Introduction

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a common mental health condition in which individuals experience obsessional thoughts, impulses, images, urges, and/or doubts which cause distress, resulting in the emergence and maintenance of recurrent behaviours aimed at preventing or reducing this distress (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2005). Adults experiencing OCD often report co-morbid symptoms of depression (Overbeek et al., Reference Overbeek, Schruers, Vermetten and Griez2002) and suicidal ideation (Brakoulias et al., Reference Brakoulias, Starcevic, Belloch, Brown, Ferrao, Fontenelle, Lochner, Marazziti, Matsunagai, Miguel, Reddy, do Rossario, Shavitti, Shyam-Sundar, Stein, Torres and Viswasam2017), with associations between OCD and bipolar disorders also being prominent in literature (Ferentinos et al., Reference Ferentinos, Preti, Veroniki, Pitsalidis, Theofilidis, Antoniou and Fountoulakis2020). Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the lifetime prevalence of OCD in the UK was between 1 and 2% (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2005; Veale and Roberts, Reference Veale and Roberts2014). However, there is an already large and growing body of evidence highlighting the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the prevalence and severity of OCD in adults (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Drummond, Nicholson, Fagan, Baldwin, Fineberg and Chamberlain2022; Guzick et al., Reference Guzick, Candelari, Wiese, Schneider, Goodman and Storch2021; Jassi et al., Reference Jassi, Shahrivarmolki, Taylor, Peile, Challacombe, Clark and Veale2020; Wheaton et al., Reference Wheaton, Ward, Silber, McIngvale and Bjorgvinsson2021). Wheaton et al. (Reference Wheaton, Ward, Silber, McIngvale and Bjorgvinsson2021) reported that 76.2% of a cross-sectional sample of 252 individuals with OCD shared their OCD symptoms had worsened since the outbreak of the pandemic. Grant et al. (Reference Grant, Drummond, Nicholson, Fagan, Baldwin, Fineberg and Chamberlain2022) conducted a scoping review of 32 studies reporting that sizable proportions of individuals with OCD reported symptom worsening during the pandemic with those experiencing difficulty with contamination and washing symptoms being particularly susceptible. Guzick et al. (Reference Guzick, Candelari, Wiese, Schneider, Goodman and Storch2021) corroborated these findings within a systematic review reporting that the COVID-19 pandemic has been a huge stressor for individuals with OCD. Positively however, Guzick et al. (Reference Guzick, Candelari, Wiese, Schneider, Goodman and Storch2021) also reported that preliminary evidence suggests gold standard treatment approaches for OCD maintain strong efficacy. The gold standard treatment approaches include the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2005) guidelines for OCD which recommends the use of up to 10 hours of individual cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) including exposure with response prevention (ERP).

ERP and CBT for OCD

ERP is a behavioural ‘first-wave’ therapy which developed on principles of conditioning (Pavlov, Reference Pavlov and Anrep1927) and systematic desensitisation (Wolpe, Reference Wolpe1961). These concepts remain core components today (Abramowitz et al., Reference Abramowitz, Deacon and Whiteside2013; Challacombe et al., Reference Challacombe, Oldfield and Salkovskis2011). However, practical guidelines have since developed to include five conditions which state that ERP must be graded, prolonged, repeated, completed without distraction, and completed without compulsion.

Recent movements in literature examining OCD treatment have integrated CBT elements alongside ERP (Challacombe et al., Reference Challacombe, Oldfield and Salkovskis2011; Salkovskis and Kirk, Reference Salkovskis, Kirk, Clark and Fairburn1997; Veale and Roberts, Reference Veale and Roberts2014). CBT for OCD includes a focus on concepts such as normalising intrusive thoughts, responsibility, fusion with thoughts, safety behaviours, beliefs about compulsions, the intolerance of uncertainty, and distancing from thoughts (Challacombe et al., Reference Challacombe, Oldfield and Salkovskis2011; Veale, Reference Veale2007). Prominent research supports the efficacy of CBT for OCD on both a short-term (McKay et al., Reference McKay, Sookman, Neziroglu, Wilhelm, Stein, Kyrios, Matthews and Veale2015) and long-term basis (Kulz et al., Reference Kulz, Landmann, Schmidt-Ott, Zurowski, Wahl-Kordon and Vorderholzer2020).

Digital therapy

A unique feature of this case study is that it took place via a secure video communication platform during the novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2005) asserts that CBT for OCD can be delivered via telephone and therefore physical presence is not a pre-requisite for successful therapy. This has been supported in literature examining remotely delivered psychotherapy (Lamb et al., Reference Lamb, Pachana and Dissanavaka2019). However, there remains a relative absence of research examining the efficacy of videoconference-delivered CBT for OCD during and/or following the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly single-case evaluations of this approach.

Clinicians are presented with several uncertainties when seeking to deliver CBT for OCD over digital platforms. These uncertainties include having to respond to and contain the patient without access to the full range of non-verbal cues, having to creatively design exposures which can be completed alongside patients in sessions, and facing barriers to sharing formulations, exposure charts and resources. These additional challenges may interact with known barriers to delivering therapy remotely such as low clinician self-efficacy, high clinician belief of negative outcomes, and challenges within environmental contexts (Faija et al., Reference Faija, Connell, Welsh, Ardern, Hopkin, Gellatly, Rushton, Irvine, Armitage, Wilson, Bower, Lovell and Bee2020). However, these extrapolations remain speculative due to an absence of research within this area.

Literature examining digital CBT for OCD is growing. Prior to the pandemic, several studies evaluated the utility of remote and internet-based therapeutic interventions for OCD, with each of these demonstrating promising results (see Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Enander, Andren and Hed2012; Herbst et al., Reference Herbst, Voderholzer, Thiel, Schaub, Kaevelsrud, Stracke, Hertenstein, Nissen and Kulz2014; Kyrios et al., Reference Kyrios, Ahern, Fassnacht, Nedeljkovic, Moudling and Meyer2018; Patel et al., Reference Patel, Wheaton, Andersson, Ruck, Schmidt, La Lima, Galfavy, Pascucci, Myers, Dixon and Blair-Simpson2018; Wootton, Reference Wootton2016). Vogel et al. (Reference Vogel, Launes, Moen, Solem, Hansen, Haaland and Himle2012, Reference Vogel, Solem, Hagen, Moen, Launes, Haland, Hansen and Himle2014) examined the use of videoconference assisted therapy for OCD alongside the use of telephone calls and found comparable effects to face-to-face therapy. Matsumoto et al. (Reference Matsumoto, Sutoh, Asano, Seki, Urao, Yokoo, Takanashi, Yoshida, Tanaka, Noguchi, Nagata, Oshiro, Numata, Hirose, Yoshimura, Nagai, Sato, Kishimoto, Nakagawa and Shimizu2018) supports these findings, reporting that 16 sessions of individualised videoconference-mediated CBT can significantly reduce OCD symptoms. Separately, Aspvall et al. (Reference Aspvall, Andersson, Melin, Norlin, Eriksson, Vigerland, Jolstedt, Silverberg-Morse, Wallin, Sampaio, Feldman, Bottai, Lenhard, Mataix-Cols and Serlachius2021) examined the use of a 16-week computerised CBT programme for adolescents with OCD, with face-to-face follow-up if needed, and reported non-inferior differences in symptoms compared with 16 weeks of in-person CBT. More recently, Li et al. (Reference Li, Millard, Haskelberg, Hobbs, Luu and Mahoney2022) reported that the COVID-19 pandemic saw a 522% increase in online CBT for OCD programmes compared with the previous year. Li et al. (Reference Li, Millard, Haskelberg, Hobbs, Luu and Mahoney2022) also reported that both pre- and during-COVID the online CBT for OCD course which was examined was associated with medium effect size reductions in OCD, depression symptoms and psychological distress, indicating that digitally delivered CBT for OCD remains efficacious. Digital CBT for OCD is therefore indicative of positive outcomes. Although the current evidence base demonstrates breadth of efficacy and provides scope, there is an absence of studies providing a depth of knowledge by exploring the precise mechanisms involved. It would therefore add value to detail a videoconference-delivered CBT intervention for OCD, exploring the strengths and weaknesses of the digital delivery.

