Introduction

How did agricultural output evolve in Germany prior to the onset of rapid industrialisation and railway construction during the third quarter of the nineteenth century? Around the middle of the nineteenth century, both the share of urban in total population and GDP per capita were low in comparison with the leading economies of north-western Europe.Footnote 1 This suggests a modest level of agricultural productivity and limited scope for agricultural output growth during earlier periods in Germany. Nevertheless, two developments may have created a potential for agricultural output growth before the middle of the nineteenth century: First, beginning in the 1800s most German territories enacted agrarian reforms that established individual property rights over land and abolished feudal obligations of peasants. Liberal reformers claimed that this was the only way to allow that all benefits from improving agricultural techniques and investing in farming would accrue to the new peasant class and to large landowners. Creating incentives for adopting innovations would infallibly induce agricultural growth. Newly established property rights would also establish efficient land markets improving substantially the efficiency of factor allocation. On this background, an older scholarship has concluded that agrarian reforms and their assumed output gains formed an important precondition for industrialisation and the transition to modern economic growth later in the nineteenth century. Recent studies have explored the possibility that regional variations in the timing and extent of agrarian reforms led to divergent development within nineteenth-century Germany.Footnote 2

Second, fresh research in development economics and economic history has demonstrated that besides changes on the supply side, an increasing food demand had the potential to accelerate agricultural growth during the preindustrial era. In north-western Europe, early modern urbanisation led to an increase of spatially concentrated demand for food. The exploitation of thick market externalities rendered possible highly efficient factor allocation in the immediate vicinity of large towns. In their wider hinterland, trade volumes were still sufficiently large to carry the fixed costs of establishing secure trade links between surplus producing farmers and consumers. This stimulated regional specialisation on market-oriented food production and an early adoption of agricultural innovations.Footnote 3 In Germany, the development of regionally concentrated proto-industries partly substituted for the low urbanisation level in fostering agricultural growth. However, rural incomes were usually lower than those of town dwellers. Moreover, rural food demand was spatially dispersed and small-scale agriculture in lower-class households made a substantial contribution in feeding the proto-industrial labour force. For all these reasons, rural food markets and very likely regional specialisation were less developed than elsewhere. Thus, we should expect that agricultural output expanded more slowly in Germany than in the more urbanised parts of north-western Europe during the pre-1800 period.

Stressing the role of market integration and demand for agricultural growth during the pre-modern era also implies that the role of institutional reforms in fostering agricultural output growth was limited at best. In this view, agrarian institutions of the ancien régime were sufficiently flexible to permit the introduction of more productive farming techniques. Due to the fact that most peasants enjoyed secure property rights already during the pre-reform era, the introduction of individual property rights over land brought little change to incentive structures but mainly redirected income streams from land.Footnote 4

We contribute to this field of enquiry with an analysis of the returns from sharecropping of the estate of Anholt (Westphalia), which allow tracking the development of grain production over the period c. 1740–1860. This investigation complements the few existing pieces of information concerning agricultural production in Germany prior to 1850 and provides actually the first series that extends backwards before the early 1790s resting on direct evidence. Existing scholarship concerning the quantitative development of Germany's agricultural sector during the century prior to the start of the retrospective national output series in 1850 consists of two groups of studies.Footnote 5 On the one hand, a few older studies provide informed guestimates of agricultural output in Prussia and Germany as a whole in key years back to 1800. They are difficult to reproduce and are probably subject to a wide margin of error.Footnote 6 On the other hand, there exist regional case studies for Bavaria, Westphalia and Saxony. Work on Westphalia in particular rests on regionally disaggregated information for c. 1830 and c. 1880.Footnote 7 Whereas it establishes that demand from the expanding industrial populations in the Ruhr district and the improvement of market access through railway construction promoted agricultural growth, it cannot provide a firm statement concerning growth prior to the onset of industrialisation and railway construction. Our study extends our knowledge on agricultural development in Westphalia back to the 1740s, allowing both a comparison with contemporary Saxony and an assessment of reform effects.

The study begins with an overview of agrarian institutions, structural change and market development in the region that surrounds Anholt, namely, Western Westphalia and the northern Rhineland (section I). Then we describe the institution of sharecropping in Anholt, which determines the character of our sources (section II). Section III develops two alternative series of nominal returns from sharecropping, and section IV constructs a deflator. Section V discusses the evolution of real output and places the results in a comparative perspective. Finally, section VI summarises the main findings.

I

Anholt was located at the western tip of the Prussian province of Westphalia on the border to the lower Rhineland and the Netherlands (Figure 1). Prior to its annexation by the French Empire in 1811 and by Prussia in 1815 Anholt formed an independent lordship of the Holy Roman Empire until 1802. In autumn 1802 the lordship was enlarged and raised in status to become the principality of Salm in order to compensate the owners for losses suffered in the wake of the integration of the west bank of the Rhine into France.Footnote 8 Rees, a small village situated on the Rhine, was only eight kilometres away and offered easy access to river-borne trade.

Figure 1. The lordship of Anholt in 1789.

