Introduction

In the forty years since David Jones’s groundbreaking study of the Victorian poacher, understanding of this archetypal rural crime has advanced considerably.Footnote 1 As well as knowing about the poacher’s various motivations and methods, we know that for many who never poached themselves, the act barely registered as criminal. With the game laws widely viewed as an epitome of class legislation and judicial bias, even the most industrial settings harboured sympathies for the poacher and the ‘rights and freedoms’ he embodied.Footnote 2 Moving from moral economy to moral ecology, and revisiting the relationship between poaching and theories of social crime, more environmentally focused scholarship has placed it within a broader ‘culture of dissent’, an ongoing act of resistance to perceived encroachments on traditionally enjoyed ‘life-space’.Footnote 3

Other work has shown how poaching often turned on a commercially driven urban-rural axis. Rather than being a demotic presence in the unofficial hunting field, a determined social rebel or just a hungry labourer, the poachers found here were part of a dangerous underworld of criminal gangs.Footnote 4 This further increased the attendant risk of physical conflict and the ‘rough melodramas’ of the poaching affray were a major source of interpersonal violence deep into the century.Footnote 5 More expansive occupational and spatial geographies have also been mapped: poaching was as much an activity of Midland and northern counties as it was of southern, and the factory hand or collier was as likely to go poaching as anyone from the rural economy.Footnote 6 Granted the preponderant maleness of poaching, recent research by Harvey Osborne has nevertheless shown the range and extent of female involvement.Footnote 7 Victorian women, it appears, were fully active participants in the unlawful pursuit of game.

But if it was in the nineteenth century that the ‘traditional’ (male) figure of the poacher more clearly emerged, it was in the opening years of the twentieth that the poacher, or at least the idea of him, acquired a distinctive national presence.Footnote 8 In a further shifting of perspective, the present article moves poaching out of the Victorian age and into the Edwardian, the time when the preservation and shooting of game reached their historic peaks and when debates about the land became ‘debates about the nation and the character of its people’.Footnote 9 By focusing on how the poacher was represented to an overwhelmingly urban population, what might be termed the poacher’s ‘cultural moment’ is contextualised and explored. Highlighting ruralism’s relationship to the modern, new modes of representation and reception brought the marginal world of the poacher ever more into view.

Although from at least the time of Richard Jefferies poaching had been framed in more ruralised terms, a trend that continued in the wake of his death in 1887, it was not until the Edwardian period that the culture of poaching became poaching as culture.Footnote 10 Within a generally more ordered and law-abiding society, due in part to generally improving living standards and the expanding ‘policeman state’, the quintessentially rural figure of the poacher was channelled with increasing confidence into a widening range of media forms.Footnote 11 Given the continuing advances in communications technology, especially as applied to visual culture, the ‘throw’ of poacher representations was significantly extended.Footnote 12

While arguments for an intrinsic connection between love of the countryside and ‘Englishness’ have not gone unchallenged, strongly informing this discourse of the land was a burgeoning sense of the rural, a sense that Paul Readman has argued was ‘fully assimilated into the cultural vernacular of the times’.Footnote 13 From the readers of countless books and articles, to folk song collectors, cyclists and ramblers, both imagined and actual journeys into the countryside had much to recommend them. If a growing appreciation of village life fed a lively interest in its assumed characteristics and folkways, the place in Cecil Sharp’s Edwardian imaginary that ‘made its own boots … and chanted its own tunes’ also poached its own game.Footnote 14 If the town-based variety in league with ‘some Fagin of a game dealer’ was largely beyond the pale, just as there were ‘variants of ruralism’ there were numerous poacher types from which to choose and writers as different as J. L. and Barbara Hammond and Rudyard Kipling had models to serve their particular needs.Footnote 15

