Anger is a primary, normal, and universal emotion, with an important adaptive value (Averill, Reference Averill1983), particularly in circumstances in which the hedonic content is negative (Russell & Feldman-Barrett, Reference Russell and Feldman-Barrett1999). However, if anger is too intense, frequent, long-lasting, or disproportionate, it can become dysfunctional, being related to both psychosocial (Deffenbacher, Reference Deffenbacher2011) and physical (Suinn, Reference Suinn2001) disorders.

The role of rumination in anger

Rumination –defined as a perseverative, repetitive, and intrusive cognitive process about personally meaningful anger-inducing events- could play a key role in the anger experience onset and its intensity levels. Anger rumination is associated with angry memories and attention focus on a current anger experience, and also with counterfactual thinking directed to solve problems; hence, it could be considered a coping skill and an emotional self-regulation strategy (Day, Wilhelm, & Gross, Reference Day, Wilhelm and Gross2008; Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubormisrky, Reference Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco and Lyubomirsky2008; Whitmer & Gotlib, Reference Whitmer and Gotlib2013). In this regard, recent findings suggest that rumination could have an adaptive value, if it is concrete and action-oriented, or a dysfunctional role, when it is abstract, general, and not action-directed (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., Reference Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco and Lyubomirsky2008). These authors state that it is necessary to emphasize its functional or dysfunctional quality, and recommend the use of the term ‘rumination’ only when the process is disadaptive, and ‘self-reflection’ to denote an adaptive rumination (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., Reference Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco and Lyubomirsky2008).

Furthermore, rumination seems to be a mediational vulnerability mechanism in the development of dysfunctional anger, as well as emotional and physical health disorders (Brosschot, Gerin, & Thayer, Reference Brosschot, Gerin and Thayer2006; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., Reference Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco and Lyubomirsky2008). In this regard, rumination seems to be a vulnerability factor common to depression, anxiety, and anger disorders, although it may differ by its specific content, which would be congruent with the emotional experience (McEvoy & Brans, Reference McEvoy and Brans2013; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., Reference Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco and Lyubomirsky2008; Wilkowski & Robinson, Reference Wilkowski and Robinson2010). Thus, rumination could contribute to explain both, the overlap between the three main negative emotions (i.e., anger, sadness, and anxiety), and the high comorbidity between depression, anxiety disorders, and dysfunctional anger (McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, Reference McLaughlin and Nolen-Hoeksema2011).

Consequently, anger assessment, and specifically anger rumination, has become a relevant part of anger psychology as well as of clinical and health psychology. However, there is a lack of adequate instruments developed to assess the cognitive components and processes related to anger (Eckhardt, Norlander, & Deffenbacher, Reference Eckhardt, Norlander and Deffenbacher2004), with the exception of some valuable contributions like the Anger Rumination Scale (ARS; Sukhodolsky, Golub, & Cromwel, Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001).

The Anger Rumination Scale

The ARS (Sukhodolsky et al., Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001) is a 19-item self-report instrument developed to assess anger rumination frequency. It is structured in four subscales: Angry Afterthoughts (ruminative thinking about the present anger episode), Angry Memories (perseveration about past angry events), Thoughts of Revenge (rumination about how to get revenge in order to repair the offense), and Understanding of Causes (perseverative thinking about the causes and consequences of the event and counterfactual thinking). This structure was replicated in other languages and cultures like British, Chinese, or French, with the test showing adequate psychometric properties (Maxwell, Sukhodolsky, Chow, & Wong, Reference Maxwell, Sukhodolsky, Chow and Wong2005; Reynes, Berthouze-Aranda, Guillet-Descas, Chabaud, & Deflandre, Reference Reynes, Berthouze-Aranda, Guillet-Descas, Chabaud and Deflandre2013).

