The effects of age on neuropsychological development, especially memory, are widely studied in different age groups (for a review see Park & Festini, Reference Park and Festini2017). The execution of a task involving short-term memory of visual stimuli requires the integration of visual features and also the association of various other memory resources that vary according to age (Benton Sivan, Reference Benton Sivan1992; Salles et al., Reference Salles, Bandeira, Trentini, Segabinazi and Hutz2016). In general, research indicates that children and the elderly seem to have more difficulty in short-term visual memory tasks compared to young adults, for example (Swanson, Reference Swanson2017).

In addition to age, it is known that other measures, such as intelligence quotient (IQ), is also related to some aspects of memory (e.g., Gray et al., Reference Gray, Green, Alt, Hogan, Kuo, Brinkley and Cowan2017). To contribute to the interpretation of specific results of neuropsychological tasks and tests, IQ measures occupied for a time, prominent place in neuropsychological assessment (Crawford, Reference Crawford, Goldstein and MacNeil2012). However, some studies suggest a portion of shared variance between working memory and IQ measures (e.g. Chuderski, Reference Chuderski2015), indicating that better results (above average) in cognitive tasks, such as intelligence tests, would be dependent on the ability to store the information for a short period, and also the ability to process it quickly (Jastrzębski et al., Reference Jastrzębski, Ciechanowska and Chuderski2018).

Brazilian studies have pointed out the positive and significant ratio between the years studied and performance in different neuropsychological tasks (e.g., Leite et al., Reference Leite, Miotto, Nitrini and Yassuda2017). Among the cognitive abilities, it is understood that the ability to remember visual stimuli is related to socio-demographic and socio-cultural aspects (Ardila, Reference Ardila2018). This ability can be assessed by The Benton Visual Retention Test (BVRT), which measure visual memory and also evaluates visuoconstructive abilities through tasks that involves the copy of geometric figures of increasing complexity. Research on the role of the years of education in BVRT performance in Brazil, for example, lead to separated norms for the test considering this variable in children, adolescents and elderly (Salles et al., Reference Salles, Bandeira, Trentini, Segabinazi and Hutz2016), results also found in recent research with young adult and intermediaries (Lima, Reference Lima2014).

Knowing that age, IQ and years of study influence the performance in neuropsychological tasks, we sought to assess the influence of these variables in visual memory and visuoconstructive abilities with BVRT measured in healthy and clinical samples evaluated. According to literature, o BVRT has been used internationally to detect and monitor neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease and to provide a profile of visual memory and praxis skills in brain injury (Messinis et al., Reference Messinis, Lyros, Georgiou and Papathanasopoulos2009), neurodevelopmental (i.e, ADHD) and psychiatric disorders (Venezia et al., Reference Venezia, Gorlyn, Burke, Oquendo, Mann and Keilp2018). In all cases, the clinical samples typically present poorest performance than controls. Thus, Study 1 aimed to demonstrate the age-related changes in the performance of children, adolescents, adults and elderly in BVRT. Study 2 investigated the relevance between age, IQ and years of education in the BVRT performance using a structural equation modeling (SEM), controlling the condition group (clinical vs. control). This analysis enables the testing of complex theoretical models and multiple relationships between variables, while most of the studies conducted so far used correlational methods and comparison groups to evaluate the independent effects of these variables (e.g., Lima, Reference Lima2014; Souza et al., Reference Souza, Segabinazi and Bandeira2012). In addition to researches conducted with the BVRT in Brazilian samples (Salles et al., Reference Salles, Bandeira, Trentini, Segabinazi and Hutz2016; Segabinazi et al., Reference Segabinazi, Junior, de Salles, Bandeira, Trentini and Hutz2013; Zanini et al., Reference Zanini, Wagner, Zortea, Segabinazi, Salles, Bandeira and Trentini2014) this study contributes to investigate the relationships between different variables on performance in visual memory and visuoconstructive abilities.