Aims

Therefore, this structured case report aimed to employ a quasi-experimental interrupted time series design to examine the effectiveness of a videoconference-delivered CBT intervention on the experiences and symptoms of blood contamination-based OCD in a working aged adult named Simon (pseudonym). The study utilises daily idiographic measures alongside session-by-session and pre-baseline, post-baseline, and post-intervention nomothetic measures to evaluate intervention effectiveness. Analytic principles from single case experimental design research were utilised as the intervention can be evaluated for its efficacy due to the ‘AB’ design (McMillan and Morley, Reference McMillan, Morley, Barkham, Hardy and Mellor-Clark2010; Smith, Reference Smith2012). The baseline phase becomes a natural control measure which increases the transparency of the intervention’s impact as pre–post comparisons can be made (McMillan and Morley, Reference McMillan, Morley, Barkham, Hardy and Mellor-Clark2010; Smith, Reference Smith2012). Moreover, the daily assessment of therapeutic outcome can highlight specific incidents of progression and/or deterioration. Therefore, greater consideration can be given to the therapeutic processes which have facilitated change.

Additional aims are to reflect on the strengths and weaknesses of delivering CBT for OCD on a digital platform and to explore whether the intervention can be delivered flexibly and creatively in this format whilst incorporating core aspects such as ERP, the intolerance of uncertainty, and the role of responsibility (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2005; Veale, Reference Veale2007). Finally, this case study aims to contribute to the current discussions around how to best optimise digital platforms in therapeutic work.

Method

Presenting problem

Simon was a 45-year-old male referred for psychological therapy in January 2020 by his GP. Simon engaged in an initial assessment with an Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) service in the North of England and was stepped-up for high-intensity CBT. During this assessment Simon reported fears around catching a potentially terminal blood-borne virus and then unknowingly infecting others and causing their death. Simon reported that the impact of these fears manifest in him isolating himself from social activities, repeatedly spotting potential contaminants, repeated washing, and losing faith in judgements of proximity and cleanliness.

Client’s background

In childhood Simon spent lots of time with his grandmother, who he described as having OCD with an obsession surrounding dog dirt. Simon shared he became ‘cautious’ around 8 years of age and for a year checked ‘everything like grandma did’, including doors, appliances, and for dog dirt. Simon managed to stop this, and until his late teenage years lived a relatively OCD-free life. In the early 1990s Simon discussed the British media ‘hammering home’ the HIV/AIDS message and suggested his OCD tendencies began increasing again.

In his 20s Simon married his partner, they raised a child together, and his OCD was manageable. Simon described ‘the catalyst’ for his OCD was in 2005 when he found lots of sick next to his car in a public car park. Simon ‘excessively’ cleaned his car inside and outside and experienced relief. Later in our sessions, Simon shared his wife died from a blood disease around this time but chose not to discuss this in further detail when given the opportunity.

Simon accessed psychological therapy for his OCD between 2006–2008, 2013–2014 and 2015–2016. He shared that he had previously completed packages of exposure therapy and that ERP and working up hierarchies had been useful. We discussed the quality of Simon’s previous therapy and Simon shared he was not familiar with the five conditions of ERP and had not integrated cognitive elements into therapy. We also discussed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on his current experiences. Simon shared that as his OCD is particularly centred on blood contamination, the COVID-19 pandemic had not influenced the severity of his symptoms, although he was pleased to be able to access therapy from home.

Goals for treatment

Simon’s goals included: (1) to learn new ways to manage situations and potential relapses, (2) to feel that his OCD is on a downward trend, and (3) to spend less time cleaning.

Idiographic measures

Three idiographic assessment measures were collaboratively constructed. Simon chose to assess these measures on scales of 0 to 10, with 0 representing the worst score and 10 representing the best score.

-

(1) Getting Back on Top: On a scale from 0 (low) to 10 (high), to what extent do you feel motivated to overcome your OCD today?

-

(2) Thinking More Simon: On a scale from 0 (low) to 10 (high), to what extent do you feel you have experienced the world today in a manner which is free from OCD-related obsessive thoughts?

-

(3) Being More Simon: On a scale from 0 (low) to 10 (high), to what extent do you feel you have lived your life today in a manner which is free from OCD-related compulsive behaviours?

‘Getting Back on Top’, ‘Thinking More Simon’ and ‘Being More Simon’ were Simon’s words to encapsulate what he wanted to measure and move towards during the therapeutic process. These idiographic measures will be referred to as (1) ‘Motivation’, (2) ‘Thoughts’ and (3) ‘Behaviours’ from this point.

Nomothetic measures

Simon completed two nomothetic measures pre- and post-baseline and post-intervention: the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory (OCI; Foa et al., Reference Foa, Kozak, Salkovskis, Coles and Amir1998) and Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation – Outcome Measure (CORE-OM; Evans et al., Reference Evans, Connell, Barkham, Margison, McGrath, Mellor-Clark and Audin2002), and two nomothetic measures each session: the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Arroll et al., Reference Arroll, Goodyear-Smith, Crengle, Gunn, Kerse, Fishman, Falloon and Hatcher2010) and the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe2006). These assessment measures were chosen as they were routinely used by the service.

The OCI (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Kozak, Salkovskis, Coles and Amir1998) is a 42-item self-report questionnaire which assesses seven aspects of OCD on a 5-point Likert scale, with greater scores indicating greater difficulties. The OCI reports good discriminate validity for individuals with OCD diagnoses compared with general social problems and post-traumatic stress disorders. Satisfactory convergent validity with the Maudsley Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory (Hodgson and Rachman, Reference Hodgson and Rachman1977) and the Compulsive Activity Checklist (Marks et al., Reference Marks, Hallam, Connolly and Philpott1977) is also reported, alongside good test–retest reliability for overall distress and symptom frequency (correlations >.80; Foa et al., Reference Foa, Kozak, Salkovskis, Coles and Amir1998). A mean item subscale score of ≥2.5 and a total score of ≥42 indicates the presence of OCD; however, scores are not diagnostic (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Kozak, Salkovskis, Coles and Amir1998). Finally, a deviation in total score of >32 indicates reliable change (NHS England, 2019).

