Rumination is a psychological construct that has often been addressed in recent decades because it is a maladaptive emotion regulation strategy. It is understood as a style of thinking characterized by recurring, intrusive, negative ideas (Denson, Reference Denson, Forgas, Baumeister and Tice2009) that tend to stay in mind for several minutes, hours, or even days or longer. The concept was originally associated with the study of sadness and depression, where it was demonstrated that people who react in a ruminative way, thinking about their symptoms or the possible causes and consequences of those symptoms, suffer the effects of depressed mood longer and more intensely (Nolen-Hoeksema, Reference Nolen-Hoeksema1991). Later it was found that rumination as a thinking style is accompanied by other negative emotions, and is related to anxiety disorders (Nolen-Hoeksema, Reference Nolen-Hoeksema2000), pessimistic thoughts (Lyubomirsky & Nolen-Hoeksema, Reference Lyubomirsky and Nolen-Hoeksema1995), impaired concentration (Lyubomirsky, Kasri, & Zehm, Reference Lyubomirsky, Kasri and Zehm2003), anger (Rusting & Nolen-Hoeksema, Reference Rusting and Nolen-Hoeksema1998), hostility (Anestis, Anestis, Selby, & Joiner, Reference Anestis, Anestis, Selby and Joiner2009), and aggression (Bushman, Reference Bushman2002; Bushman, Bonacci, Pedersen, Vasquez, & Miller, Reference Bushman, Bonacci, Pedersen, Vasquez and Miller2005; Konecni, Reference Konecni1974).

Anger rumination refers to recurring, involuntary thoughts that occur while experiencing that emotion and continue even after the anger-provoking episode is over (Sukhodolsky et al., Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001). Rumination about anger episodes can make the anger experience longer and more intense, and can worsen its likely negative consequences (Rusting & Nolen-Hoekseman, Reference Rusting and Nolen-Hoeksema1998). One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that rumination maintains and increases anger, and creates a prolonged state of readiness that makes the person more likely to subsequently act aggressively.

Maxwell’s (Reference Maxwell2004) study found that men tend to behave more aggressively than women, and that anger rumination was an important predictor of aggression. The study also reported the psychometric properties of the Anger Rumination Scale (ARS) created by Sukhodolsky and collaborators (Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001). The scale is a reliable, valid measure of this aggression-associated construct.

The ARS (Sukhodolsky et al., Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001) is an inventory that measures the tendency to focus attention on current and past thoughts associated with anger episodes. The authors (Sukhodolsky et al., Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001) found four factors: 1) angry afterthoughts (i.e., ideas that reiterate recent anger episodes), 2) thoughts of revenge (i.e., ideas about retaliation), 3) angry memories (i.e., remembering past anger), and 4) understanding of causes (i.e., thinking about the causes of past anger experiences). Several researchers have studied the instrument’s psychometric properties to test the items’ consistency over time and the instrument’s factor structure; results have been satisfactory. The list of validity studies includes research in Great Britain and China (Maxwell, Sukhodolsky, Chow, & Wong, Reference Maxwell, Sukhodolsky, Chow and Wong2005), France (Reynes, Berthouze-Aranda, Guillet-Descas, Chabaud, & Deflandre, Reference Reynes, Berthouze-Aranda, Guillet-Descas, Chabaud and Deflandre2013) and Iran (Besharat, Reference Besharat2011).

The results of ARS validation using the STAXI (State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory; Spielberger, Reference Spielberger1988) indicated ARS scores were moderately, significantly correlated with STAXI subscales: trait anger, state anger, anger expression, and anger control. A strong correlation between the ARS and negative affectivity was also found (Sukhodolsky et al., Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001).

