Introduction

Family in mental health problems

Families play a vital role in supporting those with mental health problems. Investigation of the impact of anxiety disorders in families forms a small yet expanding area of work (Lochner et al., Reference Lochner, Mogotsi, du Toit, Kaminer, Niehaus and Stein2003), with only modest quantitative and qualitative differences in ‘burden of care’ when compared with severe mental illness such as psychosis (e.g. Veltro et al., Reference Veltro, Magliano, Lobrace, Morosini and Maj1994). The impact of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) on family functioning has received the greatest research attention compared with other anxiety problems. A review of family burden in OCD found evidence of a high degree of family dysfunction, particularly relating to conflict, distress and marital discord (Steketee, Reference Steketee1997). Black et al. (Reference Black, Gaffney, Schlosser and Gabel1998) reported increased disruption to family, social and personal life, due to anger, conflict, fatigue and marital discord in the OCD group, whilst Derisley et al. (Reference Derisley, Libby, Clark and Reynolds2005) found parents with an OCD child had poorer mental health and used more avoidant coping strategies. Surveys report a common perception of negative impact on family life, where OCD is a feature, both by the individual with OCD (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Roberts, Hollander, Rowland and Serebro1996) and the wider family, including parents, partners, children and siblings (Cooper, Reference Cooper1996).

Family accommodation in OCD

Family members of OCD sufferers often feel obliged to collude with compulsive rituals – typically referred to as family accommodation. Calvocoressi et al. (Reference Calvocoressi, Lewis, Harris, Trufan, Goodman, McDougle and Price1995) reported some degree of family accommodation in 30 of 34 caregiving relatives, noting that threats of violence ensured ‘accommodation’ in some more extreme cases. The interpersonal impact has been demonstrated by a wealth of research showing that caring for someone with OCD is associated with significant caregiver burden, psychological distress and reduced quality of life (Abreu Ramos-Cerqueira et al., Reference Abreu Ramos-Cerqueira, Torres, Torresan, Negreiros and Vitorino2008; Cicek et al., Reference Cicek, Cicek, Kayhan, Uguz and Kaya2013; Grover and Dutt, Reference Grover and Dutt2011; Kalra et al., Reference Kalra, Nischal, Trivedi, Dalal and Sinha2009; Torres et al., Reference Torres, Hoff, Padovani and Ramos-Cerqueira2012; Vikas et al., Reference Vikas, Avasthi and Sharan2011).

Family accommodation involves participation in rituals, modification of personal and family routines, facilitating avoidance, and taking on the sufferer's responsibilities. Examples include engaging in excessive hand washing to help reduce contamination fears experienced by a loved one, listening to repeated confessions of a relative who feels the need to constantly confess, providing excessive reassurance and/or removing knives to reduce or alleviate the distress of a relative with aggressive or suicidal obsessions (Lebowitz et al., Reference Lebowitz, Panza and Bloch2016). In order to reduce anxiety (Halldorsson et al., Reference Halldorsson, Salkovkis, Kobori and Pagdin2016), these behaviours may also help the family or couple to get through daily routines more efficiently. However, accommodation is associated with parental distress in paediatric OCD (Storch et al., Reference Storch, Lehmkuhl, Pence, Geffken, Ricketts, Storch and Murphy2009) and with anxiety and depression in relatives of adults with OCD (Amir et al., Reference Amir, Freshman and Foa2000). Different methods have been employed to assess accommodating behaviours in relatives of OCD sufferers. For example, Shafran et al. (Reference Shafran, Ralph and Tallis1995) administered a self-administered questionnaire to 88 family members of individuals with obsessive-compulsive symptoms and revealed that 60% of the family members were involved to some extent in rituals with the affected family member (Shafran et al., Reference Shafran, Ralph and Tallis1995). Nearly all the family members reported at least some degree of interference in their lives. Information was also gathered about the type of rituals in which members were involved, how they responded to the demands of the affected relative to engage in the rituals, their beliefs and knowledge about compliance, and the degree to which the rituals interfered in their lives (Shafran et al., Reference Shafran, Ralph and Tallis1995).

