Worry is a relatively normal cognitive process in the general population (Tallis, Davey, & Capuzzo, Reference Tallis, Davey, Capuzzo, Davey and Tallis1994), but it becomes problematic in people with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) because they experience worry with greater frequency, intensity and persistence. In recent years, research on GAD has focused on analysing the factors that explain pathological worry, with cognitive models playing an important role (for a review, see Behar, DiMarco, Hekler, Mohlman, & Staples, Reference Behar, DiMarco, Hekler, Mohlman and Staples2009). Among these, the metacognitive model of GAD (Wells, Reference Wells1999; Reference Wells2000; Reference Wells2005) has received significant attention.

Metacognition refers to stable knowledge or beliefs about one´s own cognitive system, knowledge about factors that affect the functioning of the system, regulation and awareness of the current state of cognition, and appraisal of the significance of thought and memories (Wells, Reference Wells1995, p. 302). This top-down conceptualisation suggests that metacognitive beliefs guide the selection of worry as a coping strategy and lead to negative appraisals of worry, termed meta-worry (Wells, Reference Wells2000). The metacognitive model of GAD, which is based on a broader model of emotional disorders called the self-regulatory executive function (S-REF, Wells & Matthews, 1994), proposes that repetitive, uncontrollable worry in GAD is linked to an individual’s metacognitive beliefs about worrying (Wells, Reference Wells2005). For example, when faced with an anxiety-provoking stimulus, individuals having positive beliefs about worry (e.g., “Worry will help me cope”) are prone to use worry as a predominant means of coping. If, during the course of worry, negative beliefs about worry are activated (e.g., “Worry is uncontrollable”, “My worrying is dangerous for me”), individuals engage in negative appraisals about worry, or meta-worry, that intensifies anxiety and maintains perseverative thinking (Wells, Reference Wells2005). These metacognitive beliefs form part of the information-processing system associated with GAD and with other emotional disorders. In fact, metacognitive beliefs and meta-worry are also associated with other processes that contribute to some emotional disorders, such as thought suppression or avoidance behaviours (e.g. avoidance of situations, reassurance-seeking, alcohol use). Thus, engaging in these ineffective strategies may lead people with GAD to see that worry is dangerous or uncontrollable.

To analyse individual differences in metacognitive beliefs and to test the hypotheses of the GAD model, Cartwright-Hatton and Wells (Reference Cartwright-Hatton and Wells1997) developed the Metacognitions Questionnaire (MCQ). This questionnaire consists of 65 items, with responses on a four-point Likert scale; higher scores indicate the presence of more dysfunctional metacognitive beliefs. Preliminary results with the MCQ showed a structure of five related factors (Cartwright-Hatton & Wells, Reference Cartwright-Hatton and Wells1997): (1) positive beliefs about worry, which measures the extent to which a person believes that worry is useful; (2) negative beliefs about concern, which measures the extent to which a person believes that worry is uncontrollable and dangerous; (3) cognitive confidence, which assesses confidence in one’s own attention and memory processes; (4) beliefs about the need for control, which assesses the need to control and/or delete some thoughts; and (5) cognitive self-awareness, which assesses the tendency to monitor attention to one’s thoughts. The MCQ showed adequate psychometric properties and the questionnaire subscales positively predicted worry proneness, intrusions, obsessional symptoms, and anxiety (Cartwright-Hatton & Wells, Reference Cartwright-Hatton and Wells1997).

More recently, in an effort to generate a shorter instrument, Wells and Cartwright-Hatton (Reference Wells and Cartwright-Hatton2004) developed the Meta-cognitions Questionnaire 30 (MCQ-30). Using a combination of criteria, in particular the factor loadings of the items on the original MCQ, six items were selected as representative of each of the five factors, resulting in a 30-item instrument. MCQ-30 showed evidence of a five-factor structure similar to that of the original scale, as well as adequate psychometric properties in different studies using confirmatory factor analyses and larger population samples (e.g., Spada, Mohiyeddini, & Wells, Reference Spada, Mohiyeddini and Wells2008; Wells & Cartwright-Hatton, Reference Wells and Cartwright-Hatton2004).

