Introduction

Combining behavioural and cognitive approaches

Exposure and response prevention (ERP) is a brief psychological treatment (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Yadin and Lichner2012) recognised as one of the first-line treatments for obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) (Abramowitz et al., Reference Abramowitz, Taylor and McKay2005; American Psychiatric Association, 2007; McKay et al., Reference McKay, Sookman, Neziroglu, Wilhelm, Stein, Kyrios and Veale2015). Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated that ERP as a stand-alone intervention leads to clinically significant and persistent symptom reduction (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Liebowitz, Kozak, Davies, Campeas and Franklin2005; Lindsay et al., Reference Lindsay, Crino and Andrews1997; van Oppen et al., Reference van Oppen, van Balkom, Smit, Schuurmans, van Dyck and Emmelkamp2010). However, some studies have reported that up to 50% of participants are left with residual symptoms (Abramowitz et al., Reference Abramowitz, Blakey, Reuman and Buchholz2018). Theoretically underpinned by behavioural theory, ERP hypothesises that engagement in prolonged and repeated exposure to a hierarchy of the person’s obsessional triggers, in the absence of their compulsive rituals (response prevention), will lead to fear habituation (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Yadin and Lichner2012; Likierman and Rachman, Reference Likierman and Rachman1980; Rachman et al., Reference Rachman, de Silva and Röper1976; Rachman et al., Reference Rachman, Cobb, Grey, McDonald, Mawson, Sartory and Stern1979). ERP proponents acknowledge that adherence is dependent on the patient having ‘a clear understanding of how and why ERP works’ in order to be sufficiently motivated to engage in the challenging exposure programme (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Yadin and Lichner2012, p. 3). Some studies have reported a high proportion of treatment refusal (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Liebowitz, Kozak, Davies, Campeas and Franklin2005; Franklin and Foa, Reference Franklin and Foa2002) and drop-out rates of 25–30% (Abramowitz et al., Reference Abramowitz, Taylor and McKay2005), although others have questioned the accuracy of these estimates (Öst et al., Reference Öst, Havnen, Hansen and Kvale2015). A meta-analysis identified that cognitive therapy (CT) RCTs have the lowest rate of attrition (11.1%) compared with trials of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) (15.5%) and ERP (19.1%) (Öst et al., Reference Öst, Havnen, Hansen and Kvale2015). The same review identified an average treatment refusal rate of 15% across all trials and noted that methodological limitations in reporting meant that it was not possible to make any conclusions about the contributing factors (Öst et al., Reference Öst, Havnen, Hansen and Kvale2015). These ongoing questions about the acceptability and tolerability of ERP have been linked to the emotionally demanding nature of the exposure programme (Abramowitz et al., Reference Abramowitz, Taylor and McKay2005; Mancebo et al., Reference Mancebo, Eisen, Sibrava, Dyck and Rasmussen2011). For example, a longitudinal observational study of CBT usage in routine clinical settings identified the most important reason given by patients for ending treatment was ‘fear/ anxiety about participating in treatment’ (Mancebo et al., Reference Mancebo, Eisen, Sibrava, Dyck and Rasmussen2011).

For individuals who experience ERP as intolerable, growing evidence indicates that the integration of ERP with elements of cognitive therapy into an integrated approach (CBT for OCD) may offer a solution. In the UK, national treatment guidelines recommend a stepped care treatment model in which CBT incorporating ERP is the first-line treatment (NICE, 2005). Influenced by Beckian cognitive theory (Beck, Reference Beck1979), CBT for OCD highlights the role of dysfunctional cognitive beliefs and appraisals of intrusions in maintaining OCD (Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis1985, Reference Salkovskis1999). This model is supported by evidence from experimental studies which highlight six belief domains implicated in OCD: over-importance of thoughts and control of thoughts (Rachman, Reference Rachman1997), inflated responsibility (Salkovskis et al., Reference Salkovskis, Wroe, Gledhill, Morrison, Forrester, Richards and Thorpe2000), threat over-estimation, perfectionism, and need for certainty (Tolin et al., Reference Tolin, Abramowitz, Brigidi and Foa2003). Concepts such as ‘thought–action fusion’ and metacognitions have also been identified as important in OCD (Myers et al., Reference Myers, Fisher and Wells2009; Shafran et al., Reference Shafran, Thordarson and Rachman1996). However, when measured by the Obsessive Beliefs Questionnaire (OBQ), three factors are identified: (1) responsibility/threat estimation, (2) perfectionism/intolerance of uncertainty and (3) importance/control of thoughts (Steketee et al., Reference Steketee, Frost, Bhar, Bouvard, Calamari, Carmin and Pollard2005). CBT for OCD aims to identify and modify these cognitive appraisals through the collaborative development of an individualised formulation (capturing the patient’s high-order appraisals), cognitive restructuring work, and behavioural experiments using exposure to disconfirm unhelpful beliefs and develop a less threatening explanation of the problem (Bream et al., Reference Bream, Challacombe, Palmer and Salkovskis2017; Salkovskis and Kirk, Reference Salkovskis and Kirk2015). Thus, while the use of exposure techniques in ERP and CBT overlap, the rationale for exposure work differs (Abramowitz et al., Reference Abramowitz, Taylor and McKay2005).

