Introduction. Typology and typography as efforts of rationalization

To what extent can the material aspects of publishing processes affect the content of scientific and intellectual productions? Jack Goody’s pioneer works on the materiality of writing and cognition (Goody Reference Goody1977) have made a significant contribution to popularize the idea that causal relationship is a plausible hypothesis. Observing and identifying such relationships is much more difficult in practice, and they are sometimes overemphasized in programmatic statements. In his 1985 lecture on Bibliography and the Sociology of Texts, Donald McKenzie gave an example with his analysis of a quotation from a famous text on literature theory.

Addressing the debates on the reachability of one author’s intention, he examined the use of capitalization, quotation marks, and the accuracy of the copied words, aiming to show “that in some cases significantly informative readings may be recovered from typographic signs as well as verbal ones, that these are relevant to editorial decisions about the manner in which one might reproduce a text” (McKenzie Reference McKenzie2004, 18–22). Although this example is useful, it was the only case he gave involving typography.

Studies combining the history of print and the history of (early) sciences have greatly contributed to increasing the attention paid to the material production of knowledge. In his 1998 masterpiece, The Nature of the Book, Johns Adrian noted that in contemporary science studies,Footnote 1 “the universal character of science can be appraised as an achievement, warranted and maintained by situated labors,” but regrets that, to the contrary, “appreciation of print has too frequently stopped short at the doors of the printing house” (Adrian Reference Adrian1998, 41–42). Looking at the printing process and the multiple printed formats as instruments was key in overcoming this limitation.Footnote 2 Moving forward to twentieth-century science, such a perspective can be applied to the new printing formats that appeared at that time, in particular those related to computers. Looking at the effects of information technology on social ordering in scientific practices, Christine Hine studied changes in contemporary biology due to the use of computers. Investigating databases as instruments and means of communication, she stressed the difficulty in finding “evenly distributed and homogeneous effects,” observing that the database was rather an “additional ordering resource” (Hine Reference Hine2006, 291).

Drawing on this scholarship, this paper aims to re-examine the potential relations between publishing processes and the content of scientific productions, from a detailed case study in prehistoric archaeology in the second half of the twentieth century. This was a period when mathematics and computing were being gradually introduced into prehistoric archaeology. Two efforts of rationalization and standardization will be jointly analyzed: typography and typological thinking, respectively. Typography is the rationalization and standardization of graphic representations of linguistic statements.Footnote 3 It specifically includes the definition of the concepts and instruments required to produce graphic documents. Typology is one systematic method of scientific analysis, and is used in different investigative domains:Footnote 4 in philosophy,Footnote 5 in mathematics and logic with type theory, in sociology with Max Weber’s ideal type,Footnote 6 and in archaeology, to study the various objects made by ancestral humans, such as lithic typologies for prehistoric oustone tools. In this last field of investigation, typologies are of crucial importance because archaeologists aim to study human past realities without the possibility of relying on the discourses of past actors, thus making naming and categorizing central issues.

Typography and scientific investigations are characterized by their practitioners’ attempts to rationalize and standardize descriptions. As Adrian stated: “print, like scientific truth, attains the level of universality by the hard, continuous work of real people in real places” (Adrian Reference Adrian1998, 42). Whatever the phenomenon studied, efforts to establish classifications, taxonomies or nomenclatures are also based on such rationalization and standardization. In addition, typography and typology are related in various ways. First, typological thinking has been applied to typographical characters.Footnote 7 Second, and more generally, since the mechanization of publishing, establishing a typology is to establish relationships between 1) concepts; 2) linguistic representations; and 3) graphic representations. For example, lithic typologies can: 1) distinguish between the concepts of blade and bladelet; 2) use the syntagms “blade,” “pièce laminaire,” or “Klinge” (linguistic variation); and 3) print the character strings “blade”, “blade” (typographic variation) or “λεπíδα” (linguistic and typographic variations).

Attempts to standardize associations between conceptual, linguistic, and typographical distinctions are aimed at minimizing ambiguities. However, discrepancies between these three levels of rationalization are unavoidable, and this paper aims to empirically study these differences. It addresses the use and dissemination of a standard practice, as well as unexpected variations in this practice that have bypassed the effort of standardization. Rather than a scenario where the use of publishing formats and standards are rejected for their negative effects (excessive normalization or uncontrolled variation), I show that researchers can occasionally find resources to control and counterbalance the undesired effects of standardization. Identifying these effects does not refute the never-ending improvements that are made in attempts to control them.

To this end, this paper studies how archaeologists involved in the development of the “typologie analytique” method attempted to standardize typological methods for describing prehistoric lithic objects. This method was developed by the French archaeologist Georges LaplaceFootnote 8 (1918–2004) and then improved with his collaborators. It was one of the major proposals published during the second half of the twentieth century in the field of “lithic typology.”Footnote 9 Until the 1980s, the definition of such typologies was one of the main debated issues in prehistoric archaeological research in France. In this context, Laplace faced other researchers such as François Bordes (1919–1981), Denise de Sonneville-Bordes (1919–2008), and Jacques Tixier (1925–2018).Footnote 10 The proposals varied in how the different typologies were defined, how convenient the typologies were in practice and how proponents could teach them, how effective results could be generated, and whether an editorial space could be accessed to publish the results. I analyze the relations between these dimensions to show how, in addition to intellectual arguments, publishing constraints, from the level of editorial policies such as the selection of publication language or the defense of specific trends, to the typographical and technical level, can have transforming effects on scientific productions and practices.

The first section of this paper presents the typologie analytique method; the second section is a general examination of the editorial landscape in prehistoric archaeology in France from the 1950s to 1970s; based on the former data, the third section examines the difficulties encountered by the proponents of the typologie analytique method; and the last section addresses the publishing strategy they adopted to overcome these issues. This study is based on published materials, archives, interviews, and bibliometric data I generated.

Laplace’s typologie analytique and its notation system: Standardized expressions for describing lithic objects

The contents of the “typologie analytique” method have changed over time, from its first definition in the early 1960s to the last publications of its author in the 2000s. In general and in its most elaborated state, this method for the study of prehistoric lithic objects included a nomenclature, a notation system to encode the description of lithic objects, a set of typometrical methods (intended to characterize and classify lithic objects based on their metric dimensions), and a set of statistical procedures for collections of lithic objects (those from a same stratigraphical layer, for example).