The aim of this study was to adapt the ARS to Spanish following the international guidelines of the International Test Commission (ITC) (Muñiz, Elosúa, & Hambleton, Reference Muñiz, Elosúa and Hambleton2013). The psychometric properties of the Spanish version were also tested. Regarding the ARS validity and according to the conceptualization of anger rumination as an internal, cognitive, and repetitive way of coping in an attempt to regulate anger, variables like anger suppression, rumination trait, and worry were used to analyze convergent validity. In relation to discriminant validity, emotional responses related to anger (anxiety and depressive mood), cognitive processes incompatible with rumination (distraction and reappraisal), and adaptive internal anger control strategies were considered.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 388 participants recruited through the snowball technique, 168 men (43.30%) and 220 women (56.70%), aged from 18 to 86 (M = 37.80; SD = 16.30); the majority had secondary school (32.73%) or higher education (51.80%) level, and were working (47.42%) or studying (26.55%).

Measurements

Once informed consent was signed, all participants were asked to complete the following assessment protocol, in this order:

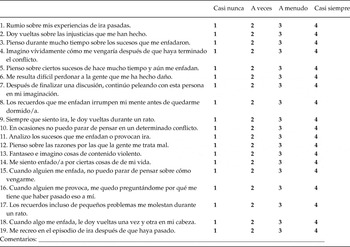

The Anger Rumination Scale (ARS; Sukhodolsky et al., Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001) in the Spanish version. This is composed of 19 items that in a 4-point Likert scale (“1-almost never” – “4-almost always”) quantify anger rumination frequency. The ARS shows adequate reliability and validity, not only in the original version but also in the British, Chinese, and French ones (Maxwell et al., Reference Maxwell, Sukhodolsky, Chow and Wong2005; Reynes et al., Reference Reynes, Berthouze-Aranda, Guillet-Descas, Chabaud and Deflandre2013). The original test consists of the four subscales described above: Angry Afterthoughts (ARS-AA), Angry Memories (ARS-AM), Thoughts of Revenge (ARS-TR), and Understanding of Causes (ARS-UC). The psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the ARS are discussed below.

Spielberger´s State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory 2 in its Spanish version (STAXI-2; Miguel-Tobal, Casado, Cano-Vindel, & Spielberger, Reference Miguel-Tobal, Casado, Cano-Vindel and Spielberger2001). STAXI-2 is a psychometrically sound self-report inventory developed to quantify the different facets of the anger construct with adequate reliability and validity values (Miguel-Tobal et al., Reference Miguel-Tobal, Casado, Cano-Vindel and Spielberger2001). Specifically, the Anger Trait (STAXI-AT), Anger-Out (STAXI-AO), Anger-In (STAXI-AI), Anger Control-Out (STAXI-CO), and Anger Control-In (STAXI-CI) subscales were applied. The STAXI-2 subscales applied in this study fulfilled the standards of internal consistency (α coefficient): STAXI-AT (.85), STAXI-AO (.65), STAXI-AI (.63), STAXI-CO (.86), and STAXI-AI (.83).

The Spanish version of the Trait scale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-T; Spielberger, Gorsuch, & Lushene, Reference Spielberger, Gorsuch and Lushene1982). STAI-T is composed of 20 items which, in a 4-point Likert scale (“0-almost never” – “3-almost always”), quantify the frequency with which people tend to experience anxiety in general, showing excellent psychometric properties. In the present study, the scale's internal consistency (α coefficient) was also high (α = .89).

The Spanish version of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ; Meyer, Miller, Metzger, & Borkovec, Reference Meyer, Miller, Metzger and Borkovec1990), published by Comeche, Díaz, and Vallejo (Reference Comeche, Díaz and Vallejo1995). It is composed of 16 items which, in a 5-point Likert scale (“1-not at all typical of me” – “5-very typical of me”), quantify the trait of worry, characterized by being stable and unspecific. The PSWQ’s Spanish version has shown adequate psychometric properties, that have been supported by Comeche et al. (Reference Comeche, Díaz and Vallejo1995) and more recently by Sandín, Chorot, Valiente, and Lostao (Reference Sandín, Chorot, Valiente and Lostao2009), as well as the present study (α = .87).

