Klang

Klang is a central concept in Billone's music. Like Rebecca Saunders and Mark Andre, the composer belongs to the generation born during the 1960s, who, in a clear and uncompromising manner, put Klang at the centre of their musical thought. ‘Klang is my material’,Footnote 2 says Billone, who understands by the term more than just the positivistic sense of audible physical vibrations: ‘Two bodies, that approach each other through Klang – that could be a good definition of Klang. Klang for me is not just acoustic reality’.Footnote 3 Although Billone's is a holistic understanding of Klang that allows no separation between the physicality of music-making and communication from performer to listener, the unusual Klang-scapes of his music still offer a starting point from which to explore the specifics of his aesthetic.

The outward appearance of his works often provides a characteristic underlying timbral structure of instrumental line-up and playing technique. This is seen, with paradigmatic clarity, in his now five pieces for solo percussion. Mani. De Leonardis (2004) demands the unusual set-up of four car springs and two large glasses, while Mani. Matta (2008) exhibits the sounds of wooden percussion instruments (I will discuss the composer's distinctive titles later). In the latter piece, the marimbaphone is central, its already rather dull sound strengthened by frequent glissandi over the wooden keys. In stark opposition to the wooden sounds of Mani. Matta is Mani. Dike (2012), a kind of ‘celebration of the soundworld of metal’, as the composer writes in his work commentary. A large, horizontally laid Thai-Gong and two low plate bells are played with two Tibetan singing bowls, the latter used as mallets, thus extending the body of the performer into the instrumental realm, as indeed does the one China gong attached to their chest. This set-up is then radically reduced in Mani. Gonxha (2011) to just the two singing bowls. Mani. Mono (2007) also makes do with an unusually reduced sound source: one single spring drum, around which a fascinating and distinctive sound panorama is developed. The characteristic soundworld of the triptych for electric guitar, Sgorgo Y, Sgorgo N and Sgorgo oO (2012–13), is due to the unusual playing technique: the sounds are created only by the left hand.

Billone's music regularly shows an affinity with the low register. The early ensemble piece KRAAN KE.AN (1991) focuses in quite an extreme manner on low sounds with its ensemble of three low voices, two percussionists who play thunder sheets (also over a bass drum), an electric guitar, a viola, four cellos and two double basses. The same can be said of other early ensemble pieces, like AN NA and ME A AN. Even in later pieces, Billone's fascination for low registers does not decline, as shown by his seven pieces for solo bassoon and the 70-minute duo 1 + 1 = 1, for two bass clarinets (2006). The breadth and depth of these works – six bassoon solos in the years 2003–04 alone, three extensive guitar solos in the years 2012–13 – show a persistent, almost obsessive, interest in particular constellations.

Energetic Klang typology

Although Billone's works often exhibit a characteristic timbral base colour, they are anything but monochrome. Rather, they display wide timbral spaces that are based on the exposition of different Klang-types, their differentiation and reciprocal entanglement.Footnote 4 This is not the result of abstract plans but is gleaned by concrete research into the instrument in question:

I sense, for example, how a metallic vibration could be connected to another Klang by being touched by an object. This I feel at once. Or I try to find it. In this way a spontaneous knowledge forms that soon is no longer spontaneous; so that one recognises directly after the experience whether relationships are even possible, how they function and how one could use them. In all honesty, there is no system here. There is nothing more than experience built up step by step, day by day, month by month, year by year.Footnote 5

Even if Billone's music does not rest upon any strict pre-compositional system, its basic timbral structure allows regular principles to be recognised. The compositional space is often defined through sounds with different degrees of energetic presence: at one end of a smooth continuum stand soft, often noisy and only slightly resonant sounds; at the other end are powerful, often discordant or noisy vibrations with complex overtone spectra; while the fully resonant, traditional tone of traditional European classical music regularly assumes the middle position. Unlike music from the ‘spectral’ tradition, Billone's Klang-typology rests more on the strength of vibrations than on their periodicity. Nor can meaningful differentiations be made between harmonic sounds with partials in a whole-number relationship (‘pure’ sounds), inharmonic sounds (‘multiphonics’) and sounds with irregular modes of vibration (‘noisy’ sounds).

