Introduction

Mindful of applying treatments grounded in psychological theory and supported by research, cognitive behavioural therapists are interested in applying evidence-based approaches to psychotherapy (EBPs) (APA Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice, 2006). Within the realm of EBPs, important questions around how to best orient these treatments to meet the unique needs of marginalized populations have emerged. Sexual and gender minority (SGM) individuals comprise one such marginalized group. Clinicians and researchers have begun to articulate best practices for effectively using EBPs with SGM individuals (American Psychological Association, 2021; American Psychological Association, 2015) across a range of clinical problems (see Pachankis and Safren, Reference Pachankis and Safren2019 for a review of these treatments).

Practice guidelines emphasize that recognizing the impact of stigma, discrimination, and minority stress is foundational to affirmative practice with SGM individuals (American Psychological Association, APA Task Force on Psychological Practice with Sexual Minority Persons, 2021). As a transtheoretical cognitive behavioural treatment that acknowledges contributions of an invalidating environment, dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) is evidence-based and has the capacity to target the invalidation that SGM clients encounter. This paper reports on a pilot DBT skills training group for SGM veterans at a Veterans Health Administration (VHA) outpatient clinic. Designed for SGM veterans who met criteria for DBT treatment at the VHA, DBT including Stigma Management (DBT-SM) explicitly approached minority-based stigma from a dialectical perspective, incorporating the use of DBT skills to effectively manage minority stress.

Contextualizing DBT for SGM individuals

Because DBT is a principle-driven rather than a manualized EBP, it possesses inherent flexibility in its application. DBT is grounded in a biosocial theory of emotion dysregulation (Linehan, Reference Linehan1993). This theory posits that the transaction over time of biologically based emotional vulnerability and an invalidating environment can result in difficulty regulating emotion effectively. Emotional vulnerability includes high sensitivity to emotional cues, high emotional reactivity, and a slow return to emotional baseline. An invalidating environment is characterized by persistent or inconsistent responses to primary adaptive emotion that communicate to the individual that their internal experiences (e.g. thoughts, emotions, urges) are unacceptable.

Over time, this transaction can lead to a host of difficulties including interpersonal problems, engaging in self-harm behaviour as an emotion regulation strategy, self-invalidation, and suicidal behaviour. DBT addresses this transaction by, among other things, teaching skills that are needed to regulate emotion and interact with the environment in such a way as to maximize the likelihood of the individual’s primary emotions being attended to and their needs being met (i.e. validated). As a transdiagnostic treatment, the core principles around which DBT is organized, particularly balancing acceptance and change, can be oriented to meet the needs of diverse populations without altering the essential functions of the treatment (Sloan et al., Reference Sloan, Berke and Shipherd2017).

The invalidating environment for SGM individuals

Minority stress theory suggests that managing stigma is a task that sexual minority (Meyer, Reference Meyer2003) and gender minority (Hendricks and Testa, Reference Hendricks and Testa2012) individuals navigate, given the existence of heterosexism and cisgenderism. Briefly, heterosexism refers to ideologies that stigmatize non-heterosexuality and cisgenderism to ideologies that stigmatize transgender and gender diverse (TGD) identities. Minority stress theory posits that proximal (internal) and distal (external) stress, including the anticipation of experiencing these stressors, create unique types of stress that SGM individuals must negotiate. Minority stress has been linked with a range of negative mental health outcomes (Meyer, Reference Meyer2003) including increased suicide risk (Dickey and Budge, Reference Dickey and Budge2020) and may also function as a source of ongoing traumatic stress for SGM individuals (Nadal, Reference Nadal2018). The model also suggests that protective factors such as enhanced coping skills and social support have the potential to influence the connection between proximal and distal stressors and mental health outcomes.

Herek et al. (Reference Herek, Gillis and Cogan2009) describe multiple levels of stigma at the cultural (structural stigma) and the individual (enacted, felt, and internalized stigma) levels. Structural stigma includes social structures that reinforce a heterosexual, cisgender norm. This includes policies such as ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ (DADT), laws that ban child adoption by LGBT parents, and religious messaging denouncing ‘homosexuality’. Enacted and felt stigma occur within an interpersonal context. When a person uses a derogatory term to describe queer or TGD people, this is an enacted stigma. Microaggressions, defined as everyday slights that communicate hostile or negative messages to the recipient (Sue et al., Reference Sue, Capodilupo, Torino, Bucceri, Holder, Nadal and Esquilin2007), are examples of enacted stigma. Felt stigma happens when an individual feels shame, for example, after experiencing an enacted stigma or feels fear going into a situation where they anticipate that they may experience a microaggression. Finally, internalized stigma describes an individual’s personal acceptance of the negative messages communicated via the other levels of stigma.

