Introduction

The Scandinavian or Nordic model is known for its universal role and the fact that a progressive tax-funded public sector plays an important role in providing welfare to its citizens (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Korpi and Palme, Reference Korpi and Palme1998, Coote, Reference Coote2022; Vamstad and Karlsson, Reference Vamstad and Karlsson2022). Since the late 1980s, Sweden’s public sector has allowed a significant share of its welfare services to be offered by private providers, resulting in a quasi-market where private and public providers compete (Le Grand, Reference Le Grand2007). The inclusion of private actors and the allowing of market mechanisms have been particularly notable in elderly care, starting in the late 1980s, when private management objectives were introduced into Swedish welfare (Montin and Elander, Reference Montin and Elander1995). The idea here is that greater choice will lead to higher quality for the individual. It also aims to introduce greater efficiency through public and private service providers competing with each other (Nordgren, Reference Nordgren2010; Nordgren and Ahgren, Reference Nordgren and Ahgren2011).

An essential principle underlying the welfare state is the egalitarian provision of and equal access to high-quality services for all (Blomqvist and Palme, Reference Blomqvist and Palme2020). The creation of value in welfare services is connected to the quality that is experienced and the extent to which expectations are met; however, it is also constrained by the limitation of the resources or capacities available (Leifland and Nordgren, Reference Leifland and Nordgren2023).

The aim of this paper is to investigate the co-creation of value in the Scandinavian welfare system. The paper analyses the reasoning behind the municipality’s decision-making process when matching the applicants for service homes for the elderly with the apartments available. The aim is met by posing the following research questions.

-

1. How do individual expectations differ between the applicants?

-

2. How do the employees take the applicants’ expectations into account when allocating the resources available, e.g. nursing homes?

Literature review

Co-creation has been discussed extensively in research on the service-dominant logic (SDL) in health care (Vargo and Lusch, Reference Vargo and Lusch2004; Vargo et al., Reference Vargo, Maglio and Akaka2008; Gallan et al., Reference Gallan, Jarvis, Brown and Bitner2013; Barros et al., Reference Barros, Brouwer, Thomson and Varkevisser2016; Hardyman et al., Reference Hardyman, Garner, Lewis, Callaghan, Williams, Dalton and Turner2022). The service-dominant logic in health care entails both the service provider and the individual user creating value by integrating the resources available (Joiner and Lusch, Reference Joiner and Lusch2016). Vargo and Lusch (Reference Vargo and Lusch2016) additionally assert that the SDL underscores the significance of the intangible elements, including knowledge, abilities, and procedures, of value creation. In the context of health care, this approach shifts the focus away from tangible products, such as medicines and built infrastructure, towards the value and service created by interactions. A fundamental aspect of the SDL is the integration of resources, whereby the needs of a patient are met by combining operant (intangible aspects) and operand (tangible aspects, such as equipment and health care facilities) resources (Vargo and Lusch, Reference Vargo and Lusch2016).

Co-creation emphasises the individual’s own ability to participate in the process and the fact that the service should facilitate this creation (Normann, Reference Normann2001). This user-centric perspective is commonly applied to mainstream service research (Jaakkola and Alexander, Reference Jaakkola and Alexander2014). However, scholars argue that, when it comes to welfare services in general, and health care for the elderly in particular, the political framework of the co-creation process is more important than the user-centric perspective (Moberg, Reference Moberg2017; Szebehely and Meagher, Reference Szebehely and Meagher2018). Policy framework determines how value is created and which type of value is prioritised. The SDL revolves around the individualisation of resource integration (Skålén et al., Reference Skålén, Engen, Magnusson, Bergkvist, Karlsson, Russo-Spena and Mele2016), but often neglects that social policy and welfare systems focus on social class and recognise the stratification of social solidarity (Roumpakis, Reference Roumpakis2020). In this context, Antony Giddens (Reference Giddens2013) is an important contributor in setting the goals for a third way, in the UK, in between the individualisation of neo-liberal market innovations and the normative ideals of social democracy. In this version, service users were invited to participate in the creation of public value propositions. However, an inherent asymmetry in the power balance inevitably becomes entwined in this process (Sevenhuijsen, Reference Sevenhuijsen2000). Additionally, criticism is directed towards third way politics, suggesting that it tends to overly align with communitarian ideals, thereby individualising the responsibility for welfare and social cohesion (Rose, Reference Rose2000).

In the past, care giving primarily focused on aligning patients with the existing system of services, often necessitating the adjustment of their needs to fit with the resources available (Lydahl and Hansen Löfstrand, Reference Lydahl and Hansen Löfstrand2020). However, contemporary health care practices have evolved and are now both more flexible and attuned to meeting individual preferences during service provision (Eriksson and Andersson, Reference Eriksson and Andersson2024). This perspective views the patient as an active participant in the process, with a primary emphasis on the aspects of value borrowed from the management literature, e.g. customer satisfaction (Joiner and Lusch, Reference Joiner and Lusch2016), resource integration (Hardyman et al., Reference Hardyman, Garner, Lewis, Callaghan, Williams, Dalton and Turner2022) and efficient resource utilisation (Connell et al., Reference Connell, Fawcett and Meagher2009). In the health services management literature, patients are often referred to as either customers or end consumers (Nordgren, Reference Nordgren2003; McColl-Kennedy et al., Reference McColl-Kennedy, Vargo, Dagger, Sweeney and van Kasteren2012; Jaakkola and Alexander, Reference Jaakkola and Alexander2014; McColl-Kennedy et al., Reference McColl-Kennedy, Snyder, Elg, Witell, Helkkula, Hogan and Anderson2017).

Viewing patients as customers inevitably leads to contradiction with the primary aim of the welfare system, i.e. that welfare should not depend on a market position (Bambra Reference Bambra2005). An approach that deals with health care from a consumer perspective assumes the existence of a more or less free market, which prioritises profit and price rather than quality (Stolt et al., Reference Stolt, Blomqvist and Winblad2011). This profit-oriented approach has demonstrated increased polarisation, commodification, crowding out, and cream skimming (Christiansen, Reference Christiansen2017; Werbeck et al., Reference Werbeck, Wübker and Ziebarth2021; Lapidus, Reference Lapidus2022), resulting in the availability of health care services to the more vulnerable segments of the population being reduced. Health care also tends to be rooted in the more emotional and affective aspects of care, and thus it is hard to make rational choices (Fotaki, Reference Fotaki2014; Von Heimburg and Ness, Reference Von Heimburg and Ness2021).

Seatown – an institutional case

A major municipality in southern Sweden, which we call Seatown, allows individuals to make more independent decisions regarding who should provide their care. In municipalities that have freedom of choice regarding elderly care, it is possible to choose between private and public providers. Services are still, however, financed and procured using the public purse. To get access to a retirement home, the applicant must first be assessed by assistance caseworker at the municipality. These officers assess the applicant’s needs and determine whether they meet the criteria regarding residence in a retirement home. If the criteria are met, the applicant will then be referred to the municipality’s accommodation coordinators.