Pierluigi Billone has developed a wide range of different degrees of sound energy presence for different instruments. In the 80-minute duo Om On, for two electric guitars (2015), the gentle electronic background noise, usually perceived as a distraction, functions as the timbral starting point to which the piece constantly returns; yet it also develops a broad and fascinating soundscape from specific pitches with differing degrees of clarity and presence to sharp scratching. In 1 + 1 = 1, the sound spectrum ranges from quiet, delicately underblown sounds to discordantly piercing multiphonics, via richly sonorous pitches. Billone's solo percussion pieces are similarly shaped by timbral resonance rather than harmonicity.

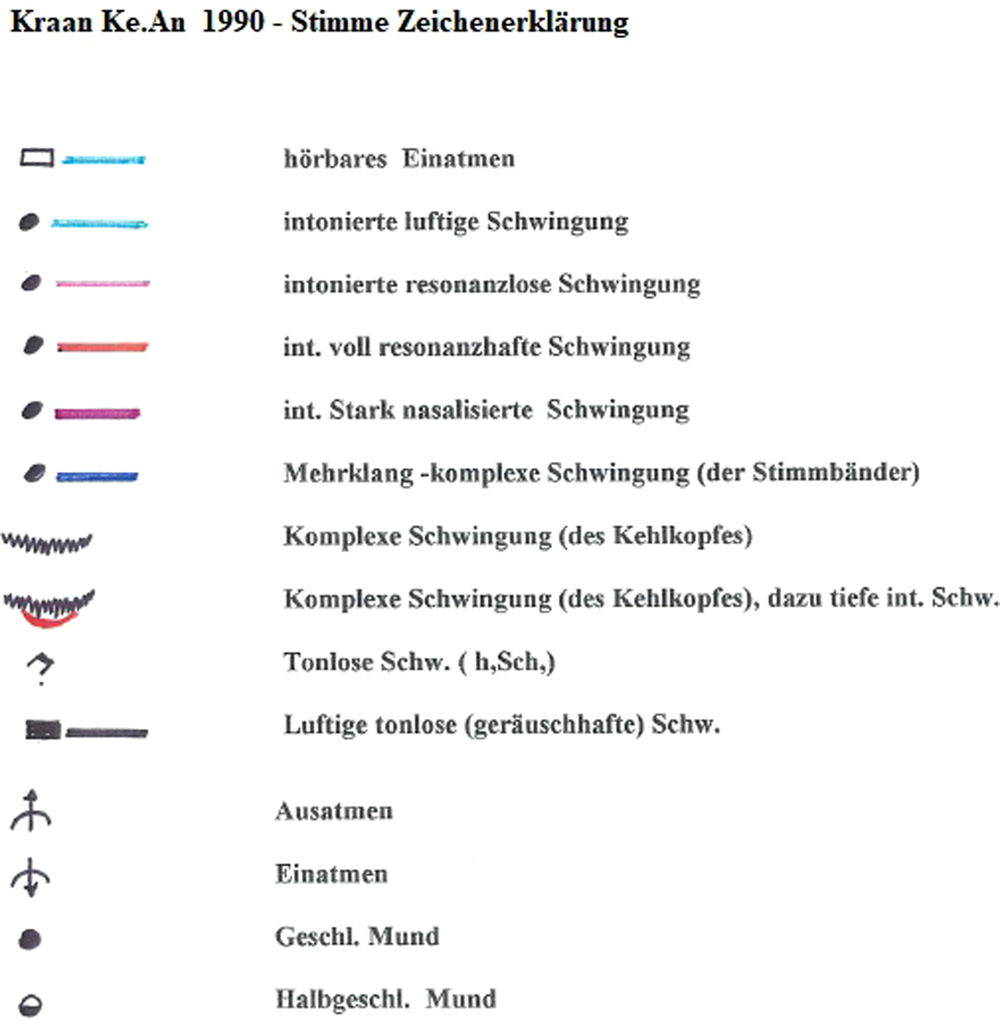

The works for stringed instruments and voice are particularly detailed in the differentiation of their sound-energetic states, as the methods of sound production involved exhibit especially flexible and continuously modifiable sound spectra. As early as KRAAN KE. AN (1991) Billone had articulated a broad spectrum of sounds with different strengths of vibration, including pitchless noisy sounds, minimally resonant sounds with tones, ‘fully resonant’, ‘strongly nasal’ and multiphonic-like complexes, and noisy complexes that are achieved by putting extreme pressure on the larynx (see Example 1). In other pieces, such as KE AN. Cerchio, for low voice (1995, revised 2003), Billone generally continues to use these classifications.

