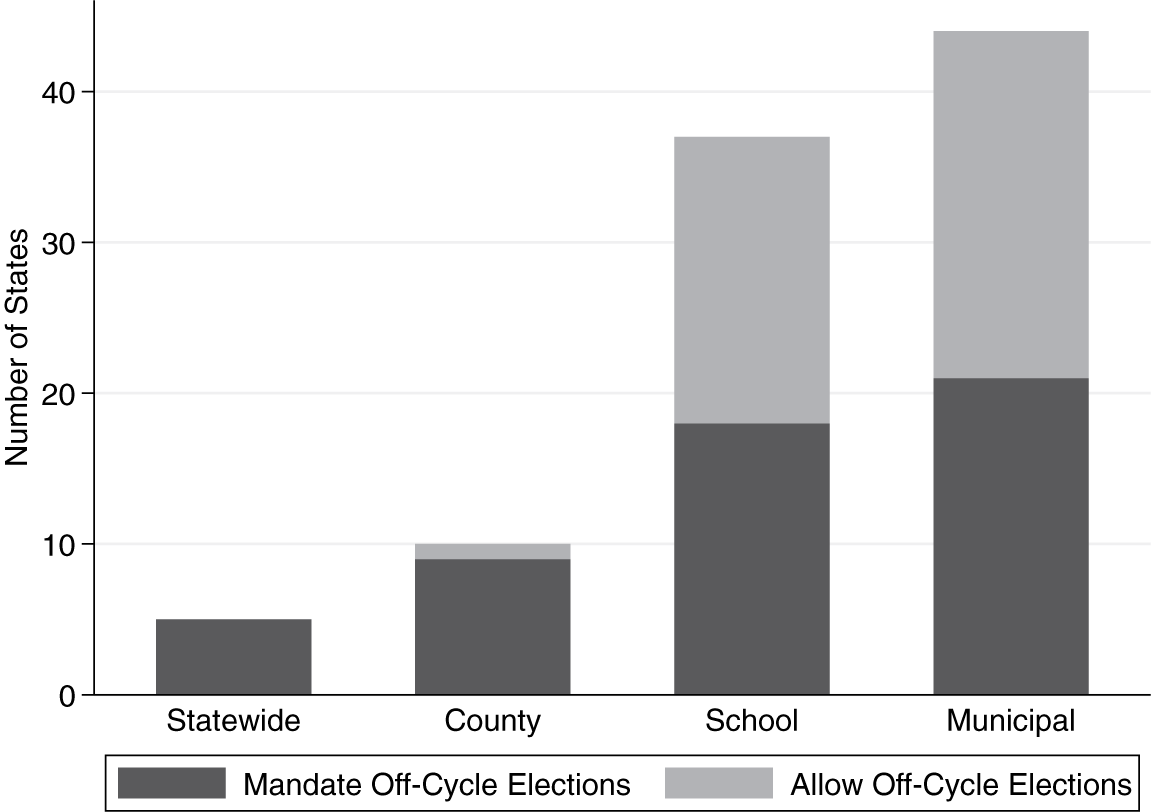

Holding elections at odd-times of the year, separate and apart from regular November federal elections, is a longstanding feature of America’s federalist democracy. The pervasive use of “off-cycle” elections has been shown to matter immensely: the day an election is held has the single greatest impact on the turnout and composition of the electorate (Anzia Reference Anzia2013). Yet the decision to hold on- versus off-cycle elections ultimately rests with political authorities in state government. As Figure 1 indicates, a majority of states have chosen not to consolidate their election calendars, instead opting to mandate or allow off-cycle elections (Anzia Reference Anzia2013).

Figure 1. State governments promote off-cycle election calendars.

Note. Figure displays the propensity of states to either mandate or allow various types of subnational governments to use off-cycle elections. Source: Anzia (Reference Anzia2013, 8–9).

While only a handful of states require that statewide (5) and county offices (9) be elected in off years, the vast majority of local governments—both single- and general-purpose governments—are elected in low-turnout races that are held apart from regular federal or statewide elections. For example, Anzia (Reference Anzia2013) identifies 21 states where municipal governments are required to use off-cycle elections and 18 states where school boards are elected entirely in off year races.

States clearly wield significant discretion over the election calendar. Yet compared to other electoral institutions, far less is known about the political consequences of holding off-cycle elections. In contrast to large literatures examining the representational effects of states’ voter registration laws (Hanmer Reference Hanmer2009), electoral rules (Powell Reference Powell2006; Powell Jr and Vanberg Reference Powell and Vanberg2000), direct democracy provisions (Arceneaux Reference Arceneaux2002; Gerber Reference Gerber1996; Lax and Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2009; Reference Lax and Phillips2012), term limits (Carey et al. Reference Carey, Niemi, Powell and Moncrief2006; Lax and Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012), and campaign finance laws (Caughey and Warshaw Reference Caughey and Warshaw2018; Flavin Reference Flavin2015; Matsusaka Reference Matsusaka2010), no one knows whether election timing influences the tone and direction of political representation. Inattention to election timing thus represents a major gap in our understanding of the relationship between political institutions and the quality of American democracy.

