Introduction

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) is an extensively studied and well-established treatment for depression (Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Berking, Andersson, Quigley, Kleiboer and Dobson2013; Gloaguen et al., Reference Gloaguen, Cottraux, Cucherat and Blackburn1998). However, CBT has been criticised for being west-centric and grounded in an ‘ineffably western version of a person’ (Summerfield and Veale, Reference Summerfield and Veale2008). For example, as Hays (Reference Hays1995) stressed, assertiveness, personal independence, verbal ability and change are highly valued in the United States. However, these are far from universal priorities in other parts of the world. Similarly, Laungani (Reference Laungani2004) asserted that eastern cultures could be described in terms of collectivism, religiosity, determinism, emotionalism and spiritualism, while western culture is contradictory to these values. Therefore, values that underpin CBT may be inconsistent with the values and beliefs of clients from non-western cultures.

Culture influences many facets of mental health including the explanatory model of illness, the style of coping, willingness to seek help and other health-related behaviours and beliefs (El Rhermoul et al., Reference El Rhermoul, Naeem, Kingdon, Hansen and Toufiq2018; Joel et al., Reference Joel, Sathyaseelan, Jayakaran, Vijayakumar, Muthurathnam and Jacob2003; Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Phiri, Nasar, Munshi, Ayub and Rathod2016). Moreover, every aspect of the cognitive model, from early experiences, core beliefs, assumptions to how an individual views oneself in family and community context is influenced by culture (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015). Therefore, culture must be at the heart of all interactions with clients (Alladin, Reference Alladin2009; Laungani, Reference Laungani1997; Moodley et al., Reference Moodley, Rai and Alladin2010). Previous studies have shown that cultural differences can influence the process of therapy (Barrera et al., Reference Barrera, Castro, Strycker and Toobert2013; Edge et al., Reference Edge, Degnan, Cotterill, Berry, Baker, Drake and Abel2018; Rathod and Kingdon, Reference Rathod and Kingdon2014). Culturally adapted CBT has proved to be more effective than standard CBT and can reduce drop-outs and increase engagement in therapy (Hwang et al., Reference Hwang, Myers, Chiu, Mak, Butner, Fujimoto, Wood and Miranda2015; Kohn et al., Reference Kohn, Oden, Muñoz, Robinson and Leavitt2002). Griner and Smith (Reference Griner and Smith2006) found a moderate weighted average effect size (d=.45) in a meta-analysis of 76 studies that examined culturally adapted intervention. They found that therapies tailored to a specific cultural group were four times more successful than interventions delivered to groups of clients from diverse cultures. Another meta-analysis of 78 studies by Hall et al. (Reference Hall, Ibaraki, Huang, Marti and Stice2016) revealed that culturally adapted interventions produced substantially better outcomes in terms of reduction of symptoms than another intervention or no intervention. Rathod et al. (Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Smith and Turkington2005) expressed concern of clients’ disengagement if we continue to practise CBT in heterogeneous groups without adaptation because clients perceive that they or their culture are not understood. Using generic or standard CBT could obstruct in the cognitive and behaviour change process, especially if the therapist’s explanations for change contradict the client’s cultural models. The American Psychological Association (2017) in its new multicultural guidelines promoted the use of culturally adaptive interventions and emphasised that multi-cultural competence is necessary for psychologists working in all domains: practice, research, consultation and education.

There have been various attempts to make culturally adapted CBT for diverse populations in several Asian countries (Algahtani et al., Reference Algahtani, Almulhim, Alnajjar, Ali, Irfan, Ayub and Naeem2019; An et al., Reference An, Wang, Sun and Zhang2020; Husain et al., Reference Husain, Zulqernain, Carter, Chaudhry, Fatima, Kiran, Chaudhry, Naeem, Jafri, Lunat, Haq, Husain, Roberts, Naeem and Rahman2017; Li et al., Reference Li, Guo, Wang, Xu, Qu, Wang, Sun, Yan, Ng, Turkington and Kingdon2015; Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Gul, Irfan, Munshi, Asif, Rashid, Khan, Ghani, Malik, Aslam, Farooq, Husain and Ayub2015). There are published randomised controlled trials on effectiveness of culturally adapted CBT in countries like China, Pakistan and Malaysia. Kuruvilla (Reference Kuruvilla2000, Reference Kuruvilla2010) has highlighted that there is a paucity of original research in CBT in India. He suggested that there is a need for conducting large-scale evaluative studies to see what aspects of CBT are more relevant in Indian culture. Kumar and Gupta (Reference Kumar, Gupta, Naeem and Kingdon2012) recommended the use of an integrative approach that incorporates therapeutic elements of traditional Indian healing systems into the western models of psychotherapy and counselling to improve the efficacy and acceptability of treatments in the Indian setting. Selvapandiyan (Reference Selvapandiyan2020) asserted that although there has been a previous attempt to adapt CBT for India but in the process of adaptation, the Hindu sacred scripture Bhagavat Gita and the ancient Vedic literatures have been referred to interpret therapeutic ideas hidden in them and then a suggestion was made to integrate them in therapy. The by-product of this attempt was the insertion of the Guru-Chela (G-C) paradigm (guru is the mentor and chela are the disciples) into the psychotherapeutic procedures, which drastically changes the model of CBT. Therefore, many of the attempts to develop culturally sensitive CBT in India are found to be derived solely based on theory rather than grounded on actual data from cultural adaptation literature or from clinical practice. The present study is an attempt to locate the work of cultural adaptation on evidence-based framework and explore the views from the therapists and patients.

