Introduction

In the last decade, a cottage industry of comparative methodology has developed in the social sciences (e.g., Brady and Collier Reference Brady and Collier2004; George and Bennett Reference George and Bennett2005; Gerring Reference Gerring2007; Goertz and Mahoney Reference Goertz and Mahoney2012; Mahoney and Rueschemeyer Reference Mahoney and Rueschemeyer2003; Ragin Reference Ragin2008). Burgeoning methodological discourse owes much to positivist critiques of the 1990s, particularly the heavily debated Designing Social Inquiry by King et al. (Reference King, Keohane and Verba1994; see also Geddes Reference Geddes1990, Reference Geddes2003; Goldthorpe Reference Goldthorpe1991; Kiser and Hechter Reference Kiser and Hechter1991; Lieberson Reference Lieberson1991). Yet the formalization of comparative methodology preceded these critiques, with each decade seeing its own innovators and cataloguers (see Eckstein Reference Eckstein, Greenstein and Polsby1975; Lijphart Reference Lijphart1971, Reference Lijphart1975; Ragin Reference Ragin1989; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1984; Skocpol and Somers Reference Skocpol and Somers1980; Stinchcombe Reference Stinchcombe1978). With such a long tradition of articulation, it is easy to assume that comparative methodology is a completely institutionalized form of analysis. In fact, this is exactly what some comparativists argue (Bennett and Elman Reference Bennett and Elman2007; Goodwin and Horowitz Reference Goodwin and Horowitz2002; Mahoney Reference Mahoney2007; Rihoux et al. Reference Rihoux, Álamos-Concha, Bol, Marx and Rezsöhazy2013; Slater and Ziblatt Reference Slater and Ziblatt2013).

There is a simple problem with such an account, however. Methodological discourse around comparative case studies has relied on either the appraisal of a few exemplar studies or the articulation of possible methodological strategies, rather than considering the typical practices of scholars who use comparison (Goertz and Mahoney Reference Goertz and Mahoney2012; Mahoney Reference Mahoney2004; Munck and Snyder Reference Munck and Snyder2007). Exemplars may be outliers and possibilities may not reflect actualities. To address the shortcoming, this study provides detailed evidence as to what the comparative method in practice is, and assesses whether it has institutionalized within the social sciences.

I draw a distinction here between formalization, which is the discourse and articulation by methodologists of how a method should be practiced, and institutionalization, which occurs when typical practice by researchers and the discourse of methodologists are relatively congruent. An institutionalized methodology is one, quite simply, where shared standards predominate. Shared standards require the occurrence of three processes: increasing methodological awareness by scholars of the strategies they use; methodological consensus within a field about what the practice of a method is; and general convergence on a set of methodological strategies. In this fashion, institutionalization is a bidirectional process between methodological practice and discourse, where practitioners learn from methodologists and methodologists learn from practitioners.

To assess the dynamics of institutionalization, evidence of the typical practice of comparative methods is required. Previous work on typical practice has relied on limited samples of the field (Munck and Snyder Reference Munck and Snyder2007) or implicit assessment of comparative work (Goertz and Mahoney Reference Goertz and Mahoney2012). In contrast, this study employs population data. I examine all comparative case studies of revolution published from 1970 to 2009. The study of revolution is not only a predominantly comparative field (Goldstone Reference Goldstone, Mahoney and Rueschemeyer2003), it is also, in no small part, an instigator of sophistication in comparative analysis (e.g., Moore Reference Moore1966; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1979). Through content analysis, I analyze the justifications given by scholars for the selection of their cases. While case selection is only one aspect of comparative methodology, it has tended to be a site of critique and defense of comparison and is “arguably the most difficult step in developing a case study research design” (George and Bennett Reference George and Bennett2005: 234). Given the relatively limited menu of case selection techniques (see Gerring Reference Gerring2007), it is also the aspect of comparative methodology most likely to reveal shared standards. The results of analysis show only modest evidence of increasing methodological awareness, a general lack of consensus as to best practices, and limited convergence on standards. This suggests that institutionalization has not yet occurred in the practice of comparative methodology.

In the next section, I briefly describe how comparative methodology and the study of revolution have developed since the 1960s and detail the possibilities of methodological institutionalization in case selection. Next, I explain the methods of data collection and content analysis. I then present the results of analyses that show the diversity of methods overall and limited awareness, consensus, and convergence over time. I conclude that a gap remains between how comparative methodologists formalize their tools and how practitioners use them. This suggests that continued debates about comparative methods may be less about cultures within the methodological divide (Goertz and Mahoney Reference Goertz and Mahoney2012), and more about the challenges of institutionalization. The results also indicate that case selection practices in the study of revolution have centered attention on some aspects of the phenomenon to the possible detriment of others.