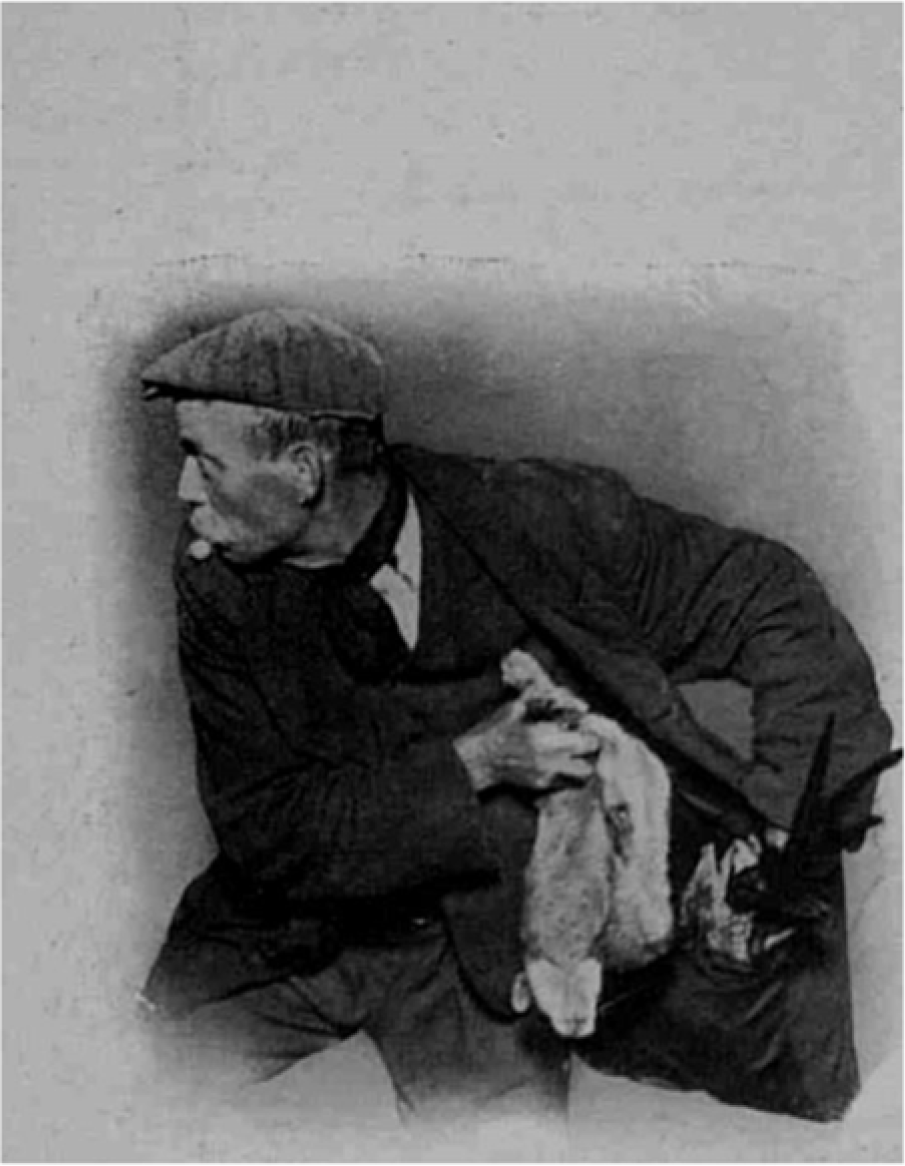

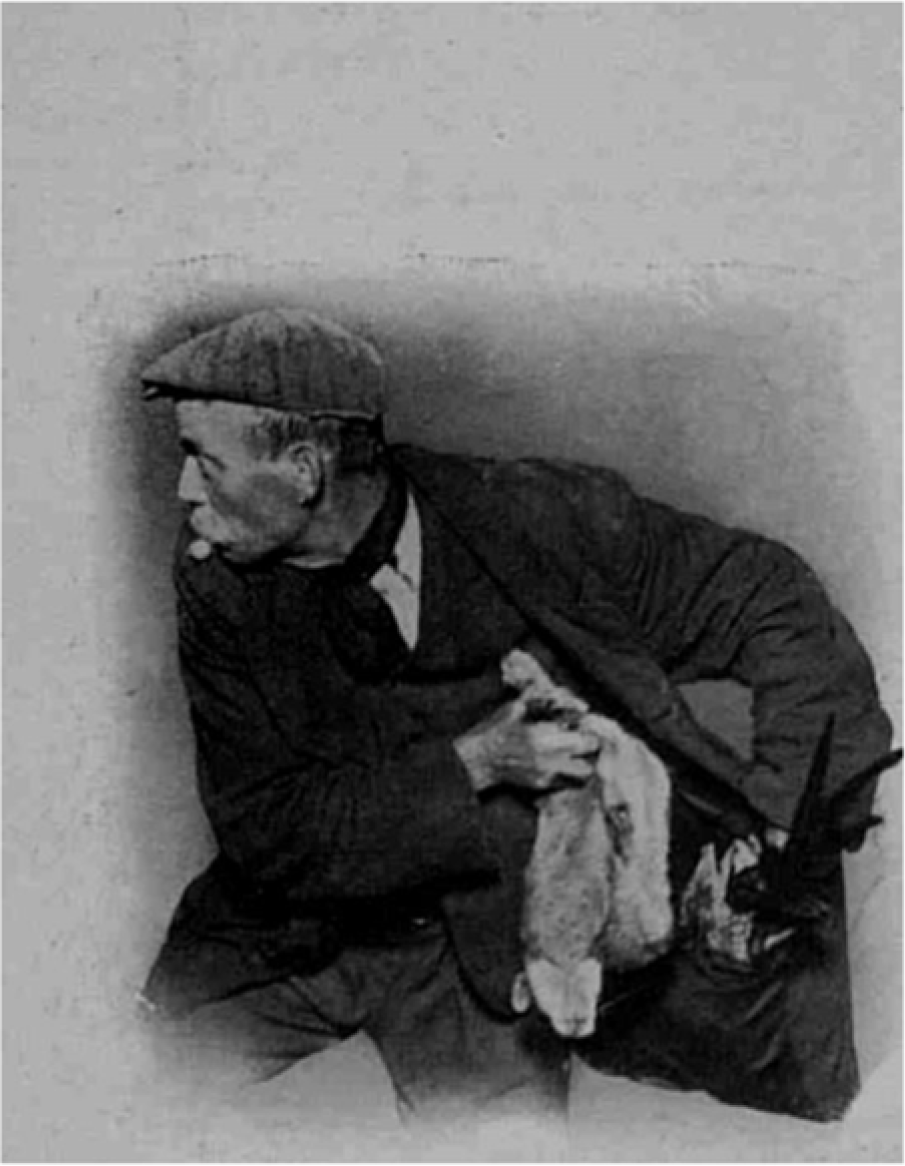

My focus here is on the poacher of ground and winged game. Although in some parts of the country the illegal taking of salmon was highly significant, in the public mind it was rabbits and pheasants that filled the poacher’s pocket (Figure 1).Footnote 16 Mindful of the point that there is ‘reality as well as representation’, the opening section gives a brief overview of poaching in Edwardian England.Footnote 17 Though officially recorded levels were falling, the courts still heard a steady stream of poaching cases and up until the First World War it was the principal form of crime in many rural areas.Footnote 18

Figure 1. From a feature on how the poacher disposes of game in the Illustrated Sporting & Dramatic News, 28th February 1914. The typical representational poacher was middle-aged or above. In practice, he was often younger.

The second section places the poacher within the symbolically loaded issue of the land. Seen to ‘intersect modern issues at every point’, the Land Question had a central place in contemporary political debate.Footnote 19 Contained within popular notions of dispossession and loss through enclosure, we have the ‘Hammonds’ poacher’. Both as powerful social memory, and continuing process, enclosure cast ‘a long shadow’ over Edwardian society.Footnote 20 Moreover, if the land had been ‘filched’ from the people, then so too had the game that roamed upon it. For those on the radical land reform platform, poachers past and present could be usefully employed as historic upholders of customary right and active agents in the current struggle against monopoly.

Although poachers of a similar stripe are observable in the nineteenth century, and stories and ballads of poaching rebels and outlaws date from much earlier, a convergence of such representations now occurred.Footnote 21 For example, in Richard Garnett’s Shakespeare: Pedagogue and Poacher (1904), the well-worn story of Shakespeare’s youthful poaching on Sir Thomas Lucy’s estate at Charlecote was brought dramatically up to date. Here, England’s greatest writer effectively puts the Edwardian landowner in the dock as he pointedly asks of Lucy ‘How many commons have you not devoured? What paths not barred?’ And ‘all’, he concludes, ‘for your game’s sake’.Footnote 22

The third section deals with ‘Kipling’s poacher’. In this conception the poacher was a true son-of-the-soil – an authentic (and authenticating) part of the timeless rural landscape. But if the idea of the Edwardian countryside offered a bulwark against the forces of rapid change, it also appeared vulnerable. Within this particular realm of concern books like The Autobiography of a Poacher (1901) also had a role to play. Included in Regenia Gagnier’s study of self-representation, it is placed firmly in the ‘conservatively reminiscent’ genre of the working-class picaresque that dwells on the ‘image of a past that seemed timeless’.Footnote 23 With the ‘immortal Shakespeare’ who ‘was in youth a deer-stealer’ added to his own idealised sense of ‘Old England’, the Devonshire poacher-turned-gamekeeper, John ‘Lordy’ Holcombe, was at pains to emphasise that ‘on public and private grounds I am a Conservative’.Footnote 24

Commonly associated with nature, and nights spent in the woods and fields, the liminality of poaching also figured in what Michael Saler discerns as a counter-modernity culture of ‘re-enchantment’.Footnote 25 Beyond the law, but part of the lore of the land, poaching was never the ideological preserve of radicals. Finally, in the world of ‘Kipling’s poacher’, unusual reserves of wit and native cunning were likewise apparent. And while not suggesting that radicals necessarily lacked for humour, the poacher as a source for authority-mocking amusement is also considered here.

‘Not now worth the candle’: Edwardian poaching

In the autumn of 1906, Country Life confidently declared that over the last twenty-five years the ‘poaching mania’ had been ‘considerably allayed’ and that ‘one may accept it as a truth that the game is not now worth the candle’.Footnote 26 While recognising the statistical gap between recorded and actual levels of crime, in terms of the summary hearings that covered most poaching cases the decline observable from the 1880s continued into the following century. Between 1900 and 1904, the combined annual average was 7,939 prosecutions; for 1905–09 it was 6,338; and for 1910–14 it was 4,675. Within these averages there were of course fluctuations – in 1903 the total recorded was 8,106 compared to 7,711 for the previous year – but taken overall the decline was unmistakable.Footnote 27

Yet if the general trend was downwards, in areas where game was heavily preserved poaching remained common. Although causes need not concern us, the significant fall witnessed in northern and Midland counties towards the end of Victoria’s reign was not always mirrored in those below the Wash.Footnote 28 This is not to say that poaching was strictly confined to the more rural parts of southern England. Towns and cities across the country still produced their share of poachers, as did many pit villages. However, if ruralism acquired a markedly southern bias, the evidence suggests that it was the ‘South-country’ poachers so admired by Kipling that provided much of the material reality.Footnote 29

Taking a lead from George Ewart Evans’s oral histories of Suffolk, it appears that as ‘sport or devilment’, or as a valuable source of extra food and income, poaching remained an integral part of village life.Footnote 30 According to the secretary of the East Anglian Game Protection Society, Charles Row, certain parishes in Norfolk were ‘infested with poachers who practically live out of the proceeds’, and in Edwardian Sussex we learn from Gilbert Sargent (born 1889) that ‘everybody used to poach in those days’.Footnote 31 At Headington Quarry in Oxfordshire, the poaching of rabbits was so prevalent that the inhabitants would place advance orders.Footnote 32 ‘Poaching To-Day’ was the instructive title of another piece from Country Life in 1912. Beginning with a recent case involving a gamekeeper being shot at by two miners in south Wales, it quickly settled on Gloucestershire and the operations of the village-based poachers who ‘by no means have died out’.Footnote 33