In the present study, the definition of cultural adaptation provided by Naeem (Reference Naeem2012) has been employed, i.e. ‘making adjustment in how therapy is delivered, through the acquisition of awareness, knowledge, and skills related to a given culture, without compromising on theoretical underpinnings of CBT’. We followed an evidence-based framework by Naeem et al. (Reference Naeem, Phiri, Nasar, Munshi, Ayub and Rathod2016) to culturally adapt CBT for depression. According to this framework, the process of culturally adapting CBT begins with stage 1 of gathering information from literature and experts in the field. Using qualitative methodology, the perspectives of various stakeholders are then examined. In the second stage, these data are analysed in order to develop guidelines for adapting an existing CBT manual to provide culturally appropriate CBT. The therapy materials are then translated in stages 3 and 4, which involve field-testing to allow further adjustments and refinement. This study reports finding from qualitative interviews as part of a stage 1 adaptation process in which information from CBT practitioners and patients undergoing CBT was gathered. The present study is part of a larger PhD work where CBT intervention based on the manual by Muñoz and Miranda (Reference Muñoz and Miranda1996) (‘Cognitive behaviour treatment of depression’) was used, and insights from these interviews were incorporated to deliver culturally sensitive interventions.

Method

Study design

The qualitative study consisted of semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions with clinical psychologists/therapists and patients. They were given choice of online video call or face-to-face interview. Patients were given choice of audio or video call for conducting interviews.

Development of semi-structured interviews

The interview schedules were developed using Triple-A Principle by Naeem et al. (Reference Naeem, Phiri, Nasar, Munshi, Ayub and Rathod2016). Questions and prompts were designed with the focus on (1) awareness of relevant cultural issues and preparation for therapy; (2) assessment and engagement; and (3) adjustments in therapy techniques. The semi-structured interviews were then reviewed by the second and third authors for language and scope of questions, and suggestions were incorporated. Some of the questions for therapists are listed below: under awareness of relevant cultural issues: What do patients understand about depression? What kind of religious/spiritual coping strategies do people use when dealing with depression? What common myths are often associated with depression in Indian context?

The questions on assessment and engagement were: How was your experience of using CBT for depession? How do you orient the client for therapy in culturally appropriate ways? Which therapy style works well in the Indian context? What structural modification can be made in therapy for depression considering our context? etc.

Questions regarding adjustments in therapy techniques were: Which techniques have you found useful for depression? Which techniques according to you need to be adapted/modified? How do you in practise elicit automatic thoughts and core beliefs? What are the commonly observed dysfunctional beliefs in the Indian context?

Similarly for patients, a few questions under each domain are: For what problems are you consulting here? What did you think of your problem when you first sought help? How is your experience of CBT for depression? Which techniques did you find particularly useful for your problem? What insight did you gather after therapy?

Participants

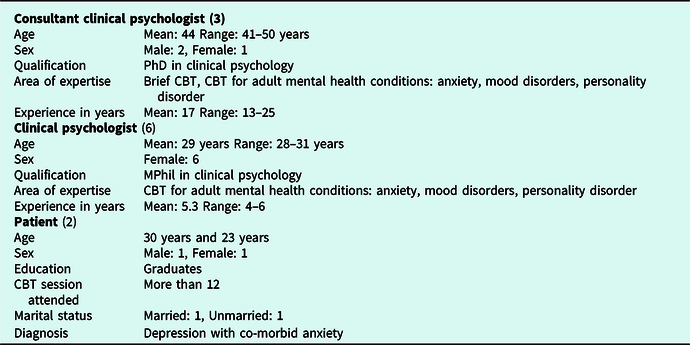

The participants were recruited using a purposive sampling method. The participants consisted of two groups. Group 1 (therapists) included three senior consultant clinical psychologists and six clinical psychologists. The consultant clinical psychologists had more than 8 years of clinical experience of treating clients with depression and anxiety disorders and the clinical psychologists had experience ranging from 3 to 8 years. Group 2 (patients) consisted of two adult patients having primary diagnosis of depression and having undergone eight or more individual CBT sessions. See Table 1 for characteristics of the participants and Table 2 for the inclusion criteria.

Table 1. Characteristics of participants

Table 2. The inclusion criterion of participants

Data collection

All participants were given information about the study and written informed consent was taken. The semi-structured interviews with therapists were conducted via online video call and one therapist preferred the option of a face-to-face setting. Patients preferred the interview to be conducted via audio call. All interviews were conducted between April and June 2020 and all participants were recruited from a public funded tertiary mental health hospital set up in Bengaluru, Karnataka. The total duration of five interviews was 6 hours and 10 minutes, with a range of 28 minute to 1 hour and 30 minutes. Focus group discussion with six clinical psychologists was 1 hour and 50 minutes long. All interviews were audio recorded with permission of participants, and transcribed. Anonymity and confidentiality were ensured. Interviews were conducted by the first author and checked for accuracy by the second author.

Data analysis

The participant interviews were ascribed numbers which were used in the transcription and report. The first author immersed herself in the data by carefully reading the interview scripts multiple times. The first author led the analysis and the second author reviewed each phase of the analysis with the first author in order to finalise the developing codes and themes. Interviews were analysed using the six-phase thematic analysis approach of Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006) which involved: familiarisation with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and producing the report. The data were primarily descriptive, so themes from literature review and focus on cultural adaptation were considered during analysis. After transcription, complete coding was done for the entire dataset, where the codes were identified and provided a concise label for the feature of the data. The second level of analysis involved reviewing these initial codes by the second author in order to retain the diversity of the initial codes, while producing over-arching elements, and higher level sub-themes. Finally, the codes were checked by all the authors. Once the themes were finalised, the write-up of the report began. Accordingly, authors collaborated to preserve the quality and rigor of the analysis, as well as to develop the final themes (Morrow, Reference Morrow2005).

