I

Arching around the Mediterranean, in the north-western corner of Italy, Liguria had been historically an important route for travellers going south. In the eighteenth century, Genoa was one of the principal destinations of the Grand Tour and in the nineteenth century, after the end of the Napoleonic wars, the number of visitors increased dramatically.Footnote 1 Travellers were encouraged by new roads and railways, which opened up additional landscapes with novel vantage points. Many travellers were amateur and professional artists who toured Liguria in search of picturesque subjects to depict for their own recollection or to exhibit in England.

In this article we make use of some of these views to examine how the modernised transport routes themselves became features and objects of especial interest and comment and released new places to become tourist attractions. Rural historians and historical geographers have frequently used art to examine the history of rural landscapes in terms of social and economic context, and technological changes.Footnote 2 Moreover, scholars increasingly recognise topographical views, often produced by amateur artists, as valuable sources to explore both past landscapes and the relationship between the artist and the places they depicted. Some have examined the works of artists who made views of places they knew well and whose style and content were influenced by an intimate knowledge of the landscape.Footnote 3 In travel studies, artistic representations have been used in combination with written accounts to explore the relationship between travellers, local people and places.Footnote 4

There is of course a long tradition of travellers to Italy making use of drawings to remind them of the places they visited. One of the most famous visitors, Goethe, explicitly described the importance of drawings in aiding his memory of views and buildings on his journey from Naples to Sicily. He employed the artist Christoph Kniep to accompany him and make detailed drawings on his behalf. Goethe praised Kniep's precision as a draughtsman at Paestum (23rd March 1787): ‘He never forgets to draw a square round the paper on which he is going to make a drawing, and sharpening and resharpening his excellent English pencils gives him almost as much pleasure as drawing. In consequence his outlines leave nothing to be desired.' While Goethe walked around the remains of the temple to ‘experience the emotional effect which the architect intended’, Kniep ‘was busy making sketches. I felt happy that I had nothing to worry about on that score, but could be certain of obtaining faithful records to assist my memory.'Footnote 5

In this article, we consider three artists: the English amateur artist Elizabeth Fanshawe (1776–1841) and two Italian professionals, Francesco Gonin (1808–1889) and Carlo Bossoli (1815–1884) who depicted contrasting rural Ligurian landscapes. In the analysis of the views we consider issues such as nationality, professional status and artists’ biography and upbringing. We question whether their production and choice of subject were influenced by artistic movements like the Picturesque and by the popularity of modernity and industrialism in Britain between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.Footnote 6 In this sense, artistic fashion and tendencies are strongly linked to the artists’ nationality, their professional status and their liberty in the choice of the subject.Footnote 7

We analyse the views in terms of their style, accuracy and content and document how these sources can offer insights into the landscape history of rural Liguria in relation to transport and modernity. We develop a methodology that draws upon multidisciplinary approaches to the landscape history of Liguria.Footnote 8 The views are compared to archival documents and historical maps, while field data and present-day photographs help to assess the style and accuracy of the views. As in other cases in Europe, contemporary travel books unveil approaches and relations between travellers, ‘travellees’ and places.Footnote 9 Since the 1820s, the number of guidebooks on Italy increased dramatically thanks to publishers like John Murray. As well as providing technical information on the routes, the guidebooks informed readers about the climate, geography and local customs and traditions. Their detailed analysis in relation to the subject of the drawings provides evidence of the artists’ approach and understanding of the physical and social landscape. By contextualising the views and comparing them to other documents and to the current situation, this article develops a specific approach to topographical art and assesses its value as an additional source for the landscape history of rural Liguria, with a specific focus on roads, railways and modernity.

The routes studied are the new road along the Riviera di Levante (eastern Riviera) from Genoa towards Tuscany; the routes of two roads from Genoa north across the Apennines towards the Po Valley and the new railway from Turin to Genoa. The artworks are wash, ink and pencil drawings and prints, which focus on features of modern roads and the railway in the nineteenth century.

II

Substantial improvements were made to road networks throughout much of Europe in the eighteenth century but the Republic of Genoa retained a poor and rudimentary system lacking bridges and tunnels. The mule remained the principal means of land transport while many long distance journeys were made by sea.Footnote 10 This poor infrastructure was due to a lack of investment under the ancien régime and the morphology of the territory: a narrow strip of land, between a rocky coastline and a steep chain of mountains. Transport routes were frequently interrupted by landslides, floods, snowstorms and bandits. Liguria's borders are very similar to those of the Republic of Genoa, one of pre-unified Italy's many formerly independent states that fell under the control of Napoleon in 1797 who instituted the Democratic Ligurian Republic and then incorporated it into France in 1805 as one of the départements réunis. With the end of the Napoleonic wars Genoa was annexed to the Sardinian Kingdom under the royal family of Savoy who decisively contributed to the unification of the country in 1861.Footnote 11

The French administration started to renew Liguria's main roads and the incoming Sardinian authorities took advantage of the partially completed works to build major roads along the Riviera and through the Apennines in the 1820s. New and efficient links between the port of Genoa and other cities of central and northern Italy were considered of essential importance for the development of the state. Later in the century (1853) the Sardinian Kingdom built the first railway line between Genoa and Turin. The increasing speed and comfort of new carriage roads and later railways transformed the way that rural landscapes were perceived.Footnote 12 John Ruskin is well known for his dislike of the introduction of railways and his preference for travel by carriage. He recommended that those interested in landscape should travel at ‘a carriage speed of four to five miles per hour with frequent stops as the best pace for gaining a detailed understanding of the landscape’.Footnote 13 For him ‘[t]he carriage windows afforded a permanent frame for picturesque views’ and when he travelled with his family as a young man they took ‘a leisurely itinerary’ and ‘sketches and notes were often rapidly taken and worked up, if at all, in the evenings’.Footnote 14 He disliked the increased speed of travelling brought by the railway, asserting that: ‘Going by railroad I do not consider as travelling at all; it is merely “being sent” to a place, and very little different from becoming a parcel’ and emphasised that ‘all travelling becomes dull in exact proportion of its rapidity’.Footnote 15

Ruskin visited Venice with his family in 1835 and when he went there again ten years later he wrote to his father telling him that he had travelled by carriage from Venice to Mestre ‘in order to recall to mind as far as I could our first passing to Venice’. He was appalled by the impact of the new railway on Venice:

The Afternoon was cloudless, the sun intensely bright, the gliding down the canal of the Brenta exquisite. We turned the corner of the bastion, where Venice once appeared, & behold – the Greenwich railway, only with less arches and more dead wall entirely cutting off the whole open sea & half the city, which now looks . . . like Liverpool.

