Introduction

Seed germination during a favourable season for plant growth increases the probability of seedling survival (Baskin and Baskin, Reference Baskin and Baskin1972, Reference Baskin and Baskin1976, Reference Baskin and Baskin2014). Furthermore, germination at the beginning of the growing season means seedlings have the entire annual favourable period for establishment and growth. This early-in-the-season germination strategy is possible because dormancy-break occurs during the season when environmental conditions inhibit plant growth, thereby allowing seeds to germinate as soon as the favourable season for growth begins (Baskin and Baskin, Reference Baskin and Baskin2014). In summer annuals, seeds germinate in spring or early summer, plants grow vegetatively in summer and produce seeds before frost in autumn kills the plants. The low temperatures of winter prevent the growth of summer annuals, but they promote dormancy-break of seeds of temperate-zone summer annuals with physiological dormancy (PD, water-permeable seed coat and fully developed embryo). PD is broken while seeds are exposed to cold (ca. 0–10°C) moist conditions (cold stratification, CS) during winter (Baskin and Baskin, Reference Baskin and Baskin2014). Thus, seeds of these species are non-dormant when habitat conditions become favourable for plant growth in spring.

One prediction about the effect of climate change on the regeneration of plants from seeds with PD in the temperate zone is that the length of the winter seed dormancy-breaking period will be reduced, thereby decreasing the germination of spring-germinating species such as summer annuals and many perennials. For example, several laboratory studies have shown that a decrease in the length of winter CS period increases the percentage of seeds that is dormant when spring arrives (Mondoni et al., Reference Mondoni, Rossi, Orsenigo and Probert2012; Sommerville et al., Reference Sommerville, Martyn and Offord2013; Hoyle et al., Reference Hoyle, Cordiner, Good and Nicotra2014; Solarik et al., Reference Solarik, Gravel, Ameztequi, Bergeron and Messier2016). However, our observations in the field in central Kentucky (USA) reveal that seeds of some summer annuals germinate in late-winter before the CS period has ended. For example, we have observed newly emerged seedlings of Ambrosia artemisiifolia, Chenopodium album and Polygonum aviculare in mid-February and those of Ambrosia trifida, Helianthus annuus and Persicaria pensylvanicum in early March, 4–10 weeks before the end of the CS period.

These observations of late-winter germinating seeds of summer annuals lead us to hypothesize that the entire length of the winter CS period in central Kentucky is not needed to break dormancy in seeds of summer annuals with PD. To address this hypothesis, we reviewed the data we have collected over a 35-year period on dormancy-break and germination of summer annuals whose seeds have PD, which included germination phenology studies of 45 species and buried-seed studies of 33 species; 13 species were included in both studies. The broad objectives of this paper are to evaluate our germination data for summer annuals in relation to the temperature at which seeds first begin to germinate in spring and the number of hours of CS seeds received prior to germinating. We asked five questions. (1) How many hours of CS are seeds exposed to during the winter? (2) How many hours of CS have seeds been exposed to when they start to germinate under natural temperature regimes in late winter or early spring? (3) What are the temperatures when seeds begin to germinate in spring? (4) What percentage of the total number of hours of CS during winter have seeds received when they begin to germinate at spring temperatures? (5) Do seeds gain the ability to germinate at relatively high temperatures before temperatures in spring are high enough for them to do so?

Germination of seeds in the phenology studies when temperatures are low enough for CS would help support our hypothesis that the full length of the winter CS period is not required for dormancy-break. If seeds exhumed from burial under natural temperature conditions in early to mid-winter germinated at simulated March and April temperatures, this also would support our hypothesis. If dormancy-break does not require the full length of the winter CS period, we need to consider why germination is delayed after dormancy is broken and what the implications might be for summer annuals from a global warming perspective.

Results

Number of hours of cold stratification in winter

From autumn 1969 until autumn 2004, seed germination phenology and buried-seed studies were conducted in a non-temperature-controlled glasshouse (windows open year-round) on the campus of the University of Kentucky (Lexington, KY, USA). During this 35-year period, continuous electric thermograph records were kept of the air temperature inside a standard weather house located in the glasshouse. From the continuous temperature records, we counted the number of hours when temperatures were between 0 and 10°C, which is the effective temperature range for dormancy-break by CS, with 5° being optimal for many species (Stokes, Reference Stokes and Ruhland1965; Nikolaeva, Reference Nikolaeva1969).