The CORE-OM (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Mellor-Clark, Margison, Barkham, Audin, Connell and McGrath2000; Evans et al., Reference Evans, Connell, Barkham, Margison, McGrath, Mellor-Clark and Audin2002) is a 34-item self-report measure assessing subjective wellbeing (4 items), problems/symptoms (12 problems), life functioning (12 items) and risk (6 items), with greater scores indicating greater difficulties. The CORE-OM reports internal consistency of α between >.75 and <.95 and excellent test–retest stability (correlations .87–.91) for all domains excluding risk (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Connell, Barkham, Margison, McGrath, Mellor-Clark and Audin2002). The CORE-OM also reports high convergent validity with the Beck Depression Inventory versions 1 (.85) and 2 (.81; Beck, Reference Beck1961; Beck et al., Reference Beck, Brown and Steer1996), the Brief Symptom Inventory (.81; Derogatis and Melisaratos, Reference Derogatis and Melisaratos1983), the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (.88; Derogatis, Reference Derogatis1983), and the General Health Questionnaire (.75; Goldberg and Hillier, Reference Goldberg and Hillier1979). Results are reported as mean item scores with reliable change being a mean score change of ≥.5 and the clinical cut-off point is 1 (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Mellor-Clark, Margison, Barkham, Audin, Connell and McGrath2000).

The PHQ-9 is a 9-item self-report questionnaire assessing experiences of depression (Arroll et al., Reference Arroll, Goodyear-Smith, Crengle, Gunn, Kerse, Fishman, Falloon and Hatcher2010). Kroenke et al. (Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001) report the PHQ-9 to have good test–retest reliability (correlation .84) and construct validity, and excellent internal reliability (α = .89). The PHQ-9 has four cut-off points ranging from mild to severe depression, which enhances its specificity. Reliable change is indicated by a change ≥6 and the clinical cut-off score is 10 (NHS England, 2019). The GAD-7 is a 7-item self-report measure which assesses generalised anxiety disorder (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe2006). The questionnaire reports good construct validity and test-retest reliability (correlations .83; Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe2006). Reliable change is indicated by a change of ≥4 and the clinical cut-off score is 10 (NHS England, 2019). Greater scores on both the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 indicate greater difficulties.

Approach to analysis

A quasi-experimental interrupted time series design was utilised to assess the impact of the remote intervention (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Cook and Shadish2001). An interrupted time series analysis was utilised as the data consisted of a long sequence of n = ≥15 observations which had been interrupted by the introduction of the intervention phase (McDowall et al., Reference McDowall, McCleary and Bartos2019). Analytic principles from single case experimental design (SCED) research were utilised with an emphasis on descriptive analysis and visualised linear trends. This analytic approach provides a transparent method of exploring the impact of the remote intervention as visual comparisons can be made across the two phases (McDowall et al., Reference McDowall, McCleary and Bartos2019), with the two assessment and formulation sessions denoting the baseline phase and the nine intervention sessions denoting the intervention phase. To supplement the descriptive and visual analysis a Kendall’s tau-b (τ b; Kendall, Reference Kendall1938), tau calculations (Tarlow, Reference Tarlow2016), autocorrelations (Ljung and Box, Reference Ljung and Box1978), and Mann–Whitney U-tests were also performed, in line with SCED analysis.

Formulation

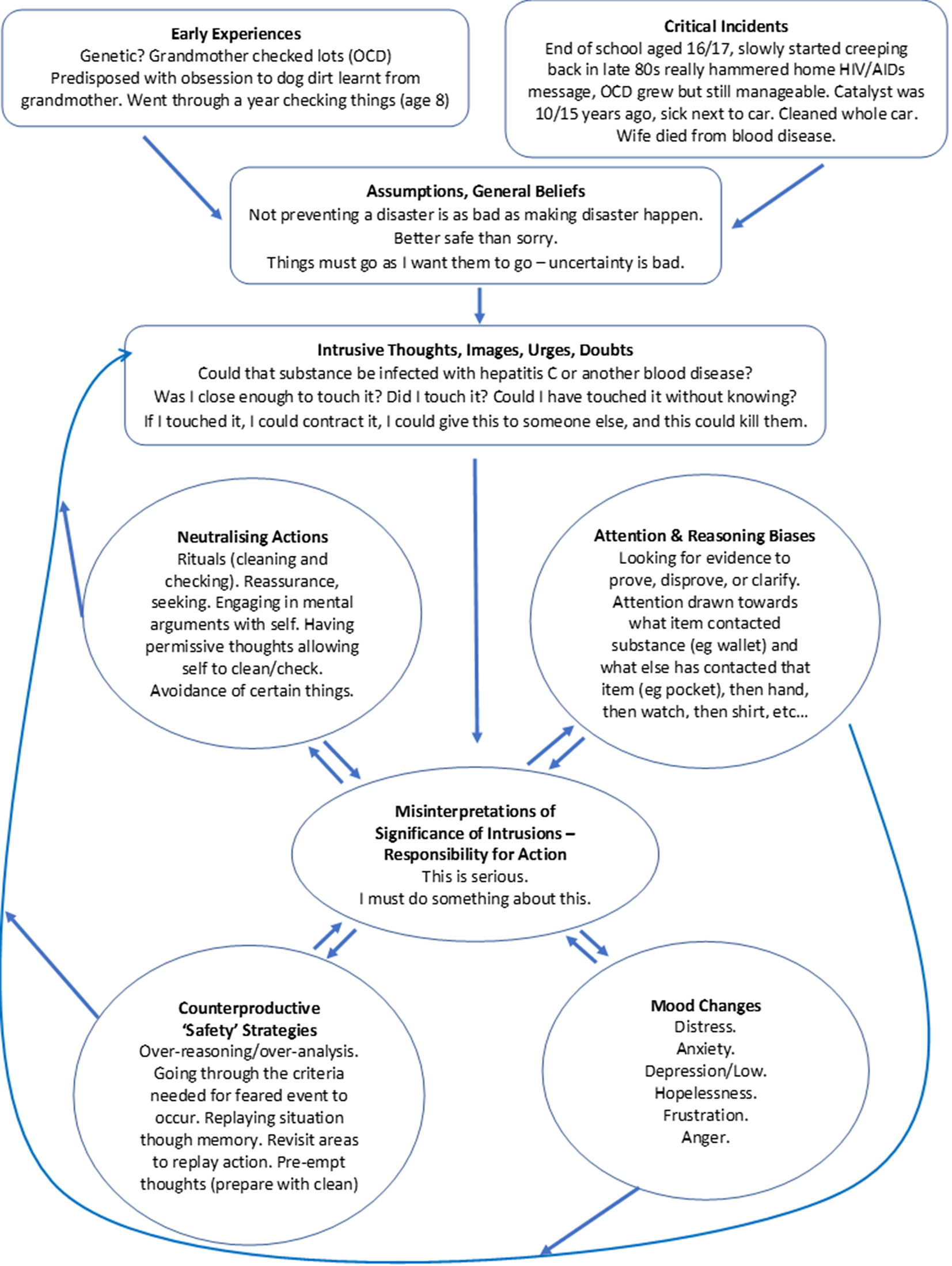

A vicious cycle maintenance model of OCD was utilised to formulate Simon’s experiences (Fig. 1; Salkovskis et al., Reference Salkovskis, Forrester and Richards1998). This formulation conceptualises that intrusive thoughts and other unwanted internal content are developed through misinterpretations/assumptions and then maintained by attentional biases, changes in mood, counterproductive safety behaviours, and neutralising actions (Salkovskis et al., Reference Salkovskis, Forrester and Richards1998).

