Shortly after the 2018 midterm elections, Republican and Democratic governors held meetings of the Republican and Democratic Governors Associations (RGA and DGA) in Scottsdale, Arizona, and New Orleans, Louisiana, respectively, at which they elected new leadership, hired new staff, and touted their electoral and policy accomplishments.Footnote 1

National partisan politics took center stage despite the meetings consisting of state-level officials. GOP governors discussed the party's losses in congressional and state-level midterm races. Larry Hogan (R-MD) and Charlie Baker (R-MA) echoed the recommendations made in the 2012 Republican National Convention (RNC) “autopsy” report, touting their support among suburban voters and women, groups that have been trending away from the GOP during the Trump era.Footnote 2 Democratic governors distinguished themselves from President Trump and congressional Republicans on healthcare policy and the diversity of their political coalition, noting the record number of women elected in 2018.

Today's governors weigh in on national partisan politics often, even on issues that do not immediately concern state politics. Republicans Hogan, Baker, and Phil Scott (VT), for instance, have recently made headlines for declaring that Trump's nominee for the Supreme Court, Amy Coney Barrett, should not be pushed through before the election. The trio of moderates also have stated that they did not plan to vote for the president in his reelection bid.

The RGA and the DGA provide a venue for governors to weigh in on national partisan politics, in particular the image of the national parties. Moreover, today's RGA and DGA are robust organizations, raising and spending hundreds of millions of dollars to support gubernatorial candidates.Footnote 3 Both associations have full-time, professional staffs and headquarters in Washington, reflecting party organizational strength, as measured by Cotter et al. in their classic analyses of party organizations.Footnote 4

The existence of national partisan gubernatorial organizations raises a set of important developmental questions concerning the nature of the American party system. Why did governors form national organizations within the parties rather than operate through the traditional decentralized state party infrastructure? Why did these organizations form when they did? And what effects have these organizations had on the party system?

The formation of these organizations is curious given the decentralized design of the American constitutional and party systems. Federalism allows for autonomy in state-level executive office and distinctive state political cultures and electorates. The party system envisioned by Martin Van Buren privileged local and state organizations, keeping the national parties accountable to an array of patronage-based groups.Footnote 5 Moreover, the RGA and the DGC (Democratic Governors’ Caucus, precursor to the DGA) were created before the demise of the “mixed” system of presidential selection, the adoption national campaign finance regulation, and the passage of the Voting Rights Act, moments that were pivotal in the nationalization of the American party system.Footnote 6

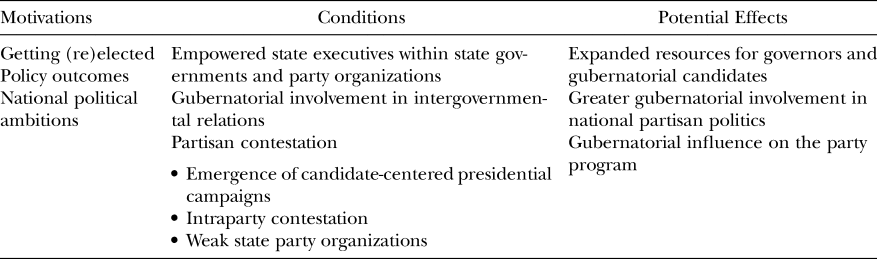

This article explores the origins and early activities of the RGA and the DGC from 1961 to 1968.Footnote 7 I argue that governors, especially GOP governors, created these organizations as a means of asserting themselves within an evolving party system. Governors built these organizations on their increasingly strong positions within state politics, including state party politics, and active participation in intergovernmental affairs. They recognized, however, that ongoing changes to the relationship between the national and state parties threatened their standing within the national party infrastructure. The rise of a new class of party activists, changes in the conduct of national convention politics, and the expansion of the national administrative state threatened the governors’ place within the traditional party infrastructure. The governors created these organizations as a means of adapting to these changes. In doing so, the governors contributed to the rise of a national party-in-service; asserted themselves as leaders within the national parties, ones who could contribute to national party programs; and promoted coordination among themselves and with national party elites in developing strategies and messaging (see Table 1).Footnote 8 Governors were not just relevant within traditional state party organizations or the geographic confines of their state. They demanded recognition of their importance in policymaking and rhetorical leadership, factors that increasingly mattered in a nationalizing party system. The RGA and DGC became a means of demonstrating this importance.

Table 1. Motivations for, Causes of, and Potential Effects of Partisan Governors’ Associations

Governors found themselves as key figures in what Shafer and Wagner call the “long war over party structure.”Footnote 9 The governors discussed here must be understood not as agents of traditional state parties but as leaders whose ambitions often reached well beyond state boundaries. Governors found themselves amid a transition from a decentralized to a more nationalized party system, one that was crystallized after the reform era but had roots going back decades. Governors formed these organizations because of the increasing interconnectedness of state politics, intergovernmental policy, and national party politics, a trend that became particularly vivid with the reemergence of civil rights as a major issue on the national stage. Put simply, the governors found existing party rules and procedures inadequate to advance their agendas, and they adapted to remedy this lack of standing within the national parties. During this era, governors, seeking to improve the images of the national parties, turned their attention to party organization in innovative, even entrepreneurial ways.Footnote 10

The first half of the article explains RGA and DGC's origins. First, I overview the place of governors in the polity leading into the 1960s, emphasizing changes to governors’ roles within state politics, intergovernmental relations, and the national parties. Changes to policy and party programs, especially concerning civil rights, provided uncertainty in terms of electoral prospects and governance, prompting governors to engage in partisan politics in new ways.

Not all governors were affected equally by these developments. Governors were split on civil rights both within and between the parties. However, the difference in the effects that the nationalization of civil rights had between the parties’ governors was stark. Most GOP governors at the time were moderate, including Nelson Rockefeller (NY), George Romney (MI), and William Scranton (PA). The rift among Democratic governors was deep, reflecting the breadth of the New Deal coalition. In the early 1960s, Democrats held most governorships, but this majority included a sizable contingent of Southern conservatives, including George Wallace (AL), who were still operating in a largely one-party region. In short, the incentive structure present for GOP governors promoted coordination, but this was not true for Democrats.

The second half of the article explores the implications of RGA and DGC for the party system through 1968. These organizations expanded the national party-in-service, integrated the governors into an evolving party-as-organization, and allowed their members to exert influence over the national party program, particularly as it related to federalism. Again, differences manifested between the parties. That is, civil rights motivated governors to adapt to changes in the national political landscape but the degree of adaptation was much more pronounced within the GOP than the Democratic party. Republicans developed a robust and active RGA, while the DGC was weak and unorganized. Additionally, while GOP governors advocated for a form of New Federalism, Democrats relied on the logic of dual federalism.

To be sure, the story of these organizations is not one of unmitigated success by the key players discussed here. The GOP did not, for instance, become the party of Rockefeller. Southern Democratic governors did not prevent the national party's leftward drift. However, GOP governors did, in coordination with RNC Chairman Ray Bliss, expand the party-in-service and allied with then-candidate Richard Nixon to promote what became New Federalism as part of the 1968 platform. The governors began to engage in national politics in new and meaningful ways, even as many within these caucuses remained at odds with others in their parties regarding electoral strategies and policy positions.

In making these arguments, I draw upon an array of evidence, including original archival materials found in the papers of several governors and national party chairmen. I supplement these materials with newspaper coverage of these events, transcripts of National Governors’ Conference (NGC) meetings, Republican and Democratic National Conventions, and other party meetings, and findings from secondary literature.

What is novel here is that governors are contributing to national party-building efforts on their own terms. Beyond focusing on two organizations that have received scant attention by American political development (APD) scholars and historians, and thus contributing to the historical record, I seek to highlight the uniqueness of the American governorship at midcentury, the rules and procedures structuring gubernatorial behavior, and the entrepreneurial activity within the party system by these actors. Thus, this article seeks to deepen our understanding of the motivations of an important subset of elected officials within a federated party system and provide nuance to our understanding of party nationalization and, relatedly, the differences in patterns of development between the parties during this period.

Governors drove these changes based on their unique place within the parties. One school of thought posits that parties can be thought of as coalitions “of policy-demanding groups” that develop agendas “of mutually acceptable policies,” insist “on the nomination of candidates with a demonstrated commitment to [their] program[s], and work to elect these candidates to office.”Footnote 11 While this view emphasizes the representative nature of parties, it does little to explain the entrepreneurial role governors played in the development of party organizations. The organizations developed were based on the interests of elected officials and candidates rather than interest groups or party factions specifically.Footnote 12

Another school of thought posits that parties are “endogenous institutions” that “can only be understood in relation to the polity, to the government and its institutions, and to the historical context of the times.”Footnote 13 I hold that the transformation of the party system discussed here is rooted in the motivations of “office seekers.” Put simply, the governors’ attention to national party organizations was rooted in their electoral and policy goals as well as their evolving place within the American constitutional and party system.Footnote 14

Additionally, the emphasis on the actions of governors forces us to grapple with how scholars of APD understand party nationalization. William Lunch notes, for instance, that “to a much greater extent significant choices in American society are made directly by the national government, or at least with the approval of the national government.” Additionally, “the crass, but reliable, materialism that was the foundation of the old system is being rendered increasingly obsolete by a politics frequently dominated by abstract ideas that have mobilized a new class of political activists on both the left and right.”Footnote 15 This understanding of nationalization underscore a shift in power from the state to the national level.

