Introduction

In the UK, a commitment to facilitating faster access to psychological therapies has been outlined in government policy. The Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (Department of Health, 2006) initiative in England aimed to increase the provision of psychological interventions for common mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety. In this way, care is provided within a stepped care model, wherein individuals are offered the lowest intensity treatment possible in the first instance and stepped up to a more resource intensive service if required. Similarly, in Scotland, recent Mental Health Strategies [2012–2015 (Scottish Government, 2012); 2017–2020 (Scottish Government, 2017)] committed to facilitating swift access to psychological therapies. Policy drivers also highlight the need for care to be person-centred, safe and effective (NHS Scotland Healthcare Quality Strategy, 2010). Within Scotland, the Matrix project (2015) (NHS Education for Scotland (NES) & Scottish Government, 2014) was developed in the context of these ambitions. The Matrix provides a synthesis of evidence-based interventions for mental health conditions, recommending a range of low to high intensity treatments depending on the severity of the condition. This project informs mental health service organisation and delivery.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is a widely used psychological intervention, benefiting from a significant evidence base for a range of mental health presentations (e.g. see Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, Asnaani, Vonk, Sawyer and Fang2012, for a review). Primary care mental health teams (PCMHTs) are the frontline of service delivery for mental health conditions, with depression and anxiety being among the most common presentations. Within Greater Glasgow and Clyde, PCMHTs consist of clinical psychologists, clinical associates in applied psychology, counselling psychologists, counsellors, mental health therapists and mental health practitioners, and provide brief interventions for adults experiencing common mental disorders. The PCMHT in which this study took place receives around 3500 referrals per year. Group CBT is an efficient way to deliver a psychological intervention to a large number of service users, limiting waiting times and ensuring efficiency of resource use. Indeed, group CBT is recommended in the Matrix (2015) as a low-intensity intervention for generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) and is indicated in the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines (NICE, 2009) as an intervention for mild depression.

In order to ensure that care provision is high quality, monitoring of outcomes is necessary. Evidence suggests that group CBT is effective. For example, a systematic review comparing group CBT with individual CBT found the two interventions to be comparably effective in treating depression (Lockwood et al., Reference Lockwood, Page and Conroy-Hiller2004) and a comparison of group CBT with individual CBT and individual psychodynamic psychotherapy for a variety of difficulties, the most common being generalised anxiety, found comparable clinically significant improvements across the interventions (Kellett et al., Reference Kellett, Clarke and Matthews2007). Within the context of Greater Glasgow and Clyde, an audit of Clinical Outcome Routine Evaluation Measure (CORE-10) data completed at CBT group contacts across a 10-month period within a PCMHT demonstrated that 48.1% of 104 individuals who completed a group for low mood and anxiety (‘CBT in Action’) demonstrated a clinically significant reduction in CORE-10 scores (Wainman-Lefley, Reference Wainman-Lefley2018).

Additionally, the literature demonstrates good satisfaction with group CBT interventions among service users. Kellett et al. (Reference Kellett, Newman, Matthews and Swift2004) compared group CBT with individual CBT for anxiety [including GAD, mild post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), agoraphobia, mild obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and panic disorder] within primary care and found a high level of satisfaction with the group intervention, and Brown and colleagues (2011) provided patients with depression with either group CBT or individual CBT and found an equal level of satisfaction with treatment between the two groups. However, despite individuals who have received a group intervention reporting satisfaction with their treatment, perceptions around group treatments remain negative: Brown and colleagues (Reference Brown, Sellwood, Beecham, Slade, Andiappan, Landau, Johnson and Smith2011) reported that at baseline 70% of their sample (n = 91) reported a preference for individual CBT, with just 10% preferring group CBT. Evidence is needed regarding the key elements in group interventions that are valuable, and which, if any, hinder therapeutic benefit. Having a greater understanding of these factors could facilitate the planning and altering of services, as well as equipping health care providers with information to provide to potential service users to allow them to make informed choices about their healthcare.

This study utilised quantitative and qualitative evidence gathered via a patient satisfaction questionnaire routinely administered to service users in attendance at a PCMHT in Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Scotland to evaluate service user satisfaction with group interventions. Specifically, qualitative evidence gathered from questionnaires was used to identify the aspects of group interventions that service users found helpful, and those that were not helpful.