Method

Design, Participants and Procedures

The study had a quantitative, descriptive and cross-explanatory design. The convenience sample was composed by 624 individuals in a range from 6 to 89 years (M = 25.40, SD = 22.34) and 60% were female. The sample consisted of participants from different surveys (see Segabinazi et al., Reference Segabinazi, Junior, de Salles, Bandeira, Trentini and Hutz2013), and included neurologically healthy people (78%). Exclusion criteria for the healthy group were: (a) Presence of neurological, psychiatric, or medical diseases, (b) lower IQ, (c) more than one failure in school, (d) presence of depressive symptoms, (e) use of benzodiazepines or ilicit psychoactive substances, (f) signs of cognitive impairment. Clinical groups were organized as follows: 58 children and adolescents diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (Duarte Junior, Reference Duarte Junior2012), 45 children diagnosed with anxiety disorder (AD) (Guarnieri, Reference Guarnieri2014), nine elders with possible Alzheimer’s dementia diagnosis (Zanini et al., Reference Zanini, Wagner, Zortea, Segabinazi, Salles, Bandeira and Trentini2014), and 25 adults and elderly patients with left or right hemispheric stroke (Zortea et al., Reference Zortea, de Jou and de Salles2019). Thus, the study included participants from four age groups: Children (n = 256; 49.2% female), adolescents (n = 101; 67.8% female), adults (n = 131; 60% female) and elderly (n = 88; 75% female). Participants with classification below of the 10th percentile in the WASI and in the Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices – General Scale (Campos, Reference Campos2003), or below of the 25th in the Raven’s Coloured Progressive Matrices were excluded from the study. More information about inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in the original reports cited. Data collection was conducted individually and in a standardized way by undergraduate and postgraduate Psychology students trained previously. The training consisted of meetings for scoring discussion. Interrater reliability and Kappa coefficient were calculated, and the values found were excellent (Salles et al., Reference Salles, Bandeira, Trentini, Segabinazi and Hutz2016).

Typical children were recruited from public and private schools, while children with ADHD and anxiety were selected from a community care program at a hospital where they were diagnosed by a multidisciplinary team (psychiatrists, pedagogues, neuropsychologists, etc.). Elderly individuals with possible diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease were also selected for convenience. 68.75% lived in nursing homes and diagnosis was indicated by a physician (geriatrician, neurologist, or psychiatrist).

All participants were assessed in an appropriate environment in general classrooms or service. Typical children and adolescents were evaluated in schools, adults and elderly in a public university, children with ADHD and AD in public hospitals or schools, stroke patients at a public university or in appropriate rooms in their homes and elderly with possible Alzheimer’s dementia in their homes or in geriatric homes.

An informed consent was obtained for all the participants. For children the consent was obtained from parents or guardians and for elderly people who lived in geriatric homes, consent was obtained from the institution responsible or family. The applications took between 15 to 60 minutes. Instruments not relevant to this study were also used during data collection and no interference effects were observed. The study is in accordance with the ethical standards for research in human beings, having previously been approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (PEC 069/2008).

Instruments

Sociocultural Questionnaire: Composed by questions regarding sex, age, years of education, socioeconomic status, health history, etc. The questionnaire was answered by the participants themselves in the group of adults and elderly and by parents or guardians in the group of children and adolescents.

Benton Visual Retention Test – BVRT (Benton Sivan, Reference Benton Sivan1992; Salles et al., Reference Salles, Bandeira, Trentini, Segabinazi and Hutz2016, Segabinazi et al., Reference Segabinazi, Junior, de Salles, Bandeira, Trentini and Hutz2013): combinations of Administration A (Form C) were used for evaluation of visual memory, and Administration C (Form D), to assess the visuoconstructive abilities. To better understand the results and following the rules proposed by the Brazilian Handbook BVRT (Salles et al., Reference Salles, Bandeira, Trentini, Segabinazi and Hutz2016): Administration A (Form C) was called Administration A (Memory) and Administration C (Form D) was called Administration C (Copy).While in Administration A (Memory) each stimulus are displayed for 10 seconds, in Administration C (Copy) there is no maximum time of exposure to the stimulus. Each form has 10 items, with the first two consisting of one geometric figure, and the other eight of two bigger figures and one smaller peripheral figure. The test was scored by trained psychologists who participated in the test standardization process in Brazil and followed the criteria of the test Brazilian Handbook (Salles et al., Reference Salles, Bandeira, Trentini, Segabinazi and Hutz2016). In the database, each stimulus (item) of the two forms has been identified with a score of 1 (item executed correctly) or 0 (item executed with at least one error in any of the six categories of error (Omissions, Distortions, Perseverations, Rotation, Position and Size Exchanges errors). In this study, the reliability (α) of Administration A (Memory) and Administration C (Form D) were .70 and form .72 respectively. The variable included in the model was a Rasch Score from Administration A (Memory) and Administration C (Copy) provided by previous studies (Segabinazi et al., Reference Segabinazi, Yates, Salles, Trentini, Hutz and Bandeira2014).