Example 1: Pierluigi Billone, KRAAN KE.AN, explanation of vocal notations (1991).Footnote 6

Billone's three solo pieces for string instruments, ITE KE MI, for solo viola (1995), UTU AN.KI LU, for solo double bass (1996), and Equilibrio. Cerchio, for solo violin (2014), reveal a comparable typology that is based on how vigorously the strings are made to vibrate.

Klang notation in colour

Often, timbral conditions are symbolised by different colours in Billone's scores. Not only are noteheads and special symbols coloured in but so are additional lines that indicate sound shape and contact position. These colour markings should not be understood as attempts to give a precise visual translation of the sounding result; rather, they have a more pragmatic function: to avoid ambiguities through clear notation of the intended sound quality. They are not used extensively; instead their primary use is at points of potential misunderstanding or in particularly meaningful places. Instead of notating properties such as finger pressure, finger position, contact location and bow pressure in systems independent of each other, as many protagonists of ‘New Complexity’ do, Billone's music is based on a mixture of conventional notation and special signs that are inserted as required. As Example 2, an extract from Equilibrio. Cerchio, shows, the finger position of the left hand is displayed as traditional ‘resulting notation’ (along with shorthand for glissandi and double stops), unusual finger pressure is displayed through special noteheads, the contact position is notated through a mixture of sketch-like space notation and written additions and the abstract categories of bow pressure are captured in the coloured markings of the resulting sound (see Example 2). Billone's maxim is to notate as clearly, but also as economically, as possible, and he forgoes the division of his music into bars in order to emphasise its flowing character, despite the mostly classical rhythmic values of his music.

Example 2: Pierluigi Billone, Equilibrio. Cerchio, p. 5, lines 3 and 4 (2014).

Continuous transformation of sound

Pierluigi Billone is concerned ‘fundamentally [with] a continuous transformation of sound’.Footnote 7 This conception of sound means that Billone does not place pitches and sounds like bricks one on top of the other in a kind of modular system; rather, he regards Klang as a more organic, endlessly changing entity. In many works, static passages are the exception, the sounds conceived as always in flux. This can be most readily observed in his early compositions and the works for string instruments, the latter being particularly suited to continual changes.

ITE KE MI, for example, when considered from a distance has the effect of one single large band of sound, though the nearly half-hour piece is anything but monochrome. Different timbral and structural degrees of presence and the intermittent appearance of arresting sonic textures and rhythmic patterns lend the piece a clear formal profile, yet these moments that create differentiation are, at the same time, enclosed and overlaid by a tendency towards continuous transformation. The result is an unremittingly changing sound surface with different inner structures that appears to flow constantly onward, only interrupted occasionally by sudden general pauses. Beyond these there are almost no rests and the numerous, long phrasing marks rob the rhythmic patterns of their definition, so that the (sometimes less than clearly defined) motives operate rather like the inner animation of longer sounds. The particular articulation achieved by the bowing also contributes significantly to this emphasis on surface character. The bowing almost exclusively affects the modulation of the speed of transformation (for example, dynamic changes through bow speed or changing contact position at different speeds) and rarely causes the separation of sound events, giving the impression that the bow is in continuous motion from the beginning to the end of the piece.

UTU AN.KI LU and the later Equilibrio. Cerchio show a similar surface disposition, though the latter has a stricter rhythmic structure. In the latter piece, for solo violin, the categories of timbral transformation are well demonstrated. Billone's music has an inclination to glissando as a continuous alteration of pitch. In Equilibrio. Cerchio this aspect is considerably strengthened by the fact that it is made up almost exclusively of double stops. These often do not move in parallel; instead it is often the case that only one of the two pitches change, or both glissando in different ways, which greatly increases the flowing, unstable character of the sound. Dynamic developments and, in particular, modifications of the partial structures are also a significant factor regarding continuous timbral change, which is primarily achieved through bowing: changes of contact position, the bow speed and pressure lead to continuous timbral change and create noisy sounds, full of pitches or inharmonic, aggressive spectra that can almost arbitrarily transform into each other.