Excessive accommodation of compulsions runs counter to exposure-based therapy instructions and may instead reinforce symptoms and also increase relatives’ distress (Steketee and Pruyn, Reference Steketee and Pruyn1998). Amir et al. (Reference Amir, Freshman and Foa2000) reported that OCD sufferers whose relatives modified their schedules or otherwise accommodated their symptoms had a worse response to behavioural therapy. Correspondingly, helping family members disengage from compulsions and resist accommodation during behavioural therapy appeared to improve OCD sufferers’ outcomes (Grunes et al., Reference Grunes, Neziroglu and McKay2001; Van Noppen and Steketee, Reference Van Noppen and Steketee2009).

Another group developed a clinician-administered instrument, the Family Accommodation Scale (FAS), which assesses the nature and frequency of accommodating behaviours of family members of people with OCD (Calvocoressi et al., Reference Calvocoressi, Lewis, Harris, Trufan, Goodman, McDougle and Price1995, Reference Calvocoressi, Mazure, Kasl, Skolnick, Fisk, Vegso, Van Noppen and Price1999). Calvocoressi et al. (Reference Calvocoressi, Mazure, Kasl, Skolnick, Fisk, Vegso, Van Noppen and Price1999) reported that family accommodation was present for 88% of spouses and parents and correlated significantly with sufferer symptom severity, family dysfunction, and relatives’ stress. Most relatives reported that they were actually trying to attenuate sufferer distress or anger and decrease compulsions/rituals (Calvocoressi et al., Reference Calvocoressi, Lewis, Harris, Trufan, Goodman, McDougle and Price1995). More recently, Boeding et al. (Reference Boeding, Paprocki, Baucom, Abramowitz, Wheaton, Fabricant and Fischer2013) examined accommodating behaviours in partners of adults with OCD. As part of a treatment study, 20 couples were assessed for accommodating behaviours, OCD symptoms, and relationship functioning before and after 16 sessions of cognitive behavioural treatment. Partner-reported accommodation was associated with the sufferer's OCD symptoms at pre-treatment, and negatively associated with the partners’, but not the sufferers’, self-reported relationship satisfaction. Post-treatment partner accommodation was also associated with poorer response to treatment (Boeding et al., Reference Boeding, Paprocki, Baucom, Abramowitz, Wheaton, Fabricant and Fischer2013).

Reassurance seeking and provision within the context of OCD

Reassurance seeking occurs across the full range of OCD presentations. For example, individuals with OCD may ask others whether something is clean, whether they have done something properly, whether they are truly religious/heterosexual and so on. Clinical descriptions of reassurance seeking in the OCD literature have generally equated this behaviour to other compulsive or ‘neutralizing’ acts. Rachman (Reference Rachman2002) proposes that excessive reassurance seeking, compulsive checking, and other forms of OCD-related neutralizing behaviour can all be construed as strategies intended both to reduce the likelihood of negative outcomes (i.e. reducing ‘threat’), and to reduce one's perceived responsibility for such outcomes.

Studies of family accommodation revealed that family members provide reassurance to sufferers. For example, Calvocoressi et al. (Reference Calvocoressi, Lewis, Harris, Trufan, Goodman, McDougle and Price1995) interviewed sufferers and their family members and found that one-third of the relatives often reassured the sufferers, participated in the compulsions and assumed responsibility for activities usually carried out by the sufferers. Few empirical studies have investigated the way sufferers seek reassurance and the way reassurance seeking and its provision cause interpersonal difficulties in particular. Recently, Kobori and Salkovskis (Reference Kobori and Salkovskis2013) developed the Reassurance Seeking Questionnaire (ReSQ) and conducted it with 153 individuals with OCD. They found that the more individuals with OCD trust the resource, the more repeatedly they seek reassurance from it. From the carer's point of view, this result suggests that they would feel not trusted, because no matter how many times they answer, they are repeatedly asked the same question. The specific ways of seeking reassurance could also cause interpersonal problems. Both quantitative (Kobori and Salkovskis, Reference Kobori and Salkovskis2013) and qualitative (Kobori et al., Reference Kobori, Salkovskis, Read, Lounes and Wong2012) studies suggest that individuals with OCD seek reassurance very carefully. They become very careful about composing the right question (sometimes tricking to obtain a convincing answer) and may also use discrete ways of seeking reassurance to mask their reassurance seeking. They also become very careful about receiving reassurance. For example, they listen very carefully to the answer, they scrutinize the other person's facial expression to gauge how confident they are with the answer, and they show frustration when the person offering reassurance gives an ambiguous response or does not seem to think seriously. However, little is known about how carers experience and perceive reassurance seeking and providing. One qualitative study (Halldorsson et al., Reference Halldorsson, Salkovkis, Kobori and Pagdin2016) interviewed carers of OCD patients, and findings revealed that excessive reassurance seeking commonly leads to relationship problems and feelings of frustration. However, whilst carers are fully aware of the counter-productive nature of giving reassurance for the maintenance of OCD, they feel unable to cope day-to-day without giving reassurance.