Comparative Analysis and the Social Science of Revolution

Comparative methods in the social sciences underwent a revival in the mid-twentieth century as early practitioners sought to infuse their disciplines with a historical imagination and grounding (e.g., Moore Reference Moore1966). Early attempts at formalization of comparative case methods date from this time, and remain influential (e.g., Eckstein Reference Eckstein, Greenstein and Polsby1975; Lijphart Reference Lijphart1971, Reference Lijphart1975). By 1979, when Skocpol published States and Social Revolutions (1979), the revival was in full swing with researchers rediscovering the comparative methods of classical scholars like John Stuart Mill, Max Weber, and even Emile Durkheim (Ragin and Zaret Reference Ragin and Zaret1983). The enthusiastic reception of Skocpol's work drew attention to the possibilities of careful case comparisons. The 1980s accordingly saw the development of new comparative methods, such as qualitative comparative analysis (Ragin Reference Ragin1989), and increasing use of them within multiple subfields. As a further sign of maturation, critiques of the methods grew, reaching a high point in the early 1990s (e.g., Geddes Reference Geddes1990; Goldthorpe Reference Goldthorpe1991; King et al. Reference King, Keohane and Verba1994; Kiser and Hechter Reference Kiser and Hechter1991; Lieberson Reference Lieberson1991). The sharp criticisms engendered a wave of responses from comparativists, which have done much to articulate and formalize the methodology (e.g., Brady and Collier Reference Brady and Collier2004; George and Bennett Reference George and Bennett2005; Gerring Reference Gerring2007; Goertz and Mahoney Reference Goertz and Mahoney2012; Mahoney and Rueschemeyer Reference Mahoney and Rueschemeyer2003; Ragin Reference Ragin2008). As a result, comparative methodologists have claimed victory of a sort, arguing that their methods have increased in rigor and are a standard option for researchers across the social sciences (Bennett and Elman Reference Bennett and Elman2007; Mahoney Reference Mahoney2007; Rihoux et al. Reference Rihoux, Álamos-Concha, Bol, Marx and Rezsöhazy2013; Slater and Ziblatt Reference Slater and Ziblatt2013).

Studies of revolution have been intimately connected to the development of comparative analysis in the social sciences. In the mid-twentieth century, historical social scientists of revolution helped pioneer the modern use of case studies (e.g., Tilly Reference Tilly1964; Wolf Reference Wolf1969), and in the 1970s and 1980s scholars of revolution became proponents of its formalization (e.g., Skocpol Reference Skocpol1984; Skocpol and Somers Reference Skocpol and Somers1980). More recently, comparative studies of revolution have served as expressions of the method's maturation (e.g., Foran Reference Foran2005; Goldstone Reference Goldstone1991; Goodwin Reference Goodwin2001). While other fields, such as state building, democratization, development, and the emergence of capitalism, have contributed to the development of comparative methodology, revolution remains singular for its reliance on the case comparison. As Goldstone (Reference Goldstone, Mahoney and Rueschemeyer2003: 41) notes, “[I]t is striking that those works on the subject of revolutions that have had lasting influence have been almost exclusively built around comparative case studies.” This makes the subfield of revolution not only a fertile place to examine the practice of comparative methodology, but an important one.

This study examines the question of whether the articulation of comparative methodology has led to institutionalization within its practice. An institutionalized methodology means standardization. The possible uses, and misuses, of a method are well known, principles are generally shared, and it is widely accepted as a legitimate tool of analysis. An institutionalized methodology thus has, at its root, methodological awareness (Goodwin and Horowitz Reference Goodwin and Horowitz2002). Practitioners know what they are up to, and do not need to explain it at length as their audience, too, knows the general contours of a method. To be methodologically aware also requires some consensus among researchers and methodologists as to a method's best practice. With consensus, standards develop and become widely shared, creating the basis for methodological legitimacy. Together awareness and consensus should create convergence in a method's practice, toward standard ways of articulating and using a methodology. Once convergence has occurred, we may speak of an institutionalized method—one that is known, standardized, and accepted.

Institutionalized methods thus have four features. First, over time scholars will become more explicit about their methods but, second, need to explain them less as the audience is familiar with the methods. Third, as consensus develops and convergence occurs, an institutionalized method will coalesce around shared practices. Thus, finally, the diversity of methods practiced should decline over time.

