Introduction

The number and characteristics of people using charitable food assistance is often used as a de facto indicator of ‘hunger’ in high income countries. In Canada and the United States, it was the growing number of people seeking charitable food assistance in the early 1980s that first raised alarm and questions about the extent and nature of hunger in these countries. Today, the national food bank association in Canada annually releases the HungerCount report, which describes the number and characteristics of food bank users (Food Banks Canada, 2011). Similarly, data from food bank networks and recent studies of food bank users have been used to characterise and measure the extent of hunger in Finland (Salonen, Reference Salonen2014), Germany (Tinnemann et al., Reference Tinnemann, Pastatter, Willich and Stroebele2012) and the Netherlands (Neter et al., Reference Neter, Dijkstra, Visser and Brouwer2014). The recent expansion of the Trussell Trust food bank network and rapid growth in number of people using these and other food banks has raised alarm about hunger in the United Kingdom (Lambie-Mumford, Reference Lambie-Mumford2013; Taylor-Robinson et al., Reference Taylor-Robinson, Rougeaux, Harrison and Whitehead2013; Forsey, Reference Forsey2014).

Yet, data on food bank usage offer only limited insight into what is popularly described as ‘hunger’, but is now more precisely defined as household food insecurity. In this article we draw on a series of our own studies, and make a unique comparison of nationally representative data on household food insecurity with publically available data on food bank usage to critically examine food bank use as an indicator of food insecurity in Canada. We begin by reviewing the conceptual and operational definitions of household food insecurity and its monitoring in Canada. Next, we describe how food banks operate and how use is monitored. Comparing data from these two sources, we then highlight the discrepancies in information gleaned. We end with a discussion of reasons why food bank usage provides such limited insight into food insecurity and highlight how the utilisation of data on food bank use in place of data on food insecurity impedes understanding of vulnerability and intervention.

The concept of household food insecurity

The growing number of people receiving charitable food assistance in the United States in the 1980s prompted research in order to gain a better understanding of what ‘hunger’ meant in this context (Wunderlich and Norwood, Reference Wunderlich and Norwood2006). It was acknowledged that the problems of inadequate food and nutrient intake typically assessed with biochemical indicators of deficiency, wasting and stunting had largely been eradicated in the population. Similarly, the popularly used term ‘hunger’ did not necessarily refer to the physical experience of food deprivation. Research to gain insight into the meaning of ‘hunger’ in this context resulted in adoption of the term ‘household food insecurity’ to describe this phenomenon (Wunderlich and Norwood, Reference Wunderlich and Norwood2006).

A seminal study by Radimer et al. (1990) among low income mothers highlighted the multiple manifestations of insecure access to food, of which the physical sensation of hunger was only one. Food insecurity at the household level was described as experiences of depleting and unsuitable food supplies, uncertainty that food supplies would last and having to acquire household food supplies in socially unacceptable ways. Individuals’ experiences of food insecurity included modifications to food intake in quantity or quality, feelings of deprivation and lack of choice and an inability to maintain socially prescribed ways of eating (Radimer et al., Reference Radimer, Olson and Cambell1990). These elements are captured in the conceptual definition of household food insecurity put forward by the Life Sciences Research Office Task Force, which is that ‘food insecurity exists whenever availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or the ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways is limited or uncertain’ (Anderson, Reference Anderson1990: 1560).

Operational definition and measurement of household food insecurity

Through the 1990s, research was carried out by the United States Department of Agriculture to develop a questionnaire that would allow for the measurement of household food insecurity in the population across a continuum of severity (Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Cook, Thompson, Buron, Frongillo, Olson and Wehler1997; Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Andrews and Bickel1999). Factor analyses and Rasch modelling were applied to data from a population survey that included a range of indicators of food insecurity, described in earlier studies, to identify a core set of questions that fit a unidimensional scale of measurement (Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Andrews and Bickel1999). The eighteen items that make up the questionnaire, the Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM), encompass quantitative depletion of food supplies, consequences arising from it and concern about this becoming a reality, all of which are tied to a clause specifying that experiences were due to a lack of finances for food. Thus, food insecurity is operationally defined as ‘the uncertainty and insufficiency of food availability and access that are limited by resource constraints, and the worry or anxiety and hunger that may result from it’ (Wunderlich and Norwood, Reference Wunderlich and Norwood2006: 49).