A recent meta-analytic study combined clinical data from over 350 participants at eight OCD clinics and found evidence for large effect sizes for both behavioural therapy (ERP), and CT, and integrated CBT for OCD (Steketee et al., Reference Steketee, Siev, Yovel, Lit and Wilhelm2019). Consistent with this, a meta-analysis conducted by Öst et al. (Reference Öst, Havnen, Hansen and Kvale2015), which examined the efficacy of cognitive and behavioural treatments for OCD, concluded that there is no significant difference between CT and ERP and no additive benefit from combining them. However, the question of which version of treatment may be better suited to whom is still under investigation. It has been suggested that by adding a cognitive component the acceptability of treatment may be increased, leading to lower drop-out rates (Abramowitz et al., Reference Abramowitz, Taylor and McKay2005) and larger reductions in OCD symptoms (Rector et al., Reference Rector, Richter, Katz and Leybman2019). One recent RCT showed that the addition of CT to ERP did produce greater improvements in OCD symptoms and obsessive beliefs than the ERP condition alone (Rector et al., Reference Rector, Richter, Katz and Leybman2019), but more trials are needed (Öst et al., Reference Öst, Havnen, Hansen and Kvale2015).

The increased emphasis on assessment, psychological formulation and conceptualisation in CBT is a notable point of difference from ERP. In a typical treatment course of 16 weekly sessions, the ERP protocol only recommends two initial sessions to: conduct an individual assessment, introduce the model and rationale for ERP, and explain the treatment programme (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Yadin and Lichner2012). It can be hypothesised that the limited time allocated to assessment, formulation and treatment rationale in an ERP protocol may be a contributing factor in a patient’s refusal or disengagement in treatment. One advantage to an approach that incorporates a cognitive focus may be the emphasis placed on the importance of conducting a detailed assessment and building a collaborative formulation (Bream et al., Reference Bream, Challacombe, Palmer and Salkovskis2017). Cognitive case formulation is viewed as central to good CBT practice and is thought to be associated with more effective treatments (Zivor et al., Reference Zivor, Salkovskis and Oldfield2013a). It is hypothesised that collaborative case formulation enhances therapy process by improving the working alliance and providing a ‘container’ by making sense of puzzling experiences (Nattrass et al., Reference Nattrass, Kellett, Hardy and Ricketts2015).

The NICE guidelines recommend that a patient who has undergone two or more courses of psychological treatment (augmented with medication), but has not benefited, should be stepped up and be offered further levels of care and potentially a specialist or intensive version of treatment (NICE, 2005). However, a study of patients deemed to be ‘treatment resistant’ and referred to a specialist OCD centre found that although patients reported undertaking therapy, the majority of CBT/ERP treatment that had been offered was inadequate or not adequately engaged with (Stobie et al., Reference Stobie, Taylor, Quigley, Ewing and Salkovskis2007).

It is possible therefore that some OCD patients are not offered high-quality case formulation in their treatments. Case formulation is a complex CBT skill (Roth and Pilling, Reference Roth and Pilling2007) and formulation quality is not widely assessed in practitioners (Zivor et al., Reference Zivor, Salkovskis, Oldfield and Kushnir2013b). CBT therapists can lack confidence in their formulation skills compared with their overall self-rated CBT skills (Zivor et al., Reference Zivor, Salkovskis, Oldfield and Kushnir2013b). In a study comparing formulation skills of clinicians in routine practice with highly specialist clinicians, the more experienced practitioners introduced the case formulation earlier in treatment and used a more collaborative, individualised approach (Zivor et al., Reference Zivor, Salkovskis, Oldfield and Kushnir2013b).

For patients who have undertaken previous courses of therapy from which they have not benefited, careful consideration of both engagement and understanding what had previously not worked may be an important part of any further treatment offered. One study suggested that good quality case formulation in the early stages of CBT for OCD improved the working alliance and reduced patients’ distress, although there was no association with treatment outcome (Nattrass et al., Reference Nattrass, Kellett, Hardy and Ricketts2015). The authors conclude that good quality case formulation in CBT for OCD may have a functional role in improving treatment engagement and reducing drop-out (Nattrass et al., Reference Nattrass, Kellett, Hardy and Ricketts2015), but they stress that it is not yet understood by what mechanism this process operates.