Figure 1. CBT maintenance model of OCD (Salkovskis et al., Reference Salkovskis, Forrester and Richards1998).

Simon’s formulation reflects that his early life experiences with his grandmother possibly pre-disposed him to a more cautious temperament. Moreover, the critical incidents of the HIV/AIDS media, sick next to his car, and his wife dying from a blood disease each precipitated worsening experiences of OCD. Simon shared that these experiences led him to develop an underlying assumption that ‘not preventing disaster is as bad as intentionally causing disaster’. This belief underpinned Simon’s OCD. Consequentially, Simon had developed a tendency to spot blood-like colours within his environment, to feel anxious, to engage in mental and physical activities to seek clarity about whether he had touched a contaminant, and to complete neutralising cleaning rituals. Each of these maintained his OCD.

Course of therapy

The therapeutic package consisted of eleven 90-minute digitally delivered video therapy sessions which took place at irregular intervals across 9 weeks. The average length of time between sessions was 5.8 days (range 1–8 days). An initial assessment took place during the first two sessions which is referred to as the ‘baseline phase’. Following this phase, seven therapy sessions took place in the ‘intervention phase’. The intervention followed the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2005) guidelines alongside incorporating elements from Veale’s (Reference Veale2007) and Salkovskis et al.’s (Reference Salkovskis, Forrester and Richards1998) research. The core themes of the intervention included:

-

(1) ERP: each session included an in vivo ERP completed by Simon and therapist.

-

(2) Cognitions: time was allocated to alternative ways of viewing OCD (theory A vs theory B), the concept of responsibility, evaluating rules for living, distancing from thoughts, and values.

-

(3) Between-sessions ERP.

Baseline phase: assessment, formulation and goal setting

The first two sessions covered assessment and formulation. In session 1, the idiographic measures were developed, and Simon’s presenting problem and background were discussed. A timeline was created to help facilitate the assessment which Simon was asked to complete between sessions 1 and 2. Time was also allocated in session 1 to discuss the digital platform. The screen-share function was trialled alongside the live messaging function. In session 2, Simon’s timeline was reviewed, further information was gathered, and Simon’s formulation was collaboratively constructed via the screen-share function of the digital platform as the therapist completed a Microsoft Word document. Therapy goals were developed and Simon was introduced to an antecedent, behaviour, consequence (ABC) chart and asked to complete this between sessions.

Difficulties were encountered during the formulation process as additional time had to be dedicated to amending text size, text boxes, to acquiring the skills to freely move the text boxes into the required positions, and to amending the size of the document via the zoom function to ensure necessary areas were visible. These led to the formulation process taking longer than expected and the session feeling disjointed at times.

Despite this, the use of the screen-share function during formulation provided several benefits. Foremost, it facilitated collaboration and connection as Simon and the therapist each had the formulation directly in front of them, as opposed to telephone therapy in which Simon would have not been able to see the formulation or face-to-face therapy in which either Simon or the therapist would have been writing with the other contributing from a distance. For the therapist, this intense shared focus of attention fostered a sense that the therapist and Simon were working together as a team doing something important in the here-and-now, which deepened the therapeutic alliance. Additionally, through using the zoom function the therapist could focus on one aspect of the formulation at a time which controlled the pace and volume of information being mapped out. This facilitated the process in feeling more containing which can be seen as a further benefit.

Session 3: normalising, psychoeducation, and treatment rational

Simon was presented with a list of common intrusive thoughts alongside the percentage of individuals who reported experiencing these within a certain dataset. Simon’s experience of this was discussed Socratically. Simon’s ABC chart was reviewed, and a brief functional analysis was completed on one entry to highlight function of compulsions. Habituation and exposure were introduced, example exposure graphs were drawn and discussed, and the five conditions of ERP were explored. A hierarchy of feared/avoided situations was started. Between sessions, Simon agreed to complete his hierarchy.

The benefits and hazards of videoconference-delivered therapy were also experienced in this session. Positively, as access to the session was provided to Simon via email and SMS text messages, the therapist had a routine digital link with Simon which could be utilised to provide resources following reflection from the previous session. Therefore, the list of common intrusive thoughts was provided to Simon prior to session 3, which allowed for a more detailed and focused reflection in session.

Sessions 4 and 5: ERP, values and ‘theory A vs theory B’

During session 4, Simon’s hierarchy was reviewed and finalised. Simon’s therapy goals were linked to his life values and discussions took place regarding what effective living looks like for him. This provided a further rationale for Simon to engage in ERP. Following this, Simon and the therapist engaged in an in vivo exposure in which the two touched their phones (an item Simon had classified as an outdoor object) and then touched a tablet (an item Simon had classified as an indoor object). Simons subjective units of discomfort (SUDs) were taken every five minutes, and this was placed onto a graph. Between sessions, Simon agreed to complete two ERPs. During session 5, Simon’s between-session ERPs were reviewed, the therapist revisited the list of common intrusive thoughts, and the concept of ‘theory A vs theory B’ was explored in that either Simon was a clumsy and unclean person, or he has a worry issue. Simon and the therapist also engaged in an in vivo ERP in which Simon touched his vape (outside object) and then touched his tablet (inside object). Between sessions, Simon agreed to complete a ‘theory A vs theory B’ worksheet and to complete two ERPs, working up his hierarchy.

The therapist utilised the screen-share function to display the worksheet whilst exploring the concept of ‘theory A vs theory B’. This presented an additional difficulty of utilising this function during videoconference-delivered therapy in that whilst presenting the therapist could no longer see Simon’s video feed. This made it harder for the therapist to ascertain how this experience was landing for Simon as a sharp adjustment had to be made to connect with Simon without access to his facial cues which were previously available. However, alongside this, benefits continued to present themselves. Each of Simon’s ERP activities were graphed in Microsoft Excel and the digital storage of these allowed the therapist and Simon to retrieve and compare each activity with ease during therapy. This facilitated discussion around changes in experiences and maintained a focus on the importance of repeating ERPs often between sessions.

Sessions 6 and 7: ERP, responsibility, and rules for living

During session 6, Simon’s between-session task was discussed and the therapist introduced the theme of responsibility. Simon and the therapist charted people in Simon’s life across two continuums: one of responsibility and one of goodness. The therapist and Simon completed an in vivo ERP in which they touched their wallets (outside object) and then their tablets (inside object). Between sessions, Simon was asked to complete three ERPs, working up his hierarchy. These between-session tasks were reviewed in session 7. During this session the therapist and Simon also discussed Simon’s rules for living in that Simon’s OCD rules have been governing much of his life. A survey was collaboratively constructed to ascertain what rules other individuals utilise to know when to stop checking and washing among various other items. An in vivo ERP was completed in which Simon and therapist placed their phones (outdoor objects) directly on top of their tablets (indoor objects). Between sessions, Simon agreed to disseminate the survey and to complete four ERPs, working up his hierarchy.

