Corruption is a global problem and its occurrence has been identified in various countries during various periods (Tanzi, Reference Tanzi1998). Nevertheless, despite the importance of this subject, very few theoretical models exist that help understand corruption (Judge et al., Reference Judge, McNatt and Xu2011). From a psychological standpoint, even though this subject has much to contribute, proposals for systematization are few or non-existent. From a broader perspective, when taking other scientific disciplines into account, and even though systematization exists on a larger scale as opposed to psychology, no models may yet be found the seek to integrate the various factors that can assist in understanding corruption. Psychology, through its premise of multiple determinants of behavior, provides various relevant contributions on this subject, such as the multilevel approach (Pettigrew, Reference Pettigrew2018), when the interaction of contextual factors with individual and group variables are fundamental to understand human behavior.

With this scenario as a backdrop, the lack of integrative models and the pressing need for work that systematizes corruption, dishonesty and behavioral ethics, the objective of this theoretical study was to propose the Analytical Model of Corruption (AMC). To achieve this objective, the first step was to define the concept of corruption based on correlated phenomena. The improved definition of the phenomenon was used for a more precise proposition of the AMC. Models relating to corruption found in human and social sciences are also described. Finally, the potential of AMC is indicated, in comparison to other models, as a theoretical perspective that, although based on psychological science, may contribute with interdisciplinary research on corruption.

The Concept of Corruption

For the proposal of the AMC as a theoretical model for corruption, it is necessary to identify the conceptual limits and similarities of corruption with correlated constructs. In this work, this conceptual analysis of corruption was developed through a comparison between unethical and dishonest behavior due to conceptual overlap.

(Un)ethical behavior may be defined as the conduct of an individual that is subject to the moral norms of a certain group (Treviño et al., Reference Treviño, Weaver and Reynolds2006). Based on revisions and meta-analysis (Kish-Gephart et al., Reference Kish-Gephart, Harrison and Treviño2010; Treviño et al., Reference Treviño, den Nieuwenboer and Kish-Gephart2014), it can be seen that the construct has been systematically applied in psychology, especially in the field of organizational psychology, by which Rest’s (Reference Rest1986) four-component model has been widely used by researchers interested in the ethical decision-making process (Lehnert et al., Reference Lehnert, Park and Singh2015; Treviño et al., Reference Treviño, Weaver and Reynolds2006). Current psychological research on unethical behavior seeks to identify, from an interactionist perspective, individual and contextual factors to understand the phenomenon (Lehnert et al., Reference Lehnert, Park and Singh2015).

On the other hand, dishonest behavior consists of, as does unethical behavior, the violation of norms, allowing for dishonesty to be seen as a form of expression of unethical behavior. In support of this, after a meta-analysis of unethical behavior, the authors chose the term “dishonesty” to be one of the keywords to investigate the construct as they considered dishonest behavior to be a specific type of unethical behavior (Kish-Gephart et al., Reference Kish-Gephart, Harrison and Treviño2010). Although understood to be an expression of unethical behavior, dishonest behavior has some characteristics that differentiate it from other unethical actions. In general, to understand dishonesty, it is necessary to consider an author, the act, the victim and the expected results (Scott & Jehn, Reference Scott and Jehn1999).

It is possible to identify the contributions of various fields towards understanding dishonest behavior, examples of which are economy and psychology (Mazar & Ariely, Reference Mazar and Ariely2006). In cost-benefit models, typical in the economy, it is assumed that human beings are rational and deliberative. As such, dishonesty would occur based on a comparison between possible risks and extrinsic rewards. If the benefits outweigh the risks, it is more likely the dishonest behavior will take place (Becker, Reference Becker1968).

On the other hand, psychological theory, aside from extrinsic rewards, include factors that are linked to intrinsic rewards. For example, there is neuroscientific evidence indicating that actions based on socially accepted norms, such as cooperation, stimulate areas of the brain that are linked to pleasure, in a way that is similar to the stimulation that occurs due to extrinsic reward (Rilling et al., Reference Rilling, Gutman, Zeh, Pagnoni, Berns and Kilts2002). As such, an honest action, by itself, may generate (intrinsic) rewards for the individual. This finding has contributed towards studies that seek to understand the rationalization strategies that favor the legitimation of dishonest actions and reduce intrinsic discomfort (Mazar et al., Reference Mazar, Amir and Ariely2008), as well as the development of interventions aimed at reducing dishonest actions (Ayal et al., Reference Ayal, Gino, Barkan and Ariely2015).

Additionally, psychological theory posits that the process of involvement in dishonest actions may not be overall conscious, seeing that there are various cognitive biases limiting rationality (Kahneman & Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979). For example, there is evidence that loss aversion, a cognitive bias, may favor dishonest behavior (Schindler & Pfattheicher, Reference Schindler and Pfattheicher2017). Furthermore, in many cases, an individual may just not be aware that certain behavior is dishonest (Darley, Reference Darley2005). To understand dishonesty it is therefore necessary to evaluate the relationship between intrinsic, extrinsic rewards, and possible biases in judgment and decision-making of a dishonest decision.

In light of the above, dishonest behavior may thus be considered as the action (not necessarily conscious) of an individual that, when breaking a rule, may generate a reward (directly or indirectly) for that individual, as well as generate loss (directly or indirectly) for someone else (e.g.: a person, organization, the State), in addition to losses to oneself (intrinsic or extrinsic). This definition merges typical elements of economic cost-benefit theories (i.e., extrinsic rewards and gains) as well as psychological theories (i.e., the absence of a conscious process, intrinsic rewards) (Mazar & Ariely, Reference Mazar and Ariely2006, for a comparison between psychological theories and economic theories).

Corruption, like unethical and dishonest actions, is associated with the violation of rules and norms (based on a legalistic definition of the phenomenon Peters & Welch, Reference Peters and Welch1978). It is also assumed, as in dishonesty, that there is a possibility of obtaining rewards. However, corruption has one characteristic that differentiates it from other behaviors: Abuse of power. Generally, corruption is defined as the abuse of entrusted power for private gain (Transparency International, 2018). Although this definition is widely used, it has been criticized. The concept of “entrusted power” does not include, for example, those who have risen to power without the express confidence of all or of a majority to legitimate that power, as is the example of dictatorships.

Additionally, the idea that the gain would be “private” allows us to infer that corruption is restricted to individual gains (private) and does not take into account wider dimensions such as benefits to groups, organizations, political parties or even countries. As a result of these and other limitations, based on the adaptation of the original Transparency International definition, corruption can be defined as the misuse of power to obtain illegal gains (Andersson & Heywood, Reference Andersson and Heywood2009). This definition overcomes the limitations of the previous definition and has a more generic nature, covering various behaviors that can be understood as corrupt. The causes and consequences of corruption have been studied mainly at the macro level, where negative effects on various sectors of society have been verified, as is the example of education and health (Tanzi, Reference Tanzi1998).

