So severe and close restraint

In 1665, an anonymous pamphlet was published in England. This was the time of the Great Plague of London, which may have killed up to a quarter of the city’s population. The authorities imposed extreme measures to stop the spread of the disease, including moving the sick to “pest-houses” and quarantining for forty days in their homes those who had contact with them. The pamphlet’s author argues that this amounts to abandoning the sick and their families; it is counterproductive because those who can, will just flee the city in response, spreading the disease to the countryside; and it causes immense economic and social harm, especially among the poor, leading to unemployment, extreme poverty, and more domestic violence. The anonymous writer concludes that less extreme measures would have been more beneficial: “[A] liberty of fresh Aire, and access of such as are willing to visit their sickfriends, may be so regulated and limited as not to spread the Infection, and I am sure will save the lives of Hundreds, who by so severe and close restraint are little better then Murther’d, or buryed alive.”Footnote 1

The predicament of Londoners during the Great Plague should sound familiar. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries imposed similarly extreme measures. On January 23, 2020, the Chinese government in effect boarded up the whole city of Wuhan, where the SARS-CoV-2 virus first appeared. All public transport was closed, people could enter or leave the city only with permission from the authorities, and they were told to stay at home and leave only for shopping and unavoidable trips. The lockdown was soon extended to the rest of Hubei province and other cities, confining tens of millions of citizens to their homes. In March, Italy imposed a similar nationwide lockdown as the epicenter of the pandemic moved to Europe. People were supposed to leave their homes only for groceries, work, and health care. Beginning in August, residents of Melbourne in Australia were banned from traveling further than five kilometers from their residence, only one person per household was allowed to go out for getting essential groceries, and outdoor exercise was permitted for no more than one hour. Public gatherings were limited to two people. The restrictions remained in place until the end of October.

It has been estimated that more than half of the world’s population was in some sort of lockdown in the spring of 2020.Footnote 2 Further restrictions followed with subsequent waves of the pandemic. It was not until toward the end of 2022 that China began to ease its “zero-COVID” policy. Whether in London, Lombardy, or Wuhan, people faced severe restrictions of freedom of movement, freedom of association, and other civil liberties for extended periods of time.

The restrictions have undoubtedly saved lives and slowed the transmission of the virus.Footnote 3 However, they have also caused massive harm through loss of income, social isolation, domestic violence, mental health problems, and suicide.Footnote 4 Some of these harms are likely to extend far into the future. In particular, children and adolescents missed out on school and social development for months or more, putting them at risk of lower educational achievement, later difficulties with social integration, and worsened life prospects. The risks were exacerbated for those who were already socially disadvantaged.Footnote 5

At the same time, SARS-CoV-2 had minimal risk of severe illness or death for children, adolescents, and young adults, whereas it had orders of magnitude higher risk for those over sixty-five.Footnote 6 While the elderly faced a high, immediate risk of great harm or death, the young faced minimal immediate risk, but higher long-term risks of more diffuse, less readily identifiable, nonfatal harms. It is not an exaggeration to say that the world responded to the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020 by a massive redistribution of risk from the old to the young.

This raises the question: How should we evaluate policies that redistribute risks of harm between different groups in order to protect public health or achieve some other desirable social objective? In particular, how can we make trade-offs between minimizing mortality and morbidity, on the one hand, and avoiding other sorts of social and economic harm, on the other? How should we balance risks to life and risks to livelihoods?

The traditional approach to making such trade-offs is to employ some version of cost-benefit analysis to add up and compare the costs and benefits of different policies—in the sort of cases that I am interested in, nonpharmaceutical interventions such as lockdowns, quarantines, compulsory mask-wearing, and other forms of social distancing. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, however, cost-benefit approaches have come under fire from different directions. Some of the objections are technical. Others are ethical. I will set the technical objections aside here and focus on the ethical issues.Footnote 7

The most important ethical objection targets the fact that cost-benefit analysis is aggregative, involving the addition of costs and benefits and evaluating policies by their overall sum. The problem with aggregation is that it countenances sacrificing some people’s interests for the greater benefits of others. This means, argue critics, that cost-benefit analysis fails a basic test of morality, namely, the requirement that actions and policies be justifiable to everyone who is affected. Similarly to other aggregative ethical theories, cost-benefit analysis violates the separateness of persons.Footnote 8

It is not all bad news, however, continues the objection. In the past few decades, philosophers have developed an alternative, nonconsequentialist moral theory that can be used for ranking different policies, including responses to public health emergencies. That theory is contractualism, which is based on the idea that policies must be justifiable to all rather than determined by the balance of expected harms and benefits. It is a theory that is well-suited for assessing trade-offs between lives and livelihoods.

