The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR, American Psychological Association, 2000) defines a personality disorder in terms of “an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adolescence or early adulthood, is stable overtime and leads to distress or impairment” (American Psychiatric Association, 2000, p. 685). The DSM-IV-TR classification places personality disorders in Axis II of its multiaxial system in order to distinguish them from clinical disorders in Axis I.

Despite the established definitions, there is a high degree of controversy surrounding the conception of personality disorders that has led the American Psychiatric Association to propose a re-formulation of their classification for the new edition of the DSM (DSM-V), planned to appear in May 2013. The APA working group on personality disorders has recommended a significant change of emphasis in the method of formulating assessments and diagnoses concerning personality psychopathology. Numerous authors and investigations (e.g., Tyrer et al., Reference Tyrer, Coombs, Ibrahimi, Mathilakath, Bajaj, Ranger and Din2007; Widiger, Reference Widiger2003; Widiger & Samuel, Reference Widiger and Samuel2005; Widiger & Sanderson, Reference Widiger, Sanderson and Livesley1995) have pointed to the shortcomings of the current categorical classification system for mental disorders, which in some cases can be attributed to an excess of competing diagnoses (Bornstein, Reference Bornstein1997; Lenzerweger, Lane, Loranger, & Kessler, Reference Lenzenweger, Lane, Loranger and Kessler2007; Oldham et al., Reference Oldham, Skodol, Kellman, Hyler, Doidge, Rosnick and Gallaher1995; Trull, Sher, Minks-Brown, Durbin, & Burr, Reference Trull, Sher, Minks-Brown, Durbin and Burr2000) and in others to the blurred boundaries between different diagnoses (Phillips, Price, Greenberg, & Rasmusen, Reference Phillips, Price, Greenberg, Rasmusen, Phillips, First and Pincus2003). Consequently, some researchers have advocated the creation of a dimensional system for the classification of personality disorders. In this sense O'Connor (Reference O’Connor2005) concludes that personality and personality disorders reflect similar structural combinations of traits, with a moderate long-term stability that may differ in intensity, degree of disadaptation and behavioral consequences. Pedrero (Reference Pedrero2009), divides into 4 groups the dimensional models that have been used to attempt to define personality variants in clinical terms: (a) factorial models, mainly based on the five major factors defined by Trull and McCrae (Reference Trull, McCrae, Costa and Widiger2002); (b) neurobiological models, especially those proposed by Cloninger, Svrakic, and Przybeck (Reference Cloninger, Svrakic and Przybeck1993), Depue and Lezenweger (Reference Depue, Lenzenweger and Livesley2001), or Siever and Davis (Reference Siever and Davis1991); (c) Millon's integrative model (Millon & Davis, Reference Millon, Davis, Clarkin and Lenzenweger1996); and, finally, (d) hybrid models, such as Eysenck's three-dimensional models (1991), or the categorial consideration of categorial criteria (Oldham, Reference Oldham, Oldham, Skodol and Bender2005).

Millon's integrative model of personality disorders (Millon & Davis, Reference Millon, Davis, Clarkin and Lenzenweger1996; Millon, Reference Millon2011) is now based on the fundamental concept of evolution, and applies various different perspectives (biological, interpersonal, cognitive and psychodynamic) to bring out eight aspects of the manifestation of personality: state of mind/temperament, morphological structure, interpersonal behavior, observable behavior, cognitive style, self-image, object representations and defense mechanisms. The model proposes an explanation of the structure of personality styles on the basis of the principles of ecological adaptation. Based in this integrative and evolutionary model, Millon classifies personality disorders according to four main dimensions, as follows: Personalities with difficulties in taking pleasure (i.e., with schizoid, avoidant or depressive disorders), personalities with interpersonal problems (with dependent, histrionic, narcissistic or antisocial disorders), personalities with intrapsychic conflicts (with aggressive, compulsive, negativistic or masochistic disorders) and personalities with structural deficits (with schizotypal, borderline or paranoid disorders). The latter three pathological personality patterns (schizotypal, borderline and paranoid) represent, in terms of Millon's theory, more advanced stages of personality pathology and structural impairment.