Moreover there was ‘an iron station where the Madonna dell'Acqua used to be and groups of omnibus gondolas’ waiting for passengers. His father replied that ‘I feared all this was coming on us. These railroads will ruin every place & people will lose all poetic feeling. In this Country people become quite hardened & sheer Gamblers, in Railroads.’ He was pleased that they had seen ‘these Continental Towns before this mania began’.Footnote 16

The rapid evolution of transport in northern, especially Alpine, Italy was nostalgically reflected on by the writer and photographer Samuel Butler (1835–1902). He visited northern Italy regularly in the 1880s and the 1890s and noticed that ‘[t]he close of the last century and the first quarter of the present one was the great era for the making of carriage roads. Fifty years have hardly passed and here we are already in the age of tunnelling and rail-roads.’ He reflected that the speed of improvement was increasing rapidly:

the first period from the chamois track to the foot road, was one of millions of years; the second from the first foot road to the Roman military way, was one of many thousand: the third, from the Roman to the medieval, was perhaps a thousand; from the medieval to the Napoleonic, five hundred; from the Napoleonic to the railroad, fifty.Footnote 17

III

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries those wishing to travel south from Genoa towards Tuscany still often preferred to sail down to La Spezia or Leghorn (Livorno) rather than take the coast road with its perilous mountains and dangerous river crossings. Mariana Starke recommends to ‘travellers in general and invalids in particular to come by sea’ by hiring a felucca from Genoa to Leghorn.Footnote 18 In 1802 Eustace sailed from Leghorn to Genoa on board Captain Gore's frigate that ‘delivered us either from the dangers of a passage over the Maritime Alps, then infested by banditti, or from the inconveniences of a voyage in an Italia felucca, with the chance of being taken by the Barbary pirates’.Footnote 19

Some important work on improving the coastal road was undertaken by the Napoleonic administration, which decided to build a fast road to connect Paris to Rome and Naples via Liguria. After 1815 the new Sardinian government funded the construction of the Strada Reale di Levante, which was completed in the early 1820s.Footnote 20 The tunnels, which were an essential and integral part of the new road, were seen as a remarkable innovation and a sign of modernity in an area that had long suffered from the general underdevelopment of its infrastructure. The first one encountered east of Genoa was at Ruta on the landward end of the Portofino peninsula. The excavation and building of walls started in June 1818 and the stretch of road from Recco to Ruta was first tested in August 1819. The construction of the 75-metre long tunnel was not without difficulties: the engineer, Argenti, who was director for the Strada di Levante, told the Intendant General of Genoa De Marini, that more miners than the fourteen employed were required, that the workers were unskilled and that an accident caused by the improper use of explosives had caused several deaths.Footnote 21