The purpose of the present study

The purpose of the present study was to examine carers’ experience of reassurance providing and its relationship to the psychopathology of the sufferers. We focused on the specific area of reassurance seeking rather than the more general area of family accommodation in order to examine in detail the relationship between reassurance seeking and provision. Specifically, we first examined the carer's general account of reassurance provision and its relationship to psychopathology of the sufferers. Secondly, we evaluated carers’ emotional reactions when they provide and do not provide reassurance. Finally, we examined the correspondence between the experience of OCD sufferers and their carers in terms of their response to providing reassurance (or not).

Method

Overview

This study is part of a larger project which aims to investigate the phenomenology, functions, and people's perceptions of reassurance seeking in anxiety disorders. This project has been reviewed by the Joint South London and Maudsley and the Institute of Psychiatry NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC reference: 07/Q0706/39). The questionnaires were either posted to the participants or taken away by the OCD suffers who took part in the experiment about reassurance seeking. Participants were recruited from an out-patient service at the Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London or the charity organizations for OCD (OCD-UK, OCD Action) and anxiety (Anxiety UK). They received two questionnaires: one for sufferers and the other for carers. The questionnaires were completed in their own time, and returned by Freepost. Each participant received a £5 gift voucher for their participation. For all scales, missing data were replaced by the individual mode for that scale, if no more than 50% of the items on the scale were missing. Otherwise, the scale value was considered as missing.

Participants

Forty-two individuals with OCD and their carers took part in this questionnaire study. Carer is defined as the person who the OCD sufferer mostly seeks reassurance from, or the person who is the closest to the sufferer (e.g. cohabitee) if they do not seek reassurance. The data of carers were matched with the data of their corresponding sufferers.

The mean age of carers was 44.49 years (SD = 13.09), of whom were 22 females and 20 were males. The relationship of carers to sufferers included girlfriend or boyfriend (n = 10), friend (n = 4), wife or husband (n = 16), mother or father (n = 8), child (n = 1), or others (n = 2). In terms of their occupational status, 29 of them were in education or employed, while 13 of them were unemployed.

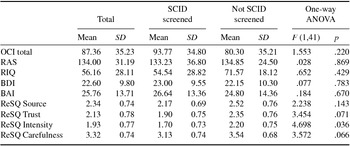

The mean age of corresponding sufferers was 37.40 years (SD = 12.00). Although 22 sufferers (who were recruited from an out-patient service at the Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London) were diagnosed with OCD using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; First et al., Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams1996) by trained psychologists prior to participating in this study, 20 of them were self-diagnosed or diagnosed locally (e.g. by a General Practitioner or Primary Care Trust). However, one-way ANOVA confirmed that individuals with OCD who were SCID screened and those who were not did not significantly differ in terms of the total score for Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory – distress scale (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Kozak, Salkovskis, Coles and Amir1998), Responsibility Attitude Scale (Salkovskis et al., Reference Salkovskis, Wroe, Gledhill, Morrison, Forrester, Richards, Reynolds and Thorpe2000), Responsibility Interpretations Questionnaire (Salkovskis et al., Reference Salkovskis, Wroe, Gledhill, Morrison, Forrester, Richards, Reynolds and Thorpe2000), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck and Steer, Reference Beck and Steer1987), Beck Anxiety Inventory (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Epstein, Brown and Steer1988), and all the Reassurance-Seeking Questionnaire (Kobori and Salkovskis, Reference Kobori and Salkovskis2013), except for the intensity scale (see Table 1).