Consistent with the metacognitive model, the MCQ-30 subscales have been related to measures of trait anxiety, thought suppression and pathological worry (Wells, Reference Wells1995; Wells & Cartwright-Hatton, Reference Wells and Cartwright-Hatton2004); higher levels of anxiety and depression (Spada et al., Reference Spada, Mohiyeddini and Wells2008); and a greater tendency to engage in meta-worry (Davis & Valentiner, Reference Davis and Valentiner2000). MCQ-30 has also been shown to be a useful tool to differentiate patients with GAD from patients with other anxiety disorders and from the general population (Barahmand, Reference Barahmand2009; Wells & Carter, Reference Wells and Carter2001). Moreover, the questionnaire has been used with non-clinical populations to analyse the implications of metacognitive beliefs for other emotional disorders and psychological disturbances, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder (Fisher & Wells, Reference Fisher and Wells2008; Janeck, Calamari, Riemann, & Heffelfinger, Reference Janeck, Calamari, Riemann and Heffelfinger2003), posttraumatic stress disorder (Holeva & Tarrier, Reference Holeva and Tarrier2001), psychosis and hallucinations (Brett, Johns, Peters, & McGuire, Reference Brett, Johns, Peters and McGuire2009), substance abuse (Spada, Moneta, & Wells, Reference Spada, Moneta and Wells2007), and chronic fatigue syndrome (Maher-Edwards, Fernie, Murphy, Wells, & Spada, Reference Maher-Edwards, Fernie, Murphy, Wells and Spada2011).

Recent studies have confirmed the internal consistency and structure of the MCQ-30 in different non-English-speaking populations (Tosun & Irak, Reference Tosun and Irak2008; Typaldou et al., Reference Typaldou, Nidos, Roxanis, Dokianaki, Vaidakis and Papadimitriou2010). However, a Spanish version has not yet been validated or published, which poses an obstacle to advances in research. The present study sought to develop and validate a Spanish version of the MCQ-30 and test it on a non-clinical Spanish sample to confirm whether its factor structure, psychometric properties and relationships to other constructs are similar to those of the original scale. We also examined measurement invariance across gender. Specifically, we hoped to confirm the original intercorrelated five-factor structure (in both male and female), observe that the subscales have adequate internal consistency and temporal stability over 3 months, and probe the associations between the MCQ-30 and theoretically related variables such as pathological worry, meta-worry, thought suppression, trait anxiety, and other measures of beliefs about worry.

Method

Participants and procedure

A total of 768 participants from two nonclinical samples (31.1% males, 68.9% females), ranging in age from 16 to 81 (M = 31.82, SD = 13.03), completed the Spanish version of the MCQ-30. A subset of 518 participants (31.9% males, 68.1% females), selected using a snowball sampling procedure and ranging in age from 16 to 81 (M = 30.39, SD = 12.67), completed additional tests to evaluate pathological worry, meta-worry, thought suppression and trait anxiety. Another sample of 135 undergraduate students (11.1% males, 88.9% females), ranging in age from 19 to 34 (M = 21.62, SD = 2.38), completed the Spanish MCQ-30 and measures to evaluate beliefs about worry. Among these 135 students, a subset of 115 (8.7% males, 91.3% females), ranging in age from 19 to 29 (M = 21.36, SD = 1.97), completed the Spanish version of the MCQ-30 a second time, 3 months after the first administration. Participants were volunteers who received no credit for participation in the study. The questionnaires were administered in paper-and-pencil format and instructions were provided in writing.