Method

Group interventions within the PCMHT

Patient satisfaction questionnaires completed by service users attending three CBT groups within the PCMHT were collected. These groups are described below.

(1) CBT in Action: a 7-week course based on a CBT model which aims to help attendees manage symptoms of stress, depression and anxiety. This group focuses on psychoeducation to the CBT model, and teaches skills in goal setting, behavioural exposure, thought challenging, activity scheduling, assertive communication, and problem solving. Additionally, psychoeducation around lifestyle factors impacting upon mental health, including exercise, relaxation, sleep hygiene and alcohol use, is provided.

(2) Sleep: a 4-week course based on a CBT model which aims to help attendees with sleep difficulties. This group focuses on psychoeducation around sleep difficulties and sleep hygiene and teaches relaxation techniques and thought challenging skills.

(3) Self-esteem: a 6-week course based on a CBT model which aims to help attendees tackle low self-esteem. This group focuses on psychoeducation around the development and maintenance of low self-esteem, and teaches skills in thought challenging, behavioural experiments, enhancing self-acceptance, and assertive communication.

All incoming referrals to the PCMHT were screened by staff. Electronic/paper notes were first read and referrals that were accepted were then offered a 30-minute telephone call, or, in the case of more complex referrals, a face-to-face assessment to triage to the appropriate intervention. Presenting difficulties and individual goals and preferences were considered when allocating service users to group or individual interventions. Formal diagnoses were not required for group interventions. However, if service users presented with mild to moderate anxiety and/or depression and would appear to benefit from psychoeducation around CBT strategies, group interventions were recommended. Discussion with service users ensured that their preferences were taken into account. Where staff were unsure of the appropriate intervention to recommend, cases were discussed at weekly team meetings. The most common primary presentation among group attendees was anxiety. Presenting problems were identified via multiple sources of information, including electronic/paper notes and clinical interviews. In some instances, diagnoses were provided to service users by other services prior to referral to the PCMHT. No structured psychiatric assessment tools were used when allocating service users to groups within the PCMHT. Groups were facilitated by staff within the PCMHT. Training to facilitate groups was a gradual process; staff first shadowed a group, then presented agreed sections of a group with an experienced co-facilitator. Once both the new presenter and experienced facilitator agreed that it was appropriate, the new presenter became a lead facilitator.

Sample

An opportunity sample of patient satisfaction questionnaires completed for CBT groups running within the PCMHT between January and August 2018 were collected. Questionnaires were completed at the final session of each group. All service users present at the final session of a group intervention completed a questionnaire. Service users did not receive any intervention other than the group before completing the questionnaire.

Demographic information for group attendees and data on group attendance were obtained from an electronic patient record system.

Ethical issues

Patient satisfaction questionnaires were completed as part of routine clinical practice within the PCMHT and were completed anonymously. Approval to access electronic notes, which were not anonymised, was sought and obtained from the National Health Service (NHS) Greater Glasgow and Clyde (GG&C) Caldicott Guardian.

Measure

The patient satisfaction questionnaire is a 13-item questionnaire that was developed in conjunction with the NHS GG&C PCMHT Operational Policy (2014). Ten items offer a 4-point Likert-scale response as well as an additional comments section. Example items include: How would you rate the service you received? and To what extent has our service met your needs? Three items offer a free text response. Example items include What did you find the most helpful about attending the service? and What did you find the least helpful about attending the service?

Analysis

Questionnaires were analysed via frequencies and percentages for Likert-scale responses and thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clark2006) for free text responses. Free text responses were read in detail and preliminary themes identified. Responses were read repeatedly to identify patterns in the data and coded according to coding categories that emerged from within the data. Themes that were related to each other were then grouped together and organised hierarchically into master themes and subthemes.

Results

Demographic information

During the observation period, 103 individuals attended the first session of one of nine CBT groups that ran within the PMCHT, as follows:

CBT in Action: n = 5 groups, including 82 attendees, with groups ranging in size from 12 to 21 attendees at the first session.

Sleep: n = 3 groups, including 17 attendees, with groups ranging in size from five to six attendees at the first session.

Self-esteem: n = 1 pilot group, including four attendees at the first session.

Table 1 describes the descriptive statistics of the demographic information of group attendees. Of these individuals, 70 (68.0%) attended >50% of group sessions, and 55 (53%) attended the final group session and completed a patient satisfaction questionnaire.

