Introduction

A major impediment to our understanding of Henry Purcell the man is the dearth of documentation relating to almost every aspect of his personal life. Even basic elements of his curriculum vitae, such as the precise date and place of his baptism and marriage, are lacking. Documents of an official nature in The National Archives at Kew in London and in the Muniment Room of Westminster Abbey contain information about his various appointments and the salaries he earned as a court and church musician in and around Whitehall from 1673 till his death in 1695, but the picture they paint of him is necessarily monochrome, two-dimensional and unrevealing. In the preface to the second edition of Franklin B. Zimmerman's biography of the composer, the author bemoaned the fact that ‘[w]ith Henry Purcell, finding the inner man, getting even a fleeting glimpse of his personality[,] is very difficult indeed’.Footnote 1 Little has changed since then; leading authorities on the composer's life and work continue to express their frustration at the lamentable survival rate of primary-source material from which to construct his biography, with one of them going so far as to exclaim: ‘Such is our state of knowledge of the personal aspects of his life that his laundry bills would constitute a major scholarly find’.Footnote 2 Faced with this paucity of verifiable evidence, researchers in the field of Purcell studies will no doubt welcome the author's discovery of documents relating to the composer among the legal records held by The National Archives, and here transcribed and translated for the first time. The two cases that have come to light involve Purcell and members of his extended family – one dating from his lifetime, the other brought posthumously. These exceedingly rare documents supplement our meagre knowledge of his familial relations and introduce some hard evidence into an area that has hitherto been dominated by testimony of an anecdotal kind, such as the famous tale, first disseminated by Hawkins, which perpetuated gossip about possible friction in the Purcells’ marriage.Footnote 3 These new archival finds are the only examples of litigation involving the composer that have so far been identified. They are of interest not just for the light they shed on the dynamics of his family life; they also add to speculation about the whereabouts of the Purcells in 1691–3, on which subject we have no information whatsoever, and open up fresh avenues of enquiry regarding their social interaction with the exalted world of aristocratic patronage at precisely that moment when Henry was forging a new career as a composer for the theatre. They also afford an insight into the state of Purcell's finances at the time, and even perhaps a window on his character.

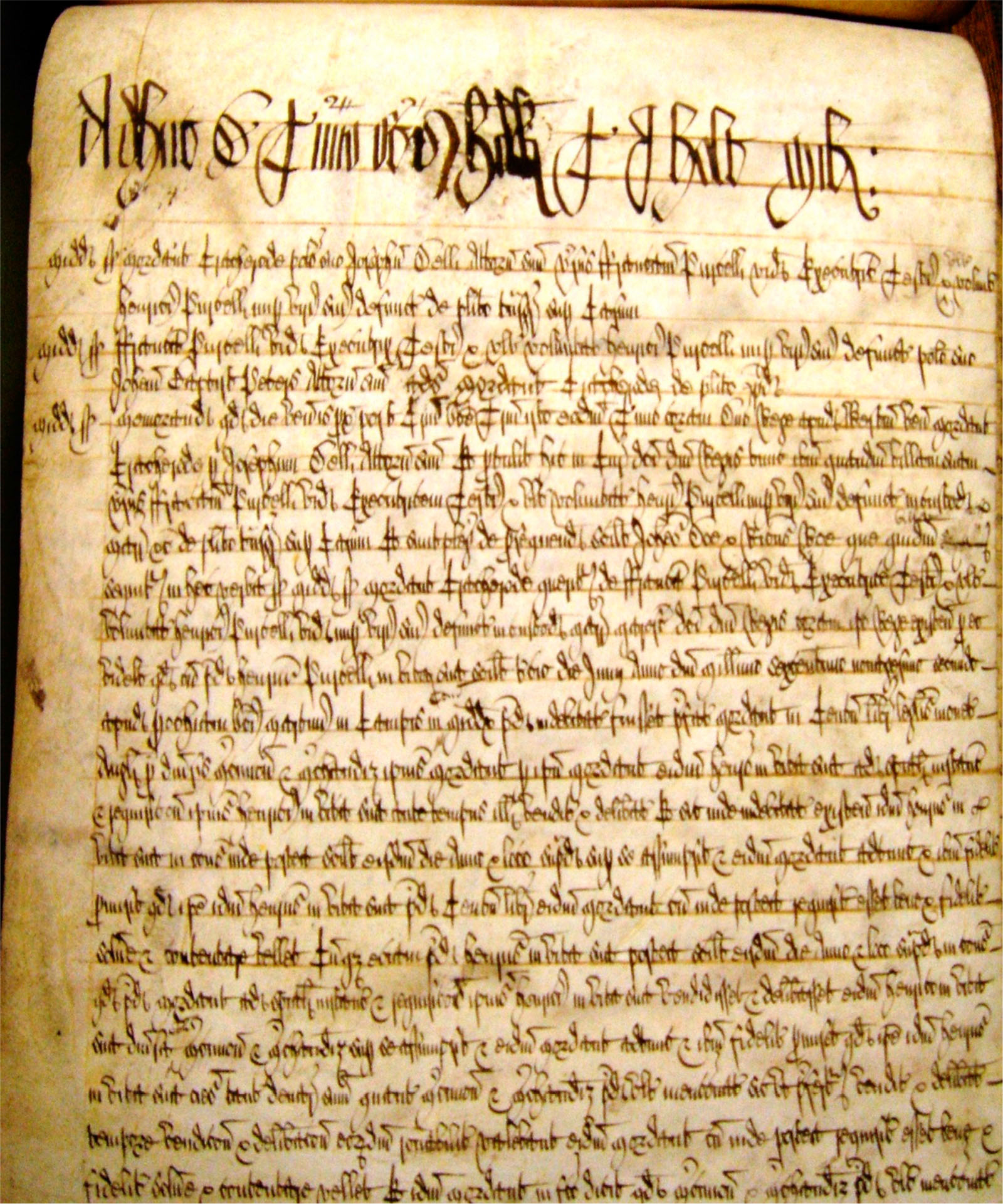

Figure 1. Opening of Cracherode v. Purcell (The National Archives of Great Britain: KB27/2130, rot. ccccli).