Instruments

Meta-Cognitions Questionnaire-30 (MCQ-30; Wells & Cartwright-Hatton, 2004)

This measure assesses individual differences in metacognitive beliefs, judgments and monitoring tendencies. It comprises five subscales involving a total of 30 items. Responses to each item on the MCQ-30 are on a 4-point Likert scale, from 1 = “do not agree” to 4 = “strongly agree”. MCQ-30 scores range from 30 to 120 points, and higher scores indicate greater pathological metacognitive activity. The five subscales measure the following dimensions: (1) positive beliefs about worry (e.g. ‘‘worrying helps me cope”), (2) negative beliefs of uncontrollability and danger (e.g. ‘‘when I start worrying I cannot stop”), (3) cognitive confidence (e.g. ‘‘my memory can mislead me at times”), (4) need to control thoughts (e.g. ‘‘not being able to control my thoughts is a sign of weakness”), and (5) cognitive self-consciousness (e.g. ‘‘I pay close attention to the way my mind works”). The Spanish translation of the MCQ-30 was created using a back-translation procedure involving two independent translators, both of whom were psychologists and experts in GAD.

Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ; Meyer, Miller, Metzger, & Borkovec, 1990)

This was designed to capture the generality, excessiveness, and uncontrollability that are characteristic of pathological worry. The reliability and validity of the PSWQ have been widely researched, and the instrument appears to have sound psychometric properties (Molina & Borkovec, Reference Molina and Borkovec1994). It consists of 16 items, and responses are given on a 5-point scale from 1 = “nothing” to 5 = “a lot”. The original English version had five items, the order of which was inverted in the Spanish version (Nuevo, Montorio, & Ruiz, Reference Nuevo, Montorio and Ruiz2002). This version has a unidimensional structure and has shown good reliability, validity, and internal consistency. Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was .93.

Meta-Worry Questionnaire (MWQ; Wells, 2005)

This questionnaire assesses thoughts and ideas about worrying. The instrument consists of seven items reflecting dangers of worrying. The MWQ has two response subscales, one designed to assess the frequency of meta-worry and the other designed to assess the belief in each meta-worry. In this study we used only the frequency scale. Cronbach’s alpha for the frequency scale was .88 in the original study (Wells, Reference Wells2005) and slightly lower (.79) in the present work.

White Bear Suppression Inventory (WBSI; Wegner & Zanakos, 1994)

This inventory has 15 items that measure people’s general tendency to suppress thoughts; responses range from 1 = “totally disagree” to 5 = “completely agree”. It has shown good internal consistency (α = .89) and test-retest reliability (r = .80). The present study used the Spanish version of the WBSI (Fernández, Extremera, & Ramos, Reference Fernández, Extremera and Ramos2004), which has also shown adequate psychometric properties. In the present work, Cronbach’s alpha was .92.

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Spielberger, 1983)

The STAI is widely used to assess anxiety. The instrument is divided into two 20-item sections that assess state and trait anxiety; responses are on a 4-point Likert scale. Only the trait anxiety subscale was used in the present study. Scores on this subscale range from 20 to 80 points, with higher scores indicating greater anxiety. The Spanish version of the STAI has shown good psychometric properties (Spielberger, Gorsuch, & Luschene, Reference Spielberger, Gorsuch and Luschene1982), and Cronbach´s alpha in the present study was .91.

Why Worry? (WW; Freeston, Rhéaume, Letarte, Dugas, & Ladouceur, 1994)

This 20-item questionnaire identifies and assesses reasons why people say they worry about. The questionnaire has two subscales: (1) believe that worrying can prevent negative outcomes, (2) believe that worrying has positive effects, such as finding a better way of doing things, increasing control, and finding solutions. These scales showed good psychometric properties in both the original version (Freeston et al., Reference Freeston, Rhéaume, Letarte, Dugas and Ladouceur1994) and the Spanish adaptation (González, Bethencourt, Fumero, & Fernández, Reference González, Bethencourt, Fumero and Fernández2006). In the present study, Cronbach´s alpha for the two subscales was .51 and .85, respectively.