Sessions 8 and 9: ERP, rules for living, and distancing from thoughts

The findings from the survey were reviewed in session 8, and Simon was supported in developing new rules for navigating his checking and washing behaviours. These rules were based on numerical fulfilment as opposed to waiting for a felt sense. Simon’s between-session ERPs were also discussed. An in vivo ERP was completed which involved Simon and the therapist touching their phones and then touching their television remote controls. Between sessions, Simon agreed to begin implementing his new rules for checking and washing termination and to record the impact on his quality of life. Simon also agreed to complete four ERPs, working up his hierarchy. During session 9, Simon’s between-session tasks were reviewed, an in vivo ERP was completed in which Simon and therapist touched their wallets and then touched their television remote controls, and mindfulness-based distancing from thoughts exercises were completed. A between-session task was not set at the end of session 9, as session 10 took place the following day due to Simon’s work schedule.

The utilisation of a digital survey platform worked well with the videoconference approach. This increased the efficiency of the application of this therapeutic activity as both Simon and the therapist were able to construct the survey directly onto the online system, disseminate with ease, and collectively review the results. The digital survey platform also created graphical representations of survey responses which were particularly useful. Reflecting on session 9, however, the therapist did report an increase in difficulty around delivering the mindfulness-based distancing from thoughts exercise via the digital platform. It could be the case that experiential therapeutic activities feel differently when delivered digitally in the absence of the full bodily presence of those involved.

Sessions 10 and 11: ERP, maintaining gains plan, and ending

In session 10, the distancing from thoughts exercises were reviewed, an in vivo exposure was completed which involved Simon and the therapist placing their phones directly on top of their television remote controls, and a maintaining gains plan was started. Between sessions, Simon agreed to practise the distancing from thoughts exercise and monitor the impact on his quality of life, to review the maintaining gains plan, and to complete four ERPs. In the final session the between-session tasks were reviewed, an in vivo ERP was completed which involved Simon touching his television remote and then touching his games controller (the final remaining object which remained an ‘inside object’), and the maintaining gains plan was discussed and finalised in detail.

Simon’s package of therapy came to a planned end as the therapist was leaving the service. As Simon was making good progress on his outcome measures and reporting feeling better, a month’s therapy break was agreed before Simon accessed a follow-up check-in with a different therapist.

Outcome

Visual analysis

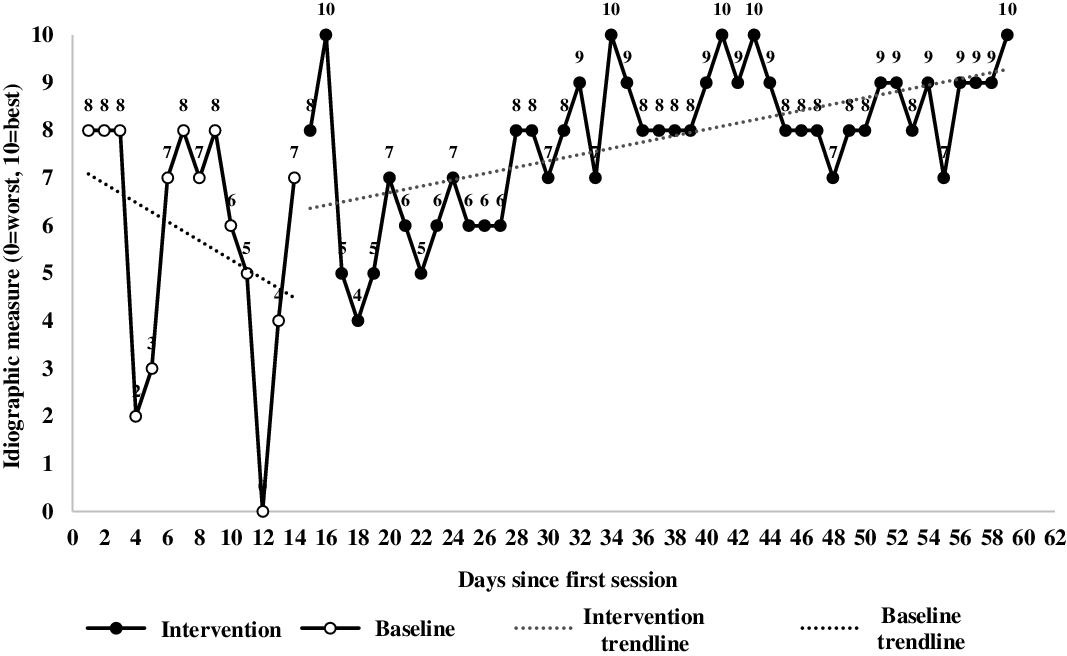

Figure 2 presents the complete dataset for the ‘Motivation’ measure. Visual examination indicates that Simon reported feeling increasingly more motivated to overcome his OCD during the intervention phase. This trend of improvement is juxtaposed to the deterioration within the baseline phase. Additionally, Simon’s scores were much less varied (between 7 and 10) in the final 4 weeks of the intervention phase, compared with the baseline phase (between 0 and 8).

Figure 2. ‘Motivation’ complete dataset.

Figures 3 and 4 present Simon’s ‘Thoughts’ and ‘Behaviours’ measures. Visual inspection indicates that Simon reported feeling increasingly free from OCD-related obsessional thoughts and compulsive behaviours as the intervention progressed. Simon’s baseline scores improved on each of these measures; however, baseline trend and autocorrelation analysis indicate that these baselines are stable enough to suggest the intervention positively impacted both measures. However, significant autocorrelation scores found within the complete datasets suggest these visual inspections should be interpreted with caution due to potential bias established by serial-dependency (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Weinrott and Vaught1978).

Figure 3. ‘Thoughts’ complete dataset.

Figure 4. ‘Behaviours’ complete dataset.

Baseline idiographic data

Visual inspection revealed that the ‘Thoughts’ and ‘Behaviours’ measures each reported a gradual improvement during baseline whereas the ‘Motivation’ measure regressed. It is important to assess the strength and significance of baseline trends to determine the extent to which the changes reported following visual analysis can be reliably attributed to the introduction of the intervention. A Kendall’s tau-b (τ b; Kendall, Reference Kendall1938) was utilised to analyse changes in the baseline data. The results indicated that Simon’s ‘Motivation’ baseline demonstrated an insignificant mild negative change (τ b = –.332, p = .114), and the ‘Thoughts’ and ‘Behaviours’ baselines demonstrated insignificant weak positive changes (τ b = .251, p = .237 and τ b = .219, p = .306, respectively). These scores suggest that changes in baseline scores were weak, therefore significant changes between phases can be attributed to the change methods within the intervention.

