Though the US population has become more racially diverse over the past decade, the racialFootnote 1 composition of public office holders largely remains white (Pew Research Center 2019). In 2015, 91 members in the US House and Senate were non-white; this number grew to 106 in 2017 and 132 in 2020 (Congressional Research Service 2020). As the number of racial minority candidates competing for political office continues to rise, especially at state and local levels, researchers continue to ask: Do racial minority candidates get a fair shake from the press? Historically, the answer would be no. When minority candidates run, they often receive scant news coverage or coverage focusing disproportionately on race or race-related issues rather than campaign issues (McIlwain Reference McIlwain2011; Wu and Lee Reference Wu and Lee2005). Coverage of candidates, officeholders and nominees who are women of color is particularly skewed (Lucas Reference Lucas2017; Towner and Clawson Reference Towner and Clawson2016). These patterns in coverage are often attributed to the predominance of white, male culture in newsroomsFootnote 2 (Bravo and Clark Reference Bravo, Clark, Vos, Hanusch, Dimitrakopoulou, Geertsema-Sligh and Sehl2019), or the preferences of mainstream (i.e., white, English-speaking) audiences (Abrajano and Singh Reference Abrajano and Singh2009).

Taking a different approach from scholars focusing on the role of newsroom diversity on news content (e.g., Gilens Reference Gilens1999; Nishikawa et al. Reference Nishikawa, Towner, Clawson and Waltenburg2009), our research explores how racial congruence between the newsroom, the candidates, and the audience influences coverage of candidate traits. Voters often rely on their perceptions of candidate traits to form an overall impression about the candidate, which in turn influences vote choice (Bartels Reference Bartels and King2002; Fridkin and Kenney Reference Fridkin and Kenney2011; Hayes Reference Hayes2011). People pay more attention to negative messages than positive information (Fiske Reference Fiske1980), and negative traits weigh more in voters’ overall assessment of candidates (Fridkin and Kenney Reference Fridkin and Kenney2011). If the media disproportionately highlight negative traits of racial minority candidates, or cover fewer positive traits in comparison to white candidates, voters could evaluate minority candidates negatively, which may affect their chances of getting elected. Moreover, skewed coverage of minority candidates could reinforce negative stereotypes associated with minorities or limit their broad appeal by connecting them with a limited set of—mostly race-related—issues (Schaffner and Gadson Reference Schaffner and Gadson2004; Zilber and Niven Reference Zilber and Niven2000).

Our findings suggest that newsroom diversity and audience demographics matter. As the percent of minority reporters in the newsroom increases, news outlets are less likely to associate non-white candidates with positive traits such as competence, experience, and reliability, but more likely to do so for white candidates. This finding—though not as hypothesized—speaks to the constrains that minority journalists face in the newsroom (see Shafer Reference Shafer1993; Weaver and Wilhoit Reference Weaver and Wilhoit1996; Ziegler and white Reference Ziegler and White1990). We also find that the larger the size of the voting-age non-white population, the faster favorable news coverage ratchets up for non-white candidates than for white candidates. We discuss the implications of this mixed evidence for racial congruence in our conclusion.

Racial Diversity in Campaign News Coverage

Previous research concludes that candidates who belong to racial minority groups typically earn less media attention during campaigns (Besco, Gerrits, and Matthews Reference Besco, Gerrits and Matthews2016). When they do earn coverage, it often disproportionately focuses on their race (Major and Coleman Reference Major and Coleman2008; McIlwain Reference McIlwain2011), stereotypes (Zilber and Niven Reference Zilber and Niven2000), the novelty of their candidacy (Gershon Reference Gershon2012; Ward Reference Ward2017), or racialized issues such as immigration or welfare (Ward Reference Ward2016a). Zilber and Niven (Reference Zilber and Niven2000) found that though Black representatives portrayed themselves as having diverse interests and representing the interests of all their constituents, the media tended to depict them as powerless in Washington and narrowly focused on racialized issues. In biracial elections where one candidate is a minority, the media tend to focus disproportionately on the race of the minority candidate (Schaffner and Gadson Reference Schaffner and Gadson2004; Terkildsen and Damore Reference Terkildsen and Damore1999). When a woman of color is winning at the polls, she is less likely to enjoy the spike in coverage that a white male candidate would get, and is likely to be covered using racialized frames (Besco, Gerrits, and Matthews Reference Besco, Gerrits and Matthews2016).

Negative coverage is also linked with candidates’ race and gender. Gershon (Reference Gershon2012) found that white men, white women, and minority men who were members of the House earned almost an equal amount of positive coverage when they ran for reelection during the 2006 midterm elections, while women of color candidates got disproportionally more negative coverage compared to the other groups. Other studies indicate that racial backgrounds only influence coverage of nonincumbent candidates. In Tolley’s (Reference Tolley2015) analysis of the 2008 Canadian federal election, for example, in open-seat races where both candidates were challengers, only white candidates received positive coverage of their qualifications.

Together, these findings suggest that journalists often consider minority candidates’ gender and race as novel and newsworthy; however, intense focus on these aspects could create the unintended effect of highlighting white and male candidates as the default political candidate (Ward Reference Ward2016b) while constraining perceptions of minority candidates’ expertise to a narrow set of racialized issues. In addition, minority candidates are at a disadvantage if journalists consider them newsworthy only when race and gender are broadly salient, such as in the 2008 Democratic presidential primary election when Black congresswomen received increased media attention due to the spotlight on gender and race (Lucas Reference Lucas2017).