For the 35-year period, the mean (±SE) number of hours of CS per winter was 2138.5 ± 52.6. The winters with the lowest and highest number of hours of CS were 1976–77 (1482 h) and 1982–83 (2685 h), respectively. The mean number of hours of CS per month for the 35-year period ranges from 0 in July and August to 406 h in December (Table 1). By the end of January, February and March, the cumulative mean number of hours of CS was 1284.5, 1636.9 and 1968.9, respectively.

Table 1. Mean (±SE) number of hours of cold stratification (CS) in the non-temperature-controlled glasshouse each month (1969–2004) and cumulative mean number of hours of CS from September to June

Time and temperature of germination in phenology studies

In the germination phenology studies, freshly collected seeds of 45 species of summer annuals growing mostly in central Kentucky (USA) but some were from central Tennessee (USA) were sown on the soil surface in the non-temperature-controlled glasshouse. From 1 September to 30 April of each year, the soil was watered to field capacity each day, except on some days during winter when it was frozen. In central Kentucky, the average total number of days per year with snow cover of 2.5 cm is 11 with 1–4 d of snow cover per month from December through March (Lawrimore et al., Reference Lawrimore, Applequist, Korzeniewski and Menne2016). During the remainder of the year, the soil was watered to field capacity once each week. Germination was monitored weekly throughout the year. To determine how much the temperature increases in spring before seeds begin to germinate, we used the daily maximum and minimum temperatures from the thermograph records to calculate mean (±SE) temperature for the week prior to the week of first germination and the week of first germination for each species. The 45 species of summer annuals included 27 C3 and 18 C4 species. Some species were collected and planted in more than 1 year, resulting in a total of 69 plantings (datasets): 45 for C3 and 24 for C4 species (Supplementary Table S1).

Seeds of the C3 species first germinated in February, March, April or May, depending on the species, with 65.9 and 20.5% of them first germinating in March and April, respectively. Seeds of the C4 species first germinated in March or April. Mean temperature during the week of first germination for C3 and C4 species was 11.1 ± 0.4 and 14.3 ± 0.8°C, respectively, and that of the week prior to the week of first germination was 9.4 ± 0.7 and 12.2 ± 0.8°C, respectively. Thus, the temperature when germination begins in spring is higher for C4 than for C3 species, which means that in general seeds of C4 species have received more hours of CS than those of C3 species when they begin to germinate.

However, it should be noted that for 19 of the 45 datasets for C3 species the temperature for the week of first germination was <10.5°C with a mean of 8.2 ± 0.3°C (Supplementary Table S1). The mean temperature for these 19 datasets for the week prior to the week of first germination was 7.2 ± 1.0°C. For five of the 24 datasets for C4 species, the temperature for the week of first germination was <10.5°C with a mean of 7.8 ± 0.6°C. The mean temperature for these five datasets for the week prior to the week of first germination was 11.4 ± 1.4°C.

In general, germination in spring occurs in response to an increase in temperature. For 33 of the 45 datasets for C3 species, the temperature during the week of first germination was 0.4–12.0°C (mean of 3.5 ± 0.5°C) higher than that during the week prior to the first week of germination (Supplementary Table S1). In 12 of the 45 datasets for C3 species, the temperature during the week of germination was 0.5–7.9°C (mean of 3.4 ± 0.6°C) lower than the previous week. For 19 of the 24 datasets for C4 species, the temperature during the week of germination was 0–7.9°C (mean of 3.4 ± 0.6°C) higher than the previous week. Only five of the 24 datasets for C4 species had a higher temperature during the week prior to the week of first germination than during the week of first germination (1.2–7.9°C, mean of 3.6 ± 1.1°C).