Despite the controversy generated by its conceptualization and classification, it is nevertheless clear that the concept of personality disorder is closely linked to an impairment of the psychological function that is manifested through an impairment of, and deterioration in, interpersonal relationships. In fact, numerous studies indicate a poor quality of social relationships among patients with personality disorders (Andreoli, Gressot, Aapro, Tricot, & Gognalons, Reference Andreoli, Gressot, Aapro, Tricot and Gognalons1989; Dickinson & Pincus, Reference Dickinson and Pincus2003; Modestin & Williger, Reference Modestin and Williger1989; Levy et al., Reference Levy, Becker, Grilo, Mattanah, Garnet, Quinlan and McGlashan1999; Skodol et al., Reference Skodol, Gunderson, McGlashan, Dyck, Stout, Bender and Ildham2002).

A very important aspect of interpersonal relationships of those suffering from personality disorders that has hitherto received little attention, is the communication style through which these individuals express themselves. Since communication styles are enduring behavioral patterns that can be associated with personality traits the purpose of the present study is to explore the relationship between both variables.

Theoretical background on communication styles

Vries, Bakker-Pieper, Alting Siberg, van Gameren and Vlug, (2009) define communication style as 'the characteristic way a person sends verbal, paraverbal and nonverbal signals in social interactions denoting (a) who he or she is or wants to (appear to) be, (b) how he or she tends to relate to people with whom he or she interacts, and (c) in what way his or her messages should usually be interpreted’ (p. 179). According to Norton (Reference Norton1983), by “communication style” we mean the style used by an individual when interacting with others. Communication is expressed on two levels: (a) content of the information, the information itself; and (b) style, i.e., the way in which the information is communicated. The communication style determines how the information transmitted is understood and responded to. Norton's construct of communication styles consists of the following ten styles: (a) dominant style, in which the individual controls social situations; (b) dramatic style, in which the individual communicates by emphasizing the content transmitted in a very animated way; (c) contentious style, characterized by negative and aggressive communication; (d) animated style, in which physical, non-verbal signs of communication are emphasized; (e) impression-leaving style, characterized by the exhibition of stimuli that are easy to remember; (f) relaxed style, in which the person does not exhibit signs of anxiety or nervousness; (g) attentive style, characterized by a sense of empathy and of attentive listening; (h) open style, characterized by an expansive, sociable, direct, frank, extrovert and accessible attitude; (i) friendly style, characterized by a positive recognition of the other person; and (j) precise style, in which the person transmits the content in a precise, accurate and careful communication style.

Results of some studies are consistent in that communicator style is important in how people relate to and are perceived by others (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Williams, Boyle, Molloy, McKenna, Palermo and Lewis2011). In turn, according to Leung and Harris (Reference Leung and Harris2001), interpersonal communication behavior helps in developing, reinforcing and maintaining personality dispositions.

Some studies from different psychological fields are consistent in showing that communication styles are relevant for interpersonal relationships (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Williams, Boyle, Molloy, McKenna, Palermo and Lewis2011). In the context of health care, Brown et al. found that occupational therapy undergraduate students had an important preference for friendly and attentive communication styles indicating an underlying interest in the care and welfare of other people. Similarly, in a study exploring the reasons for an incorrect usage of oral contraceptive pills, Schrader and Schrader (Reference Schrader and Schrader2001) found that friendly and attentive styles were linked to better patient’s outcomes and collaboration as perceived by health care practitioners, whereas the dramatic dimension was negatively correlated to patient comprehension of oral contraceptive use. In another study using Norton's Theory of Communicator Styles as a framework to identify the effect of three specific communication styles -dominant, contentious and attentive- on nurses' perceptions of collaboration with physicians, participants who adopted a preference for an attentive style had better perceptions of interdisciplinary collaboration (Coeling & Cukr, Reference Coeling and Cukr2000). Research in the educational domain also suggests that teacher’s supportive communication style is associated with greater satisfaction among students (Prisbell, Reference Prisbell1994), while in organizational settings Vries, Hoff, and Ridder (Reference Vries, Hooff and Ridder2006) found that team members were more willing to share knowledge with those who were more agreeable and extroverted in their communication style. Moreover, research on leadership shows that leader’s supportiveness enhances knowledge donating behaviors to the leader and knowledge collecting behaviors from the leader, and also that a human-oriented leadership style is characterized by a supportive communication style (Vries, Bakker-Pieper, & Oostenveld, Reference Vries, Bakker-Pieper and Oostenveld2010).