The estate of Anholt, whose accounting books form the object of this study, constituted the most important material basis of the lordship, and it continued to exist after the latter's absorption by France and Prussia, respectively. Whereas the territory of the lordship became part of the county of Borken in the Province of Westphalia in 1815, rights over land also extended into other neighbouring territories: In 1810–65, 65 per cent of the estate's revenue from sharecropping came from land situated in the county of Borken, 25 per cent from land lying in the Province of Rhineland (counties of Kleve and Rees), and the remaining 10 per cent derived from property in the Netherlands (Province of Gelderland).Footnote 9 Moreover, with respect to both the relationships with agricultural markets and agrarian institutions, the estate of Anholt tended towards the northern Rhineland rather than the Münsterland that lay to the east in Westphalia.

A detailed accounts book of the estate's revenues in 1752–3 allows to reconstruct the land tenure system (Bodenverfassung) prevailing in the region at the beginning of the period under study (Table 1). Slightly over 70 per cent of total income stemmed from some type of property rights over land and people. The remainder came from leasing four mills and a brewing house (5.4 per cent), from entitlements relating to the lordship over the territory surrounding the castle, notably from taxes (11.2 per cent) and from miscellaneous non-classified revenues (11.3 per cent), with two land sales making the largest contribution (4.6 per cent in total revenue).

Table 1. Revenue structure of the Anholt estate in 1752–3 (per cent).

Source: FSSA, Akten Anholt No. 352.

Apart from the tithe (10.8 per cent), income streams that derived from feudal rights over land and peasants made only a modest contribution to the estate's revenue. The rents in kind – pigs and chickens – are difficult to determine. On the one hand, they were part of the fixed rent component of the obligations of farms leased under sharecropping arrangements (see below); on the other hand, a list of feudal obligations existing in the region in 1808 mentions the delivery of hens as the main regular obligation of farms held under serfdom-type tenure. Serfdom, called Eigenbehörigkeit, was not by force hereditary and was attached to farms rather than individuals. The estate also collected a tax on the moveable wealth of a serf that had deceased during the fiscal year, but this amounted to less than 0.1 per cent of total revenue. Hence, the share of 2 per cent (pigs and chickens) forms the upper bound of the likely contribution of feudal entitlements to the estate's revenues.Footnote 10

In the course of the late Middle Ages hereditary peasant leasehold according to the so-called Meierrecht had replaced the strict manorial relationships between lords and peasants in many parts of north-western Germany. However, in the lower Rhineland and in western Westphalia hereditary leasehold was only of limited relevance. In 1752–3, only 3.3 per cent of the revenue of the estate of Anholt came from dues paid by hereditary tenants.Footnote 11 By contrast, about four-fifths of the revenue connected with property rights over land and 57.9 per cent of total income derived from renting out land to peasants on a temporary basis. The two prevailing forms were leasehold with fixed rents and sharecropping contracts whereby peasants delivered the third, sometimes only the fourth part of the harvest to the landowner (the so-called dritte or vierte Garbe, that is, the third or fourth sheaf). The contribution of fixed rent contracts (37.8 per cent of total revenue) prevailed over sharecropping (18.1 per cent) at a ratio of about 2:1. However, most farms holding land under sharecropping also paid a fixed amount of money and – as mentioned previously – were obliged to deliver chicken and eggs as well. The fixed rent component paid by sharecroppers constituted 8.9 per cent of total revenues or about a fourth of the monetary income derived from fixed rent contracts.Footnote 12

The diversified land tenure system prevailing at Anholt in 1752–3 rooted in late medieval times and remained stable until the end of the period under study (c. 1860). Already the first ledger of the estate's entitlements in 1437 documents the tendency to lease former demesne land under sharecropping arrangements. This is echoed by an internal regulation enacted in 1763 stipulating that whenever possible land should be given out to peasants under third sheaf contracts. This seems to have been difficult to achieve, since not only the structure of revenues in 1752–3 but also casual evidence dating from the years around 1600 suggests that fixed rents dominated over sharecropping.Footnote 13 The high transaction costs related to the commercialisation of the third sheaf, which we document in the following section, may have deterred administrators from following these instructions. Nevertheless, the few existing accounting books for the period between 1800 and the late 1850s show that sharecropping continued to provide a relevant and very likely quite stable part of the estate's revenues. Only in 1866 sharecropping was finally abandoned for unknown reasons. A new series of accounting books beginning in 1878 lists neither rents in kinds like chicken nor labour services, which suggests that the agrarian reforms were implemented on the Anholt estate between the mid-1860s and the late 1870s. Perhaps the termination of sharecropping occurred in the same context.Footnote 14

Sharecropping seems to have been widely practised in western Germany during the late Middle Ages, but by the early nineteenth century this institution was mainly confined to western Westphalia and the southern zones of the Lower Rhine regions where it was closely associated with viticulture. Scattered evidence suggests that by the early twentieth century sharecropping had largely disappeared in Germany.Footnote 15 Temporary leasehold at fixed rents, by contrast, emerged as the major form of land tenure around Cologne and other towns in the Lower Rhine area from the thirteenth century onwards and continued to grow in importance during the early modern era. During the early twentieth century, the northern Rhineland — particularly the regions surrounding towns – and the adjacent areas of Westphalia constituted the region in Germany with the highest proportion of land on lease (40 to 50 per cent). This area lay at the south-eastern fringe of a larger zone encompassing much of northern France, Belgium and the Netherlands where leasehold tenure had emerged as an important if not dominant form of land tenure. Existing research links this process with the rise of population density, the expansion of urban demand for agricultural products and the development of intensive agriculture. What follows shows that the estate of Anholt took part in this development.Footnote 16