Number of hours of cold stratification in relation to temperature for earliest germination in phenology studies

For all datasets for the 45 species, the number of hours of CS between the time fresh seeds were sown in autumn and the week of first germination was counted (Supplementary Table S1), and the mean (±SE) number of hours of CS for C3 and C4 was 1551.1 ± 48.6 and 1727.7 ± 69.5, respectively. The percentage of the total number of hours of CS during the winter (hereafter % of winter CS) that seeds were exposed to before they began to germinate in spring (first week of germination) was 80.8 ± 1.7 and 87.4 ± 1.7 for C3 and C4 species, respectively.

For all datasets of each C3 and C4 species, we determined (1) the % of winter CS seeds received prior to the time germination began (first week of germination), and (2) the temperature during the week of first germination (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). For C3 and C4 species, mean temperature of the week of first germination generally increased as the % of winter CS between time of seed sowing and first germination increased, with the temperature increase higher for C4 than C3 species. The percentage of C3 datasets when seeds first germinated ranged from 2.2% (>50–60) to 26.7% (>90–100) of winter CS, while that of C4 datasets ranged from 4.2% (>60–70) to 50.0% (>90–100) of winter CS (Table 2).

Table 2. Relationship between mean (±SE) temperature of the first week of germination and percentage of total hours of cold stratification (% of winter CS) during winter seeds were exposed to prior to the week of first germination in glasshouse and percentage of databases in each increment of % winter CS when seeds first germinated; 27 C3 and 18 C4 species and 45 and 24 databases, respectively

a No data.