Considering the ARS for application in a Mexican population would facilitate timely detection of the cognitive processes involved in anger expression and persistence. With that in mind, the present study’s objective was to assess the validity of the ARS, by Sukhodolsky his collaborators (Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001), in Mexico. Specifically, we examined its construct validity by determining if the four factors measured by the ARS adequately measure anger rumination in Mexico. We also assessed convergent validity by evaluating the correlation between the ARS and other instruments that measure anger, aggression, and emotion regulation. Since research has shown an association between the ARS and other measures, like anger and aggression (Anestis et al., Reference Anestis, Anestis, Selby and Joiner2009; Maxwell, Sukhodolsky, & Sit, Reference Maxwell, Sukhodolsky and Sit2009; Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Denson, Goss, Vasquez, Kelley and Miller2011; Sukhodolsky et al., Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001), we hypothesize that the present study will replicate that finding of association. In principle, rumination entails maintaining and increasing anger, which makes aggressive behavior more likely. As a result, we expect that in a Mexican sample, the ARS will correlate moderately with measures of anger expression and control, as well as physical aggression (Hypothesis 1).

In terms of anger – control and expression – a meta-analysis indicated that the two sexes are more alike than different (Archer, Reference Archer2004). Some studies (Besharat, Reference Besharat2011; Maxwell et al., Reference Maxwell, Sukhodolsky and Sit2009) indicate that men score higher on rumination than women, but another study did not replicate that finding (White & Turner, Reference White and Turner2014). We expected that in a Mexican sample, men would score higher on rumination than women (Hypothesis 2) due to the strong, aggressive gender role associated with men. Regarding age, as in earlier studies, we expected this would not relate to ARS outcomes (Hypothesis 3).

Method

Participants

Two samples participated in this study. To create the first, 700 participants were contacted using a non-random method called snowball sampling. Psychology students at Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo (located in Mexico) were trained to administer the instrument. Each student administered it to five people, in the following age ranges: 20–27; 28–35; 36–43; 44–51; and 52–60. The students were assigned to contact 50% men and 50% women, a condition they met, in those five age ranges.

Their average age was 38.6 years (SD = 12.42). Their level of education was distributed as follows: 40.8% had received higher education; 20.4% preparatory – or late high school; 18% secondary school; 10.7% elementary school. Participation was voluntary and anonymous for all involved.

The second sample was taken from the general population of Mexico City. This sample was deployed to evaluate convergent validity between the ARS and the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire by Gross and John (Reference Gross and John2003). Non-probability accidental sampling was used. Two-hundred people participated, 104 men and 96 women with an average age of 27.65 (SD = 11.43) and ranging in age from 18 to 72 years old. 75.5% were single, and 24.5% married. Their highest level of education was diverse: one had only elementary school, five secondary school, 30 preparatory, 123 had attended college, and 21 had post-graduate studies.

Instruments

Anger Rumination Scale (ARS; Sukhodolsky et al., Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001)

This scale measures the tendency to focus attention on thoughts and memories of anger experiences, current and past. It is comprised of four subscales: Angry Afterthoughts (6 items, α = .86, e.g., “After an argument is over, I keep fighting with this person in my imagination”), Thoughts of Revenge (4 items, α = .72, e.g., “When someone makes me angry I can’t stop thinking about how to get back at them”), Angry Memories (5 items, α = .85, e.g., “I feel angry about certain things in my life”) and Understanding of Causes (4 items, α = .77, e.g., “I think about the reasons people treat me badly”). Response options range from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always).

Aggression Questionnaire (AQ; Buss & Perry, Reference Buss and Perry1992)

This instrument evaluates components of aggression in the general population. The original scale has four factors (Buss & Perry, Reference Buss and Perry1992) that are valid and reliable in Mexico (Pérez, Ortega, Rincón, García, & Romero, Reference Pérez, Ortega, Rincón, García and Romero2013). Those factors are: Physical Aggression (8 items, α = .85, e.g., If somebody hits me, I hit back), Verbal Aggression (4 items, α = .67, e.g., I often find myself disagreeing with people), Anger (6 items, α = .68, e.g., I have trouble controlling my temper), and Hostility (9 items, α = .77, e.g., When people are especially nice, I wonder what they want). Response options range from 1 (extremely uncharacteristic of me) to 5 (extremely characteristic of me).