Gender differences in personality disorders and communication styles

Regarding gender, some conflicting results, both in personality disorders and communication styles research, have been found. On the one hand, the DSM-IV-TR explicitly states that there are some differences between males and females in terms of personality disorders’ frequency of occurrence. Antisocial, schizoid, schizotypal and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders are more frequently found in males than in females, while it would seem that borderline, histrionic and dependent personality disorders are more common among females than among males. It has been remarked in various studies that one of the most notable differences is observed in relation to antisocial and borderline personality disorders (Cale & Lilienfeld, Reference Cale and Lilienfeld2002; Ekselius, Lindstrom, von Knorring, Bodlund, & Kullgren, Reference Ekselius, Lindstrom, von Knorring, Bodlund and Kullgren1994; Golomb, Fava, Abraham, & Rosenbaum, Reference Golomb, Fava, Abraham and Rosenbaum1995; Linzer et al., Reference Linzer, Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, Hahn, Brody and deGruy1996, Paris, Reference Paris2004). On the other hand, studies addressing gender differences in communication styles have given disparate results (Canary & Hause, Reference Canary and Hause1993; Ibrahim & Ismael, Reference Ibrahim and Ismael2007; Montgomery & Norton, Reference Montgomery and Norton1981; Netshitangani, Reference Netshitangani2008). A previous study of a university population showed statistically significant differences between males and females in relation to attentive, precise and dramatic styles (Prior et al., Reference Prior, Manzano, Villar, Caparrós, Juan and Luz2011). Females exhibited an attentive style to a greater extent than men but, on the other hand, their scores for the precise and dramatic styles were lower.

Despite the influence of communication in interpersonal relationships, effective social and professional adjustment, few empirical studies have addressed the predictive power of dysfunctional personality patterns over individuals’ communication styles. With a view to contributing further information concerning the different psychological processes involved in the manifestation of personality disorders as a dimensional construct, the objectives of this paper will be as follows: (a) to analyze the relationship between personality patterns and communication styles, and (b) to determine to what extent individual’s personality patterns and gender enable us to predict their communication styles.

Method

Participants

The sample for this study consisted of 529 Spanish university students from a population out of 9718 students. After obtaining the corresponding permits, a representative sample from each field of study or school treated as strata (Education Sciences and Psychology, Arts, Science, Law, Business and Economics, School of Nursing and Polytechnic School) was selected using the random cluster sampling method, in which the cluster was the course. Of the total number of students in the sample, 309 were females and 220 were males, with an average age of 21 years (SD = 3.5).

Measures

For the assessment of personality disorders we used Millon Multiaxial Clinical Inventory (MCMI-III, Millon, Davis, & Millon, (2007), Spanish translation by Cardenal & Sánchez-López, Reference Cardenal and Sánchez-López2007). The MCMI-III is a 175 item, self-report questionnaire that measures 11 clinical personality patterns, 3 traits of severe personality pathology, 7 syndromes of moderate severity, 3 severe syndromes and a validity scale and 3 modifying indices. The personality disorders scales cover major diagnostic criteria of DSM-IV (Millon, Davis, & Millon, Reference Millon, Davis and Millon1997). The MCMI-III is a useful inventory that contributed to the categorical and dimensional assessment of personality disorders (Strack & Millon, Reference Strack and Millon2007). In our study we have used the scales relating to personality disorders (11 clinical personality patterns plus 3 severe pathology traits).