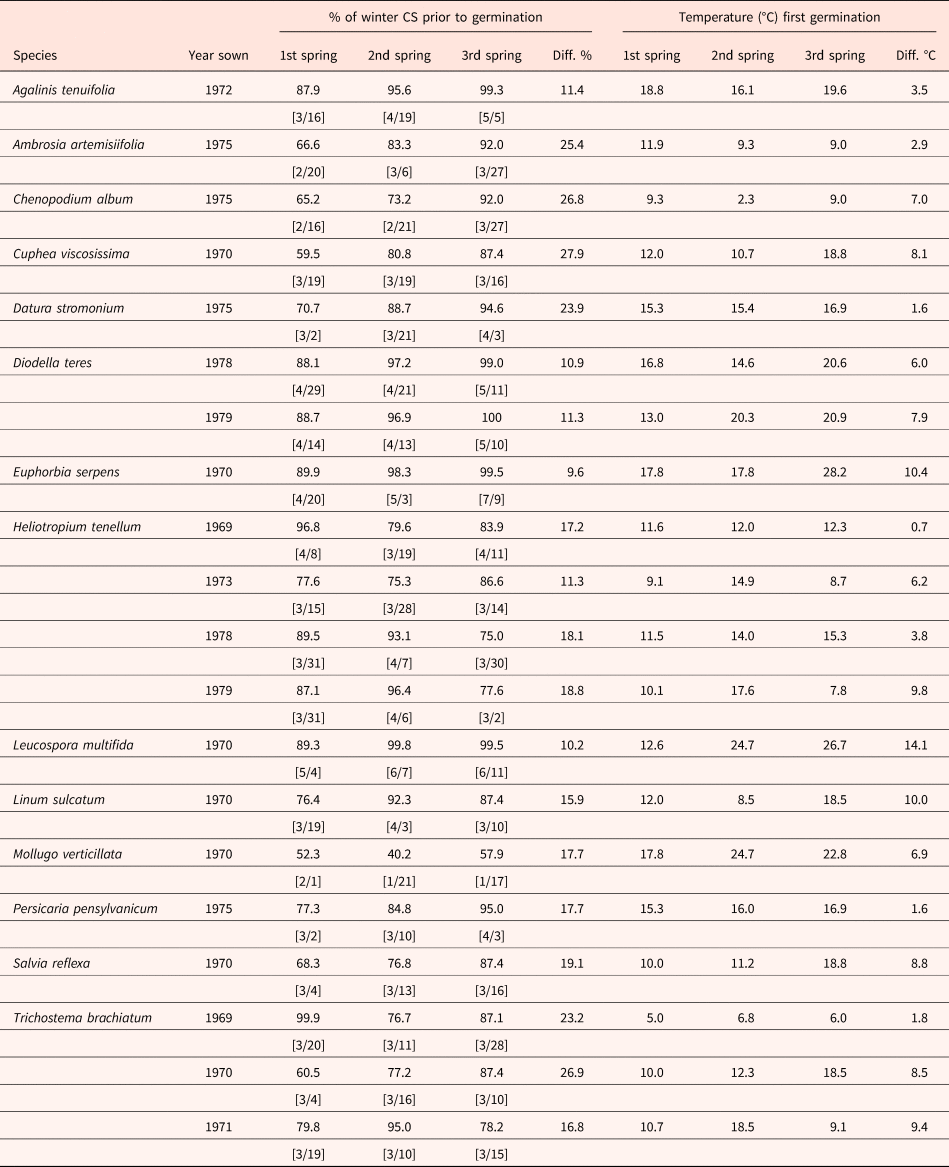

For 14 species (20 datasets), some of the seeds planted on a given date germinated in three consecutive springs, i.e. different fractions of the same (sown) seed cohort germinated in different years. These data provide some insight on year-to-year variation in the % of winter CS seeds receive before germination begins in spring and the temperature of the week of first germination for seeds in the same cohort. For these species, the % of winter CS that seeds received before they began to germinate in spring (first week of germination) and temperature of first germination were determined for each species/dataset for each year. In each species/dataset, the difference between the highest and lowest % of winter CS seeds received prior to the week of first germination ranged from about 9.6 to 26.9 (Table 3). Also, the temperature during the week of first germination varied from year-to-year, with the difference between years for all species/datasets ranging from 0.7 to 14.1°C. For the four plantings of Heliotropium tenellum, the year-to-year difference in the % of winter CS seeds were exposed to before the week of first germination ranged from 11.3 to 18.8, and the year-to-year difference in temperature of the week of first germination ranged from 0.7 to 9.8°C. For all species/datasets, except H. tenellum (planted in 1973), Trichostema brachiatum (planted in 1971) and Cuphea viscosissima, a later date in the year when germination began corresponds to an increase in the % of winter CS seeds received before germination began and generally an increase in the temperature of the week of first germination. Thus, for the same seed cohort, there is year-to-year variation in the % of winter CS seeds received prior to the first week of germination in spring and in the temperature when germination began. Overall, in 11 of 14 species, the seed fraction of a cohort that germinated in sequential years required increasing CS periods to first germinate (Table 3), regardless of the particular 3-year sequence involved.

Table 3. Percent of total number of hours of cold stratification (% of winter CS) in winter that seeds received prior to the week of first germination in three consecutive years and mean temperature of the week of first germination in each year.

[ ] indicates date when first germination was recorded in each year. Diff., maximum difference between 3 years. All species are C3, except Euphorbia serpens and Mollugo verticillata.

Time and temperature of germination in buried-seed studies

Between autumn 1974 and autumn 1995, freshly collected seeds of 33 species of summer annuals (14 C3 and 19 C4) from central Kentucky (USA) or central Tennessee (USA) were buried in pots of soil in the non-temperature-controlled glasshouse (see above). Seeds of some species were collected and buried in more than 1 year, resulting in 44 datasets (21 C3 and 23 C4) (Supplementary Table S2). On the day of burial, a sample of the seeds was tested for germination in light (14 h each day) at daily (12/12 h) temperature regimes of 15/6, 20/10, 30/15 and 35/20°C. Seeds were placed on wet sand in Petri dishes and incubated at each temperature regime for 15 d. On the first day of each month after seed burial, a sample of the buried seeds was exhumed, and seeds were tested for germination in light at the four temperature regimes. From continuous thermograph records in the glasshouse, we counted the number of hours of CS seeds of each species received while they were buried.

Since 85–100% of the summer annuals in the germination phenology studies began to germinate in March or April, we focused our evaluation of the results of the buried-seed studies on responses of seeds incubated in light at simulated March (15/6°C) and April (20/10°C) temperature regimes for northcentral Kentucky (Hill, Reference Hill1976). Seeds of 17 and 8 summer annuals never grained the ability to germinate at 15/6 and 20/10°C, respectively. Since the mean temperature for the week of first germination of summer annuals in the phenology studies was 12.4 ± 4.2°C (Supplementary Table S1), we asked in what month did exhumed seeds first germinated to 25 and 50% at 20/10°C.

