The use of videogames (VG) in young adults and adolescents is an important cause of social alarm, since it has been more frequently associated with negative consequences such as sleep problems (Lam, Reference Lam2014), alterations in well-being (Scott & Porter-Armstrong, Reference Scott and Porter-Armstrong2013), increase in mental health problems or lesser degree of self-control (Son et al., Reference Son, Yasuoka, K, Poudel, Otsuka and Jimba2013). Other identified problems include deterioration of the family environment, social isolation, behavioral problems and a generally disorganized life. However, playing VG is a habitual leisure activity, especially amongst young adults and adolescents, and just a low percentage of players develop a problem that requires professional help. Therefore, it seems appropriate to dispose of criteria to discriminate between normal, excessive and problematic videogame gaming (VGG).

Until the inclusion of the Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) in the DSM–5 (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013), there was a lack of agreement between researchers regarding the criteria to identify when playing VG is problematic and frequently the identification was based on the criteria for pathological gambling or substance abuse (Kuss & Griffiths, Reference Kuss and Griffiths2012). There also was a lack of agreement on the name to be given to this problem, changing between excessive VGG, addiction to VG or problematic VGG.

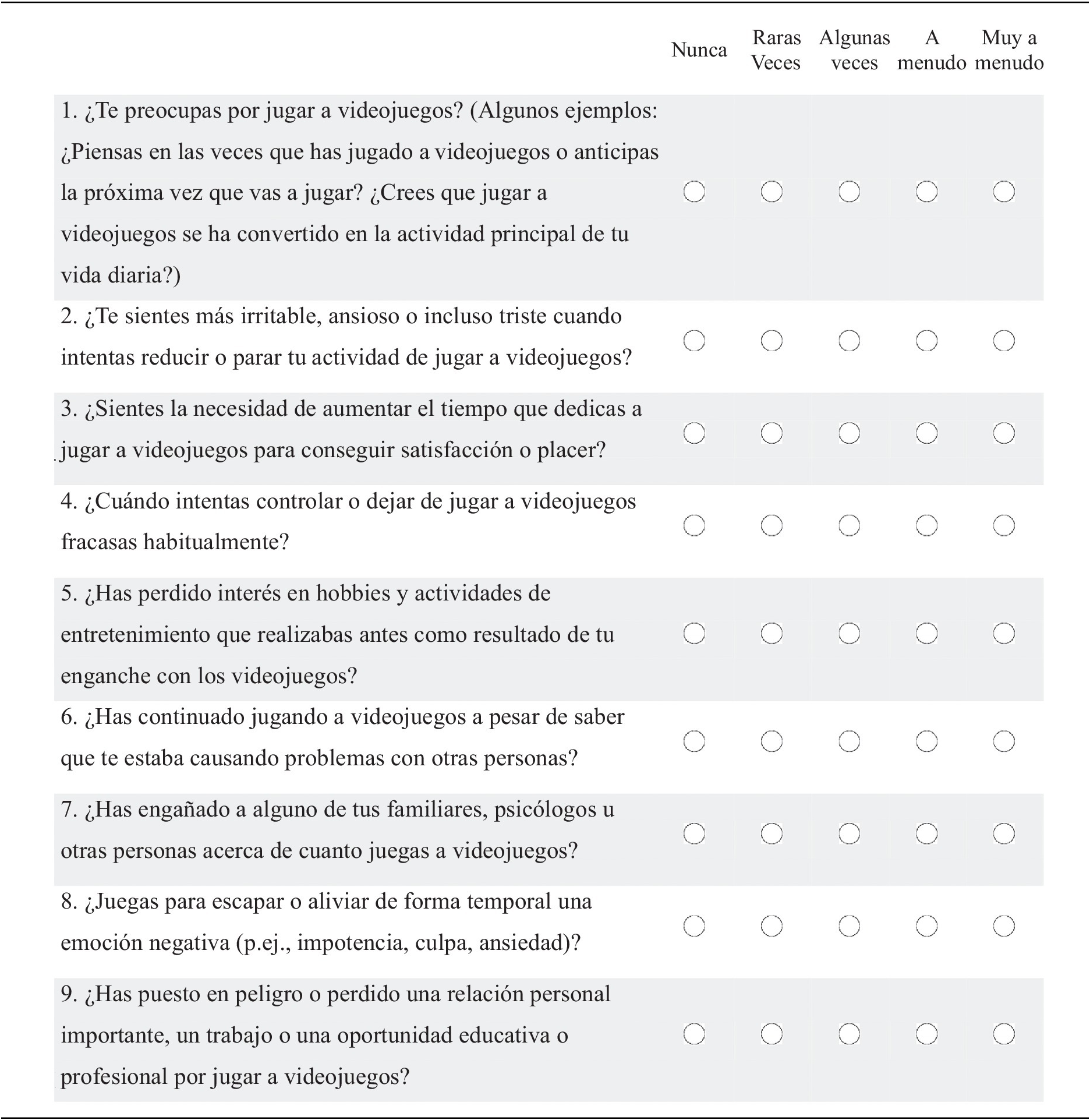

The DSM calls the problem IGD and establishes nine criteria for its diagnosis, of which five have to be met for a period of at least 12 months, although these do not determine the level of severity. These nine criteria are: (a) Preoccupation about internet gaming; (b) withdrawal symptoms; (c) tolerance; (d) unsuccessful attempts to control participation in internet gaming; (e) loss of interest in previous hobbies and entertainment activities as a result of, and with the exception of, videogames; (f) excessive and continued use of internet games regardless of the acknowledged psychosocial problems; (g) deceived family members, therapists, or other people regarding the amount of time spent playing games on the Internet; (h) use of videogames to escape or relieve negative moods and, (i) jeopardized or lost significant interpersonal relationships, jobs and educational or professional opportunities because of participations in Internet gaming. The contribution of the DSM–5 constitutes an advance, although it is not without controversy (Király et al., Reference Király, Sleczka, Pontes, Urbán, Griffiths and Demetrovics2017; Kuss et al., Reference Kuss, Griffiths and Pontes2017; van Rooij & Kardefelt-Winther, Reference van Rooij and Kardefelt-Winther2017).

