In 1801 the British government began a decadal census of its inhabitants, and those conducted between 1841 and 1911 are available to view online.Footnote 1 The English census of 1881 is the first to allow an electronic search of the population by occupation.Footnote 2 By entering the word ‘piano’ or ‘pianoforte’ in the search engine, large numbers of the piano-related workforce are brought to light. Their name, age, address, birthplace, marital status and occupation are revealed, and without further enquiry this data alone adds greatly to our understanding of the workforce in terms of its size, gender, occupation and location. Nearly 6,500 men, women and children are found to have worked in approximately 400 piano-related occupations across 42 English counties – the majority based in London. But these figures tell only part of the story. A more complex interpretation may be drawn from secondary information not immediately apparent from the data. The social standing, entrepreneurial spirit, family history, social acquaintance, success, hardship and disappointment of the workforce may all be appraised via the census, and their individual and collective careers provide a surprising insight into the piano-making industry of mid-Victorian England.

Background

In the year before the 1881 census was taken, the combined output of the English piano industry was estimated at between 30,000 and 35,000 instruments. Annual production had increased by a third since the previous census, and was set to approach 100,000 instruments by the end of the century, most of them made in the capital.Footnote 3 The Post Office London Directory for 1881 lists 233 makers operating in the city: 106 firms and partnerships and 127 smaller concerns. Large firms such as Brinsmead, Broadwood, Collard & Collard, Chappell and Challen employed several hundred workmen, while the smallest, like that of John Campell, employed perhaps one man and a boy.Footnote 4 It is doubtful whether Campell produced a great many instruments, but according to his census return he considered himself a ‘master pianoforte maker’.Footnote 5 More than 60 other ‘makers’ listed in the directory that year were not master pianoforte makers according to their census returns, but dealers, music setters, teachers, tuners and makers of other instruments. Some also recorded additional occupations, such as lodging-house keeper, cork merchant and Chelsea pensioner. The directory classification for ‘piano maker’ was possibly too narrow for some.

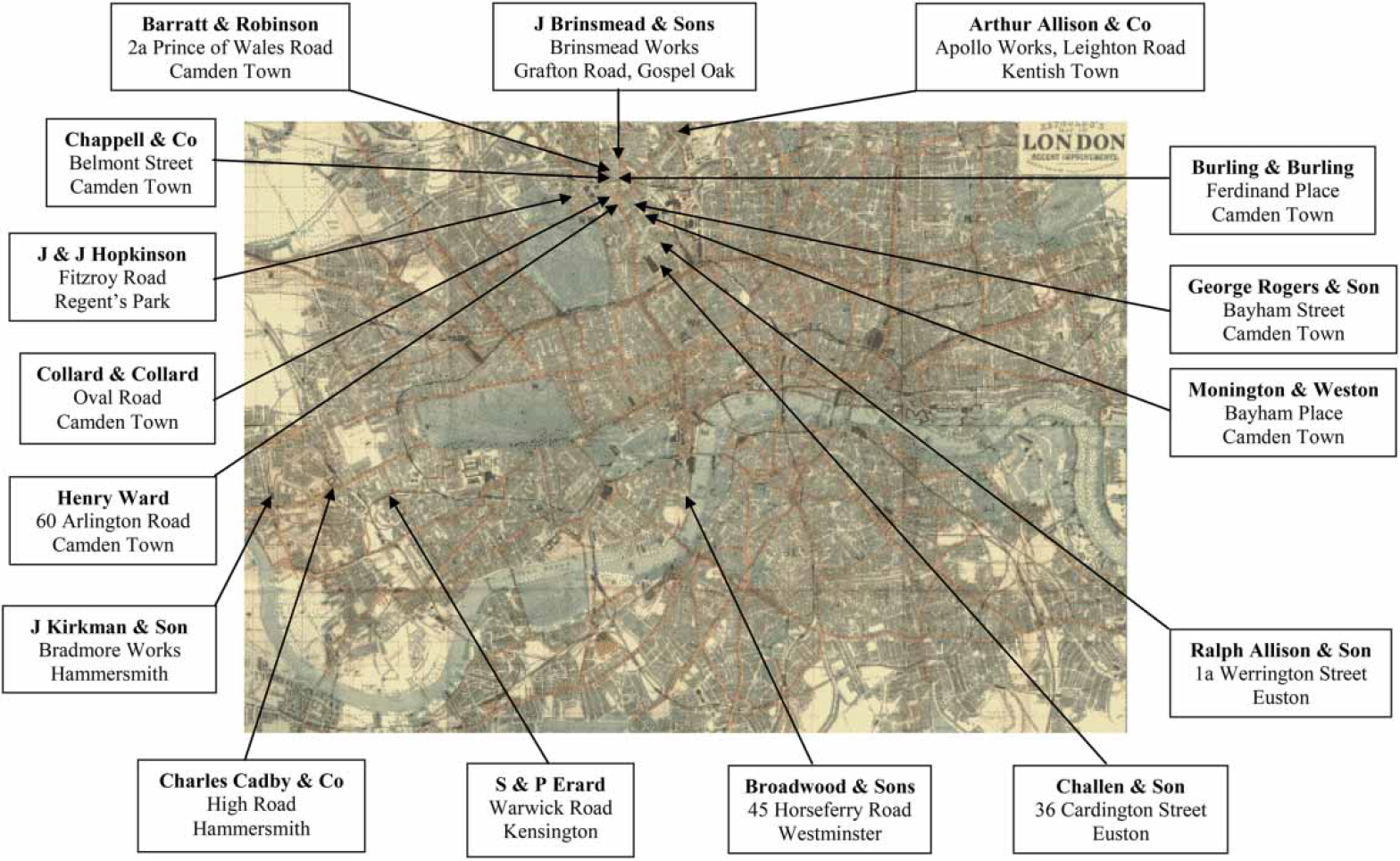

According to Ehrlich, pianos made in England at this time were the creation of approximately 30 reputable firms, excluding numerous so-called ‘shoddy’ firms making sub-standard produce (of which Campell's establishment may have been one).Footnote 6 In 1881 the London piano-manufacturing industry covered an area from Hammersmith in the west, to Westminster in the east, to Kentish Town in the north. Figure 1 shows this area on a map, marked with the principal reputable firms noted in the Post Office London Directory that year.

Figure 1. Map showing the location of major London piano factories in 1881. 1890s Reynolds map of London reproduced courtesy of Lee Jackson of VictorianLondon.org.

The hub of the piano industry centred on St Pancras, where the 1,893 resident workers identified in this study comprised 0.8% of the local population.Footnote 7 Several factors made the area popular with the industry: the established supply of timber, brass, iron and ivory to the existing furniture trade; the availability of large properties and cheap rents north of the city centre; and plentiful haulage for heavy, bulky goods via the Regent's Canal and the railway terminals at King's Cross, Euston and St Pancras. Some of the older firms in the area had enjoyed these facilities since the 1860s, migrating north from the industry's origins in Soho via premises along Tottenham Court Road, but new firms had also gathered in the area to draw on the ready workforce and exploit the same amenities.

Figure 2. Former factory of Arthur Allison & Co., Apollo Works, Charlton King's Road/Leighton Road, Kentish Town: now residential flats

Figure 3. Former factory of Arthur Allison & Co., Apollo Works, Charlton King's Road/Leighton Road, Kentish Town: now residential flats

The northernmost factory noted in the 1881 Post Office London Directory was that of Arthur Allison at the ‘Apollo Works’ in Kentish Town (see Figures 2 and 3), built with a footprint approximating the shape of a grand piano, and occupying a site on the corner of Leighton Road and Charlton King's Road, within easy access of the Kentish Town Overground station at the far end of Leighton Road. The company had been established 44 years at the time of the census, and its annual production had grown to around 600 instruments.Footnote 8

Three-quarters of a mile to the west was the Brinsmead factory, covering nearly an acre along the Grafton Road in Gospel Oak (Figure 4), and built by 1874 to replace the company's old premises in Chenies Street, Tottenham Court Road. The factory was equipped with ‘a most complete system of machinery’ and a drying room said to be the largest in Europe:Footnote 9

Figure 4. Illustration of the Brinsmead Factory, 1874.

The main body of the works, though constituting only a single building, really consists of four distinct buildings, being divided into that number by brick walls of great solidity […] The horizontal dimensions of the building are 189 ft by 45 ft. It is constructed with four floors and a low basement storey, which is asphalted, and contains the shafting from which the machinery above is driven. On each floor there are two large shops, a store room, and an examining room, making four rooms in all, or 16 in the whole building.

