1. Introduction

In an interview with the Springfield Republican in December 1964, the attorney general of Massachusetts, Edward Brooke, reflected on his party's crushing defeat to Democratic President Lyndon Johnson in that year's election: “Historically it [the Republican Party] has been the party of freedom, equality, and emancipation.… It took a new road in 1964 which I could not travel, but I'm trying to put it back on a road I can travel.”Footnote 1 It is now clear that Brooke, a pro–civil rights Republican and the grandson of slaves, was already on the losing side of the battle for the Republican Party's soul. Barry Goldwater's nomination as the 1964 Republican presidential candidate was not the cause of the party's shift toward racial conservatism; it was a symptom of a long-standing process of racial realignment.Footnote 2 The party's grassroots had already been shifting for decades away from its heritage as “the party of Lincoln and Emancipation.”Footnote 3 As Eric Schickler puts it, figures like Brooke had become “the rear guard of a party whose coalition partners had long since stopped caring about civil rights and whose core party voters had taken a conservative position on civil rights initiatives.”Footnote 4

Ronald Reagan is understood to be the heir to the Goldwater Revolution.Footnote 5 Reagan had catapulted himself to the forefront of Republican Party politics in his service to the Goldwater campaign with his famous “A Time for Choosing” speech in October 1964.Footnote 6 Reagan opposed all three of the most significant civil rights bills of the Johnson administration: the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA), and the Fair Housing Act of 1968. Like Goldwater, Reagan argued that these laws interfered with individual liberty and were an overreach of federal authority in the affairs of states and individuals. Reagan won his first election in 1966, as governor of California, in a campaign that portrayed Democrats as the party of feckless welfare scroungers “freeloading at the expense of conscientious citizens.”Footnote 7 Throughout the coming years, Reagan would articulate a brand of free-market conservatism that opposed many forms of redistribution and regulation, including remedies for centuries of racial oppression in the United States.

The story of the Republican and Democratic Parties’ “racial realignment” is well known.Footnote 8 From the 1960s onward, the Republican Party has been widely understood to be dominated by a “color-blind” policy coalition, which denies the role of government in remedying legacies of historic racism.Footnote 9 While not supporters of active racial discrimination, color-blind conservatives oppose government measures designed to correct racially disparate outcomes, especially when intentional racial discrimination cannot be proven.Footnote 10 In addition, conservatives are generally suspicious of federal government involvement in policy domains traditionally reserved to the states, such as education and election administration.

For the most part, the Reagan administration's racial policy agenda aligned with this color-blind, states’ rights conservative outlook. Reagan, like Richard Nixon before him, tried to slow the pace of school integration by limiting, where he could, the practice of busing.Footnote 11 Reagan withstood considerable public outcry when he stood by so-called segregation academies when they faced losing their tax-exempt status.Footnote 12 He pushed back against affirmative action.Footnote 13 He reoriented the Equal Opportunity Commission, the bastion of civil rights liberalism in the federal government, in a sharply more conservative direction.Footnote 14 Yet, one area where Reagan failed to reverse civil rights liberalism was the VRA. As Abigail Thernstrom observed at the time, “The Reagan administration has been a frequent foe of civil rights groups on busing and employment quota questions, yet in the enforcement of minority voting rights, its record has differed little from that of its predecessors.”Footnote 15 While Stephen Skowronek regarded Ronald Reagan as a “reconstructive” leader, on voting rights he remained a “regime affiliate.”Footnote 16

According to conservatives, there were two key provisions, contained in Sections 2 and 5 of the VRA, that violated color-blind and states’ rights principles. Section 2 enabled citizens to sue jurisdictions that denied or abridged the right to vote on account of race. Liberals argued that Section 2 cases ought to be brought against jurisdictions on the basis of patterns of racially disparate election outcomes, whereas conservatives argued that it was imperative to prove that an election procedure had been formulated with a deliberate intent to discriminate. Section 5 required jurisdictions with a history of voting rights violations to seek approval from the federal government before making any changes in election law or practice. Conservatives regarded this provision as an intrusion of the federal government into the affairs of states and an unjust punishment of the mostly southern states who were covered by Section 5 “preclearance.” For supporters of the VRA, Section 2 was viewed as its “sword” and Section 5 as its “shield.”Footnote 17 The effectiveness of these provisions has led commentators to regard the VRA as the most powerful civil rights law in U.S. history.Footnote 18

In the early 1980s, Ronald Reagan made his dissatisfaction with these provisions of the VRA well known. Running for president, he sided with a Supreme Court decision in 1980, City of Mobile v Bolden, which interpreted Section 2 according to the weaker, conservative “intent” standard. In an interview a few weeks after his election, Ronald Reagan expressed outright opposition to Section 5, calling it “humiliating to the South.”Footnote 19 For civil rights activists, this was a perilous time for the VRA. Without new legislation overturning Bolden, Section 2 would be left in its weakened (intent standard) form, and Section 5 was due to expire altogether in August 1982. The clock was ticking. To make matters worse, Republicans won control of the Senate in the 1980 elections for the first time since 1952. Emblematic of this metamorphosis, the chairmanship of the critical Senate Judiciary Committee—through which a new version of the VRA would need to travel—transferred from the liberal Ted Kennedy to the arch-segregationist Strom Thurmond.Footnote 20

Given this rightward partisan shift, it is prima facie surprising that in June 1982, President Reagan signed an extension of the VRA that overturned Bolden, strengthened Section 2, extended Section 5, and gave to civil rights advocates, in the words of one, “everything we wanted.”Footnote 21 Ari Berman describes the 1982 renewal as “the strongest … Voting Rights Act ever enacted.”Footnote 22

In response, the conservative weekly Human Events posed the question, “how [could] such a genuinely radical measure become law during the Administration of the most conservative Presidents of our time and during a Congress that is among the most conservative?”Footnote 23 This puzzle is the focus of this article, and it has been given surprisingly little attention. Dianne Pinderhughes authored one of the only stand-alone studies of the 1982 extension.Footnote 24 Her work focused on the role of interest groups, particularly civil rights organizations, that lobbied extensively for a robust extension of the law. Pinderhughes rightly shows the success of these groups in shaping the powerful version of the VRA passed by the Democratic House in 1981. Abigail Thernstrom is indebted to Pinderhughes's research in her chapters on the VRA extension in her book, Whose Votes Count?. Thernstrom also shows the effectiveness of civil rights groups in shaping the content of the House bill, describing it as “a triumph for the civil rights lobby.”Footnote 25 Yet, both accounts minimize the role of the Republican Senate partly because the final version looked so much like the House bill. Their research was also conducted mainly in the 1980s when they lacked access to the internal papers of the Reagan administration and other senior Republicans, which have been consulted for this research.

Two more recent histories of the VRA mention the 1982 extension, but they only cursorily explore why Republicans failed to dismantle the act when they had the chance. Gary May sums up conservative support for the 1982 renewal in the words of Georgia Congressman Bo Ginn, “It means little to whites. It means a whole lot to blacks.”Footnote 26 Ari Berman presents the 1982 renewal as part of a broad, bipartisan voting rights consensus that lasted until legal revolutionaries took hold in the 1990s and began to dismantle the law in the courts.Footnote 27

Jesse Rhodes's book Ballot Blocked goes further than previous analyses in attempting to answer the question of why Republicans consented to a VRA extension that seemingly violated core conservative principles about the role of government and color-blindness. For Rhodes, the Reagan administration's support was largely a defensive move, motivated by a fear of being labeled racist and a desire not to “alienat[e] people of color and moderate white voters thereby harming their party's electoral prospects.”Footnote 28 Accordingly, Reagan had no choice but to sign whatever version of the VRA Congress put before him. Rhodes's book contends that conservatives were prepared to lend visible support to the VRA extension because they were confident that bureaucratic inaction by the executive branch and through conservative appointments to the federal judiciary would undermine the VRA's effectiveness without the Republican Party shouldering any direct blame.Footnote 29

While intuitively appealing, this explanation has some holes in it. For example, if the administration was so determined to use the courts to weaken the VRA, then why did Reagan sign a version of the VRA that tied the hands of future courts by removing the ambiguity about Section 2's standard of discrimination? If making any criticism of the VRA was so politically toxic, why did Reagan and Department of Justice (DOJ) officials publicly do so in the lead-up to the VRA extension? This article does not accept the contention that the version of the VRA signed by Ronald Reagan in 1982 was its inevitable final form. I argue that there was far greater contingency than previous accounts have allowed. For nine months, the House's version of the voting rights bill languished in Strom Thurmond's Judiciary Committee. This period of uncertainty can be understood as a critical juncture in the legislative history of the VRA. It was not preordained that the House bill would survive largely intact. That it did is a consequence of political entrepreneurship.