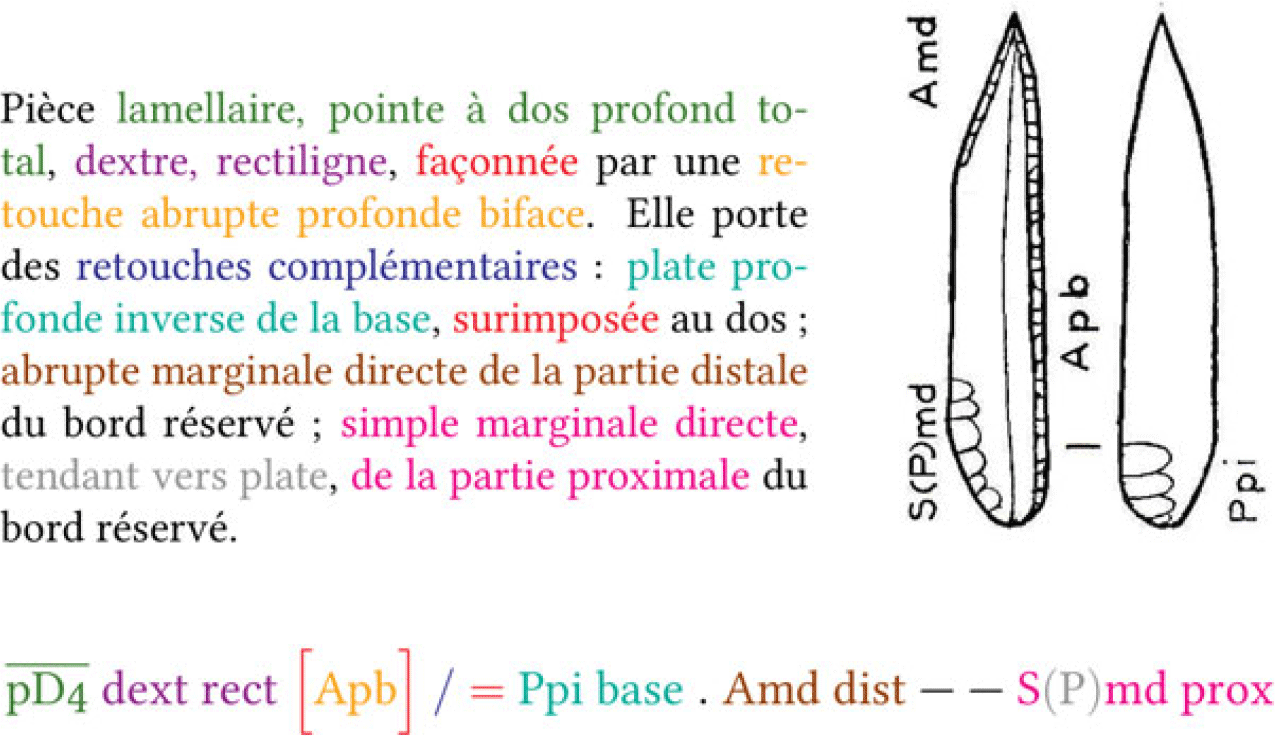

Throughout his publications, Laplace developed a practical method to encode the result of an analysis of a lithic object using his own nomenclature and notation system. To introduce his method, let us first consider that a lithic piece can be represented by a sentence in natural language (using a relatively systematized technical lexicon) and by a drawing (fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Example of textual, graphic, and analytic representations of a lithic piece (from Laplace Reference Laplace1968, 58). The text, in French, uses the technical lexicon of the typologie analytique method.

Laplace added to these modes of representation a third mode: using his method, the lithic piece described in the previous example can also be represented by the following character string (Formula 1).

The apparent complexity of this notation is the result of its gradual improvement. Let us briefly review how this notation system was developed. The two first versions of the lexicon (published in 1954 and 1956) were organized as a finite list of types, each being associated with a number. In 1957, Laplace defined a set of “symbols” formed by one or two letters, to note the typological groups (“groupes typologiques”). The primary types (“types primaires”) belonging to a typological group were noted by complementing this group symbol with a number (Laplace-Jauretche Reference Laplace-Jauretche1957, 138): for example, G1 for the “grattoir long” primary type (long scraper), or B7 for the hooked burin (“burin busqué”). From 1964, Laplace further systematized this notation (Laplace Reference Laplace1964, 70–71). He distinguished:

-

elementary symbols (“symboles élémentaires”), based on the previous rules for the notation of the primary types;

-

five basic graphic symbols (“symboles graphiques fondamentaux”), to specify the properties of a primary type or the association between adjacent primary types on the same object;

-

four supplementary graphic symbols (“symboles graphiques complémentaires”), referring to the technical properties of an object, or expressing the combination of primary types on the same object;

-

three sets of supplementary abbreviations (“abréviations complémentaires”), to describe the retouches.Footnote 11

Note that a difference is made between the “symbols” (alpha-numerical or typographical) and the “abbreviations” of natural language words by apocope: for instance, dext(re), dist(al), prox(imal) (see Formula 2).

Laplace gave some examples of how this notation could describe lithic objects. From 1968, the character strings generated with this method, which Laplace described as a “concise notation system,”Footnote 12 were called “analytical formulas” (“formules analytiques”, (Laplace Reference Laplace1968, 56–57). The method to construct these formulas was also described. They had to respect a specific syntax, such as:

with TPx and T’P’y being chosen from the set of primary type symbols, T’P’y being optional and used to complement the first symbol when two primary types can ambiguously describe the object under study. Laplace wrote:

Thus, we obtain an analytical formula, a genuine syntagma formed of significant units, i.e. elements carrying morphotechnical information, which is the only type of information relevant in typology.Footnote 13

In the example presented in fig. 1, the described object combines several properties. To express and clarify the relations between these properties, Laplace defined a set of operators (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Summary of the “signes analytiques” (Laplace Reference Laplace1968, 57), see Table 1 for an English version. Note the typographical mistake in the third line of the third column (la instead of le).

After 1968, this notation system became the essential characteristic of the typologie analytique for two main reasons. First, it operationalized Laplace’s scientific project and fulfilled its epistemic norms (methodological rigor, explicitness, universality, systematicity, analyticity). Secondly, this notation was a descriptive standard, complementing existing publishing formats, which enabled archaeologists to exchange data. Before addressing the use and limitations of this format, I will give a general analysis of the publishing field in prehistoric archaeology over the period when the typologie analytique method was evolving.

Publishing in prehistoric archaeology from the 1950s to the 1970s

In this section, Laplace’s offprint collection is used as a quantitative historical source to gain a general picture of the research community in prehistoric archaeology and to locate Laplace’s social position within it. It also gives a means to address some particular aspects of this field of practice, including its degrees of internationalization and multilingualism.