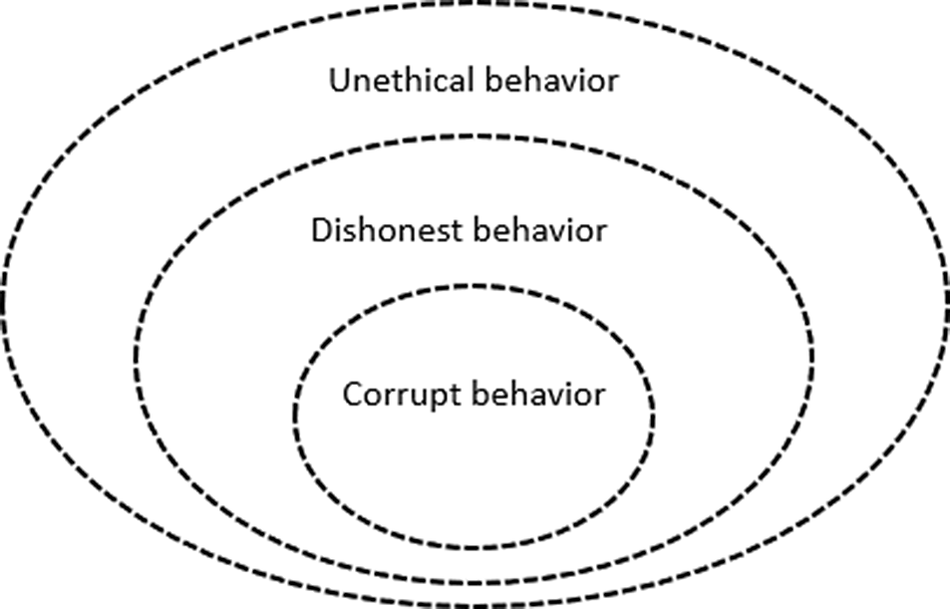

Conceptually, the relationship between unethical behavior, dishonest behavior and corrupt behavior can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Diagram of the relationship between unethical behavior, dishonest behavior and corrupt behavior.

As can be seen in Figure 1, unethical behavior encompasses dishonest behavior where, in turn, corrupt behavior is included. The common ground among all of these is the violation of norms or rules. In the diagram, corruption is stated as a more specific phenomenon, especially due to its characteristic of abuse of power, which is dispensable from the definition of the other constructs.

It is important to point out that, although only the relationship between these three constructs is represented in the diagram, each one may include various subtypes. Corrupt behavior, for example, despite being more specific in the diagram, has different aspects and forms of expression, as is the example of cronyism, bribery and white-collar crime, among others that will not be specifically considered in this work.

It should also be emphasized, with regards to the conceptual proposal, that, although it is admitted that the violation of norms and rules is the common element to the three phenomena (unethical behavior, dishonest behavior and corrupt behavior), one should bear in mind that this concept is based on a broader perspective relating to the evaluated norms and rules. Situations exist where dishonest behavior and corruption are justified within small groups or organizations by descriptive norms (norms about what people effectively do), however, injunctive norms (what is known to be the correct thing to do) are still being violated on a social dimension.

It is further emphasized that the dashed lines used in the diagram indicate that, in spite of the conceptual effort, those limits are not always clearly perceived when the phenomena occur naturally. This, however, does not mean the researchers should not consider this differentiation. The conceptual difference between each phenomenon contributes to better implementation and, consequently, results in improved research.

It was found that the level of concern among researchers in differentiating corruption from related topics was low. The difficulty in defining and delimiting the constructs results in greater difficulty in implementing them for the research and development of theoretical models. We have drawn up a proposal for the differentiation and convergence between concepts that seeks to overcome this conceptual challenge and contribute towards the proposition of the AMC.

Theoretical Models on Corruption

Despite the rising interest in the study of corruption since the 1990s, a multitude of studies on this subject seem to exist without real corroboration between related fields and lacking the development of theoretical models to guide research. Among the 42 studies used to compile a meta-analysis, 26 do not provide a theoretical model to substantiate them (Judge et al., Reference Judge, McNatt and Xu2011). One of the theoretical models used, which was an exception in the meta-analysis, was the Corruption Institutional Choice Analytic Frame (CICAF) (Collier, Reference Collier2002).