IQ Evaluation

Due to the fact that participants were from different age groups and from different surveys, the following tools for evaluating the IQ were used:

Raven’s Coloured Progressive Matrices (Angelini et al., Reference Angelini, Alves, Custódio, Duarte and Duarte1999): To evaluate the analogical reasoning. It was used in the evaluation of 260 children aged 6 to 11 years and 8 months. The instrument was standardized with a representative sample of Brazilian children (N = 1547) from the city of São Paulo, with ages varying from 5 to 11 ½ years, from public schools (municipal and state) and private schools. The sample was divided into 14 age groups, ranging from 4 years to 9 months and 11 years and 9 months, each range being amplitude of 6 months. The instrument is divided into three series A (the identity and apprehension change in continuous patterns), Ab (apprehension of distinguished figures with all spatially related) and B (apprehension of similar changes in spatially related figures and logically). In each series, it was requested that the child visualize an incomplete picture and identify among six alternatives, which one would adequately complement the design.

Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices – General Scale (Campos, Reference Campos2003): The instrument has 60 problems divided into five groups (A to E) with 12 items each and was used in 178 adolescents and adults between 12 and 46 years. The problems have increasing difficulty and each series provides five times to understand the method and five progressive assessments of individual capacity for intellectual activity. Thus, the instrument evaluates the participant’s ability to develop a systematic method of reasoning to solve the task.

Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence Manual – WASI (The Psychological Corporation, 1999; Trentini et al., Reference Trentini, Yates and Heck2014): the WASI four subtests was used - Vocabulary, Block Design, Similarities and Matrix Reasoning. These four subtests comprised the Full Scale IQ and provide the Total IQ (IQT–4), measuring various aspects of intelligence such as verbal knowledge, processing and visual information, spatial reasoning, non-verbal and crystallized and fluid intelligence. The scale was answered by 111 adults and elderly in a range of 31–75 years.

IQ Estimation

Whereas the data obtained by the Raven Scales do not provide a measure of IQ, an estimation data was searched through a regression analysis having as dependent variables: age, years of education and the Raven score. Data used is these analysis was provided by a sample of 353 participants from the standardization research for WASI in Brazil (see Trentini et al., Reference Trentini, Yates and Heck2014 for more information) in which, both instruments, WASI and Raven were used (Special Scale or General Scale, depending on age) to seek evidence of validity of WASI. The age range of the validation sample was six to 84 years and no clinical individuals took part. No differences were found by education, but a difference by age (t = 2.50, p < .001) with small effect size (d = .15) between validation’ sample and present sample.

Regressions searching to estimate IQ were performed for children and adults. In the children’s model, age (β = –.56), education (β =.31) and Raven (β = .74) were significant predictors, explaining 58% of the WASI total variance. Collinearity indices were adequate, with tolerance ranging between .63 to .73 and VIF ranging between 1.47 to 1.53. The equation used to IQ estimation in children was: 62.307 + (Age*–.404) + (Education*.806) + (Raven*1.702). In the adult model, age (β = –.69), education (β = –.63) and Raven (β = 1.35) were significant predictors again, explaining 76% of the total variance. Collinearity indices also were adequate in this model, with tolerance ranging between .26 to .33 and VIF ranging between 3.02 to 3.82. The equation used to IQ estimation in adults was: 31.489 + (Age*.495) + (Education*–1.635) + (Raven*1.708). Thus, it was possible to predict the IQ scores of participants who had an only evaluation with Raven and that are included in this research. Throughout the text, this variable will be called IQ.

Data Analysis

Study 1

To meet the first objective, that is, to demonstrate the age-related changes in performance BVRT, the descriptive analysis (mean and standard deviation) of age, IQ, years of education and overall performance in BVRT through the Rasch score in Administration A (Memory) and Administration C (Copy), which henceforth will be called "Memory" and "visuoconstructive abilities" ("Visuo") for graphic adequacy purposes. We perform a one-way MANOVA and Games-Howell post hoc testing to compare performance in Rasch scores of the sample in both BVRT administrations, as well as in years of education and IQ. The independent variable was the age group: Children (6 to 12 years), adolescents (13–18 years), adults (19–59 years) and elderly (60–89 years). The effect sizes were calculated using eta-squared (η2).