Autocorrelations

Autocorrelation calculates the association between variables across two consecutive intervals. The calculation measures how the lagged version of a value is related to the original version in a time series. These calculations are important within time series analysis as serial dependency can reduce the reliability of the inferential statistics applied. Autocorrelations were also performed for the baseline and intervention phase together. Lag 1 results from all three idiographic measures were significant, ‘Motivation’ autocorrelation .560 (SE = .144) Box–Ljung 15.067 (p = .001), ‘Thoughts’ autocorrelation .533 (SE = .144) Box–Ljung 13.639 (p = .001), and ‘Behaviours’ autocorrelation .368 (SE = .144) Box–Ljung 6.506 (p = .011). These findings suggest serial-dependency with each data-entry point influencing the following score. Although this is expected as positive outcomes are often incremental in therapy, the violated assumption of independence influences the reliability of visual analysis and Mann–Whitney U results (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Weinrott and Vaught1978).

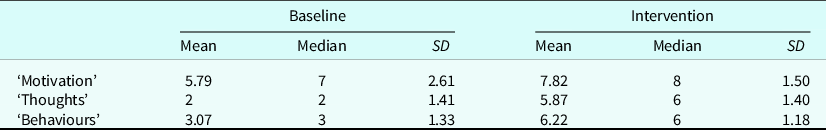

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for each idiographic measure during the baseline and intervention phase. The table demonstrates that for all three idiographic measurements, both the mean and median average scores increased in the intervention phase and the standard deviation decreased.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

Independent samples Mann–Whitney U-tests were utilised to further examine changes between the baseline and intervention stages: ‘Motivation’ U = 474.500 (SE = 54.842; p = .004), ‘Thoughts’ U = 610.000 (SE = 55.364; p = .001), and ‘Behaviours’ U = 606.500 (SE = 55.185; p = .001). These significant results provide evidence supporting the efficacy of the intervention for facilitating change. However, as the autocorrelation calculations indicated serial dependency, the assumption of independence has been violated. Therefore, these results should be interpreted with caution.

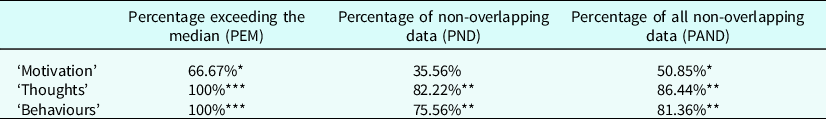

Non-overlap analysis

Table 2 details the results following non-overlap analysis which was performed in line with Lenz’s (2013) principles for calculating effect sizes in single case experiment research designs.

Table 2. Non-overlap analysis

*Mild effect; **moderate effect; ***very effective (Scruggs and Mastropieri, Reference Scruggs and Mastropieri1998).

The percentage exceeding the mean (PEM) score calculates the number of data-entry points in the intervention phase which exceed the baseline median score. Ma (Reference Ma2006) suggests the baseline median fittingly reflects the baseline data and proposed that if interventions were to have no impact, data points would oscillate around the baseline median with each having a 50/50 chance of surpassing or falling below this. Utilising this calculation as a reflection of intervention efficacy, the intervention was considerably effective for the ‘Thoughts’ and ‘Behaviours’ measures and moderately effect for the ‘Motivation’ measure.

The percentage of non-overlapping data (PND) score calculates the number of intervention data points which are an improvement compared with the best score in the baseline phase (Scruggs et al., Reference Scruggs, Mastropieri and Casto1987). Scruggs and Mastropieri (Reference Scruggs and Mastropieri1998) detail a cut-off point of 50% for PND scores, stating that scores greater than this indicate efficacious change. This provides a coherent quantitative measurement of intervention effectiveness. Utilising this measurement, the intervention was highly effective for the ‘Thoughts’ and ‘Behaviours’ measures, but had limited effect for the ‘Motivation’ measure.

Finally, the percentage of all non-overlapping data (PAND) score calculates the number of data-entry points in the intervention phase requiring removal to ensure that no data-entry points overlap with the baseline phase (Lenz, Reference Lenz2013; Parker et al., Reference Parker, Vannest and Davis2011). PAND scores consider all data points equally which aligns this interpretation with effect size calculations like R (Lenz, Reference Lenz2013). The PAND measurements establish the intervention was moderately effective for the ‘Thoughts’ and ‘Behaviours’ measures and marginally effective for the ‘Motivation’ measure.

All three of these evaluation methods indicate the intervention produced a considerable effect on the ‘Thoughts’ and ‘Behaviours’ measures, which suggests the intervention contributed towards Simon feeling freer from OCD-related obsessive thinking and compulsive behaviours.

Nomothetic data

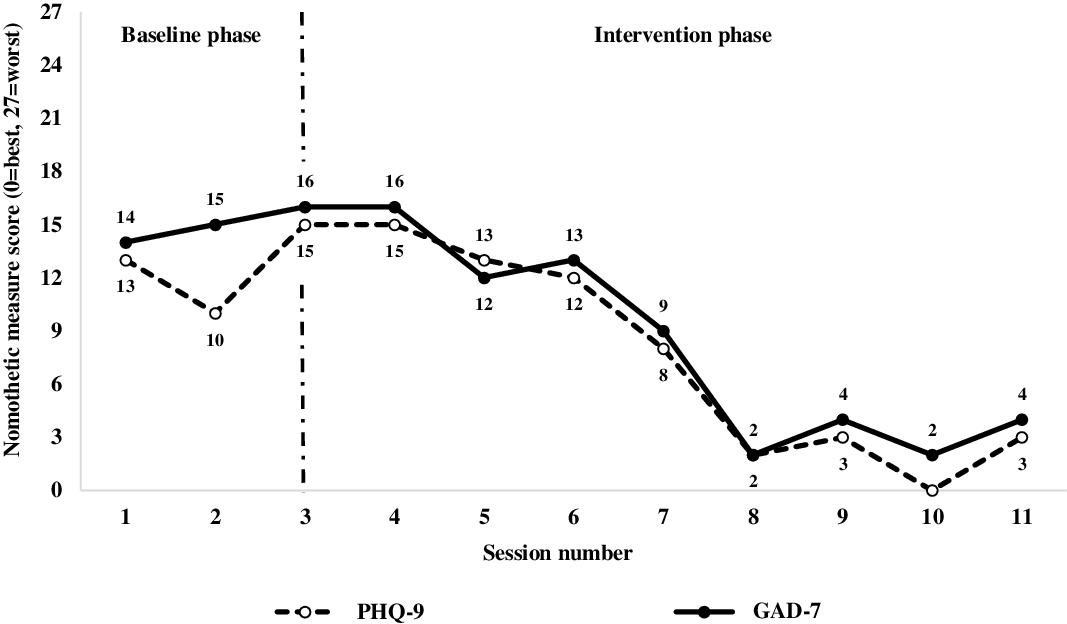

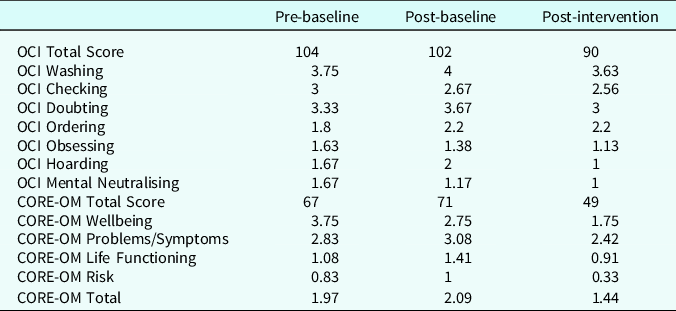

Nomothetic data is presented in Fig. 5 and Table 3. The PHQ-9 and GAD-7 were collected on a session-by-session basis. The OCI and CORE-OM were completed at pre-baseline, post-baseline, and pre-intervention.