Offprints as an editorial format and historical source

To delimit the period of growth of the typologie analytique method, I start from 1949, the year of Laplace’s first archaeological publication, and end in 1973, when the second journal dedicated to this method was created, the Archivio di tipologia analitica. This journal was a key in diffusing the typologie analytique beyond its place of origin in France.

There is no general bibliographic database for prehistoric archaeology, which generally covers publications between 1949 and 1973. Therefore, I worked with a sample: Laplace’s offprint collection. Offprint publications are unique in that they are printed documents, generally sent personally by authors or editors to potential readers. In the second half of the twentieth century, this editorial format was still important for authors, because they contributed to their scientific sociability. Consequently, offprints are a relevant proxy to reconstitute the social networks of scientists. This importance is illustrated, for example, in the letters Laplace exchanged with his Basque editors about his contribution to a collective book in honor of the archaeologist Telesforo de Aranzadi (Laplace Reference Laplace1962):

I write this letter to inform you that I ordered not fifty copies of my work but one hundred […] I would, therefore, be very grateful if you could […] have fifty new copies printed (in the event, of course, that the typesetting has been kept). You would be doing me a great service because I still need one hundred copies of my articles for shipping and exchange. […] PS: I will pay you directly for the price of the offprints on my next trip to your country.Footnote 14

Laplace’s insistence, as well as the number of offprints requested, clearly indicate the importance of this editorial format. It is noteworthy that the author was paying for the supplementary copies. In using offprints as a historical source, they can be interpreted as a consequence of the social relationship between the author and the owner of the offprint, who are likely to have known each other. In this context, I aim to build a general picture of publishing in prehistoric archaeology. It can be argued that this method introduces a potential bias because interpersonal relationships determine the distribution of offprints. However, the large size of Laplace’s offprint collection warrants the representativeness of this sample.

The dataset was generated by merging two sources: Laplace’s files stored at the Musée National de Préhistoire in Les Eyzies-de-Tayac (France) and Laplace’s offprint collection at the Traces Laboratory of Archaeology in Toulouse (France). An inventory of the offprints from the Musée National de Préhistoire was found in the digital collection of the museum,Footnote 15 and the Traces offprint collection was digitally catalogued in a tabular format.Footnote 16 Information on 2962 offprints was obtainedFootnote 17; the sample corresponding to the 1949–1973 period includes 2014 items, related to 676 different authors.

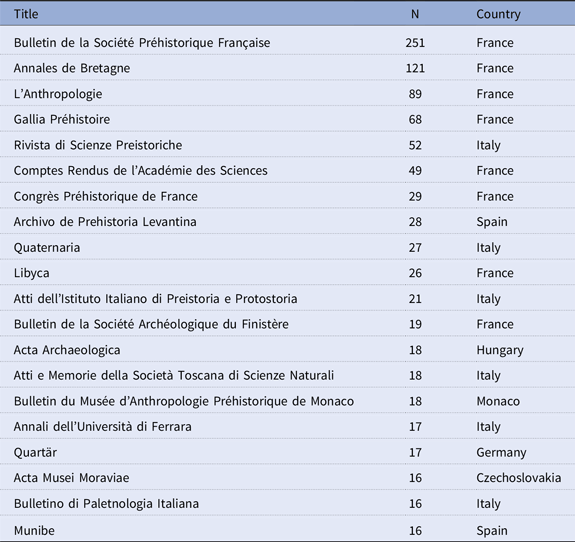

Practicing archaeology in a multilingual setting

In this study, I identified the most frequent journals (in which the offprints were published) and the frequencies of different languages used in the articles. Table 2 details the twenty most represented journals. It includes the most important French journals (Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française,Footnote 18 L’Anthropologie, Gallia Préhistoire), and also journals related to Laplace’s own intellectual interests and his personal network of collaborations. In this context, there is a high frequency of journals published in foreign countries where he conducted his research, such as ItalyFootnote 19 (Rivista di scienze preistoriche, Quaternaria), the French colonies in North Africa (Libyca), and Central Europe (Acta Archaeologica) from Hungary and Acta Musei Moraviae from Czechoslovakia). Similarly, two journals published in Brittany show the relations Laplace had with some prehistoric archaeologists from this region such as Pierre-Roland Giot (1919–2002) (Annales de Bretagne and Bulletin de la Société Archéologique du Finistère).

Table 1. The English version of the Summary of the “signes analytiques” (Laplace Reference Laplace1968, 57)

Table 2. Laplace’s offprint collection: the twenty most represented journals between 1949 and 1973 (916/2014 offprints): title, number of articles, and country of publication

The countries in which these journals were published do not necessarily reflect the languages used in their articles nor the nationalities of their authors. Although some French journals, such as the Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française only published articles in French, others, such as the Italian Rivista di Scienze Preistoriche, published articles in Italian, French, English, and German.Footnote 20 Consequently, the distribution of the publication languages must be examined more closely.

The language of each text was inferred from its title (fig. 3). Results confirm the effect of Laplace’s regional foci on the content of the offprint collection, as shown by the over-representation of work published in Romance languages and the notable presence of papers in Slavic languages. The distribution of languages also indicates two characteristics of multilingualism in prehistoric archaeological publications in the study period.

Fig. 3. Laplace’s offprint collection, number of offprints by language (2014 offprints). Note the logarithmic scale on the x-axis.

First, this particular collection reflects more generally a context of practice in which prehistoric archaeology was not bounded by the domination of monolingualism. Although the classic scientific languages (German, English, and French)Footnote 21 are present, other languages are prevalent: those spoken in the countries where fieldwork occurred and where archaeological research organizations have appeared more recently (Italy, Slavic countries).

Second, and also linked to this multilingualism, the methods and vocabularies used to build up lithic typologies diversified internationally from the late 1950s in Continental European archaeology. In parallel, an in-depth and uninterrupted discussion on the concepts of type and typology occurred in English-speaking archaeology from the 1940s.Footnote 22

In this context, the idea of a divide between the prehistoric archaeological scholarship produced in French and in English after WWII has been advocated and emphasized many times.Footnote 23 In the large and general monograph on typology by Adams and Adams, Archaeological Typology and Practical Reality, references to debates published in French and other non-English languages are absent, the authors frankly admitting that they “overlooked [them], because of [their] unfamiliarity with the literature in those languages” (Adams and Adams Reference Adams and Ernest1991, 266 and 276–277). In a later book by Odell, Lithic Analysis, the European debates are briefly mentioned, but only from the controversy between François Bordes and Lewis Binford, an American archaeologist and one of the major proponents of the “New Archaeology” approach (Odell Reference Odell2004, 6–7). However, on the contrary, Laplace’s offprint collection qualifies the assumption of a strict distinction. First, the idea of a bibliographic divide is not supported because research published in the Germanic languages is prevalent in this offprint collection. Second, nor is the idea of an intellectual divide supported since a quarter of the English papers addressed methodological issues and debates (29/117). Furthermore, there were clear similarities in the methods and epistemic assumptions between Laplace’s group and the contemporary proponents of the “New Archaeology.”Footnote 24 The typologie analytique method Laplace developed, grounded on rationalist and universalist principles, was seen as a remedy to the national and linguistic diversification of typological systems. Nevertheless, he and his collaborators faced several difficulties in promoting this method.

