There is evidence that regular exercise can play a role in preventing the onset of physiopathological (Bruning & Sturek, Reference Bruning and Sturek2015) and neurodegenerative (Larson et al., Reference Larson, Wang, Bowen, McCormick, Teri, Crane and Kukull2006) processes. Likewise, the literature suggests it can help boost mental health levels (Josefsson, Lindwall, & Archer, Reference Josefsson, Lindwall and Archer2014; Matta et al., Reference Matta Mello Portugal, Cevada, Sobral Monteiro-Junior, Teixeira Guimarães, da Cruz Rubini, Lattari and Camaz Deslandes2013). However, the potential psychological benefits of exercise are not reaped inherently from doing this activity, but from an interaction of social, personal, and motivational factors involved in this context (Szabo, Reference Szabo, Biddle, Fox and Boutcher2000). Understanding the mechanisms behind that interaction could help clarify to what extent these factors impact the mental health of people who exercise.

Basic psychological needs and social physique anxiety

Self-Determination Theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan2000) is one of the theoretical frameworks most widely used to explain the psychological processes that lead to different cognitive, emotional, and behavioral outcomes in human beings. Specifically, basic psychological needs theory (BPNT; Deci & Ryan, Reference Deci, Ryan, Ryan and Deci2002), one of the six mini-theories comprising SDT, has proven useful in explaining the influence of social contextual factors on a person’s global well-being (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Ntoumanis, Thogersen-Ntoumani, Deci, Ryan, Duda and Williams2012). BPNT maintains that well-being depends primarily on two things: a) individual and subjective interpretation of the social contextual features surrounding a given activity; and b) to what extent a person perceives that their needs for autonomy (i.e., feeling that one’s behavior responds to their own free will, so one’s actions are consistent with an integrated sense of self), competence (i.e., feeling effective in task execution and attainment of the goals one sets for him or herself), and social relatedness (i.e., feeling meaningfully connected to others, a feeling of belonging and acceptance by the people around oneself) are either satisfied or thwarted.

BPNT draws a distinction between low perceived satisfaction (e.g., feeling disconnected from others), and perceived thwarting (e.g., feeling rejected by others). The latter occurs when the individual believes there is an active obstacle in the way of basic psychological need satisfaction (Bartholomew, Ntoumanis, Ryan, & Thøgersen-Ntoumani, Reference Bartholomew, Ntoumanis, Ryan, Bosch and Thogersen-Ntoumani2011). Thus, if someone interprets that the social factors present in their context significantly justify doing a certain task, and that said factors enable them to choose how to execute that task, one will tend to perceive their basic psychological needs as being met (Deci & Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan2000; Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2000). On the other hand, if one interprets that their context is contributing to critical evaluation and pressuring them to take a specific action, he or she will tend to perceive their needs as being thwarted (Deci & Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan2000; Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2000).

SDT’s theoretical postulates have been supported by research findings that social contexts that promote personal autonomy facilitate perceived satisfaction, while controlling social contexts facilitate perceived thwarting (Bartholomew, Ntoumanis, Ryan, Bosch, & Thogersen-Ntoumani, Reference Bartholomew, Ntoumanis, Ryan, Bosch and Thogersen-Ntoumani2011; Ng, Ntoumanis, Thøgersen-Ntoumani, Stott, & Hindle, Reference Ng, Ntoumanis, Thøgersen-Ntoumani, Stott and Hindle2013). Such studies suggest that to expand the study of processes that determine global well-being and proper individual functioning, research should not just examine social factors that satisfy basic psychological needs, but factors that thwart those needs as well. One such social factor, determined by researchers to be controlling, is social physique anxiety (SPA; Alcaraz-Ibáñez, Sicilia, & Lirola, Reference Alcaraz-Ibáñez, Sicilia and Lirola2015).

SPA has been defined as a source of internal control that reflects an interpretation of social context according to which one perceives pressure for their figure to conform to a particular canon (Hart, Leary, & Rejeski, Reference Hart, Leary and Rejeski1989). Various studies have examined the influence of SPA in the context of exercise through the prism of BPNT, showing that SPA as a source of control decreases perceived satisfaction of basic psychological needs (Brunet & Sabiston, Reference Brunet and Sabiston2009), and more so increases the thwarting of those needs (Alcaraz-Ibáñez et al., Reference Alcaraz-Ibáñez, Sicilia and Lirola2015). Though SPA has been associated with the presence of depressive symptomatology (Diehl, Johnson, Rogers, & Petrie, Reference Diehl, Johnson, Rogers and Petrie1998; Lantz, Hardy, & Ainsworth, Reference Lantz, Hardy and Ainsworth1997; Woodman & Steer, Reference Woodman and Steer2011), researchers have yet to study its influence on mental health via basic psychological need deficit.