The importance of temporary leasehold and sharecropping meant that the agrarian reforms of the first part of the nineteenth century bore little relevance for the region under study. Reforms initiated in western Germany during the French period may have been early and radical by comparison. However, in no way did they affect fixed-term leasehold and sharecropping contracts, and since manorial institutions had long lost their significance, their abolition could exert little effect on agrarian institutions. Consequently, peasants and public authorities were not particularly keen to spend time and efforts on negotiating complicated redemption contracts, which resulted in gradual and sometimes slow implementation of reforms. The late implementation of the reform on the estate of Anholt (probably between the late 1850s and the late 1870s) is consistent with this. Contrary to opinions held in part of the literature, changes in the institutional environment clearly were not capable of having an impact on the economic development of the agricultural sector in the northern Rhineland during the period under study.Footnote 17

The accounting book for 1752–3 also suggests that the overwhelming part of the resource flows from peasants to landowners were in money rather than in kind. In particular, the estate did not collect tithes and third sheaf portions in kind. Rather, both types of entitlements were leased out to individuals at that time. Leases of third or fourth sheaves were apparently given mostly to the farmers that owed these dues (see below for a detailed discussion of this arrangement). Leasing out third or fourth sheaf entitlements was practised already during the fifteenth century and mirrors a general tendency elsewhere in contemporary Germany and Europe to monetise peasant obligations.Footnote 18

High levels of commercialisation and monetisation of the relationships between lords and peasants developed in a context of rather poor natural conditions for arable farming. The historical course of the Rhine included several bayous stretching over several kilometres to the north and the east from Rees. In addition, the two rivers Issel (Ijssel in Dutch) and Aa that traverse the estate's territory regularly flooded the area. The subsoil consisted of a mixture of sand, clay and gravel.Footnote 19 The natural environment was thus not well suited for grain cultivation. This is borne out by the relatively low values for the net return on land and the yields of grain cultivation as well as by the great importance of buckwheat cultivation in the zone stretching eastward from Anholt into Westphalia during the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Table 2). In addition, the poor quality of pastures and meadows did not stimulate the development of animal husbandry. This is suggested by the low frequency of references to fixed-term lease contracts for meadows in the estate's accounting books and the relatively low proportion of arable sown with clover both in 1830 and 1880. Nevertheless, the shift from buckwheat and oats to rye and wheat cultivation apparent in Table 2 as well as the introduction of new potato-based crop rotation patterns indicates an intensification of crop farming over time.Footnote 20

Table 2. Structure of arable production (0.01 = 1 per cent).

Sources: FSSA, Akten Anholt No. 355 (Finanz- und Rechnungswesen), Empfang Früchten von Martini 1764 biß dahin 1765; M. Kopsidis, Marktintegration und Entwicklung der westfälischen Landwirtschaft 1780–1880 (manuscript version, PhD thesis, University of Münster, 1994), Volume II, Table IV.j, p. 658, Table V.n, p. 664.

The poor quality of land in a wider region around Anholt forced many households to pursue non-agricultural activities. By the sixteenth century the town of Wesel, situated about thirty kilometres south from Anholt on the east bank of the Rhine, had developed into a centre of fustian production. To some degree, Wesel and its hinterland formed the south-eastern margin of a larger region specialised in fustian production whose centre was Amersfoort in the Province of Utrecht (Netherlands). From the late sixteenth century, the trade shifted into the northern hinterland of Wesel, most notably to the small town of Bocholt, sixteen kilometres east of Anholt. By the late eighteenth century, Bocholt had become the centre of textile production in the north-east of the Lower Rhine and the western Münsterland, and many households in the surrounding rural areas were engaged in cotton spinning as well as in linen and fustian weaving. From 1706–7 to 1789–90 the quantity of fustians exported through Bocholt expanded at an annual rate of 1 per cent, which corresponds with the aggregate growth rate of raw cotton imports of the northern parts of Germany from the 1750s to c. 1790. Despite its growing commercial and industrial importance, Bocholt remained a small town, although its population expanded from 2,600 in 1749–50 to 3,500 in 1806 and 4,700 in 1852. From the 1820s onward, fustian production gave way to the production of pure cotton goods, but local production of cotton yarn continued to be based on simple spinning jennies. Steam power and advanced spinning and weaving technology diffused into the region only during the 1850s. While this was late compared to Twente (Province of Overijssel, Netherlands), the core of the larger textile district of which north-western Westphalia constituted the south-eastern section, it was typical for developments elsewhere in western Germany.Footnote 21

Developments in the western Münsterland and northern hinterland of Wesel were typical for the Rhineland in general. By the early nineteenth century several small manufacturing regions specialising in the production of a variety of textiles and metal goods had developed. In 1849 the district of Düsseldorf (one of five districts of the Prussian Rheinprovinz, which was adjacent to Anholt) comprised the highest share of persons employed in the manufacturing sector of all twenty-five Prussian administrative districts, and it showed the highest population density in Prussia both in 1816 and 1864.Footnote 22

The development of manufacturing activities in small towns and rural locations implied a dispersed demand for basic foodstuffs. However, we have no systematic information on grain trade in the region under study. The small town of Anholt obtained a formal market only in 1793, and in 1806 there were complaints over poor demand for grain.Footnote 23 The sale of grain accruing to the estate under third sheaf contracts in 1843 offers a glimpse at the decentralised trade with grain: There were seventeen buyers that all came from the dominion of Anholt or its immediate vicinity. There obviously existed a liquid market in grain that was able to absorb considerable quantities.Footnote 24 Casual evidence from other parts of the Rhineland suggests that by the early nineteenth century high levels of monetisation of the agrarian economy and the development of several districts of dispersed rural manufacturing had produced a system of regional grain markets each of which rarely extended over a radius of more than two or three dozen kilometres.Footnote 25