Influence of Newsroom Diversity

Newsroom diversity is often offered as a solution to the problem of racism in journalism. A Reuters’ survey of newsroom leaders (Cherubini, Newman, and Nielsen Reference Cherubini, Newman and Nielsen2020) found that in the wake of the Black Lives Matters protests, 42% of respondents cited improving ethnic diversity as the most pressing diversity priority for the next year while only 18% mentioned gender diversity as a priority. Scholars also consider newsroom diversity an important factor to improve the coverage of minority groups (Caliendo Reference Caliendo2018; Saldaña, Sylvie, and McGregor Reference Saldaña, Sylvie and McGregor2016). The expectation is that “female and minority reporters are able to provide a non-white or nonmale perspective in the news” (Zeldes and Fico Reference Zeldes and Fico2005, 373). Research supports this view. For example, Weaver and Wilhoit (Reference Weaver and Wilhoit1996) found that journalists belonging to racial minority groups possess a strong sense of racial identity and are driven by the need to represent their in-group members. In practice, non-white reporters are more likely than their white colleagues to include non-white sources in stories (Zeldes and Fico Reference Zeldes and Fico2005), which is a result of the social responsibility norms that motivate journalists to accurately portray the nation’s diversity (Commission on Freedom of the Press 1947). Non-white journalists use lesser racist and discriminatory language in coverage of events such as the Black Lives Matter movement (Leopold and Bell Reference Leopold and Bell2017).

On the aggregate level, however, minority journalists contribute to a very small portion of the stories (see Ziegler and white Reference Ziegler and White1990), partially due to the limited editorial freedom reporters have in selecting stories and determining how they are used in news broadcasts (Weaver and Wilhoit Reference Weaver and Wilhoit1996). Numerous studies show that minorities remain underrepresented in the news. This is caused by biases in news production (Clark Reference Clark2017). Both producers of content and owners of news media are still predominantly male, middle aged and white, and their influence is felt in gatekeeping practices, story selection, and frames and sources used in stories (Bravo and Clark Reference Bravo, Clark, Vos, Hanusch, Dimitrakopoulou, Geertsema-Sligh and Sehl2019).

Further, newsroom culture may prevent minority journalists from changing traditional patterns in coverage. Black and Latino journalists are still subject to traditional journalistic norms established by white-majority newsrooms and may fear being perceived as unprofessional or fear the loss of potential for career advancement if they advocate on behalf of their communities (Johnston and Flamiano Reference Johnston and Flamiano2007; Nishikawa et al. Reference Nishikawa, Towner, Clawson and Waltenburg2009; Wilson Reference Wilson and Cottle2000). Faced with an ever-shrinking newsroom population and resources, journalists may also find themselves unable to conduct community outreach to build a database of diverse sources. For example, journalists on a tight deadline found there was “virtually no time to develop sources within minority communities” (Clark Reference Clark2014, 9). Newsroom budget and staffing cuts over the last several years have offset prior gains in newsroom diversity, stalling the trend in newsroom diversity growth and producing a plateau between 2012 and 2015 (Sui et al. Reference Sui, Paul, Shah, Spurlock, Chastant and Dunaway2018). The commercially oriented media system in the US coupled with the increasingly competitive media landscape adds complexity to newsroom diversity as a solution to inequities in coverage.

Influence of Audience Diversity

The demographic composition of audiences also shapes the volume and nature of minority candidate coverage. Most news organizations are driven by profits and gear content toward target audiences, often defined by demographics (Abrajano and Singh Reference Abrajano and Singh2009; Branton and Dunaway Reference Branton and Dunaway2008; Hamilton Reference Hamilton2004). For example, ethnic newspapers in areas populated by Latino, Korean and Chinese immigrants tend to provide more news about immigrants’ home nations than the US (Lin and Song Reference Lin and Song2006). Grose (Reference Grose2006) found that Latino officials are more likely to be covered by Latino media outlets and the likelihood of coverage increases when candidates represent predominantly Latino districts.

The tone used to cover minority populations depends on audience demographics and geographic location (Branton and Dunaway Reference Branton and Dunaway2009a, Reference Branton and Dunaway2009b). For example, although both Spanish-and English-language news programs target women aged between 18 and 34 years, Spanish-language news depicts immigrants more positively than the latter (Abrajano and Singh Reference Abrajano and Singh2009). Distance from the US-Mexico border also influences the amount and tone of immigration news coverage. The tone of coverage is largely negative in places close to the border, except predominately Latino markets (Branton and Dunaway Reference Branton and Dunaway2009a). In towns distant from the border, newspapers do not allocate much coverage to immigration, and the tone of coverage is comparatively positive, even in predominately white markets (Branton and Dunaway Reference Branton and Dunaway2009a). Overall, in places where racially diverse newsrooms cater to a large and diverse population, there is increased focus on racialized issues such as immigration and welfare, based on perceptions that these issues are important to the audience (Sui et al. Reference Sui, Paul, Shah, Spurlock, Chastant and Dunaway2018).

The Importance of Trait Coverage in Electoral Campaigns

Though race-related factors affect many aspects of minority candidate coverage, this study concentrates on trait coverage. Candidate traits—in addition to other factors such as partisan identity or campaign issues—play an important role in vote choice (Hayes Reference Hayes2011). Trait evaluations act as heuristics to help voters determine how a candidate is different from the opponent and the extent to which the candidates share their values (Hetherington, Long, and Rudolph Reference Hetherington, Long and Rudolph2016).

Traits ascribed to candidates depend on many factors, including social identity (Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993a; Sigelman et al. Reference Sigelman, Sigelman, Walkosz and Nitz1995), the type of office for which they are running (Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993b), and political party (Hayes Reference Hayes2005; Hetherington, Long, and Rudolph Reference Hetherington, Long and Rudolph2016). Broadly speaking, voters tend to associate men, candidates running for executive office, and the Republican Party with traits such as toughness, which signifies expertise on issues such as foreign policy and national security (Barnes and O’Brien Reference Barnes and O’Brien2018). On the other hand, Democrats, women, and those running for legislative offices are associated with empathy and compassion, or traits associated with competence on social welfare issues such as healthcare and education (Escobar‐Lemmon and Taylor‐Robinson Reference Escobar‐Lemmon and Taylor‐Robinson2005; Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2009; Krook and O’Brien Reference Krook and O’Brien2012).