Figure 5. PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores.

Table 3. OCI and CORE-OM scores

Reliable and clinically significant change

The reliable change index (RCI) is the degree of change necessary for variations to be accepted as beyond the possibility of chance (Jacobson and Truax, Reference Jacobson and Truax1991). Simon’s PHQ-9 score reduced from a peak of 15 to 3, and his GAD-7 score reduced from a peak of 16 to 4; these reductions of 12 are deemed reliable change (NHS England, 2019). Additionally, Simon’s post-interventions scores on the CORE-OM subscales of ‘Wellbeing’, ‘Problems/Symptoms’, ‘Risk’ and ‘Total’ surpassed the necessary RCI, when compared with a mean total of the pre-baseline and post-baseline assessments (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Mellor-Clark, Margison, Barkham, Audin, Connell and McGrath2000). Simon’s total OCI score did not meet reliable change criteria.

Clinically significant change is understood as the change in severity of score from above clinically significant levels of symptomatology to below clinical thresholds (Jacobson et al., Reference Jacobson, Follette and Revenstorf1984). Simon’s PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores were below 10 for the final five sessions of the intervention phase, indicating consistent clinically significant change (NHS England, 2019). Simon’s scores on the CORE-OM subscales of life functioning and risk also reported clinically significant changes. The OCI did not report clinically significant change.

Qualitative reflection, progress towards goals, and follow-up

At the end of therapy, Simon and the therapist reviewed the therapeutic package. Simon’s reflections were consistent with his outcome measures. Simon stated that he felt more driven to overcome his OCD and that his quality of life had improved. Simon emphasised this by sharing he had met some friends at a pub which is something he had not done for almost a year.

Reviewing Simon’s goals, he shared that he felt that his OCD was on a downward trend, that he had started to spend less time cleaning, and that the cognitive aspects of the therapeutic package were particularly valuable to him as these were new compared with his previous therapeutic experiences. In line with the OCI scores Simon shared he felt OCD remained a large part of his life and that he needed to continue completing ERPs and progressing up his hierarchy.

At follow-up Simon reported to have continued his progress with his ERPs, but expressed difficulty distancing from his thoughts. Simon was offered a package of acceptance and commitment therapy, which he accepted.

Discussion

This structured case report examined the efficacy of an 11-session videoconference-delivered CBT intervention for blood contamination-based OCD. The PEM, PND and PAND results report varying scores, therefore it is important to explore the most applicable for this research. Notably, PEM scores can prove inaccurate if baselines report trends towards improvement as in the ‘Thoughts’ and ‘Behaviours’ measures (Vannest and Ninci, Reference Vannest and Ninci2015). Additionally, PND is insensitive to outliers and cannot provide useful measurements if baseline scores are in the higher or lower ranges of scales; the former is reflected in the ‘Motivation’ measure (Vannest and Ninci, Reference Vannest and Ninci2015). However, PAND provides robust and effect non-overlap measurements when over 20 data points are collected at consistent time points with no outliers (Lenz, Reference Lenz2013). These conditions are reflected in this research.

The PAND results indicate the intervention was effective for Simon’s ‘Thoughts’ and ‘Behaviours’ measures, but failed to impact the ‘Motivation’ measure. This may be because Simon reported periods of relatively high levels of motivation during the baseline stage (e.g. 8/10) and therefore effective change on this measure was less likely and less pertinent, compared with the other measures. However, in the 14 data-entry points during the baseline phase, the ‘Motivation’ measure varied between 0 and 8 whereas scores across the final 30 days of the intervention phase varied between 7 and 10. Therefore, visual inspection would suggest the digital intervention was successful in improving the consistency of Simon’s motivation to overcome his OCD.

The nomothetic assessments provide greater insight into the efficacy of the digital intervention. The CORE-OM indicates substantial benefits across all five subscales. The OCI demonstrates the intervention did not produce clinical or reliable change, despite all subscales (excluding ‘Obsessing’) reducing in severity and ‘Washing’, ‘Checking’ and ‘Doubting’ displaying trends towards clinical change. It is notable that the total score on the OCI reduced from 104 to 90, which indicated that Simon remained symptomatic at the end of treatment. There are several possible reasons why remission was not achieved. It could be that the intervention terminated too early, and that Simon required more than nine 90-minute intervention sessions. Although the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2005) guidelines recommend up to 10 hours of CBT, it is possible that CBT for OCD delivered over a digital platform may require a greater number of sessions to generate efficacious change. This suggestion is corroborated in research examining digitally delivered CBT for OCD with Matsumoto et al. (Reference Matsumoto, Sutoh, Asano, Seki, Urao, Yokoo, Takanashi, Yoshida, Tanaka, Noguchi, Nagata, Oshiro, Numata, Hirose, Yoshimura, Nagai, Sato, Kishimoto, Nakagawa and Shimizu2018) examining a 16-session therapeutic package. Similarly, Aspvall et al. (Reference Aspvall, Andersson, Melin, Norlin, Eriksson, Vigerland, Jolstedt, Silverberg-Morse, Wallin, Sampaio, Feldman, Bottai, Lenhard, Mataix-Cols and Serlachius2021), Herbst et al. (Reference Herbst, Voderholzer, Thiel, Schaub, Kaevelsrud, Stracke, Hertenstein, Nissen and Kulz2014) and Kyrios et al. (Reference Kyrios, Ahern, Fassnacht, Nedeljkovic, Moudling and Meyer2018) each examined 16, 14 and 12 sessions of internet-based CBT for OCD, respectively. Therefore, it could be that this nine-session package remained too short to cultivate remission. Alongside this, the context of the COVID19 pandemic may have also contributed to a lack of remission. Guzick et al. (Reference Guzick, Candelari, Wiese, Schneider, Goodman and Storch2021) and Grant et al. (Reference Grant, Drummond, Nicholson, Fagan, Baldwin, Fineberg and Chamberlain2022) have each conducted reviews which highlight that individuals with contamination-based OCD symptoms have experienced increased difficulty during the COVID19 pandemic. Such experiences are likely to be particularly visible on Simon’s OCI measure. Subsequently, this may have mediated the impact of the intervention. Finally, as Simon had shared that he had previously completed packages of exposure therapy but these had all led to a recurrence of symptomatology, Simon may have benefited from experiencing a different therapeutic approach such as acceptance and commitment therapy (Bluett et al., Reference Bluett, Homan, Morrison, Levin and Twohig2014) or inferenced based therapy (Visser et al., Reference Visser, van Megen, van Oppen, Eikelenboom, Hoogendorn, Kaarsemaker and van Balkom2015).