Basic psychological needs and mental health

According to the postulates of BPNT, a state of mental health entails an absence of psychopathology, experiencing feelings of vitality, and the ability to feel, regulate, and integrate one’s emotional experiences (Deci & Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan2000; Ryan, Deci, Grolnick, & La Guardia, Reference Ryan, Deci, Grolnick, La Guardia, Cicchetti and Cohen2006). Though BPNT recognizes that human beings are naturally oriented toward achieving individual well-being, for that process to occur, the individual must perceive that his or her psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are satisfied. By the same token, specifically in the exercise context, research has shown that if someone perceives him or herself as belonging to a group, able to participate in decision making, and capable of effectively doing the tasks involved in the activity, he or she is more likely to show adequate mental health (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Ntoumanis, Thogersen-Ntoumani, Deci, Ryan, Duda and Williams2012). Conversely, if some contextual element (e.g., teammates or coaches) actively diminishes his or her likelihood of feeling socially related, autonomous, and competent, the probability of developing various psychopathological processes may rise (Bartholomew, Ntoumanis, Ryan, Bosch et al., Reference Bartholomew, Ntoumanis, Ryan, Bosch and Thogersen-Ntoumani2011; Ng et al., Reference Ng, Ntoumanis, Thøgersen-Ntoumani, Stott and Hindle2013), impeding the natural tendency toward an optimal state of functioning (Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Deci, Grolnick, La Guardia, Cicchetti and Cohen2006).

That being said, studies that consider the influence of perceived need satisfaction as well as thwarting, in the exercise context, on different mental health indicators have reported inconclusive results. Bartholomew, Ntoumanis, Ryan, Bosch et al. (Reference Bartholomew, Ntoumanis, Ryan, Bosch and Thogersen-Ntoumani2011) observed that while need satisfaction was a stronger predictor of subjective vitality, need thwarting better predicted existing depressive processes. Conversely, Ng et al. (Reference Ng, Ntoumanis, Thøgersen-Ntoumani, Stott and Hindle2013) showed that the effects of controlling behavior – exhibited by people the individual exercises with – on satisfaction with life turned out to be mediated more by basic psychological need thwarting than satisfaction. Therefore, the research to date seems to suggest that basic psychological needs satisfaction and thwarting may play a differential mediating role in the relationship between social contextual factors and a person’s mental health.

One possible explanation for that apparently differential mediating role could be the nuanced potential outcomes of those two constructs according to BPNT. That is, while satisfaction might positively and directly influence a person’s mental health, thwarting may do so negatively and indirectly, mediated by different defense mechanisms. As Deci and Ryan (Reference Deci and Ryan2000) suggest, one such mechanism would be the adoption of controlling regulatory styles (i.e., in which the person feels pressure to adopt a certain behavior). However, that possibility regarding the more or less internal character of different (self-determined) forms of motivation set forth by SDT has been backed only in part by research in the field of exercise (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Ntoumanis, Thogersen-Ntoumani, Deci, Ryan, Duda and Williams2012). In fact, some longitudinal research findings in the exercise context show that, as SDT suggests, motivation could act as an antecedent to basic psychological needs (Gunnell, Crocker, Mack, Wilson, & Zumbo, Reference Gunnell, Crocker, Mack, Wilson and Zumbo2014). Another defense mechanism BPNT proposes is an excessive desire to control the need being thwarted, due to which the person would exhibit a rigid pattern of behavior. However, while that pattern might at first alleviate perceived need thwarting, it would also interfere with the potential satisfaction of that need, and therefore with individual well-being (Deci & Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan2000). To identify such a defense mechanism could help explain the relationship between social and personal factors involved in the exercise context and the mental health of exercisers.

