At this moment of human history, human being is both witnessing and participating in society’s scramble to cope with the effects of the COVID–19 epidemic, an event that has posed a worldwide threat to 21st-century societies’ health and well-being, which in turn has caused a rise in the incidence of health problems, including mental health problems (World Health Organization [WHO], 2021). Many of the problems facing humanity, both now and before the pandemic, are addressed in the United Nation’s 2030 Agenda (UN, 2015), which sets 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). To reach the targets included in each of the SDGs, scientists, like other social agents, are expected to do their part, each within the area of his or her discipline. Accordingly, social psychology could be reasonably expected to be doing something to address the challenge; reasonably, because psychology is essentially oriented toward achieving personal well-being. As early as 1970, in Psychology and the problems of society, the American Psychological Association (APA) declared that the discipline was supposed to study and research the problems society was grappling with at that time. This publication was preceded the year before by a landmark address by George Miller as APA president, and what he said then remains just as applicable today: “The most urgent problems of our world today are the problems we have made for ourselves; they are human problems whose solutions will require us to change our behavior and our social institution” (Miller, Reference Miller1969, p. 1063). The new and unexpected challenges we face have led to a return to a “public psychology” aligned with Miller’s premises and with the more recent citizen psychologist movement focused on “improving the lives of all” (Eaton et al., Reference Eaton, Grzanka, Schlehofer and Silka2021) to which we should add the critique of those material and social conditions of existence that hinder and endanger it (Martín-Baró, Reference Martín-Baró2016). As a science dealing directly with behavioral and social processes, psychology, Miller said, should lead the way in the search for new and better personal and social scenarios and in the achievement of goals such as well-being, health, quality of life and maximum personal and group development, in all the realms of individual and social life, for it is this engagement with well-being that makes psychology legitimate as a science and as a profession. The conception of psychology as an instrument at the service of human well-being (Miller, Reference Miller1969) and the definition of health as a state of well-being formulated in the founding act of the WHO in 1946, was later taken up by Keyes (Reference Keyes2005) to highlight the importance of circumstances and functioning within society: Sense of belonging, quality of social relations, trust in others, trust in the society in which we live, etc. As for social psychology as a specific field of work, as the review by Blanco Abarca (Reference Blanco Abarca1980) shows, its usefulness in tackling social problems is unquestionable for authors as important as Elliot Aronson, who is convinced social psychology must be socially useful and “social psychologists can play a vital role in making the world a better place in which to live” (Aronson, Reference Aronson1975, p. 13) Although the call for social relevance was the slogan of the so-called “crisis” of psychology, it is worth remembering that the assumption of scientific rationality (the capacity of the research task to respond to personal and social problems).

All sciences will say, have taken their first steps to respond to practical problems Lewin (Reference Lewin1988) so that the contrast between theory and praxis, basic and applied research, is meaningless; they are only different moments of the same process. From the historiography of psychology, it has been stated that it was the social demand, the voices coming from the environment demanding help, which returned professionals to everyday reality (Carpintero Capell, Reference Carpintero Capell2017).

A large part of the SDGs alludes to problems of models derived from interpersonal and intergroup relations (gender equality; decent work; reduced inequality, peace, justice and strong institutions), of distribution of wealth (end poverty; zero hunger) and of the abusive relationships that we have maintained with the natural environment (clean water and sanitation; affordable and clean energy; climate action; underwater life and life on land). All these problems are nothing but the result of the relationships that we have been maintaining among ourselves and with the natural environment. To reverse these relationships, it is clear that contributions from a very wide range of fields and disciplines are needed. According to the literature it seems that psychology is already doing so (Eloff, Reference Eloff2020; Jaipal, Reference Jaipal2017; Tokarz & Malinowska, Reference Tokarz and Malinowska2019), sometimes together with other disciplines (Lastretti et al., Reference Lastretti, Tomai, Visalli, Chiaramonte, Tambelli and Lauriola2021) and new areas of research are emerging focused on achieving the SDG goals as is the case of the psychology of sustainability and sustainable development, a perspective that assumes the need to develop well-being in everyday life contexts (Di Fabio, Reference Di Fabio2017, Reference Di Fabio2021; Di Fabio & Rosen, Reference Di Fabio and Rosen2018). With these considerations in mind, we have reviewed the contributions of social psychology research as expressed in scientific publications, with the ultimate goal of analyzing the possible relationship between social psychology research and the topics related to the SDGs in the 2030 Agenda (UN, 2015).