Table 1. Demographic information of group attendees

Scaled responses

Thirty-six group attendees (65.1%) rated the group intervention they received as ‘excellent’ (Fig. 1). Seventeen group attendees (30.9%) reported that ‘almost all’ of their needs were met through attending the group (Fig. 2). Thirty group attendees (54.5%) indicated that the group intervention helped them ‘a great deal’ in dealing with their problems (Fig. 3).

Figure 1. Percentage ratings of groups by attendees.

Figure 2. Percentage ratings of how groups met attendees’ needs.

Figure 3. Percentage ratings of how groups helped attendees to deal with their problems.

Free text responses

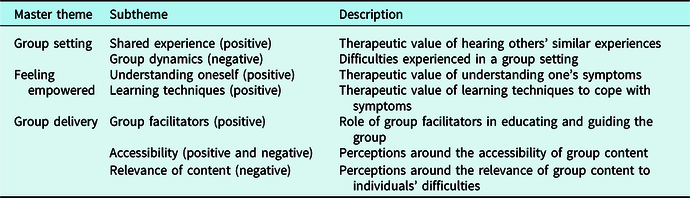

All returned questionnaires contained at least one free text response. Table 2 describes the master themes and subthemes identified through thematic analysis conducted on the free text responses. Both positive and negative themes contributing to attendees’ overall satisfaction with the interventions were identified. As similar themes were identified across responses from the different groups, the qualitative data across the groups were analysed as a whole. These themes are described in detail in the following section.

Table 2. Master themes and subthemes identified from qualitative analysis of free text responses

Group setting

Perceptions around the group context were mixed. Some found the group setting itself valuable, while others felt that the group format had been a barrier to therapeutic benefit from the intervention.

Shared experience

A significant number of respondents found the group setting to be a helpful component of the intervention. This was attributed to the reassurance that meeting other people with shared experiences provided: ‘It was good to hear others struggled with similar things’. In this way, the group format helped to normalise the experience of mental health difficulties and helped attendees to feel less isolated in experiencing their symptoms: ‘I didn’t feel so alone or weird’. As well as offering a feeling of inclusion, attendees were also able to discuss different approaches to coping with their difficulties with others in the group: ‘Chat within the group [about] how we tackle our issues [was helpful]’. This perception of similarity contributed to the development of a group environment in which participants felt ‘safe to talk’, which meant that attendees were more actively involved in the intervention: ‘The atmosphere of the group was comforting … which made it much easier to be open and honest about situations and problems’.

Group dynamics

Conversely, others felt that the group setting had hindered their experience of the intervention. For example, some were ‘too shy to speak out’. Indeed, the group environment was off-putting to some from the outset of the intervention, with the prospect of joining such an environment feeling overwhelming: ‘When I came into this class I saw how many people were here and almost left again’. For some, their perceptions around attending a group intervention had changed: ‘I didn’t think I wanted a group thing … but it has been helpful’. Additionally, in some groups there appeared to be clashes in personalities, with some attendees feeling that others had taken up too much space within the group dynamic: ‘There was one individual who often led the conversation off topic for whole lengths of time’. Alternatively, others felt that their fellow participants had not expressed themselves sufficiently: ‘I would have liked the group to open up a lot more and for us to share examples out’. As a consequence of feeling some discomfort within a group setting, some attendees expressed a preference for individual therapy. For most, this preference appeared to be related to a perception that an individual intervention would allow them to ‘open up’ more in a way that was not possible in a group environment: ‘I would have preferred individual therapy to address past issues’. As the groups were psychoeducational in nature, with a focus on the present, it is possible that these difficulties with ‘opening up’ were due to the aims and scope of the groups, or to difficulties in speaking in front of other group members; or, indeed, to both.

Feeling empowered

Many attendees indicated that attendance at the groups had improved their confidence in coping with their difficulties, which in turn had contributed to a greater sense of wellbeing overall: ‘I’m coping so much better now, and feeling so positive’. This improvement was attributed to developing a greater understanding of oneself and learning new coping strategies.

Understanding oneself

Participants described that the intervention had equipped them with a new perspective from which to view their difficulties: ‘This class has made me aware and really think about things I never have before’. Furthermore, the CBT model helped attendees to appreciate how and why their difficulties had developed, which was a validating experience: ‘Understanding that the way I was feeling and my thoughts were a “real thing” … not all my imagination [was the most helpful thing]’.