The project has received the approval of the regional ethical review authority in Lund (Ref. no. 2014:631) and uses a mixed methodological design (Greene et al., Reference Greene, Kreider and Mayer2005). The study is co-funded by the municipitality we are investigating.

Methodology

This article combines surveys, interviews, and focus groups to develop the ideas of the SDL in a health care setting. The study is designed as a case study wherein Seatown is used to develop knowledge of the matching process for retirement homes. During a case study, a variety of data collection methods are employed to facilitate an in-depth examination of a given phenomenon (Priya, Reference Priya2021). For our study, Seatown was picked as an institutional case providing us with specific knowledge of the matching process we set out to analyse.

This study examines the social processes constructed between the normative prescriptions for the employees and the actual everyday practices manifesting themselves within the system (i.e. Burawoy, Reference Burawoy1998). The case is constructed by the narratives shared by the interviewees, with the attitudes expressed by the applicants revealing underlying social processes going beyond the aspects captured solely in the interviews or survey responses (Smith, Reference Smith2005; Devault and McCoy, Reference DeVault, McCoy and Smith2006). This study design conceptualises the matching process by using Seatown as a case.

Mixed methods: surveys and interviews

The surveys were sent out to all individuals applying for accommodation at a service home during the period between November and December 2014. This survey was distributed, during the first half of 2015, to those undergoing the matching process. The primary objectives of this survey were to delineate the aspects valued as significant by the applicants and to discern their expectations regarding future care and service. Additionally, the applicants’ background information, comprising age, sex, education, and family structure, was gathered.

The questionnaire was divided into three distinct sections. Part one included the background variables.

Part two focused on the care and nursing aspects. These questions were presented using Likert scales, and the respondents were able to provide answers on a four-point scale: i.e. ‘Very important’, ‘Quite important’, ‘Quite unimportant’, and ‘Not at all important’. Part two was further divided into three subsections (A, B, and C), where subsection A comprised questions relating to staff, Subsection B addressed care-related matters, and Subsection C addressed health care-related inquiries.

Part three of the questionnaire pertained to the living environment. Akin to part two, it was also subdivided into three subsections (D, E, and F). Subsection D consisted of questions concerning food, Subsection E addressed aspects relating to activities, and Subsection F addressed the housing-related aspects.

After each section (A-F), the respondents had the opportunity to answer an open question about the topic of each section, e.g., is there anything else you would like to share about care/health care/housing. The responses were subsequently subjected to analysis using IBM Corp. (2016) SPSS Statistics software, version 24. Correlation analyses were conducted using chi-square tests to assess the relationships between the categorical variables. These tests allowed us to determine whether there were statistically significant associations between the variables under study.

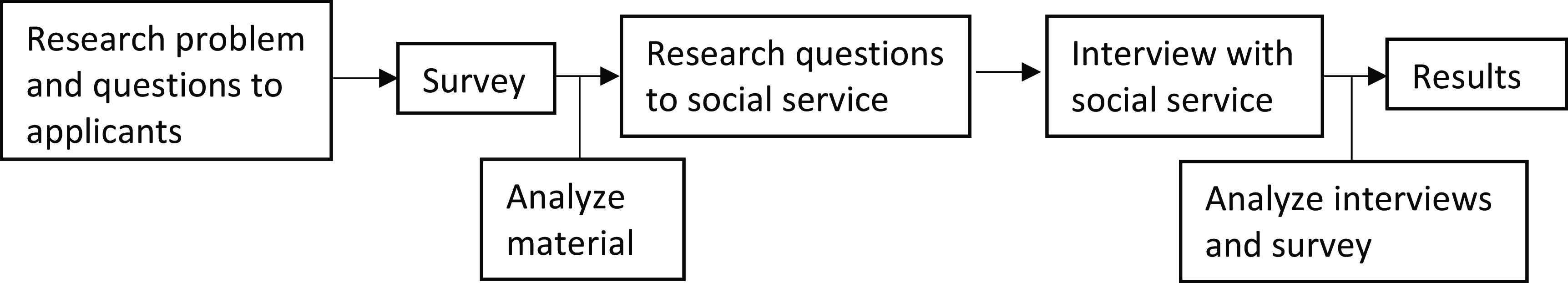

The second phase of data collection involved interviews with all the assistance caseworker and accommodation coordinators. These interviews were informed by the empirical data acquired via the questionnaires sent out in the previous step. The objective of the interviews was to gain knowledge of the processes used by the accommodation coordinators and assistance caseworkers when matching the preferences of the applicants to the retirement homes available. This section aimed to examine the way in which the balancing between the applicants’ wishes and the available resources is understood on the institutional level. An approach was adopted which allowed the examination of the institutional dynamics and structures exerting an influence on the narratives constructed during the focus groups (Smith, Reference Smith2005). In this manner, the interviews generate narrative data, which Gubrium and Holstein (Reference Gubrium and Holstein2009) conceptualise as a narrative environment. During the interviews, knowledge of the matching processes is constructed (Moenandar et al., Reference Moenandar, Basten, Taran, Panagoulia, Coughlan and Duarte2024). The interviews were conducted in an open-ended and unstructured manner, allowing the interviewees to express their thoughts and opinions freely, rather than directing them towards a set of predetermined questions and themes. The process is summarised using this model (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Work process