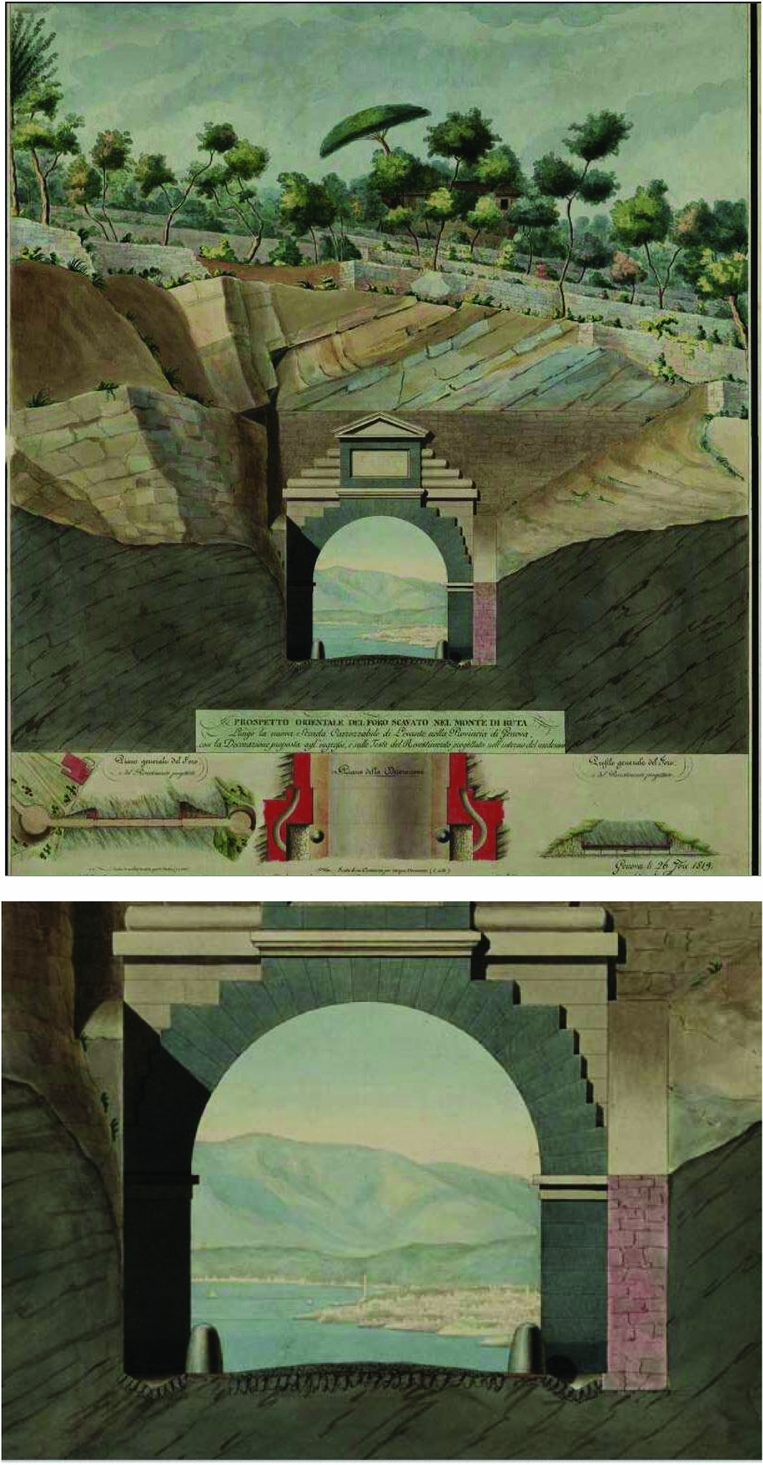

A drawing of 26th September 1819 made by Cav. Luca Podestá, who was the Bridge and Road Inspector of the Duchy of Genova shows the eastern façade of the Ruta tunnel (Figure 1). By 1819 the tunnel had already been completed, except for the decoration of its entrances and the covering of the interior, which are the object of this document. Along the bottom of the page three smaller drawings show the general plan of the tunnel, the plan of the decoration and the longitudinal profile of the tunnel. The proposed façade has a classical pediment and place for an inscription. Above the tunnel are the freshly cut faces of rock and the hill of Ruta. The view combines aesthetic appeal and accuracy of the technical characteristics of the tunnel. The rock cutting shows the detail of the geological formations that characterise the northern part of the Portofino Peninsula. These are the Flysch of Monte Antola, made up of alternating layers of marly limestone and clayey shales with occasional layers of limestone and sandstone. Their colour ranges from yellowish grey to dark grey, depending on the degree of alteration.Footnote 22 Watercolour is used to depict carefully the different tinges of the rock and the orientation of the strata.

Figure 1. Archivio di Stato di Torino, L. Podestá, Progetto orientale del foro scavato nel Monte di Ruta, 1819 (with detail).

Above the tunnel is a series of terraces sustained by stone walls; the clearly defined stones suggest that the terraces were recently built and the small size of the trees confirms this idea. These are mainly olive trees, with other small plants that are probably seasonal vegetables. A pine stands along the top of the hill next to a cottage; its particular umbrella shape suggests that it is a stone pine (Pinus pinea). The stone pine was very common in coastal areas of rural Liguria due to its importance as a source of pine nuts, while its bark was ground for the extraction of tannin.Footnote 23 The section of the tunnel shows the detail of the cobbled road and two black bollards to protect the walls of the tunnel from damage. The archway is made up of dark grey and light brown masonry with a neoclassic tympanum at the top, surrounded by a wall that secures the stability of the rocky outcrop above. At the opposite end of the tunnel lies the city of Genoa and its most distinctive landmark, the Lanterna.Footnote 24 This detail reveals that the view was more than a simple project plan, raising questions about its original significance. Genoa appears very close, and aspects of its landscape, such as houses and ships, are depicted in great detail. In the far distance are the Alps; between Genoa and the Alps lies hidden Turin the capital of the state to which Genoa had been annexed in 1815. The image celebrates how the new tunnel and road physically and symbolically reinforce the links between the old Republic of Genoa and the enlarged kingdom.

Five years later, Francesco Gonin produced two engraved prints of this stretch of the road as illustrations to Modesto Paroletti's description of western Italy seen through the eyes of two imaginary travellers, Viaggio romantico-pittorico attraverso le provincie occidentali d'Italia of 1824. Gonin spent most of his life in Turin and like Paroletti, who was a lawyer, had close connections to the Turin establishment.Footnote 25 His book and the pictures by Gonin are very much a celebratory description of the improvements undertaken by the Sardinian Kingdom. Riviera di Levante (Figure 2) depicts the landscape of the Paradiso Gulf viewed from the novello selciato (newly cobbled road) of the Strada Reale. The new enlarged road cut the slope at a medium altitude and climbs the mountain with a regular slope that made the journey comfortable and Paroletti emphasised the economic advantages that this safe, new road brought to Liguria.Footnote 26

Figure 2. Francesco Gonin, Riviera di Levante, engraving on paper, 293 x 355 mm, 1824.

Gonin's Galleria di Ruta (Figure 3) shows the completed eastern entrance to the tunnel and stresses the symbolic value of this new important infrastructure built by the Sardinian government. Gonin's view shows the façade with contrasting layers of stonework, but the decoration is simpler than that in the plan of 1819 and there is no pediment. The size of the tunnel is emphasised by the small figures, which seem dwarfed by it, and the efficiency and ease of the new tunnel is clear compared to the winding mule track climbing the steep hill that it replaced. The comparison between the old track and the new wide road emphasises the decisive contribution of the Savoy kingdom to the development of the territory. Today the tunnel is remarkably similar, apart from the heightening of a sustaining wall and the construction of a house to the right of the entrance (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Francesco Gonin, Galleria di Ruta, engraving on paper, 293 x 355 mm, 1824.

Figure 4. The Ruta tunnel, Charles Watkins, November 2017.

Once Paroletti's two travellers arrived at the ‘marvellous’ grotto or tunnel of Ruta, they stopped ‘to admire this work of modern engineering that provides to the eyes a scene that can be well called romantic-picturesque’. The entrance to the tunnel was ‘well built, with regular stones overlapping in order to create an oblong square over which lie rough cliffs supporting cultivated fields with olive trees’. Here everything ‘flaunts romantic beauty’ including the walls of the tunnel, the steep old path that leads up the hill, the surrounding trees and ‘solitude of the place’. When the travellers were inside the tunnel ‘the objects appear as if they were viewed through a camera obscura and the distant city of Genoa seems a painted miniature’.Footnote 27 This description is analogous to the similar 1819 drawing (see Figure 1), which shows the distant city of Genoa through the tunnel, suggesting that Paroletti might have come across the document.