Results

The analysis generated themes from the therapist and patient groups. However, the results are presented together for both the groups wherever the theme coincides, to make sense of complete meaning from patient and therapist perspectives. The themes were then grouped under Triple-A Principle as: (1) awareness of relevant cultural issues and preparation for therapy; (2) assessment and engagement; and (3) adjustments in therapy techniques (Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Phiri, Nasar, Munshi, Ayub and Rathod2016).

Awareness of relevant cultural issues and preparation for therapy

Four main themes were generated for awareness and preparation (see Table 3).

Table 3. Summary of themes, subthemes and codes under awareness of relevant cultural issues and preparation for therapy

Abbreviations used for the excerpts: T, therapist; P, patient.

One therapist reported:

I have found CBT effective for most of the clients with depression just that we have to adapt according to the socio cultural background of the client and also depending on the presentation of the client whether client has presented with only axis I disorder or client also have axis II disorder. [T1]

He further explained the difficulty in understanding model:

They are not able to understand the difference between thoughts and feelings that is the main difficulty… in differentiating thoughts from emotions from behaviour and understanding the relationship between the three so they are not able to comprehend… [T1]

Another therapist reported the problem encountered in complex co-morbid cases:

There are some clients who have additional personality disorders for whom it is not such an easy process. [T2]

One therapist explained about problem with premature drop-out:

Once patient improves or starts showing improvement he believes that I am doing well now. What’s the point for coming to therapy sessions now. [T3]

Importance of therapist cultural sensitivities is explained with example by another therapist:

For example, if a parent lives in rural India and son in an urban place due to job and son is unwilling to go home for a festival. Father may feel distress because of it. Because festival holds so much value for them, where all family members come closer, so context of feeling differ across living status. So we need to understand what it means for the person. There should be cultural sensitivity in therapists to understand and acknowledge it. [T3]

Many of my clients are from the similar backgrounds. And if they [clients] are not, some curiosity about where they come from. What are their practices, gaining knowledge and familiarity of the culture and willingness to learn from the therapist side is important … So, I think outside therapy, therapist has to do a lot of homework about understanding client practises, so that they are not taken aback nor do they pathologize some of the cultural context, then it just become easier to allow them to be. Also, you may not have to try and use the cultural context, I mean just out of the context of your work. [T2]

All therapists agreed that therapists should adapt the treatment depending on client presentation and socio-cultural background as need arises.

About perception of depression, both groups report that patients identify depression with interpersonal problems, negative thinking and feeling and a few with chemical imbalance and a large proportion not able to identify it as a medical illness:

Our clients have less awareness about depression being a mental illness, they would say that they are into lot of negative thinking or most of the clients say that their thinking has become negative. [T1]

I think depression is somehow like a label that actually represents all kind of mental illness. [T8]

Patients come to us through referral from the psychiatry team, their understanding of it depends upon how they were informed about their condition by the psychiatrist. Sometimes they come with understanding of biological imbalance or having interpersonal problems which come up as stressors and they want a problem solution as to how it can be solved. [T3]

One patient described depression as:

At first, I felt that something is happening to me, like … that there was a different feeling. In depression, the outside world does not feel good. [P2]

Patients expressed serious difficulty in social and work life, having suicidal thoughts, lack of awareness and less acceptance of mental illness in families and societies contributing to hesitancy in acknowledging depression:

Mostly it [depression] affected my relationship with people … because with this illness I feel like it’s very difficult to communicate… to be able to express my emotions … I feel like a burden and so it has mostly affected my relationship. [P1]

When I first thought of seeking help, I was hesitant because I thought it wasn’t that big a deal and I could take care of it on my own. [P1]

There was less awareness, what is it, suicidal thoughts used to come, it was all around negativity. [P2]

In society and in the family, people used to ask … what has happened to you? Is it a brain disease? There was not much awareness at that time … [P2]

According to therapists, patients’ attribution of depression is primarily interpersonal problem/conflict:

Some of these clients actually don’t come up with any explanation they just say I am not able to sleep properly, I am not feeling like working … I think we are able to infer based on our experience but I think sometimes with certain clients that kind of explanation and attribution doesn’t generally come up … interpersonal seems to be really the major reason for the depression here for them … some kind of problem with some kind of relationship or at workplace. [T8]

Sometimes they [clients] come with understanding of biological imbalance or having interpersonal problems which come up as stressors and they want a solution as to how it can be solved. [T3]

All therapists reported that there is lack of awareness about therapy and therapy process and there is an initial hesitation to undergo therapy. One therapist described it with an example:

I think they come in thinking that therapy is some sort of class … a lot of them call it ‘class’. So they kind of give the power to the therapist … by saying that you are the expert you have to guide me through this. So, therapist has to walk through actually so many different steps right from explaining … the cause effect relationship … the condition itself and then orienting them into the process of therapy. [T7]

Another therapist explained about importance of educating about therapy. It is also seen that sometimes family members are involved in decision making. So, psycho-education of family member is also important:

There may be resistance in comprehending this [therapy] kind of treatment. For example if patient(s) go to cardiologist, he/she will inform patient about any kind of procedure suited for him, will explain cost and effectiveness, risks involved and expectation, everything is given, but in psychotherapy we want them to come with some kind of understanding. [T3]