Sampling procedures and dropout analysis

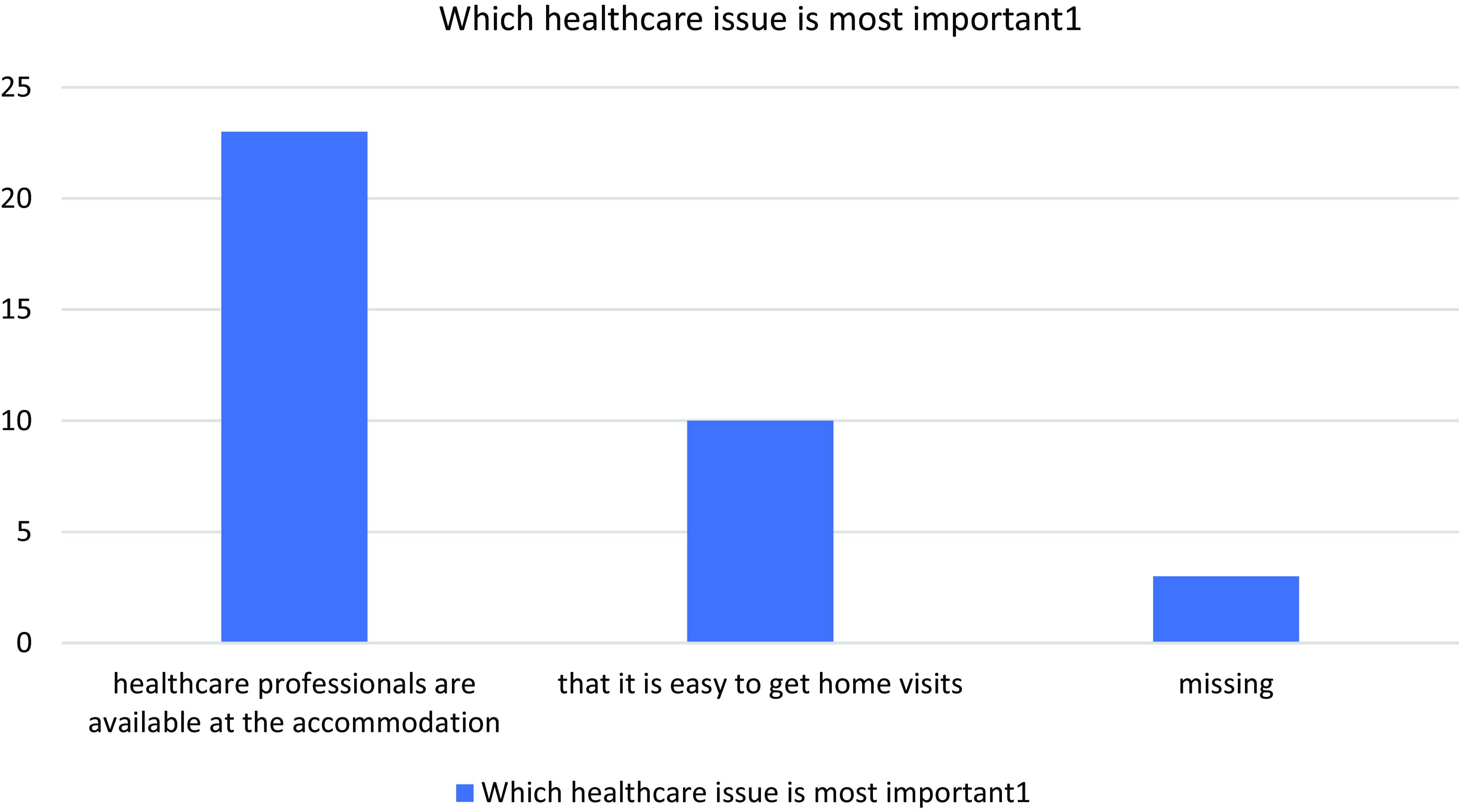

This study is a complete survey of all the people who applied to live in a care home in Seatown over a certain period of time and got their application approved. The questionnaire was sent to a total of 161 people, thirty five of whom responded. All the applicants who got their request approved for a service apartment for the elderly between November and December, 2014 were provided with the questionnaire. The total number of approvals were 267 during the whole year, we reached 60 per cent of the total number for 2014. But the response rate was relatively low. Our aim was not to generalise but to show and develop knowledge of the prerequisites for value creation at a major Swedish municipality. The surveys present a description of the attitudes held by the individuals who had applied for a service apartment. This description allows us to gain a perspective on the way attitudes intersect with the background variables, as illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1. Background variables

The total number of applicants (161) for a nursing home during the autumn of 2014 consisted of ninety-eight (61 per cent) women and sixty-three (39 per cent) men. One hundred and thirty-three lived in Seatown, with the rest being spread out among the smaller communities nearby. The response rate was thirty-six (23 per cent), but one of these only showed valid answers to the first three questions, so we decided to delete this respondent. Of those who responded, twenty-two (63 per cent) were women and thirteen were men (37 per cent). In terms of sex, the breakdown of the responses received is somewhat similar to that of the overall population. The same applies to place of residence.

Descriptive analysis

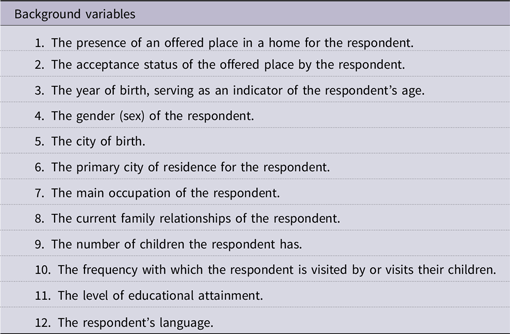

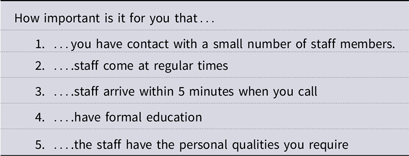

Regarding which aspect of the care staff was considered the most important by the respondents, a strong desire was expressed to see specific qualities and attributes. The formal educational level of the staff ranked as the least important factor (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Most important staff issue

Furthermore, the respondents also highlighted aspects relating to individual qualities and personal attributes as the most important.

When given the opportunity to express personal preferences, the respondents also emphasised the significance of individual qualities:

“[the services] Should be about: Empathy, for the patient, integrity, the ability to speak Swedish, to be very gentle and caring towards the elderly. Ideally, [the cregiver should be] female.

“Should be present and not leave them to sit alone at the table”

“They mustn’t be in a hurry, or have no time to talk to their patients”

“Make jokes and be in a good mood”

In this context, personal competence and qualities are of greater value than aspects relating to a formal education or general competence. In response to the question about which aspect of care was the most important one, the most common answer was that assistance with day-to-day hygiene was the most crucial. These aspects can be conceptualised as operant resources within the SDL framework, i.e. resources that are intangible (Vargo and Lusch, Reference Vargo and Lusch2016) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Most important care issue