Typographical obstacles to a methodological innovation

The diffusion of the typologie analytique method encountered two main obstacles involving typography, which are addressed in this section: 1) intellectual obstacles, namely criticisms from other archaeologists active in southwestern Europe, who raised controversial issues almost independently of the similar debates developed in English-speaking prehistoric archaeology; 2) technical difficulties in finding editorial spaces to publish articles based on this typology, due to editorial and typographical reasons.

Typographical arguments in the criticisms of archaeologists

In this section, the typological debates in prehistoric archaeology are addressed from the perspective of how typographical arguments have been used by critics of the typologie analytique.

The American archaeologist Hallam Movius (1907–1987) and the French archaeologist François Bordes were among the main critics of Laplace’s method. Bordes was one of Laplace’s close friends during the 1950s (see Plutniak Reference Plutniak2017b, 122–23) but, then, turned out to be one of the strongest critics against the typologie analytique. He and his wife, Denise de Sonneville-Bordes (1919–2008), regularly published critical notes and reports in the L’Anthropologie journal, edited by their mentor Raymond Vaufrey (1890–1967). In 1963, then in 1965, Bordes published two consecutive notes against Laplace’s work. In the second one, entitled “À propos de typologie” (“About typology”), he wrote:

Research, in my opinion, should be directed towards a better knowledge and definition of types and subtypes, rather than towards name changes, or pseudo-mathematical notations. This notation is certainly useful for taking detailed notes but its use makes reading the publications difficult. It is also likely to produce typographical errors.Footnote 25

This typographical argument was reused a few years later by another prehistoric archaeologist also interested in methodological issues in typological research, Michel Brézillon (1924–1993). Before devoting himself to archaeology, he worked as the deputy director of a bookshop in Saint-Mandé (near Paris) in 1945. In the 1960s, he collaborated with an important actor in the field of prehistoric archaeology, André Leroi-Gourhan (1911–1986). In 1968, Brézillon published his PhD thesis as a book entitled La dénomination des objets de pierre taillée. Matériaux pour un vocabulaire des préhistoriens de langue française (Naming knapped stone objects. Contribution to a vocabulary for French-speaking prehistorians). On Laplace’s method, he wrote:

It should not be forgotten that, whatever the value of these descriptive formulas, they cannot constitute a language, since they only represent a means of recording individual variations within groups, whose boundaries often remain to be defined and which must, it is a necessity of thought, be represented by verbal expression.Footnote 26

Brézillon’s conception of the linguistic features of the “analytical formulas” is radically opposite to Laplace’s: he denies all similarities between the notation system of the typologie analytique and languagesFootnote 27 and, therefore, denies the relevance of linguistic analytical categories to describe this notation, namely categories such as “syntagma,” “word,” “phrase,” or those used by Laplace for the “analytical signs” (“sign,” “utterance,” “signified,” see fig. 2).

Furthermore, Brézillon believed that an analysis of typologies cannot avoid their discursive dimensions (as a consequence, he wrote, of a “necessary condition of thought”): as a matter of fact, Laplace’s analytical formulas cannot be spoken. However, all pasigraphies developed since the nineteenth century are similar in this respect, and so are programming languages. (Pasigraphies are artificial languages intended to be universal, which only exist as graphical and writing systems, such as Paul Otlet’s Universal Decimal Classification or the International maritime signal flags.)Footnote 28 Apart from epistemological issues regarding the status of symbols and artificial languages in science, it transpires that proponents of the typologie analytique also encountered difficulties on technical and typographical levels.

Printing and typographical constraints

An analysis of the editorial characteristics of the prehistoric archaeology journals must take into account two characteristics of this field. First, the most important journals were associated with powerful authors who influenced their editorial policies. For instance, the L’Anthropologie journal was co-directed by two rival professors of the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle, Henri-Victor Vallois (1889–1981) for physical anthropology and R. Vaufrey for prehistoric archaeology. In practice, it was almost impossible for a typologie analytique practitioner to publish in this journal due to the disagreements between these archaeologists.

These social and intellectual factors influencing the editorial policies of the journals were complemented by a second, technical, factor: the typographical resources available to the journals’ editors. The typologie analytique notation introduced characters not previously used in archaeological publishing.Footnote 29 A close examination of this notation cannot, therefore, avoid a pragmatic analysis, in the sense of a linguistic analysis of the realizations of this “language.” Here, I draw on previous studies of the material and typographical aspects of scientific publishing as a proxy to highlight social or cognitive aspects.

For example, from the case of the nineteenth-century printer Charles Louis Étienne Bachelier, and his printing company Mallet-Bachelier, Norbert Verdier studied the development of mathematical publishing (Verdier Reference Verdier2011). By comparing two prints of the same paper by Evariste Galois, the first from 1829 and the second from 1846, Verdier illustrated how the composition of fractions had improved, which reflected the professionalization of mathematical publishing.

In a different study, Norbert Verdier and Jenny Boucard addressed the case of the modular congruence in number theory, introduced by Carl Friedrich Gauss in his 1801 Disquisitiones arithmeticae. The authors examined the notation for modular congruence used in the Nouvelles annales de mathématiques journal, a journal created by Olry Terquem, which played an important role in the diffusion of Gauss’s work to mathematics teachers. Terquem introduced the use of a dotted ṗ to note a multiple of the integer p, considering that this notation is beneficial for mathematicians and typesetters. Boucard and Verdier also noted that the first use of the ≡ symbol to note modular congruence in this journal occurred in 1849 when the publication moved to another publishing house (Boucard and Verdier Reference Boucard and Norbert2015, 66). The narrow relations between notation systems and mathematical thinking has also been highlighted by Manuel Gustavo Isaac in his study of Gottlob Frege’s ideography. He showed how the rules of its formal symbolism reflect and made operational Frege’s ambition to combine the syntactic and semantic aspects of his theory of meaning (Isaac Reference Isaac2013, 215–25). Notably, Frege rejected the linearity of the writing of natural language and wrote the symbols of his ideography using the two dimensions of the graphical space of the page.