Alleged production capacity was 3,000 pianos a year with a workforce of 300 men (i.e. ten pianos per man), but the company's output in 1880 is estimated to have been less than a quarter of that sum.Footnote 10 Of the 700 or so instruments produced in 1881, a number of newly patented ‘Top Tuner’ uprights counted among them, but the model achieved little practical or commercial success and was eventually withdrawn.Footnote 11

At the foot of Grafton Road, near the mainline station of Kentish Town West, was the young firm of Barratt & Robinson, established only four years when the census was taken and producing approximately 100 instruments a year, though set to acquire many of its larger competitors over the course of the following century.Footnote 12 A short walk to the south along Ferdinand Street was the Chappell steam factory, with 109 men and 20 boys working on a site stretching west to Belmont Street. The company produced about 600 pianos a year at the time of the census.Footnote 13 To the west of the Chappell factory, beyond the sprawling goods yard of Chalk Farm Station, in a largely residential area on the edge of Primrose Hill, the workforce of J. & J. Hopkinson was making about 800 pianos a year,Footnote 14 and crossing the railway line to the east, Collard & Collard were producing about 1,950 pianos, with a workforce of 601.Footnote 15 They had twice built their factory on the same site on the Oval Road, first in 1851 and again the following year after suffering a factory fire.Footnote 16 Their tripartite premises comprised a round, four-storey building for the production of upright pianos (Figure 5), a rectangular building to the rear producing grand pianos, and an assortment of outbuildings opposite where iron frames were fettled, finished and bronzed, and completed backs were strung.Footnote 17 One of the women identified in the census worked here as a ‘back coverer’.Footnote 18 In the year of this study, a newly patented, pedal-operated ‘celeste’ muting strip was introduced to the grand production line.Footnote 19

Figure 5. Former factory of Collard & Collard, Oval Road, Regent's Park, 2010.

Other factories operating in Camden Town were Burling & Burling in Ferdinand Place (making about 500 pianos per year), Henry Ward on the Arlington Road (output unknown),Footnote 20 George Rogers & Son in Bayham Street (approximately 300 pianos), and Monington & Weston (est. 1858) in Bayham Place. Monington and Weston ‘at one time employed 100 highly skilled wood carvers, and in the years when heavy mahogany carving was popular [their] pianos were in great demand’.Footnote 21 Further south were Ralph Allison & Sons in Werrington Street near Euston Station,Footnote 22 and on the western boundary of the station Challen & Son, with a steam factory at 36 Cardington Street.Footnote 23 Challen were making about 500 pianos a year at this time.Footnote 24

Not every firm sought to base its works near Camden Town. The western boundary of the industry was staked by the ‘Bradmore Works’ of the Kirkman factory in Aldensley Road, Hammersmith, where about 900 pianos were made in 1881.Footnote 25 Their close neighbour to the east was the Cadby piano factory, built in 1874 on the High Road (now Hammersmith Road), on a site adjoining Olympia Hall today.Footnote 26 It covered 1.5 acres and was known as Cadby Hall:

Four distinct blocks were built along with showrooms, which were approached by a carriage drive to the entrance porch […] Above the three floors of showrooms were rooms occupied by the housekeeper. Administration and private offices for use by members of the firm were situated at the rear of the building […] Set back forty feet from the rear of Cadby Hall itself was a five-level factory in which the finer portions of the pianos were crafted and assembled. Behind the factory block was a five-level mill where most of the sawing, planing and heavier tasks associated with piano making were executed. Towards the rear of the property were additional timber stores, a packing-case shop, stables and a coach-house.Footnote 27

Further to the east, Erard's factory on the corner of Warwick Road and Pembroke Road, Kensington, employed 127 men in 1881, manufacturing between 500 and 660 pianos per year.Footnote 28 Here

[t]he principal buildings were two four-storey blocks, each some 140 feet in length and divided into nine bays with wide segmental-headed small-paned windows. These blocks […] were at the eastern end of the site, parallel to each other and to Pembroke Road. To the west, on each side of a long driveway, were a number of other structures which, on the evidence of the French factory, were probably used principally for the storage and seasoning of timber. Initially the factory occupied an area of about two acres […but] the factory was enlarged in 1859 when a further one and a half acres immediately to the south of the main site were added to its grounds […so] at its greatest extent the factory occupied some four acres of land.Footnote 29

The largest factory to the south and east, in Horseferry Road, Westminster, had also been much extended since John Broadwood secured the original site in 1823, and a visiting journalist in the 1840s recorded a lively description of the factory's layout and activities.Footnote 30 By 1881 the company employed 629 men and 67 boys making approximately 2,600 instruments a year.Footnote 31 Between them, these factories produced more than 10,000 pianos in 1881, Broadwood being the most prolific, then Collard & Collard (1,950), Kirkman (900), Hopkinson (800), Brinsmead (700), Allison (600), Erard (550), Chappell (500) and Burling & Burling (500).Footnote 32 In terms of efficiency, however, their ranking appears to have been rather different. Table 1 shows the average number of pianos made per capita at Chappell, Erard, Broadwood and Collard & Collard – a calculation made possible by members of management recording the size of the company workforce on their census return.Footnote 33

Table 1. Major factories for which both workforce and output figures are recorded, allowing an estimation of their output per capita.

| Factory | Census workforce 1881 | Output 1880 | Estimated pianosper man per year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chappell | 129 | 600 | 4.6 |

| Erard | 127 | (550) | 4.3 |

| Broadwood | 696 | (2,600) | 3.7 |

| Collard & Collard | 601 | 1,950 | 3.2 |

Sources: 1881 census and Ehrlich, The Piano, 144 (estimated figures in parentheses).

According to Table 1, Chappell and Erard were producing more instruments per man per year than either Broadwood or Collard, yet with a far smaller workforce. Assuming all four firms employed a similar ratio of administrative-to-piano-making staff, Broadwood and Collard were respectively 20% and 30% less efficient than Chappell.Footnote 34 For the factory staff at Broadwood and Collard to have claimed the same output per man as Chappell, their administrative (i.e. non-piano-making) staff would have had to exceed that of Chappell by 131 and 177 respectively. Such an administrative workforce would have been untenable, so the greater output per capita of the Chappell factory must be attributed to the superior efficiency (or less careful execution?) of their working practices.

Table 1 also shows that the average number of instruments made each year by these London employees was 3.9, or one instrument from the labour of each man every three months or thereabouts. The history of individual output has been discussed elsewhere. Cole calculates that Americus Backers’ workshop produced ‘about seven large pianos per year’ in the 1770s,Footnote 35 his workshop being equipped with six benches denoting (according to Clarke) the presence of six workers,Footnote 36 each making, therefore, just over one piano a year. Pole considered that by 1851 ‘about six or seven instruments [were] made in a year by an amount of labor [sic] equivalent to that of one man’,Footnote 37 a figure agreed by Ehrlich who calculated that ‘even Broadwood's elaborate division of labour achieved an annual productivity of about only seven pianos per man’.Footnote 38 Pole conceded that ‘in the larger houses where the more expensive kinds are made the proportion will be less – say about four or five to a man’, arriving at a figure approximating that of the Chappell workforce in 1881. Where only the output of a factory has been known to date, by dividing its output by 3.9 the size of its workforce may now be estimated, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Major factories for which output figures are recorded, and a calculation of their approximate workforce.

| Factory | (Estimated workforce based on per capita figure of 3.9 pianos p.a.) | Known (or estimated) output in 1880 |

|---|---|---|

| Kirkman | (230) | 900 |

| Hopkinson | (205) | 800 |

| Brinsmead | (179) | (700) |

| Allison | (154) | 600 |

| Burling & Burling | (128) | (500) |

| Challen | (128) | 500 |

| Cramer | (128) | 500 |

| Rogers | (77) | 300 |

| Challenger | (41) | 160 |

| Barratt & Robinson | (25) | 100 |

Sources: 1881 census and Ehrlich, The Piano, 144.

Calculations in Table 2 suggest that Kirkman and Hopkinson employed more than 200 men, and Brinsmead slightly fewer. Brinsmead's claim in 1874, therefore, that their works could produce 3,000 instruments a year with 300 men, had not been tested and the closest they came to achieving this figure was around 1910 when the factory made about 2,000 instruments a year.Footnote 39 Given the large output of so many purpose-built factories, it seems hardly credible that the proprietors of small workshops would seek to compete, but, paradoxically, small workshops were able to produce, per man, a number of instruments comparable to that of their larger competitors, as cheap labour and ‘an abundant supply of pre-manufactured parts available on credit’ could, ‘if carefully assembled […] result in a useful cheap product’.Footnote 40

Table 3 lists the small-scale makers to have advertised in the 1881 Post Office London Directory and to have recorded the size of their workforce in the census. A full list of the study population to have noted their workforce in the census is recorded at Appendix 1. None of the firms listed in Table 3 employed more than 25 hands, and a third employed fewer than five, indicating that small workshops akin to those of the pioneering London piano makers were still in existence in 1881, and several, like their forebears, still operated from a residential address.

