Introduction

At its most fundamental, a society’s political conflicts concern who has what rights to live and work within it. In many cases, ethnoracial and religious distinctions are the basis for limited rights or exclusion. Even though these social boundary conflicts seem perennial, the persecution of minorities is not inevitable (Moore Reference Moore2007 [1987]). Ethnoreligious boundaries are an opportunity for persecution, not a prescription. In fact, the roots of a persecution may have little direct relationship to a majority-minority divide. As Nirenberg (Reference Nirenberg1996: 11) argued, “[V]iolence against minorities is not only about minorities” (italics in original); violence and exclusion are also about majorities. The engines of persecution are often social and political processes occurring within majority groups.

However, the conflict theory approach to studying ethnic violence brings an almost unitary focus on the ethnic divide. Perhaps because of the nearness and moral offense of nineteenth- and twentieth-century ethnic violence, the large literature on ethnic conflict has spent decades honing theories of what conditions and processes lead to violence and war (Brubaker and Laitin Reference Brubaker and Laitin1998; Gurr Reference Gurr1993). The main strands of research concern the social psychology of ethnic groups and symbolic boundaries (Hale Reference Hale2008; Rydgren Reference Rydgren2007), the distribution of power and resources (Hechter Reference Hechter2013; Wimmer Reference Wimmer2013), and the role of movements and opportunities (McAdam et al. Reference McAdam, Tarrow and Tilly2001; Olzak Reference Olzak1989). Across these foci, scholars compare groups and the power relationships between them (Cederman et al. Reference Cederman, Weidmann and Gleditsch2011; Kopstein and Wittenberg Reference Kopstein and Wittenberg2018; Siroky and Hechter Reference Siroky and Hechter2016). Focusing on interethnic relations is most useful for studying microlevel processes, like prejudice and discrimination (Adida et al. Reference Adida, Laitin and Valfort2016; Hjerm et al. Reference Hjerm, Maureen and Danell2018; Schlueter et al. Reference Schlueter, Schmidt and Wagner2008). When it comes to studying the actions of the state and political elites, the ethnic divide is not necessarily the most central conflict (Bush Reference Bush2003). As connected to the state, the exploitation of social boundaries serves the purposes of reinforcing power. Whose power, then, is reinforced by persecuting a minority group? And who is that power fortified against?

In this article, I examine expulsions of Jews in the medieval western Holy Roman Empire. In related research, Johnson and Koyama and coauthors (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Johnson and Koyama2017; Finley and Koyama Reference Finley and Koyama2018; Johnson and Koyama Reference Johnson and Koyama2019) have investigated antisemitic violence in medieval Europe. They do not differentiate between expulsion and mob violence, as they are interested in all types of religious persecution. I exclusively study expulsions. As official proclamations by local governments mandating that a category of people leave their homes and livelihoods, these expulsions were cases of state violence against Jews. Expulsion edicts were obviously directed at Jews, but Jews were relatively powerless. Christians controlled all parts of governance. Jews and Christians were not arguing over which of them belonged in their society; Christians were in conflict with other Christians about social and political boundaries. Understanding the expulsions requires an investigation of their political context to identify what conflict between Christians the expulsions were part of.

Using a new dataset, I analyze expulsions in cities in the Western Holy Roman Empire that had Jewish residents from 1000 to 1520 CE. To explain why expulsions occurred, I ask what it was about the majority—about Christians—that could have led to state violence against Jews. Because expulsions were policy outcomes, I look to medieval political organization and political economy for answers. Johnson and Koyama (Reference Johnson and Koyama2019) argue that change in the need for religious legitimacy promoted an increase in antisemitic persecution. I argue that the nature of religious legitimacy changed. Christian authorities felt increasingly responsible for the righteousness and purity of their domains. Coupled with the revenue-hungry pressures of medieval political economy, political elites jostled to assert and maintain autonomy and authority in delimited, territorializing polities—city-states, principalities, and episcopates. Johnson and Koyama theorize that medieval political fragmentation made weak states that used identity rules to calibrate their administrative and fiscal capacity with their administrative and fiscal needs. I counter that it was not government strength or weakness but political competition that drove expulsions. I weigh specific factors of competition, including whether authority was fragmented, that are not strictly indicators of government capacity.

Expulsions were rare, though their incidence climbed considerably from the fifteenth century. The results of my analyses show that Jews were expelled where power and resources were contested among political elites in the upheaval of transition to new ideals of governance. City rulers faced ambiguous hierarchies of power and conflicting rights, challenges for sovereignty that they attempted to solve through their policies toward Jews. This study reinforces the interpretations of case studies of expulsions in England (Katznelson Reference Katznelson, Katznelson and Weingast2005; Stacey Reference Stacey, Prestwich, Britnell and Frame1997) and France (Barkey and Katznelson Reference Barkey and Katznelson2011; Jordan Reference Jordan1989) that point to political competition and negotiation among Christian elites. I expand on the work of Wenninger (Reference Wenninger1981) and Johnson and Koyama (Reference Johnson and Koyama2019) by drawing attention to the role of local political institutions and relationships amidst sovereign fiscal insecurity.

Many of our ideas for defining states and government come from studying European territorialization through the medieval and early modern centuries. Returning to this era with a new eye for how “the have-nots lose in disorganized politics” (Key Reference Key1950: 307) is another view into the importance of political structures for understanding state power. In contexts of intraethnic conflict over political control, minority groups can be treated like pawns. Ethnic exclusion and violence are intragroup weapons for the consolidation of power.

Medieval Politics

Jewish–Christian relations changed because Christian ideas and institutions changed. The most influential changes were (1) territorialization of political dominions and (2) new and more prescriptive theocratic understandings of Christian piety. The former provoked conflict between rulers over resources and authority. The latter revolutionized the relationship between rulers and their subjects by placing responsibility for community righteousness in the hands of rulers. Together, they intensified political competition for legitimacy and control. Rights to govern and control Jewish residency and activities were subject to the same conflicts as other rights over privileges and authority. As individual Jews or families contracted with various towns or elites, they “increasingly found themselves in the crossfire between competing rulers” (Haverkamp Reference Haverkamp, Hsia and Lehmann1995: 28).

Territorialization

The main struggle for medieval polities was governance capacity. Governance capacity primarily meant fiscal capacity, extracting enough income to maintain domains (Johnson and Koyama Reference Johnson and Koyama2017a; Mann Reference Mann1986; Olson Reference Olson1993; Tilly Reference Tilly1990). Income paid for household expenditures, from food to clothing to travel, as well as staffing and contracting with other notables for security services at home and at war and construction and upkeep on family homes and strongholds necessary for rule. In the High Middle Ages (1000–1250 CE), more than 90 percent of Germanic people were legally unfree serfs, servants, and ministerials (Haverkamp Reference Haverkamp1988), whose status implied financial burden on their overlords. Feudal lords were responsible for providing implements, harvest-time labor, cattle, and seeds (Toch Reference Toch2003). Fragmented rights (Volckart Reference Volckart2002) and varying resources created complicated competition over how to obtain income.

