In January 1982, the American composer Charles Amirkhanian interviewed his close friend and fellow composer Anthony Gnazzo (b. 1936) on the Ode to Gravity program on KPFA in Berkeley, California. The day was a momentous one: Gnazzo was publicly presenting his music to a wide audience while also using the opportunity to announce his retirement from composition. Amirkhanian wryly summed up Gnazzo's career thus:

Gnazzo, like most American composers, is laboring under the delusion that someday he will be discovered, and his painstaking labor invested in over one hundred compositions of electronic music, sound poetry, concrete poetry, and experimental theater will be rewarded with fame and accolades. This never will come to pass, of course, and since he insists on living here on the West Coast, his music is seldom or never played in public. … Good evening, Tony. Welcome to KPFA. I'm sorry about your career.Footnote 1

Gnazzo has since been largely lost in the annals of composers working in the diverse and creatively vibrant Bay Area. Only occasional references to him appear in accounts of the 1960s and 1970s avant-garde, usually obliquely, and in the context of other, more well-known colleagues.Footnote 2 Yet materials at the Other Minds Archive indicate that Gnazzo was an important figure in the avant-garde music scene of the Bay Area and beyond, and a crucial player in the complex network of influences and artists working and collaborating on experimental music during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

In this article I will provide an overview of Gnazzo's career and work, tracing his earliest academic compositions and collaborative efforts through to his late electronic pieces and sound poetry in the Bay Area. His oeuvre exhibits a diverse conflation of avant-garde influences and I will divide his career into three stages. The first encompasses his youthful works, beginning in 1964 while he was living on the East Coast and in Canada. After he took up residence in Oakland in the late 1960s, Gnazzo's second period is marked most notably by early involvement with the San Francisco Tape Music Center. This period extends into the early 1970s and features many pieces of aphoristic electronic sound poetry, as well as comedic, anarchic radio pieces modelled upon John Cage. The music produced in the mid-1970s and early 1980s suggests a third stage of development in Gnazzo's compositional voice as he experimented with conventions of the minimalist tradition. The article concludes by reflecting upon issues raised in investigating Gnazzo and his work. Gnazzo consciously avoids discussions or inquiries about his personal aesthetic or compositional output, prompting questions about how or why one should study music that appears to have been ‘abandoned’ by the artist. Gnazzo and his status as a ‘lost’ composer provide an opportunity to reflect upon broad ethical and moral issues inherent in musicological research on living subjects.

Gnazzo's early period

Gnazzo had an auspicious beginning to his career on the East Coast in the early 1960s when he was hired by the Canadian composer Gustav Ciamaga to work at the University of Toronto Electronic Music Studio, with responsibilities focused primarily upon sound engineering.Footnote 3 It was during this time, between pursuing his music studies at Brandeis University and working at the University of Toronto, that Gnazzo composed his earliest known music. A representative piece from this period is his Music for Two Pianos and Electronic Sounds, composed in 1964. The work suggests a heavy indebtedness to the contemporaneous music of Karlheinz Stockhausen, specifically Kontakte, with its fusion of electronic and instrumental sounds.Footnote 4 Structurally, Gnazzo's Music for Two Pianos and Electronic Sounds draws on Stockhausen's ‘moment-form’, in which time, as Kramer suggests, is made vertical, and the music avoids functional or conventional implications of continuity and developmental form.Footnote 5

Gnazzo's extensive background in sound engineering and electronic music synthesis during his early years as a young composer made him a valuable creative partner. In October 1966, he collaborated with David Tudor at the 69th Regiment Armory in New York as part of the series ‘9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering’. This performance series also involved the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, Robert Rauschenberg and Cage.Footnote 6 Gnazzo was one of four composers involved in the performance of Cage's Variations VII on 15 and 16 October, operating the photocells that triggered the sounds that were routed to 17 loudspeakers.Footnote 7 The photocells were light-sensitive, as the name suggests, with interruptions of light hitting the photocells on the base of a set of antennas triggering changes in the sounds heard by the audience.Footnote 8 Tudor had been interested in performing on the bandoneon throughout the 1960s and wanted to compose a unique piece for this technically demanding instrument; the final product, entitled Bandoneon! (a combine), was presented in the 9 Evenings series.

