Introduction

It is widely acknowledged that the psychotherapy professions need to improve the quality of care they provide to service users from minoritised ethnicities (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Naz, Brooks and Jankowska2019; Bignall et al., Reference Bignall, Jeraj, Helsby and Butt2019). While there has recently been much more focus on this area (e.g. Beck, Reference Beck2016; Burnham, Reference Burnham and Krause2012; Watkins and Hook, Reference Watkins and Hook2016) and many white therapists will have made significant efforts to improve their cultural competence, there is substantial evidence of worse outcomes for service users from minoritised ethnicities compared with people categorised as white (Baker, Reference Baker2018; Mercer et al., Reference Mercer, Evans, Turton and Beck2019). Therapists in general should be better able to address issues of racism and related trauma (Beck, Reference Beck2019; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Printz, Ching and Wetterneck2018), but also differences in cultural outlook which will have an impact on the therapeutic process (Fernando, Reference Fernando2010). In this article I will explore how applying a model of therapist skill development could be relevant to improving white therapists’ cultural competence. This is aimed at white therapists because the psychotherapy professions are majority white (Alcock, Reference Alcock2019) and because there is evidence that some, although by no means all, white therapists lack skills in working with service users from minoritised ethnicities (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Owen and Bieschke2015; Imel et al., Reference Imel, Baldwin, Atkins, Owen, Baardseth and Wampold2011; Owen et al., Reference Owen, Imel, Adelson and Rodolfa2012).

In recent years there has been an increasing focus on adapting generic psychological models to assist white therapists to improve their practice with service users from minoritised ethnicities. For instance, Beck (Reference Beck2016; pp. 35–36) suggests that a therapist’s reluctance to raise issues relating to ethnicity can be understood and worked on through a cognitive behavioural model, and Rosen et al. (Reference Rosen, Kanter, Villatte, Skinta, Loudon, Williams, Rosen and Kanter2019) apply an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy framework to this area. One approach to improving therapists’ practice that has not been used in this context before is the Declarative-Procedural-Reflective (DPR) model of therapist skill development (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006). The DPR model is intended to be a generic model of therapist skill development, as applicable to for instance systemic and psychodynamic approaches as to CBT. I will argue that the DPR model could provide a useful conceptual and practical overview of how white therapists can improve their skills with service users from minoritised ethnicities.

Analysing and addressing a lack of cultural competence through the DPR model could be helpful for several reasons. The DPR model is a comprehensive and systematic account of skill development (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006), and I propose that adapting the DPR model to the area of cultural competence clearly identifies the range of specific skills white therapists might be lacking with service users from minoritised ethnicities. This specificity leads to concrete recommendations as to what can be done to address those skills deficits, so applying this model could have a direct positive impact on therapists’ practice. The specificity of the DPR model also leads to hypotheses about which activities will have most impact on therapist skill development (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006; Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2019), so the application of this model to the area of cultural competence generates testable predictions. Finally, the DPR model has a key emphasis on the importance of therapists engaging in reflection about their work with service users (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Chaddock, Davis, Stedmon and Dallos2009). This focus on therapist self-reflection is also seen in the existing literature on cultural safety and cultural humility (Curtis et al., Reference Curtis, Jones, Tipene-Leach, Walker, Loring, Paine and Reid2019; Davis et al., Reference Davis, DeBlaere, Owen, Hook, Rivera, Choe and Placeres2018; Hook et al., Reference Hook, Davis, Owen, Worthington and Utsey2013) and applying the DPR model in this context may provide a helpful perspective which complements the existing knowledge base.

The generic DPR model

Before showing how the DPR model can be adapted to work with service users from minoritised ethnicities I will describe the generic model, drawing on Bennett-Levy (Reference Bennett-Levy2006) unless otherwise stated.

The DPR model is a conceptualisation of skill development relevant to all therapists, no matter what therapeutic model they practise, and irrespective of whether they are at the very beginning of their training or advanced practitioners with a great deal of clinical experience (Thwaites et al., Reference Thwaites, Bennett-Levy, Davis, Chaddock, Whittington and Grey2014). The central proposition of the model is that the areas listed in its title – declarative, procedural and reflective – describe three inter-related systems which, when working together productively, allow therapists to develop their skills.