Given difficulties of extracting land-based taxes, revenues from towns were attractive to rulers. Urban revenues were collected by impositions of fees, excise taxes, tolls, confiscation, and new tools like annuities (Isenmann Reference Isenmann2012; Stasavage Reference Stasavage2011). In many urban centers, the sources of revenue did not automatically and without question belong to one local ruler. Each revenue stream developed from customary law and specific grants of rights. The titular city ruler was often in competition with clerical authorities, the emperor, prominent guildsmen, and other local elites, who may have purchased individual customs and taxation rights or been granted them by the emperor. Further, cities were often run by agents, mortgage holders, and/or city councils. Local officials performed various combinations of legal, fiscal, and administrative functions, depending on what self-governance rights were bought or bestowed on a city and local institutional cultures (Isenmann Reference Isenmann2012: 236). Castellans and senior administrators (Amtmänner) were identifiable agents of an overlord. Civic juries (Schöffen), city chairmen (Bürgermeister), and city councils (Räte) represented a peer group of local elites in legal and/or administrative decision making. Bailiffs (Schultheißen) enforced legal and fiscal agreements, particularly concerning the emperor’s coffers. All these titular and office-holding political elites were city rulers. Urban centers had political competition built into their local governance; any mix of these rulers might be vying for fiscal superiority or monopoly on their own behalf or as agents of a principal.

Commercialization of sovereignty, especially through office granting, was the foundation of territorialization (Reichert Reference Reichert, Burgard, Haverkamp, Irsigler and Reichert1996: 278). Territorialization was the erection of delimited administration (Giddens Reference Giddens1987) where rulers could demand and expect compliance with taxation and regulation (Volckart Reference Volckart2000) because they had pushed out or overcome their competitors. As physical, economic, and legal borders (Boes Reference Boes and Betteridge2007), city walls were bounds for new conflicts over sole sovereignty in regard to all city occupants and activities, including over Jews. In Cologne in 1424, the agreement to expel Jews was the cornerstone of the settlement of a nearly 10-year conflict between the city and the archbishop regarding who held supreme sovereignty in the city (Wenninger Reference Wenninger1981). Archbishop Dietrich, elected to his post in 1414, disregarded the status quo, established by his predecessors, that rights over Jewish residency were jointly held with the city’s secular government. He had inherited the desire to reestablish sole sovereignty over the whole city from the previous archbishop, his uncle Friedrich III; Archbishop Dietrich saw disputing shared jurisdiction over Jews as an opportunity to accomplish this (ibid.: 79). His campaign for sovereignty soon also included legal challenges to the city’s attempts to raise taxes, which he saw as disturbing his rights over through trade along the Rhine River, on which the city was located. With the 1424 expulsion agreement, the relationship became friendly. The archbishop gave up aspirations for supremacy within the city, but he gained sole possession of rights over the expelled Jews, whom he settled within his jurisdiction in Deutz, Bonn, and elsewhere. From these Jews the city government had collected 18,800 marks in taxes, not to mention thousands of marks through coerced direct loans, in the last 10 years alone. Archbishop Dietrich became renowned for having “the most and richest Jews” in Germany (ibid.: 93).

New Theocratic Understandings of Christian Piety

Christian understandings of the historical and symbolic role of Jews preserved and enforced the social boundary between medieval Christians and Jews. Christians, living under the new covenant with God through the death of Jesus, were accountable to canon law. Canon law did not apply to Jews, who lived under the old covenant and Mosaic law (Dorin Reference Dorin2015: 119). Christian piety relied on this contrast, both linking and distinguishing Christians from their supposed predecessors. Sara Lipton (Reference Lipton2014) argues that overreliance on this contrast to teach Christian spiritual lessons was at least partially responsible for increasing European antisemitism in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Christian relationships to Jews began to change, even with the German bishops that had been Jews’ earliest medieval protectors. Developments in canon law, politics, and individual rulers’ personal opinions and relationships with other political leaders (Cluse Reference Cluse2013) added pressure to reorder the relationship between Christians and Jews across continental Europe.

New developments in political philosophy pushed elites to recognize some Christian commonality and undertake moral responsibility for those they exercised power over (Cluse Reference Cluse, Burgard, Haverkamp and Mentgen1999; Isenmann Reference Isenmann2012: 523). By the thirteenth century, Christian holiness had become a main concern for kings. Theological discussions in Paris, long a center of theological and legal training, posed and probed questions of ethics of Christian rule. Graduates of the university dispersed across Europe, taking these debates with them (Cluse Reference Cluse, Burgard, Haverkamp and Mentgen1999). King Louis IX proclaimed himself “Rex Christianismus” (Most Christian King) and became Saint Louis for his reformatory efforts to build a just and holy France (Jordan Reference Jordan1989). Pressure for holiness came from below, too. Stow (Reference Stow1992: 285) argues that medieval rulers began to recognize that absolutism could not be maintained without a show of commitment to theocratic principles of Christian rule. Nirenberg (Reference Nirenberg1996) details how rural agitators victimized Jews and lepers in a 1320 crusade and 1321 revolt that pressured French King Philip V to prioritize the moral health of his domains, especially to reconsider fiscal policies that exacerbated poverty.

Christians began to demand more from each other (Hechter Reference Hechter1987), to expect a different standard of behavior and public comportment. Appeals for Catholic unity and reform and renewal of crusading provided support for public accountability for Christian behavior. The fourteenth century was a century of increasing Christian disarray: abuses of power and position within the Church, louder and louder criticism of the Church, war among secular and episcopal powers, and schism in 1378 between allegiance to a pope in Avignon versus a pope in Rome (Housley Reference Housley and Housley2017). Church fathers saw reconciliation and Christian unity as the path to reform, and in 1417 at the Council of Constance, they resolved to remain gathered until schism was resolved and reform instituted (ibid.: 48). This gathering ultimately failed to accomplish these goals and dissolved in 1418, but it established the obligation for religious and secular leaders to pursue reform and orthodoxy. Rulers were entreated by two papal bulls in 1420 to participate in crusading against the Hussite sect in Bohemia and against Turks in the eastern Mediterranean, and this quickly turned to questioning rulers regarding why they would leave to fight when they could attack heretics in their own jurisdictions (Rubin Reference Rubin1999). These new Christian ethics of lordship amounted to compliance demands for a ruler to govern other Christians as a Christian, to shepherd their subjects by legislating against un-Christian behavior, which would threaten Christian community holiness and health.

As best as we can tell, the 1424 expulsion in Cologne was not specifically attributable to these new Christian political ethics. However, city councilors from the Rat attempted to use its logic in a post-hoc justification written to King Sigismund of Germany, as yet uncrowned emperor, seven years later in 1431 (Wenninger Reference Wenninger1981). King Sigismund had written to the city for an account of why the Jews were expelled and insisted that the Jews be readmitted. The Rat members played on Cologne’s image as protector of the Christian faith (Rothkrug Reference Rothkrug1980) to evade blame for their actions. After making excuses for why they had not replied earlier, the letter authors offered that the Jews were expelled for causing religious unrest in the city: converting ignorant Christians to Judaism, being a liability for the city to protect from bloodthirsty anti-Hussite crusaders, lending money at interest despite a prohibition,Footnote 1 degrading the city’s reputation as one of the holiest places in Christendom and defiling it with their un-Christian feet, being rumored to be plotting to poison city wells, and more (Wenninger Reference Wenninger1981: 94–96). The letter writers reminded King Sigismund that they had been granted privileges from popes, emperors, and kings to do what they thought best for the city, in this case being the eviction of the “unbelieving” Jews. The city leaders argued on the grounds of their Christian religious responsibilities coupled with their governing responsibilities. They were justified because they had acted to protect the moral and political order of Cologne’s Christian community.