Comparativists argue that such processes have occurred within their method (Bennett and Elman Reference Bennett and Elman2007; Goodwin and Horowitz Reference Goodwin and Horowitz2002; Mahoney and Rueschemeyer Reference Mahoney and Rueschemeyer2003). What is striking about this claim is that comparative methodology's proponents have relied primarily on consideration of just a handful of exemplar studies, and best practices may diverge substantially from typical practices (Mahoney Reference Mahoney2004; Munck and Snyder Reference Munck and Snyder2007). This issue is not unique to the comparativists. So, too, do their critics rely on considering just a few famous studies. To take just one example, Geddes (Reference Geddes1990, Reference Geddes2003) critiques Skocpol's (Reference Skocpol1979) choice of cases in States and Social Revolutions and what that may mean for her findings, as do Kiser and Hechter (Reference Kiser and Hechter1991), Lieberson (Reference Lieberson1991), and King et al. (Reference King, Keohane and Verba1994). In defense, Mahoney in a series of papers (Collier and Mahoney Reference Collier and Mahoney1996; Mahoney Reference Mahoney1999, Reference Mahoney2000; Mahoney and Goertz Reference Mahoney and Goertz2004), Ragin (Reference Ragin1989), Goldstone (Reference Goldstone, Mahoney and Rueschemeyer2003), and Munck (Reference Munck, Brady and Collier2004) invoke States and Social Revolutions as an example of methodological sophistication. But we have no way of knowing whether Skocpol's analysis, for good or ill, is representative of comparative methodology as it is largely practiced. Work that seeks to formalize comparative methods has a related problem—the possible practices of the field may not be its typical practices (Goertz and Mahoney Reference Goertz and Mahoney2012: 8).

In short, evidence of what practitioners do is needed. I thus examine how comparative methods are practiced within an entire subfield—the study of revolution since 1970. By doing so, typical practice can be documented and whether comparative methodology has institutionalized can be seen. Examining an entire subfield is quite the undertaking, so I focus on methods of case selection in particular for three reasons. First, as seen in the preceding text, case selection has historically been the site of many critiques of comparative studies. Second, case selection is the crucial ingredient in comparison, as well-chosen cases allow for causal inferences to be made (Collier et al. Reference Collier, Brady, Seawright, Brady and Collier2004) and is the first step in comparative study design (George and Bennett Reference George and Bennett2005). Third, case selection is the area of comparative methodology most likely to see standardization in its practice over time as it is a long recognized issue within the field (Eckstein Reference Eckstein, Greenstein and Polsby1975; Lijphart Reference Lijphart1971). In short, case selection is thus the area of comparative methodology most likely to see the development of awareness, consensus, and convergence that would be expected to occur with institutionalization.

In the next section, I detail how comparative case studies of revolution were identified and their methods of case selection analyzed.

Data on Case Selection in Comparative Studies of Revolution

Identifying Comparative Case Studies

The studies for content analysis come from an ongoing investigation of comparative methods and the social science of revolution. All social scientific comparative case studies of revolution published between 1970 and 2009 are identified by searching for peer-reviewed articles and books published in English listed in three central social science databases (Sociological Abstracts, Worldwide Political Science Abstracts, and PAIS International) and one general database (Books in Print) using subject headings with wildcard variants of the keyword revolution. This method yields 6,621 entries from 1970 to 2009 (though in the case of Books in Print not necessarily unique works as reprints are counted, as well). In addition, the results are verified using two annotated bibliographies to check for missing studies—Goodwin's (Reference Goodwin2001) appendix and Tilly's personal bibliography made public by Christian Davenport after his passing in 2008.Footnote 1

From these lists, comparative case studies are identified for inclusion using two criteria. First, the study must examine at least two or more cases (whether actual events or negative cases), per the author's own treatment of what constitutes a case. Second, the strategy of analysis must be comparative, again relying on the author's own assessment of their methodology. In the absence of explicit claims of comparative method (which occurs in a notable minority of studies), two or more cases that are given roughly equal treatment are considered comparative. General surveys, theoretical treatises, and other works with nonempirical goals are excluded.Footnote 2 This method of identification yields a population of 148 comparative case studies—50 books and 98 articles and chapters in edited collections.