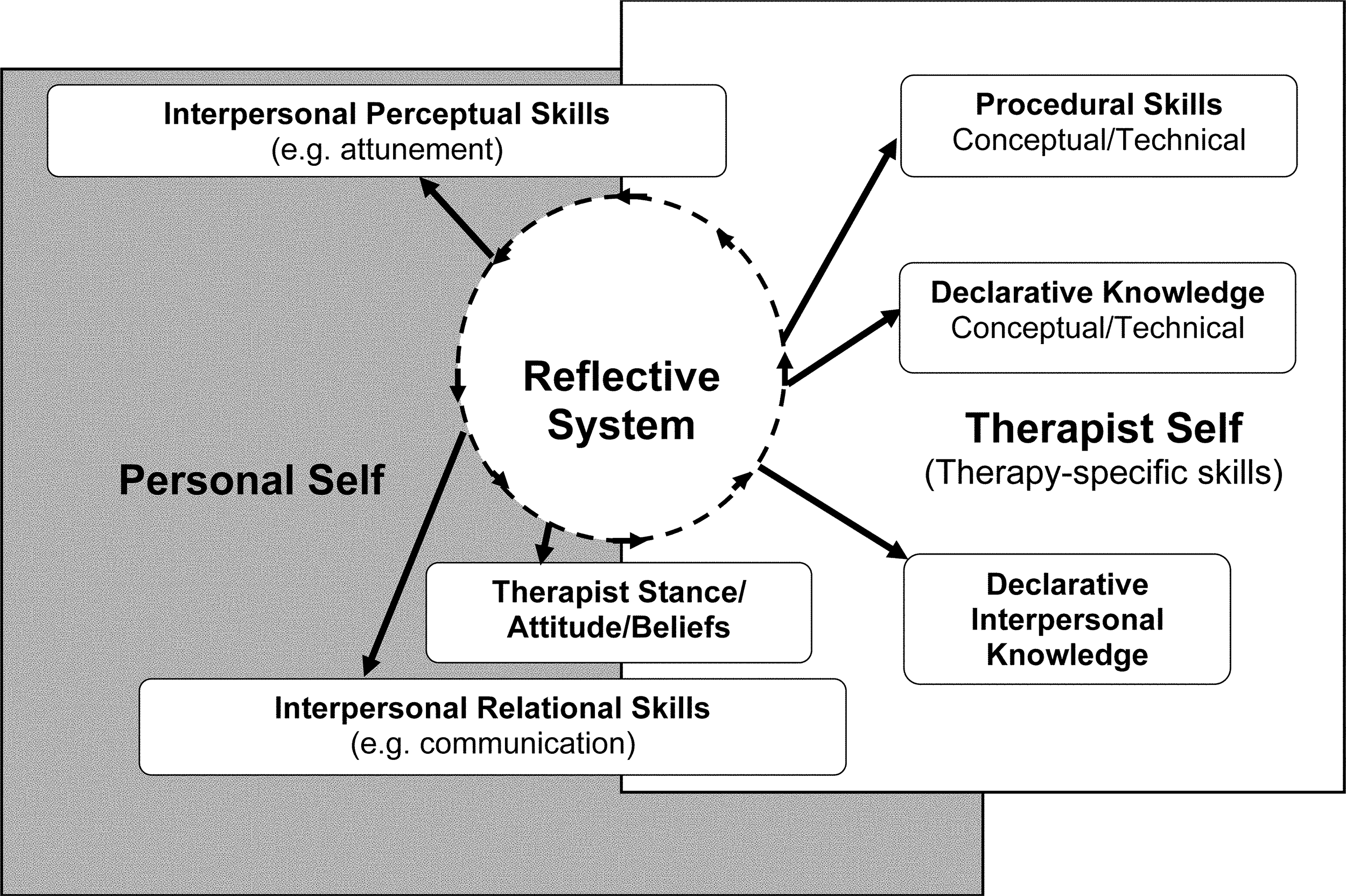

The nature of the declarative, procedural and reflective systems can be quite easily summarised. The declarative memory system holds the conceptual knowledge relevant to the therapy being conducted. It can be described as knowledge of ‘What is…?’ For instance, ‘What is the CBT model of social anxiety?’ or ‘What is circular questioning?’. The procedural skills system relates to the practical skills of therapy, and therefore describes what the therapist actually does when they are working with a service user. It refers to the use of specific therapeutic techniques (e.g. planning a behavioural experiment or conducting an imagery exercise), but also to the interpersonal skills crucial to therapy. The reflective system is what therapists use to think about what they are doing well in therapy, and what they need to improve. Through the reflective system, one updates declarative and procedural knowledge. The reflective system is thought to play a crucial role in further improving therapeutic skills, and as such it has been described as the ‘engine’ of therapist skill development (Bennett-Levy et al., 2009).

The declarative, procedural and reflective systems all inter-relate, and the DPR model proposes that if they work together productively then the therapist will develop their skills. For instance, reflecting on what is not going well in a piece of clinical work might lead to identifying a lack of declarative knowledge (e.g. needing to know more about a particular CBT protocol) or a procedural skill which requires more development (e.g. how to demonstrate empathy to a client with issues of interpersonal trust).

Psychotherapy training develops all three systems identified in the DPR model. Declarative knowledge is transmitted through formats such as didactic lectures and reading books and articles on the therapy in question. Procedural skills are gained through mock-therapy experiences such as role plays, but also simply through practising therapy with service users. Reflective ability is developed through supervision and other experiences such as reflective practice groups. These modes of training all build up what the DPR model describes as the ‘therapist self’, the professional identity people take on as they become therapists. However, equally important in the model is the ‘personal self’ (Bennett-Levy and Haarhoff, Reference Bennett-Levy, Haarhoff and Dimidjian2019). This is made up of ‘the knowledge, attitudes, skills and personal attributes that have mostly been established prior to becoming a therapist’ (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006; p. 65). Therapists-to-be start training with their own interpersonal styles, knowledge and reflective abilities, all of which are derived from and affected by their personal experience up until that point. They will also hold a set of explicit and implicit attitudes and beliefs relevant to therapy, such as the importance of being compassionate towards others. Therapeutic training then elaborates on these abilities and attitudes.

Figure 1 is a schematic representation of the DPR model, showing the inter-relationship between its various components. The boxes entitled ‘interpersonal perceptual skills’ and ‘interpersonal relational skills’ denote the abilities therapists have to build relationships with others which have been developed before therapeutic training; as such they largely sit within the ‘personal self’ part of the representation. The box ‘Therapist Stance/ Attitude/Beliefs’ refers to therapy-relevant aspects of the therapist’s views; it is placed equally within the ‘personal self’ and ‘therapist self’ areas as this comes both from therapeutic training and personal experience.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the DPR model. Figure reproduced from Bennett-Levy et al. (Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Chaddock, Davis, Stedmon and Dallos2009). Republished with permission of McGraw Hill, permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

The DPR model has now been applied in a number of psychotherapeutic contexts (e.g. Cromarty et al., Reference Cromarty, Gallagher and Watson2020; Kuyken et al., Reference Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley2009; Ludgate, Reference Ludgate, Sudak, Codd, Ludgate, Sokol, Fox, Reiser and Milne2016). It has also informed the design of self-practice/self-reflection programmes, which aim to support therapists to better learn clinical skills by applying therapeutic techniques to themselves (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Haarhoff and Perry2015; Farrell and Shaw, Reference Farrell and Shaw2018; Kolts et al., Reference Kolts, Bell, Bennett-Levy and Irons2018). The DPR model does therefore appear to provide a useful conceptualisation of how therapists can improve their skills.

Application of the DPR model to issues of ethnicity, race and racism

Figure 2 shows an adapted version of the generic DPR model. It is based on the hypothesis that there are a number of specific barriers to the development of psychotherapeutic skills with service users from minoritised ethnicities. The nature of these potential barriers will be elaborated on in the following sections.

Figure 2. An adapted version of the generic DPR model. Figure adapted from Bennett-Levy et al. (Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Chaddock, Davis, Stedmon and Dallos2009). Adapted and published with permission of McGraw Hill, permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

Insufficient declarative knowledge

Declarative knowledge is knowledge that can be explicitly stated. It can be described as knowledge of ‘what is…?’. For instance, therapists in training and beyond will learn what is the CBT protocol for a specific disorder, what is cognitive restructuring in CBT, or what is reflexivity in systemic therapy.