There were two potential stumbling blocks to the passage of the House bill: the Reagan administration and the Senate Judiciary Committee. This article shows that the Reagan administration was much more internally divided about which version of the VRA to support than recent accounts have suggested. A mix of party-builders, policy entrepreneurs, and genuine believers conspired to support a version of the act opposed by color-blind ideologues in the DOJ. Archival research of internal discussions held among White House staff show that black Republicans played an important, but hitherto undiscussed, role in arguing for the House bill within the administration. The record shows that even Edward Brooke, by then an ex-senator, was involved in the White House lobbying effort.

In the Senate, Judiciary Committee member Bob Dole emerges as the pivotal actor. Dole crafted a compromise that brought most Republicans along, while retaining the Democrats’ effects-based standard for Section 2 and extending Section 5 for 25 years.Footnote 30 Pinderhughes, Thernstrom, May, Berman, and Rhodes all credit Dole with this key intervention, but in each of these accounts, the Dole compromise is given little more than a few sentences of attention.Footnote 31 Drawing from primary sources in Bob Dole's archives at the University of Kansas, this article endeavors to “bring Dole back in.” The Dole compromise, as civil rights lawyer Joseph Rauh said, “was no compromise at all.”Footnote 32 There were several other options available to Dole. Time was on the VRA skeptics’ side. Had Dole not acted and the bill continued to stall until the August deadline, it is possible that Section 5 preclearance would have been lost altogether. Equally, and more plausibly, Dole could have sided with the DOJ and argued for a clean extension, which in effect would have preserved Bolden's intent-based standard in Section 2. By choosing to champion one particular path—strengthening Section 2 and extending Section 5—Dole's intervention ensured that the VRA would endure as the most effective piece of U.S. civil rights legal infrastructure for decades to come.

This article not only revises our understanding of the passage of the 1982 VRA extension, but it also obliges us to reconsider the place of race in the Republican Party at the height of the Reagan era. For all of the ways in which the Republican Party had realigned on race in the post–New Deal period, there were still some (admittedly faint) echoes of the tradition advocated by Edward Brooke as late as the 1980s. Ultimately, these considerations were by no means strong enough in the 1980s to be the decisive or even major explanation for the VRA's extension, but their presence suggests that there were real differences within the Reagan administration on some aspects of the civil rights agenda that have not been fully appreciated.

2. Passing the Voting Rights Act of 1982

In 1980, the VRA faced its first major judicial setback when the Supreme Court ruled in Mobile v Bolden that litigants were required to show that officials intended to discriminate when drawing district boundaries and writing election rules. Bolden was described by one civil rights advocate as the “first obituary to this country's commitment to meaningful protection of voting rights.”Footnote 33 Demonstrating intentional discrimination is typically more difficult than showing a pattern of disparate impact. Desmond King and Rogers Smith point out that “opting for the former always means opting for the weaker measure.”Footnote 34 In the Bolden case, the black litigants from Mobile, Alabama, were ultimately successful in showing intentional discrimination, but to do so, they needed to produce historical evidence from when the boundaries were drawn a century earlier. The case took 4,000 hours of time from expert researchers and more than a year of the district court judge's own personal research.Footnote 35

The same year as the Bolden decision, Ronald Reagan was elected president. Reagan's election did not bode well for the VRA's survival. Within weeks of his election, Reagan told Time magazine, “I was opposed to the Voting Rights Act from the very beginning” and suggested that it had perhaps met its purpose.Footnote 36 Reagan's DOJ praised the Bolden decision. Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights William Bradford Reynolds argued that the decision “put to rest” the debate over the intent or effects standard of discrimination.Footnote 37

In August 1981, the Democratic-controlled House passed an extension of the VRA intended to sustain and strengthen the law. The House's version of the VRA made Section 5 preclearance permanent, and it amended Section 2 to overturn Bolden by clarifying that discriminatory effect was a sufficient standard to find a jurisdiction in violation of the law. Thernstrom records that such changes “strengthen[ed] the act radically” and, especially, “radically altered Section 2.”Footnote 38 The House bill (H.R. 3112) was sent to the Senate (S. 1992) where its most difficult test was its passage through the Senate Judiciary Committee. In addition to Chairman Thurmond, who had voted against the original VRA and all of its subsequent iterations to that point, the relevant subcommittee was chaired by Senator Orrin Hatch, who warned that the House bill would turn the United States into “a country in which considerations of race and ethnicity intrude into each and every public policy decision. Rather than continuing to move toward a constitutional color-blind society, we will be moving toward a totally race-conscious society.”Footnote 39 Hatch made clear that the color-blind policy alliance was opposed to the effects-based standard contained in Section 2 of the House bill.

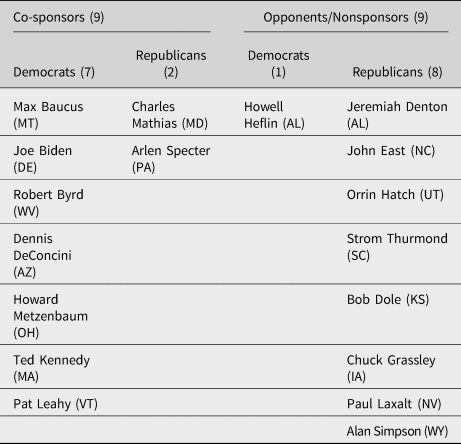

Nine of the eighteen members of the committee had signed on as co-sponsors to the House version of the bill. One committee Democrat (Howell Heflin of Alabama) refused to sign on as a co-sponsor, but two committee Republicans (Charles Mathias of Maryland and Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania) supported the House version (see Table 1). With committee Chairman Strom Thurmond firmly against the House bill, a 9–9 tie in the committee would result in the legislation failing. Initially, Reagan administration skeptics assumed that a conservative majority could be built in the committee (i.e., the eight Republicans who hadn't co-sponsored the House bill, plus Hefflin) for a watered-down or clean extension. In early 1982, a White House briefing paper about the Senate Judiciary Committee predicted that “the [Republican Senate] Majority's goal will be to … preclude adoption of the ‘effects’ test in Section II which was passed in the House.”Footnote 40

Table 1. Senate Judiciary Committee Sponsors of the House Version of the VRA extension1

1 Memorandum from Sherrie Cooksey to Ken Duberstein, Status of Voting Rights Act Legislation in the Senate, January 6, 1982, Reagan Presidential Library.

At this point Senator Dole assumed an important role in breaking the impasse. Dole sat on the Judiciary Committee, and unlike other committee members, he had been publicly coy about his views on the bill. In May 1982, Dole and four other senators (Ted Kennedy, Chuck Grassley, Dennis DeConcini, and Charles Mathias) announced that they had forged a compromise to navigate the bill through the committee.Footnote 41 The Dole compromise included three changes to the House bill (see Figure 1).Footnote 42 First, it preserved the House's amended Section 2, which overturned Bolden by specifying a “results test.” Using the language of the 1973 Supreme Court case White v Regester, the amendment specified that a litigant could prove voting rights violations “if, based on the totality of circumstances, it is shown that the political process[es] leading to nomination or election in the state or political subdivision are not equally open to participation” by racial minorities. In other words, litigants did not need to show that the electoral rules were intentionally designed to discriminate against minorities for the rules to be found discriminatory in practice.

Fig. 1. The Three Elements of the Dole Compromise, Written by Dole or a Member of Staff.

