Introduction

Phenotypic variation in morphological, physiological or ecological traits is considered indispensable for successful establishment of plants (Richards et al., Reference Richards, Bossdorf, Muth, Gurevitch and Pigliucci2006; Funk, Reference Funk2008; Hulme, Reference Hulme2008). Genetically based phenotypic variation within populations forms the basis of an adaptive response to novel environments (Williamson and Fitter, Reference Williamson and Fitter1996; Lee, Reference Lee2002; Durka et al., Reference Durka, Bossdorf, Prati and Auge2005; Hedrick, Reference Hedrick2005). Ultimate genetic sources of phenotypic variation in a population are mutations and recombination, originating from either the same source population or from different ones via gene flow. In early stages of invasions, gene flow is mainly caused by repeated introductions in the newly invaded range (Kolar and Lodge, Reference Kolar and Lodge2001; Lockwood et al., Reference Lockwood, Cassey and Blackburn2009). At this stage, seed traits play a key role. In general, it is advantageous to produce numerous seeds. However, this is at the expense of the unavoidable trade-off between seed number and seed weight, with optimum allocation patterns along this trade-off, depending on habitat quality (Li and Feng, Reference Li and Feng2009; Münzbergová and Plačková, Reference Münzbergová and Plačková2010). For example, in arid regions in Australia, Jurado and Westoby (Reference Jurado and Westoby1992) have shown that it is advantageous for a plant species to produce small seeds in nutrient-rich habitats and large seeds in habitats with low levels of resources. We would expect a similar pattern for habitats differing in disturbance intensity, with numerous seeds being more advantageous in disturbed sites and large seeds in undisturbed sites. However, studies on the role of disturbance regime on seed traits are virtually absent.

Differences in seed size do not necessarily have to be adaptive responses to habitat conditions, since they might also reflect effects of resource fluctuation during fruit development, as was demonstrated for Convallaria majalis L. (Eriksson, Reference Eriksson1999). Furthermore, small population sizes, as well as a high intensity of intraspecific competition in dense populations, can negatively affect seed production and seed mass (de Clavijo and Jiménez, Reference de Clavijo and Jiménez1998; Vergeer et al., Reference Vergeer, Sonderen and Ouborg2004). It has often been shown that seed mass is positively associated with percentage germination and germination velocity (Eriksson, Reference Eriksson1999; Jacquemyn et al., Reference Jacquemyn, Brys and Hermy2001), which are both key traits of successful establishment (Colautti et al., Reference Colautti, Grigorovich and MacIsaak2006; Hao et al., Reference Hao, Qiang, Liu and Cao2009; Beckmann et al., Reference Beckmann, Bruelheide and Erfmeier2011). Thus, high phenotypic variation of seed traits might increase the potential of meeting habitat-specific germination demands and, thus, facilitate colonization of different habitat types.

Phenotypic variation in seed traits can be brought about both by high genetic variation within populations or by a high plasticity of a particular genotype (Baker, Reference Baker1974; Buckley et al., Reference Buckley, Downey, Fowler, Hill, Memmot, Norambuena, Pitcairn, Shaw, Sheppard, Winks, Wittenberg and Rees2003). In observational studies, it is difficult to quantify the contribution of these two components, in particular, for species that do not reproduce vegetatively, which applies to most annual species. As the preferred way of detecting plasticity is to subject vegetative offspring of the same individual to different environments, this approach cannot be used for annuals. In this case, insights can be gained by comparing phenotypic variation with genetic variation (Parker et al., Reference Parker, Rodriguez and Loik2003). Both types of information are not necessarily related to each other, because phenotypic variation might be subjected to selection pressure and measures of genetic variation are mostly based on neutral markers. Nonetheless, bottleneck and/or founder event signatures in neutral genetic marker diversity (e.g. reduced allelic richness and heterozygosity) have been shown to negatively impact phenotypic variation and to promote inbreeding depression (Lavergne and Molofsky, Reference Lavergne and Molofsky2007; Prentis et al., Reference Prentis, White, Radford, Lowe and Clarke2007; Dlugosch and Parker, Reference Dlugosch and Parker2008). The latter, in turn, can be strongly expressed in traits associated with early life stages, such as seed mass and percentage germination rate as well as time to germination, and, in consequence, lead to reduced seed production and fitness in populations (Garcia-Serrano et al., Reference Garcia-Serrano, Escarré and Sans2008; Münzbergová and Plačková, Reference Münzbergová and Plačková2010; Gargano et al., Reference Gargano, Gullo and Bernardo2011).