In the Bandoneon! performance, Tudor included remote controlled robot carts with speakers that wandered around the stage as he played a bandoneon with contact microphones fitted on the bellows. The contact microphones relayed the sound input generated by Tudor playing the bandoneon to an array of frequency modulators and filters, with a device called the ‘Vochrome’ allowing pitch variances to determine where sounds would be situated as well as the intensity of the lighting used in the performance.Footnote 9 Lowell Cross, when recalling the performance, noted that Gnazzo was responsible for controlling one of the carts, as well as helping design and control other engineering tools that had been built.Footnote 10 This collaboration with Tudor may have been the first step toward Gnazzo's eventual move to the West Coast: he composed his own bandoneon piece for Tudor, But Don't Step on My Blue Suede Bandoneon, to a commission for the First Live Electronic Music Festival held in Davis and Oakland, California, in 1967.Footnote 11

Gnazzo's middle period

Gnazzo's connections on the East Coast, and his reputation as a skilled collaborator, composer and sound engineer, must have played a large part in earning him the position of Technical Director of the San Francisco Tape Music Center at Mills College from 1967 to 1969.Footnote 12 The sense of excitement surrounding the Center was palpable, as the January 1968 newsletter for The American Society of University Composers indicates:

The Tape Music Center, now under the direction of Anthony Gnazzo, is being rebuilt, and by mid-spring will have two operating studios connected by a central control room. Classes are offered in electronic music techniques, and the studio is used by twenty composers. Tape center concerts this year include music by Wolfe, Cage, Lucier, Behrman, Mumma, Ashley, and Rzewski. David Tudor, who is a visiting lecturer, performs in the concerts and holds a weekly seminar in live electronic performance.Footnote 13

Even after Pauline Oliveros moved in 1966 to work at the University of California, San Diego, her connection to the Center remained strong, with cross-pollination taking its most conspicuous form in guest artist residencies. The same January 1968 issue of The American Society of University Composers newsletter indicates that Oliveros was supplementing her seminar on electronic music with guest artist performances that drew heavily from artists working at the Tape Music Center at Mills College.Footnote 14

Gnazzo's directorship of the Tape Music Center came to an unhappy end, however, by his high-profile firing in 1969. In a radio discussion from April of that year on KPFA it became apparent that the Tape Music Center's interdisciplinary interests and services to the larger Bay Area community were a growing cause of frustration for the Mills College administration.Footnote 15 Gnazzo emphasised in this interview that the Tape Music Center did not intend to exclude Mills College, feeling that the institution would profit from broader collaboration and engagement with the Bay Area community. Following the firing, Gnazzo became a recording engineer at California State University, Hayward.

Musically speaking this middle period of Gnazzo's career was marked by an interest in sound poetry, chance operations, and elaborately designed avant-garde theatre pieces. Comedy was also a crucial component of Gnazzo's aesthetic. For example, amongst his extensive output of short, aphoristic sound poetry compositions that blend into the electroacoustic genre, Sdrawkcab (1971) stands out as a good example of his interest in both comic explorations of a single idea and drawing listeners into the drama inherent in the human capacity for articulation. As the title suggests, the entire 35-second piece consists of a series of utterances played backwards, with the lilt, cadence, and melodic inflections of Gnazzo's voice offering a brief study of phonetic reversal.

Gnazzo was also active in producing music for KPFA, composing a series of works he referred to as ‘Radio Events’ in the 1970s. One of the most elaborate is An Orchestra is Born, realised in 1972 and a piece that Amirkhanian saw as indebted to Cage's 33 1/3. In that earlier piece, Cage invited listeners to place various recordings on a dozen phonographs on tables in a room with loudspeakers dispersed throughout the space.Footnote 16 In the case of An Orchestra is Born, Gnazzo invited KPFA listeners to submit brief recordings of various sounds, which he then subjected to chance operations to create a sprawling, 17-minute radio work of musical superabundance.Footnote 17