Source: Voting Rights, April 1982–September 1983, Robert J. Dole Senate Papers—Press Related Materials, series 8: subject files, 1961–1996, box 58, folder 7, Dole Archives, University of Kansas

Second, the Dole compromise clarified that an effects standard could not be used by the courts as a basis for requiring proportional representation, but this was never a serious concern. Third, the compromise extended Section 5 preclearance for twenty-five years, rather than permanently as the House bill had specified. This was still a longer period than specified under the original bill, in its previous extensions, or by the ten-year extension proposed by the DOJ. The House bill otherwise remained largely intact.Footnote 43 From the perspective of civil rights leaders, the modifications made by Dole were substantively minor but politically critical.

The Dole compromise received support from all of the Democrats on the committee, as well as from six Republicans. Four Republicans voted against it (see Table 2). Dole's role as the face of the compromise provided crucial cover to some wavering Republicans. Iowa Senator Chuck Grassley, for example, had for weeks been under “heavy pressure” from administration skeptics and conservatives on the committee to oppose an effects-based standard.Footnote 44 The president's assistant for legislative affairs, Ken Duberstein, had called Grassley in March 1982, “to reiterate … the President's commitment to oppose the inclusion of an effects test for §2 at all stages of Senate consideration.”Footnote 45 Grassley sensed that opinion was divided within the administration (more on this later) and replied that he was “concerned about the President's full commitment to fighting all the way for retaining the intents test.”Footnote 46 Dole's imprimatur gave permission for conservatives to support the House's liberal bill. Senator Joe Biden, the committee's ranking member, believed that it was vital “to have someone who had good conservative credentials … Dole gives someone like Sen Grassley legitimacy with his constituency.”Footnote 47

Table 2. Roll call vote, Dole Compromise, Senate Judiciary Committee, 3 May 1982

The compromise enabled the VRA to sail through the Senate Judiciary Committee. After its adoption, the bill was sent to the Senate floor with a recommendation of 17–1. Orrin Hatch provided the one dissenting vote. Hatch represented Utah, a state that was overwhelmingly white (95 percent) and whose African American population was a mere 0.7 percent.Footnote 48 The other Republican opponents of the Dole compromise represented southern states whose black populations were 26 percent (Alabama), 22 percent (North Carolina), and 30 percent (South Carolina). After losing the vote on the amendment, they fell into line to support the amended law.

The bill went on to receive overwhelming support in the Senate, even from Senator Thurmond. Only eight senators voted against the extension. These margins speak to the symbolic power of the memory of the act, which was still widely popular. After the Senate passed the Dole-compromised legislation, the House approved the Senate version, and Dole urged, “I hope the President will act quickly in signing this historic legislation into law.”Footnote 49 President Ronald Reagan signed the extension into law on June 29, 1982, with a smiling Dole standing behind him.

Many close observers of the Dole compromise realized that it was not much of a compromise at all. The Wall Street Journal explained, “the changes aren't very substantive.”Footnote 50 While Dole insisted that his language against proportional representation was a major concession, Democratic supporters of the bill did not think that such a clarification was necessary anyway. According to Giovanni Capoccia, in critical junctures “political actors seek to create and diffuse legitimacy for new institutional arrangements.”Footnote 51 Dole tried to legitimate Republican support for an effects-based standard through this anti-proportional representation language. Dole's attempt to shift the ideational terrain was only partially successful. Dole was criticized by conservative writers for “choosing to make his bed with the liberals and with virtual authority over any compromise in the Leadership Conference [on Civil Rights].”Footnote 52 Alan Ryskind mocked Dole for sprinkling “more than a pinch of incense on the altar of the Civil Rights Lobby.”Footnote 53

One of the most vocal supporters of the Dole compromise was civil rights lawyer Joseph Rauh, who told the Washington Post, “It was no compromise at all. We got everything we wanted.” Rauh, counsel for the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, likened Dole to “the Dirksen of the 80s.”Footnote 54 “He was superb,” Rauh remarked, “He got us the perfect bill. We couldn't have done it without him.”Footnote 55 In a private memorandum, Dole's advisor Sheila Bair apologized to an embarrassed Dole for Rauh's garrulity, “In fairness to Mr. Rauh, he was just trying to make you look good. As the article indicates, he is ‘high’ on you, and thought that by saying there really wasn't a compromise, he would enhance your already high popularity with civil rights groups.”Footnote 56

3. The 1982 Voting Rights Act Extension as a Critical Juncture

American political development (APD) scholars agree that critical junctures are periods when the possibilities for change open up, and the changes that are made at these junctures have durable, path-dependent effects.Footnote 57 According to Capoccia, critical junctures refer to “situations of uncertainty in which decisions of important actors are causally decisive for the selection of one path of institutional development over other possible paths.”Footnote 58

Capoccia defines institutions broadly to encompass “organizations, formal rules, public policies … political regimes and political economies.” As the most critical piece of U.S. civil rights infrastructure and the sine qua non of late twentieth century U.S. democratization, the VRA constitutes a kind of institution with its own history of development.Footnote 59 This understanding of the VRA as an institution (in Capoccia's sense) is consistent with the work of other historical institutionalists, such as Thomas Ertman's application of critical junctures to the study of the British Reform Acts of 1832, 1867, 1884, and 1918.Footnote 60

In the development of an institution, there will be junctures of uncertainty. These stages of uncertainty may even be inherent in the institutional setup. This is true in the case of the VRA, whose temporary measures, such as Section 5 preclearance, required the law to be extended multiple times (1970, 1975, 1982, and 2006). Each of these extensions shaped the character of the law in important path-dependent ways, such as including provisions to protect non-English speakers in 1975, which had never been part of the original law. This built a constituency for the VRA among Hispanics, which became relevant in the Reagan administration's political calculus in 1982. As Capoccia explains, during a critical juncture, “agents face a broader than normal range of feasible options.” One option is chosen “as a consequence of political interactions and decision-making, and this initial selection carries a long lasting institutional legacy. In this process, actors have real choices and the institutional outcome, albeit constrained by antecedent conditions and the range of politically feasible outcomes, is not predetermined by such conditions.”Footnote 61

In 1981–82, the future of the VRA was genuinely uncertain. There were multiple different paths that the policy could have taken, as Table 3 shows. It is fair to say that Bob Dole and the Reagan administration faced a range of possible choices in the nine months between August 1981 and May 1982—from inaction to a clean renewal to embracing the House bill. Some of these choices were better enforced by antecedent conditions than others, but it was the choices of political agents that ultimately determined the VRA's developmental path.Footnote 62 Thernstrom, for example, argues that “the strength of the [House] bill made it vulnerable to attack. Neither the administration nor Senate conservatives would have dared to oppose moderate legislation, but this bill might invite and legitimize opposition.”Footnote 63 The House bill was no fait accompli.

Table 3. Voting Rights Extension Options in Early 1982

The concept of critical junctures brings attention to political agency and choice. As Capoccia and Daniel Kelemen put it, they are “relatively short periods of time during which there is a substantially heightened probability that agents’ choices will affect the outcome of interest.”Footnote 64 In his article on the British Reform Acts, Ertman disagrees with those who simply saw reform as an inevitable consequence of a long and continuous build-up in pressure. Instead, Ertman underscores “the central significance of personal choices made by [prime ministers] Peel and Wellington.”Footnote 65 Ertman correctly surmises that a critical juncture occurs “over a relatively short period of time as a result of decisions of a small number of actors.”Footnote 66

According to Adam Sheingate, political entrepreneurs are “individuals whose creative acts have transformative effects on politics, policies or institutions.”Footnote 67 Political entrepreneurs “exploit uncertainty” during critical junctures “to engage in speculative acts of creativity.”Footnote 68 Robert Dahl described a political entrepreneur as “a leader who knows how to use his resources to the maximum.”Footnote 69 Dole knew that he could build a coalition for a strengthened VRA in the Senate Judiciary Committee that would be, in effect, the Democratic bill but characterized as a compromise that would be palpable to all but the most conservative Republicans. He exploited divisions within the Reagan administration over the bill's content to his advantage, aided by his wife, Elizabeth Dole, an administration official who coordinated the pro–House bill faction in conjunction with supportive aides within the White House. As Sheingate writes, political entrepreneurs are “creative, resourceful, and opportunistic leaders” who engage in a “skillful manipulation of politics.”Footnote 70

In this way, the 1982 extension debate represents a critical juncture in the historical development of the VRA, and Bob Dole is the relevant political entrepreneur whose compromise constituted a speculative act of creativity. The following section explains Dole's motivations for his political entrepreneurship, which help to clarify the antecedent conditions for this choice.