It appears that many white therapists may not have had the opportunity to gain enough declarative knowledge about ethnicity-related issues. Beck (Reference Beck2016) describes a range of areas in relation to working with service users from minoritised ethnicities where therapists may have insufficient knowledge, and while his focus is on CBT practitioners this list probably applies to therapists more broadly. He argues that therapists need to develop their knowledge about how to engage service users from minoritised ethnicities, how to discuss and think about cultural difference (e.g. the metaphors used in one culture may not make sense in another), how to formulate, how to intervene, how to measure outcomes, and how to provide supervision. This list covers almost every part of therapeutic practice, and this therefore suggests that therapists need to gain knowledge in every aspect of their work. Given the range of areas listed it is beyond the scope of this article to systematically outline specific deficits in declarative knowledge, so only an overview with some illustrative examples will be provided.

Issues of ethnicity and racism have not historically been given a clear place in therapeutic models. Beck (Reference Beck2019) notes that this is the case for all current major schools of therapy: in CBT disorder-specific formulations have little or no place for social factors such as ethnicity; psychodynamic therapies have not historically given a great deal of consideration to issues of culture; and even in the much more culturally aware world of systemic therapy there has not been sufficient focus on asking service users about when they have experienced racism. All modes of therapy are now giving much more attention to this area (e.g. Naeem, Reference Naeem2019;Journal of Family Therapy, n.d.), but the knowledge base is very much still in a process of development. Therapists in training and beyond are not therefore at present given enough opportunity to develop the necessary declarative knowledge on how to work with people from minoritised ethnicities.

The problems arising from this lack of declarative knowledge are clearly illustrated in the recent literature on how to work with people who have experienced racism. Beck (Reference Beck2019) describes how racism has not received sufficient attention from therapists, and a lack of knowledge about this will have an impact on therapeutic skills in a number of ways. For instance, Pieterse (Reference Pieterse2018) discusses the distinction between racial trauma and other types of trauma. They argue that the trauma which arises from being the victim of racism is quite different from traditional psychological understandings of trauma, as superficially minor incidents such as racial microaggressions can trigger a traumatised reaction. If a therapist is not aware of the potentially different nature of racial trauma they will be less equipped to address this in therapy (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Printz, Ching and Wetterneck2018). With regard to specific interventions for service users from minoritised ethnicities who have experienced racism, therapists probably also need to be much more aware of the necessity of adapting core therapy techniques. For instance, Graham et al. (Reference Graham, Sorenson and Hayes-Skelton2013) detail how cognitive restructuring in CBT needs to be targeted not at any cognitions around whether or not an incident was racially motivated (e.g. was service denied in a shop because of the service user’s ethnicity?), but rather what those incidents mean about the service user (e.g. targeting cognitions linked to internalisation of racism). These examples demonstrate why it is important for therapists to gain more knowledge of how to work with people who have experienced racism, and it seems likely that there will be a variety of other areas where many white therapists will also be lacking the necessary knowledge to work effectively with service users from minoritised ethnicities.

A key issue is not just a general lack of knowledge, but also what knowledge is most important. While the knowledge base is still being developed, there are already many papers, books, and other learning resources in existence (e.g. Beck, Reference Beck2016; Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, Kanter, Villatte, Skinta, Loudon, Williams, Rosen and Kanter2019; Sue et al., Reference Sue, Sue, Neville and Smith2019). The quantity of potentially relevant literature risks overwhelming therapists, and this may mean that they either gain knowledge haphazardly or even disengage entirely. It might for instance be helpful for therapists to know more about the concept of race (Richeson and Sommers, Reference Richeson and Sommers2016), whiteness (Patel and Keval, Reference Patel and Keval2018), white privilege (Halley et al., Reference Halley, Eshleman and Vijaya2011), racial microaggressions (Sue and Spanierman, Reference Sue and Spanierman2020), racial socialisation (Powell-Hopson and Hopson, Reference Powell-Hopson and Hopson1988), incorporating religious beliefs into therapy (Azhar and Varma, Reference Azhar and Varma1995), and racial and cultural identity development models (Sue and Sue, Reference Sue and Sue1999). Although many other concepts could be cited, the extent of this partial list shows the challenges therapists face in integrating cultural competence into their general therapeutic knowledge. White therapists may therefore benefit from guidance on what declarative knowledge is essential for their work with service users from minoritised ethnicities, as the individual therapist will not need to have a grasp of the entire literature on cultural competence and cultural humility. The DPR model provides a helpful approach to prioritising what knowledge to gain, as it emphasises how therapists improve their skills by thinking about what specific declarative knowledge they need for particular service users (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Chaddock, Davis, Stedmon and Dallos2009). Consistent with the existing literature on cultural humility (Curtis et al., Reference Curtis, Jones, Tipene-Leach, Walker, Loring, Paine and Reid2019; Hook et al., Reference Hook, Davis, Owen, Worthington and Utsey2013) this requires an attitude characterised by openness, curiosity and self-reflection, and this point will be covered more fully in the below section on reflection.

One part of the knowledge base which may be lacking for white therapists is the histories of people from minoritised ethnicities. For example, understanding the ‘migration narrative’ of a service user from a minoritised ethnicity can be very important (Falicov, Reference Falicov1995; Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015). This narrative will relate to specific historic events that occurred at the time of the migration which have had an impact on the service user. Without such knowledge, therapists may be less likely to recognise the importance of events service users from minoritised ethnicities have lived through, both in relation to migrations and in their life in general. There is evidence that this aspect of declarative knowledge is not well developed in the CBT field, as in a major recent text on CBT with older adults (Laidlaw, Reference Laidlaw2015), while there is a list of historical events relevant to therapeutic work, there is no reference to events which would have specifically affected minoritised ethnicities.

A lack of knowledge about ethnicity-related issues is of course not unique to psychotherapy but is evident in society in general. The adapted DPR model as shown in Fig. 2 makes direct reference to these systemic factors. It specifies ‘Personal and therapist selves develop against a background of systemic racism and lack of attention to ethnicity-specific issues: these factors impact every area of this model’. This amendment emphasises that deficits in therapist skill do not emerge in a vacuum, but rather are intimately connected to societal forces which have an impact on and perpetuate the factors identified in the DPR model. For instance, a lack of knowledge about the impact of racism is not just the result of deficits in therapist training, but also arises from a lack of proper acknowledgement of ongoing racism in society more broadly (Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2016). Insufficient historical knowledge is the direct result of the failure to properly address the historical experiences of minoritised ethnicities within the broader education system (Arday, Reference Arday2021; Atkinson et al., Reference Atkinson, Bardgett, Budd, Finn, Kissane, Qureshi, Saha, Siblon and Sivasundaram2018).