CS lowered the minimum temperature at which seeds could germinate more for C3 than for C4 species. Seeds of 11 C3 species germinated at 20/10°C, and the month when germination first reached 25% ranged from November to March, depending on the species (Table 4). The month when the germination of C3 species first reached 50% at 20/10°C ranged from November to April. Seeds of 14 C4 species germinated at 20/10°C, and the month when germination first reached 25 and 50% ranged from December to July.

Table 4. Percentage of total C3 and C4 species datasets when seeds first germinated to 25 or 50% at each month from November to July

Seeds were buried in soil at natural temperatures, and then a sample was exhumed at monthly intervals and tested in light at 20/10°C. C3, 14 species but only 11 of them germinated in light at 20/10°C; C4, 19 species but only 14 of them germinated at 20/10°C.

In all species used in the buried-seed studies, except Agalinus fasciculata, there was a decrease in the minimum temperature at which seeds would germinate, as the CS period increased (Supplementary Table S2). A decrease in the minimum temperature at which seeds can germinate as the breaking of PD takes place indicates the presence of Type 2 non-deep PD (Baskin and Baskin, Reference Baskin and Baskin2014; Soltani et al., Reference Soltani, Baskin and Baskin2017). Seeds of A. fasciculata gained the ability to germinate at 20/10 and 15/6°C in December and January, respectively, but their temperature range for germination never expanded beyond these two temperature regimes. Seeds of this species have Type 5 non-deep PD (Baskin and Baskin, Reference Baskin and Baskin2014).

Hours of cold stratification in buried-seed studies

Considering all datasets, seeds of C4 species required more hours of CS to germinate to 25 and 50% at 20/10°C than those of C3 species. For C3 species, an increase in germination from 25 to 50% at 20/10°C required an increase in the number of hours of CS from 863.9 ± 124.4 to 1027.3 ± 130.2, while for C4 species an increase in germination from 25 to 50% required an increase in the number of hours of CS from 1175.1 ± 135.6 to 1321.7 ± 117.6. The % of winter CS seeds were exposed to before germinating to 25 and 50% at 20/10°C was 40.8 ± 6.3 and 59.6 ± 6.6, respectively, for C3 species and 48.1 ± 6.6 and 66.7 ± 5.7, respectively, for C4 species (not shown).

Comparison of summer annuals included in both studies

For the 13 species (from the same collection) used in both the phenology and buried-seed studies, we compared the number of hours of CS before seeds began to germinate in the phenology study with the number of hours of CS before seeds first germinated to 25% at 20/10°C. We note that seeds in the phenology study were, for the most part, on the soil surface, and we could directly observe if they had germinated. Also, from the thermograph records in the glasshouse, we calculated the temperature of the week when the first seeds of a species germinated.

The mean (±SE) number of hours of CS required for seeds to begin germinating (first week) in the phenology study (1650.9 ± 88.6) was higher for all species than the number of hours of CS required for seeds to germinate to 25% at 20/10°C (1021.9 ± 86.8) in the buried-seed study (Table 5). The number of additional hours of CS for the first seeds of C3 and C4 species to germinate in the phenology than in the buried-seed studies was 679.8 ± 133.2 and 585.3 ± 146.7, respectively (not shown).

Table 5. Comparison of the number of hours of cold stratification (CS) required for seeds of 13 species of summer annuals to first germination (first week) in the phenology study (A) and at 15/6 (B) and 20/10°C (C) in the buried-seed study.

–, no germination at 15/6°C; A–B, additional hours of CS for germination in phenology study than in buried-seed study for seeds tested at 15/6°C; A–C, additional hours of CS for germination phenology study than in buried-seed study for seeds tested at 20/10°C.