Further research is clearly warranted to understand the patient experience of case formulation and how CBT approaches might improve OCD treatment engagement in comparison with ERP approaches. Mental health services need better ways of supporting patients who may have had negative experiences of ERP to re-engage with psychological treatments for OCD.

Aim

The study aimed to examine if CBT for OCD with an extended period of assessment and formulation would:

(1) Aid in engagement with a patient who showed limited improvement to two previous courses of ERP-based treatments, as measured by attendance, homework adherence and full participation in exposure-based tasks;

(2) Lead to an improvement in OCD symptoms, general functioning and mood, assessed by standardised measures, behavioural idiographic measures and qualitative report.

Method

Design

This case study used an A–B single-case experimental design (Morley, Reference Morley2017). During the 3-week baseline period (phase A), the patient received no psychological intervention. In treatment phase 1, the patient attended five sessions which focused on assessment and longitudinal formulation. In phase 2, the patient attended for 10 sessions in which the intervention (CBT for OCD) was delivered.

Participant

This study describes the case of Anna (pseudonym), a 30-year-old White British woman who had a diagnosis of OCD. Anna first presented to mental health services 3 months after the sudden onset of debilitating OCD symptoms, specific to a fear of contamination by germs. She was referred to a primary care psychological therapy service where she participated in 23 weekly sessions of one-to-one ERP over 5 months, with limited success. She was discharged and experienced a full relapse of symptoms 2 months later. Anna was put under the care of a Community Mental Health Team (CMHT) and in line with NICE guidance, was offered a further course of psychological therapy as she had not adequately benefited from the initial treatment provided (NICE, 2005). At this time, Anna was also encouraged to accept an increase in her SSRI medication (sertraline). While on the CBT waiting list, a mental health nurse met with Anna in her home and provided 28 fortnightly sessions of ERP-based support over 11 months. Although Anna reported that she was able to achieve some small gains from ERP (e.g. being able to stroke her dogs, reducing time spent cleaning her desk), her covert rituals strengthened, and her OCD remained intact. This ERP work ended 1 month prior to the collection of baseline measures for this case study.

Measures

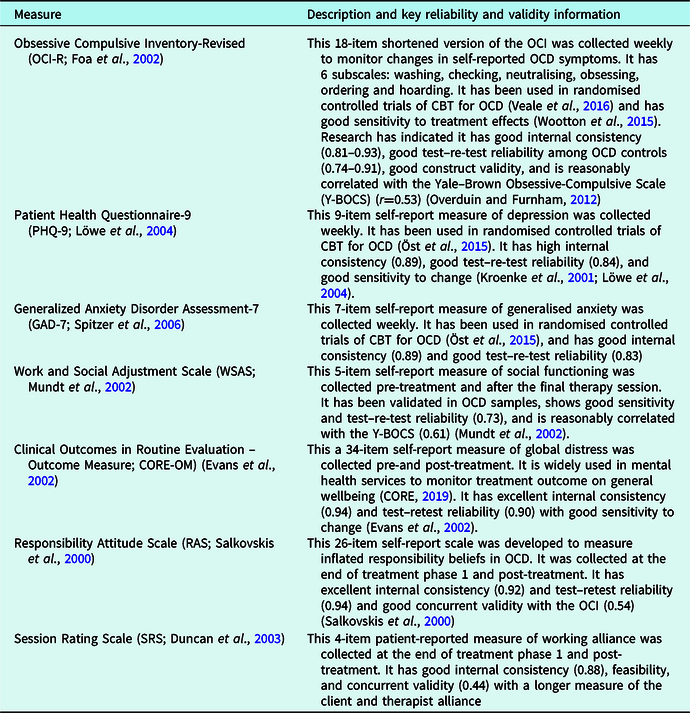

Anna completed the measures outlined in Table 1 at the time points indicated to monitor progress.

Table 1. Standardised measures

Behavioural idiographic measures were logged by the patient over a 1-week period both pre- and post-intervention. The patient opted to monitor the following OCD-related behaviours, as she felt these were all signs of the extent to which ‘OCD is in control’:

Duration of handwashing episodes

Duration of bedtime mental rituals

Duration of desk cleaning

Money spent on cleaning products

Total time spent doing OCD rituals per day

For each of these behavioural measures pre-baseline data were also extracted from the patient’s electronic case notes, where available.

Data analysis strategy

Data were displayed graphically and analysed visually for slope, trend and variability. Reliability index and clinically significant change information was included where published data for these measures were available. Anna was unable to complete the weekly measures for 3 (out of 23) weeks; missing values were not substituted as this may have affected data visualisation.