The hypotheses presented in this section are that white therapists may lack necessary knowledge when working with service users from minoritised ethnicities, but also that they would benefit from guidance on what the most important knowledge is to gain. Table 1 summarises suggestions for how the psychotherapy professions could address these issues.

Table 1. Suggestions for remedial action to address skills deficits

Under-developed procedural skills

In the DPR model the term procedural skills refers to what the therapist practically does when they are carrying out therapy. For instance, a CBT therapist would plan behavioural experiments and a systemic therapist might use their skills of circular questioning. Beyond specific therapeutic techniques, clinicians will also make use of their interpersonal skills, such as the ability to become attuned to a service user’s emotional state and to effectively create a therapeutic relationship. As such, the procedural skills system encompasses all the skills that therapists draw upon when they are carrying out therapy. This section will explore how some white therapists may not have had sufficient opportunity to develop the necessary procedural skills to work effectively with service users from minoritised ethnicities.

A key area where procedural skills may be under-developed is how to address experiences of racism, as already highlighted in the discussion on declarative knowledge. This is likely to have a negative impact on the ability of some white clinicians to work effectively with a service user from a minoritised ethnicity who makes reference to a racist incident. Specific procedural skills the therapist might lack include how to respond when a service user describes an experience of racism, how to bring this into the formulation, and how to adapt the intervention accordingly (Beck, Reference Beck2019).

Looking beyond the issue of working with racism, the areas listed above from Beck (Reference Beck2016) where therapists may lack declarative knowledge will also be areas where therapists need to develop their procedural skills. These areas include engagement, formulation, intervention, supervision and use of outcome measures; as such they make up almost every part of therapeutic practice. There may therefore be a widespread skills deficit in adapting core CBT approaches to working sensitively with service users from minoritised ethnicities.

One particular challenge is how to raise ethnicity-related issues which are therapeutically important, but which the service user does not feel comfortable discussing without explicit prompting by the clinician. These issues include experiences of racism, as service users may not feel able to tell therapists about racist incidents without clear signals that their experience will not be minimised or disregarded (Beck, Reference Beck2019; Pieterse, Reference Pieterse2018; Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Phiri and Naeem2019). However, developing procedural skills around raising issues relating to ethnicity extends to all aspects of working with service users from minoritised ethnicities. The therapist needs to have the skills to sensitively ask about the general cultural context of the individual, as this will impact on how they are engaged, what type of formulation is developed, and what intervention is carried out. This is complex, as while clinicians need to be active agents in raising ethnic difference, there is a risk that therapists will have too much of a focus on ethnicity and make spurious links between all presenting clinical issues and the cultural background of the service user. Cultural factors may not prove to be of significant importance to therapeutic work, but this should be explored before being discounted. When clinicians proactively and sensitively ask service users from minoritised ethnicities about their cultural context this can have a very positive impact on therapy (Beck, Reference Beck2019; Fuertes et al., Reference Fuertes, Mueller, Chauhan, Walker and Ladany2002; Gurpinar-Morgan et al., Reference Gurpinar-Morgan, Murray and Beck2014), but there is also clear evidence that therapists can be reluctant to have these conversations (Dogra et al., Reference Dogra, Vostanis, Abuateya and Jewson2007; Knox et al., Reference Knox, Burkard, Johnson, Suzuki and Ponterotto2003). The ability to raise issues of ethnicity, without explicit prompting by the service user, is a key procedural skill for therapists to develop.

A useful aspect of the DPR model is its emphasis on general interpersonal skills as much as therapy technique specific skills. As Fig. 1 shows, interpersonal skills are broken down in the model into ‘Interpersonal perceptual skills’ and ‘Interpersonal relational skills’. Perceptual skills refers to the therapist’s ability to perceive the signals displayed by a service user (e.g. becoming attuned to their emotional state), while relational skills refers to the therapist’s ability to communicate with the service user (e.g. effectively demonstrating empathy). The adaptation of the DPR model (Fig. 2) includes the idea that therapists’ perceptual and relational skills are likely to be under-developed when it comes to working with service users from minoritised ethnicities, largely because of a lack of exposure on the part of the therapist to a variety of cultures. This idea supports Beck’s (Reference Beck2016; p. 165) proposition that a therapist who has had little contact with minoritised communities may require more support to develop their skills with service users from minoritised ethnicities.

In order to explain why white therapists’ skills might be improved by direct contact with people from minoritised ethnicities, it is helpful to consider the emphasis the DPR model places on the ‘personal self’. This is described as the attitudes, beliefs and skills which people have already developed before they start training to become therapists (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006). Aspiring therapists will hopefully already have an ability to establish relationships, and this ability will in part be founded on a familiarity with the interpersonal signals displayed by others and how relationships are made and maintained. However, these interpersonal factors are not culturally universal, with significant variance between and within different ethnic communities. For instance, there is clear evidence of cultural differences in eye contact (Akechi et al., Reference Akechi, Senju, Uibo, Kikuchi, Hasegawa and Hietanen2013), the recognition of emotions (Elfenbein and Ambady, Reference Elfenbein and Ambady2003) and how faces are perceived (Gobel et al., Reference Gobel, Chen and Richardson2017). These and other interpersonal factors will have an impact on the therapeutic relationship, again supporting Beck’s (Reference Beck2016) proposition that if therapists have not had a reasonable degree of exposure to other cultures they will be less able to perceive the interpersonal signals displayed by service users from minoritised ethnicities, and they will also find it more difficult to act in a culturally competent way which will effectively create a relationship with those service users. This is another example of how systemic societal factors may have an impact on therapeutic skills.

White therapists may therefore have a range of deficits in the procedural skills necessary to work effectively with service users from minoritised ethnicities. This potential skills deficit is made up of difficulties in applying specific therapeutic techniques, but also in general interpersonal skills. Table 1 provides some suggestions for how these deficits could be remedied.