The Spanish version of the Beck Depression Inventory II – BDI-II short form (BDI-II; Sanz, García-Vera, Fortún, & Espinosa, Reference Sanz, García-Vera, Fortún and Espinosa2005) was used. It was developed based on the BDI-II Spanish version (Beck, Steer, & Brown, Reference Beck, Steer and Brown2011, adapted by Sanz and Vázquez). It is a self-report instrument composed of 11 items that attempts to identify and quantify the depressive symptomatology severity in the previous two weeks, according to DSM-IV diagnostic criteria (APA, 2000). Its adequate reliability and validity properties have been shown not only in patients with different psychological disorders but also in adult samples recruited from the general population, as well as in university students (Sanz et al., Reference Sanz, García-Vera, Fortún and Espinosa2005). In the present study, the scale's internal consistency was good (α = .80).

The Thought Control Questionnaire (TCQ; Wells & Davies, Reference Wells and Davies1994), translated into Spanish by Pérez-Nieto, Redondo-Delgado, León-Mateos, and Bueno (Reference Pérez-Nieto, Redondo-Delgado, León-Mateos and Bueno2010) was used, showing adequate reliability and validity. It is composed of 30 items, with a 4-point Likert scale (“1-never” – “4-almost always”), that quantify the use of different coping skills aimed at managing intrusive or stressful thoughts. In this study, the Distraction (TCQ-D), Worry (TCQ-W), Punishment (TCQ-P), and Reappraisal (TCQ-R) subscales were applied. The Social Control subscale was not used because it is not theoretically related to the core constructs of this study (anger and rumination). In this research, the majority of TCQ subscales showed an adequate internal consistency (α coefficient): TCQ-D (.75), TCQ-W (.62), TCQ-P (.62), and TCQ-R (.57).

Procedure

In order to translate the ARS, a blind backtranslation procedure was used according to international standards (Muñiz et al., Reference Muñiz, Elosúa and Hambleton2013) by a multidisciplinary group of 5 experts (three from Spain and two from the U.S.) in anger rumination, test construction, and language translation. Firstly, two independent translations into Spanish were conducted (forward translation). Then, the group of experts discussed these two translations in relation, not only to grammar or semantic criteria, but also to its cultural and linguistic adequacy, from which emerged an initial ARS Spanish version. This preliminary version was applied to a group of Spanish Psychology students, in order to test its adequacy. Then, the Spanish version was again translated into English by a bilingual blind translator from the U.S. in order to compare it with the original version (backward translation). After some minor changes, the final Spanish version of the ARS was ready to use (see Appendix).

After that, fifty-eight Psychology undergraduates at Universidad Camilo José Cela were carefully trained in applying the assessment protocol described above. It had to be applied to six persons according to sex and age a priori criteria (a woman and a man from each of the following three age groups: 18 to 29, 30 to 49, and over 50) as well as to themselves.

Results

Descriptive statistics and cross-cultural comparison

Table 1 shows the means and standard deviations by gender of the ARS total score and subscales obtained in the Spanish sample together with those previously obtained in U.S. (Sukhodolsky et al., Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001), British, and Chinese samples (Maxwell et al., Reference Maxwell, Sukhodolsky, Chow and Wong2005). The similarity of the results supports the robustness of the anger rumination construct across different cultures.

Table 1. Means and standard deviations for the ARS measures as a function of gender in Spanish, U. S. (Sukhodolsky et al., Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001), British, and Chinese samples (Maxwell et al., Reference Maxwell, Sukhodolsky, Chow and Wong2005)

Note: N = 388. ARS-TOTAL: Anger Rumination Scale. ARS-AA: Anger Afterthoughts ARS subscale. ARS-TR: Thoughts of Revenge ARS subscale. ARS-AM: Angry Memories ARS subscale. ARS-UC: Understanding of Causes ARS subscale.