We addressed the question as to whether intra- or inter-plant phenotypic variation contributes to successful establishment in different habitat disturbance types, using the invasive plant species Senecio vernalis Waldst. & Kit. (Asteraceae) as study object. The extensive spread of this species in Germany since 1850 and the steadily increasing number of populations since the early 20th century, with more and more different habitat types being colonized, allows for testing the degree to which seeds differ in characteristics between habitats of different degrees of disturbance. S. vernalis is characterized by very high seed production, resulting from numerous flower heads per individual, with approximately 100 seeds (achenes) per capitulum (Wagenitz, Reference Wagenitz1987; the present authors, pers. obs.). For Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. it has been shown that seed or fruit numbers at the population level are positively affected by genetic diversity (Crawford and Whitney, Reference Crawford and Whitney2010). However, ample seed production of a species provides the potential for increased variation in seed traits. Moreover, in the case of S. vernalis, the high propagule production of small and light pappus-bearing achenes facilitates long-distance dispersal and, therefore, can support high gene flow, with the consequence of high genetic variation within populations. In addition, gene flow is enhanced by the species' outcrossing breeding system, with insect pollination and a strong incompatibility system (Comes and Kadereit, Reference Comes and Kadereit1990). In a set of 19 populations, we quantified the variability in reproductive traits and assessed the genetic variation with amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) markers. We asked: (1) whether populations of different habitat disturbance types differ in mean seed traits and germination characteristics; and (2) whether highest phenotypic variation in seed traits and germination characteristics is encountered between individuals within populations, thus allowing a population with high phenotypic variation to colonize different habitat disturbance types. In contrast, phenotypic variation within individuals (seed families, i.e. the offspring of the same seed parent regardless of whether representing half- or full-sibs) or between populations of different habitat disturbance types was expected to play a minor role. Finally, we asked: (3) whether partitioning of molecular genetic variation reveals a differentiation between habitat disturbance types; and (4) whether a high phenotypic variation at the different levels is reflected in molecular variation, thus possibly providing indications for a genetic basis of the phenotypic variation encountered.

Materials and methods

Study species

S. vernalis is a (winter-) annual species of the Asteraceae family. The species is native to western Asia, including the Caucasus and western Russia, with a continuous westward expansion of the geographic range since the early 19th century (Wagenitz, Reference Wagenitz1987; Meusel and Jäger, Reference Meusel and Jäger1992). Initially, the species seems to have been dispersed naturally by wind into the eastern Baltic region and Poland, but then increasingly profited from being unintentionally admixed to clover and grass seed (Wagenitz, Reference Wagenitz1987). The origin of the invasive ecotype is still not clear, as it shows distinct differences to native provenances from Israel (Comes and Kadereit, Reference Comes and Kadereit1996). Thus, it is probable that the species underwent adaptive evolution during its range expansion to central and western Europe. While the spread in some regions is still ongoing, such as in the Halle area (Eastern Germany), population number and sizes of S. vernalis have declined in other regions, such as the Czech Republic (Wagenitz, Reference Wagenitz1987). S. vernalis colonizes a wide range of habitats, from arable fields to railway embankments and roadsides, displaying a highly variable morphology in plant size (Klotz and Kühn, Reference Klotz and Kühn2002). In addition, both a rapid (seedling) growth rate and a short life cycle, being a common characteristic of invasive species in this genus (Caño et al., Reference Caño, Escarré, Vrieling and Sans2009), have been reported to increase the invasion potential of S. vernalis (Comes, Reference Comes1995).

Population sites and sampling

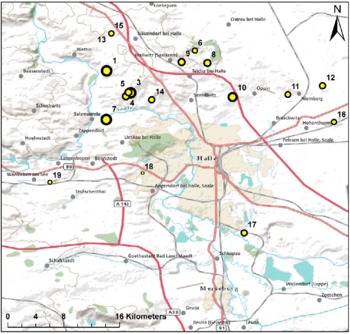

We sampled 18 populations in Halle (Saale) and Saalekreis (Saxony-Anhalt, Eastern Germany) in close proximity to each other (see Fig. 1) with a mean distance of 11.37 km ( ± 6.2 km standard deviation) and a maximum distance of 27 km, to ensure that all populations experienced comparable climatic conditions (Table 1). Additionally, we included one population with a distance of more than 200 km, located in Löbau (Saxony, Eastern Germany) that was used for comparative purposes of genetic differences (Table 1). All populations were sampled from the end of May to the middle of June 2008, which represented the main period of flowering and fruit ripening that year. Populations were selected by means of the following criteria: (1) minimum population size of more than 20 flowering and fruiting individuals of suitable habitats; (2) stratified sampling within different habitat disturbance types, such as roadsides, field margins, gravel-, clay- and sand-pits, and semi-dry grasslands. These habitat types differed in high, medium and low levels of disturbance intensity (Table 1), depending on the anthropogenic utilization of the area. Therefore we described the habitat in the year of leaf and seed sampling by personal observations and assigned each to one of three categories of disturbance intensity: (1) with multiple anthropogenic disturbance events per year, mostly regularly repeated roadside mowing or soil tilling (high level of disturbance, n= 7 populations); (2) on average one event per year, of either mowing or soil/stone digging (medium level of disturbance, n= 7 populations); or (3) events only every other year, of mowing or tilling or anthropogenic trampling pressure (low level of disturbance, n= 5 populations). All populations were located on slopes exposed to the south–southwest, the typical aspect of the S. vernalis habitats in that region. Population size was assessed by counting individuals on a section of the whole area covered by S. vernalis and then extrapolated to the whole area taken by the population. Two sampling approaches were applied per population, reflecting the first two hypotheses. For testing the first hypothesis, that seed traits and germination characteristics differ among habitat disturbance types, we collected seeds in a pooled sample across every population (sample set 1). This sampling strategy was employed to capture as much of the variation of seeds as possible per population. The second and third hypotheses, related to the distribution of phenotypic and genetic variation across levels, were tested by collecting seeds by seed family, i.e. separately from 9 to 22 mother plants per population, together with corresponding leaf and stem material of the same individuals (sample set 2). Sampling by seed families was carried out to assess how much of the variation in seed traits and germination patterns might have a genetic component. Using seed families is the only option to address heritability because the species does not exhibit vegetative reproduction.