Study 2

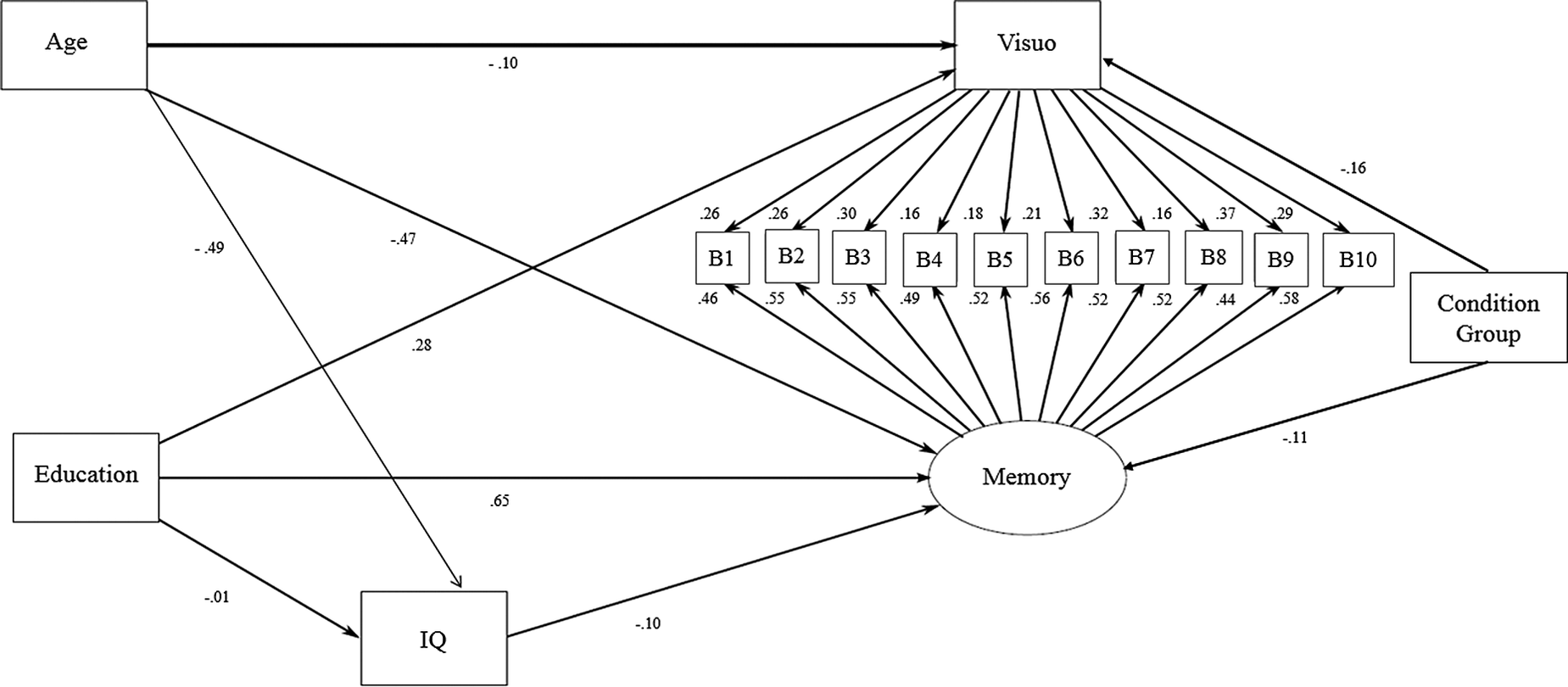

To contemplate the second objective of the study, which is to investigate the relationship between age, IQ and years of education with the performance BVRT, controlling the condition group (clinical vs control), was tested through structural equation modeling (SEM) models by specifying the items Administration A (Memory) of BVRT (B1 to B10 variables in the graph) as explained by a double imaging scale and the visual memory visuoconstructive abilities of individuals. This variable was estimated from a Rasch analysis with the items from Administration C (copy) of BVRT held in another study (Segabinazi et al., Reference Segabinazi, Yates, Salles, Trentini, Hutz and Bandeira2014). It is, therefore, a latent variable, but that, having been previously estimated from an independent set of indicators, was inserted as an observable variable in the model (variable "Visuo"). Moreover, the age, years of education and IQ were included in the model as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The theoretical model of structural equations with the variables age, years of study (Education),IQ, Visuoconstructive Skills (“Visuo”), and Memory.

The estimation method chosen was the Weighted Least Squares Adjusted Means and Variances - WLSMV, suitable for measurement models with categorical variables (in this case, the right or wrong answers on each copy and memory item). The software used was the R (R Core Team, 2017), package lavaan (Rosseel, Reference Rosseel2012), including group equality constraints with the argument “regressions”. After the investigation of the general theoretical model, considering the expected differences in the different stages of development represented in the overall sample we carried out a multi-group analysis. Whereas relations between model variables could vary according to the different age groups of the total sample (including healthy and clinical participants), we decided to divide the sample into four age groups, as previously mentioned. The fit of the models was evaluated through the following indicators: χ2/df (chi-square ratio/degrees of freedom); Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Values of χ2/df are adequate when less than 2. CFI and TLI above 0.95 suggest excellent fit, while values above 0.90 indicate that the fit quality is satisfactory. RMSEA values less than .08 indicate acceptable fit (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999). We emphasized that to keep the confirmatory nature of the study, the modification indices of templates for each group were not analyzed, although the information could elucidate possible relationships not initially proposed in the model.