Our study offers a first-ever look into whether and how election timing impacts the relationship between citizens and their elected officials. As a starting point into what should become a much larger research agenda in political science, we examine the impact of off-cycle elections on mass–elite congruence in local school district governments. We find that school board governments that are elected in on-cycle elections are better-aligned with the political preferences of their local community. Specifically, we show that board members are more likely to share the ideological preferences of their district’s median constituent when they are elected in regular November even-year elections. Similarly, compared to boards that are elected off-cycle, on-cycle boards are more likely to share the education reform policy preferences held by the majority of their constituents. The remainder of this article proceeds as follows. We first review some relevant literature to help contextualize our core theoretical argument about why we anticipate that on-cycle/off-cycle elections will strengthen/weaken representation. We then discuss our data and empirical approach to theory testing, after which we present our results. The paper concludes with a brief discussion of the implications of our findings, providing some suggestions for future research on election timing and representation.

Relevant Literature and Theoretical Expectations

Two existing literatures speak to our key question of interest. The first is a large body of work on political representation and policy responsiveness. The second is a small but growing research literature on election timing. Our study puts these two literatures in dialogue with one another by examining whether election timing influences the subsequent tone and direction of political representation in American local government.

Decades of research indicate that citizens are fairly well-represented by their elected officials in subnational politics. In one of the most influential works in the field of state politics, Erikson, Wright, and McIver document a close correspondence between citizens’ general ideological preferences and state policy liberalism (Erikson et al. Reference Erikson, Wright, Wright and McIver1993). Others have extended the study of policy responsiveness to specific issues, validating the importance of citizens’ preferences in the state policy making (Butler and Nickerson Reference Butler and Nickerson2011; Lax and Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2009). More recently, scholars have uncovered evidence of opinion–policy congruence in local government settings (Berkman and Plutzer Reference Berkman and Plutzer2005; Einstein and Kogan Reference Einstein and Kogan2016; Tausanovitch and Warshaw Reference Tausanovitch and Warshaw2014). For example, city governments tend to reflect their constituents’ preferences on taxes and spending, with liberal cities spending and taxing their citizens more highly than cities composed of more conservative residents (Tausanovitch and Warshaw Reference Tausanovitch and Warshaw2014).

Although citizens appear to be well-represented in subnational politics, there are reasons to anticipate that such representation can be enhanced or diminished by key electoral institutions that mediate the relationship between voters and politicians. While Tausanovitch and Warshaw (Reference Tausanovitch and Warshaw2014) found little systematic evidence that electoral institutions impact the responsiveness of city governments, they nonetheless speculate about the strong potential of one kind of electoral institution to matter: election timing. We agree. In fact, our reading of the burgeoning literature on election timing leads us to conclude that off-cycle elections should produce governments that are systematically less representative of their median constituent’s political preferences.

For one thing, off-cycle elections substantially reduce voter turnout (Z. L. Hajnal and Lewis Reference Hajnal and Lewis2003; Z. Hajnal, Lewis, and Louch Reference Hajnal, Lewis and Louch2002; Wood Reference Wood2002), bringing less representative electorates to the polls on Election Day (Kogan, Lavertu, and Peskowitz Reference Kogan, Lavertu and Peskowitz2018). Second, by encouraging “selective participation” among a narrow subset of voters (Berry Reference Berry2009; Oliver and Ha Reference Oliver and Ha2007), off-cycle elections enhance the power of organized groups whose electioneering efforts become relatively more impactful in low-turnout elections (Anzia Reference Anzia2013). In her study of school districts, for example, Anzia (Reference Anzia2011) demonstrates that off-cycle elections enable teacher union interest groups to negotiate more generous salaries for their members. Likewise, Payson (Reference Payson2017) shows that compared to on-cycle electorates, off-cycle ones rarely punish incumbent school board members for failing to improve student academic achievement. In other words, off-cycle electorates are systematically less likely to engage in sociotropic retrospective voting.

When each of these insights is considered together, a clear picture emerges. It is one in which we should expect a qualitatively different type of electorate to be active and influential in on- versus off-cycle elections. On average, on-cycle electorates should be more demographically and ideologically representative of the average constituent (Kogan, Lavertu, and Peskowitz Reference Kogan, Lavertu and Peskowitz2018) and more likely to prize collective concerns over narrow constituency-specific policy benefits (Oliver and Ha Reference Oliver and Ha2007). Consequently, we hypothesize that governments that are chosen in on-cycle elections will tend to be more politically congruent with their constituents than otherwise similar governments that are chosen in off-cycle races.

This expectation is based on the simple calculus that the political preferences registered by on-cycle electorates are more likely to reflect the preferences of a community’s average citizen (compared to the preferences held by the subset of voters who participate in lower-turnout off-cycle elections). Assume that, in any winner-take-all election, the median voter’s preferred candidate will tend to prevail. Over time, we should observe governments that (in the aggregate) reflect the preferences of that median voter. However, since governments that are elected in off-cycle races are chosen by a median voter that is systematically less representative of their community, we should observe politics being moved “off-center,” away from the average citizen’s preferences. The political preferences held by officials who are elected in off-cycle races should therefore be less aligned with their community’s median constituent, causing governments to deviate from the preferences of the median constituent even as it predictably conforms to the preferences of an unrepresentative median voter. Below, we explain our approach to testing this simple theory that on-cycle elections will tend to produce governments that are more politically congruent with their constituents than off-cycle elections.