In view of how we have described the discipline’s orientation, we might hypothesize, that at least part of the published research is probably related to Sustainable Development Goals focusing on health and well-being (SDG 3). In this context, a series of questions are posed to analyze the evolution of social psychology in Spain from the standpoint of its scientific results (in terms of publications in international scientific journals) and its relationship with the Sustainable Development Goals: What is the position of social psychology within the framework of general psychology? What kind of presence does Spanish social psychology have in the world? What topics does it address most frequently? Can any particular scientific activity oriented toward the study of SDGs be identified?

To find an answer to these questions, two general objectives are proposed:

First, to assess the field of social psychology in Spain using bibliometric methods to ascertain the scientific production of the discipline, its main characteristics, its evolution and its contribution to the world as a whole and to the field of general psychology.

And them to analyze the main topics addressed by social psychology in Spain and to establish whether there is an interest in topics related to the SDGs.

Method

Source of Information

The Web of Science core collection (WoS) from Clarivate Analytics was used to analyze scientific production in the field of social psychology. All three main databases –the Science Citation Index (SCI), the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) and the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (AHCI)– were used to collect the scientific production in multi-classified Psychology, Social journals (included in different disciplines and indexes).

Data Collection and Search Strategy

Data were downloaded from the Web of Science database. The search strategy was based on the WoS subject category (the database’s thematic classification of indexed journals). All disciplines related to psychology were selected (11 WoS categories: Psychology, “Psychology, Applied”, “Psychology, Biological”, “Psychology, Clinical”, “Psychology, Developmental”, “Psychology, Educational”, “Psychology, Experimental”, “Psychology, Mathematical”, “Psychology, Multidisciplinary”, “Psychology, Psychoanalysis”, “Psychology, Social”), and a total of 1,797,533 documents were obtained. Social psychology publications from Spain were found by filtering by discipline and country using the following search strategy: WC = “Psychology, Social” AND CU = Spain.

As is usual in bibliometric studies, the analysis of the discipline is carried out through publication in journals classified in that field. This avoids the limitations that arise when analyzing organizational structures such as departments or faculties, which are difficult to compare at the national and international scope, and do not necessarily reflect the real activity in the field (there may be researchers from one department publishing in another scientific area and vice versa).

No time limits were applied; all production up to the download date was collected. Although the concept of SDGs has existed since 2015, the interest in sustainability and social issues is previous and has had different denominations, therefore, all the production has been collected without a priori temporal limitations.

Information Processing

After the publications were downloaded, a relational database was constructed with the complete information on each publication.

Development of Bibliometric Indicators

The following indicators were analyzed for the final dataset:

-

1. Research patterns.

- Yearly trend in scientific output in all psychology in the world and in Spain.

- Yearly trend of publication in social psychology in the world and in Spain. The cumulative average growth rate (CAGR) was calculated (UN-Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific [ESCAP], 2015).

- Distribution of publications by journal.

-

2. Identification of areas and research specialties.

- Co-occurrence of Web of Science categories to analyze relationships between disciplines.

- Co-occurrence of keywords to detect research specialties.

-

3. Contribution to SDGs.

Procedures for analyzing the interest that social psychology has shown in issues related to SDGs:

- OSDGFootnote 1 is an open-source tool capable of classifying text data from a variety of sources and document types, identifying SDG-relevant texts and assigning them to one or more specific SDGs based on content analysis (Pukelis et al., Reference Pukelis, Bautista-Puig, Skrynik and Stanciauskas2020).

- The title and abstract of all publications were reviewed manually to label the papers according to their relationship with the SDGs. The same procedure was used to classify the papers by type (empirical, theoretical, or interventionist).

-

4. Visualization of the results.

The information obtained is presented in tables and graphs. For visualization, tools such as Vosviewer were used to create thematic clusters. Alluvial flow diagrams were also made with the Raw programFootnote 2.