Results

The results of Studies 1 and 2 will be presented in the following separate sections.

Study 1

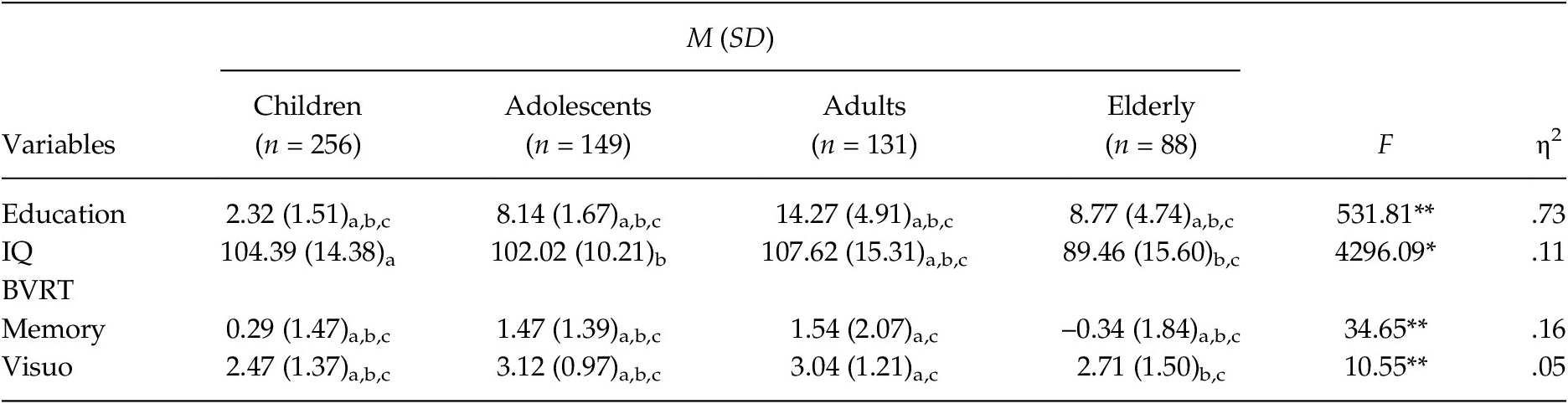

Table 1 presents the mean and standard deviation in IQ variables, age, years of education, the performances in scores of Rasch memory and Rasch copy of BVRT, and the Rasch score equivalent to a standardized score, with M = 0 and DP = 1 (for more information about the Rasch score was obtained, see Segabinazi et al., Reference Segabinazi, Yates, Salles, Trentini, Hutz and Bandeira2014). Significant differences were found among the four groups, F(12, 1734) = 65.25, p < .001; η2 = .31. In the Table 1, the values of F and η2of the MANOVA performed for each variable are described, as well as the results of the post hoc analyzes.

Table 1. Means and Standard Deviations for Years of Education, IQ and BVRT Scores by Age Groups

Note. M(SD) = Mean (Standard Deviation); IQ = intellectual quotient; BVRT = Benton Visual Retention Test.

a, b, c = Same letters indicates significant differences with p < .001 between groups.

* p < 0.05; ** p < .001.

The Games-Howell post hoc tests corroborated the contrast among the four age groups, since all groups showed significant differences. For the years of education, the group of adolescents and the elderly were the only ones not to present significant differences. As for IQ, the children group showed no significant differences when compared with the group of adolescents and the elderly group. Comparison of scores on Memory and BVRT’s Visuo indicated for both measures that groups of adolescents and adults do not differ significantly from each other, to score in Visuo children and elderly did not show significant differences.