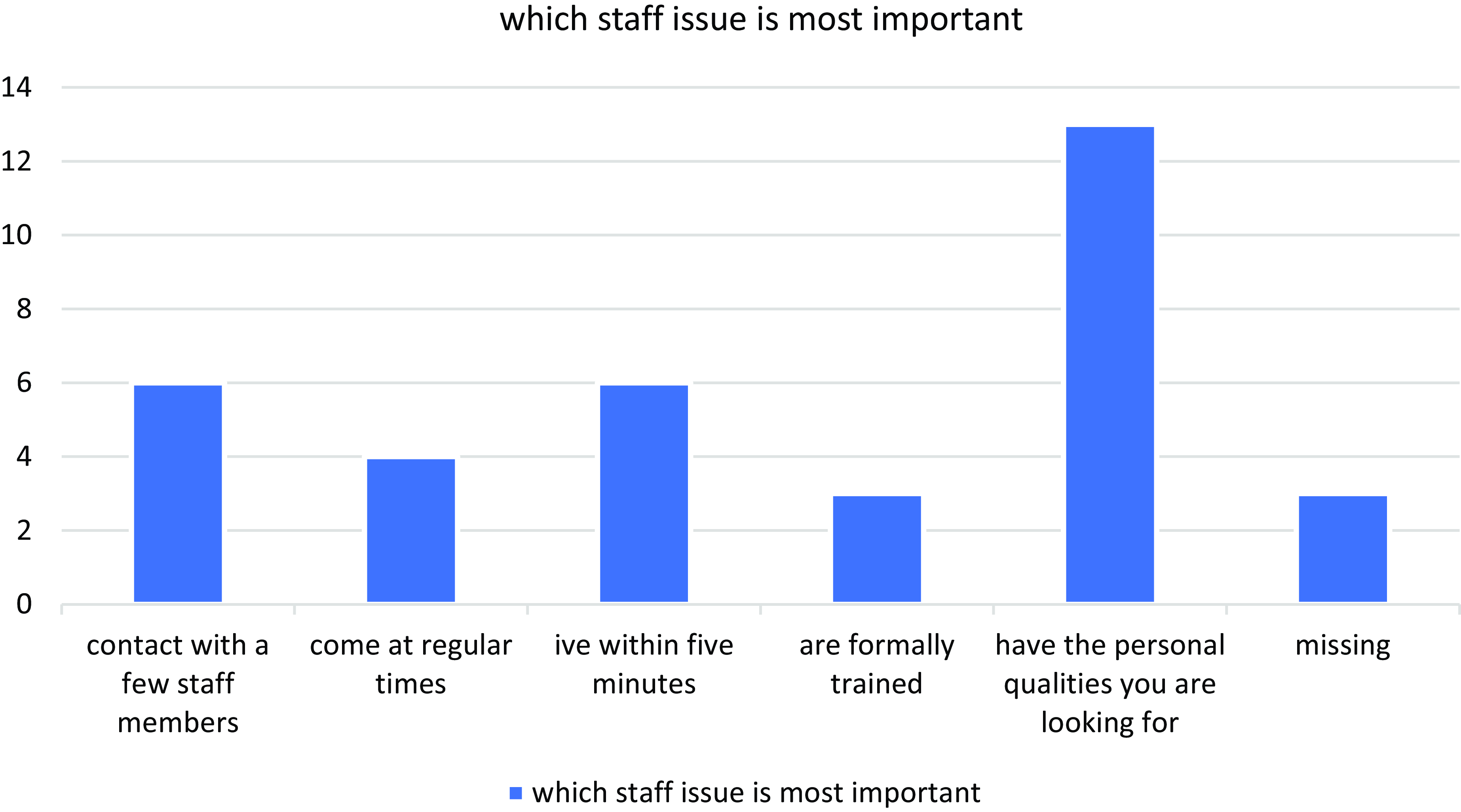

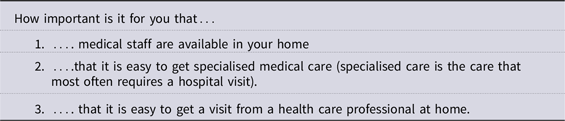

When asking the respondents about the most crucial aspect of health care, accessibility emerged as the greatest concern. None of the participants valued access to specialist care as their primary priority (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Most important healthcare issue

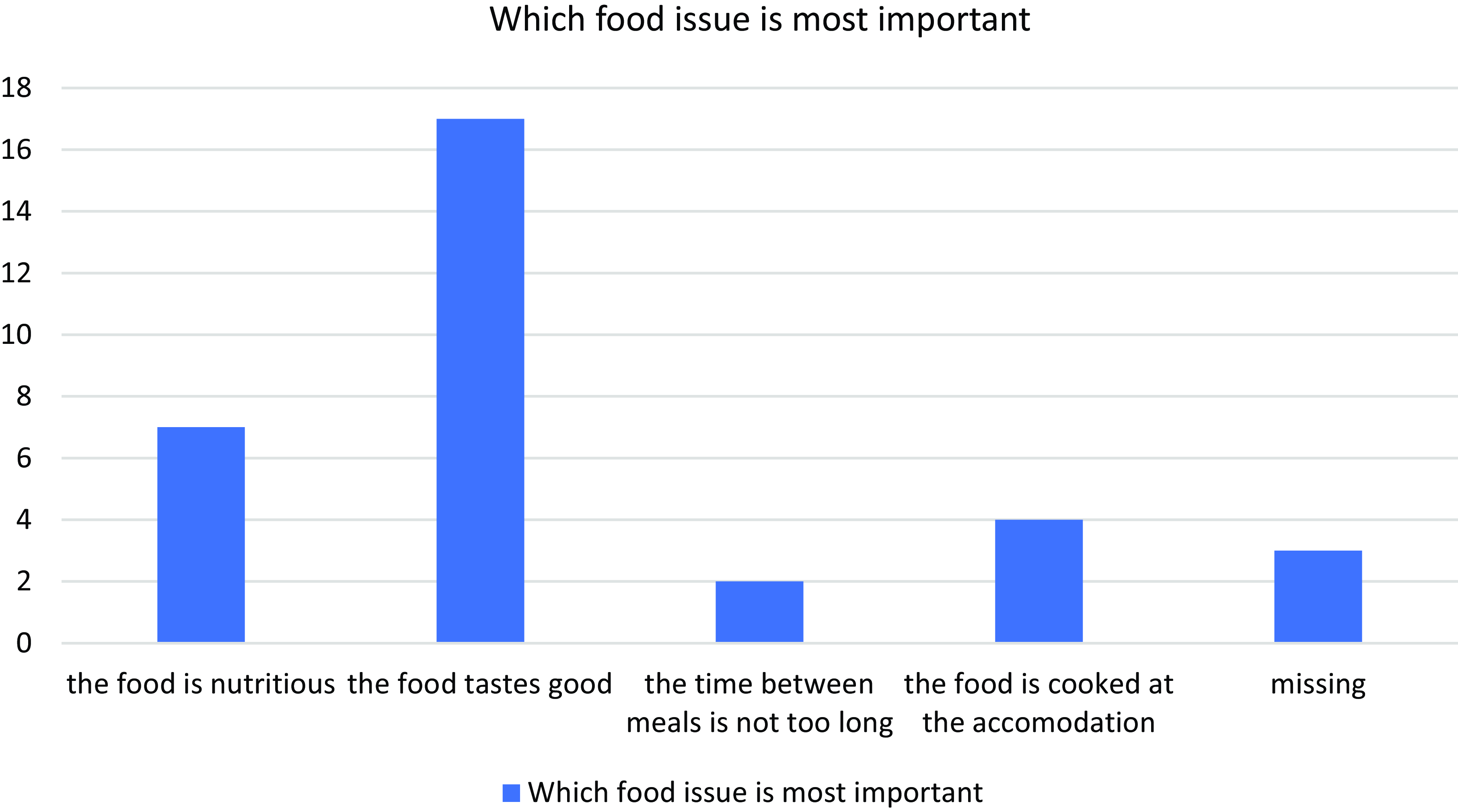

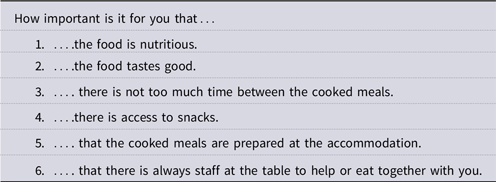

When asked about their assessment of the most important aspect of the food, a prominent response was that it should taste good (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Most important food issue

The open-ended comments revealed different perspectives, shedding light on additional aspects of respondents’ views on this issue.