Table 3. Small-scale makers in the 1881 Post Office London Directory to have indicated the size of their workforce in the census.

| Firm | Address | Men | Boys | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| James Ballingall & Sons | 38 & 40 Great College Street, Camden Town | 13 | 5 | 18 |

| Edward Wallis Bishop | 72 Belmont Street, Camden Town | 13 | 2 | 15 |

| William Bryson | 121 Cromer Street, Grays Inn Road | 2 | – | 2 |

| John Haig Campell | 68 Lupus Street, Pimlico* | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| John Crosswell | 471 New Cross Street, Deptford* | 3 | – | 3 |

| William Dunkley | 101 High Street, Clapham | 12 | – | 12 |

| Alexander Eason | 217 & 219 Kentish Town Road | 5 | – | 5 |

| Richard Edwards | 2 Seymour Street, Euston | 4 | – | 4 |

| James Hulbert & Sons | 8 Gladstone Street, Wyvil Road | 20 | 5 | 25 |

| Hunton & Crocker | 174 Carlton Road, Kentish Town | 4 | – | 4 |

| Richard Pearce | 26 Eagle Wharf Road, Hoxton | 10 | – | 10 |

| Plumb & Co | 42 High Street, Camden Town | 11 | 1 | 12 |

| James Pocock & Son | 103 Westbourne Grove, Bayswater | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Priestly & Son | 8 Edward Street, Hampstead Road, Euston | 17 | 2 | 19 |

| William Rogers | 35 Drummond Street, Euston Sq | 10 | 3 | 13 |

| Henry Schupisser | 36 High Street, Camden Town* | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Seager, Lucas & Pyne | Monsell Road, Finsbury Park* | 5 | – | 5 |

| James Stephen | 54 Queen Street, Camden Town | 3 | – | 3 |

| John Strong | 60 Seymour Street, Euston | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| Charles Venables & Co | 2 & 4 Canonbury Road, Islington | 24 | – | 24 |

Note: *Operating from a residential address.

Sources: 1881 census and Post Office London Directory 1881.

Other workshops produced a variety of supplies for the trade, and while the majority were based near the ‘old’ trade around Tottenham Court Road, nearly half operated in Camden Town, Kentish Town and Islington. The 1881 Post Office London Directory lists 58 suppliers to the trade: 11 action makers, 16 fret cutters, 2 hammer coverers, 2 hammer felters, 5 hammer rail makers, 1 ivory bleacher, 2 ivory cutters, 11 key makers, 3 pin makers and 5 small-work makers; the following are those who indicated the size of their workforce in the census:

Again, none of the firms listed in Table 4 employed more than 25 hands, and one operated from a residential address,Footnote 41 so the supply trade still offered a refuge for small business in 1881. The largest of the London supply firms were the action makers Henry Brooks & Co. at 31 Lyme Street, Camden Road, and 31–35 Cumberland Market, Regent's Park, and J. & J. Goddard (est. 1842) at 68 Tottenham Court Road. Goddard's was ‘something of a Mecca for London region piano tuners […and] it was a usual sight on Saturdays to see dozens of them arriving at the Tottenham Court Road shop in order to purchase their supplies of piano wire, tape ends, centre pins and sundry tools necessary for their routine work’.Footnote 42 A future manager at Goddard's would be the eldest surviving son of John Brinsmead, who married into the Goddard family,Footnote 43 but for the present Thomas Brinsmead and his brothers, Edgar and Sydney, were working with their father at the family factory in Grafton Road, Gospel Oak.Footnote 44 A fourth son, Horace, was promoting the firm in Australia and therefore absent from the census.Footnote 45

Table 4. Suppliers in the Post Office London Directory to have indicated the size of their workforce in the census.

| Firm | Trade | Address | Men | Boys | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joseph Nott | Action maker | 13 Kirkwood Rd, Chalk Farm Rd | 14 | 10 | 24 |

| Charles Frederick Rich | Action maker | Angler's Lane, Kentish Town | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Frederick Edwards | Key maker | 66 Southampton St, Pentonville* | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| James Dodimead | Fret cutter | 50 Tottenham Court Rd | 5 | – | 5 |

Note: *Operating from a residential address.

Sources: 1881 census and Post Office London Directory 1881.

Other figures of the Victorian piano industry at their posts in 1881 included Broadwood employee Frederick Rose, now a partner of the firm and working alongside his two sons who were foreman and clerk – all three sharing a house behind the Horseferry Road factory in Page Street. It is thanks to Frederick that we know the number of staff then working for the firm.Footnote 46 Fellow Broadwood employee and principal technician Alfred J. Hipkins was now the company's ‘musician agent’, living a short distance from the Cadby piano works in Kensington.Footnote 47 Henry Fowler Broadwood (69) was retired from the industry and working at his country estate in Surrey as a ‘Land & Funds F[a]rmer [of] 668 Acres Employing 6 Gardeners 19 Men & 4 Boys’.Footnote 48 James Hopkinson was also retired at 62, but John Brinsmead worked on at 65.Footnote 49 Charles Challen and his wife were visiting relatives in Sussex on the night the census was taken, leaving sons Charles Hollis and Frank in the family house in Oakley Square, and a third generation of the Collard family was in charge of the factory in Oval Road.Footnote 50 It is thanks to the eldest of the three brothers, William S. Collard (38), that we know the size of their workforce. Further afield, Edward Pohlman was retired at 56 in Halifax, though no doubt advising sons Fred (22) and Edward (20) on the running of the firm,Footnote 51 and in Manchester Henry Forsyth was planning the relocation of his music publishing and piano-retail business, along with 31 men and six boys, to spacious new premises at Deansgate.Footnote 52 These were just some of the luminaries noted in the census and their contribution to the industry is documented elsewhere. For the majority of the remaining workforce, however, the census may be the only surviving record of their work.

This, then, was the London piano industry in 1881, drawn largely from the Post Office London Directory and initial findings from the census. The complexity of this scene, and of the country elsewhere, is developed further by a closer study of the census.

The census and its difficulties

The census for 1881 was taken on the night of Sunday, 3 April and covered England, Scotland, Wales, the Channel Islands, the Isle of Man and the Royal Navy. A few days previously, enumeration forms were distributed to every ship and household, and the completed forms collected shortly after. Each form was intended to record the address of the property; whether or not the house was inhabited; the number of rooms occupied (if less than five); the name of every person who slept there the night before; their relationship to the head of the household; their marital status; age last birthday; gender; occupation; place of birth; and whether or not they were deaf, dumb, blind, imbecile, idiot or lunatic. The details collected on these individual forms were then sorted and copied into enumerators’ books and the original householders’ schedules destroyed. The data that remained is held at The National Archives in Kew.

The accuracy of the information gleaned by the census – and, as a consequence, the data gleaned for this study – is reliant on several key factors, all of which contribute to the veracity of the data and none of which can be assured: namely, the honesty of the individual being enumerated; the accuracy of the official copying their details into the enumerator's book; the legibility of all handwriting involved; and the accurate transcription of the books into modern electronic format. The compilers of the General Report of the 1881 census conceded that:

[…] the task is not only one of gigantic dimensions, but one in which strict and unfailing accuracy is practically unattainable. We made every effort to secure as great accuracy as was possible under the circumstances, but we are bound to state that the margin that must be allowed for error is very considerable.Footnote 53

Woollard & Allen's guide to the 1881 census confirms the complexity of errors that could accrue at every stage of the process, as details were routinely misrecorded, misspelt, mistranscribed, illegible in the original or omitted altogether.Footnote 54 Some of these errors are easily weighed, but others are problematic. Was an address written simply as ‘Durham’ intended to signify the name of the town or the county? Since the latter is the only answer correct in both instances, the county was favoured for this study. Was a ‘piano maker tuner’ someone who worked as a piano maker and a tuner, or a tuner working for a piano maker? The enumerator's sheet was checked to establish whether an ampersand had been omitted in the online transcription and, if not, they were judged to have been the latter. Enumerator sheets were also consulted to check whether piano ‘tuners’ had been mistranscribed as ‘turners’ (and vice versa), husbands accorded the occupations of their wives (and vice versa), and widows bestowed the occupation of their late husband. Martha Brown recorded herself as a ‘Piano Maker (wid)’, but was she the widow of a piano maker, or a piano maker and a widow? At 75 was she even working still? Further investigation suggested that Martha was a piano maker's widow and she was excluded from this study.Footnote 55 Other cases were resolved by studying fellow members of the household: Martha Barker became a more plausible ‘piano frame maker’ once her husband had been identified as a bricklayer's labourer.

Martha Brown, Martha Barker and the balance of the study workforce used the word ‘piano’ or ‘pianoforte’ to describe their occupation on their census form, and using these words to search the census online has ensured that only people allied to the piano trade have been included in this study. This method has necessarily excluded all those who did not use the word ‘piano’ or ‘pianoforte’, however, and many others with skills required by the industry who were possibly in its employ, such as: carvers; gilders; fret-cutters; marquetry workers; French polishers; veneer, timber and ivory suppliers; castor and candle-sconce makers, to name a few. Their skills were allied to the piano trade, but also underpinned the furniture trade, so it is impossible to know which industry they supported; they may have supported both. An added barrier to segregating the piano and furniture-industry workforce lay in their common geography. Unlike piano-action makers and gun-action makers who worked, almost without exception, in London and Birmingham respectively, the capital's piano and furniture makers inhabited the same north London suburbs, making them impossible to separate by address alone.Footnote 56 Omitting these indeterminate workers renders this study incomplete – the workforce may have been several thousand stronger – but maintains its objective integrity. Any errors that may remain embedded in the census (and any that escaped correction in my own data collection) mean the statistics produced by this study cannot pretend to absolute mathematical accuracy. They do, however, offer a highly detailed picture of the workers they expose.