It is difficult to determine the presence of IGD because of the limitations, or lack of precise criteria in the diagnosis of IGD (or alternative names), resulting in a widespread prevalence number, indicating as reference an estimate between 0.7% and 15.6%, shown in a meta-analysis by Feng et al. (Reference Feng, Ramo, Chan and Bourgeois2017). This broad range can account for, besides the lack of criteria or their suitability, the description of the problem, the disparity in the instruments available for evaluation and their limitations.

Previous to the publication of the DSM–5, Kuss and Griffiths (Reference Kuss and Griffiths2012), and King et al. (Reference King, Haagsma, Delfabbro, Gradisar and Griffiths2013), analyzed 18 measurement instruments of IGD (or alternative denominations) and their application, pointing out, between the strengths found, a high internal consistency (between .70 and .96), and a good convergent validity with related measures. Specifically, seven of these instruments found a positive correlation between severity, or number of symptoms, and time dedicated to VGG. However, the samples used were rather small, biased (very specific of a certain age group or mixed without distinction) and/or of convenience, generally obtained with online recruitment. Kuss and Griffiths (Reference Kuss and Griffiths2012) concluded that it was difficult to assess the validity of these tools in discriminating the level of addiction to gaming, recommending the development of manuals with standardized guidelines. At a later time, Griffiths (Reference Griffiths2017) pointed out that the assessment instruments for IGD were generally inconsistent.

In a more recent revision of the assessment tools for IGD in adolescents and young adults, Bernaldo-de-Quirós et al. (Reference Bernaldo-de-Quirós, Labrador-Méndez, Sánchez-Iglesias and Labrador2019), highlighted the significant changes made since the publication of the DSM–5 criteria. The study showed the variety of the instruments is reduced, now focusing on evaluating IGD (compared to the assessment of addiction to the Internet in general), they are often shorter (between 9 and 27 items) and they use an answer format of a 5 point Likert scale type. Between the tools analyzed, the value of the IGDS9–SF stands out (Pontes & Griffiths, Reference Pontes and Griffiths2015).