Huckshorn and colleagues, however, note that “integration involves a two-way pattern of interaction between the national and state party organizations. Integration implies interdependence in the sense that neither level of party is necessarily subordinate to the other. Thus, conceptually, integration must be measured both in terms of state party involvement in national party affairs and national party involvement in state party affairs.”Footnote 16 I hold that the activities of the governors discussed below underscore the interplay between state and national party officials. State-level officials have played important roles in shaping the national parties in tandem or tension with presidents, presidential candidates, national party chairmen, congressional leadership, and issue activists.Footnote 17

Finally, this article contributes to our understanding of the development of the party-as-organization in terms of the motivations for the developments that took place as well as differences that emerged between the parties.Footnote 18 Heersink notes that while much early political science literature treated national party organizations as “bystanders in the American political system,” politicians have invested significantly in these organizations.Footnote 19 Galvin observes that political institutions, including party organizations, provide stability and constraint on political actors but also “mobilize people, enter into political dialogues, compete for power, participate in decision-making processes, and attempt to influence political outcomes. They strategically seek to reshape the broader political environment in which they operate.”Footnote 20

Governors were involved in this turn toward party organization. They had incentives to seek new forms of influence within the national parties as they became increasingly empowered at the state level and more intimately involved with the national government but found their influence waning within the traditional party apparatus. Governors should not, therefore, be thought of as agents of traditional or what Shafer and Wagner label “organized” state parties, which are based on material incentives and control of nominations by party officials.Footnote 21 They may have been responding to the rise of amateur or voluntarist elements within the party, but their activities did not rely solely on traditional Jacksonian means. Rather, their actions reflected a recognition that changes to party organizations and functions, including presidential nominations, were required to advance their goals.

Further, the paths of development taken by these organizations were “asymmetric,” and this asymmetry is rooted in the degree of unity within the organizations’ memberships at the time.Footnote 22 The Republicans led the way in terms of party organizational transformation, building a national party-in-service and adapting to a loss of influence of state party organizations within national convention politics. Democrats, reflecting deep divisions over civil rights, relied on traditional means of influence, especially within the context of national nominating conventions.

For purposes of space, I end this analysis in 1968. However, the impact of these organizations is still being felt today. The RGA and today's DGA are two of the most important 527 organizations; the parties have come to rely on states to further national governing agendas and continually pledge commitments to federalism in their platforms, if on strategic rather than principled grounds; and governors have used the organizations to advance their own agendas, both policy and electoral.Footnote 23 In sum, actions taken by the likes of Robert Smylie (R-ID), Rockefeller, and John Connally (D-TX) during the 1960s provided a foundation on which future generations of governors have built.

1. Why National Partisan Governors’ Caucuses?

In the early 1960s, governors found themselves in a precarious position due to changes in intergovernmental relations and national party politics. This precariousness precipitated these individuals to consider altering party structure. The RGA and the DGC were the creatures of governors. Thus, in order to explain RGA and DGC's origins, one must comprehend three sets of factors: the motivations of those who created these groups, the governors’ place within the political system, and the historical setting during which these organizations appeared. I discuss each of these sets of factors in turn.

1.1. Gubernatorial Motivations and Roles

Governors and gubernatorial candidates share the goals of members of Congress (MCs)—getting (re)elected, achieving policy victories, and sometimes seeking national office.Footnote 24 Parties help these ambitious governors fulfill these goals. In elections, for instance, “affiliation with a party provides a candidate with, among other things, a ‘brand name,’” which “convey[s] a great deal of information cheaply” to voters.Footnote 25 Parties, in short, are perhaps the most important venues through which office seekers channel their political ambitions.Footnote 26

Governors’ places within the national parties are unique. Their relative autonomy is constructed through the nature of candidate-centered campaigns and constitutional design—the separation of powers and federalism. For one, they are not subject to the same pressures as MCs from legislative party leadership and many governors espouse appreciation for the autonomy inherent in being governor. Former Governor and Senator Charles Robb (VA), the first chair of the modern DGA, once noted that “I'm not a legislator at heart, I loved being governor.”Footnote 27 Additionally, “Because state politicians can build a career with only a fraction of the nation's constituents—and only rarely a representative fraction—they have strong incentives to diverge from their own national party leaders and platforms when it serves their political purposes.”Footnote 28 In short, gubernatorial independence is valued and asserted in terms of partisan politics. Many governors, including Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, for instance, were instrumental in attacking traditional party organizations beginning in the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era.

1.2. The Deep Historical Roots of National Gubernatorial Activism: Emboldened State Executives, Cooperative Federalism, and a Nationalizing Party System

By the early 1960s, governors found that the traditional party system was no longer adequate for them to advance their goals. On this front, three developments, taken together, were critical—augmented importance within state politics, increased presence within intergovernmental relations, and diminished status within the national party-as-organization.

First, governors were generally becoming more powerful within state politics, including party politics, a trend which, onto itself, should have empowered the governors within the traditional decentralized party system. Governors emerged as the leaders of state parties rather than creatures of them. Students of the American governorship often look at the early twentieth century as a period of weak chief executives, a pattern rooted in an American political tradition that viewed executive power with a deep-seated suspicion.Footnote 29 Yet, beginning in the late nineteenth century reformers promoted executive leadership at all levels of government to correct for the ills of the Gilded Age—requiring rational, systematic, and coordinated public policy as well as a robust vision of rhetorical leadership. For instance, the governors’ ability to veto legislation became nearly universal by 1960. By 1950, only ten of the then forty-eight states did not grant governors budget-making authority.Footnote 30 Gubernatorial staffs and their levels of professionalization increased during the 1950s.Footnote 31Additionally, as noted in the Council of State Governments’ 1959 Book of the States, there was a heightened “extent to which Governors have taken the initiative in proposing administrate reorganization.”Footnote 32

The enhancement of formal gubernatorial powers was coupled with a liberation of the governor from state party organizations. By 1960, gubernatorial primaries were used in almost every state and patronage, while far from extinct, had fallen significantly from its heyday in the nineteenth century. The decline of patronage, Sabato notes, was “a boon for governors, since it has liberated them from a tedious, time-consuming, and frustrating chore that is outmoded in the modern political system. At the same time the governor has gained appointive powers where it really matters, at the top-level in policy-making positions.”Footnote 33 These trends promoted gubernatorial name recognition among the electorate. Hopkins notes that during the 1950s and 1960s, over 80 percent of Americans could identify their governor, which was 20 percentage points higher than in the mid-2000s.Footnote 34 Fewer governors, particularly outside of the South, found themselves in truly “organized” parties at the state level in the Jacksonian sense. Rather, governors were increasingly active in policy formation.

Second, governors had become consistently involved in intergovernmental politics. This began during the Progressive Era and was extended during and after the Great Depression.Footnote 35 Cooperative federalism tightened the relationship between the national and state governments. States became avenues for the national government to achieve public policy goals. State governments also needed federal financial resources, which became much more significant during and after the New Deal, a trend that was sustained across Democratic and Republican administrations. Robertson, summarizing data from the U.S. Office of Management and Budget, notes that the share of federal outlays, in the form of grants to state and local governments, increased from under 2 percent in 1945 to approximately 7 percent in 1960.Footnote 36 Ultimately, states became involved in the joint financing and/or implementation of such programs as unemployment, welfare, Social Security, and disability insurance.Footnote 37 Governors, as the heads of the executive branch and therefore the administrations in the states, had ample reason to engage in discussions over intergovernmental policy.

Governors also had institutionalized, though formally non- or bipartisan, venues for engaging with national political elites. Perhaps most significantly, the NGC, founded in 1908 at the behest of President and former New York governor Theodore Roosevelt to deal with conservation efforts, brought governors together with members of the national administration and congressional leadership.Footnote 38 These interactions became routine in part thanks to the regularity of these meetings, first annually and then twice a year. Ultimately, NGC meetings provided the governors with three audiences: each other, national political elites, and the public.

Governors also became active in a series of congressional and presidential commissions created to grapple with intergovernmental issues.Footnote 39 Like the NGC, these groups were formally bipartisan. In 1953, for instance, Congress created the Commission on Intergovernmental Relations. In a retrospective on the commission, member William Anderson wrote, “The two major parties secured a fairly proportionate distribution of strength, but this did not mean that questions were decided upon party lines. Indeed, except for a small amount of off-the-record and lunch-time ribbing there was little or no mention of partisanship.”Footnote 40

Yet, seeds for future partisan bickering were planted. Eisenhower, as McDowell notes, “believed that the federal government had been expanding into too many functions of government that belonged to the state and local governments.”Footnote 41 In fact, Eisenhower's call for the commission was at the suggestion of conservative stalwart and former rival Robert Taft. Additionally, controversy arose over the first chair of the commission, Dr. Clarence E. Manion, who came under fire from liberal groups, including Americans for Democratic Action, after a series of television appearances during which he noted his belief that the federal government had become too powerful.Footnote 42 Manion was replaced by Meyer Kestnbaum, who largely advocated for a more moderate approach to intergovernmental relations than Manion.Footnote 43 Thus, competing visions of intergovernmental relations were present even as formal membership in these organizations remained bipartisan and largely congenial.