In contrast to other textile districts, the region around Anholt did not experience substantial population growth. From 1818 to 1870 population in the county of Borken, of which Anholt was a part, expanded at an annual growth rate of only 0.24 per cent. However, as mentioned earlier, part of the land owned by the estate lay outside Westphalia. If population figures from the neighbouring regions of Gelderland (Netherlands), Kleve and Rees in the adjacent Rhineland are included and weighed according to the geographical distribution of revenues from sharecropping of the estate of Anholt in 1810–65, the rate of growth increases to 0.36 per cent per annum.Footnote 26 During the second half of the eighteenth century, the pace of demographic growth may have been slightly slower. In those parishes of the Münsterland for which suitable information exists, population expanded annually by 0.19 per cent between 1749–50 and 1795.Footnote 27 In sum, Anholt's economic environment was characterised by an intensification of arable farming; highly commercialised and monetised contractual relationships on land markets, an early development of non-agricultural activities that fostered the development of local grain markets, but with slow population growth.

II

Sharecropping on the estate of Anholt, the so-called third or fourth sheaf, implied that the estate obtained a third or a fourth of the output from arable farming. In most cases, sharecroppers also had to pay a fixed money rent, to deliver chicken and eggs, and to provide a few labour services.Footnote 28 Our analysis considers exclusively the sharecropping component of this arrangement. Entries in accounts books concerning the third or fourth sheaf take the form of money values rather than quantities of products. The high level of monetisation of resource flows from peasants prevailing at Anholt apparently meant that the share of output that accrued to the landowner was sold. Provisions enacted by the estate administration in 1780, 1838, 1843 and in an unspecified year in the second half of the nineteenth century (probably during the 1850s or early 1860s) regulated the sale of the portion of the harvest belonging to the landlord. They stipulate that the owner's share was to be sold by auction one or two months before harvest. The buyer had the opportunity to be present when the sheaves of the peasants and the landlord were separated after harvest, and peasants had to bring the latter to the barns prior to their own sheaves. The estate provided labour for threshing, but the farmers had to provide the meals for the labourers. Farmers were also required to deliver the grain to the buyer after threshing, which could extend until the following March (1843). The regulations of 1838 and 1843 also prescribe that payment was to be settled by February. It is clear, therefore, that the income registered by the accounts books of the estate refers to the returns from the harvest of the previous year.Footnote 29

As mentioned in the previous section, sharecropping contracts were virtually transformed into fixed rent contracts during some periods although they were still designated as third sheaf arrangements. This holds in particular for 1782–1803 and from 1859 onwards; in 1866 sharecropping was abandoned, and all land was leased out under fixed-term leasehold contracts. Sharecropping arrangements were renegotiated every three, six or nine years, depending on the period considered and the individual farm. During the period 1782–1803, farmers preferring fixed rent contracts could obtain leases whose values were determined on the basis of the grain prices prevailing during the twenty previous years; from 1859 onwards the reference period appears to have been ten years. For the sub-period 1782–1803, highly sticky returns of individual farms over consecutive years and fragmentary evidence from renegotiation rounds suggest that fixed rent arrangements dominated the contract periods of 1782–9, 1792–7 and 1798–1803.Footnote 30 We need to take into account these changes in sharecropping contracts when we use their returns for tracking the output of crop production in our analysis.

III

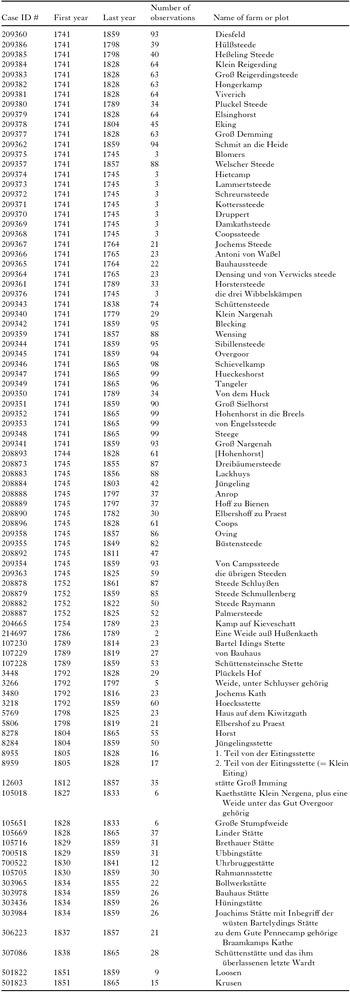

For the entire period from 1741 to 1865 we found ninety-one units subject to sharecropping – either entire farms or individual plots. Ninety units had to pay the third sheaf, one the fourth and two paid both the third and fourth sheaf (see Appendix). Since we do not possess systematic information on the characteristics of leased units, such as size, we decided to drop the information relating to the fourth sheaf and concentrated on sharecropping of the third sheaf type. However, most units were not stable over time. In part, this must have been related to reconfigurations of farmsteads when changes in ownership occurred, but institutional shifts between fixed-term leaseholds and sharecropping arrangements certainly also took place.