Figure 1 Geographic map of 18 sampled Senecio vernalis populations in Halle (Saale) and Saalekreis (Saxony-Anhalt, Eastern Germany). © Dr Erik Welk, Martin Luther University Halle Wittenberg, Institute of Biology/Geobotany and Botanical Garden, www.botanik.uni-halle.de/mitarbeiterinnen_mitarbeiter/erik_welk/ (A colour version of this figure can be found online at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/ssr).

Table 1 Location and affiliation of sampled populations of Senecio vernalis to habitat disturbance types in Eastern Germany and their inclusion in the germination experiments

Ind., individual; No., number; Pop., population; SF, seed family; SS, sample set. Levels of disturbance intensity were categorized as: High, repeated disturbance events per year (mostly by regularly repeated roadside mowing or soil tilling); Medium, on average one disturbance event per year (mostly by mowing or soil/stone digging); Low, disturbance events only every other year (mostly by mowing or tilling or anthropogenic trampling pressure).

Leaves and stems were dried on silica gel and used for molecular fingerprinting analyses. The seed material was stored at ambient temperature for about 2 months to allow for afterripening. Unripe seeds were then rejected and only ripe ones included in further seed trait and germination analyses. Achenes were considered ripe when they displayed a hard coat with green-brown coloration.

Seed traits and germination experiments

To test the first hypothesis, that seed traits and germination characteristics differ among habitat disturbance types, we used approximately 50–100 ripe achenes (referred to as seeds in the following) per individual for seed trait analysis across 20 individuals per population if available. The pappus was removed before taking measurements on the seeds. Length, width and projection area were assessed with a scanner at 600 dpi resolution and the software WinSEEDLE 2004 PRO S (Regent, Canada). Furthermore, the same seeds were used to determine the mean seed mass per population.

Germination success was quantified in a germination experiment both for mixtures of seeds per population (sample set 1, duration 10 d, see Table 1) as well as for 49 selected seed families within populations (sample set 2, duration 46 d), using three replicates of 20 randomly selected seeds each, out of a seed pool, either by population (including seeds of different individuals per population) or by seed family (including seeds of only one individual). The germination experiments were carried out in regularly watered Petri dishes placed in germination cabinets (RUMER, Rubarth Apparate GmbH, Germany) at a daily alternating thermo- and photoperiod of 20/10°C per 12 h. Populations 2 and 18 had to be excluded from the germination experiment because of insufficient numbers of ripe seeds. During the first 8 d, monitoring of seedlings occurred every day, then at increasing intervals, finally reaching 1-week intervals for Petri dishes of sample set 2.

Statistical analysis of seed traits and germination characteristics

Seed trait and germination data were analysed with the program SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA). Germination characteristics were related to seed traits by normal linear regressions, using population means. Addressing both the first and the second hypotheses, relationships between seed and germination trait values of populations (sample set 1) and habitat disturbance types were analysed by a mixed effects model (proc mixed) with a nested design, i.e. with individuals being nested in populations as well as populations being nested in habitat disturbance types. Habitat disturbance types were regarded as fixed factors, while populations (Pop. seed traits: n= 19, germination traits: n= 17) were considered random. Data on germination characteristics were rank transformed prior to analysis because of non-normal distribution. In contrast, population seed traits (seed length, seed width, seed area averaged across seed families and seed mass averaged across populations) were normally distributed and were used untransformed. Measures of germination speed were derived from a logistic regression, using the logits of the ratio of germinated to non-germinated seeds as response variable, and time since sowing as predictor variable. The slope of the regression was taken as a measure of germination velocity, i.e. germination speed, and the inflexion point of the regression as time when 50% of the maximum germination was attained (MG50), i.e. the readiness to germinate. The calculations of germination variables were done with R 2.12.1 (R Development Core Team, 2008). Germination velocity and MG50 were used as response variables in the mixed effects model as described above. In order to prevent an inflation of the error rate by multiple testing of the same hypothesis with different response variables, we subjected all seed traits and germination characteristics to a MANOVA, testing for effects of habitat disturbance types and using Wilks' Lambda as test statistic (proc glm, SAS 9.2). For analysing the levels of phenotypic variation among habitat disturbance types and among and within populations (sample set 2) we used variance partitioning, considering all levels (also habitat disturbance type) to be random factors (proc mixed, covtest). All figures were produced with the software R.