Relational frame theory and psychological inflexibility

Relational frames theory (RFT; Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, Reference Hayes, Barnes-Holmes and Roche2001) argues that through successive relational learning experiences, human beings come to attribute particular functional meanings to the different linguistic and ideographic elements present in the cognitive process. However, instead of basing those meanings on the objective relationships among constituent elements, they are formed through a series of arbitrary relationships that are determined by context and therefore subject to multiple reinforcement situations. Thus, when someone verbalizes or evokes a certain element, the functional meaning attached to it will implicitly reflect an interpretation of the context in which the meaning is constructed. Therefore, a person’s final understanding of social context is determined more by the way he or she manages and attaches meaning to their thoughts, memories, and feelings (i.e., private events) than by their objective content. One such pattern of functioning is psychological inflexibility, where a person subjects their values, goals – even their own behavior – to the work of avoiding and controlling any private event that takes on a negative functional meaning (Bond et al., Reference Bond, Hayes, Baer, Carpenter, Guenole, Orcutt and Zettle2011). The literature to date has found evidence that psychological inflexibility can play a determining role in the onset of different psychopathological processes, and in lowering levels of emotional, psychological, and social well-being (Kashdan & Rottenberg, Reference Kashdan and Rottenberg2010).

The present study

Though BPNT and RFT independently help explain an individual’s mental well-being (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson2011; Ng et al., Reference Ng, Ntoumanis, Thogersen-Ntoumani, Deci, Ryan, Duda and Williams2012), and though the two theoretical frameworks can be complementary, so far, no study has integrated the two and analyzed the effects of social factors involved in the exercise context on mental health. First of all, RFT does not explicitly address the impact that contextual (i.e., SPA) and personal (i.e., need thwarting) elements defined by BPNT would have on desire for control. Second, BPNT and the macro-theory it belongs to (i.e., SDT) recognize that elements of psychological inflexibility – like adopting a rigid pattern of functioning, excessive desire for control over one’s feelings, and inhibiting awareness – could impede effective self-regulated action, thereby obstructing the natural, human tendency toward mental well-being (Deci & Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan2000; Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Deci, Grolnick, La Guardia, Cicchetti and Cohen2006). Third, BPNT’s structure does not include a construct to reflect the extent to which a person tends to manage his or her thoughts, memories, and feelings (all their private events) in a cognitively restrictive and controlling manner. This limitation could turn out to be especially important in addressing a source of internal control like SPA, which implies, in addition to an external objective reality (i.e., social pressure to achieve a certain physical appearance), the presence of an aversive affective component (Hart et al., Reference Hart, Leary and Rejeski1989).

Incorporating theoretical postulates from both BPNT and RFT, the present study was designed in order to ascertain the influence of SPA on mental health in exercisers. In light of the theoretical and empirical foundation laid out above, the following hypotheses were formulated. The first model was based on the postulates of BPNT, and hypothesized that SPA would negatively predict satisfaction with life and mental health, directly and as mediated by basic psychological need thwarting and satisfaction (H1). In the second hypothesized model, psychological inflexibility would mediate the interactive process between SPA and basic psychological needs on the one hand, and satisfaction with life and mental health on the other, helping to explain a higher percentage of variance in the latter two variables (H2). We expect that this study’s results will generate evidence to support incorporating psychological inflexibility into the sequence proposed by BPNT to explain the mental health effects of interpreting the social context within which a person engages in exercise.

Method

Participants

This study’s sample was non-clinical, and comprised of 296 men who practice a form of endurance training recreationally. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 60 years old (M age = 35.65, SD = 9.49) and reported dedicating on average 9.37 hours per week (SD = 3.95) to the activity, specifically cycling (86%) and triathlon (14%). Of participants, 12% had gone to primary school only, 43% secondary school, and the remaining 45% university.

Instruments

Social physique anxiety

The Spanish version (Sáenz-Alvarez, Sicilia, González-Cutre, & Ferriz, Reference Sáenz-Alvarez, Sicilia, González-Cutre and Ferriz2013) of the one-dimensional Social Physique Anxiety Scale (SPAS-7; Motl & Conroy, Reference Motl and Conroy2000) was used, made up of seven items (e.g., “It would make me uncomfortable to know others were evaluating my physique or figure”). The scale was preceded by the phrase: “When I exercise…” Responses were given on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all characteristic of me) to 5 (extremely characteristic of me). After inverting item 5, which is phrased in the inverse, higher scores indicate higher levels of SPA. The study that validated the instrument for the Spanish context (Sáenz-Alvarez et al., Reference Sáenz-Alvarez, Sicilia, González-Cutre and Ferriz2013) reported adequate values of internal consistency (α = .85).