Learning techniques

The CBT techniques covered within the interventions, including goal setting, behavioural exposure, thought challenging, activity scheduling, assertive communication, and problem solving, equipped attendees with ‘tools’ to both identify their difficulties: ‘It has been most helpful in … helping me to recognise unhealthy behaviours/thoughts’ and to manage them, contributing to an increased feeling of confidence for the future: ‘I have tools to help me move forward’. While specific techniques were not highlighted in service users’ responses on the questionnaires, the range of techniques covered within the intervention reinforced attendees’ confidence: ‘[I have] so many different techniques I feel that if one stops working I have plenty to fall back on’. Indeed, there was a recognition among attendees that they might continue to experience difficulties in the future, but a perception that they would be able to cope should the need arise: ‘I … feel much better equipped to deal with bad times’.

Group delivery

Perceptions around the content and delivery of the groups were mixed. While the content had resonated with some attendees, others felt that it had not been appropriate for their needs, or they had struggled with the amount of content that was covered.

Group facilitators

The group facilitators were frequently identified as an important part of the group intervention, praised for their ability to offer insights into mental health in general, and to effectively deliver the group content: ‘[The group facilitators] were very calm and so insightful, they put things in such a clear and memorable way’. The facilitators also played a role in setting up a positive environment, contributing to the feeling of safety described earlier: ‘A great deal of care was taken by [the group facilitators] to make this a helpful and safe environment’.

Accessibility

Some attendees appeared to struggle with the speed with which the group content was delivered, commenting that there was a great deal of content covered within a short timescale: ‘[It was] a lot to learn in a relatively short space of time’. In this way, the provision of handouts was described to be helpful in allowing participants to reflect on the content of the intervention out with the group environment: ‘The handouts and homework … allowed me to go back over techniques’.

Relevance of content

As discussed previously, group attendees consistently commented that the CBT techniques covered within the group interventions were helpful in tackling their difficulties. Some attendees identified specific aspects of the content that had been especially relevant to them, for example: ‘[The] assertiveness session and problem solving [were most helpful] as these are areas that I know were my weak spots’. However, others commented that the content covered had been less helpful. For some, the groups lacked detail: ‘[It was] a bit too basic sometimes’, whereas for others the focus had not met their needs: ‘[There was a] large focus on anxiety – depression I feel is more my issue’.

Discussion

The quantitative component of the patient satisfaction questionnaire revealed a high level of satisfaction with CBT groups, consistent with previous literature (e.g. Kellett et al., Reference Kellett, Newman, Matthews and Swift2004). However, the drop-out rate for the groups was high, with only 53.4% of those who attended the first session of a group also attending the last session. As the duration of group interventions ranged from only 4 to 7 weeks, this level of drop-out from a relatively low commitment intervention is significant. The quantitative data are only representative of those who attended the final session of a group and are therefore likely to be biased towards a more positive evaluation. It is also important to note that general satisfaction is not the same as reductions in symptomology; as satisfaction questionnaires were completed anonymously, it was not possible to link data on satisfaction with the groups with any change – or lack thereof – in symptomology. However, an audit of the implementation of outcome measures within group interventions in the PCMHT found that service users who completed groups showed reliable and clinically significant reductions in symptoms, as measured by the CORE-10 (Barkham et al., Reference Barkham, Bewick, Mullin, Gilbody, Connell, Cahill and Evans2013), for 48.1% of 104 individuals who attended the CBT in Action group (personal communication of unpublished data). Taken together, these findings support the use of group interventions for individuals experiencing low mood and/or anxiety within a primary care setting.

The themes uncovered are related to both CBT and to the group environment. The majority of the comments in relation to the CBT content of the groups were positive; the groups equipped attendees with an increased awareness and understanding of their difficulties, alongside a range of techniques with which to cope with them. However, the group environment led to more mixed perceptions. For some participants, the groups covered material that was felt to be irrelevant to their needs. Furthermore, some attendees described disappointment that they had been unable to share their own stories with the group, and others shared a perception that the groups had been too fast-paced, with a significant amount of information delivered within a short space of time. These perceived limitations are possibly related to the aims of the intervention; as the groups are psychoeducational rather than therapeutic, a range of information is covered in order to cater to an array of needs, and many of the tasks of the intervention are relatively self-directed. The purpose of interventions should be made clear to potential attendees prior to their participation, in order to ensure that service users have appropriate expectations of the intervention that they are offered.