Table 1. Sufferer's general psychopathology

OCI, Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory; RAS, Responsibility Attitude Scale; RIQ, Responsibility Interpretations Questionnaire; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; ReSQ, Reassurance Seeking Questionnaire.

Questionnaire for carers

Reassurance Seeking Questionnaire for Carers (ReSQ-C). This self-report scale was developed specifically for this study in order to look in detail at behaviours intended to provide reassurance when the OCD sufferers feel worried or anxious. ReSQ-C was first drafted by the first and second authors who have extensive experience in research and treatment of OCD, and then revised based on the comments and suggestions from two carers of the OCD sufferers. This questionnaire consists of three sections, and asks carers to report: (1) how they generally provide reassurance, (2) why they provide reassurance, and (3) how they think sufferers would feel when they provide or do not provide reassurance. Details of the scale are provided in the Results section.

Standardized measures for people with OCD

Reassurance-Seeking Questionnaire (ReSQ; Kobori and Salkovskis, Reference Kobori and Salkovskis2013). This questionnaire has four different scales and a separate section designed to assess emotional reactions:

-

(1) Source: this section enquires how frequently participants seek reassurance, consisting of 22 items.

-

(2) Trust: this section is about how much participants trust a range of sources of information, and consists of 16 items.

-

(3) Intensity: this section asks how many times participants seek the same reassurance until they stop, and consists of 16 items.

-

(4) Carefulness: this section measures how careful participants become when they are seeking reassurance, and consists of 11 items.

-

(5) Emotional changes: this section deals with how participants would feel when they receive or fail to receive reassurance. They rate different emotions in terms of how they would feel from ‘much less’ (–5) to ‘much more’ (+5) in three different situations: when the person they seek reassurance from does not answer, soon after they have received reassurance, and 20 minutes or more after they receive reassurance.

Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition, DSM-IV) (SCID; First et al., Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams1996)

This is a diagnostic instrument based on the DSM-IV criteria for psychiatric disorders. The SCID has been demonstrated to have acceptable reliability and validity (Segal et al., Reference Segal, Hersen and Van Hasselt1994).

Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory – distress scale (OCI-D; Foa et al., Reference Foa, Kozak, Salkovskis, Coles and Amir1998)

The OCI consists of 42 items composing seven subscales: washing, checking, doubting, ordering, obsessing (i.e. having obsessional thoughts), hoarding, and mental neutralizing. Each item is rated from 0 (has not troubled me at all) to 4 (troubled me extremely).

Responsibility Attitude Scale (RAS; Salkovskis et al., Reference Salkovskis, Wroe, Gledhill, Morrison, Forrester, Richards, Reynolds and Thorpe2000)

This 26-item self-report measure investigates general assumptions, attitudes and beliefs held about responsibility for harm to self and others. Every item consists of a statement about responsibility and asks individuals to rate how much they agree with it on a scale ranging from ‘totally agree’ to ‘totally disagree’. Scores are calculated by summing all of the assigned values that range from a score of 1 for ‘totally disagree’ to a score of 7 for ‘totally agree’. Salkovskis et al. (Reference Salkovskis, Wroe, Gledhill, Morrison, Forrester, Richards, Reynolds and Thorpe2000) reported that the RAS effectively discriminates between people with OCD and individuals with other anxiety disorders and non-clinical controls. The RAS has also been found to have high reliability and internal consistency (Salkovskis et al., Reference Salkovskis, Wroe, Gledhill, Morrison, Forrester, Richards, Reynolds and Thorpe2000).