Data Analyses

The SPSS statistical package (version 19.0) was used to compute descriptive statistics, correlation analyses, and internal consistency. Pearson´s correlation was used to investigate the relationships between MCQ-30 and other measures. EQS 6.1 (Bentler, Reference Bentler1995) was used to perform confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using the maximum likelihood (ML) method. Since departures from multivariate normality can have a significant impact on maximum-likelihood estimation, we calculated descriptive analytical measures prior to conducting CFA analysis. Since univariate and multivariate kurtosis statistics were found to indicate non-normality, the Satorra-Bentler scaled ML correction was used to adjust the model chi-square (Hu, Bentler, & Kano, Reference Hu, Bentler and Kano1992). Given the sensitivity of the chi-square statistic to sample size (Floyd & Widaman, Reference Floyd and Widaman1995), the following additional measures of model fit were used (Schweizer, Reference Schweizer2010): the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the Bentler comparative fit index (CFI), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). CFI values above .90 indicate good fit. RMSEA values below .08 are considered a reasonable fit, whereas values below .05 indicate good fit. SRMR values are expected to be below .10 (Schweizer, Reference Schweizer2010).

Results

Factor structure and reliability

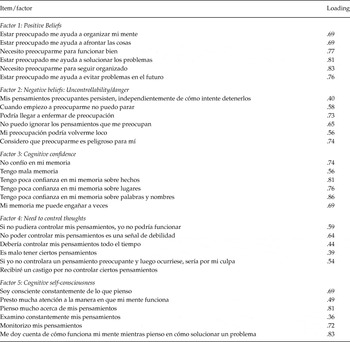

The hypothesized five factor model showed the following fit indices: S-B χ2 = 1005.86, df = 395, p = .001; normed χ2 (χ2/df) = 2.54; RMSEA = 0.04 (90% CI = 0.04–0.05); CFI = 0.92; SRMR = 0.05. Globally, these indices indicate a good fit to the data, showing that the five-factor model is acceptable. All factor loadings were higher than .35 (Table 1).

Table 1. MCQ-30 items and their standardised factor loadings (N = 768)

Note:

All factor loadings were significant at p < .05.

Cronbach’s alphas and correlations between the five factors and the total MCQ-30 score are shown in Table 2. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the subscales ranged from .69 (need to control thoughts) to .89 (positive beliefs about worry). The alpha coefficient for the total score was .89. These alpha coefficients were acceptable compared to the guideline of Cronbach´s alpha ≥ .70 for being acceptable (Nunnally & Bernstein, Reference Nunnally and Bernstein1994). As in previous studies (Spada et al., Reference Spada, Mohiyeddini and Wells2008), the lowest correlation was found between cognitive self-consciousness and cognitive confidence, whereas the highest correlation was found between negative beliefs of uncontrollability and danger and the need to control thoughts.

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, alpha reliabilities and correlations of the MCQ-30 subscales and total score (N = 768)

Note:

all correlations were significant at p < .01.

We also assessed reliability using test-retest correlation. Test-retest reliability over 3 months was acceptable for the majority of the subscales, r = .69 for positive beliefs about worry, r = .69 for negative beliefs about uncontrollability and danger, r = .86 for cognitive confidence, r = .66 for cognitive self-consciousness, and r = .72 for the total MCQ-30 score; however, it was quite low for the need to control thoughts subscale, r = .50.

Invariance across gender

When the five-factor model was explored across gender, the goodness-of-fit indices were adequate in both groups: S-B χ2 = 587.54, df = 395, p < .001; normed χ2 = 1.45; RMSEA = 0.04 (90% CI = 0.04–0.05); CFI = 0.92; SRMR = 0.07, for male; and S-B χ2 = 817.56, df = 395, p < .001; normed χ2 = 2.07; RMSEA = 0.04 (90% CI = 0.04–0.05); CFI = 0.92; SRMR = 0.05, for female. Then, we examined measurement invariance across gender. First, a test of configural invariance was conducted by investigating a baseline model with no constrained parameters across two groups. The model showed acceptable model fit: S-B χ2 = 1405.4, df = 790, p < .001; normed χ2 = 2.18; RMSEA = 0.03 (90% CI = 0.03–0.04); CFI = 0.92; SRMR = 0.06. Second, a constrained model was estimated in which factor loadings and intercept values were set to be equal across two groups. The constrained model showed acceptable model fit: S-B χ2 = 1433.8, df = 855, p < .001; normed χ2 = 1.68; RMSEA = 0.03 (90% CI = 0.03–0.04); CFI = 0.93; SRMR = 0.07. Finally, the S-B Scaled χ2 difference test was performed to determine if the constrained model differed significantly from the unconstrained model. No significant differences were found: S-B Scaled χ2 = 59.19, df = 65, p = .68. Therefore, these results support measurement invariance of MCQ-30 across gender.