School District Governments

As Figure 1 indicated, there are many types of governments that one could examine to test whether election timing influences the tone and direction of political representation. We elect to test our theory by examining the specific case of mass–elite policy congruence in local school district governments. We do so for several reasons.

First, on substantive grounds, school districts are among the most important subnational governments (Howell Reference Howell2005). Not only are they one of the most numerous governments in the American political system, they also account for significant portions of the total expenditures made by subnational governments (Anzia Reference Anzia2011). Second, on methodological grounds, a focus on school boards allows us (as we explain more below) to accomplish what has so far eluded scholars—the opportunity to observe both citizen political preferences and elite officials’ position-taking in both on- and off-cycle electoral settings. Third, since prior research reveals that school districts are, on the whole, responsive to local electorates’ taste and preferences for more/less education spending (Berkman and Plutzer Reference Berkman and Plutzer2005), testing whether election timing influences citizen–board congruence makes good theoretical and empirical sense. Finally, the small existing literature on election timing has frequently focused on school districts, paying close attention to the way in which off-cycle elections enhance the political power of organized groups (Anzia Reference Anzia2013). School districts provide a clear window into these dynamics because of the outsized role that teachers’ unions play in school board politics (Moe Reference Moe and Howell2005; Reference Moe2006). Although rank-and-file teachers do not hold unidirectional political preferences, the key organizational vehicle that represents them in local politics—their union interest groups—are consistent champions of more liberal policies, especially as it relates to fiscal issues that impact public employee compensation (Anzia Reference Anzia2011; Moe Reference Moe2011). In other words, a focus on school districts gives us a concrete set of theoretical expectations that can be tested in a clear direction.

Admittedly, single-purpose school district governments have some peculiar properties. Districts are governed by lay board members who compete in low-turnout elections where union interest groups are highly organized and active. On the other hand, given the tabula rasa state of the literature, we see no reason to constrict the reach of our theory to school politics. Anzia (Reference Anzia2013), for example, found that off-cycle municipal elections yield more generous salaries for firefighters, even though firefighter pay is determined by general-purpose city governments. And, as we noted earlier, the authors of the largest existing study of policy responsiveness in local municipal government appear persuaded that the responsiveness of general-purpose city governments is ripe to be impacted by election timing (Tausanovitch and Warshaw Reference Tausanovitch and Warshaw2014). As a first test of the general theory that off-cycle elections stand to dilute political representation, school districts seem like a reasonable, if not logical place to start.

Data

Determining whether election timing affects the relationship between citizens and their elected officials presents a significant empirical challenge. Two types of data are needed. First, we need a way to measure the political preferences of citizens and their local officials so that we can test for mass–elite congruence. We then need variation in election timing: mass–elite congruence must be observed across a sample of districts that use on- and off-cycle elections.

Obtaining one, let alone both, of these measures is exceedingly difficult. For example, scholars typically use party vote share or survey data to measure citizens’ political preferences. However, such measures are not readily available across the nation’s 90,000 local governments. On the elite side, these data limitations are even more pronounced. Party labels cannot be used to infer most local officials’ political preferences, since local governments are often contested on a nonpartisan basis. Additionally, local officials do not vote on similar bills across districts (e.g., roll call votes), so there is no easy way to compare elites’ political preferences directly.

To overcome these many complications, we restrict our analysis to examining citizen–school board relations in a large sample of California school districts. We do so for three reasons.Footnote 1 First, a unique database of California voter registration and election results enable us to generate measures of citizens’ political preferences at the school district level. Second, several surveys of California school board members and candidates carried out over the past two decades make it possible to compare the preferences of elected school board members to their real-world constituents. Finally, California has historically allowed its school districts to use either on- or off-cycle school board elections, providing needed variation in our key independent variable of interest. Below, we detail how these pieces of data fit together to enable us to directly test whether election timing influences political representation.

Citizen (Mass) Preferences

To measure citizens’ political preferences across school districts, we rely on data from the Statewide Database (SWDB), a repository of voter registration and election results housed at the University of California, Berkeley.Footnote 2 The SWDB contains voter registration data and election results for nearly all of the statewide elections held in California since the 1990s. Importantly, the SWDB reports registration and election data at the census block level, which we then aggregate to school districts. Throughout the paper, we rely on several different measures from the SWDB to proxy citizens’ ideological and issue-specific policy preferences. First, we create a measure of citizens’ general ideological conservatism for each local school district in California. To do so, we calculate the percentage of registered Republicans minus the percentage of registered Democrats in each school district. As we explain more in the analyses that follow, this proves to be a robust measure of citizens’ general right–left political preferences. Second, to measure citizens’ attitudes about education policy, we use the SWDB to examine voter support for various education-specific ballot initiatives and an education reform-minded candidate that ran for the office of State Superintendent of Public Instruction in 2014.