Responsibility Interpretations Questionnaire (RIQ; Salkovskis et al., Reference Salkovskis, Wroe, Gledhill, Morrison, Forrester, Richards, Reynolds and Thorpe2000)

This self-report measure was created to investigate the frequency of and degree of belief in individuals’ interpretations (immediate appraisals) of specifically identified recent intrusions about harm coming to themselves or others. The RIQ has two subscales (belief and frequency), each with 22 responsibility appraisals. The items are the same on both subscales, but on the belief subscale the respondent is asked to rate how much they believe a responsibility appraisal on a scale of 0–100%, whereas on the frequency subscale the respondent is asked to rate how frequently the responsibility appraisal occurred during the past week on a scale of 0 for never to 4 for always. Test–retest reliability and internal consistency are reported as good for adult populations (Salkovskis et al., Reference Salkovskis, Wroe, Gledhill, Morrison, Forrester, Richards, Reynolds and Thorpe2000). In the current study, only the frequency part of the measure was used.

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck et al., Reference Beck, Epstein, Brown and Steer1988)

This 21-item self-report measure assesses an individual's level of anxiety. Each question has four possible answers ranging from 0 – ‘not at all’, to 1 – ‘mildly’, 2 – ‘moderately’ and 3 – ‘severely’, and individuals are asked to rate each symptom of anxiety listed using this scale. The BAI has been reported to have high internal consistency and good test–retest reliability (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Epstein, Brown and Steer1988).

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck and Steer, Reference Beck and Steer1987)

This 21-item self-report measure is a well-validated measure of depression severity in adults and adolescents, although it is not diagnostic. The inventory assesses cognitive, behavioural and somatic features of depression over the past week.

Results

General provision of reassurance

This section firstly asks carers how often they are asked for reassurance, and how often they provide reassurance to OCD sufferers using a scale ranging from never (0), sometimes (1), often (2), to all the time (3).

Next, carers were asked to rate how frequently they provide reassurance in more detail, using a scale ranging from once a month or less (0), once a week (1), two or three times a week (2), every day (3), every hour (4), to all the time (5). They were also asked to rate how many times they provide the same reassurance until the sufferer stops to seek, using a scale ranging from never (0), once (1), two or three times (2), four or five times (3), to six times or more (4). Finally, they were asked to rate how much strain giving reassurance puts on them, using a scale ranging from not at all (0), slightly (1), moderately (2), very much (3), to extremely (4).

The results are presented in Table 2. Results show that reassurance was commonly asked for and provided directly, and indirect reassurance seeking and providing was less common. The majority of carers had provided reassurance with a particular set of words, and half of them had been asked to take part in sufferers’ rituals. The majority of carers indicated that they provide reassurance every hour, they repeat the same reassurance two or three times, and giving reassurance moderately puts a strain on them.

Table 2. Frequency of carer's general behaviour of providing reassurance

The relationship between carer's provision of reassurance and sufferer's psychopathology

This section compares carer's ratings of their general behaviour of providing reassurance with sufferer's ratings of their OCD measures, depression, anxiety and reassurance seeking (see Table 3). Carer's rating of frequency of providing reassurance was correlated to sufferer's RIQ and BAI, and carer's rating of frequency of providing reassurance with a particular set of words was correlated to suffer's OCI total. However, ReSQ Source, ReSQ Trust and ReSQ Intensity were not correlated to any of carer's general behaviour of providing reassurance. Only sufferer's ReSQ carefulness, however, was correlated to carer's rating of being asked for reassurance, being indirectly asked for reassurance, indirect provision of reassurance, and provision of reassurance with a particular set of words.

Table 3. Correlation between the carer's ratings and the corresponding sufferer's ratings

OCI, Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory; RAS, Responsibility Attitude Scale; RIQ, Responsibility Interpretations Questionnaire; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; ReSQ, Reassurance Seeking Questionnaire. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Motivation to provide reassurance

Carers were asked to specify their understanding of the reasons they provide reassurance. They rated 12 items from totally disagree (0) to totally agree (6). The items were developed by OCD experts with the consultation of two carers of chronic sufferers of OCD. In the results in Table 4, items were sorted according to the mean score. This result suggests that carers do not generally believe that reassurance solves the problem or that bad things will happen without providing reassurance, but they cannot help providing it. They also feel that providing reassurance shows that they are supporting sufferers (see Table 4).