In a similar perspective, studying the editorial and material aspects of scientific publishing demonstrates that introducing formal methods into archaeology, which was an important process in the second half of the twentieth century, was not only an abstract and intellectual change. As shown by the case of the typologie analytique notation and by the group of researchers who developed it, this process also implies a practical means of recording and sharing information, determined by technical, intellectual, and social constraints.

This can be shown from the examination of two striking examples of symbols that were added to the typologie analytique typeset. Although these symbols were unusual in prehistoric archaeology they were necessary to write the typologie analytique formulas. This indicates that editors would have accepted the use of these symbols and that the printing companies requested to produce the journals would have had the corresponding typographical glyphs.Footnote 30 These two symbols were part of the “elementary” and graphic symbols included in the lexicon of the typologie analytique (fig. 2). In 1964, Laplace detailed their purposes:

At the level of primary types, the analysis of simple shapes, either multiple or composite, uses the elementary symbols of the typological list and with basic graphic symbols. The combination of these elementary symbols distinguishes between many secondary types, but greater precision can be achieved by expressing the complexity of a shape by using complementary symbols and abbreviations according to the morpho-technical details empirically observed.Footnote 31

The first example is the notation of the laminar featureFootnote 32 of lithic objects. It shows how the choice of symbols may have been influenced by typographical constraints. In a paper published in 1966 in the Italian journal Rivista di scienze preistoriche,Footnote 33 Alberto Broglio (1931–) and Laplace included this feature among those that could be described with their method:

laminar: the overlining of the primary type, signifying the laminar feature of a shape, will not be used in this study [Footnote 1: For strictly typographical reasons.]. The letters F or B will be used to state that a lithic piece was reduced from a flake or blade.Footnote 34

The word “surlinéation” used by the authors is clearly a neologism in French. From a typographical perspective, it corresponds to the use of the glyph, called “trait suscrit” in French classical typography vocabulary, and “overline” in the Unicode standard terminology. The use of this symbol in typologie analytique is as follows: a laminar piece described as a burin sur retouche transversale (burin on transversal retouch, fig. 4), would be coded “

![]() $\overline {{\rm{B}}7}$

”.

$\overline {{\rm{B}}7}$

”.

Fig. 4. Drawing of a burin sur retouche transversale (from Laplace Reference Laplace1968, 58).

In 1966, the Rivista di scienze preistoriche was printed by the Fratelli Parenti di Giuseppe printing company, located in Florence. As the authors noted, the unavailability of the overline typographical glyph prompted them to adopt another notation for the laminar character: namely, the prefixion of the primary type symbol by the glyph “L” as, for instance, “LB7.”

Two years later, Laplace published a paper in another Italian journal, Origini. Preistoria e Protostoria delle Civiltà Antiche. Footnote 35 Overlining glyphs was not a problem for the printing company requested to produce this journal, the Tipografia d’Arte A. L. Picchi, located in Tivoli. However, Laplace was aware that there might be other typographical limitations for a glyph used to represent a relation of composition, namely when a single lithic piece should be described by the association of two primary types or more. So, he advised archaeologists to use one of two glyphs, depending on the typographical resources available: either the glyph used in mathematics to express intersection in set theory (“intersection” glyph, ∩), or the glyph expressing the sum concept (“plus” glyph, +). This enabled the

[…] expression, if necessary, of the simple or composite technical characteristic of the essential retouch. The simple technical characteristic is expressed between brackets by a technical symbol, with notation of the relevant position and shape:

TPx position shape (T’P’y) [technical symbol]

A composite technical characteristic is expressed between brackets by a union of technical symbols or primary types, or by their combination, with a notation for the relevant position and shape. This intersection of two sets is noted with the plus sign in the absence of the intersection sign (∩):

TPx position shape (T’P’y) [technical symbol or primary type + or ∩ technical symbol or primary type].Footnote 36

Despite this solution anticipated by Laplace, his paper in Origini raised other typographical and printing issues. Figure 5 represents the different glyphs used in this paper to express the composition of two primary types. The printer used two different solutions to make the intersection symbol requested by the author: either an O or a Q glyph (using a different font from the Garamond font used for the main text) with its lower part truncated; or an inverted “u”, also using a different font. In both cases, the printer seems to have improvised a solution.

Fig. 5. The three glyphs used by the printer to note the relationship between several primary types, which compose an object (from Laplace Reference Laplace1968, 56–57). The horizontal lines indicate the x-height of the Garamond font used in the main text. This font is illustrated by the French word “ou” (“or” in English).

This comparison of papers published in the Rivista and Origini shows the consequences of the availability and inadequacy of the glyphs at the printers on scientific productions. In addition, there is another cause of typographical variation: mistakes made by the person who composed the text for printing (see fig. 2 for an example). For the paper in the Rivista, the printer had the glyphs that the authors required (Broglio and Laplace Reference Broglio and Georges1966, 65) to symbolize the relations of adjacency (em dash, —), and opposition (interpunct, ṡ) between two primary types. However, they were occasionally substituted by hyphens (-) and full stops (.), as illustrated in Figures 6 and 7. The article later published in Origini presents a more rigorous use of these glyphs: only full stops and em dashes were used.

Fig. 6. Typographical variation in expressing the relation of adjacency between primary types: hyphens and em dashes (from Broglio and Laplace Reference Broglio and Georges1966, 90).

Fig. 7. Typographical variation in the use of points to express a relation of opposition between primary types: full stops or interpuncts (from Broglio and Laplace Reference Broglio and Georges1966, 85).

The availability of typographical resources and their degree of standardization thus had direct consequences on the efforts of standardization made by Laplace and his collaborators in the field of archaeology. The standardization of digital font formats remains a crucial issue in computer science in the present day.Footnote 37 In addition, typographical habits specific to a discipline or an editorial field might also determine the final print of a scientific study. The glyphs presented above were problematic for printers who specialized in the humanities and who used to print archaeological or historical publications; however, the same glyphs would have raised no problems for printers who specialized in publishing mathematics or physics research.Footnote 38

To summarize, the method proposed by Laplace encountered two sorts of publishing difficulties: first, criticisms and refusals of other archaeologists; and second, editorial and typographical constraints. To promote their method and to avoid these obstacles, the proponents of the typologie analytique created their own editorial vehicles.

Editorial autonomy as a solution

Creating an editorial media and ensuring control over editorial processes, were means for the proponents of the typologie analytique method to gain autonomy. In this context, two journals were created: Dialektikê to publish scientific articles, and Archivio di tipologia analitica, dedicated to the dissemination of raw data.