These principles of continuous modification are applied to other instruments in accordance with their particular properties. Glissandi appear in trombone and electric guitar at an almost obsessive frequency, and in a somewhat toned down form on woodwinds; changes of the spectral sound shape are realised on brass instruments by (non-stop) changes of mute as well as simultaneous singing and playing, and on woodwinds by the most varied kinds of multiphonic, though Billone favours multiphonics that allow a slow glide in and out. This central aspect of his composition, continuous timbral processes, is also a substantial reason for the unusually low importance attributed to the piano in his oeuvre. There are no piano solo pieces and the instrument only occasionally appears in his ensemble works.

Textures and forms

Pierluigi Billone's music is often laminar but rarely static, its confluence of planarity [Flächigkeit] and timbral transformation tending towards Texturklang, the third category from Helmut Lachenmann's famous Klang-typology.Footnote 8 It is described as very variable and unpredictable on the microscale, and its course, from a bird's eye view, tends to be perceived ‘not as a process anymore, rather as an arbitrarily extendable situation’, because the timbral development and progress of time are partially independent of each other.Footnote 9

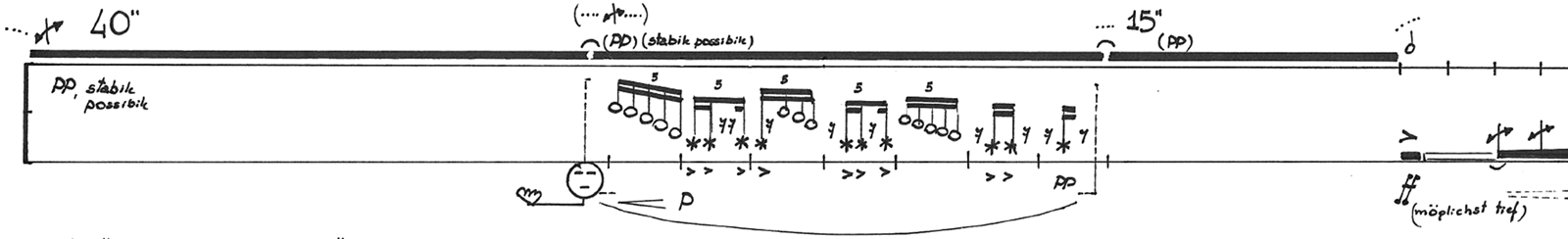

Billone's handling of Klang textures not only differs from work to work but is also subject to an overarching biographical development. In general, his early works consist predominantly of moving lines that combine into varying sound surfaces, while the later compositions mostly exhibit a considerably larger textural bandwidth. The early composition KRAAN KE.AN is rhythmically differentiated but its rhythmic contours are blurred by the use of ‘soft’ rhythms such as triplet divisions and the avoidance of clear periodicities and hard articulations (see Example 3). As a consequence, rhythm does not have a distinct profile but surrenders itself to the service of constant transformation of sound. Through the surface overlaying of lines that are in themselves very similar, a low, slowly meandering band of sound emerges, like a giant beast lumbering forward in slow motion. The latent one-dimensionality of the texture means that the underlying timbral structure is unusually significant: the number and type of voices, their changing timbral structure and the connected textural density are the most important formal markers of the piece.

Example 3: Pierluigi Billone, KRAAN KE. AN, bars 6–7 (1991).

Although the underlying timbral structure of later pieces is also consistently significant, this is emphasised by the addition of other aspects, in particular the expanded textural range. The variation in rhythmic profile is particularly noteworthy: rhythmic patterns not only animate the Klang but also have an intrinsic value as rhythmic motives. Also important, however, are the intermediary stages that connect these two rhythmic profiles and provide moments in which their functions are difficult to separate. A frequent pattern in Om On consists of muffled and weak low pitches that transition to chains of figures that are played so softly they are heard less as individual pitches and more as discontinuous steps along a glissando (see Example 4).