Gender Differences

Males were found to score significantly higher than females on positive beliefs about worry, M male = 10.62, SD male = 4.12; M female = 9.92, SD female = 4.06; t(1,766) = 2.18, p < .05, d = .17, and beliefs about the need to control thoughts, M male = 10.47, SD male = 3.63; M female = 9.94, SD female = 3.14; t(1,766) = 2.03, p < .05, d = .17. According to the criteria of Cohen (Reference Cohen1977), the effect size of these differences was small. Gender differences were not found for the total MCQ-30 or the other subscales scores.

Associations between MCQ-30 and related variables

We assessed the convergent validity of the MCQ-30 by analysing relationships between the MCQ-30 subscales and the total score on one hand, and measures of related constructs (pathological worry, meta-worry, thought suppression and trait anxiety) on the other (Table 3).

Table 3. Correlations between the MCQ-30 subscales or total score and other related variables

Abbreviations: WW, Why Worry; WW I, avoid negative outcomes; WW II, positive effects; *p < .05; **p < .01

Pathological worry and meta-worry showed significant positive correlations with all MCQ-30 subscales. The highest correlation was observed between meta-worry and the need to control thoughts (r = .66), cognitive self-consciousness (r = .65) and negative beliefs of uncontrollability/danger (r = .64). High correlation was also observed between pathological worry and positive beliefs about worry (r = .37). Positive and significant correlations were found between MCQ-30 and thought suppression, with r ranging from .34 to .54. All MCQ-30 subscales and the total score were significantly and positively related to trait anxiety, which showed particularly strong correlations with the need to control thoughts (r = .43) and the total score (r = .53).

Analysis of beliefs about worry, as measured by WW, revealed significant and positive correlations with the MCQ-30 subscales and the total score (see Table 3). Of special interest was the strong correlation between the positive beliefs about worry subscale of the MCQ-30 and the belief that worry has positive effects (r = .64), which was higher than the correlation with avoid negative outcomes (r = .34).

Discussion

The confirmatory factor analyses supported a structure with five related factors, which was found to be invariant across gender. This factor structure is similar to that found not only in the original MCQ-30 but also in the versions adapted to other populations (Tosun & Irak, Reference Tosun and Irak2008; Typaldou et al., Reference Typaldou, Nidos, Roxanis, Dokianaki, Vaidakis and Papadimitriou2010), suggesting that metacognitive beliefs, as assessed by the MCQ-30, are consistent across different cultures. Results also show that the MCQ-30 subscales and total score have good internal consistency comparable to that reported in other studies (Cartwright-Hatton & Wells, Reference Cartwright-Hatton and Wells1997; Spada et al., Reference Spada, Mohiyeddini and Wells2008; Wells & Cartwright-Hatton, Reference Wells and Cartwright-Hatton2004). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the subscales are similar to those reported for the original version, and the need for control subscale shows a smaller coefficient than the other subscales, just as with the original instrument (Spada et al., Reference Spada, Mohiyeddini and Wells2008). With regard to test-retest reliability, scores on both subscales as well as the total score scale were in general stable over a period of 3 months.