One can easily appreciate why this new material has lain undetected for so long. Both cases were heard in the Court of King's Bench, whose complex and voluminous records present a Herculean challenge to even the most determined researcher.Footnote 4 Before 1733, except for a brief period during the Interregnum (1649–60), the formal proceedings of England's common-law courts (King's Bench, Common Pleas and the common-law side of the Exchequer) were written in heavily abbreviated Latin and in a distinctive legal script (‘court hand’) that can be difficult for the uninitiated to decipher.Footnote 5 In marked contrast with the wealth of information to be found in the records of the equity courts (Chancery, and the equity side of the Exchequer), common-law litigation often yields data that is formulaic in the extreme and devoid of specific detail. So generalized is the language of the plea rolls that it is often impossible to relate the few bald facts that are given to a particular context; consequently, a document can have such wide applicability that its significance is at times susceptible to more than one reading, as we shall discover when we come to consider the first case. Furthermore, common-law discourse is technically abstruse and laced with legal fictions that have the potential to confuse and even mislead the unwary; court procedure in all but the most straightforward cases can be convoluted; and the pleading process is at times arcane and repetitive, especially when the parties resort to the use of alternative pleading, that is, the practice of stating in separate counts multiple versions of the same claim. Add to this the physical nature of the plea rolls themselves, which are difficult to handle on account of their size and weight, and one can perhaps understand why musicologists and scholars from other disciplines have left the records of this fundamental branch of English law largely unexplored. Such neglect, however, has delayed the collection and dissemination of new information that is occasionally of the first importance. The two case studies that form the basis of the present article are discussed from roughly similar perspectives: a biographical sketch of Purcell's legal adversary in each action is followed by an examination of the lawsuit and its implications, and an attempt to highlight its broader significance for other research in the field. Factual duplication with information already in the public domain has been kept to a minimum consistent with clarity of exposition and the placement of the new material in context. My transcription and translation of the litigation have been appended to the main text, as much to celebrate the discovery of these unique documents as to enable the reader to check that my interpretation of them is well grounded.Footnote 6

Amy Howlett: sister-in-law and defendant

Purcell's legal opponent in the first case was Amy Howlett (née Peters), the sister of Henry's wife Frances. Before the publication of Maureen Duffy's research into the Purcell family circle we knew very little about her, other than the fact that she acted as one of the witnesses to Frances's nuncupative will on 7 February 1706.Footnote 7 Amy and Frances, with their sister Mary and brother John Baptist, were the children of a Flemish immigrant John Baptist Pieters and his wife Amy. When the family arrived in London in the early 1660s, the father, who had been christened a Catholic in his native Ghent, declared himself a conforming member of the Church of England, though these newly acquired Protestant affiliations were doubtless for the purposes of denization only. The Peters settled in Thames Street, and an inventory of the contents of their house taken on the death of John Baptist senior in 1675 suggests that they had substantial means.Footnote 8

The first record we have of young Amy Peters dates from 3 April 1678, when she and John Howlett applied for a common marriage licence. Common licences merely dispensed with the requirement to call the banns on three successive Sundays before the wedding in the church where a couple planned to marry. As part of the application process, John had to submit a sworn statement (or ‘allegation’) that there was no impediment to the marriage taking place. According to this informative document Howlett was a bachelor aged about 24 at the time, who earned his living as a soapmaker in the vicinity of All Hallows the Great, London. Amy, described as a spinster from the neighbouring parish of All Hallows the Less, required her widowed mother's consent to the match because she was then only about 20 years old. This would place Amy's date of birth around 1658.Footnote 9

John was clearly something of a catch, for soapmaking was one of London's most lucrative trades.Footnote 10 He was the second son of Thomas Howlett senior, a wealthy leatherseller and soapboiler with premises conveniently close to the river in Thames Street. Under the terms of his father's will, dated 16 July 1676, John had received £1,200 and ‘Two Messuages or Tenements situat in the said Parish of Alhallowes the great now in the occupacion of Richard Marshall and Henry Higgins’.Footnote 11 Initially, and for a brief period only, John availed himself of a clause in his father's will that entitled him, once married, ‘to have house roome and accomodacion’ rent-free in the Howlett family home, even though that property had been bequeathed to his elder brother Thomas. The 1678 poll-tax record for the first precinct of the city's Dowgate ward, where the dwelling was situated, lists all those living there at the time, including ‘John Howlet & Amy his wife’, but the fact that their names are struck through indicates that the couple moved out after the assessment was drawn up and before the tax was collected.Footnote 12 They did not travel far, however, for later in the document ‘John Howlit & wif’ appear under the fifth precinct of the same ward as members of the household of Amy's mother, ‘Amy peaters’. Both she and Thomas Howlett lived in houses with an assessed rental value of £30 per annum, on which they paid ten shillings tax. If rent levels are taken as a proxy measure of affluence, then both households were comfortably well off compared to most of their neighbours.