Third, by the 1960s governors found themselves in a precarious position in terms of national party organizations, especially national conventions where traditional means of state parties to affect national party decision making were on the wane.Footnote 44

Changes to the party system here reflected the rise of more nationalized and programmatic parties, ones in which issue activists and candidates could play increasingly important roles in the formation of party images. One line of scholarship has emphasized a “decline” in American political parties rooted in the rise of candidate-centered campaigns, an emerging breed of partisan activists, and the weakening of the traditional party-as-organization.Footnote 45 As Milkis has demonstrated, “the New Deal's institutional legacy made political accountability newly problematic in the United States. Administrative aggrandizement came at the expense of the more decentralizing institutions of constitutional government, such as Congress and local governments, which political parties had organized into effective representative bodies.”Footnote 46

These changes had important ramifications for the governors’ standing in the national parties. One manifestation of this change concerned the rise of candidate-centered elections at the presidential level and the roles of state-level politicians within the nomination process. As Shafer notes, in the mid-twentieth century, the national convention was transforming from “an institutional mechanism to institutional arena.”Footnote 47 The traditional use of the convention, arriving at a consensus over the presidential nominee, gave way to an emphasis on providing a means of articulating a coherent party message. Televising the conventions and broader changes to the presidential selection process altered the roles of party elites within nomination contests.

The implementation of primary elections in presidential contests curbed the extent to which governors could control delegates from their states. The binding of delegates in primary contests circumvented the influence of governors even as they became the de facto heads of state parties. The use of outsider strategies allowed presidential candidates to make the case that they had developed attachments to voters that went beyond traditional partisanship—that which developed through connections between voters and state and local party organizations. Presidential primaries, hence, undercut the abilities of governors to act as “insiders” within national conventions.Footnote 48 While governors could endorse candidates and lend support to their campaigns, they could not always directly control state delegations to national conventions.

Thus, while gubernatorial authority at the state level and their involvement in national politics was on the rise, governors simultaneously found themselves in an evolving party system with elections becoming increasingly candidate-centered, enhancing gubernatorial autonomy within the states but not in the national parties. These trends allowed for tensions to arise between governors and members of the national parties.

1.3. Race Relations, Governors, and the Parties: Moderate and Relatively Unified Republicans, Divided Democrats

Civil rights politics in the early 1960s made these the tensions vivid, exacerbating differences between and among state and national party programs, including the positions taken by governors, and demonstrating an expanded role in the national state determining policy that had for decades been left to the states. Civil rights also threatened the electoral coalitions that governors had put together within their states. Republican governors at the time were, by and large, relatively moderate on the issue, while Democratic governors had much more disparate views. Thus, increased national attention to and action on the issue promoted governors within both parties to act, but Republicans moved first, more forcefully, and more innovatively, even as both parties remained divided on the issue.

The reemergence of civil rights on the national stage was rooted in longstanding migration patterns and increasing social movement activism, which had differential effects among the states.Footnote 49 Presidential actions and judicial decisions contributed to civil rights being thrust into the national spotlight. President Franklin Roosevelt, for instance, created a new civil rights unit in the Justice Department and issued Executive Order 8802, establishing the Fair Employment Practice Committee. President Truman, in signing Executive Order 9981, set the stage for the desegregation of the armed forces. The Brown v. Board of Education decision opened the door to federal enforcement of national standards within the states, and President Eisenhower ultimately enforced the decision and signed the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960. All these actions implicated state politics and policies.