State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory in Spanish (STAXI-2; Miguel-Tobal, Casado, Cano-Vindel, & Spielberger, Reference Miguel-Tobal, Cano-Vindel, Casado and Spielberger2001)

This inventory measures the emotional and expressive aspects of anger. The Mexican validation of it (Oliva, Hernández, & Calleja, Reference Oliva, Hernández and Calleja2010) has the following scales: State Anger (15 items, α = .88, e.g., “I am furious”), Trait Anger (10 items, α = .86, e.g., “I am quick tempered”), Anger Expression (12 items, α = .67–.68, e.g., “I argue with others”) and Anger Control (12 items, α = .80–.84, e.g., “I try to relax”). Response options range from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always).

Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, Reference Gross and John2003)

This measures two dimensions: Reappraisal, with six items (e.g., “I change my emotions by changing the way I think about the situation I’m in”) and Suppression, with four (e.g., “When I am feeling negative emotions, I make sure not to express them”). Response options range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The scale has factorial validity in several countries, including Mexico (Matsumoto, Yoo, & Nakagawa, Reference Matsumoto, Yoo and Nakagawa2008). Its reliability in Mexico was reported to be .77 for Reappraisal, and .76 for Suppression (Acosta Canales & Domínguez Espinosa, Reference Acosta Canales and Domínguez Espinosa2014).

Procedure

The ARS was adapted from English into Spanish through translation and back-translation. Five bilingual specialists from Mexico participated, English-language teachers who lived for some time in the United States and hold certificates in English from Trinity College London. Only slight linguistic differences occurred, which were judged by psychology experts at Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo. They proposed solutions to adhere to terminology particular to the Mexican population. The resulting version in Spanish was administered to 40 people with the same characteristics as the sample in which it would be validated, and open-ended interviews were conducted to confirm items were correctly interpreted. We found that participants understood the scale (Appendix).

Data analysis included Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), because it is a suitable way to see if the constructs of an existing instrument (Sukhodolsky et al., Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001) apply (i.e., display goodness of fit) in a different sample (Mexico). CFA can also produce statistics associated with poor goodness of fit, which help improve goodness of fit in later analyses (Byrne, Reference Byrne2006). Next, nested models were compared (four-factor versus three- and two-) to examine the strength of results in greater depth (Brown, Reference Brown2006; Mueller & Hancock, Reference Mueller, Hancock and Osborne2008). Afterward, Pearson correlations were used to explore the convergent validity of ARS subscales. Last, we compared average scores in men and women on said subscales.

Results

First we used CFA to assess whether the four constructs measured by the ARS applied in the Mexican sample. Robust methods of maximum likelihood estimation were utilized, in the program EQS 6.1 (Bentler, Reference Bentler1995), because normalized estimation of multivariate kurtosis was 50.68, indicating the data were non-normally distributed.

The CFA model’s goodness of fit was evaluated according to the following criteria: 1) the Satorra-Bentler chi-square statistic – where a non-significant chi-square indicates good fit, but this statistic is highly sensitive to sample size, so a model with goodness of fit can still yield a significant chi-square; 2) comparative fit index (CFI) and robust comparative fit index (RCFI), for which values over .95 are considered good (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999); 3) standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), for which values under .08 are considered good (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1998); and 4) root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), where values under .08 are acceptable (Browne & Cudeck, Reference Brown, Cudeck, Bollen and Long1993).

We found that Sukhodolsky et al.’s (Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001) original four-factor model (Model A, Table 1) yielded a significant chi-square, χ2 = 880.84, df = 146, p = .001, Satorra-Bentler χ2 = 650.04, df = 146, p = .001, which is not unusual for a large sample. Results based on the other three criteria were mixed. It had an RCFI = .911, which is marginally good (below the desired .95), SRMR = .059 indicating good data fit, and RMSEA = .070 which is good. This suggests a certain goodness of fit even though the model fell short of the higher standards desired.