Confirmatory factor analysis

In order to replicate the original factor structure found by Sukhodolsky et al. (Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001) a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using Mplus 7 software (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2012). Data screening indicated no substantial departures from univariate normality (skewness: M = .91, SD = .65, Min = .15, Max = 2.43; kurtosis: M = .59, SD = 1.91, Min = –.90, Max = 5.84), with all skewness values less than 3 and all kurtosis values less than 10 (Kline, Reference Kline2011). Nevertheless, the normalized Mardia’s coefficient showed a value of 25.92, above the cutoff point of 5.00 suggested by Bentler (Reference Bentler2005). Accordingly, the MLM estimator was used in order to obtain maximum-likelihood parameter estimates with standard errors and a mean-adjusted chi-square test statistic, the Satorra-Bentler Scaled χ2 (S-B χ2; Satorra & Bentler, Reference Satorra, Bentler, von Eye and Clogg1994), that are robust to non-normality. Model fit was also assessed using the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), following the criteria suggested by Kline (Reference Kline2011) and Schreiber, Nora, Stage, Barlow and King (Reference Schreiber, Nora, Stage, Barlow and King2006). In his regard, evidence for model fit varied somewhat by index (S-B χ2(146) = 370.54, p < .00005; CFI = .89; TLI = .88; RMSEA = .06; SRMR = .06). CFI and TLI values less than .90 represent a mediocre model fit, whereas a RMSEA value less than .08 and a SRMR value less than .10 indicate an acceptable model fit. Based on the modification indices, errors 11 and 12 were allowed to correlate. As a result, the model showed an adequate fit to the data (S-B χ2(145) = 323.26, p < .00005; CFI = .92; TLI = .90; RMSEA = .06; SRMR = .05). The Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square difference test (Satorra & Bentler, Reference Satorra and Bentler2001) yielded a significant value (∆S-B χ2(1) = 47.27, p < .00005), revealing that incorporation of the covariance between errors 11 and 12 made a substantial improvement in model fit. Therefore, the CFA replicated the original four-factor structure of the ARS: Angry Memories, Thoughts of Revenge, Angry Afterthoughts, and Understanding of Causes. Figure 1 shows the standardized factor solution, with all factor loadings and covariances statistically significant at the .001 level.

Figure 1. Confirmatory factor analysis for the ARS.

Reliability analysis

The internal consistency of the ARS measures was estimated with the Cronbach's alpha and the split-half coefficients. According to standard criteria, internal consistency was excellent for the ARS total scale (α = .89, split-half = .88), good for ARS-AA (α = .83, split-half = .84) and ARS-AM (α = .78, split-half = .69), and sufficient for ARS-TR (α = .67, split-half = .70) and ARS-UC (α = .64, split-half = .61). Nevertheless, it is worth noting that these last two subscales consist of only four items each.

Convergent and discriminant validity

Evidence of convergent and discriminant validity was first obtained by analyzing the Pearson correlations between the ARS measures and the other variables of the study (Table 2). Regarding convergent validity, as expected, positive and significant correlations were observed between STAXI-AI and each of the ARS measures (ranging from .38 to .46, all p < .0005), except ARS-TR, with which the correlation was lower (r xy = .26, p < .0005). With regard to the PSWQ, the correlations ranged from .44 to .49 (all p < .0005), except ARS-TR, with a correlation value of .20 (p < .0005). Finally, in relation to the TCQ-W subscale, the correlations ranged from .39 to .50 (all p < .0005), except ARS-TR (.23, p < .0005).