DNA extraction and AFLP analyses

To test the third hypothesis of a correspondence between phenotypic and genetic variation, nuclear DNA was extracted from 362 individuals sampled from the 19 populations (sample set 2). However, in subsequent analyses, we included a reduced set of 180 individuals because high-quality polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products were obtained for four primer combinations for only these individuals (see Table 1 for range of sample sizes per population). First, dried plant material of leaves and stems were ground and homogenized (Tissue Lyser®, QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany). Genomic DNA purification was carried out with nexttecTM cleanPlates 96 and nexttecTM cleanColumns (nexttec GmbH, Leverkusen, Germany) following the protocol for isolation of genomic DNA from plants (nexttecTM mini version 4.0) with one modification of the protocol including a prolongation of the lysis step to 35 min for the nexttecTM cleanPlates 96. A quality check of successful isolation of genomic DNA was provided by gel electrophoresis of pure extracts.

The purified DNA was degraded with Mse-I and Pst-I overnight at room temperature. DNA was diluted with 3 μl distilled water and mixed with a mastermix (all items provided by New England Biolabs GmbH, Frankfurt/Main, Germany) of 0.05 μl distilled water, 1.1 μl × 10 T4 ligation buffer, 1.1 μl 0.5 M NaCl, 0.55 μl bovine serum albumin (BSA) (1 mg ml− 1), 1 μl Mse-I adapter (50 pmol μl− 1) and 1 μl Pst-I adapter (5 pmol μl− 1, metabion international AG, Planegg-Martinsried, Germany), 0.1 μl Pst-I (100 U μl− 1), 0.05 μl Mse-I (20 U μl− 1) and 0.05 μl T4 DNA ligase (2000 U μl− 1). Subsequently, ligation products were diluted 1:10 with distilled water for PCR of the first amplification. An amount of 4 μl diluted ligation products was combined with a mastermix (items provided by QIAGEN) comprising 9.64 μl distilled water, 2 μl × 10 PCR-buffer (NH4)2SO4, 2 μl × 10 dNTPs (2 mM), 1.2 μl MgCl2 (25 mM), 1 μl Pst-I and 1 μl Mse-I pre-selective primer (30 ng μl− 1, metabion international AG) and 0.16 μl Taq polymerase (5 U μl− 1). This amplification was performed with the Mastercycler® epgradient (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) for 2 min at 72°C, 25 cycles of (20 s at 94°C, 35 s at 56°C, 2 min at 72°C), 30 min at 62°C. Products of the first amplification were diluted 1:10 with distilled water for the PCR of the main amplification. From this diluted sample, 4 μl were mixed with a mastermix of 8.64 μl distilled water, 2 μl × 10 PCR-buffer (NH4)2SO4, 2 μl × 10 dNTPs, 1.2 μl MgCl2, 1 μl Pst-I (0.1 μM) and 1 μl Mse-I selective primer (0.5 μM; metabion international AG) and 0.16 μl Taq polymerase. We used the following four specific primer combinations: Pst-I 5′-CTCGTAGACTGCGTACATGCAACC-3′; Mse-I 5′-GATCAGTCCT GAGATACAG-3′; Mse-I 5′-GATCAGTCCTGAGATACAT-3′; Mse-I 5′-GATCAGTCCTG AGATACTC-3′; Mse-I 5′-GATCAGTCCTGAGATACTT-3′. All Mse-I primers were labelled with fluorescent Fam dye. The main amplification on the Mastercycler®epgradient ran for 2 min at 94°C, 10 cycles of (20 s at 94°C, 30 s at 66°C, 2 min at 72°C), 20 cycles of (20 s at 94°C, 30 s at 56°C, 2 min at 72°C), 30 min at 60°C. Main amplification products were purified with SephadexTM G-50 Superfine (GE Healthcare, München, Germany) for quality enhancement. Finally, the capillary-electrophoretic genotyping of these purified products was carried out with a MegaBACE 1000-Analyser (GE Healthcare Europe GmbH, Freiburg, Germany) by detection of light signals of the Fam dye.