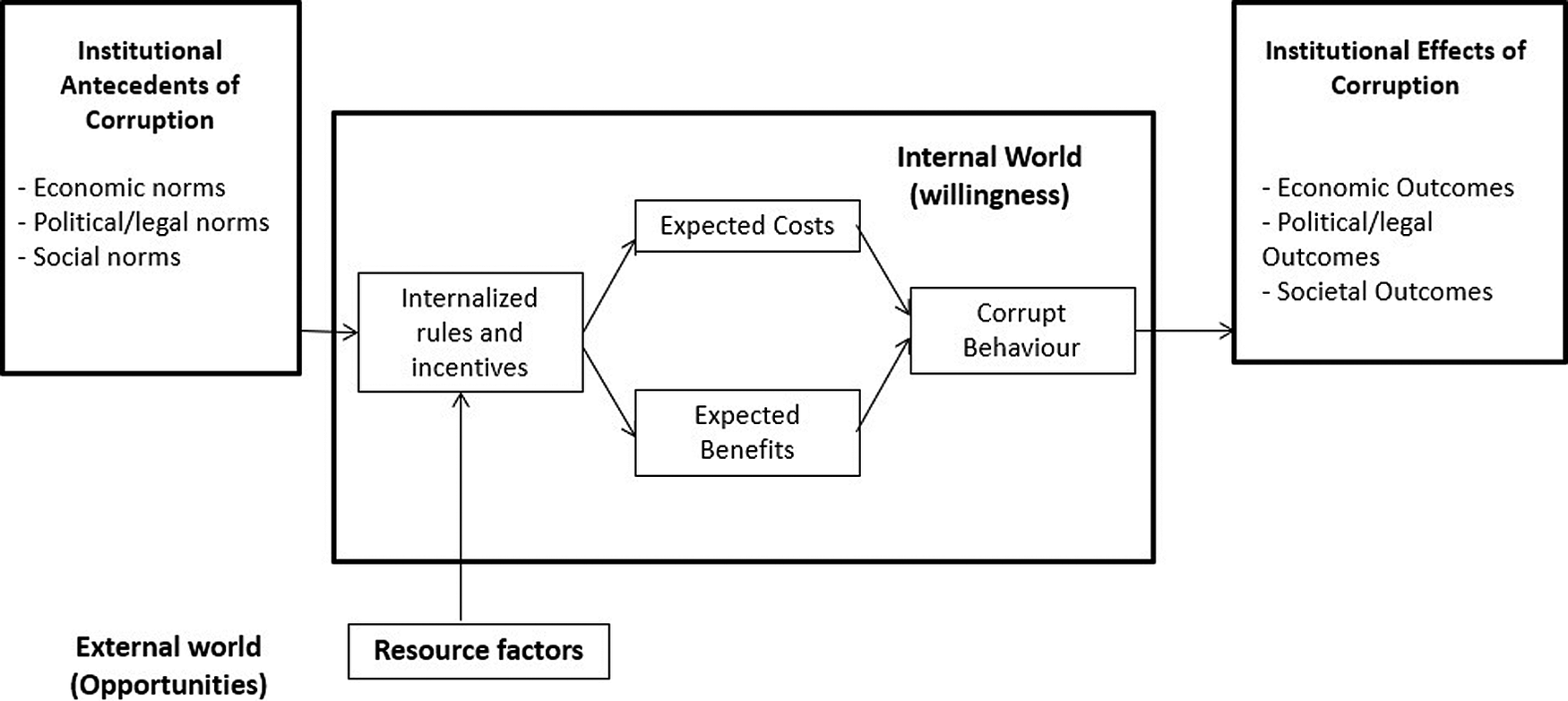

CICAF is an interdisciplinary proposal to understand corruption. It is assumed that corruption is a phenomenon that takes place in institutions (or tangentially to them) and that can be explained by assessing an individual decision restricted by various political, economic and cultural factors (Collier, Reference Collier2002). CICAF is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Corruption Institutional Choice Analytic Frame (adapted from Collier, Reference Collier2002).

As can be seen in Figure 2, CICAF proposes “two worlds” for the understanding of corruption. An “internal world”, referring to the micro-level of analysis, that includes the individual decision-making process to act in a corrupt manner. Analysis of this “world” is influence by typical economic models (see Becker, Reference Becker1968), seeing that the author considers that decision-making is based on the deliberative assessment of the cost-benefit expectations of the action. If the expectation of benefits is greater than the expectation of costs, there is a greater probability the action will take place (Collier, Reference Collier2002).

Nevertheless, according to the author, this individual decision-making process is related to the “external world”. The individual decision is influenced by political, economic, and sociocultural norms that exist in the individual’s “external world”. In this “world”, aside from the corrupt behavior predictors, is where the main economic, political and social corruption consequences can be found. If the corrupt actions were legitimated instead of punished (Collier, Reference Collier2002), these consequences, in turn, result in the creation of new norms, thus contributing towards the emergence of a “culture of corruption”.

Although CICAF allows for some progress to be made by proposing an interdisciplinary perspective, its approach is open to criticism. In the “internal world”, the author presents a decision-making model based on the cost-benefit models that are typical in economics. Various studies focusing on the decision-making process in finance (Kahneman & Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979), as well as research into dishonesty (Mazar & Ariely, Reference Mazar and Ariely2006), all point to that approach as being restrictive, seeing that there are various biases that interfere with the decision-making process that surpass a deliberate choice between cost and benefit expectations. Another element that may be criticized is the “inner” and “outer” dichotomy as a basis to explain behavior. There is a tradition in psychology literature that seeks to understand behavior based on different levels of analysis (Doise, Reference Doise1980), taking into account biological, cultural and interpersonal factors, overcoming a dichotomy between the individual and society. Furthermore, the restrictive “internal world” and “external world” proposal does not take into account, for example, the influence of groups on behavior, which has been systematically studied under the scope of social psychology. Another limitation of the model is that the concept of abuse of power, essential to the concept of corruption, is not included in the understanding of the phenomenon.