A significant strength of structured case reports which apply time series analysis is the precision and depth of measurement. The idiographic measures highlight that data-entry point 40 was the final ‘trough’ for both the ‘Thoughts’ (3/10) and ‘Behaviours’ (4/10) idiographic measures before these levelled out around 6–7/10 until the termination of the intervention phase. The therapy sessions surrounding this data-entry point were session 6 which took place on day 36 and session 7 which took place on day 42. It is therefore possible that the content delivered in these sessions was valuable in facilitating Simon’s progression on these measures. The PHQ-9 and GAD-7 add greater depth, detailing that between intervention sessions 4 and 6, both scores dropped by ≥10 points from above clinical ranges to well below. This provides further evidence to suggest that the content of sessions 6 (ERP and CBT for responsibility) and 7 (ERP and CBT for evaluating rules for living) could be integral aspects for facilitating change within this digitally delivered intervention.

Implications for therapy and recommendations

High drop-out rates are associated with the use of ERP (McKay, Reference McKay2008); meanwhile a lack of clinician confidence can be a barrier to utilising remote therapies (Faija et al., Reference Faija, Connell, Welsh, Ardern, Hopkin, Gellatly, Rushton, Irvine, Armitage, Wilson, Bower, Lovell and Bee2020). It is therefore understandable that the concept of utilising digitally delivered CBT for OCD could be a source of anxiety for clinicians. These results provide preliminary practice-based evidence demonstrating that a digitally delivered CBT intervention for blood contamination-based OCD can have considerable positive effect. It is also hoped that the explanations regarding how the digital platform was utilised within this study can help clinicians feel more confident in delivering digital CBT for OCD.

A need has also been highlighted to improve the features of the secure online platforms currently available for digital therapy. It would be beneficial for the therapist to be able to share screen content with the patient whilst also being able to see the patient’s video feed. This feature was not available on the digital platform utilised within this structured case report which created difficulties for the therapist.

The study also demonstrates that practice-based time series methodologies can be efficiently and effectively applied to digital therapy. Clinicians providing digital therapy should be mindful of this and consider how practice-based evidence can be collected in their routine practice to prevent rich and useful real-life data being lost.

It can be argued that patients like Simon benefit from being able to access digitally delivered CBT over and above face-to-face therapy for several reasons. Foremost, the impact of Simon’s OCD was most prevalent inside his own home due to his rules around having inside and outside objects. Being able to support Simon to engage in ERPs at home seemed to foster therapeutic change relatively quickly. Therefore, for clinicians who cannot incorporate home-visits into their working schedule, digital therapy could be seen as a useful alternative. Additionally, Simon reported having difficulties travelling to and from destinations due to his extensive cleaning routines. This presented an additional barrier for Simon to attending clinic. Being able to meet Simon digitally, develop a working alliance, and begin making therapeutic progress prevented the risk of Simon not attending or attending in a pre-occupied state. It was also easier to address Simon’s cleaning rituals further down the line in therapy. Therefore, digital therapy should be considered as a viable option for patients with OCD finding it difficult to attend clinic.

Limitations

This study cannot comprehensively conclude that the intervention was the sole agent of change. This is because two of the idiographic measure reported improving baseline scores and ‘AB’ time series designs can be insensitive to the impact of confounding variables. It would be recommended for further studies to include a follow-up within an ‘ABC’ design. This would produce greater insight into the impact of the intervention. Moreover, single-subject designs often exhibit precision and depth but lack scope as the information provided is from an n = 1 population. Therefore, it could be worthwhile for further studies to employ a single-case series approach (Murphy and Bryan, Reference Murphy and Bryan1980), to increase the scope of findings.

A further limitation is the choice of assessment measures. Foremost the idiographic assessment measurements could have been more pertinent if they had been linked to Simon’s therapy goals, for example measuring the extent to which Simon felt confident in managing his OCD following the termination of therapy. Equally, it could have been beneficial for these measures to be more specific such as measuring Simon’s urge to wash his hands over and above the current government guidance. It is also of note that no interview-based assessment measures were utilised; this could have added greater depth and clarity to the quantitative data. Alongside this, it could have also been beneficial to include the clinician’s voice through assessments such as the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale or the Clinical Global Impressions Scale, as opposed to relying only on patient report.

Additionally, only one intervention session was observed by a supervisor to assess for fidelity to the ERP and CBT theoretical frameworks and treatment philosophy. However, neither the therapist nor the supervisor were trained CBT therapists. Therefore, further studies should seek to review the content of intervention sessions to ensure fidelity to the model.

Finally, Simon’s difficulties were fortuitous for the remotely delivered format in that ERPs could be successfully completed via the video communication platform by placing his phone on his remote control, for example. However, it is unlikely that this success could generalise to a broad set of OCD situations.

Conclusion

This study aimed to examine the effectiveness of an 11-session digitally delivered CBT intervention for a working aged adult experiencing blood contamination-based OCD. Findings suggest the intervention was successful for Simon. The standardised assessment measures suggest reliable change was made on all CORE-OM subscales, the PHQ-9 and GAD-7, and clinically significant change was made on the CORE-OM subscales of life functioning and risk, the PHQ-9, and GAD-7. The OCI reported a trend towards clinically significant change. The idiographic measures suggest the intervention helped Simon to feel he was living his life in a manner which was freer from his OCD-related obsessive thinking and compulsive behaviours. More controlled research further up the scientific hierarchy is now required to establish the use of digital CBT for OCD, with particular reference to the change elements of combining ERP and CBT for responsibility and evaluating rules for living.

Key practice points

-

(1) Two major barriers to adopting remote therapy are clinician anxiety and a lack of belief in its efficacy compared with face-to-face therapy.

-

(2) This case study describes a digitally delivered CBT for OCD intervention which attained positive results on the idiographic, nomothetic and qualitatively collected outcome measures.

-

(3) The study explores ways to optimise digital platforms and difficulties for clinicians to be aware of.

-

(4) Current digital therapy platforms would benefit from improvement; until then the screen-share function should be utilised tactfully and in moderation.

-

(5) Digital therapy should be seen as a useful and viable option for the provision of CBT for OCD.

Data availability statement

The author confirms that the data supporting the findings of this study are readily available within the article.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted as part of the author’s clinical psychology training programme at the University of Sheffield. The author would like to thank tutors at the University of Sheffield for their advice throughout. The author would like to thank Dr Nicolas Wilkinson for his support, mentoring and guidance, not only during this single-case study but in the author’s wider professional journey to date. The author would also like to thank Dr David Saxon for support with data analysis.

Author contributions

Jack Purrington: Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Investigation (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Validation (lead), Visualization (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead).

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

The author has no conflicts of interest with respect to this publication.

Ethical standards

This project was completed by collecting data from routine practice and is being written up retrospectively; as such, it did not obtain ethical approval prior to commencement. Nevertheless, all procedures contributing to this work complied with the BPS code of ethics and conduct and the HCPC standards of conduct performance and ethics. Consent was obtained to complete the therapeutic work. Following the completion of the therapeutic work, informed consent was obtained for this piece of work to be written up for publication in a peer-reviewed journal. Consent was seen as an ongoing process which was reviewed regularly.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.