Consequences for Jews

The coevolution of territorial control and political theology fed conflict over political authority. Demands that a ruler change policies and institutions to be more Christian would not have made sense without territorialization. Territorialization spurred rulers and subjects to focus on the boundaries of their Christian community as the borders of authority. Rulers’ obligations were to the Christian subjects in their jurisdiction, and not to Christians outside their jurisdiction. As rulers’ governance came under inspection, medieval Christians reconsidered whether a holy Christian community could include Jewish residents. Jews represented God’s history of commitment to the pious faithful, but they were also representatives of unbelief and un-Christian living (Stacey Reference Stacey1992). Furthermore, agitators pointed out that Jews facilitated rulers’ un-Christian financial practices (Hsia Reference Hsia, Hsia and Lehmann1995). Whether their antisemitism was genuine or just a convenience, counterelites could use this ambiguity to their advantage (Kroneberg and Wimmer Reference Kroneberg and Wimmer2012) by pressing rulers to expel Jews to live up to their Christian responsibility. Jewish residence became relevant to intra-Christian political competition.

Urban Jewish communities were vulnerable to expulsion because of their legal position. Like most people in medieval Europe, Jews did not have legal rights to freedom of movement and settlement. The emperor formally held all rights to “protect” Jews (Judenregal), including designating which towns could accept Jews as residents and issuing communal and individual letters assuring safe passage. These rights were farmed out, mortgaged, and granted to territorial princes, cities, and bishoprics (Battenberg Reference Battenberg, Hsia and Lehmann1995; Ries Reference Ries, Hsia and Lehmann1995: 215). Authorities could choose which Jewish individuals or families to admit and to whom to grant residency permits (Toch Reference Toch2003), based on such characteristics as their wealth or trade connections, to facilitate economic exchange locally and abroad that could be taxed to fund the local ruler. In the high medieval period, authorities and Jews made contracts concerning residency, protection, Jewish community contributions to town defense, and acceptance as burghers (Cluse Reference Cluse, Gestrich, Raphael and Uerlings2009; Isenmann Reference Isenmann2012: 140). This classed Jews with other Päktburger, city residents under contracts, including merchants and gentry from other cities. City authorities could revoke residency contracts as it suited them.

Given the shifting religious and political economic pressures, we would expect that rulers everywhere in Ashkenaz began revoking residency privileges and expelling Jews. They did not. Despite the trends in Christian morality and territorialization, most rulers maintained Jewish coresidence. Broadly, rulers’ incentives were to maintain Jewish communities because they were easy targets for predatory fiscal policies. This function only increased in value as territorialization stepped up competition and warfare. As Johnson and Koyama (Reference Johnson and Koyama2019) outline, religiously justified differential treatment of Jews was a shortcut for rulers looking to shore up or expand their governments’ capacity.

Jewish communities were instrumentally valuable to rulers (Dorin Reference Dorin2015). In a sense, there was a market for Jewish presence in a city or territory, although Jews did not have much bargaining power over the conditions of their location. This market for Jews paralleled the market for merchants, whom urban elites tempted to relocate by tax breaks and rights to hereditary landownership (Haverkamp Reference Haverkamp1988: 177–78). Jews had higher literacy and education rates that better prepared them for financial professions, precipitating occupational shifts that were followed with legal restrictions limiting Jews’ involvement in nonfinancial occupations (Botticini and Eckstein Reference Botticini and Eckstein2005, Reference Botticini and Eckstein2012). Jews’ commercial activities provided money to a local economy, making transactions easier to accomplish, which in turn encouraged economic activity and more opportunities for a ruler to make, or take, money. Jewish merchant bankers also improved import and export flows, as their connections to other Jews in cities abroad diminished the costs and uncertainty in doing business in foreign locales. As Avner Greif (Greif Reference Greif1989, Reference Greif1993, Reference Greif1994, Reference Greif2008) has shown extensively, medieval Jewish trading networks were a reliable way to move money and goods (though his research concerned circum-Mediterranean trade rather than continental). Jews contributed to the commercialization of a city (Botticini Reference Botticini2000; Botticini and Eckstein Reference Botticini and Eckstein2012; Johnson and Koyama Reference Johnson and Koyama2017b), and commercialization meant more routine and liquid income collection for rulers. Within this fiscal landscape, Jews were vulnerable to rent-seeking governors (Finley and Koyama Reference Finley and Koyama2018; Koyama Reference Koyama2010). Their legal position, as essentially possessed by whomever held Judenregal, enabled rulers to practice confiscation and predation through taxation and forced loans. The immense financial value that rulers saw in Jews made expulsion a rare occurrence.

Competition over authority fueled both maintaining and expelling Jews. Fights over jurisdiction and supremacy could be funded in part by abusing Jewish communities, and these fights were also over control of Jewish communities. A third motivation was taking over local market power held by Jews, including the opportunity to lend to the government and profit from the interest and the political power that flows from other political elites being beholden to you (Ziwes Reference Ziwes, Haverkamp, Irsigler and Reichert1996). Johnson and Koyama (Reference Johnson and Koyama2019) give extensive attention to the role of anti-Jewish policies as a strategy for claiming legitimate authority. I look more deeply at the specific local power relations that precipitated expulsions. Emperors, landgraves, bishops, guilds, and town councils wrestled over determining the relevant authority in a patchwork landscape of overlapping jurisdictions (Stow Reference Stow1992). Expulsion was a tool to undercut rivals or assert one’s authority (Kedar Reference Kedar1996) if rivals stood between the ruler and a monopoly on authority. Finley and Koyama (Reference Finley and Koyama2018) produced an excellent study of how the macrolevel political competition in the Holy Roman Empire affected the persecution of Jews. But there was significant variation in local political and economic structures. The focus of this study is the association between expulsions and the potential for local authority contests. In short, I argue that Jewish communities were more likely to be expelled where authority was contested, and different local structures yielded more or less insecurity for Jewish communities.

One layer of competition occurred among political elites within a polity (see table 1). Characteristics of each title, office, or the constellation of claimants to authority could tip the balance of competition in favor of one body or another. In free and imperial cities and episcopal cities, where the bishop was installed by a cathedral chapter, the choice of governing officials might be subject to political maneuvering among elites with voting rights; a new official might be beholden to campaign promises or vulnerable to attacks by a faction within the city elite. Civic moral reforms and Jewish expulsions could be legitimizing and defensive. In cities ruled by religious authorities, these rulers might feel even stronger pressure to demonstrate their Christian ethics of lordship, lest they be criticized by a reforming civil servant with mutinous aspirations. Thus, despite strong instrumental incentives to maintain a local Jewish community, local political contestation may have incentivized expulsion.

Table 1. Relational structure of political competition and potential participants

If this were the case, then I expect a higher incidence of expulsion in cities where multiple authorities claim rights of rule. In some places, this might have manifested as multiple lords sharing dominion, directly by fragmented rights or fiefs or indirectly through mortgages of rights. In others, conflicting claims to rule might be between local political administrations, like a Rat or Schöffen, and the agents of another, like the Schultheißen, castellans, and Amtmänner that were agents of the overlord (Isenmann Reference Isenmann2012: 216). Relatedly, the conflict might have been between a city with local administrators and a resident overlord who might try to exert more absolutist, direct rule (Hechter Reference Hechter2013). Local contestation may have been higher where more revenue was at stake (Bueno de Mesquita and Bueno de Mesquita Reference Bueno de Mesquita and Bueno de Mesquita2018), and there was a greater prize to be won by pushing out rivals.