Undoubtedly, cost-benefit analysis has its problems, some of which I discuss below. But does the contractualist alternative offer enough advantages to warrant discarding it? In this essay, I argue that the contractualist approach also runs into difficulties. In particular, I raise two problems. First, I note that most contractualists are not against all forms of aggregation. They allow the aggregation of harms and benefits to different people as long as all the harms and benefits are relevant in the context of the comparison. For instance, some risks to “mere livelihoods” may not be relevant when lives are at stake. However, I show that this leads to a dilemma. In a certain important kind of case, contractualism either (a) allows aggregation, even though the harms and benefits that are aggregated are irrelevant, or (b) it prohibits aggregation at the cost of failing to be justifiable to everyone who is affected. Either way, it seems, contractualism itself violates the separateness of persons. If it takes the first horn of the dilemma, it sacrifices the interests of some people in avoiding grave harms for the interests of a greater number of other people in avoiding small harms, just like aggregative ethical theories do. If it takes the second, it completely disregards the interests of a greater number of people in avoiding substantial harms for the interests of a smaller number of people in avoiding only slightly greater harms, regardless of how many people may suffer the substantial harms and even though the harms are nearly equal.

The second problem sprouts from the first. Because of the priority it tends to give to lives over livelihoods, contractualist policy evaluation tends to ignore the presumption in favor of liberty, a basic requirement of public health (and other) policies. It has an in-built tendency for policies that involve more severe liberty restrictions. These problems, I conclude, give us a reason to be wary of contractualism. Despite its well-known problems, it is not yet the time to give up cost-benefit analysis.

The next section presents an overview of cost-benefit analysis. I then introduce contractualism and its application to policy evaluation. I proceed to present the dilemma for contractualist aggregation and describe contractualism’s conflict with the presumption in favor of liberty before offering some concluding remarks.

Cost-benefit analysis

Cost-benefit (or benefit-cost) analysis is a tool for evaluating and comparing different policies in monetary terms. Typically, it is used for regulations that aim to improve safety, decrease fatalities, or reduce the risk of fatality or injury, whether at the workplace, on the market, in the environment, and so on. Regulations put restrictions on liberty and those restrictions have economic costs. By quantifying the benefits in monetary terms, we can determine whether the benefits exceed the costs. This approach can directly be applied to public health, including responses to public health threats such as epidemics and pandemics.

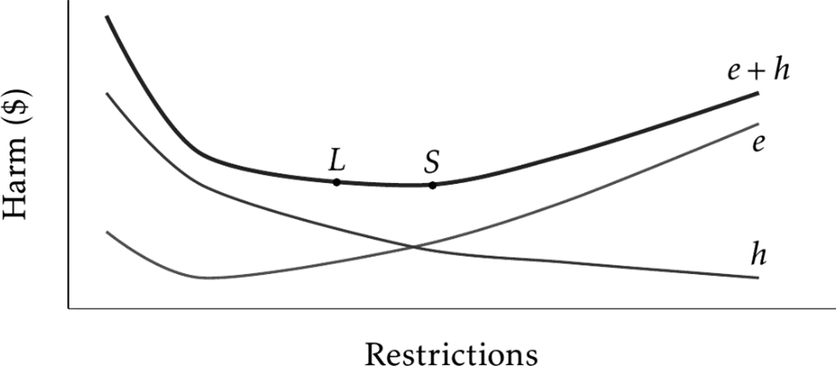

Figure 1 can help guide our thinking. Suppose that we order possible responses according to the severity of the restrictions they involve, going from information campaigns, contact tracing, and selective quarantines to compulsory mask-wearing, the prohibition of public gatherings, travel bans, curfews and lockdowns, and so on. For simplicity, I assume that we can arrange these measures on a continuum from least restrictive to most restrictive. This is a crude simplification because measures can vary along numerous dimensions, for instance, by how long they last, whether everyone or only some groups are affected, the way the burdens are distributed among different groups, and so on. I also assume that we can measure the harm associated with each policy on the continuum on the vertical axis in monetary terms, perhaps in terms of loss of gross domestic product (GDP) or some other measure of economic output.

Figure 1. Adding up Health Losses and Economic Costs.

Thus, in general, as increasingly severe restrictions are introduced, the economic costs increase. The economic costs are represented by the curve e on Figure 1. When drawing the figure, I also assumed that if the government introduces only minimal or no restrictions at all, that in itself can have a negative economic effect through people voluntarily restricting their activities (as shown by the “kink” in curve e at its lower end).

The curve h represents the monetary value of health losses. It decreases as increasingly severe restrictions are introduced. The more restrictions are put in place, the fewer people will lose their lives or contract the disease, the less overwhelmed hospitals will be and thus those who do become sick can be treated more successfully, the less the virus is going to be able to mutate into more dangerous variants, and so on. Although represented in terms of money, curve h shows the harms to health, given different policies.

Once we have the data for mapping out the economic and health costs of different policies, we can add them up. The aggregate costs are represented by the curve e + h. We can now identify those policies that are the most promising trade-offs between economic burdens and health losses by looking for the minimum values on e + h. For instance, the most promising trade-offs might be the policies whose overall costs are represented by points L and S. If the public health emergency involves threats to life, we have now identified L and S as the most promising trade-offs between lives and livelihoods. They minimize overall harms.

I have not yet said anything about how to determine the values of curve h. This depends on the version of cost-benefit analysis that we choose. For instance, on the “cost-of-death” approach, we would represent the value of each death by the amount of lost future earnings of the person who dies plus the medical costs of treating the person before their death. Thus, given a particular response to the threat, the health losses are equated with the overall lost earnings and health-care costs of every person who would die.

