Introduction

Coronary heart disease is the second leading cause of death in the UK and the number one cause of death in males (Office for National Statistics, 2018). In the UK alone there are over 900,000 people living with heart failure specifically (British Heart Foundation, 2019). Heart failure is progressive and unpredictable, with the possibility of sudden death at any stage (Connolly et al., Reference Connolly, Beattie, Walker and Dancy2014). Physical ill health frequently has consequences for patients’ mental health. A meta-analysis of 38 studies of patients with heart failure found that around 30% had ‘probable clinically significant anxiety’ and over 55% had more symptoms of anxiety than expected for the general population (Easton et al., Reference Easton, Coventry, Lovell, Carter and Deaton2016).

Heart failure has also been linked to depression, with Rutledge and colleagues (Rutledge et al., Reference Rutledge, Reis, Linke, Greenberg and Mills2006) reporting that at least one in five people with heart failure meet criteria for major depression. Older patients with heart failure are more likely to experience depression than those who had a myocardial infarction or coronary artery bypass (or healthy older people) (Moser et al., Reference Moser, Dracup, Evangelista, Zambroski, Lennie, Chung and Heo2010). Significantly, Rutledge et al. (Reference Rutledge, Reis, Linke, Greenberg and Mills2006) also found a link between severity of depression and mortality, as well as an increased number of hospital admissions, even whilst controlling for disease severity. Mbakwem et al. (Reference Mbakwem, Aina and Amadi2016) also conclude that depression decreases quality of life and increases morbidity and mortality in those with heart failure.

The impact of anxiety and depression on those with heart failure can be substantial, affecting both their physical and mental health. This creates an additional burden on both the individual and the NHS. Alhurani et al. (Reference Alhurani, Dekker, Abed, Khalil, Zaghal, Lee and Moser2015) found that co-morbid anxiety and depression was a significant predictor of mortality in people with heart failure, although depression and anxiety alone were not. Sokoreli and colleagues’ meta-analysis (Sokoreli et al., Reference Sokoreli, Vries, Pauws and Steyerberg2016), of the effect of depression and anxiety on all-cause mortality in people with heart failure, found that depression was a significant, independent predictor. They recommended further research into depression in heart failure, including treatment.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has the benefit of incorporating physiological responses within its theory (MacHale, Reference MacHale2002), meaning it adapts well for use with clients experiencing physical symptoms caused by heart failure, by acknowledging their impact and the impact of depression/anxiety on them. In order for CBT to be effective in treating anxiety and depression in individuals with heart failure, this adaptation to the individual’s experience of heart failure is crucial.

Konstam et al. (Reference Konstam, Moser and Jong2005) stress that further research is needed into non-pharmacological treatments for the psychological effects of heart failure and the need for these to be individualised. A meta-review by Baumeister et al. (Reference Baumeister, Hutter and Bengel2011) demonstrated that psychological interventions have ‘a small yet clinically meaningful effect on depression outcomes’ in patients with coronary artery disease, but the evidence was sparse due to the low number of trials and heterogeneity of the populations and interventions. In relation to depression and self-care, Freedland and colleagues (Freedland et al., Reference Freedland, Carney, Rich, Steinmeyer and Rubin2015) found that a CBT intervention targeting both depression and heart failure self-care was effective for reducing depression, but not for improving self-care and physical functioning.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) provides clinical guidance on managing depression in adults with a chronic physical health problem. NICE recommends the use of individual CBT as one possible intervention for these clients; for example, when clients have not responded to low intensity intervention, such as guided self-help (NICE, 2020a). CBT is also recommended in the treatment of generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) (NICE, 2020b). However, there is no specific NICE guidance on treatment for co-morbid anxiety and depression in clients with chronic physical ill health. These clients may frequently be considered ‘complex’.

Tully et al. (Reference Tully, Selkow, Bengel and Rafanelli2015) found that co-morbid anxiety and depression in people with heart failure could be treated with GAD-focused CBT, within a collaborative care approach, leading to improvements in both depression and anxiety. They stressed the importance of patient preference in treatment modality and the benefits of graded exposure to exercise.

Celano et al. (Reference Celano, Villegas, Albanese, Gaggin and Huffman2018) also noted the prevalence of anxiety and depression in people with heart failure and the association between this and worse physical outcomes. They concluded that ‘further research to […] develop effective treatments for these disorders in heart failure patients is badly needed’. Overall, there is tentative evidence supporting the effectiveness of CBT for treating co-morbid anxiety and depression in people with heart failure, but there is currently insufficient research and evidence for this specific sub-group. In particular, there is a lack of detail on the specific nature of CBT used.