Statistical analysis of molecular genetic data

To analyse our third hypothesis, band scoring was performed with the program Fragment Profiler 1.2 (GE Healthcare Europe GmbH, Freiburg, Germany). A presence/absence (1/0) matrix was created and used to calculate expected heterozygosity, percentage of polymorphic loci and Shannon's diversity index, and to analyse molecular variance (AMOVA) with the program GenAlEx 6.1 (Peakall and Smouse, Reference Peakall and Smouse2001). Furthermore, we carried out a principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) using Jaccard distances of loci patterns at the level of individuals (sample set 3). A second PCoA was run at the population level using the centroids of the preceding PCoA (except for populations 2 and 18). Ten axes were used because they roughly accounted for one-third of the variation in loci patterns of all individuals. In a post-hoc regression, the population scores of the first two PCoA axes were related to the population mean values of seed traits, germination rates (germination = percentage maximum germination; MG50= half of the percentage maximum germination; velocity = germination velocity), habitat disturbance types and population characteristics. The significance of the correlations was assessed with permutation tests (n= 999). Finally, a Mantel test was calculated to relate genetic distance with geographic distance of populations, thus testing for isolation by distance. PCoAs, linear regressions and the Mantel test were calculated with R 2.12.1, using the vegan package (Oksanen et al., Reference Oksanen, Kindt, Legendre and O'Hara2006).

Results

Relationships between trait value and habitat disturbance type

Analyses of mean seed trait values at the population level (sample set 1) showed no significant relationships with habitat disturbance types, with the exception of seed width (Table 2). Populations from habitats with a high level of disturbance had the narrowest seeds, whereas the least disturbed populations displayed intermediate seed width. However, this difference was not reflected in the other seed size dimensions, as the multivariate analysis, considering seed traits and germination characteristics simultaneously, revealed no significant differences between habitat types. Consistently, there was also no significant effect of habitat disturbance type on maximum germination, time to 50% of maximum germination (MG50) and germination velocity (Table 2). Maximum germination was positively affected by seed mass and marginally by seed width, while seed area and length did not significantly affect maximum germination (Table 3). There was no effect of seed mass on time to 50% of maximum germination (MG50) and germination velocity (data not shown).

Table 2 Effects of habitat disturbance type on seed characteristics of Senecio vernalis. Results of the mixed effects models for the seed traits projection area, length, width and mass of sampled seeds, and maximum germination, time for 50% of the maximum germination (MG50) and germination velocity (sample set 1), accounting for random effects of populations (Pop). Data on germination characteristics were rank transformed prior to analysis, while seed traits were used untransformed. In addition, a MANOVA was calculated for the joint effect of habitat disturbance types on all seven seed and germination traits. Z and F values refer to the test statistics of random and fixed factors, respectively. N=19 populations (seed traits), n=17 populations (germination traits). Bold fonts indicate significant effects (P<0.05)

Table 3 Linear regressions showing effects of descriptive variables on mean germination of populations of Senecio vernalis (n=17). Bold fonts indicate significant effects (P<0.05)

Levels of phenotypic variation

At the level of seed families (sample set 2), we found significant effects of population and seed family within population for all seed traits (Table 4). In accordance with the results on habitat disturbance type relationships of trait values, habitat disturbance type turned out to be a non-significant factor in overall phenotypic variation. The largest proportion of total variance of seed traits was attributable to the residual error, whereas seed family ranked second in contribution to total variance, with 38.27, 44.63 and 20.91%, and population ranked third, with 8.00, 10.79 and 5.56%, for seed area, length and width, respectively (Table 4). Similarly, population was a significant random factor for maximum germination, time to 50% of maximum germination (MG50) and germination velocity, explaining 77.29, 82.67 and 74.82% of the total variance, respectively (Table 4). In contrast, habitat disturbance types had no impact on these germination characteristics (Table 4).

Table 4 Phenotypic variance partitioning among habitat disturbance types (Habitat), populations (Pop) and seed families (Seed fam) of Senecio vernalis (sample set 2, n=3–22 per population, n=5–105 per individual). In this analysis, all factors are considered random. Data on germination characteristics were rank transformed prior to analysis, while seed traits were used untransformed. Bold fonts indicate significant effects (P<0.05)

–, Variance was too low to be estimated in the mixed model.

Relationship between phenotypic and genetic variation

AFLP analyses revealed high levels of genetic variation in the populations studied (Table 5). Populations 7, 9 and 13 featured both highest values of expected heterozygosity (He) and of Shannon's diversity index (H′), whereas populations 3, 5, 12 and 19 displayed lowest values. The percentage of polymorphic loci was comparable among populations, except for a low number of polymorphic loci (Pl) in populations 5, 12, 18 and 19. The highest amount of genetic variation (96%) was encountered within populations, as revealed by the analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) (Table 6). In contrast to the results on phenotypic variation of seed traits, almost no genetic variation was attributable to the population level (3%), while habitat disturbance types had a similarly negligible impact (1%). These findings are also reflected by the principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) based on individual plants (see supplementary Figure S1, available online only at http://journals.cambridge.org/), which neither showed a clustering of plants of the same population, nor of the same habitat disturbance type. Interestingly, the remote population (population 2) was genetically not distinguishable from the ones in the target area despite a geographical distance of more than 200 km. Accordingly, the Mantel test exhibited no relationship between genetic and geographic distances among populations (P= 0.294).