A good insight into Edwardian poaching comes from the Deputy Surveyor of the New Forest, Gerald Lascelles. An area rich in wild pheasants, woodcock and rabbits, at £20 for an annual licence, according to the aristocratic Lascelles it was a ‘poor sportsman’s paradise’.Footnote 34 As in other less iconic spaces (the forest had recently become subject to an extensive ruralist makeover) it was the humble rabbit that formed the principal quarry for poachers.Footnote 35 Not only were they easier to target than winged game, in the absence of a close season those not bound for the pot could be disposed of with relatively small risk. Also, the animal’s habits were viewed as inimical to the interests of game birds and it was not unknown for keepers in the forest, and elsewhere, to turn a blind eye to minor infractions in exchange for information on more serious offending.Footnote 36 The activities of various game preservation societies indicate that the prosecution of ‘trivial’ cases involving rabbits ranked much lower than tackling the extensive black market in stolen partridge and pheasant eggs.Footnote 37 Indeed, one contemporary explanation for poaching’s apparent decline was that so much winged game was now being produced, and subsequently made available on the open market, any other trade in it was pointless.Footnote 38

From the folder of cuttings that Lascelles kept on poaching in the New Forest it is clear that the taking of rabbits comprised the bulk of local activity. It also appears that when charges were successfully brought, the courts not infrequently imposed lower fines than expected.Footnote 39 In a case from 1906 that especially bothered Lascelles, a man caught poaching rabbits in the early hours of a Sunday morning (and so during the legally more serious hours of night-time) was fined only five shillings plus three in costs.Footnote 40 Contrary to those who insisted on the iron rule of ‘justices justice’, those with an interest in preserving invariably took the opposite view. ‘Unfortunately, the law is powerless to deal with poachers as a class’, complained the Field in 1902, and it was ‘useless in this democratic century to ask for fresh powers.’Footnote 41

The incident that infuriated Lascelles also highlights the continuing potential for violence. While on this occasion the captured poacher’s accomplice escaped following a short struggle, conflict might be more serious. In a 1901 letter to the Office of Woods, Lascelles described fighting of a ‘very hot nature’ between four poachers and those sent to apprehend them. Before eventually gaining the upper hand, Lascelles’s men were ‘much injured’ by ‘volleys’ of stones and heavy sticks.Footnote 42 Although the fights and gunplay of A Desperate Poaching Affray (1903) were greatly exaggerated for the screen, hard-fought encounters were still being noted in the regional press and in ‘true crime’ publications like the Illustrated Police News (Figures 2a and 2b).Footnote 43 Equally, however, there was undeniably less ‘blood on the game’ than when Charles Kingsley wrote of the ‘Poacher’s Widow’ in the late 1840s.Footnote 44 Between 1901 and 1914 the annual number of indictable game law offences (including assaults on keepers) averaged twenty-eight.Footnote 45 During the 1840s, the decade that saw the beginning of John Bright’s long struggle against the game laws, the equivalent figure was 131.Footnote 46 When a magazine informed readers in 1912 of the knocks and falls sustained in fights with poachers, it was in a feature on Cecil Hepworth’s film studio at Walton on Thames. Fortunately for the actors involved, there was a ready supply of ‘strapping plaster and arnica’.Footnote 47

Figure 2a. A Desperate Poaching Affray (1903). Poachers caught in the act.

Figure 2b. A Desperate Poaching Affray. Coming to blows with the police. Before capture, the poachers shoot two keepers point blank. The film was a huge hit.

That the poacher remained a living force, while simultaneously appearing less threatening, was vital to his cultural usability. Analogous in some ways to the highwayman or the smuggler, unlike these other traditionally romanticised criminal archetypes, the poacher remained an everyday part of life. Coincident with the growing Edwardian attachment to the countryside, the very livingness of the poacher added greatly to his signifying weight. Within the period’s broader shift towards valourising the lowly figure of ‘Hodge’ charted by Alun Howkins, the fact of the poacher’s continued existence both stimulated and sustained his growing, and growingly varied, representational presence.Footnote 48 Given a leading role in this culturally constructed ‘other’ countryside, it is to these ‘other’ poachers of Edwardian England that we now turn.Footnote 49