The Figure 1 summarizes the procedure followed.

Figure 1. Procedure followed in the analysis

Results

Research Patterns in Psychology Publications

The publications in the “Psychology” area of Web of Science were examined, and 1,797,533 documents were identified. The earliest publications in WoS dated back to 1900, though it was not until the mid-1950s that production figures became significant. Growth accelerated in 2000; half of the documents published on psychology appeared in or after the year 2000. The main country responsible for publications is the USA, with 45 % of the psychology documents, followed by England, Canada, Germany and Australia with proportions ranging between 4% and 8%. Spain occupies the eighth position with 1.7% of publications the world over. The leading disciplines in production are “Psychology Multidisciplinary” (with 25% of the publications), “Psychology, General” (with 24%), and “Psychology, Clinical” (17%). “Psychology, Social” accounts for 8% of the “Psychology” publications (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Characteristics of Scientific Publications on Psychology (Web of Science 1900-2020)

Research Patterns in Spanish Social Psychology Publications

Analysis of the social psychology production shows that 1,632 publications signed by at least one Spanish institution have been identified. The earliest publications indexed in WoS date from the 1980s. Production growth has been steady, with a cumulative average growth rate (CAGR) of 8.61%. Here, too, half of the documents date from 2000 or later coinciding with the emergence of the Millennium Development Goals. The latest increase in production is from 2016, with the implementation of the SDGs. The USA is the leading producer, and Spain holds a ninth place with 1.2% of world production. Figure 3 shows the annual development of world production (blue line) and Spanish production (yellow line) in Psychology Social. The data show that Spain’s contribution has gone from representing 0.05% of world publications in 1980 to 0.12% in 2019 (light blue columns). In terms of Spanish production of social psychology has grown more than the world (CRAG = 11.12%).

Figure 3. Characteristics of Scientific Publications on Social Psychology (Web of Science 1980-2020)

Spanish institutions, primarily public universities, participated in 1632 documents. The Autonomous University of Madrid heads the list, with 12 %, followed by the University of Granada and the University of Valencia. Table 1 lists the institutions that participated in more than 20 documents (Table 1).

Table 1. Spanish Institutions with Social Psychology Publications (> 20 Documents)

Considering journals of publications, there is a high concentration of articles on social psychology signed by Spanish institutions around a few journals. Thus, the core is made up of two titles (marked in bold font in Table 2) which represent only 2,7%. Among the core journals, Personality and Individual Differences contains almost a quarter of the production, followed by the International Journal of Social Psychology/Revista de Psicología Social with 14%. Table 2 lists the journals that have published more than 10 papers with their frequency and classification in WoS categories. All are assigned to the category “Psychology, Social” and included in Social Science Citation Index.

Table 2. Most Productive Journals in Social Psychology from Spanish Institutions (Web of Science 1980-2020) ( > 10 Documents)

Note. Publications that form the “core” are marked in bold font.