Overloaded reflective system: cognitive, emotional and situational barriers to reflection

In the DPR model reflection is given a privileged position. Bennett-Levy et al. (Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Chaddock, Davis, Stedmon and Dallos2009) argue that reflection is key to recognising when a clinical skill needs to be further developed, for instance when a clinician realises in supervision that they need to improve how they apply a particular CBT protocol. Reflection is also thought to be important (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Chaddock, Davis, Stedmon and Dallos2009) within therapy sessions when the clinician is deciding what to do next. An example of this is when a therapist needs to decide whether or not to follow up on a potentially significant statement a service user has made. Therapists need to be able to reflect on their work to identify and address deficits in declarative knowledge or procedural skills. The hypothesis presented here is that it is precisely with service users from minoritised ethnicities that some white therapists may find it most challenging to stay reflective, and this may help explain some of the obstacles to effective psychotherapeutic work with people from minoritised ethnicities. Although there may be more barriers to reflection, three will be explored here: the cognitive demands of reflection, the emotional challenge of staying reflective, and situational factors which inhibit reflection.

Bennett-Levy et al. (Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Chaddock, Davis, Stedmon and Dallos2009; p. 121) provide a working definition of reflection as ‘the process of intentionally focusing one’s attention on a particular content; observing and clarifying this focus; and using other knowledge and cognitive processes (such as self-questioning, logical analysis and problem solving) to make meaningful links’. Figure 3 provides a schematic representation of this process.

Figure 3. A schematic representation of reflection as conceptualised within the DPR model. Figure reproduced from Bennett-Levy et al. (Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Chaddock, Davis, Stedmon and Dallos2009). Republished with permission of McGraw Hill, permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

As Fig. 3 shows, reflection as defined within the DPR model is a complex process. Reflection can be difficult (Freeston et al., Reference Freeston, Thwaites and Bennett-Levy2019; Schön, Reference Schön1983), and if not managed well it may become overwhelming and even counterproductive (Knight et al., Reference Knight, Sperlinger and Maltby2010). It is not therefore always easy for therapists to reflect on their work, so it is notable that the existing literature on cultural safety (Curtis et al., Reference Curtis, Jones, Tipene-Leach, Walker, Loring, Paine and Reid2019) and cultural humility (Davis et al., Reference Davis, DeBlaere, Owen, Hook, Rivera, Choe and Placeres2018; Hook et al., Reference Hook, Davis, Owen, Worthington and Utsey2013) has particularly emphasised the importance of being open and self-reflective in work with service users from minoritised ethnicities. Applying the DPR conceptualisation of reflection in this context could help further clarify why a reflective attitude is important in work with service users from minoritised ethnicities and why staying reflective is probably challenging for some white therapists.

Cognitive demands of reflection

Figure 3 describes a variety of cognitive processes which are thought to be essential parts of effective reflection (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Chaddock, Davis, Stedmon and Dallos2009). Reflection is therefore inherently a cognitively demanding activity. This section will explore how and why reflecting may carry even more cognitive demands for white therapists when they work with service users from minoritised ethnicities.

Figure 3 suggests that reflection proceeds through a number of cognitive steps, starting with the identification of a problem (e.g. therapy not going to plan with a service user) and ending with a conceptualisation of how the problem could be addressed. This is a positive experience if reflection leads to a clear understanding of what is going wrong and what alternative courses of action could be taken. However, if it is difficult to clarify the nature of the problem and to make a plan to address it, then reflection can be extremely cognitively challenging. As such, reflection may become overly cognitively challenging for many white therapists when working with service users from minoritised ethnicities, and this may then lead to a tendency to avoid exactly the type of reflection which is necessary to improve clinical outcomes. This hypothesis is supported by much of the existing literature. For example, Beck (Reference Beck2016; pp. 174–175) when outlining some reflective questions about work with service users from minoritised ethnicities, notes that these questions might be very difficult for white therapists. Hardy (Reference Hardy, McGoldrick and Hardy2008) argues that therapists will all too often find themselves managing the sensitivities surrounding race by avoiding the topic altogether, and Sue (Reference Sue2015) writes of a ‘conspiracy of silence’ in this area.

Several factors increase the cognitive demands of reflection when working with service users from minoritised ethnicities. One key issue is the lack of declarative knowledge about ethnicity-related issues identified above. Insufficient knowledge about the difficulties service users from minoritised ethnicities may have faced, or how therapy might be adapted to meet their needs, means that reflection becomes too cognitively challenging. To illustrate this, consider the distinction between racial trauma and traditional understandings of trauma (Pieterse, Reference Pieterse2018; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Printz, Ching and Wetterneck2018) which was referred to earlier in this piece. If a therapist is not aware of the specific nature of racial trauma they may find it very challenging to conceptualise the apparently traumatised reaction of a service user from a minoritised ethnicity to an event which would not traditionally have been defined as trauma, such as a microaggression. Indeed, a lack of knowledge may mean that the therapist will not even be able to identify this as an issue where ethnicity could be important. This extends more broadly to issues of cultural competence, as a lack of knowledge about different cultural contexts and how to work with these in therapy will mean that the therapist does not have the necessary cognitive resources to draw upon when reflecting. A lack of declarative knowledge about ethnicity-related issues makes reflection much more difficult.

Another issue highlighted above in relation to declarative knowledge was the range and extent of potentially relevant knowledge. When therapists do engage with this area they may find it very challenging to prioritise what is essential to learn, and this will lead to reflection becoming more challenging. The DPR model is particularly helpful in this regard, as it would place an emphasis on therapists having the support to reflect on what specific declarative knowledge is most relevant for the service users they are seeing. In other words, the DPR model does not advise gaining knowledge for its own sake, but rather engaging with knowledge which is required for the particular piece of clinical work being reflected on. This has close parallels with the existing literature on cultural safety and cultural humility, as this emphasises the importance of therapists maintaining a stance of openness and curiosity where they are responsive to the particular needs of the service user they are working with (Curtis et al., Reference Curtis, Jones, Tipene-Leach, Walker, Loring, Paine and Reid2019; Davis et al., Reference Davis, DeBlaere, Owen, Hook, Rivera, Choe and Placeres2018; Hook et al., Reference Hook, Davis, Owen, Worthington and Utsey2013).

Another factor which increases the cognitive demands of reflection is how ethnicity-related issues are treated at a societal level. The DPR model hypothesises that therapist skill is influenced by personal experiences outside of therapist training (Bennett-Levy and Haarhoff, Reference Bennett-Levy, Haarhoff and Dimidjian2019), and therapists’ ways of thinking will be affected by societal attitudes towards people from minoritised ethnicities. These societal attitudes can be prejudiced and unhelpful, so if therapists take on these attitudes, however unwittingly, they may be less equipped to reflect on their work with service users from minoritised ethnicities. Examples of these types of unhelpful attitudes include the so-called ‘colour-blind’ approach, and also the lack of resolution of issues surrounding ethnicity and identity.