Figure 2 shows the number of farmsteads or individual plots for which we have information on payments relating to the third sheaf for every year between 1741 and 1865, when sharecropping was abandoned. The institution of sharecropping seems to have experienced a crisis during the agrarian depression of the 1820s, but there are also several years with gaps in the accounts books during this decade. The period from the late 1760s to the early 1790s, which we earlier identified as a time when most sharecropping arrangements tended towards fixed-term leases, is also characterised by many gaps in the documentation. Finally, the drop in the number of observations from 1860 onwards reflects the abandonment of sharecropping that becomes apparent in the written sources from the late 1850s. Given the dramatic drop of the number of observations in 1860, the ambiguity of the concept of the third sheaf during the first half of the 1860s and the difficulty to find product price series extending beyond 1860 (see below) we limit our analysis to the years until 1859. Thus, we end up with 3,939 individual entries concerning payments relating to the third sheaf that are attributable to ninety units (farms or individual plots) and cover ninety-five years from 1741 to 1859.

Figure 2. Number of farms and individual plots subject to sharecropping (third sheaf), 1741–1865.

Book entries of revenues from land were denominated in several currencies that circulated in the lower Rhineland and the Netherlands. In order to render them comparable and to deflate them with product prices we converted them to grams of silver.Footnote 31 Based on these values we construct two series of nominal returns from sharecropping of the third sheaf type; the result is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Nominal revenue from sharecropping (third sheaf), 1741–1859 (grams of silver).

The first series is the total nominal return from the third sheaf of thirteen well-documented farms with information for at least eighty-three identical years. This series has the advantage of being derived from a homogeneous database, and eighty-three years is not much less than the ninety-five years covered by the entire database. However, it uses little more than a quarter of the available information, that is, 1,170 of almost 4,000 observations. Because it may suffer from selection bias we interpret the total third sheaf return of the thirteen farms with the best documentation only as one possible approximation to the true trajectory of the aggregate sharecropping rent.

The second series aggregates the information for all farms by estimating an unbalanced panel regression with fixed effects for time and farms:Footnote 32

$$\begin{equation}

\ln ({R_{ij}}) = c + \sum\limits_{i = 1}^{k - 1} {{\alpha _i}} {F_i} + \sum\limits_{j = 1}^{l - 1} {{\beta _j}} {T_j} + {\varepsilon _{ij}}

\end{equation}$$

$$\begin{equation}

\ln ({R_{ij}}) = c + \sum\limits_{i = 1}^{k - 1} {{\alpha _i}} {F_i} + \sum\limits_{j = 1}^{l - 1} {{\beta _j}} {T_j} + {\varepsilon _{ij}}

\end{equation}$$

with Rij being the third sheaf rent paid by farm i in year j, F containing farm-specific dummy variables, and T being a set of dummy variables for the time effects. The inclusion of a constant c implies that time and farm fixed effects are normalised on the last year and the last farm, respectively. We estimate equation (1) using standard OLS. The index value for an individual year j is then calculated as the exponential of the sum of the constant c and the estimated time effect coefficient βj . We calibrate this series with the average return for 1745, when coverage was particularly broad (Figure 2). Consequently, the series based on panel regression represents the trajectory of the average third sheaf revenue per farm over time.

Applying the Breusch-Pagan test to the OLS estimate of equation (1) suggests the presence of heteroscedasticity, meaning that third sheaf returns were more variable in some years and/or farms than in others. Particularly farms documented over longer periods may show more variation with respect to sharecropping rents than units covered for only a few years. To explore the sensitivity of the series based on panel regression with respect to heteroscedasticity, additional estimates have been carried out using feasible GLS with error variances obtained from the OLS estimate partitioned alternatively according to farms and years, respectively. The resulting two-time series deviate from the one based on OLS by 2 per cent (error variances partitioned with respect to farms) and 0.6 per cent (error variances partitioned with respect to years), and the time trend of all three series is identical. Hence, it is possible to conclude that heteroscedasticity, while clearly present, does not bias our results in a relevant way, and we rely solely on the original OLS estimate in the following analysis.Footnote 33

The obvious advantage of the average sharecropping rent estimated using panel regression over the alternative thirteen farms series is that it makes full use of all available information. An important weakness, however, stems from our lack of knowledge about the farm specific characteristics that are captured by the farm fixed effects. Differences in levels of the third sheaf rent paid by individual farms can result from differences in both size and productivity. Thus, differences between unobservable farm specific characteristics may be partly related to productivity and output growth. Therefore, we consider the series based on panel regression as a conservative benchmark that indicates the lower bound of output growth.

A look at Figure 3 suggests two conclusions: First, in the last two decades of the eighteenth and the first years of the nineteenth centuries, nominal revenues from sharecropping were rather sticky, particularly in comparison with output prices (see Figure 4 below). This reflects the tendency, noted in the previous section, of sharecropping contracts to represent fixed rent leaseholds during this period. From 1804 onwards, by contrast, revenues from sharecropping suddenly became much more volatile again. This transition is obviously linked to the creation of the principality of Salm in the winters of 1802–3, which apparently led to a comprehensive revision of leasehold arrangements in favour of sharecropping, although written sources do not document this regime change. Second, nominal returns from sharecropping increased consistently over time; R2 of the exponential trend is 0.64 for both series. The exponential trend of the thirteen farms series is slightly steeper (0.97 per cent p. a.) than for the panel-based average return (0.82 per cent p. a.), but the differences are rather small. Both trends are positive. Thus, the two series are mutually consistent, and we can state that nominal revenues from sharecropping rose at an annual rate of 0.8–1.0 per cent.