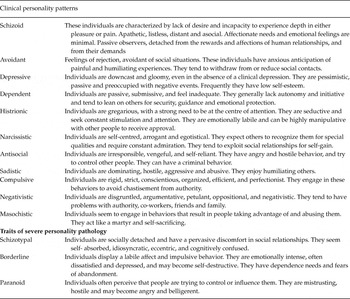

In table 1 we can see a brief description of the scales. The internal consistency coefficients for this Spanish population (Table 2) are very similar to those of the original version (Millon & Meagher, Reference Millon, Meagher and Hersen2004).

Table. 1. Brief Description of Clinical personality patterns and traits of severe personality typology of MCMI-III.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics, results of t test by gender and reliability of MCMI-III and CSM scales (Cronbach’s α).

Communication styles were assessed using Norton's (Reference Norton1978) Communicator Style Measure (CSM) in the Spanish version (Villar, Reference Villar2006). This questionnaire establishes scores for 10 independent sub-scales that are identified as 10 different communication styles. Internal consistency coefficients, Cronbach’s alpha, are showed in table 2. Previous studies have reported very similar internal consistencies (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Williams, Boyle, Molloy, McKenna, Palermo and Lewis2011). Despite some alphas are low this is an acceptable level when the construct consists of few items as it is in this case (Nunnally & Bernstein, Reference Nunnally and Bernstein1994; Streiner & Norman, Reference Streiner and Norman1995).

Procedure

As a part of a broader study, a set of questionnaires were administered to the participants. Once contact had been established and accepted by the coordinators and teaching staff responsible for the courses, the tests were conducted inside the lecture-rooms. Students were informed of the voluntary nature of their participation and that data would be treated in confidentially. Students' answers were processed digitally using an optical reader system. A total of 53 cases were excluded because they didn’t complete the questionnaires correctly or because their MCMI-III scores’ profile was invalid

Results

The means, standard deviations and results of t test by gender for each of the study variables are presented in table 2. Since statistically significant differences were found between male and female in both personality patterns and communication styles, descriptive statistics have been calculated separately for both groups. As can be observed in Table 2, results show significant differences between males and females in seven of the clinical personality patterns. Male exhibit higher average scores in schizoid, narcissistic and antisocial behavior and females in avoidant, depressive and masochistic scales. High standard deviations in some scales are indicative of the scores dispersion. No significant differences were found for any of the severe pathology traits. With respect to communication styles, females scored significantly higher than males in the attentive style while the reverse was truth for precise, dramatic, and dominant styles.

Relationship between personality disorders and communication styles

In order to determine the relationship between these two variables, we analyzed bivariate correlations between the 11 clinical personality patterns, the 3 severe pathology traits from the MCMI-III and the 10 communication styles.

As can be observed in Table 3, there are numerous significant relationships between the personality disorders assessed through the MCMI-III and communication styles. In some cases the magnitude of the relationship, although significant, is fairly low, but in other cases the coefficients are situated in the region of an absolute value of 0.40. This is the case for the following associations: the schizoid pattern shows a significant negative association, from highest to lowest magnitude, in the case of the open, animated, friendly, dramatic, impression-leaving, dominant, attentive and relaxed styles. The avoidant pattern also exhibits significant negative associations in the case of all communication styles except the contentious and the attentive. The depressive style exhibits significant positive associations, although of a lower magnitude, in relation to the contentious style and the attentive style, and significant negative associations in the case of the relaxed style and the open style. The pattern for dependence exhibits a significant negative correlation in the case of the dominant and relaxed styles. With regard to the histrionic and narcissistic patterns, both are related in a significant positive manner with all the communication styles, with the magnitude of the correlation coefficients being particularly notable in the case of the open, animated, dramatic and impression-leaving styles on the one hand, and the dominant and impression-leaving styles on the other. The scale relating to the antisocial pattern exhibits a significant positive association in the case of the contentious, dramatic, dominant, precise and open styles. The correlations show that the aggressive pattern is associated in a significant positive manner with the contentious style, and to a lesser extent with the dominant, precise, impression-leaving and dramatic styles. This same pattern exhibits a significant correlation in the opposite sense in the case of the friendly style. With regard to the compulsive pattern, we can observe that, although the magnitude of the associations is not very high, this pattern is related in a significant positive manner with the attentive and friendly styles, and in a significant negative manner with the contentious, open, dramatic and animated styles. Communication styles that exhibit a significant positive association with the negativistic pattern are the contentious, attentive and precise styles, while the friendly style has a significant negative association in this respect. The masochistic pattern exhibits a significant negative relationship with the relaxed, open and dominant styles and a significant positive association with the contentious style. With regard to the measures of severe pathology we can highlight the significant positive association between the schizotypal and contentious styles, and significant negative associations with the relaxed and open styles. The borderline disorder exhibits a significant positive relationship with the contentious and precise styles. Finally, the paranoid disorder is associated in a significant positive manner with the contentious, precise, attentive and impression-leaving styles, and in a negative manner with the open style.