Elected Officials’ (Elite) Preferences

To link citizens’ political preferences across school districts with the political preferences of their own school board members, we next need a way to measure board members’ policy preferences. Here we rely on several different surveys of California school board members and candidates. The first such survey was conducted by Grissom in 2005–06 (Grissom Reference Grissom2007; Reference Grissom2009). The strength of the Grissom survey is that it was administered to over 1,100 California school board members in a random sample of districts, stratified by district size. All board members in these districts were invited to participate, and the response rate yielded an impressive 63% of invited participants. In sum, the Grissom survey does an exceptional job of measuring aggregate board member ideological preferences across 200-plus unique California school districts that exhibited variation in election timing in the mid-2000s.

To complement our analysis of the Grissom survey, we rely on a second survey that we conducted in September 2018. Our survey targeted the same sample of districts surveyed by Grissom.Footnote 3 However, in our survey, we purposefully included some new items asking board members how they felt about education reform issues in California. Specifically, we asked whether board members supported or opposed the formation of more charter schools, an issue that has been both salient and increasingly controversial in the years since Grissom’s survey. Finally, we draw on a survey of California school board candidates carried out by Moe (Reference Moe and Howell2005) in the early 2000s.Footnote 4 Importantly, the Moe survey contains responses from both winning and losing board candidates who sought a board seat between 1998 and 2002. We rely on this survey to test whether board candidates who were better aligned—both ideologically and on specific education issues—with their districts’ voters were also more likely to win when they sought office depending on whether they ran in an on- or off-cycle election.

Election Timing

Our election timing data were gathered from a variety of sources, including our own hand-collection efforts, aided by several research assistants. We first relied on prior studies (Anzia Reference Anzia2011; Berry and Gersen Reference Berry and Gersen2011; Kogan, Lavertu, and Peskowitz Reference Kogan, Lavertu and Peskowitz2018) along with the widely consulted California Elections Data Archive (CEDA).Footnote 5 Our research assistants culled through old California local newspaper records and made direct outreach to county clerks of elections to confirm whether a given school district in our sample, during and leading up to the relevant year of our survey, was using on-cycle or off-cycle school board elections.Footnote 6

Empirical Strategy

Our basic empirical strategy is to estimate a series of regression models that take the following form:

where Elited denotes some aggregate political preference held by a school board located in school district d. These elite (board member) preferences are then modeled as a function of whether a district uses on-cycle elections, denoted by OnCycledβ1, along with Massdβ2, which measures the political preferences of the citizens (mass public) in district d. The key explanatory variable of interest is the interaction between these two variables—OnCycled * Massdβ3. If the coefficient β3 on this interaction term is both positive and statistically significant, it would indicate that school boards’ political preferences are more strongly aligned with the preferences of their district’s constituents when boards are elected in on- versus off-cycle elections.

Results

General Ideological Congruence

We first test whether on-cycle elected school boards display a greater degree of general ideological congruence with their constituents using the sample of boards surveyed by Grissom. Grissom asked board members whether they would characterize themselves as ideological conservatives (3), moderates (2), or liberals (1) on social and economic/fiscal policy issues, respectively. We elect to focus on board members’ responses to the fiscal ideology question, since the literature on election timing has shown that union interests are able to leverage low-turnout, off-cycle elections to boost public employees’ salaries (Anzia Reference Anzia2011; Reference Anzia2012; Reference Anzia2013). Across our sample of 214 school districts, the mean board’s aggregate fiscal policy conservatism was 2.43 (boards were generally more fiscally conservative than they were fiscally liberal), with a standard deviation of .43.

If our theory is correct, we should observe a stronger relationship between citizen and board conservatism in districts that elect their boards on-cycle. To empirically test this expectation, we estimate a series of regression models based on Equation (1) (above), where we regress the mean level of a board’s fiscal conservatism on a binary election timing indicator (1 = on-cycle; 0 = off-cycle), the partisan registration advantage that Republicans hold over Democrats in a district (citizen conservatism), and an interaction of these two variables. Table 1 (below) sets out the results for three separate regression models.

Table 1. Impact of election timing on citizen–board general ideological congruence

Note. Dependent variable is board economic conservatism. Columns 1 and 2 model a board’s average (aggregated) conservatism on a 1–3 scale (where higher values denote a more conservative board). Column 3 is a binary measure indicating whether a board is majority conservative (defined as at 50% or greater). Entries are Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) coefficients (Columns 1 and 2) and probit coefficients (Column 3) with standard errors in parentheses. All measures are two-tailed tests, except for the on-cycle interaction, because it is testing a one-directional hypothesis.

* p < 0.1;

** p < 0.05;

*** p < 0.01.

The baseline specification (with no controls) is presented in Column 1. Consistent with our expectation that on-cycle elections should strengthen the ideological congruence between citizens and their elected officials, the coefficient on the interaction on-cycle * Republican district is both positive and statistically significant (p < 0.05). The difference in citizen–board congruence between on- and off-cycle districts is substantively meaningful as well. For on-cycle districts, moving from a district where Democrats hold a 10-percentage point registration advantage to a district where Republicans hold a 10-percentage point advantage is associated with one-half of a full standard deviation more fiscally conservative board. In contrast, for off-cycle districts, the same upward shift in a district’s political conservatism is associated with only a quarter of a standard deviation more conservative board (i.e., half the effect size).