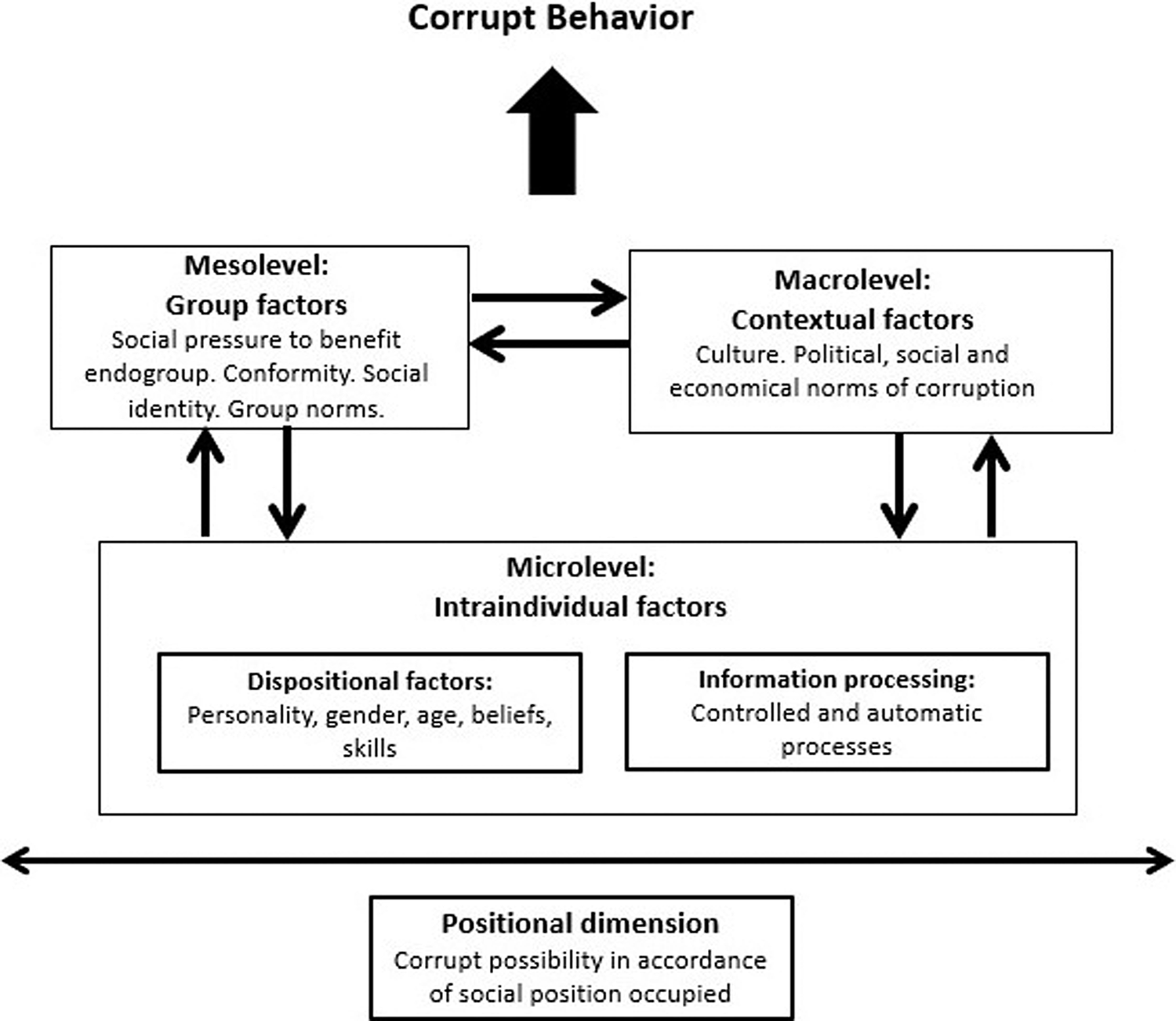

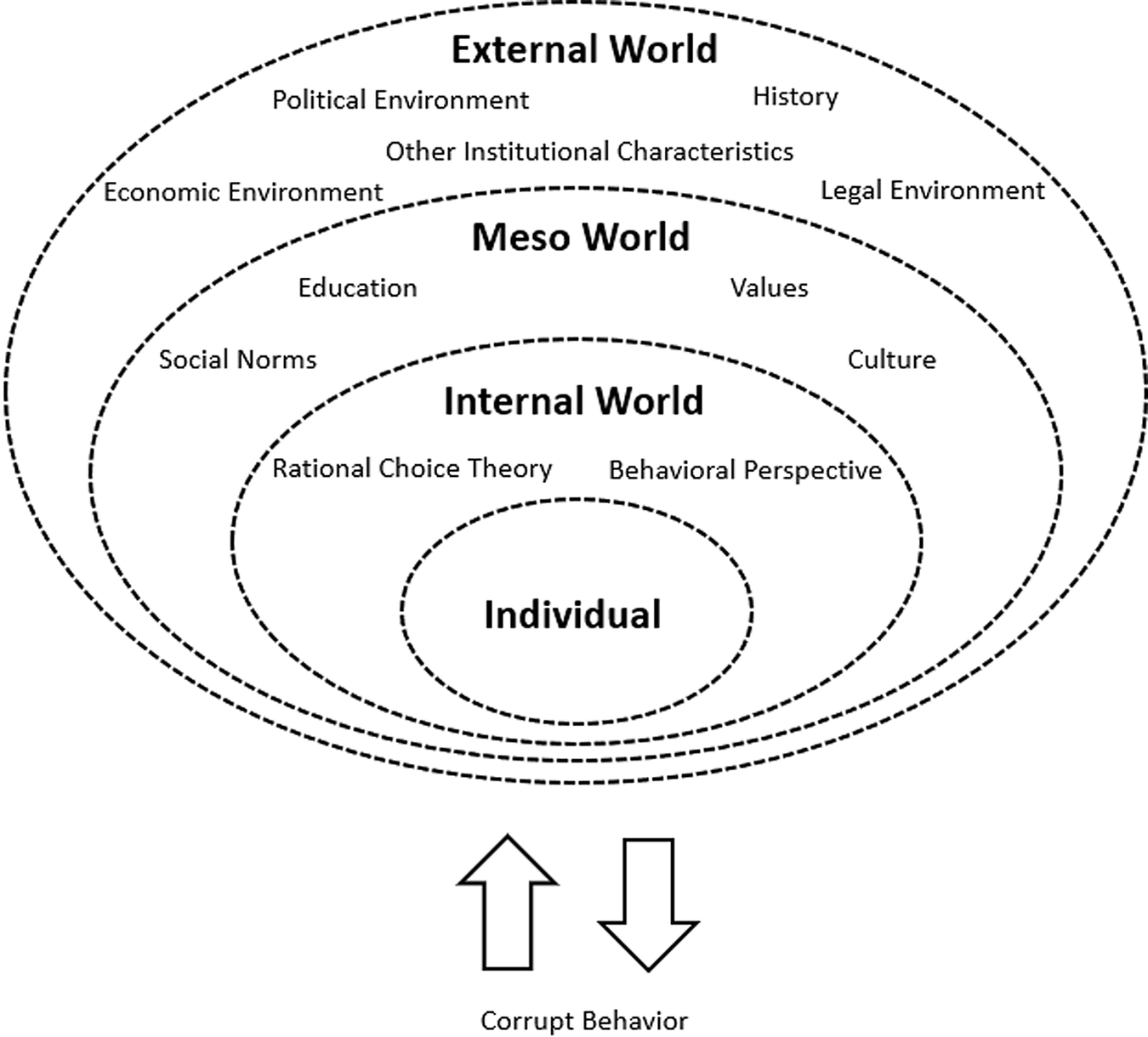

Aside from CICAF, Dimant and Schulte (Reference Dimant and Schulte2016) also propose an interdisciplinary perspective to analyze corruption. Notwithstanding the “external world” and “internal world”, also discussed in CICAF, the authors point to the existence of a “meso world”. Despite the inclusion of this dimension, according to Dimant and Schulte (Reference Dimant and Schulte2016), the proposal should be seen as an “inner-to-outer-world approach” (p. 58). It should be noted that, although terminology more closely related to the typical debate regarding levels of analysis is used, the authors also seem to analyze behavior from an internal-external dichotomy perspective. Despite this criticism, the proposal favors the understanding of corrupt behavior in an interdisciplinary and, to some extent, multilevel manner. Figure 3 shows the proposed perspective.

Figure 3. Interdisciplinary Perspective of Corruption (adapted from Dimant & Schulte, Reference Dimant and Schulte2016).

According to Dimant and Schulte (Reference Dimant and Schulte2016), the “internal world”, aside from taking into account rational decision-making processes, also considers a “behavioral perspective” that, according to the theoretical framework of behavioral economics, favors the analysis of less deliberate corruption processes. On this subject, we can see progress when compared to CICAF, insofar that less conscious processes are included in the proposal. It can, therefore, be construed that corrupt actions are not as completely rational and deliberate as presumed in the traditional economics “homo economicus” that supports CICAF.

On the other hand, in the “meso world”, Dimant and Schulte (Reference Dimant and Schulte2016) point to the importance of evaluating criminal and social factors, such as social norms, values, culture and education. The authors argue that the “meso world” analyses social interaction, however, the description provided involves, to a greater extent, the variables commonly referred to in social psychology as macro variables (an example of which is culture). Although social interaction is mentioned, the role played by groups is not highlighted in this dimension proposed by the authors. As such, the “meso world” is thus considered to be just another extension of the “external world” rather than an analysis of social interaction and group processes.

Regarding the “external world”, extrinsic factors that may influence corruption are considered. Dimant and Schulte (Reference Dimant and Schulte2016) focus on history, geography, economics, politics and legal aspects as factors to be considered in this dimension. For example, the effects of bureaucratic structures, the role played by political and legal institutions, and even the repercussions of colonization on corruption are analyzed. This dimension, conceptually, is related to the “external world” of CICAF.

Although more complete than CICAF, and showing significant improvement such as the consideration of less rational and deliberate processes, the proposal undertaken by Dimant and Schulte (Reference Dimant and Schulte2016) has limitations. In spite of the term “meso world”, its description does not seem to focus on group processes, appearing more to be an extension of the “external world” rather than a specific dimension to analyze the impact of groups on corrupt behavior. Additionally, the authors, although seeking to understand the phenomenon by means of levels of analysis, to a certain extent still seem to treat the phenomenon as an internal-external dichotomy, seeing that they define the “external world” as the location for the “extrinsic opportunities” (p. 66) of the individual, as well as stating that the proposal should be seen as an “inner-to-outer-world approach” (p. 58). Furthermore, as in CICAF, there doesn’t seem to be any concern in indicating that the notion of abuse of power is essential to the understanding of corruption.