It was not long before the Howletts were back in All Hallows the Great where they probably moved into the tenement vacated by Richard Marshall, for their first born, John, was baptized in the parish church on 16 April 1679. Towards the end of May 1680 a second child, Frances, was born in Richmond, Surrey, where the couple appear to have had family connections. That they also enjoyed some social standing in the local community is apparent from the honorific titles given to them in the entry recording the baby's baptism in the Richmond parish registers:

‘ffrances the daughter of Mr John Howlett & Mrs Amy his wife baptized June 1'Footnote 13

Two more daughters, Amy and Mary, were baptized back in All Hallows on 11 August 1681 and 16 November 1682 respectively.Footnote 14 Tragically, however, only one of the Howlett children was to survive beyond infancy, for Frances and Amy were buried at All Hallows on 12 October 1680 and 7 October 1681 respectively. Worse was yet to come for Amy and the family; her husband died at the beginning of February 1684, and their only son followed his father to the grave some two weeks later.Footnote 15 John Howlett's recently discovered will, dated 18 December 1683, makes interesting reading. In it he confirmed arrangements previously made for the disposition and conveyance of the two tenements that his father had left him in All Hallows the Great. He does not elaborate upon the nature of these provisions, but presumably the messuages were placed in trust for the support of his young family. Also, ‘for and towards a ffurther maintenance of my dear and Loving wife Amy Howlett’, he bequeathed to her ‘the One Third parte of all my personall Estate either goods and Chattells of what nature and kind soever’, and left similar legacies to each of his two children.Footnote 16 Furthermore, he stipulated that, should any of his children die before attaining their majority, then the dead child's portion was to be divided between the survivor and Amy; she therefore received not only her widow's third, but also half of John junior's portion when he died in the following February. As the children's guardian during her widowhood, Amy was to receive ‘the Interest and profitt’ of their portions ‘for and towards their maintenance and Education’. Howlett bequeathed to her ‘all her Jewells and Wareing Apparrell’ and appointed her his executrix; to assist in the performance of these duties he nominated two trustees, one of whom was Amy's brother, John Baptist Peters junior, who was training as a lawyer.

In apportioning his patrimony as he did Howlett appears to have provided well for his family, with Amy in effect inheriting one half of his wealth and a controlling interest in the other. Yet it appears that within seven years of her husband's death, she was financially embarrassed enough to have to ask Purcell for a loan. This dip in her fortunes is difficult to explain without more evidence, but it is probably attributable to a number of factors working in combination. Doubtless the life of a single parent bringing up a young child was not an easy one, and Amy, accustomed to the status of a well-to-do merchant's wife and a standard of living that went with it, may have had difficulty adjusting to the economic realities of widowhood. There is also evidence to suggest that in the 1690s the soapmaking industry, with which she may still have had connections, was experiencing something of a downturn; around the middle of that decade the City's soapmakers petitioned Parliament in an attempt to stop further taxation of their imported raw materials, claiming that ‘since the present War with France [1689],…a great Duty was laid upon the Ingredients of which Soap is made,…by reason whereof,…the Commodities are so dear, that the Trade of Soap is much decayed in London’.Footnote 17 Although we cannot be certain of the circumstances under which Purcell agreed to the loan, one thing seems clear; by the early 1690s money was in short supply in the Howlett household.

Purcell v. Howlett

On Friday 12 June 1691 (the first day of Trinity term) Henry began bill proceedings against Amy in King's Bench.Footnote 18 As the action was founded on a writ of debt, the claim had to be made in respect of a fixed sum of money or a fixed quantity of fungible goods. In this case the ‘sum certain’ was £40 which, according to Purcell's statement of claim or ‘declaration’, Amy had borrowed from him in the parish of St Mary-le-Bow, Cheapside, on the previous 20 May. He further alleged that since that date he had repeatedly pressed her for repayment, but to no avail, and was now claiming £100 in costs and damages. When the matter came before the court on 27 June following, Amy's attorney, who unsurprisingly was John Baptist Peters, admitted that she had no ground to litigate, and as a consequence of this capitulation it was determined that Purcell should recover the £40 he had lent her, as well as £2 3s 4d in costs.

On a superficial level, the facts of the case suggest that Purcell behaved quite abominably towards Amy. To lend £40 to one's widowed sister-in-law and then three weeks later threaten her with damages of £100 if the debt is not repaid, is the stuff of dysfunctional family ‘soap operas’. Was Purcell really the unscrupulous, avaricious money-lender that he appears to have been from the face of the record?

It is important not to suppose that, because Purcell sued Amy at common law, there was necessarily any animosity between them. He could just as easily have asked her to sign a promissory note for the money, i.e. a written instrument that documents a loan transaction between one party and another, and which sets out the terms and conditions for its repayment. However, Purcell clearly wanted better security for his money than mere parol promises backed up by a note of hand, and his chosen method of achieving that end was the cognovit actionem – ‘she has acknowledged the action’ – which confession is recorded in the margin of the plea roll, along with the date on which it was made. A cognovit was a written acknowledgement by the defendant in a civil case before the court, usually of debt, that he/she had no available defence because the opponent's cause was just and right. To save expense the defendant might confess the action instead of entering a plea, and suffer judgment to be entered against him/her without trial. However, the offer of a cognovit was usually conditional upon the defendant being allowed a specified period of time to settle the debt, or any agreed damages, and costs. If he/she failed to comply with the terms on which time was given, the plaintiff's attorney could obtain judgment and seek writs of execution for the sums due. The cognovit was therefore a form of promissory note that gave to the note-holder a formidable collection mechanism, permitting him to obtain a court judgment against the borrower without having to go to trial if the conditions of the note were breached. That cognovits were a popular and highly effective means of securing a loan may be seen from the other cases on the same rotulus as Purcell v. Howlett.Footnote 19