Methodology and study population

A search of the England census for 1881 using the words ‘piano’ and ‘pianoforte’ revealed the records of 7,433 people connected with the instrument. A further 259 were located by introducing increasingly implausible misspellings of the two words, for example ‘piana’, ‘penoforte’ and ‘pianofofte’.Footnote 57 Disregarding spurious results such as ‘Wife of piano tuner’ or ‘Daughter of piano maker’, the combined total reduced to 7,116. Not all these records belonged to people connected with the manufacture or trade of the instrument, however, so 654 piano teachers and pianists, music sellers and setters (who only became involved with the instrument post-sale) were also discounted, excepting those who held multiple jobs where at least one involved working with the piano's mechanism or sale, e.g. ‘piano teacher & tuner’, or ‘piano dealer & music seller’: these were included. The final total came to 6,462 workers, comprising 6,221 men, 137 women and 104 children under the age of 15.Footnote 58 They are listed in full at Appendix 2, which is available online as a supplementary dataset at http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14723808.2014.986259. Census records of the contemporary American workforce (which made almost the same number of instruments in 1880, i.e. approximately 30,000) total 8,000, and this figure may indicate the potential margin of adjustment required to reflect the size of the English workforce.Footnote 59

The details of each census return were copied in full onto an Excel spreadsheet under the same headings as the source material.Footnote 60 A further 42 headings were then added to facilitate interrogation of the data, including columns noting whether the worker was retired, unemployed, hospitalized or institutionalized; the total number living at the same address; the number of family members employed in the trade; the number of resident servants and lodgers; whether any lodgers also worked in the trade; whether the census worker was the sole earner in the household; and the occupations of each fellow resident, lodger, spouse, child and sibling. Once all records had been entered and checked for errors, a further 23 spreadsheets were created to manipulate the data and create a battery of statistics. These spreadsheets covered a wide range of subjects from ‘Occupation’, ‘Location’, ‘Migration’ and ‘Nationality’ to ‘Unemployment’, ‘Retirement’, ‘Age’, ‘Women’ and ‘Employers’, and the statistics they generated are presented in the tables that follow. To avoid repetition the words ‘piano’ or ‘pianoforte’ as descriptors have been omitted. Hence, where the census records a ‘piano tuner’, ‘pianoforte maker’ or ‘piano dealer’ they appear in the tables as simply ‘tuner’, ‘maker’ or ‘dealer’. See Appendix 3 for a list of all the occupations recorded by the study population. All references to London or the capital denote the City of London and the county of Middlesex combined.

Population numbers and rates of increase

The total population of England on the night of 3 April 1881 was just under 24 million: an increase of 14% over the previous decade, and the addition, in effect, of another city with a population the size of London. This increase had swelled London by more than 40%, Surrey by more than 30%, Kent and Essex by more than a quarter, and the counties of Yorkshire, Leicestershire, Derbyshire, Lancashire and Nottinghamshire by 18–23%. Eight other counties had seen their population decline: Cornwall had lost nearly 9% of its inhabitants, Huntingdonshire, Herefordshire, Dorset, Rutland, Westmorland and Cambridgeshire progressively fewer, and Shropshire the least, at only 0.5%.Footnote 61 As will be shown, the migrations of the study workforce ran in close parallel with these national losses and gains.

The piano-industry workforce identified by the study numbered 6,462 of which 98% were men and 2% were women. A direct comparison of the 1881 workforce with that of a decade earlier is not currently feasible as the 1871 census is not electronically searchable by occupation. However, with reference to the General Report of the 1881 census, it is possible to assert that the number of musical-instrument makers in 1881 (9,249) had increased by 28% in the course of the past decade, and those who gained their livelihood by music in general had increased by 37%:Footnote 62 music making – and piano making – were employing increasing numbers of the population.

Workforce density and location

An examination of the residential addresses returned by the study population showed that 75% of the workforce lived in the capital with the remaining 25% spread thinly from Cornwall and Kent in the south to Cumberland and Northumberland in the north (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Map of England showing distribution of the study population by county. Map courtesy of the Association of British Counties.

The two most densely populated counties outside the capital (both in terms of the national population and the piano-industry workforce) were Lancashire and Yorkshire with 276 and 262 identified piano workers respectively. These two counties claimed 4% of the workforce each – more than double that of any other provincial county. The majority of counties claimed fewer than 50 piano-related workers, the most notable being Rutland and Westmorland with only one apiece: the tuner working in Rutland covering more than 100,000 acres on his ‘patch’, and his counterpart in Westmorland (who also worked as an organist) more than five times that amount. In short, only 1,569 people were identified in the piano industry outside the capital: 426 in physically making instruments, 952 in tuning them, 194 acting as dealers, and the remainder working as packers, porters, removers, repairers, managers, clerks, travellers, factors and warehousemen. Expressed another way, the capital claimed 90% of all identified makers, 46% of tuners, 38% of dealers and 75% of the workforce involved in other, supporting, aspects of the trade.

The densest congregation of workers outside London was gathered around Liverpool, where more than 100 worked in the city and its suburbs, some with possible links to the organ builders and piano retailers Rushworth & Dreaper who had premises in the centre of the town. In neighbouring Yorkshire, smaller areas of activity were to be found around Halifax, Leeds, York, Huddersfield, Kingston upon Hull and Bradford. Some of the 40 or so workers in Halifax are likely to have been associated with Pohlmann & Sons, established in the town in 1823.Footnote 63 The greatest congregation to the south of the country comprised 49 workers in the Bristol area, some involved, perhaps, with the longstanding firm of Joseph Hicks.Footnote 64 Rarely did a census return record the name of an employer, but a study of local trade directories might point to possible connections.

Assuming the occupations recorded in the census may be grouped into the four basic categories of making, tuning, dealing and ‘other’ (to include clerks, errand boys, accountants, packers, repairers and removers, etc.), Table 5 shows, by county, the number of workers involved in each category of the industry. The total figures resulting from Table 5 exceed the study workforce by 1.3% as 88 workers were involved in multiple aspects of the trade (e.g. as a ‘tuner and dealer’) and are therefore counted twice.

Table 5. Number of the study population involved in making, tuning, dealing and other aspects of the industry (by county). Decreasing order of size.

| County | Maker | Tuner | Dealer | Other | Total | Cont'd | Maker | Tuner | Dealer | Other | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| London | 3,792 | 827 | 121 | 180 | 4,919* | North'land | 3 | 12 | 5 | 3 | 23 | |

| Lancs. | 74 | 157 | 46 | 6 | 283 | Cambs. | 2 | 17 | – | 2 | 21 | |

| Yorks. | 117 | 116 | 43 | 4 | 280 | Herts. | 5 | 10 | 4 | 1 | 20 | |

| Glos. | 32 | 52 | 8 | 6 | 98 | Suffolk | 2 | 17 | 1 | – | 20 | |

| Sussex | 19 | 47 | 7 | 8 | 81 | Durham | 2 | 15 | 2 | – | 19 | |

| Devon | 23 | 40 | 7 | – | 70 | Northants | 2 | 14 | 2 | – | 18 | |

| Warwicks. | 11 | 41 | 8 | 7 | 67 | Oxon. | – | 13 | 2 | 2 | 17 | |

| Surrey | 27 | 28 | 6 | 4 | 65 | Derbyshire | 2 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 16 | |

| Essex | 33 | 21 | 1 | 1 | 56 | Wilts. | – | 15 | 1 | – | 16 | |

| Kent | 9 | 42 | 4 | – | 55 | Cumberland | – | 11 | 3 | – | 14 | |

| Cheshire | 7 | 39 | 4 | 2 | 52 | Cornwall | 1 | 8 | – | 2 | 11 | |

| Hampshire | 9 | 30 | 8 | 2 | 49 | Shropshire | 2 | 8 | – | 1 | 11 | |

| Somerset | 12 | 30 | 6 | – | 48 | Dorset | 2 | 7 | – | – | 9 | |

| Notts. | 4 | 26 | 5 | 1 | 36 | Bucks. | – | 7 | 1 | – | 8 | |

| Norfolk | 7 | 16 | 4 | 1 | 28 | Herefordshire | 1 | 5 | 1 | – | 7 | |

| Lincs. | 3 | 18 | 5 | – | 26 | Beds. | 1 | 4 | – | – | 5 | |

| Staffs. | 5 | 18 | 2 | – | 25 | Hunts. | – | 3 | – | – | 3 | |

| Berks. | 4 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 24 | Rutland | – | 1 | – | – | 1 | |

| Leics. | 1 | 16 | 5 | 2 | 24 | Westmorland | – | 1 | – | – | 1 | |

| Worcs. | 3 | 20 | – | 1 | 24 | Total | 4,217 | 1,779 | 316 | 239 | 6,551 |

Note: *Excludes one maker whose resident county was not recorded.

Source: 1881 census.