On the one hand, this could be due to the observed applicability and adjustment to the DSM–5 criteria. The IGDS9–SF features 9 items which account for the nine diagnostic criteria of the DSM–5. Its objective is to assess the severity of IGD and its harmful effects, evaluating the activities of VGG carried out on the Internet and outside of it, during the past 12 months. Furthermore, although the main objective of the instrument is not to diagnose IGD, a cutoff point is established to differentiate between players with or without the disorder. The validation of the original instrument (Pontes & Griffiths, Reference Pontes and Griffiths2015) was carried out with a sample of 1060 players, English speakers, between 16 and 60 years old (M =27 years old, SD = 9.02). The evaluation tool showed an internal consistency of .87, a single factor and good construct validity, with significant correlations with IGD–20 (Pontes et al., Reference Pontes, Király, Demetrovics and Griffitths2014), and the time dedicated to VGG per week.

On the other hand, the IGDS9–SF is also the most translated and validated instrument thus far: Portuguese (Pontes & Griffiths, Reference Pontes and Griffiths2016); Slovenian (Pontes et al., Reference Pontes, Macur and Griffiths2016); Italian (Monacis et al., Reference Monacis, de Palo, Griffiths and Sinatra2017); Persian (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Lin, Årestedt, Griffiths, Broström and Pakpour2017); Turkish (Evren et al., Reference Evren, Dalbudak, Topcu, Kutlu, Evren and Pontes2018); Polish (Schivinski et al., Reference Schivinski, Brzozowska-Woś, Buchanan, Griffiths and Pontes2018); and Spanish (Beranuy et al., Reference Beranuy, Machimbarrena, Osés, Carbonell, Griffiths and González-Cabrera2020). All of these validations studies agree in identifying one single underlying factor, with internal consistency between .82 and .99 and good criterion validity, with significant correlations with time spent VGG. Additionally, a relationship was found between scores on the IGDS9–SF and depression, anxiety and stress (Pontes & Griffths, Reference Pontes and Griffiths2016; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Lin, Årestedt, Griffiths, Broström and Pakpour2017), mental health (Pontes et al., Reference Pontes, Macur and Griffiths2016), life satisfaction (Pontes et al., Reference Pontes, Macur and Griffiths2016), gambling disorders, and quality of life (Beranuy et al., Reference Beranuy, Machimbarrena, Osés, Carbonell, Griffiths and González-Cabrera2020) measures. In the same way, the instrument showed good convergent validity using other tools measuring addiction to VG (Evren et al., Reference Evren, Dalbudak, Topcu, Kutlu, Evren and Pontes2018; Monacis et al., Reference Monacis, de Palo, Griffiths and Sinatra2017; Pontes & Griffiths, Reference Pontes and Griffiths2015) or addiction to the Internet in general (Evren et al., Reference Evren, Dalbudak, Topcu, Kutlu, Evren and Pontes2018; Monacis et al., Reference Monacis, de Palo, Griffiths and Sinatra2017).

The scoring of the IGDS9–SF ranges from 0 to 45 points, marking the cutoff point to consider a player with IGD, either a score of 35, or answering to five or more items with the maximum value “very often” (Pontes & Griffths, Reference Pontes and Griffiths2016; Pontes et al., Reference Pontes, Macur and Griffiths2016). Alternatively, the Italian version sets the cutoff point to identify players with IGD to 21, according to the gold standard of the Game Addiction Scales (Lemmens et al., Reference Lemmens, Valkenburg and Peter2009), showing sensitivity of 86.1% and specificity of 86%.