Table 3. Correlations matrix between personality disorders and communication styles in the overall sample.

* < .01; **< .001

Correlations in the case of males follow a very similar pattern to that of the overall sample, although with some differences. Data show that the impression-leaving style maintains a significant positive relationship with the antisocial pattern (r = .186; p < .001) while the relaxed communication style exhibits significant negative correlations with aggressive (r = –.157; p < .01), negativistic (r = –.183; p<.001), masochistic (r = –.320; p < .001), schizotypal (r = –.215; p < .001), borderline (r = –.158; p < .01) and paranoid (r = –.180; p < .001) patterns. Finally, the dramatic style relates positively to negativistic (r = .158; p < .01) and borderline (r = .192; p < .001) patterns.

When comparing the females group with the overall sample, many of the relationships between personality patterns and communication styles lose their significance, although the direction of the association is maintained. Nevertheless, a significant negative correlation was found between the depressive pattern and the impression-leaving style (r = –.118; p < .01), whereas the antisocial pattern and the open style correlated significantly in a positive sense (r = .153; p < .001).

A predictive model of communication styles

In order to determine which dysfunctional personality variables may predict the use of different communication styles in this sample of university students, we then conducted a hierarchical regression for each of the dependent variables (i.e., the friendly, impression-leaving, relaxed, contentious, attentive, precise, animated, dramatic, open and dominant styles). The groups of variables (gender and personality disorders) were introduced at successive stages.

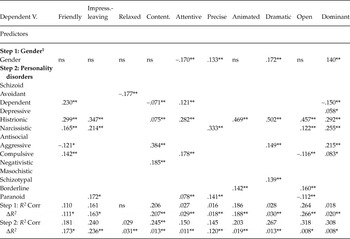

Table 4 shows the results obtained for each of these analyses. At the first stage the gender variable was introduced, which has a significant influence in the case of the attentive, precise, dramatic and dominant style variables. Personality disorders were introduced subsequently. Results show that in the case of the friendly communication style the patterns that have a significant influence are as follows: dependent, narcissistic, aggressive (in the negative sense) and compulsive styles. Personality patterns that have a significant influence on the impression-leaving communication style are the histrionic, narcissistic and paranoid personality patterns. With regard to the relaxed communication style, only the dependent pattern has a significant relationship with its prediction. The contentious communication style is significantly predicted by the histrionic, aggressive and negativistic patterns in the positive sense and by the dependent pattern in the negative sense. Gender and the dependent, histrionic, compulsive and paranoid patterns are the variables that predict the attentive communicative style, while the variables that help predict the precise style are gender and the narcissistic and paranoid patterns. Only two variables contribute to the prediction of the animated style, i.e., the histrionic and borderline personality disorders. Regarding the dramatic style, gender and the histrionic, aggressive and schizotypal patterns contribute to its prediction, while in the case of the open style, there are five predictive variables: two in the negative sense (the compulsive and the paranoid patterns); and three in the positive sense (histrionic, narcissistic and borderline patterns). To finish, we can observe that 7 different variables can help predict the dominant communication style: gender and the histrionic, narcissistic, antisocial, aggressive and compulsive personality patterns in the positive sense, and the depressive pattern in the negative sense.