Stigma, heterosexism and cisgenderism contribute to an environment for SGM individuals that is reminiscent of Linehan’s (Reference Linehan1993) description of an emotionally invalidating environment. In fact, Linehan (Reference Linehan1993) points to cultural sexism as an example of an invalidating environment for women. She describes how an emotionally vulnerable individual’s ongoing transaction with an invalidating environment may result in them accepting the invalidating messages about themselves, which she terms self-invalidation. SGM individuals encounter invalidation through interaction with other people as well as environmental structures, and these experiences connect with potential internalization of negative messages into an individual’s sense of self (i.e. internalized stigma). In both cases, there is a hypothesized process occurring whereby an individual’s transaction with external invalidation (or stigma) facilitates internalization, and internalized stigma is a well-documented risk factor for mental health problems and suicide risk (Newcomb and Mustanski, Reference Newcomb and Mustanski2010).

Applicability of a dialectical approach to stigma management for SGM individuals

The parallels between DBT’s biosocial theory of emotion dysregulation and minority stress theory are noteworthy, given that these perspectives share a transactional approach between an individual (including their internal experiences) and a potentially invalidating environment. For SGM individuals who need DBT treatment, intentionally addressing how to use DBT skills to manage stigma makes sense as a way to ameliorate the effects of minority stress. Because DBT balances acceptance and change, its approach and skills can be uniquely synthesized to address experiences of stigma. The modules of skills taught in DBT fall into this dialectic: Core Mindfulness (CM) and Distress Tolerance (DT) on the acceptance side and Emotion Regulation (ER) and Interpersonal Effectiveness (IE) on the change side. Both are needed when dealing with stigma (Sloan et al., Reference Sloan, Berke and Shipherd2017).

For example, one homework assignment shared in the current DBT-SM group was being addressed by others using the wrong name (which occurred multiple times including when applying for jobs) (enacted stigma). This resulted in the participant experiencing shame in the moment and apprehension going into future social situations due to expectations that it would happen again (felt stigma). Urges to avoid applying for jobs were present (felt stigma). The participant was unable to legally get their name changed because this was cost prohibitive (structural stigma). Following such interactions, the participant would experience a cascade of self-invalidating thoughts, such as ‘Maybe I should just give up this whole thing … maybe everyone was right and this is all in my head’ (internalized stigma).

In a situation such as this, a balance of acceptance- and change-focused skills are called for (Skerven et al., Reference Skerven, Whicker and LeMaire2019; Sloan et al., Reference Sloan, Berke and Shipherd2017). CM skills (acceptance) can be used to observe and then accurately describe what happened (e.g. ‘that was a microaggression’ vs ‘that happened because there is a problem with me’). Adopting a non-judgemental stance toward self and the other person may be helpful. In the moment, DT skills (acceptance) can be incorporated to bring down distress and to move towards radical acceptance of the situation as it is in the current moment. ER skills (change) such as opposite action to shame might be called for in addition to problem-solving ways to fund the necessary legal work for a name change. Finally, IE skills (change) can be used to make the wise-minded request for others to use the proper name, perhaps validating their struggle to do this as well as the inherent wisdom of the participant. The skills of recovering from invalidation and engaging in self-validation are also relevant in situations like this.

Of course, any number of combinations of skills could be effectively used in this type of situation; the point is that approaching stigma management using a dialectical framework can be extremely beneficial (Sloan et al., Reference Sloan, Berke and Shipherd2017). In DBT, case formulation, treatment and use of skills are all approached from a dialectical perspective. Interestingly, at the end of the group participants were asked to identify the one skill that they thought was most helpful. Their four responses fell neatly onto the two sides of the dialectic: wise mind (acceptance), self-validation (acceptance), interpersonal effectiveness (change), and check the facts (change).

Unique intersections and risk factors for SGM veterans

Similar to how the minority stress model hypothesizes general stress plus identity- and environmentally related stress, SGM veterans are uniquely marginalized given that their sexual orientation and gender identity exist within a military context that has historically stigmatized SGM identities. For example, DADT defined official U.S. policy as essentially barring any openly non-heterosexual individual from military service. Such inequities have persisted, particularly with regard to transgender identities (Aford and Lee, Reference Aford and Lee2016). More recently, the Trump Administration in 2017 moved to ban transgender individuals from openly serving. The American Psychological Association actively opposed the 2017 ban, stating ‘As psychologists, we oppose discrimination that has no basis in science’ (American Psychological Association, 2019). The unique intersections of sexual orientation, gender identity and military service brings together distinct risk factors for mental health problems and suicide.