Basic psychological need satisfaction

The Spanish version (Moreno-Murcia, Marzo, Martínez-Galindo, & Conte Marín, Reference Moreno-Murcia, Marzo, Martínez-Galindo and Conte Marín2011) of the Psychological Need Satisfaction in Exercise scale (PNSE; Wilson, Rogers, Rodgers, & Wild, Reference Wilson, Rogers, Rodgers and Wild2006) was employed. This instrument’s 18 items are grouped into 3 subscales of 6 items each, and evaluates the extent to which exercisers perceive that in this context, their needs for autonomy (e.g., “I feel like I have a say in choosing the exercises that I do”), competence (e.g., “I feel capable of completing exercises that are challenging to me”), and social relatedness (e.g., “I feel connected to the people who I interact with while we exercise together”) are met. The scale’s items are preceded by the phrase: “When I exercise…” Responses are given on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (false) to 6 (true). The study that validated this instrument for the Spanish context (Moreno-Murcia et al., Reference Moreno-Murcia, Marzo, Martínez-Galindo and Conte Marín2011) reported adequate values of internal consistency for the factors autonomy (α = .69), competence (α = .80), and social relatedness (α = .73).

Basic psychological need thwarting

The Spanish version (Sicilia, Ferriz, & Sáenz-Álvarez, Reference Sicilia, Ferriz and Sáenz-Álvarez2013) of the Psychological Need Thwarting Scale (PNTS; Bartholomew, Ntoumanis, Ryan et al., Reference Bartholomew, Ntoumanis, Ryan, Bosch and Thogersen-Ntoumani2011) was used. This instrument consists of 12 items, grouped into 3 subscales with 4 items each, and evaluates the extent to which exercises perceive that in this context, their needs for autonomy (e.g., “I feel obliged to follow training decisions made for me”), competence (e.g., “There are situations in which I am made to feel inadequate”), and social relatedness (e.g., “I feel I am rejected by those around me”) are thwarted. Scale items are preceded by the phrase: “When I exercise…” Responses are given on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The study that validated the instrument for the Spanish context (Sáenz-Alvarez et al., Reference Sáenz-Alvarez, Sicilia, González-Cutre and Ferriz2013) found adequate values of internal consistency for the factors autonomy (α = .70), competence (α = .70), and social relatedness (α = .71).

Psychological inflexibility

The Spanish version (Ruiz, Langer, Luciano, Cangas, & Beltrán, Reference Ruiz, Langer Herrera, Luciano, Cangas and Beltrán2013) of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II; Bond et al., Reference Bond, Hayes, Baer, Carpenter, Guenole, Orcutt and Zettle2011) was used, which has seven items (e.g., “My painful experiences and memories make it difficult for me to live a life that I would value”). Responses are given on a Likert scale with anchors 1 (never true) and 7 (always true). Higher scores reflect greater psychological inflexibility. The study that validated this instrument for the Spanish context (Ruiz et al., Reference Ruiz, Langer Herrera, Luciano, Cangas and Beltrán2013) reported adequate values of internal consistency (α = .88).

Mental health

In keeping with current mental health models (Keyes, Reference Keyes2005), this variable was assessed using an index that captures elements of the absence or presence of psychopathology (e.g., anxiety, depression), and a typical index of positive mental health (e.g., happiness), in this case the Spanish version (Alonso, Prieto, & Antó, Reference Alonso, Prieto and Antó1995) of the 5-item Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5; Berwick et al., Reference Berwick, Murphy, Goldman, Ware, Barsky and Weinstein1991). Participants were asked to indicate how often in the past month they had experienced the symptoms described in each item (e.g., “felt downhearted and blue”). Responses are given on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a great deal). After inverting the direction of items that tap symptoms of poor mental health (items 1, 2, and 4), higher scores are indicative of greater mental health. The study that validated this instrument into the Spanish context (Alonso et al., Reference Alonso, Prieto and Antó1995) reported adequate values of internal consistency (α = .77).

Satisfaction with life

The Spanish version (Atienza, Pons, Balaguer, & García-Merita, Reference Atienza, Pons, Balaguer and García-Merita2000) of the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, Reference Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin1985) was used. Participants responded to each of the scale’s five items (e.g., “I am satisfied with my life”) on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The study that validated the instrument for the Spanish context (Atienza et al., Reference Atienza, Pons, Balaguer and García-Merita2000) found adequate values of internal consistency (α = .84).