Another layer of competition was between the local government and external rivals, including neighboring cities or lords, peers, or even the Holy Roman Emperor. Jews were under the jurisdiction of the Roman crown, no matter what city or village they lived in; expulsions of Jews asserted a polity’s territorial independence, against the authority of the Holy Roman Emperor (Stow Reference Stow1992). Imperial cities, which were granted self-governance by the emperor (imperial immediacy), had ongoing conflict with the emperor and his agents about how much independence they really had. Expulsion would be especially likely in these cities, which had more opportunities for intracity strife on top of their struggles with the emperor. City rulers might expel Jews to spite any number of rivals, from the pope and the imperial regime (Haverkamp Reference Haverkamp, Burgard, Haverkamp and Mentgen1999) to local overlords to other cities.Footnote 2

In other circumstances, interruler warfare and politicking might stretch a ruler’s fiscal capacity to the point that expulsion and confiscation of Jewish assets outweighed any incentives to preserve Jews as insurance against future financial needs (Jordan Reference Jordan1998; generally, see Levi Reference Levi and Hechter1983, Reference Levi1988; Olson Reference Olson1993). Seizing the property of Jews was rewarding enough for France’s Philip II (Barkey and Katznelson Reference Barkey and Katznelson2011) that he did it twice. The Trier cathedral chapter estimated that expulsion there in 1418 generated 60,000 florins (and they wondered where their cut of the profits were) (Maimon et al. Reference Maimon, Breuer and Guggenheim1987–2003). Conflict might decrease the ruler’s discount rate on the value of Jewish residents, and the more desperate they were, the less it would matter how much the confiscation netted, as long as it was something. Since before the beginning of the millennium, German princes and families had been squabbling and warring over territory and succession (Haverkamp Reference Haverkamp1988). Alliances swapped with marriages, unexpected desertion, and negotiations over the office of emperor and inheritances. Cities and territorial rulers formed Bünde, alliances based on time-delimited pledges or treaties, to become blocs that enforced military peace, promoted trade, or bargained collectively with the emperor about noninterference—including with tax collection (Distler Reference Distler2006; Isenmann Reference Isenmann2012). A Bund marked a détente with other members. If the alliance brought stability and peace to a city, the government’s discount rate on the instrumental value of its Jewish community might rise again, preserving the community’s residence in the city.

With all these dynamics in mind, let’s return to the case of Cologne. In the early fifteenth century, the Cologne Jewish community had high instrumental value to both the city and the archbishop. Coerced loans to city coffers helped the city spread the costs of regional warfare into peacetime (Mann Reference Mann1986: 430) and stabilize city finances in the middle of a war-related economic downturn (Wenninger Reference Wenninger1981: 83–86). City rulers raised import and export taxes, depressing economic production of food staples for local consumption and revenues on shipping. The city extracted 22.3 percent of its direct loans 1414–24 from the Jewish community (ibid.: 92), a sizeable financial tool with which the city council would not have easily parted. At the same time, Archbishop Dietrich had attempted to fine both the Jews and the city to pay for his own war costs, but the Jews took him to court three times to contest his jurisdiction to do so. Under mediation by Duke Adolf of Jülich-Berg to end the 10-year feud between the city and the new Archbishop Dietrich, the parties reconsidered whether Jews’ rights of residence should be extended. The archbishop offered to remunerate the city for in return for expulsion. The agreement to expel the Jews resolved taxation and reparation disputes between city and the archbishop, helped each to meet their financial goals, allowed the city to avoid continued jurisdictional conflict with the archbishop over the Jews, and gave the impression that the archbishop was expressing his rights over the Jews by forcing them to be relocated from the city and into his other territories. The expulsion further allowed Archbishop Dietrich to save face after being called out by name in 1422 by Pope Martin V for fighting other Germans instead of participating in crusading against unbelievers (Housley Reference Housley and Housley2017: 59). Expulsion served the fiscal and political aims of the city of Cologne and the Archbishopric of Cologne.

Data and Method

Case studies can highlight the specific institutional contexts and political contests in individual cities and their connections to policies for Jewish residence. However, Jews lived in hundreds of German cities, and were expelled from more than 100, making overall comparison based on historical narrative alone cognitively difficult. Further, we have limited information for many German cities about Jewish communities or any contention about their residence. I use a quantitative approach to explore which structural conditions for political competition were more likely to produce expulsions, based on sparse information about each city rather than detailed histories.