However, in the application of the IGDS9–SF the problems related to sample selection persist: The use of random sampling is scarce (Pontes et al., Reference Pontes, Macur and Griffiths2016; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Lin, Årestedt, Griffiths, Broström and Pakpour2017), in the majority of cases convenience sampling is used, with links in gaming forums (Evren et al., Reference Evren, Dalbudak, Topcu, Kutlu, Evren and Pontes2018; Pontes & Griffiths, Reference Pontes and Griffiths2015; Schivinski et al., Reference Schivinski, Brzozowska-Woś, Buchanan, Griffiths and Pontes2018) or recluting only in schools available to the researchers (Beranuy et al., Reference Beranuy, Machimbarrena, Osés, Carbonell, Griffiths and González-Cabrera2020; Pontes & Griffiths, Reference Pontes and Griffiths2016; Monacis et al., Reference Monacis, de Palo, Griffiths and Sinatra2017). Only half of these studies use a sample of exclusively adolescents and young adults (Beranuy et al., Reference Beranuy, Machimbarrena, Osés, Carbonell, Griffiths and González-Cabrera2020; Pontes & Griffiths, Reference Pontes and Griffiths2016; Pontes et al., Reference Pontes, Macur and Griffiths2016; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Lin, Årestedt, Griffiths, Broström and Pakpour2017), and in some cases they only briefly mention the number of participants of different age groups or any differentiation carried out (Monacis et al., Reference Monacis, de Palo, Griffiths and Sinatra2017; Schivinski et al., Reference Schivinski, Brzozowska-Woś, Buchanan, Griffiths and Pontes2018), and in one case we can see that age groups are not even discerned (Evren et al., Reference Evren, Dalbudak, Topcu, Kutlu, Evren and Pontes2018).

Due to the present circumstances, it seems of great interest to validate the IGDS9–SF in Spain, in a population of adolescents and young adults, using a random sample of educational institutions, in order to provide an instrument considered more appropriate for the current time, to assess the presence of problems with VGG. The objectives of this study were: 1) To assess the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the IGDS9–SF and criterion validity, by analyzing the relationships of their scores with other theoretically related variables.

2) To evaluate reliability with internal consistency and split-half method; construct validity using factor analysis and the measurement invariance across age and gender groups. In addition, we discussed the use of cutoff scores and, arguing that currently there is no adequate gold standard to base those scores on, presented a scoring scale instead.

Method

Participants

The initial sample comprised 2,887 participants of both genders, extracted from a representative sample of educational institutions from the city of Madrid. We considered two age groups, 12 to 16 (a total of 2020 students) and 17 to 22 years old (867 students). Of these, 75.0% and 75.8% played videogames, respectively. No relationship was found between age group and playing videogames, χ2(1) = 0.173, p = .677. The final sample consisted of 2,173 participants (28.8% females). Table 1 shows age and gender distributions for both samples.

Table 1. Age and Gender Distributions for Initial and Final Samples

Instruments and Measures

IGDS9–SF

The Spanish version of the scale (see Appendix) is an adapted translation of the original IGDS9–SF (Pontes & Griffiths, Reference Pontes and Griffiths2015); it was translated by two independent people and back-translated into Spanish by two native English speakers. An additional researcher overviewed the final version. This single-factor scale, based on the DSM–5 (APA, 2013) criteria for IGD, consists of nine 5-point Likert (1 “Never” to 5 “Very Often”) items. The total score is the sum of the items scores; the higher the score, the higher the severity of IGD.

General Health Questionnaire (GHQ–12: Goldberg & Williams, Reference Goldberg and Williams1988)

The 12 items establish a total score for perceived health (α = .569), with an anxiety subscale (7 items, α = .776) and a further one for dysfunction (5 items, α = .771). The correction used was Corrected GHQ, which aims to avoid underdetection of participants with long-term problems. Greater scores indicate poorer health.

Gaming Cognitions Scale (Fernández-Árias et al., Reference Fernández-Árias, Bernaldo-de-Quirós, Sánchez-Iglesias, Labrador-Méndez, Estupiñá and González-Álvarez2019).

This scale showed an adequate reliability R xx = .931 and internal consistency, (α = .907). It comprised sixteen 5-point Likert scale items (1 “Never” to 5 “Always”), ranging from 0 to 80 points (a greater score indicates more problematic cognitions towards videogames). Three factors account for 50.27% of the variance of the scores: Game immersion (α = .829), craving (α = .843), and refusal to stop playing (α = .799).