Table 5 AFLP analyses of 19 populations of Senecio vernalis (N=180 individuals) based on 67 AFLP loci

H′, Shannon's diversity index; He, expected heterozygosity; Pl, percentage of polymorphic loci.

Table 6 AMOVA of AFLP differentiation of Senecio vernalis among habitat disturbance types and populations, and for variation within populations (Pop). N=180. Bold fonts indicate significant effects (P<0.05)

SS, Sum of squares; Φ, phi values among habitat disturbances classes (ΦRT), among populations (ΦPT) and among individuals (ΦPR).

With the low levels of genetic variation at the population level, as revealed by the AMOVA, we refrained from using pair-wise ΦST values to test for relationships among the overall AFLP patterns and habitat disturbance types, seed traits, germination and population characteristics. Instead we concentrated on those aspects of the locus information that resulted in the best possible separation of individuals in AFLP space. Thus, we used the scores from the PCoA performed on individual plants to calculate population centroids, and then subjected these centroids to a second PCoA (Fig. 2). Populations from habitats with high disturbance levels showed a tendency of negative scores on PCoA axis 1. Furthermore, there was a significant correlation of seed width with the first PCoA axis (P= 0.032), whereas estimated population size (Pop_size) was correlated with the second PCoA axis (P= 0.027) (see supplementary Table S1 available online only at http://journals.cambridge.org/). Direction and lengths of arrows of traits and population characteristics indicated that populations with high germination velocity and germination rate had low seed widths and MG50 values (Fig. 2), indicating that fast-germinating seeds in these populations were narrower.

Figure 2 Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of AFLP loci of Senecio vernalis based on population centroids of a preceding individual-based PCoA (see Methods and supplementary Table S1 available online only at http://journals.cambridge.org/). In a post-hoc regression the PCoA scores were correlated with habitat disturbance type, seed traits and germination characteristics. Variables are the same as in Tables 2 and 3. Germination = maximum germination; Pop_area = population area; Pop_size = population size; Velocity = Germination velocity, as derived from a logistic regression based on the ratio of germinated to non-germinated seeds with time since sowing. Different habitat disturbance types are labelled white (low disturbance), grey (medium disturbance) and black (high disturbance). N= 17. (A colour version of this figure can be found online at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/ssr).

Discussion

Relationships of habitat disturbance type with seed traits and germination characteristics

We have to reject the first hypothesis that means of seed traits and germination characteristics differ between S. vernalis populations of different habitat disturbance types. These results are in contrast to many studies that detected significant relationships between seed traits and the environment, thus providing evidence for population differentiation and local adaptation in these traits (Pico et al., Reference Pico, Ouborg and Groenendael2003; Butola et al., Reference Butola, Vashistha, Malik and Samant2010). For instance, seeds of Parthenium hysterophorus L. were shown to be smaller and larger in populations growing on soils with high clay content, while seed mass decreased and seed production increased with increasing coarseness of the soil texture (Annapurna and Singh, Reference Annapurna and Singh2003). McIntyre et al. (Reference McIntyre, Lavorel and Tremont1995) showed that seed morphology of grassland species responded to effects of soil disturbance rather than to grazing or water availability. Furthermore, trampling disturbance was found to affect seed size of Polygonum aviculare L. negatively, whereas weeding or the absence of disturbance had no effects (Meerts and Garnier, Reference Meerts and Garnier1996). Comparing 11 prairie plant species, Suding et al. (Reference Suding, Goldberg and Hartman2003) reported that the species' tolerance to defoliation was linked to low seed mass and high germination capacity. Accordingly, for germination patterns, several studies have demonstrated that the sensitive period of germination can reflect responses to environmental conditions. For instance, percentage germination of Cortaderia spp. interacted positively with soil disturbance and habitat types, with greatest seedling emergence of Cortaderia jubata (Lem.) Stapf at grassland sites (Lambrinos, Reference Lambrinos2002). Erfmeier et al. (Reference Erfmeier, Böhnke and Bruelheide2011) found faster germination in seeds from invasive Acer negundo L. populations from moist sites compared to dry habitats. Similarly, percentage germination and germination speed of Tragopogon pratensis L. were higher for seeds from roadsides than from hayfields (Jorritsma-Wienk et al., Reference Jorritsma-Wienk, Ameloot, Lenssen and Kroon2006). However, there are also findings that report germination to be independent of nutrient conditions (Violle et al., Reference Violle, Castro, Richarte and Navas2009) or of habitat types (Bu et al., Reference Bu, Chen, Xu, Liu, Jia and Du2007).