Figure 4. Price of crop basket in grams of silver per litre, 1740–1860.

IV

In order to derive an output index from the returns of the third sheaf, monetary values need to be converted into real quantities using a deflator. No written contracts for the sales of the third sheaf exist, so we know neither the share of different types of grain being sold nor the prices at which sales took place. In order to construct a deflator we rely on annual averages of grain prices from Xanten, a town situated about twenty kilometres south from Anholt on the left bank of the Rhine (see Figure 1). Information is available for barley, buckwheat, oats, rye and wheat, and is converted into grams of silver per litre of grain. We combine the prices of these five crops into the price of a synthetic grain price basket. The weight of the price of each crop is defined by its share in sown acreage around 1830 in the county of Borken where Anholt was located (Table 2). The resulting price series of this basket in terms of grams of silver per litre of grain is shown in Figure 4.

The information on output structure in 1764–5 and 1878/82 given in Table 2 allows exploring the sensitivity of the deflator with respect to alternative weights for the underlying price series. A price index weighted according to the share in sown acreage in the county of Borken in 1878/82 yields values that are almost identical with those calculated with the weights for c. 1830. The effect of parallel declines in the shares of oats and wheat on the price level apparently cancel each other out, and there were no systematic changes in relative prices among the considered crops.

A deflator that weighs the prices of individual crops according to their proportion in peasant deliveries in kind to the estate of Anholt in 1764–5 follows the same long-term trend as the index based on the weights in c. 1830. This again implies that there were no relevant changes in the relative prices between individual crops. The price index based on the weights in c. 1830 is robust with respect to alternative weights, therefore, and we use only this deflator in the subsequent analysis. Nevertheless, as mentioned earlier the structure of obligations in kind on the estate of Anholt in 1764–5 suggest a much greater weight of barley, buckwheat and oats in total output than the structure of area sown around 1830 and 1880. Partly the difference may stem from the fact that the estate of Anholt was not necessarily representative of arable farming in the county of Borken, but particularly the increasing importance of rye points to a (plausible) tendency towards a more intensive use of land. Since barley, buckwheat and oats were cheaper than rye and wheat the price in terms of grams of silver per litre of grain when using the weights in 1764/5 is about 10 per cent below the level of the deflator based on the weights in c. 1830. Translated into a growth rate over the period 1765–1830 the annual rate of increase is 0.16 per cent. In combination with the use of a basket with fixed weights we can state, however tentatively, that about 0.1–0.2 per cent of real output growth in c. 1765–1830 derived from shifting production to goods with higher value added.

V

Since sharecropping involved the transfer of a fixed share of output to the landowner it is possible to derive an index of real crop output by deflating nominal revenues from the third sheaf with the price of the grain basket (Figure 5). Two details warrant consideration: First, the entries concerning payments for the third sheaf relate to grain harvested and sold in the previous year. Therefore, we lag nominal revenues by one year for the construction of an output index. This correction is essential for the short-term consistency of the index. In the lagged version, low output levels in 1770, 1815–16, 1830, 1845–6 and 1853 precede the serious food crises in the following years documented by price series and contemporary reports. Without this correction short-term fluctuations of the output index do not correspond to known food crises, and while the long-term increase is somewhat stronger than depicted in Figure 5 fluctuations around the trend are also larger.

Second, it is necessary to take into account the tendency of third sheaf contracts to come close to fixed leasehold arrangements during the last two decades of the eighteenth century. Specifically, we deflated lagged nominal third sheaf returns in the contract periods 1781–88, 1791–96 and 1797–1802 with a twenty year average price index ending in 1780, 1790 and 1796, respectively (see section III). Despite this correction, index values for the last two decades of the eighteenth and the first years of the nineteenth centuries may understate the true level of output because fixed leasehold rents based on past output and price information do not capture the movement of output during the contract period. Thus, the strong increase of the output index in the middle of the 1800s may partly result from the return to true sharecropping in the wake of the creation of the principality of Salm in the winters of 1802–3.

Over the entire period from 1740 to 1858 output tracked by real revenue from sharecropping expanded at an annual rate of 0.4 to 0.5 per cent, depending on whether one looks at the thirteen farms with the best documentation or the estimate derived from panel regression (Table 3). Output growth equalled or slightly surpassed population growth – perhaps around 0.2 in the second half of the eighteenth century and slightly less than 0.4 per cent c. 1800–70 (see section II).

Table 3. Growth rate of real crop output index by sub-period (exponential trend, per cent per annum).

However, the magnitude of output growth differed across sub-periods (Table 3). In the first sub-period of 1740–69 the two indices show opposing trends, which precludes a firm statement regarding the mid-term movement of crop production. Part of the difference can be explained by the fact that 1740, when output may have been quite high, is not covered by the series based on the thirteen farms with the best documentation. Factors affecting the German economy negatively during this period were two major wars, namely, the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–8) and the Seven Years’ War (1756–63) and, possibly, erosion. Stagnation of international trade and declining real wages of urban labourers corroborate the impression that the three decades c. 1740–70 were a difficult time for the German economy.Footnote 34

For the last third of the eighteenth century, by contrast, the two indices suggest that crop production expanded at an order of magnitude of 0.5–0.8 per cent p. a.Footnote 35 Depending on the index that one prefers part of this growth may represent reconstruction growth compensating for the war-related decline during the preceding three decades. In any way, for 1740–99 the two indices consistently suggest a positive trend of 0.4 and 0.7 per cent p. a., respectively. Moreover, the indices in Figure 5 and Table 3 may understate true output growth during the late eighteenth century because sharecropping relations tended towards fixed rent leasehold during the 1780s and 1790s. We therefore conclude that crop output very likely exceeded regional population growth by a considerable margin during the last third of the eighteenth century, if not earlier. In the region under study, availability of food per capita improved during the decades before 1800.