Table 4. Carer's rating of the motivations to provide reassurance

Items were rated from 0 (totally disagree) to 6 (totally agree).

Carers were asked to rate how reassured and anxious they think sufferers would feel in three different situations: when they do not provide reassurance (no reassurance), soon after they provide reassurance (short term), and 20 minutes or more after they provide reassurance (middle term). They rated how emotions would change from much less (–5) to much more (+5). These data were compared with the ratings of the sufferers. Thus sufferers were asked to rate how anxious and reassured they would feel in the three situations described above (see Table 5).

Table 5. Carer and sufferer's rating of feeling reassured and anxious across situations

A 3 × 4 mixed model ANOVA was conducted to compare the groups (carer and sufferer) in terms of the rating of feelings reassured across the situations (no reassurance, short term, and middle term). The ANOVA revealed no significant main effect of group: F (1,83) = 0.651, p = .422. However, there was a significant main effect of situation: F (2,82) = 200.455, p < .001; and there was a group × situation interaction: F (2,82) = 9.310, p < .001 (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Carer and sufferer's rating of feeling reassured across situations

Because the interaction was significant, post-hoc analyses of simple main effects using Bonferroni's method were conducted to compare each score within each group and within each situation. This analysis revealed that in the carer group, the score for feeling reassured when no reassurance was provided was smaller than at short term (p < .001) and middle term (p < .001), but the score at short term and middle term were not significantly different (p = .177). In the sufferer group, the score for feeling reassured at short term was greater than at middle term (p < .001), and the score at short term was greater than no reassurance (p < .001). Carer's rating for feeling reassured was greater than sufferer at no reassurance (p = .012), and smaller at short term (p < .001). There was no difference between carer and sufferer at middle term (p = .423).

A 3 × 4 mixed model ANOVA was conducted to compare the groups (carer and sufferer) in terms of the rating of feelings anxious across the situations (no reassurance, short term, and middle term). The ANOVA revealed no significant main effect of group: F (1,83) = 0.625, p = .432, and for interaction: F (2,82) = 1.288, p = .279 . However, there was a significant main effect for situation: F (2,82) = 119.160. Post-hoc multiple comparisons using Bonferroni's method revealed that the rating of feeling anxious was greater at no reassurance than middle term (p < .001), and greater at middle term than short term (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Carer and sufferer's rating of feeling anxious across situations

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to explore carers’ experience of reassurance provision and its relationship to the psychopathology of OCD sufferers. Specifically, we examined how caregivers and OCD sufferers feel when reassurance is provided versus not provided, as well as investigating caregiver's motivations for giving reassurance. In addition, this study examined how accurately carers perceive the effect of reassurance provision and not giving reassurance by comparing the data obtained from the sufferers of OCD.

Carer's perception of reassurance seeking and providing

From the carers’ viewpoint, reassurance is commonly sought and provided directly (e.g. verbally responding to the obvious request of reassurance), and they are less aware of subtle reassurance seeking. This result is consistent with our qualitative study (Kobori et al., Reference Kobori, Salkovskis, Read, Lounes and Wong2012), and suggests that individuals with OCD carefully compose questions so they can elicit a more convincing answer and/or seek reassurance in hidden (or subtle) ways and so that the other person does not notice that reassurance is being sought. This appears at least in part to occur because both the carer and the suffer know, through therapy and their own experiences that reassurance is ultimately counter-productive (Halldorsson et al., Reference Halldorsson, Salkovkis, Kobori and Pagdin2016; Kobori et al., Reference Kobori, Salkovskis, Read, Lounes and Wong2012). In addition to being asked for the same reassurance repeatedly, the majority of carers provide reassurance with a specific set of words and phrases, to perhaps maximize the calming effect of reassurance. Sufferers may become frustrated when the carer even slightly changes the words to reassure them, and they may ask for the reassurance again and again when it is not provided in the way they want. Regarding the motivation for carers to provide reassurance, the result suggests that carers do not generally believe that reassurance solves the problem or that objectively bad things will happen without providing reassurance, but they feel emotionally bound to provide it. They also feel that providing reassurance shows that they are supporting sufferers. Carers may feel helpless because they think that the only thing they can do to support the sufferer would be to offer reassurance, even though they know it does not solve the problem.