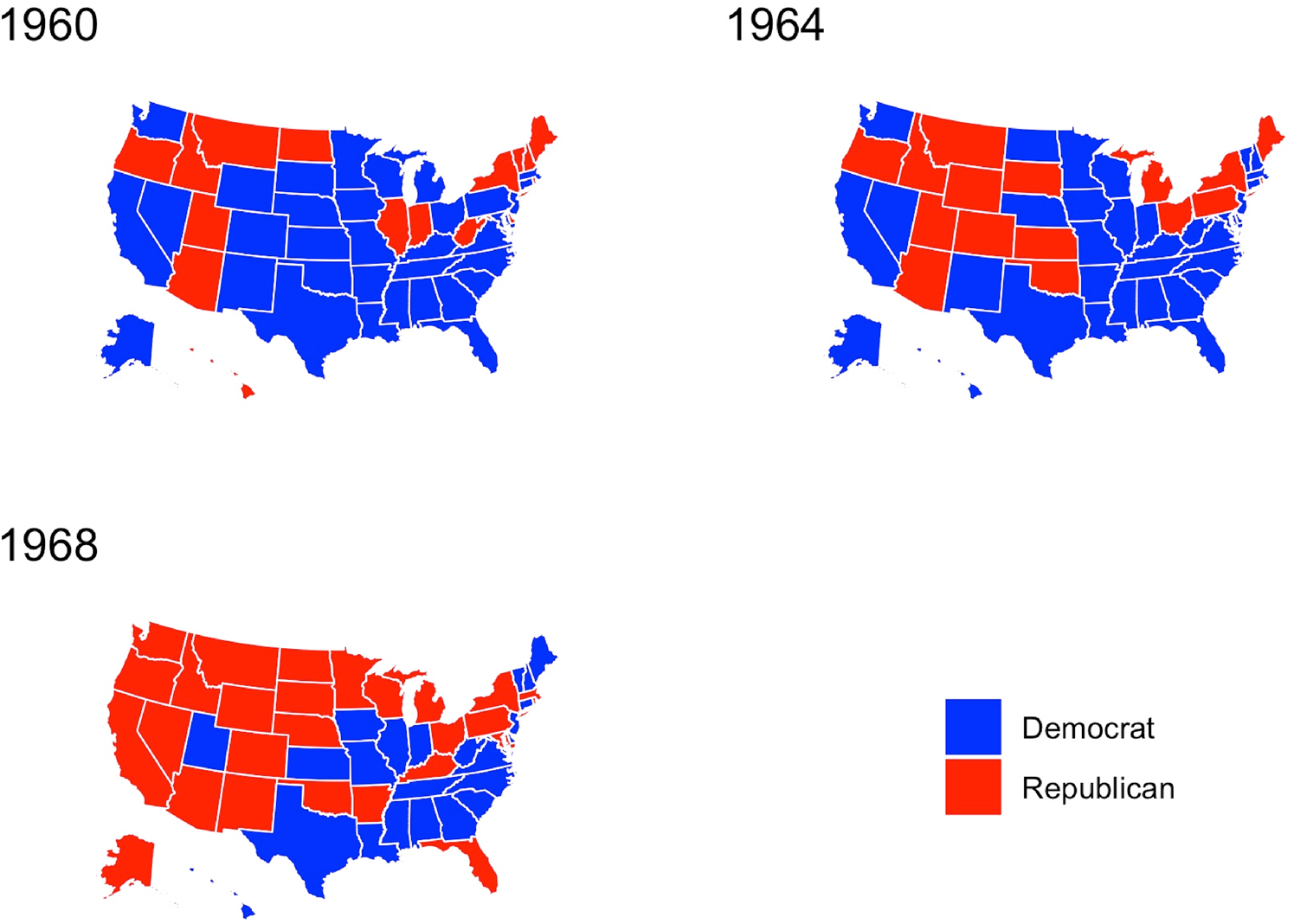

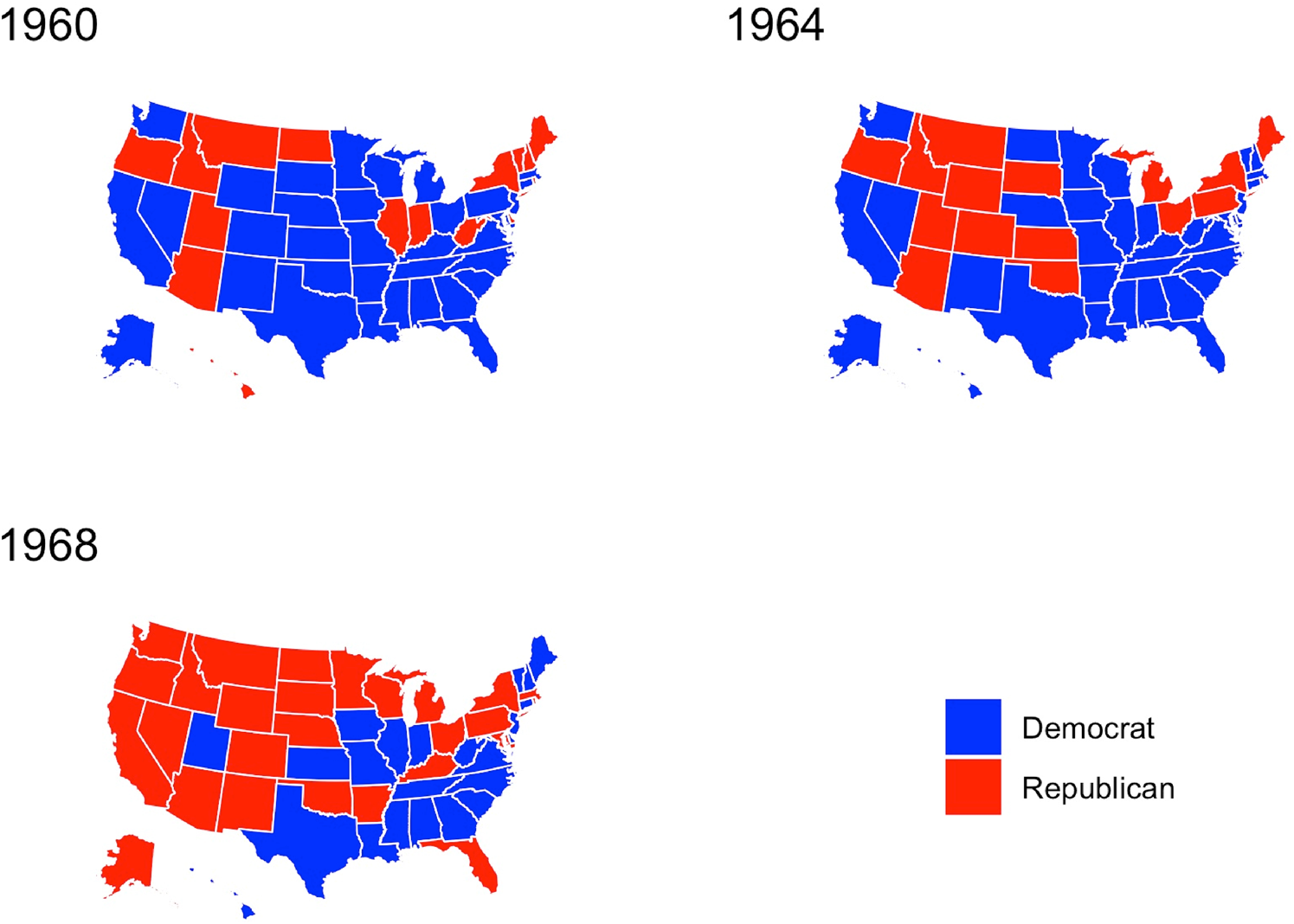

Leading into the 1960s, both parties were split over civil rights, but this divide manifested differently between the parties’ governors.Footnote 50 Republican governors tended to be moderates from outside the South.Footnote 51 In fact, Republicans won their first Southern gubernatorial seat in over forty years in 1966 when Winthrop Rockefeller (R-AR) captured 54 percent of the vote.Footnote 52 Further, the ranks of the GOP governors reflected the party's status as the national minority party.Footnote 53 GOP governors numbered only sixteen after the 1960 elections (see Tables 2 and 3 and Figure 1). Moreover, several ambitious and high-profile governors at the time have been identified with the Modern Republican faction of the GOP, which, as DiSalvo notes, “were primarily a pragmatic and strategic faction that did not seek to fully revamp the party intellectually, but rather only to smooth its rough edges.”Footnote 54

Fig. 1. Governors by Party, 1960–1968.

Table 2. Party Control of Statehouses, 1960–1968

Source: Jerrold Rusk, A Statistical History of the American Electorate (Washington DC: CQ Press, 2001), tbl. 7.5, p. 447.

Table 3. Democratic Percentage of the Two-Party Vote in Gubernatorial Elections by Region by Two-Year Election Cycle (South vs. Non-South)

Source: Jerrold Rusk, A Statistical History of the American Electorate (Washington DC: CQ Press, 2001), tbl. 7.7, p. 454.

Moreover, Republican governors had been pivotal in national nominating convention politics in the New Deal era. Since 1940, Modern Republicans, including several prominent governors, had been critical in the selection of the GOP's presidential nominees (e.g., Governor Thomas Dewey, NY, and Eisenhower), but their influence came mainly through control of state delegations at the convention.Footnote 55 As late as 1960, Rockefeller successfully pushed Nixon to adopt several progressive platform planks, including an affirmation of the party's stand on civil rights, a negotiation that became known as the “Treaty of Fifth Avenue,” but conservatives, including Goldwater, labeled it “the ‘Munich’ of the GOP.”Footnote 56

The story of the Democratic governors is far more complicated with the diversity of views made possible by a federalism that was quite dramatic in terms of divides across the platforms of state parties and between state party platforms and that of the national party. The party's Southern wing was distinct from the rest of the party, and Southern Democratic governors tended to be much more conservative than their non-Southern counterparts on civil rights issues.Footnote 57

In truth, the gap between the Southern and Northern wings of the party had widened. As Schickler notes, “Advocates for moving the Democratic Party in the liberal direction on civil rights found some of their earliest success at the state level in the North, where locally rooted politicians had much less reason to worry about placating southern Democrats.”Footnote 58 “The federal nature of the American party system,” he continues, “allows intraparty divisions to be institutionalized: Northern state parties accommodated one set of groups and interests, while Southern parties provided a home for a sharply opposed set of interests.”Footnote 59 This shift toward more liberal state parties had implications for gubernatorial nominations. In 1948, for instance, liberals in Michigan successfully nominated New Dealer G. Mennen Williams who, once elected governor, advocated for ending discrimination in the state's National Guard.Footnote 60

Changes to national convention politics, especially the elimination of the two-thirds rule in 1936, empowered Northern liberals at the expense of Southern conservatives, and this transition began to be reflected in the national party platforms with a more progressive stand on civil rights emerging after 1936.Footnote 61 In 1940, for instance, the platform noted that the party “shall continue to strive for complete legislative safeguards against discrimination in government service and benefits, and in the national defense forces. We pledge to uphold due process and the equal protection of the laws for every citizen, regardless of race, creed or color.”Footnote 62 Four years later, the party argued, “We believe that racial and religious minorities have the right to live, develop and vote equally with all citizens and share the rights that are guaranteed by our Constitution. Congress should exert its full constitutional powers to protect those rights.”Footnote 63

In 1948, the split between the ascendant liberal wing of the party and the Southern conservatives resulted in the “Dixiecrats,” led by then Governors Strom Thurmond (SC) and Fielding Wright (MS), bolting the convention. Thurmond won four Southern states and the connection between states’ rights and conservatism on civil rights was clear. Moreover, the weakening of the Southern wing of the Democratic party within national convention politics allowed the distinction between the national party and individual state parties to become manifest. The 1948 party platform took perhaps the most forceful progressive stance on civil rights that the party had yet taken:

The Democratic Party is responsible for the great civil rights gains made in recent years in eliminating unfair and illegal discrimination based on race, creed or color. The Democratic Party commits itself to continuing its efforts to eradicate all racial, religious and economic discrimination.

We again state our belief that racial and religious minorities must have the right to live, the right to work, the right to vote, the full and equal protection of the laws, on a basis of equality with all citizens as guaranteed by the Constitution.

We highly commend President Harry S. Truman for his courageous stand on the issue of civil rights.Footnote 64

By the 1960s, the stand of the national party in favor of civil rights hardened. President Kennedy ultimately pushed forward on efforts to pass national civil rights legislation. President Lyndon Johnson attacked the issue much more rigorously, culminating in the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the 1965 Voting Rights Act, and later the Civil Rights Act of 1968.

In sum, most Republican governors remained moderate on civil rights but were beginning to lose influence within the party to conservative activists while a sharp rift remained within the Democratic party's governors. The national Democratic party was moving left on the issue, but state parties’ stands, including those of the party's governors, remained divergent. Disagreement among the governors and between governors and national party elites would be channeled through party structure.

2. The Formation of a Republican Governors’ Caucus

The RGA first emerged out of rising partisan conflict within the NGC, which had embodied the idea that governors were problem solvers who discussed policy in a nonpartisan manner. GOP governors sought to promote a moderate brand on civil rights and elevate the potential presidential candidacy of Rockefeller while exposing a rift among the Democratic caucus. These actions ultimately led to partisanship becoming more prominent within the NGC in terms of rhetoric and the processes by which the organization operated.