In Column 2, we add several control variables to our baseline model to account for basic demographic differences across districts including: district size (student enrollment), district poverty (the percentage of students eligible for free and reduced lunch), and district racial composition (the percentage of white students). Although we have no specific expectations with regard to these control variables, they are standard controls in education research. At a minimum, they help confirm that our core finding is not driven by simple demographic differences across districts that could potentially be the driving force behind a district’s propensity to hold on- versus off-cycle elections, or a district’s tendency to be responsive to its constituents.

Since political representation frequently hinges on obtaining majority control of government, in Column 3, we estimate a model predicting whether a board is majority fiscally conservative. Figure 2 (below) plots the marginal effects of our results from this probit estimation, showing that conservative board majorities are more likely to form in more Republican districts when elections are held on- rather than off-cycle. Once again, moving from an on-cycle district where Democrats outnumber Republicans by 10-percentage points to a district where Republicans outnumber Democrats by that very same margin is associated with a 27-percentage point increase in the likelihood that a board is majority fiscally conservative (74% versus 47%). In contrast, that same upward shift from a strong Democratic to a strong Republican district is only associated with an 11-percentage point increase in the likelihood of observing a majority fiscally conservative board when examining districts that hold off-cycle elections—a significantly weaker degree of mass–elite congruence.

Figure 2. Effect of district electorate’s partisanship on school board fiscal conservatism.

Note. Figure shows the marginal effects of the Republican share of a district’s electorate on the likelihood that the district’s board is majority conservative, separately for on- and off-cycle districts.

One potential concern with the findings presented so far is the possibility that district partisanship is an imperfect proxy for citizens’ political preferences about school spending. Districts with wealthy Republican voters may, for example, prefer larger school budgets for their own districts, even if they are fiscally conservative in national or state politics. We take two steps to ensure that district partisanship sufficiently captures citizens’ fiscal policy preferences in local school politics. First, we consult survey data from the Pubic Policy Institute of California (PPIC) that asked a representative sample of Californians (1) whether they would vote to increase local taxes to generate more school funding, (2) whether they would favor reducing the two-thirds requirement needed to enact such a tax increase, and (3) whether they would vote for a bond to fund a school construction project in their community. Because PPIC asked each respondent to indicate whether they were a registered Republican or Democrat, we can confirm that partisanship is a good proxy for citizens’ preferences on fiscal issues in local school politics. Across all three items, California Republicans were far more fiscally conservative than their Democratic counterparts. Whereas 43% of Democrats said they would support all three proposals to increase local taxes to raise more revenue for the local public schools, a scant 16% of Republicans were so inclined. These partisan differences were substantively and statistically significant (p < 0.05) across each individual survey item.Footnote 7

Although the PPIC data help bolster our confidence that partisanship adequately captures citizens’ fiscal policy preferences, we carry out one additional test to confirm the robustness of our core finding—that on-cycle elections strengthen the ideological congruence between citizens and their local government officials. Specifically, we replicate the results of the three estimations shown in Table 1; however, in place of our partisanship measure, we substitute a survey-based measure of citizen conservatism created by Tausanovitch and Warshaw (Tausanovitch and Warshaw Reference Tausanovitch and Warshaw2013). These authors use hundreds of thousands of survey responses to generate an estimate of citizens’ political preferences within small geographic units (e.g., cities, counties, and state legislative districts) using multilevel regression with poststratification. We leverage the fact that they provide their estimates at the level of state assembly districts, which we then allocate (by population size) to estimate citizen conservatism across school districts. Not only does the Tausanovitch and Warshaw measure correlate highly with our partisan registration measure (.65), but it performs equally well in each of the models shown previously in Table 1.Footnote 8 Altogether then, we find clear and consistent evidence that citizens who reside in school district governments that hold on-cycle elections are more likely to be represented by school boards that share their general ideological orientation toward fiscal policy making.

Issue-Specific Policy Congruence

Having established that on-cycle elections generate more ideological congruence between citizens and their boards, we next consider whether these findings can be extended to citizen–board congruence on a specific policy issue—one that is directly and increasingly relevant to local education politics: charter schooling. Measuring board support for charter schooling across California school districts is relatively straightforward, as we can rely on a question from our own 2018 school board member survey. Specifically, our survey asked nearly 350 school board members whether they would support or oppose the formation of more charter schools. On the citizen side, measurement is complicated by the fact that there are no surveys asking citizens in each California school district about their support for charter schools. Nor can we rely on partisanship or ideology, since citizens’ attitudes toward charter schools are not neatly aligned with traditional partisan or ideological commitments (Collingwood, Jochim, and Oskooii Reference Collingwood, Jochim and Oskooii2018; Reckhow, Grossmann, and Evans Reference Reckhow, Grossmann and Evans2015). To overcome this hurdle, we draw on the aforementioned SWDB to generate two separate measures of citizens’ support for expanding school choice through more charter schooling.

First, we leverage a unique election for California State Superintendent of Public Instruction (CSSPI). The 2014 CSSPI race between challenger Marshall Tuck and incumbent Tom Torlakson provided a rare opportunity to observe how Californians felt about a pro-charter school reform agenda. Since both Tuck and Torlakson were lifelong Democrats, partisanship was not an issue in the race; instead, the contest gained national attention as a battle over two competing visions of education reform. Tuck, the former director of a charter school management organization, made support for charters central to his campaign. He won the endorsement of the California Charter Schools Association and garnered significant financial backing from pro-charter groups around the country. In contrast, Torlakson pledged to slow charter school growth, providing more funding for traditional public, rather than charter, schools. In doing so, Torlakson won the strong backing of the state’s largest public sector union: the California Teachers Association (CTA).