Example 4: Pierluigi Billone, Om On, bars 390–94 (Guitar 2 part only) (2015).

In Billone's later compositions the basic timbral structure is not the only element of formal and structural importance. Rather, this aspect is folded into a higher level category of timbral-structural unity [klangstrukturellen Einheitlichkeit]. In a work like KRAAN KE.AN the speed and strength of timbral transformations remain at a predominantly constant, middle level, with rather moderate deviations; pieces such as Equilibrio. Cerchio, Mani. Mono and Om On display a far wider range of transformational possibilities.

Static sounds in which ‘nothing’ changes are rare, although they are dramaturgically important. More often, however, minor variations, such as slow glissandi or gradual timbral variations, appear. Variety is achieved through irregular changes within the sound structures: the opening of Equilibrio. Cerchio switches between different Klang situations every few seconds – fully resonant double stops, shimmering runs played sul ponticello or delicate traces of sound – either with direct transitions or general pauses. The second page of the score exhibits a clearly static character. The music insists predominantly on the two downwardly detuned lower strings before the material presented at the opening is gradually developed and expanded. At the end of the piece moments of dogged insistence occur, which are nonetheless less static than the passage on page 2. The changing density of events directly determines the form.

Ritual character

Billone's music tends towards temporal expansion. His shortest works last less than 15 minutes, but many last around half an hour – such as KRAAN KE.AN, AN, ITE KE MI, Mani. Dike and Equilibrio. Cerchio – while compositions such as 1 + 1 = 1 and Om On are 70 and 80 minutes respectively, considerable durations for chamber duos. Their extended duration, their sound profile and their semantic connotations, and indeed their emphatic insistence on single sounds or structural patterns, lend them an inherently ritual character.

Rituals can be described as social actions that constitute reality and which follow a standardised, predictable and therefore repeatable form.Footnote 10 They have a performative character and are elevated above the flow of daily life by their strict sequence and by temporal, spatial or social signification, such as the use of particular clothing, symbols or ceremonial formulas of speech. Rituals have a ‘performative character… they are effective in the sense that they perform what they simultaneously produce’.Footnote 11 They change social reality in that they oblige participants to hold to what is agreed within the ritual. Everyday contemporary examples are the celebration of beginning school, when nursery children become school pupils, or marriages, in which single people transform into spouses. Their real-life character is tightly connected with their symbolic character. In contrast, perhaps, to purely mechanical repetition, rituals are repeatable patterns that are laden with symbolic meaning: ‘Rituals make some kind of statement… That in turn assumes a common, collectively shared symbolic code. Only out of these collective contexts do the conventions of a ritual obtain their validity’.Footnote 12

Even though rituals are still significant in today's society, one nevertheless often thinks first of magic rituals of pre-modern tribal cultures, of solstice celebrations, shamanic cultures or initiation rites. In these, rituals regularly form a close connection to the magical:

By magic, one understands commonly the execution of secret symbolic formulas of speech, gestures and actions, that bring about a particular effect – impossible to prove empirically – in the physical world, or that reveal knowledge of secret things in the past, present and future.Footnote 13

Magic fell into disrepute in later theistic religions – as Moses’ critique of the adoration of the golden calf shows – and continues to be suspect in modern society: the mystical in magic is at odds with the progressive principles of rational enlightenment. From a scientific perspective, magic was dismissed as superstition, while it was criticised on ethical grounds because of its links with issues of power.Footnote 14 In new music, magic exercises as much fascination as it evokes hostility, nowhere more so than in the musical thought of Pierluigi Billone's former composition teacher, Helmut Lachenmann, who regards magic as a basic human desire for experiences that goes beyond discursive rationality.Footnote 15