Forty pounds was no trifling sum, and the steps taken by Purcell to memorialize the transaction by having it engrossed among the proceedings of a court of record – in fact, the highest common-law court in the land – tell us something about how much it meant to him.Footnote 20 Indeed, from what we know of the composer's personal and financial affairs in 1691, it seems surprising that he could afford to lend the money at all. For one thing, he had a young family to support: the Purcells' first daughter, Frances, was a mere three-year-old at the time, and Edward, their youngest and only surviving son, had been baptized in Westminster Abbey in September 1689. Furthermore, in May 1690 Purcell had lost his position as harpsichordist in the Private Music along with an annual salary of £40, one of a number of musicians to fall victim to a scaling back of resources in the royal household.Footnote 21 It was largely this retrenchment at court that prompted him to turn to composing for the London stage, though even that form of employment, rewarding as it no doubt was, could not guarantee a regular income. Ironically, Purcell's financial situation may have been exacerbated by the success that attended his first large-scale dramatick opera, The Prophetess, or the History of Dioclesian, which received its sumptuous première at Dorset Garden Theatre in late May or early June 1690, and instantly established his celebrity status, making him ‘the first such famous composer in British musical history’.Footnote 22 The decision later to self-publish the full score of Dioclesian involved the composer in a large financial outlay and left him horribly exposed to market conditions, so that when it eventually appeared in print at the end of February or the beginning of March 1691, it soon became clear that there was virtually no demand for that kind of publication.Footnote 23 A well-known comment in John Walsh's preface to Daniel Purcell's The Judgment of Paris (1702) further testifies to the score's commercial failure; there the publisher remarks on ‘the Celebrated Dioclesian of Mr. Henry Purcell … which found so small Encouragement in Print, as serv'd to stifle many other Intire Opera's, no less Excellent, after the Performance, not Dareing to presume on there own meritt how just soever, nor hope for a better Reception than the former’.Footnote 24 Significantly, Purcell never again attempted to publish a complete dramatick opera, his only other venture of that type being a collection of nine airs and a dialogue from The Fairy-Queen (1692), with accompaniments arranged for continuo only, which were intended for the amateur market. The spring and early summer of 1691 must have been a period of fiscal belt-tightening for Purcell. With the returns from his investment in the publication of Dioclesian coming in below expectation, and with his fee for King Arthur (late May – early June 1691) perhaps still in the offing, he was hardly in a position to distribute largesse, even to members of his immediate family. If the £40 cognovit is taken as evidence of a pecuniary advance made by Purcell to his sister-in-law, then such a loan was an extraordinarily generous gesture on his part, given the state of his own finances at the time.

I should now like to offer an alternative perspective on the same legal document that takes into account Purcell's domestic – as opposed to his financial – circumstances, and that possibly explains why Amy signed the cognovit when she did; but first, it will be necessary to set the scene with a few words about Purcell's residential history. From early 1685 until sometime in 1691 he and his family occupied a house close to the Abbey on the east side of a thoroughfare called Bowling Alley, in the parish of St Margaret's, Westminster. The record of the local taxes or rates that he paid each year allows us to track his movements in and out of the parish at any given time. However, for a period starting in December 1691, his mother-in-law Amy Peters assumed responsibility for the rates, no doubt because by then she had taken over the Bowling Alley house, probably in conjunction with her widowed daughter Amy Howlett. Duffy believes that Purcell waited until then before moving out, but there is no evidence to support this assumption.Footnote 25 Although he paid the highway rate for the year beginning Christmas 1690, there is no reason to suppose that he remained in the property right up to the next due date; clearly, he could have vacated it at any point during 1691, and it is significant that the last record we have of him paying the poor rate is for the period Easter 1690–1.Footnote 26 It is therefore possible that he moved out in late April of the latter year and took up residence somewhere closer to Dorset Garden, where King Arthur was about to go into production. He could then have sold his residual interest in Bowling Alley to Amy Howlett who, unable to make the necessary cash payment, may have entered into an arrangement with her brother-in-law whereby he mortgaged the property to her.Footnote 27Cognovits could be used to secure many types of loan, including those made for the purchase of leases and real estate; and it was not unusual for the mortgagor to give the mortgagee a cognovit note by way of collateral security, so as to enable him to enter up judgment and issue execution should the borrower default on the terms of the mortgage.Footnote 28 Amy's indebtedness to Henry may therefore have arisen not from a personal loan transaction but from the sale of his property rights in Bowling Alley, though until such times as further evidence comes to light there is no way of knowing which of these interpretations is the more plausible.

* * * * *

The second of the newly discovered lawsuits concerns an unpaid bill for goods supplied to one or both of the Purcells by a certain Mordant Cracherode. Although the cause of action arose early in June 1692, the start of legal proceedings was delayed until some time after the composer's death. The litigation is predictably vague about the nature of the goods for which payment was outstanding, and more precise information is retrievable only through an investigation of Cracherode's biography.