Frequency of gameplay

In two separate questions, participants reported their average days per week invested in playing VG, and average hours per week (from “less than 1 hour” up to “more than 30 hours” playing VG, increasing in order of five hours (1 to 5 hours, 6 to 10, until reaching 30, with the further option of more than 30 hours).

Procedure

Five independent evaluators with psychology degrees were trained to administer the Gamertest, an online assessment tool which includes the instruments used in this studyFootnote 1. Data on the student population for the 21 districts of the city of Madrid, including their ages, school year and type of schooling (public school, private school and state subsidized school), was retrieved from the website of the city hall statistics service (Comunidad de Madrid, 2017). Schools were divided into groups by district and type of school, and randomly ordered. Then, for each district and type of school, the first school on the list was contacted through a detailed letter, with a follow-up call soon thereafter, and asked to provide access to the set of classes required by the district. If the school refused, the next school on the list was contacted. Once a school agreed to participate in the study, the evaluators delivered informed consent forms for the children’s parents/guardians and a date was set for the evaluator to visit the school to perform the assessment in a classroom chosen using stratified random sampling. After collecting informed consent forms from the parents/guardians, the assessments were administered in groups, using computers in each school’s computer room, allowing approximately 30–40 minutes for the students to complete them. Participants’ responses were anonymously collected and coded directly in a computerized database.

Ethical issues for this study were audited by the ethics committee of the Universidad Complutense de Madrid’s Faculty of Psychology.

We used several R packages: The CFAs were carried out using lavaan, version 0.6–3 (Rosseel, Reference Rosseel2012); estimators Cronbach’s alpha and ω and their CI were computed using MBESS, version 4.4.3 (Kelley, Reference Kelley2018), and the invariance analysis was carried out with semTools (Jorgensen et al., Reference Jorgensen, Pornprasertmanit, Schoemann and Rosseel2018). The rest of the statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS 20, including macros for parallel analysis (O’Connor, Reference O’Connor2000) and Mardia’s multivariate analysis (DeCarlo, Reference DeCarlo1997).

Factorial validity

The final sample of participants, from 12 to 16 years old, was divided randomly into two subsamples of videogame players, to assess the validity of the Spanish version of the IGDS9–SF. One of the subsamples (n = 758) was used to carry out an exploratory factor analysis (EFA), after assessing the adequacy of the EFA in our dataset, via Bartlett’s sphericity test and KMO estimate. In this subsample, we assessed multivariate normality of the items via Mardia’s multivariate kurtosis and skewness coefficients (Mardia, Reference Mardia1970); as the hypothesis of normality was rejected, an unweighted least squares (ULS) extraction method was selected. Three criteria were used to determine the number of components to retain from EFA: The K1 method, the inspection of the scree plot and a principal components parallel analysis (Horn, Reference Horn1965). As only one factor was retained, no rotation method was used.

The second subsample (n = 758) was used to confirm the subjacent structure through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). To address non-normality issues, a maximum likelihood with robust standard errors estimation method (MLR) and Satorra-Bentler statistic were used. Several fit indexes were employed (and compared with the values recommended by Chau, Reference Chau1997; and Schreiber et al., Reference Schreiber, Nora, Stage, Barlow and King2006): Chi square statistic to degrees of freedom ratio (χ2/df), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and its 90% confidence interval, standard root mean square residual (SRMR), comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI). The magnitude, direction and statistical significance of the standardized parameter estimates were interpreted.

The third subsample (videogame players from 17 to 22 years old, n = 657) was also used in a CFA (using the same specifications as the first one), to extend the assessment of factor validity to that age group. To further examine the generalizability of the scale across younger and older participants in the whole sample, we tested for group measurement invariance using multiple group confirmatory factor analysis (MGCFA). Several nested multiple group models were tested for (a) configural invariance, (b) weak or metric invariance, and (c) strong or scalar invariance, in order to assess the invariance of number of factors, factor loadings and indicator intercepts, respectively. The χ2 difference (Δχ2) test, CFI difference (ΔCFI), and RMSEA difference (ΔRMSEA) were used as fit indices when testing for metric and scalar invariance. A value of ΔCFI < −.010 supplemented by a ΔRMSEA < .015 would indicate invariance (Chen, Reference Chen2007).