Procedure

We contacted the administrators of several forums and blogs about cycling- and triathlon-related subjects, asking for their collaboration in publicizing the project. In order to recruit participants, several advertisements were placed in those media. Anyone who responded offering to collaborate in the study received information about its characteristics and objectives. After obtaining informed consent from participants, they were given a link to the server where they could access an electronic form of the questionnaire, and complete it anonymously. The automatic protocol for questionnaire completion prevented data loss.

Data analysis

Preliminary analyses

First, the data were analyzed to identify any potential univariate (i.e., |z| > 3.00) or multivariate outliers, using the criterion p < .001 for Mahalanobis distance (D 2). Mahalanobis distance was evaluated through χ2 significance testing with as many degrees of freedom as there were variables in the study (df = 10). We found five cases that surpassed the critical value of 29.59; after determining that they were multivariate outliers, they were eliminated from all subsequent analyses. Eliminating those five cases produced the final sample (N = 296).

Second, we examined the factorial validity of all instruments employed using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and the software MPlus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). Since Mardia’s coefficient (p < .001) suggested a lack of multivariate normal distribution in all cases, different CFAs were carried out using the method of maximum likelihood estimation and a bootstrapping technique with 5000 samples. The objective was to ensure the indices were not affected by the distribution of data (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, Reference Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson and Tatham2006). To evaluate the instruments’ factor structure and the tested models’ goodness of fit, we employed the following goodness of fit indices: the quotient of the chi-squared statistic and degrees of freedom (χ2 /df), CFI (Comparative Fit Index), TLI (Tucker Lewis Index), IFI (Incremental Fit Index), RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) and its 90% confidence interval (CI), and SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual). Values of χ2 /df under3, incremental indexes (CFI and TLI) near or above .95, and values of RMSEA and SRMR near or below .06 and .08, respectively, were considered to indicate adequate goodness of fit between a given model and the data (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson and Tatham2006).

Third, we calculated means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations using Pearson’s R coefficient, obtaining internal consistency indexes for each scale, Cronbach’s α. Said analyses were conducted using the statistical package IBM SPSS 22.0.

Primary analyses

Although the values of univariate skewness (–.561 to 1.512) and kurtosis (–.262 to 2.305) fell within the accepted limits in terms of absolute value (skewness < 3.0 and kurtosis < 10.0; Kline, Reference Kline2005), we observed a lack of multivariate normal distribution (Mardia’s coefficient = 28.76, p < .001). Thus, the models being tested were analyzed using the method of maximum likelihood estimation, a bootstrapping technique (Preacher & Hayes, Reference Preacher and Hayes2008), and the software MPlus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). That procedure generated 5000 random samples that enabled us to obtain standard errors and bias-corrected confidence intervals of 95% (CIbc) for the model’s parameters. The various direct and indirect effects were deemed statistically significant if the CIbc did not include zero (Preacher & Hayes, Reference Preacher and Hayes2008).

The one-dimensional constructs examined were represented as observed variables, while satisfaction and thwarting of basic psychological needs were posited as latent variables, each based on three indicators – scores on their respective autonomy, competence, and social relatedness factors (Stebbings, Taylor, Spray, & Ntoumanis, Reference Stebbings, Taylor, Spray and Ntoumanis2012). Even for the more complicated of the two models (Model 2), this design allowed for a ratio of cases (296) to estimated parameters (39) of 7.59:1, above the minimum of 5:1 recommended by Kline (Reference Kline2005). Following Preacher and Hayes’ (Reference Preacher and Hayes2008) suggestions about analyzing multiple-mediator models, correlation was permitted between residual variances in the latent variables (i.e., satisfaction and thwarting of basic psychological needs), and between the two independent variables examined.

First, the effects of SPA on a person’s satisfaction with life and mental health were measured, looking at effects produced either directly or mediated by perceived satisfaction or thwarting of basic psychological needs. Next, a second model was tested reflecting the potential mediating role of psychological inflexibility in that relationship. To avoid spurious overestimation of indirect effects, we computed all direct and indirect effects involved in both models (Preacher & Hayes, Reference Preacher and Hayes2008). A significance level of p < .05 was utilized in all statistical analyses.

