt2001) and the Supervision Adherence and Guidance Evaluation (SAGE; Milne et al., Reference Milne, Reiser, Cliffe and Raine2011). The results suggest significant positive changes for delegates across a number of generic and CBT specific competencies, suggesting Kirkpatrick’s Level 2 of ‘Knowledge Acquisition’ had taken place. In particular, a moderate to large effect size in increasing delegate confidence in the use of the CTS-R was observed.

While alternative measures to the CTS-R (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Baker, Standart, Garland and Reichelt2001) are introduced at the beginning of the training, the position has been to focus on the CTS-R, as it is the most well-known and researched tool to date. However, the fact remains that the CTS-R (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Baker, Standart, Garland and Reichelt2001) is not the only measure of fidelity to CBT supervisory practice and reviews of other measures have been conducted elsewhere (Keen and Freeston, Reference Keen and Freeston2008; Muse and McManus, Reference Muse and McManus2013; Roth, Reference Roth2016). Other measures beyond the scope of the training course include: the Cognitive Therapy Competence Scale for Social Phobia (CTCS-SP; von Consbruch et al., Reference von Consbruch, Clark and Stangier2012), and the Cognitive Therapy Adherence and Competence Scale (Barber et al., Reference Barber, Liese and Abrams2006) with several of these newer measures pointing towards the merits of disorder-specific competences being consistently and demonstrably measured and discussed in supervision.

In terms of the Supervision Adherence and Guidance Evaluation (SAGE; Milne et al., Reference Milne, Reiser, Cliffe and Raine2011), a minority of delegates responding to the 3-month follow-up survey had used or planned to use a structured supervision scale such as SAGE. Increased use of SAGE may thus require further consideration by NES, for example, its role within the NESSST-CBT package or in further training separate to NESSST-CBT. SAGE teaching is included in the Generic Supervision course, and the Clinical Supervision Workstream regularly hosts SAGE Masterclasses, facilitated by experts such as one of the SAGE authors, Derek Milne. The NESSST-CBT materials have recently been revised to include the ‘Short SAGE’, with items reduced from 22 to 14 to facilitate easier use by clinicians (Reiser et al., Reference Reiser, Cliffe and Milne2018). Alongside this, NES have introduced clearer, briefer and more consistent tracking of delegates to aid the measuring of ‘Behaviour’ (Kirkpatrick Level 3) rather than confidence, as a more robust measure of impact (Eccles and Mittman, Reference Eccles and Mittman2006).

The data here are self-report, and subjective in nature, suggesting caution in the extent to which one can assume that actual changes in practice have occurred (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Soumerai, Lomas and Ross-Degnan1999). However, there is evidence that confidence positively impacts performance as well as patient experience (Owens and Keller, Reference Owens and Keller2018). Lower data numbers at follow-up (itself not an unusual phenomenon) limited the conclusions to be drawn regarding Kirkpatrick Levels 3 and 4, impact on practice in the workplace, and ultimately the impact on supervisees and patients. However, overall, the data do support the wider aims of NES to deliver a high-quality blended learning format across a large geographical area in support of the majority of the psychological therapies workforce in Scotland. It may be that several variables impact on delegate completion of post-face-to-face activities such as time, resources, use of CTS-Rs in their workplace and motivation to complete the 3-month follow-up questionnaire. To support Level 3 and 4 measurement, triangulation data from trainees who are required to use the CTS-R on placement may be useful.

In addition, it should also be noted that there are some useful critiques of the Kirkpatrick model itself. Reio et al. (Reference Reio, Rocco, Smith and Chang2017) for example, outline that the literature points to only a minority of organisations that successfully measure Kirkpatrick Levels 3 and 4, and that there is limited evidence or elaboration in the model as to how the levels are hierarchically or sequentially linked and how those linkages might support implementation (Reio et al., Reference Reio, Rocco, Smith and Chang2017).