Needless to say, there are numerous problems with this approach. Most obviously, it equates the value of a person’s life with the income that the person would have had, had he not died. It places a higher value on the lives of people with a high income or those who can be expected to have a high lifetime income compared to those who have a low income or can be expected to have a comparatively low lifetime income.

A more standard approach is based on the value of statistical life (VSL). The basic idea of VSL is that we can put a monetary value on the reduction of mortality risks in a certain range (typically, risks of death between one in ten thousand to one in one million) on the basis of how much hazard pay workers are paid in risky jobs or by using responses to studies involving hypothetical choices (called contingent valuation studies). Suppose that workers are paid annually an additional $900 for a job that has an excess mortality risk of one in 10,000 and an additional $90 for a job that has an excess mortality risk of one in 100,000. Thus, we can say that the value of a statistical life is $9 million. If we expect 100,000 people to die in a pandemic, then the overall loss in terms of statistical lives will be $900 billion (roughly, four percent of U.S. GDP). In the U.S., real-life estimates of the value of statistical life range between $9 and $11 million. In Canada, they are around $5.6 million; in Australia, $3.5 million; and in the U.K., $2.1–2.4 million.Footnote 9

One problem (among many) with the VSL approach is that it does not take into account the quality of life, only its quantity. A measure that overcomes this shortcoming is the quality-adjusted life year (QALY), used mainly in health-care technology assessment. QALYs combine the duration of the harm with its impact on quality of life. Each year spent at a certain (health-related) quality of life is given a weight between zero and one, with one representing perfect health and zero representing an outcome that is no better than death. Thus, one QALY can represent two years of life at quality of life level 0.5, four years at 0.25, and so on. Death is represented by the amount of healthy life expectancy—that is, expected years of life weighted by their quality—that the person would have had, had he not died.Footnote 10

Different health-care systems value QALYs differently.Footnote 11 In response to a public health emergency, societies can decide how much they are willing to pay for averting the loss of one QALY. Thereafter, they can measure the health losses in cost-benefit analysis by using their valuation to arrive at the overall monetary value of QALY losses on different policies.

These are different ways that cost-benefit analysis can be used to select the most promising trade-offs between health harms (including loss of life) and economic losses. Despite their differences, all of these approaches are aggregative. They involve the summation of the monetary value of harms to health and economic harms and they aim to minimize overall harm. Like other aggregative methods, they are vulnerable to a common objection, namely, that they ignore the distribution of harms. It makes no difference whether the harms accrue to the better-off or to the worse-off.

There are proposals to address this problem. For instance, societies might decide to pay more for protecting those who are more vulnerable in order to reduce disparities in health outcomes or they may apply different values of statistical life to different groups. I will leave these proposals unexplored here, as the motivation for the contractualist alternative is rooted in a more fundamental objection.Footnote 12

Nevertheless, a couple of further points are worth noting. Public health measures, including lockdowns and other forms of social distancing, create conflicts between public health and civil liberties. On the one side, there are benefits in terms of number of lives saved, cases of illness prevented, disabilities averted, and other health gains. On the other side, there are losses due to restrictions on freedom of movement and association, the use of private property, the elimination of certain choices, and so on. I have suggested that cost-benefit analysis can be used to resolve such conflicts. It can identify trade-offs that maximize public health benefits and minimize the burdens of liberty restrictions.

However, cost-benefit analysis captures the “liberty” side of the trade-offs by counting the economic costs. Plausibly, not all “costs” or restrictions of liberty can be captured in economic terms and there might be some economic costs that do not reflect any loss of liberty. This is, therefore, another simplification. The best we can do is to try to take into account as many kinds of cost as possible. Trade-offs between public health and civil liberties must be indirect.

Notice, however, that this problem is not unique to cost-benefit analysis. Any trade-off method must be able to compare the advantages and disadvantages of different policies. For instance, the contractualist alternative, to which I will turn shortly, compares the burdens that people have to bear under different policies. In order to do this, it must be able, with some precision at least, to quantify the size of those burdens. In this respect, it faces problems similar to those of cost-benefit analysis.

Why should these trade-offs be directed at liberty? Why must they be indirect? In democratic societies, civil liberties are not merely another set of values. They are fundamental in a way that other values, such as economic well-being or even public health, are not. There is a presumption in favor of civil liberties, such that other social goals, including the protection of public health, must be pursued through policies that respect civil liberties by employing the least restrictive and intrusive means.Footnote 13 Whenever possible, public health measures should provide information, enable choice, and shepherd it with incentives or disincentives; they should restrict or eliminate choice only when failing to do so would have very serious bad consequences. When public health and civil liberties must be put on the scale, a heavy thumb must be placed on the side of liberty.

Cost-benefit analysis can easily accommodate the presumption in favor of civil liberties. To see this, consider again Figure 1. Policies L and S are both promising trade-offs between public health and economic harm. But policy L—I will call it the lax policy—involves less severe restrictions on civil liberties than does policy S (the strict policy). Policymakers can easily determine that L has an advantage in this respect. In fact, the way I drew the figure, L has slightly greater overall harm than S. Yet, because of the presumption in favor of liberty, we might decide that, all things considered, L represents a better trade-off than S. Cost-benefit analysis helps us bear in mind the presumption in favor of liberty.