Mordant Cracherode: linen draper and plaintiff

The Mordant Cracherode (Cratcherode, Cracherood, Cratchrood) who sued Frances Purcell in King's Bench in 1698 was the grandfather of Rev. Clayton Mordaunt Cracherode (1730–99), the eminent bibliophile and print-collector who was a major benefactor of the British Museum.Footnote 29 Mordant was baptized on 27 March 1650 at Toppesfield, Essex, the second son of Mordaunt and Dorithy of Cust Hall. Details of his early life are obscure, but we do know that on 11 December 1678 ‘Mordant Cracherode of St Paul Covent Garden aged about 27 yeares Lynnen Draper and a Batchiler’, applied for a licence to marry Jane Calthorp/Calthrop, aged 21 and upwards.Footnote 30 The couple's only child, Isabella Dorathea, was baptized on 3 March 1680 at St Paul's. Within ten months of this event, however, Jane died and was buried at her family's ancestral seat at Ampton, Suffolk, on 11 January 1681. Mordant lived with his loss for nearly two years, and then on 11 October 1682, ‘aged about thirty’, he applied for a licence to marry Elizabeth Bullock of Hornsey, spinster, who was about 17 at the time, the eldest daughter of Edward Bullock.Footnote 31 Her sister Barbara later married George Abbot, linen draper of Covent Garden, who was Cracherode's apprentice and subsequently, perhaps, his business partner. The Bullocks, a gentry family like the Calthorps, were seated at Faulkbourne Hall, near Braintree in Essex. Elizabeth (d. 1694) and Mordant had at least seven children, of whom the second-born, named after his father, was the most distinguished. Mordant senior survived into the new century and was buried ‘in ye Church’ at Covent Garden on 7 January 1709.Footnote 32

‘Covent Garden is the Heart of the Town’

The social, economic and cultural life of that part of Westminster in which Cracherode lived and worked is of crucial relevance to our enquiry.Footnote 33 Covent Garden had been a greenfield site on the western edge of London until 1629, when Francis Russell, fourth Earl of Bedford, began to develop the 20-acre plot and transform it into an exclusive residential suburb ‘fitt for the habitacions of Gentlemen and men of abillity’.Footnote 34 In consultation with Charles I and Inigo Jones, Surveyor of the King's Works, he formulated plans for an Italianate housing development surrounding a central piazza that was destined to become London's first square, with three sides of tall terraced houses completed on the west side by the new parish church of St Paul Covent Garden in matching Palladian design. The rents attached to the newly constructed mansions were beyond the reach of all but the best families, and soon City tradesmen at the quality end of the market moved westwards, attracted by the business potential of the district. However, it was only after the Restoration that it gained its reputation as a high-profile site of élite consumerism. Substantial retail outlets began to appear in the local rate books of the 1670s, with Bedford Street, King Street and Henrietta Street in particular becoming a centre for fashionable mercers, lacemen and linen drapers. John Strype's description of the parish, with ‘its fine, streight [sic], and broad Streets, replenished with such good Buildings, and so well inhabited by a Mixture of Nobility, Gentry, and wealthy Tradesmen, here seated since the Fire of London 1666, scarce admitting of any Poor, not being pestered with mean Courts and Alleys’, was doubtless as true of the 1680s and 1690s as it was of the early eighteenth century.Footnote 35 However, it would be easy to exaggerate the extent to which Covent Garden constituted a socially segregated enclave; the area may have been built as a showcase for wealth and state, but it could not insulate itself from the turbulent diversity that characterized commercial culture in early-modern England. Some of its exclusivity was sacrificed on the altar of convenience around 1655, when a market was added to the centre of the square. Furthermore, Covent Garden had had an unbroken association with the theatre since the early 1630s, and the establishment of the Theatre Royal in nearby Brydges Street in 1663 imparted a raffish quality to the neighbourhood. As an urban recreational space it attracted people from all walks of life, and many artists, musicians, actors and playwrights took up residence in the area to be near their place of work.Footnote 36

Cracherode was not the sort of retailer one would normally turn to for the supply of inexpensive textiles for everyday household use and clothing, though on occasion he did provide his parish church with practical attire in the form of linen surplices.Footnote 37 From business premises on the south side of Henrietta Street, which he occupied from the mid-1670s, he was linen draper to the rich and famous.Footnote 38 Together with his elder brother Anthony, who was a woollen draper in nearby Bedford Street, they fulfilled a number of government contracts for the provision of goods to the royal family and the armed forces. The Treasury Books for March 1690 contain a payment to ‘Mr. Cracherode, linen draper’ for £332 10s 0d, under the heading ‘Accounts of tradesmen's bills for the Robes for one year from the King's Accession to Feb. 13 last’.Footnote 39 In the same year Anthony was contracted to provide clothing for several regiments serving in Ireland;Footnote 40 and in May 1695 he received £330 3s 6d and £258 8s 6d in respect of various monies owed to the late Queen Mary's servants and tradesmen.Footnote 41 Mordant could also count among his clientele the wives and daughters of affluent city merchants and professionals, as well as members of the nobility and gentry, as the following receipt from Sarah Churchill, later Duchess of Marlborough, shows:

Received of ye Right Honoura ble ye Lady Churchell ffebruary ye 12 1684 [1685] In full ye sume of eighteene pounds & seventeene shillings for ye use of my Master Mordant Cracherode[.] I say Received by me

Geo: Abbott

£18. 17. 00Footnote 42

Covent Garden was clearly a highly select and expensive retail environment, though – as the second lawsuit demonstrates – it was not one that the Purcells considered to be beyond their means.

Cracherode v. Purcell

Let us now look more closely at the details of the case. On Friday 24 June 1698 (the first day of Trinity term) Mordant Cracherode initiated proceedings against Frances Purcell as executrix of her dead husband's will.Footnote 43 The preamble to the litigation states that the action belongs to the type known as ‘trespass on the case’, that is, an action to recover damages that are not the immediate result of a wrongful act but rather a later consequence. Although Cracherode's bill is relatively straightforward and typical of its kind, it does present several problems of interpretation for anyone unfamiliar with common-law procedure. To avoid the misconceptions that would inevitably arise from a literal reading of the text, a brief explanation of the legal background has been provided to help readers better understand the case and some of the more curious aspects of seventeenth-century pleading.