How certain can we be that voters who cast a ballot for Tuck over Torlakson did so on the basis of the two candidates’ positions on charter schools? We first examined a series of statewide polls to confirm that the biggest divide between Tuck and Torlakson supporters was not partisanship, but rather membership in a union that stood opposed to charter schooling. These union members were, according to one analysis of the polling data, twice as likely to support the anti-charter candidate, Torlakson (Finley Reference Finley2014). We then examined the endorsements of the state’s five largest newspapers to confirm that the news media consistently informed the electorate that the race boiled down to a substantive divide between the two candidates on school choice and countervailing education reform philosophies, not the candidates’ partisanship, expertise, or personalities.Footnote 9 Suffice it to say, when Torlakson narrowly defeated Tuck in November (52% to 48%), it was clear that the race had been profoundly shaped by the candidates’ substantive differences on charter schooling.

To test whether school boards that are elected on-cycle are more likely to share their constituents’ views about charter schools, we replicate the same approach used earlier in the paper. Here, however, our outcome variable of interest—the percentage of each school board that supports charter schools—is regressed on a binary indicator for on-cycle elections, the percentage of citizens in each district who voted for pro-charter candidate Marshall Tuck, and an interaction between the two. Table 2 displays the results of four separate estimations. Column 1 presents the simple baseline model (no controls), whereas Column 2 adds controls for district size, racial composition, poverty, and district partisanship. Consistent with our theoretical expectations, we once again find that boards that are elected on-cycle are significantly more aligned with their constituents. The coefficient on the interaction term on-cycle * pro-charter district is positive and statistically significant, indicating that the correlation between citizen and board member support for charter schooling is stronger in school districts that elect their board members in November even-year elections.

Table 2. Impact of election timing on citizen–board congruence on charter school policy

Note. Dependent variable is the percentage of each district’s board that supports the formation of more charter schools. The models in Columns 1 and 2 use the percentage of the vote that each district gave to pro-charter candidate Marshall Tuck to measure citizen support for charter schools. Alternatively, the models in Columns 3 and 4 use the percentage of the district that voted in favor of Proposition 38, a statewide school voucher initiative. Cell entries are OLS coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses. All measures are two-tailed tests, except for the on-cycle interaction, because it is testing a one-directional hypothesis.

* p < 0.1;

** p < 0.05;

*** p < 0.01.

Although we are confident that voter support for Marshall Tuck provides a reliable proxy for citizens’ attitudes toward charter schools, as an additional robustness check, we draw on a second measure of citizen support for school choice to confirm the findings presented in Columns 1 and 2 of Table 2. As an alternative measure of citizen support for charter schools, we use voter support for a November 2000 ballot initiative—Proposition 38—that proposed to enact a statewide school choice/school voucher program in California. As can be seen in both the bivariate (Column 3) and multivariate models (Column 4), both of the interaction terms between on-cycle district * pro-charter district that employ this voucher-based measure of citizen support for school choice are positive and statistically significant in the expected direction.

Figure 3 (below) shows that the effect of on-cycle elections on board–citizen charter congruence is not just statistically significant, but substantively meaningful as well. Specifically, Figure 3 plots the marginal effects of citizen support for charter schooling on board support for charter schooling separately for on- and off-cycle districts. For example, moving from an on-cycle district where just 40% of voters supported the pro-charter candidate to an on-cycle district that gave Mr. Tuck 60% of the vote is associated with a 25-percentage point increase in a board’s support for charter schooling (42% versus 17% support). For off-cycle districts, however, no matter how much support voters gave to the pro-charter candidate, no net increase in board support for charter schooling is observed. In other words, off-cycle districts failed to elect boards that were supportive of charter schools even when a clear majority of the voters in those districts strongly supported expanding access to charter schooling.

Figure 3. Citizen–board congruence on charter school policy, by election timing.

Note. Figure shows the marginal effects of a district’s support for California State Superintendent of Public Instruction candidate Marshall Tuck on the percentage of the district’s board members that (like Tuck) support charter schools, separately for on- and off-cycle districts.

The Electoral Connection

Up to this point, we have provided two key pieces of evidence showing that local officials who are elected in on-cycle elections are more likely to hold political preferences that align with their districts than officials elected in off-cycle elections. But why? If we are correct that it is election timing itself that impacts mass–elite congruence, we should find that on-cycle elections increase the likelihood that candidates whose positions are more congruent with their constituents perform better at the ballot box. Conversely, candidates who hold political preferences that diverge from their constituents’ preferences should fare worse in higher-turnout on-cycle elections. To examine this possibility, we turn to the aforementioned survey of California school board candidates carried out by Terry Moe in the early 2000s. The Moe survey contains responses from both winning and losing candidates who ran for a board seat between 1998 and 2002 (three on-cycle and two off-cycle elections).