While it is beyond the scope of this article to discuss the merits and limitations of the narrower definition and construct captured by the HFFSM with respect to the broader conceptual definition,Footnote 1 the experiences captured by the HFSSM are in line with the problem that food banks aim to tackle, in that they aim to prevent individuals from going without food and to provide the assurance of food support in the face of insufficient food supplies.

Household food insecurity monitoring in Canada

In Canada, population surveys in the 1990s and early 2000s included indicators of insecure food access, but measurement was inconsistent until 2007 (Kirkpatrick and Tarasuk, Reference Kirkpatrick and Tarasuk2008a). From 2007 onwards, food insecurity has been monitored nationally through the inclusion of the HFSSM in the Canadian Community Health Survey, a repeated cross-sectional survey designed to be nationally representative of 98 per cent of the population (Statistics Canada, 2012). The regular inclusion of the HFSSM module in this survey has enabled the tracking of the prevalence of food insecurity in the population (Tarasuk et al., 2013a), aided understanding of nutritional and health risks associated with food insecurity (for example, Kirkpatrick and Tarasuk, Reference Kirkpatrick and Tarasuk2008b; Gucciardi et al., Reference Gucciardi, Vogt, Demelo and Stewart2009; Tarasuk et al., Reference Tarasuk, Mitchell, McLaren and McIntyre2013b) and allowed identification of factors associated with greater vulnerability in the population (for example, Willows et al., Reference Willows, Veugelers, Raine and Kuhle2009; McIntyre et al., Reference McIntyre, Bartoo and Emery2012; Tarasuk et al., Reference Tarasuk, Mitchell, McLaren and McIntyre2013b). The availability of population survey data has also begun to allow identification of social policy drivers of this problem (Emery et al., Reference Emery, Bartoo, Matherson, Ferrer, Kirkpatrick, Tarasuk and McIntyre2012, Reference Emery, Fleisch and McIntyre2013; Loopstra et al., forthcoming).

Food banks in Canada

Although variously named food pantries, food banks or food depots, in this article we use ‘food bank’ to refer to agencies that enact the transfer of grocery-type foods free of charge to individuals in need. This model of charitable food assistance began in the United States, but began to proliferate in Canada in the 1980s in response to what was identified as a growing number of people without work and in need, in the face of economic downturn and welfare retrenchment (Riches, Reference Riches2002).

Today, food banks in Canada remain voluntary and extra-governmental, with no allocated government funding for their operations. The actual number of food banks operating remains uncharted because, although the national association, Food Banks Canada, tracks affiliated members (Food Banks Canada, 2013b), not all food banks are part of this association. Independent surveys of charitable food agencies have suggested about two-thirds are affiliated (Tarasuk and Dachner, Reference Tarasuk and Dachner2009; Bocskei and Ostry, Reference Bocskei and Ostry2010), and that the majority of charitable food distributed is through these affiliated agencies (Food Banks Canada, 2013b; Tarasuk et al., Reference Tarasuk, Dachner, Hamelin, Ostry, Williams, Bosckei, Poland and Raine2014a).

Food banks are run by a variety of organisations including faith groups, community service agencies, schools and community health centres, but almost all rely on donated food and volunteer labour (Bocskei and Ostry; Reference Bocskei and Ostry2010, Tarasuk et al., Reference Tarasuk, Dachner, Hamelin, Ostry, Williams, Bosckei, Poland and Raine2014a). Among 340 food banks surveyed in five Canadian cities in 2010, most were open only one or two days per week, typically on weekdays; all had procedures to screen prospective clients for eligibility (for example, applying income thresholds, lack of employment, living in catchment area), and most restricted the frequency with which people could obtain food hampers (Tarasuk et al., Reference Tarasuk, Dachner, Hamelin, Ostry, Williams, Bosckei, Poland and Raine2014a).

Monitoring of food bank usage in Canada is managed by Food Banks Canada, and consists of an annual survey of member food banks conducted each March. March was selected because this month is believed to be less vulnerable to seasonal variation and thus reflective of the average number of people using food banks in any given month over the year. During the month, agencies record the number of households and number of individuals within these households that receive a food hamper. They also collect sociodemographic information, including household income, source of income and household composition. The data are summarised in a report entitled HungerCount: A Comprehensive Report on Hunger and Food Bank Use in Canada, and Recommendations for Change, released each autumn.

Food bank usage as an indicator of household food insecurity

Next, we consider the merit of data on food bank use in the population as an indicator of household food insecurity in the population, evaluating how well the data relate to the prevalence, change over time and profile of vulnerability of food insecure households. Drawing on available data from 2007 through 2011, we examine how the annual count and characteristics of the number of people using food banks compare with the count and characteristics of people identified as food insecure in the Canadian Community Health Survey.