Beyond the veteran population, SGM individuals generally have increased risk for suicide and self-harm. King et al. (Reference King, Semlyen, See Tai, Killaspy, Osborn, Popelyuk and Nazareth2008) reported higher risk for suicidal ideation and self-harm for lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) individuals compared with heterosexuals. Among TGD individuals, Herman et al. (Reference Herman, Brown and Haas2015) reported that 81.7% endorsed lifetime serious ideation and 40.4% had attempted suicide. Further among TGD individuals, Morris and Galupo (Reference Morris and Galupo2019) found that 78.8% of their sample engaged in self-harm by cutting. A unique study using ecological momentary assessment revealed that for SGM participants, daily discrimination predicted momentary increases in anxiety and depression (Livingston et al., Reference Livingston, Flentje, Brennan, Mereish, Reed and Cochran2020).

Similarly, veterans carry increased suicide risk, prompting the adoption of local Suicide Prevention Coordinators at all VHA Medical Centers and a national 24-hour crisis line available to suicidal veterans. In 2013 and 2014, an average of 20 veterans died by suicide daily with about 67% being by firearm (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2017). Several VHA Medical Centers offer DBT to veterans (Landes et al., Reference Landes, Decker, McBain, Goodman, Smith, Sullivan, Spears, Meyers and Bedics2020). These DBT programmes have demonstrated reductions in suicide and self-harm among women veterans with borderline personality disorder (Koons et al., Reference Koons, Robins, Tweed, Lynch, Gonzalez, Morse, Bishop, Butterfield and Bastian2001), suicidal ideation and emotion dysregulation (Decker et al., Reference Decker, Adams, Watkins, Sippel, Presnall-Shvorin, Sofuoglu and Martino2019), and suicidality while combining DBT with prolonged exposure for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Meyers et al., Reference Meyers, Voller, McCallum, Thuras, Shallcross, Velasquez and Meis2017). Additionally, these DBT programmes have decreased service-utilization, resulting in lower treatment costs (Meyers et al., Reference Meyers, Landes and Thuras2014).

Landes et al. (Reference Landes, Decker, McBain, Goodman, Smith, Sullivan, Spears, Meyers and Bedics2020) provide an overview of VHAs that offer stand-alone DBT skills training groups for a general clinical population (e.g. transdiagnostic skills training group, skills training group for depression, and drop-in distress tolerance skills training group). Where reported, results indicated strong acceptability of these stand-alone groups. While they should be interpreted with caution, results across these studies included decreased depression, increased quality of life, decreased crisis events, and success with including safety planning as a group component. In fact, because of the increased risk for suicide via firearm among the veteran population, a DBT module has recently been created to assist veterans in applying DBT skills and principles to facilitate gun safety counselling (Jackson and Gaona, Reference Jackson and Gaona2019).

Trends in suicide risk for veterans overall also hold true for the population of SGM veterans that occupy the intersection of sexual orientation, gender identity, and military service. Higher lifetime suicidal ideation has been reported among LGB veterans compared with their heterosexual counterparts (Blosnich et al., Reference Blosnich, Mays and Cochran2014b). In a national sample of transgender veterans, 57% reported suicidal ideation (past year) and 66% reported having had a suicide plan or attempt (lifetime) (Lehavot et al., Reference Lehavot, Simpson and Shipherd2016). Brown and Jones (Reference Brown and Jones2016) reported significant disparities between transgender-identifying veterans compared with matched controls for depression, suicidality, serious mental illnesses, and PTSD.

The rate of suicide among TGD veterans has been found to be higher than the suicide rates in the VHA overall as well as in the U.S. population (Blosnich et al., Reference Blosnich, Brown, Wojcio, Jones and Bossarte2014a), making this group particularly high risk. Relatedly, TGD veterans report higher frequencies of potentially traumatic events, with about 40% reporting that at least one such event was transgender bias-related (Shipherd et al., Reference Shipherd, Maguen, Skidmore and Abramovitz2011). Carter et al. (Reference Carter, Allred, Tucker, Simpson, Shipherd and Lehavot2019) also noted that for TGD veterans, discrimination was positively correlated with suicidal ideation (Carter et al., Reference Carter, Allred, Tucker, Simpson, Shipherd and Lehavot2019). Furthermore, these authors highlight the need for mental health treatments that address stigma: ‘… interventions targeting discrimination or responses to discrimination’ (p. 43).

DBT skills group including stigma management (DBT-SM)

Because of its dialectical approach, targeting of the invalidating environment, and strong outcomes in treating suicidal and self-injurious behaviour (Linehan et al., Reference Linehan, Comtois, Murray, Brown, Gallop, Heard, Korslund, Tutek, Reynolds and Lindenboim2006), DBT is a fitting treatment for SGM veterans who struggle with these types of problems (for a review of literature on using DBT to treat suicidality for SGM populations, see Pantalone et al., Reference Cohen, Newman, Pachankis and Safren2019). Reflecting this, Cohen and Newman (Reference Cohen, Newman, Pachankis and Safren2019) developed a skills training group called Affirmative DBT Skills Training for sexual minority veterans. Their group was piloted with six LGB veterans but did not include TGD participants. It also focused on core mindfulness and emotion regulation skills (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Norona, Yadavia and Borsari2020). Described in the current paper, DBT-SM included both sexual and gender minority veterans and covered skills across all four DBT modules, making it a unique intervention for SGM veterans.