Pierluigi Billone's music connects with a number of aspects of ritual and magic, regularly displaying structural patterns that can be comprehended as ‘ritualised formulae’ because they follow a strict sequence, are often repeated and appear to have an inherent symbolic meaning. In Billone's often free-flowing music, moments of dogged insistence do regularly occur. For example, the concluding section of Equilibrio. Cerchio consists predominantly of varied and repeated alternations between two distinct sound elements. A forceful simultaneous pizzicato over all four strings, often followed by a quick sequence of impulses behind the bridge, functions as a type of opening that creates space for sustained, low and resonant double stops. In analytical sketches for the composition Billone himself also divides this section of the piece (page 14, line 3 to the end) into different ‘ritual parts’, consisting of ‘7 movements’ altogether. Pizzicato accents and a series of impulses are designated ‘opening sequences’ or ‘middle sequences’, and other sounds are identified as flashbacks. A similar constellation of varied and repeated patterns can also be observed earlier in the piece: on pages 10–12 a series of ‘shrill accents obtained by extreme bow pressure – loud, fully toned double-stops – noisy halting sforzato’ returns over 20 times (see Example 5).

Example 5: Pierluigi Billone, Equilibrio. Cerchio, p. 10, line 4 (2014).

In the final section of Mani. Mono similar patterns emerge. A ‘formula’ (as Billone puts it in his sketches) appears on the last two pages, beginning with a powerful rebounding impact from the springs beneath the drum before a further strike of the upper drum hole, and ending with one or more dead strokes (see Example 6). Between these short actions lies a mostly similar but never consistently and identically modulated sound.

Example 6: Pierluigi Billone, Mani. Mono, p. 8, line 2 (2007).

Consistently characteristic is the beginning and end of the patterns. Their signal-like character marks them as topoi of ritual formulae which Billone cites both as references to Eastern ritual practices and to examples from new music:

Also, if my music is fundamentally about a constant transformation of Klang, there are nevertheless moments of repetition that are unusual and enable a magic phenomenon in which time stays still… Sometimes it has happened quite consciously, that I have imitated the structure of ritual formulas… At the end of Mani. Mono there are a few actions that are more or less clearly suggest a few recognisable Taoist or Tibetan formulas: opening impulses – something happens – end; it is always varied. You also find that in typical form in Stockhausen, in Telemusik or Zeitmaße, or in Rituel by Boulez. All extracts begin with a strike of a traditional Japanese instrument, something happens, and there is a conclusion like in a cadence.Footnote 16

Billone suggests that the impression of a ritual ‘probably occurs because there is a focus that guarantees particular acts a place. In particular, because a few sounds assume a marked role, which distinguishes them from the others, this positions them as actors in a symbolic context’. For Billone, a ritual Klang is not a musical category; rather, it has a symbolic function:

The sounds are signs for something else. The sounds have a religious, magic, symbolic meaning and remain what they are. Sometimes one has this impression, I have it too, although there is no religious context. What sometimes happens, I think, is that the sounds take up positions, in which they accrue a particular importance.Footnote 17

Three times in Mani. Mono a gesture is repeated exactly. Again it is termed a ‘formula’, this time in Billone's performance directions, and involves the voice and body of the performer as a sound generator. The player hums and simultaneously strikes themselves on the chest with their hand (see Example 7). This formula is highlighted not only because of its striking sonority but also through its structural framing, each appearance placed in the middle of a moment of stasis so that the listener is directed to this particular Klang.

Example 7: Pierluigi Billone, Mani. Mono, p. 5, line 3 (‘Formula’) (2007).

The sense of ritual, with its dependence both on insistent repetition and on symbolic meaning, emerges in Billone's music predominantly through the use of particular percussion and vocal sounds. Thus the metal sounds from Mani. Dike, the auratic resonances of the plate bells and the overtone-rich, protracted ringing of the singing bowl impulses, conjure up the aura of ritual or even magic. Billone's use of the voice functions in a similar fashion. A strongly nasal colouring is a central sound type in his music, and one can hardly avoid the association of ritual overtone singing in works such as KRAAN KE.AN. The Sumerian titles of his early works also refer to the realm of the archaic, clouded in mystery, and Billone's use of phonetic sounds similarly awaken ritual associations. The whispering and murmuring, of his singing voices, act like magic incantations, and KE AN. Cerchio for low voice solo (1995, rev. 2003) might be seen as a paradigm of the ritual in Billone's oeuvre (see Examples 8 and 9).