The high index values in 1804–12 (except 1810) constitute the longest deviation from the long-term trend. As mentioned earlier the strong rise in 1804 was at least partly related to institutional factors that led to an underestimation of the true output level in the years preceding 1804. No argument of this kind can account for the decline of third sheaf returns between 1804–12 and the first half of the 1820s (data points for 1821 and 1824), when climatic conditions were highly favourable for grain farming.Footnote 36 Furthermore, possible errors in currency conversion stemming from war-related monetary disorder offer only a partial explanation of the high level of the output indices during the period 1804–12.Footnote 37

If one accepts that output levels in 1804–12 laid above the long-term trend, heightened demand for food because of war elsewhere offers a possible explanation. Until 1811 the region was only a little affected by the Napoleonic Wars. Quartering of troops, which had to be provided with food, occurred only during a short phase of the War of the Fourth Coalition in late 1806 and at the beginning of the Russian Campaign late in 1811. As both events occurred after harvest they did not affect grain farming. Moreover, before late 1811 the principality of Salm did not contribute troops to the French war effort so that there was no diversion of labour and farm animals to the war economy.Footnote 38 Therefore, until the crop year 1811–12 agricultural factor input remained intact and peasants could respond to rising market demand for grain elsewhere. However, given the uncertain quality of the deflator during the war years this explanation is at best highly tentative.

After 1812 estimated output fell and reached a low point in 1816 as consequence of a short-term climate shock following the massive eruption of the Tambora volcano in 1815.Footnote 39 Thereafter estimated output rose until the end of the period under observation, albeit with large fluctuations. The magnitude of the long-term trend depends on the starting year chosen, because the crisis in 1815–16 implies a base effect. For this reason, the two final columns in Table 3 show exponential trend growth rates for periods starting alternatively in 1815 and 1821, when the harvest was very good. These estimates suggest that between the Congress of Vienna (1815) and the late 1850s output expanded at an annual rate of 0.7–0.8 per cent.

In a comparison of the period 1815–58 with the eighteenth century two points stand out: First, both visual inspection of Figure 5 and the R2 values of exponential trend computations suggest that output growth became more volatile after 1800. Partly, this is related with methodological issues; leasing third sheaf entitlements at fixed rent, which by definition reduces volatility, appears to have been more common in the eighteenth century than later on (see earlier). At the same time, the period from 1815 to the 1850s saw a rapid alternation between favourable climate in the early 1820s and a succession of negative weather shocks, so that climate-related hazard may have been more pronounced in the first six decades of the nineteenth century than in the preceding period.Footnote 40

Second, compared with sub-periods prior to 1800 crop production rose at a similar pace or slightly faster in 1815/21–1858, which underscores the continuity of the growth experience of the region under study between the mid-eighteenth and mid-nineteenth century. It is also possible to compare our index with point estimates of selected output aggregates for c. 1830 and 1878/82 for the entire north-western part of Westphalia that shared sandy soils. In the latter region value added of crop production rose with an annual rate of 1.25 per cent between c. 1830 and 1878/82. This suggests that the rise of spatially concentrated industry and the massive extension of infrastructure that facilitated market access of agricultural producers started in Anholt as elsewhere in northern Westphalia around 1850 causing an acceleration of agricultural growth during the third quarter of the nineteenth century.

We have little to no information about the causes underlying agricultural growth in the region surrounding Anholt prior to the 1850s. Any explanation must remain speculative at this stage of research. We noted in section IV that during the last decades of eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth centuries the shift of production away from buckwheat and oats to rye and wheat, which were more valuable crops, accounts for 0.1–0.2 per cent, that is, about a quarter, of estimated output growth. Later in the nineteenth century, incremental changes in patterns of land use, such as the expansion of clover and later on potato cultivation, as well as better agricultural techniques, such as the improvement of ploughs and new seeds, had a further potential to expand output. It is noteworthy that agricultural growth occurred in a region characterised by decentralised textile manufacturing, where a growing number of households demanded for traded food. Several decades before the onset of railway construction, market access was facilitated by the construction of paved roads; between 1815 and the 1850s road construction in Westphalia demonstrably reduced gaps in grain prices across space and thus contributed to market integration. Sustained growth of crop production during the pre-1850 period went together with a steady expansion of local and regional food demand at the farm gate.Footnote 41

Table 4 concludes this discussion by placing the results for Anholt in a broader north-western European perspective. Three elements stand out: First, with an estimated annual growth rate of 0.4 to 0.7 per cent in 1740–99 the trend of crop output of the farms belonging to the estate of Anholt falls in the upper range of the observed growth rates for this period. Only in Scania in southern Sweden did crop output expand at a similar or quicker pace. The borderland between Westphalia and the Rhineland apparently belonged to the most dynamic agricultural regions of north-western Europe during the eighteenth century. Second, Anholt's growth rate in 1815/21–1858 was rather less than average. The acceleration of output growth during the first half of the nineteenth century is less visible in the region under study than elsewhere. The reason could be that, third, the borderland between Westphalia and the Rhineland showed very low population growth by comparison – 0.2 per cent in the second half of the eighteenth century and 0.4 per cent for c. 1816–70. Consequently, it was one of the few regions where food availability per capita increased over the period under study, albeit only at an order of magnitude of 0.2 per cent per annum. However modest, this created a potential for market integration and regional specialisation.