Correlations between the carers’ scores and the sufferers’ scores generally demonstrate that carer's behaviours in providing reassurance are associated with how carefully sufferers seek reassurance. Specifically, the more carefully sufferers seek reassurance, the more frequently carers report they are asked for reassurance. When sufferers become very careful, they make sure that the person giving feedback is seriously thinking about their answer, pay close attention to how the person answered, analyse whether the answer makes sense or whether there are any mistakes or inconsistencies in the answer, and they show frustration if the answer is not quite what they hoped for. This result is somewhat different to the findings of Boeding et al. (Reference Boeding, Paprocki, Baucom, Abramowitz, Wheaton, Fabricant and Fischer2013) that the partner's accommodation is associated with greater OCD symptom severity, but in line with our previous finding that the frequency and intensity (i.e. how many times they repeat the same reassurance seeking until they stop) of verbal reassurance seeking from other people is not significantly different between individuals with OCD, panic and healthy controls (Kobori and Salkovskis, Reference Kobori and Salkovskis2013). Sufferer's carefulness was also correlated with carer's perception of indirect reassurance seeking and indirect reassurance provision. This may support the view that sufferers become particularly careful when they indirectly seek and receive reassurance, such as such as composing a trick question so that other people do not notice reassurance seeking (Kobori et al., Reference Kobori, Salkovskis, Read, Lounes and Wong2012).

The results comparing how carers think sufferers would feel and how sufferers report that they would actually feel suggest that carer's perspectives on the impact of reassurance provision proved to be almost entirely accurate; both sufferers and carers perceive that reassurance works only temporarily, but even if the anxiety-relieving effect of reassurance decreases in the middle term, it is likely to be perceived as beneficial because they accurately perceived that sufferers would feel much worse if carers refuse to provide reassurance. The slight differences found in this study were that sufferers would feel even less reassured than carers imagine when they do not provide reassurance, and sufferers would feel even more reassured in the short term, suggesting that the need of sufferers is even stronger than carers believed.

The results support the notion that although it has been normally assumed that when people seek reassurance they obtain reassurance, reassurance seeking can be analysed into multiple components. These components may involve perceiving threat (and responsibility), urge to seek reassurance, composing the way to seek reassurance, (verbally) asking for reassurance, processing the response, examining the impact of the process and the response on the original threat and/or emotions, and processing the other person's response to the reassurance seeking. These components can be classified into two higher-level categories: (1) attempting to deal with threat and responsibility, and (2) processing feedback derived from the outcome of intended action. This distinction is relevant, given that individuals with OCD seek reassurance regardless of whether they obtain it or not; this is consistent with the clinical observation that individuals with OCD sometimes do not seem to care how clean they become, but they wash their hands anyway.

Clinical implications

The findings of the present study yield several clinical implications in relation to reassurance seeking and its provision. Firstly, clinicians need to be aware of the carefulness of reassurance seeking, which was related to carer's perception of being asked for reassurance. When clinicians manage reassurance seeking in therapy, they should pay attention not only to the frequency and duration of reassurance seeking, but also to how carefully it is sought. Reducing carefulness may reduce carers’ distress regarding reassurance providing, as well as challenge sufferers’ beliefs about threat and responsibility.