Justifiability to each person

Cost-benefit approaches share a common feature; they are aggregative. Aggregative theories have long been criticized because they are insensitive to distribution. As long as the overall benefits are greater, it does not matter how the costs and benefits are distributed between the better-off and the worse-off. Defenders of aggregation can try to meet this objection by giving more weight to the benefits of the worse-off or by taking the value of equality into account some other way. As I have already said, though, this is not the objection I am interested in and I will set it aside.

In recent years, a different objection to aggregative theories has gained currency. According to this objection, aggregative views miss a basic point about morality, namely, any action or policy that might affect individuals must be justifiable to all from each person’s own individual standpoint—in particular, from the standpoint of those who must bear its burdens—rather than from an aggregate social perspective that takes into account only the overall net of benefits and harms. When trade-offs are unavoidable, they must be justifiable to all.

One way of putting the point is to say, with John Rawls, that aggregative approaches violate the separateness of persons; they ignore the basic moral distinction between trade-offs within the life of one person and trade-offs between different people.Footnote 14 In intrapersonal trade-offs, a person’s burden may be compensated by a greater benefit to her at some other time; in interpersonal trade-offs, one person’s burden cannot be compensated by benefiting another person. Those who have to bear the burdens have reasonable complaints even against a policy that maximizes overall benefits. The greater the burden, the stronger their complaint, and therefore, the greater the weight it should get in moral justification. A morally justified policy minimizes the burdens that anyone has to bear. It is the trade-off against which only the weakest complaints can be lodged.

The basic idea can readily be illustrated by Thomas Scanlon’s famous Transmitter Room case.Footnote 15 A worker suffers an accident and he can be helped only if the transmitter is turned off for fifteen minutes. However, a World Cup match is in progress and millions of people are watching it. Interrupting the transmission would disrupt their enjoyment. Because there are so many viewers, their aggregate loss would far exceed the worker’s pain. Nevertheless, the right course of action would be to pause the transmission. The suffering of the worker exceeds the loss of enjoyment to any one of the viewers. Justifiability to each person requires that the complaint that he can make from his individual standpoint is compared to the complaints that each other person can make from their own standpoint. The worker’s complaint if the transmission is not paused is stronger—has greater moral weight—than is the complaint of any of the individual viewers if the transmission is paused. Therefore, the right course of action is to interrupt the transmission.

This example cannot directly be applied to the sort of trade-offs that I am interested in here. For one thing, the worker is an identified victim who needs rescuing right now. Moreover, he is presumably in the transmitter room in an official capacity and we have special duties to people when they suffer harm as part of carrying out their official duties. Public health policies, in contrast, concern populations. Typically, you need to consider future harms and benefits to presently unidentified individuals. You work with statistical lives. Arguably, there is a moral difference between an action that will cause harm to a known person and an action that can be expected to harm some person among many when both actions have the same overall benefits.Footnote 16 In public health, we are almost always concerned with risk factors rather than certain harms.

Contractualist policy assessment can accommodate these features. It can consider the complaints of representative individuals. If a policy affects members of different social groups, it can look at what the “typical” complaint of the representative member of each group would be. That is, as Scanlon puts it, contractualists consider generic reasons. Because we cannot know who will be affected and in what ways, “our assessment cannot be based on the particular aims, preferences, and other characteristics of specific individuals.” Therefore, “we must rely instead on commonly available information about what people have reason to want.”Footnote 17

Contractualists also distinguish between complaints based on the actual burdens and benefits of an action or policy and its expected burdens and benefits. A person’s complaint might be based on the fact that she suffers a loss if some policy is implemented or it might be based on the prospect of suffering a loss, combining its probability and magnitude. In the latter case, the person’s complaint is based on the fact that an action or policy exposes her to a risk of harm that she prefers to avoid.

These two conceptions of complaints lead to different versions of contractualism. Ex ante contractualism considers complaints as a function of the possible harm, discounting it by its probability; ex post contractualism considers complaints as a function of the harm, regardless of its probability.Footnote 18 Given public health’s focus on risk factors, I will assume that contractualists want to adopt the ex ante version of the view. At the very least, this allows me to sidestep some difficulties of interpreting the ex post view. Thus, I take it that contractualist policy assessment works with the complaints of representative individuals from the ex ante perspective.

Let us consider a simple example. In order to slow the transmission of a virus in the population, the government can choose between two policies. On the lax policy, minimal restrictions will be introduced, including mask-wearing and some limits on the size of public gatherings, but no closure of schools and businesses. On the strict policy, a complete lockdown will be introduced. Schools and businesses will be closed, public gatherings prohibited, and people will be able to leave their home only for essential trips.

The government knows that different age groups in the population face different levels of risk and harm. If they become ill, the elderly face a high risk of mortality, but their risk of infection is minimized if the strict policy is implemented. In contrast, the disease poses a negligible mortality risk for young people. If they are infected, at worst they end up with flu-like symptoms for a few days. However, under the strict policy, young people will have to miss out on social life and staying at home will inconvenience them in some minor ways. For instance, they will not be able to get their morning coffee from their favorite coffeehouse chain. Thus, the strict policy would cause some minimal loss of well-being for them.