The ‘colour-blind’ attitude is one where race and ethnicity are simply ignored (Neville et al., Reference Neville, Gallardo and Sue2016). This attitude is usually adopted by individuals within the majority or dominant ethnic group and can be held with good intentions, in the hope that if race and ethnicity are not focused on then issues such as racism will disappear. However, colour-blindness has been strongly critiqued, as ignoring ethnicity-related issues means that there is then no space for analysing how being from a minoritised community has had an impact on the individual (Sue, Reference Sue2015). The colour-blind attitude is prevalent at a societal level (Apfelbaum et al., Reference Apfelbaum, Norton and Sommers2012; Neville et al., Reference Neville, Gallardo and Sue2016), so it is unsurprising that therapists have also been found to adopt this (Patel, Reference Patel, Fleming and Stern2004). This is one specific cognitive barrier to reflection, as it does not allow issues surrounding ethnicity to be acknowledged and addressed.

Another issue within society at large which is echoed in psychotherapy is the ongoing lack of resolution of questions related to ethnicity and identity. Societal views on ethnicity have evolved significantly, but for instance in the United Kingdom (UK) parts of the population still fail to see people from minoritised ethnicities as fully and legitimately part of British life (Kelley et al., Reference Kelley, Khan and Sharrock2017). The impact of this has been powerfully described by the journalist Afua Hirsch in her book Brit(ish), with the title expressing how people from minoritised ethnicities can feel a lack of a sense of belonging (Hirsch, Reference Hirsch2018). Multiple authors in the psychotherapy field have discussed how this lack of belonging and related issues such as acculturation can have an impact on mental health (Beck, Reference Beck2016; Falicov, Reference Falicov1995; Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015). It is possible that the failure to resolve these concerns at a societal level means that therapists have fewer cognitive resources to draw upon when reflecting on how these issues could be addressed with service users.

Emotional challenges of reflection

Reflection is not just a cognitive process, as it is important that the emotions are engaged while reflecting (Freeston et al., Reference Freeston, Thwaites and Bennett-Levy2019; Lombardo et al., Reference Lombardo, Milne and Proctor2009). However, the literature on emotion and cognition in general shows that overly high emotions disrupt the cognitive processes that reflection relies upon (Dolcos and Denkova, Reference Dolcos and Denkova2014). If emotion does become too heightened, then this can lead to avoidant responses (Scherr et al., Reference Scherr, Herbert and Forman2015). For some white therapists, reflecting on their work with service users from minoritised ethnicities may be emotionally challenging, in that it may trigger strong emotions and accompanying unhelpful responses on the part of the therapist. Beck (Reference Beck2016; p. 36) notes that therapists may experience heightened anxiety when they consider raising issues of ethnicity with service users, and Hardy (Reference Hardy, McGoldrick and Hardy2008) explores how discussions of race can very easily bring up strong feelings of anger.

The emotions that might be raised for white therapists may in part be caused by the cognitive demands of reflecting on this area, as if reflection is too cognitively challenging then it is likely to become a stressful experience (Freeston et al., Reference Freeston, Thwaites and Bennett-Levy2019; Schön, Reference Schön1983). However, an additional factor is that addressing issues related to ethnic diversity, in particular the impact of racism, probably raises many uncomfortable emotions for white therapists.

There are a number of reasons why emotions might be particularly heightened in this context. White therapists may find it difficult to engage with the experiences of service users from minoritised ethnicities (Knox et al., Reference Knox, Burkard, Johnson, Suzuki and Ponterotto2003; Pieterse, Reference Pieterse2018; Utsey et al., Reference Utsey, Gernat and Hammar2005) as this brings to the fore matters of white privilege. Therapists may also simply find it too distressing to hear about ongoing experiences of discrimination, prejudice and violence, especially if they do not feel confident that they have the skills to assist service users from minoritised ethnicities to address these issues. Another emotional barrier to reflection is the fear of expressing an unacceptable attitude. Beck (Reference Beck2016; p. 163) notes that ‘worries about being considered racist or culturally insensitive’ inhibit the discussion of ethnicity-related issues in supervision, and these types of worries are seen in general when clinicians think about their work with service users from minoritised ethnicities (Dogra et al., Reference Dogra, Vostanis, Abuateya and Jewson2007). Finally, when engaging in transcultural therapy some clinicians may find themselves becoming more aware of their own unexamined biases or implicitly racist assumptions (Payne and Hannay, Reference Payne and Hannay2021), as these prejudicial attitudes are much more widely held than is commonly acknowledged (Dovidio, Reference Dovidio2001). Coming more fully into contact with these personally held prejudices may then lead to the therapist experiencing uncomfortable emotions. It seems likely that these various emotional barriers will make white therapists more reluctant to reflect on issues of ethnicity.

This article has focused on white therapists, as it seems probable that therapists from this group are more likely to lack skills in working with service users from minoritised ethnicities. However, I do also want to highlight the emotional barriers to reflection which therapists from minoritised ethnicities may experience. For this group the emotions raised may relate more to traumas and challenges faced by themselves, family members, and others from their own ethnicity; as many of these traumas have not been adequately atoned for, and racism is a daily part of our society, these emotions may feel quite overwhelming.

At a systemic level society at large does not provide significant support to help therapists manage the feelings that will come up when reflecting on this emotive area. Traumatic moments in the majority history of the UK such as the first and second world wars are focused on each year on specific days such as Remembrance Sunday and also through physical spaces such as war memorials; this allows individuals the time and space to reflect on the ongoing meaning of these events, and this makes room for more difficult emotions to be thought through. There are no comparable moments or spaces for aspects of the history of minoritised ethnicities (e.g. Lee, Reference Lee2020) and there is not therefore room to process the emotions that reflecting on this will bring up.