Prevalence of food insecurity and food bank use

In 2011, the number of people living in food insecure households was 4.6 times greater than the number of people living in households that received food from food banks in March of that year (Figure 1). Part of the discrepancy may be due to our comparison of the number of food bank users in a single month of the year with a measurement of food insecurity that asks individuals about their experiences in the past twelve months. A recent attempt by Food Banks Canada to estimate food bank usage for a twelve month period by incorporating information on first-time usage suggested that the number of individual people using food banks in year could be as high as 1.7 million people (Pegg, Reference Pegg2014). However, the number of food insecure individuals is well over two times higher than this estimate. Moreover, the prevalence of food insecurity is likely underestimated because the Canadian Community Health Survey does not capture some groups particularly vulnerable to food insecurity, namely First Nations people living on reserves, homeless populations and individuals living in remote areas. While they comprise only a small proportion of the total population, the very high rates of food insecurity documented among these groups (Holland et al., Reference Holland, Kennedy and Hwang2011; Rosol et al., Reference Rosol, Huet, Wood, Lennie, Osborne and Egaland2011; Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Hanning and Tsuji2014) suggest that there could be over 470,000 more food insecure individuals in Canada in addition to those captured by the Canadian Community Health Survey.Footnote 2

Figure 1. Magnitude of difference between reported number of individuals using food banks in 2011 and number of individuals living in food insecure homes in 2011.

While the comparison in Figure 1 is an ecological comparison of two different sources of data, early nationally representative surveys which directly measured both household food insecurity and food assistance usage documented similar discrepancies (McIntyre et al., Reference McIntyre, Connor and Warren2000; Rainville and Brink, Reference Rainville and Brink2001). Food bank usage statistics yield a substantial underestimate of the population prevalence of household food insecurity.

Trends in food insecurity and food bank use

The number of people using food banks paints a different picture of change over time than the trend in food insecurity over time. In absolute terms, the number of people experiencing food insecurity rose by over 606,500 individuals from 2007 to 2012. Data from the HungerCount reports highlighted a difference of only 130,800 more people using food banks over this period.

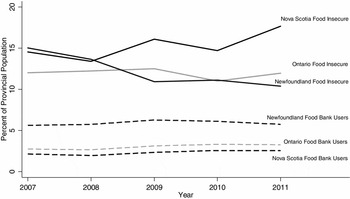

Provincial trends in food insecurity prevalence, available from 2007 to 2011, also differ from the trends in food bank use (Figure 2). First, we note that food bank usage remained relatively steady in Newfoundland and Labrador over this period, even though there was a steady decline in household food insecurity. In contrast, in the province of Nova Scotia, household food insecurity was steadily rising from 2007 to 2011, but food bank usage remained relatively stable. In the province of Ontario, household food insecurity rates fluctuated throughout what was in effect a recessionary and recovery period, but food bank usage largely remained stable. In sum, food bank usage appears to be insensitive to either reductions in, or growing levels of, household food insecurity in the population; rather, food bank usage remains relatively constant within a much larger and dynamic rate of food insecurity in the population.

Figure 2. Provincial trends in population use of food banks and food insecurity.

Profiles of food insecure households and food bank users

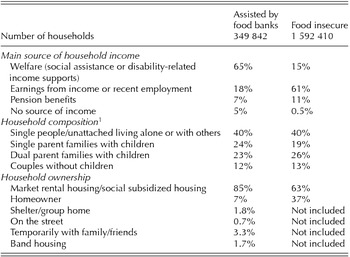

The profile of vulnerability that emerges from an examination of the characteristics of food bank users suggests that this group is a non-random subset of the larger population of food insecure households in Canada (Table 1). There are a number of important differences between food bank users and the wider food insecure population. Firstly, households receiving welfare (excluding unemployment benefits)Footnote 3 make up 65 per cent of households using food banks, but only 15 per cent of households that are food insecure. Accordingly, households reliant on employment make up fewer than one in five of households using food banks, but three in five of households that are food insecure. Secondly, vulnerability to food insecurity among older people,Footnote 4 as indicated by being in receipt of a main source of income from pensions, is also almost rendered invisible in food bank statistics, whereas older people make up 11 per cent of food insecure households. Thirdly, homeowners are also nearly absent from data on food bank users, but they make up a significant part of the food insecure population. Finally, as indicated in Figure 1, children make up a higher proportion of food bank users than they do the number of food insecure individuals.