Methods of Content Analysis of Case Selection

Each of the comparative case studies of revolution is examined to identify explicit statements about case selection. Notably, most studies provide no explicit justification for the cases they examine, a point returned to in more depth later. Methodological excurses commonly occur in the introduction or preface of a study, though some authors begin with a lengthier theoretical discussion and place empirical justifications much deeper in the text. Interestingly, books often include two separate methodological statements—a preface tending toward an intellectual autobiography of how the study's design was arrived at and an introduction with a more formal explication. For the purposes of content analysis, both narratives are treated as valid. Once methodological statements are identified, they are categorized in a grounded fashion—using top-down distinctions in case selection drawn from the comparative methodology literature as well as bottom-up categorization of recurrent strategies. This allows for both methodological discourse and typical practice to be assessed. The categorizations are not mutually exclusive; that is, a study could use numerous strategies of case selection. Case selection strategies that have the same logic are grouped together. For instance, a “prototypical” case and “exemplar” case are coded as similar strategies. The coding yields 18 distinct strategies of case selection, which can be grouped into five general types of selection methods. The methods and exemplar statements for each are presented in table 1 and described in the following text.

TABLE 1. Examples of Methodological Statements about Case Selection in the Study of Revolution

The first general type of selection method that emerges is that of strategies which compare cases that are mostly similar on some dimension. Many scholars seek to analyze events that bear a family or type resemblance (see Collier and Mahon Reference Collier and Mahon1993). This is most famously practiced by Skocpol (Reference Skocpol1979: 41), who considered the social revolutions of France, Russia, and China so similar that it was “more than sufficient to warrant their treatment together as one pattern calling for a coherent causal explanation.” Also popular is the strategy of controlling for exogenous environments of time or place (see Slater and Ziblatt Reference Slater and Ziblatt2013). For example, Goldstone (Reference Goldstone1991) examines cases of state breakdown in the early modern era, and Goodwin (Reference Goodwin and Boswell1989: 61–62) emphasizes that “[a] regional approach allows one to ‘control’ for a variety of factors that one might otherwise mistake as causally significant.”

A second type of strategy is to provide variation among cases rather than similarity, what we might call least similar cases (see George and Bennett Reference George and Bennett2005; Gerring Reference Gerring2007). Variation could come on the independent or the dependent variable side of a theory or even both as in Walton's (Reference Walton1984) study of revolution and economic development. Or variation could be sought for particular methods such as qualitative comparative analysis (see Ragin Reference Ragin2008) or to provide generalizability across time and space. For instance, Foran (Reference Foran2005: 5–6) uses qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) to examine outcomes in “a wide variety of Third World Revolutions,” and Goodwin (Reference Goodwin2001: 5) explicitly considers cases “in three vastly different peripheral world regions.” Other researchers include negative or counterfactual cases to allow for causal inference (see Fearon Reference Fearon1991; Mahoney and Goertz Reference Mahoney and Goertz2004), as Dix (Reference Dix1984) does in his landmark study of the success or failure of revolutionary mobilizations. Similarly, some scholars look for natural experiments in which initially similar cases diverge due to a particular cause or mechanism. For instance, Paige (Reference Paige1990: 38) argues that the array of regime types in Central American countries “present us with a fortuitous natural experiment.” Finally, in a rare example of structured sampling, Russell (Reference Russell1974: 71) identifies 160 possible cases of rebellion within his scope conditions, and then draws two random samples from the 28 cases that fit his definitional criteria. In these strategies, cases are selected to provide generalizability or causal inference.

Other selection methods rely on the attributes of a case in particular (see Gerring Reference Gerring2007). Here, the historical importance of an event is a possible selection criteria, as Dunn (Reference Dunn1972: x) notes in his early, influential study: “[N]o interpretation of the meaning of modern revolutionary phenomena could afford to ignore them.” Other cases can be put forward as paradigmatic, and serve as prototypes to which others should be compared. Ellis (Reference Ellis1973) proposes that the role of armies in the Chinese Revolution is an important touchstone to which to compare events as diverse as the English Civil War, the Paris Commune, the Russian Revolution, and the Prussian Reform Movement. A third strategy is that of the crucial case. Methodologists have long noted that certain cases might be most likely to show the veracity of a theory (see Eckstein Reference Eckstein, Greenstein and Polsby1975; Gerring Reference Gerring2007). For instance, Conge (Reference Conge1996) argues that his cases are a crucial test for his model of revolution.