Trait evaluations of minority candidates are often stereotypically driven; minority candidates are often perceived as more liberal and more inclined to advocate for racialized issues than white candidates (Fulton and Gershon Reference Fulton and Gershon2018; Lerman and Sadin Reference Lerman and Sadin2016; Sigelman et al. Reference Sigelman, Sigelman, Walkosz and Nitz1995). Candidate trait evaluations are increasingly related to party. In the 1980s, most voters associated the office of the president with qualities such as integrity and decency; but with the growth of polarization in the late 2000s, positive traits are ascribed only to candidates from their own party (Hetherington, Long, and Rudolph Reference Hetherington, Long and Rudolph2016).

Voters’ perceptions of candidate traits also depend on media coverage, which provides cues about candidates’ traits (Hetherington, Long, and Rudolph Reference Hetherington, Long and Rudolph2016; Wintersieck and Carle Reference Wintersieck and Carle2020). Campaign news often favors trait coverage over issues (Dunaway et al. Reference Dunaway, Lawrence, Rose and Weber2013), in part because voters consider candidate traits an important measure of electability. But imbalances between trait and issue coverage can have electoral ramifications. For example, women candidates are thought to be disadvantaged because they get more trait-based coverage than men (Dunaway et al. Reference Dunaway, Lawrence, Rose and Weber2013; Fowler and Lawless Reference Fowler and Lawless2009), especially when they run for executive offices such as governor or president which are associated with masculine traits and issues (Meeks Reference Meeks2012). Disproportionate emphasis on traits and resultant deficits in issue coverage are potentially harmful to women and candidates of color, especially if they preclude opportunities to demonstrate issue competencies.

When local news focuses disproportionately on traits, it primes voters to rely on them as the primary criteria to evaluate candidates (Iyengar and Kinder Reference Iyengar and Kinder1987). In addition, by focusing on the race and gender of candidates, the news media activates racial and gender stereotypes which are more frequently connected to trait inferences (Fridkin and Kenney Reference Fridkin and Kenney2011). For example, as race-based local news coverage of Obama increased, negative racial stereotypes were primed, and liberals became significantly more likely to rate him as untrustworthy (Wintersieck and Carle Reference Wintersieck and Carle2020).

On the other hand, trait coverage does not always harm candidates. Voters tend to evaluate candidates positively when the media highlights counter-stereotypic information—i.e., traits not commonly associated with the candidate’s political party or social identity (Hayes Reference Hayes2011). Moreover, given the growth in political polarization, trait coverage outside those indicative of partisanship or ideology may be relatively ineffective for shifting perceptions among partisan voters (Hayes and Lawless Reference Hayes and Lawless2015). However, recent evidence suggests that in certain elections, trait coverage may be particularly important in voters’ decision-making process. The American public has never been good at articulating coherent sets of policy preferences, and trait-based evaluations require less political sophistication and cognitive processing (Hetherington, Long, and Rudolph Reference Hetherington, Long and Rudolph2016). Similar cognitive biases may explain why coverage of candidates’ negative traits is more powerful and durable relative to coverage of positive traits.

Hypotheses

Theories of social identity and self-categorization provide the foundation for our expectation that racial congruence should matter for trait coverage—specifically, that candidate trait coverage is a function of the interplay between the racial characteristics of candidates, newsroom personnel, and audiences. As social animals, we self-identify as members of groups to feel a sense of belongingness, esteem, and pride. We do this by unconsciously inferring positive qualities upon our own group (or in-group), and negative qualities on the out-group (Calhoun Reference Calhoun1994; Kunda Reference Kunda1990).

Racial in-groups are formed by people who identify with the racial identities of other members in the group (Markus Reference Markus2008; Omi and Winant Reference Omi and Winant1994). When group identity is race-based and there is a history of associated racial conflict, people are more likely to ascribe positive qualities to in-group members than out-groups (Devine Reference Devine and Tesser1995). Based on shared racial identity, people are likely to think that they “share other similarities, such as culture, histories, values, and viewpoints, leading to greater identification” (Coleman Reference Coleman2011, 340). These implicit beliefs and stereotypes are beyond conscious awareness, easy to activate but hard to control (Blanton and Jaccard Reference Blanton and Jaccard2008), and arise from habit or “unconscious associations stored in long-term memory” (Payne et al. Reference Payne, Krosnick, Pasek, Lelkes, Akhtar and Tompson2010, 1). They are in stark contrast to explicit biases that are effortful to recall, consciously monitored, and deliberately evoked (Gawronski and Bodenhausen Reference Gawronski and Bodenhausen2006). Studies have found that implicit bias affects support for government policies (Banks and Hicks Reference Banks and Hicks2016; Knowles, Lowery, and Schaumberg Reference Knowles, Lowery and Schaumberg2010), attitudes toward candidates (Plant et al. Reference Plant, Devine, Cox, Columb, Miller, Goplen and Peruche2009) and voting behavior (Payne et al. Reference Payne, Krosnick, Pasek, Lelkes, Akhtar and Tompson2010).

Journalists, like everyone else, identify with certain groups based on shared characteristics (see Fiske Reference Fiske and Tesser1995; Johnson Reference Johnson2010; Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel and Turner1979) such as age, gender, and race (Jost and Hamilton Reference Jost, Hamilton, Dovidio, Glick and Rudman2005). Consequently, journalists’ racial identity may override their professional identity to affect the way they report news (Husband Reference Husband2005; Johnson Reference Johnson2010; Matsaganis and Katz Reference Matsaganis and Katz2014). Social identity theory provides many reasons to expect journalists to provide more positive portrayals of candidates of the same race relative to those with different racial identities, even without their conscious awareness. First, racial cues often arouse or intensify people’s feelings of group solidarity, resulting in in-group favorability (see Tajfel Reference Tajfel1981; Turner et al. Reference Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher and Wetherell1987). This is especially true for racial groups that are underrepresented in US politics (Chong and Rogers Reference Chong, Rogers, Wolbrecht and Hero2005). This is consistent with the idea of linked fate, which contends that some individuals in racial groups feel inextricably tied as a whole, such that they will consider the needs of their own racial group when making decisions (Sanchez and Masuoka Reference Sanchez and Masuoka2010; Simien Reference Simien2005).