Thematic Content of Spanish Social Psychology Publications

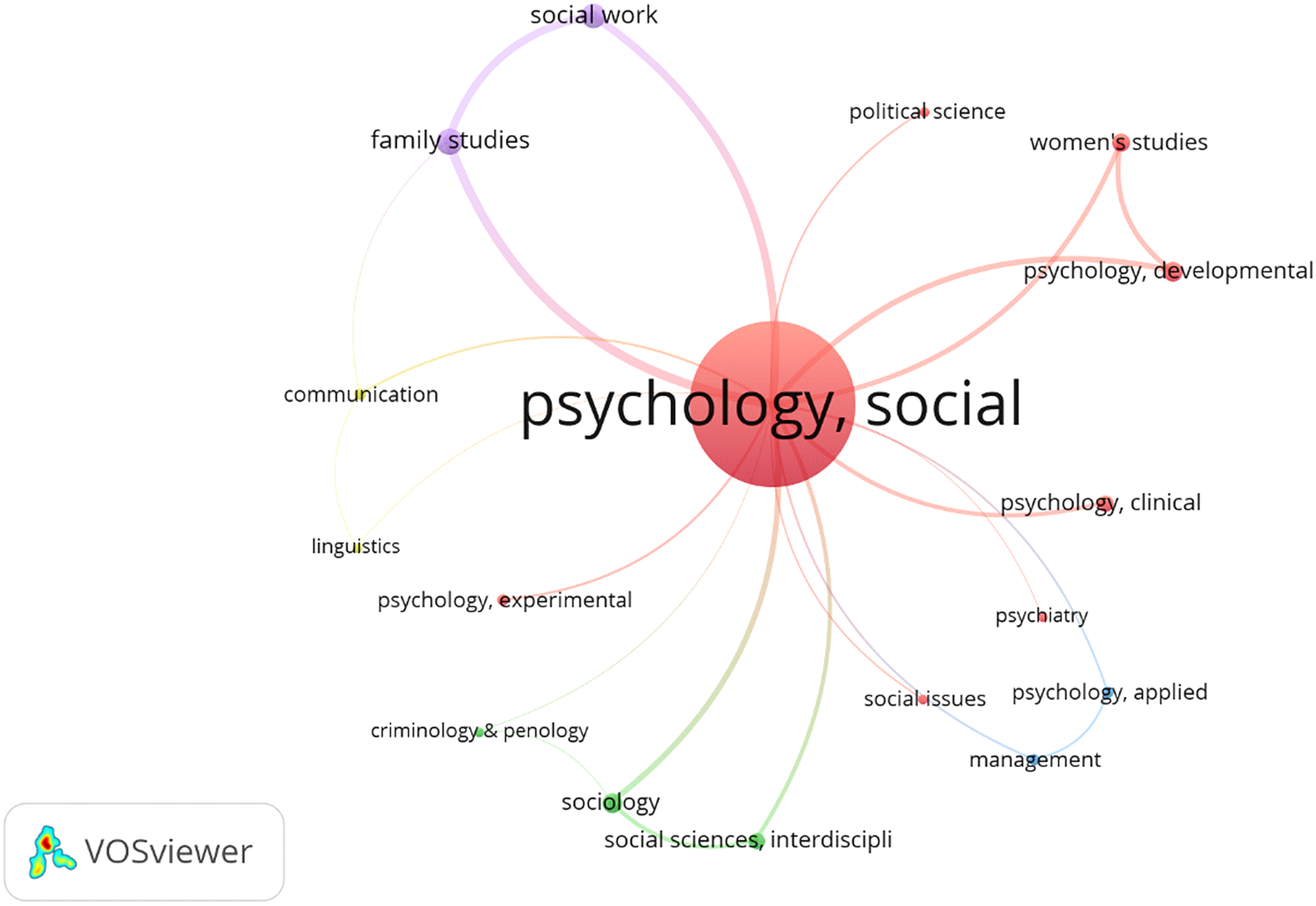

For a deeper analysis of publication content, the first step was to identify journal affiliation. While all the publications were classified in the WoS category of “Social Psychology”, because of multi-class classification, additional areas can be identified to which the documents also pertain. Figure 4 presents a thematic network showing social psychology’s relationships with other disciplines that are also addressed in the journals at issue. Node size indicates the volume of documents assigned to each theme. The variety of disciplines in the network attests to the wide thematic spectrum that social psychology covers (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Disciplinary Relationship through Thematic Classification of Social Psychology Journals (WoS 1980-2020)

Keywords are another important content-related aspect. Keyword analysis was used to identify primary research topics.Figure 5 shows a cluster analysis based on keyword co-occurrence (frequency > 10 keywords) to detect the main thematic clusters (each identified with a color). These clusters include “attitudes”, “persuasion”, “individual differences”, “personality”, “women and gender”, “health” and “adolescents”. The relationships between terms can also be observed by the edges. Node size is proportional to the number of documents associated with each keyword.