Table 4. Hierarchical regression analysis for the prediction of communication styles (standard β coefficients)

1 Gender: female = 0; male = 1.* p < .05; **p < .001

Discussion

The first objective of this study was to focus on analyzing the relationship between personality and communication styles. With regard to this objective, results showed that communication styles characterized by positive recognition of others relate in a significant negative manner to the schizoid, schizotypal, aggressive and negativistic personality patterns, and positively to the narcissistic, histrionic and compulsive. This means that individuals who exhibit these personality traits relate with other people in a friendlier way, suggesting that personality characteristics associated with narcissistic, histrionic and compulsive patterns exhibit a positive communication style in non-clinical samples. Something similar occurs in the case of communication styles with positive characteristics such as relaxed, attentive, precise and open styles. It is worth noting that the histrionic personality pattern showed high correlations with every communication style; this result might be explained by the more dramatic and expressive behavioral pattern in histrionism. It should be noted that the histrionic and narcissistic patterns follow a very similar pattern of relationships with communication styles, while the compulsive pattern is differentiated from those above by the fact that it exhibits a significant negative relationship with the contentious, animated, dramatic and open styles. This leads us to associate it with a less “externalized” (behavior-focussed) and more “internalized” (emotion-focussed) personality pattern with regard to its model of communication (Egeland, Pianta, & Ogawa, Reference Egeland, Pianta and Ogawa1996; Mesman & Koot, Reference Mesman and Koot2000).

Other data to be highlighted are the significant negative correlations between the schizoid and schizotypal personality patterns and the majority of communication styles. High scores in these two patterns are related to a lower degree of sociability and accessibility, and a correspondingly higher tendency towards reserve and introversion, with little consideration for the other person. Both styles are marked by lack of empathy and active listening, and also reflect little control of social situations and a lack of animatedness in terms of the emphasis given to physical and non-verbal communication signs. Data confirm that these personality patterns appear to have difficulties in interpersonal communication that may have an impact on interpersonal relationships.

If we focus on communication patterns, it is the contentious style, characterized by negative and aggressive communication, which exhibits the largest number of significant positive associations with personality disorders (except for the compulsive pattern). In some cases these associations are of a high magnitude, such is the case for the aggressive or antisocial patterns. In general, the direction of the associations is very similar for males and females, although in the case of females some associations do not attain statistical significance.

With regard to the second objective of the study, aimed at determining to what extent personality patterns, assessed in terms of the MCMI-III and gender, make it possible to predict the use of certain communication styles as a means of expression, results show that the presence of certain personality disorders can help to predict the use of given communication styles. Gender is a significant variable in 4 of the 10 communication styles analyzed. The personality pattern that helps to predict the highest number of communication styles is histrionism. This pattern is present in the definition of the following styles: friendly, impression-leaving, contentious, attentive, animated, dramatic and dominant. All these communication styles contain positive aspects that are expressed in interpersonal relationships.

The pattern that helped predict the next highest number of communication styles is narcissism, which is part of the predictive model for the friendly, impression-leaving, precise, open and dominant styles, while the compulsive pattern helps to define friendly, attentive, open and dominant styles. With regard to histrionism, narcissism and the compulsive pattern, all three cases help to predict communication styles with clearly positive characteristics for interpersonal relationships. These results lead us to reflect on previous investigations carried out with the MCMI (Cardenal & Sánchez-López, Reference Cardenal and Sánchez-López2007), in which a curved model of the narcissistic, histrionic and compulsive scales is considered, meaning that it is the low and the high scores that indicate non-adaptation, whereas intermediate levels on these scales would reflect adaptive patterns, unlike what happens in relation to other scales.

The dependent personality pattern enables us to predict a friendly and attentive communication style, and in the negative sense the contentious and dominant styles. As pointed out by Bornstein (Reference Bornstein1997), the dependent pattern is characterized by a desire to seek orientation, support and protection from other people. It is easy to think that this motivation may produce interpersonal relationships characterized by friendliness and, at the same time, avoiding patterns characterized by a contentious or dominating motivation, which are very far removed from the core characteristics of this type of personality.