3.1 Political Entrepreneurship at a Critical Juncture: Bringing Dole Back In

While a number of scholars have acknowledged that Senator Dole was a key player in ensuring that the VRA extension was ultimately successful, no study has taken seriously the role of Dole as a political entrepreneur whose strategic calculations led the VRA down a particular developmental path that it might not otherwise have followed. This oversight is because Dole's motivations have been poorly understood. By not understanding why Dole acted as he did, it is easy for scholars to imply that the form that the Dole compromise took was predetermined. It is difficult to know exactly why Dole championed the effects standard. His archival records provide ample evidence for likely motivations but no smoking gun. However, the weight of the evidence suggests that Dole wanted to be seen as the savior of the VRA for two main reasons: (1) a continuation of party-building efforts and minority outreach that Dole began in the 1970s and (2) career ambition. As Ruth Berins Collier and David Collier have expressed, there is a range of choice at each juncture from “considerable discretion” to the choice being “deeply embedded in the antecedent conditions.”Footnote 71 I argue that there were antecedent conditions that helped to shape the decision Dole took, but his decision was not preordained.

3.1.1 Party-Building

From the 1930s to 1960s, the Republican Party realigned on race, but in the 1970s not all Republican elites were ready to abandon the black electorate to Democrats. Some senior officials, Bob Dole among them, recognized that there was a significant conservative segment among the black electorate.Footnote 72 Even Richard Nixon speculated that there were “probably 30% [of African Americans] who are potentially on our side.” He suggested they consisted of “Negro businessmen, bankers, Elks, etc.”Footnote 73 Senior Republicans hypothesized that GOP outreach efforts could draw a nontrivial minority of African Americans back into the party fold.Footnote 74

Bob Dole served as Republican National Committee (RNC) chair during 1971–73 and was a part of these outreach efforts. As party chair, he appointed African Americans to key positions, including Dr. Henry Lucas to the executive committee of the RNC and chairman of the National Black Republican Council (NBRC). Dole extolled, “Recent years have seen tremendous growth of support for the GOP among minority voters. The appointment of Dr. Lucas is at once a recognition of that fact and an effort to solicit the needed advice and counsel that will help us build on it.”Footnote 75 In a letter to his fellow RNC members, Lucas described, “A principle objective of the NBRC is to serve as an ‘outreach’ mechanism (for attracting blacks).”Footnote 76 An initial $40,000 was given to Lucas to build connections with conservative black leaders around the country, such as sponsoring conferences for black Republicans.Footnote 77 It mirrored a similar effort funded by the Republican Congressional Campaign Committee, known as the “Black Silent Majority Committee.”Footnote 78

This party-building work continued after Dole stood down as RNC chair. The RNC invested over $2 million for black outreach during the Carter presidency. The RNC hired the black political consultancy firm Wright-McNeill and Associates for advice on appealing to the black electorate. The firm advised, “the Black vote can be obtained by many Republican[s], if more than a token effort is aimed at the black community.”Footnote 79 Dole wrote to Wright-McNeill and “applauded the black consultants’ role within the party.”Footnote 80 Dole's advisors encouraged the senator's outreach efforts. Key confidante Sheila Bair wrote in a private memo to Dole, “Many blacks may be receptive to the Republican party if Republicans can find a way to show they want black voters.”Footnote 81 In 1980, Dole was commended by Trans-Urban News for his black outreach efforts.Footnote 82 When Dole was Senate Majority Leader, Sheila Bair and Reagan advisor Thelma Duggin worked together to set up a “Black Republican advisory group to the Senate Leadership.”Footnote 83

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Republican Party funded various conferences and workshops to explore building inroads into the black community. At one such event in 1978, Jesse Jackson told RNC officials, “Black people need the Republican Party to compete for us so that we have real alternatives to meeting our needs.”Footnote 84 Another event in December 1980 at the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco attracted national attention, especially in the black press, and was attended by unlikely guests including Stokely Carmichael's co-author of Black Power, the Columbia political scientist Charles V. Hamilton, and the critical race theorist and Harvard professor Derrick Bell.Footnote 85

In the 1980 election, some of these party-building efforts paid off. A number of civil rights leaders endorsed Ronald Reagan, including Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver, Ralph Abernathy, Hosea Williams (who said, “Ain't no way in the world brother Reagan could do worse” than Jimmy Carter), Charles Evers, James Bevel, and James Meredith.Footnote 86 Some white Republicans commanded respectable levels of support from black voters in the 1980s: Republican Don Nickles won 40 percent of the black vote in the 1980 Oklahoma Senate election.Footnote 87 Republican Mack Mattingly won a similar share in the Georgia Senate race that year. In 1985, Coretta Scott King called New Jersey Governor Thomas Kean “a contemporary Republican in the tradition of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass” and called on “decent and concerned New Jerseyans—especially blacks and Hispanics—[to] say ‘thank you’ at the polls.”Footnote 88 He won 60 percent of the black vote.Footnote 89 These statistics somewhat complicate the view that African Americans were a lost electorate to Republicans, even in the Reagan era.

In 1982, Dole specifically cited party-building as a key benefit of the VRA extension. Dole said at the time, “I think Republicans should get out of the back row on things like this … especially if we want to be a bigger party.”Footnote 90 Dole posited, “I believe that black voters hold one of the keys to our becoming—and remaining—the majority party at all levels of government.”Footnote 91 In his home state of Kansas, Dole saw the importance of cultivating the support of African American voters. Soon after the Dole compromise was reached, the senator's press team leaped into action distributing newspaper packets of positive press clippings. One person tasked with this role was John Palmer, an African American field representative in Dole's Kansas City office. One internal memorandum to Dole on May 4, 1982, reads, “Palmer will direct the packet to key members along with mail-outs to 3,000 black Kansans.” The words, “also Wichita ministers,” were handwritten in blue pen on the top of the memo, suggesting that the cuttings would also be sent to African American clergy (see Figure 2).Footnote 92

Fig. 2. Memo to Bob Dole from Walt Riker, Voting Rights Act Media (May 4, 1982).

Source: Voting Rights, April 1982–September 1983, series 8: subject files, 1961–1996, box 58, folder 7, Dole Archives, University of Kansas.

For his role in the VRA extension, Dole was praised by black elites in Kansas. Leroy Tombs, a black businessman from Bonner Springs, Kansas, told a newspaper, “You can't find anyone today who has done more beneficial things for blacks than Bob Dole. Without his help, the Voting Rights Extension Act wouldn't have passed. He picked it up when it was almost dead.” The quote was circled with arrows by a member of Dole's office (or possibly Dole himself), with the instruction to his press secretary, “Walt [Riker], get original and save.”Footnote 93

Dole's efforts to attract African American support, as both RNC chair and a leading Senate Republican, belie Thernstrom's assertion that “up to that point [of the Dole Compromise], the Kansas Republican has shown little interest in the [civil rights] issue.”Footnote 94 Dole's actions demonstrate a desire to shift the “party image” on civil rights.Footnote 95 As Tatishe Nteta and Brian Schaffner have shown, both parties have tried to make symbolic appeals to minority voters through policy realignment.Footnote 96 Dole's actions were more proactive than Rhodes's suggestion that Republicans' support for the VRA extension was for defensive purposes of “party-brand maintenance” because “the norm of racial equality was ascendant” and the party was worried about losing “potentially pivotal moderate white voters” in the 1982 midterms.Footnote 97 While this concern was certainly present, for some Republican Party entrepreneurs, including Dole, support for the extension was a much more enterprising exercise in party expansion.