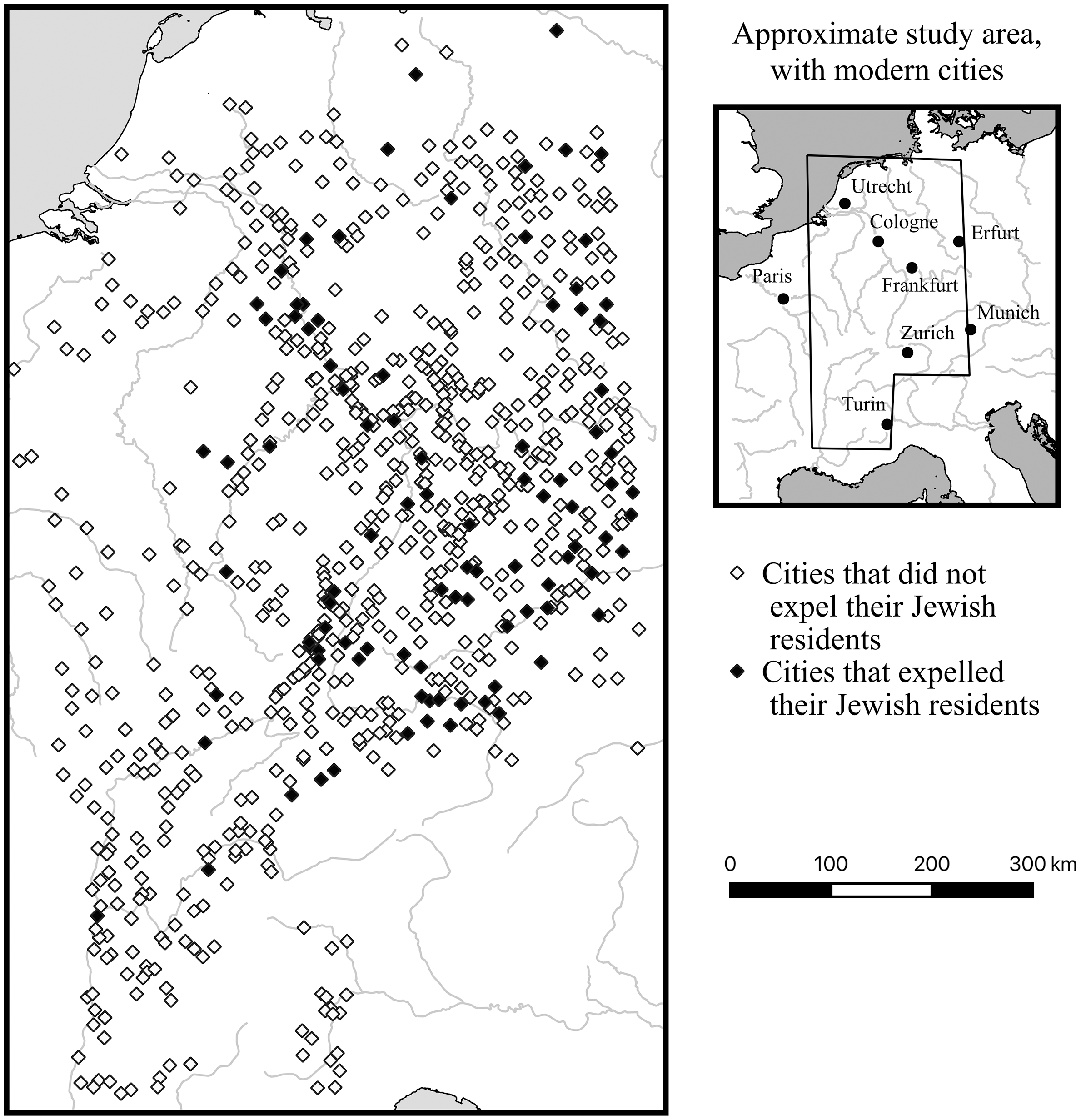

For city-level data on politics, economics, and Jewish communities, I translated and digitized Geschichte der Juden im Mittelalter von der Nordsee bis zu den Südalpen (Haverkamp Reference Haverkamp2002), a compendium covering cities with Jewish settlement roughly from the Meuse River in the west to the easternmost tributaries of the Rhine River and from the North Sea to the Southern Alps. This region was the heart of historic Ashkenaz, which stretched across parts of the modern countries of the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, France, Switzerland, Austria, and Italy (see figure 1 for a map).Footnote 3 The dataset is structured in the same manner as Geschichte der Juden, which is in century and half-century increments: 1000–1100, 1101–1200, 1201–50, 1251–1300, 1301–50, 1351–1400, 1401–50, 1451–1500, 1501–20. Organizing by city and by period is advantageous because many pieces of information about medieval cities are traceable to a period but fuzzy on the specific year.

Figure 1. Jewish settlement and expulsion in German lands, 1000–1520.

Besides recording the locations of Jewish settlement and expulsions, Geschichte der Juden encodes (1) the sovereign(s) and polity authority type (ecclesiastical, free or imperial, territorial lord or prince, or nonurban); (2) indicators of the development of Jewish community and ritual infrastructure (organized community, community leaders, official seal, cemetery, synagogue, mikveh, community center, hospital, Jewish quarter); (3) occurrence of persecutions, both period specific (e.g., Plague persecutions) and perennial (e.g., ritual murder accusations); (4) urban defensive, economic, and political development; and (5) lordly privileges over Jewish subjects.

Geschichte der Juden distinguishes between certain and uncertain Jewish presence in a city, based on the types of sources and corroboration between multiple sources. Additionally, the collection notes whether settlements were “nonurban,” meaning they did not develop into cities of much substance during the period. The database excludes cities with uncertain Jewish settlement as well as nonurban settlements. Most nonurban settlements have little additional information recorded besides Jewish presence; their small size likely means that there were few contemporary records about them and even fewer records that survived to the present. Nonurban locales were too small to have the institutional, economic, and political development under study here. The resulting dataset is an unbalanced panel that includes only as many cities in a period as had Jewish residents. Table 2 enumerates the temporal distribution of observations of the 811 cities in this study.Footnote 4 Descriptive statistics are presented in table 3.

Table 2. Jewish residential migration in German lands, 1000–1520 CE

Table 3. Descriptive statistics

Dependent Variable: Expulsion

For this study, the dependent variable is whether or not a local expulsion occurred. Geschichte der Juden catalogues years of confirmed, attempted, and uncertain expulsions on the local and territorial scale. I excluded attempted and uncertain expulsions, territorial expulsions, and expulsions with unknown dates.

Political Contestation

The argument in this study leaves open which specific institutions or authority competitions would be most dangerous for Jewish communities. We have limited theory and empirics in this regard. Recent work is most likely to investigate the development of representative institutions and to ask whether representation was advantageous to a polity’s economy (Stasavage Reference Stasavage2007, Reference Stasavage2016; Wahl Reference Wahl2019). Participatory institutions were but one facet of medieval urban political systems, just as in today’s cities and states. Therefore, this study includes both theoretically motivated measures and exploratory measures of political economies.

Sovereignty

To measure contestation over sovereignty within a city, I coded types of rulers, whether rule was shared, and whether rulership changed. From the timeline of sovereignty, I tallied and categorized rulers over a city within each period using binary, nonexclusive coding because multiple individuals or bodies might have claims over a city during a period, either at the same time or through a transfer of sovereignty. This method differs from the typical measurement (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Johnson and Koyama2017; Cantoni and Yuchtman Reference Cantoni and Yuchtman2014; Finley and Koyama Reference Finley and Koyama2018; Kim and Pfaff Reference Kim and Pfaff2012; Pfaff Reference Pfaff2013; Voigtländer and Voth Reference Voigtländer and Voth2012) that does not allow for overlapping categorizations, even though shared authority was not an anomaly. The possible ruler types were numerous: archbishop, bishop, religious house, religious foundation, imperial, free, king, prince, lord, minor nobility, city, and others (usually individual financiers who held mortgages over the city). Examining frequencies of cities and expulsion by ruler type helped to narrow the list of which ruler types to include, and I settled on including free, imperial, prince, bishop, and archbishop as dichotomous measures of who ever held sovereignty rights within the period. These cover the majority of observations and expulsions and represent a range of ranks among the nobility and clergy. Because these are binary, they indicate different types of authority and contrast different packages of incentives.

To distinguish between shared or sole sovereignty and capture any effects of direct competition over sovereignty, I use the mean count of sovereignty claimants per year in a period. Values near or equal to one indicate that sovereignty was rarely shared, or not at all during the period. High values (approximately 5 or 6) represent very fractured sovereignty rights. Moderate values (approximately 2 or 3) might represent frequent power sharing or a mix of years of sole sovereignty with years of highly fragmented sovereignty. Additionally, I noted whether the city was the residence of (one of) its sovereign(s) (1) or not (0).

Sovereignty transitions were an opportunity for political conflict. I coded types of transitions between sovereigns within a period. These transitions occurred through mortgages, sales, changes in feudal rights, treaties, conquests, deaths, marriages, and more. Because I am interested in political contestation, I include a count of political transitions, that is, those due to treaties or conquests. Additionally, I count the number of sovereignty transitions that occurred through mortgages of sovereignty rights. This is another method for understanding a ruler’s fiscal needs.

Political Institutions

To understand the potential role of individual political offices, I recorded the presence (1) or absence (0) of the following local political offices: castellan, civic jury (Schöffen), bailiff (Schultheiß), city chairman (Bürgermeister), and city council (Rat). Likewise, I recorded the presence (1) or absence (0) of two types of local administration rights: self-jurisdiction (Stadtrecht) and high jurisdiction, which was the right to try serious crimes and utilize the death penalty. These offices indicate the level of local involvement in political decision making. None is a direct substitute for the others.

Alliances

Regional political cooperation in Bünde created blocs of mutual aid. Assurances that a ruler could rely on troops furnished by others may have diminished the importance of Jews as a tax source. Membership in any alliances, such as the Swabian League, the Decapolis (Alsace), or the Rhenish League, was recorded by year from the detailed work of Distler (Reference Distler2006). I summed the count of regional alliance agreements for each city across all prior periods. The Hanseatic League, a trade-based alliance, is not considered in this measure.

Instrumental Value of Jewish Communities

Underlying my argument about political dynamics are the importance of commercial economic development and the potential for revenue collection in a city. I include measures of each of these, in line with previous economic arguments about the purely economic reasons for expulsion (Barzel Reference Barzel1992) or persecution (Becker and Pascali Reference Becker and Pascali2019).