As demonstrated in Table 5, opportunities for sourcing and tuning an instrument outside the capital varied widely. Lancashire offered the widest choice of dealers with 46, but none was found in Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire, Cornwall, Dorset, Huntingdonshire, Rutland, Shropshire, Westmorland or Worcestershire. A search for general musical-instrument dealers in these counties revealed only three men working in Worcestershire.Footnote 65

Lancashire also recorded the greatest number of tuners (157), while the counties least well served with tuners were, again, Bedfordshire, Huntingdonshire, Rutland and Westmorland, each with fewer than five. Yorkshire returned the greatest number of makers outside the capital (117), but allegedly no-one was involved in piano making in Buckinghamshire, Cumberland, Huntingdonshire, Oxfordshire, Rutland, Westmorland or Wiltshire, although between them they recorded seven dealers. John Broadwood recognized a lack of rural specialists as early as 1783 when he sought to organize ‘a network of provincial […] agents, evolving from his existing client base and trade contacts’Footnote 66 to facilitate the distribution and service of his instruments, and it is possible that some of the workers recorded in the census were descended from his original contacts. Even so, and despite a greater demand for domestic pianos in 1881, the opportunities for buying and maintaining them outside the capital were arguably little better than today.

Habitation

Excluding members of the workforce who were boarding, lodging, visiting, temporarily hospitalized or institutionalized (and not, therefore, resident in their own home), the average number of residents living in households inhabited by the study population was 5.4: the same as the national average.Footnote 67 More commonly, however, the number of residents per study household was only four (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Number of residents per study household (excluding those absent from home on the night of the census).

Figure 7 shows the size of household inhabited by the study population. A small number (67) returned a single occupant, but whether they habitually lived alone is not apparent since 30% of those who declared they were living alone also declared they were married. Of those who were living alone and unmarried, male members of the workforce were ten times more likely to have been living alone than their female counterparts. The majority of the workforce lived in households accommodating between two and ten residents, with just 6% living in households of more than ten. Omitted from the chart (due to the scale) are the households with more than 16 residents. One of the largest was the Marylebone villa of an American merchant, which housed 26 inhabitants including 18 servants, one of whom (the coachman) had a son who was apprenticed to the piano trade.Footnote 68 The largest household in the study was home to 35 Italian migrants in Holborn, where the head of the house was an ‘organ and piano dealer’ and 15 of his fellow residents were street-organ players who found room to accommodate six visiting musicians.Footnote 69 Despite high levels of cohabitation, 36% of study households were supported by only one obvious income. The income and expenditure of the study population is discussed again below.

It was not until 1883 that the Cheap Trains Act introduced lower fares for commuting workmen,Footnote 70 so in 1881 many of the workforce would have minimized their commute to work by living locally. New housing stock in the northern suburbs made this increasingly possible, and some roads accommodated large numbers of workers. Belmont Street in Camden Town (site of the Chappell factory) was home to 29 workers; Bayham Street (site of George Rogers & Son) housed 30; Weedington Road (behind the Brinsmead factory) accommodated 34; and Arlington Road (site of Henry Ward's factory) returned 49 resident desk makers, finishers and fitters, journeymen, key makers, manufacturers, polishers, regulators, stringers and tuners. Those physically living on the factory premises included a ‘van man’ with his wife and son at the Chappell factory in Belmont Street (who probably acted as unofficial security guard as well), and a ‘night watchman’ at the Erard factory in Kensington.Footnote 71

Social status in terms of residential address

In 1886, the Victorian philanthropist Charles Booth began a survey of the life and labour of contemporary Londoners and examined, as he did, the working practices of several of the capital's piano manufactories.Footnote 72 Among them were the firms of Kirkman, Broadwood, Brinsmead and Challen whose completed questionnaires form part of the Charles Booth Archives held at the London School of Economics.Footnote 73 The view of the representative of the Challen factory (at that time) was that men in the trade ‘as a rule earn good wages and are able to maintain a comfortable home’, and that their wives, by and large, did not work.Footnote 74 This view of the workforce, when aligned with the Maps Descriptive of London Poverty (1898–99) that accompanied Booth's survey,Footnote 75 suggests that piano-factory staff would have lived in streets deemed ‘fairly comfortable’, whose inhabitants commanded ‘good ordinary earnings’ of perhaps 22 to 30 shillings per week.Footnote 76 Such roads on Booth's maps were shaded pink, with other streets coloured differently to indicate the greater or lesser wealth of their inhabitants: namely, yellow (upper-middle and upper classes, wealthy); red (middle class, well-to-do); purple (mixed, some comfortable others poor); light blue (poor, 18s. to 21s. a week for a moderate family); dark blue (very poor, casual, chronic want); and black (lowest class, vicious, semi-criminal).

Consulting Booth's maps with cross-reference to the London addresses of the census workforce builds a more comprehensive view of the workers’ status. Not all lived in such comfortable circumstances, though a number enjoyed greater ease and a portion considerably less. It is important to note that a survey of Booth's maps cannot deliver a wholly accurate picture of the demographics of the piano-industry workforce for two reasons: first, the maps were compiled 17 years after the 1881 census was taken and the social character of streets and neighbourhoods may have changed in the interim period; and, second, the wealth of the study household may not have been solely attributable to the earning power of the piano worker in residence. Allowing for these considerations, a study of the two sources does reveal the following. In all, 4,857 members of the London workforce (excluding workers who were institutionalized, hospitalized or imprisoned and not, therefore, living in their own homes) inhabited more than 2,100 London streets, of which more than 1,500 streets (or 73%) were identified on Booth's maps.Footnote 77Table 6 shows the number of workers to have dwelt in streets of a single colour, where everyone on the street was considered to have belonged to the same social order.

Table 6. Number (and percentage) of the study population to have lived in London streets shaded one colour only, and therefore considered to have been ‘that class’ of resident.

| Number of residents | % of study pop (3,986) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| YELLOW: | Upper-middle and Upper classes. Wealthy | 10 | 0.3 |

| RED: | Middle class. Well-to-do | 299 | 7.5 |

| PINK: | Fairly comfortable. Good ordinary earnings | 1,629 | 40.9 |

| PURPLE: | Mixed. Some comfortable others poor | 824 | 20.7 |

| LIGHT BLUE: | Poor. 18 s. to 21 s. a week for a moderate family | 166 | 4.2 |

| DARK BLUE: | Very poor, casual. Chronic want | 23 | 0.6 |

| BLACK: | Lowest class. Vicious, semi-criminal | 5 | 0.1 |

Sources: 1881 census and Charles Booth, Maps Descriptive of London Poverty.

These workers account for 74% of the total study population and their status, according to Booth, may be reasonably assured. The remaining 26% lived in streets marked with a combination of colours – such as dark blue and black, or pink and purple – indicating that the street contained a proportion of the classes represented by both colours. Which of the colours was representative of the resident piano workers cannot be known, so in these instances both colours have been recorded here. This has the effect of doubling the workforce in the streets concerned, so the figures, when added to the study findings above, over-inflate the results (as shown in Table 7):

Table 7. Total number (and percentage) of the study population to have lived in London streets shaded one or several colours.

| Number of residents | % of study pop (3,986) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| YELLOW: | Upper-middle and Upper classes. Wealthy | 36 | 0.9 |

| RED: | Middle class. Well-to-do | 995 | 25.0 |

| PINK: | Fairly comfortable. Good ordinary earnings | 2,515 | 63.1 |

| PURPLE: | Mixed. Some comfortable others poor | 1,100 | 27.6 |

| LIGHT BLUE: | Poor. 18 s. to 21 s. a week for a moderate family | 284 | 7.1 |

| DARK BLUE: | Very poor, casual. Chronic want | 61 | 1.5 |

| BLACK: | Lowest class. Vicious, semi-criminal | 67 | 1.7 |

Sources: 1881 census and Charles Booth, Maps Descriptive of London Poverty.

Neither table provides an accurate reflection of the study population. The first, while correct, records only 74% of the study population and the second, though also correct in terms of the information captured, gives a confused reading of the workers’ status as they cannot have occupied different coloured areas of the same street simultaneously. The findings may be usefully considered another way, however, by supposing that all workers who lived in a multi-coloured street are deemed to have lived in the ‘better’ portion of it; for example, all those whose street was coloured dark blue and black are considered to have been ‘very poor’ as opposed to ‘criminal’, and all those whose street was coloured pink and purple are considered to have been ‘fairly comfortable’ as opposed to ‘poor’. This would shift the spectrum to the brightest viewpoint. The resulting figures present the most optimistic analysis of the workers’ residential status. An opposite analysis (shifting the spectrum to the least favourable viewpoint) results in the most pessimistic portrayal of their status. A calculation midway between the two extremes offers a cautious view of their genuine situation. Figure 8 is based on all these calculations: the most optimistic, the most pessimistic, and the median point between the two states.

Figure 8. Number of the study workforce (whose streets were identified on Charles Booth's map) to have lived in each colour of street, based on an optimistic, median and pessimistic analysis of Booth map findings.