Assessment

Presenting problems

An extended assessment of Anna’s presenting problems was carried out over five sessions. Anna reported that her main difficulties were intrusive thoughts about contamination from germs, as well as anxiety and low mood. She said she struggled to leave her house more than once a week and would need to engage in extensive mental planning in order to do so. Both prior to eating and after returning to the house, Anna would engage in hand-washing rituals lasting for 45 minutes which, if interrupted, would need to be repeated. Multiple layers of disposable and rubber gloves were used to clean areas of the house, particularly her work desk which she spent 20 minutes cleaning each day. Extensive night-time rituals included repetition of mental ‘wishes’ that lasted for up to 2 hours whilst pacing around her bedroom. In total, Anna estimated that her OCD rituals took 6–7 hours to complete per day. Anna’s clinical presentation and score on the OCI-R (>21) at baseline was consistent with a diagnosis of OCD (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Huppert, Leiberg, Langner, Kichic, Hajcak and Salkovskis2002).

Anna’s overall goal for therapy was to ‘get my life back’, which was operationalised into the following ‘SMART’ goals: to open the clinic front door without assistance, to visit a supermarket and pay for one item, to visit a coffee shop and consume one drink, and to attend a social event.

A risk assessment was conducted, and no suicidal ideation or self-harming behaviour was reported.

Identifying engagement issues

Although Anna had previously attended a total of 51 sessions where the focus was on ERP for OCD, it was identified that she had struggled to engage fully with exposure work because it felt ‘too risky’ to entirely drop her compulsions. Anna described how she ‘didn’t understand OCD or where it had come from’ or the rationale for doing high-level exposure work. She also said she had struggled to trust her first therapist and had not disclosed details of her covert compulsions because they felt shameful.

Assessment also identified that the previous engagement issues may also have been due to Anna’s therapists inadvertently colluding with her OCD. For example, Anna reported that one practitioner had offered for her to sit on plastic when in the clinic and another only saw her for treatment at home. It was hypothesised that whilst these therapeutic adjustments may have helped Anna to feel she could trust services, these actions inadvertently reinforced her belief that fully engaging with treatment would be ‘too risky’ and that she could not cope with the anxiety associated with this.

Conceptualisation

Through the conceptualisation Anna came to understand why her OCD developed and how it was maintained (see Fig. 1). From an early age, Anna had a very close bond with her immediate family. Her family home was a safe and supportive environment and leaving this to begin primary school caused her significant separation anxiety. She was extra sensitive to what others thought about her and as a result, she found it hard to form friendships and became socially isolated at school. These experiences undermined her sense of self-worth and increased her anxiety. Anna started to avoid school and spent increasing amounts of time with her family. During this period, she learned that spending time in the school sick room enabled her to escape from situations that made her feel anxious. From age 14 she was home-schooled, and she felt more secure and was able to focus on her education. These experiences led Anna to form the beliefs: ‘I am vulnerable’, ‘the world is a risky place’ and ‘the future is unpredictable’.

Figure 1. Longitudinal cognitive behavioural formulation of Anna’s difficulties following Salkovskis et al. (Reference Salkovskis, Wroe, Gledhill, Morrison, Forrester, Richards and Thorpe2000).

In adulthood Anna worked as a professional in a hospital setting which brought her a sense of fulfilment and self-worth. However, this was interrupted by two episodes of illness which required long absences from work. By going through an extensive period of sick leave, it is possible that Anna found herself unconsciously re-enacting patterns from her childhood where she had learned to associate being absent from school (or work) with reducing feelings of anxiety relating to poor self-worth. She longed to return to work and thus when her contract was not renewed, this represented a huge loss and activated her previous beliefs.

Anna later contracted a gastric bug and became particularly distressed with the prolonged nature of the illness, her uncertainty over when it would end, and the debilitating effect it had on her sense of being in control. Anna’s rules for keeping safe had been violated (e.g. ‘if I keep in control, then I will be safe’) and her beliefs about being vulnerable were triggered.

Anna developed intrusive thoughts regarding becoming ill again and when presented with uncertain situations such as needing to open a door, she experienced obsessive thoughts such as ‘there might be germs there’, ‘I’ll get ill with a stomach bug’, ‘my family will catch it from me’ and ‘I won’t be able to control it’. Anna interpreted these obsessions to mean that she was vulnerable and that ‘I am responsible for knowing about germ risks and preventing harm from coming to others and myself’. As a result, Anna developed strategic behaviours to keep herself safe including: extensive mental planning, avoidance, cleaning rituals, hand washing, seeking reassurance from others, mental verification, and extensive repetition of mental wishes to ‘please let me not be ill’. These strategies maintained Anna’s OCD. The belief that she was vulnerable was not challenged; it was instead perpetuated by the enactment of compulsive behaviours that she believed were preventing illness and providing her with a sense of being in control.

Paradoxically, Anna also started to feel increasingly unable to control the OCD. As Anna’s extensive OCD rituals encroached further into her work, personal and social functioning, Anna began to feel an increasing sense of hopelessness and frustration, and she developed secondary depression. Her depression further exacerbated the frequency of the intrusions and of her strategic responses.