Dialektikê: the voice of the Groupe international de recherches typologiques

From 1969 to 1989 Laplace organized annual typology seminars in Arudy (a village in the French Pyrenees). In 1972, he published the first issue of the Cahiers de typologie analytique, a journal intended to collate the studies and communications presented during the seminar.Footnote 39 From its second issue, in 1973, it was renamed Dialektikê. Cahiers de typologie analytique. Twelve issues were published from 1972 to 1987, totaling 633 pages. The print run of Dialektikê has not been recovered, except for the third issue published in 1975: in a letter, Laplace mentioned that 90 copies had been printed.Footnote 40 Dialektikê was symbolically sponsored by the Institut universitaire de recherche scientifique of the Université de Pau et des Pays de l’Adour.Footnote 41 However, it was only funded by the subscriptions of the seminar participants. It is worthwhile to review this initiative in terms of division of labor. On the one hand, the typologie analytique researchers committed themselves to producing the journal. Scientists usually disregarded the material production of journal editing as they considered it outside the scope of science, and this task was frequently delegated to the printers. To the contrary, the typologie analytique group engaged their time and personal instruments, such as typewriters,Footnote 42 in typographic compositions, notably facing the issues raised by the composition of mathematical formulas (fig. 8). On the other hand, this editorial work, including text copy-editing, registration of the subscriptions, shipment, and engaging in the network of journal exchanges with other institutions, was mostly done by Delia Laplace-Brusadin (1924–1997), Laplace’s wife.Footnote 43 Being formerly an Italian archaeologist, a specialist in etruscology, she cut-back on her research after she joined her husband in France, as many women have done throughout the long history of science.Footnote 44 Dialektikê was printed by spirit duplication at Pau University, so re-typing the text on a special paper was required. Brusadin’s crucial role in this task as witnessed by the occasional typing error, typical of an Italian native speaker writing in French (e.g. in the 1978 issue, “Typologie dell’industrie” instead of “Typologie de l’industrie”).

Fig. 8. Self-production of the Dialektikê journal: example of mathematical composition mixing typing and hand-writing (from Laplace and Livache Reference Laplace and Michel1975, 11).

In the second issue of Dialektikê in 1972, a note announced the creation of a new journal on typologie analytique:

Finally, we would like to announce the publication of Archivio di tipologia analitica on the initiative and in care of our friend Paolo Gambassini. This periodical is open to all those who may encounter typographical or other difficulties in making known the full data of their typological analyses.Footnote 45

In this note, typographical issues are stated as the first difficulty encountered by typographie analytique practitioners wanting to publish their data to ensure data accumulation and sharing. However, the “other” difficulties were much more restrictive. Two examples can be given: firstly, the limitation due to archaeological journals being edited by rival researchers (refusing papers based on the typologie analytique); and secondly, a more material issue: sufficient editorial space in books or journals to print these data.

Jacques-Élie Brochier gave examples of the first type of limitation when I asked him in 2012 to tell the story behind some of his publications. He published numerous papers with Michel Livache, being two of the most active members of the Arudy group (Livache participated in 19 seminars and Brochier in 6). Regarding one of their articles (Livache and Brochier Reference Livache and Jacques-Élie2003), Brochier explained that it was published in the Rivista di scienze preistoriche for three reasons: 1) it was first submitted to a famous French journal of prehistoric archaeology and refused without any reasoned criticism (he received two very short evaluations) but only, according to him, by ideological opposition against the typologie analytique; 2) to the contrary, “in Italy you are not considered as a terrorist if you wrote something related to the typologie analytique”Footnote 46; and 3) moreover, the Rivista accepted papers in various languages (e.g. Italian, French, English, German). About another paper, concerning the dating of the Chinchon prehistoric sequence, he said:

[…] I sent it to the Gallia journal, being sure it would be refused. Once again, for the same reasons: because it is grounded on the typologie analytique, and because it is a conception of the Upper Palaeolithic which current dominating group does not like. So, discussing the typologie analytique in a French national journal nowadays is not possible. Every time I tried, I understood that it was not possible because it was refused. So, it is not without reason that Michel [Livache] and I have always published in Italy. At the Rivista they have no problem with it. Italy, Spain, everything is fine.Footnote 47

Brochier sent his paper to Gallia in July 2012, a few months before our discussion. It was finally accepted and published two years later (Brochier Reference Brochier2016). This reflects how opposition against the typologie analytique has decreased over the years, mostly due to the generational renewal of researchers. After Laplace’s death in 2004, the typologie analytique collective experience has been gradually integrated into the disciplinary history of archaeology, and remains actively taught and practiced only in the Basque Country.Footnote 48

Considering the second type of limitation, namely the lack of space to print data, the Archivio di tipologia analitica, another Italian journal, was created to resolve this problem.