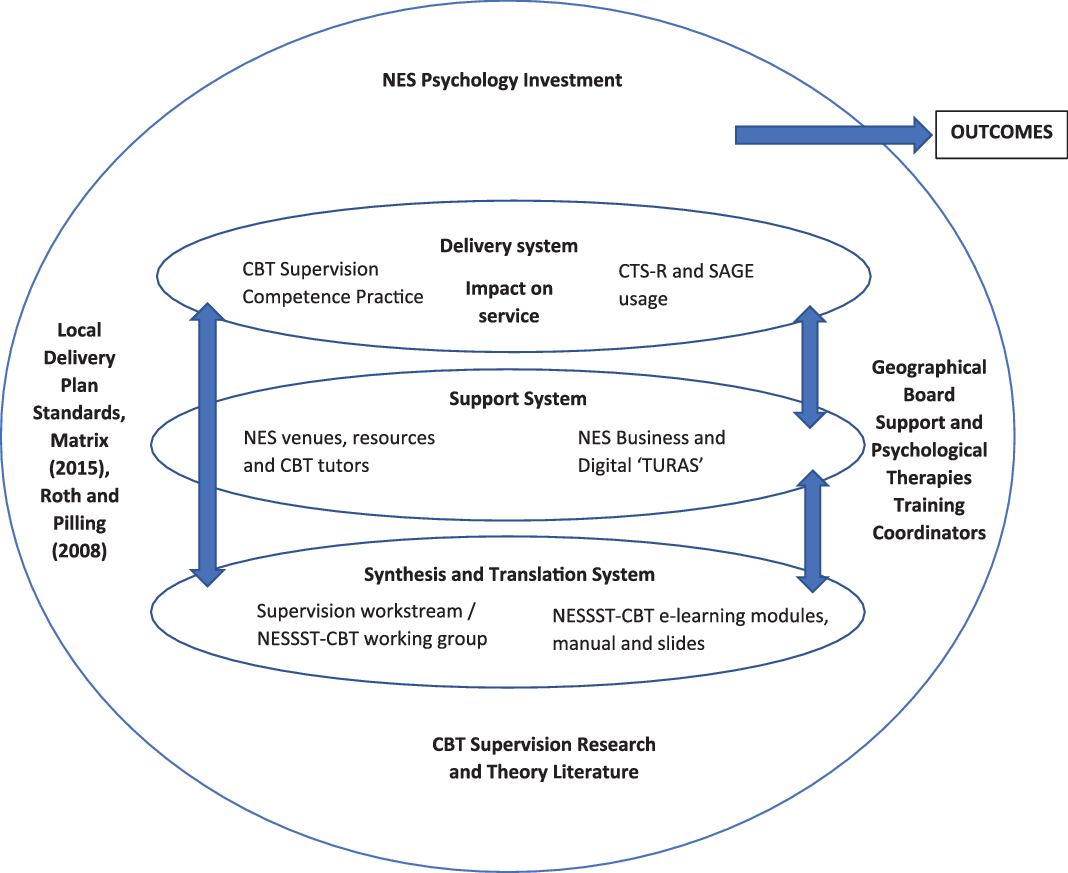

The Interactive Systems Framework (ISF; Wandersman et al., Reference Wandersman, Duffy, Flaspohler, Noonan, Lubell, Stillman, Blachman, Dunville and Saul2008) provides a useful visual aid for summarising and conceptualising the multiple and linked structures necessary for the long-term implementation and delivery of training such as the one discussed in this paper. According to the ISF, training occurs in the context of current literature, policies and wider organisational readiness to resource and adopt a planned innovation. Literature is synthesised and translated into useable training information that is supported by technical, educative, facilitative, digital staffing and material resources. The delivery is then carried out by the staff who receive the training and who go on to develop their confidence and competences in implementing the evidence-based supervision skills in their own work settings (Meyers et al., Reference Meyers, Durlak and Wandersman2012). Figure 2 visualises the interactive systems that constitute NESSST-CBT’s implementation.

Figure 2. The Interactive Systems Framework (Meyers et al., Reference Meyers, Durlak and Wandersman2012) applied to NESSST-CBT. For Local Delivery Plan Standards, see Scottish Government (2012). For details of The Matrix, see NES (2015).