Situational factors inhibiting reflection

Situational factors refers to any aspect of the therapist’s working environment which either helps or hinders reflection. Reflecting on work with service users from minoritised ethnicities requires time and space, so there is room to work with the variety of cognitive and emotional barriers identified above. However, the lack of attention given to this area means that this time and space is often not available, and as a consequence therapists do not have the opportunity to effectively reflect on their work with service users from minoritised ethnicities. The lack of diversity in some psychotherapy professions (Alcock, Reference Alcock2019) and in the healthcare service in general (Kline, Reference Kline2014) also means that there are fewer clinicians from minoritised ethnicities, especially in leadership roles. It seems highly likely that this lack of diversity means that ethnicity-related issues are not given the attention they deserve in many services, and as a result reflection on this area is not prioritised.

Summary of barriers to reflection

In line with the existing literature on cultural safety and cultural humility (Curtis et al., Reference Curtis, Jones, Tipene-Leach, Walker, Loring, Paine and Reid2019; Davis et al., Reference Davis, DeBlaere, Owen, Hook, Rivera, Choe and Placeres2018; Hook et al., Reference Hook, Davis, Owen, Worthington and Utsey2013), this section has emphasised the importance of therapists taking a reflective attitude in their work with service users from minoritised ethnicities. However, applying the DPR model to this context highlights a range of cognitive, emotional and situational barriers to reflection. While of course many therapists and services will have found their own ways of managing these challenges, for the majority white psychotherapy professions as a whole reflecting on how to work with service users from minoritised ethnicities may too often feel overwhelming. This then raises the risk that reflection on this area is avoided, and the therapist does not have the opportunity to identify what they could do differently to better meet the needs of service users from minoritised ethnicities. There are probably barriers to reflection which have been missed or not given sufficient attention to, and it would be helpful to receive feedback from readers on what else could be added to the adapted DPR model (Fig. 2).

Reflection is a crucial part of addressing the deficits in declarative knowledge and procedural skills identified above. There is the risk that with the increased focus on ethnicity-related issues in psychotherapy there could be a somewhat ‘knee-jerk’ reaction of simply increasing how much therapists are taught about this area (i.e. improving declarative knowledge), or encouraging therapists to focus on gathering more direct clinical experience with service users from minoritised ethnicities (i.e. working on procedural skills), but without a corresponding increase in the opportunities offered for reflection. Neither knowledge nor experience on their own are enough: both of these aspects need to be reflected on if therapists are to genuinely and sustainably improve their skills in this challenging area. The DPR model may helpfully show how these different parts of clinical skill development fit together, and how important reflection is in allowing clinicians to improve their skills.

The psychotherapy professions therefore need to give close attention to how to encourage and enable white therapists to reflect on their work with service users from minoritised ethnicities, with a particular focus on removing cognitive, emotional and situational barriers to reflection. Suggestions for how this could occur are summarised in Table 1.

Lack of engagement with minoritised communities on a personal level

The DPR model proposes that therapist skill development is affected not just by therapeutic training, but also by the personal attitudes and beliefs of the therapist. These are denoted by the term ‘personal self’ and are thought to be important for therapists at any stage of their careers; indeed Bennett-Levy and Haarhoff (Reference Bennett-Levy, Haarhoff and Dimidjian2019) argue that more experienced therapists may bring more of their personal self into their work with service users. This is relevant to working with service users from minoritised ethnicities because many white therapists in their personal lives may have had relatively little exposure to minoritised communities. As a result they will not have had so much opportunity to develop the range of attitudes, beliefs and interests which would support them in their work with service users from minoritised ethnicities.

This hypothesis has been prefigured in the above section on procedural skills, which argued that a lack of personal exposure to minoritised communities would make white therapists less able to recognise and respond to interpersonal signals shown by service users from minoritised ethnicities. Also important, however, are the views, explicit and implicit, which the therapist will hold about service users from minoritised ethnicities. In the adapted DPR model (Fig. 2) this is denoted by the box ‘Therapist Stance/Attitude/Beliefs’.

While there will sadly be some therapists who hold explicitly racist views, the focus here is more on therapists who have not engaged with minoritised communities in any great depth, and who might therefore have unexamined biases about service users from minoritised ethnicities (Payne and Hannay, Reference Payne and Hannay2021). Applying the DPR model emphasises the importance of personal factors in how therapists address this area. If at a personal level the white therapist has had little experience of people from different cultures, then they may be less likely to have an implicit understanding of cultural difference and are probably more likely to unconsciously hold biased views about service users from minoritised ethnicities (Gawronski and Bodenhausen, Reference Gawronski and Bodenhausen2017; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Kroeper and Ozier2018). This moves the focus from the explicit type of knowledge which is gained through traditional teaching methods such as lectures, to the knowledge and awareness gained through personal experience.

Therapists wishing to improve their skills in this area may therefore find it helpful to engage at a personal level, outside of a psychotherapeutic context, with minoritised communities and the cultures of minoritised ethnicities. This echoes some of the existing literature, as for instance McCallum and Wilson (Reference McCallum and Wilson2017; p. 10) propose that therapists who work with diverse communities should consider their ‘culture, hobbies, personal obligations and values and how those may intersect with one’s professional self’. The structure of self-practice/self-reflection programmes, which explicitly make links between the personal and professional self, may also be helpful in this regard (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Haarhoff and Perry2015). Table 1 details some suggestions for steps to take in this area.

Suggestions for remedial action

Applying the DPR model to how white therapists develop their skills in working with service users from minoritised ethnicities leads to a number of recommendations for change. These are summarised in Table 1, in the hope that this could contribute to a clear understanding of the barriers to working effectively with service users from minoritised ethnicities, and how those barriers could be removed. These suggestions are not intended to be systematic or complete and it would be helpful to receive feedback about what has been missed out.

One key point to consider is how much is being asked of therapists who wish to improve their practice. The range of suggestions given in Table 1 may seem overwhelming, and it is important that the extent of potential actions to take does not become another barrier to reflecting on this area. As before, the central place of reflection in the DPR model may provide a helpful insight: if therapists can find effective reflective spaces then this may help them to identify what knowledge and procedural skills they need to gain, and thereby take a targeted approach to improving their practice in this challenging area. Irrespective of what approach is taken to skill development it seems reasonable to expect that therapists will be proactive in improving their practice with service users from minoritised ethnicities, but the onus to create change in this area should not just be on the individual therapist but on services, broader healthcare structures, and professional bodies. This latter point is especially true for therapists from minoritised ethnicities, who should receive better support from the systems they work within.