Figure 5. Cluster Analysis through Co-Occurrence of Keywords in Spanish Social Psychology Publications (WoS 1980-2020) (> 10 Co-Occurrence of Keywords)

Attitudes, considered the predecessor and predictor of social conduct, have been a mainstay among social psychology research topics from the discipline’s start. It makes sense for attitudes and other related topics to occupy an important space (red color) on the thematic cluster map in Figure 5. By the size of its node, attitudes can be readily seen to be one of the topics with the most associated documents; there are also documents addressing the study of concepts closely related to attitudes, such as beliefs, emotions, values, ideology, and behaviors possibly related with certain attitudes, e.g., terrorism. The “attitudes” thematic cluster also contains attitudes and relationships between social groups, outgroups and associated processes, such as stereotypes, prejudices and discrimination behavior, group inclusion, group integration, group conflict, and social identity. Some documents in the cluster refer to attitudes toward specific groups (e.g., immigrants). Documents referring to research into the self also figure prominently in the “attitudes” cluster, since the self is an important research topic in social psychology.

The “attitudes” node is related to nodes of documents concerning the processes involved in the change of attitude or persuasion (blue cluster); these nodes contain documents related to the sort of information available, attitude characteristics such as accessibility, confidence, and uncertainty.

The “attitudes” cluster’s edges are related to the “women and gender” cluster (orange color). This cluster identifies documents about the various kinds of sexist attitudes (benevolent sexism, ambivalent sexism, hostile sexism).

The thematic cluster dealing with personality (yellow color) is another of the major thematic blocks making up the map. The “personality” node documents include three groups: documents referring to personality variables (extraversion, impulsivity, sensation seeking, etc.), documents referring to personality measurement scales (e.g., the big five scale) and studies designing, validating and analyzing the psychometric properties of personality scales and/or adapting scales to measure personality variables in the Spanish context.

The thematic cluster of health and wellness/well-being publications (purple color) is another major research area in social psychology. It includes documents bearing a significant relationship with health issues like stress, depression, self-esteem, and social support.

Lastly, adolescents and their behavior (green cluster) have received and still receive a great deal of attention from studies published in social psychology journals. In the “adolescents” cluster we see document clusters referring to adjustment or social adaptation, risky behavior, aggressive behavior, mental health and violence, along with clusters referring to abuse, maltreatment, exposure to violence (domestic or institutional), victimization, cyberbullying, relationships with parents, and so on.

Contribution to SDGs

The 1,632 documents were subjected to content review for a more in-depth analysis of social psychology’s contribution to the SDGs. The first step was to apply the OSDG tool, which associated the highest percentage of documents with SDG 3 (good health and well-being). The results were validated through in-depth content analysis. The results in Table 3 show the number of documents related to each SDG and the percentage that this contribution represents over the total of 1,632 documents. SDG 3 and SDG 5 are the goals with the largest numbers of documents.

Table 3. Assignment of Social Psychology Publications to SDGs

Note. Since a single document may deal with multiple topics, there are cases of publications assigned to more than one SDG (therefore the sum of documents is greater than 1,632).

After the publications were assigned to the SDGs, the targets associated with each SDG were identified with a view to establishing more-precise relationships between document content and SDGs.

In accordance with the hypothesis, the documents associated with SDG 3 generally describe studies oriented toward analyzing variables and processes affecting health (physical or mental) and psychological well-being. One of the targets set in SDG 3 is to prevent, provide treatment for and promote mental health and well-beingFootnote 3. The documents report diverse factors that can affect the achievement of this target. One such factor is harmful social relationships. Harmful social relationships, whether in the family, at work, or in other social spheres, including mistreatment, abuse (be it physical, psychological, or sexual) and abandonment, have a negative effect on the physical and mental health of those caught up in them. The bibliography we analyzed also shows that children and adolescents are especially vulnerable in harmful social relationships, making it difficult to reach the SDG 3 target of caring for and protecting children. In this sense, the documents we reviewed make it clear that victimization or poly-victimization (sexual, cyberbullying, etc.) impairs the mental health (depression, anxiety) of adolescents interned in centers, as mentioned, for example, by Segura et al. (Reference Segura, Pereda, Guilera and Abad2016); sexual abuse and sexual victimization particularly generate emotional disorders and anxiety in women (Cantón-Cortes et al., Reference Cantón-Cortes, Cantón and Cortes2016) and adolescents (Pérez-González et al., Reference Pérez-González, Guilera, Pereda and Jarne2017). Adolescents’ mental health is also impaired by emotional abuse from parents within the family and from peers (Calvete, Reference Calvete2014). In general, parenting style and peer attachment predict emotional instability in late childhood and early adolescence (Llorca-Mestre et al., Reference Llorca-Mestre, Samper-García, Malonda-Vidal and Cortés-Tomas2017). Diverse studies show that the various kinds of abuse and abandonment are associated with poly-drug use in adolescents (Álvarez-Alonso et al., Reference Álvarez-Alonso, Jurado-Barba, Martínez-Martín, Espín-Jaime, Bolaños-Porrero, Ordóñez-Franco, Rodríguez-López, Lora-Pablos, de la Cruz-Bértolo, Jiménez-Arriero, Manzanares and Rubio2016). Other papers trace a relationship between child abuse and depressive disorders and attention problems in children (Bertó et al., Reference Bertó, Ferrin, Barberá, Livianos, Rojo and García-Blanco2017).