The action used to prosecute trespass on the case was known by the Latin name ‘assumpsit’ (‘he undertook’), in which damages was the primary remedy. Because the plaintiff alleged that the defendant, being indebted (‘indebitatus’) in a certain sum of money, promised to re-pay that sum, the appropriate form of pleading was called ‘indebitatus assumpsit’. It was necessary to show how the debt had arisen, but the details of the transaction needed only to be set out in summary form. Thus there developed a small number of standard formulae – the so-called indebitatus or ‘common’ counts – to cover the situations that arose most frequently. For instance, a shopkeeper wishing to bring an action for the price of goods against the purchaser would use the common count ‘for goods sold and delivered at his request’; or a carpenter suing for wages would count that his client was indebted to him in £n for ‘work and services performed’, and so forth. Even if there was no sum certain, as when, for example, the defendant ordered goods or services without first agreeing the price to be paid for them, an action could still lie; the plaintiff would simply base his claim on an assessment of the reasonable value of work done (‘quantum meruit’ – ‘as much as he deserved’) or of goods supplied (‘quantum valebant’ – ‘as much as they were worth’). These various types of count were commonly used in the alternative, that is, the plaintiff could allege several versions of the same claim in multiple counts; no restriction was imposed on the number of these alternatives, which were quite fictional and not necessarily even consistent with each other. The reason why the practice of alternative pleading, with all its apparent prolixity and redundancy, enjoyed such longevity in the English legal system was that it provided a hedge against the unpredictable nature of the trial process. One of the lawyer's most challenging tasks was to identify, from the wealth of information gathered in bringing a case to court, the particular facts that would support most persuasively his client's position. Furthermore, situations frequently arose in which one simply had no way of knowing, in advance of trial, which of several equally convincing versions of his claim would be upheld by the evidence. Multiple counts were therefore introduced as a means of maximizing the lawyer's flexibility should the testimony unfold in unforeseen directions.

According to Cracherode's declaration, Purcell became indebted to him on 3 June 1692 in the parish of St Martin-in-the-Fields in a transaction allegedly involving the sum of £100, ‘for divers goods and wares sold and delivered by the same Mordant unto the said Henry…at [his] special instance and request’.Footnote 44 As already indicated, the bill does not specify the nature of the goods, or whether they were bought for the use of Frances or Henry, or both of them. It would certainly be wrong automatically to assume that they were Henry's purchases simply because he is cited as buyer in the case. Married women's choices were effectively concealed behind the names of their men in the ledgers of most shopkeepers because of the common-law principle of coverture, which deprived wives of the ability to enter into economic contracts in their own right. In any subsequent litigation, a married woman's debts became the responsibility of her husband because she was a ‘feme covert’, entitled to the protection of her ‘baron’ or ‘lord’. The English courts also developed the so-called ‘law of necessaries’, which further enforced a husband's obligation to support his wife during an ongoing marriage. Under this doctrine wives enjoyed the right to pledge their husband's credit for ‘necessary’ (but not ‘luxury’) goods. ‘Necessaries’ referred to more than articles essential for the preservation of life, and could include items that were considered appropriate to the woman's social position; thus, an expensive dress might be held a necessity for the wife of a person of status, while only a more modest garment would be deemed ‘necessary’ for the spouse of a less well-to-do man. It was up to the vendor to determine the creditworthiness of individuals by drawing on local knowledge and his perceptions of their spending patterns and social standing. If his judgment proved faulty, he could collect the wife's debt from her husband on a contract implied in law.Footnote 45

Cracherode's second count is of the ‘quantum valebant’ variety and alleges that, at ‘the same day, year and place abovementioned’, he sold to Purcell ‘divers other goods and wares’, for which Henry promised to pay him so much money as they ‘were reasonably worth at the time of their sale and delivery’. Cracherode estimates the value of this merchandise at another £100, a figure that is quite fictitious since it is not additional to the original demand, but an alternative to it. He then concludes his declaration in the usual manner with an assignment of breach, setting out in characteristically formulaic language Purcell's various infractions of his obligation to pay:

the aforesaid Henry…and the aforesaid Frances after the said Henry's death, paying scant regard to his aforesaid promises and undertakings made in the aforesaid way, but contriving and fraudulently intending craftily and subtly to deceive and defraud the said Mordant in that behalf, has not yet paid the aforesaid several sums of money or any penny thereof unto the said Mordant or contented him in any wise for the same, although the said Henry…and the aforesaid Frances after the said Henry's death was requested so to do by the said Mordant (namely on 10 May 1698 and frequently thereafter in the aforesaid parish in the aforesaid county); but the aforesaid Henry…and the aforesaid Frances…have altogether refused to pay the said Mordant the aforesaid several sums of money or any penny thereof, or to content the same Mordant in any wise for the same, and the aforesaid Frances still refuses to pay, to the damage of him the said Mordant £200. And thereof he produces suit.