The expected positive impact of seed mass on germination of S. vernalis has been confirmed and can be interpreted as direct positive effect of higher resource reserves on germination (Obeso, Reference Obeso1993; Eriksson, Reference Eriksson1999; de Clavijo, Reference de Clavijo2002). However, this effect was independent of habitat disturbance types. These findings contrast with reports from native plants, where populations showed a strong differentiation between habitat disturbance types (Chamorro and Sans, Reference Chamorro and Sans2010).

The lack of clear habitat disturbance effects on the majority of seed traits and germination characteristics of S. vernalis might have several explanations. The obvious explanation would be that the seed traits analysed were not adaptive to the habitat disturbance types investigated. Similarly, Monty and Mahy (Reference Monty and Mahy2010) compared populations of the congeneric species S. inaequidens DC within the introduced range in southern France. The authors described a low phenotypic differentiation in dispersal-related traits, thus confirming the assumption that habitat disturbance effects on seed trait differentiation might be low. However, we also have to acknowledge that other environmental features, not measured in our study and possibly interfering with disturbance, might also have affected seed characteristics, as has been demonstrated, for example, for herbivory (Lambrinos, Reference Lambrinos2002; Caño et al., Reference Caño, Escarré, Vrieling and Sans2009), soil characteristics or native canopy cover (Münzbergová and Plačková, Reference Münzbergová and Plačková2010; Faast et al., Reference Faast, Facelli and Austin2011).

Levels of phenotypic variation

S. vernalis exhibited the highest level of phenotypic variation in seed traits and germination characteristics within single mother plants, with seed families and populations also contributing less, but still significant, amounts of variance in seed trait values. Thus, we have to reject the second hypothesis, since we did not encounter a higher variation in phenotypic traits between populations or between individual mother plants. The great importance of variation in seed traits within individual plants has already been demonstrated for other herb species, as shown for seed length in Chelidonium majus L. (Kang and Primack, Reference Kang and Primack1991). Such high variation at the within-individual level can be advantageous for germination and subsequent population establishment success in heterogeneous and unpredictable environments. For the invasion of Ambrosia artemisiifolia L., Fumanal et al. (Reference Fumanal, Chauvel, Sabatier and Bretagnolle2007) concluded that the potential of a non-native species can be largely attributed to the within-individual variability in seed mass and germination. However, to assess the evolutionary dimension of phenotypic variation in S. vernalis in the invasion process one would need to compare different provenances differing in phenotypic variation. Although clear differences in life-history characteristics have been encountered between different provenances across the species' geographic range, as for instance, native populations of S. vernalis in Israel were found to flower significantly earlier than populations in the invasion range of central Europe (Comes and Kadereit, Reference Comes and Kadereit1996), the degree to which within-population variation in these life-history traits might contribute to a species' invasive spread in general is still unclear (Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Jennions and Nicotra2011).