Table 2. Pearson’ correlations between the different scales and subscales included in this research

Note: N = 388. *(p < .05); **(p < .01); ***(p < .0005). ARS-AA: Anger Afterthoughts ARS subscale. ARS-TR: Thoughts of Revenge ARS subscale. ARS-AM: Angry Memories ARS subscale. ARS-UC: Understanding of Causes ARS subscale. ARS-TOTAL: Anger Rumination Scale. STAI-T: Anxiety Trait-State Inventory - Trait scale. PSWQ: Pennsylvania State Worry Questionnaire. BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-II short form. STAXI-AT: Anger Trait STAXI 2 scale. STAXI-AO: Anger-Out STAXI 2 scale. STAXI-AI: Anger-In STAXI 2 scale. STAXI-CO: Anger Control-Out STAXI 2 scale. STAXI-CI: Anger Control-In STAXI 2 scale. TCQ-D: Distraction Thought Control Questionnaire subscale. TCQ-W: Worry Thought Control Questionnaire subscale. TCQ-P: Punishment Thought Control Questionnaire subscale. TCQ-R: Reappraisal Thought Control Questionnaire subscale.

Regarding discriminant validity, as expected, the correlations of the ARS measures with STAI-T were moderated and significant (values from .32 to .62, p < .0005), whereas the correlations with the BDI-II short form were lower but also significant (.21 to .42, p < .0005). However, contrary to expectations, these values were not substantially lower than those obtained with measures of anger and worry. Finally, in relation to the divergence from other mechanisms of cognitive control independent of rumination, the ARS measures showed low and generally non-significant correlations with TCQ-D (values from –.17 to –.02) and STAXI-CI (values from –.13 to –.11).

In order to further analyze the construct validity of the ARS measures, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed including all the variables in the study. Both the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (KMO = .87) and the Barlett’s test of sphericity (χ2(120) = 2600.10, p < .0005) indicated the factorability of the correlation matrix. The EFA was conducted using maximum likelihood estimation with oblique rotation. Although the Kaiser criterion suggested a four-factor solution, the parallel analysis indicated that three factors should be retained (Figure 2). The three factors accounted for 47.73% of the total variance (31.25%, 10.39%, and 6.09%, respectively). Table 3 shows the rotated factor loadings for all measures. ARS-AM, ARS-UC, STAI-T, PSWQ, BDI-II, STAXI-AI, TCQ-W, and TCQ-P mainly loaded on factor 1; STAXI-CI, TCQ-D, and TCQ-R loaded on factor 2; and ARS-TR, STAXI-AT, STAXI-AO, and STAXI-CO loaded on factor 3. ARS-AA loaded similarly on factors 1 and 2. So, the first factor mainly included measures related to negative emotions, rumination, worry, and anger rumination, therefore it was called Factor 1-Emotion Rumination; the second factor was related to an adaptive control of anger, so it was named Factor 2-Cognitive Control/Coping; and the third factor included measures associated with anger expression, so it was called Factor 3-Anger Out. The correlation between factors 1 and 2 was .14, between factors 1 and 3 was .51, and between factors 2 and 3 was –.05.

Figure 2. Parallel analysis based on 100 random datasets (388 cases × 16 variables).

Table 3. Pattern matrix (direct oblimin rotation)

Note: N = 388. ARS-AA: Anger Afterthoughts ARS subscale. ARS-TR: Thoughts of Revenge ARS subscale. ARS-AM: Angry Memories ARS subscale. ARS-UC: Understanding of Causes ARS subscale. ARS-TOTAL: Anger Rumination Scale. STAI-T: Anxiety Trait-State Inventory - Trait scale. PSWQ: Pennsylvania State Worry Questionnaire. BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-II short form. STAXI-AT: Anger Trait STAXI 2 scale. STAXI-AO: Anger-Out STAXI 2 scale. STAXI-AI: Anger-In STAXI 2 scale. STAXI-CO: Anger Control-Out STAXI 2 scale. STAXI-CI: Anger Control-In STAXI 2 scale. TCQ-D: Distraction Thought Control Questionnaire subscale. TCQ-W: Worry Thought Control Questionnaire subscale. TCQ-P: Punishment Thought Control Questionnaire subscale. TCQ-R: Reappraisal Thought Control Questionnaire subscale.