Dole even used the VRA extension, passed with bipartisan support, as a way of attacking the Democrats for being weak on civil rights. He told a black Republican group, the Council of 100, that he “bristle[d] at the pretense that the other party somehow has an exclusive claim on civil rights. Under the leadership of a Republican president, a Republican controlled Senate passed a twenty-five-year extension of the Voting Rights Act—three times longer than any of the previous extensions passed while the Democrats were in control.”Footnote 98 Tasha Philpot has argued that parties have “long-standing reputations for handling certain issues.”Footnote 99 Dole tried to shift the GOP's reputation on voting rights, and the 1982 extension was, in many ways, the peak of his party-building efforts.

3.1.2 Career Ambitions

The other part of the explanation of Dole's role in the VRA extension emerges from understanding Dole's career ambitions. Dole, who by 1982 had already been Republican Party chairman and a vice presidential nominee, wanted to assume leadership in the Senate and then be elected president. Being credited with forging a compromise to save an iconic piece of civil rights law would bolster Dole's credentials as a bipartisan deal maker, a pragmatist, and a humanitarian. This behavior is consistent with theories of critical juncture. Capoccia explains that at critical junctures, “influential actors … seek to take advantage of a fluid and uncertain situation” whereby they “promote, diffuse, and entrench certain ideas in the public sphere, ideas which both define the crisis and provide an institutional recipe to ‘solve’ it.”Footnote 100

By reputation, Dole was regarded as a pragmatic, “Gerald Ford-style Midwestern stalwart.”Footnote 101 The fact that Dole could secure a compromise on the VRA served to bolster his reputation as a deal broker. As one journalist put it, “If ever Senator Dole displayed statesman-like stature, it was in his handling of the VRA.”Footnote 102 Such a reputation may have been politically beneficial, especially given that he would succeed Senator Howard Baker, known as “the Great Conciliator,” as Republican leader in the Senate two years later. By taking such a prominent role on voting rights, Dole enamored himself to some moderates and liberals in the Senate Republican caucus, while retaining the support of more conservative stalwarts, who were more concerned about other civil rights measures on busing and housing. When Dole sought the Senate Republican leadership in 1984, he won after four ballots on a narrow 28–25 vote. Rae describes Dole's election as a victory of “an alliance of liberals and stalwarts” in the party.Footnote 103 While some conservatives balked at the Dole compromise, it enhanced his reputation within the Senate Republican caucus overall. Congressional party leaders in the 1980s were expected to be skilled negotiators and dealmakers. Unified Republican control had not occurred since 1955 and would not again occur until 2001. Therefore, Republican congressional leaders, in particular, were expected to be skilled at working with Democrats in order to secure any gains for Republican causes in an era where they could always expect to be in the minority, as Frances Lee has explained.Footnote 104

Additionally, given Dole's presidential aspirations, being associated with this “victory” could boost his national profile and broaden his appeal. Soon after the Dole compromise was reached, a conservative weekly divined, “Dole is running for president.”Footnote 105 The conservative Human Events chided that Dole “has apparently felt that his presidential ambitions required compliance with the most extreme demands of the civil rights community.”Footnote 106 Dole's photo appeared on the front page of the New York Times on May 4, 1982, lauding his efforts on the VRA. Dole received positive press attention for years following the VRA extension. Thernstrom attributes the Dole compromise to pure ambition, writing, “Dole's presidential aspirations were no secret.”Footnote 107

As the decade wore on, Dole continued to trumpet his role in securing the extension of the VRA. Dole's support was used as a means of softening his image with white independents and moderate voters. At an event in Manchester, New Hampshire, a key primary state with few black voters, Dole trumpeted, “we extended and strengthened the Voting Rights Act, which has been so instrumental in striking down legal barriers to the process which disenfranchised blacks and other minorities.”Footnote 108 In a March 1987 radio debate with Ted Kennedy, Dole credited himself as “one of the authors of the 1982 legislation that saved the Voting Rights Act.”Footnote 109

In a 1987 article speculating about Dole's presidential prospects, the Topeka Capital-Journal cited the fact that Dole had “fought the Reagan administration to save the Voting Rights Act” as one of the reasons why Dole was considered “the Democrats’ favorite Republican.”Footnote 110 A 1985 internal memo from advisor Sheila Bair to Dole remarked that the senator's association with the VRA “could prove useful in 1988.”Footnote 111 When Dole finally ran for president in 1996, he continued to tout his role in the VRA extension. A list of civil rights achievements circulated by his campaign includes, “Dole was instrumental in extending the Voting Rights Act in 1982.”Footnote 112 In 1982, Dole had his eyes set on a “national constituency.” The VRA—and voting rights more vaguely conceived—was popular in the national public and, crucially, among white moderates and influential figures in the media.

Sheingate writes that political entrepreneurs are a source of political innovation because they bring forward new ideas by “brokering and coalition building” to “succeed in building the requisite support to get new policies adopted.”Footnote 113 In practice, however, as John Kingdon has written, the innovation by policy entrepreneurs “usually involves recombination of old elements more than fresh invention of new ones.… [C]hange turns out to be recombination rather than mutation.”Footnote 114 The Dole compromise broke an impasse in the VRA's policy development, but it was in effect a rehashing of the Democrats’ bill. Dole's skill was to build a wider coalition for the Democratic House bill than it could have otherwise achieved on the Senate Judiciary Committee, providing political cover for some Senate conservatives and the Reagan administration.

4. The Reagan Administration: “Real Differences Internally”

In the week after the Dole compromise was announced, journalist Mary McGrory wrote, “Once the White House realized Dole had the votes, the president rushed forward to embrace the compromise.”Footnote 115 Yet, as Nicol Rae writes, the bill that Dole eventually achieved “ran counter to the earlier position of the Reagan Administration.”Footnote 116 It was also contrary to what some administration officials, including the attorney general, had said in earlier stages of the legislative process would be acceptable. Jesse Rhodes attributes this acquiescence to the administration's desire to avoid electoral sanction for being visibly opposed to the VRA, while believing that the VRA could be dismantled behind the scenes through the administrative state and the federal judiciary.

There are a few reasons why Rhodes's account is not wholly satisfying. First, it does not explain why Reagan initially was vocal in his opposition to preclearance and the effects-based standard. If Reagan thought it was bad politics to question the VRA, why did he do so shortly after his election? Similarly, why did DOJ officials go on the record opposing these elements of the act, including at congressional hearings, through the spring of 1982? What is missing from Rhodes's account, I argue, is an appreciation of the range of opinions voiced within the administration. Opposition to an effects-based standard was strongest in the DOJ, whereas White House officials showed more willingness to compromise on the issue. I identify three motives for accepting the Dole compromise: (1) an effort at party-building, (2) genuine support, (3) the recognition that the VRA could provide cover for the president to pursue more conservative positions on other racial policies, such as busing and affirmative action. Bob Dole, in co-ordination with his wife Elizabeth Dole, the White House director of the Office of Public Liaison, was able to marshal this discordance to his advantage to push through a more robust extension package than some administration figures would have liked.

4.1 Lobbying the Reagan Administration

The Reagan administration was divided over the VRA extension. Writing during the Reagan years, Thernstrom speculated that there was divide between the DOJ (who wanted to water down the House bill significantly) and the White House staff (who largely did not, with some exceptions).Footnote 117 Archival records now reveal that Thernstrom's intuition was correct. The DOJ and the White House spent a year (from spring 1981 to spring 1982) arguing internally about what kind of extension the president should support.