In theory, the partisan balance among the governors did not matter, and the conference was a site of deliberation, not partisan grandstanding. Rarely did the NGC, before the 1960s, even take stands on behalf of its membership, and when it did, the message was something on which the vast majority, if not all, of the governors agreed. This changed in 1961. GOP governors sought to further the presidential ambitions of one of their own and splinter their Democratic counterparts on the issue of civil rights but saw their efforts defeated. In doing so, GOP governors found that numbers and organization within the NGC mattered. While not members of a legislative body, GOP governors found that being in the minority within the NGC was a detriment to their ability to pursue their agendas.Footnote 65

The NGC customarily alternated the chairmanship of the organization by party, leaving it to the party's membership to nominate a candidate from among its ranks. At the annual meeting in Honolulu, however, “the sixteen Republican Governors were shown in sorry disarray.”Footnote 66 The GOP nominated Rockefeller. In response, Democrats, along with a few conservative GOP governors, selected Republican Wesley Powell (NH) despite his initial absence from the conference. Powell flew to Honolulu to accept the nomination in order to comply with the conference's bylaws.Footnote 67 In a letter to then RNC Chairman William Miller, Governor Mark Hatfield (OR) noted that “we have seen the Democratic leadership through [Democratic National Convention (DNC) Chairman John] Bailey, [Hyman] Raskin and others move in on what had for the most part been non-partisan activities in years prior to the Kennedy administration. Governors prided themselves in these Conferences that they went to the heart of state problems and party partisanship was cast aside.”Footnote 68 Hatfield and Smylie publicly pointed a finger at the Kennedy administration, which, they argued, had their hand in Powell's nomination through Bailey's participation in the meetings.Footnote 69 Moderate Republican groups, including the Ripon Society, noted that a lack of organization was detrimental to the party's governors at these meetings and advocated that they coordinate to avoid being logrolled at future conferences.

After the Honolulu meeting, Republican governors formed an informal caucus with the expectation that the party's governors huddle before the start of NGC meetings. The next year, Rockefeller and other Republicans advanced several resolutions to drive a wedge among the Democratic governors. A civil rights resolution was eventually passed as a diluted statement of “American values.” Democratic Governor Fritz Hollings (SC) stonewalled proposals for a more potent statement. Hatfield compared the 1962 NGA meeting's debates on a civil rights resolution to a Senate filibuster.Footnote 70 Governor Michael DiSalle (OH), a Democrat, noted that “at a conference of this kind, we no doubt would come out with some sort of a watered-down civil rights resolution that is supposed to be weak enough to permit the Southern governors to go home safely and the Northern governors to go home with at least a face-saving device.”Footnote 71 Democrats, by preventing or watering down such statements, worked to maintain the broad New Deal coalition. By advancing the issue at NGC meetings, GOP governors could highlight the Democratic party divisions under the watchful eye of the national media.

A year later in Miami, Republicans put on a united front. Governors Smylie, John Love (CO), and Hatfield called for national civil rights legislation and for the NGC to inaugurate a committee on the issue. Democrats reacted by attempting to silence their Republican colleagues through a “gag rule,” a proposal that all resolutions be voted on unanimously rather than a two-thirds majority. Governor Grant Sawyer (D-NV) eventually forced through a motion eliminating the Resolutions Committee, preventing any civil rights statement. Rockefeller argued that “the proposed amendments would do more than gag the expression of collective judgment by this Conference—they would discourage any consideration by this Conference of questions as to which a diversity of view exists.”Footnote 72 Hatfield added that “It is our position [that] civil rights as a subject should be discussed, debated if you will, and the consensus of the Conference should be attained through an expression by vote. Those who insist on state prerogatives should welcome this expression to the Congress, to our constituencies, and indeed to the world which watches so carefully the various interpretations that are here given to that great word: freedom.”Footnote 73 The motion carried by a vote of 33–16.Footnote 74

2.1. 1964: Civil Rights, Barry Goldwater, and the Denver Declaration

Outside of the NGC, efforts to build the RGA were driven by concerns over the national party brand within the 1964 election and the inadequacies of traditional means of state party leaders to influence convention politics. Rockefeller, along with other moderate Republican governors, worried that Goldwater's candidacy would tarnish the national party's standing but, unlike in previous nomination contests, failed to block the insurgent candidacy. This led to the governors issuing the Denver Declaration in which they called for the party to recognize their leadership qualities and intimate ties with state electorates.

As noted above, by the early 1960s, the national partisan scripts on civil rights had flipped. President Kennedy proposed federal legislation in the summer of 1963, and Lyndon Johnson saw the passage of the landmark Civil Rights Act in July of 1964. While most congressional Republicans supported the legislation, Goldwater voted against the law, rooting his opposition in concerns over states’ rights, and his nomination brought the national party's stand on the issue into conflict with those of several Republican governors.Footnote 75

Goldwater's conservative allies had begun to organize and targeted elements of the party-as-organization. As Tulis and Mellow note, “Goldwater's reluctant leadership energized conservative activists to build an organizational infrastructure outside of the mainstream Republican Party that had the capacity not only to sustain itself beyond his defeat but to become a force with which to be reckoned.”Footnote 76 Indeed, the conservative movement found expression in the creation of organizations outside the formal Republican Party. A number of college students organized Young Americans for Freedom in 1960, challenging the eastern establishment and supporting Goldwater's campaign.Footnote 77

Goldwater allies also found expression in party auxiliary committees, including the College and Young Republicans, which, throughout the 1960s, were active in get-out-the-vote efforts for the party. In January 1964, for instance, Rockefeller gave a speech before a Young Republicans convention, which, while generally received well, did not sway members of the group away from the Arizona senator. A split among the delegates at the convention was most visible when Rockefeller touted his support of a federal civil rights law, with Southern Goldwater supporters not partaking in applause.Footnote 78

Conservatives viewed the governors’ organization with suspicion. RNC Chairman Miller, later Goldwater's running mate, noted that the RGA could provide the GOP “organizational muscle” in state and local elections, but Goldwater supporters and advocates for the “Southern strategy” viewed the strong civil rights stand taken by the GOP governors with misgiving.Footnote 79 For instance, conservatives in Congress saw Representative Fred Schwengel's meeting with GOP governors in Miami to discuss minority staffing in the House as an intrusion on the congressional party's territory. The Ripon Society went as far as accusing Miller of attempting to persuade congressional party leaders to avoid a governors’ meeting in Denver in 1963.Footnote 80 A national organization providing a mouthpiece to the likes of Rockefeller, Romney, and Hatfield represented a challenge to the party's conservative wing, which had a greater representation in Congress than among the party's governors.

The governors’ desire to shape the party grew during the 1964 presidential contest as efforts to block Goldwater failed. Goldwater's nomination signaled the declining influence of the party's moderates, who could not block the Arizonan's nomination, especially through control of state delegations. General Lucius Clay, who had supported Eisenhower's candidacy in 1952, argued that “the sheer lack of anybody doing anything has got us where we are. It's a good lesson in how not to select a president.”Footnote 81 This marked a drastic shift from previous Republican conventions. In 1964, there were only sixteen GOP governors, three of whom—Tim Babcock (MT), Paul Fannin (AZ), and Henry Belmon (OK)—staunchly supported Goldwater. The lack of numbers was especially detrimental to a proposal by Governors Love and Elmer Anderson (KS) to change convention voting procedures allowing delegates to vote in secret, thereby freeing “weak-kneed” delegates from the pressures of Goldwater loyalists.Footnote 82 The proposal was rejected by voice vote in committee.

Moderates also lacked a clear alternative to Goldwater. Rockefeller entered several primaries but drew nearly a million fewer votes than the Arizona senator. Romney used an NGC meeting in Cleveland, a month before the GOP convention, as a venue to lambast Goldwater but did not enter the race at that point. Scranton emerged as a late challenger after meeting with Eisenhower in Gettysburg. However, Ike never publicly endorsed Scranton, seeking to stay above the fray of factional politics.Footnote 83 Ultimately, Goldwater's first-ballot nomination with 883 of 1308 delegates and his acceptance speech signaled that conservatives had captured the party. Goldwater was speaking directly to the moderates when he said, “I would remind you that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice! And let me remind you that moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue!”Footnote 84