How would a contractualist approach to policy assessment rank these two policies? It would begin by enumerating the complaints that members of affected groups can make. The elderly can complain that the lax policy would impose a high risk of mortality on them. The young can complain that the strict policy would impose some risk of very small harm on them from everyday inconveniences. Plainly, the elderly have a stronger complaint, as they face a greater burden under the lax policy than young people do under the strict policy. Hence, the government should implement the strict policy.

On this procedure, each person’s perspective is taken into account. No one’s interests are sacrificed for the sake of benefiting others. It is true that not everyone’s interests can be realized, as there is conflict of interests between the young and the old, but the young cannot complain that their interests were simply ignored. They were compared to the interests of the elderly and it was found that old people would have to bear greater burdens if the policy that did not favor them was implemented. Moreover, the benefits and burdens are not balanced between different persons as if they were benefits and burdens within a single life. Each person’s benefits and burdens were taken into account and compared to those of others. The chosen policy is justifiable to all, from each person’s own standpoint. Contractualist policy assessment respects the separateness of persons.

Importantly, the procedure is insensitive to aggregative considerations. It does not consider the number of those who would be benefited or burdened by the strict and lax policies. It does not matter whether there are more young people who would be inconvenienced by the strict policy than old people who would be protected by it. Contractualist policy assessment is nonaggregative.

Actually, there is a complication here. That is because many contractualists want to allow that in some cases the number of those who are affected by a policy can make a difference. Suppose that, under the strict policy, young people are not merely inconvenienced in minor ways. There is a risk that their social isolation will lead to severe mental health problems later on and missing out on their education might have a lifelong negative impact. Suppose also there are more young people who are affected negatively by the strict policy than old people who are affected negatively by the lax policy. Even though the possible harm to each young person is smaller than the possible harm to each old person, both are serious harms and having to bear them constitutes a heavy burden.

Under such conditions, argue many contractualists, it is permissible to aggregate. Both the young and the old have strong complaints against the policy that is against their interests. Although the complaints of the young are individually somewhat weaker than the complaints of the old, there are more young people who would be adversely affected. In such cases, the numbers can count. However, because this applies only under special configurations of complaints, contractualism only allows partial (or limited) aggregation.Footnote 19

What kinds of configurations of complaints make aggregation permissible? To see the answer, consider an example from Stephen John and Emma Curran, two defenders of contractualist policy assessment. Suppose that a cost-benefit analysis concludes that the aggregate benefits of a strict social distancing policy are greater than the aggregate benefits of a lax policy. Just before the government makes the final decision, though, a representative of a coffeehouse chain shows up and convincingly shows that the aggregate frustration that many people would suffer if they were not able to buy their morning coffee exceeds the difference between the benefits of the strict policy and the lax policy. Once the harms of the many instances of slight frustration of not being able to get coffee in the morning are subtracted from the benefits of the strict policy, the net benefits of the lax policy become greater.

But this, argue John and Curran, should not matter morally. Getting your morning coffee “is not morally significant enough to enter the conversation when costs like death are on the table.”Footnote 20 It is the comparative significance or relevance of complaints that makes the difference between permissible and impermissible aggregation. Not being able to get your coffee or watch the World Cup game for fifteen minutes is a harm that is irrelevant compared to the harm of severe pain or death. No matter how you increase the numbers in the former case, aggregation remains off the table. However, once the burdens become sufficiently similar, it begins to matter how many people must bear them. As Scanlon puts it:

If one harm, though not as serious as another, is nonetheless serious enough to be morally “relevant” to it, then it is appropriate, in deciding whether to prevent more serious harms at the cost of not being able to prevent a greater number of less serious ones, to take into account the number of harms involved on each side. But if one harm is not only less serious than, but not even “relevant to,” some greater one, then we do not need to take the number of people who would suffer these two harms into account in deciding which to prevent, but should always prevent the more serious harm.Footnote 21

When the strict policy causes young people only minor inconvenience—say, not being able to get their coffee in the morning from their favorite coffeehouse chain—then their harm is irrelevant, given that the elderly face a risk of serious illness or death. This is so regardless of how many young people would suffer the inconvenience. In contrast, when the strict policy comes with the risk of social isolation that causes severe mental health problems and missed schooling that causes lifelong difficulties, then the harm is relevant. If sufficiently many young people face these harms, it is permissible to choose the lax policy that favors them. Whether contractualism allows aggregation depends on the relevance of harm.

In sum, contractualist policy assessment is committed to the following two claims:

-

(1) When a person has to suffer a severe burden, then it does not matter how many people would have to suffer a comparatively minor burden.

-

(2) When a person has to suffer a severe burden, then it does matter how many people would have to suffer a comparatively major, though smaller, burden.

Thus, when a person faces the risk of death, it does not matter how many people face a similar risk of not being able to buy their morning coffee. However, when a person faces the risk of death, then it does matter how many people face a similar risk of lifelong loss of income and mental health problems. The latter is relevant to the harm of death, while the former is not. Contractualist policy assessment is committed to the idea of irrelevant harms and benefits.

Are there irrelevant harms and benefits?