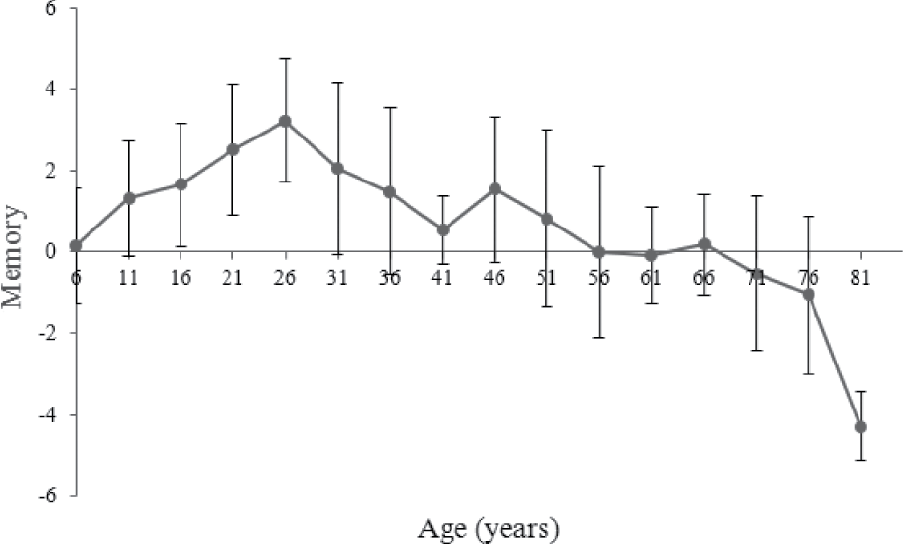

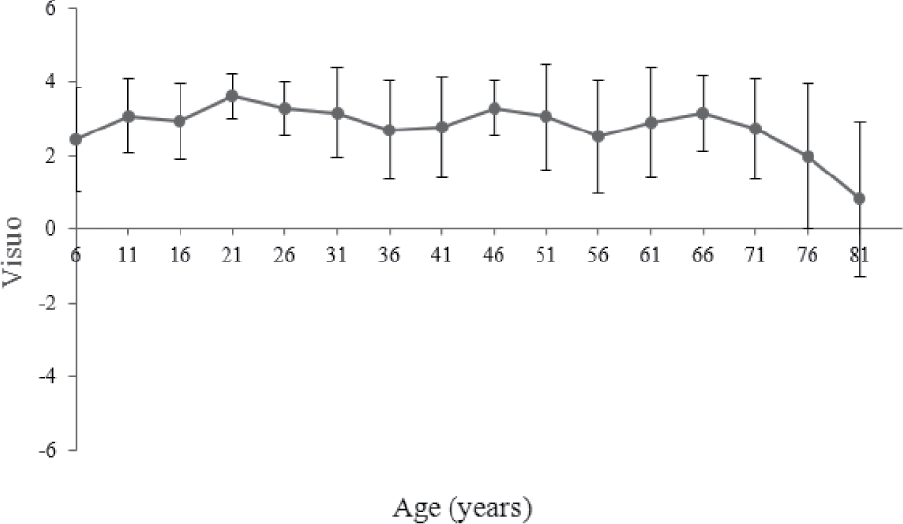

Figures 2a and 2b represent the performance of BVRT found in the overall sample (including healthy and clinical) as a function of age. In Figure 2a, we note that an interesting pattern emerge when we plot the age-related data for both scores BVRT because it reflects the variation of visual memory performance (“Memory”) with increasing age. It is observed that from 6 to 26 years there is an increase of visual memory ability, but you can see a decline after age 30, which increases after 66 years. Meanwhile, Figure 2b shows a different pattern to visuoconstructive abilities ("Visuo") in relation to age, expressed by a slight increase in the scores among groups of children and adolescents, maintenance of performance in adolescents and adults and a decrease in the elderly people, especially after 66 years. We also built graphics excluding clinical population of this study, but significant changes were not observed between the two forms of analysis, only a small reduction in the values of standard deviations. Thus, it was decided to maintain the representation of the total sample in Figures 2a and 2b.

Figure 2a. BVRT Visual Memory Score (Memory) with standard deviation according to age.

Figure 2b. BVRT Visuoconstructive Skills Score (“Visuo”) with standard deviation according to age.

Figure 3. The general model of the relationships between the variables age, years of study, IQ,Visuoconstructive Skills (“Visuo”), and Memory.