The therapists reported that patients use a number of religious practices like praying, spiritual meditation or visiting different temples, chanting, fasting, group religious practices, going for bible teaching, etc.:

They [patients] engage in more religious practices as a way of coping with their feelings of hopelessness that give them some hope that things will be fine. [T1]

Some of the practices are more of … reassurance seeking which can give them peace. [T2]

One therapist emphasised the influence of religion and explained that:

This concept of faith, concept of karma … these things have a lot of influence … I think the amount of learned helplessness that they develop even attribution go to the external factors that cannot change, I think that is an important cultural factor. [T5]

Some clients also see depression and suicidal ideas … almost like a punishment from God and that … they can’t actually perhaps get out of this or there might be something they have done for which they are guilty and they think that this depression, suicidal ideas might be because of something they have done or caused it. [T7]

The importance of allowing them to follow religious practices was emphasised:

If they are actually following something, then I just allow them to do if it helps them. I don’t prescribe anything in particular. [T2]

All therapists highlighted the importance of language compatibility between therapist and clients:

Guilt, I don’t know. Like in Maharashtrian background, I don’t know the Marathi word for ‘guilt’. Shame is there, okay. But, shame is not totally similar. For many emotions, in our local language, very limited words are there. And those limited words which are used to refer to the emotions are different. Like I said … Sadness and feeling bad are, these two are different experiences. Feeling low, sad and bad are different emotions. But in local languages, only one word is used to refer to all these different emotions. And because of that, it becomes very difficult for that person to share his emotions and distress to other people. [T1]

All therapists recommended using simplified terminology and avoiding using technical terms:

If they don’t understand the words ‘cognitions’ ‘distortions’ and ‘irrational thoughts’ you [therapist] should not be using these terms. So it is not necessary for them to understand what these terminologies mean. I just use simple words like unhelpful thoughts. The word ‘unhelpful’ is being used commonly, because everyone is able to connect with that. [T1]

Few therapists suggested the use of humour and proverb carefully and timely to put the meaning across:

I use proverbs. So you know sometime I know that the client is familiar because I come from the same state, some clients I know also from similar cultural and community backgrounds … some sayings and some proverbs that they may use and I use are very … on common ground. So I think more than cultural stories or fable, proverbs have a lot of meaning in them. [T2]

Assessment and engagement

Assessment has been categorised into two subthemes of preparation for therapy and presenting model (Table 4). Importance of developing rapport in the initial sessions was emphasised by therapists:

I spend a significant amount of time understanding the person and the problem, allow them to speak. I know some clients may need more time than others so I just let them speak. [T2]

After two sessions with the therapist and after developing good rapport, they are able to ventilate and express their distress … they find the therapy process helpful. [T1]

Table 4. Summary of themes, subthemes and codes under assessment and engagement

All therapists stressed giving corrective information about process of therapy and other treatment-related information at the outset of therapy:

They can be provided the details of treatment through various means like worksheet etc. can be encouraged to do their research bring up their doubts and uncertainty in the room. [T2]

Clients generally want to know the experience of [what] other clients with depression has been … you know when CBT has been used and typically how much time it takes and does it really work? And how does it work? So … educate them in that sense, they kind of get more certainty about how the process is going to be, because … when they are on medications, they know that after 2–3 weeks the symptoms will get better but certain times with therapy they may not be very sure about that. So I think just like a tentative timeline about how it will be and what techniques we will be focusing on initially and how then perhaps move on later, I think when we talk about these things they kind of get clarity… about what they can expect. [T7]

I usually use their own examples. I don’t formally write or show the model except to some clients with whom I feel it is very essential to draw that because lot of them won’t understand without it. Asking questions in [about] a more recent episode format, where I take the episode, sequentially look at what happened and how each component is integrated. I would use their own examples. I would say something like … okay today what happened and how did you solve it … when you got stuck trying to solve this problem, what really did you find. [T2]

With respect of therapy style (Table 4), all therapists emphasised moulding the style as per client’s need:

Collaborative definitely works… but I think our clients also come with some expectation of directive initially … I think they come with the directive thing so you have to balance it like client suitability to structured work … some of the clients prefer structured work and some do not. [T2]

I would say in the beginning of the therapy, directive … then, as understanding increases collaborative. And it depends on clinical judgement of the therapist with some client collaborative work from the beginning. With rural background, directive works most because if we use too much non directive then there is possibility that we lose them, client may drop out. [T3]

I think mostly directive works but there are also people who look for collaborative work. But you know how that thing goes like how that Guru chela kind of equation with therapist and the patient. Actually they place us in such an authoritative position that … we are supposed to help them out and help them get out of the illness. So mostly when they are coming in, they look for just advice like what I need to do to get out of it, so very directive sense of therapy … [T5]

Slowly after you do a couple of sessions they understand that … it’s not exactly directive in the sense and they know that there are certain things that they can also contribute. So, I think once we start off with that they are able to understand, that their role is also as important and it does not necessarily have to be what the therapist really has to say. So I think with sessions clients also tend to understand the process better and I think naturally kind of gets into this collaborative kind of work’ [T4]

Most of the therapists found once a week or bi-weekly session as standard protocol, but they stressed flexibility in scheduling sessions. Some of the professionals, however, pointed out that behavioural work may require more frequent sessions whereas in cognitive work, more spaced out sessions may work, although it may vary from client to client:

Once in a week session or biweekly would usually work. Clinical judgement is required to check how much can be given, but once a week is standard. Duration of session … 60 min is good enough. [T3]