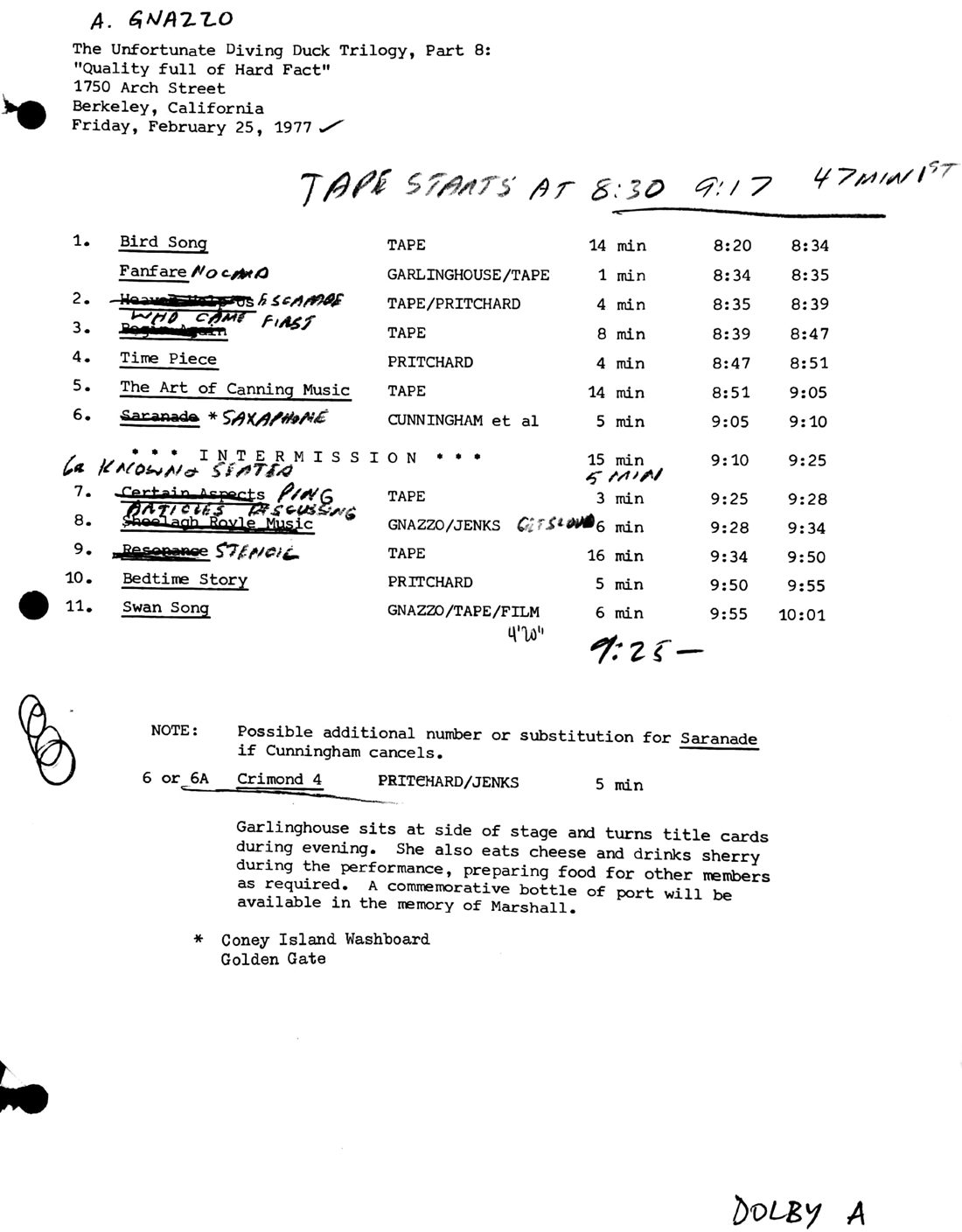

Gnazzo also created live avant-garde theatre experiences throughout the 1970s, the most important being his Unfortunate Diving Duck Trilogy. These evening-length theatrical-concert pieces consisted of multiple, discrete musical numbers, often not composed only by Gnazzo: he favoured stringing together other composers’ work in a collaborative show.Footnote 18 In a performance on 6 February 1977 at Western Front in Vancouver, for example, Gnazzo included his own music alongside compositions by fellow Bay Area composers John Adams and Alden Jenks. On 25 February 1977, The Unfortunate Diving Duck Trilogy (Part VIII) was performed at 1750 Arch Street in Berkeley and featured an array of pieces, both live-performance and tape-based (see Figure 1). As Gnazzo's notes indicate, he strictly worked out how long each piece would last and took care to balance live and tape pieces over the course of the evening.

Figure 1: Box 14, Reel 4: The Unfortunate Diving Duck Trilogy, Part 8: ‘Quality Full of Hard Fact’ 2/25/77, 1750 Arch Tape Collection, ARCHIVES 1750 ARCH, The Music Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Gnazzo's late period

The final years of Gnazzo's creative output in the 1970s and into the early 1980s suggest an interest in exploring minimalist musical conventions. He had been experimenting with drone-based minimalism as early as 1974 with a piece entitled Music for B.A.S.E., written for the Bay Area Synthesizer Ensemble and performed in February of that year. The work was quite an engineering task. It was performed at three different locations in the Bay Area: UC Berkeley, the San Francisco Conservatory and San Francisco State University, with the music Gnazzo composed for each location transmitted by telephone lines to the KPFA radio station, mixed in the studio, and then broadcast to listeners.Footnote 19