Relationship between phenotypic and genetic variation

In full accordance with the findings on phenotypic variation, S. vernalis exhibited the highest genetic variation at the within-population level, without displaying any clustering of populations in habitat disturbance types or any dependence on geographical distance. Thus, our third hypothesis has to be rejected. This finding differs from those for the highly selfing species Senecio vulgaris L. for which Haldimann et al. (Reference Haldimann, Steinger and Müller-Schärer2003) reported a significant genetic AFLP differentiation between regions, and Müller-Schärer and Fischer (Reference Müller-Schärer and Fischer2001) described a significant isolation by geographical distance. Self-compatibility and high selfing rates are probably also the pre-condition for differences between habitats of different disturbance regimes, as were encountered for A. thaliana, with respect both to parameters of genetic diversity such as heterozygosity and to seed traits such as seed mass and percentage germination rate (Schubert et al., Reference Schubert, O'Neill, Kohler and Waldhardt2002). Similarly, the partly autogamous Amaranthus retroflexus L. showed a strong differentiation among populations in the Czech Republic (Mandák et al., Reference Mandák, Zákravský, Dostál and Plačková2011). In contrast, in S. vernalis, high rates of insect-mediated outcrossing and effective seed dispersal by wind facilitate gene flow and counteract population differentiation (Sambatti and Rice, Reference Sambatti and Rice2006; Dlugosch and Parker, Reference Dlugosch and Parker2008; Mandák et al., Reference Mandák, Zákravský, Korínková, Dostál and Plačková2009). Although the level of population differentiation in S. vernalis is similarly low, as reported from Israeli populations of the same species based on allozymes (Θn= 0.04, Comes and Abbott, Reference Comes and Abbott1999), other closely related and highly self-incompatible outcrossing Senecio species of the same ploidy level (diploid), S. glaucus L. (Israel) and S. gallicus Chaix (southern France and Spain), showed a much higher population subdivision, with Θn= 0.12 (Comes and Abbott, Reference Comes and Abbott1999) and Θn= 0.12 (Comes and Abbott, Reference Comes and Abbott1998), respectively. However, it should be acknowledged that these results are difficult to compare with the low level of among-population differentiation in our study, because of the much more confined geographical scale involved here. At the small geographical scale analysed, gene flow is probably too high to allow for a population differentiation between habitats of different disturbance levels. In addition, a high genetic variation within, and low differentiation between, populations would also be observed with subsequent introductions from one into another invasive region (Henry et al., Reference Henry, Le Lay, Goudet, Guisan, Jahodová and Besnard2009; Doorduin et al., Reference Doorduin, van den Hof, Vrieling and Joshi2010). For invasive S. inaequidens occurrences in Europe, Lachmuth et al. (Reference Lachmuth, Durka and Schurr2010), for example, found a positive relationship between genetic diversity and population age. The authors attributed this pattern to effects of multiple introductions and high gene flow along well-connected invasion routes that counteracted losses of genetic variation during rapid spread. However, with a mean value of He= 0.161, expected heterozygosity for S. vernalis in Germany was lower than in the populations in the Near East (He= 0.288; Comes and Abbott, Reference Comes and Abbott1999). In contrast, Prentis et al. (Reference Prentis, White, Radford, Lowe and Clarke2007) determined Shannon's diversity index with AFLP-analysis for non-native S. pinifolius (L.) Lam. (H′ = 0.27) and S. madagascariensis Poir. (H′ = 0.239) in Australia and found similar values to those we encountered for S. vernalis (H′ = 0.256). Moreover, mean percentage of polymorphic loci showed similar values to those of Israeli populations (Comes and Abbott, Reference Comes and Abbott1999).

Despite high gene flow among S. vernalis populations, there was also a distinct association of AFLP band patterns with population size, a pattern that has frequently been reported. For example, large population size was found to be strongly related to genetic diversity in Bromus tectorum L. (Ramakrishan et al., Reference Ramakrishan, Meyer, Fairbanks and Coleman2006), but there was no relationship between genetic variation and population size in Campanula glomerata L. (Bachmann and Hensen, Reference Bachmann and Hensen2007) or in Festuca hallii (Vasey) Piper (Qui et al., Reference Qui, Fu, Bai and Wilmshurst2009). In addition, the correlation of population means in seed width with their AFLP-based scores on the first PCoA axis (Fig. 2) indicates that the phenotypic variation encountered might have a genetic basis. Although variation in AFLP is generally assumed to be neutral, AFLP analysis has been successfully used to relate seed trait differences to genetic distances (Joost et al., Reference Joost, Bonin, Bruford, Després, Conord, Erhardt and Taberlet2007, Reference Joost, Kalbermatten and Bonin2008). In principle, AFLP also allows the detection of specific loci that are exposed to directional selection (Pérez-Figueroa et al., Reference Pérez-Figueroa, García-Pereira, Saura, Rolán-Alvarez and Caballero2010). Using microsatellites, Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Michalski, Chen and Durka2011) found one selective locus of Castanopsis eyrei Champ. ex Benth. to respond to different elevations within a Chinese subtropical forest. The authors detected only one prevailing allele in the lowlands, which was replaced by an increasing number of alleles with increasing elevation. Similarly, Michalski et al. (Reference Michalski, Durka, Jentsch, Kreyling, Pompe, Schweiger, Willner and Beierkuhnlein2010) were able to identify four potentially adaptive loci in different local provenances of Arrhenaterum elatius (L.) P. Beauv. ex J. Presl & K. Presl. Linking molecular information at potentially variable loci with reproductive and germination traits represents an eminent tool to unravel mechanistic relationships of plant invasions under different environmental conditions.

In conclusion, for S. vernalis, we have to reject the assumption that single seed-trait selection in response to heterogeneous habitat disturbance types has already taken place, since both a high phenotypic and a high genetic variation have been observed consistently at the within-population level. In addition, the association encountered between AFLP band patterns and seed width shows that at least some of the phenotypic variation in seed traits has a genetic component. However, both the observed high levels of within-population genetic variation and the inferred genetic component of certain seed traits should increase the potential of founder populations of S. vernalis to adapt to novel habitats once gene flow with source populations has been sundered.

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Kosellek and B. Müller for technical assistance in molecular analyses and B. Vonlanthen and D. Eichenberg, who provided valuable support in data analysis. We appreciate the supply of the population map of Senecio vernalis by Erik Welk. We acknowledge helpful discussions with M. Hofmann, D. Bachmann and W. Kröber. We are grateful to Peter Comes, who gave valuable comment on an earlier draft of the manuscript. The manuscript was considerably improved by the input of two anonymous referees.