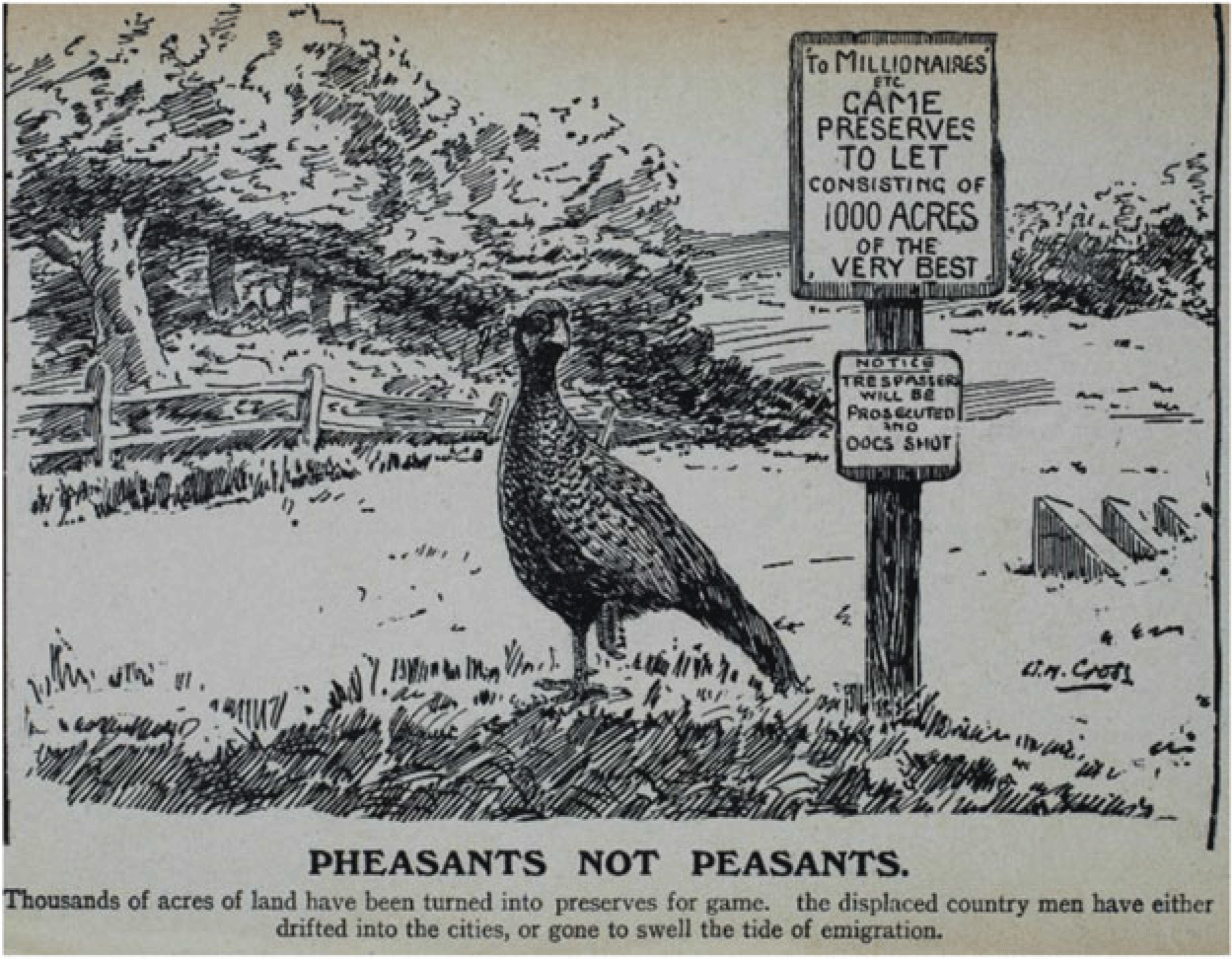

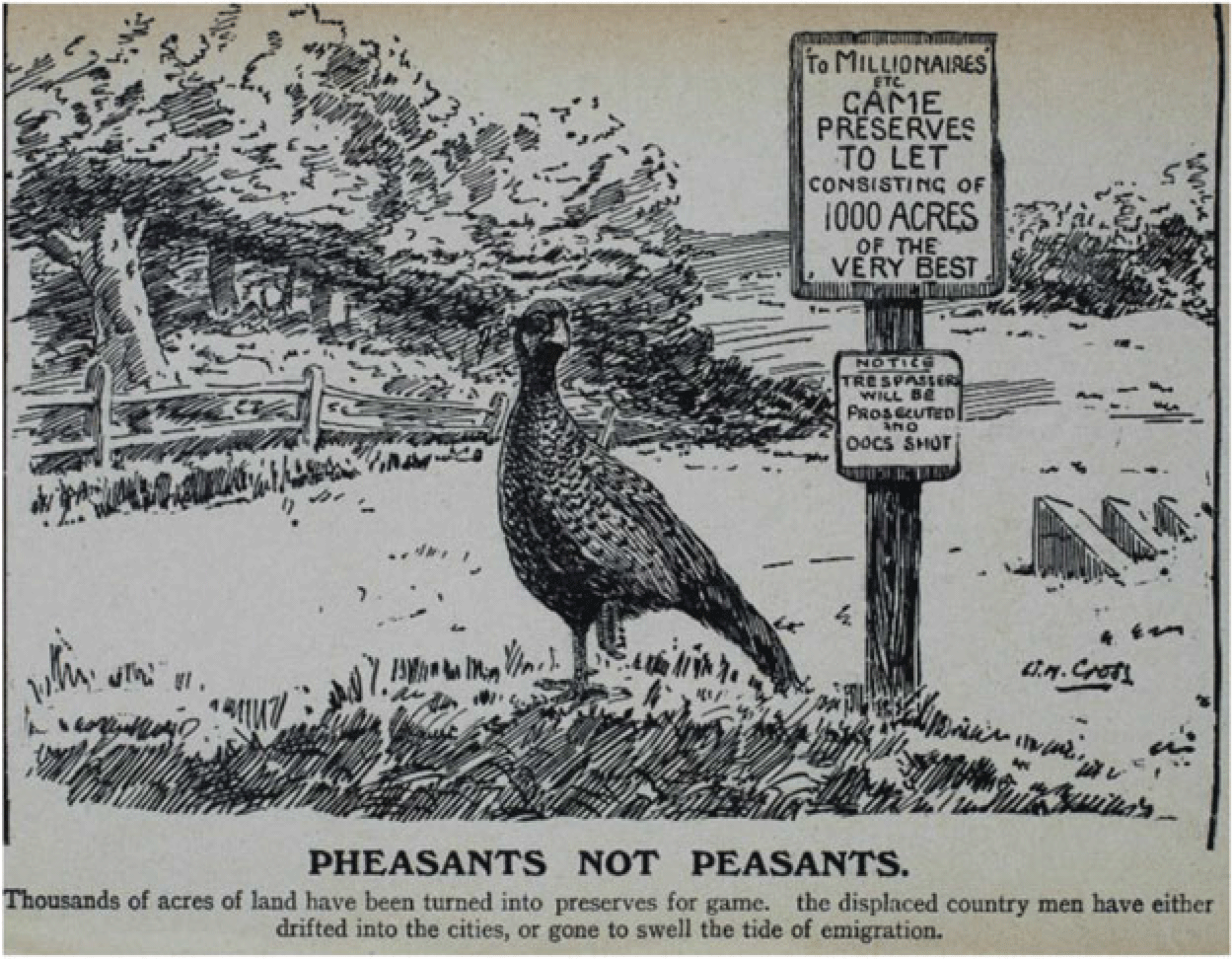

‘The best and bravest blood’: the Hammonds’ poacher

The preservation and shooting of game, and the various controversies attaching to the Land Question, both reached their climax in the Edwardian years. While agriculture was recovering from its nadir of the mid-1890s, the humiliations of the war in South Africa had deepened concerns over national efficiency and food supply. As more land was made subordinate to the needs of the shoot, this ‘fetish of the privileged few’ was subject to intense critical scrutiny.Footnote 50 At a time when seasoned politicians like the Lib-Lab MP, John Burns, was announcing his stern commitment to ‘an England that would care more about the peasant than pheasant’, the Conservative journalist and sportsman, T. E. Kebbel, could not unreasonably bemoan the subject’s use as a ‘stalking horse’ from behind which estate owners could be rhetorically shot at.Footnote 51 With more game requiring ‘armies’ of keepers to manage it, debates about land ownership and usage could slip easily into disputes about the evils of ‘landlordism’ and the rights and wrongs of the sporting estate.Footnote 52 Inevitably this raised the issue of poaching itself (Figure 3).

Like many of his kind, Kebbel was dismayed by what he saw as misguided public sympathy for the poacher, a concern apparently justified by the experience of the Conservative MP, George Verrall. Commenting on his defeat in the marginal constituency of Newmarket in the December 1910 election – a contest largely fought on the issue of ‘Peers versus People’ – Verrall claimed that his role as a magistrate had cost him dearly after it was ‘spread about the division that I had given a poacher a month’.Footnote 53 Although in this instance the man convicted was pardoned on appeal, in this politically charged atmosphere it is a likely paradox that negative perceptions of the ‘feudal’ game laws were heightened at a time when enforcement was becoming less strict.

The loss of Charles Trevelyan’s 1908 Bill granting limited rights of way on moorland game preserves, alongside the routine struggles of open-air recreationalists for improved access to the countryside, further enforced the view of a selfish elite enjoying its leisure at the expense of the many.Footnote 54 The Sheffield Clarion Ramblers who engaged in a regular battle of wits with gamekeepers in the Peak District might only have been carrying compasses and flasks in their ‘poacher’s pockets’, but the nomenclature was freighted with meaning.Footnote 55

By refusing to accept exclusion from the doubly enclosed space of the game preserve, the poacher displayed just the kind of dissenting spirit that advocates of greater access wished to endorse. Stressing the cultural and political significance of the countryside in Labour’s early development, Clare Griffiths has noted how support for the poacher and trespasser were commonly articulated themes.Footnote 56 Having condemned in one of his Red Flag Rhymes (1900) the ‘greed of the covetous lord/who fenced out the weak and the poor’, the lifelong poacher and ILP activist, Jim Connell, boasted that ‘later through covert and pheasant stocked glade … I broke ev’ry law the land robbers made’.Footnote 57

Figure 3. From an illustrated version of Lloyd George’s Land Campaign speech at Swindon on 22nd October 1913.