The tunnel became an attraction for foreign travellers. Elizabeth Strutt described the Grotto as ‘pierced through the promontory’ and ‘a magnificent work: for the road, on either side, being open, the vault, loftier than that of St. Martin the Savoie, and the portal carefully finished and neatly adorned, the light penetrates throughout, and the vista formed at each approach is most striking.’Footnote 28 She was disappointed, however, that ‘the note is missing which gave the precise dimensions of this grand tunnel, and the name of the artificer who directed and accomplished this very useful communication’ and argued that ‘[s]uch works as these immortalise a sovereign worthily, by securing the lasting gratitude of his people.’ Travelling from Tuscany to Genoa in 1829 James Johnson enthused that ‘the whole bay of and city of Genoa, with all its mountains, promontories, forts, palaces, pharoses, signal towers, villas, harbour and shipping . . . burst unexpectedly on our view.’Footnote 29 Ruta and its view were very popular and the landscape of the Riviera from that ‘eagle's nest’ was the subject of a sketch by Turner in 1828.Footnote 30

The amateur artist Elizabeth Fanshawe (1779–1856) drew a tunnel on the same road on 18th November 1829. The sketch is part of a series of thirty-two topographical views of Liguria made during a trip through France and Italy between 1829 and 1831. Elizabeth was travelling with her two sisters Penelope (1764–1833) and Catherine Maria (1765–1816), who gained some popularity as a poet. Their father, John Fanshawe (1738–1816) was a wealthy courtier in the household of King George III and the sisters moved in a wide social circle including several poets and artists who knew Italy well. As a young amateur artist Elizabeth Fanshawe received several prizes for her landscapes. Her recently rediscovered Italian drawings provide evidence of Elizabeth's skills in depicting mountains, the sea, villages, roads and tunnels.Footnote 31 The tunnel of Figure 5 is one of the two tunnels on the new road between Rapallo and Sestri at Zoagli, ten miles to the east from Ruta. A contemporary map of Zoagli (Figure 7) shows the two tunnels of the new road cut into the rock and the sketch shows the steep, rocky side of a coastal mountain that is pierced by the new tunnel (Figures 5 and 6). Here the geological strata are clearly depicted by Fanshawe; with a few pen strokes she shows the roughness of the area and the fresh cut into this unstable rock. Mariana Starke described the two Zoagli tunnels as ‘delved in a rock of hard yellow marble, and lined with masonry: which destroys the beauty of the work’.Footnote 32 As in Ruta, the yellow marble is flysch of Monte Antola, that is characteristic of the coast from Genoa to Chiavari.Footnote 33 The danger of this part of the Aurelia was reported by Starke, who warned travellers of the ‘sad want of parapet walls’.Footnote 34 The area is still subject to rock falls and periodical landslides.Footnote 35

Figure 5. Elizabeth Fanshawe, ‘5 Gallery between Rapallo and Sestri, 18 from Genoa Nov 18th 1829’, pen drawing on paper, 135 x 130 mm, private collection.

Figure 6. The Gallery of Zoagli, Pietro Piana, September 2012.

Figure 7. Corpo di Stato Maggiore Sardo, Riviera di Levante alla Quarta della Scala di Savoia (1816–27), sc 1:9450 sheet 67, Archivio Storico IGMI (detail of Zoagli).

Both Fanshawe and Gonin emphasised the characteristics of the new road although the purpose of their representations was different. Gonin's views were celebratory and underlined the impact that these improvements had on the landscape documenting the written description by Paroletti. Fanshawe produced a series of drawings; the Ruta and Zoagli tunnels constituted a particular element of interest, as underlined by contemporary road books, and Fanshawe's sketch was made on the site to record the image of this dramatic feature cut through the limestone strata high above the Mediterranean.

IV

The main link between Genoa and the Po Valley to the north, which passed over the Bocchetta pass, was also much improved in the early nineteenth century. In the eighteenth century this route was described as extremely steep and coaches were always at risk of damage due to the very rough ground.Footnote 36 In the 1780s efforts to improve it were personally funded by the Doge of Genoa, Giovanni Battista Cambiaso. Several projects were undertaken and drawings and plans showing new bridges, walls and rock cuttings were made.Footnote 37 In the early nineteenth century there was considerable public debate on the advantages and disadvantages of the Bocchetta and the Giovi roadsFootnote 38 and by 1816 some small lengths of the Giovi road had already been built.

It was argued by some residents of the Lemme valley that the Bocchetta route (24 miles) was considerably shorter and hence better for farmers and traders than the Giovi, which, if built, would be 36 miles. A tunnel from Baracche to Guardia dei Corsi, two localities along the Bocchetta would be 200 palmi long (c. 46 metres), which was shorter than the freshly made tunnel at Noli, on the Western Riviera (400 palmi, c. 96 metres).Footnote 39 They also argued that the Bocchetta road would be cheaper to maintain than the Scrivia, which required many bridges and tagli larghissimi (very large rock cuttings) that would be affected dalle acque (by floods) or by rovinose montagne (dangerous rock falls). The Lemme residents noted that the Bocchetta was only closed under exceptional circumstances, such as heavy snowfall, but the snow was quickly removed by a man called Pippo delle Baracche who lived in Baracche.Footnote 40

However, the residents of Lemme lost the argument and the Giovi road, which was started during the French period (1807), was completed after fifteen years work in 1823.Footnote 41 The new road was 8 m wide and linked Pontedecimo to Novi Ligure over a total distance of 43.3 km along the Polcevera and the Scrivia valleys. Despite poor funding, bad weather and fraudulent entrepreneurs, the French government completed the first stretch of the road from Pontedecimo to the start of the ascent of the Giovi Pass along the Riccò Valley in 1813. But financial problems caused by the Napoleonic wars in the 1810s brought works to a halt. In 1821 Lady Morgan reported that no progress had been made between 1814 and 1819, and travellers were forced to ‘encounter the almost perpendicular ascents, and broken rutted roads and precipices of the Bocchetta’.Footnote 42 Guidebooks from the 1820s indicate that the Bocchetta remained important and was regularly repaired. When Robert Heywood used it in 1826, a drag chain broke, which ‘might have been serious had not the road just there happened to be of new materials’.Footnote 43