Consider now the following example. As before, the government must decide whether to introduce a lax or a strict social distancing policy in response to a public health threat. If the lax policy is implemented, old people face a high risk of death. If the strict policy is implemented, their risk is completely eliminated. There is a greater number of young people. Under the lax policy, they do not face any risk of harm. Under the strict policy, they will be socially isolated and fall behind on their schooling. Their risk of suffering some minor harm due to these causes is similar in magnitude to the risk to old people under the lax policy.

But there is a catch. The small harms to the greater number of young people are going to be recurring. Each year, they will suffer some mental health problem and, each year, they will lose a little bit of income because of the schooling that they missed out on during the implementation of the strict policy. The overall magnitude of these recurring harms is comparable, though still smaller, than the harm of death old people face under the lax policy.

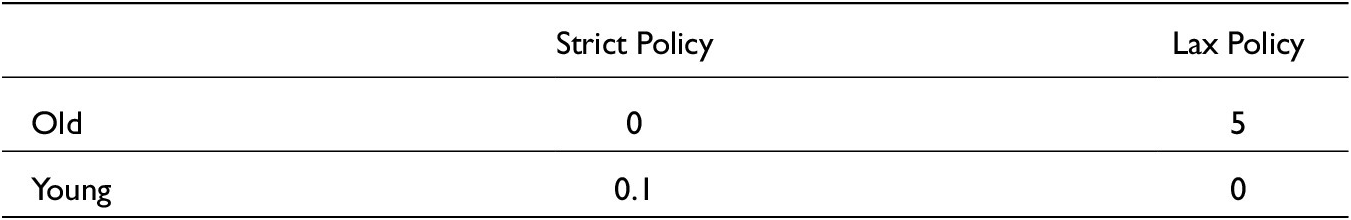

It might help to put some numbers on the harms (purely) for illustration (see Table 1). The numbers represent the magnitude of the harm that people would risk under different policies. Thus, if the lax policy is chosen, the old have a risk of losing five units of well-being. If the strict policy is chosen, their risk is completely eliminated. In addition, under the strict policy, the young have a comparable risk of losing 0.1 units of well-being this year; under the lax policy, their risk is completely eliminated. However, the harm of 0.1 is recurrent; it will affect the young in each of the next, say, forty-nine years, including this one.Footnote 22

Table 1. The Burdens of the Young and the Old

Now, let’s stipulate that the harm of 0.1 is irrelevant to the harm of 5. (Considering its magnitude, it certainly seems to be, as it is fifty times smaller.) If examples make the point more vivid, imagine that the 0.1 represents a smaller annual income, an episode of moderately severe depression recurring each fall, or whatever seems the relatively right amount of harm to you. Whatever the harm is, any one episode of it is irrelevant to the harm of death. As contractualists might put it, it is not morally significant enough to enter the conversation when harms like death are on the table.

The problem for the contractualist is straightforward. The old have a very strong complaint against the lax policy. Unless the strict policy is introduced, there is a considerable risk that they will contract the disease and die before next year. The young have a much weaker complaint against the strict policy. With comparable risk, they might suffer a small harm. Moreover, by assumption, that harm is irrelevant. Hence, the young’s complaint should be set aside. The government should implement the strict policy.

But if young people do suffer the harm, it will recur periodically far into the future. Once all these small harms are aggregated—recall that contractualists have no objection to intrapersonal aggregation—the accumulated harm to any young person is almost equal to the harm that any old person might suffer now. Therefore, the lax policy should not be off the table. Because, by assumption, there are more young people than old people, the government should implement the lax policy.Footnote 23

It seems to me that both of the policies are objectionable from the contractualist’s perspective. If the lax policy is chosen, she lets a large number of irrelevant harms outweigh a very serious harm. If the strict policy is chosen, she chooses to put a comparable burden on a greater number of people.

Let me consider some responses that the contractualist might try in order to find her way out of this dilemma. Consider first the discounting response. Contractualists might argue that harms in the future should be discounted and the present complaints that are based on them should be proportionally weaker. This would be a case of “pure” discounting, that is, harms that are further in the future would count for less just because they are further in the future, not because such harms tend to be less likely.Footnote 24

Even if pure discounting was morally acceptable—which is far from clearFootnote 25—one obvious problem with this response is that nothing ensures that discounted harms do not still make for stronger complaints. The young people in my example could be imagined having to suffer the recurrent harm for sufficiently more than fifty years (or the same harm every week or month rather than once a year) and therefore even their complaints based on discounted harms may remain stronger. Discounting offers no way out of the dilemma.

Next, consider the adaptation response. Contractualists might point out that there is an important difference between the risk of death in the short run that the elderly face if the lax policy is chosen and the risk of long-term, accumulated losses that the young face if the strict policy is chosen. Over time, the young can adapt to their losses such that their subjective well-being over their whole lifetime decreases much less than it appears from the present perspective. For instance, even though their lifetime income will be lower, they are very likely to change their expectations and derive no less satisfaction from it. Adaptation is an important coping mechanism in the face of permanent loss. For obvious reasons, the elderly would not be able to adapt to their loss if the lax policy is chosen.

I can think of several objections to this response. First, it is not clear why the harms that go into determining the young’s complaint should be based only on subjective well-being. Even if young people adapt to their lower lifetime income (or the loss of their favorite coffeehouse chain), it remains the case that they will end up materially worse off with respect to their income (or coffee). Why should that not be relevant to determining their complaints?