Sex and age-related differences

In order to analyze individual differences in the set of ARS subscales as a function of age and sex, a two-way multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed on the ARS measures with sex and age group (18–29, 30–49, 50+) as independent variables. Multivariate statistics showed a significant effect for sex (λ = .90, F(4, 379) = 10.27, p < .0005, η2 = .10), but not for age group (λ = .97, F(8, 758) = 1.73, p = .09, η2 = .02), nor for the interaction term (λ = .99, F(8, 758) = .68, p = .71, η2 = .01). More specifically, univariate statistics showed a significant effect of sex on ARS-TR (F(1, 382) = 14.91, p < .0005, η2= .04) and ARS-AM (F(1, 382) = 5.16, p < .05, η2 = .01), favoring men and women, respectively.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to adapt the ARS, originally developed by Sukhodolsky et al. (Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001), to Spanish, and to validate it in a general population sample. As with previous adaptations (Maxwell et al., Reference Maxwell, Sukhodolsky, Chow and Wong2005; Reynes et al., Reference Reynes, Berthouze-Aranda, Guillet-Descas, Chabaud and Deflandre2013), the original four-factor structure was replicated with the Spanish version. This result contributes to strengthen the ARS factorial validity and supports a construct structure for anger rumination relatively independent of languages and cultures. Interestingly, the ARS structure depends on the angry rumination content (present or past angry events, revenge, or counterfactual thinking), which, in part, is consistent with Beck´s anger cognitive framework (Beck, Reference Beck1999). In fact, similar structures have emerged in other tests developed to assess angry automatic thoughts, both in the U.S. (i.e., Deffenbacher, Petrilli, Lynch, Oetting, & Swaim, Reference Deffenbacher, Petrilli, Lynch, Oetting and Swaim2003) and Spain (Magán, Reference Magán2010).

Regarding its psychometric properties, the Spanish version of the ARS has shown adequate reliability, reaching an optimal level of internal consistency in the total scale. In relation to validity analyses, the Spanish ARS has shown evidence of convergent and discriminant validity. As for convergent validity, the ARS seems to be capturing both the internal experience of anger and rumination processes, given the moderate and direct correlations with anger suppression, rumination trait, and worry as a strategy to manage stressful and intrusive thoughts. Regarding discriminant validity, however, our data does not allow to conclude that the ARS discriminates well from other emotional constructs like trait anxiety or depressive mood. Nevertheless, that could be explained by the overlap between negative emotions, as is shown in different studies in which rumination is considered a vulnerability factor common to the three main negative emotions (McEvoy & Brans, Reference McEvoy and Brans2013; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., Reference Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco and Lyubomirsky2008; Wilkowski & Robinson, Reference Wilkowski and Robinson2010). In this regard, rumination seems to be a transdiagnostic process in a wide range of psychological disorders (McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, Reference McLaughlin and Nolen-Hoeksema2011). However, it is also possible that the ARS focuses more on the rumination process itself than on the specific emotion in which people are perseverating. In such case, our results would be congruent with the dimensional conception of the affective space (Russell & Feldman-Barrett, Reference Russell and Feldman-Barrett1999), in which all the basic emotions and their components are included, underlining the existence of confusing limits between basic emotions (Frijda, Reference Frijda1988). Regarding other cognitive processes, the Spanish ARS discriminated well from processes incompatible with rumination, like distraction or internal anger control.