We also examined the generalizability of the scale across genders (regardless of age), using MGCFA, with the same criteria as for age MGCFA.

We calculated descriptive statistics for the items and the total score of the Spanish version of the IGDS9–SF for the three subsamples. Two estimators (with 95% CI) for internal consistency were used, as well as Cronbach’s alpha (α), and omega (ω) to overcome some problems associated with the former (McDonald, Reference McDonald1999). Also, we assessed split-half reliability using the Spearman-Brown formula (arranging the items of the two halves by mean).

ANOVA and correlation tests were used to study the relationship between IGDS9–SF scores and weekly frequency and average hours spent playing VG, respectively.

Lastly, we correlated the IGDS9–SF scores with the GHQ–12 scores and with the Gaming Cognitions Scale scores.

Results

IGDS9–SF Psychometric Properties

Item analysis and reliability.

Table 2 displays the mean and standard deviation values of the items as well as the total scale scores. Individually considered, all scores showed positive skewness, but different degrees of kurtosis. When analyzing Subsample 1, used for EFA, the estimates of Mardia’s multivariate kurtosis and skewness coefficients were high and significant, 34.69 and 166.36 respectively (both ps < .001). The internal consistency (α and ω) and reliability estimators were adequate for the three subsamples (see Table 2).

Table 2. IGDS9–SF. Descriptive Statistics, Internal Consistency and Reliability, by Subsample

Notes. N = 2,173. Subsample 1 (12 to 16 years old); n = 758. Subsample 2 (12 to 16 years old); n = 758. Subsample 3 (17 to 22 years old); n = 657.

EFA.

Both the KMO test, .90, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity, χ2(36) = 1,751.84, p < .001, showed the data was adequate for EFA. Table 3 shows the communalities of the items after the extraction of a single factor (see Figure 1 for the scree plot and parallel analysis results), as well as its factor loadings, which ranged from .503 to .685. The single factor accounted for 35.78% of the items’ total variance.

Table 3. IGDS9–SF. Results from Exploratory Factor Analysis

Note. N = 758. ULS extraction method. Explained variance 35.78%.

Figure 1. EFA scree plot for the Spanish version of the IGDS9–SF. The plot displays empirical data eigenvalues, mean and 95s percentile eigenvalues of 100 random samples in a parallel analysis. N = 758.

CFA

The fit indices for both CFA models can be found in Table 4. When considering Subsample 2, the CFA showed adequate fit based on all the model fit indices. In Subsample 3, the observed indices did not reach the threshold values on CFI and TLI, but they did on χ2/df, RMSEA and SRMR, so the model should not be rejected. Moreover, both models showed positive, significant (p < .001) item factor loadings, ranging from .357 to .697 for Subsample 2, and from .342 to .732 for Subsample 3 (see Figure 2), reaching the values recommended by Brown (Reference Brown2015).

Table 4. IGDS9–SF. Fit indices for CFA Models

Note. RV = Recommended values (Chau, Reference Chau1997; Schreiber et al., Reference Schreiber, Nora, Stage, Barlow and King2006).

Figure 2. CFA models for Subsample 2 (above, n = 758, from 12 to 16 years old) and Subsample 3 (below, n = 657, from 17 to 22 years old). Standardized coefficients. All factor loadings are statistically significant (ps < .001).

Measurement invariance

The MGCFA yielded a good fit across age group subsamples; the single factor model showed invariance in factor structure (configural invariance), when constraining factor loadings (metric invariance) and when constraining factor loadings and indicator intercepts (scalar invariance). Only the Δχ2 suggested non-invariance in the scalar invariance model, but this index is known for its sensitivity to sample size, and nonetheless ΔCFI and ΔRMSEA showed good fit (Table 5). Therefore, it can be concluded that the model is valid for both age groups.