Seeing that corruption is a procedural and systemic phenomenon, by which its understanding cannot be restricted to an “internal world” and “external world” dichotomy, Ashforth et al. (Reference Ashforth, Gioia, Robinson and Treviño2008) propose that corruption be investigated, at organizational level, according to five views: Micro view, macro view, wide view, long view, and deep view.

The micro view refers to an analysis of individual processes, such as demographic variables and dispositional factors that explain corrupt behavior. The authors, contrary to CICAF, highlight the existence of biases in individual decision-making as an important element towards the understanding of corruption. Ashforth et al. (Reference Ashforth, Gioia, Robinson and Treviño2008) further argue that an exclusively intraindividual analysis would favor the simplistic understanding that removing “the bad apples” would be enough to end corruption. However, the other levels of analysis indicate that the phenomenon, and consequently the fight against it, tends to be more complex.

In the macro view, it is assumed that the organizational context may contribute towards corruption, insofar as social norms exist that are capable of creating corrupt organizations that reach beyond the individuals that constitute them. For example, organizations may create objectives that are difficult to achieve by honest means and that, in conjunction with a culture of strong competitiveness, may favor corrupt practices. The macro-level also includes, according to the authors, studies that assess national and international corruption indexes.

Seeing that corruption widely affects the social system, Ashforth et al. (Reference Ashforth, Gioia, Robinson and Treviño2008) propose that corruption also be studied from a wider perspective consisting, for example, the understanding of the supply and demand of corrupt actions. After all, where there are corrupted, there are corruptors and a more extensive system that favors the existence of these social roles.

For Ashforth et al. (Reference Ashforth, Gioia, Robinson and Treviño2008), researching corruption from a long-term view means understanding that corruption is an old phenomenon, by which it is necessary to consider its historical factors. Finally, corruption can also be researched from a deep view, which means assuming an interdisciplinary proposal that includes contributions from different areas.

Analytical Model of Corruption

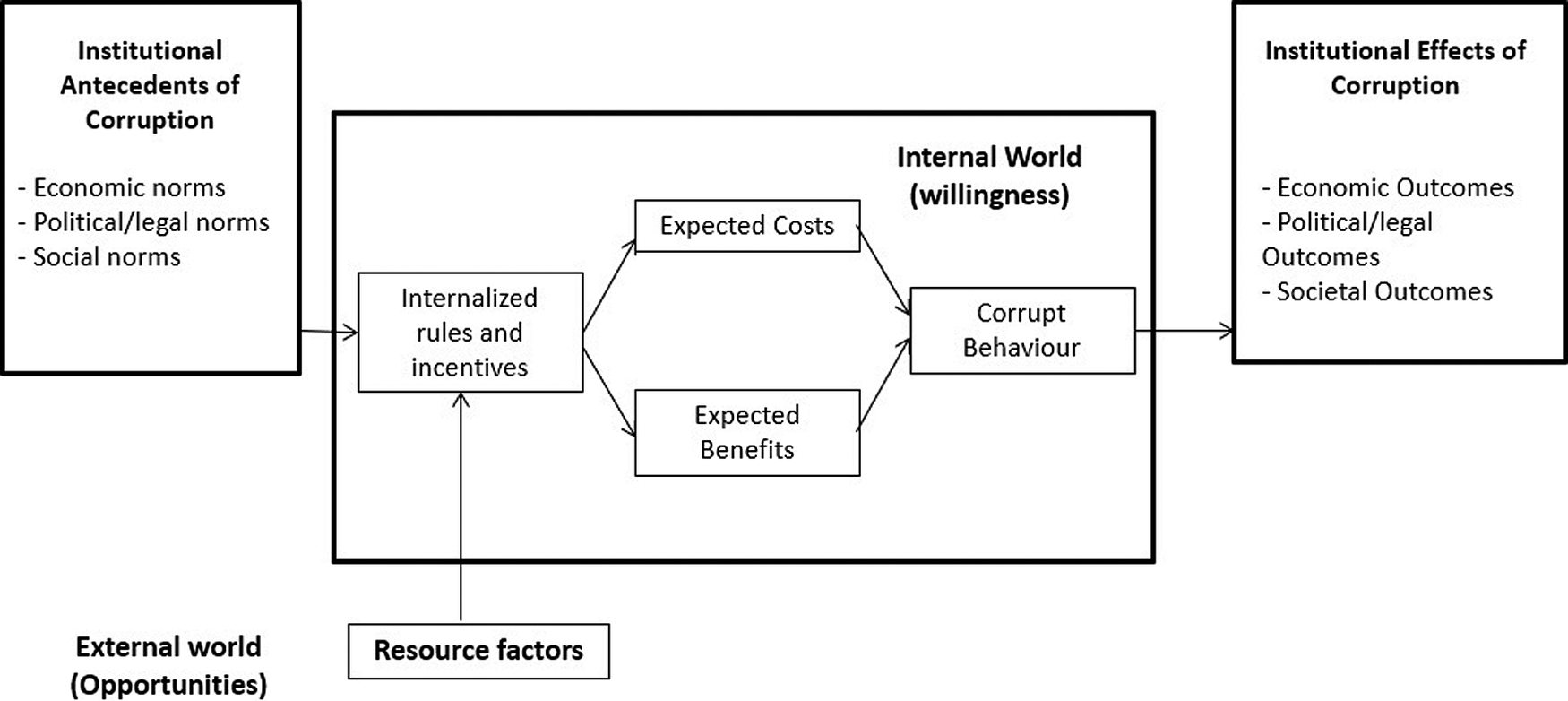

Considering the lack of theoretical perspectives to guide the study of corruption in an interdisciplinary manner (Judge et al., Reference Judge, McNatt and Xu2011), as well as the importance of understanding the psychosocial processes necessary for appropriate research of corruption (Zaloznaya, Reference Zaloznaya2014), we hereby propose the Analytical Model of Corruption (AMC) that takes into account the various views that should be considered when studying this subject (Ashforth et al., Reference Ashforth, Gioia, Robinson and Treviño2008) as well as concern in linking levels of analysis (Dimant & Schulte, Reference Dimant and Schulte2016). The model can be seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4. The Multilevel Analytical Model of Corruption.

According to the definition endorsed in the present theoretical study, corruption should be construed as the abuse of power for illegal gains (Andersson & Heywood, Reference Andersson and Heywood2009). In light of this understanding, the analysis of corrupt behavior should begin by looking at the positional dimension, which includes the opportunity to undertake an action due to the position occupied by the individual. It should be noted that this concern with the notion of position of power does not seem to have been included in previous models found in the literature and is, nevertheless, an essential aspect of the AMC.