Table 1. Goodness of Fit Indices of Four-factor Versus Competing Models

Note: Model A = Sukhodolsky et al.’s (Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001) original four factors: angry afterthoughts (AA), thoughts of revenge (TR), angry memories (AM), and understanding of causes (UC). Model B = Sukhodolsky et al.’s four factors with correlated error terms from items 1 and 2. Model C = Three factors: 1) AM, 2) AA, and 3) TR + UC. Model D = Two factors: 1) TR + UC and 2) AM + AA. Model E = Two factors: 1) TR and 2) UC + AA + AM.

* p < .001.

Given the model’s modest goodness of fit, we wondered if it could be improved by examining modification indices (i.e., the Lagrange multipliers test). If a model improves the level of compliance with goodness of fit criteria, it can be preliminarily considered valid. On the contrary, if it lacks goodness of fit, then other models should be explored to achieve better goodness of fit to the data collected (comparison of competing models; Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, Reference Hair, Anderson, Tathan and Black1999).

A second CFA was carried out using the Lagrange multipliers test. The outcome was that the model improved significantly upon correlating the error terms in items 1 (“I ruminate about my past anger experiences”) and 2 (“I ponder about the injustices that have been done to me”). Those two items have similar content in that anger is often associated with perceived injustice. They also belong to the same factor (angry memories). Thus, we resolved to correlate the two items’ error and run the analysis again.

The result was a four-factor model that included correlated error from items 1 and 2 (Model B, Table 1). This improved goodness of fit, but not enough to fulfill the desired standards. The chi-squares were significant (Table 1), CFI = .888, robust CFI = .921, SRMR = .056, and RMSEA = .066.

Since Models A and B did not reach desired goodness of fit levels, we considered the possibility that the original ARS’s four factors are inadequate to measure rumination in the present study’s sample. Perhaps a more parsimonious model (with fewer factors) would be more suitable and therefore boost goodness of fit. Thus, we deployed the strategy Jöreskog refers to as “model generating” (Jöreskog, Reference Jöreskog, Bollen and Long1993, p. 295), which consists of modifying the original model, then evaluating it with the same data to increase goodness of fit.

From here on, we will refer to Sukhodolsky et al.’s (Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001) four-factor model (angry afterthoughts, thoughts of revenge, angry memories, understanding of causes) with correlated error in items 1 and 2 as Model B. We proposed three competing models with fewer factors. The objective was to improve goodness of fit and in turn, better capture rumination. The same four factors were used to construct competing models.

Model C was comprised of three factors: 1) Angry afterthoughts, 2) Angry memories, and 3) Thoughts of revenge + Understanding of causes. The third factor was based on the premise that thoughts of revenge and understanding the causes of anger fall into the same dimension: thinking about what you could have done better at the time of anger but did not do (e.g., hitting; Sukhodolsky et al., Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001, p. 696).

Model D was made up of two factors: 1) Thoughts of revenge + Understanding the causes of anger, and 2) Anger memories + Angry afterthoughts. Factor 1 represents the dimension of what would have happened ideally (i.e., counterfactual thinking; Sukhodolsky et al., Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001, p. 696) while factor 2 is the temporal dimension (duration) of rumination (Sukhodolsky et al., Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001).

Model E had two factors: 1) Thoughts of revenge, and 2) Understanding the causes of anger + Angry afterthoughts + Angry memories. We proposed this model because, based on the items’ content, revenge is the behavioral dimension of rumination, whereas the other components (causes, afterthoughts, and memories) make up the more cognitive dimension.