The present study demonstrated that sufferers feel reassured in the short term, and while the anxiety comes back in the mid-term, it is still (much) better than no reassurance. Moreover, carer's perception of this impact of reassurance was accurate. Before involving a family member or carer as a co-therapist, acknowledging carers’ struggles, and motivations to provide reassurance would help them feel understood by the therapist, thereby enhancing their collaboration in the therapy. Abramowitz et al. (Reference Abramowitz, Baucom, Wheaton, Boeding, Fabricant, Paprocki and Fischer2013) introduced the alternatives to the accommodation, such as teaching partners how to be supportive by providing esteem support and encourage the sufferer to ‘get through’ the anxiety until it habituates, rather than trying to avoid or neutralize it for the sufferer. This may also reduce criticism and hostility within the family, which are found to be associated with greater symptom severity and worse treatment outcome (Chambless and Steketee, Reference Chambless and Steketee1999; Renshaw et al., Reference Renshaw, Chambless and Steketee2003; Van Noppen and Steketee, Reference Van Noppen and Steketee2009). Furthermore, cognitive behavioural therapy that focuses on treating excessive reassurance seeking by helping OCD sufferers to shift from seeking reassurance to seeking support is a particularly promising development (Halldorsson et al., Reference Halldorsson, Salkovkis, Kobori and Pagdin2016). As an example, an OCD sufferer may tell a trusted person how bad he/she feels and how difficult he/she finds it not to give in to the compulsion to check and within that context asks for encouragement and support to overcome the urge to check, as opposed to asking for reassurance that the feared catastrophe is not going to happen.

Finally, direct or subtle reassurance seeking also tends to occur in the course of therapy, most commonly without the sufferer being aware that ‘just mentioning’ something they did as part of therapy to the therapist is problematic. In addition, therapist-directed exposure and behavioural experiments could, under some circumstances, act to provide inappropriate reassurance and hence unwittingly lead to failure of response prevention (Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis1999). Thus it is important to identify how clinicians judge whether the request from sufferers can be characterized as reassurance seeking, how they identify subtle and indirect reassurance seeking from sufferers, and how they respond when they are asked for reassurance.

Limitations and future directions

Because the sample size is relatively small in the present study, further validation studies with larger samples are required to ensure the generalizability of the findings. Another issue is that the clinical samples were limited to individuals with OCD. It remains unknown whether carers of other anxiety disorders (e.g. panic, health anxiety, social phobia, specific phobia, etc.) have similar or different experiences in providing reassurance. It should also be acknowledged that a subgroup of individuals with OCD had no verified diagnoses. Although individuals who were SCID screened and those who were not did not significantly differ in most of measures for psychopathology, this limits the generalizability of our findings. Additionally, this study did not exclude psychopathological disorders in the carers’ group.

Further, this study did not measure the frequency of the interaction between the carer and sufferer, and did not include the type of interaction. For example, a parent of the OCD sufferer would have different experiences compared with a friend of the OCD sufferer. There is also a possibility that the sufferer and the carer might have influenced each other when they filled in the questionnaires. For example, the suffer may want to check how the carer responds to the questions or they try to agree how often they seek and provide reassurance. Finally, the sample of the present study was limited to the English-speaking population. The questionnaire should be implemented with individuals who speak other languages and individuals with different cultural backgrounds. The present study suggests that carers do not generally believe that reassurance solves the problem or that bad things will happen without it. This result may be influenced by psycho-education, which was given when sufferers receive cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). Thus in other countries where interpersonal relationships are different from those in the UK or CBT is not widely available, carers may provide reassurance for other reasons, and may believe that reassurance solves the problem.

Main points

-

(1) 42 people with OCD and their carers were asked about reassurance seeking and providing.

-

(2) Frequency of reassurance provision is associated with how carefully sufferers seek.

-

(3) Both sufferers and carers know that reassurance works only temporarily.

-

(4) Carers perceive that sufferers would feel much worse if they do not provide reassurance.

-

(5) It would not be helpful to simply ask carers to stop providing reassurance.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

This work was supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship for Research Abroad from the Japan Society for Promotion of Science (Social Science 728).

Ethical statement

We have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the APA. This project has been reviewed by the Joint South London and Maudsley and the Institute of Psychiatry NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC reference: 07/Q0706/39).

Conflicts of interest

We have no conflicts of interest with respect to this publication

Learning objectives

-

(1) To develop an awareness of how carers of OCD sufferers struggle with reassurance providing.

-

(2) To gain an increased understanding of why it is difficult for OCD sufferers to stop seeking reassurance.

-

(3) To gain an increased understanding of why carers of OCD sufferers are unable to refuse to provide reassurance.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.