Table 1. Profile of food bank users in comparison with the profile of food insecure households in Canada, 2011.

Note: 1 Other household composition arrangements not shown.

Sources: Author calculations from HungerCount, 2011 (Food Banks Canada, 2011) and Canadian Community Health Survey, 2011 (Statistics Canada, 2012).

Why food bank use is a poor indicator of household food insecurity

Our comparison of data on food bank usage and food insecurity in the Canadian population highlights that food bank usage is not a sensitive indicator of food insecurity. As per the operational and conceptual definitions, the use of a food bank correctly identifies someone experiencing food insecurity because it indicates an action in response to the experience of insufficient and insecure access to food. Indeed, studies that have included measures of both food bank usage and food insecurity show that almost all food bank users are classified as food insecure using the HFSSM (Tarasuk and Beaton, Reference Tarasuk and Beaton1999; Loopstra and Tarasuk, Reference Loopstra and Tarasuk2012). The non-use of food banks, however, does not indicate a lack of food insecurity because food bank use statistics miss a significant proportion of the food insecure population.

The extent to which food insecure individuals use food banks and are reflected in food bank statistics is a function of two factors; firstly, the nature of food bank operations with respect to accessibility; and, secondly, the severity of different households’ circumstances. We discuss each of these factors in turn.

Food bank operational aspects constrain food bank usage

By their operational structures, food banks inherently restrict both the number of people who can receive assistance and who are able to receive assistance. Food banks in Canada rely on food donations from the food industry, and to a lesser extent, the public (Food Banks Canada, 2013c). The reliance on donated food means both the amount and type of food available for distribution is limited, setting the stage for agencies to implement eligibility criteria and limit the frequency and amount of assistance given to those deemed eligible (Tarasuk and Eakin, Reference Tarasuk and Eakin2003). However, even with these restrictions in place, many food banks have to turn individuals away at times, or close early, because they have run out of food (Food Banks Canada, 2011; Tarasuk et al., Reference Tarasuk, Dachner, Hamelin, Ostry, Williams, Bosckei, Poland and Raine2014a). This means that regardless of the number of food insecure people in a community, only a proportion may be able to receive food assistance.

Food bank operations also define the characteristics of the people they serve. As highlighted in Table 1, employed households make up only a small proportion of food bank users. This could be because food insecure households with employment are less able to make use of food banks if limited operating hours conflict with work schedules, or because eligibility criteria at some food banks preclude households with employment (Hamelin et al., Reference Hamelin, Mercier and Bedard2011; Tsang et al., Reference Tsang, Holt and Azevedo2011; Loopstra and Tarasuk, Reference Loopstra and Tarasuk2012). In addition to logistical barriers, in our study of food insecure families who did not use food banks in Toronto, we found that the charitable nature of food bank operations influenced how food insecure individuals with employment felt about using food banks; they indicated that the fact that they had employment made them feel they should not ask for charity (Loopstra and Tarasuk, Reference Loopstra and Tarasuk2012).

The reliance on donated food also means that the quality and quantity of food given away tends to be poor. Studies across several Canadian cities have documented serious limitations in the amount of food and quality of food distributed, including foods that were past ‘best before’ dates, highly processed and superfluous and quantities that would only provide for one to three days’ worth at most (Tarasuk and Eakin, Reference Tarasuk and Eakin2005; Irwin et al., Reference Irwin, Ng, Rush, Nguyen and He2007; Bocskei and Ostry, Reference Bocskei and Ostry2010). The ‘last resort’ foods that make up much of the food distributed by food banks mean that, in turn, they are looked upon as precisely ‘last resort options’ by individuals experiencing food insecurity (Loopstra and Tarasuk, Reference Loopstra and Tarasuk2012). Many food insecure families we interviewed reported not going to food banks because it was not worthwhile given the paltry amount of support received and the uncertainty of whether any food would in fact be available at all (Loopstra and Tarasuk, Reference Loopstra and Tarasuk2012).