A report on the state of the works of the Giovi road in 1816 by Tagliafichi, the Head of the Royal Engineers, referred to major problems caused by rain and flooding along the Riccò Valley, which however was already open to carriages as far as Migliarina (Mignanego). The Riccò and other small rivers were a significant problem because of flash floods that delayed construction and ruined parts of the road.Footnote 44 In 1821, one year before the road opened, a Riccò flood was ‘of such strength than even the oldest people did not remember a similar one’ and a sustaining wall collapsed on the road.Footnote 45 Frequent landslips and rock falls obstructed the road: on 18th May 1822 a road engineer reported a landslide along the brook of Creverina that obstructed the new road.Footnote 46 The floods of Christmas 1821, often referred to in contemporary documents, caused a landslide that blocked canals supplying water to Marquis Raggi's mills and ironworks at Ronco Scrivia; both were still obstructed by rubble in summer 1822. The same year a miller from Mignanego, Antonio Agosti, claimed compensation, as his mill was no longer fed by water after a bridge was built on the Migliarina Torrent.Footnote 47 In addition, concern about the effect of the Giovi road on the livelihood of residents of the Lemme valley continued when the new road was inaugurated in 1822 and protests took place in Novi.Footnote 48 Tolls were introduced to help fund both roads: for the Giovi road the toll stations were at Busalla and Armirotti (Mignanego), and for the Bocchetta at Molini di Voltaggio and Langasco.Footnote 49

Travellers’ diaries and letters provide evidence of road conditions in the early nineteenth century The novelist Alessandro Manzoni travelling from Milan to Genoa reported a terrible accident on the road after Arquata on 15th July 1827, when, during a violent thunderstorm, the reins of the horses broke, the coach toppled over and passengers were thrown to the edge of a cliff.Footnote 50 In August 1834 a flood destroyed the bridge at Isola that had been drawn by Elizabeth Fanshawe in 1829. William Brockedon described the bridge as ‘highly picturesque’ in his Road-Book from London to Naples but by the time his book was published, the bridge no longer existed.Footnote 51 This flood damaged large areas of Piedmont and Liguria, and the Giovi road was blocked for weeks by damaged walls and bridges.Footnote 52

Both a rock cutting and a sustaining wall are depicted by Elizabeth Fanshawe in one of her drawings of the Scrivia Valley. Her interest in the technical aspects of the roads of Liguria is demonstrated here by the considerable detail with which she showed the characteristics of a road which in 1829 had only been finished seven years previously (Figure 8). This stretch of the original Giovi Road is today no longer used as the new Strada Statale passes above it, and more effective rock cuttings, sustained by concrete walls, were made in order to enlarge the road in the twentieth century. Today the sustaining walls are still in good conditions, and made out of the local limestone, which was probably extracted from the bed of the Scrivia. As the Strada Regia dei Giovi was parallel to the Scrivia for its entire Ligurian stretch, the river is a recurrent subject in the drawings by Elizabeth Fanshawe.

Figure 8. Elizabeth Fanshawe, ‘Ronco 3d June 1829, 2’, wash drawing on paper, 165 x 115 mm, private collection.

She made one of these on 3rd June 1829 with the inscription ‘Val de Scrivia’, which we have identified as being drawn from a point on the new road near the village of Borgo Fornari, in the Municipality of Ronco (Figures 9 and 10). The view was identified from two known elements of the landscape of Borgo Fornari: the church of Santa Maria, which dates back to the twelfth century and the castle of Borgo Fornari, probably related to the same period.Footnote 53 The bell tower of the church, built in 1752, has a particular shape that differs from the other churches in the area; it is squat and slightly shorter than the others, with a small middle part with a square section.Footnote 54 The ruined castle, church, dense woodland and torrent form a characteristically picturesque ensemble for Fanshawe to capture. Moreover, this is only one of the nine surviving drawings of the area, six of which she was able to make on 3rd June 1829 on her rapid journey with her sisters along the smooth and fast new road through the Apennines.

Figure 9. Elizabeth Fanshawe, ‘Val de Scrivia June 3d 1829 / 7’, wash drawing on paper, 116 x 168 mm, private collection.

Figure 10. River Scrivia at Borgo Fornari, Pietro Piana, October 2012.

In the drawing, the area immediately above the banks of the Scrivia appears densely wooded on both sides of the valley, apart from around the church of Borgo Fornari, which in the nineteenth century was an independent settlement called La Pieve. The right side of the valley, in the left foreground of the drawing, is identified by the local name Salmoria, which is the name of an isolated group of houses connected today to Borgo Fornari by a bridge. In 1839 the Forestry Commission of the Sardinian Kingdom produced a survey of these woods that exempted them from any exploitation due to the danger of hydrogeological instability. One of the areas described in this report is a wooded field of castagni d'alto fusto (timber chestnuts) in Salmoria in the Municipality of Ronco Scrivia (property of the Raggi Marquises), which was subject to landslides and rock falls.Footnote 55 A contemporary document identified another property in the area, along the side of the river, where it was recommended that a plantation of trees should be created to keep landslides under control, according to a law of the Sardinian Kingdom.Footnote 56

The improved travelling conditions of nineteenth-century Liguria and a period of relative political stability encouraged an increasing number of visitors to tour Liguria. Many, like the Fanshawe sisters, would have travelled on their own, taking advantage of a good number of post stations and hotels. The road between Turin and Genoa through the Po and the Scrivia Valley had eleven post stations of which one, Ronco in the Scrivia Valley, had a comfortable inn, the Croix de Malte, newly established by a woman who had lived nine years in England.Footnote 57 The safer travel conditions and smooth, fast roads provided more opportunities for stops to be made to admire, discuss and sketch views and scenery; the roads themselves often featured in these drawings. In the Giovi views by Fanshawe, for example, eight drawings out of nine were made from the roadside and six depicted a road feature or a bridge. Fanshawe and other travellers of her time travelled at the speed of travel liked by Ruskin, stopping at post-houses, dealing with coachmen and innkeepers, experiencing the living landscape of different parts of Liguria. This type of experience was soon to change, however, with the construction of the first railway between Genoa and Turin, which opened in 1853 and revolutionised the concept of travel in Liguria as elsewhere.