Furthermore, another subgroup of documents reveals that certain personality variables (neuroticism, introversion, etc.) and coping styles bear a negative association with mental health (Etkin et al., Reference Etkin, Mezquita, López-Fernández, Ortet and Ibáñez2020; Moret-Tatay et al., Reference Moret-Tatay, Beneyto-Arrojo, Cabrera Labore-Bois, Martínez-Rubio and Senent-Capuz2016), alcohol consumption (Aluja et al., Reference Aluja, Lucas, Blanch and Blanco2019; Ibáñez et al., Reference Ibáñez, Moya, Villa, Mezquita, Ruipérez and Ortet2010) or physical health, as in the case of type-A personalities and high blood pressure (Sanz et al., Reference Sanz, García-Vera, Magán, Espinosa and Fortún2007).

Other studies provide evidence that the family environment can be a protective factor in mental health. A positive relationship exists between well-being and family identity or a positive feeling of belonging (Herrera et al., Reference Herrera, Sani and Bowe2011), and between well-being at work and at home (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Lee, Kossek and Las Heras2012). In addition, well-being is associated with competence to manage emotions or emotional intelligence in different environments of daily life (Extremera & Rey, Reference Extremera and Rey2016). For example, dissatisfaction in the work environment generates emotional distress (depression, anxiety, stress) and even serious mental health problems (Extremera et al., Reference Extremera, Mérida-López, Quintana-Orts and Rey2020), while leadership capability is associated with well-being in the work environment (Espinoza-Parra et al., Reference Espinoza-Parra, Molero and Fuster-Ruizdeapodaca2015). In social relations, the feeling of cultural integration is associated positively with well-being (Ferrari et al., Reference Ferrari, Manzi, Benet-Martinez and Rosnati2019). Some of the papers analyzed also mention that personal well-being is associated with, among many other factors, volunteering (Vecina & Chacón, Reference Vecina and Chacón2013) and a positive body self-image (Moreno-Domínguez et al., Reference Moreno-Domínguez, Servián-Franco, Reyes del Paso and Cepeda-Benito2019).

Other SDG 3 targets that some of the reviewed research documents are associated with have to do with preventing and treating the use of addictive substances like drugs, alcohol, and tobacco. The publications show that gender roles number among the psychosocial factors associated with drug and alcohol consumption: Role acceptance favors alcohol consumption in the case of the masculine role and provides protection from alcohol consumption in the case of feminine roles (Zimmermann et al., Reference Zimmermann, Sieverding and Müller2010). Tobacco consumption, a behavior that affects health negatively the world over, is associated with emotional processes, personality variables (Fernández Del Río et al., Reference Fernández Del Río, López-Durán, Rodríguez-Cano, Martínez, Martínez-Vispo and Becoña2015), thrill seeking (Fernández-Artamendi et al., Reference Fernández-Artamendi, Martínez-Loredo, Fernández-Hermida and Carballo-Crespo2016) and anxiety (Becoña et al., Reference Becoña, Vázquez and Míguez2002) among other factors.

In the social psychology publications analyzed, the contents related to SDG 5 hold second place in terms of document volume. The targets set in the 2030 Agenda for SDG 5 aim at ending discrimination against women and girls worldwide and eliminating all forms of violence against women in the public and private spheresFootnote 4. Some of the documents show that the sexual roles society assigns to women number among the factors that form a barrier to achieving this target and that women’s adoption of such roles places constraints on their life and their personal and career development.