Most of the therapists reported that brief therapy is usually encouraged by patients and longer therapy duration may not be feasible for many patients so they request a briefer format. However, they also emphasised the need for booster sessions:

Briefer therapy would be helpful and would be preferred by patients because if you tell them in the beginning that it’s going to take 16 or 20 sessions or something like that, they get more hassled with the duration. So I think briefer forms of therapy works well with a lot of patients. [T4]

If you give booster sessions then client knows that I am going to have another session after two weeks. Then after that I will be having one more session after a month. Otherwise client will likely to be anxious of becoming symptomatic, not being able to manage independently. Therefore, booster sessions become very important in our culture. [T1]

Another therapist explained flexibility in duration of session:

Some [patients] may need a longer time than someone else so you can keep a range 45 minutes to an hour and don’t be strict to someone with another 10–15 minutes. [T2]

If client does not have complex presentation and lot of axis II issues, 8 sessions are enough… more than enough – 6–8 sessions usually works for symptomatic relief. [T1]

Most of the professionals reported that 6–8 sessions is sufficient duration for symptomatic relief. However, a few recommended 10–12 sessions for duration of therapy. Therapists explained that for some clients, maintaining structure of sessions may be helpful and it is the therapist’s responsibility to maintain the structure.

The theme of engagement in therapy (Table 4) has been grouped into experience with homework compliance and experience of taking feedback by the therapists and patients on experience of therapy.

Therapists often experienced non-compliance of homework specifically involving paper pencil task:

I find more than paper pencil kind of homework where you asked them to write … doing experiment … if they are willing have more chances of completion. [T4]

Therapists reported that it is important to look for reason and identify barrier for not engaging in self-monitoring. They reported that a major reason for non-compliance is practical difficulties, which can be handled through problem solving. It was also recommended to identify activity that suits client interest or changing the style of homework as per clients’ interest:

I think they [clients] may not be able to write. Homework need not to be something in writing it can be an action or an activity and the writing need not to be in words but it can be probably small tally marks or can be recording of something and visit to a place or something like that, I think that would be more helpful. [T8]

All therapists pointed out that the word ‘homework’ is problematic and they avoid using the word with clients. One of the therapist suggested using experiential task instead of ‘homework’:

We have to keep in mind what the idea of homework is … if we call it homework nobody will to do it. It needs to be presented better, we have to be collaborative there I think these are therapist related barriers. [T3]

I think it really helps to give the rationale for feedback because sometimes they may be a little hesitant to share if there is a critical thing. [T6]

Generally if the rapport is good patients are quiet candid about what has worked for them. [T7]

Few therapists suggested that anonymous written feedback usually works for them. Clients can be given time to think about feedback by giving areas of feedback prior to the session instead of asking abruptly:

I think there should be some flexibility that the therapist has to have because some are very driven by a structure … they need a lot of structure, I don’t disturb that. I try to be very flexible because if I disturb that, they may distrust the process. So I go by what is comfortable … so the therapist flexibility … much more important than client flexibility. [T2]

The patients described their experience of being in therapy. They reported that their understanding about illness has improved. One patient explained that being in therapy helped him in learning difference between normal dip in mood and clinical depression; they can now notice the dysfunctionality in thinking. Both patients expressed that they have learned better ways of managing emotions:

I remember my therapist explaining me how my … not feeling okay or not being able to take care of myself, not wanting to get up, feeling like a burden, having no energy… to do anything, even you know, get out or eat was like a big … and I have lost a lot of weight as well … they were symptoms of depression. [P2]

I think for me, even though there was a specific time limit, there was that flexibility … if I needed to … there was that sense of comfort and flexibility … It would still be based on how my mental state was, if I was you know … okay for it to end. So there was flexibility – that is what helped while being in therapy. [P1]

Adjustments in therapy techniques

Therapists expressed that some clients have poor awareness and less vocabulary to express emotions. It is observed that anger and irritation mask the expression of sadness in some cases (see Table 5). One therapist explained:

I think gender-based difference in how they express emotion or even what kinds of emotion are accepted out of them. Females are much more accepting of emotions like sadness and anger is something that is very difficult for them to express. [T4]

In certain culture, emotional expression seems to be accepted a lot … anger is shown in extreme and when they are sad they tend to expressing it a lot. While in certain other states their expression is in middle range … [T5]

Table 5. Summary of themes, subthemes and codes under adjustments in therapy techniques

It is important to use techniques like reflection, scaling intensity of emotions, use of diagrams and use of stories, charts and pictorial representation of emotion. The emotion of guilt is commonly seen in patients with depressive disorder which may be related to not fulfilling roles in family or shame of letting family/community down. Most of the therapists reported that beliefs are usually same as reported in literature on depression. As religion plays an important role, the beliefs on horoscope/fate like ‘I am doomed to failure’ may be present in clients:

Horoscope is something that has a lot of influence on what people believe. So sometimes, core belief like I am doomed to … till 2030 I am going to have this so that prevails. [T6]

Therapists explained that clients usually use same description to explain thinking and feeling, therefore it is important to educate the difference between thinking and feeling.