Second, it is debatable whether adaptation is always admirable. You can adapt to adversity by modifying your values and adopting new, worthwhile aims, but you can also adapt by lowering your expectations and learning to get by with diminished achievements. A sudden illness or disability can make you more deeply appreciate personal relationships and place less value on professional achievement, but it may also make you withdraw from others and spend your time with trivial pursuits or shallow entertainment.

Third, adaptation is not always a possibility. Some conditions—notably, some forms of mental illness—are impossible to adapt to. If the young will suffer from a transient depression each fall, they will not be able to adapt to it. Some harms therefore remain relevant, even if the adaptation response is successful.

Fourth, there is no reason to accept that the complaints of the young should be based on their “post-adaptation” well-being. Contractualists claim that their view is preferable to its rivals because it is able to take into account the objections or complaints that any affected party can make from their own perspective. The choice between the strict policy and the lax policy needs to be made now, taking into account the pre-adaptation perspective of the young. From this perspective, their loss is only slightly smaller than the loss of the elderly. Why should it make a difference that they might come to view it differently in the future?

Fifth, even if all the previous objections can be met, it still seems wrong to impose the burdens of a policy on a group of people for the reason that they can adapt to those burdens.

Here is a final response that the contractualist might consider. She might begin by reminding us of an important point about cost-benefit analysis, namely, that it is a tool for policy evaluation only, not a full moral theory or decision-making method in its own right. No one suggests that it should be used exclusively to make trade-offs between different policies. It can help us identify the most promising trade-offs, but policymakers must choose between them using additional moral principles. For instance, as I have already suggested, it may be combined with the presumption in favor of civil liberties to choose trade-offs that involve minimal liberty restrictions.

Similarly, contractualist policy evaluation need not be the full picture. In the present example, for instance, the contractualist can suggest that there is an important difference between the harms that may befall the old and the young. While the harms to the old are immediate and noncompensable, the harms to the young are extended in time and can be later compensated. Thus, the strict policy should be chosen, but the young should be compensated in the future for the burdens that they might have to bear. Their complaint should be taken into account, as it were, outside of the contractualist procedure of policy evaluation. Let us call this the compensation response. Footnote 26

One thing to note is that the compensation response amounts to giving up the idea that there are irrelevant harms and benefits. For if even small harms can support complaints when they accumulate through life, they are not off the table when life and death are at stake. They may not add up to outweigh risks to lives, but they may add up enough to support claims for compensation. Once this is conceded, a lifetime of a smaller annual income, a seasonal depression in the fall, or the lifelong loss of morning coffee from your favorite coffeehouse chain (which has gone out of business during the strict lockdown policy) all become relevant.

In sum, none of these responses helps the contractualist find a way out of the dilemma.

One might ask: What causes the dilemma? Recall that contractualists allow trading off lifesaving for other benefits only when there is a greater number of people who would otherwise suffer a comparable, though slightly smaller harm. They do not allow any trade-offs regardless of the numbers when others would suffer only minor harms. Their view is motivated by the intuition that there are some harms and benefits (headaches, coffee, and so on) that are irrelevant when it comes to risks to life.

But this intuition is ambiguous. On the one hand, if it is motivated by the nature of the harms and benefits in question (for example, headaches and coffee cannot be compared to life), then contractualists have to reject trade-offs when small harms and benefits accumulate through time in a life and their overall value becomes comparable to loss of life, even though they have no objection to intrapersonal aggregation. On the other hand, if the intuition is motivated by the relative magnitude of the harms, then contractualists cannot object to trading off lives for livelihoods even when the livelihood side of the ledger is compiled from many minor harms and benefits. To determine what sort of complaints or claims these small harms and benefits support, they have to engage in the same sort of aggregative calculations that they object to in cost-benefit analysis.

How contractualism conflicts with liberty

If some harms and benefits are irrelevant and off the table, then contractualism will have difficulties accommodating the presumption in favor of civil liberties. To see this, let us look at a proposal for using contractualism in public health emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Its defenders claim that one key advantage of the contractualist approach is that it is able to distinguish between vectors and victims: those whose activities endanger others and those who must face risk of harm because of the activities of others. In a pandemic, everyone is both a potential vector and a potential victim. If you are contagious, you might impose a mortal risk on others; if others are contagious, they might impose a mortal risk on you. Thus, your liberty may be restricted for the sake of the defense of others and their liberty may be restricted for the sake of your defense. As a result, the restriction of liberty becomes the default position.

In their defense of the contractualist approach for ranking pandemic response policies, John and Curran make exactly this point: “[I]f it is ethically permissible for each person to be restricted in her movements, it is ethically permissible for all. Taking the perspective of self-defence when discussing lockdown policies implies an ethical baseline of a highly restrictive universal lockdown.”Footnote 27 As a result, they argue, we must “contract our way out” of the most liberty-restrictive forms of social distancing.

Contrast this, they argue, with other public health measures, such as cancer screening. Suppose it is found that a cancer-screening program has a favorable balance of costs and benefits for some group in the population, even taking into account the costs of compelling people to participate. Yet, John and Curran argue, it would be wrong to follow cost-benefit analysis here. Failing to attend cancer screening does not harm anyone else. Unlike in the pandemic case, the people who the screening program targets are not potential vectors. Cost-benefit analysis is insensitive to this difference.