“That the hot food is prepared at the home itself. Smelling the aromas when the food is being cooked stimulates your appetite.”

“Vegetables are rare. Fruit has never been seen.”

“The food would be nicer if someone from the staff was present at the table.”

The comments presented here illustrate individual experiences while also highlighting the importance of creating a pleasant and socially engaging environment. Specifically, the respondents emphasised their desire for a positive and qualitative dining experience involving the staff.

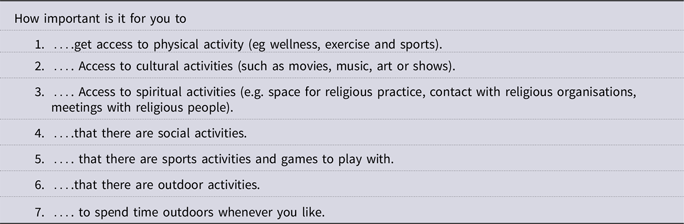

In relation to activities, the participants identified the freedom to access outdoor spaces at their discretion as the most important aspect (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Most important activity aspect

In relation to this diagram, the open-ended comments provided valuable qualitative insights.

“It’s important for me to have my freedom. To be able to go where I want.”

“I’m in a wheelchair and can’t go out on my own. I’d like to be wheeled out for a walk, but that happens far too rarely.”

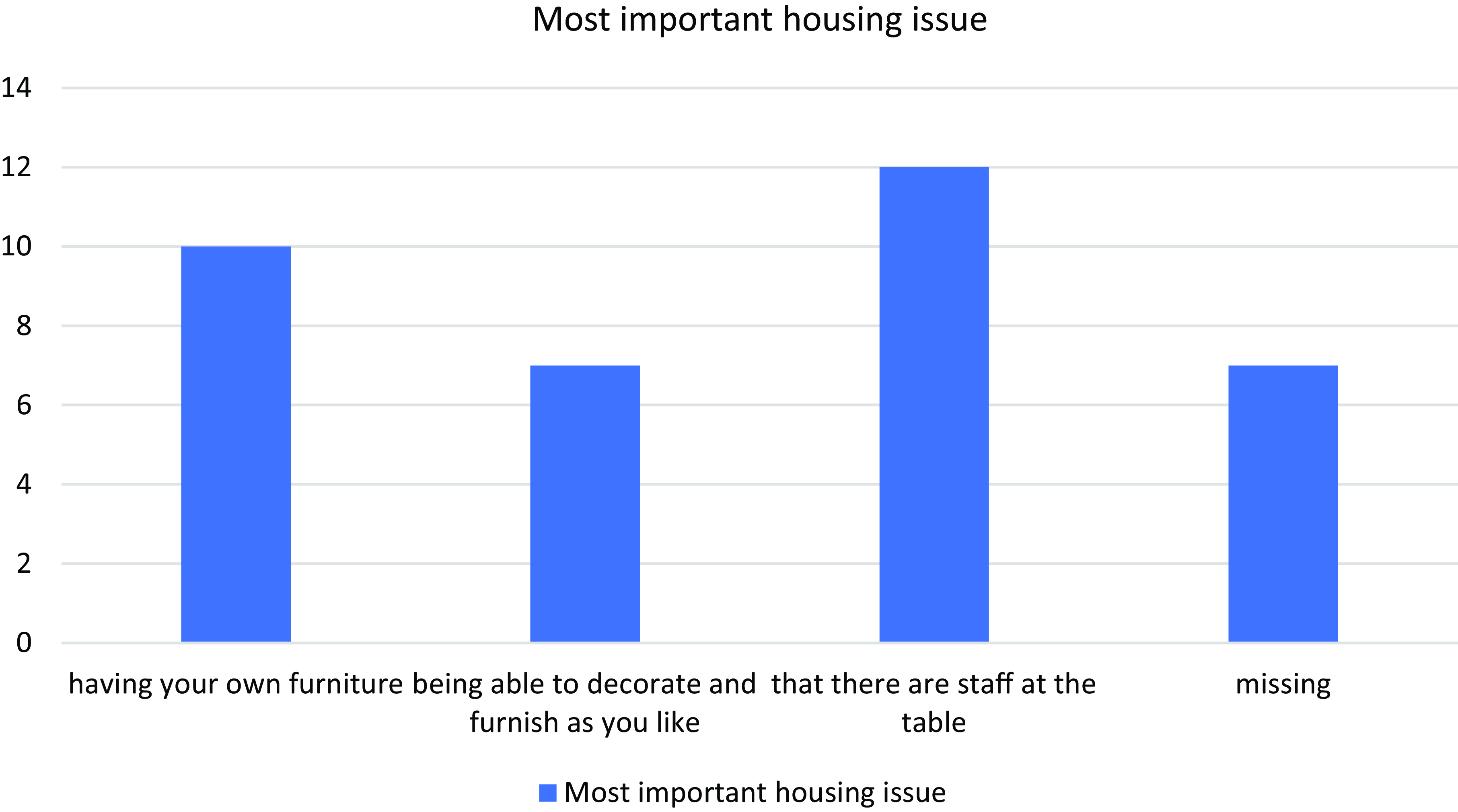

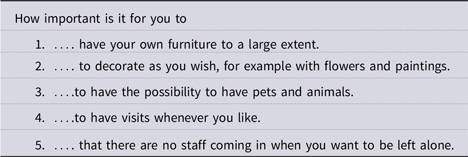

The most striking consideration concerning accommodation pertains to the at-table presence of staff during meals, with the availability of personal furniture also being an essential (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Most important housing issue

The open comments show the respondents’ inclination towards being recognised as distinct individuals with their own agency.

“That everyone’s an individual.”

“More staff.”

“Take a break whenever possible.”

“Maybe a small vegetable garden outside, where we can grow some herbs and vegetables for our meals.”

“The possibility to choose where you want to be, which location. The same staff coming more often.”

“I want to move to an own accommodation as soon as possible.”

The comments express spending more time with staff and having more individualised approaches. These expectations are hard to fulfil from a management perspective which focuses on the effective use of resources (Newman and Lawler, Reference Newman and Lawler2009). It also hinders the co-creation of value when every part of the organisation is considered a microcosm of the larger unit within which it is embedded (Connell et al., Reference Connell, Fawcett and Meagher2009).