In a diametrically opposed position is to be found the aggressive personality pattern, which helps us to predict contentious and dominant communication styles in a positive sense and the friendly and dramatic styles in a negative sense. The aggressive pattern is characterized by a tendency towards intimidation, coercion and humiliation, with an abusive style of verbal expression (Millon, 1997). The paranoid pattern also helps us to predict 4 communication styles: the impression-leaving, attentive and precise styles in the positive sense, and the open style in the negative sense, while the borderline personality pattern contributes to the definition of the animated and open styles. The depressive, negativistic and schizotypal patterns only contribute to the definition of a single communication style each: the dominant, contentious and dramatic styles, respectively. Finally, the schizoid, antisocial and masochistic styles do not contribute in our model to the prediction of any communication style at all.

Since our data correspond to a non-clinical sample of Spanish University students, it is worth considering the role of cross-cultural differences in both communication styles and personality disorders.

Communication is one of the main dimensions usually taken into account to explain cultural differences in behavior (Smith, Reference Smith2011). There is empirical evidence that people from collectivistic cultures -as it is the case of Spain (Green, Deschamps, & Paez, Reference Green, Deschamps and Páez2005; Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2001)- are more concerned about maintaining harmonious relationships with others than people from individualistic societies, who seem to be more concerned about the clarity of their messages (Martin & Nakayama, Reference Martin and Nakayama2011; Wai Lang Yeung, & Kashima, Reference Wai Lang Yeung and Kashima2012). The direct communication style prevailing in individualistic societies tend to use verbal messages that “reveal the speaker’s true intentions, needs, wants and desires” (Martin & Nakayama, Reference Martin and Nakayama2011, p. 146), whereas collectivistic cultures tend to rely more on physical context to convey messages (non-verbal communication). Results in our sample show that, for both men and women, friendly and attentive communication styles achieve the highest scores, suggesting that Spanish students may also prefer maintaining harmonious relationships with others, in line with the Spanish traditional collectivistic orientation.

Regarding the definition of personality and personality disorders, it is important to point out that culture plays an important role but, as Alarcon notes in his revision of personality disorders and culture in DSM-IV, there is no consensus among researchers about the appropriate ways to measure the impact of culture (Alarcon, Reference Alarcon1996). Our concept of personality disorders is based on the Western notion of individual as unique and independently functioning, but what is considered a normal or abnormal personality depends on culture (Ascoli et al., Reference Ascoli, Lee, Warfa, Mairura, Persaud and Bhui2011). In our study, for example, histrionic, compulsive and narcissistic personality scales achieve the highest scores in MCMI-III, what supports the cultural component of these disorders found in previous studies (Lewis-Fernández & Kleinman, Reference Lewis-Fernández and Kleinman1994). It is also important to remember, as some authors have pointed out, that personality disorders need to be conceptualized in a continuum that ranges from normality to severe impairment, i.e., from a dimensional perspective (Widiger & Sanderson, Reference Widiger, Sanderson and Livesley1995) and taking into account the social and cultural aspects of this approach.

Considering the characteristics of our sample (Spanish university students), more research is needed aimed at studying the relationship between dysfunctional personality patterns and the psychological processes involved with them in general population, so as to be able to obtain further information on the dimensionality of the patterns concerned. It would be interesting to compare data from general population samples in different cultures with MCMI-III, and also relate this research to communication styles, in order to advance the conceptualization and measure of personality disorders, together with the understanding of their impact on interpersonal communication and relationships.

Recommendations for Higher Education Institutions

Communication is a fundamental aspect of social interaction and adjustment in all life domains and a lack of skills in this area may involve negative consequences both at personal and professional levels. In the specific context of higher education institutions, data from this study suggest the need to bear in mind the relationship between dysfunctional personality characteristics and communicative patterns when addressing competences and skills training in higher education. We think that actions aimed at promoting communication skills training and enhancing some positive styles, such as friendly or relaxed styles, might have a positive impact on students’ present adjustment and future career prospects. Also students showing diverse dysfunctional personality patterns could benefit from specific interventions addressing particular communication skills (Bergman, Westerman, & Daly, Reference Bergman, Westerman and Daly2010).