Cully et al. (Reference Cully, Stanley, Petersen, Hundt, Kauth, Naik and Kunik2017) looked at the effectiveness of brief CBT, focused on developing coping strategies for both the physical and emotional symptoms of heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, based on earlier work (Cully et al., Reference Cully, Paukert, Falco and Stanley2009) that combined modular based CBT with disease self-management. The studies of both Cully et al. and Tully et al. (Reference Tully, Selkow, Bengel and Rafanelli2015) reported that anxiety and depression were reduced and patients reported high levels of satisfaction with the treatment offered. Barrera et al. (Reference Barrera, Cummings, Armento, Cully, Amspoker, Wilson and Stanley2017) described the use of telephone-delivered CBT for housebound older people with multiple long-term conditions, including one with heart failure, offering seven to nine sessions. Elements included behavioural activation, diaphragmatic breathing, calming self-statements, and exposure and relapse prevention, with good outcomes in relation to three patients in terms of reduced anxiety and depression, suggesting that telephone-delivered therapy is an option for some patients. These papers suggest that incorporating a transdiagnostic framework may be helpful for patients presenting with heart failure and co-morbid anxiety and depression.

This case report follows on from Cully et al.’s (Reference Cully, Stanley, Petersen, Hundt, Kauth, Naik and Kunik2017) research and examines the use of short-course transdiagnostic CBT in treating co-morbid anxiety and depression in a client with heart failure, including the impact of service set-up and the individual’s experience of heart failure symptoms. It hopes to demonstrate the effectiveness of the individualised, formulation-based CBT approach, within a broader framework of transdiagnostic CBT and the benefit of multidisciplinary team (MDT) working.

Presenting problem

B was a 73-year-old male with heart failure and an ejection fraction of 21% (compared with a norm of 70–80%). He had experienced several failed operations to improve his heart functioning and was part of a cardiac resynchronisation therapy with defibrillator (CRT-D) trial. The implanted device made the left and right ventricles of his heart contract in time and acted as a defibrillator, as B was at risk of sudden death due to atrial fibrillation. However, the CRT-D was switched on and off through 6-monthly cycles, with B unaware whether it was being turned on or off.

B was experiencing mixed anxiety and depression due to his poor physical health and anxiety over the cycle of the trial, with a GAD assessment (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe2006) score of 15 (severe anxiety) and a Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001) score of 17 (moderately severe depression) at assessment. B had been taking Citalopram for around a year with some improvement in mood, but was still struggling with significant low mood and particularly with anxiety. Nursing staff within the MDT reported that he was often tearful and distressed and had become predominantly housebound.

B had previously been referred for guided self-help around 2 years prior to the intervention detailed within this paper, when he was newly diagnosed with heart failure. He had dropped out of therapy as he stated he did not find it beneficial.