Correlations

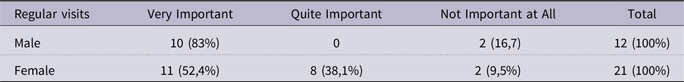

In this section, we only report results achieving a p-value of <0.05 in a Pearson Chi-square test. Due to the response rate, the p-values should be interpreted as indicative guidelines rather than absolute measures of significance. After conducting the Chi-square test on the dataset, we found a significant association between the variable concerning how important it is for staff to come at regular times and sex χ2(1, N=33)= 6,043, p < .049. Women are more heterogenous in their attitudes (Table 3).

Table 2A. Staff related variables

Table 2B. Care related variables

Table 2C. Health care related variables

Table 2D. Food related variables

Table 2E. Activity related variables

Table 2F. Housing related variables

Table 3. Correlation sex and regular visits

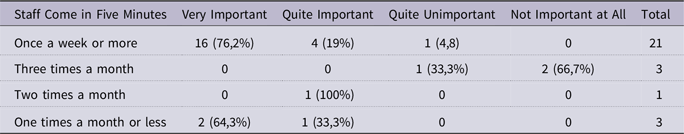

A Chi-square test on the variables of how often you visit or are visited by your children and how important it is for staff to come within five minutes, we found a significant association between the variable concerning how important it is for staff to come at regular times and sex χ²(9, N=28)= 28,85, p < .049. The distribution here is also affected by the small amount of data. However, the results show a slight difference in the responses: Those in better contact with their children find it more important to have quick access to health care than those in less contact (Table 4).

Table 4. Correlation children visit and quick access

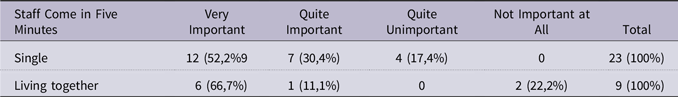

As regards testing on the variables of family conditions and how important it is that staff come within five minutes, we found a significant association showing that people living with someone have a stronger opinion as to whether this is important or not χ²(3, N=32)= 7,884, p < .048. People living alone chose the alternatives of rather important or rather unimportant more often than those living with someone (Table 5).

Table 5. Correlation family conditions and quick access

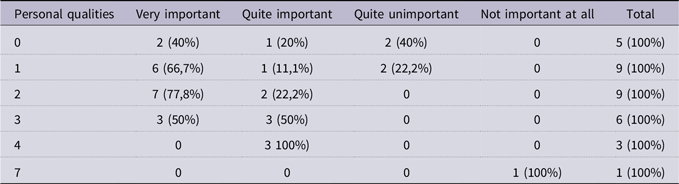

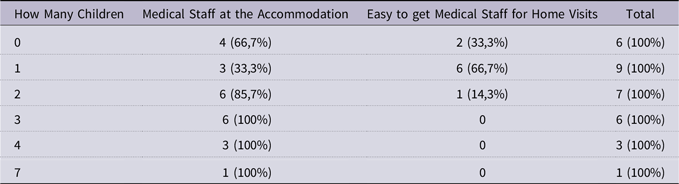

Testing on the variables of how many children you have and how important it is for staff to have the personal qualities you require, we found a significant association showing that people living with someone have a stronger opinion as to whether this is important or not χ²(15, N=33)=49,141, p < .000. People with several children tend to value personal qualities less than those with either no children or only one (Table 6).

Table 6. Correlation number of children and personal qualities

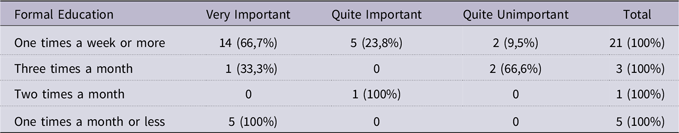

The variables of frequent visits by children and how important it is for staff to have a formal education show a significant association with people who enjoy frequent visits not valuing formal education as importantly as those who see their children less than three times a month χ²(6, N=30)=14,381, p < .026 (Table 7).

Table 7. Correlation children visit and formal education

One correlation we found was the one between how many children you have and whether or not the medical staff at the home are more important than how easy it is to get visits. A Chi-square test showed that those who have three or more children value the medical staff at their homes higher, χ²(5, N=32)=11,270, p < .046 (Table 8).

Table 8. Correlation number of children and medical staff presence

Our survey shows that the level of engagement has a slightly positive correlation with family status. People in better contact with their families, and who have more than two children, express more homogenous attitudes, while those with fewer than three children are more heterogenous in their attitudes. As regards the co-creation process, our study shows that family situation is correlated with engagement. People with only limited family contact are not engaged in the co-creation process, while those enjoying active family contact are more engaged.

The results indicate that the applicants consider the personalised aspects of the care situation to be more important than professional competence. In contrast to the generic aspects of the care situation, which are not valued as important, those aligning with subjective experiences and practical knowledge of the care situation are of major importance.

Interviews

To gain knowledge of how the employees make sense of the matching process, we conducted one focus group interview with three accommodation coordinators and their administrative manager, one focus group interview with two assistance caseworker, and one individual interview with one assistance caseworker. There were four support workers in total in the Seatown area, the last one having called in sick the day before the interview. We interviewed all the accommodation coordinators who worked at the Economic Administration Department. For the interviews, three overarching themes were identified as central to work at the municipality – matching, conflict, and goal fulfilment. These themes are all connected with the broader institutional arrangement relating to co-creation, e.g. norms, rules, and negotiation strategies (Vargo and Lusch, Reference Vargo and Lusch2016).

Our analysis of the interviews is structured according to the role the interviewees play in the matching process, and how they make sense of the negotiation procedure. Initially, the interviews with the assistance caseworkers were analysed, followed by the accommodation coordinators. This structure follows the application procedure at the municipality. Our analysis is based on the arguments put forward during the interviews: The objective here was to develop the three themes identified as central to the matching process, i.e. matching, conflict, and goal fulfilment.

Assistance caseworker: engagement and alignment

The first assistance caseworker we interviewed, we refer to as Maria. She discussed compliance with the requirement in the Social Services Act. This is principally based on an evaluation of the applicant’s capacity to meet his/her own care needs. While some applicants may necessitate a more comprehensive level of service than others, it is crucial to emphasise that the level of care remains consistent across all the retirement homes. Furthermore, the intangible aspects are also prioritised during negotiations between the elderly and the municipality. However, a significant distinction is to be made here inasmuch as the work of the assistance caseworkers is also subject to the provisions of the Social Services Act. To illustrate, Maria said:

It’s clear that every nursing home in the municipality has to offer the same level of care, there should be no differences. This is the level of care you need, and all the nursing homes here can offer it.

As for the operand resources, i.e. the tangible aspects, all the service facilities meet the same criteria. One issue that Maria focused on was how the initial contact is established, i.e. that a member of the family or extended family, or someone from social services, can register his/her concern if noticing or feeling that an individual is in need of care. However, Maria also stressed that:

If the person concerned doesn’t want it, then no investigation can begin. Only the customer him-/herself can apply: It has to come from that person. You can’t force somebody to do this. And, if I decide that you do not have this need, then you’ll be refused, but you’ll also have the right to appeal against this decision.