Results

Factorial validity of the instruments employed

CFA found evidence that goodness of fit was somewhat lacking between the hypothetical structures of some scales (i.e., one higher-order factor and three latent factors in the case of the PNSE and PNTS; a single factor for all the other instruments), and this sample’s data. Testing the regression loadings and standardized residuals identified certain problematic items. Such was the case of SPAS-7 item 5 (written in reverse), PNSE item 6 (which belongs to the social relatedness subscale), PNTS items 1 and 11 (which pertain to the autonomy and competence subscales, respectively), and AAQ-II item 2. To preserve the original factor structures of each instrument, and aiming to substantially improve goodness of fit by retaining only the best indicators (Hofmann, Reference Hofmann1995), those five items were eliminated from subsequent analyses. Accordingly, original and re-specified goodness of fit indices appear in Table 1. Standardized regression coefficients for the items that comprise each construct and factor ranged from .63 to .89 (SPAS-7), .65 to .85 (PNSE, autonomy), .68 to .92 (PNSE, competence), .70 to .92 (PNSE, social relatedness), .61 to .77 (PNTS, autonomy), .63 to .83 (PNTS, competence), .50 to .81 (PNTS, social relatedness), .83 to .89 (AAQ-II), .57 to .90 (MHI), and from .77 to .90 (SWLS), all statistically significant (p < .01).

Table 1. Goodness of Fit Indices of Instruments Utilized

Note: CFI = Comparative Fit Index; TLI = Tucker Lewis Index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation (in parentheses, low and high limits of a 90% confidence interval); SRMR = standardized root mean square residual.

Descriptive statistics

Table 2 presents means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations for the study’s variables, as well as coefficients of internal consistency for the final version of each scale. Average scores on a first set of variables (basic psychological need satisfaction, satisfaction with life, and mental health) were above the midpoint of those scales, while average scores on the remaining variables were below the scales’ respective midpoints. The instruments’ internal consistency measures ranged from .71 to .94. Social physique anxiety, psychological inflexibility, and the factors that indicate thwarting of basic psychological needs were negatively, statistically significantly correlated with mental health as well as satisfaction with life. On the other hand, basic psychological need satisfaction correlated positively and statistically significantly with mental health and satisfaction with life.

Table 2. Means, Standard Deviations, Internal Consistency (α), and Bivariate Correlations among the Study’s Variables

Note: SPA = social physique anxiety; NS = need satisfaction; NT = need thwarting; PI = psychological inflexibility.

* p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Structural equation models

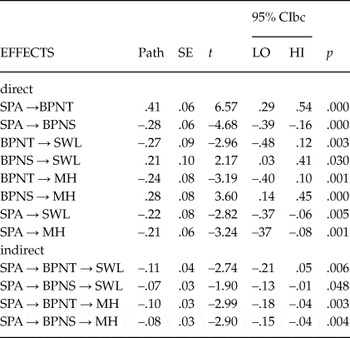

The first model tested (Figure 1) displayed adequate goodness of fit to the data, χ2(20, N = 296) = 45.90, p < .001, χ2 /df = 2.29; CFI = .973; TLI = .952; RMSEA = .066 (90% CI = .041 to .092); SRMR = .039. It explained 20% of variance in satisfaction with life, and 25% of variance in mental health.

Figure 1. Structural model examining SPA’s influence, in the exercise context, on levels of life satisfaction and mental health.

Note: (a) = Model 1; (b) = Model 2; BPNS = basic psychological need satisfaction; BPNT = basic psychological need thwarting. In the interest of clear presentation, regressions below the level of statistical significance (p < .05) have been omitted, along with indicators of the latent variables’ factors (represented as circles), and the correlations between error terms in basic psychological need satisfaction and thwarting (Models 1 and 2: r = –.17, p = .038) and between satisfaction with life and mental health (Model 1: r = .39, p < .001; Model 2: r = .17, p = .003). All regression coefficients presented are unstandardized.

In that first model, SPA’s total effect on the study’s independent variables (satisfaction with life: β = –.40, p < .001; mental health: β = –.39, p < .001) was the sum of its direct effects (satisfaction with life: β = –.22; p = .005; mental health: β = –.21, p = .001) and indirect effects produced via satisfaction and thwarting of basic psychological needs (satisfaction with life, β = –.18, p = .001; mental health, β = –.18, p < .001). As shown in Table 3, all of SPA’s direct and indirect effects on satisfaction with life and mental health were statistically significant.