Author of an 1898 pamphlet for the Humanitarian League on the manifold cruelties of the game laws, in 1901 the Lewisham-based Connell penned his Confessions of a Poacher.Footnote 58 Based upon regular forays into Surrey and Kent, and invitingly advertised as the ‘actual experiences of a living poacher’, the book had previously been serialised in Tit-Bits.Footnote 59 Presenting the poacher as a vital force against the physically and morally degenerate ‘crutch and toothpick brigade’, special praise was reserved for Connell’s fellow ‘pilgrim of the night’, Greenman, ‘a hater of landlords and aristocrats of all sorts … A born rebel and law-breaker, he was yet the jolliest and most generous of companions.’Footnote 60 Connell closed his account by claiming that if ‘troublous times’ arose, among those ‘likely to make their presence felt’ would be the nation’s poachers.Footnote 61

This, then, was the ‘Hammonds’ poacher’ – a figure to be mobilised in the cause of popular reform and defence of the wider community. As the rural investigator and horticulturalist, Christopher Holdenby, reported of the West Country labourers he knew, to poach was a form of ‘just reprisal’ and amounted to ‘carrying the war right into the enemy’s country’.Footnote 62 In expressing views later found in James Hawker’s celebrated memoir of a radically inclined Victorian poacher (published in 1961, Hawker’s account was written in 1904–05), Holdenby’s men sounded equally like the scourge of Edwardian landlords, David Lloyd George.Footnote 63

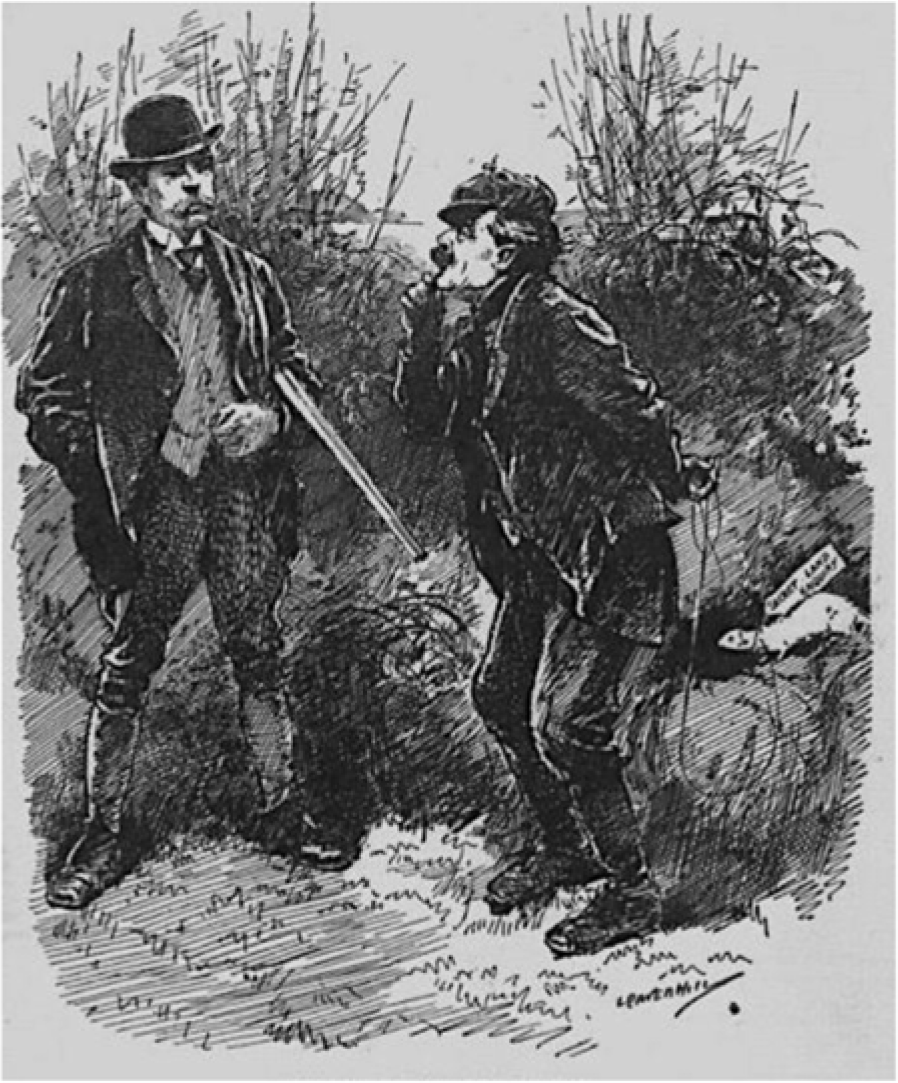

Raised when poaching was a common activity in rural Wales, and where the apparently English nature of the game laws added a patriotic twist, the finest platform speaker of the day was fully aware of the issue’s populist reach and appeal and readily deployed it in his party’s mounting ‘Kulturkampf ’ against landlordism.Footnote 64 Just as Lloyd George claimed for himself, the poacher stood for selfish interests challenged and entrenched positions undermined. Responding in December 1909 to the Lords’ rejection of his land-taxing budget he deemed them of ‘no more use than the broken bottles stuck on a park wall to keep off [radical] poachers’.Footnote 65 In a habit much enjoyed by Punch, the ‘poacher’s lawyer’ and self-styled ‘cottage bred man’, loved to brag of his merits in the field and in the same election that cost Verrall his seat publicly recalled his own exploits as a skilled poacher of rabbits (Figure 4).Footnote 66

Figure 4. Punch, 4th November 1912. The cartoon relates to a recent debate in the Commons on what the Conservative opposition called the ‘secret’ land enquiry.

Defending controversial claims on the destructive habits of pheasants made at Bedford in October 1913, the chancellor used his follow-up speech in the recently launched Land Campaign to assure critics that he knew ‘more about game’ than any keeper would wish him to.Footnote 67 At Holloway Empire the following month, the gamekeeper was cast as a ‘priest’ to the ‘squire god’ with the game laws becoming the ‘ark of the covenant’.Footnote 68 Political knockabout it may have been, but set within government proposals for sweeping rural reform the poacher’s progressive associations were further emphasised. When the National Review assigned Lloyd George ‘no higher place in the hierarchy of sport than that of an ex-poacher’, it rather missed the point.Footnote 69

Complementing these colourful assaults on the sporting landlord was the Hammonds’ sobering 1911 account of the social impacts of enclosure.Footnote 70 Steeped in the politics of an emerging social democracy, and a significant influence on the Lloyd George-inspired Land Enquiry report, in what the Economic Journal described as this ‘brilliantly written social tragedy’, the poacher was unquestionably made a heroic figure.Footnote 71 One of the ‘favourite Don Quixotes of the village’, the ‘best and bravest blood’ had ranged against him ‘not merely a bench of game preservers, but a ring of squires, a sort of Holy Alliance for the punishment of social rebels’. Banishment to Botany Bay was the only reward for these worthy men of ‘spirit and enterprise’ and ‘natural leaders of their fellows’.Footnote 72

Fusing the iniquities of enclosure with those of the game laws, the Hammonds did in finely wrought historical prose what John Clare and William Cobbett, whose own work was now subject to revival, had previously done in poetry and polemic.Footnote 73 Yet whatever the book’s literary merits, not everyone was convinced of its argument. For the distinguished agricultural historian and land agent to the Duke of Bedford, Rowland Prothero, The Village Labourer was ‘not a history but a political pamphlet’.Footnote 74 Not entirely without justification, such comments against the Hammonds might also be directed at their friend, G. M. Trevelyan’s 1913 biography of John Bright.

In writing on a giant of nineteenth-century radicalism, Trevelyan’s primary aim was to show that a quarter of a century after Bright’s death, the causes he espoused, including reform of the game laws, retained their currency. Though, like his brother Charles a keen sportsman, as Trevelyan’s own biographer records, Trevelyan ‘resented the closure of moors and forests for the exclusive use of Edwardian shooting parties’.Footnote 75 As with the Hammonds’ evocation of an earlier period, where the woods were ‘packed with tame and docile birds’ watched over by ‘armies of gamekeepers’, Trevelyan’s descriptions of the mid-Victorian countryside were meant to strike a chord with anyone concerned at the alleged excesses of the present.Footnote 76 ‘To poach’, conceded Trevelyan, ‘was no doubt wrong’, but ‘to fill a thickly populated modern country with game running wild among a starving people’ was clearly worse. Small wonder, he continued, that ‘any lad of spirit’ might think poaching ‘a virtue’.Footnote 77