A comparison of germination temperatures and number of hours of CS received prior to first germination for 12 of the 13 species used in both studies reveals three patterns of relationships. (1) For seven species, an increase in the number of hours of CS resulted in a decrease in the minimum temperature for germination. For example, after 1016, 1190 and 1238 h of CS seeds of Ambrosia artemisiifoia germinated at 15.0 (20/10 in incubator), 11.9 (in glasshouse) and 10.5 (15/6 in incubator)°C, respectively. (2) No germination occurred at 15/6°C, and there was an increase in the number of hours of CS before seeds germinated at 20/10° or in the glasshouse. Seeds of Mollugo verticillata received 1531 and 1733 h of CS before they germinated at 20/10 and 17.8°C (in glasshouse), respectively; those of Panicum dichotomiflorum 1509 and 1654 h of CS before germinating at 20/10 and 15.6°C (in glasshouse), respectively; and those of Euphorbia maculata 475 and 1770 h of CS to germinate at 20/10 and 17.5°C (in glasshouse), respectively. (3) There was a decrease in the number of hours of CS for germination at 20/10°C compared to the number of hours of CS required for seeds to germinate at 15/6°C. However, there was an increase in the number of hours of CS for germination at 15.3 and 18.3°C (both in glasshouse) for seeds of Persicaria pensylvanicum and Portulaca oleracea, respectively (not shown). Seeds of the 13th species Agalinis tenufolia, germinated at 15/6, 20/10 and 30/15°C in January after receiving 896 h of CS, but additional CS did not promote germination at 35/20°C (Table 5 and Supplementary Table S2).

Discussion

Our hypothesis that the entire length of the winter CS period in Kentucky is longer than that needed to break dormancy in seeds of summer annuals with PD is supported in part by data from the germination phenology and the buried-seed studies. For the 69 germination phenology studies conducted under natural temperature regimes, the % of winter CS that seeds received prior to the first week of germination ranged from 55.2 (Ambrosia artemisiifolia) to 98.4 (Amaranthus hybridus). For 25 of the 69 (36%) phenology studies, seeds were exposed to 90.8 to 98.4% of the hours of winter CS prior to the first week of germination. However, C3 and C4 species received 80.8 and 87.4%, respectively, of the total number of hours of CS during winter before the week of first germination. In contrast, in the burial studies, C3 and C4 species were exposed to 40.8 and 48.1%, respectively, of the hours of winter CS before germinating to 25% at 20/10°C. Notably, in the 13 species used in both the phenology and buried-seed studies simultaneously 145 to 1295 more hours of CS were received by seeds, depending on the species, before they germinated in the glasshouse at natural temperature regimes than at the simulated April temperature (20/10°C).

For some of the 13 species included in both the phenology and buried-seed studies, however, seeds germinated in the glasshouse at temperatures more similar to 15/6 (=10.5)°C than 20/10 (=15)°C. Exhumed seeds of four species did not germinate at 15/6°C. Of the eight species whose seeds germinated at 15/6°C, two (Chenopodium album and Helianthus annuus) required fewer hours to germinate (178 and 250, respectively) than seeds in the glasshouse that began to germinate when the mean weekly temperature was 9.3 and 10.6°C, respectively (Table 5). Seeds of Ambrosia artemisiifolia germinated at 15/6°C and at 11.9°C (in glasshouse) and required 48 fewer hours of CS to germinate at 11.9 than at 15/6°C. Seeds of Panicum capillare required the same number of hours of CS to germinate at 15/6°C and at 9.1°C (in glasshouse). Seeds of Persicaria pensylvanicum and Portulaca oleracea required fewer hours of CS to germinate at 15/6°C than in the glasshouse at 15.3 and 18.3°C, respectively. Seeds of Pennisetum glaucum, Setaria faberii and S. glauca required more hours of CS to germinate at 15/6°C than in the glasshouse at 12.0, 12.0 and 16.9°C, respectively.