An emerging literature suggests that DBT skills group-only interventions can be effective, particularly for clients who do not have a personality disorder diagnosis (Neacsiu et al., Reference Neacsiu, Eberle, Kramer, Wiesmann and Linehan2014; Valentine et al., Reference Valentine, Smith, Stewart and Bedics2020). For example, a pilot randomized controlled trial (Neacsiu et al., Reference Neacsiu, Eberle, Kramer, Wiesmann and Linehan2014) comparing a stand-alone skills training group (DBT-ST) with an activities-based support group showed that DBT-ST was superior in decreasing emotion dysregulation, increasing skills use, and decreasing anxiety in participants with anxiety and/or depression (and not a personality disorder). Given this, a stand-alone group format was chosen for DBT-SM in order to gauge its acceptability and its effects on daily skills use and problems with emotion regulation, depression, and the burden of stigma-related experiences.

At this VHA there is a robust DBT programme that includes comprehensive DBT as well as a skills group-only track; the programme is open to all veterans receiving care at the VHA. Comprehensive DBT includes the components of individual DBT, skills training group, telephone consultation, and consultation team meetings for the DBT therapists. The DBT-SM pilot was embedded within the skills group-only track of the existing DBT programme. Participants learned typical DBT skills along with material explicitly addressing stigma. Information on participant selection and group materials is provided below.

Method

Participants

The DBT-SM group was conducted at a VHA Medical Center outpatient clinic; it was open only to SGM veterans. Providers make referrals to the general DBT programme within the electronic health record, and then all referrals are screened by a trained member of the DBT team to determine best fit (e.g. comprehensive DBT vs skills group-only). Screenings are individual sessions that assess symptoms falling into the areas of dysregulation targeted by DBT: emotional (e.g. high intensity or labile emotions), behavioural (self-harm, substance misuse), sense of self (e.g. chronic emptiness), cognitive (e.g. periods of paranoia), and interpersonal (e.g. chaotic relationships). All participants in DBT-SM were screened to be appropriate for DBT, demonstrating symptoms falling into the areas of dysregulation described above. Had the DBT-SM group not been in existence, participants would have been assigned to the DBT skills group-only track of the programme. The group began with six participants and two dropped out to seek a higher level of care, leaving a total of four participants completing the DBT-SM group. Two participants identified as a sexual minority and two as a gender minority.

Group format and materials

Because the authors sought to clarify the acceptability and effectiveness of DBT-SM, an abbreviated group format was chosen. The group followed the Schedule 3 curriculum described by Linehan (Reference Linehan2015; p. 113) that was researched by Soler et al. (Reference Soler, Pascual, Tiana, Cebria, Barrachina, Campins, Gich, Alvarez and Perez2009). Schedule 3 is an abbreviated (13-week) skills training group shown to effectively reduce symptoms such as depression and anxiety. Skills across all four modules are included. The DBT-SM group met weekly and followed the same format of all DBT skills training groups (mindfulness practice, homework review, teaching of new skill). Facilitators included two intensively trained VHA psychologists and two psychology practicum students who had at least 1 year of previous training in a community-based comprehensive DBT programme that was certified by the DBT-Linehan Board of Certification.