Commercial Development

Maintaining a Jewish community for their instrumental value would be less important if a city had lively commercial activity outside of what was facilitated by Jewish merchants. Geschichte der Juden includes whether a city was known to have a market or market rights. I recoded the number and type of markets into an ordinal measure of market development: no markets (0), one market or a generic record of market rights (1), multiple markets (2), any number of fairs (3). The benefit of keeping the scale truncated in this manner, as compared to a count of markets or fairs, is that having outliers on number of markets or fairs is not helpful for the analysis, and often the reference is to plural markets rather than a specific number. As an indicator of commercial potential, I include a count of how many approximated medieval trade and pilgrimage routes (Bossak and Welford Reference Bossak, Welford, Kanaroglu, Eric Delmelle and Antonio Páez2015) pass within 5 kilometers of each city; this is constant across periods.

Substitutes for Expropriating from Jews

As I laid out, a significant deterrent to expelling Jews was the perception of how valuable it might be to maintain their presence for ongoing financial exploitation, or to confiscate everything from them at a future time of greater fiscal need. If a ruler had other options for confiscating from cultural others or formalized mechanisms for regular income, Jews would have less instrumental value. The Geschichte der Juden catalogue mentions when foreign merchant-bankers (Lombards or Cahorsins) were active in a city. I code this as presence (1) or absence (0) for foreign financiers. I used keywords to code the presence (1) or absence (0) of toll and tariff collection and minting. Keyword coding was validated manually and corrected, as necessary.

Other Independent Variables

Christian Religious Institutionalization

Historical religiosity is difficult to operationalize.Footnote 5 One tactic is to code for whether religion-based authority was institutionalized into city governance. While others have differentiated between cities hosting bishoprics versus not, it is more accurate to consider whether any rights to sovereignty in a city were held by a religious authority. I captured this through the sovereignty coding for bishop and archbishop mentioned above.

Additionally, I coded whether a city was the seat of a diocese (1) or not (0). Bishops and archbishops did not always possess sovereignty over the seats of their dioceses, and the previous measure would miss these cities with intense presence of clergy, religious orders, pilgrims, relics, and religious symbolism. This metric may be the closest to capturing public religious vitality with the information contained in Geschichte der Juden.

Jewish Community Infrastructure

Finley and Koyama (Reference Finley and Koyama2018) used the binary existences of synagogues, cemeteries, mikvehs, and Jewish quarters to represent community wealth.Footnote 6 I created a cumulative measure of community infrastructure by summing the presence of synagogues, cemeteries, mikvehs, and Jewish quarters, resulting in a range from 0 to 4. This index of community infrastructure reduces otherwise dichotomous variation into one dimension that separates cities with less-developed Jewish communities, which were likely smaller, from more developed communities, which were likely larger.

Other Persecutions and Pogroms

Jews in the Middle Ages faced a variety of persecutions, including Crusades massacres, ritual murder accusations, host desecration accusations, and extortion. To account for the effect of local histories of persecution, I record the total persecutions of any kind in the previous period and the total expulsions or attempted expulsions in the previous period.

Time

Period is recorded categorically in dummy variables, with the first period (1000–1100) as the referent category to draw contrasts between the earliest period and which later periods might have a higher risk of expulsion, as some experts give reason to expect (Müller Reference Müller and Haverkamp2002).

Analytical Approach

Because expulsions occurred in 5.6 percent of the sample (116 observations), and furthermore because so many of the independent variables are nonnormally distributed and/or dichotomous, the usual logistic regression approaches produce unreliable estimates for the relationships between expulsion and the independent variables. The computational problem for frequentist logistic regression is that sparseness—not all possible combinations are represented in the data, and many occur very few times—results in separation on the dependent variable. That is, there were no expulsions under some condition sets, and some condition sets are always associated with expulsions. Frequentist logistic regression calculations either overfit the model or, in my case, do not converge.

Instead, I implement Markov Chain Monte Carlo Bayesian logistic regression. Bayesian logistic regression solves the problem by considering that the sample data are drawn from distributions of the covariates; supplying these prior distributions supplements the sample data to give limited information about potential condition sets that are not represented in the sample. The results are posterior distributions of all observed variables, dependent and independent, conditional on the prior distributions and the observed distributions. The posterior distributions tell us how realistic our expectations are, given our observations.

I use weakly informative priors and scale all nondichotomous variables to be centered at 0 with a standard deviation of 0.5. To address the nonindependent nature of observations in this panel data, I use a hierarchical specification with observations pooled by city. The modeling procedure involves five independent chains of 5,000 iterations, including 2,500 warm-up iterations per chain. All chains converged and mixed well, and the potential scale reduction factor for each variable in the model is less than 1.01. Further information on model details, convergence, and posterior checks, including robustness to removing outliers, are included in the appendix.

Results

Expulsion was a relatively rare event, though not rare enough in terms of its human consequences. Expulsions were very uncommon before the fourteenth century; Geschichte der Juden noted only four urban expulsions prior to 1301 (Mainz 1012, Bingen 1198/1199, Lyon 1250, and Bern 1294). Excepting plague-related expulsions 1348–50, 16 expulsions were ordered before the fifteenth century. After this point, the frequency of expulsions increased dramatically, with the height of expulsions in the period from 1451 to 1500, during which 46 cities conducted 47 expulsions (see table 4).

Table 4. Jewish urban settlement and expulsions, 1000–1520 CE

For an initial look at political competition, we can check the probabilities of expulsion for different authority and institution conditions. Figure 2 compares rates of expulsions for those that had and did not have different types of authority structures or institutions. Without conditioning on any other variables, there is a high level of variation in whether the political structures correspond to differences in expulsion rates. Consistent with previous studies and with my arguments, the rate of expulsion was higher in free cities and imperial cities. Expulsions also happened more often in cities where rulers resided. For the different offices and local institutions, some had positive associations with expulsion, while others had negative associations. These comparisons do not attend to the panel structure of the data or the covariation of city conditions. Bayesian regression provides a more careful analysis.

Figure 2. Probabilities of expulsion under different local political conditions.

Because the results of logistic regressions are conditional on which variables are included, and the magnitudes of the effects are not comparable between different specifications (Breen et al. Reference Breen, Karlson and Holm2018), in table 5 I present the results of a single model that includes all the theorized and exploratory variables. Results from Bayesian regression analyses are slightly different from frequentist regression. The results describe the posterior distributions, which are the distributions of coefficients describing the relationships between independent variables and the dependent variable. Posterior medians are the median estimated coefficients of change in the log-odds of expulsion. Credibility intervals capture a specified proportion of the density of the posteriors, centered around the medians. Because the model was estimated using partially scaled data, as described in the preceding text, the posterior medians indicate the change in log-odds for the presence (= 1) of each binary variable and for the mean plus two standard errors for each continuous variable. Full results are in table A1 in the Appendix. For comparison, table A1 also includes results from two nested models: one with only control variables and a second with controls plus dominion categories and economic attributes. To aid interpretation, figure 3 visualizes a selection of effects translated into changes in probability of expulsion.

Table 5. Main results from Bayesian logistic regression

Note: Continuous variables (indicated by *) were scaled prior to estimation to the distribution mean = 0, sd = 2.5.

Figure 3. Marginal effects on the probability of expulsion for selected variables.

Note: The marginal effects are relative to the baseline p = 0.06. The posterior distributions are displayed with their medians surrounded by 50 percent and 90 percent credibility intervals. All continuous variables are scaled to (mean = 0, SD = 0.5).