Conceptualisation

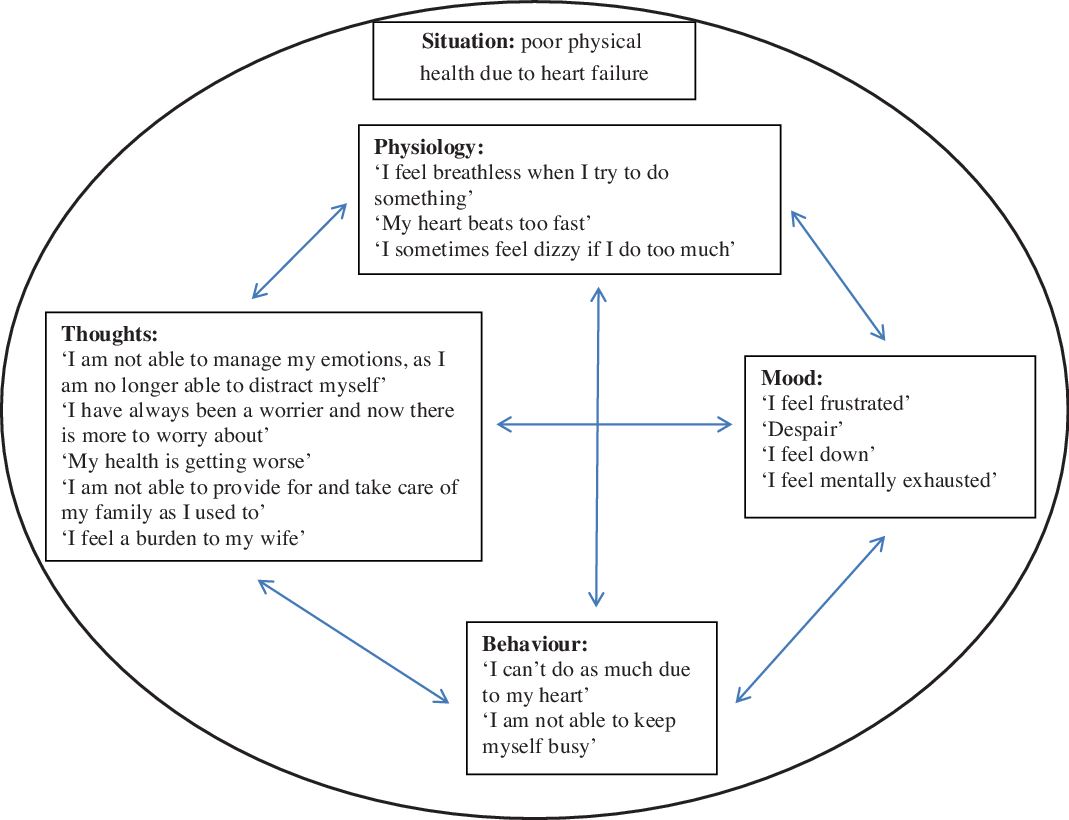

The formulation developed between B and the therapist (Fig. 1) used Padesky’s 5-aspects model of CBT, as described in Padesky and Mooney (Reference Padesky and Mooney1990). It suggested that his heart failure diagnosis, and particularly his recent unsuccessful surgeries, was the primary trigger for the current episode of anxiety and low mood. The impact of this was mediated by various factors, including B’s thoughts on the situation and his behaviour.

Figure 1. Cross-sectional formulation for client B.

The physical symptoms B experienced due to his heart failure impacted his behaviour. There was a thought–behaviour interaction, in that B believed his current behaviours had less value than his behaviours when he was well and this negative thinking style meant that B engaged in fewer activities. This interaction was directly connected with his mood, in that his mood both mediated his thoughts and behaviours as well as being mediated by them.

Figure 2 demonstrates a more comprehensive formulation developed by the therapist following the initial formulation with B, based on Laidlaw et al.’s (Reference Laidlaw, Thompson and Gallagher-Thompson2004) ‘Comprehensive Conceptualisation Framework’ CBT model for older adults. It shows how B’s background was one of valuing hard work and caring for others. His heart failure had impacted on these values and left him feeling worthless, a burden, low in mood and anxious about his role.

Figure 2. Age-augmented comprehensive conceptualisation framework CBT formulation for client B.

B had kept busy throughout life as a coping strategy for any difficult emotions, but was now unable to do so. This led to further anxiety that he was not coping, which was reinforced by his wife. She had voiced her concerns to B and was taking over roles that B would once have taken on, but now found more difficult due to his heart failure.

Discussion with the specialist nurses involved in B’s care provided some background in the progression of his illness and deterioration in his mood and anxiety symptoms over this time. They were also able to advise that moderately increasing B’s level of exercise would be beneficial, contrary to his belief.

B was considered to have low clinical risk. He denied suicidal ideation and thoughts of self-harm and denied any history of such. He scored 0 on the PHQ-9 question 9 (‘Thoughts that you would be better off dead, or of hurting yourself in some way?’). His family were a strong protective factor.

Course of therapy

The CBT sessions were delivered as part of the Psychological Interventions in Nursing and Community (PINC) service, within Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust (East). This service places psychology staff within physical health services to offer individual CBT to housebound patients. The one-hour sessions are delivered one-to-one in patient homes by an assistant psychologist trained to deliver transdiagnostic CBT, with supervision from a consultant clinical psychologist.

A psychologist sits with the Heart Function Team and discusses with the specialist nurses whether psychological input would be beneficial for their patients. B was referred to the PINC service by one of these nurses, who had picked up on his low mood and anxiety during their home visits to him.

B received six sessions of CBT, roughly weekly, including assessment. The time of the session was not the same each week, as the service accommodated other healthcare appointments. The service would have provided up to 12 weeks of CBT had this been required, but therapy is guided by the individual formulation and client progress.

Session 1: Assessment and preliminary discussion of goals

B stated he had ‘always been a worrier’ but previously kept busy to distract himself from these thoughts. Due to his heart failure, this was no longer an accessible coping strategy. B’s main sources of anxiety were his health and worry about his family. These were linked in that his poor health meant he could no longer support his family in the same way. He expressed feeling a burden, as well as frustration and despair. His main hobbies were watching stock car racing and representing the family business at shows, but this had recently become infrequent due to his health and he felt isolated.