The presence of more minority journalists in the newsroom may implicitly affect the process of news production (Johnson Reference Johnson2010) by providing in-group representation in the newsroom for minority candidates. Presumably, driven by unconscious in-group favorability, non-white journalists are more likely to cover their in-group members (i.e., minority candidates) and do so in a more positive, nuanced, and complex manner. Thus, we propose the following racial congruence hypotheses:

H1 (Candidate-newsroom Congruence Hypothesis): As the percent of non-white newsroom staff increases, non-white candidates are likely to receive (a) more positive trait coverage and (b) less negative trait coverage than white candidates.

As suggested by the economic theories of news (Hamilton Reference Hamilton2004), the production of news depends on the demographic characteristics and preferences of audiences (also see Branton and Dunaway Reference Branton and Dunaway2009a, Reference Branton and Dunaway2009b). News outlets may infer preferences for white candidates among white audiences, and preferences for minority candidates among minority audiences (Branton and Dunaway Reference Branton and Dunaway2008). If so, outlets in markets with substantial minority audiences will be more likely to cover minority candidates positively:

H2 (Candidate-audience Congruence Hypothesis): As the percent of non-white audience increases in the news media’s target market, non-white candidates are likely to receive (a) more positive trait coverage and (b) less negative trait coverage than white candidates.

These expectations do not presume news portrayals of candidates are racist; instead, the racial traits of candidates, audiences, and journalists serve as implicit cues in the news production process, influencing news coverage of in-group and out-group candidates. When these three race-related factors interact, an amplification effect is likely to occur. For example, when non-white readers constitute the majority in a news market, it can lead to perceptions about market preferences, which shape profit incentives for the news organizations. A desire to cater to the preferences of a predominant group in the market, or an effort not to alienate a substantial portion of the market may increase the likelihood of positive coverage for non-white candidates. While minority journalists may generally tend to pitch more stories about minority candidates and with favorable depictions than their white colleagues, they may feel especially comfortable doing so under favorable market conditions. It may also be that minority journalists are always more likely to offer more material for positive minority candidate coverage, but that news managers are more likely to accept these contributions under said favorable market conditions. Thus, we posit that:

H3 (Candidate-newsroom-audience Congruence Hypothesis): The likelihood for non-white candidates to receive (a) more positive trait coverage and (b) less negative trait coverage than white candidates from a racially diverse newsroom is higher in markets with larger minority audiences.

Data and Method

To get the appropriate data for testing the hypothesized racial congruence effects, we used several sources. We started with the Candidate Emergence in the States Project (Juenke and Shah Reference Juenke and Shah2015), an expert-coded database of legislative candidates running for offices in 2012, including their race, ethnicity, and gender. Next, we used Access World NewsFootnote 3 to collect news articles covering each state legislative candidate documented in the Candidate Emergence in the States Project database, using their first and last name as the search term.Footnote 4 We excluded op-eds and editorials from the search. Following extant work, we isolated our search of candidate coverage to “September 1—Election Day” (Dunaway et al. Reference Dunaway, Lawrence, Rose and Weber2013). This produced our initial dataset, which included 3,247 news stories about 1,414 state legislative candidates from 295 newspapers circulating in 13 states (including CA, CO, FL, GA, IL, LA, MI, NC, NM, NV, NY, OH, and PA) between September 1 and the Election Day.

Next, two trained researchers manually coded all 3,247 articles to categorize the trait coverage associated with a given candidate (also see Online Supplement B for full codebook). During this process, we identified 1,088 articles that did not cover any of the candidates in the Candidate Emergence in the States Project database.Footnote 5 These articles were eliminated.

Finally, we used the 2012 American Society of Newspaper Editors (ASNE) Newsroom Census data and the State Legislative Election Returns (SLERs) data (Klarner et al. Reference Klarner, Berry, Carsey, Jewell, Niemi, Powell and Snyder2013) for information on newsroom diversity and the racial composition of each state legislative district. Out of the 295 newspapers in our initial dataset, 115 participated in the 2012 ASNE survey, allowing for the retrieval of their newsroom demographic data. We removed articles from the 180 newspapers that did not appear in the ASNE database. These steps—as illustrated in Figure 1—produced our final dataset that contains 984 news articles about 591 legislative candidates from 115 newspapers circulating in 13 states. These 984 news articles were eventually used for analyses reported in this article.

Figure 1. An illustration of data preparation steps that led to loss/change in the number of news articles for analysis.

Variables and Measurements

Dependent Variables. Our dependent variables capture whether a news article links a candidate to positive or negative traits, which were manually coded by two researchers. To maximize intercoder validity, we referred to extant scholars’ (Dunaway, Shah, and Paul Reference Dunaway, Shah and Paul2016; Hayes and Lawless Reference Hayes and Lawless2015) measures of traits associated with candidate viability, which itemize positive traits such as “accomplished,” “contemplative,” “responsible,” “hardworking,” and “knowledgeable,” as well as negative traits such as “careless,” “clueless,” “incompetent,” and “ineffective” (see Online Supplement B for more trait measures).