Table 3. Direct and Indirect Effects (Model 1)

Note: SPA = social physique anxiety; BPNS = basic psychological need satisfaction; BPNT = basic psychological need thwarting; PI = psychological inflexibility; SWL = satisfaction with life; MH = mental health; CIbc = bias-corrected confidence interval. Valuesbased on unstandardized coefficients. Analysis conducted using a 5,000-sample bootstrapping technique.

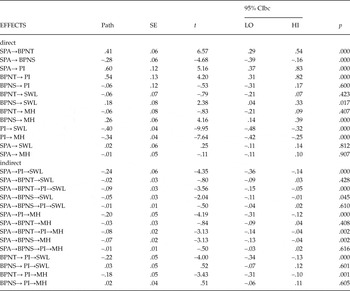

The second model tested (Figure 1b) showed goodness of fit to the data, χ2(24, N = 296) = 48.78, p < .001, χ2 /df = 2.03; CFI = .980; TLI = .962; RMSEA = .059 (90% CI = .035 to .083); SRMR = .039. In it, SPA predicted satisfaction with life and mental health, mediated by: 1) Psychological inflexibility only (satisfaction with life: β = –.24, p < .001; mental health: β = –.20, p < .001); 2) Thwarting of basic psychological needs and psychological inflexibility (satisfaction with life: β = –.09, p < .001; mental health: β = –.08, p = .002); and 3) Satisfaction of basic psychological needs only (satisfaction with life: β = –.05, p = .045; mental health: β = –.07, p = .002). The second model explained 43% of variance in both satisfaction with life, and mental health. As Table 4 shows, in the second model, the strength of the direct relation between SPA and the two independent variables was lower than in Model 1. By the same token, those correlations were no longer significant in the second model (satisfaction with life, β = .02, p = .812; mental health, β = –.01, p = .907).

Table 4. Direct and Indirect Effects (Model 2)

Note: SPA = social physique anxiety; BPNS = basic psychological need satisfaction; BPNT = basic psychological need thwarting; PI = psychological inflexibility; SWL = satisfaction with life; MH = mental health, CIbc = bias-corrected confidence interval. Values based on unstandardized coefficients. Analysis conducted using a 5,000-sample bootstrapping technique.

In both models, the standardized factor loading of the latent variables’ constituent indicators, of autonomy, competence, and social relatedness, respectively, were .74, .83, and .64 for basic psychological need satisfaction, and .77, .86, and .84 for basic psychological need thwarting.

Discussion

Guided by the principles of BPNT and RFT, the present study analyzed the influence of SPA, as experienced in the exercise context, on the mental health of exercisers. On the one hand, results confirmed BPNT postulates by reaffirming that basic psychological needs are key to explaining the mental health impact of interpreting social context, among exercisers. Nonetheless, results suggest we must also consider the role of psychological inflexibility to better explain how some of the social and personal factors posited by BPNT can impact mental health. Thus, there was evidence to support integrating the two theories in an effort to understand the process by which SPA can condition the potential benefits of exercise.

First we analyzed a theoretical model (Figure 1a) that, in keeping with the principles of BPNT, only considered the mediation of basic psychological needs. Results showed that SPA negatively predicted satisfaction with life and mental health, both directly and mediated by basic psychological needs. As in previous studies, SPA was negatively correlated with perceived satisfaction of basic psychological needs (Brunet & Sabiston, Reference Brunet and Sabiston2009), and positively correlated with the thwarting of those needs (Alcaraz-Ibáñez et al., Reference Alcaraz-Ibáñez, Sicilia and Lirola2015), therefore reinforcing SPA’s role as a controlling social factor.

Next we analyzed a second model, which incorporated a mediating effect of psychological inflexibility into the sequence established by BPNT (Figure 1b). This model’s results showed that while basic psychological need satisfaction predicted satisfaction with life and mental health directly, thwarting those needs did so via, or mediated by, psychological inflexibility. Furthermore, the sequence proposed in the second model we tested explained a larger portion of variance in satisfaction with life as well as mental health.

To be specific, this study’s results indicate that SPA in the exercise context can negatively impact a person’s satisfaction with life and mental health levels via two distinct mechanisms. In the first, there is a drop in perceived satisfaction of basic psychological needs – that is, fewer personal experiences that nurture, or feed, the process that leads to full personal well-being (Deci & Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan2000). In the second, increased psychological inflexibility emanating from SPA acts directly on satisfaction with life and mental health, and also affects them indirectly, mediated by basic psychological need thwarting.