Positional Dimension

Once in a position of power, potential corruption situations may occur by which the individual may, or may not, act in a corrupt manner. Taking the positional dimension into account, therefore, means accepting that the position an individual occupies in a particular case, within a certain context, is relevant to the analysis of psychosocial processes (Pereira & Araújo, Reference Pereira, Araújo and Keith2013). For example, in the case of corruption, the differences and similarities between processes that interfere in the corrupt act may be tested when evaluating the corrupted (someone in a position of power that allow themselves to be corrupted) and the corruptor (individual that benefits from the illegal actions of the corrupted). In some studies, this difference has already been considered at the time the scenarios being researched are elaborated (Bai et al., Reference Bai, Liu and Kou2016), pointing to the existence of possible specific psychosocial processes for understanding corrupt behavior when analyzing the various positions occupied. Another aspect in the analysis of this phenomenon, taking into account the positional dimension, involves researching to what level power itself, inherent to the position occupied, is capable of specifically favoring corrupt acts, as well as antisocial practices in general. In this regard, there is evidence that power may favor behavior aimed at obtaining personal gains. However, this effect tends to occur among individuals with low moral identity (DeCelles et al., Reference DeCelles, DeRue, Margolis and Ceranic2012). It can also be seen that in circumstances where power is perceived to be a way of influencing others, the position of power may favor higher levels of aggressiveness and exploitation towards subordinates (Cislak et al., Reference Cislak, Cichocka, Wojcik and Frankowska2018).

It is important to note that, although the analysis of the positional dimension is considered to be the “gateway” to understanding corrupt behavior, it should be considered as a common factor between all dimensions of the model (as indicated by the two-way arrows in the image). For example, when personality traits and their impact on corruption are analyzed, we recommend that this impact be researched taking into account the position of the corrupted and the corruptor. This is also valid for the group dimension: Will group impact will be similar when the situation involves corrupted when compared to corruptors? We believe that the positional dimension will offer greater clarity to corruption predictors, which represents an important advantage of the AMC over previous models.

Micro-level: Intraindividual Aspects of Corruption

After understanding the positional dimension, let's analyze the AMC intraindividual factors (micro-level) which consist of elements that are equivalent to the micro view of Ashforth et al. (Reference Ashforth, Gioia, Robinson and Treviño2008) and the internal world of CICAF (Collier, Reference Collier2002) and Dimant and Schulte (Reference Dimant and Schulte2016). In this dimension, we propose that individual characteristics (dispositional traits) be analyzed, together with the understanding of the mechanisms by which persons evaluate a potential corruption situation (information processing).

Regarding individual characteristics, an element that is commonly investigated is gender. There is evidence that women are less corrupt than men (Breen et al., Reference Breen, Gillanders, Mcnulty and Suzuki2017; Swamy et al., Reference Swamy, Knack, Lee and Azfar2001). According to the lower indexes of corruption identified in certain studies, some authors, and even the World Bank, suggest that the presence of women in positions of power would be a good strategy for better governance and a better approach to the fight against corruption (Swamy et al., Reference Swamy, Knack, Lee and Azfar2001; World Bank, 2001). Not only researchers, but also the general population seem to agree that women in power may contribute towards the fight against corruption, especially because of the belief that women are more averse to risk, aside from being considered as outsiders in politics (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Beaulieu and Saxton2018). However, when analyzing gender together with the opportunity for corruption in the public sector, facts do not seem to be enough to state that women are effectively less corrupt (Alhassan-Alolo, Reference Alhassan-Alolo2007). In truth, it can be argued that governments that have more women in positions of power are only less corrupt due to a liberal democracy that favors their election, and that, in truth, its liberal democracy itself that is associated with lower corruption indices (Sung, Reference Sung2003). Research on gender seems to point towards the need to identify moderators for the relationship between gender and corruption, as well as if more “typical” forms of corruption exist when taking gender into account.

Aside from gender, other individual characteristics may be evaluated to understand the dispositional factors of corruption. In a research paper on white-collar crime, it was found that those who committed a crime showed higher indices of hedonism, narcissism and conscientiousness, and lower indices of self-control (Blickle et al., Reference Blickle, Schlegel, Fassbender and Klein2006). White-collar criminals also seem to have lower indices of social consciousness when compared to an individual in a position of power that did not commit the same crimes (Collins & Schmidt, Reference Collins and Schmidt2006).

Still, regarding intraindividual factors, researchers have also evaluated the just world beliefs as predictors of corruption. It was found that a greater perception of justice, based on the belief of a just world, was associated with lower intention of corruption indices (Bai et al., Reference Bai, Liu and Kou2016).

Despite evidence originating from specific research on corruption, results from unethical behavior and dishonesty studies that point to possible variables relevant to understanding corrupt behavior may also be considered (see Lehnert et al., Reference Lehnert, Park and Singh2015; Treviño et al., Reference Treviño, Weaver and Reynolds2006). It can be seen that, for example, the lower an individual’s moral cognitive development, the greater the probability they will behave unethically (Knoll et al., Reference Knoll, Lord, Petersen and Weigelt2016), where individual differences in the perception of guilt moderate that relationship (Johnson & Connelly, Reference Johnson and Connelly2016).

Aside from the referred dispositional factors, some research has also attempted to identify the skills of a dishonest person. For example, there is evidence that more creative people have higher indices of dishonest behavior (Gino & Ariely, Reference Gino and Ariely2012). According to the authors, creative people have a greater capacity to justify their actions, thus increasing their chances of behaving dishonestly.

Together with research on individual characteristics, the AMC micro-level assumes that it is important to analyze how information relating to a potential corrupt act is processed and, consequently, how it influences decision-making. Based on the tradition of research into the dual process model of information processing (Evans & Stanovich, Reference Evans and Stanovich2013), the AMC foresees that a corrupt action may be governed by controlled and/or automatic processes. In this aspect, the AMC is aligned with research into moral cognition that has been used to analyze to what extent behavior for personal gain is more intuitive or deliberate (Hallsson et al., Reference Hallsson, Siebner and Hulme2018).

There is evidence suggesting that, in situations where an individual has sufficient time and cognitive resources to make a careful decision, the controlled processes will prevail (Evans & Stanovich, Reference Evans and Stanovich2013). In such a case, an individual can carefully analyze the risks and benefits of a corrupt act. This understanding is consistent with what is posited by CICAF, and the decision-making cost-benefit models in general. Based specifically on the General Theory of Crime (Becker, Reference Becker1968), it is expected that, among other factors, when making a rational decision, the individual assesses the gains that may be obtained by corruption in comparison to those obtained by legal means; the risks of being found out and punished; as well as the degree of punishment should he/she be found out. In this sense, there is evidence that greater perception of the risk will decrease the intention of acting corruptly (Bai et al., Reference Bai, Liu and Kou2016).

In addition to the risks and benefits analysis, a more controlled and conscious process may favor dishonest practices according to the use of justifications that legitimate the behavior. In situations where the individual can justify his/her actions as “legal” or by considering them as broader moral benefits (Gino & Pierce, Reference Gino and Pierce2009) it is more probable that the dishonest behavior will occur. According to the Theory of Self-concept Maintenance, the use of justifications is favorable since the individual keeps the external rewards obtained through dishonesty and at the same time they reduce the intrinsic discomfort of having acted dishonestly (Mazar et al., Reference Mazar, Amir and Ariely2008).