Two coders were first asked to judge whether a story was about any specific candidate—if not, the coding procedure was terminated; if yes, they were asked to code whether the article explicitly talked about or suggested some positive traits [or negative traits] about the candidate. If a news article included one or more words/phrases/sentencesFootnote 6 indicating positive traits, it was coded as 1 for the “positive trait coverage” variable, which represents “at least one positive trait mention.” If it mentioned no positive traits at all, regardless of any mentions of negative trait or neutral traits, it was coded as 0 and indicates “no mention of positive traits at all.” The same scheme was used to code the “negative trait coverage” variable, where 1 indicates “at least one negative trait mention” and 0 represents “no mention of negative traits at all.”Footnote 7

This manual coding method produced two dependent variables where (Positive Trait Coverage) is a dichotomy capturing whether a news article highlights one or more positive traits for a given candidate (Krippendorff’s α = 0.70).Footnote 8 The other dichotomous variable (Negative Trait Coverage) captures whether a news story associates a candidate with one or more negative traits (Krippendorff’s α = 0.89).Footnote 9

Independent Variables. The first independent variable, (Non-White Candidate), captures the racial classification for each state legislative candidate running for office during the 2012 election cycle. Race was codedFootnote 10 in the Candidate Emergence in the States Project (Juenke and Shah Reference Juenke and Shah2015), and we used this in our sample of legislative candidates (see Online Supplement A for details of the coding process). This variable was measured dichotomously at the candidate level and captured whether a candidate is non-white, including Latino, African American, Asian American, or multiracial.

Our second independent variable, (%Newsroom Minority), captures the extent of newsroom diversity for each of the newspapers covering the races in our database. It focuses on the racial composition of reporters and is measured as the total percentage of African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and multiracial reporters in the newsroom. Data for this variable were drawn from the 2012 ASNE Newsroom Census.

The third independent variable is (%Minority Audience), which captures the total percentage of non-white voting-age population for the state legislative voting districtFootnote 11 in which the newspaper is located. Based on the idea that campaign coverage is crafted with the pool of potential voters in mind, we rely on the SLERs’s index to scrapple the percentage of voting-age minority populations (including African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and multiracial people) within each state legislative district. Percent Minority Audience is measured at the state legislative district level.

Control Variables. Based on extant literature, we controlled for a total of five variables in our models. The first three were drawn from the Candidate Emergence in the States Project and were measured on the candidate level. They include: Incumbent—a dummy that captures whether a state legislative candidate was currently incumbent for the position they were running; Women Candidate that captures whether the candidate is a woman (versus man); and Minority Opponent, which captures whether a candidate’s opponent is white or one of the other racial categories. The second set of control variables capture the characteristics of newspapers and their audiences. As newspapers with a large circulation differ from small news organizations in their selection and presentation of news stories (Hayes and Lawless Reference Hayes and Lawless2015),Footnote 12 this study controls for Circulation, a dummy variable drawn from the 2012 ASNE Newsroom data to capture whether a newspaper has a circulation of 10,000 and aboveFootnote 13; and % Male Audiences, which is measured at the state legislative district level and captures the percentage of male adults in each state legislative district’s voting-age population.

Final Dataset for Analysis

In sum, the final dataset (N = 984) was comprised of 984 news articles from 115 newspapers about 591 legislative candidates running for offices in 13 states. Out of the 984 articles, 51 were coded as “1” (at least one positive trait mention) and 933 were coded as “0” (no positive traits were mentioned at all) for the “positive trait coverage” outcome variable. For the other dependent variable “negative trait coverage,” 15 were coded as “1” (at least one negative trait mention) and 969 were coded as “0” (no negative traits were mentioned at all). These low occurrences of trait may simply reflect the journalistic norms of objectivity, which is also in line with previous studies that found trait coverage took up a substantively small portion of newspaper coverage of gubernational campaigns (Dunaway et al. Reference Dunaway, Lawrence, Rose and Weber2013; Kahn Reference Kahn1995). The electoral impact of trait coverage at such low volumes remains an open question. We will return to this point in section “Discussion.”

Among the 591 legislative candidates in our final dataset, 80.37% were male and 17.60% were currently incumbents for the positions they were running in 2012. Regarding their racial background, 77.66% were white, 8.12% were Black, 6.43% were Latinos/Hispanics, and the other 7.78% were Asians, Native Americans, or other non-white categories. In terms of partisanship, 288 were Republicans, 264 were Democrats, and the other 39 were Independents, Libertarians or without party affiliation. In addition, 88 legislative candidates had a non-white opponent and the other 503 had a white opponent running for the same position. Also see Online Supplement C for the measurement and descriptive statistics of each variable.

Results

This study investigates the impact of racial characteristics associated with newsrooms, legislators, and audiences—what is also referred to as racial congruence effect—on two outcome variables: positive trait coverage and negative trait coverage.