Formal Sovereignty

A few conditions set up a balance of power that was more likely to victimize Jewish communities. Most other studies have used categorization of authority type as an indicator of political contestation. However, as I have established, authority was split much of the time, with cities having as many as six different rulers in a given year. To address this, I examined the mean count of sovereignty claimants per year in a period. I observe the opposite pattern of what I expected. More rulers competing for control was better for Jewish communities. A higher mean count of rulers per year was associated with a lower incidence of expulsion; the odds of expulsion decrease 52 percent (decrease of 0.74 in log-odds) for a shift in the mean count of rulers from 1.27 (mean) to 2.31 (two standard errors above the mean). Sixteen of 116 expulsions occurred when sovereignty was shared. Further, Jews were less safe in cities where rulers were in residence. This appears to indicate that more direct, less contested sovereignty increased the precarity of Jewish communities. The odds of expulsion in a city when the ruler lived there were 274 percent higher (log-odds increased by 1.32) than cities where the ruler(s) lived elsewhere.

The types of rulers mostly did not matter, but the relationship between a city’s rulers and other external powers did matter. Imperial cities were nearly 30 percent more likely to expel Jews (180 percent increase in odds, 28 of 116 expulsions). These were cities where the Holy Roman Emperor had some direct authority, setting the city up for conflict between local elites and the distant emperor. Likewise, geopolitics imperiled Jews. Cities where a transition of sovereignty happened politically, through treaty or conquest, were more likely to expel. One political sovereignty transition (about four standard errors above the mean of approximately 0) increases the log-odds by about 1.24, an increase of 246 percent in the odds of expulsion. The measurement strategies of this study are validated: More detailed measurement reveals that rulers’ holds on sovereignty mattered for the survival of Jewish communities.

Local Political Institutions

Beyond formal rights of sovereignty, what happened on the ground, in terms of the actual institutional maintenance of political and territorial control, led to differential outcomes for Jewish communities. Looking at local offices and self-administration, the odds of expulsion with Schöffen are 88 percent less than without; the odds with a castellan are 82 percent less than without. These two offices had the largest association, negative or positive, with whether a city expelled its Jews. Other local institutions (Schultheiß, Rat, Burgermeister) were not related to the expulsions. More detailed historical investigation is needed to understand the importance and nonimportance of each of these offices. Possession of Stadtrechte or high justice privileges also did not impact whether or not a Jewish community was expelled. Neither was a history of participation in regional alliances connected to expulsion, though I had reasoned that Bünde, by promoting geopolitical and economic security, would diminish the temptation to expel to confiscate. The posterior distributions for these no-relationship variables are consistent with zero effect.

Fiscal Opportunities

Turning to the financial side of sovereignty pressures, expulsion was more likely in cities where local rulers could manipulate their revenues using tools of absolutism. Rulers who had minting rights could simply coin more money if they needed cash. For cities that had mints, the odds of expulsion are 136 percent higher. Similarly to the fiscal position of Jews, city governors could up the tax rates on foreign moneylenders’ activities or extort them for the privilege to continue business without much interference because the foreigners did not have political power. For cities that had granted residency to foreign moneylenders, the odds are 270 percent higher. The presence of either could substitute for financial extraction from Jews and diminish the opportunity costs for expulsion. However, greater market development and trade-favorable location on roads had no relationship with expulsions, either to promote or suppress them. Commercial activity and access did not increase or decrease the instrumental value of Jewish communities. It was the structure of political control over fiscal resources that mattered for policy regarding Jews, not simply the fiscal potential of a city.

The Role of Christian Values

The exercise of Christian piety as reforming and purifying lordship expanded theocracy beyond bishops and archbishops to any ruler who embraced it. Purification expressed as persecution and exclusion of Jews granted Christian moral authority to any ruler. Indeed, rule by a bishop or archbishop had no relationship with expulsion; the special moral authority of belonging to the Church hierarchy did not provide special motivation to expel Jews. The seat of a diocese was also not more likely to expel Jews, even though the concentration of clergy and monastic life, pilgrims, and religious history could have made community purification more urgent and successful. It is striking that secular and clerical rulers were equally unlikely to expel Jews. Rather, expulsions became more common across all cities from the fifteenth century on, as the pressures for territorialization grew.

The link between Jewish community development and expulsion provides further support for my argument. City rulers were more likely to expel Jewish communities that built more community and ritual infrastructure. Visible non-Christian otherness may have been counter to moral authority in a Christian city, or it may have highlighted the opposing power of the emperor within a city’s own walls, or perhaps the rulers simply needed an influx of revenues from confiscation. Each of these mechanisms is consistent with the overall story that polity leaders were acting to consolidate territorial rule.

Discussion

The constellation of sovereignty was a factor in historical European antisemitic persecutions (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Johnson and Koyama2017; Barkey and Katznelson Reference Barkey and Katznelson2011; Finley and Koyama Reference Finley and Koyama2018; Jordan Reference Jordan1989, Reference Jordan1998; Katznelson Reference Katznelson, Katznelson and Weingast2005; Stacey Reference Stacey1988, Reference Stacey, Prestwich, Britnell and Frame1997) and religious change (Pfaff and Corcoran Reference Pfaff and Corcoran2012). This study replicates some of these findings. Further, it aims to capture the complexities and coexisting rights in urban spaces by including a wider range of political offices and institutions. The structure of political power clearly impacted the survival of Jewish communities. There is no straightforward story about which configurations of power were most damaging to Jews because roles and rights were so inconsistent. It was exactly this absence of formulas that made Jews vulnerable.

Dominion and sovereignty were not straightforward in medieval Europe, including in German lands. Sovereignty did not follow the hierarchical structure of many of today’s states; relationships between towns, princes, and the Holy Roman Emperor were case specific. The contrast between imperial cities and free cities highlights how the lack of a norm for city-emperor relationships harmed Jewish communities. These two types of cities had two different relationships to the emperor and territorial control. The absent emperor could, at any time, assert direct rule (Hechter Reference Hechter2013) over an imperial city and interfere with local goings-on, but free cities were relatively autonomous. The difference between these two approximates the difference between de jure and de facto autonomy. Jewish residency was less stable in imperial cities, where city autonomy was not formalized, where the city governors and the emperor had ongoing clashes over who was ultimately in charge.

Conflicting rights were a key source of medieval contention. The general argument of this article has been that political competition among Christians produced negative outcomes for Jews. However, instead of local political fragmentation leading to persecution, as Johnson and Koyama (Reference Johnson and Koyama2019) contend, Jews fared better where there were many rights-claimants.Footnote 7 Corulership might be due to complicated inheritance, mortgaging and pledging (short-term and long-term), treaties, or any combination of these, making it tough to characterize what sorts of cities were more likely to have shared rule. With more parties, the financial rewards to rule are divided ever smaller, and coordination on any policy is increasingly difficult, leaving little political incentive to expel. Further, more parties means it is less clear which Christians would benefit and which would lose. Here, the unsystematic nature of medieval German politics worked to preserve Jewish communities.

Power relationships vis-à-vis local institutions were similarly irregular. Jewish communities were more likely to be preserved where a castellan or college of Schöffen guarded civic peace. A castellan indicates an absentee sovereign who left an empowered agent to act in her or his name to govern castle affairs. This may have been a situation of stronger centralized control or lesser economic importance, both of which would be contexts of fewer rivals to political and economic power. Schöffen supplied a city government with legal capacity. Greater importance of law could be a conservative force for interreligious toleration because customary law was an alternative to religion-based rule (Johnson and Koyama Reference Johnson and Koyama2013, Reference Johnson and Koyama2019); new religious claims about purifying a city of un-Christian behavior, and the claims on political legitimacy made therewith, would be less likely to stick.