Perhaps sensing this internal ambiguity, from the summer of 1981 senior Republican figures attempted to lobby White House advisors. Elizabeth Dole was sent a packet of newspaper clippings about the VRA from Edward Brooke, who argued passionately for strengthening and extending the law. Brooke had endorsed Reagan in the 1980 election, in spite of his reservations about Reagan's conservatism, after Reagan had assured Brooke that he would safeguard civil rights and take action to reduce discrimination in public housing.Footnote 118 After the extension passed into law, Elizabeth Dole recommended inviting Brooke to the signing ceremony.Footnote 119

Other White House officials were lobbied by conservative opponents of the VRA. Strom Thurmond sent articles and missives critical of the VRA, beginning in the summer of 1981, to White House officials. For example, Thurmond sent White House Counsel Ed Meese articles that declared “Voting Rights Law Has Met Its Goals.”Footnote 120 Meese was clearly seen as a more sympathetic ear by VRA skeptics than Elizabeth Dole. Senator Brooke saw Meese as a foe and stated in an interview with me, “I never got along with him.”Footnote 121 In one of the articles that Thurmond sent Meese, the final sentence was underlined: “Ideally, Congress should let the act die and leave to the courts the task of dealing with discriminatory situations.”Footnote 122 It is unclear whether Thurmond or Meese underlined the sentence. Additionally, Thurmond sent a lengthy dissertation written by former segregationist Senator Sam Ervin to President Reagan's Chief of Staff James Baker.Footnote 123 The dissertation, entitled The Truth Respecting the Highly Praised and Constitutionally Devious Voting Rights Act, described the VRA as “repugnant to the system of government the Constitution was ordained to establish.”Footnote 124 Baker thanked Thurmond for sending the polemic, writing, “I have packed this dissertation in my briefcase and will look forward to reading it more thoroughly once I get settled in Texas.”Footnote 125

The president's own view is somewhat detached from the correspondences among his White House staff and the DOJ. His personal views are not discussed in the policy development papers. This aloofness from the technicalities of the policy is consistent with scholarship on the Reagan presidency in other policy areas. According to his biographer Lou Cannon, Reagan professed an instinctive preference for “cabinet government.”Footnote 126 Reagan held the view that government was analogous to a business and that the president served as chair of the board. Thus, once having set out a broad policy vision, Reagan was comfortable with details being worked out by his close advisors. Reagan was asked in an interview with Fortune magazine about how much decision making he felt he should leave to his subordinates. Reagan explained, “I believe that you surround yourself with the best people you can find, delegate authority, and don't interfere as long as the overall policy that you've decided upon is being carried out.”Footnote 127

In keeping with this approach, Reagan ordered the DOJ in June 1981 to make a comprehensive review of the VRA, perhaps knowing that the key players in the department shared his skepticism about several elements of the act. A September 1981 draft of the review showed that the DOJ would propose a 10-year, clean extension of the VRA. Drawing a clear distinction from the House version of the bill, Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights Bradford Reynolds wrote, “We are opposed to including in the Administration proposal any amendment of Section 2 that suggests the incorporation of an ‘effects’ test.”Footnote 128 In other words, the administration would concede to the continuance of Section 5 preclearance for a decade, but it would not overturn the Bolden intent standard for Section 2. President Reagan formally aligned himself with this position in November 1981.

The DOJ's position was intended to be a kind of compromise, saving Section 5 (for a decade) but resisting efforts to strengthen Section 2. This appears to have been the line of least resistance, and one that the administration felt could command a majority view in the Judiciary Committee. Michael Uhlmann from the White House Office of Policy Development recommended to Meese in October 1981, “As a practical political matter, I think we have to accept whatever it is that Senators Thurmond and [Howard] Baker can agree on.”Footnote 129

However, for some conservatives on the committee, accepting Section 5 for even a decade more was a bridge too far. A November 1981 memo from Meese's aide Mitchell Stanley to White House Counsellor Edwin Thomas reveals the mounting pressure. Stanley writes that he received a phone call from a friend of conservative Senator Jesse Helms “who indicated that the Senator was furious about the Administration's position.” Stanley adds, “The same holds true for Sen. Thurmond and East.”Footnote 130

Sensing that conservatives would be unhappy with the president's support for extending Section 5, Reagan advisor Red Cavaney suggested that the president emphasize his opposition to the effects test in Section 2. Cavaney also proposed that the White House should seek “statements from one or two Senate GOP leaders applauding the President … and stating that they find the House ‘effects tests’ full of loopholes and will press to see these are corrected more in line with ‘intents’.”Footnote 131 Consistent with this advice, Reagan stated in an October 18, 1981, interview that while he had changed his mind about opposing the extension of the Section 5 preclearance, he thought that the version of the bill “the House is working on … has maybe been pretty extreme in what it's done. I'm hopeful that the Senate is going to be more reasonable.”Footnote 132

Thernstrom contends that conservatives were “asleep at the switch” over the Section 2 changes and that the Reagan administration was “no help” to skeptics of the effects standard, but this doesn't stack up.Footnote 133 Internal documents show that the Reagan DOJ continued to advocate for the weaker Section 2 provisions throughout early 1982. A January 1982 DOJ briefing document clarified, “We support retaining the intent test in §2.… We fully agree with Justice Stewart's opinion in Mobile v. Bolden … that proof of discriminatory purpose was necessary to establish a violation of the Fifteenth Amendment.” The document went on to say, “we do not think an effects test makes any sense.”Footnote 134 In this vein, Bradford Reynolds testified to Congress that “the ‘effects’ test in amended Section 2 would mandate … wholesale governmental restructuring … and thus lead in the undesired direction of a re-polarization of society among racial lines.” Reynolds told Congress, “If it is not broken, don't fix it.… The Administration is in full agreement with that position.”Footnote 135 He reiterated his position in a letter to the Washington Post on February 11, 1982, stating, “Section 2 therefore should be retained without change.”Footnote 136 Reagan's deputy assistant for legislative affairs Ken Dubertsein observed, perhaps with a touch of weariness, that “the Justice Department is continuing to ‘educate’ Senators on the problems with the ‘effects test’.”Footnote 137

In March 1982, the DOJ was still maintaining its opposition to the effects-based standard. Deputy Attorney General Edward Schmults sent a memo to Ed Meese with the title, “Why Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act should be retained unchanged.” Schmults's note described the House version as “unacceptable.” The note expressed the view that “violations of §2 should not be made too easy to prove, since they provide a basis for the most intrusive interference imaginable by federal courts into state and local processes.”Footnote 138 As late as April 16, 1982, the assistant attorney general for legislative affairs, Robert McConnell, wrote to senators lobbying them to oppose an effects-based standard for Section 2.Footnote 139

Just one week later, on April 25, 1982, Senator Dole sent White House officials his proposed compromise. The following day, Reagan's advisors met to discuss their legislative strategy. On the agenda were these questions:

• If we will need to compromise, is it best to do so now in committee, or wait to do so on the floor?

• If we decide to compromise, how should this be done? Should Dole or someone else (perhaps even bipartisan sponsors) introduce an amendment, and we then support?

• Or perhaps should the President himself attempt to put himself above the fray, and, by letter, call on both sides to find a middle ground … with such a call followed by the introduction of a compromise?Footnote 140

At the meeting, DOJ officials argued against the Dole compromise. They described it as “inferior” and warned “that it would not be supported by conservatives on the committee.” Instead, they proposed a minimal revision of Section 2, which would keep the intent-based standard in place. Known as the Reynolds amendment, the proposal “maintains the intent language of current law and adds a subsection that modifies the Mobile standard by using language from White v Regester.” The DOJ reported, “Politically, we think the [Reynolds] compromise will be attractive.”Footnote 141 However, the White House was more skeptical. James Cicconi, special assistant to Chief of Staff James Baker, noted that this position would not be supported by “the civil rights coalition.” He added, “If it is to succeed it must be supported by Heflin and Dole (and, through them, DeConcini) while maintaining conservative support.”Footnote 142

Reagan's advisors met one week later, on May 3, 1982, to decide on a final strategy, which took place three hours before Dole, Mathias, and Kennedy were going to hold a press conference announcing the compromise. It is clear, then, that either or both Heflin and Dole did not support the Reynolds amendment earlier in the week, rendering it untenable. At the meeting, the attorney general listed a range of options:

1. Do nothing

2. Endorse the entire compromise [including the 25-year Section 5 extension]

3. Approve §2 of Compromise

4. As #3, but express hope for compromise on bailout, also

The political discussion was offered by Elizabeth Dole, Ed Rollins, and Melvin Bradley. Bradley, who was an African American, had been appointed only two weeks earlier as special assistant to the president on “urban affairs.”Footnote 143 In addition, Richard Darman advocated that the president endorse the Dole compromise “enthusiastically” in hopes that he would bring a “quick conclusion” to this debate.Footnote 144 Darman's position is significant because it was a substantial change from his earlier opposition to the effects-based standard. In the end, the decision was taken to endorse the entire compromise, as described in the meeting notes.