V

The railway between Turin and Genoa, which was opened in December 1853, was the first line completed in Liguria by the Sardinian Kingdom. It was strongly promoted by Camillo di Cavour, a deputy in the Sardinian parliament who became finance minister in 1851 and prime minister in 1852 and who saw railways as an important means of uniting Italy.Footnote 58 A satirical caricature by Casimiro Teja (1830–1897) shows Cavour, helped by the politicians Bettino Ricasoli and Urbano Rattazzi, astride a railway engine, metaphorically the kingdom of Italy, following Garibaldi towards the South (Figure 11). The first five miles were completed by 1848 and eventually there were twenty-six stations, including Asti and Alessandria. Its route was then through the Apennines following the Scrivia valley and the Strada Regia dei Giovi. By 1860 there were four trains daily between Genoa and Turin and the journey lasted between four and five-and-a-half hours.Footnote 59 The opening of the railway was recognised as crucial for the economic development of the kingdom as it linked its principal port with its capital and central Europe. The costly project, unlike in other parts of Italy, was entirely state funded with borrowed foreign capital, British in particular. The line soon carried the most freight in Italy and the port of Genoa developed rapidly, decisively contributing to the industrialisation of northern Italy in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Figure 11. Casimiro Teja, Da Torino a Roma ventitre anni di viaggio, alfabeto di Pasquino, 1872.

Many Italian and foreign engineers were employed in the project, which was especially ambitious as the line had to cross the Apennines and several rivers. The Giovi tunnel was the biggest challenge and Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806–1859), the internationally famous designer of bridges, tunnels and steamships, was consulted in 1843, but the job went to Piedmontese engineers supervised by the Belgian engineer Henri Maus.Footnote 60 This gigantesca opera (gigantic work) was 3,250 m long and crossed the main ridge about 110 m under the road, reaching a height of 360 m with a gradient of 3 per cent.Footnote 61 But the whole line crossed complicated territory, particularly the southern stretch between Arquata and Genoa. The upper Scrivia Valley from Busalla to Ronco was characterised by narrow gorges and unstable slopes, making it necessary to build a series of tunnels and bridges including the technologically innovative bridges of Mereta and Prarolo, the latter crossing the narrow valley obliquely with a single helicoid arch 450 m in radius.Footnote 62

The symbolic and practical importance of the Turin-Genoa railway to the kingdom is indicated by the commissioning of a leading topographical artist to provide a series of sixteen tempera drawings celebrating its most important features. In February 1851 Carlo Bossoli was paid 4,000 Swiss francs by the Sardinian Minister Pietro Paleocapa to undertake this task.Footnote 63 Bossoli had been born in Switzerland but grew up in Odessa and became well known for his drawings of Crimea in the early 1840s. He returned to Europe to live in Milan in 1843, continued to travel to England, Spain and Morocco and settled in Turin in 1853. Bossoli worked on the views for almost a year between 1851 and 1852 while the railway was being completed. Paleocapa prioritised the prompt publication of the views as a way to celebrate and even anticipate this historical event. In 1853 the drawings were published in England by the well-known lithographic printer William Day the younger (1823–1906) of Day & Son as tinted and partly coloured lithographs made by T. Picken, W. Simpson, E. Walter and R. Thomas from Bossoli's original temperas.Footnote 64

The collection includes views of the Ligurian stretch of the railway, including a view of the lower part of the Polcevera Valley near Sampierdarena, a viaduct on the Riccò River near Pontedecimo, the entrance of the Giovi tunnel at Busalla, the galleries of Villavecchia and Pietrabissara and the bridge of Prarolo. The first edition published in England consisted of an album of sixteen loose lithographs, a frontispiece and a list of illustrations. In the same year the views were published by Giuliano to illustrate a comprehensive guidebook on the railway with practical and tourist information.Footnote 65 The views focus on the details of the railway, underlining their technological innovation in the landscape of the Scrivia and Riccò Valleys. The morphology is often exaggerated, with steep, bare and rocky slopes, narrow gorges or wide, open valleys. Bossoli modifies the topography of the area to emphasise the great feats of engineering prowess embodied by the new railway and its visual impact on the landscape of the valley. Although his views focus on the railway, the pictures often depict other elements of the landscape such as villages, churches, roads and castles.

Bossoli's view of the Riccò Valley shows the stretch of the railway a few miles south of the entrance to the Giovi tunnel (Figure 12). Unlike the other Ligurian drawings, where the railway occupies the foreground, here it has a more marginal position. The foreground is dominated by the Riccò River, which is shown full of water and tumbling over rocks towards the viewer. The rocky banks of the river are emphasised and on the left of the image there is a bend of the Giovi road, which had been opened thirty years earlier in 1823. This is depicted wider than in reality and is thronged with people and busy with carts hauling goods. To the right of the river is a group of buildings including a substantial mill. In the distance there is another group of buildings, several farmhouses surrounded by fields are shown on the slopes and there is a village with a church tower on the top of one of the wooded hills of the Apennines. The large mill in the foreground, with its carefully depicted overshot mill wheel to the modern viewer establishes the drawing in the picturesque tradition of landscape art and this is reinforced by the washing drying on the rocks and on a line to the right of the picture. It is a settled, peaceful, rustic ensemble, which contrasts with the rushing waters of the Riccò and the busy road.Footnote 66

Figure 12. Carlo Bossoli, Viadotto sul Fiume Riccò, 1853, 448 x 608 mm, tinted lithograph, Genova, Centro DocSAI coll. Topografica.

The modern railway is shown slicing through this picturesque yet productive landscape. The setting emphasises the massive scale of the stone embankments on which the railway is laid and the stone walled cuttings above the line. The magnitude of these works was commented on in Murray's guidebook published in 1860 which provides a vivid description of this stretch of the railway: ‘emerging from the tunnel we enter the valley of the Polcevera, which the Rly follows, to near the gates of Genoa. The works of the railroad in all this extent have been admirably constructed, the greater portion of the line being on terraces of solid masonry or on gigantic embankments.’Footnote 67 Despite its marginal position, the railway is depicted in detail, with its impressive, smooth, sustaining walls, an arch over a little brook, drainage holes and a short tunnel. Moreover, the embankment was constructed in such a way that the mill race could continue to power the mill so that the local economy was not disrupted. The steepness of the ascent, which in this stretch reaches a gradient of 3 per cent, is accurately rendered by Bossoli, who shows two trains approaching each other, indicating that this was a double track railway. The depiction of the telegraph poles and wires, which follow the railway line, increases the idea of progress and modernity. These modern forms of transport although clearly visible in the landscape appear to be in a different world to the people gathered by the mill below and travelling along the road.