Future directions

The CBT Supervision Manual requires to be periodically updated in order to be consistent with current clinical supervision research and practice. The Manual was last updated in early 2019, as mentioned to include the 14-item Short SAGE (Reiser et al., Reference Reiser, Cliffe and Milne2018), as well as the REACTS Supervisee Feedback measure (Milne et al., Reference Milne, Leck, James, Wilson, Proctor, Ramm, Wilkinson, Weetman, Fleming and Steen2012), in addition to including the REACTS measure (Milne et al., Reference Milne, Leck, James, Wilson, Proctor, Ramm, Wilkinson, Weetman, Fleming and Steen2012) instead of the TARS (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Rawana and Capponi1989) for delegate feedback. There has been recent substantial investment and development in NES digital services. NES are currently undertaking major transformational improvements to their own staff digital platform, and work has begun to situate NESSST-CBT on the TURAS (the Gaelic word for journey) online learning platform, https://turasdashboard.nes.nhs.scot/. This represents a new stage in the NESSST-CBT evolution by reducing the number, complexity and cost of the learning platforms that staff must interact with to progress their continuing professional development needs. This digital learning and appraisal platform is now easily accessed by all Scottish NHS and partnership staff, and provides a career-spanning learning platform to facilitate long-term engagement with the learning materials. It is hoped that the greater use of such an easily accessible platform will drive more consistent, targeted and specific training materials, providing a more nuanced and adaptive continuing professional development for staff. A wider and more consistent use of CBT competence measures, including those with increased disorder specificity, is likely to become more achievable over time as a result.

Limitations

While there was clear evidence that the training course increased perceived confidence and competence in CBT Supervision, there is a lack of direct evidence of the quality and fidelity of CBT supervisory practices throughout the trained workforce, and feedback from supervisees is also lacking. As noted, there are limitations to the reliability of self-report. Nevertheless, we surmise from data obtained that the training programme has to some extent enhanced fidelity to CBT supervisory practice. It is hoped that future research will be able to measure the more difficult to gauge ‘Behaviour’ and ‘Service’ impacts (Kirkpatrick Levels 3 and 4). The systematic delivery, evaluation and updating of this training course requires considerable staffing, financial and digital resources, which may not currently be available in all areas of the UK.

Conclusions

In summary, NES have provided training in the supervision of CBT for the Scottish Psychological Therapies workforce. Overall, the results from this evaluation of 4 years of NESSST-CBT Supervision training demonstrate that the course is well received and that it has been consistently well delivered over time by NES. It has met many of the foreseen challenges offered by delivering training to a widely dispersed workforce and has done so, in a cost-effective way, by utilising the evolving digital leadership provided by NES. This paper has augmented the Ferguson et al. (Reference Ferguson, Harper, Platz, Sloan and Smith2016) original work that set out a blended learning approach to CBT Supervision training in Scotland. Four years on from its initial delivery, NESSST-CBT has trained almost 400 practitioners, and training courses are continued to be offered on a regular basis. The training positively impacts delegates’ knowledge and confidence in providing good supervision of CBT and is part of an evolving system of supervision training delivery provided by NES.

Acknowledgements

We thank colleagues within NES and delegates attending each course. We are very grateful indeed to Derek Milne, Bob Reiser and colleagues for permission to use various materials within the training course. We also give warm thanks to Sean Harper, Shirley Platz, Graham Sloan and Katherine Smith, who assisted with the development and delivery of the course.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

Nathan O’Neill, Mairi Albiston, Sandra Ferguson and Leeanne Nicklas have no conflicts of interest with respect to this publication; however, they all contributed to the development of the course within their NES roles.

Ethical statement

This Education and Supervision article is a review of existing training data and not deemed as research by NES. Ethical approval was therefore not required.

Key practice points

(1) Three hundred and ninety-two delegates completed the NES Specialist Supervision Training in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (NESSST-CBT) between November 2014 and November 2018.

(2) The delivery of NESSST-CBT has occurred in a context of an Interactive Systems Framework and achieved several levels of impact according to Kirkpatrick’s Training Evaluation Model.

(3) Delegates rated the training positively as a learning experience and described increases in their CBT Supervision competencies and confidence in the use of the CTS-R.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.