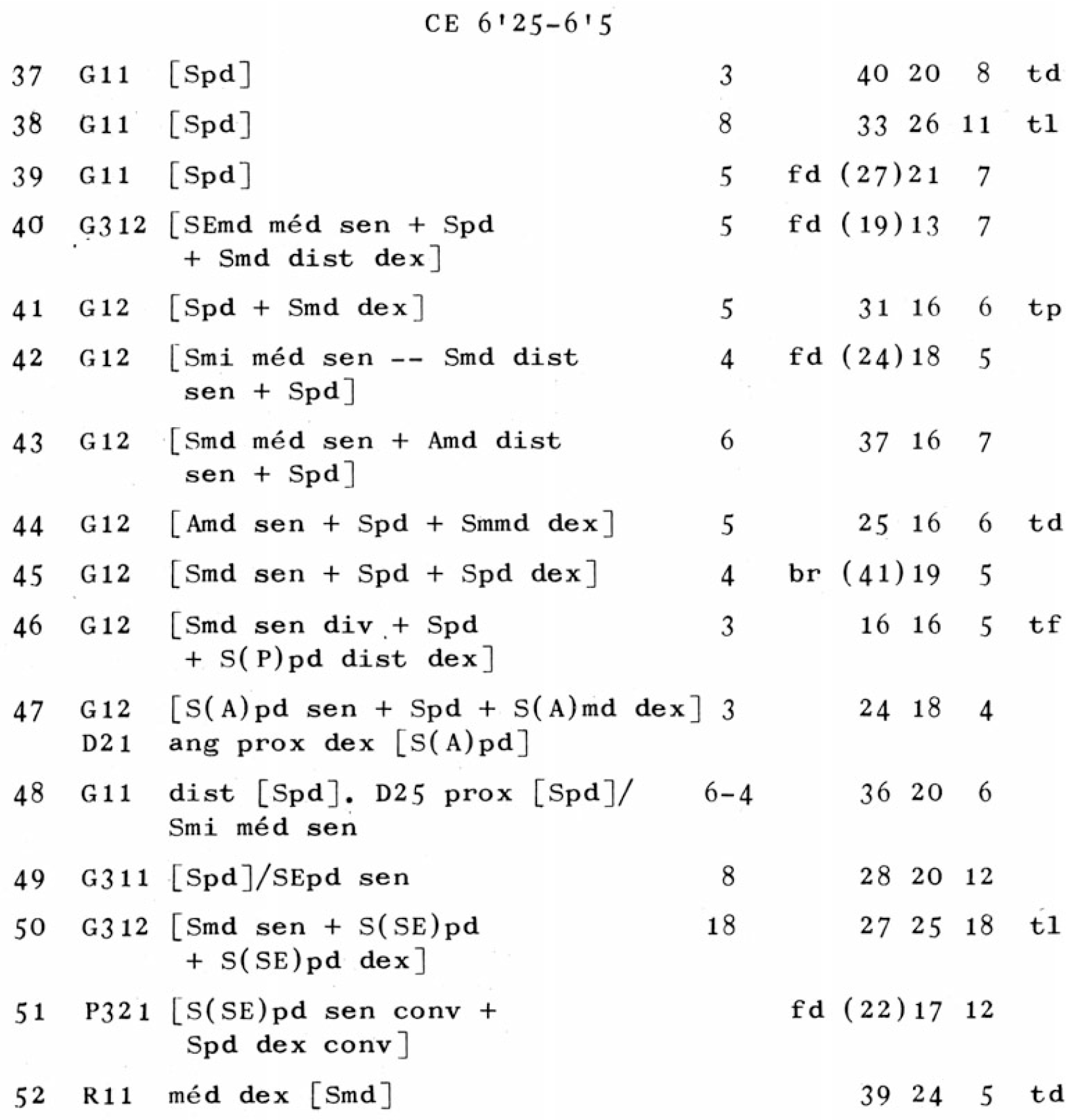

The Archivio di tipologia analitica: a controversial paper database

The Archivio di tipologia analitica was a periodical initially created at the Istituto di Antropologia e Paleontologia umana of the Siena University in 1973; it was not published until 1998. This journal was first edited by Paolo Gambassini (1973–1977), then by Annamaria Ronchitelli (1978–1983), Fabio Martini (1984–1992), and finally by Mauro Calattini (1993–1998). It aimed to publish prehistoric archaeology data studied by the typologie analytique method. A note published in the first issue detailed:

[…] full publication of data not only takes up considerable space in journals but it also creates typographical problems and induces high printing costs. Consequently, the complete set of data used in an analysis remain completely unused, as prehistorians limit themselves to keeping them in their personal archives.

These considerations gave rise to the idea of publishing these “archives”; although in a traditional and economical way, they will serve to circulate data that would have otherwise remained with a limited number of specialists.Footnote 49

The 91 articles published in the 21 volumes of the Archivio were – in most cases – related to another paper previously published in a standard journal, mainly in the Rivista di scienze preistoriche (23 percent) and in Rassegna di archeologia (9 percent).Footnote 50

Each article in the Archivio is divided into two parts. The first part, the shortest, contains a list of general information about the data set. With some occasional variations, this list includes:

-

the bibliographic reference of the related publication in which the data were summarized and analyzed;

-

the location of the archaeological site;

-

the name of the researcher who conducted the sampling or excavation;

-

the type of archaeological site (surface findings, stratigraphy, etc.);

-

if relevant, the stratigraphic layer of the archaeological material;

-

chronological information;

-

the number of objects studied;

-

the version of the typologie analytique taxonomy (occasionally more than one);

-

the notation system used.

The second part of the article, the longest, includes a list of analytical formula, each related to one lithic object, presented with metrical measurements of its dimensions. An example of the page layout of the Archivio is shown in fig. 9: this page is an excerpt from a 127 page-long article by the Catalan archaeologist Josep Maria Fullola i Pericot (1953–), describing 3424 objects from the Cova del Parpalló site (these objects identified 3794 primary types, since a single piece can have multiple primary types).

Fig. 9. Excerpt from (Fullola Pericot Reference Fullola and Josep1976, 15): for each object, the first column contains the object’s identification number, the second column contains the analytical formula, and the last columns state its metric dimensions.

This article describes an unusual number of objects; “articles” in the Archivio were usually shorter than this example. However, independent of length, each article contributed to the editors’ aim of accumulating data.

In this context, Figure 10 shows the yearly cumulative number of objects and primary types published in the Archivio between 1973 and 1998. The growth rate of this “paper database” is constant over this period; at the end a total of approximately 60,000 objects or primary types were described according to the typologie analytique method. The Archivio was first produce by the editors using a mimeograph, from 1973 to 1983, after which they used a professional printing located in Siena.Footnote 51 Despite this change, an introductory note in the 1984 issue informed readers that “the procedures for transcribing the analysis and introductory form remain unchanged,”Footnote 52 ensuring that data accumulation could continue.

Fig. 10. Yearly cumulative sum of the number of objects and “primary types” published in the Archivio di tipologia analitica. Source: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1235526.

One may think that data archiving is meaningless without a foreseen use of the archives. For archaeologists opposed to the typologie analytique it was out of the question to re-use their data. Some researchers of Laplace’s generation considered the Archivio as “rubbish,”Footnote 53 and this opinion is still echoed by some archaeologists from the younger generation today: for example, one source told me that the Archivio is nothing more than “fire-starting paper.”Footnote 54 Concerning the typologie analytique practitioners, so far, I have only met a few researchers who re-used the data published in the Archivio.

Regardless of the actual use of these data, and keeping as a principle the need to archive them, the Archivio’s contributors continued to maintain and to adapt this archive. In this respect, the use of computers from the end of the 1980s was a notable change regarding the material support of archaeological information, even if this change was made neither by Laplace nor by the Archivio’s editors.

Computer-based treatments of lithic analytical formulas

In the second half of the twentieth century, standardization, mechanization, automation, and computerization of typography were important steps in its technical development. All were mirrored in the development of the typologie analytique. Standardization through the typologie analytique method was not primarily intended for automatic processing; however, it gave de facto a precondition and led some practitioners, first, to elaborate on the relation between this method and computingFootnote 55 and, second, to implement computer-based extensions of the methods.