While generally not recommended (see George and Bennett Reference George and Bennett2005), cases are also selected for pragmatic reasons. Some prefer to engage in comparisons that are relatively understudied as Eckstein (Reference Eckstein1985: 473) does when she justifies the examination of Cuba and Bolivia in part because “[n]o such comparative analysis has ever been done.” Other scholars follow their interests or the availability of data. For instance, Hodgkin (Reference Hodgkin1976: 111) states that his comparison of Vietnam and West Africa is drawn because they are “two specific regions which I know something about.” Finally, others prefer to study recent events, as Liu (Reference Liu1988: 180) does in comparing Solidarity in Poland to the Islamic Revolution in Iran.

Finally, a few selection methods that occur in practice do not fit easily into the four other general types of strategies. Scholars might choose cases because of their definitional or conceptual fit as Russell (Reference Russell1974) and Moghadam (Reference Moghadam1995) do. Cases can also be chosen because of their independence from one another (see Lijphart Reference Lijphart1971), which Kautsky (Reference Kautsky1975) uses in his comparative examination of Mexico and the Soviet Union. Finally, reexamination of prior comparisons, while rare, is possible. O'Kane (Reference O'Kane1995: 2) consciously revisits Skocpol's (Reference Skocpol1979) analysis of France, Russia, and China: “These three cases are chosen in order to develop a direct challenge to Skocpol's claims about state building.”

Overall, the grounded content analysis reveals a wide diversity in case selection methods, which is enumerated in the next section.

The Diversity of Comparative Methods

What is first apparent from the content analysis is the diversity of case selection methods that are used, especially when compared to the discourse of methodologists. For example, George and Bennett (Reference George and Bennett2005: 83) explicitly recommend five different methods of case selection and Gerring (Reference Gerring2007: 89–90) identifies nine different strategies. In actual practice, comparative revolutions scholars do not use all these—at least in their rhetorical justifications—leaving aside George and Bennett's least likely and deviant cases, and Gerring's extreme, deviant, influential, and pathway cases. The disconnect between discourse and practice is even more striking when considering the popularity of case selection methods, presented in table 2.

TABLE 2. Case selection methods in the study of revolution, 1970–2009

As noted previously, only a plurality of the 148 studies examined—65—include explicit statements about case selection. Among these explicit studies, most scholars choose more than one method, totaling 188 strategies for an average of 2.9 methods per study (SD = 1.3, min = 1, max = 9). Sixty-three percent of explicit studies employ two or three different selection strategies. The most popular approach is to choose cases that are mostly similar along some dimension. Family resemblance appears in 32 different studies, and controlling for time period in 25 studies. Least similar cases are also widespread, with 21 different studies using a strategy of obtaining variation on the dependent and/or independent variable. The third most popular strategies are selecting cases from the same region or historically important events. More than 30 percent of studies with explicit statements include pragmatic justifications in their case selection, such as researcher interest or the availability of data. In short, the comparative method in practice does not appear to closely follow the categorizations or recommendations of comparative methodologists. And nor do methodologists seem to recognize the diversity of methods used by practitioners.

As case selection methods are not mutually exclusive—one study could use several different methods—I examine which strategies tend to occur together. Table 3 presents the statistically significant correlations between two methods appearing in a single study. All but one of these correlations is positive. Only selection for variation on variables or selection from typology/qualitative comparative analysis are inversely related; perhaps because, even though the logic is similar in both, one tends to supplant the other in language. The strongest correlation is between varying region and/or time and data availability/researcher interest. In general, selection due to an event's historical importance correlates with the greatest number of other methods. Another way of examining conjoint use is by conceptualizing it as a network. Figure 1 presents the network of co-occurrence of selection strategies in a study, where the method is a node and co-occurrence is a tie. As is immediately obvious, the core of multiple methods is strategies of most similar cases, either due to family resemblance, region, or time period, with methods of variation also somewhat central. Other selection methods tend to be peripheral to conjoint strategies.

TABLE 3. Statistically significant correlations among case selection methods

Note: Correlations are analyzed among studies with explicit case selection methods only. Correlations not listed are statistically insignificant. Full results available from the author upon request.

* p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001

FIGURE 1. Co-occurrence of case selection methods in studies of revolutions.

Overall, consideration of which methods have been used reveals a substantial difference between actual practice and recommended practices over the last four decades, and shows that researchers tend to prefer most similar or least similar cases. But this description by itself does not answer whether comparative methods have institutionalized in their practice. Perhaps, for instance, the plurality of studies that prefer pragmatic concerns to ones of causal inference are older as methodological awareness, consensus, and convergence has developed over time. Examining trends in the use of methods is the task of the next section.