B was going for a short walk most days (less than 200 metres), but always with someone with him. He occasionally went out alone, but always with the house in sight ‘in case something happens’. He reported significant anxiety around leaving the house, fearing becoming unwell or having a panic attack and being unable to call for help/an ambulance.

B’s initial goals were to be able to go out for walks alone and ideally to be able to get as far as the local shops and to gain better control of his worrying and feel less anxious. These aspirations were discussed within the MDT and considered realistic goals, given his level of ill health.

Session 2: Joint formulation, psychoeducation and introduction to behavioural activation

This session began by setting concrete goals for therapy:

To walk to the local shops alone

To walk around the block (about one mile)

To drive to the park

To better control worrying

B and the therapist put together a working (cross-sectional) formulation of his current situation and presenting difficulties, as outlined in the previous section. This was used to explain the concept of behavioural activation. Gardening was jointly selected as the best place to start, fulfilling both enjoyment and mastery goals.

The therapist also discussed and practised breathing regulation, including deep breathing exercises, with B. They discussed breathlessness in relation to exertion and heart failure, focusing on pacing. B became frustrated and consequently low in mood when he was unable to manage his breathlessness, as well as experiencing anxiety. It was hoped that a better understanding and management of his breathlessness would improve both his depression and anxiety symptoms.

B found it difficult to remember how he felt on different days, so it was agreed for him to keep a daily mood and anxiety rating along with his record of activities, so that links could be looked at.

Homework:

Cut small hedge using breathing techniques and pacing

Go for a drive

Mood and anxiety ratings

Session 3: Behavioural activation, thought challenging and mood ratings

This session followed two physical collapses B had during the week and a day spent in hospital. His mood was objectively lower than the week before and his anxiety increased. The therapist guided B to talk through the connection between this experience and his thoughts, mood and anxiety. The therapist challenged B’s automatic negative and anxious thoughts and encouraged him to think of possible alternative thoughts. B put forward the positives that he was checked over in hospital, the collapses had been explained, the risk mitigated and there were no concerns with his pacemaker. The inter-relationships between physical health, depression and anxiety were explored.

B’s mood ratings also evidenced his sense of achievement and improved mood when he had accomplished the homework goals. This demonstrated to B that he had some control over his emotions and, combined with his record of anxious thoughts/feelings, helped him understand changes in his mood.

However, B was frustrated that his wife did not want him going out alone or doing too much. The therapist and B discussed how he might have a conversation with his wife to come to a compromise. They also discussed alternative thoughts to thinking simply that his wife was restricting him, looking at what motivations she might have, e.g. concern for his safety because she cares about him.

Homework:

Behavioural activation

Mood/anxiety record and sense of achievement ratings

Practise recognising and addressing cognitive biases leading to anxiety and depression, using thought challenging and alternative thoughts

Session 4: Therapy reflection

B had achieved all of the homework activities and was objectively less anxious and low in mood than the week before. He was now walking significantly further when he went out with his wife and reported improved breathlessness management and pacing. Using knowledge gained in earlier sessions, B had adapted his behaviour and thoughts both during and after the walk and with other activities, to manage his physical symptoms. He recognised that his breathlessness could be caused just by being tense/anxious, so he worried less about becoming breathless and instead used breathing techniques to try and bring his breathing back under control.

B had been to watch stock car racing with some friends, which he had enjoyed and proved to himself that he could go out for the day. He explained that he had a conversation with his wife beforehand and reassured her that he would be careful. In addition, B had started driving his friend/lodger out when needed and described being able to talk about how he is feeling with this friend, which had increased his support network.

In addition to using distraction to manage B’s worry, the therapist and B discussed using the ‘Worry Tree’ and ‘Worry Time’. This included when to problem solve and act and when to just write down worries to come back to later if needed and then use distraction, knowing the worries can be visited later.

Homework:

Practise writing down worries and using ‘Worry Tree’ and ‘Worry Time’

Continue daily activities and mood/anxiety record

Session 5: Worry and technique recap

B had been having a good week and doing various activities, some independently and some with friends/his wife. He believed these activities had contributed to improved mood and decreased anxiety. He was committed to planning in activities from now on to maintain his mood.