The first attempts were conducted in Italy, by Mara Guerri and Anna Revedin, two collaborators of Paolo Graziosi. In 1983 and 1984, they worked with Alessandro Casavola from the computing service at the Florence University. The latter wrote a Fortran program to format and process data according to the typologie analytique standard which included four functions: data recording, checking and correction of records, information retrieval, and the computing of statistics included in the “structural analysis” which was a part of the typologie analytique. This work was then published in the Rivista di scienze preistoriche (Guerri and Revedin Reference Guerri and Anna1986). With regard to the Archivio, its computerisation started even later in 1991, from its 16th issue, then directed by Fabio Martini. Subsequently, all the records were also stored on computer and diffused through 3½-inch floppy disk.

Many participants in the Arudy seminar came from Catalonia, besides Italy. Some of them contributed to the creation of the Departament d’Història de les Societats Pre-Capitalistes i d’Antropologia Social (History of pre-capitalist societies and Social Anthropology Department) at the Autonomous University of Barcelona. There, Rafael Mora Torcal and his colleagues developed a software for the statistical analysis of archaeological data (Mora Torcal, Roca i Verard, and Martínez Moreno Reference Mora, Rafael and Moreno1990). Input formats included the analytical formulas according to the typologie analytique.Footnote 56

Another computer implementation of the typologie analytique was elaborated by Michel Livache in France. In the 1980s, using a personal computer he bought himself (then, a significant financial expense), he wrote a Basic program that was able to read a list of analytical formulas, to parse them, and to summarize them with statistics. Livache considered that the typologie analytique – a method, he wrote, “that today we could call an expert-system”Footnote 57 – and contemporary developments in computing had important similarities. Livache published a description of his program in the penultimate volume of the Archivio, in 1997. He stressed the need to disambiguate the lexicon and notation of analytical formulas. Indeed, their non-computerized definitions and uses give some syntactic and lexical flexibility. This is due to the free use of abbreviations of natural language terms (in this case, French):

We use a three-letter code per feature as often as possible, two letters are often insufficient and ambiguous. If, by this method, we want to count the feature “PD”, the result will be the number of times the “PD” character string is encountered, either in PD, PDT, BPD or any other string containing the letters PD. This is why it is important to be wary of the CONvex, CONcave, CONvergent.Footnote 58

In addition to intralinguistic variations, interlinguistic variations must be considered since the practitioners of the typologie analytique had different maternal languages: see, for example, the differences between a French and two Spanish versions of a retouch analysis on the same object (Figure 11). Practitioners of the typologie analytique have never carried out a computer-based standardisation of these interlinguistic variations of their vocabularies.

Fig. 11. Linguistic variations in abbreviations: French original version (a, from Reference LaplaceLaplace 1974, 111, and two versions in Spanish (b, from Reference Sáenz de BuruagaSáenz de Buruaga 1991, 43, and c, from Fernández Eraso and García Rojas Reference Fernández Eraso and Rojas2013, 490.

Conclusion: towards Big Data. The persistent question of the materiality of representation systems

From the case of the typologie analytique in prehistoric archaeology I investigated the effects of several publishing processes on the organisation of scientific activities and the content of scientific productions. Close examination of publication languages, controversies, the production history of journals, and the use of typography, identified relationships in which technical, material, and social dimensions are combined. These include mixing intellectual and typographical arguments, restricting conceptual innovation due to technical unavailability of printing resources, limiting the definition of a shared communication standard due to linguistic variation, and competition regarding the correct standard to elect.

However, as also shown in this paper, archaeologists have managed to control these effects, attempting to increase control of the publishing workflow and, at the same time, to enhance the systematicity and conceptual clarity of their methods of description and analysis. This attempt by the typologie analytique practitioners was, at the end, also related to the general evolution of several scientific editorial forms due to the diffusion of computers. In this context, it is noteworthy that computer-based methods for the typologie analytique occurred late. This suggests that its crucial aspect was not automation, but rather the collective definition of a rational means of communication. This situation can be compared with a contemporary and famous case from the field of computer science, the TeX computer-based typesetting system. It was released in 1978 by the mathematician and computer scientist Donald Knuth (1938–) as a solution to what he judged as the low typographic quality of phototypesetting in mathematics. Besides being a modern typographical instrument, Knuth also considered TeX as a communication means, a format that might significantly change the collective practice of mathematics. This is illustrated in his wish that “Perhaps some day a typesetting language will become standardized to the point where papers can be submitted to the American Mathematical Society from computer to computer via telephone lines,” hoping that this language will be TeX (Knuth Reference Knuth1979, 345).

In the aftermath of the typologie analytique, a higher degree of standardization, which was previously one of the novelties and peculiarities of this method, became a common constraint for any archaeologist working with a computer. Moreover, the use of computer spreadsheets and database systems has increased de facto the level of standardization and explicitness of data in scientific practice since the very functioning of computers requires it (and even if the user does not know or does not use this improvement). The publishing format developed in the typologie analytique framework conceptually anticipated formats that are becoming increasingly common in archaeology and science today. A first example relates to the generalization of online publishing. Besides threatening offprints with extinction, online publishing has enabled the publication of large “supplementary materials” sections containing data, data descriptions, programming codes, etc. A second example concerns the use – although less developed – of online data storage services, and web semantic technologies such as ontologies and linked (open) data.

Nevertheless, this is not to say – far from it – that all the levels of rigor required by the typologie analytique practitioners have become common practice in archaeology today. The demand for data compatibility, accumulation, and sharing, and the use of a well-articulated and theoretically grounded set of statistical methods, is not widely adopted in the present-day prehistoric archaeology community. In this context, the issues raised by the typologie analytique practitioners in their time about the coding, archiving, and sharing of data remain of the greatest relevance today in archaeology and the humanities in general.

Acknowledgments

I thank Paolo Gambassini, Jacques-Élie Brochier, and Rafael Mora Torca, for accepting to be interviewed, and Georges Couartou, Stéphanie Delaguette, Dominique Trousson, Christine Cabon, and Maite García Rojas for sharing some of the documents and information with me. I am also grateful to the people who helped me in the archive services I visited: Marie-Dominique Dehé (archives of the Musée national de Préhistoire), and Anais Rodríguez (Sociedad de Ciencias Aranzadi). Finally, I thank Christine Rabier, Laureline Meizel, Jean-Marc Pétillon, and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on earlier versions of this article.

Sébastien Plutniak (M.A. in archaeology, PhD. in sociology, Ehess – School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences, France) is a sociologist and prehistoric archaeologist, former fellow of the École française de Rome. His research interests revolve around the use of formal and computer-based methods in the humanities and social sciences, from a socio-historical and epistemological perspectives. Archaeology during the second half of the 20th century is used as his main case-study, while also being interested in applying formal methods to a wide range of research topics from bibliometry in science studies to social network analysis in ethnography.