These learned sexual roles are expressed in different spheres. In the case of the career sphere, they may lead to greater accommodation and less competitiveness in women, which does not help reduce inequalities (Elgoibar et al., Reference Elgoibar, Munduate, Medina and Euwema2014). Some of the studies alert that political leaders, the media, and educators, among others, should be aware of how women’s conformity with traditional gender stereotypes can also lead women to negative consequences similar to other hostile forms of stranger harassment (Moya-Garófano et al., Reference Moya-Garófano, Moya, Megías and Rodríguez-Bailón2020). The roles women accept can affect how women manage emotions such as guilt in conflict situations. Some publications show that women with high dependency feel guiltier than women with low dependency in high-conflict situations (Valor-Segura et al., Reference Valor-Segura, Expósito, Moya and López2014).

Some documents (Ferrer-Pérez & Bosch-Fiol, Reference Ferrer-Pérez and Bosch-Fiol2014) provide an overview of acceptability and public attitudes that support the use of gender violence and focus on the effect of gender and gender role attitudes. The data review shows that Spanish society as a whole considers intimate partner violence against women as a social problem and rejects it, but there are still some violence-supportive attitudes, such as victim blaming, and there is a gender gap in the consideration of gender violence as well.

Some of the publications (Montañés et al., Reference Montañés, de Lemus, Bohner, Megías, Moya and García-Retamero2012) address how the intergenerational transmission of benevolent sexist beliefs from mothers to adolescent daughters negatively influences daughters’ traditional goals, academic goals (i.e., getting an academic degree) and academic performance, perpetuating gender inequalities. Psychosocial research also confirms the presence of sexist attitudes in society that can be used to legitimize and maintain gender violence and foster a climate of social permissiveness towards sexual violence against women (Durán & Rodríguez-Domínguez, Reference Durán and Rodríguez-Domínguez2020). Lastly, gender stereotypes are found to persist in the educational sphere, as some documents show with respect to physical education (Del Castillo et al., Reference Del Castillo-Andrés, Romero Granados, González-Ramírez and Campos Mesa2012) and physical education textbooks (Táboas-Pais & Rey-Cao, Reference Táboas-Pais and Rey-Cao2012) where there is a noticeable imbalance between male and female representation in which the male model is clearly predominant. In addition, textbook images portray males and females in stereotypical roles and depict certain activities or sports as more appropriate for one gender or the other.

Some of the research reports how the presence of gender stereotypes in daily life impedes the achievement of SDG 5’s targets because they constrain the role women play in society. Spanish national online newspapers maintain the underrepresentation, stereotyping and discrimination of women in web news, thereby reinforcing gender inequality (Mateos de Cabo et al., Reference Mateos de Cabo, Gimeno, Martínez and López2014). In a review of Spanish newspaper articles and advertisements (Matud et al., Reference Matud, Rodríguez and Espinosa2011), men were found to be more commonly featured in articles, photographs, and advertisements than women and much more frequently depicted as soldiers, athletes, or high-ranking businesspersons than women. Furthermore, the reporters writing the articles were more likely to be men than women. In addition, men were more likely to be cited as sources than women. The equivalent is found to happen in radio advertisements (Rodero et al., Reference Rodero, Larrea and Vázquez2013): There is a strong tendency to employ male voices more often than female voices in the belief that male voices sound more convincing. Accordingly, the supremacy of the male voice over the female voice in radio advertising and the repeated association between voices and product types is more based on tradition than on the real effectiveness of the advertisements.

Discussion

The bibliometric study shows that social psychology as a discipline has made important strides in terms of publications; publication numbers rose considerably starting in 2000. This increase in international publication speaks as to the activity patterns of Spanish scientists, who have accepted publication in indexed journals as one of the main channels for disseminating research results, as per the guidelines set by research, development and innovation evaluation authorities.