The therapist and B discussed and explained his mood/anxiety ratings and worries from the week. B reflected that there had been a significant change in his thinking, in that he was increasingly able to not dwell on the negatives and worries, but instead focus on the positives. A positive coping statement/alternative thought B liked to use was: ‘If I can’t do it today, I will do it tomorrow’. This also signified a change in that he was now able to see that whatever his current situation, it wouldn’t be that way forever and he recognised that his mood, anxiety and health would fluctuate, so he needed to work with them.

The therapist and B recapped on the ‘Worry Tree’ and ‘Worry Time’, with B stating he had the Worry Tree stuck to his desk as a reminder.

The therapist discussed with B regarding his resilience to future bad news or poorer health, particularly as B’s mood and anxiety were significantly correlated with his health. B felt his heart failure was being well-managed and he had achieved what he wanted from therapy, but agreed to one more session on relapse prevention.

Session 6: Discharge planning and relapse prevention

B wished to talk through his mood/anxiety ratings and activity record, as this was something he had really connected with and benefited from. He found it helpful to reflect with notes from how he felt on the day, rather than just how he felt looking back, which he now acknowledged could be distorted. B’s week had been busy, which had given him a great sense of achievement, reduced anxiety and improved mood on most days, despite tiredness (which previously contributed to low mood). He had needed one day of rest in order to pace himself. He reported no worries, even when he had to rest and was feeling more confident in self-management.

The therapist spoke with B about what he might recognise as the first sign of his mood deteriorating. B thought this would be becoming agitated. He said he would continue to keep a daily mood rating and activity log to look over and help him identify any early warnings. If he felt himself becoming agitated, he decided he would go for a drive or do some light gardening. The therapist also discussed with B other activities he might be able to do on a difficult day, such as planning a craft show.

Three-month follow-up

B explained that he had been doing well since therapy had ended and he felt he had learnt techniques that had made him more resilient and better able to cope with the ups and downs in his life, particularly with regard to his health. He was continuing to use behavioural activation and was going for a walk every evening. He had also continued to keep a diary, which he found helpful to look back over and to put things into perspective.

Outcomes

A combination of measures was used; these were the GAD-7 to measure anxiety and PHQ-9 to measure depression, as previously stated, as well as the Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI) (Beecham and Knapp, Reference Beecham, Knapp, Thornicroft, Brewin and Wing1992) to measure B’s contact with health services before and after therapy. These measures were chosen due to the service’s links with IAPT and are the standard measures used nationally within IAPT and their long-term conditions service.

B demonstrated ‘reliable recovery’, through reductions in both his PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores, as defined by IAPT standards. Figure 3 shows that B scored 17 on the PHQ-9 at assessment, which falls within the moderately severe range. At the end of therapy, B scored 1, which is considered to be ‘healthy’. At 3-month follow-up this had increased slightly to 2, but still fell within the healthy range.

Figure 3. PHQ-9 scores at the end of each therapy session, including 3-month follow-up.

Figure 4 shows that B scored 15 on the GAD-7 at assessment, which is considered severe. His GAD-7 showed a decrease at session 2, before increasing again at session 3, after B had experienced two collapses and had been briefly admitted to hospital. After this there was a gradual decline in B’s GAD-7 score, with him scoring 2 (healthy) at the end of therapy. At 3-month follow-up this had decreased to 1.

Figure 4. GAD-7 scores at the end of each therapy session, including 3-month follow-up.

The CSRI data (Table 1) found a reduction in GP appointments, specialist nurse appointments, days spent in hospital and doctor appointments (other than a GP) in the 3 months post-therapy, compared with the 3 months prior. There was a reduction from 30 health care professional contacts in the 3 months before therapy, to just eight in the 3 months post-therapy.

Table 1. CSRI data for number of appointments before, during and after therapy

B also showed improved outcomes in terms of achieving his goals of attending the stock car races, being able to go to the local shops alone and going for regular walks. Feedback from the specialist nursing team, 3 months after therapy, also stated that B was no longer tearful during their visits and he had started attending a support group, which they had been trying to get him to attend for some time.

Discussion

This case report demonstrates the successful use of CBT for co-morbid anxiety and depression in a client with significant heart failure. It describes how using basic CBT principles can be effective, despite the ‘complex’ label that may be ascribed to these clients, as long as the interactions between their physical health, anxiety and depression are considered as a fundamental part of formulation and subsequent therapy.