One of them suggested that a cognitive error list can be used where clients can explore different kinds of errors and the set of cognitive errors that commonly occurs with them. In addition, stories from textbook/examples can also be used to explain distortions. In behaviour activation, the description and specific details of activity like time of day, how many days/how much time, etc. are important to collaboratively decide with clients in session. Most of them suggested that if the client is religious, then suggesting religious practice as a task can be helpful. Therapists suggested that using simplified hand-outs and worksheets helps in getting the meaning across. All professionals viewed self-disclosure as a technique which has to be used cautiously and precisely:

Behavioural activation is something that has worked best in my experience. So, starting with some behavioural [task], giving them some concrete activity, guiding them and some problem-solving sometime helps … before we move on to more cognitive techniques. [T5]

Techniques remain the same but the implementation of techniques like about cognitive restructuring … the use of cognitive restructuring have to be specific to your culture … stories, anecdotes, metaphor etc…. and in cognitive restructuring you have to give examples to restructure their perspective … these example should be … possibly are from the Indian setting … Indian folk tales or couplets or anecdotes …we should use them more often … [T3]

Techniques that patients found useful included different techniques ranging from behaviour activation to restructuring techniques. One patient explained that addressing cognitive distortion of emotional reasoning, physically listing out and evaluating thoughts was helpful. Another patient reported that including new activities as per interest in daily schedule and setting tiny goals helped him. He also reported that thought record helped him understand model and what worst/realistic/best can happen helped:

There’s this one thing … it’s sort of an exercise … if your friend feels like this, how would you … approach them and how would you explain and make them realize what they are doing is not okay. So, she told me … when your thoughts are like, you know, those multiple spam messages that you get … and messages and texts you get from your friends. So you reply to the ones that are important to you and you delete the ones that are not. So these spam messages are those negative or distorted thoughts that you have and those messages from your friends are going help you or … help you grow are the messages that you reply to. [P1]

The therapeutic relationship (Table 5) depends on therapist skill of adapting to the clients’ needs and sensitivity. It is also seen that rural/suburban clients are generally excessively respectful and obey therapist (guru-chela relationship). The therapist needs to model acceptance of differing views and respecting of clients beliefs:

Making clients feel understood is very important. Therapist flexibility and the adaptability is very important. Sensitivity to client needs, good theoretical knowledge … I mean you can always learn clinical skills some of them are flexible and adaptable and you are not in a hurry to get somewhere … If you are so much driven by task in therapy … you will get lost in the technique as much as the client does … so you are not allowing the client to be … being with client get better it would not last without the skill but at least the skill will come available so be aware what the client is … self reflection for the therapist like you said feedback … or understanding where they are not able to understand … to look at self as much as you look at the client … so then you can adapt … that this technique is not working … why is it not working … then you might want to change otherwise you go on with that … doing versus being mode for the therapist is important. [T2]

Rupture in therapeutic relationship may happen for several reasons which one therapist expresses as:

Some clients constantly challenge the therapist’s credibility or constantly ask for evidences for each psychological strategy. [T3]

Another therapist explained that:

Sometimes I find that there are some clients who are stuck because they are not doing the task discussed upon but they keep coming with problems. So, I use it as an opportunity to stop and ask I think we need to work on this… what is the reason this is not working …what are the things you want to improve upon … [T2]

One patient explained that:

The best thing about therapy is like the fact that there is no judgment and for me especially when I started off it was social anxiety. So the fact that I could actually go and let it all out and say anything. [P1]

Even though there was a specific time limit there was that flexibility of … like if I needed more. There was that sense of comfort and flexibility. So there was flexibility that is what helped me while being in therapy. [P1]

Discussion

This study adopted the evidence-based framework by Naeem et al. (Reference Naeem, Phiri, Nasar, Munshi, Ayub and Rathod2016) of cultural adaptation of CBT. The focus is on understanding the factors that help and hinder assessment, engagement, and the therapeutic process. The findings may be used to prepare guidelines for cultural adaptation of CBT for depression in the Indian context and guide clinical practice in providing culture-sensitive CBT for depression. It will further aid in adhering to culturally competent service delivery in clinical practice.

Awareness of relevant cultural issues and preparation for therapy

The present study emphasised the need to adapt therapy based on socio-cultural factors and the clients’ clinical presentation. The therapists stressed that it is the therapists’ responsibility to educate themselves about clients’ cultural background and practices/nuances, acknowledge these and be sensitive about them. These findings are in line with previous studies emphasising the need to adapt CBT and the importance of therapist awareness of culture (Li et al., Reference Li, Zhang, Luo, Liu, Liu, Lin, Liu, Xie, Hudson, Rathod, Kingdon, Husain, Liu, Ayub and Naeem2017; Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Phiri, Rathod and Ayub2019).

The perception of depression is in accordance with previous findings where depression initially presents with somatic complaints. However, emotional symptoms are acknowledged upon questioning (Lin and Cheung, Reference Lin and Cheung1999). Therapists interviewed in the present study observed that patients’ understanding, explanatory model of depression, and treatment knowledge varies according to their education level, socio-economic status, and rural/urban background. This finding of the influence of culture and ethnicity on depressive symptoms presentation has been found in a number of previous studies (Bobak et al., Reference Bobak, Pikhart, Pajak, Kubinova, Malyutina, Sebakova, Topor-Madry, Nikitin and Marmot2006; Bromberger et al., Reference Bromberger, Harlow, Avis, Kravitz and Cordal2004; Iwata and Buka, Reference Iwata and Buka2002; Kanazawa et al., Reference Kanazawa, White and Hampson2007).

The therapists noticed that the term ‘depression’ is loosely used for all kinds of mental illnesses. The understanding and expectation from therapy largely depend on information given at referral, as most patients are referred by the treating psychiatrists in the study setting. Cultural and social context has a bearing on the causation of depression as interpersonal conflicts, family stressors, past sins, or wrongdoing are the major attributions given by patients while explaining illness. The expectation from therapy aligns with the attribution of illness to external factors where patients expect mood-enhancing effects and instant cure. Rather than learning new adaptive ways of coping or tolerating distress, clients want to get rid of the problem (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015).