To measure board candidate ideology, we use a survey item that asked each candidate to place themselves on a 7-point scale from (1) very conservative to very liberal (7). To measure candidate position-taking on an issue that is directly relevant to local school politics, we draw on several survey items that Moe used to gauge the candidates’ attitudes toward unions and collective bargaining (CB) in education. Specifically, Moe used a factor analytic approach to generate a single (continuous) measure of each candidate’s overall favorability toward unions (where higher scores indicate that a candidate is more favorable toward unions and CB and a lower score indicates that a candidate is more hostile toward unions and CB).Footnote 10

On the citizen side, the Moe survey includes a simple binary indicator for whether a district is politically conservative (or not). This indicator was constructed from county voter files and assumes a value of 1 if at least 55% of registered voters in a district are registered Republicans (for more details, see Moe Reference Moe and Howell2005, 268). To generate a complementary district-level measure of citizens’ attitudes toward unions and CB, we turn once again to the SWDB database. As a proxy of voters’ attitudes toward unions, we create a measure of the percentage of voters in each school district who supported Proposition 75—an anti-union ballot initiative that was a focal point of California’s 2005 statewide special election.Footnote 11 Specifically, Proposition 75 sought to weaken public sector unions (like the aforementioned CTA) from raising money to spend in politics (supporters sometimes refer to these laws as “paycheck protection”).

Armed with measures of constituent and candidate preferences, we can proceed to test whether candidates are more likely to be held accountable for their ideological and issue-specific congruence in on- versus off-cycle elections. To do so, we estimate a series of probit regression models predicting whether a candidate won their election as a function of the policy/ideological preferences of the district a candidate is running in, a candidate’s own policy/ideological preferences, and the interaction of the two (our main explanatory variable of interest). Since higher quality candidates may be more likely to win irrespective of congruence, we also include a measure of each candidate’s incumbency status and union endorsement on the right-hand side to account for a candidate’s baseline level of quality.Footnote 12 To determine whether candidate congruence matters more in on- versus off-cycle elections, we estimate separate probit models for on- and off-cycle elections.

The results of those four estimations are arrayed in Table 3 (below). Columns 1 and 2 focus on the importance of a candidate’s general ideological congruence with their district. Consistent with our expectations, we find that candidates who are ideologically incongruent (e.g., self-described LCs running in politically conservative school districts) only perform worse when they seek office in on-cycle races. Specifically, the coefficient on the interaction term conservative district (CD) * liberal candidate (LC) is negative and statistically significant, but only in on-cycle elections (Column 2). Conversely, this same interaction term is positive and (nearly) significant in off-cycle elections (Column 1), suggesting that LCs may actually do a little bit better in CDs if the elections being held are contested off-cycle. Substantively, these differences in a candidate’s performance are large. All other factors being equal, a very liberal school board candidate that ran in a CD was 34 percentage points less likely to win than a very conservative candidate when the race was contested on-cycle; in contrast, that same very LC running in a CD was 17 percentage points more likely to win than a very conservative candidate if the election were held off-cycle.

Table 3. Incongruent candidates more likely to prevail in off-cycle elections

Note. Dependent variable is a binary measure for whether the candidate won their election. Cell entries are probit coefficients with standard errors clustered by school district in parentheses. Models also control for a candidate’s incumbency status and whether they were endorsed by the local teachers’ union. All measures are two-tailed tests, except for the on-cycle interaction, because it is testing a one-directional hypothesis.

* p < 0.1;

** p < 0.05;

*** p < 0.01.

Do these same patterns emerge when we examine the relationship between candidate and voter preferences on specific policy issues salient in education politics? In short, the answer is yes—at least when it comes to the issue of CB rights and unions in school district politics. Columns 3 and 4 of Table 3 report the results that focus on candidate–district congruence concerning support for unions and CB. Candidates whose political views on unions are more congruent with their districts fare better at the ballot box, but only when they run in on-cycle elections. Conversely, candidates who are out of step with their districts on CB have no trouble winning if they are running in off-cycle elections. This is consistent with Anzia’s (Reference Anzia2011; Reference Anzia2013) finding that off-cycle elections strengthen organized teacher union interest groups. It also suggests a potential mechanism explaining her result: off-cycle elections appear to make it easier to elect candidates favorable to public employees unions even in districts where most voters are hostile toward these unions.

For on-cycle districts, the strongest pro-union candidates (PUCs) were significantly less likely to win their election when the majority of their district’s voters supported the anti-union ballot initiative (i.e., they are running in anti-union districts). However, in off-cycle districts, these same staunchly PUCs were significantly more likely to win a board seat than their anti-union counterparts, even though the majority of voters in these districts were themselves anti-union. Taken together, our central empirical finding—that on-cycle elections promote greater congruence between elected officials and their constituents—appears to be driven by the fact that on-cycle elections provide less electoral “slack” for politically misaligned candidates. Candidates who deviate too far from their constituents in on-cycle districts are significantly less likely to win office. This can help explain why, as we have observed throughout the paper, governments that are chosen in off-cycle elections are more likely to be led by politicians who are less aligned with the political preferences of the citizens they represent.