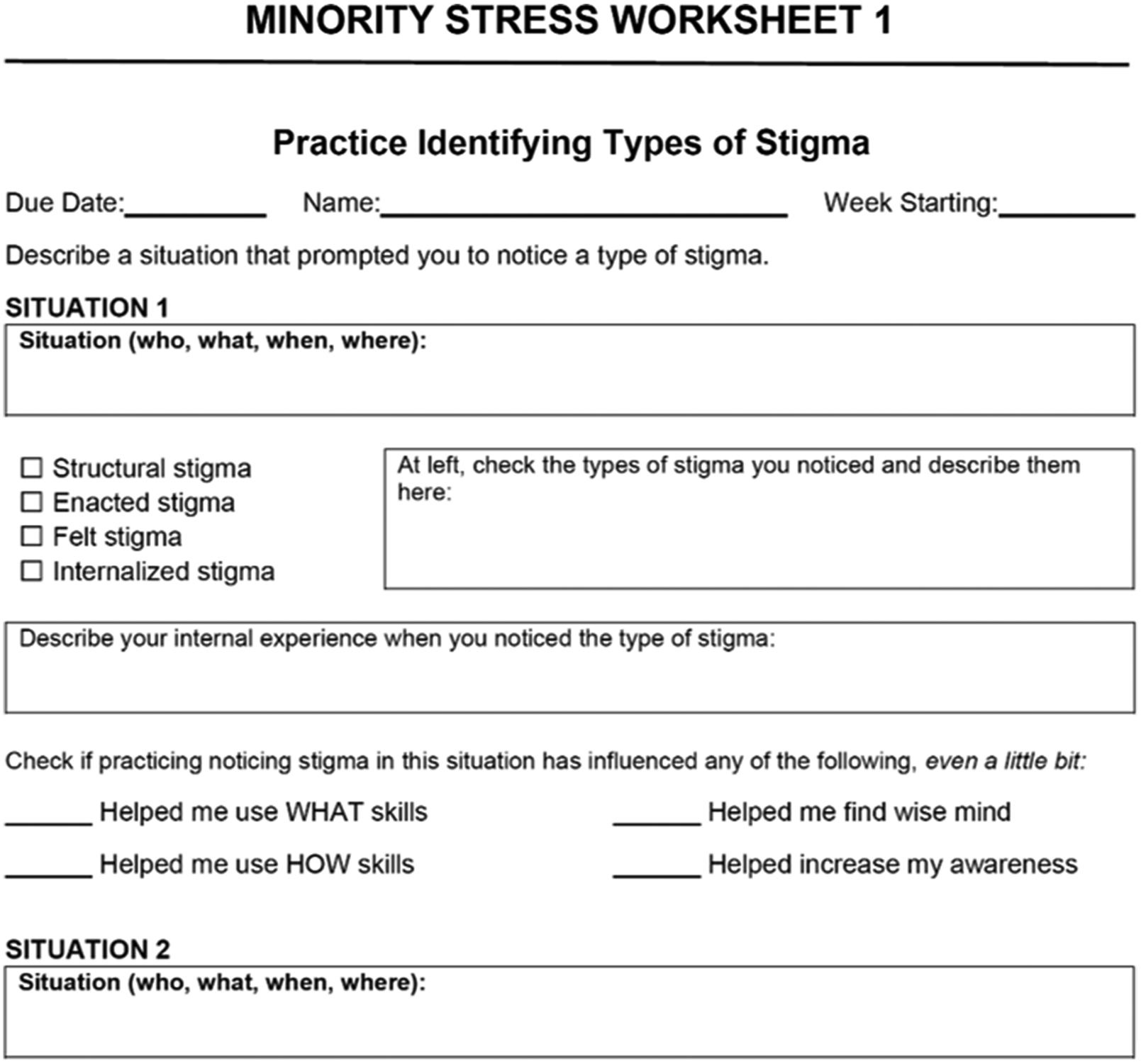

To the training schedule, additional lessons were included (see Table 1 for the complete schedule): newly created material on understanding levels of stigma and minority stress, along with existing skills related to dialectics to highlight ways to manage stigma from a dialectical perspective. Handouts (see Fig. 1 for an example) and homework sheets (see Fig. 2 for an example) were created describing Types of Stigma (Herek et al., Reference Herek, Gillis and Cogan2009) and Stressors Unique to Sexual and Gender Minorities (e.g. rejection sensitivity, concealment). The latter adapted material used by Cohen and Yadavaia in a DBT skills training group that they developed for sexual minority veterans (described in Cohen and Newman, Reference Cohen, Newman, Pachankis and Safren2019; Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Norona, Yadavia and Borsari2020). In teaching all of the skills, facilitators ensured that examples of using them to address stigma were included. For example, in teaching DEAR MAN (an IE skill used to ask for something or decline a request), one facilitator who openly identified as a sexual minority used an example of personally experiencing a microaggression during a professional interaction.

Table 1. Teaching schedule for DBT-SM

Handouts and worksheets that begin with MS (Minority Stress) were created for the group and are described in the Method section under the subsection Group format and materials. All other handouts and worksheets are from Linehan (Reference Linehan2015).

Figure 1. Example of minority stress handout: Types of Stigma.

Figure 2. Example of minority stress worksheet: Types of Stigma. Adapted from: Herek, Gillis, & Cogan (Reference Herek, Gillis and Cogan2009) and Cohen & Newman (Reference Cohen, Newman, Pachankis and Safren2019).

Measures

Participants provided information about their symptoms before and after participation in the DBT-SM group. All measures listed below were administered at both points. Additionally, written feedback on the group was collected at the final meeting.

Minority stress: Daily Heterosexist Experiences Questionnaire (DHEQ) (Balsam et al., Reference Balsam, Beadnell and Molina2013)

This instrument assesses participants’ stigma burden and is appropriate for all SGM individuals. There is an overall score and nine subscales: gender expression, vigilance, parenting, discrimination/harassment, vicarious trauma, family of origin, HIV/AIDS, victimization, and isolation. There are 50 items scored from 0 to 5, with higher scores associated with more distress (0, did not happen/not applicable to me; 1, it happened, and it bothered me not at all; 2, it happened, and it bothered me a little bit; 3, it happened, and it bothered me moderately; 4, it happened, and it bothered me quite a bit; 5, it happened, and it bothered me extremely). Higher scores indicate greater distress.