Hypotheses

It was hypothesised that participation in a course of CBT for OCD that incorporated an extended period of assessment and longitudinal formulation would primarily improve engagement with treatment. As a result of improved engagement, it was hypothesised that this would lead to: (1) a decrease in severity of OCD symptoms and the time occupied by such on a daily basis, (2) an improvement in overall functioning, and (3) an improvement in mood.

Course of therapy

Therapist details

The therapist was a second-year trainee clinical psychologist who received weekly supervision from experienced clinical psychologists. Therapist adherence and skill was assessed by the Cognitive Therapy Scale – Revised (CTS-R) (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Baker, Standart, Garland and Reichelt2001) and the therapist received an overall score within the competent range.

Treatment

Treatment consisted of 15 sessions of individual CBT over a period of 25 weeks and fell into two main phases (see Table 2).

Table 2. Total (and mean) scores and reliable and clinical change information for standardised measures by treatment (Tx) stage

The overall aim of treatment was to help Anna to build a less-threatening explanation of her problems. All elements of the treatment were designed to test out two opposing theories of her difficulties:

Theory A (a problem of contamination): ‘I am a sitting duck to germs and if I don’t act to prevent danger of contamination, then I will get ill and I won’t be able to control it.’

Theory B (a problem of worry): ‘I am super-sensitive to worries about germs and therefore I worry that I am responsible and that I should be able to control harm from germs coming to myself and others.’

To address engagement issues, an extended period of assessment and formulation (treatment phase 1) was built into the CBT for OCD programme (Bream et al., Reference Bream, Challacombe, Palmer and Salkovskis2017). The first significant element of this extended phase was focused on validating Anna’s distress at entering a public area, which she perceived as a ‘huge barrier to therapy’ and then agreeing temporary measures to support her in doing this. The therapist made a contract to meet her outside the clinic door and open it for her on a strictly limited number of occasions. As rapport continued to build through therapist validation and normalisation of her experiences; the therapist and Anna made a new contract that focused on not colluding with her OCD. The second element of this phase was extended collaborative formulation work with an increased focus on helping Anna and the therapist to understand how her OCD had developed and how it was being maintained. As Anna felt so unsure of ‘which bit is me and which bit is OCD?’, increased time was allowed to: do socialisation to the CBT for OCD model, to build up a fledgling theory B, to do cost/benefit analysis to increase motivation to change, and to do cognitive work to help Anna to distinguish obsessions from compulsions.

By the end of treatment phase 1, Anna said she was now prepared to test out living life as if theory B were true. Throughout phase 2 weekly behavioural experiments (in clinic, field trips, and for homework) were conducted to help Anna to test her predictions regarding over-estimation of threat and perceived intolerability of anxiety. Initially Anna struggled to tolerate high levels of anxiety, so the therapist and Anna spent time on psychoeducation about anxiety and threat appraisal. This laid the groundwork for experiential work where Anna was able to gain her own bodily experience of how anxiety decays naturally in the absence of her safety strategies and neutralising behaviours. With therapist modelling, from session 9 Anna was able to progress to completing challenging ‘anti-OCD’ behavioural experiments (e.g. touching clinic door and eating a biscuit, touching supermarket self-checkout machine and licking hand). In later sessions Anna enjoyed planning her own behavioural experiments with minimal therapist input (responsibility was faded to reduce potential reassurance effects).

Guided discovery of how OCD works was facilitated by the use of therapeutic metaphors (e.g. the OCD bully, taking a leap of faith, choosing two mountain paths, helping a friend with fear of heights) (Bream et al., Reference Bream, Challacombe, Palmer and Salkovskis2017; Stott, Reference Stott2010). Anna invented her own vivid metaphors of OCD as a weed (‘it shrivels up if I don’t feed it’) and a trickster (‘I can now see through OCD’s illusions’) which enabled her to externalise the obsessive problems. It was, however, only in the later stages of therapy that Anna was fully able to re-conceptualise her mental rituals as ‘not me, but part of OCD’ (which she had previously viewed as a shameful aspect of her personality).

In session 11 the formulation was revisited to derive a collaborative understanding of why Anna’s distress was being maintained despite a noticeable reduction in her OCD behaviours. This work identified the need to address: (a) the thought–action fusion underpinning her entrenched mental ritualising, and (b) responsibility and control beliefs. Responsibility pie charts and continua techniques were used to challenge Anna’s responsibility appraisals, but Anna’s beliefs only shifted minimally. Additional behavioural experiments were introduced to address thought–action fusion (‘if I wish it hard enough, I can cause something to happen’). Whilst Anna was able to introduce some minor changes to her entrenched mental rituals (e.g. delaying start time by 5 minutes), these largely remained intact, provoking a therapeutic discussion of the ‘head-to-heart dilemma’ and homework exercises using the ‘acting-as if’ technique. On identifying the work to be done here, unfortunately the time available to focus on this part of the intervention was very limited. This was due in part to the therapist’s placement coming to an end and a lack of provision within the service for the number of therapy hours to be extended beyond the routine course. Sessions 14 and 15 were therefore used to review therapy and complete an OCD blueprint. This work included creating a plan for how Anna could continue to gain more experiential learning to internalise her belief in theory B, which had increased over the course of therapy from 35 to 65%. Therapy ended after 15 sessions and the patient was discharged from the service.