The drawing appears to be a composition of several elements of the landscape of the upper Riccò Valley between Mignanego and the Giovi tunnel. Fieldwork in 2017 showed the mill and two buildings next to it still in existence. The railway, which is currently part of the Genoa – Arquata Scrivia line and used for local trains, is almost invisible, hidden behind the thick growth of trees. The distant church in the background can be identified as the church of Giovi; as well as the short tunnel, but these are only visible from a different spot near Pile, where a newer railway bridge was built at the end of the nineteenth century as part of a second, faster railway linking Genoa to Turin and Milan, which opened in 1889.

Bossoli provides views of several impressive bridges and tunnels between Ronco and Novi, such as the viaduct and tunnel of Pietrabissara and the bridge of Prarolo. The picture titled Ponte sullo Scrivia sortendo dalla Galleria di Villavecchia (Figure 13) depicts a bridge near Ronco, crossing the Scrivia, which is here at one of its widest stretches. Coming from north, this five-arched bridge was located at the end of the tunnel of Villavecchia, which was 400 m long. According to Giuliano it was built by a group of engineers under the supervision of Engineer cav. Ronco. The viewpoint is from the road above the railway, and as in Figure 12 two trains approach each other. Again, the road is busy but in this instance some of the passers-by are shown looking down at the trains. Fieldwork indicated that the bridge and road were accurately represented, similarly to the width of the river (Figure 14). Bossoli emphasised the rocky form of the mountains, though like other nineteenth-century views of the Scrivia and other parts of Liguria, the extensive spread of naturally regenerated woodland softens the form of the hills and also hides views of the village of Ronco.Footnote 68

Figure 13. Carlo Bossoli, Ponte sulla Scrivia sortendo dalla galleria di Villavecchia, 1853, 448 x 608 mm, tinted lithograph, Centro DocSAI coll. Topografica.

Figure 14. The bridge of Villavecchia, Pietro Piana, July 2017.

VI

The success of the Turin–Genoa railway was soon followed by the promotion of new railways, including one along the coast from the French border eastwards towards Tuscany. By the 1870s railways were a fully accepted mode of modern transport and there was no celebratory set of drawings published for this line. Indeed travel writers were more likely to be aggrieved by the slow pace of its construction than astonished by the technical and engineering feats overcome. The complex topography meant that the construction was particularly challenging and the railway was only completed in 1874 with the opening of the Sestri Levante–La Spezia stretch, in the Eastern Riviera.Footnote 69 Work also proceeded slowly in the Western Riviera and was suspended in 1865 due to a disagreement between the government and the contracting company.

Henry Alford, Dean of Canterbury, who was commissioned by his publishers to write a travel guide for the Riviera illustrated with his own drawings, provides a remarkable first-hand account of its construction. He notes that ‘[o]ne of the curiosities of the Riviera, during the seven years of my acquaintance with it, is the future (?) railway from the French frontier towards Genoa.’ The interruptions meant that ‘its finished tunnels, its stacks of rails laid ready, from Bordighera onwards, its little bits of embankment cropping up here and there, have long ago become venerable institutions.’ The delays in construction meant that the ‘bits of embankment have become sylvan with great yellow euphorbias; the stacks of rails have turned “like boiled lobsters” from black to red; and the country people have established short cuts through the tunnels.’Footnote 70

Alford thought that the slow rate of construction could have been due to the inefficient French method of building embankments and that they should use the ‘self-tilting trucks’ used by British. He wondered who was responsible for ‘this ridiculous engineering’ and that ‘at the rate it is now going on, the line to Mentone would take as many years as the Italian line will take centuries’. He had also heard a rumour that the Italian government was worried about the possibility of ‘bombardment from the sea’ and was thinking of building a different line further inland.Footnote 71 On his walk along the coast he took a shortcut between Noli and Spotorno using ‘one of the long unfinished tunnels of the future railway, having enquired previously of the workmen the practicability of so doing’. Using railways as footpaths was quite a common habit. But Alford advised his readers against doing the same: ‘Before reaching the middle, I was wrapped in total darkness, and splashing ankle deep in water and mud.’Footnote 72 When he approached Genoa he used the new train from Sestri Ponente and complained bitterly about the inconvenient rules: ‘You are exhorted to be at the station full half an hour before the train starts. You are locked into a miserable sala d'aspetto, losing your time and liberty.’ Moreover, the train is ‘as often as not, even though it has but twenty miles to run altogether, half an hour or more late’ and consequently the ‘Sestri omnibuses have it their own way’ and hundreds of people used them ‘rather than incur the expense and trouble of the train’.Footnote 73

But despite these kinds of criticism the line along the western Riviera was successfully completed by the early 1870s and soon became very popular, encouraging thousands of visitors to coastal resorts, which grew rapidly. Bertolotto and Pessano (1871) describe the journey between Savona and Ventimiglia providing technical information on the line, as well as historical and geographical notes on towns and stations. During the trip, visitors could enjoy beautiful views of the coast and the hills. From the station of Albenga, the ‘enchanting’ view stretched across one of the few flat and fertile areas of Liguria up to the Maritime Alps. They argued that the stretch between Ospedaletti and Sanremo, which runs almost continuously along the coast for 5 km, was particularly pleasant. Moreover ‘no other station was more seductive to the eye of travellers than Bordighera’. Footnote 74