Although it is relevant to evaluate the variables linked to a more deliberate and controlled process, the decision in a political or economic scope is not always conscious as assumed in the cost-benefit models. There is evidence that our rational capacity is limited during the financial decision-making process (Kahneman & Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979), and on certain occasions may contribute with more intuitive and automated decisions. Although efficient in many circumstances, automatic processes may be associated with errors in judgment and perception, seeing that, for example, people do not always have the capacity to perceive a certain situation as unethical as they lack the cognitive resources for a more systematic evaluation (Darley, Reference Darley2005), or the individual may not have been capable of deliberately applying self-control due to psychological exhaustion (Mead et al., Reference Mead, Baumeister, Gino, Schweitzer and Ariely2009).

Another important aspect regarding automatic processes in corruption evaluation involves the analysis of cognitive biases. Loss aversion, for example, is considered to be a cognitive bias that may favor the occurrence of automated dishonest decision-making (Schindler & Pfattheicher, Reference Schindler and Pfattheicher2017). Individuals, due to loss aversion, will be more inclined to act dishonestly to avoid financial loss.

Furthermore, when processing information, emphasis should be placed on the importance of emotions when analyzing decision-making in risk situations (Reyna, Reference Reyna2004). More specifically, regarding dishonesty, there is evidence that individuals that act dishonestly tend to gradually escalate their dishonest actions seeing that repeated exposure to these actions influences the amygdala, a region of the brain that is directly linked to emotions (Garrett, Lazzaro, Ariely, & Sharot, Reference Garrett, Lazzaro, Ariely and Sharot2016). In this sense, according to the authors, repeated exposure to dishonest actions reduces emotional response to those same actions, which may favor an increase in dishonesty. Other studies also point to a relationship between the amygdala and immoral acts (Shenhav & Greene, Reference Shenhav and Greene2014), which restates the importance of emotions in the processing of information and decision-making in the broader scope of unethical behavior.

The intraindividual process dimension of the AMC proposes that cognitive processes should be evaluated, and not only the demographic and dispositional variables, which may be predictors of corrupt decision-making. It is necessary to understand which factors influence corrupt behavior when an automatic process prevails and when the controlled processing of information prevails. It is also necessary to understand how dispositional variables influence the types of cognitive processing, and as a result of this produce a model that includes intraindividual factors as the antecedents of corrupt behavior.

Meso level: Group Processes and Corruption

The group process dimension is related to the intraindividual dimension and refers to the meso-level of analysis. At this level, it is possible to investigate the role played by groups in corrupt decisions, which is something that has been neglected in empirical research and previous theoretical models, as has already been mentioned.

Concerning the role of groups, some researchers consider the possibility (Schikora, Reference Schikora2011) that the existence of groups inhibits corrupt behavior. This understanding favored the development of the Four Eyes Principle (4EP), which posits that a corrupt individual will be less inclined to act dishonestly in front of other people. Thus, the name “four eyes”, indicating the existence of “more eyes” would favor inspecting and the inhibition of corrupt behavior. Although intuitive, there is evidence that 4EP is not efficient (Schikora, Reference Schikora2011). Some phenomena typically researched under the scope of social psychology contribute towards the understanding of the non-effectiveness of 4EP.

One of the group processes that helps in understanding the reason behind the non-effectiveness of 4EP is social influence. In cases where a strong group identity exists and one of the members of the group acts dishonestly, that could create a group norm and cause the other members of the group to also act dishonestly (Gino et al., Reference Gino, Ayal and Ariely2009). Furthermore, under circumstances where it is possible to act dishonestly under the pretext of increased benefits for the group, there is a greater probability of dishonesty taking place (Gino et al., Reference Gino, Ayal and Ariely2013; Gino & Pierce, Reference Gino and Pierce2009). In other words, the group may, under certain circumstances, contribute towards dishonest behavior instead of inhibiting it.

Group influence is one of the ways of understanding what drives an individual to act dishonestly. According to the Social Identity Theory (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1981), we have various social identities according to the groups we integrate. In light of this, an individual may have a moral personal identity and still act in a corrupt manner in certain situations based on other identities that are called upon depending on the context and the group in question (Darley, Reference Darley2005).

As such, the AMC meso-level allows group corruption processes to be investigated. In that respect, a research design that compares individual and group decisions, studies that evaluate pressure to conform, intergroup bias, among other group processes that fall under the scope of corruption, can be developed. A specific line of research into this dimension is important, considering that many corrupt actions take place within the context of groups and teams, as is the case of organizations and politics.

Macro-level: Contextual Aspects of Corruption

There is a proximity of the AMC macro-level to the external world of CICAF, to the meso and external world of Dimant and Schulte (Reference Dimant and Schulte2016), as well as to the macro and long-term view of Ashforth et al. (Reference Ashforth, Gioia, Robinson and Treviño2008), to the extent that it gives context to the contextual factors of corruption. Based on a more advanced stage of economics in the study of the phenomenon (when compared to social psychology), the greatest body of evidence can be found in the contextual factors dimension, relating to the causes and consequences of corruption (Tanzi, Reference Tanzi1998), considering the proposed distinction between corruption, unethical behavior and dishonest behavior. One can highlight, for example, how the political and economic system and cultural aspect influence corrupt practices.

Concerning the political system, there is evidence that a democratic government is associated with lower indices of corruption (Pellegrini, Reference Pellegrini2011). It can, however, be seen, that this effect tends to occur in more consolidated democracies, with democratically elected governments that have been in power during a minimum uninterrupted period of 10 years for the impact on corruption to be perceived. One of the ways to understand these findings is that, in mature democracies, there is an expectation that corrupt politicians are not get re-elected, which, consequently, would reduce the general corruption indices of the country. Additionally, the impact democracy has in reducing corruption tends to occur only in countries where the per capita Gross Domestic Product is approximately more than 2,000 dollars. In countries that fall below this level, democratization does not reduce corruption insofar as it arises as an opportunity to obtain more concrete gains in light of the economic situation of the country (Jetter et al., Reference Jetter, Montoya Agudelo and Ramírez Hassan2015).

Aside from the direct effect of economy, there is evidence of interaction between a democratic system and a liberal economic model with regards to the reduction of corruption (Saha et al., Reference Saha, Gounder and Su2009), seeing that a liberal structure would reduce the opportunity public agents have of obtaining gains by means of kickbacks and bribes. Nevertheless, this data should be analyzed with caution considering that there is evidence that competitiveness, which is typical of a liberal economic model, may favor corruption (Søreide, Reference Søreide2009).

In addition to the analysis of political and economic models, commonly investigated within the field of political science and economics, it is important to understand the impact culture has on corruption. Based on Hostede’s Model (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede1980), various studies have focused on the impact of the model’s cultural dimensions on corruption, especially with regards to the individualism-collectivism, power distance, masculinity-femininity, and uncertainty avoidance dimensions.