Results

Engagement and therepeutic rapport

Anna completed 15 sessions of treatment with a 95% attendance rate. She demonstrated good engagement with all exposure-based homework tasks. Anna was able to engage fully in challenging field trips and behavioural experiements by identifying subtle safety-seeking behaviours and choosing to let the overt behaviours go; however, she was unable to drop her mental rituals. Anna also maintained a detailed therapy diary which including reflections on her experiential learning.

Patient feedback indicated there was initially a poor therapeutic alliance. After session 1, Anna reported to her care coordinator that she felt her concerns about attending the clinic ‘fell on deaf ears’. By the end of treatment phase 1, Anna reported: ‘I feel that you’re hearing me and that we’re on the same team now’. This improvement in the alliance was also confirmed by Anna’s score on the Session Rating Scale (SRS). Repeated use of the SRS indicated that the quality of the therapeutic relationship was maintained over the course of treatment (see Table 3).

Table 3. Total (and mean) scores and RCI for standardised measures

OCI-R, Obsessive Compulsive Scale-Revised (norms derived from Veale et al., Reference Veale, Lim, Nathan and Gledhill2016); PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (norms derived from Löwe et al., Reference Löwe, Kroenke, Herzog and Gräfe2004); GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (norms derived from Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006); WSAS, Work and Social Adjustment Scale; CORE-OM, Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation – Outcome Measure (norms derived from Evans et al., Reference Evans, Connell, Barkham, Margison, McGrath, Mellor-Clark and Audin2002); RAS, Responsibility Attitudes Scale; SRS, Session Rating Scale.

By the end of treatment Anna said she felt proud that she had achieved the majority of her SMART goals for therapy. She reported, ‘I’m winning, OCD is shrivelling up, and I’m getting my life back’.

OCD

Figure 2 displays the results of Anna’s OCD symptom monitoring. Anna’s scores were stable during the baseline phase. OCI-R scores increased gradually during the first and second treatment phase as Anna noticed more OCD symptoms; this occurred up until session 9. Figure 2 indicates a downward trend over the final 2 months of treatment, yet the standardised measures revealed no overall change (see Table 3).

Figure 2. Anna’s weekly scores on OCI-R for self-reported OCD symptoms. A score of over 21 indicates clinically signficant symptoms. Tx, treatment.

There were significant reductions in the duration and financial cost of Anna’s OCD rituals during the course of treatment (see Table 4). The ideographic behavioural measures captured small improvements in Anna’s handwashing and covert rituals. These gains had not been observed in her previous treatment. Further gains were made in her cleaning rituals, which Anna had already made some previous improvements in following her ERP treatment.

Table 4. Anna’s idiographic behavioural measures showing average ratings for a 1-week period pre- and post-treatment (Tx), with comparative historical data from pre- and post-ERP treatments

General functioning

Anna’s WSAS score decreased from the ‘moderately severe or worse psychopathology’ to the ‘less severe’ clinical classification range (see Table 3). Reliable but non-clinically significant change was seen on her CORE-OM score which decreased from ‘moderate-severe’ to a ‘moderate’ level of distress.

Mood

Figure 3 displays the results of Anna’s weekly mood monitoring. Anna’s scores were stable during the baseline phase. There was no clinically significant change or reliable change on the majority of the standardised measures (see Table 3), with the exception of the PHQ-9 which fell out of ‘caseness’ at multiple points including at post-treatment stage. As Anna was discharged from the service at the end of treatment, no follow-up data were available.

Figure 3. Anna’s weekly scores on the PHQ-9 (depression) and GAD-7 (anxiety) which both have a recommended clinical cut-off score of 10 or above. Tx, treatment.

Discussion

This formulation-driven CBT intervention enabled Anna to develop an understanding of her OCD, which importantly made sense to her and fitted with her previous experiences. The rationale for treatment stemmed from the shared understanding (formulation) and was thus plausible to Anna. This enabled Anna to begin to choose to change and to try the treatment out for herself. The use of behavioural experiments (which enabled Anna and the therapist to work together to collaboratively test out and find out ‘how the world works’) appeared to be a better fit for Anna, as opposed to the habituation model utilised in her previous ERP sessions. In this case the extended time allocated to assessment and the development of a longitudinal formulation appeared to be a good investment. For a patient presenting for her third course of treatment, it is understandable that there is likely to be an underlying narrative of doubt about the possibility of this treatment being different from the last. It appeared that taking an alternative stance and allowing for an exploration and normalising of this doubt was useful. It allowed space to identify what had previously not worked and to ensure that this was not repeated, helping to build therapeutic rapport. This was a key difference achieved from the CBT intervention in comparison with Anna’s two previous courses of ERP.