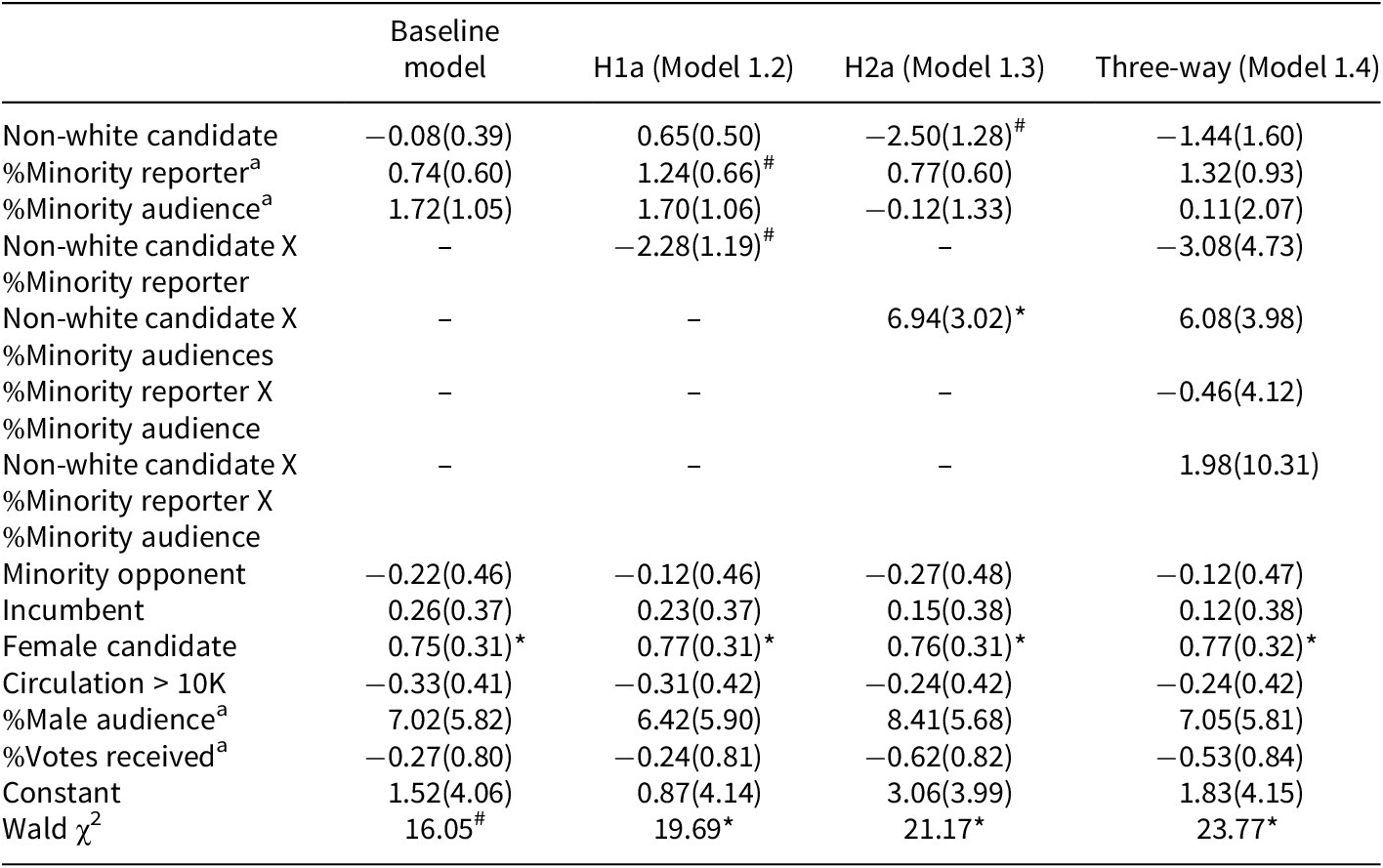

For each dependent variable—as displayed in Tables 1 and 2—we modeled three interaction effects to test our hypothesized conditional relationships, while controlling for a set of confounding variables.Footnote 14 Though the unit of analysis for our dependent variable is news article, our predictors are measured on multiple levels including news organization, candidate, and legislative state district levels. Thus, to correct for the heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation issues associated with nested data, we clustered all models by the combination of three nesting variables—news organization, legislative candidate, and legislative state district.Footnote 15 In addition, because some predicting and control variables had extremely skewed distributions, we used log transformation to address the skewed data, as denoted in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Penalized maximum likelihood estimation models predicting news coverage featuring positive traits (versus no mentions of positive traits at all)

Note. N = 984. All variables are dichotomous except for those with an “a” subscript, which are continuous variables and were logged to account for skewness. Entries are coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses. #p < 0.10, *p < 0.05

Table 2. Penalized maximum likelihood estimation models predicting news coverage featuring negative traits (versus no mentions of negative traits at all)

Note. N = 984. All variables are dichotomous except for those with an “a” subscript, which are continuous variables and were logged to account for skewness. Entries are coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses. #p < 0.10, *p < 0.05.

Consistent with previous work (Dunaway et al. Reference Dunaway, Lawrence, Rose and Weber2013; Kahn Reference Kahn1995), this study reveals that trait coverage constituted a substantively small portion of newspaper coverage of gubernational campaigns—51 out of the 984 news stories targeting a given candidateFootnote 16 in our final dataset were categorized as “positive trait coverage” stories, and 15 out of the 984 stories were categorized as “negative trait coverage” stories. This low volume of trait coverage requires us to follow recommended strategies for dealing with rare events data, “binary dependent variables with dozens to thousands of times fewer ones (events, such as wars, coups, presidential votes, decisions of citizens to run for political office, or infections by uncommon diseases) than zeros (‘nonevents’)” (King and Zeng Reference King and Zeng2001, 138).Footnote 17 Following previous work, we employed rare-event logistic regression (King and Zeng Reference King and Zeng2001) and penalized maximum likelihood estimation (Coveney Reference Coveney2015) to reduce estimation bias. Both produced consistent and robust estimates—we report results using penalized maximum likelihood estimation here and present the results of the rare-event logistic regression in Online Supplement D.

Moderating Effects of Minority Journalists and Audiences

We begin with the finding that the relationship between candidates and positive trait coverage is conditioned by the newsroom demographic make-up (Model 1.2: b = −2.28, two-tailed p = 0.055, 95% CI [−4.60, 0.04]). As plotted in Figure 2, the predicted likelihood of positive traits coverage is about 3% higher for non-white candidates than for white candidates when there are no minority reporters in the newsrooms; and this difference minimizes with an increase in the number of minority journalists. In newsrooms with a big portion of minority journalists, there is a slightly higher likelihood of producing more positive trait stories for white candidates than for non-white candidates, with the other factors remaining constant. We also compared the effects resulting from a 10th to 90th percentile change in the continuous (%Minority Reporter) variable. For newsrooms ranking among the 10th percentile, the predicted probability of receiving positive trait coverage for non-white candidates was about 3.12% higher than that for white candidates. For news media ranking among the 90th percentile, the predicted probability of receiving positive trait coverage was 4.86% lower for non-white candidates than for white candidates. Thus, although our model suggests the difference in receiving positive trait coverage between white and non-white candidates is conditional on the percentage of minority journalists in the newsroom, the direction of this change is opposite to our expectation. Thus, H1a has mixed support.

Figure 2. Predicted probability of news coverage featuring positive traits, by candidate’s race and newsroom diversity.

Note. Figure is generated using (H1 test) in Table 1, which illustrates a two-way interaction effect between candidates’ ethnicity and the percentage of minority journalists in newsroom.