4.2 The “Recalcitrant” Race-Conscious Republicans

So why did the Reagan administration change its view on Section 2 and agree to a longer extension of Section 5? Had Bob Dole simply boxed them in? As Attorney General William French Smith's notes indicate, the administration perceived itself to have four options. The decision to “endorse the entire compromise” was ultimately not driven by DOJ officials who had taken a consistently conservative line. Instead, supportive White House staff, singled out as “recalcitrants” by the right-wing media, had laid the groundwork for the House bill's provisions for months. Their arguments were based on principled and strategic considerations.

Viewpoints within the White House itself were divided. In correspondence with me, White House official James Cicconi recalled, “There were real differences internally. We had some harder-line conservatives who argued for a line in the sand. Many others … felt a polarized political fight over a civil rights issue was unwise and unneeded” (Correspondence with James Cicconi, September 5, 2018). A contemporary conservative commentator blamed “recalcitrant elements in the White House who were preoccupied with the civil rights image of the White House.”Footnote 145 Chief among these actors were Mel Bradley, Elizabeth Dole, and Thelma Duggin. The latter two advisors, especially, helped to prepare the ground for the administration's final embrace of the Dole compromise in May 1982.

Mel Bradley had been an informal advisor to Reagan in the first year of his presidency, and in the second year, he was made a formal advisor on civil rights and urban affairs. By the winter of 1981 Bradley was one of the figures in the administration who advised the president to abandon his insistence on an intent-based standard. Bradley wrote to Reagan's chief policy advisor Martin Anderson that the president ought to “support H.R. 3112 [the House bill] without qualifications” because the VRA was “an impassioned, symbolic issue” and that it would “demonstrate[] commitment to be President of all the people [and] improve[] status in minority community.”Footnote 146

Thelma Duggin's role has not been given sufficient attention. The only black female advisor to President Reagan, Duggin operated as an informal link between the White House and African American communities. As early as May 12, 1981, Duggin met with civil rights lobbyists to sound out their opinions on the extension.Footnote 147 In June 1981, Duggin wrote a passionate defense of the VRA for her boss Elizabeth Dole from the “perspective of blacks who feel that the Voting Rights Act is the most significant piece of civil rights legislation ever enacted.”Footnote 148 Duggin insisted in her briefing to Mrs. Dole that “a great deal of discrimination still exists.” She argued that “100 years of litigation under the 14th and 15th Amendment had proven to be ineffective,” and she insisted that the “burden of proof of discrimination” must not be put “on the plaintiff (usually the victim of discrimination).”Footnote 149 She warned, “The Black Community's perception is: We had to fight hard to get the right to vote. Ronald Reagan was elected and he wants to take away our right to vote.”Footnote 150

Throughout the debate in 1981–82, Duggin maintained that the White House needed to embrace the House version of the VRA. Anything less would be inadequate. Duggin reportedly clashed with Morton Blackwell, a long-standing VRA opponent, over the issue.Footnote 151 In a January 1982 response to draft DOJ testimony that was critical of the effects-based standard, Duggin wrote, “This testimony would have been great six months ago, but now it can be assumed that it will be greeted negatively by civil rights organizations.” Duggin was adamant, “Anything short of an endorsement of the House bill by the president will be viewed as watering-down the legislation.” Duggin pushed back against officials who argued that VRA was a violation of states’ rights. She annotated, “The statement about federalism at the bottom of page 6 will turn off blacks. If states were living up to their responsibilities, we would not have to pass the VRA in the first place.” Duggin's response is characteristic of race-conscious black Republicans, whom Corey Fields argues have a “structural analysis” of racial inequality in America. In Fields's summary, they view the black community as “a respectable community constrained by racism.”Footnote 152

Duggin was also aware of the political ramifications of not being seen to champion the VRA. In July 1981, she highlighted a Chicago Tribune article that argued that the Republicans had lost a special election in Mississippi because Democrats mobilized black voters against the Republicans’ perceived disdain for the VRA. Duggin had predicted a month earlier that the VRA “will act as a focal rallying point for blacks, not only against the Reagan Administration but also against the Republican Party.”Footnote 153 Duggin had been involved in the party-building efforts by the RNC in 1970s to reach out to black voters, working as a field analyst for Wright-McNeill and Associates. In this capacity, she monitored Republican candidates’ programs for anti-black content. In response to Texas congressman Ron Paul's platform, she wrote, “His positions on the welfare system, minimum wage, and health care were too far to the right to offer the type of sensitivity Black voters were looking for.”Footnote 154

Duggin worked under Elizabeth Dole, who played an even more decisive role in pushing the president to accept the effects standard. Mrs. Dole worked as the public liaison and was the president's advisor on women and minority groups.Footnote 155 Mrs. Dole had been involved closely since the debates over the act began in the White House in the spring of 1981. In October 1981, she sent a memorandum to White House staff secretary Richard Darman suggesting that the president abandon the conservative recommendations of the DOJ on the VRA extension.Footnote 156 Mrs. Dole suggested that the president, instead, wait to embrace whatever version the Senate passed, which she expected would be “similar” to the House bill. Elizabeth Dole's November prediction proved more accurate than any other advice received by the president during this time. In the spring of 1982, Mrs. Dole was the key conduit between Senator Dole and President Reagan. Senator Dole acknowledged publicly that Mrs. Dole “was working pretty hard on this.”Footnote 157

4.3 Party-Builders

John Skrenty argues that even after Goldwater, “A [Republican] candidate could not completely repudiate civil rights and still be taken seriously.” Even in the 1980s, there was “great political risk” in “challenging the civil rights tradition.”Footnote 158 It is correct, as Rhodes and others have done, to argue that the Reagan White House was concerned that there could be a backlash against the president for being seen to be against the VRA.

A November 1981 strategy document set out clearly, “The administration (and the GOP) want to avoid the political accusation that we seek to ‘weaken’ the Voting Rights Act.”Footnote 159 The popularity of the legislation, if not its details, meant that it was politically difficult for the White House to oppose extending the VRA outright. Senior Reagan officials (Baker, Meese, and Michael Deaver) received a report from the polling firm Intelligent Alternatives that found “there does not appear to be any ‘mandate’ from the South to eliminate the temporary provisions of the Voting Rights Act.” The firm reported that 65 percent of southern blacks and 53 percent of southern whites supported extending the temporary provisions of the VRA (i.e., Section 5).Footnote 160 Mel Bradley warned the president's chief domestic policy advisor, Martin Anderson, “If the President and/or the Republican Party are perceived as the enemy of the Voting Rights Bill, a national political backlash could develop, particularly in the South.”Footnote 161

However, the White House's position was not purely defensive, as some accounts have implied. They recognized that the VRA could help grow Republican support in key minority constituencies. In November 1981, James Baker received a memo from White House advisor Red Cavaney about support for a ten-year extension of the VRA. Cavaney predicted that Hispanics “will view the President's position in a favorable light,” while African Americans “will consider the President's position to the range from ‘neutral’ to ‘slightly’ positive.” On the other hand, Cavaney predicted, accurately, that conservatives “will be absolutely outraged.”Footnote 162

Hispanics were a growing electorate. Reagan had done well with this group in the 1980 election, and they were viewed as a priority electorate by Republicans. Nat Scurry, an advisor on civil rights in the Office of Management and Budget and himself an African American, shared in a memo to Edwin Harper, assistant to the president on policy development, that prominent Hispanic Republicans were urging a strong VRA extension. Scurry noted that Robert Mondragon, the lieutenant governor of New Mexico, had stated, “no issue is more important to the Hispanic Community than the extension of the Voting Rights Act.”Footnote 163 Elizabeth Dole reminded Richard Darman in an October 1981 memo about the VRA, “In view of the growing numbers of Hispanics in key states, and the increase in Hispanic Reagan voters in the past election, Hispanics have been targeted as a high-potential constituency for the future.”