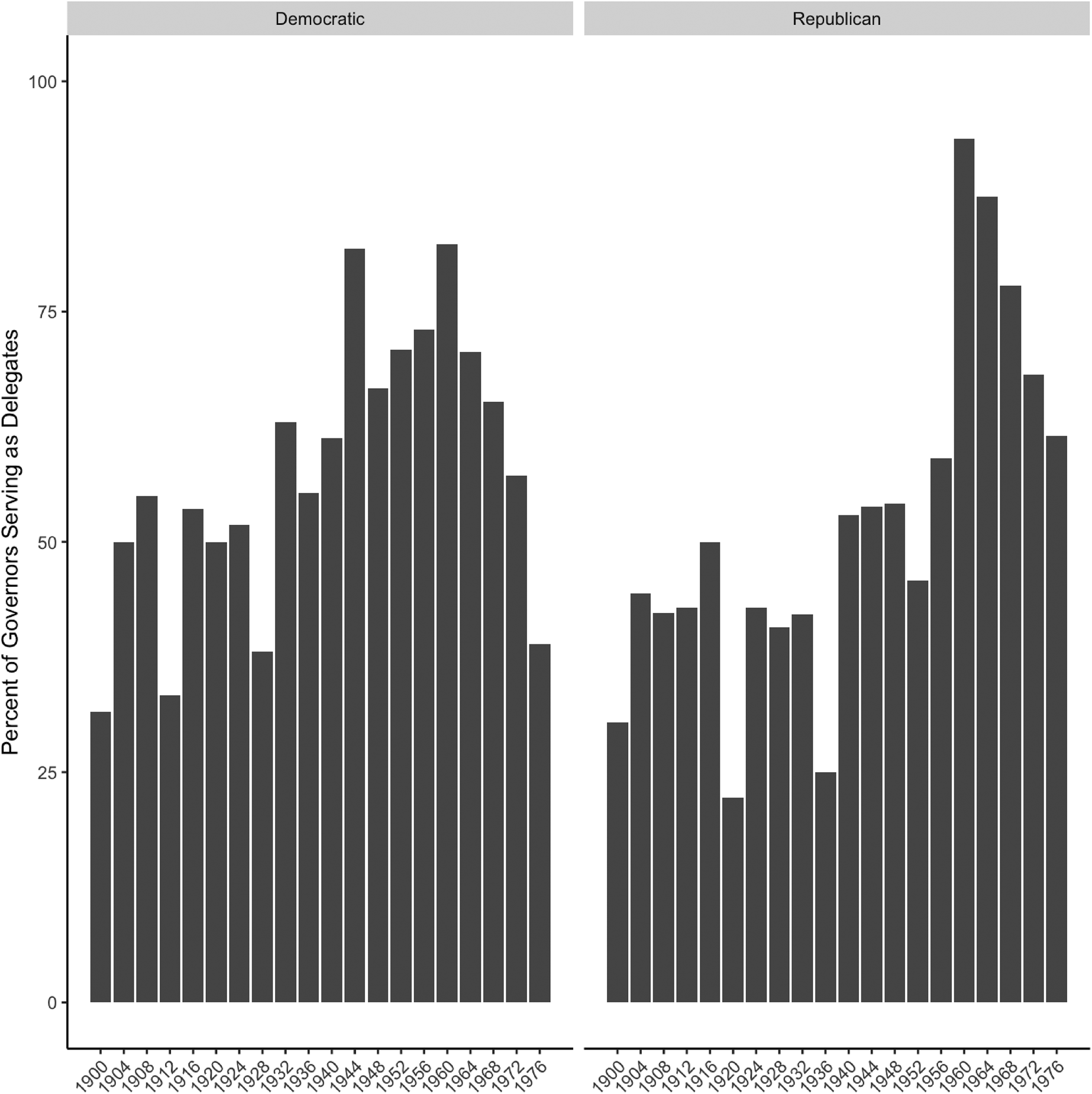

In sum, in 1964 the governors failed in using traditional means of influencing the selection of the nominee—credentials contests and control of state delegations. Goldwater's organization and his success in primaries demonstrated the governors’ weaknesses. Their elevated place within state party organizations was insufficient to block the Arizonan's nomination, and even their unprecedented level of participation at the convention as delegates did little to alter the outcome of the race (See Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Gubernatorial Participation at National Conventions as Delegates by Party, 1900–1976.

The tension that emerged between the Goldwater conservatives and the Rockefeller Republicans was not resolved before the general election. A so-called Unity Conference was held in Hershey in August. The attendees included Goldwater, Miller, new RNC Chairman Dean Burch, Eisenhower, Nixon, several governors, and MCs.

Goldwater sought to fight off the notion that he was an extremist. The view that his candidacy could hurt the party was deeply tied to Goldwater's stance on civil rights. Goldwater promised “faithful execution” of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.Footnote 85 Romney argued that Goldwater's stand was lukewarm, overly legalistic, and failed to convey a clear moral stand. Rockefeller questioned Goldwater on his apparently tacit acceptance of Ku Klux Klan support, noting “you [Goldwater] don't seek their support, but you don't reject their support. And it can very well be said by smart editorial writers that they don't seek it, but they don't say they won't accept it.”Footnote 86

The issue of Goldwater's relationship with the traditional party apparatus was also discussed, with Rockefeller raising the matter of Citizens for Goldwater organizations circumventing state parties. Rocky noted that “the county chairmen are calling now increasingly about the organization of the Citizens for Goldwater and other Goldwater organizations in their counties; that they are not being consulted as to the membership or the leadership of committees and they don't know to whom to talk. Many of the people who are leading these organizations locally are the ones who have fought the organization.”Footnote 87 He added that the Conservative Party of New York, which backed Goldwater, ran over fifty candidates for statewide and local offices, diminishing the GOP's chances of success down-ballot.Footnote 88 Goldwater's supporters were operating outside the state party organizations and were, thus, outside the sphere of influence of Republican governors. Goldwater's candidacy highlighted the factional divide among party elites and the increased ease by which these conflicts could circumvent existing party infrastructure. That is, Goldwater's campaign illustrated that the traditional decentralized party organization did not empower governors within the broader national party.

Nixon called for unity and noted that the governors could be strategic assets for the national party: “We hope to have right in this room several Governors who are not coming up for election, who can be very helpful. Governor Scranton has a national reputation. Rocky has a national reputation. We have several others in that category. Use them. And I think this supplement will take some of the burden off our national candidates so that they can concentrate where they are needed, concentrate in those States, the swing States, to win.”Footnote 89 In Nixon's eyes, what made the governors powerful was not their place within state party organizations but their reputation among voters at the national level.

Goldwater's loss (in which he won just 6 percent of the nonwhite vote, 26 percentage points less than Nixon's in 1960) precipitated renewed conversation about the party's national brand, and the relative electoral strength of the governors gave them reason for believing their approach within their respective states should be adopted nationally.Footnote 90 As Heersink notes, “Who within the national minority party decides what groups the [national] committee targets is a product of the party's electoral performance.”Footnote 91 In this case, the magnitude of Goldwater's loss had, at least temporarily, discredited the conservative stalwart, and the relative success of some GOP governors served as vindication for their right to shape the party in the lead-up to the 1966 midterms and the 1968 presidential election. Republicans netted one pickup in gubernatorial seats with several high-profile governors reelected by respectable margins, including Romney, John Chafee (RI), and Daniel Evans (WA). As Smylie noted, “we are a leaderless party because no one has earned the right to that leadership by winning an election.”Footnote 92

Governors sought to fill a perceived leadership void and did so through organizational developments and by attempting to shape the party program. After the election, Romney wrote a sternly worded letter to Goldwater in which he argued that “the party's need to become more broadly inclusive and attractive should be obvious to anyone.”Footnote 93 He went on to argue that Goldwater was complicit in extremist attempts to infuse racial conservatism into the platform, noting that “a leading Southern delegate in private discussion with me, opposing my civil rights amendment after it was introduced but before it was offered, made it clear there had been a platform deal that was a surrender to the Southern segregationists, contrary to the entire tradition of the party. And it appeared that there was a willingness to accept, perhaps even welcome, the support of irresponsible extremists such as those you clearly reject in the December 21, 1964, U.S. News interview.”Footnote 94

At a December 1964 meeting in Denver, Republican governors drafted and unanimously agreed upon formal Articles of Association and issued the “Denver Declaration.” In the Declaration, the seventeen governors and governors-elect argued that “the 1964 election made it abundantly clear that national party policies have momentous impact on the ability of the Republican Party to win elections within the States. Republican governors, therefore, have a clear-cut duty to participate with other leaders of the Party in formulating positive policies with broad appeals to bring before all the American people.”Footnote 95 In the final analysis, conflict within the NGC (between the parties) and the 1964 election (within the GOP) hastened the party's governors to find new means of asserting themselves more vigorously in national partisan affairs. The RGA provided a means to this end.

3. The Democrats Respond: The Origins of the DGC

Democratic governors also first organized their partisan caucus within the NGC. In part, they were responding to the efforts of their GOP counterparts. They also espoused the view that their counsel was not being heeded by national Democratic officials. The efforts to initiate a caucus in the NGC reflected a realization that the party's governors were divided and that coordination could counter efforts to expose these divisions and to signal to Democratic elites in Washington that governors remained important players within the national Democratic Party.

The Democratic governors voiced desires to be more influential in national political decision making. Reporting on the 1964 Conference in Cleveland, Henry Gemmill noted that “a few days of immersion in a governors’ conference can give you the feeling that all state executives are affable, some are able, and none are influential.”Footnote 96 Governor Edmund G. “Pat,” Brown (CA) used the forum to push for the formation of a Council of Governors, similar to the president's Council of Economic Advisors, which could advise President Johnson, arguing that “governors, in daily touch with the immediate needs of their particular states, could be most helpful to the President, if there were some way that we could regularly meet with him.”Footnote 97

Other Democratic governors of varying ideological persuasions echoed Brown's comments. Connally, presiding over an NGC session on federal-state relations, noted that “we are moving toward an economic and social life which tends more and more to obliterate state lines, to obscure the position of the states and increase the power of the federal government.”Footnote 98 At the 1965 meeting in Minneapolis, NGC then-Chairman Sawyer argued that “increased federal presence in areas previously reserved to and jealously guarded by the states has resulted from inaction and, in too many cases, invitation. Too often our states have been content to stand aside while Washington found solutions to local problems and financed their implementation.”Footnote 99

Democratic governors were also aware of the potential good that could come from organizing to counter the opposition. A month after the NGC's 1965 meeting, Connally, an ally of the president, was named the chairman of a new Democratic Governors’ Caucus (DGC) and appointed an Executive Committee including Brown, John Dempsey (CT), Frank Morrison (NE), Albertis Harrison (VA), and Richard Hughes (NJ). The committee demonstrated a commitment to regional representation and the ideological breadth of the party. Harrison was allied with Senator Harry F. Byrd and had defended the state's “massive resistance” to desegregation in several federal court cases, including a high-profile case regarding the closure of public schools in Prince Edward County. Dempsey was a New England liberal who led the way on environmental legislation and was allied with DNC then-Chairman Bailey. Hughes was an ally of LBJ, contributing to the 1964 Democratic National Convention being held in Atlantic City.