Table 5. IGDS9-SF. Measurement Invariance by Age and Gender Groups

Notes: Robust estimators for CFI and RMSEA. All deltas are compared to the previous model.

When considering gender invariance (see Table 5), the MGCFA showed good configurable fit across genders (i.e. same factor structure for both groups). However, the model did not yield a good fit neither for the metric invariance model (the construct does not have the same meaning across genders) nor for the scalar invariance model (the intercepts are not equal across genders), attending to Δχ2 and ΔCFI, although ΔRMSEA was adequate.

Frequency of playing VG

There was a significant linear relationship between weekly frequency of playing and IGDS9–SF scores, F(1, 2,165) = 421.82, p < .001, η2 = .160. A higher score was associated with more hours of playing VG per week.

Participants played VG during an average of 3.41 days per week (Mdn = 3.00, SD = 2.01). We found a positive relationship between days of gaming per week and IGDS9–SF scores, r = .395, r 2 = .156.

GHQ–12 and Cognition scale

The IGDS9–SF scores positively correlated with GHQ–12 scores (with a shared variance, r 2, ranging from .007 to .040) and with the Cognition Scale scores (r 2 from .286 to .433), see Table 6.

Table 6. IGDS9–SF. Convergent Validity with GHQ–12 and with the Cognition Scale

Note: All correlations are significant, p < .001.

Scoring and Cutoff Values

The IGDS9–SF scores ranged from 9 to 45 (M = 16.29, SD = 6.29, Mdn = 15.00, IQR = 7.00). A significant difference was found between male (M = 17.41, SD = 6.36, Mdn = 16.00, IQR = 7.00) and female (M = 13.52, SD = 5.17, Mdn = 12.00, IQR = 5.00) participants, t(1,411.15) = 14.82, p < .001, accounting for 7.8% of the scores variance, r 2 = . 078. Because of this difference, and because the MGCFA showed metric and scalar non-invariance across gender groups, two separate scoring scales were computed for the IDGS9–SF (Table 7).

Table 7. IGDS9–SF. Scoring Scale for Total Sample and by Gender

Discussion

This study shows evidence for the validity -and reliability- of the Spanish version of the IGDS9–SF, putting forward the use of this short, self-report tool to assess Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD). We found sufficient psychometric evidence of internal consistency, reliability and factor validity for the Spanish version of the IDGS9–SF, when applied to a sample of 2,173 videogame players, composed of children, adolescents and young adults (from 12 to 22 years old) of both genders, recruited from a representative sample of educational centers from the city of Madrid.

We came across evidence of a single-factor model that matched the original, English scale structure (Pontes & Griffiths, Reference Pontes and Griffiths2015). This model was found in an EFA, and was confirmed in two distinct CFAs. The measurement invariance showed validity of the scale across age groups, therefore suggesting its use could be appropriate with participants within the age range between 12 and 22 years old. However, in this Spanish version of the scale, and unlike Monacis et al. (Reference Monacis, de Palo, Griffiths and Sinatra2017) or Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Lin, Årestedt, Griffiths, Broström and Pakpour2017), only configural gender invariance was found; while the single factor structure was the same for male and female participants, the factor loadings and factor intercept were different for each group. Due to these results, we put forward the use of separate scoring scales according to gender.