Gender differences were found suggesting that male have higher levels of positive beliefs about worry and beliefs about the need to control thoughts than female. However, the effect size of these differences was low. While similar results were reported for the need to control thoughts subscale by Spada et al. (Reference Spada, Mohiyeddini and Wells2008), no consistent gender differences have been found in MCQ-30 in other studies (Tosun & Irak, Reference Tosun and Irak2008; Wells & Cartwright-Hatton, Reference Wells and Cartwright-Hatton2004). More research is needed to explore when and why there are gender differences.

Our analyses of correlation showed, as expected, significant associations between MCQ-30 and theoretically related variables. Positive associations were found with pathological worry, meta-worry, thought suppression and trait anxiety. Taken together, these results support the idea that metacognitive beliefs are involved in worry and anxiety in the Spanish population and are consistent with the metacognitive model of GAD (Wells, Reference Wells2005).

MCQ-30 subscales were positively associated with pathological worry and meta-worry. In particular, the positive belief subscale showed the strongest relationship to pathological worry, suggesting that individuals who believe that worry is a useful coping strategy tend to use it to face anxiety-provoking situations or thoughts (Spada et al., Reference Spada, Mohiyeddini and Wells2008). In contrast, negative beliefs of uncontrollability and danger were strongly related to meta-worry. Negative beliefs typically concern themes of mental and physical catastrophe resulting from worry and are predicted to generate and maintain meta-worry. Together with negative beliefs, other dysfunctional beliefs about the need to control and attend to our own thoughts were also strongly related to meta-worry. Thus, individuals who believe that it is important to control their thoughts and pay close attention to the way their mind works may intensify the salience of their worrying, strengthening the belief that worrying is dangerous and uncontrollable and reinforcing their tendency to worry about worrying. As hypothesised by the model, once these beliefs and meta-worry develop, their activation leads to unproductive control strategies such as thought suppression and intensification of anxiety (Cartwright-Hatton & Wells, Reference Cartwright-Hatton and Wells1997; Wells, Reference Wells1995; Reference Wells2000). In this way, our results reveal positive relationships between the MCQ-30 and the tendency to suppress thoughts and feel anxious. Particularly strong associations were observed between thought suppression and the need to control thoughts, two scales that share content, as well as between total MCQ-30 score and trait anxiety, a result in line with previous studies (Wells & Cartwright-Hatton, Reference Wells and Cartwright-Hatton2004).

Interesting results were obtained about associations between MCQ-30 and other measures of beliefs about worry, as measured by the WW. Unlike the positive belief subscale of the MCQ-30, WW distinguishes between two positive beliefs about worry: belief that worrying can prevent negative outcomes, and belief that worrying has positive effects. Our results show correlations of different magnitude between the positive belief MCQ-30 subscale and the two WW subscales, with correlation stronger between the MCQ-30 subscale and the belief that worry has positive effects subscale of the WW. This result suggests that the MCQ-30 subscale is assessing mainly the belief that worry is positive because it brings positive consequences, such as finding a better way of doing things, increasing control, and finding solutions, rather than because it helps prevent negative consequences.

Before our findings can be generalized, it is important to take into account some limitations of the study. First, while a large sample of participants was used, it was primarily female (31.1% males, 68.9% females for factor and reliability analyses; 31.9% males, 68.1% females for correlation analyses with related variables; and 8.7% males, 91.3% females for test-retest analyses); more heterogeneous samples are required to confirm our results in the Spanish population. Second, we did not include a clinical sample (e.g., people with anxiety disorders), making it impossible to explore the utility of the Spanish MCQ-30 for differentiating between people with or without anxiety disorders, or between people with GAD from people with other disorders. For the same reason, we could not explore the sensitivity of the MCQ-30 to the effects of treatment, which should be a topic of future investigations. Finally, our data about the relationships between Spanish MCQ-30 and related variables are only correlational; longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the predictive value of the Spanish MCQ-30 subscales.

Despite these limitations, our study provides evidence of the validity and reliability of the Spanish MCQ-30. It is a practical instrument useful for assessing a range of metacognitive beliefs considered to be important in explaining pathological processes and anxiety disorders, mainly GAD. Future work should explore its utility in clinical settings and transcultural investigations.