Audience demographics also affect mentions of positive candidate traits (Model 1.3 in Table 1: b = 6.94, p < 0.05, 95% CI [1.03, 12.85]). Figure 3 illustrates that the predicted possibility of positive trait coverage for white candidates was almost identical across media markets that differ in the portion of minority audiences, as denoted by the solid line. When turning to news coverage of non-white candidates, however, the likelihood of news stories featuring positive traits dramatically increases when voting-age minority audiences constitute a large portion of the population in the newspaper’s area of circulation, as denoted by the dashed line. We again compared the effects resulting from a 10th to 90th percentile change in the continuous (%Minority Audience) variable: in media markets ranking in the 10th percentile, the predicted probability of receiving positive trait coverage for white candidates is about 4.97% higher than for non-white candidates. On the other hand, when media markets rank in the 90th percentile in terms of the minority audience composition, the predicted probability of receiving positive trait coverage for non-white candidates is 4.01% higher than that for white candidates. This lends support to H2a that as the percent of non-white audiences increases in the news media’s target market, non-white candidates are likely to receive more positive trait coverage than white candidates.

Figure 3. Predicted probability of news coverage featuring positive traits, by candidate’s race and audience diversity.

Note. Figure is generated using (H2 test) in Table 1, which illustrates a two-way interaction effect between candidates’ race and the percentage of minority voting-age audiences in each newspaper’s circulating state district.

This study also hypothesized a three-way interaction effect between minority reporters, candidates, and audiences on patterns of news coverage (H3a); however, our models did not yield statistically significant estimates (see Models 1.4 and 2.4 in Tables 1 and 2).Footnote 18 We also found little evidence for our hypotheses regarding candidate coverage with negative traits (H1b, H2b, and H3b).

Robustness Checks

Together, we find that with all the other factors remaining fixed, non-white candidates are less likely to receive positive trait coverage than white candidates from news outlets where the percent of non-white reporters in newsroom is high (Figure 2); however, when news outlets see a large portion of non-white audiences in their media market, non-white candidates are more likely to receive positive trait coverage than white candidates (Figure 3). While the sections above discuss several explanations for this finding, it is necessary to empirically test other explanations. In particular, the lack of evidence for a three-way interaction effect between candidates, journalists, and audiences may suggest that minority journalists’ favorability toward non-white candidates was not necessarily affected by the preference of audiences in a diverse market. If so, is there something else about the newsroom, political candidates, or even political races that could explain the pattern of coverage?

To test this idea, we conducted a series of multivariate penalized maximum likelihood logistic regressions with (a) the percentage of non-white supervisors in newsroom, (b) the incumbency status of candidates, and (c) the competitiveness of the races. These variables were used as contingent factors for testing the interaction effect between the race of candidates and that of journalists. In all cases, the three-way interaction effects were statistically insignificant (see Online Supplement G), suggesting these are not necessarily the reasons that drive a more diverse newsroom to produce more positive trait coverage for white candidates.

Discussion

While recognizing that race is an important determinant for media coverage of legislators (Husband Reference Husband2005; Tolley Reference Tolley2015), we know little about how reporters, candidates, and audiences operate in tandem to affect trait coverage of candidates. Through an analysis of campaign coverage about candidates running for state legislative offices during the 2012 election cycle in 13 states, we investigate a conditional newsroom-candidate congruence phenomenon.

With regard to positive trait coverage for candidates at the state legislative level, we find that when newsrooms feature a large percent of non-white reporters, non-white candidates become less likely to receive positive trait coverage than white candidates. This finding, though opposite to what we hypothesized, indicates that the newsroom-candidate interplay is complicated. Our follow-up models indicate that newsroom characteristics such as the percentage of minority supervisors, and election level factors such as the competitiveness of the race or candidate incumbency may not affect this newsroom-candidate interplay. The possible cause for this trend could be other factors that were not measured in this study. Ideas of professionalism and deeply entrenched news-gathering routines could be preventing minority journalists from breaking the norm and challenging traditional patterns of news coverage (Nishikawa et al. Reference Nishikawa, Towner, Clawson and Waltenburg2009). While white reporters attributing positive traits to non-white candidates would not raise eyebrows, minority reporters doing the same could be perceived as unprofessional and biased (Shafer Reference Shafer1993). More research is needed to investigate this further.

When it comes to negative trait coverage, we see little evidence that the newsroom composition contributes to any gap that may exist between white and non-white candidates. As displayed in Table 2, non-white candidates are slightly more likely to receive negative trait coverage than white candidates, which lends support for the argument that “non-white candidates do not fit the norm of politicians as do white candidates, and this distinction is often considered novel and newsworthy by the media” (Besco, Gerrits, and Matthews Reference Besco, Gerrits and Matthews2016, 4645). However, this study finds this difference to be statistically insignificant. Moreover, this variance is not conditional on the dominance of white journalists in the newsroom, indicating that an increased presence of non-white reporters may not necessarily reduce the negative trait coverage of non-white candidates. Although these results do not echo much of the existing literature (Sui et al. Reference Sui, Paul, Shah, Spurlock, Chastant and Dunaway2018; Saldaña, Sylvie, and McGregor Reference Saldaña, Sylvie and McGregor2016), they are a valuable point of departure signaling the importance of partitioning candidate coverage by specific traits, issues, tones, etc., when responding to claims of news bias against non-white candidates.