Territorialization, and dominion more broadly, required as regular and certain access to cash as a governor could manage. This study supports previous research indicating that rulers and cities had financial motivations for maintaining or expelling Jews (Barzel Reference Barzel1992; Katznelson Reference Katznelson, Katznelson and Weingast2005; Miethke Reference Miethke and Young2011; Veitch Reference Veitch1986). Commercialization provided financial opportunities, but only if the necessary bureaucracy and enforcement was in place. I did not find that general commercial development (Rubin Reference Rubin2014; Wahl Reference Wahl2016a) was related to policies of Jewish exclusion. Jews were expelled from cities where rulers could avoid bargaining with counterelites about new revenues and rates, where rulers had foreign moneylenders and minting as ready alternatives to exploiting Jews.Footnote 8 Captive resources, like Jews, or foreigners who needed permission for residency and business activity, or mints, would have been more reliably manipulated. Economic complementarity is a documented inhibitor of popular ethnic violence (Jha Reference Jha2013, Reference Jha2014; Landa Reference Landa2016), but here the violence was undertaken by the government. Rather than complementarity between Christians and Jews (Becker and Pascali Reference Becker and Pascali2019), the dynamics are of substitutability for exploitation toward the purposes of rulers.

In the midst of these political struggles, the new Christian theocratic responsibility for moral guardianship did amount to a new attempt at a formula for sovereignty. Religion-based claims can be powerful legitimation for rule (Johnson and Koyama Reference Johnson and Koyama2019; Rubin Reference Rubin2017). The motivating logic of purifying and protecting a city’s Christian community, whether convenient or truly felt, was equally available to Christian and lay rulers, an effect of the democratization of European Christianity (FitzGerald Reference FitzGerald2017). Laypeople were invigorating Christianity, joining monastic organizations as unvowed laborers, forming their own urban charitable communities, developing new saint cults (Pfaff Reference Pfaff2013; Rothkrug Reference Rothkrug1980), and building new parish churches from local donations and labor (Creasman Reference Creasman2002; Minty Reference Minty, Scribner and Johnson1996). These energies continued to the point of schism and prolonged warfare in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (Scribner Reference Scribner1991). In spite of new religious political ethics, though, preservation of Jewish communities was the default for Christian and secular rulers. Whatever religious motivations there were for expulsions, these motivations were never held so strongly that Jews were expelled everywhere.

Conclusion

This study is one more examination of European state-making in a rich social science tradition on the subject. Here, my focus is how managing social difference fit into medieval political development. I outlined how two long-run processes—territorialization and changes in political theology—created insecurity for Jewish communities. The argument and empirical focus of this article is that these long-run processes did not have consistent effects on the position of Jewish communities but were contingent on local political economies. Johnson and Koyama (Reference Johnson and Koyama2019) describe how the changing value placed on religious legitimacy promoted antisemitic violence. With rather large city-by-city variation in sovereignty rights and political organization, though, we should be more attentive to what it was about different local governments that brought the need for religious legitimacy or capacity building to the fore. That is what this study offers: Exploration of how specific local structures mattered for the security of Jewish communities.

Each local institution and privilege does not align with a particular political regime or position within German lands; each of them provides independent information about the political and economic incentives and opportunities for rulers. Disaggregating city political and economic institutions (Wahl Reference Wahl2016b, Reference Wahl2019) reveals relationships to Jewish community survival that would be obscured by focusing on autonomy (Stasavage Reference Stasavage2014) or regime structures (Blank et al. Reference Blank, Dincecco and Zhukov2017) alone. Essentially, though, explanations relying on sovereignty types and autonomy describe political competition as endogenous to political institutions. By investigating which specific structures mattered in this case, I provide impetus for reexamination of other phenomena tied to premodern European political competition. As Liddy (Reference Liddy2017) recently detailed about fifteenth-century England, even seemingly autocratic systems can have intense political conflict within and between layers of government, down to individual cities. Contestation happens at lower levels of political systems, too, not just at the highest levels.

When looking at expulsions from cities, or any other case of state violence against minority groups, we need to keep in mind the whole spectrum of the political order. Competition over power and resources between factions of any type (Clark Reference Clark1998; Gill and Keshavarzian Reference Gill and Keshavarzian1999; Lachmann Reference Lachmann1989) can affect the content and salience of an ethnic boundary (Hechter Reference Hechter1987; Stewart Reference Stewart2018; Wimmer Reference Wimmer2013). In the case of the medieval Holy Roman Empire, the political system bred uncertainty about governance rights, which in turn fed struggles among Christian elites. Some of these resorted to persecuting Jewish communities by expelling Jews from their cities to bolster claims to sovereignty and mitigate financial problems. They used ethnic cleansing of Jews support their positions and possessions.

Acknowledgments

I thank the following for comments during the development of this paper: Michael Hechter, Steve Pfaff, Edgar Kiser, Robert Stacey, Jared Rubin, Christian Ochsner, Michelle O’Brien, and especially Alfred Haverkamp, Christoph Cluse, Stephan Laux, Jörg Müller, Jörn Christophersen, and others from the Arye Maimon Institute for Jewish History, as well as the Deutsche Akademischer Austauschdienst, which provided a Short Term Study Grant to be a visiting student at the AMIGJ. Two anonymous reviewers, Mark Koyama, Jeffrey Kopstein, Chad Alan Goldberg, and Annegret Oehme generously provided encouragement and helpful insights. Additionally, thanks are due to Chris Adolph, Lindsey Beach, Charles Lanfear, participants in Steve Pfaff’s working group at the University of Washington Department of Sociology, participants from the 2017 Institute for the Study of Religion, Economics, and Society Graduate Workshop, and roundtables and presentation sessions at the annual meetings of the American Sociological Association (2015, 2018), the Social Science History Association (2017), and the Association for the Study of Religion, Economics, and Culture (2019). Remaining errors are most certainly my own.

Appendix

Details of Bayesian Logistic Regression

In this study, Bayesian generalized linear mixed models provide advantages over frequentist linear models. Bayesian models are joint probability models for all variables. Incorporating prior distributions into the estimation builds in some variability that may not be represented in the specific observations in a sample. Ultimately, this produces results based on more information than traditional regression. In this case, the results are more precise and reliable. To specify and estimate the hierarchical Markov Chain Monte Carlo Bayesian logistic regression model, I use the rstanarm package 2.13.1 (Stan Development Team 2018a) in R. Following the advice of the Stan Development Team (2018b), Gelman et al. (Reference Gelman, Jakulin, Pittau and Su2008), and Betancourt (Reference Betancourt2017), I use weakly informative priors, the Student’s t distribution (df = 7, scale = 2.5). All five chains converged and mixed well. For converged models, the potential scale reduction factor for each variable in the model should be is less than 1.05, and the values for this model are all less than 1.01. Full results for posterior distributions are in table A1, with model details and convergence information in tables A2 and A3. Pareto-smoothed importance sampling leave-one-out cross-validation (PSIS-LOO) and period-stratified exact K-fold validation, implemented through the loo package for R (Vehtari et al. Reference Vehtari, Gelman and Gabry2017, Reference Vehtari, Gabry, Yao and Gelman2018), confirms that the posterior distributions are stable to iterative omissions of observations and reestimation (all Pareto k < 0.7).

Table A1. Results from Bayesian logistic regression

Note: Continuous variables were scaled prior to estimation to the distribution mean = 0, sd = 2.5.

Table A2. Model statistics: Step size and divergence

Table A3. Model statistics: Effective sample sizes