Consistent with the observation of the Challen factory representative, this chart confirms that the greatest number (2,066 or 52%) of the study population lived in streets whose inhabitants were considered ‘fairly comfortable’ with ‘good ordinary earnings’. A lesser number (645 or 16%) were more affluent, living in streets shaded red, whose residents were ‘middle class’ and ‘well-to-do’, and less than 1% (or 23) cohabited with the wealthy ‘upper-middle and upper classes’ in streets shaded yellow. These three categories combined (yellow, red and pink) account for nearly 70% of the study workforce. Less fortunate was the remaining third of the study population considered to have been ‘poor’, ‘very poor’ or of the ‘lowest class’. Of these, more than 950 (or 24%) fell into the ‘mixed’ purple category (some comfortable, others poor) and more than 220 (or 5.6%) were deemed ‘poor’ (light blue), earning 18 to 21 shillings per week. Another 38 (or 1%) were considered ‘very poor’ (dark blue), and 36 (or 0.9%) lived among the lowest, ‘vicious, semi-criminal’ members of society (black), although it is possible these streets were not so degenerate at the time the census was taken.

Who, then, were these workers, and was there a correlation between the work they performed and the streets in which they lived? Beginning with the five members of the workforce to have lived in streets shaded entirely black, the data in Table 8 was recorded.

Table 8. The five members of the study population to have lived in streets coloured wholly black.

| Street | Resident | Occupation | Fellow residents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Campbell Road, Islington | Henry Squire | Piano maker | Wife (governess), 2 children, servant |

| Nightingale Street, Marylebone | William Matron | Piano maker | Wife (ironer), 3 children |

| Nightingale Street, Marylebone | Albert E. Sears | Action maker | Parents, 3 siblings |

| Pascal Street, Lambeth | Charles T. Sterman | Finisher | Parents, 2 siblings |

| Slaidburn Street, Chelsea | Francis Lindley | Piano maker | Brother-in-law's family |

Sources: 1881 census and Charles Booth, Maps Descriptive of London Poverty.

Immediately, we find an irregularity. Living in one of the most depraved streets in London with his wife, children and servant was the piano maker Henry Squire,Footnote 78 whose extended Devonshire family were noted piano makers in the capital: not the sort of vicious criminal Booth might have led us to expect, nor (according to the enumerator's sheets) living among others ostensibly of that ilk. His neighbours were a boot-maker, tram conductor, postman, bricklayer, carman, coal porter and decorator: all middle-aged men with wives and children still at school. Booth's maps alone cannot explain this anomaly, but Squire's misfortunes may account for his address. In August 1858 his factory and dwelling house in Hollingsworth Street, West Holloway (a street shaded purple in Booth's map) were destroyed by fire, and within three years he was admitted to Debtors’ Prison in forma pauperis.Footnote 79 At the time of the census it is likely he was struggling to recover his position.

Residents living at the opposite end of the social scale, in ‘wealthy’ streets shaded yellow, were notably more congruent. ‘Piano forte maker master’ John Collard and his brother William lived among the upper classes in Kensington and Marylebone.Footnote 80 George John Bruzaud (‘pianoforte & harp maker’) and his two sons (who also worked for Erard) were similarly well accommodated in Holland Park Terrace, Kensington,Footnote 81 and Georgiana Kirkman (head of her family's firm) resided with the prosperous in Ladbrooke Square.Footnote 82 Proof of the pecuniary potential of the piano dealer is evidenced by Nathaniel Peach, who resided with his wife and two servants in affluent Montagu Street in Marylebone.Footnote 83 These individuals validate the analysis offered by Booth's maps but do not advance our understanding of the piano-industry workforce as it is generally recognized that prominent members of the industry accumulated wealth. It is more helpful to study the wider workforce by street and also occupation.

Figure 9 shows the numbers of the study workforce in each of the four broad categories of the industry – making, tuning, dealing and other – who were living in streets identified on Booth's maps. Again, they are based on a median calculation between a pessimistic and optimistic analysis of the data. The majority of workers in each category (except dealing) dwelt in pink streets whose residents were considered ‘fairly comfortable’. The greatest number of dealers lived in red streets, but only just: those resident in red streets only exceeded those living in pink streets by one, which is an insignificant number given that the figures used to compile the table derive from median calculations. It may be fairer to assert, therefore, that the majority of each workforce lived in conditions considered ‘fairly comfortable’ or better, but that the size of the majority differed in each category. The figures informing Figure 9 are shown in Table 9.

Figure 9. Median figures of a pessimistic and optimistic analysis of Charles Booth's residential status of the workforce involved in making, tuning, dealing and other activities.

Table 9. Median figures of a pessimistic and optimistic analysis of Charles Booth's residential status of the workforce involved in making, tuning, dealing and other activities.

| Makers | Tuners | Dealers | Other | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YELLOW: | Upper-middle and Upper classes. Wealthy | 16 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| RED: | Middle class. Well-to-do | 421 | 162 | 42 | 26 |

| PINK: | Fairly comfortable. Good ordinary earnings | 1,605 | 371 | 41 | 64 |

| PURPLE: | Mixed. Some comfortable others poor | 106 | 113 | 14 | 36 |

| LIGHT BLUE: | Poor. 18 s. to 21 s. a week for a moderate family | 198 | 11 | 2 | 11 |

| DARK BLUE: | Very poor, casual. Chronic want | 35 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 |

| BLACK: | Lowest class. Vicious, semi-criminal | 30 | 2 | – | 3 |

| % over Pink threshold | 85 | 81 | 84 | 65 |

Sources: 1881 census and Charles Booth, Maps Descriptive of London Poverty.

Table 9 shows that for those involved in making, the number living ‘over’ the pink threshold was 85%; for those involved in dealing it was 84%; for tuners 81%; and for those involved in other activities 65%.Footnote 84 Since each category of worker was found in each street colour (with the exception of the dealer, who was not found in a black street), the financial distinctions of the study households are not to be understood by this survey alone.

Unknown influences such as inheritance, lifestyle, workplace and expenditure all bore on the worker's choice of residential address. It is possible to assert, however, that even in the most pessimistic analysis of the relevant study population, 66% lived ‘above the pink threshold’, in streets considered ‘fairly comfortable’ or better. The perceived wealth of different branches of the trade is considered again below in terms of their servants and lodgers.

Age of the workforce

It should be noted that a person's age was not always recorded accurately in the census, and their year of birth could alter by several years from one census to another. Bearing this in mind, according to the 1881 census the age of the study population ranged from ten to 84, with an average age of 34. Not all were physically working on the day the census was taken (for reasons discussed below), and the two youngest – ten-year-old boys from Camden Town and Kentish Town – should, officially, have been at school as the school age in 1881 was from three to 13 years.Footnote 85 However, both these boys had an elder brother working in the industry who had probably secured their employment, and they described their work as ‘pianoforte (makers)’ and ‘pianoforte manufactory’.Footnote 86 The two youngest girls were 13 and also lived in London where they worked as a piano maker and an assistant.Footnote 87 They, too, lived with several older family members active in the trade. The remaining children under the age of 15 were all boys: over a third (35%) lived with family members in the industry. Of these 53% had a father working in the business, and 64% a brother. Eighty per cent were learning to make pianos and 15% were learning to tune them. Only one boy noted a job selling pianos: an ‘assistant pianoforte tuner and dealer’ working for his brother-in-law in Leeds.Footnote 88 It appears that many young children were subsumed into the trade by older members of the family.

The eldest member of the workforce lived with his spinster daughter in Cornwall, where he worked as a tuner, aged 84,Footnote 89 and he was not the only octogenarian working still; half a dozen others laboured on as tuners and makers, including the London piano maker William Henry Squire (80), and fellow Londoner William Seager (80), whose family made pianos and piano keys.Footnote 90 The eldest member of the female workforce was a 75-year-old widow working as a piano dealer in Plymouth, Devon.Footnote 91 The age and gender of the workforce are observed at Figure 10.

Figure 10. Study population by age and gender, including the unemployed, retired, hospitalized, and all those temporarily confined to a workhouse or institution.

The majority of the workforce was aged between 15 and 60, with less than 10% younger than 15 or older than 60. As shown by the peak in the chart at Figure 10, those aged between 15 and 29 accounted for nearly half (or 44%) of the total workforce, but their numbers may not be a direct indication of their recruitment value to the industry. Older members of the workforce were greatly valued for their experience, and the employment of younger members of the workforce was not necessarily at the expense of their elders. The value of ageing members of the workforce is discussed again below.

Of those who recorded their status as apprentice (136 in total), most were aged 11 to 20, but 3% were adults. These included the 25-year-old son of an army pensioner living in Hampstead who may have been encouraged by (and apprenticed to) a piano maker living separately at the same address,Footnote 92 and the 29-year-old son of a mechanical engineer in Halifax who may have been attracted to the complexity of the instrument's mechanism.Footnote 93 The eldest of the mature apprentices were two married women studying their husband's profession, one as a ‘pupil tuner’ (aged 37) and the other (aged 42) as a ‘piano maker apprentice’.Footnote 94 Male factory workers may have considered female employment an affront to their expertise and a threat to their livelihood, but sole practitioners and family workshops were pleased to recruit cheap labour.