The key themes of therapy used were psychoeducation, breathing techniques, behavioural activation, activity logging, pacing, mood/anxiety ratings, thought challenging, ‘Worry Tree’, alternative thoughts, positive coping statements and relapse prevention. This demonstrates that the use of these CBT techniques can be effective in the management of depression and anxiety in people with heart failure. Physical health conditions may put constraints on a client and on psychological therapy, but they do not have to prevent therapy from being effective, as long as reasonable adjustments are made for the client’s level of ill health.

The reduction in B’s contacts with healthcare professionals following therapy demonstrates his increased self-management and suggests that CBT plays a role not only in improving the mental health of people with heart failure, but also in improving their physical health management. Due to service restrictions, data were only collected over a limited period; longer follow-up would indicate if benefits were maintained both in terms of reduction in symptom severity and contact with other services. Further research investigating the impact of CBT interventions on health service use of patients with heart failure over an extended period would be beneficial.

In addition to the effectiveness of CBT as a treatment modality in anxious and depressed individuals with heart failure, it is important to consider the setting within which therapy takes place. This paper describes a client seen through a service embedded within nursing teams and without this link patients who may benefit from psychological therapy may not be picked up. Lefteriotis, a cardiology nurse, described (Lefteriotis, Reference Lefteriotis2013) the need for cardiac nurses to be involved in the early detection and treatment of depression in patients with heart failure due to their significant involvement with these patients.

The strong relationship and trust B had in the professionals involved in his care was a significant and recurring theme in assisting him to manage his anxiety around his heart failure diagnosis. The interdisciplinary link is also beneficial for patients, both in allowing psychology staff to assist nurses in detecting patients who are suitable for and may benefit from therapy, and also in enabling psychology staff to learn more about the physical health conditions their clients experience and gain a greater understanding of the impact on clients’ lives. This paper, therefore, suggests the availability of psychological therapy within cardiology teams as an example of effective service set-up.

The home-based nature of therapy provided to the client described was another crucial element in its effectiveness. B would not have attended a clinic to take part in CBT due to his ill health and, in particular, his anxiety around leaving the house. Another option, if it had been acceptable, would have been telephone-delivered CBT (Barrera et al., Reference Barrera, Cummings, Armento, Cully, Amspoker, Wilson and Stanley2017). Rutledge et al. (Reference Rutledge, Reis, Linke, Greenberg and Mills2006) describe how clinically significant depression is more prevalent in more advanced heart failure and this is when patients are more likely to be housebound. This highlights the need for psychological therapists to deliver CBT to people with heart failure in their own homes, to prevent a substantial proportion of perhaps the most unwell patients being unable to access psychological support.

The authors acknowledge the limitations of this research, particularly the single case study design, which limits the extent to which the findings can be generalised. However, this methodology was selected with the aim of detailing a successful CBT intervention with a client with heart failure, for whom guided self-help had not been acceptable. Further research may be beneficial into the CBT techniques that work best for clients with heart failure, using a large cohort, as well as investigations comparing the effectiveness of different service designs.

Summary

This case report demonstrates successful CBT for co-morbid anxiety and depression due to heart failure. It seeks to encourage psychologists and CBT therapists to feel confident in using CBT with this population of physically unwell patients, particularly by utilising support from multi-disciplinary teams. It further highlights how using a transdiagnostic approach can be beneficial for such clients, allowing the incorporation of different physical and mental health factors into therapy. This individualised and formulation-driven approach does not have to be complicated to be effective, but the flexibility of adapting CBT for the individual client is valuable. Considering the placement of such a service is also important and it is suggested that a strong relationship between physical and mental health services for people with heart failure is crucial.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Heart Function Team based in East Berkshire, particularly Lucy Girdler-Heald, for their advice and support. We would also like to acknowledge the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust for funding a trip to visit services in the USA, including Houston, Texas where Professor J. Cully kindly shared his papers and experience of working with heart failure cases.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

Charlotte Slaughter and Chris Allen have no conflicts of interest with respect to this publication.

Ethical statements

The therapy described ran as part of the Psychological Interventions in Nursing and Community (PINC) service within Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust (East). It met the standard ethical procedures for this service and abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the APA. Informed consent for publication was gained from the client at the end of therapy and identifiable details have been removed.

Key practice points

(1) Integrating psychology services within physical health teams can be helpful for patients requiring psychological support to be picked up, as well as supporting learning between physical and mental health staff, with a view to improving overall patient outcomes.

(2) A transdiagnostic approach can be effective when working with clients with major physical health problems that interact with their mental health, causing multi-morbid mental health difficulties.

(3) Providing a home-based psychological therapy service is crucial for meeting the needs of this population of physically unwell patients, who are not requiring prolonged hospital in-patient stays.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.