It was further hypothesised that if engagement with the treatment was successful, that therapeutic changes in OCD symptom reduction, general functioning and mood would follow. While changes in each of these areas were observed via the idiographic behavioural measures and in a well-validated measure of social functioning, this was not the case for the standardised OCD measure. There was no change in self-reported OCD symptoms. However, the reduction in time spent doing exhausting OCD rituals was highly meaningful to the patient who interpreted this as evidence that she was in the process of reclaiming her life. In addition, Anna’s self-reported mood measures fluctuated over the treatment but changes were not maintained by the end of the final treatment stage. Based on Anna’s qualitative feedback, it seems that the temporary improvement in Anna’s depression score was reflective of a growing sense of hope, which is perhaps also captured in the reduction seen on the global distress measure (CORE-OM).

This disparity between the gradual improvements in Anna’s level of functioning and her unchanged self-reported symptoms is important to consider. Whilst Anna reported a significant cognitive shift away from theory A towards theory B, she still described occasionally having a ‘foot in both camps’. Whilst Anna was able to reduce her overt OCD behaviours, her mental ritualising remained largely intact. For Anna, they represented ‘the ultimate safety net’, and thus they maintained her OCD, as would be predicted by the cognitive behavioural model of OCD (Bream et al., Reference Bream, Challacombe, Palmer and Salkovskis2017; Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis1999; Salkovskis et al., Reference Salkovskis, Wroe, Gledhill, Morrison, Forrester, Richards and Thorpe2000). A lack of change in her scores on the Responsibility Attitudes Scale (see Table 3) suggest that Anna’s over-inflated responsibility appraisals remained intact post-treatment. When the therapist revisited the formulation with Anna towards the end of the therapy sessions, it was identified that although she had slightly modified her appraisal of people’s ability to be in control of contracting illness, she persevered in believing that she had a ‘duty to prevent harm coming to others’. Consistent with Anna’s longitudinal case formulation, this appeared to be a deeply entrenched belief for Anna which for her was continuing to serve a protective function, while counterproductively maintaining her OCD.

Considering the longevity of this belief, the question of whether it is in fact feasible to expect a considerable shift in such a belief within 15 sessions needs to be considered. CBT for OCD is a short-term goal-focused therapy, but for patients who fall within the 38% of those who do not respond (Öst et al., Reference Öst, Havnen, Hansen and Kvale2015) to a standard course, do we need to consider if a longer course of therapy may be beneficial at this level of care, particularly when the patient is making slow but small steps forward? Studies are yet to systematically examine this proposal, but this may be useful to consider given the significant difficulties within the current health system with regard to stepping patients up the care pathway. To add to this consideration, Mancebo and colleagues found that under one-third of people ‘received an adequate “dose” of CBT sessions’ (Mancebo et al., Reference Mancebo, Eisen, Sibrava, Dyck and Rasmussen2011), thus depending on how ‘dose’ is defined this may be applicable to the current case. In addition, few studies have examined the long-term outcomes of CBT for OCD. However, one study which conducted a 2-year follow-up after group CBT for OCD found that at the end of the intervention a full remission was reported by 21.4% and partial remission by 52.4% (Braga et al., Reference Braga, Manfro, Niederauer and Cordioli2010). Full remission was found to be a significant protective factor against relapse. At the 2-year follow-up none of the patients who had achieved full remission had relapsed. However, 41.9% of those who had achieved partial remission had relapsed, with 85% of these occurring in the first year post-treatment (Braga et al., Reference Braga, Manfro, Niederauer and Cordioli2010). In this case, it is not possible to comment on whether the gains made regarding Anna’s level of functioning were sustained and built on post-therapy, as no follow-up sessions were offered and thus no follow-up measures were taken. However, given the findings of Braga et al. (Reference Braga, Manfro, Niederauer and Cordioli2010), Anna was not discharged in a position in which she was set up to succeed fully.

Given Anna’s engagement with therapy and particularly behavioural experiments, this case is suggestive of the value of offering extended assessment and formulation for patients who have previously had a negative experience with a purely ERP-based intervention. When Anna was asked to reflect on her experience after she attempted her first behavioural experiment in session 6, Anna said, ‘I never would have done that when we first met’. Given Anna’s previous reports that she struggled to understand the rationale for ERP, it is plausible that the enhanced focus on conceptualisation helped to build a rationale for the purpose of engaging in behavioural experiments that were emotionally demanding due to the incorporated element of exposure.