The reason why Cracherode is now claiming £200 is not because there was a second £100 shopping spree on 3 June 1692; rather, he is adding to Purcell's existing liability an amount for interest, costs and charges that was traditionally calculated as being roughly equivalent to the alleged debt.Footnote 46

When the case came to court on 24 June 1698 Frances was represented by her brother John Baptist Peters, who initially addressed the quantum valebant count and denied that Henry had given the assurances claimed by Cracherode ‘in the manner and form as the aforesaid Mordant complains against him above’. Having therefore arrived at an issue, both parties put themselves ‘on the country’, that is, they expressed their willingness to stand trial and allow the matter to be decided by a petty jury. Peters then turned his attention to the declaration's first count, and sought wholly to defeat Cracherode's action by entering a plea in bar; this was a plea that, rather than addressing the merits and denying the facts alleged, introduced some extrinsic matter to show the court why the case against his client should not be allowed to proceed. Peters challenged Cracherode's right of action by entering a plea of tender, that is, a pleading asserting that Frances had consistently been prepared to pay so much of the debt as she admitted to, namely seven shillings and sixpence. To comply with the law, she had to make this offer unconditionally to the plaintiff before his case came to court, so she claims that tender of the 7s 6d was made on 30 April that year. Since then, she has repeatedly tried to settle with Cracherode, who has refused her offer, and has now had the money brought into court to fulfil the conditions of her plea.

It is possible to discern Peters's strategy in this legal skirmishing from what Blackstone has to say on the subject of tender:

… after tender and refusal of a debt, if the creditor harasses his debtor with an action, it then becomes necessary for the defendant to acknowledge the debt, and plead the tender; adding that he has always been ready, tout temps prist, and still is ready, uncore prist, to discharge it: for a tender by the debtor and refusal by the creditor will in all cases discharge the costs, but not the debt itself; though in some particular cases the creditor will totally lose his money.Footnote 47

In light of this, Peters asked that the case against Frances be dismissed. Cracherode then petitioned the court for leave to imparl, that is, he asked for time to consider his next step, and he was given until 23 January following, the first day of Hilary term 1699, to answer the defendant's plea. On that day Cracherode's attorney claimed that there was nothing in Frances's plea to preclude his client from proceeding with his action, and denied her allegation that she had offered to pay the 7s 6d. He therefore asked for the matter to be ‘enquired into by the country’, which was the plaintiff's way of submitting himself to the judgment of his peers. The sheriff was ordered to summon a jury to determine the matter and a date was set for the trial. Frustratingly, however, the case appears to have been discontinued and, with no record of any judgment, it must be assumed that an out-of-court settlement was brokered between the parties.

It is a matter of regret that Cracherode v. Purcell did not run its full legal course, because if it had we might have a better idea of how much the defendant really owed, and derive from that a clearer picture of what was bought. Certainly it would be a mistake to treat Cracherode's claim for £100 as an accurate tally of the Purcells' expenditure in his shop, for in actions on the case there was always a substantial difference between the defendant's actual liability and the sum that the plaintiff claimed in damages, which was invariably arbitrary and inflated. Had damages been awarded an ‘inquisition’, comprising 12 good and law-worthy men from the sheriff's bailiwick, would have been summoned and charged under oath with making a just assessment of the complainant's losses and costs; in every case of this type known to me, their deliberations produced a figure that was considerably lower than that claimed by the plaintiff. To illustrate the point: in 1753 a Bath tailor took the celebrated castrato Gaetano Guadagni to court for the price of garments that the tailor himself valued at £53, though he claimed £100 for them; an inquisition subsequently awarded him £51 8s. 6d, plus £9 11s. 6d for his costs and charges.Footnote 48 Although Cracherode v. Purcell was abandoned before the point at which damages were sought, one can arrive at a rough estimate of the defendant's true liability by comparing the case with those Cracherode brought against his other customers. In the only one of these that reached judgment he claimed £500 (plus £100 costs) from one Alice Lee, but he was awarded just £157 13s. 4d (and £6 in costs and charges).Footnote 49 If the ratio of claim to award in this instance is applied pro rata to Cracherode v. Purcell, then Henry's debt could have been as little as £31.

The Purcells, Cracherode and credit

Almost certainly, Cracherode would not have expected to receive immediate payment for his merchandise, since his class of client usually demanded boundless and endless retail credit as of right. Three months was the norm, though certain customers received more favourable terms, especially if they were aristocratic. For instance, in the summer of 1694 Cracherode sued Thomas Grey, second Earl of Stamford, for unpaid goods that the countess had bought from him in October 1690, when she was single;Footnote 50 but such forbearance was uncharacteristic of Cracherode, as other cases amply demonstrate. In January 1695 he initiated proceedings against Edward Hodgson for a debt of £50 incurred some three months earlier; at Easter 1697 he took John Thurman to court for the sum of £30 that was owing since the previous December;Footnote 51 and in the following autumn, in the case involving the above-mentioned Alice Lee, he sued for damages and costs of £600 arising from business transacted in June of that year. Why did Cracherode wait so long for Frances to settle her account, and why did he bring his action when he did? The answer to the second question has two key aspects. News of Frances's posthumous publication of several of her husband's works may have filtered through to Cracherode over the period 1696–8, leading him to conclude (rightly or wrongly) that the profits derived therefrom had put her in a better position to pay off what she owed.Footnote 52 The second major consideration for Cracherode was undoubtedly the Statute of Limitations (1623), which prescribed the periods within which proceedings to enforce a right had to be taken, or the action would otherwise be barred.Footnote 53 The time limit assigned for the prosecution of actions in tort, trespass, case, debt and simple contract was six years from the date the debt became due. If the event or combination of events giving rise to the plaintiff's cause of action fell outside the time-frame laid down for it, the defendant could plead the Statute of Limitations in bar of such action. A litigant and his attorney therefore had to be aware of such temporal restrictions and ensure that his claim was not out of time, for if the lawsuit was not filed before the statutory deadline the right to sue or make a claim was dead forever.Footnote 54 The Purcells became indebted to Cracherode on 3 June 1692, and he filed his suit against Frances in May 1698, in the very nick of time.