The patients in this study witnessed stigma and family pressure. They had difficulty in help-seeking and viewed symptoms of depression as personal characteristics before coming to treatment. Stigma is a widespread phenomenon seen both in Western (Bhugra, Reference Bhugra1989; Brockington et al., Reference Brockington, Hall, Levings and Murphy1993) and Asian cultures (Ng, Reference Ng1997). In response to societal stigma, people with mental problems internalise public perceptions and become so ashamed of their symptoms that they often conceal them, resulting in diminished self-esteem and delay in help-seeking (Corrigan and Penn, Reference Corrigan and Penn1998; Otto, Reference Otto1999; Sussman et al., Reference Sussman, Robins and Earls1987). Mental illness is stigmatised to such an extent in some Asian cultures that it is thought to reflect adversely on family lineage, lowering marriage and economic prospects for other family members (Ng, Reference Ng1997).

Religious coping and taking help from faith healers is common among patients, which is in accordance with findings from other Asian countries like China and Pakistan (Li et al., Reference Li, Zhang, Luo, Liu, Liu, Lin, Liu, Xie, Hudson, Rathod, Kingdon, Husain, Liu, Ayub and Naeem2017; Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Phiri, Rathod and Ayub2019). Therapists added that sometimes patients prefer taking spiritual and empirical treatment simultaneously. In the present study, therapists further highlighted that religious beliefs need not be discussed in the therapy room until religious beliefs do not interfere with therapy or cause distress. However, religious practices can be utilised if the patient is religious, as an activity in behavioral activation. It highlights the need for knowing rationale of discussing religion and utilising it as per the interest of patients.

The importance of language compatibility is highlighted by therapists and patients alike. In the present study, therapists encouraged the use of proverbs, anecdotes, metaphors, examples from Indian folk tales, or couplets/textbook stories. Ancient experienced healers from Asian cultural backgrounds use stories to convey their messages (Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Sarhandi, Gul, Khalid, Aslam, Anbrin, Saeed, Noor, Fatima, Minhas, Husain and Ayub2014). Therapists recommended avoiding technical terms in therapy and have expressed concern about not finding equivalent words for certain emotions in the local language, thereby difficulty identifying the intensity of emotion. They highlighted the need to use the chart, diagram, and graphical emotion chart to educate about emotion.

Assessment and engagement

Due to a lack of awareness about the therapy process, the therapists must provide corrective information clarifying doubts and misconceptions about therapy. The first two to three sessions are crucial for building clients’ trust in treatment. Therapists highlighted the importance of letting clients ventilate and conducting a culturally sensitive assessment. Similar recommendations were provided in the previous study based on qualitative interviews (Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Phiri, Rathod and Ayub2019). Therapists suggested that the CBT model should be explained in an easily understandable manner. The therapist needs to simplify the model for the client by giving examples – sequentially questioning and observing a recent event may help. Additionally, drawing diagrams has also proved to be helpful. The contribution of societal factors has to be kept in mind, like beliefs about normative roles in society during an assessment.

Regarding therapy style, all therapists agreed that collaborative model works, although clients come with expectation of directive style initially. Therapists may have to mould the therapy style as per the client’s needs. They added that therapy can start in a directive mode, which can be slowly converted into a collaborative mode as therapy progresses. Patients from Asian cultures often feel uncomfortable during questing or deciding for themselves. Therapists are supposed to offer guidance or answer to clients’ problems (Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Phiri, Rathod and Ayub2019; Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Latif, Mukhtar, Kim, Li, Butt, Kumar and Ng2021). Similarly, it was also mentioned that clients in Asian cultures expect the therapist to take on an authoritative role. Hence, a gradual development of collaborative stance may be helpful.

Regarding structural modifications, therapists stressed the importance of flexibility with regard to session duration, frequency and structure. They also recommended booster sessions based on clients’ reactions to termination and clinician judgement. However, they recommended a slow pace and more time at the start of treatment to ease the clients’ anxiety with setting and therapy process. This finding is in accordance with a previous study, which recommended the therapists be flexible about the length and frequency of sessions and explicitly empower clients to have input in making these decisions collaboratively (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015).

Clients’ engagement is a challenging factor in therapy. To enhance clients’ involvement in sessions and in-between sessions, therapists suggested involvement of family members. In some families, clients depend on family members for decision. Including family in psycho-education and giving information regarding therapy process can be helpful (Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Phiri, Rathod and Ayub2019). Homework assignment is an active ingredient in CBT (Kazantzis et al., Reference Kazantzis, Whittington and Dattilio2010). In the present study, therapists explained the problem they faced in engaging clients in therapy, like involving clients in self-monitoring tasks, lesser compliance to paper/pencil homework, hesitation in providing negative feedback regarding the therapy process and taking part actively in decision-making. They suggested creating experiential tasks as per clients’ interests and avoiding using technical terms and the word ‘homework’ in session. It is important to know clients’ perception of homework which may be as a punishment or chore. Similar suggestions have been provided in western literature too, as homework compliance appears to be a significant issue in CBT across cultures (Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Simons and Thase1999; Detweiler-Bedell and Whisman, Reference Detweiler-Bedell and Whisman2005; Ryum et al., Reference Ryum, Stiles, Svartberg and McCullough2010).