Dynamics within groups were perceived to be both a facilitator of, and a barrier to, therapeutic benefit. Some attendees found value in meeting other people experiencing similar difficulties, finding this to be a normalising and validating experience. This finding is in accordance with previous research; Kellett et al. (Reference Kellett, Clarke and Matthews2006) asked service users attending group CBT to complete the Session Impact Scale, finding that those who perceived greater interpersonal impact from the sessions experienced a clinically significant reduction in symptoms. The authors hence suggest that the active ingredient in CBT groups may be normalisation. However, within this sample, some attendees did not feel able to participate fully in the group, either due to their own discomfort in a group setting, or due to others dominating group dynamics. Indeed, in a review of group CBT formats, Morrison (Reference Morrison2001) cautioned that within group interventions there is a danger that one individual may ‘monopolize the group’. Clinical services offering group interventions could consider providing training on managing group dynamics to staff facilitating groups in order to manage this important component of group interventions.

The results from this study highlight factors related to group interventions that could engender drop-out. However, a qualitative study investigating reasons for drop-out among service users who attended psychoeducational interventions within a primary care team in England found that 75% of reasons for drop-out were related to personal factors such as other commitments, rather than to dissatisfaction with the intervention (Tikka et al., Reference Tikka, Jones and Law2010). More research is required to determine service users’ reasons for dropping out of group interventions.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is the mixed methods design; the qualitative analysis of free text responses provided on the patient satisfaction questionnaire facilitated a deeper understanding of the components of group CBT interventions that are of benefit to attendance and those that are not than would be possible using purely quantitative survey methods. Furthermore, 100% of individuals who attended a final group session within the observation period completed a patient satisfaction questionnaire; thus, this study captured the views of this population in its entirety.

This study is limited by the small number of participants represented in the Sleep and Self-Esteem groups. Furthermore, the Self-Esteem group was a pilot, so the content and perceptions of this group may be liable to change. The most significant limitation of this study is the lack of perspectives from service users who dropped out of the groups, who are arguably the most likely to be the least satisfied with the interventions. However, the qualitative data provided some perspectives on aspects of the groups that participants were dissatisfied with, possibly elucidating some reasons why others may have dropped out. Future research should follow up service users who drop out of group interventions in order to establish their reasons for doing so. Such an endeavour could offer important insights into ways in which information around group interventions is provided to service users, or ways in which interventions can be altered in order to provide good quality care without compromising on the efficiency of resource use. However, ethical issues associated with following up individuals who have chosen to drop out of a psychological intervention may render such work difficult.

Conclusions

The findings from this study indicate that, among those who complete group CBT interventions within the Greater Glasgow and Clyde health board, satisfaction with these interventions is high. CBT techniques are perceived to be helpful, but group dynamics may be both a facilitator of, and a barrier to, therapeutic benefit, depending on individual factors. Indeed, drop-out from the groups in this sample was high, and future research could follow up individuals who drop out of group interventions in order to inform future service delivery. Additional research examining perceptions of CBT groups in other health boards is also required in order to generalise findings to wider contexts.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the service users who completed patient satisfaction questionnaires, as well as PCMHT staff who distributed and collected the questionnaires.

Financial support

This work was supported by NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde.

Conflicts of interest

Dr Genevieve Young-Southward, Dr Alison Jackson and Dr Julie Dunan have no conflicts of interest with respect to this publication.

Ethical statement

Authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct, as set out by the APA. As this study involved anonymous data collected as part of routine clinical practice, ethical approval was not required. NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde Caldicott Guardian approval to access clinical notes was sought and obtained.

Key practice points

(1) Delivering CBT in group format may be helpful for service users within a primary care setting. However, group dynamics may be both a facilitator of, and a barrier to, therapeutic benefit, depending on individual factors.

(2) Service users may have negative perceptions regarding group CBT and may therefore be reluctant to engage with groups.

(3) Exploring individual service users’ needs and expectations regarding interventions could help to identify whether group CBT is appropriate.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.