Example 8: Pierluigi Billone, KE AN. Cerchio, p. 5, line 1 (1995/2003).

Example 9: Pierluigi Billone, KE AN. Cerchio, p. 10, line 3.

Yet the impression of a prehistoric language is misleading. While the titles of many earlier pieces consist of Sumerian terms, this does not apply to the sung syllables:

The language, which I used in many other pieces, is an imaginary language as a rule and has nothing to do with Sumerian. It has typical and spontaneous (not clearly recognisable) resonances of ancient Greek, old Italian/Latin as well as a few syllables that belong to many languages (NE, ME, IMA, BU, TU, ELE etc.).Footnote 18

Billone's imaginary language gives the impression of secret symbolic speech formulae, communicative and deeply expressive, but semantically undefined.

Ritual and critical reflection

Billone's music has connotations of ritual without ever reverting to pre-Enlightenment ideas. He invokes the sphere of the magical yet keeps it at bay, avoiding any possibility of meditative immersion or collective ecstasy. Billone's music is consistently atonal and is only meditative, immersive or ecstatic in its focus on central tones; these, however, are made unstable through glissandi and figuration and rarely dominate hierarchically. In particular, the consistently aperiodic rhythmic structures of his music are geared towards a fundamental openness and unpredictability.

There are parallels with Nicolaus A. Huber's principle of ‘conceptual rhythmic composition’. Huber's technique, influenced by Bertolt Brecht's speech-rhythm theory, uses disruption to alienate and aperiodically shape regular and corporeal rhythms, avoiding the ‘anodyne’, ‘oily-smooth’ effect of regular rhythms.Footnote 19 Similar strategies can be observed when Billone's music avoids literal repetition almost without exception, thus eliminating periodically recurrent structures that could lead to trance-like effects. The formulas in the concluding part of Mani. Mono (see above) always follow the same sequence, but their details are highly varied. The first and final sound of the patterns are identical, but the duration and internal organisation is always different. Nor is it ever predictable whether a pattern will end with only one or more dead strokes. The form and structure of Billone's music cannot be anticipated, because its material contains no formal implications; for Mathias Spahlinger, this is a defining characteristic of an emphatically new music.Footnote 20 Mani. Mono begins with a somewhat aimless rhythm of great consistency (see Example 10), its irregular regularity making it seem endless, since there is no sense of how it might develop or end.

Example 10: Pierluigi Billone, beginning of Mani. Mono.

In Om On the continuous undectuplets (11-tuplets) are only occasionally accented regularly, so that no periodic metre arises (see bars 275–80), and in Mani. Gonxha strong beats in a regular pulse, but without metrical subdivision, are interrupted by unpredictable accents and rests. Further strategies of formal openness can be found in the layering of heterogeneous sound-types, as at the beginning of Om On, or the montage of diverse structures. This openness is also propagated by sudden interruptions and pauses, sometimes cutting across the musical flow in a striking way.

Billone's compositional strategies can clearly be connected to an aesthetic stance that might be described as ‘critical composition’,Footnote 21 although the composer has never publicly acknowledged this. A critique of the historical conditions of musical material is more significant for Billone as an obvious precondition of his musical thought and less central to his artistic reflection than in the work of Helmut Lachenmann, Nicolaus A. Huber or Mathias Spahlinger. Yet the avoidance of traditional musical means has a decisively perceptual-psychological cause: familiar topoi tend to be sorted into pre-existing interpretative patterns. Listening is often more concerned with a confirmation of the familiar than objective observation.Footnote 22 The unusual soundworlds of Billone's music and the unregulated experiences that they enable are thus two sides of the same coin. It might also be argued that the moments of magic in Billone's music are only possible because they are so enigmatically ambiguous: magic depends on secrecy. It is the meeting of dissociation and transformation, of concentration and openness, that is a precondition for the restitution of the magical.