Condition as to marriage

More than half the study workforce (60%) was married or widowed at the time the census was taken: 62% of the male workforce and 52% of the female workforce. These figures indicate that men working in the piano industry were, relatively, 20% more likely to have been married than their female counterparts. From a male perspective, then, remuneration in the piano industry was sufficient to maintain a wife and family, and from a female perspective, the industry was as likely to recruit single women as their married counterparts. This latter fact is reflected in the occupation most performed by women – that of piano-silk work – wherein half the female workforce was either wife or widow, and the other half was neither.Footnote 95

Female as compared with male occupations

The female study workforce performed a variety of practical and managerial roles ranging from apprentice maker, to tuner, to proprietor of one of the largest piano-making firms in London (Table 10).Footnote 96 In total, they recorded more than 40 different job titles which are listed in full at Appendix 4. The following is a summary of their employment in assorted branches of the trade.

Table 10. Summary of female occupations (by category and size). Decreasing order.

| Female occupation | Total | Cont'd | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silk work | 35 | Fitting and finishing | 3 | |

| Dealing | 30 | Casework | 3 | |

| Making (unspecified) | 26 | Office work | 2 | |

| Tuning | 20 | Warehouse work | 2 | |

| Key making | 8 | Part making | 1 | |

| Assistant/apprentice | 4 | Stringing | 1 | |

| Management | 4 | Total | 139 |

Source: 1881 census.

The greatest number of women occupied in a single line of work were those employed in piano-silk work (35 in total), and in 1881 women enjoyed a near monopoly in this line of work.Footnote 97 With the exception of two women working in the north of England,Footnote 98 all the silk workers identified in the study lived near the centre of the industry in London. The General Report of the 1881 census recorded that ‘Silk, silk goods [and their] manufacture’ was one of 44 areas of work in which women outnumbered men,Footnote 99 and, certainly, the female silk workers recorded in the census outnumbered their male counterparts by 35 to 1. Women enjoyed long years of employment in this line of work and their ages recorded in the census ranged from 17 to 74. Piano dealing appears to have been another branch of employment suited to women with 22% of the female workforce working as dealers as opposed to 4.5% of the male. The number of women involved in making instruments (including piano silkers) was 81 (or 58% of their total), and those involved in tuning them one quarter of that amount (20 or 14%). The remaining 2% of the female workforce was employed as managers, partners, cashiers, clerks and warehouse workers. Given that women accounted for 30% of the national workforce in 1881, those in the piano industry were notably under-represented at only 2% of the workforce total.Footnote 100

The employment of women in key making, which was ‘mainly joinery work done by men and boys’,Footnote 101 offered women and girls a variety of simple tasks such as selecting ivory key tops to ensure that individual keyboards were of uniform colour and grain, and gluing ebony or stained wood onto keys intended as sharps. Eight women reported their employment in this line of work but undoubtedly there were more. It is also likely there were more women making component parts of the piano's action than the single female ‘part maker’ recorded in the study, especially given the future recognition of female proficiency in the skill.Footnote 102 Surprisingly, no women were identified as piano polishers although more than 3,000 female French polishers were returned in the census at large. The earliest discovered reference to female French polishers in the piano industry dates to their employment at Broadwood in 1916.Footnote 103 Reflecting the national pattern, a quarter of the female workforce was employed in the country and the remainder in the metropolis.

Makers

Table 11 lists the total number of the study population to have recorded their work in various aspects of making pianos. The number of piano makers recorded in the census may be expressed in three ways. Firstly, as the total number of workers who described their occupation as ‘piano maker’ on their census return, of which there were 2,630, as shown in the first line in Table 11. This figure is deficient, however, in that it disregards 1,588 piano makers who described their work in greater detail, e.g. ‘action maker’, ‘back maker’ or ‘leg turner’. The total number of people identified in piano making is therefore expressed more accurately as the sum of these two figures, or 4,218. A third expression of the workforce presents a different total and records the sum of people working in each piano-making activity. This total is greater than the second because several workers recorded multiple manufacturing occupations (e.g. ‘finisher & turner’ or ‘maker & desk maker’) and are therefore counted twice, raising the total number for this calculation of the workforce to 4,231. This last method of calculating the workforce provides the basis for the following table. A full list of piano-making occupations recorded in the census appears at Appendix 5. The numbers involved in core piano-making activities are summarized here as follows.

Table 11. Number of the study population recorded in core piano-making activities.

| Occupation | Total | Men | Women | Cont'd | Total | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Piano maker’ | 2,630 | 2,612 | 18 | Silkwork | 36 | 1 | 35 |

| Fitting and finishing | 427 | 424 | 3 | Miscellaneous | 35 | 35 | – |

| Misc making | 252 | 250 | 2 | Polishing | 21 | 21 | – |

| Key making | 219 | 211 | 8 | Factory work | 25 | 25 | – |

| Casework | 166 | 165 | 1 | Machine operating | 17 | 17 | – |

| Apprentices and assistants | 124 | 114 | 10 | Part making | 16 | 15 | 1 |

| Action work | 107 | 107 | – | Foremen | 11 | 11 | – |

| Strings and stringing | 51 | 50 | 1 | Smithwork | 10 | 10 | – |

| Back making | 41 | 39 | 2 | Business/Partner | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Hammer work | 39 | 39 | – | Total | 4,231 | 4,148 | 83 |

Source: 1881 census.

As shown in Table 11, the total number of workers recorded in each activity is diluted by the fact that so many of the workforce returned their occupation as simply ‘piano maker’. This generalization frustrates an exact calculation of all those involved in each activity and only allows a broad conjecture that perhaps those involved in ‘fitting and finishing’ had greater pride in their piano-making skills than those working as factory labourers or part makers, and were inclined to record the fact. Messrs Broadwood recorded the precise nature of their employees’ work in 1851 when they listed 42 separate jobs pertaining to the manufacture of their instruments.Footnote 104 Their list reflected the Broadwood factory process of the time, but the census shows the diversity of roles performed elsewhere, with as many as 125 different job titles identified in the piano's manufacture. Among the more unusual were ‘carver’, ‘cleaner up’, ‘engraver’, ‘gilder’, ‘gluer’, ‘hinge dresser’,Footnote 105 ‘moulding maker’, ‘pin maker’, ‘screw cutter’, ‘sharp maker’, ‘smelt worker’ and ‘timber marker’: all indicators of the acute division of labour that still existed in the English piano industry even 30 years after Broadwood published their list, and piano cases in America were being polished by machine.Footnote 106 None of the study workforce recorded the use of a machine to polish cases (in fact, very few recorded working with machinery), but the census notes several engine drivers or machinists and one ‘piano puncher for machine’, this latter job suggestive of creating piano rolls for pneumatic player pianos via a keyboard-operated punch machine – a relatively modern innovation in 1881.Footnote 107 For the most part the manufacturing jobs recorded in the census were recognisably traditional.

As shown earlier, in Table 5, the majority of piano makers were based in London with Lancashire and Yorkshire attracting the greatest density outside the capital. The most northerly were three men based in Northumberland who may have had ties with the Scottish trade,Footnote 108 and in the south was a 68-year-old widow employing three men and a boy in Dorset.Footnote 109 Only seven workers combined piano making with unrelated jobs and these were a ‘maker & stationer, ‘oilman & key maker’, ‘maker & tobacconist, ‘tea dealer & silker’, ‘finisher & insurance agent’, ‘picture dealer & maker’ and a ‘finisher & grocer’ to be discussed again below.Footnote 110

Tuners

According to the General Report of the census, seven of the piano tuners enumerated in 1881 were ‘afflicted by blindness’ (Figure 11).Footnote 111 The tuning master for the Royal Normal College of the Blind that year was John Young and he appears in the census, aged 38, living with his wife and six children in Lewisham.Footnote 112 The college, which had been established nearly a decade earlier in three small houses near Crystal Palace, was now based in larger premises in Upper Norwood, South London, and it is likely some of the seven blind piano tuners were among its former pupils.Footnote 113 Piano tuners accounted for 1,779 members of the study workforce and Table 12 records their distribution.

Figure 11. Tuning students at the Royal Normal College of the Blind, Upper Norwood, undated.

Table 12. Location of tuners (by county). Decreasing order.

| County | Total | Men | Women | Cont'd | Total | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| London | 827 | 817 | 10 | Leicestershire | 16 | 16 | – |

| Lancashire | 157 | 156 | 1 | Norfolk | 16 | 16 | – |

| Yorkshire | 116 | 116 | 3 | Durham | 15 | 15 | – |

| Gloucestershire | 52 | 51 | 1 | Wiltshire | 15 | 15 | – |

| Sussex | 47 | 47 | – | Northants | 14 | 14 | – |

| Kent | 42 | 42 | – | Oxon. | 13 | 13 | – |

| Warwickshire | 41 | 40 | 1 | Northumberland | 12 | 12 | – |

| Devon | 40 | 39 | 1 | Cumberland | 11 | 11 | – |

| Cheshire | 39 | 39 | – | Derbyshire | 11 | 11 | – |

| Hampshire | 30 | 30 | – | Hertfordshire | 10 | 10 | – |

| Somerset | 30 | 29 | 1 | Cornwall | 8 | 8 | – |

| Surrey | 28 | 28 | – | Shropshire | 8 | 8 | – |

| Nottinghamshire | 26 | 26 | – | Buckinghamshire | 7 | 7 | – |

| Essex | 21 | 21 | – | Dorset | 7 | 7 | – |

| Worcestershire | 20 | 20 | – | Herefordshire | 5 | 5 | – |

| Lincolnshire | 18 | 18 | – | Bedfordshire | 4 | 4 | – |

| Staffs | 18 | 16 | 2 | Huntingdonshire | 3 | 3 | – |

| Cambridgeshire | 17 | 17 | – | Rutland | 1 | 1 | – |

| Suffolk | 17 | 17 | – | Westmorland | 1 | 1 | – |

| Berkshire | 16 | 16 | – | Total | 1,779 | 1,759 | 20 |

| Outside London | 952 | 942 | 10 |

Source: 1881 census.