Travellers and artists took advantage of these new viewpoints and depicted views of the coast. The clergyman George Douglas Tinling (1844–1880) made two views in the western Riviera in 1878. The first, dated 25th February 1878, titled From the Station in Bordighera looking West is a watercolour showing a stretch of the Ligurian coast. The second watercolour, dated 12th March 1878, is Alassio from the Railway – En passant. Tinling drew the parish church of Sant'Ambrogio with its medieval bell tower and the eighteenth-century dome from his railway carriage. Bordighera and Alassio were both in this period rapidly developing as major resorts for British visitors and residents and most of this growth was a direct consequence of the opening of the new railway. Guidebooks such as those by John Murray and Baedeker helped to encourage travellers to make use of the new routes, and the railways were vital in transforming the small coastal towns of the Italian Riviera into wealthy resorts for the international elite. Italian artists also celebrated the arrival of the railway. La Via Ferrata (1870) by Tammar Luxoro (1825–1899) celebrates the modern era of transport; it was a popular image and was engraved by Ernesto Rayper (1840–1873) and the print was renamed Riviera ligure.Footnote 75 With the opening of the Chiavari–La Spezia stretch in 1874 Pasquale Domenico Cambiaso (1811–1894) depicted some views of this impressive stretch of railway including a watercolour of the station of Framura.Footnote 76

VII

The improved roads of the early nineteenth century opened up new views to be enjoyed by British travellers. Some like Elizabeth Fanshawe already had a sensibility cultivated to enjoy picturesque scenery that ‘encouraged the eye to play over its rugged fragments, picking out the suggestive detail, or to glimpse half-concealed vistas . . . relishing the sudden, unexpected or dislocated item.’Footnote 77 The new roads produced a succession of views of rivers, mountains, bridges, castles and local people, which she drew. Their routes passed along rapidly flowing rivers and traversed dramatic, almost sublime, cliff tops with vertiginous views of the sea far below. She was also fascinated with the road itself; almost all her drawings have the road as foreground; but some, like the new tunnel between Rapallo and Sestri, become the principal focus of a sketch. This and other tunnels were also described in detail in guidebooks that people like Fanshawe would have used. Impressive masonry, remarkable bridges and tunnels carved into the rock caught the eye of British travellers and the guidebooks celebrate these signs of modernity and their striking presence in a mountain landscape that was very different from England.

Elizabeth Fanshawe enjoyed depicting memorable features of a region, which, in the early nineteenth century, was still mainly rural, particularly if compared to parts of England, where factories and sites of production became features of interest among artists and tourists.Footnote 78 With the industrial development of Liguria in the late nineteenth century, the port of Genoa, with its industries and ships became a popular subject for Italian and foreign painters like Alfred Sells (1822–1908) and Pasquale Domenico Cambiaso (1811–1894), or photographers like Alfred Noack (1833–1895).Footnote 79

Roads and trains were celebrated by Italian designers and artists who relished their modernity and the way they helped to connect formerly separate states. The railway was seen by Cavour as a way of uniting Italy, and its arrival was enthusiastically received by local residents and visitors who took advantage of this faster way of travelling. The necessity for many tunnels and bridges made the construction slow and expensive and required great engineering skills. The Italian artists considered in this article, Francesco Gonin and Carlo Bossoli, had close connections with both the Piedmontese establishment and the Savoy family. Their very accurate depictions of the technical features of the Ruta Tunnel and the Turin-Genoa railway celebrated the innovation and modernity brought into Liguria by the new government.

Unlike Fanshawe, Gonin and Bossoli were professional artists who derived income from their work and had to satisfy the exigencies of the market. This didn't prevent them from combining accurate illustrations of modernity set in scenery derived from a ‘received’ picturesque tradition. Roads, bridges, tunnels and trains are surrounded by the rugged landscapes of Liguria. These scenes are often characterised by topographical composition and exaggeration of the shape of mountains and valleys. Bossoli travelled extensively around Europe and visited England and Scotland on several occasions in the 1850s and exhibited at the Royal Academy between 1855 and 1859.Footnote 80 His views show the influence of English and European movements such as the Picturesque and Romanticism, in contrast with the work of other contemporary Italian artists such as Pasquale Domenico Cambiaso or Luigi Garibbo's ‘vedutismo’.Footnote 81 Bossoli took advantage of his international connections and wanted to print his views in London, using the most modern lithographic techniques. Since the eighteenth century, going abroad to learn about new technological innovations in other countries was a common practice among Italian entrepreneurs and politicians.Footnote 82 Cavour himself enormously benefited from his extensive trips to France and England, where he developed his political ideas, as well as visiting industrial sites and cities.Footnote 83

In addition to the examination of drawings and archives, the analysis of guidebooks shows how the development of new infrastructure in Liguria was enthusiastically received by both local and English writers. Italian guidebooks such as Paroletti's Viaggio romantico-pittorico or the guide of the Turin-Genoa railway by Giuliano exalt these new features. Their baroque and rhetorical descriptions reflect the nature of these publications, used by the Sardinian Government as propaganda to celebrate the enormous economic and technological efforts for the development of the region. Guidebooks and travel accounts written by travellers, particularly English, but also Italian (for example Alessandro Manzoni) provide contrasting, vivid and perhaps more realistic descriptions. As well as pointing out the remarkable features of modern transport, they often complain about poor travelling conditions, dangerous roads and inefficient trains.

This article confirms that topographical art is a valuable source for studying the history of nineteenth-century Italian rural landscapes. It also demonstrates that topographical views and travel accounts need to be carefully and precisely contextualised. The nationality and professional status of the artist need to be considered, as they help to condition the style and the choice of the subject. In addition, topographical views need to be analysed together with other contemporary documents such as maps and archival papers. This multisource approach allows a more comprehensive and complete understanding of the landscape history of a place. Fieldwork is an important part of the methodology and its systematic use facilitated the critical approach to the sources and makes it possible to track links between the artists and the landscapes they represented in the past and present.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Leverhulme Trust, who provided funding for this research as part of the project ‘British Amateur Topographical Art and Landscape in Northwestern Italy 1835–1915’ (Project number RB1546). They would like to thank the anonymous referees for their helpful suggestions. They would also like to thank Dr Sergio Pedemonte, the staff of the Collezione Cartografica e Topografica, Comune di Genova and of the Archivio di Stato di Torino.