The immediate response, as I have already mentioned, is that no one proposes cost-benefit analysis as a complete theory of policymaking or as the only input to making trade-offs. The presumption in favor of civil liberties provides a strong consideration against making the screening program mandatory. (It might be that in some cases, such as mandatory seatbelt laws, the population health benefits outweigh the presumption.) In any case, it is not clear that contractualism can avoid the problem. Recall Scanlon’s point from above that contractualist policy evaluation is based on the generic reasons of representative individuals rather than the particular preferences of specific persons. If the benefits of a screening program for representative individuals support sufficiently strong generic reasons, it is not clear why contractualists would not make it mandatory, regardless of the preferences of specific individuals.

More importantly, if contractualism’s “ethical baseline”—the default position—is a highly restrictive universal lockdown whenever each person is both a potential vector and a potential victim, then we should be locking down each time there is an epidemic of a mild seasonal cold or any other minor epidemic pathogen. Kindergartens would be permanently closed, because they are permanent hotbeds of little vectors and victims, as any parent can tell you.

Thus, in many public health problems, contractualism is in conflict with the presumption of liberty and it biases policies toward more restrictive and intrusive measures. The default position of contractualist policy analysts would be to begin from maximally restrictive policies and try to find justifications for weakening the restrictions. Following the presumption of liberty, however, our default position should be to begin from the least restrictive and invasive policies and then to introduce further restrictions only if they are thoroughly justified. Contractualism gets the burden of proof backward.

For illustration, consider again Figure 1. Recall that the lax policy (represented by point L) and the strict policy (represented by point S) both minimize the overall burdens that are made up of economic losses and harms to health. From this perspective, they are (nearly) equivalent, even though they are different trade-offs between economic losses and health harms. It is the presumption of liberty that gives priority to the lax policy. Contractualism, however, starts from a presumption of maximal restrictions. It is likely to rank S higher than L, even though it is a needlessly strict policy, given that there is a (nearly) equivalent trade-off that involves less severe restrictions on civil liberties. At the very least, L requires a more complex justification on contractualism, since the justification proceeds backward, moving—“contracting out”—from more extensive toward less strict restrictions.

No doubt contractualists can respond that it is easier to “contract out” from an epidemic of the seasonal common cold than from a global pandemic caused by a highly lethal virus. But why is that? Representative individuals would lodge complaints supported by the relatively small benefits and high costs of more extreme forms of social distancing in response to a mild illness. As both potential vectors and victims, they would consider the risks and the costs and benefits of different policies. In other words, they would engage in a similar aggregative process of adding up and comparing costs and benefits as traditional cost-benefit approaches do. It is difficult to see how contractualist policy analysis would avoid collapsing into a form of cost-benefit analysis.

It might be tempting to argue that contractualists could somehow “build in” the presumption in favor of liberty to the complaints that representative individuals can raise against different policies, but it is difficult to see how this could be done. To be workable, contractualism needs at least roughly to quantify complaints, otherwise they cannot be compared. However, it does not seem possible to quantify the (dis)value of losses of liberty in a way that can be added to economic and health costs. What is the disvalue of not being able to travel further than five kilometers from your home or not being able to be outside for more than one hour? How do they relate to loss of income or reduced health-related quality of life? Does the value of liberty vary if restrictions are met with willing cooperation and voluntary compliance or passive disobedience and active resistance? An account of complaints that incorporates the presumption in favor of liberty would need to answer these questions. Contractualists can avoid them only if they make the trade-offs between public health and civil liberties indirect, just like cost-benefit approaches do.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic forced difficult trade-offs on societies between the protection of public health and respect for civil liberties. On the standard approach, responding to such an emergency begins with using cost-benefit analysis to identify the most promising trade-offs. It is then a task for policymakers to choose a policy with the presumption in favor of civil liberties (and other moral considerations) in mind.

In the wake of the pandemic, some philosophers started to argue that this approach should be rejected because of the aggregative nature of cost-benefit analysis. They proposed to use contractualism to assess policies in its stead. However, contractualism permits some forms of aggregation as long as the harms and benefits are all relevant. I have tried to show that this approach becomes unworkable when irrelevant harms and benefits accumulate through time, an outcome that fits the actual trade-offs that societies in real life had to make in response to COVID-19. More generally, ignoring small harms and benefits creates a tendency to push aside the presumption in favor of civil liberties. This gives us reason to be hesitant about adopting the contractualist alternative.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the other contributors to this volume as well as David Schmidtz and an anonymous reviewer for extremely useful, detailed comments on an earlier version of this essay. I also received valuable comments from audiences at Umeå University, the Karolinska Institute Medical Ethics Conference in Stockholm, a Pandemic Ethics Workshop at the Institute for Futures Studies in Stockholm, the 11th European Congress of Analytic Philosophy in Vienna, a World Bioethics Day Workshop at the University of Turku, the Bioethics Meets Political Philosophy Conference in Kraków, and the 36th European Conference on Philosophy of Medicine & Health Care in Frankfurt/Offenbach.

Competing interests

The author declares none.