4. The RGA and The Republican Party as Organization

The most immediate and direct impact of the GOP governors’ activities on the national party was the addition of a new and permanent national organization, one that demonstrated that these actors were adapting to a party system more focused on national politics and programs than on patronage-driven state and local party machines. Through the RGA, the governors helped to develop the modern national party-in-service, creating new leadership roles and augmenting the resources of the national party infrastructure.Footnote 100 This new form of party was “an organization designed around the ambitions of office seekers—candidates now largely responsible for their own campaigns.”Footnote 101 This party-in-service did not “control” candidates but rather “conduct[ed] polls for candidates who would not otherwise be able to use them, and suppl[ied] access to advertising resources, whether expertise, facilities or ads it created. It could offer seminars or ‘campaign colleges’ for candidates and their staffs and even find them managers if desired. The party could provide position papers, training on policy problems, and possible (partisan) solutions—and the means to advertise them.”Footnote 102 Concerned with the national party brand, the governors also turned their attention to other national party organizations.Footnote 103

Areas of focus for the governors were the RGA, a fight over the RNC chairmanship, party-building activities conducted through the Republican Coordinating Committee (RCC) and other auxiliary committees, and convention politics. The party's governors did not simply seek to rebuild state party organizations. Rather, the RGA allowed the governors to contribute to national party-building efforts in ways that reflected a more nationalized and programmatic party system.

4.1. The RGA as National Party Organization: Serving the Governors

The RGA provided electoral services to governors and gubernatorial candidates, publicized its membership's accomplishments, critiqued opponents, and coordinated its members’ activities in national party affairs. The organization created new roles for the governors within the party. The governors agreed to the RGA having an executive committee, including the chairman, elected annually, and at least two other sitting governors. The chairperson served as a national spokesperson who addressed national conventions and was tasked with bringing the party's governors together. Smylie was reelected to the position. The chairmanship has been held by several prominent governors, including Ronald Reagan from 1968 to 1970 (see Table 4).

Table 4. RGA and DGC/DGA Chairmen and Later National Political Careers

Additionally, a policy committee, which issued policy papers and resolutions, and a gubernatorial campaign committee, which aided gubernatorial and state legislative candidates, were established. Though the initial staff was small, the RGA reached out to academics, including political scientists Robert Huckshorn and Cornelius Cotter, in filling these positions.Footnote 104 Walter Devries was tapped to lead campaign school sessions on winning over independent voters.Footnote 105 By 1966, the RGA had a full-time executive director, a public relations officer, and a research coordinator. The organization's staff included political operatives who had worked for other Republican organizations. Richard Fleming, who became executive director in 1967, had worked for the RNC's research division. The staffing of the organization, thus, built on preexisting GOP networks.Footnote 106

The group instituted seminars for gubernatorial candidates, circulated RNC-sponsored research on congressional redistricting, and had its own suite, with RNC-provided staff, at Republican conventions.Footnote 107 Smylie noted during one of the campaign “schools” in Denver that this was “the first time I think in the history of either political party in the United States to coordinate and to be of some assistance on a national basis to gubernatorial candidates in the several states.”Footnote 108 These seminars set a precedent for the organization contributing to governors becoming national party builders.

Further, the Articles of Association called for semiannual meetings of the governors, which would develop comradery and provide opportunities to engage with national party leaders. The meetings were almost always attended by the RNC chairperson, congressional leadership, and, later, members of GOP presidential administrations. During the mid-1960s, the RGA held at least two meetings per year in addition to confabs during NGC meetings. The meetings became media events in themselves, elevating the governors’ national media profiles.

4.2. Seeking Influence and National Party Success: The RGA, the RNC, and the RCC

Through the RGA, the governors sought to expand their influence over the national party and rooted their arguments in the significant party losses of 1964. Several efforts centered on changing elements of the national party organization, including the leadership of the RNC and the activities of party auxiliary committees. In doing so, the governors asserted themselves not just within state party organizations but also within national party organizations.

Studies of party-building efforts, including those by Klinkner, Galvin, and Heersink, have emphasized electoral loss as a key motivating factor for organizational investments and rebuilding and rebranding efforts.Footnote 109 Republican losses in 1964 were substantial, and GOP voters seemed to cast some blame on Goldwater and his allies. A Gallup poll conducted shortly after the election, for instance, found that, 20 percent of GOP voters said the party should move in a more moderate direction, while just 8 percent said the party should move or stay to the right. Further, 32 percent of GOP voters suggested that the GOP change the party's leadership, and 20 percent called for more party unity.Footnote 110 The governors built on these sentiments, and the RGA became a venue through which they exerted some influence over national party organizational affairs, often in partnership with other like-minded individuals in the party.

GOP governors attempted to wrestle control of the RNC from Goldwater and Burch. They joined Senator Thruston Morton (KY) in calling for Burch to be replaced. Even Eisenhower argued that in attempting to keep Burch, Goldwater “desires to read out of the party counsels nearly all the Republican governors. I am convinced that this is not an effort to create unity, but merely an insistence on personal control by the Goldwater cabal.”Footnote 111

The 1964 Denver RGA meeting was a repudiation of Goldwater and Burch.Footnote 112 Leading RGA figures promoted ousting Burch ahead of an RNC meeting in January. Smylie sent a letter to members of the RNC, arguing that the Denver Declaration provided “a foundation on which the Party can rebuild toward a substantial victory in 1966.”Footnote 113 Scranton, in a letter to Eisenhower, noted that “if the Goldwater group believes that they do not have the votes to keep Burch by the time January 22nd comes around, I believe that a ‘nice way’ of arranging Burch's resignation could be worked out before the meeting, but if the pressure lets up between now and then, I believe they will try to retain him on some plan or other, or at least try to continue to control the National Committee.”Footnote 114

Burch expressed his intent to stay: “I am not staying on simply because Senator Goldwater wants me to stay. And I'm not staying on because Governor Smylie wants me to go.”Footnote 115 Burch endorsed the Denver Declaration but focused his support on the formation of a campaign committee.Footnote 116 Ultimately, Bliss, the chairman of the Ohio State Republican Party, who, as Conley notes, “believed that developing a ‘sound organization,’ and electing Republicans, offered the most reliable means of ensuring that the party and its conservative policies remained viable,” was selected as the next chairman.Footnote 117 “National party leadership, on the whole,” Conley continues, “despite itself being divided by the deepening liberal and conservative schism within the party, chose party unity over continued internal ideological warfare.”Footnote 118 Rowland Evans and Robert Novak noted that “the goal [was] not so much party unity as party growth.”Footnote 119

The relationship between Bliss and the RGA proved to be symbiotic. Bliss granted the RGA office space within RNC headquarters and, after the 1966 midterms, expanded the RNC's expenditures for the RGA, offering $100,000 a year as an operating budget.Footnote 120 This more than doubled previous RGA outlays and allowed the group to expand its staff, open its own headquarters, and replicate its campaign schools in 1968.Footnote 121 Bliss, thus, invested in the RGA and state parties while promoting a national party image that allowed for active gubernatorial leadership capable of expanding the base of the party at the state level.Footnote 122

Certain governors also became active in leadership contests within party auxiliary committees, demonstrating that the governors’ attention to the national party organization at large. For instance, the Rockefeller brothers and Romney actively promoted the election of moderate Gladys O'Donnell over Phyllis Schlafly for the leadership of the National Federation of Republican Women in 1967.Footnote 123 Schlafly had backed Goldwater in 1964.

The governors also promoted establishing a Republican Leadership Council, which ultimately led to the creation of the RCC. The RCC was created to develop new policy proposals, and the governors sought to make sure that their policies were not overshadowed by the congressional wing of the party. Governors were given five slots on the committee and sent Smylie, Rockefeller, Romney, Scranton, and Love as their representatives.Footnote 124 The governors’ delegation to the RCC was expanded to eight the following year. The delegation had a distinctively moderate bent, and all the original gubernatorial participants, except for Smylie, were often touted as presidential or vice-presidential contenders.