Emotion dysregulation: Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) (Gratz and Roemer, Reference Gratz and Roemer2004)

This measure assesses overall difficulties with regulating emotion along with six relevant subscales: non-acceptance of emotional responses, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviour, impulsive control difficulties, lack of emotional awareness, limited access to emotion regulation strategies, and lack of emotional clarity. There are 36 items scored from 1 to 5, with higher numbers indicating greater difficulties in that area.

Depression: Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Kroenke and Spitzer, Reference Kroenke and Spitzer2002)

This measure gauges the severity of depression symptoms over the past 2 weeks. There are nine items scored from 0 to 3, with higher numbers indicating greater symptoms. Item 9 (‘Thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way’) can be used to gauge suicidality/self-harm.

DBT skills use: the DBT Ways of Coping Checklist (WCCL) (Neacsiu et al., Reference Neacsiu, Rizvi, Vitaliano, Lynch and Linehan2010)

This instrument assesses participants’ methods of coping with stressors. There is one subscale that measures strategies consistent with DBT skills and two that measure dysfunctional strategies over the past month (general dysfunctional coping and blaming others). There are 59 items scored from 1 to 3, with higher numbers indicating more use of the particular strategy.

Data analysis

Due to small sample size (n = 4), changes examined in the study are for exploratory purposes. Clinically significant reliable change for each participant was examined independently using the reliable change index (RCI; Jacobson and Truax, Reference Jacobson and Truax1991). Normative data used to calculate the RCI (standard deviation, internal consistency, standard error of measurement; SEM) were collected from the original measure articles described above. The RCI standardizes difference scores between Time 1 and Time 2 using SEM of the measure. An RCI cut-off of ±–1.96 (α = .05) was used to determine clinically significant reliable change.

Results

Endorsed levels of wanting to be dead, as measured by the PHQ-9 item 9 question, were generally low before and after the group. They were as follows: Participant 101 (1 initial; 0.5 final), Participant 102 (1 initial; 1 final), Participant 103 (0 initial; 0 final), Participant 104 (1 initial; 1 final).

Changes in symptoms

Statistically significant change using the RCI was examined for each participant separately. Only statistically significant changes are presented below; for full results including Time 1 and Time 2 measurements, see Table 2.

Table 2. RCI values for study measures by participant number

*p < 0.05, ‡p < 0.01, §p < 0.001.

Participant 101

Statistically significant reductions for Participant 101 (lesbian, cisgender participant) were observed for overall difficulties in emotion regulation (DERS total; RCI = –4.50, p < .001), difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviour (DERS difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviour; RCI = –2.13, p < .05), lack of emotional awareness (DERS lack of emotional awareness; RCI = –2.75, p < .01), and lack of access to emotion regulation strategies (DERS limited access to emotion regulation strategies; RCI = –3.62, p < .001).

A statistically significant increase was also observed for DBT skills use (WCCL DBT Skills; RCI = 3.60, p < .001). Additionally, a decrease in general dysfunctional coping (WCCL general dysfunctional coping; RCI = –6.37, p < .001) was observed.

For minority stress experiences, a significant decrease was observed for social isolation-related distress (DHEQ isolation; RCI = –2.17, p < .05).

Finally, a significant decrease in overall depressive symptoms was observed (PHQ-9; RCI = –3.09; p < .01).

Participant 102

Statistically significant reductions for Participant 102 (no sexual identity reported, transgender participant) were observed for overall difficulties in emotion regulation (DERS total; RCI = –4.63, p < .001), difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviour (DERS difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviour; RCI = –4.26, p < .001), impulse control difficulties (DERS impulsive control difficulties; RCI = –5.08, p < .001), and access to emotion regulation strategies (DERS limited access to emotion regulation strategies; RCI = –3.29, p < .001). For Participant 102, a statistically significant increase in non-acceptance of emotions (DERS non-acceptance of emotional responses; RCI = 5.98, p < .001) was observed.

A statistically significant increase was observed for DBT skills use (WCCL DBT Skills; RCI = 6.26, p < .001), as well as blaming others (WCCL blaming others; RCI = 2.43, p < .05). A decrease in general dysfunctional coping (WCCL general dysfunctional coping; RCI = –1.96, p < .05) was observed.

For minority stress experiences, a significant reduction in overall distress from minority stress experiences was observed (DHEQ total; RCI = –3.77, p < .001). Subscale reductions in distress related to gender expression (DHEQ gender expression; RCI = –4.91, p < .001), vigilance (DHEQ vigilance; RCI = –2.70; p < .01), and discrimination and harassment experiences (DHEQ harassment/discrimination; RCI = –4.08; p < .001) were also observed.