Case Selection in Practice, 1970–2009

As argued previously, institutionalization of a methodology within a field means the development of shared standards for its practice. Shared standards in turn require methodological awareness by scholars that the method is being used and consensus as to how it should and should not be used, and these, in turn, will produce convergence in methodological practice. In short, if comparative methods have institutionalized, then over time we should see increasing levels of explicitness in methodological statements with decreasing amounts of necessary explication (awareness plus consensus). Further, less desirable practices should decrease over time while best practices increase and as a result the diversity in methodological practice will be reduced (consensus plus convergence). This section analyzes the evidence for each of these propositions in turn.

Methodological Awareness and Consensus

Methodological awareness seems like a simple thing. It is when a practitioner of a method knows that they are using a method. But it also requires methodological sophistication—knowledge of a method and knowing why it is preferable to another in any given situation. In other words, methodological awareness involves understanding a menu of methodological options, and the ability to choose amongst them consciously. Thus, a methodologically aware study will be explicit about its methodological choices, and as a method is institutionalized, explicitness will increase over time. To examine this trend, a scatterplot of the proportion of studies with explicit statements about how and why cases are selected over time is presented in figure 2.

FIGURE 2. Proportion of studies with explicit case selection methods by publication year, N = 148.

As previously noted, most comparative studies do not include any clear methods of case selection. Ironically, the trend over time is for fewer studies to explicitly discuss selection strategies. In the 1970s, an average of 50 percent of studies published discussed how they chose their cases. By the 2000s, less than 40 percent did so. While the correlation of year published and proportion of explicit studies is not statistically significant, it does trend in a negative direction as indicated by the trend line in figure 2. This suggests that comparative studies of revolution have become less methodologically aware, at least rhetorically, in their case selection over time. This is not what would be expected of an institutionalized methodology.

Methodological awareness, however, accompanied by a degree of consensus over a methodology's use would lead to declining exposition as the method is well known, well established, and uncontroversial. In this view, an institutionalized methodology, while acknowledged, would need less explanation. To assess this dynamic, I count the number of words in descriptions of case selection methods, separating articles from books as length constraints create a false equivalency. On average, articles have case selection statements 88 words long and books have statements 151 words long. Scatterplots of the trends over time are presented in figure 3.

FIGURE 3. Number of words in case selection statements by publication year, N = 65.

As indicated by the trend lines in figure 3, there is a clear reduction in the length of case selection statements over time. The correlation between year and number of words is statistically significant: for articles β = −.41, p < .05; for books β = −.38, p < .05; for both β = −.37, p < .01. However, there are clear outliers for both articles and books. Three articles have statements more than 200 words long (Dix Reference Dix1984; Traugott Reference Traugott1983; Valenta Reference Valenta1984), which is more than two standard deviations from the mean, and three books have statements more than 370 words long (Dunn Reference Dunn1972; Kautsky Reference Kautsky1975; Walton Reference Walton1984), which is also more than two standard deviations from the mean. When these outliers are removed, the correlations between year and exposition are no longer significant, even if the trend is still in a negative direction. These results suggest that exposition is only weakly declining over time, and, thus, methodological consensus is also perhaps weak.

Overall, the trends in methodological awareness and consensus do not clearly confirm shared standards for comparative case selection. Explicitness declines over time and exposition is only modestly reduced. Thus, from scholars’ articulation of their case selection it seems possible that comparative methods have not yet institutionalized.

Methodological Consensus and Convergence

Methodological consensus does not only make methods increasingly taken for granted. Consensus, by its very nature, should reduce the diversity of case selection methods as some best practices are agreed upon and researchers move toward them over time. While it is difficult to rank which case selection methods are best, suggesting the limits of formalization by methodologists, it is possible to note which are certainly worst. As George and Bennett (Reference George and Bennett2005: 83) warn: “One should select cases not simply because they are interesting, important, or easily researched using readily available data.” Methodologists also caution against random sampling in comparative case studies (Gerring Reference Gerring2007; Goertz and Mahoney Reference Goertz and Mahoney2012) as the logic of inference is not the same as large-N quantitative methods (cf. Geddes Reference Geddes1990; King et al. Reference King, Keohane and Verba1994). So, at the very least, consensus should move away from pragmatic concerns and the logic of quantitative methodology.