Conclusion and Discussion

In this study, we have shown that the decision to hold on- versus off-cycle elections has important consequences for the tone and direction of political representation in the United States. Examining variation in the timing of school board elections in California, we found that boards that are chosen in on-cycle races are far more likely to hold political preferences that mirror the views of their constituents than boards elected in off-cycle elections. Importantly, we also found evidence that the most likely mechanism promoting greater congruence between on-cycle elected boards and their constituents is the nature of political accountability in on- versus off-cycle districts. Candidates whose political preferences deviate more from their constituents struggle to win on-cycle elections. However, candidates who hold preferences that are less congruent with their district can overcome this liability by winning office in lower-turnout, off-cycle elections.

Taken together, these findings have several important implications. First, they represent the first-ever empirical evidence that election timing influences the substantive tone and direction of the representation that citizens receive from their elected officials. Although a growing literature on election timing highlights a variety of electoral consequences that arise from holding off-cycle elections (Anzia Reference Anzia2013; de Benedictis-Kessner Reference de Benedictis-Kessner2018; Kogan, Lavertu, and Peskowitz Reference Kogan, Lavertu and Peskowitz2018; Payson Reference Payson2017), we are the first to show that election timing matters for political representation and democratic accountability.

Additionally, our study reveals that the policy choices made by state governments—specifically the choices states make about the rules that govern elections—can have important downstream effects on political representation in local governments. In the case that we have examined, many of the critical choices that local school district governments make about education policy are influenced long before local electorates enter the picture. For example, school boards in the 45 states that have charter school laws are often tasked with deciding whether to authorize new charter schools in their district. The conventional view of local politics assumes that such decision making will be shaped by “local control” (i.e., the appetite of the local electorate for more/less charter schooling). Our findings, however, suggest that in many cases local control is a mirage. Specifically, when state governments encourage or mandate that local districts hold off-cycle elections, subsequent board decision making on charter policy is more likely to be divorced from the preferences of a district’s average citizen. Not unlike the role played by party elites during the “invisible” primary (Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Karol, Noel and Zaller2009), the decision of political elites in state government regarding election timing can similarly impact the electoral power and influence of ordinary citizens.

Although our findings are both theoretically and empirically important, given that ours is the first-ever attempt to study the interplay between representation and election timing, our analysis raises many more questions than answers. First, we need to be cautious about declaring that on-cycle elections cause greater congruence between citizens and their officials. They may. But it is important to acknowledge that the inability to randomly assign election dates means that we are making some key assumptions about the factors that prompt governments to select and maintain off-cycle elections in the first place. As more governments move away from off-cycle elections in response to state-mandated consolidation reforms, future scholars will be well-positioned to design rigorous quasi-experimental studies that can isolate the causal effects of election timing. Much of that future work should investigate the consequences of election timing for representation in settings beyond school districts.Footnote 13

While our study helps move the ball down the field, more work remains to be done. Scholars might begin by asking whether off-cycle elections undermine political representation asymmetrically—weakening mass–elite congruence on a narrow subset of issues where organized interest groups are active and influential (e.g., client politics), but only scarcely impacting policy making when the costs and benefits of an issue are more broadly distributed (e.g., majoritarian politics; Wilson Reference Wilson1973). At the same time, scholars should forthrightly consider whether off-cycle elections provide any collective benefits to American democracy. One common argument that is made by those who defend off-cycle elections is the untested claim that such elections promote more fully informed electorates. At a time when critics of off-cycle elections have gained an upper hand in the debate over election reform, political scientists should empirically assess whether the subset of citizens who participate in off-cycle elections are more politically informed, even if fewer citizens are participating in these elections overall.

Above all, it is essential to recognize that the study of election timing is more than an academic exercise. State governments have clear authority to alter their election calendars. Research that can answer important questions about election timing has direct implications for state policy makers, many of whom are currently weighing the advantages and disadvantages of a consolidated election calendar (National Conference of State Legislatures 2016). While many consolidation proponents have drawn attention to potential cost savings and the ability to increase casual voter participation, our findings highlight a different consideration: the impact that election timing has on the quality of political representation in our federalist democracy.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/spq.2020.6.

Data Availability Statement

Replication materials are available on UNC Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.15139/S3/DFKFE5.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the excellent research assistance of Reilly Conroy, Madeleine O’Shea, Jaehun Lee, and Sofia Marino. We also wish to thank Sarah Anzia, Leslie Finger, Vladimir Kogan, Paul Manna, Domingo Morel, Zachary Peskowitz, and Beth Schueler for their thoughtful comments and suggestions. Finally, we wish to thank our anonymous reviewers and both the current and previous editors of the journal.

Funding Statement

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Biographies

Michael T. Hartney is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Boston College, and in 2020–21 W. Glenn Campbell and Rita Ricardo-Campbell National Fellow at the Hoover Institution. His current research focuses on subnational politics and policy making, especially K–12 education and, more generally, the workings of US political institutions. His work has been published at American Journal of Political Science, Public Administration Review, and Perspectives on Politics.

Sam D. Hayes is a Ph.D. candidate in Political Science at Boston College. His dissertation project – Courtroom Cartography: How Federal Court Redistricting Has Shaped Representation from Baker to Rucho – examines the causes and consequences of the federal judiciary’s involvement in redistricting, reapportionment and gerrymandering in the United States.