Table 4. Growth rates of vegetable output (‘crop’) and population (‘pop’) in north-western Europe, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (per cent per annum).

Sources: Great Britain: S. Broadberry, B. M. S. Campbell, A. Klein, M. Overton and B. van Leeuwen, British Economic Growth, 1270–1870 (Cambridge, 2015), pp. 31, 115; Netherlands (1800): J. L. van Zanden and B. van Leeuwen, ‘Persistent but not consistent: the growth of national income in Holland 1347–1807’, Explorations in Economic History, 49 (2012), 119–30 (126); Netherlands (1821–58): J.-P. Smits, E. Horlings and J. L. van Zanden, Dutch GNP and its Components, 1800–1913 (Groningen, 2000), pp. 109–11, 121–3, 124–6; M. Goossens, ‘Belgian agricultural output, 1812–1846’, Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Nieuwste Geschiedenis – Revue Belgique d'histoire contemporaine, 24:1–2 (1993), 1227–73 (240, 267); Scania crop: M. Olsson and P. Svensson, ‘Agricultural growth and institutions: Sweden, 1700–1860’, European Review of Economic History, 14:2 (2010), 275–304 (302–3); Swedish population: Historical statistics of Sweden; Bavaria crop: M. Böhm, Bayerns Agrarproduktion 1800–1870 (St Katharinen, 1995), p. 386; Bavarian population (1816–60): A. Kraus, Quellen zur Bevölkerungsstatistik Deutschlands 1815–1875 (Boppard am Rhein, 1980), p. 64; Saxony: U. Pfister and M. Kopsidis, ‘Institutions vs. demand: determinants of agricultural development in Saxony, 1660–1850’, European Review of Economic History, 19:3 (2015), 275–93 (285 and online appendix).

The experience of farmers in Anholt was far from typical for Germany as a whole. The acceleration of output growth in the early nineteenth century was much more marked in Saxony than around Anholt, but both in Saxony and Bavaria output of staple food barely kept pace with population growth. This underscores the favourable experience of Anholt based on highly commercialised land tenure systems, easy market access through river transport, and the development of dispersed textile manufacture.

VI

This study has explored the pattern of agricultural development for a German region prior to the onset of industrialisation and railway construction around the middle of the nineteenth century by using information concerning revenues from sharecropping on an estate situated in north-western Westphalia at the border to the lower Rhineland and the Netherlands. We find sustained growth of crop output in the final third of the eighteenth century and possibly in the decades before, as well as from the Congress of Vienna (1815) to the 1850s. Growth accelerated only slightly between the two periods, namely, from 0.5–0.8 per cent to 0.7–0.8 per cent per annum. Growth in the first half of the nineteenth century was slower than during the following decades until c. 1880 when rapid industrialisation and improved market access through railway construction stepped up demand for marketed agricultural products.

Crop output growth on Anholt farms in c. 1740–1800 was probably a bit faster than in Saxony – the only other German region for which we have comparable estimates reaching back into the eighteenth century – and on a par with rates of expansion found for developed regions in north-western Europe and southern Sweden at that time. The favourable experience of Anholt is underscored by relatively slow population growth, which implied an increase in per capita food availability. This also holds for the first part of the nineteenth century when aggregate crop production expanded rather slowly by comparison.

The experience of sharecroppers at Anholt underscores the continuity of agricultural development over the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Certainly, the onset of rapid industrialisation and the improvement of infrastructure around 1850 brought about an acceleration of the pace of the expansion of agricultural output. But, there was sustained growth already during the previous century, albeit at a modest level. Apart from a possible output boom due to a temporary expansion of demand for marketed food during the Napoleonic Wars, the rate of expansion was fairly steady and accelerated only gradually during the first part of the nineteenth century. Notably, the widespread practice of temporary leasehold and the insignificance of manorial institutions implied that agrarian reforms initiated during the French and Prussian period had little impact on the agrarian sector in the lower Rhineland and western Westphalia. By contrast, the development of dispersed export industries and easy market access, promoted notably by the availability of river transport, created a potential for demand-led agricultural development. As a whole, many parts of Germany may have experienced economic stagnation during long periods prior to industrialisation. Nevertheless, regions that were drawn into the orbit of long-distance markets for manufactures – such as Saxony and the banks of the Lower Rhine including western Westphalia – experienced a sustained development also of their agricultural sector at least from the middle of the eighteenth century onwards.

Acknowledgements

Support from the German Science Foundation (DFG), grant PF 351/8 is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Mats Olsson, Patrick Svensson, Anna Missiaia, and Georg Fertig for valuable comments on a first draft during a Swedish-German workshop on Agricultural History, held at IAMO in Halle (Saale) in December 2015. This workshop has been co-financed by the Swedish Research Council (grant no. 421-2012-5581).

Appendix

List of farms and plots leased under sharecropping arrangements and procedures followed in data handling