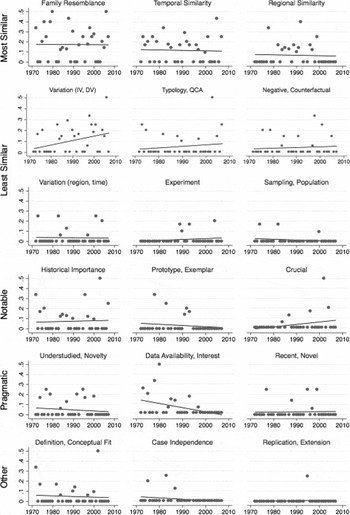

Figure 4 presents scatterplots over time of the proportion of methods used in a year. For each strategy, the numerator is the number of studies that employed that strategy and the denominator is the number of methods articulated in all studies published in that same year. What is apparent is that the trend for most case selection strategies in the study of revolution is mostly steady or modestly declining. Only 6 of the 18 methods have increased, even slightly, over the last four decades: selection by variation on the independent and dependent variables; use of typologies and QCA; employing negative cases and counterfactuals; natural experiments; choosing historically important cases; and use of crucial and fertile cases. Notably, these trends are not statistically significant. In fact, the only statistically significant correlation between year of publication and a method's share is the decline in selection due to data availability or researcher interest (β = −.40, p < .05). That is good news, at least, for those who would follow George and Bennett's (Reference George and Bennett2005) advice. But this is not accompanied by a clear trend of convergence on a consensual set of practices. This can be seen more clearly in figure 5, which groups the specific case selection strategies by the five general types. Use of most similar cases, notable cases, and other strategies is mostly level over time. Employing least similar cases has increased over the years, and pragmatic concerns decreased. But again, only pragmatic case selection has significantly decreased (β = −.36, p < .05), a result driven by the move away from availability and interest.

FIGURE 4. Proportion of case selection strategies by publication year.

FIGURE 5. Proportion of case selection method types by publication year.

In short, the trends in which methods are used do not reveal a growing consensus around a clear set of best practices. This could be the result of a failure by practitioners to heed methodological advice. But it could just as easily be because scholars have found little of use in methodological discourse. In either case, there is a failure for the give and take of discourse and practice to create consensus and, hence, promote institutionalization.

As indicated by table 2, there is a great diversity in case selection methods overall. Another way of assessing whether consensus and convergence has occurred is to examine this diversity. As a method institutionalizes and consensus grows, we should expect researchers to choose from the smaller menu of good options. Thus, even if multiple methods persist, researchers should use fewer of them over time. Figure 6 presents a scatterplot of the number of case selection methods used in a study by year of publication. As mentioned previously, the average overall is slightly less than three different justifications of case selection per study. As the scatterplot reveals, there is a slight decline throughout the years. In the 1970s, the average was 2.9 strategies per study and by the 2000s the average declined to 2.3 strategies. The trend is not statistically significant, however, even when the one clear outlier is removed.

FIGURE 6. Number of case selection methods in a study by publication year.

Yet even if the number of methods used has not significantly declined, perhaps the diversity of their combinations has. This can be assessed using a fractionalization index, which measures the diversity of a population.Footnote 3 The result, where higher values indicate greater fractionalization and thus more diversity of methodological approaches in a year, is presented in figure 7. Overall, comparative case studies have an average fractionalization index value of .744, which is quite high—similar to the ethnic diversity of countries like Afghanistan or Indonesia. Fractionalization in case selection methods declines slightly—from an average of .738 in the 1970s to .670 in the 2000s. This is akin, in terms of ethnicity, of moving from Ethiopia to Eritrea. Unsurprisingly, the trend is not statistically significant.

FIGURE 7. Fractionalization in case selection methods by publication year.

Overall, these results suggest that there is only limited convergence in how cases are selected. While methodologists may have some consensus about strategies, practitioners do not seem to share it. Few methods change notably in their rate of use over time, multiple strategies of case selection in one study remain common, and the diversity of their combination is fairly constant. Methodological consensus and convergence has yet to emerge. This again suggests that comparative methodology, at least regarding the rhetoric of case selection, is not yet institutionalized in practice.

Conclusions

An institutionalized method is one in which shared standards predominate. Thus, methodological awareness, consensus about practice, and convergence in use should occur as a method becomes generally accepted. However, the examination of case selection methods in the entire subfield of comparative case studies of revolution from 1970 to 2009 displays few of these features. If anything, researchers display less methodological awareness even as they feel less need to lengthily explain their choice of cases. Few selection strategies display much change over time and methodological diversity remains mostly constant, for which methodologists have not unaccounted. These results suggest that case selection, and perhaps comparative methodology in general, has yet to institutionalize in the social sciences.