Though fewer people in England were now likely to be starving, films like Walturdaw’s The Poacher (1909) suggest how the act was still relatable to economic distress. ‘Driven by want’, an out of work labourer poaches to feed his dependants and gets falsely accused of shooting a policeman.Footnote 78 Luckily for the poacher, a witness eventually comes forward. Exemplifying the Edwardian commitment to detailed enquiries into poverty, Seebohm Rowntree’s The Labourer and the Land (with a preface by Lloyd George) gave detailed breakdowns of the meagre weekly diets of rural families.Footnote 79 A conversation between one of Rowntree’s investigators and a village schoolmaster produced the following exchange:

[Investigator] ‘The people generally strike one as very respectable.’ [Schoolmaster] ‘They are a law-abiding set – except perhaps in one respect’ [Investigator] ‘Poaching?’ The schoolmaster laughed. ‘Yes, he said, and somehow they can’t regard that as an actual crime. When I remember how hardly and monotonously they live form day to day, I can’t regard it myself, as a very desperate crime. As for theft in the ordinary sense, it never occurs at all.’Footnote 80

While the Hammonds did not invent the idea of the poaching Hampden, as with Keighley Snowden and George Bartram in their popular historical novels from 1914, they undoubtedly brought it to a wider audience. In Snowden’s King Jack, for instance, Jack Sinclair is first encountered in Hampdenesque mode defending a village’s right to a communal water supply. Having established the poacher in such terms, the story unfolds as a succession of picaresque adventures with ‘King’ Jack always ahead of the authorities.

Of much greater interest is Sinclair’s relationship with the local schoolmaster whom he visits when in a more introspective mood. The unusual mental capacities attributed to the poacher, usually manifested in a well-developed native cunning or deep understanding of the natural world, could also produce a more political turn of mind. Through his public role in the community, and private friendship with a Cambridge man, such qualities are made evident in Sinclair. Explaining the motivations for his own work in the knowledge that the poacher will understand, the teacher reveals his dream of nurturing ‘another Hampden’ and of how ‘I think that a man fighting as you are may need to look sometimes at children’s faces … I teach them to be fair and kind, so that they will hate unfairness and tyranny.’Footnote 81

The sense of a ‘tyrannised’ countryside, a descriptor much favoured by Edwardian critics of the game laws, was even clearer in George Bartram’s The Last English. Set in the fictitious Midland village of Tiptry in 1840, the story centres on the struggle between the vindictive squire Jarvy and ‘Black’ Steve – the latter returned from a twenty-year sentence of transportation for poaching pheasants. Determined to punish the villagers for taking back their local hero (he even has a song written after him) the squire resolves to enclose the common. Aided by two Chartist supporting students, it is the poacher who leads the resistance. Victory over the squire achieved, ‘Black’ Steve and a group of friends decide on a new life overseas. With the Dominions now a prime destination for migrating rural labourers, the point would not have been lost on the book’s readers. ‘With a fair chance, in a new country’, observes one of the poacher’s erstwhile allies, ‘such people can never know failure. The loss is here.’Footnote 82 The Hammonds could not have put it better.

The ‘old unaltered blood’: Kipling’s poacher

The best place to start with the idea of ‘Kipling’s poacher’ is with Kipling himself, a writer whose engagement with Edwardian England was ‘at once unique and representative’.Footnote 83 Upon moving to the Sussex Weald in 1902, just the type of local that the Indian-born Kipling was hoping to find was the septuagenarian labourer, and poacher, William Isted. Fascinated by new technology, Kipling was also drawn to the poacher’s more ancient and primitive world and Isted was quickly elevated to ‘special stay and counsellor’ with the occasional job of keeping down the rabbits on his Bateman’s estate.Footnote 84

Isted was also the source for Hobden, the poaching rustic of the ‘old unaltered blood’ who featured in some of Kipling’s best-loved work of the time.Footnote 85 Using Bateman’s and its surrounding countryside for a backdrop, in Puck of Pook’s Hill (1906) and Rewards and Faeries (1910), Kipling has the fairy-guide figure of Puck take his own children – here named Dan and Una – on a series of magical journeys into the past. Eschewing conventional chronology and detail for a loamy ‘regenerative mythology’, and anticipating the kind of organicist vision of Englishness that emerged between the wars, the undying continuity of the land was central to Kipling’s enchanted moral history.Footnote 86 With the imperial mission currently on the defensive, in Kipling’s countrified vision of the homeland the past rooted the present and secured the future.

Aside from Puck and the children, the other recurring figure is Hobden. Dan and Una’s ‘particular friend’ not only shows them how to set wires and snares, but how to know and respect the world out of doors.Footnote 87 Whereas Hobden poaches in a moderate way, and is protective of dormice, Ridley the keeper is merciless to animals classed as vermin.Footnote 88 While Puck teaches the children where they have come from, the man who has ‘not forgot [his] way about the woods’ teaches them where they are.Footnote 89 Within the ruralised world of the stories, where the land’s very substance was an endlessly forming palimpsest, there could be no surer guide than one whose poaching ancestors were thirty generations in the ground.

But if ‘Kipling’s poacher’ offered an enchanted way into the national past, he could also offer comment on the present. As recent events in South Africa had apparently shown, the undemanding nature of the driven shoot had greatly reduced its martial value.Footnote 90 In stark contrast to what Kipling’s friend and adviser on rural matters, Rider Haggard, saw as the ‘country-bred intelligences’ of the sharp-shooting Boers, the British had proved worryingly deficient in marksmanship and fieldcraft.Footnote 91 With existing fears at the degenerative effects of mass urbanisation also seemingly confirmed, ‘the return to nature’, notes Peter Broks, became of nothing less than ‘imperial importance’.Footnote 92

These sentiments are clearly discernible in the final story from Puck. Here we find Hodben’s quiet craft set against ‘new men’ like Mr Meyer. Presenting a cruel caricature of the Edwardian plutocrat’s obsession with slaughtering vast amounts of artificially reared game, the over-excitable Meyer is prone to firing at beaters instead.Footnote 93 Reassuringly, however, before Meyer can set about his noisily destructive pastime, Hodben has been out to cache his artfully poached game in the faggots he will take to his woodland home.Footnote 94 The man the keepers would love to see ‘clapped in Lewes jail all the year round’ will have to be caught first.Footnote 95

Within this context of military/imperial concern, it is again possible to see the attraction of the poacher idea. Not only did the poacher form an integral part of the national fabric, he also appeared well equipped to preserve it. This in turn fuelled Kipling’s enthusiastic support for the Scout Movement, an organisation formed in 1907–08 by one of the few bright spots of the Boer War, Robert Baden-Powell. For men such as these, it was the skills and attributes required of the successful poacher, rather than the ‘gunners of the exterminating class’, that would ultimately be more useful in combat situations.Footnote 96 ‘The Scout has much to learn from poachers and their ways’, advised The Woodcraft Supplementary Reader for Schools (1911), ‘and many of his dodges … might stand scouts in good stead’.Footnote 97