The RCC's establishment was not unprecedented in American party history. In fact, the GOP was acutely aware of the Democratic Advisory Council when the group was formed. For our purposes, the inclusion of governors, and their emphatic desire to participate, in the RCC is telling. Karl Lamb has illustrated that gubernatorial involvement in previous GOP national party-building efforts had been uneven and often meager. The Ogden-Mills Commission, formed in 1919, drew less than 10 percent of its 173 members from state and local government officials. The Glenn Frank Committee, established during the New Deal, included only three state and local elected officials. The Mackinac Conference was exceptional by including the twenty-four GOP governors elected in 1942. The Percy Commission, established with the blessing of Eisenhower, included only four members of state and local government out of forty-three spots.Footnote 125

The governors’ inclusion in the RCC was largely welcome, but some within the party did not want them to dominate the group. Everett Dirksen, for instance, argued: “The only elected Republican officials of the Federal Establishment are the 32 Republican members of the United States Senate and the 140 members of the House of Representatives. Obviously and beyond dispute, they will guide Republican Party policy at the national level, in the absence of a Republican President and Vice President, by the record they write in the Congress. It is their responsibility.”Footnote 126 The governors were to be “an additional repository of advice.”Footnote 127

Klinkner notes that the RCC “provided an internal forum for discussion between party factions and thereby helped to unify a badly divided party” and “produced a steady flow of reports and statements spelling out constructive, if not exciting, Republican positions on the issues and criticisms of the Johnson administration.”Footnote 128 He goes on to argue that “the mortal wounds of the liberal and moderate Republicans were less apparent than they have become in hindsight” and that “an organizational response was the best they could hope for given their diminished influence.”Footnote 129 Nevertheless, the governors’ participation in the RCC tightened their place within the national party.

While much of the party's gains in the 1966 midterm elections are attributable to LBJ's declining popularity, Vietnam, and the emerging urban crisis, GOP gubernatorial success was broad based. The party made gains in the South and the West, and it held seats in the Northeast. While Reagan was elected in California, several moderates, including Winthrop Rockefeller (AR) and David Cargo (NM), were also elected. Two years later, Robert Ogilvie (I) and Robert Ray (IA), both moderates, were elected in competitive races. In sum, the governors remained an ideologically broad group during this period, and several governors benefitted from the party-building efforts of the RNC and the RGA in 1966.

4.3. The RGA and the NGC: Republican Governors Acting as Part of a National Team

After 1964, RGA activities within NGC meetings emphasized party-branding efforts. The GOP governors highlighted their disagreements with LBJ and the Democratic Congress and emphasized the policy successes they had in the states. In this way, the RGA underscored the distinctiveness of Republican governors from the national Democratic Party, despite the moderate bent of many GOP governors at the time. The RGA's role in the NGC is the clearest manifestation of the party's role in promoting a national form of partisanship.

The formation of the RGA did not result in formal changes to the NGC's constitution or bylaws. It did, however, contribute to partisanship structuring the processes by which the organization operated. For instance, at the end of the 1965 meeting in Minneapolis, and for the first time in NGC history, the nominating committee for officers issued two reports—one from each party. Governor Brown lamented, “There never, to my knowledge, has ever been any move to amend these Articles of Organization by providing that the Republican Governors shall caucus and the Democratic Governors shall caucus and then the Nominating Committee shall just be a tool of the respective political caucuses of the political parties. It seems to me that the thing that is really fraught with danger is the use of this great Conference for the purpose of some political advantage to either one party or the other.”Footnote 130 The NGC had developed into “a forum for the heated discussion of national programs and federal-state relations,” and now had clear partisan demarcations.Footnote 131

This was true even in discussing foreign affairs. In 1965, Democrats asked for the NGC to issue a statement supporting remarks made by the president in a televised speech that occurred during the annual meeting. Romney, generally supportive of liberal internationalism, worried that using the conference in this way would bolster support for the Democrats.Footnote 132 Governor Burns, a Democrat (FL), responded by noting that “at this time that all partisanship must be laid aside and that a word of patriotism must be substituted. We have elected through the democratic processes a leader for this nation. I think that it behooves the people of this nation, certainly the Governors of this nation, to stand as one, united, in support of the action that has been announced on behalf of this nation. We as Governors are not informed in the field of diplomacy nor are we informed of the give and take at the negotiation table. We, like every other citizen of these United States, have our allegiance to the nation and to its leadership.”Footnote 133

Partisan discourse also emerged over the issue of Vietnam. Smylie criticized LBJ's Southeast Asia policy on the television show, Your Right to Say It.Footnote 134 Love, elected RGA chairman in 1966, traveled to Vietnam and announced support for U.S.-led bombing campaigns and the blockade of the North Vietnam port of Haiphong, and he went as far as to say that “the ultimate answer” for the conflict “has to be political.”Footnote 135 Romney also traveled to Vietnam, though his visit proved detrimental to his presidential ambitions. James Foster noted that “the war is a political issue. Any public figure who can identify himself with any degree of expertise on Vietnam stands to gain political mileage.”Footnote 136

The RGA also acted as a mouthpiece on behalf of GOP governors outside of the NGC. For instance, it issued a statement supporting the ratification of the 24th Amendment, touting the fact that states with GOP-controlled legislatures were much more supportive of the prohibition of poll taxes than were states controlled by Democrats and criticizing President Johnson for opposing previous attempts to eliminate the practice.Footnote 137 The RGA also publicly condemned the activities of Democratic operative Bobby Baker, who was then being investigated for bribery by the Senate.Footnote 138

LBJ's domestic policies also came under fire. Chafee, in a speech celebrating Lincoln's birthday, argued that the Great Society treated individuals as “economic units” who were “to be escorted from poverty by the grace and charity of a fatherly federal government.”Footnote 139 He also took on LBJ on crime, noting GOP gubernatorial leadership on the issue, including that of Rockefeller who had called for five times the increase in police ranks in New York City than did the president.Footnote 140 The governors also responded directly to LBJ's 1968 State of the Union address. Chafee led a press conference separate from that held by the congressional wing of the party.Footnote 141 Several others attacked the president's seemingly bloated budget.Footnote 142

In the final analysis, the RGA fostered the governors’ involvement in party-branding activities, allowing them to draw distinctions with policies stemming from Washington, particularly those of President Johnson. In doing so, the governors often pointed to potential alternatives developed within the states. Fiscal conservatism and active agendas on crime were issues that the governors emphasized and became important parts of the Republican Party's agenda, at the state and the national levels, over the coming decades. The RGA's branding activities within and beyond the NGC are perhaps the clearest and earliest means by which the organization contributed to national partisan polarization.

4.4. The RGA at the 1968 Convention: Platform and the Convention as Spectacle

In the 1968 presidential election, governors mobilized in a fundamentally new way—one that emphasized the importance of party program, the leadership qualities of the governors, and the power of collective action over traditional roles as delegate brokers. That is, gubernatorial activity at the convention, coordinated through the RGA, demonstrated how governors adapted to an increasingly nationalized and programmatic party system.

The governors played important roles leading into and during the 1968 Republican Convention, not as presidential kingmakers but as candidates, shapers of the party platform, and featured members of the convention as spectacle. Despite not pushing one of their own to the top of the ticket, gubernatorial participation at the convention remained high by historical standards (see Figure 2). In 1968, twenty-one of the twenty-six sitting governors served as delegates.Footnote 143

RGA meetings were often framed as venues for challengers to Nixon to capture national attention. The notion that governors could be kingmakers through influencing delegates on the floor had not died within the minds of journalists. The 1968 election was still within the era of a “mixed” system of presidential selection in which party elites retained a large degree of latitude in determining the presidential nominees.Footnote 144 However, in 1968 the governors generally refrained from attempting to be presidential kingmakers. The RGA did not make an official endorsement of any candidate that year, setting a precedent for the organization not broken until the 2000 election. Without (near) unanimity by the governors and with three of the RGA's members running, a formal endorsement by the RGA risked exacerbating division. The schism between the conservative and liberal wings of the party was still fresh in their minds. Love noted at a December 1967 RGA meeting that “Nelson Rockefeller may be our strongest candidate, but I think we can win with Dick Nixon or George Romney too. I think any one of them could win it and be a good President. I just don't want to wind up with a candidate who will lose to the Democrat, whether it's Lyndon Johnson or Bobby Kennedy.”Footnote 145 A number of states sent uninstructed delegates to the convention.Footnote 146

The governors used the RGA to ensure that they received prominent places in the convention as spectacle. Evans gave the keynote address, in which he called for robust Republican leadership and reflected the governors’ approach to racial justice and environmentalism. He said, “There is no place in that [the American] dream for a closed society, for a system which denies opportunity because of race, or the accident of birth, or geography or the misfortune of a family. Only when everyone has a stake in the future of this country; only when the doors of private enterprise are opened to all—only then will each person have something to preserve and something to build on for his children.”Footnote 147 Governors could lead on these issues, given their importance in the construction of public policy at the state level.

Leading into and during the convention, the RGA's members focused their efforts on shaping the party platform rather than taking part in credentials disputes. Governors played a central role on the Platform Committee. Dirksen was, to the chagrin of Chafee, named chairman. Chafee had written to Bliss requesting Shafer be given the position of co-chair.Footnote 148 Ultimately, Chafee, not Shafer, was named deputy chairman and Governors Walter Hickel (AK) and Louie Nunn (KY) were named vice chairmen.Footnote 149 This marked something of a win for the RGA, given that the last sitting governor to serve on the Platform Committee was Tom Heany in 1948.Footnote 150