The individualism/collectivism dimension applies to the understanding of the relationship pattern of the individuals with the groups to which they belong. In societies with higher indices of individualism, there is a greater tendency for individuals to establish personal goals and to consider themselves to be responsible for their actions. There is also an understanding, as opposed to countries with higher indices of collectivism, that rules and laws should apply in general to the whole of society, and not vary for the benefit of certain groups. Based on the understanding that laws apply to everyone, aside from the fact that collectivist societies tend to prioritize informal relationships (which may contribute towards personal advantages such as corruption), various studies have shown that countries with higher indices of individualism tend to have lower levels of corruption (Davis & Ruhe, Reference Davis and Ruhe2003; Jha & Panda, Reference Jha and Panda2017; Yeganeh, Reference Yeganeh2014).

The power distance dimension refers to the degree to which people accept the fact that power is unevenly distributed. We are thus dealing with the acceptance of the hierarchy of social structures as if it were a natural and “unchangeable” process. Therefore, higher indices of power distance tend to be related to higher indices of corruption (Soeharto & Nugroho, Reference Soeharto and Nugroho2018) seeing that, based on structured hierarchies, it will not be likely that individuals will oppose the behavior of those in power (even if this behavior is corrupt). Aside from this, greater power distance favors the exchange of favors, kickbacks and bribes by those in power in detriment of those who it is unlikely will have access to those positions (Davis & Ruhe, Reference Davis and Ruhe2003; Yeganeh, Reference Yeganeh2014). Nevertheless, there is evidence of a positive relationship between the power distance levels of a country and the perceived degree of reputation of its organizations (Deephouse et al., Reference Deephouse, Newburry and Soleimani2016).

The masculinity-femininity dimension involves the evaluation of aspects such as the degree of competitiveness and obtaining material rewards in detriment of cooperation and quality of life. The higher the masculinity index, the greater the competitiveness and materialism, while higher levels of femininity are associated with being careful and cooperative. In masculine cultures success and money are thus prioritized, which favors its association with corruption (Davis & Ruhe, Reference Davis and Ruhe2003; Yeganeh, Reference Yeganeh2014).

The uncertainty avoidance dimension deals with the cultural aspect, which involves the degree to which people in certain places are tolerant of the fact that the future is unpredictable. Countries with higher indices of uncertainty avoidance tend to seek out ways of “control” that allow for greater predictability in the world. In light of this, the development of bureaucratic structures that favor corruption is observed (Davis & Ruhe, Reference Davis and Ruhe2003). Furthermore, corruption can be seen as being safer in such a context, providing immediate rewards and guarantees, which also helps to understand the relationship between this cultural dimension and corrupt practices (Park, Reference Park2003).

Still at a macro level, aside from culture, another variable of interest to social psychology that contributes towards the understanding of corrupt behavior is the social norm. Despite the limitations already discussed regarding CICAF (Collier, Reference Collier2002), the impact of the social, political and economic norms on corruption was already explicitly shown in the model, to the extent that the norms, especially descriptive norms, guide the behavior according to the context. In this regard, it can be seen that descriptive norms influence the intention of corruption, by which this relationship is partially mediated by the level of moral disengagement of the individual (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Zhang and Xu2019). According to the authors, descriptive norms tend to indicate that acting in a corrupt manner is something normal within that context. This understanding activates moral disengagement mechanisms that serve to justify and legitimate a corrupt act.

The macro level, therefore, favors the understanding of contextual factors of corruption. On this level, studies can be developed to compare different political and economic models and their impact on corruption. How corruption is expressed (i.e.: Cronyism, bribery, white-collar crime) within different cultural contexts may also be analyzed, in order to identify whether or not more typical forms of expression exist depending on the culture. Furthermore, from a macro perspective, it is essential to undertake studies that analyze the repercussions of corruption. The analysis of this dimension, to the extent found in literature, has been privileged by researchers, especially when research in economics and political science was taken into account, and was included in the AMC multilevel proposal.

Concluding remarks

The objective of this work was to propose the Analytical Model of Corruption as a multilevel model for interdisciplinary research. The main advantages of the AMC, when compared with the few previous models found in literature, are that its structure is based on a clear definition of corruption that, in that sense, take into account the importance of analyzing the positional dimension to understand corruption. Moreover, contrary to previous models, it highlights the role played by groups in corruption, which is an aspect that was neglected in other models.

It is also important to emphasize the multilevel aspect of the AMC. Despite the distinction made between the positional, micro, meso and macro dimensions, the model proposes a mutual interaction between them. As such, it is foreseen in the model that an individual in a position of power should make decisions. The tendency to make a corrupt decision is influenced by dispositional factors, as well as by how a situation is evaluated. Should it be evaluated in a rational and deliberate manner, if the benefits outweigh the risks, it is more likely that the corrupt behavior will take place. When automatic processes prevail, some biases also tend to favor corrupt behavior, as is the case with loss aversion. However, this decision is limited by group and contextual factors. The presence of a group may inhibit corrupt behavior, as long as the group has norms to prevent corrupt behavior and some level of group identity exists. However, if the group has norms that induce corrupt behavior, the presence of more individuals may favor corruption. This interaction is also influenced by contextual factors. Social, political and economic, as well as cultural norms will influence the tendency to behave corruptly. Even though the context does not favor corrupt behavior, excuses may be used to justify the behavior, breaking with the social norm. Based on the interactive nature of the AMC, despite the influence of groups and contextual factors on individual behavior, individuals also influence group and contextual dynamics. A single individual is capable of influencing an entire group, a typical process in the phenomenon of leadership (see Tanzi, Reference Tanzi1998, regarding how the role of a leader may be an example to prevent corrupt behavior). Additionally, various corrupt individual behaviors, if they go unpunished, may gradually become the norm, thus creating a “culture of corruption”. This perspective of interaction favors the AMC to be used as a structure that could guide interdisciplinary studies, which is essential for a comprehensive and efficient analysis of the antecedents of corruption (Ashforth et al., Reference Ashforth, Gioia, Robinson and Treviño2008; Judge et al., Reference Judge, McNatt and Xu2011).

The AMC was not developed with the intent to exhaust the relevant variable set used to understand corrupt behavior. Its purpose is to help guide and organize large sets of variables relating to corruption and dishonest behavior antecedents. As already mentioned, it is based on a multilevel premise and on the understanding of the multideterminism of human behavior, the analysis of factors in isolated levels of analysis is not sufficient to fully understand corrupt behavior. As such, the AMC proposes an organizational structure that serves as a means for researchers and professionals interested in fighting and preventing corruption to develop strategies aimed at understanding the factors and variables of specific situations or, otherwise, develop strategies to prevent and mitigate undesirable conduct related with dishonesty. Thus, the AMC proves to be, from a multilevel standpoint, as a useful contributor to the fields of expertise of various professionals, such as lawyers, political scientists, sociologists, economists and psychologists that are involved in researching, preventing and fighting corruption.