These warnings were also made by Michael Uhlmann in the White House Office of Policy Development. Uhlmann warned that failure to support the strengthened VRA could do lasting damage to the Republican Party's image in the Hispanic community. Uhlmann wrote to Martin Anderson, “The average Hispanic will not understand the position the Administration takes. What he or she will understand, however, will be whether the President included Hispanics in his position.” Echoing Elizabeth Dole, Uhlmann explained that “recently naturalized citizen[s] are generally very patriotic and upright.… [The] recently naturalized were natural Reagan constituents. This was the basis of rationale for the large expenditures of campaign funds for materials in Spanish. This was precisely the target voter we were seeking and were quite successful in attracting.”Footnote 164

When discussing the optics of the VRA signing ceremony, Elizabeth Dole suggested not inviting key civil rights figures such as Jesse Jackson or Coretta Scott King because they would overshadow some of the Hispanic leaders whom the White House had invited such as Jose Cano (American GI Forum chairman), Hector Barretto (U.S. Hispanic Chamber of Commerce president), Rudolf Sanchez (Coalition of Spanish Speaking Mental Health Organizations [COSSMHO] president), and Fernando de Baca (Latin American Manufacturers Association [LAMA] president). Elizabeth Dole's emphasis on outreach with Hispanic leadership did not represent a repudiation of outreach efforts to African Americans, but a recognition that, on balance, it would be more important for Hispanic leadership to gain special recognition at the ceremony. Mrs. Dole explained, “The problem of inviting everyone has the potential to do more damage for the President in the Hispanic community than the Black community, since the stature of the Hispanic leaders who will be in attendance [will be less prominent].”Footnote 165 Reagan increased his support among Hispanic voters from 37 percent in 1980 to 44 percent in 1984.Footnote 166

Tatishe Nteta and Brian Schaffner have demonstrated that although American parties regularly make symbolic appeals to ethnic minority voters, these appeals are often indirectly expressed through support for policies popular in the minority communities rather than explicit community-based appeals. Nteta and Schaffner found that such appeals are made equally by both Democrats and Republicans. Hispanic electorates appear to receive the highest proportion of such appeals.Footnote 167

4.4 Pro–Civil Rights Means for Anti–Civil Rights Ends

Finally, some figures in the administration felt that positive coverage for supporting a strengthened VRA would provide political capital and cover for future policy, including opposition to more controversial, redistributive forms of civil rights in education, employment, and housing.

Given its high profile and prestige, the VRA extension was seen to provide the Reagan administration with some goodwill on civil rights. One internal memo from the administration reveals the view that providing support for the VRA could prove useful cover for more conservative racial policies, such as anti-busing measures and efforts to weaken affirmative action. Uhlmann was explicit on this point in a September 1981 memorandum to Ed Meese, James Baker, Martin Anderson, Lyn Nofziger, and Max Friedersdorf:

Presidential support for extension would remove the most poisonous arrow from their [i.e., the president's critics in the civil rights community] quiver and could be sold, in a positive sense, as a good-faith gesture to demonstrate that the President is not an enemy of civil rights. The political capital thereby acquired could be deployed in other areas where we will be changing policy, e.g., affirmative action and bussing [emphasis added].Footnote 168

Kenneth Cribb, assistant to the president for domestic affairs, made a similar observation that if the administration supported a strengthened VRA, the “civil rights lobby” would later on be less able to influence the administration's proposals on “the budget, affirmative action, busing, and the tax proposals.”Footnote 169

5. Conclusion

At one of the VRA's most vulnerable junctures in its history, Republican President Ronald Reagan signed an extension of the law that not only extended aspects loathed by conservatives for another twenty-five years but also overturned a recent conservative Supreme Court decision that had weakened the legislation. In so doing, Reagan gave his imprimatur to a piece of legislation that embraced race-conscious standards of identifying racial discrimination and violated core conservative principles about the role of the federal government in electoral administration. This was quite a turn for a president described by Edward Carmines and James Stimson as the “chief apostle of contemporary racial conservatism” who was responsible for “breathing new life into the Republican's [sic] southern strategy.”Footnote 170

Recent scholarship has offered one intriguing explanation for Republican support for the 1982 extension. Jesse Rhodes has argued that Reagan only “grudgingly endorsed” the extension and that it should be seen as “a serious political defeat” for the administration.Footnote 171 According to this view, the administration wanted to avoid being seen to be against the legislation publicly, knowing that covertly it could be weakened through less visible and accountable arms of the government (the bureaucracy and judiciary). This explanation has many appealing features and is broadly accurate, but it misses several key details.

First, such accounts overstate the uniformity of opposition to a strengthened VRA within the Reagan administration. Unquestionably, there were powerful actors in the DOJ, not least Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights William Bradford Reynolds, who wanted to use 1982 as an opportunity to weaken Section 2 and eliminate Section 5.Footnote 172 Yet, there were other figures in the administration who took the opposite view. White House Public Liaison Elizabeth Dole and black White House advisors—Mel Bradley, Thelma Duggin, and Nat Scurry—consistently argued in favor of a stronger bill and coordinated with race-conscious Republicans, such as the former Senator Edward Brooke, to make the case to moderates in the administration. As Corey Fields has recently demonstrated in his superb study of black Republicans, a race-conscious tradition of black Republicanism did not simply vanish once Barry Goldwater ran for president.Footnote 173 Joshua Farrington records that there were “few ideological differences between black delegates at the Republican or Democratic conventions” in 1980.Footnote 174 Fields finds evidence that race-consciousness has persisted in the black grassroots of the Republican Party to the present day.Footnote 175 Traces of this tradition could be found even in the Reagan White House.

Second, existing accounts are too passive. Rhodes, for instance, portrays Reagan's signing as a “defeat.”Footnote 176 The archival evidence shows that Republicans regarded the VRA as an opportunity for party-building. High-level Republicans saw the extension as a continuation of the outreach work the GOP began in the late 1970s, as chronicled by Leah Wright Rigueur and others.Footnote 177 Reagan administration officials also saw the potential to boost Republican support in the Hispanic community, for whom the VRA had assumed high importance after its inclusion of language minorities in the 1970s. Moreover, even administration skeptics of the VRA saw value in being aligned with a robust extension on the basis that it would buy the administration political capital to dismantle other elements of the civil rights state even more loathed by conservative constituencies, such as busing and affirmative action.

Third, too many accounts imply that the version of the bill signed by Reagan was inevitably the form that the bill would have to take, given public esteem for the VRA. President Reagan signed, effectively, a version of the bill that was authored by Democrats and civil rights organizations.Footnote 178 Rhodes implies that Reagan had no other options. It was “legislation they abhorred but were unwilling to block.”Footnote 179 Nonetheless, the administration acquiesced because they were confident that their racial coalition could “manipulate the unique characteristics of the various branches of the federal government to advance preferred racial agendas.”Footnote 180 Such an analysis does not hold in the context of the 1982 extension, which, as Berman noted, was uniquely strong compared to all other extensions. In particular, the insertion of an explicit effects-based standard in Section 2 represented a direct repudiation of the conservative judiciary's color-blind interpretation of the act. If conservatives were relying on the court to weaken the VRA, removing the ambiguity that had allowed the court to do so makes little sense. Indeed, contrary to Rhodes's thesis, the court confirmed the validity of the stronger, effects-based standard in Thornberg v Gingles in 1987. This standard remains in place to the present day, and since Shelby County v Holder effectively eliminated Section 5 preclearance in 2013, it is now the strongest element of the VRA.

Equally, strengthening Section 2 ran contrary to a strategy aimed at weakening the VRA through DOJ inaction. Rhodes is correct to say that the Reagan DOJ was more permissive in granting Section 5 preclearance approval than its predecessors, which in theory would enable jurisdictions to get away with a variety of minor voting rights infractions. Yet, many of these approvals were subsequently overturned in court using the Section 2 language that Reagan had signed into law. This state of affairs suggests, at best, an ineffective strategy, plagued by incoherence. I argue that such an outcome reflects the genuine disagreements within the Reagan administration and pushes back at Rhodes's depiction of steadfast Republican resistance to the VRA during this period. In doing so, this article situates itself in a middle ground between Berman's view of bipartisan consensus in favor of the VRA and Rhodes's depiction of ideological abhorrence but strategic acquiescence.