Food bank use and severity of household circumstances

In an effort to allocate scarce resources to those most in need, food banks typically prioritise those they regard as being in the direst circumstances. In our study of food insecure families, food bank use was most common among those experiencing most extreme manifestations of food insecurity (for example, being unable to eat when hungry) (Loopstra and Tarasuk, Reference Loopstra and Tarasuk2012). Among food insecure families who did not use food banks, many said they would only use a food bank if in desperate circumstances. With respect to these observations, however, it is important to note that even among families experiencing severe food insecurity, which indicates individuals going without food, food bank use is only about 40 per cent (Rainville and Brink, Reference Rainville and Brink2001; Loopstra and Tarasuk, Reference Loopstra and Tarasuk2012), suggesting that statistics on food bank use do not even fully capture those in the most desperate circumstances.

Although the degree to which food bank screening and promotion are targeted toward particularly vulnerable groups has not been systematically examined, studies have documented that food banks tend to prioritise households on social assistance, reflecting the extreme vulnerability to food insecurity in this group (Tarasuk et al., Reference Tarasuk, Dachner and Loopstra2014b). This may also explain the differences in trends observed for food bank use and food insecurity, where food banks users may represent households trapped in chronic poverty and therefore less sensitive to macro determinants such as labour market conditions and policy interventions.

Implications of using food bank statistics to represent household food insecurity

The HungerCount report is widely covered by the media each year (for example, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 2013). Food bank statistics are also used extensively by public and non-profit agencies and researchers to detail the problem of hunger in Canada, to lobby government and to make social policy recommendations (for example, Goldberg and Green, Reference Goldberg and Green2009). Food Banks Canada itself has the mandate of ‘raising awareness of hunger’ and ‘conducting research and creating policy recommendations that will reduce hunger and poverty in Canada’ (Food Banks Canada, 2013a), both of which are tied to their data collection on the number of people receiving food from member agencies. Food bank statistics are also used by Members of Parliament and provincial ministries to provide insight on the success or failure of specific policy interventions and impact of macroeconomic trends on population well-being. Indeed, food bank statistics were used in the report published by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food in Canada, to provide evidence of the failure of social protection schemes to meet basic needs (De Schutter, Reference De Schutter and De Schutter2012). The use of food bank statistics by various policy actors means the magnitude of food insecurity in Canada is significantly understated, important temporal shifts in the prevalence of food insecurity are unrecognised, those experiencing food insecurity in the population are inaccurately characterised and the policy drivers underpinning growing food insecurity in Canada are only partially examined. Thus, proposed interventions are typically neither of the scale necessary to effectively address the problems nor reach a large proportion of food insecure households.

The insensitivity of food bank statistics to household food insecurity highlights the importance of food insecurity monitoring to chart the scale and nature of vulnerability in the population, to understand causes of food insecurity and to evaluate policy and programmatic interventions. Yet, the national monitoring of household food insecurity has scarcely been drawn upon to characterise the problem of hunger, its drivers, and trends, nor has it been selected as an indicator to monitor progress on poverty reduction. Indeed, in Canada, there is an absence of social policies that have been targeted toward ensuring that that individuals have secure and sufficient access to food.

The dominance of the HungerCount to portray and monitor hunger in Canada is likely to reflect the fact that these data have been in use in Canada since 1989, but consistent food insecurity monitoring is relatively recent, beginning only in 2007. Furthermore, the location of this monitoring in the federal government has meant limited dissemination of survey results, whereas media releases accompany the publication of annual HungerCount reports. Because food banks are so entrenched in Canadian society, HungerCounts are likely to resonate with Canadians’ understanding of how the inability to afford sufficient food is manifest in going to a food bank. The monitoring of food insecurity has put the number of people using food banks into perspective, however, as illustrated by a recent discussion of this issue in the 2014 HungerCount (Food Banks Canada, 2014). Using monitoring data rather than food bank statistics is reshaping our understanding of the problem in two important ways. Firstly, the excess of household need in the context of what has been a continually expanding food bank system points to the need for other, more systematic interventions to prevent and ameliorate this problem. Secondly, population monitoring of food insecurity affords the ability to evaluate the success and failure of interventions as impact is very unlikely to be detectable through examinations of changes in food bank numbers. Thus, there is much greater potential to identify policy and programme interventions that can effectively ameliorate or prevent this problem.

Conclusions

Our examination of Canadian data shows that food bank usage is a poor indicator of household level food insecurity, and it seriously underestimates both the number and nature of people experiencing food insecurity. It captures only those that are able and driven to use food banks because of their extreme need. From a social policy perspective, population monitoring of food insecurity is imperative for understanding the true number of people experiencing insecure and insufficient access to food, the full spectrum of households affected and the impact of policy interventions and changing economic conditions on this problem.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Programmatic Grant in Health and Health Equity, Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (FRN 115208).