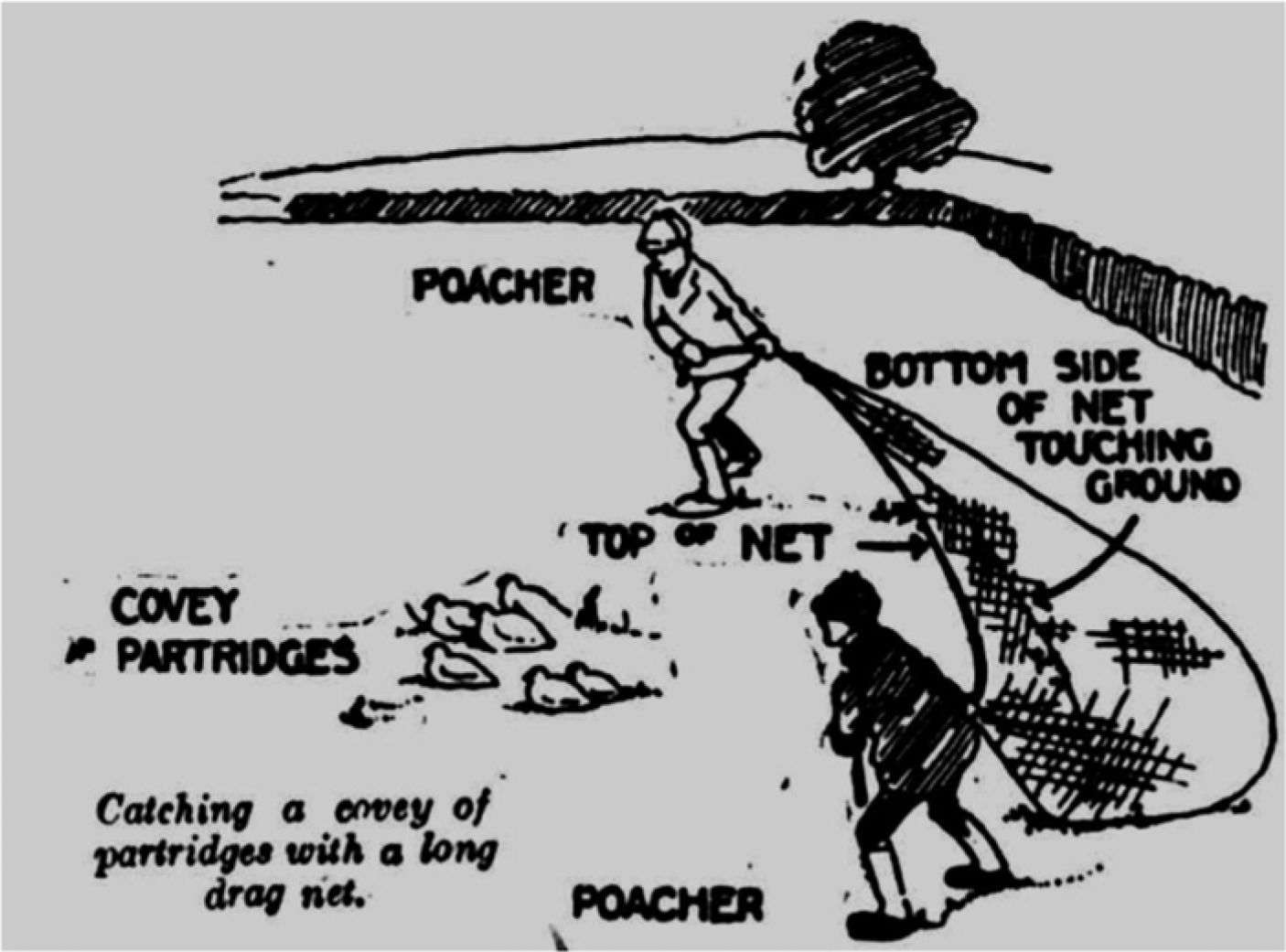

Suggesting the kind of robust outdoor activity promoted by scouting was a 1907 feature in C. B. Fry’s Magazine. Accompanied with photographs of men working with snares and nets, the article drew on a conversation with a lifelong Hampshire poacher over the course of a November evening. In a cottage very much resembling Hobden’s, the poacher and his interlocutor sit snugly over a fire as this hardy ‘son of the sod’ presents poaching as a ‘fine hobby – healthy and exciting’.Footnote 98 In the age of the ‘ostentatious parvenu … squatting on unfamiliar soil’, the local man who netted or wired or used his skill with a cleverly adapted gun had an obvious appeal.Footnote 99 Not only did the poacher’s craft-based (and crafty) hobbyism deny the ‘effective industrialisation of rural sport’, it restated a purer way of country living (Figure 5).Footnote 100

Figure 5. Pearson’s Weekly, 12th August 1909. From a feature titled ‘The Compleat Poacher’, the archaic spelling suggested Isaac Walton’s sporting classic, The Compleat Angler.

In placing Hobden in the literally enchanted world of the Puck stories, Kipling was to some extent refashioning an existing idea. From predicting the weather by the shape of the moon, to being ‘fetched-off’ by phantom coaches, tales of the poacher’s nights in the wild, ‘when the heads o’ the high elms do sway and his limbs do creak an’ crack’, were a fertile source of ‘re-enchantment’.Footnote 101 Mostly confined to our ‘villa streets’, proposed a 1901 piece in the Argosy, ‘at the sight of a quiet wood on a dark, still night, the poacher stirs in the blood of many of us’.Footnote 102 However, if this particular idea of the poacher was a beguiling counter to the ‘instrumental rationality’ that attended the modern industrial state, a degree of ambiguity was often in play.Footnote 103 Proscribed by statutes separate from the main body of laws protecting game, by venturing out at night the poacher was acting in an altogether more criminal way.Footnote 104

This ambiguity was nicely expressed in a pair of articles on poaching in Arden by the mysteriously named ‘X’. Though in its wooded associations the scene is preloaded with enchantment, on first sight the ‘loafing’ poachers are not at all promising as they gather in desultory fashion in the Black Lane. Out in the dark of Spinney Close, however, a dramatic transformation occurs. In close harmony with their dogs, the ‘crouching forms’ of the poachers become ‘a special creation of mysterious Nature.’ Netting rabbits with wordless expertise ‘Mercury runs in their veins’. Having enjoyed a bountiful night, this ‘unearthly’ group silently retraces its steps.Footnote 105