Our results show support for the candidate-audience congruence hypothesis. When the proportion of minorities in a newspaper’s circulation area rises, positive trait coverage for non-white candidates increases. Candidate trait coverage is thus influenced by market level audience demographics. News organizations are sensitive to the demands of target audiences in a given market, and audience taste subconsciously acts as a cue that influences journalists’ coverage of candidates (Branton and Dunaway Reference Branton and Dunaway2008; Sui et al. Reference Sui, Paul, Shah, Spurlock, Chastant and Dunaway2018). Thus, in areas with a high proportion of minority audiences, the news media ascribe positive traits to minority candidates in coverage. Other election level factors not measured in this study could also explain this finding. For example, we know that minority candidates are more likely to get elected in majority–minority areas (Marschall, Ruhil, and Shah Reference Marschall, Ruhil and Shah2010). Minority candidates could be spending campaign resources in areas with large minority populations. They could be sending promotional materials to reporters, offering exclusive interviews with the press, organizing publicity-generating events such as meet-the-candidate forums (Issenberg Reference Issenberg2012) or establishing media outreach through field offices (Darr Reference Darr2016), all of which could contribute to increased positive coverage. These same factors may have also contributed to the relatively unchanged possibility of positive coverage for white candidates, regardless of the varied portions of minority audiences across media markets (see Figure 3). It is possible that white candidates in our database did not have much media outreach in these majority–minority areas, or the white candidates were not scrutinized through lens of race, such that their positive trait coverage remained equivalent across media markets with varied percent of non-white audiences.

Lastly, the lack of statistically significant estimates for the three-way interaction effects between the race of candidates, journalists, and audience market is interesting. Though recent work has identified economic motive as one possible route through which newsroom diversity can work to leverage news coverage of traditionally underrepresented minority groups (Sui et al. Reference Sui, Paul, Shah, Spurlock, Chastant and Dunaway2018), this study suggests an exception. In the case of trait coverage, the impact of newsroom racial composition is not conditioned on a need to appeal to the diversified market. Instead, other factors may drive this tendency, such as minority journalists’ aversion against being pigeonholed into in-group member-specific assignments (Pritchard and Stonbely Reference Pritchard and Stonbely2007), especially when their white colleagues assume they are hired to fill racial quotas (Shafer Reference Shafer1993). Driven by time pressures, minority journalists may also intentionally seek to cover white candidates who dominate politics and are thus more accessible. Other studies also indicate crucial interference that comes from media owners, which “act as racial arbitrators by limiting racial emphasis” (Terkildsen and Damore Reference Terkildsen and Damore1999, 680). Yet, given our focus on the outlet-level observational data, we cannot explore the impact of these factors. Future studies can add more nuance by exploring whether and how an individual journalist may react differently depending on the racial identities of legislators and the racial composition of market audiences. Though we find a modest overall impact of newsroom diversity on candidate coverage in this study, the racial composition of the newsrooms is known to affect other areas such as issue coverage (Sui et al. Reference Sui, Paul, Shah, Spurlock, Chastant and Dunaway2018), portrayals of Latinos (Sui and Paul Reference Sui and Paul2017) and other minority communities (Jenkins Reference Jenkins, Campbell, LeDuff, Jenkins and Brown2012).

While this study represents one of the first steps in understanding the influence of racial congruence on candidate trait coverage, a few caveats are necessary to address. Though it examines the cross-sectional correlation between reporters, candidates, and audiences, this relationship may not be static or exogenous. As our data come from the height of the 2012 election cycle when news coverage was likely more focused on the competitive presidential campaign rather than state legislative races, it is possible that our results may underestimate the extent to which racial congruence affects news coverage of state legislative candidates. News coverage off-cycle from presidential campaigns may yield different patterns. More research across more election cycles and contests is needed to examine this racial congruence effect. Second, we use the district level racial composition of voting-age populations as a proxy for the demographics of the newspapers’ audiences. This could be problematic given the presence of specialty media directed at minority groups or the presence of two or more newspapers of differing ideologies circulating in the same geographical area and having different audiences. In the absence of publicly available data on a newspaper’s audience demographics, future research should endeavor to find more accurate measures for this variable. Another point to note is that this study compares white candidates with non-white candidates as a whole. Though researchers found significant differences in how the media cover candidates belonging to one minority group over another (Gershon Reference Gershon2012), data-related limitations unique to our dataset made it difficult for us to conduct group-wise comparisons of various minority groups. As elucidated above, our final dataset had a low volume of trait coverage. When viewed by legislative candidates’ racial backgrounds, we also noticed stark differences: out of the 51 positive trait articles, 40 were about white candidates, 5 were about Black candidates, 6 were about Latino/Hispanic candidates, and none was about Asian/Native American/Other candidates. Out of the total of 15 articles featuring at least one negative trait, 13 were about white candidates and the other two were about Black candidates. We encourage future studies to conduct finer-grained analyses to investigate this.

This study is one of the first systematic examinations of how the race of reporters, candidates, and audiences intersect to influence the news coverage of in- and out-group candidates. We develop, test, and demonstrate strong support for the candidate-audience congruence effect on candidate trait coverage. From an empirical perspective, it sheds light on the conditions under which news media improve the portrayals of non-white candidates running for public office. This line of inquiry is particularly important electoral environments in which the number of minorities seeking office is growing; and we hope more scholars will join us to expand this work. Some options for future research include focusing on a more nuanced measurement of trait coverage—for example, measuring positive/negative trait coverage on the paragraph or sentence level and focusing on the counts of trait coverage, or comparing trait coverage to nontrait stories (i.e., stories with a focus on horserace or strategy). Scholars should also examine the impact of additional variables such as the presence of media conglomerates in media markets. In addition, a qualitative approach can help address questions such as how the construction of diversity in the newsroom can be problematic, especially in the presence of white-passing newsroom staff who could be used to check the diversity requirement while being pressured by their supervisors to not be overly contentious.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/spq.2021.31.

Data Availability Statement

Replication materials are available on SPPQ Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.15139/S3/8BLDFQ.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank Drs. Paru Shah and Johanna Dunaway for providing the multiple original datasets needed for the intended analyses in this study, as well as for their comments, suggestions, and proof-reads that helped improve this paper. We’d also like to thank the anonymous SPPQ reviewers for providing valuable suggestions that greatly helped strengthen this manuscript.

Funding Statement

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Biographies

Mingxiao Sui is an assistant professor in Department of Communication Studies at University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

Newly Paul is an assistant professor in Mayborn School of Journalism at University of North Texas, Denton, TX.