The results of the EFA applied to all the variables in the study provided further information regarding the ARS construct validity, suggesting a three-factor solution. Factor 1-Emotion Rumination, included the majority of measures related to rumination and negative emotions. According to Nolen-Hoeksema et al. (Reference Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco and Lyubomirsky2008) conceptualization of rumination, there is a well-established relationship between rumination, depressive mood, anxiety, and general emotional disorders (McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, Reference McLaughlin and Nolen-Hoeksema2011); and the latest anger frameworks suggest that rumination plays a key role in anger state regulation (Wilkowski & Robinson, Reference Wilkowski and Robinson2010). Moreover, recent research shows that not only rumination but also worry would be able to predict depression, because of being a repetitive thinking with a negative content (McEvoy & Brans, Reference McEvoy and Brans2013). The results of the EFA are consistent with those observations, since all the ARS subscales, except Thoughts of Revenge, loaded together with the worry measures on Factor 1. This would also be consistent with the similarity between rumination and worry (Wells, Reference Wells2000). Therefore, Factor 1 would constitute an evidence of convergent validity between measures of anger rumination and other forms of negative and perseverative thinking as well as anger emotion.

On the other hand, measures of adaptive cognitive processes other than rumination, directed at regulating anger experience, like reappraisal or distraction, loaded on Factor 2-Cognitive Control/Coping, which is in line with previous studies (Fabiansson, Denson, Moulds, Grisham, & Schira, Reference Fabiansson, Denson, Moulds, Grisham and Schira2012). In this regard, psychological treatments based on training coping skills like distraction and cognitive reappraisal are effective in enhancing an adaptive anger regulation and a constructive anger expression pattern (Denson, Moulds, & Grisham, Reference Denson, Moulds and Grisham2012). Factor 2, thus, would constitute an evidence of discriminant validity for the ARS measures.

Finally, all the measures related to external anger expression loaded together on Factor 3-Anger Out. The Anger-Out and Anger-Trait subscales of the STAXI-2 together with Angry Afterthoughts and Thoughts of Revenge showed high loadings on Factor 3, whereas the loading of Anger-In was negligible. These results are consistent with Denson (Reference Denson2013), because, despite being a skill to regulate emotions, anger rumination may also temporarily reduce self-control and boost aggressive behaviours.

Although gender and age-related differences in anger are well-established (Miguel-Tobal et al., Reference Miguel-Tobal, Casado, Cano-Vindel and Spielberger2001), only two significant differences between sexes emerged with the Spanish ARS, similar to those found by Sukhodolsky et al. (Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001). Specifically, men ruminated more frequently about how to get revenge than women, whereas women perseverated more about angry memories than men. These results could be explained because of the profound social and cultural content anger has, which could be establishing which anger expression patterns and cognitive patterns are socially accepted for men and women.

Nevertheless, according to the conceptualization of anger as a basic and universal emotion, anger could be referred not only to its experience and expression but also to its cognitive components and processes. In this regard, the similarity of the normative data obtained in the present study compared to those obtained in previous research, supports the robustness of the anger rumination construct across different cultures, like English-speaking (U.S. and Great Britain), French, Latin (Spanish), and Chinese (Hong Kong) (Maxwell et al., Reference Maxwell, Sukhodolsky, Chow and Wong2005; Reynes et al., Reference Reynes, Berthouze-Aranda, Guillet-Descas, Chabaud and Deflandre2013; Sukhodolsky et al., Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001).

Although further research is needed in order to validate the Spanish version of the ARS in clinical populations, our results allow us to conclude that a psychometrically sound Spanish ARS is now available, with a promising application in the field of clinical and health psychology.

Appendix

ERI

Instrucciones: Todo el mudo se enfada y se siente frustrado de manera ocasional pero la gente piensa sobre sus episodios de ira de manera distinta. Las siguientes frases describen los diferentes modos que la gente podría tener de recordar o pensar sobre sus experiencias de ira. Por favor, lea cada frase y después rodee el número que mejor describa cómo suele pensar sobre sus episodios de ira. No hay respuestas correctas ni incorrectas en este cuestionario, responda de manera sincera. Por favor, conteste a todos los ítems.