It is possible that there has not yet been enough time for institutionalized practice to emerge. Conscious comparative methodology took off in the wake of 1990s criticisms of the method, resulting in a flurry of publications in the 2000s, the foundation of the American Political Science Association's Qualitative and Multi-Method Research section, and the Consortium on Qualitative Research Methods at Syracuse University. So, it may take more than one or two scholarly generations for a field to standardize. Yet comparative case methodology is not new (Ragin and Zaret Reference Ragin and Zaret1983). The 1970s, too, saw the establishment of the interdisciplinary Social Science History Association and by the 1980s the American Sociological Association had a section on Comparative and Historical Sociology, both centers of methodological awareness. The 1980s also had a general efflorescence in explicating the comparative method (e.g., Ragin Reference Ragin1989; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1984). Thus, attempts at formalization are not new, and may not by themselves be sufficient for methodology to translate into widespread practice.

In fact, earlier efforts may have perversely decreased standardization in the period studied here through two processes. First, conscious explication in the 1980s may have popularized comparative methods and increased the number of studies that use them. This could undermine the necessity of methodological reflexivity to an audience familiar with the approach. Second, innovation in comparative analysis proliferated the number of methods available to the researcher but without halting the use of outdated strategies, undermining standardization in practice. Together, popularization and innovation could yield the state of the field found in the analyses—decreasing explicitness over time, persistent diversity in strategies, and limited adoption of recommended practices.

Yet the failure of institutionalization does not lie with practitioners alone. Methodologists, focused on menus of possibilities rather than actual practice, seem to have missed the diverse purposes to which scholars put comparative methods. Thus, there is a substantial disconnect between methodologists and practitioners. This dynamic is not unique to comparative methodology—which statistician would approve of what is inferred from the regressions of most quantitative social science? Bridging the gap takes more than catalogs of a method's use. It requires recognition of a method's typical use and taking the practitioner's dilemmas and choices seriously. It also requires training of scholars and high standards of implementation from study design to study publication. Otherwise, standardization remains only academic.

There is an interesting implication here. Perhaps comparative methodology remains contested by positivist social scientists precisely because it did not quickly institutionalize in practice. From this view, methodological divides may be less about cultures of practice and more about practices of practice (cf. Goertz and Mahoney Reference Goertz and Mahoney2012; Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz2005).

Even if comparative methodology is not consensually discussed or used, a field can still generate useful knowledge. And this clearly is the case in the study of revolution. Findings have repeated themselves across generations of revolution theory, and some—like aspects of state-breakdown theory—have near consensual support (Goldstone Reference Goldstone2001). Yet a danger for the subfield lies in too quickly assuming that repeated results mean a substantiated theory. For instance, findings from a comparative study are only portable to the extent that the selection of its cases allow for such inferences to be made (Goodwin Reference Goodwin2001; Skocpol and Somers Reference Skocpol and Somers1980; Slater and Ziblatt Reference Slater and Ziblatt2013). But as we have seen, practitioners select their cases for a variety of purposes besides portability. Thus, the findings of comparative case studies might be limited in scope by the practice of case selection, whether intended or not.

The data gathered here do not only shed light on how cases are selected, but on which cases are compared. Table 4 presents the cases of revolution that have been studied 10 or more times over the last four decades. These dozen events are the lion's share of scholarly attention by comparativists—they make up 39 percent of all cases studied, with 191 different events filling out the remaining 60 percent. The most popular case for study, Nicaragua, by itself appears in 26 percent of comparative studies. And the list of popular cases is not what we might expect. Classic cases of “great revolutions” do not appear until rank 3, and are only a third of the most popular events. Modern, leftist cases predominate. Historical or geopolitical importance does not seem to predict popularity, otherwise why would Nicaragua outpace the Iranian Revolution, both revolutions of the same year against externally supported repressive regimes? And why does El Salvador or Guatemala or Bolivia rate among the most studied at all? Clearly, something beyond methodological concern occurs as the comparative method is practiced. This has important implications for what we think we know about the phenomenon of revolution, particularly as the subfield may be reinvigorated by the aftermath of the Arab Spring. Future work should seriously consider the universe of prior cases and comparisons to understand what knowledge has been gained or lost. Only with this sort of methodological awareness will the practice of comparative methodology hope to institutionalize.

TABLE 4. Cases of revolution selected 10 or more times