These findings suggest SPA and basic psychological need thwarting do not negatively influence mental health based on their objective content (e.g., feeling uncomfortable exposing one’s physique in the case of SPA, or feeling rejected by fellow exercisers, specifically in the case of social relatedness need thwarting). On the contrary, as the principles of RFT describe (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Barnes-Holmes and Roche2001), one might feel less satisfied with his or her own life, or show symptoms of psychopathology due to an ineffective pattern of cognitive functioning (i.e., psychological inflexibility) that emerges in an effort to control the averse functional meaning associated with private events, derived from SPA and need thwarting.

These results suggest that integrating BPNT and RFT could help explain the differential effects of perceived satisfaction/thwarting on different mental health indexes reported in earlier research (Bartholomew, Ntoumanis, Ryan, Bosch et al., Reference Bartholomew, Ntoumanis, Ryan, Bosch and Thogersen-Ntoumani2011; Ng et al., Reference Ng, Ntoumanis, Thøgersen-Ntoumani, Stott and Hindle2013). The present study’s results are consistent with SDT postulates, and suggest that trying to control one’s emotions, in this case through cognitive regulation that constrains self-awareness and action to avoid and control the functional meaning of private events (i.e., psychological inflexibility), can interfere with a person’s mental well-being (Deci & Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan2000; Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Deci, Grolnick, La Guardia, Cicchetti and Cohen2006).

Though the present study is merely a first attempt at integrating RFT and BPNT, results suggest intervention possibilities. With that in mind, there has been evidence to suggest that acceptance and commitment therapy (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson2011) is useful in decreasing psychological inflexibility and the occurrence of different psychopathological processes, and in potentiating mental well-being (Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, Reference Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda and Lillis2006; Ruiz, Reference Ruiz2010). Future studies should gauge ACT’s usefulness, experimentally, as a possible intervention to ameliorate the negative effect of SPA, in the exercise context, on the mental health of individuals who experience this sort of pressure in sport.

Although these results contribute to our understanding of some mechanisms that may compromise the health benefits associated with exercise, we should review certain limitations. First of all, given this study’s cross-sectional design, its results cannot confirm that the relationships observed imply causation. Future studies could deploy longitudinal and experimental designs to elucidate the potential impact of SPA, and other mediator variables explored in this research, on mental health. Second, while the present study suggests the influence of SPA on mental health in the exercise context, surely other spheres of life not addressed in this study will influence that construct as well. Third, participants in the present study were entirely men who recreationally practice certain modes of exercise (i.e., cycling and triathlon), so the generalizability of results may be limited. For instance, previous research showed differences in psychological inflexibility levels as a function of sex (Ruiz et al., Reference Ruiz, Langer Herrera, Luciano, Cangas and Beltrán2013), and differences in perceived satisfaction of basic psychological needs as a function of sex and sport modality (i.e., recreational or competitive, individual or team sport; Gillet & Rosnet, Reference Gillet and Rosnet2008). Future research should corroborate the relationship observed between this study’s variables in more heterogeneous samples (e.g., different sex and sport modality). Finally, this study utilized a general mental health measure (MHI-5), and one that specifically taps a positive mental health dimension (SWLS). Future studies might expand on these results, taking a multidimensional perspective on mental health, and including tools that tap specific psychopathological processes (e.g., anxiety or depression) and elements of the hedonic (i.e., happiness and emotional well-being) and eudaimonic (i.e., psychological and social well-being) perspectives on positive mental health (Hervás & Vázquez, Reference Hervás and Vázquez2013).

In conclusion, the present study found empirical evidence to support integrating the theoretical postulates of BPNT and RFT to explain the process through which a controlling social factor in the exercise context, like SPA in this case, can reduce the potential health benefits of sport. Specifically, results suggest that perceived loss of control over various external elements, stemming from high SPA and the thwarting of basic psychological needs, can spur someone to adopt a compensatory mechanism characterized by an excessive desire to control internal events (i.e., psychological inflexibility). That would indeed decrease exercisers’ mental health. Integrating these two theories could enhance our future understanding of the negative consequences of interpreting body-image-related social factors that are present in the sport context.

This paper was carried out with the aid of the research project “Body Image and Exercise in Adolescence: A longitudinal study” (Ref. DEP2014–57228-R), funded by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad in Spain and FEDER funds.