Adjustments in therapy techniques

Therapists have noticed that people with depression frequently express feelings such as guilt, anger and shame. Shame and guilt are inherent feelings in Asian cultures for some people (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015). Acceptability of emotional expression also differs by gender, according to therapists. For example, anger is more commonly manifested in males and can be due to a person’s inability to express other emotions. Another study found that men exhibit higher rates of anti-social behaviours and alcohol abuse than women (Nolen-Hoeksema and Hilt, Reference Nolen-Hoeksema and Hilt2006), which may involve anger expression (Chaplin and Cole, Reference Chaplin, Cole, Hankin and Abela.2005) and have been linked to lower level of expression and experience of anxiety and sadness (Chaplin et al., Reference Chaplin, Hong, Bergquist and Sinha2008). The present study confirms the presence of beliefs of punishment from God and belief in fate. A previous study pointed out that clients with depression often feel guilty because of real or imagined mistakes or shortcomings. Patients often report guilt due to the inability to perform one’s role. This may be linked to role expectations, family, and societal pressure (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015).

Therapists suggested using activity scheduling at the beginning of treatment. Activity scheduling can be very helpful cross-culturally, as it is simple to explain and has a clear rationale, and so can be used early in therapy (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015). It is pointed out that it is easy to engage patients with behavioural work initially and then proceed to cognitive work. However, a few therapists suggested that behavioural and cognitive work can be used simultaneously. In behavioural activation, it is crucial to be specific, descriptive and collaborative. The use of hand-outs, therapy notes and worksheets was encouraged by all therapists. Targeting and addressing core beliefs are rarely possible in brief therapy as highlighted by therapists. Patients from Asian cultures often find behavioural methods like behavioural activation, behavioural experiments and problem-solving particularly useful (Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Latif, Mukhtar, Kim, Li, Butt, Kumar and Ng2021). Interviews from patients in the present study highlighted that the techniques they found beneficial included behaviour activation, education about cognitive distortions, and restructuring techniques like perspective taking exercise, worst/best, and realistic scenario.

Several studies have pointed out that Asian clients see their therapists in a respectful position and view the relationship hierarchically, which also implies that the therapists cannot go wrong (Hwang et al., Reference Hwang, Wood, Lin and Cheung2006; Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Phiri, Rathod and Ayub2019; Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015). In the present study, therapists suggested that such an attitude is more prevalent in clients from less educated and rural backgrounds. However, therapists make efforts to respect and acknowledge differences, flexibility in stance, and giving importance to process rather than the content of therapy as essential to inculcate. A mutually respectful and egalitarian relationship should be the goal of therapy, although the pace with which the paternalistic stance changes to a collaborative one has to be flexible, as pointed out by a previous study (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015). The present study confirms the finding that the therapist should expect ruptures in therapeutic relationship due to a variety of reasons such as relapse of symptoms, family disapproval, change in social circumstances, questioning therapist credibility, and any opposing thoughts or emotions relating to the client or his culture (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015). They also highlighted the need for relapse prevention and educating clients about the course and duration of treatment.

The present study is the first study that places cultural adaptation work on an empirical framework in India by examining therapists’ and patients’ experience of CBT for depression using qualitative interviews and documenting their opinions on cultural adaptation of CBT. We also included patients who have had an experience of CBT for depression so that their experience and insight from therapy can be used for adapting intervention.

Implications for therapy and research

The current study was conducted to plan culturally sensitive CBT for depression as a part of a randomised controlled trial. The findings from this study can be used to inform culturally sensitive assessment and formulation of CBT. The suggested modifications based on experience may be applied in clinical practice to improve acceptability and outcomes. An understanding and incorporation of cultural factors will enhance patients’ engagement with therapy and inform clinical practice. This study will help trainees to acquire an understanding of culturally relevant factors in India. The study findings may be used for developing culturally adapted CBT suited to the Indian context. Future research may focus on testing the efficacy of adapted therapy and comparing the outcome with standard CBT. There may also be a need to adapt CBT for disorders other than depression and anxiety.

Limitations and future direction

India is a diverse country, with religious, ethnic and regional heterogeneity contributing to cultural differences. For example, there are widespread cultural differences between the north and south of India. Participants in the current study are from a tertiary care hospital and research institute, and patients were also from an urban background. This limits the generalisability of findings. Given the modest sample size of the current study, future studies of a similar kind from different parts of India can help prepare comprehensive guidelines for CBT adaptation in India.

Key practice points

-

(1) Be aware and informed about culturally derived behaviour and perception.

-

(2) Therapist curiosity in learning and understanding clients’ culture background is essential.

-

(3) Use cultural sensitivity in assessment and formulation of CBT for depressive disorders.

-

(4) Educate the patients about treatment and illness at the outset.

-

(5) Simplify the model as per clients’ needs.

-

(6) Give importance to process rather than the content of therapy.

-

(7) Clients may need time to adjust to a collaborative relationship.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, M.M. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Acknowledgements

We thank the therapists and the patients who participated in the study for their time and contribution.

Author contributions

Sayma Jameel: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Methodology (equal), Resources (equal), Writing – original draft (equal); Manjula M: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal), Supervision (equal), Validation (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Shyamsundar Arumugham: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal), Supervision (equal), Validation (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Thennarasu K: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal), Supervision (equal), Validation (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal).

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. This study was carried out as part of PhD thesis work of the first author, S.J.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

Authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. The ethical approval was obtained from National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India (Institute ethics committee reference number NIMH/DO/BEH. Sc. Div./2019-20).

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.