Although exhumed seeds of the C3 species Eclipta prostrata, Leucospora multifida and Lobelia inflata and the C4 species Cyperus squarrosus, Euphorbia maculata, Fimbristylis autumnalis and Panicum capillare species never gained the ability to germinate at 15/6°C, they eventually germinated at 20/10°C. On the other hand, exhumed seeds of the C3 species Heteranthera dubia, Rotala ramosior and Schoenoptectiella purshiana and the C4 species Cyperus esculentus, Eragrostis hypnoides and Leptochloa mucronata never gained the ability to germinate at 15/6 or 20/10°C, but they did germinate at 30/15°C. Thus, results for the buried-seed studies reveal that the germination of seeds of these summer annuals is delayed until the temperature in spring increases enough to overlap with the minimum temperature at which germination is possible. However, seeds can germinate if they are exposed to high temperatures (e.g. 30/15°C) as early as December and January, depending on the species.

The occurrence of Type 2 non-deep PD in seeds of 32 of the 33 species in the buried-seed studies means that the minimum temperature at which seeds will germinate in spring decreases as the length of the period of CS increases. However, even when seeds received the full number of hours of CS for the whole winter, the minimum temperature at which they will germinate varies with the species. The germination of seeds of summer annuals in spring is controlled by an interaction of (1) the number of hours of CS seeds have received, (2) how much the minimum temperature at which seeds can germinate has been decreased by CS and (3) the time of temperature increase in spring [See Figure 10.1 in Walck and Hidayati (Reference Walck, Hidayati, Baskin and Baskin2022) for a conceptual model of how these interactions can affect the timing of germination of seeds with Type 2 non-deep PD in spring.]. Type 2 non-deep PD can help explain the variation in germination temperature of the 14 species of summer annuals that germinated in the phenology studies in three consecutive years. That is, a mild winter with a relatively low number of hours of CS does not lower the minimum temperature at which seeds can germinate as much as a winter with a relatively large number of hours of CS. Thus, if the minimum temperature for germination is relatively low germination occurs in early spring. However, a relatively high minimum temperature for germination results in a delay in time of germination, unless there is a rapid warm-up in spring. More research is needed on the relationship between seed age and response to variation in the number of hours of CS during winter.

In general, C3 species germinate at lower temperatures than C4 species, and thus C3 species germinate earlier in spring than C4 species. Consequently, seeds of C3 species received a lower % of winter CS prior to the week of first germination than those of C4 species. The % of winter CS seeds received prior to germination increased as the temperature of the week of first germination increased for both C3 and C4 species. For 24 of the 69 datasets (17 species) in the phenology studies, temperature for the week of first germination was <10.5°C (mean 8.2 ± 0.3°C), and seeds had received 75.6 ± 1.9% of the total number of hours of CS by the week of first germination. On the other hand, 20 of the 29 datasets had a temperature of ≥ 15°C (mean 17.0 ± 0.3°C) during the week of first germination, and 90.2 ± 1.4% of the hours of winter CS had been received by seeds by the week of first germination. Seeds of summer annuals, except those of Agalinis fasciculata, Eragrostis hypnoides and Heteranther dubia, germinated at 30/15°C (=22.5°C) in September to January, depending on the species. Thus, we conclude that seeds of many summer annuals, especially C4 species, receive long periods of CS that basically are not breaking PD, but rather the low temperatures of winter are inhibiting/delaying germination.

The broad implication of our results is that temperature increases in eastern North America due to global warming (IPCC, Reference van Oldenborgh, Collins, Arblaster, Christensen, Marotzke, Power, Stocker, Qin, Plattner, Tignor, Allen and Boschung2013) will not inhibit seed dormancy-breaking in winter and thus will not delay germination of summer annuals in spring, if soil moisture is adequate. As mentioned above, timing of germination of summer annuals is controlled by the number of hours of CS received by seeds, how much the minimum temperature at which seeds can germinate has been decreased by CS and when (and how fast) the temperature increases in spring. The flexibility of each of these three variables and their interactions ensure that seeds of summer annuals can germinate in spring in a warming world but at slightly different times and temperatures each year. As seen from the differences in dates and temperatures of germination of the summer annuals that germinated in three consecutive years in the glasshouse, this control system is already in place.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0960258522000125.

Acknowledgement

C.C.B. was supported in part by HATCH Project (1013862).

Conflict of interest

None declared.