The competing models’ goodness of fit statistics appear in Table 1. Results indicate the competing models had lower goodness of fit than the four-factor model (Model B). The next step was to evaluate whether the difference between models was significant, so we looked at scaled chi-square difference (Crawford & Henry, Reference Crawford and Henry2003; Satorra & Bentler, Reference Satorra and Bentler2001). The four-factor Model B had effectively better goodness of fit than the three competing models with fewer factors. Especially based on scaled chi-square difference results, Model B fared better than Model C, Satorra-Bentler χ2 diff = 201.96, df = 4, p < .001, Model D, Satorra-Bentler χ2 diff = 229.57, df = 6, p < .001, and Model E, Satorra-Bentler χ2 diff = 165.78, df = 6, p < .001. Of the four models, the one made up of four factors and correlated error terms from items 1 and 2 (Model B) is the best choice to conceptually explain the construct of rumination in the Mexican sample. This conclusion was reinforced by the observation that Model B significantly outperformed Model A, Satorra-Bentler χ2 diff = 320.66, df = 1, p < .001. Thus we decided to retain Model B.

Table 2 displays standardized factor loadings for the four factors in Model B, along with reliability values in the form of Cronbach’s alpha, which were acceptable, over .71. The item numbers in Table 2 are consistent with Sukhodolsky et al. (Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001, p. 694).

Table 2. Factor Loadings for the Standardized Solution, Obtained through Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Anger Rumination Scale

Note: The numbering of items is the same as in Sukhodolsky et al. (Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001, p. 694).

After assessing goodness of fit through CFA, we studied convergent validity by examining correlations between the ARS and other instruments that measure anger and aggression. Correlational results provided additional evidence that the constructs of anger rumination are correct, that is, they measure in a similar way as other scales of anger and aggression.

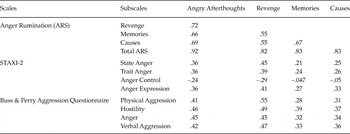

The subscales of the ARS were slightly to moderately correlated with state anger, trait anger, anger expression, physical aggression, hostility, anger, and verbal aggression (Table 3). As expected, ARS subscales correlated negatively with measures of anger control, such that the higher rumination was the lower anger management was. Correlations indicate the four scales of the ARS measure constructs that are somewhat similar to other scales of anger and aggression, suggesting convergent validity.

Table 3. Correlations between ARS Scales and Other Anger and Aggression Scales

Note: r > .20, p < .001. STAXI-2 = State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2.

Next we calculated the correlation between the ARS and Gross and John’s (Reference Gross and John2003) emotion regulation scales. The reappraisal and suppression scales, respectively, had correlations of –.07 (ns) and .27 (p < .001) with angry afterthoughts, –.17 (p < .05) and .18 (p < .01) with thoughts of revenge, –.03 (ns) and .17 (p < .05) with angry memories, –.08 (ns) and .21 (p < .01) with understanding of causes, and –.10 (ns) and .25 (p < .001) with total ARS scores. The negative correlations occurred in the expected direction, with reappraisal contrary to rumination. Suppression was positively correlated with rumination, which we expected since both are forms of poor emotional control. Low correlations between the emotion regulation scales (Gross & John, Reference Gross and John2003) and the ARS suggest some level of connection between the two constructs, bolstering the ARS’s convergent validity, and furthermore suggest that the ARS measures aspects not represented in Gross and John’s scales (Reference Gross and John2003).

With regard to demographic variables, age was not correlated with ARS outcomes on any of its four scales (angry afterthoughts, r = –.03; revenge, r = –.06; angry memories, r = –.03; understanding of causes, r = .01). This indicates rumination scale responses did not depend on participant age, which was between 20 and 60 years old.

Regarding sex (Table 4), no significant differences were found between men and women on three of the four rumination scales. The only difference was men scored higher than women on revenge. Nonetheless, according to Cohen’s criterion (Reference Cohen1988), the portion of variance explained by sex (2.6%) was considered minimal.