An investigation cannot start if the customer does not want it to but needs always take precedence and these are determined by the assistance caseworker. Hence, before matching and co-creation take place, needs must be defined by the assistance caseworker. Maria said as follows:

Previously, you could have three alternatives and wait until one of these became available. But that changed and it was said that if you are in need, extensive need, of care, then that need can be met anywhere. The offer you get is the place you get when you are at the top of the list and your need can be met anywhere. But if you really do not want to live in a place, then you’ll have the right to join a change queue, but then you’ll have to move twice.

The theme of engagement and feedback is a recurring topic. In this quote, Maria presents her reasoning around the discrepancies that may occur between identified needs and available resources, as well as the subsequent outcome when the value proposition is declined. If the offer is declined on grounds of dissatisfaction with the proposed location, then it may reasonably be concluded that the applicant is not in need of care. Maria said: “Every nursing home has to offer the same level of care. But the queue got too long…” Here Maria is talking about efficiency as regards managing the queue: They will have to try to shorten the waiting time. We asked Maria if all the applicants needed the same services, and what happens if there are special needs? She answered:

First, I decide if you have a need, and then I send a request to the coordinators. If there are any special needs or circumstances, I put these in the request, and they take that into account when looking for a place. We have specialised dementia homes, and we usually have a Silvia sister (see below) in each home. If she thinks that a client needs a dementia home, then we’ll arrange that.

A Silvia sister is specialising in cognitive disorders. In the last part of her interview, Maria said that even if waiting is prioritised, the elderly still need to be involved and engaged. She also said that: “…most things can be solved … you try to solve them in accordance with wishes and needs” and that “a lot happens behind the scenes. At the end of the day, you want the customer to be happy”. Maria then reflected on quality as a concept, and how she approaches that.

Quality depends both on the circumstances and on each individual case. We try to make it as good as possible for the customer, but also for the relatives of course. It is not too obvious what quality is. Not everyone can speak for themselves, there are people who have aphasia following a stroke, who cannot speak for themselves. Quality may mean one thing to one person and something else to another.

During the process of co-creation, both the interacting parties contribute resources via a reciprocal relationship (Vargo and Lusch, Reference Vargo and Lusch2016; Joiner an Lusch, Reference Joiner and Lusch2016; Nordgren et al., Reference Nordgren, Planander and Wingner Leifland2020). The interview with Maria suggests that efficiency does not necessarily entail co-creation. The applicant must be involved. But not everyone has the resources to co-create: What value will be co-created when “…not everyone can speak for themselves”? Quality is pragmatically co-created during a unique process that is dependent on the interacting parties.

Assistance caseworkers: discrepancies, alignment

The last interview was a group interview with two assistance caseworkers, Jenny and Monica, who also related to the level of need being a priority.

The formal application comes from the individual, but a notification can also come from a relative, a neighbour, or someone else. But, in the end, the consent of the individual must be included, that’s important. We must have some form of agreement. We always carry out home visits in order to meet the individual concerned. Notifications, on the other hand, are mostly by phone. Or letters and emails from other agencies: The police may have noticed something too. The hospital too. But it always ends up with us no matter who made the report.

Jenny then filled in: “Yes, many notifications come from relatives, about half I think.” Family and relatives play a significant role in notification, and also in the initial contact. Another aspect that they add is the anxiety associated with the waiting time, but not in the way one might imagine at the outset. Jenny also said that:

Once they’ve been given a place, things move very fast. And this can be somewhat distressing and linked to anxiety: They might feel that the process is being forced through. It may be felt that there is some conflict between what the municipality wants and what the individual wants.

The municipality wants things to move fast, but the applicant does not want to force the process through. So we asked how individual preferences are included, i.e. what people want. Monica said:

We write something in a box, there’s a textbox on the form where we can write that Asta has lived in Kingsvillage all her life and would like to keep doing so. But this will then end up on the coordinator’s desk…

There are forms for the applications as well as a formal and transparent way of matching and coordinating the different individuals with the available resources. The municipality is a bureaucratic organisation where efficiency and the rational use of taxpayers’ money are prioritised, a relationship that distances individuals from an organisation whose ultimate purpose is to serve them (Newman and Lawler, Reference Newman and Lawler2009). Jenny continued:

After we make our decisions, the housing agency then becomes responsible for placements. Then, we do not want to see too many changes or appeals, otherwise the customer will move in. Yes we have follow-ups but, unless something comes up, we have no further contact beyond that.

Monica is referring here to the law, i.e. freedom of choice is enshrined in law and the matching process is “set in relation to the Act governing freedom of choice”. She problematised this further:

Freedom of choice is thus reduced to only one alternative: Is that a choice? When you don’t get your choice at the first meeting, your first choice, this creates an unnecessary demand for change in the future that could be avoided.

Jenny added: “…the basic idea is that things should be right for you from the start”. Monica continued:

Yes, three months. We never exceed that, we focus really hard on that. I think it’s always been arranged within three months. But today the queue is shorter.

The matching process described here is more of a conflict-driven process. But they are aware of the ambivalence between freedom of choice and the scarce resources they have when matching, and that this freedom of choice creates: “…an unnecessary demand for change in the future”. Shorter waiting times do not always create value. When relating to the applicant’s life situation, a forced process between application and moving into a nursing home can be detrimental to value, even if it is a sign of efficiency.

Summary: assistance caseworkers

The caseworkers emphasise that alignment with the Social Services Act is crucial for ensuring consistent care across the nursing homes. They stress the importance of home visits and obtaining consent before investigations are made. They highlight the potential dissatisfaction arising from mismatches between needs and resources. They also address the conflict between the municipality’s desire for speed and the applicant’s preference for quality, alongside the tension between freedom of choice and limited options. They stress the importance of involving the elderly in decision-making, noting that quality is co-created during interactions. Furthermore they discuss the role of relatives in the process, but acknowledge that bureaucracy can distance individuals from the services intended to help them.

Accommodation coordinator: needs, intangible aspects, discrepancies, and engagement

We refer to the first accommodation coordinators we interviewed as Helena and Anna, with their manager being called Eva. The coordinators’ task is to align the level of care required by the applicants with the available resources. One of the coordinators, Anna, said: “The need is what is important and not the desire, i.e. what they want.” Helena, another coordinator, elaborated on this further:

If someone says no, the case will be sent back to the caseworker, who investigates whether or not there is a plausible reason why. If it is only due to the situation, that the customer does not want to be at that particular home, then the authorisation will be withdrawn and you can apply again. Because then, it will not be the need for care that is important, but other factors.