Conclusion

This article has argued that many white therapists may lack the necessary skills to work effectively with service users from minoritised ethnicities, and the DPR model of therapist skill development (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006) has been used to conceptualise this skills deficit. This may be a helpful approach because it allows a clear analysis of specific deficits, and this then directly leads to recommendations for how to improve skills.

Applying the DPR model to white therapists’ skills in working with service users from minoritised ethnicities highlights a range of deficits. There is a lack of declarative knowledge about how to adapt practice for service users from minoritised ethnicities, as none of the major therapeutic schools of therapy has yet created an adequate body of knowledge regarding ethnicity-specific considerations in therapy. With regard to procedural skills, the DPR model splits these into therapy-specific techniques (for instance cognitive restructuring in CBT or circular questioning in systemic therapies) and general interpersonal skills; for many white therapists both these areas of therapeutic practice with service users from minoritised ethnicities may be under-developed. Reflection has a central place in the DPR model, as engaging in reflection about therapeutic work allows problems to be recognised and addressed (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Chaddock, Davis, Stedmon and Dallos2009). However, there appear to be significant cognitive, emotional and situational barriers to effective reflection on working with service users from minoritised ethnicities. All these areas of the DPR model inter-relate (e.g. a lack of declarative knowledge makes reflection more difficult), and this could help explain why many white therapists find it difficult to improve their skills in working with service users from minoritised ethnicities. This is intended to be an initial exploration of the applicability of the DPR model in this context, so there may be areas of the adapted DPR model (Fig. 2) which require further consideration or elaboration.

This article has emphasised the place of the therapist’s ‘personal self’ in developing their skills in this area. The DPR model proposes that therapists draw on their personal experiences throughout their career (Bennett-Levy and Haarhoff, Reference Bennett-Levy, Haarhoff and Dimidjian2019), and engaging more at a personal level with minoritised communities and the cultures of minoritised ethnicities could lead directly to improvements in clinical skill. At present, I and a number of other psychologists are developing a self-practice/self-reflection programme for CBT therapists from minoritised ethnicities, which will explore whether working on the personal and therapist self together is helpful for this cohort (Churchard et al., Reference Churchard, Malik and Shetty Chowdhury2021).

Applying this model of skill development leads directly to recommendations as to how to address skills deficits, and there are a list of suggestions in Table 1. This is directed as much at services and broader healthcare structures as at individual therapists. One strength of the DPR model is that it generates specific predictions about which learning activities will have most impact on therapist skill (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006), so the recommendations detailed in Table 1 could be tested empirically to explore whether they do improve white therapists’ skills with service users from minoritised ethnicities.

Systemic factors, such as the continued existence of racism at a societal level (Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2016), are a major part of the adapted DPR model. For instance, the adapted model links deficits in therapists’ declarative knowledge to a lack of knowledge about ethnicity-related issues within society in general. This difficult systemic background will probably be an obstacle to skills development. It is also important to acknowledge the constraints imposed by socioeconomic conditions, as outcomes for many service users from minoritised ethnicities will be affected by factors such as poor housing and poverty.

This article is aimed at white therapists, but many of the themes raised would apply in different ways to therapists from minoritised ethnicities. My hypothesis is that there are specific barriers to reflection for therapists from minoritised ethnicities which the DPR model could helpfully conceptualise, in particular how to manage the emotions associated with racial trauma (Pieterse, Reference Pieterse2018; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Printz, Ching and Wetterneck2018). I am from a mixed-race background and I will in future articles be exploring the application of the DPR model to the experience of therapists from minoritised ethnicities.

The primary audience for this article will probably be CBT therapists, but the DPR model is intended to be relevant to all therapeutic modalities (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006). The inclusion of some systemic authors in this article such as Hardy (Reference Hardy, McGoldrick and Hardy2008) may partially demonstrate how the DPR model can make links across therapeutic schools, and this builds on Beck (Reference Beck2016) who draws on a number of systemic ideas in his work on transcultural CBT. Psychodynamic work on ethnicity has not been included, primarily because of a lack of knowledge on my part, but there is no reason in principle why psychodynamic ideas could not be linked to the DPR model. The adapted DPR model could therefore contribute to a positive dialogue between different schools of therapy around issues of ethnicity.

If this analysis and set of recommendations is useful, it is possible that the DPR model might also help understand therapists’ skill deficits in relation to other areas of diversity such as gender, sexuality, social class, and age. Similar overall categories of skills deficits might emerge from this analysis, namely deficits in declarative knowledge and procedural skills, and an inhibited reflective system. However, the specific nature of these deficits would probably be somewhat different. This does raise the question of intersectionality, as ethnicity cannot be separated out from other aspects of diversity (Fernando, Reference Fernando2010). It is beyond the scope of this article to properly address this question, but it may be that an exploration of a service user’s ethnicity should naturally lead to reflection on how other aspects of identity such as gender and age relate. The ‘Multidimensional’ framework of identity (Falicov, Reference Falicov1995), which Beck (Reference Beck2016) also draws upon, may be helpful in this regard.

There is still much work to be done before service users from minoritised ethnicities receive as standard an adequate service from psychotherapists. However, the greater focus in recent years on the experiences of minoritised communities does make it more likely that white therapists will develop their skills in this area. I hope that the ideas presented in this article will be helpful for therapists and services who wish to improve the quality of care they provide to service users from minoritised ethnicities.

Key practice points

-

(1) White psychotherapists’ difficulties in providing therapy to service users from minoritised ethnicities can be understood as a type of skills deficit. The benefit of conceptualising the issue in this way is that practical steps can then be taken to improve skills.

-

(2) It is important to improve one’s knowledge in this area and to gain more experience of working with service users from minoritised ethnicities, but this will only be of limited benefit if the knowledge and experience gained is not reflected on effectively.

-

(3) Reflecting on this work is challenging at an emotional and cognitive level, and also because situational factors often do not create sufficient space for reflection.

-

(4) There are practical steps that can be taken to make reflection on this area easier to engage with, which are summarised in Table 1. Therapists may in particular want to consider reflecting on their own ethnic identity (‘whiteness’) and how this relates to anti-racist practice.

-

(5) It seems reasonable to expect therapists to take an active role in improving their skills in this area, but responsibility for change probably lies more with services, the healthcare system in general, and professional bodies.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Richard Thwaites for the advice and encouragement he gave me as I was writing this article and for his comments on an initial draft.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares none.

Ethics statements

I have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BPS. Ethical approval was not needed for this paper as it does not present a trial.

Data availability statement

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.