Table 4. Means (SD) and Gender Comparison of the Anger Rumination Scale

* p < .001.

Discussion

This study evaluated the validity of the ARS by Sukhodolsky and collaborators (Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001) in a Mexican sample. Findings supported a four-factor structure, the same as the original version (Sukhodolsky et al., Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001). As observed in CFA, the four-factor model had higher goodness of fit indices than others with fewer factors.

In this ARS validation study, results suggest: 1) the instrument is a valid measure of anger rumination in the sample studied, 2) the instrument’s four factors of rumination were retained: angry afterthoughts, thoughts of revenge, angry memories, and understanding of causes, and 3) ARS rumination scores correlate with other widely recognized measures of anger (STAXI-2, Miguel-Tobal et al., Reference Miguel-Tobal, Cano-Vindel, Casado and Spielberger2001) aggression (Buss & Perry, Reference Buss and Perry1992), and emotion regulation (Gross & John, Reference Gross and John2003), which suggests convergent validity in the Mexican sample and strengthens the ARS’s construct validity.

These results replicate those of other studies. The four factors were also valid in Great Britain, China, France, and Iran (Besharat, Reference Besharat2011; Maxwell et al., Reference Maxwell, Sukhodolsky, Chow and Wong2005; Reynes et al., Reference Reynes, Berthouze-Aranda, Guillet-Descas, Chabaud and Deflandre2013). Given that anger is a universal emotion (Averill, Reference Averill1982; Chon, Reference Chon, Hofsten and Bäckman2002), anger rumination likely is, too. This suggests the constructs of rumination are the same across cultures.

The four factors of rumination were highly correlated with one another (.55 –.72), but only slightly to moderately correlated with other anger and aggression instruments. This suggests that the ARS detects anger rumination, which other instruments do not assess. Therefore, validating the ARS in this Mexican sample has contributed an instrument for use. It seems to evaluate constructs not measured by other scales.

In this study, the ARS appraised anger rumination in the expected direction. High scores on its subscales were associated with a greater tendency to get angry, express anger, and physically assault or verbally abuse someone. Likewise, high rumination scores are associated with lower anger control (keep calm or relax). Overall, it seems the ARS measured anger rumination in a Mexican sample with convergent validity and in a similar fashion as the original scale (Sukhodolsky et al., Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001). These results seem to support the first hypothesis, which posited: rumination is associated with other measures such as anger and aggression (Anestis et al., Reference Anestis, Anestis, Selby and Joiner2009; Maxwell et al., Reference Maxwell, Sukhodolsky and Sit2009; Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Denson, Goss, Vasquez, Kelley and Miller2011).

This study’s second hypothesis was that men would score higher on the ARS than women. We found that was the case only for thoughts of revenge. Though differences were significant, sex explained only a minimal portion of variance (2.6%). In addition, differences were not found as a function of sex in angry afterthoughts, angry memories, or understanding of causes. These findings suggest minimal gender differences in anger rumination. Thus, this study’s second hypothesis was not supported by data, suggesting men and women are more similar than different in terms of anger (Archer, Reference Archer2004; Averill, Reference Averill1982; Bartz, Blume, & Rose, Reference Bartz, Blume and Rose1996) and anger rumination (White & Turner, Reference White and Turner2014).

The third hypothesis suggested there would be no relation between age and the ARS, which was confirmed. There was a slight tendency for rumination to be lower among older participants, but that correlation was less than .07. That is to say, the construct of rumination is relatively invariable over time. Given that the present study surveyed people over 20 years old, future studies should evaluate whether rumination differs in adults versus adolescents.

Some authors maintain that anger rumination is responsible for the duration of that emotion (Denson, Reference Denson, Forgas, Baumeister and Tice2009; Sukhodolsky et al., Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001). With that in mind, the ARS’s validity might increase if it were used in studies correlating it with anger duration, or studies of its stability over time (test-retest).