This quote demonstrates that the tangible aspects, or operand resources, are of lesser importance than the intangible aspects, or operant resources. The coordinators must reduce the length of the queue, but the elderly and their families want time to prepare for the move, which prolongs the queue. A fundamental aspect of the matching process is the difference between the actual care requirements and the individual preferences of the parties involved. To achieve the municipal objective, it is necessary to reduce the length of the queue as soon as possible. However, from the perspective of the elderly, additional time is required to make the preparations necessary for the move.

As posited by Vargo and Lusch (Reference Vargo and Lusch2004), value creation occurs through the reciprocal exchange of resources, i.e. that the elderly are engaged in the co-creating process. However, during the matching process itself, there may be some discrepancies between what the different interacting parties want and what is considered necessary. Manager Eva said that:

It’s actually like that quite often, that they apply and then say no to what’s offered because it doesn’t suit their relatives, when they go on holiday abroad and so on. But then it’s neither the location nor the nursing home that’s the problem, things can move very quickly and then people get cold feet when they do.

Anna filled in:

If you say no, you’ll lose your place in the queue and end up at the back of it again. But, when we removed the possibility of saying no, this shortened the waiting time a lot. So, now everyone gets a place after seven days and you move in after three months. We do as much matching as much as we can…

Helena, continued: “…and from having over a hundred people queuing, we now have less than forty”. During negotiations between the coordinators and the elderly, discrepancies are experienced in the co-creation process. Such a situation may be described as a disruption of the integration of resources.

A third area of concern is engagement and feedback. During the interviews, we investigated how they ensure the applicants are as satisfied as possible, even in instances where they are presented with a housing option that does not align with their preferences. Manager Eva answered:

…you can choose, but not completely freely. Whenever possible, there is a choice. You will, of course, get what you want if this is possible. But, if you move in to a place that you don’t want to stay in, you can join a more informal ‘change queue’. But if move in, they will usually stay.

Anna filled in:

There are many who apply for a change. This is mostly when you have a spouse nearby who has to be able to come and visit. Then, it won’t be good at all if your mother, father or husband moves to the other side of town, or far away. So, of course, we try to match things so they’re nearby.

Here two aspects emerged, i.e. discrepancies and engagement. In instances where none of the accommodation available corresponds to the applicant’s preferences within the formal matching chain, an informal way becomes available. Applicants may move in and then opt to join a change queue, with a shorter waiting time than the formal queue. This alternative approach enables the incorporation of the applicant’s preferences into the matching process itself, albeit using an informal pathway. A pragmatic matching of the available resources arises, and thus the co-creating process becomes tangible.

Summary: accommodation coordinators

The accommodation coordinators prioritise needs over wishes during the matching process, emphasising that the need for care takes precedence. They highlight the importance of the intangible aspects during matching, viewing care as personalised and relational. The discrepancies are significant between the municipality’s goal of reducing waiting times and the elderly person’s need for preparation time. They mention that applicants often refuse offers due to their personal circumstances rather than their need for care, but also that removing the option to decline an offer has significantly shortened the waiting times. They highlight the importance of engagement and feedback, including the informal ‘change queue’ for those wishing to move after they have settled in. These co-workers strive to match applicants with homes based on preferences such as proximity to family.

Discussion

The survey shows that family situation correlates with engagement: people with more than two children and in frequent contact with their family tend to be more engaged in the matching process. Three themes emerged from our analysis: the first theme is linked to an orientation towards intangible aspects such as need and availability in Sweden’s elderly care. This theme is linked to policies concerning aspects of the waiting time guarantee, which underscores the priority placed on fulfilling an individual’s need for care, over and above individual wishes. On the one hand, this focus has led to a reduction in waiting times for elderly homes in Seatown, while on the other, the user’s freedom of choice has been condensed somewhat into a single option. This observation is in line with Hardyman et al. (Reference Hardyman, Garner, Lewis, Callaghan, Williams, Dalton and Turner2022), Vargo and Lusch (Reference Vargo and Lusch2004: 2008), and Skålén et al. (Reference Skålén, Engen, Magnusson, Bergkvist, Karlsson, Russo-Spena and Mele2016), suggesting that a value-creation process is based on the active involvement of all the interacting parties, when resources are integrated. Value co-creation, however, is highly dependent on the social context in which the service is being provided. In our study, we found that this social context depends on expectations, and on how much these are taken into account during the matching of the resources available prior to the actual service being provided. Short waiting times are a priority for Seatown: however, the applicants are more concerned with aspects that are in line with their personal expectations. We also found that different expectations are linked to different groups: services are standardised but the demand among the elderly is very heterogeneous.

The second theme refers to the pragmatic alignment of resources. The actual co-creation process was described as indirect resource integration, a more informal process occurring when the applicants are queuing up for a change. In the second instance, resource integration is carried out by the accommodation coordinators, when providing the elderly with the possibility of changing homes.

The third theme revolves around value conflicts involved in the discourse of managerialism and efficiency. These value conflicts became evident in how the elderly wrote about aspects relating to both personal matters and the qualitatively different aspects of services, versus the views of managers and coordinators who viewed these qualitatively different aspects as unnecessary. In their view, all nursing homes meet the same level of standardised needs. Matching is about efficiency, controlling costs, and capacity, not so much about resource integration (Lydahl and Hansen Löfstrand, Reference Lydahl and Hansen Löfstrand2020).

While our sample is small, it represents a complete sample for the specific time period. Our aim is not to generalise but to gain insights from this particular case. However, the findings should be interpreted with caution due to the limited statistical power and range of perspectives.

Conclusions

In reference to the first research question, we conclude that the majority of applicants want individual and personalised services. The services wished for are those associated with subjective values, e.g. friendliness, integrity, good food, and staff presence. Applicants with closer connections with their families and children also had different expectations. Applicants who had higher expectations were those who had more than two children and who met these children often. Consequently, family is an important factor to consider when understanding the value-creation process in elderly care.

Regarding the second research question, we found that the municipal employees pragmatically match the elderly with the resources available. The case workers tend to adopt strategies aligned with a management discourse that excludes the possibility of co-creation. This discourse focuses on meeting basic care needs and adds no value to the service offering. The coordinators, on the other hand, have a more pragmatic approach, ensuring that the waiting time guarantee is met and offering the possibility of changing homes. Because the strategies are well-defined and regulated during the early stages, the narratives of the assistance caseworkers are typically tied to arguments about efficiency and waiting time guarantees. During the second phase, when the accommodation coordinator offers the possibility of changing homes, the strategies are more relaxed.

Our findings contribute to research into co-creation in health care in three distinct ways. Firstly, they show the lack of opportunity for co-creation during the matching process. The coordinators pragmatically and informally try to meet the expectations of the applicants. Secondly, they suggest that co-creation is important during the matching process because it recognises individual differences in the allocation of resources. A socially sustainable welfare system is based on egalitarian models of resource distribution, and thus a matching process that allows heterogeneity is consistent with a socially sustainable society. Lastly, people who have an active relationship with their relatives are more likely to become part of the co-creation process than people who live alone.