In the field of psychology, Spain holds eighth place in the world in terms of Web of Science publication numbers. This is a better position than anticipated since the country is tenth in overall WoS production in all disciplinesFootnote 5. Social psychology accounts for 8 % of all Spanish production in psychology, and universities (particularly the Autonomous University of Madrid) are the main producers. Document cluster analysis shows that there are five main thematic groups: attitudes, persuasion, personality variables, women and gender and adolescents.

A second analysis shows that, in accordance with our hypothesis, the research topics social psychology deals with are primarily related to SDG 3 (good health and well-being). A smaller number of documents is associated with SDG 5 (gender equality). Regarding the contributions to achieving the SDGs, which is the focus of this paper, it should be said that in relation to SDG3 the research conducted shows several factors that can negatively affect the achievement of the goals associated with this target. Thus, achieving this objective requires preventing harmful social relationships, such as mistreatment, abuse (physical, psychological or sexual), or neglect, as they have a negative effect on physical and mental health, with children and adolescents being particularly vulnerable. In contrast, healthy family environments can be a protective factor for health and well-being. The reported research further shows that well-being is associated with competence in managing emotions in different environments. Finally, a feeling of cultural integration is positively associated with well-being. In relation to SDG 5, research in social psychology shows that the stereotypes and sex roles that society assigns to women, which in many cases are assumed by women, limit women’s personal and professional lives. Ending discrimination against women and eliminating all forms of violence against women in the public and private spheres requires eliminating the stereotypes and sex roles that society assigns to women and that act as barriers to achieving the targets associated with SDG 5. Data show that gender remains a vulnerability factor that negatively affects women’s health and well-being. Striving for equity is a challenge for societies pursuing a better level of health and well-being, emotionally, psychologically and socially. The conclusion drawn from our review is that, through its prolific research, social psychology has contributed to improving knowledge about the cognitive, emotional, and contextual processes that may influence the types of social behavior that should be ensured or modified if we are to achieve the targets set out in SDG 3 and SDG 5.

For decades social psychology has been criticized for making only puny contributions to solving real social problems. However, we believe that it should be positively valued that 34% of the articles on social psychology signed by Spanish institutions in WoS make contributions on how to improve well-being and health (SDG 3) or gender equality (SDG 5). In this line, if similar figures were achieved in all disciplines, there would undoubtedly be a significant improvement in the achievement of the SDGs.

At all events, social psychology can improve its contributions and the Agenda 2030 offers a framework of action in which the discipline is still in time to apply its hard-won decades of knowledge to the problems the Agenda showcases and to help face the social challenges of now and the future (UN, 2015). While continuing to strive to push research publications into ever-better positions in terms of bibliometric impact, researchers, as social psychologists, ought to take advantage of the opportunity to pit their skills against the social challenges and problems yet to be resolved, and in this endeavor, they should apply the knowledge, methods, and tools that social psychology has created.

There are some limitations to the present study that had to be considered. If we understand social psychology as a way to look at the behavior of people (the Galilean perspective of the Lewinian’s school, for instance), and not as an independent field of contents, it becomes quite difficult to clearly identify the publications of social psychology in Spain and elsewhere. The “knowledge areas” in the Spanish legislation resemble much more an organizational and administrative structure than an academic or scientific one. For more than 4 decades bibliometrics has been consolidated as one of the main tools to analyze and evaluate scientific activity through its research results so that the study of scientific publications in high impact journals can offer a very realistic view of the dynamics of a scientific field. Likewise, the identification of an area through the thematic classification of journals makes it possible to collect all those documents published, beyond the institutional origin or the organizational structure to which the authors respond. On the other hand, although the analysis of scientific production published in international journals makes visible an important part of the research results (those belonging to the scientific mainstream), it leaves aside other documents that may be equally significant within the discipline. Identifying and recovering these documents is a challenge and could be the objective of future research. Finally, the conclusions of this research offer a partial (some topics may be overrepresented whereas others are underestimated) but a real view on how Social Psychology can contribute to achieving some SDGs. These conclusions are likely to be different if Scopus had been used as the chosen database, but also Scopus would also offer a partial, although real view. Conducting another study using another database would be useful to deepen and compare the conclusions which were drawn from WoS regarding the contribution of Social Psychology to the SDGs.