Gnazzo's minimalist affinities also included explorations of phasing and the unique rhythmic and melodic possibilities that could arise from the de-synchronisation of multiple tracks of recorded material, suggesting an interest in branching off from Steve Reich's earlier phasing technique. In the 1978 tape piece Asparagus (Everybody Likes It) Gnazzo takes a single drum track and slowly moves it out of sequence with itself, creating a bizarre tapestry of conflicting and complex rhythmic emphases based on a single riff. His subsequent tape piece, Pun Crock (1978), uses the same drum riff but includes melody, with multiple saxophone tracks subjected to the same staggering of entrances and de-synchronisation found in Asparagus. These pieces appear more jocular and humorous than serious, which is a general trend that seems to accompany Gnazzo's realisation that he would never achieve widespread recognition for his work. There is some suggestion that Gnazzo was at least ambivalent, perhaps even bitter, about both minimalism and his own compositional prospects in the early 1980s: one of his last pieces, a work composed in 1982, was entitled Omaggio ai Nuovi Fascisti Tonale (Homage to the New Tonal Fascists). Interestingly, Gnazzo explained in a 1983 interview that the music for this piece was serving as the basis for an ongoing orchestral project and a ‘two-day opera’ he was developing that was based on a ‘famous Italian hero’.Footnote 20

Although Gnazzo announced his retirement from composing in 1982, there is evidence that he continued to work occasionally and that his music circulated. Most notably, he composed a short piece in 1987 for an exhibition at the Wight Art Gallery at the University of California, Los Angeles, featuring prints that Jasper Johns made for Samuel Beckett's book Fizzles. Gnazzo's contribution was a piece, for which he also performed a mime role, based on Beckett's short story Ping.Footnote 21 At least one Gnazzo work from the 1970s ended up having far more influence than he thought: Asparagus (Everybody Likes It) was sampled by DJ Shadow in his single ‘Giving Up the Ghost’ from his 2002 album The Private Press. The phasing effect Gnazzo explores in the original is lost in the sampling performed by DJ Shadow, but this bizarre occurrence speaks well to the curious and strange routes through which Gnazzo's music has travelled.Footnote 22

Historiography, musicology and manipulation

Gnazzo seems to have had all the ingredients necessary for success as a composer: he knew important people, collaborated with them frequently, and had a stable method for disseminating his music via the KPFA radio station. Reviews from the 1970s further attest to his status as a cultural fixture in the Bay Area avant-garde. As Jan Pusina explained in March 1975 when reviewing his concert entitled ‘Peanut Butter and Marshmallow Pizza’:

New arts lovers of the Bay Area should consider themselves fortunate in having Tony Gnazzo as an active resident composer. He works with great technical polish, is possessed of perceptive and cutting social insight, and has a deep awareness of the state of contemporary arts.Footnote 23

There can be no definitive explanation as to why Gnazzo fell through the cracks of history. Perhaps he struggled to shed the label of ‘sound technician’ after his brief tenure at the San Francisco Tape Music Center ended in 1969. It is also possible that Gnazzo's devotion to concrete poetry led to his obscurity, as this genre, to which he contributed so much, was consistently at the margins. Indeed, in 1978, Richard Kostelanetz lamented the marginalised status of concrete poetry due to its lack of printed transmission in anthologies or recordings.Footnote 24 Although Kostelanetz was a strong advocate and published several anthologies, he acknowledged how hard it was to disseminate, mentioning Gnazzo specifically as one such composer who was tired of making copies for people.Footnote 25 Lastly, it is possible that Gnazzo's other music, whether Cagean-style radio pieces, experimental theatre-concert events, or somewhat derivative phasing pieces like Asparagus and Pun Crock, simply did not age well.

The most obvious value gained from recovering a lost and forgotten composer such as Gnazzo is the light he sheds onto Bay Area avant-garde musical culture during a fascinating period of creative activity. His close relationships with a diverse population of composers, as well as his wide-ranging skills as a sound poet, composer, and engineer, further clarify and corroborate the richness of the collaborative environment that characterised the region during the 1960s and 1970s. More broadly, Gnazzo's reclusiveness and unwillingness to discuss his music raises moral and ethical issues about what one should do when the subject of musicological research is a living composer and unwilling to be a subject. Janet Malcolm has tackled such moral and ethical issues of the researcher–subject dynamic in her book The Journalist and the Murderer:

Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible. He is a kind of confidence man, preying on people's vanity, ignorance or loneliness, gaining their trust and betraying them without remorse. Like the credulous widow who wakes up one day to find the charming young man and all her savings gone, so the consenting subject of a piece of nonfiction learns – when the article or book appears – his hard lesson. Journalists justify their treachery in various ways according to their temperaments. The more pompous talk about freedom of speech and ‘the public's right to know’; the least talented talk about Art; the seemliest murmur about earning a living.Footnote 26

Matters of betrayal and deceit, as well as acting in good and bad faith as a researcher, are significant issues for a musicologist examining composers who are still alive. We might, for example, work closely with composers’ material and end up arguing for insights contrary to their wishes. Our investigations could bring things to light composers would rather have forgotten. Jeremy Grimshaw has grappled intensely with problems of the researcher–subject relationship while writing his dissertation and eventual monograph on La Monte Young. The finished book, Draw a Straight Line and Follow It (2011), received heavy criticism from Young, along with demands for the book to be ‘corrected’. Grimshaw, in his introduction, referred to the heady environment and shifting methodological frames he juggled over the course of his time at Young's studio and apartment in New York as being akin to ‘gonzo musicology’. As Grimshaw makes clear, the musicologist–subject relationship was challenging:

I had to answer to Young himself – often on the telephone, late at night, according to his esoteric waking/sleeping schedule – for everything I said about him. This became a delicate dance, particularly given the dual challenges of Young's powerful self-image and his complete control over virtually all the materials related to his compositions. Eventually our relationship became strained, to the point where Young, in exchange for permission to use score excerpts, correspondence, and photographs, demanded high financial remuneration and a problematic degree of editorial influence upon the manuscript. He also made a list of a corrections, which he said he would give to me only if I met his other demands.Footnote 27

Young's August 2011 letter to Oxford University Press editor Suzanne Ryan and his public statements regarding the controversy are telling. He often uses the language of someone who feels betrayed, incredulous that a researcher could take advantage of a host who had so graciously allowed someone into his life to study his music:

I was very shocked by this refusal to accept my offer to help make the many corrections that could only be made by Marian and me. We had treated Jeremy as though he could potentially write an in-depth scholarly document about our work, letting him stay in the 4th floor Archives at Church Street to have direct access to letters and other documents to carry on his research. From the very inception of the project we had functioned in sincere cooperation with Jeremy, correcting the early drafts as he sent them to us and supplying additional information. As I wrote in the Statement that Oxford declined to publish: ‘Being the idealist that I am, I had imagined a process whereby we would slowly work with Jeremy and carefully try to delineate the facts about my life and my work. Since the project began with much promise and mutual enthusiasm, I certainly never imagined that I would be writing this statement of disagreement with his book at this point in time’.Footnote 28

Terry Riley entered the fray as well, suggesting that, more than betrayal, Grimshaw was committing acts of intellectual dishonesty with his scholarship:

I feel that Mr. Grimshaw fails to recognize some of the very important associations and key elements contributing to La Monte Young's evolution. I was quite stunned to find how little mention was made of the 26-year long relationship that La Monte had with his Guru, Pandit Pran Nath. This could have easily occupied one half of the volume alone. Since Jeremy had very privileged access to La Monte's archive there is no reason for this omission. It seems he simply turned his back on these epic chapters of their long and intimate association. This greatly deprives any reader of this book knowledge of the great importance a central character like Pandit Pran Nath played in Young's life and the great stories that were there to be told. The extended and central role my life and work have played in this long association with Young were also barely mentioned. It would be like writing a book on Debussy and not mentioning Ravel!Footnote 29

Aside from the self-flattery of equating himself to Maurice Ravel, Riley, although not a journalist, invokes ‘the public's right to know’ as justification for postponing the publication of Grimshaw's book.

During the initial forays into finding a way to contact my subject, I was told that it would be best to ingratiate myself with him by discussing his favourite Italian TV show, the crime series Inspector Montalbano, and to avoid direct discussions of his work. Dutifully following these instructions, my eventual email inquiry to Gnazzo did include references to Montalbano while also mentioning my genuine fascination with Italian writers of crime and mystery novels. In truth I have watched little of Montalbano and am generally not interested in crime thriller TV shows. I did not want to act in bad faith, so I opted for some truth mixed with untruth, trying to strike the right balance, which is the moral conundrum that Malcolm finds at the heart of research: when do we tell the truth, bend the truth, or conceal the truth if it runs the risk of making subjects close themselves off and prevent the investigation from progressing? Morally, research on living composers will always grapple with these issues to varying degrees, and some living composers might be wise to the friction that can result from the researcher–subject dynamic.