Finally, a significant decrease in overall depressive symptoms was observed (PHQ-9; RCI = –3.09; p < .01).

Participant 103

A statistically significant decrease in lack of emotional clarity was observed for Participant 103 (lesbian, cisgender participant) (DERS lack of emotional clarity; RCI = –3.29, p < .001). Statistically significant increases in self-rated non-acceptance of emotions (DERS non-acceptance of emotional responses; RCI = 4.38; p < .001), and impulse control difficulties (DERS impulsive control difficulties; RCI = 2.12, p < .05) were observed.

For minority stress experiences, a significant reduction in overall distress from minority stress experiences was observed (DHEQ total; RCI = –4.06, p < .001). Subscale reductions in distress related to vicarious trauma (DHEQ vicarious trauma; RCI = –6.39, p < .001) and social isolation (DHEQ isolation; RCI = –3.25, p < .01) were also observed.

Finally, a significant decrease in overall depressive symptoms was observed (PHQ-9; RCI = –2.57; p < .05).

Participant 104

Statistically significant reductions for Participant 104 (bisexual, transgender participant) were observed for overall difficulties in emotion regulation (DERS total; RCI = –3.31, p < .001), difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviour (DERS difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviour; RCI = –2.13, p < .05), lack of access to emotion regulation strategies (DERS limited access to emotion regulation strategies; RCI = –2.96, p < .01), and lack of emotional clarity (DERS lack of emotional clarity; RCI = –2.35, p < .05).

A statistically significant increase was also observed for DBT skills use (WCCL DBT Skills; RCI = 2.86, p < .01). Additionally, decreases in general dysfunctional coping (WCCL general dysfunctional coping; RCI = –4.76, p < .001) and blaming others (WCCL blaming others; RCI = –2.43, p < .05) were observed.

Finally, a significant decrease in overall depressive symptoms was observed (PHQ-9; RCI = –4.63; p < .05).

Discussion

Promising trends were observed in overall symptoms, use of DBT skills, dysfunctional coping, and stigma-related distress. Additionally, based on participant feedback, the authors learned helpful information regarding the value of offering this type of DBT group. Below, acceptability of the group is discussed followed by the group’s impact on symptoms, skills use, and stigma-related experiences. Finally, potential future directions are addressed.

Acceptability of the group

Anecdotally, participants expressed that because the group was only open to SGM veterans, it felt more meaningful and safer to share examples that created more vulnerability for them. In the words of one participant, it ‘… keeps the group within the tribe’. Another explained that ‘it was nice being able to feel comfortable enough and in a “safe” environment with different issues that we could freely talk’. Participants shared appreciation for the ‘common ground’ that they shared in the group.

Feedback at the end of DBT-SM was overwhelmingly positive. When asked how valuable on a 1–5 scale (5 being extremely valuable) the group was, the mean response was 4.5. Three out of four participants indicated that they wished there were more weeks that they could meet; one responded that they were satisfied with the number of weeks. When asked what to keep the next time the group was offered, responses were: ‘all of it’, ‘everything’, and ‘the same modules and the same staff’. When asked for suggestions to improve DBT-SM, the resounding response was wanting more.

All the facilitators had prior experience conducting standard DBT groups with no specific subpopulations, and as such were able to reflect on differences between those groups and DBTSM. During the post-group debriefing among the facilitators, it was identified that there were multiple examples of skills use shared in the DBT-SM group that had never come up in the non-specific groups they had facilitated. These examples included experiences of being targeted for verbal harassment, fear of being physically assaulted, being shunned by family members, and intimate relationship problems that none of the facilitators imagined would have been shared in general groups they had been involved with. It seems likely that the composition of the group played an important role in facilitating positive outcomes. This aligns with the minority stress theory (Meyer, Reference Meyer2003) proposition that social support has the potential to influence the connection between stigma-related stressors and mental health.

Symptoms, skills use, and stigma-related experiences

Depression symptoms as measured by the PHQ-9 significantly decreased from the initial to the final session for all participants. This is similar to results reported by Cohen et al. (Reference Cohen, Norona, Yadavia and Borsari2020) (four of six participants showed significant decreases on the PHQ-9) for their Affirmative DBT Skills Training group described above. Due to the small sample size and the fact that levels of suicidal ideation (PHQ-9 item 9) were low to begin with, it was difficult to gauge the extent that DBTSM alleviated suicidal ideation. Additionally, some reduction in emotion dysregulation (DERS) was observed for all participants, although results were mixed for Participant 103. This suggests that participants’ overall difficulty with regulating emotions decreased. For comparison, Cohen et al. (Reference Cohen, Norona, Yadavia and Borsari2020) reported a significant decrease in DERS scores for three of their six participants. General dysfunctional coping as measured by the WCCL decreased for Participants 101, 102 and 104, while coping by using DBT skills increased. A skills use measure was not reported by Cohen et al. (Reference Cohen, Norona, Yadavia and Borsari2020).