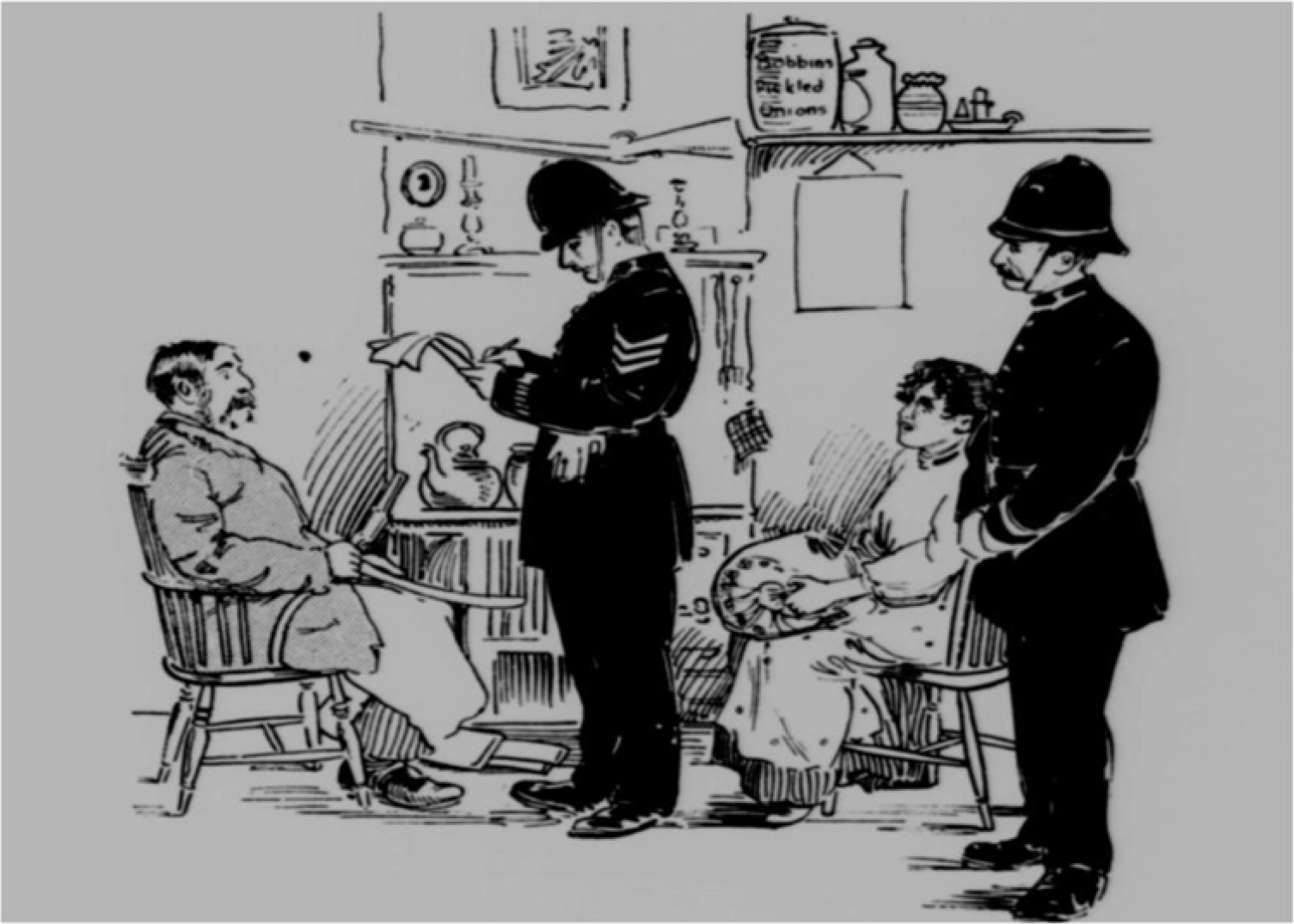

In a society that put humour on a par with the sporting instinct, the poacher could also enchant through his cunning displays of wit and guile. In a way that has been observed for other disreputable comic types, it was possible to know that the poacher was ‘wrong’ while simultaneously finding pleasure in his actions.Footnote 106 Plays like Gentlemen of the Road, a ‘droll episode of country life’ that has three poachers con a ‘parvenu’ motorist out of his car and then use it as a getaway vehicle; Gertrude Robins’s one-act comedy Pot Luck, where a poacher and his wife outwit the local constabulary; and Eden Phillpotts’s 1908 novel The Mother, with its ‘grey-whiskered and humorous’ poacher Moleskin, all point to the enjoyment of seeing authority mocked by the poacher’s carnivalesque ways (Figures 6 and 7).Footnote 107 At the conclusion of A Day with Poachers (1912) – a curious blend of chase film, comedy and ‘how to’ manual – viewers are openly invited to laugh with the men who have expertly bagged their game while evading the hapless keepers.Footnote 108

Figure 6. ‘Scenes from Pot Luck’, English Illustrated Magazine, February 1911. Unable to find the pheasant the poacher has placed in his wife’s cooking pot, the police abandon their search.

Though Bert Gilbert’s musical turn as a poacher at the London Coliseum (complete with mechanical dog) is beyond recovery, the adventures of W. W. Jacobs’s unbeatably cunning Essex poacher, Bob Pretty, which first appeared in the Strand Magazine, take us further into the realm of performer/audience ‘knowingness’ first explored by Peter Bailey.Footnote 109 As Jacobs’s aged narrator acknowledges from his bench in the Cauliflower pub, when it came to Bob Pretty ‘Deep is no word for ’im. There’s no way of being up to ’im …‘Nobody ever see ’im do any work … but the smell from his place at dinner-time was always nice’.Footnote 110

Combining Jacobs’s own social conservatism with misgivings at the ‘new men’, one story begins with the death of old Squire Brown and subsequent arrival of a London-based sporting landlord called Rocket.Footnote 111 Seeking to produce as many birds as possible, the newcomer is vexed at how many go missing. The keepers know Pretty to be the principal cause, but are never able to prove it. Consequently, a new head keeper called Cutts is engaged, a man of such reputation that ‘pheasants could walk into people’s cottages and not be touched’.Footnote 112 Needless to say, the poacher is much too good for Cutts and with all the attention focused on Pretty some other poachers enter the coverts and help themselves to the game.

By employing his own version of what Kipling termed ‘stalkiness’, Pretty not only serves his own interests but also, one feels, the idea of a ‘proper’ rural order.Footnote 113 On paper ‘Kipling’s poacher’ was undeniably breaking the law, but in the face of men like Meyer and Rocket he also represented a backhanded integrity – an organically approved guarantor of the land and, if need be, a defender of it. Providing lyrical testament to the belief that from Crécy and Poitiers to Waterloo, the ‘rough sturdy men’ of the ‘old poaching spirit’ had helped win the day, we have Kipling’s ‘Norman and Saxon’.Footnote 114 Written for inclusion in the Oxford-based C. R. L. Fletcher’s history of England (1911), the poem celebrates the ‘hard-bitten South country’ poacher who invariably proves ‘the best man-at-arms you can find’.Footnote 115 ‘Don’t sell my medals’ says the dying old poacher to his wife in Phillpotts’s 1912 drama The Carrier Pigeon, ‘there’s the VC and t’other’.Footnote 116

Figure 7. Frontispiece to Eden Phillpotts, The Mother (1908). Moleskin, the good-natured poacher and local sage who keeps the Three Jolly Sportsmen well stocked with game and rustic wisdom.

Conclusion

For David Jones the Victorian poacher was ‘a more complex character than might appear at first sight’.Footnote 117 What was true of the nineteenth century was even more so of the next. While in numerical terms the poacher was a diminishing presence, at the level of representation it was the reverse. Although underlying continuities must not be lost sight of, it was in the opening two decades of the twentieth century that the idea of the poacher as an unusually appealing national character extended and deepened its place in the culture. If Englishness was now synonymous with the countryside, then so too was the poacher

At the heart of this process was a wide-ranging debate on the control and use of the land coupled with the growing employment of the countryside as a multi-use cultural space. Continued developments in mass communication, meanwhile, furthered the reach and penetration of the countryside ideal. It was a modernising world of towns and cities that peopled its woods and fields with poachers. But if ruralism helped secure the representational place of the poacher, the poacher was an important thickening agent for ruralism.Footnote 118 Far from ‘English urbanites’ half-heartedly sustaining ‘a folk myth of the rural home’, deepening interest in earthily authentic figures like the poacher suggest the extent to which ruralism was rooted in early twentieth-century thought and feeling.Footnote 119

The war that brought the Edwardian era to a crashing end also killed off the Land Question as a major political issue and precipitated a marked decline in the preservation and shooting of game. Although as wartime boom turned to bust, the economic sustainability of the countryside became a serious cause for concern, its role as an ‘urban playspace’ and site for physical and moral regeneration was firmly set.Footnote 120 The poacher, who in representational terms enjoyed a good war – trenches were defended, comrades saved, and more Victoria Crosses won – returned to his established domestic roles.Footnote 121 While the interwar years, and the Second World War itself, produced another rich crop of poacher representations, from H. E. Bates’s The Poacher, to Bill Purves in Ealing’s stirring wartime invasion drama Went the Day Well?, the essential English poacher, representing an essentially rural England, had already been made.Footnote 122

The multifaceted nature of ruralism was also exemplified in the dualisms of the Edwardian poacher. If the poacher idea drew repeatedly on the act as being one of noble resistance to social injustice, it could also be related to a truer, and innately conservative, ‘countryman’s’ instinct. Not just the Don Quixote of the Hammonds’ construction, but Sancho Panza too, the poacher was embedded in a broadly shared sense of a ruralised national past.Footnote 123 Capturing these complexities well is the memorable figure of ‘Lob’. Just as a Sussex poacher led Kipling towards the creation of Hobden, so the Wiltshire poacher, David Uzzell, was vital to the work of Edward Thomas. Of many names and times and places, Lob ‘carries in him the essential history of the land’ – he is both Jack Cade and a sporting squire’s son.Footnote 124 In the same year (1915) that Thomas wrote his great poem, Kipling announced to a cheering audience at the Mansion House that there was nothing in the idea of the poacher ‘except all England’.Footnote 125 Within the particular cultural turn delineated by this article, the Edwardian poacher represents a form of social criminal rather different from previous conceptions. Just like the pockets of his fabled coat, his meanings were many and deep.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Professor Claire Langhamer who supervised the thesis upon which much of this article draws. Thanks also to Professor Carl Griffin and the two anonymous referees for their helpful comments and suggestions.