Corporeality

Billone's music aims for holism. The composer not only rejects the separation of timbre into individual parametersFootnote 23 but also regards with scepticism the primacy of discursive rationality in so-called Western culture, one possible reason for his silence regarding the technical deployment of his compositional strategies. He equates rational abstraction with a loss of immediacy and a concomitant paucity of nuance:

I think – in my experience – that the processes that are based on direct corporeal experiences are much deeper, more efficient and more direct, than lots of reflections that have to pay the price for maintaining a certain distance. That means everything that is formalised, although that too must exist.Footnote 24

The body of the performer is therefore not a means of producing a musical text but a crucial interface for the aesthetic experience. The body, the hands in particular, guides and models Klang in different ways depending on the piece and set-up. The multiply differentiated, continuously modified bowing in Equilibrio. Cerchio is as much an example of the meaning of the manual as the detailed gradations of forms of movement and intensities with which the performer in Mani. Dike uses both singing bowls as an extension of their hands. It is no coincidence that the titles of all five solo pieces for percussion – as well as a few chamber and ensemble pieces – contain the word ‘mani’, Italian for hand. Billone affords the hand a mode of knowledge that reaches beyond the possibilities of rational cognition. He speaks of the ‘intelligence of the hand’, in which the tactile, haptic and reflexive are bound together:

The hand… (as centre of the body) opens and comes into contact with the conditions of Klang, which no theory could ever capture… At this point ‘thought’ fuses in contact with the objects and loses its own boundaries… while the ‘hand’ creates connections; but western culture generally speaking rejects this perspective. The ‘intelligence of the hand’ denotes this union (as an open question).Footnote 25

With the hand, objects that remain inaccessible to the logos, to rational understanding, can literally be ‘grasped’. The corporeal quality of Billone's music is essential. The music demonstrates a proximity to the aesthetic of the performative that, through its concept of embodiment, ‘emphasises that the bodily being-in-the-world of the human in general is the precondition for the possibility of the body acting and being understood as object, theme, source of symbol formation, material for sign formations, product of cultural inscriptions among others’.Footnote 26 Nor in Billone's music can Klang, structure and corporeality be separated: ‘The body acts as embodied mind’.Footnote 27 The performer creates the different types of Klang with their body, channelling and moulding the sounds’ different energetic intensities, their embodied energy becoming simultaneously the medium of communication with the listeners:

I think that if something can appear and be initiated inside the body it has the best chance to communicate with another body and to be understood. For me as a composer it is only about one body recognising what appears from another body… The body is, therefore, in no way only central because I do it all myself – the contact of body and world is thus a site where a potential comprehension can occur. The creation of objects, which are only the objects of a distanced intellectual consideration, do not interest me, because I come from music. The reason why one becomes a musician or a composer is because at some point one was struck by a musical or just a general rhythmic experience. That means where one has experienced this contact, thereafter one is bound to this possibility. That is what one really celebrates in one's work.Footnote 28

Billone's idea of a corporeal communication connects to the concept of ‘flesh’ in the later philosophy of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, whose epistemology seeks to overcome the body–soul dualism.Footnote 29 For the French philosopher, flesh is not a ‘union or compound of two substances’; rather, it is an independently conceivable fundamental principle joining active and passive sensations to each other: ‘It is the coiling over of the visible upon the seeing body, of the tangible upon the touching body, which is attested in particular when the body sees itself, touches itself seeing and touching the things, such that, simultaneously, as tangible it descends among them’.Footnote 30 From this follows not only the reversibility of the visible and the audible, but also the possibility of communication. People do not encounter one another as monadic individuals; rather, numerous possibilities of interconnection emerge between them because they all participate in the universal ‘flesh’.Footnote 31 Billone also assumes that musical understanding emerges not only in relation to an abstract, ideal system of language but through the direct communication of bodies.

The chances of direct communication beyond the text paradigm, which presupposes access to a system of signs, emerges through the energy that the performer physically creates through and in the music and that could also be described as ‘presence’. Its ‘“magic”… consists… of the particular abilities of the performer, to generate energy in a way, that it circulates tangibly in the room for the onlooker and affects them, yes colours them. This energy is the power that comes from the performer’.Footnote 32

This phenomenon of presence destabilises any body-soul dualism in that it creates the possibility that spiritual states of consciousness can be corporeally articulated and sensed, just as the structure of Billone's music relies on its physical embodiment. It is this reconciliation of Klang and structure, of sensuality and intellect, that lies at the heart of Pierluigi Billone's music.