As part of the validation process, this study investigated the convergent and criterion validity of the Spanish IGDS9–SF with related measurements (GHQ and cognition scale) and other relevant variables such as gaming frequency. Additionally, a greater score in the IGDS9–SF was found to be associated with more gaming days per week and with a greater number of hours of gaming per week (in both cases sharing 16% of variance). This relationship with gaming time agrees with the one found in the validation of the original tool (Pontes & Griffiths, Reference Pontes and Griffiths2015), as well as with the assessments carried out in other countries in which this variable was examined (Pontes & Griffiths, Reference Pontes and Griffiths2016; Pontes et al., Reference Pontes, Macur and Griffiths2016; Schivinski et al., Reference Schivinski, Brzozowska-Woś, Buchanan, Griffiths and Pontes2018; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Lin, Årestedt, Griffiths, Broström and Pakpour2017). Furthermore, a relationship was found between high scores in the IGDS9–SF and poorer health, assessed with the GHQ–12 (sharing between 1% and 4% of variance, according to the factor examined), in agreement with the Portuguese, Slovene and Turkish validations (Pontes & Griffiths, Reference Pontes and Griffiths2016; Pontes et al., Reference Pontes, Macur and Griffiths2016; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Lin, Årestedt, Griffiths, Broström and Pakpour2017). Ultimately, a stronger relation was found (between 27% and 43% of the variance explained) between questionnaire scores and the problematic cognition scale regarding videogames. Despite the importance of the association between these cognitive distortions and the problematic use of videogames (King & Delfabro, Reference King and Delfabbro2016; Moudiab & Spada, Reference Moudiab and Spada2019), studies assessing the instrument had not included this type of assessment thus far. These results suggest good criterion validity for the adapted version of the IGDS9–SF.

The sample sizes employed in all the analyses (657, 758 and 758 participants for the three subsamples) can be considered sufficient, far exceeding the recommended sample size for factor analysis, even in the presence of low communalities (Lloret-Segura et al., Reference Lloret-Segura, Ferreres-Traver, Hernández-Baeza and Tomás-Marco2014).

Pontes and Griffith (Reference Pontes and Griffiths2015) suggested a cutoff value of 36 out of 45 to classify disordered gamers. In our sample, only 28 participants (1.30% of the gamers, and 0.96% of the total sample) scored a minimum of 36 out of 45. Other authors have suggested different cutoff scores based on gold standards (Monacis et al., Reference Monacis, de Palo, Griffiths and Sinatra2017). As the cutoff scores have –currently- no empirical support, we also followed other authors who support a more strict, clinical approach, with the endorsement of at least five of the criteria of IGD, by answering “very often” (the highest score) in at least five items of the IGDS9–SF (Evren et al., Reference Evren, Dalbudak, Topcu, Kutlu, Evren and Pontes2018; Pontes et al., Reference Pontes, Macur and Griffiths2016; Pontes & Griffiths, Reference Pontes and Griffiths2016; Schivinski et al., Reference Schivinski, Brzozowska-Woś, Buchanan, Griffiths and Pontes2018). Using this criterion, 65 participants (3.00% of the gamers, 2.25% of the total sample) would be labeled as having an IGD (similar to the 1.90% and 1.00%, respectively, found by Beranuy et al., Reference Beranuy, Machimbarrena, Osés, Carbonell, Griffiths and González-Cabrera2020). Furthermore, instead of relying on a single cutoff score without adequate empirical support, we provide a scoring scale, for the total sample and segregated by gender, for measurement purposes and norm referencing (Table 7). This scale allows comparing the score of a student to a norm group. Describing performance relative to others, even for non-disordered gamers, is a useful tool for measuring the construct.

The present study only examined a sample of Spanish students aged 12 to 22 years old, therefore the results cannot be generalized to the wider population. Also, the potential biases of self-reported data (such as social desirability and memory recall) are well known. Despite these limitations, we present sound evidence for the validity of the adapted version of the IGDS9-SF, a useful instrument to assess the severity of Internet Gaming Disorder in a population of young Spanish students.

Conflicts of Interest:

None.

Funding Statement:

This work was supported by project PSI2016-75854-P of the Spanish Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad.

Appendix

Internet Gaming Disorder Scale–Short–Form (IGDS9–SF) (Pontes & Griffiths, Reference Pontes and Griffiths2015)

Instrucciones: Estas cuestiones te preguntan sobre tu actividad de jugar a videojuegos durante el último año (es decir, los últimos 12 meses). Por jugar a videojuegos entendemos cualquier actividad relacionada con jugar a videojuegos, hayas jugado desde un ordenador, videoconsola o cualquier otro tipo de dispositivo (p.ej., móvil, tablet, etc.), online u offline.