Statistically speaking, Model B, which was selected for its higher goodness of fit, did not reach the high standards desired. That goodness of fit level has two implications. First, it was preferable to competing models (A, C, D, and E), so Model B seems to be the best choice in the present study. Second, Model B has lower goodness of fit than one study found (Besharat, Reference Besharat2011), and similar goodness of fit to what another one reported (Maxwell et al., Reference Maxwell, Sukhodolsky and Sit2009). Therefore, future studies might employ other Mexican samples and see if this study’s goodness of fit findings are replicated, or examine models other than the ones we employed (i.e., with five or more factors).

In addition to evaluating goodness of fit statistics, the ARS was appraised with an external criterion, one of convergent validity with other tests. The result was that the ARS showed reasonable validity, and it seems its subscales are associated – logically and in the expected direction – with anger and aggression, measured by means of widely accepted and recognized tests like the STAXI-2 (Miguel-Tobal et al., Reference Miguel-Tobal, Cano-Vindel, Casado and Spielberger2001), the Aggression Questionnaire (Buss & Perry, Reference Buss and Perry1992), and the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, Reference Gross and John2003). In the present study, the ARS had empirical validity in that it was associated with other rumination-related constructs. This conclusion is important because the models ought not to be evaluated based on statistics (goodness of fit) alone, but on external criteria as well (Barret, Reference Barret2007). Future research may employ additional tests and criteria to examine the ARS’s validity. For instance, measurement and observation of aggressive behavior, reports from peers or siblings, or other scales.

Rumination scores in the present study can be compared to those collected in other countries, like China, Great Britain (Maxwell et al., Reference Maxwell, Sukhodolsky, Chow and Wong2005), the United States (Sukhodolsky et al., Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001), and Iran (Besharat, Reference Besharat2011). In most of those countries, rumination scores were lower than in the present study, where scores were higher. The country with the lowest rumination score was Great Britain (Mean = 1.75), followed by Iran (Mean = 1.92), the United States (Mean = 1.94), Mexico in the present study (Mean = 2.11), and finally China, which had the highest score (Mean = 2.13). This suggests countries differ in terms of their total anger rumination scores. As a result, future research must see if these differences are replicated. If so, researchers should assess whether the differences are significant, and whether aspects like the social, psychological, and especially cultural background of each country contribute to such differences. The study of anger rumination could make positive contributions, insofar as it identifies cultural characteristics that increase rumination in some countries and reduce the tendency to ruminate in others.

The sampling technique employed (snowball) may have undermined the results. Given that participants were recruited via students, we could not supervise the circumstances under which the questionnaires were administered. We do not know if participants responded hurriedly, nor the seriousness with which the test was administered. Moreover, we did not control how students responded when participants had questions about the questionnaire. These problems are typical of the sampling method employed. Future research could use other types of sampling and ensure the people administering the survey are capable, and see if these results are replicated.

Another limitation of this study is that the ARS’s convergent validity was ascertained with respect to three instruments: the STAXI-2 (Miguel-Tobal et al., Reference Miguel-Tobal, Cano-Vindel, Casado and Spielberger2001), Buss and Perry’s Aggression Questionnaire (Reference Buss and Perry1992), and the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, Reference Gross and John2003). While those instruments are valid in Mexican populations (Matsumoto et al., Reference Matsumoto, Yoo and Nakagawa2008; Oliva et al., Reference Oliva, Hernández and Calleja2010; Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Ortega, Rincón, García and Romero2013), they may not provide enough validity evidence. Future studies could bolster the usefulness of the ARS by exploring its use with additional measures, for instance, interpersonal adaptation and functioning, psychopathologies associated with rumination, and even physical illnesses derived from anger rumination.

Appendix

Items on the Anger Rumination Scale

(Sukhodolsky et al., Reference Sukhodolsky, Golub and Cromwell2001) Adaptation in a Mexican Sample