As with the study population of makers, the greatest number of tuners outside London was gathered in Lancashire and Yorkshire, with the remainder spread unevenly across the country, but with every county claiming at least one. A significant number of the 952 tuners working outside London (197, or 21%) – including the solitary tuner based in Rutland – hailed from the capital, but whether these London tuners were already qualified when they moved to the provinces is not apparent: they may have moved with their parents as children. Of 197 London-born tuners working outside the capital, 29 (or 15%) were found in Lancashire, 20 (or 10%) were found in Sussex, and 15 (or 8%) were found in Yorkshire, with the remaining 67% inhabiting every provincial county except Dorset, Huntingdonshire and Westmorland, almost as though they had been sent from the capital to establish a provincial network. And to some extent this may have been the case.

By 1886 Broadwood was considered to have had a ‘monopoly of provincial tunings’ generating a sum approaching £12,000 a year.Footnote 114 Their tuners would have been highly skilled employees (or former employees) of the firm – or perhaps credible tuners trained elsewhere – who were prepared to commute or relocate to areas outside the capital. Tuners born in the provinces comprised half the nation's total, and may not have been so highly skilled, having inequitable access to recognized apprenticeships. This may explain why 3% of tuners born in the provinces combined tuning with paradoxically unrelated jobs, such as baker, basket maker, draper, grocer, haberdasher, insurance agent, lay clerk, printer, refreshment-house keeper, soldier, surveyor, tea dealer, undertaker and watch repairer. Even so, the majority gave priority to their status as a piano tuner on their census return (e.g. ‘piano tuner & basket maker’, and not vice versa), suggesting either that they considered tuning to be their primary occupation or that it generated the greater income. In contrast, only three provincially born piano makers (or 0.1%) reported holding an unrelated secondary job: a ‘finisher & insurance agent’ in Sussex, a ‘picture dealer & maker’ in Lancashire, and a ‘tea dealer & silker’ in Yorkshire.Footnote 115 This discrepancy between the number of tuners and makers involved in unrelated secondary occupations suggests two causal factors. Either there was more work for piano makers (leaving no time for a second job) or their work was better paid (negating the need for a second job); or, conversely, there was less work for piano tuners (making a second job a necessity) or it was less well paid (again, making a second job a necessity). Independent rural piano tuners could earn 10 s 6d per instrument in 1770Footnote 116 (equating to about £33 today):Footnote 117 the same amount as recommended for an experienced London tuner nearly a century later in 1854 (equating to approximately £30 today).Footnote 118 As late as 1947 the Piano Tuners’ Association reported that the standard price of tuning an upright piano could be ‘as much as’ 10 s 6d in some parts of the country (equating to just £13 today).Footnote 119 These figures reflect not only the value attributed to piano tuning in 1881, but the decline in its perceived value to the public – and even to the Piano Tuners’ Association itself – in later years.Footnote 120 In 1881, however, independent rural tuners could earn a reasonable income provided they had sufficient customers. Among the tuners recorded in Lancashire were the wife of a ‘Ship scraper builder’ working in Everton, and the wife of tripe dresser working in Kingston upon Hull.Footnote 121 A curious occupation recorded in Wisbech in Cambridgeshire was that of a 19-year-old boy working as a ‘Striker for [a] W[ounded?] tuner’.Footnote 122

Dealers

A total of 316 members of the workforce identified themselves as piano dealers, merchants or sellers, among them 285 men and 31 women. The largest concentration was based in London (38%), with the remaining 195 distributed unevenly around the provinces, as shown in the following table.

Table 13 shows that dealers in Lancashire and Yorkshire would have been able to stock a selection of instruments made locally alongside those introduced from London and abroad as they had at least 191 makers in their midst and a predominance of piano making activity outside the capital. So, too, might dealers in Gloucestershire, albeit with perhaps a smaller choice of instruments, having only 32 local makers in their midst, 19 based in Bristol.Footnote 123 Dealers in a dozen other counties, however, were at least as numerous as their piano-making counterparts, making it unlikely that they stocked much local product, if any. Even so, with an estimated annual production of 30,000 to 35,000 pianos made elsewhere in the country, and a mounting supply of fashionable German imports,Footnote 124 dealers were able to earn a profitable living. Nearly half the dealers identified in the census employed a servant (46%) and some as many as four. The subject of servants is discussed again below.

Table 13. Location of dealers (by county). Decreasing order.

| County | Total | Men | Women | Cont'd | Total | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| London | 121 | 102 | 19 | Derbyshire | 2 | 2 | – |

| Lancashire | 46 | 45 | 1 | Durham | 2 | 2 | – |

| Yorkshire | 43 | 39 | 4 | Northants. | 2 | 2 | – |

| Gloucestershire | 8 | 7 | 1 | Oxon. | 2 | 2 | – |

| Hampshire | 8 | 7 | 1 | Staffordshire | 2 | 2 | – |

| Warwickshire | 8 | 7 | 1 | Buckinghamshire | 1 | – | 1 |

| Devon | 7 | 6 | 1 | Essex | 1 | 1 | – |

| Sussex | 7 | 7 | – | Herefordshire | 1 | 1 | – |

| Somerset | 6 | 6 | – | Suffolk | 1 | 1 | – |

| Surrey | 6 | 5 | 1 | Wiltshire | 1 | 1 | – |

| Leicestershire | 5 | 5 | – | Bedfordshire | – | – | – |

| Lincolnshire | 5 | 5 | – | Cambridgeshire | – | – | – |

| Northumberland | 5 | 5 | – | Cornwall | – | – | – |

| Nottinghamshire | 5 | 4 | 1 | Dorset | – | – | – |

| Cheshire | 4 | 4 | – | Huntingdonshire | – | – | – |

| Hertfordshire | 4 | 4 | – | Rutland | – | – | – |

| Kent | 4 | 4 | – | Shropshire | – | – | – |

| Norfolk | 4 | 4 | – | Westmorland | – | – | – |

| Cumberland | 3 | 3 | – | Worcestershire | – | – | – |

| Berkshire | 2 | 2 | – | Total | 316 | 285 | 31 |

Source: 1881 census.

Other workers in the industry

In addition to all those making, tuning and selling pianos, 239 workers were identified in a variety of supporting roles. These ‘other’ workers were engaged as office clerks, cashiers and managers; factors, importers and agents; packers, porters and removal men; repairers; a fireman at a piano steam saw mill in Soho, and a factory night watchman at Erard's piano factory in Kensington. Their statistics are shown in Table 14.

Table 14. Number of the study population recorded in ‘other’ activities. Decreasing order.

| Occupation | Total | Men | Women | Cont'd | Total | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porters | 90 | 90 | – | Managers | 12 | 12 | – |

| Office workers | 45 | 43 | 2 | Packers | 11 | 11 | – |

| Repairers | 23 | 23 | – | Misc | 9 | 7 | 2 |

| Removers and drivers | 21 | 21 | – | Factors and importers | 7 | 7 | – |

| Warehouse workers | 16 | 15 | 1 | Errand boys and messengers | 5 | 5 | – |

| Total | 239 | 234 | 5 |

Source: 1881 census.

Unemployed (including the sick, retired and imprisoned)

Allowing for all those incapacitated for work by physical defects and not referring to the piano industry per se, the General Report of the census considered that ‘the really idle proportion of the community would probably prove to be but very small’.Footnote 125 Certainly, the number of piano workers idle through unemployment on the night of the census amounted to only 0.9% of the workforce (as shown in Table 15) and it is likely none was idle through choice. The same was no doubt true of the 15 workers hospitalized or recovering in a convalescent home, the 18 confined to a lunatic asylum, the 5 in unidentified institutions, and the 21 reduced to living in a workhouse. The four workers serving a prison sentence may have preferred to have been at work as well.

Table 15. Occupation and status of the unemployed.

| Asylum | Former | Hospital | Institution | Lunatic | Prisoner | Retired | Unemployed | Workhouse | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Action maker | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Book keeper | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Case fitter | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Case maker | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||||||

| Dealer | 1 | 3 | 4 | |||||||

| Factory worker | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Finisher | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||||

| Fitter up | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Hammer coverer | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Key maker | 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| Maker | 12 | 2 | 11 | 3 | 33 | 35 | 14 | 110 | ||

| Manufacturer | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | ||||||

| Marker off | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Part maker | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Porter | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Regulator | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Silker | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Tool and key maker | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Tuner | 1 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 28 | |||

| Total | 2 | 2 | 15 | 3 | 18 | 4 | 44 | 57 | 21 | 166 |

Note: All male except the silk worker.

Source: 1881 census.