Study 2

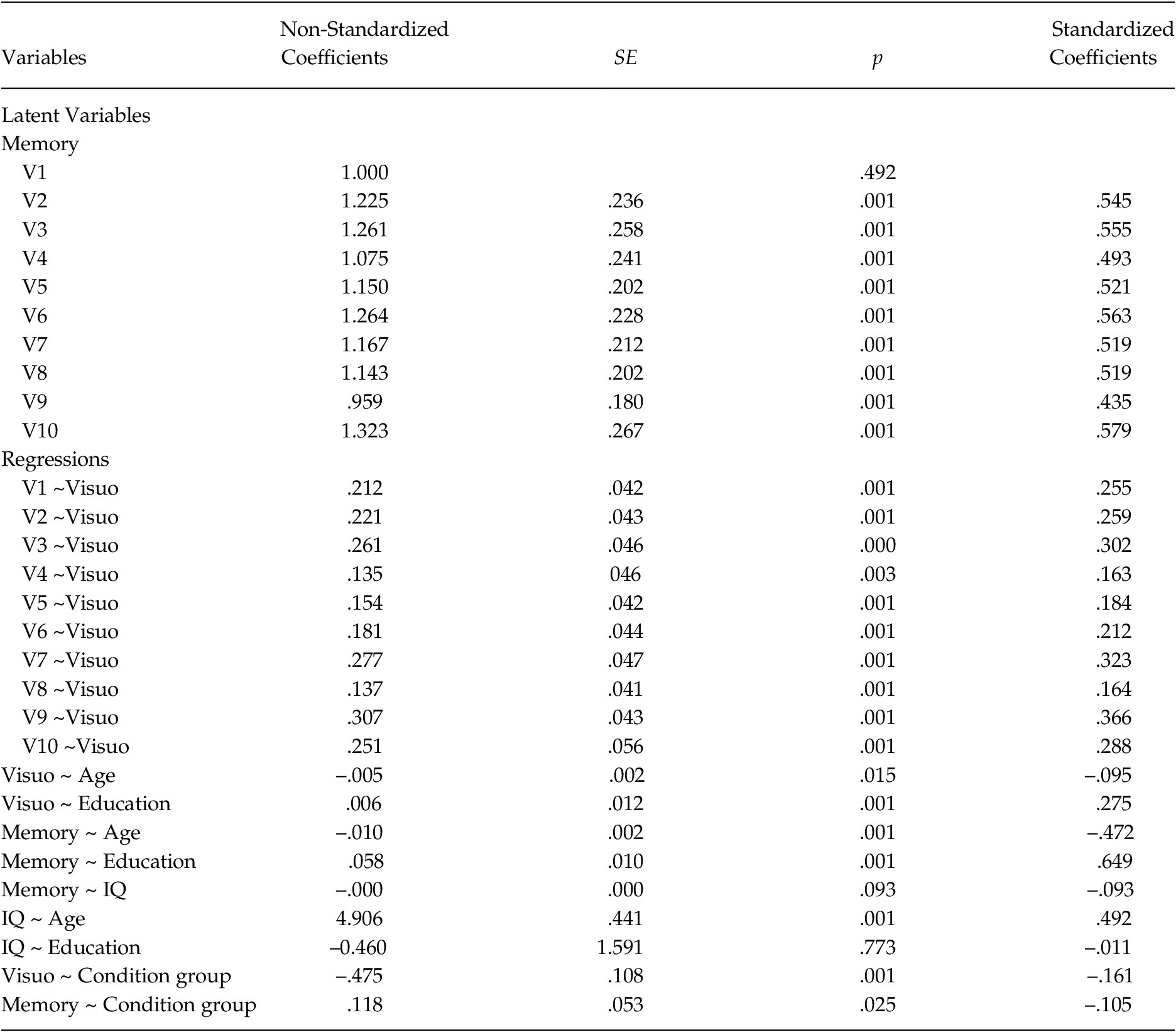

Initially, intercorrelations between variables are presented in Table 2. In the total sample, memory was moderately correlated with IQ, while visuo was moderately correlated with memory. Memory and visuo were weakly related to age, education and condition group. The SEM was performed and sought to establish the relationship between age, IQ, years of education and performance in both BVRT administrations. The model showed a good fit to the data, χ²(73) = 130.44, p < .001; CFI = .92; TLI = .93; RMSEA, 90% CI = .04 [.03, .05], p =.99 (Figure 3). The values of standardized and non-standardized estimated parameters are presented in Table 3.

Table 2. Intercorrelations between Age Years, Education, IQ, Memory and Visuo

Note. B1 to B10 = Observable variables of the SEM model.

a = point-biserial correlation.

** p < .001.

Table 3. Values of Non-Standardized and Standardized Estimated Parameters of SEM Model

A graphic has been built to provide the performance on memory and visuoconstructive abilities (BVRT) in the overall sample (Figure 3), one can observe an increased contribution of years of education in determining the visual memory performance (β = .65) and visuoconstructive abilities (β = .28), with the model explained 50% of the variance (R 2 = .50). In addition, all relationships were significant (p < .001).