With regard to stigma-related experiences, overall distress decreased for two participants, reductions in distress specifically related to social isolation were observed for two participants, while one saw reductions in distress related to gender expression, vigilance, and harassment/discrimination (some participants demonstrated decreases in multiple categories). The current group showed levels of vicarious trauma and heterosexist discrimination (DHEQ Total) consistent with past samples (e.g. Balsam et al., Reference Balsam, Beadnell and Molina2013). These are promising trends considering that three of the four participants showed statistically significant reduction in at least one measure of minority stress. Cohen et al. (Reference Cohen, Norona, Yadavia and Borsari2020) utilized different measures of stigma-related experiences, reporting decreased rejection sensitivity in four of six participants, decreased internalized stigma in five of six, and decreased sexual orientation concealment in one of six participants. These results align with the minority stress theory (Meyer, Reference Meyer2003) idea that enhancing coping skills may help mediate the connection between stigma-related stressors and mental health.

The DBT-SM group included participants with different sexual orientations and gender identities, and therefore potentially different sources of minority stress experiences. Participants 101 and 103 identified as cisgender, while Participants 102 and 104 identified as transgender. This helps explain the differences in DHEQ scores on the gender expression subscale. It is also very possible that history effects played a role in the DHEQ scores; however, it is difficult to know exactly how. This is because the DBT-SM group took place in a historical time when a great deal of media attention was being given to proposals by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that would result in weakening discrimination protections for SGM individuals. Also occurring was media attention on the proposal to ban transgender individuals from military service. These and similar events would often be brought up by group members, and they contribute to structural stigma.

Future directions

This report described a pilot DBT-SM group to determine its acceptability and its effects on symptoms, skills use, and the burden of stigma-related experiences. Due to the small sample size, it is possible that, while promising trends were observed, many changes did not reach statistical significance. As such, future iterations of DBT-SM using a larger group may be better able to detect statistically significant group differences rather than examining individual differences, which may be highly influenced by individual participants’ contexts. It seems likely that using a DBT-SM approach in a non-abbreviated, standard DBT skills training group could be even more beneficial for SGM veterans who would generally benefit from standard DBT. This is especially critical in the area of detecting changes in suicidal ideation, given the multiple risk factors carried by this population.

There has been increased attention in the literature to culturally competent applications of EBPs with diverse populations. A recent text by Pachankis and Safren (Reference Pachankis and Safren2019) includes a range of chapters on using evidence-based mental health interventions with SGM individuals, including a chapter on DBT as well as treatments for anxiety, depression and substance misuse. They state: ‘today represents the first time in history that a critical mass of empirical evidence exists regarding suitable treatment goals and delivery methods for SGM-affirmative mental health practice’ (Pachankis and Safren, Reference Pachankis and Safren2019; p. 1), highlighting the growing need to develop effective ways of using EBPs that incorporate minority stress theory (Meyer, Reference Meyer2003). It is both timely and critical.

Minority stress theory posits that enhanced coping and social support may ameliorate some of the negative stress effects and bolster potential for resilience (Meyer, Reference Meyer2015). The DBTSM group enhanced coping by teaching how to use DBT skills to manage stigma and provided social support because its members were all SGM veterans, lending to its high level of acceptability among participants. Overall, using a dialectical approach to managing stigma offers promise, aligns with theoretical models of minority stress, and provides practitioners with a concrete way to contextualize an EBP to meet the needs of SGM veterans.

Key practice points

-

(1) As a principle-driven treatment, dialectical behaviour therapy can be effectively contextualized depending upon the specific needs of each client.

-

(2) Contextualizing dialectical behaviour therapy to meet the unique stressors that sexual and gender minority veterans face can be effective in decreasing mental health symptoms and increasing the ability to manage stigma.

-

(3) Dialectical behaviour therapy including stigma management shows promising effects in terms of reducing psychological distress and increasing skills use.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

None.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare none.

Ethics statement

This project was internally reviewed and confirmed as an operations activity as defined in the VHA Program Guide 1200.21.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, K.S. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of participants.

Author contributions

Kim Skerven: Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (lead), Investigation (lead), Project administration (lead), Writing-original draft (lead); Lucas Mirabito: Conceptualization (supporting), Data curation (supporting), Formal analysis (lead), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Writing-review & editing (supporting); Mackenzie Kirkman: Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Project administration (supporting), Writing-review & editing (supporting); Beth Shaw: Conceptualization (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Project administration (supporting), Writing-review & editing (supporting).

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.