Clinical implications

This case reflects the challenges of balancing the limited therapy resources available in NHS secondary care services with the clinical necessity of building engagement with a patient who has not benefited from previous courses of therapy. Given Anna’s previous history of disengaging from ERP treatments, it seems likely that Anna may not have tolerated the anxiety involved in doing challenging behavioural experiments without protected time to establish a positive working alliance and shared understanding. We can only wonder what would have happened if Anna had been offered formulation-based CBT for OCD as her first-line treatment; conceivably it might have prevented her from going through the experience of ERP treatment ‘failure’. This case highlights the value of using individualised assessment to inform treatment decisions before first-line treatments are offered, but further research is clearly required to identify what patient factors might predict response to ERP compared with CBT for OCD treatment. Furthermore, this case serves as a reminder that in order for patients to be treated until remission of their OCD symptoms, they may require more time than the duration of a trainee placement or standard course of CBT.

Mental health services may wish to consider enhancing their training provision for therapists to help engage patients like Anna who have not responded to first-line standardised treatments. Particular emphasis should be given to the development of collaborative case formulation skills to inform a more tailored treatment. Brief training can be effective at ‘topping up’ therapist skills; for example, Zivor and colleagues found that therapist formulation skills were improved after completing just one training workshop on formulation in CBT for OCD (Zivor et al., Reference Zivor, Salkovskis and Oldfield2013a).

In addition, this case demonstrates the possible disparity between clinician-observed clinical gains and self-report measures that do not reflect these. It highlights the value of monitoring observable changes in behaviour and improvements in areas of functioning that matter to the patient. Regular review of these therapeutic changes may help a patient who is feeling hopeless to notice and celebrate their progress, in turn boosting their sense of self-efficacy as they learn to become their own OCD therapist. It also highlights the importance of utilising standardised measures to highlight areas where the patient has not made progress and thus that may be important to focus on in therapy.

Limitations

The OCI-R was chosen as the primary outcome measure due to its brevity; however, given the lack of change across all of Anna’s self-report measures, it is possible that a clinician-rated OCD symptom measure such as the Y-BOCS would have reflected some clinical improvements. Whilst the OCI-R does have good sensitivity to change, research has indicated it is not as sensitive to change as the Y-BOCS (Veale et al., Reference Veale, Lim, Nathan and Gledhill2016).

It is also important to consider the possibility that the extra sessions dedicated to the extended assessment and formulation came at the cost of completing all the core components of CBT for OCD in sufficient depth, particularly regarding responsibility appraisals. However, it is also possible that Anna would not have tolerated starting the intervention phase without this enhanced period of engagement and that the previous difficulties encountered with ERP would have been perpetuated.

Therapist reflections

When I (E.C.) discussed writing up this case study with Anna in the final stages of the intervention, Anna said that she wanted other therapists to understand how important it was that we spent extra time at the start of treatment helping her to understand more about how OCD works and how to challenge it. Anna explained how beguiling OCD was, because it made her feel that the OCD rituals were a ‘part of me’ rather than a ‘part of OCD’. It only emerged in the later stages of therapy, though, that Anna had still persevered in believing that her covert rituals were part of her personality. She disclosed that she had felt too ashamed of this to feel able to discuss it with me when she felt we were still getting to know each other.

On reflection, it would have been useful to have spent more time on normalising covert rituals earlier in Anna’s treatment. I could have discussed the ambiguous relationship that people with OCD may have with their covert rituals such as feelings of shame or embarrassment, and then incorporated this into Anna’s formulation. I have learned that this struggle to distinguish between internal experiences can make covert rituals a particularly challenging aspect of OCD to work with, but that they can begin to be addressed once a strong therapeutic relationship is established.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Anna (pseudonym) for generously giving her consent for this case study to be published. Many thanks to the two anonymous reviewers for their feedback and also to Dr Emma Griffiths for commenting on an earlier draft of this article.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for profit sectors. This study was completed as part of the first author’s Doctorate in Clinical Psychology training at the University of Bath.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest with respect to this publication.

Ethical statement

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the APA. Ethical approval was not necessary as the case study was a standard application of routine clinical practice.

Key practice points

(1) An extended period of assessment and formulation may be useful in enabling a patient to understand the rationale for treatment and to develop a less threatening understanding of ‘how OCD works’. This may be particularly important for patients who have undertaken previous courses of therapy, but have not benefited due to difficulties with ‘engagement’.

(2) This enhanced conceptualisation, which may incorporate longitudinal work, can increase adherence to exposure tasks that the patient was previously unable to tolerate.

(3) CBT for OCD can enable a patient to reduce the duration and impact of their overt compulsions and consequently start to get their life back. However, if the patient does not address their covert rituals, and if their underlying responsibility and control beliefs remain intact, this is likely to maintain their OCD and require further intervention.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.