Discussion

With regard to BVRT scores, were found significant differences in memory for all groups except among adolescents and adults, and the performance of the latter group was the best of all, followed by adolescents, children and, lastly, the elderly group. The results highlight evidence based on relations to other variables for the BVRT, in this case the ability of BVRT to show developmental changes. The results are in accordance to other cross-sectional study that investigated similar visual memory resources (Murre et al., Reference Murre, Janssen, Rouw and Meeter2013), which highlighted an increase in visual memory skill with increasing age in the group of children and the group of adults and even a tendency in the adult group (after 20 years) a decrease in this performance that increases in the elderly group. Figures 2a and 2b of this study showed a performance trend similar to developmental charts that feature a U-inverted pattern as a function of age for both variables, memory and copy. However, this was mainly for memory, result that is in accordance with the findings of publications comparing test scores and visual memory tasks in different age groups (Dias et al., Reference Dias, Rezende, Malloy-Diniz and de Paula2018). These results also confirm evidence of a decline in visuospatial abilities with increasing age in adults and in the elderly (Hale et al., Reference Hale, Rose, Myerson, Strube, Sommers, Tye-Murray and Speha2011). It also reinforce the findings regarding the decline of certain cognitive abilities such as the ability to memorize visuospatial stimuli during adulthood, as opposed to the belief that it would begin only after 60 years (Salthouse, Reference Salthouse2009). Still, there are several factors that interact in order to minimize possible damage in daily life, changing the trajectory of this relationship. Thus, factors such as motivation, persistence, personality characteristics of the individual and their ability to adapt and change your daily activities, and also the cognitive strategies developed over the years of life may offset some of these losses (Frankenmolen et al., Reference Frankenmolen, Overdorp, Fasotti, Claassen, Kessels and Oosterman2017).

The results of analysis using SEM to determine the performance BVRT corroborated earlier studies on the influence of variables such as age and years of education in Brazilian samples and had used less robust statistical analyzes (Lima, Reference Lima2014; Salles et al., Reference Salles, Bandeira, Trentini, Segabinazi and Hutz2016). Even though the analysis using SEM enabled to test multiple relationships in a sample with different age groups, the design of this research is cross-sectional study. So, as much as the results appear to enrich the understanding of the developmental aspect of the visual and visuoconstructive memory abilities, these are differences of age and no age-related changes, like a longitudinal study can show (Sliwinski & Buschke, Reference Sliwinski and Buschke1999). Regarding the adjustment of the model, it was well-adjusted and explaining 50% of the variance of visual memory.

The model shown a negative and significant contribution of age to the performance of administrations A and C of BVRT, a finding that is in accordance with results and discussion already presented above and also with other work that proposed a structural model to explain the performance in neuropsychological tests considering this variable (Murre et al., Reference Murre, Janssen, Rouw and Meeter2013) and other research that investigated aspects of visual memory (Dias et al., Reference Dias, Rezende, Malloy-Diniz and de Paula2018). The variable years of education have demonstrated a greater contribution to the performance of BVRT, which is a positive and significant contribution, what agrees to the studies reviewed that emphasize the role of years of education for the best performance neuropsychological tests (eg., Sierra Sanjurjo et al., Reference Sierra Sanjurjo, Saraniti, Gleichgerrcht, Roca, Manes and Teresa2018).

The results of the analyses of differences between groups and the SEM model were consistent with the hypothesis of the age contribution and the magnitude of the relationship of this variable in visual memory and visuoconstructive abilities. Specifically, the SEM model highlighted a strong role of the years of education on visual memory. On the other side, IQ was not related to education or memory. Possibly, in a sample with clinical and healthy participants, the relation between IQ and education and, consequently, their relations with visual memory can be different from theoric expectancy, likes in this study, since clinical participants tended to present a minor level of education compared to the healthy.

Is also important to consider the limitations concerning the sample size, instruments used and the fact that the results are applicable to Brazilian subjects only. Besides this fact, and together with the results of other studies that have used cross-sectional and longitudinal design to evaluate the effects of aging on cognition suggest that the cognitive decline associated with age begins relatively early in adulthood (e.g., Swanson, Reference Swanson2017, Figure 1). However, it is important to note that not all cognitive functioning aspects have related declines with age, especially when considering measures based on accumulated knowledge, such as performance on vocabulary or general information tests. A potential limitation of this study was not including other sociocultural variables, besides years of study. Aspects such as socioeconomic status have been shown to be associated with a series of cognitive measures (Ardila, Reference Ardila2018). It is proposed that future research on the role of age, address multivariate relationships in longitudinal studies and consider sociocultural variables.