The other fundamental question one needs to ask is: why did Cracherode, who was not known for his patience with creditees, wait to the latest possible moment before going to court? Here there are no ready answers. His perspective on Frances's indebtedness may have been culturally determined to some extent; after all, showing kindness to widows and fatherless children was a long-sanctioned Christian precept in early-modern Europe. However, charity alone cannot have motivated Cracherode, for by the time of Henry's death he had already indulged the couple for over three years from the date the debt was payable. After 1695 his generosity extended for another three years until he was faced with the stark choice of either losing his money irretrievably or litigating. It is difficult to account for his apparent reluctance to sue without entering the realms of speculation, but it seems likely that such favour as he showed the Purcells would have been reserved only for regular clients whose custom he was anxious to retain, or whose loyalty over the years he wished to reward.

Assuming that the business the Purcells transacted on 3 June 1692 was not an isolated, one-off event, one needs to address the question of why a ‘middling’ family such as they shopped for clothes in a high-end retail outlet like Cracherode's. Had Henry's work for the stage, which had occupied most of his time since c.1690, been so lucrative that he could now afford Covent Garden prices? Had the Purcells recently moved from Bowling Alley to the Covent Garden area to be near the London theatres, and was it simply the case that Cracherode's emporium was close to their new abode? Or were they now moving in a more élite social circle, and had one of its members recommended the linen draper to them? Certainly, the celebrity that Purcell enjoyed in the early 1690s appears to have given him more direct access to the upper echelons of society, as his list of pupils at the time – which included Lady Rhoda Cartwright and Lady Annabella Howard – bears witness.Footnote 55 Annabella was the fourth wife of the poet and politician Sir Robert Howard (1626–98), whose granddaughter Diana was another of Henry's students; and Howard's brother-in-law was John Dryden, with whom the composer collaborated on many stage productions in the early 1690s. It is impossible to say how the Purcells would have reacted to the courtly and theatrical environment in which they occasionally found themselves, and so one can only tentatively weigh up the possibilities. Historians today still draw on Veblen's theory of ‘conspicuous consumption’ to alert us to the ways in which consumption (and not only work and income) structures and rationalizes social inequality. Dress in particular was a potent marker of social rank in late seventeenth-century London, and people used clothes to enhance their social credit and define their position in society. In a city where appearances mattered greatly, a man's reputation depended as much on what his wife and daughters wore – not least because it was most often he that footed the bill – as on the quality and cut of his own outfit.Footnote 56 But consumption was not just about status and hierarchy; it was also concerned with symbolic communication between individuals and groups.Footnote 57 Goods acquired value in a shared system of meaning and played an important role as symbols of belonging in social networks. Clothes bound people together and fostered female friendships, with consumer peer-groups exerting the most significant influence on shopping habits. Consumption practices therefore shaped identity and sociability, and operated as a means of social inclusion and exclusion.Footnote 58 Constant exposure to new fashions must have intensified the need to keep pace with the latest trends, a situation made all the more tempting by retailers like Cracherode who offered goods on credit. In the circumstances one could perhaps understand it if the Purcells, inhabiting the fashionable beau monde of courtly society and the élite side of London's theatre scene, felt the need to emulate their social superiors.Footnote 59

Conclusion

The King's Bench documents allow us glimpses into Purcell's family life, seen ‘through a glass darkly’. This is particularly so with regard to the first case which, when contextualized within his biography, appears to lend itself to two possible readings: either Amy Howlett borrowed the £40 for an unspecified purpose, or she took on the debt as a form of mortgage repayment on Purcell's Bowling Alley house after he had vacated it. In either case, the cognovit functioned as security for the loan, an understandable precaution for Purcell to have taken in light of his own somewhat precarious financial situation after over-reaching himself with the score of Dioclesian. Depending on the view one takes of the cognovit, Purcell either acted magnanimously in coming to his sister-in-law's aid, or the loan was a matter-of-fact transaction made as part of the process of transferring the title in his former property to her. The second case demonstrates that the Purcells were in debt at the time of Henry's death.Footnote 60 It is generally acknowledged that the reason why Frances published so much of her husband's music posthumously was to generate an income that would help support her and her children in widowhood. Some commentators have gone a step further and taken Frances's dedications at their word, believing that she was also motivated by a desire to perpetuate his memory. The case of Cracherode v. Purcell suggests that there may have been a third reason for the flurry of publishing activity between 1696 and 1698 – Frances's need to settle a debt which, despite her attempt to underestimate it in court, was substantial. If Henry had lacked the means to pay off the money he owed Cracherode, then his widow would surely have struggled to do so, left – as she was – without even the pension to which she was entitled.Footnote 61 Providing for herself and her children were overriding considerations, but acquitting the debt must also have been a major preoccupation. Finally, both cases now enable us to close the book on the question of who were Purcell's in-laws – a subject on which even the composer's most recent biographer has expressed some uncertainty.Footnote 62 Given what we know about the origins of Amy Howlett and Frances Purcell, there can be no doubt that John Baptist Peters defended them because they were his sisters.

DOCUMENTS

1. Henry Purcell v. Amy Howlett

KB27/2086 (Trinity 3 William & Mary), part 2, rotulus dccccviiijFootnote 63

Londonie Henricus Purcell ponit loco suo Ricardum Bogan Attornatum suum versus Amiam Howlett de placito debiti etc.

Londonie Amia Howlett ponit loco suo Johannem Baptistam Peters Attornatum suum versus Henricum Purcell de placito debiti etc.

Londonie Memorandum quod die veneris proximo post crastinum sancte Trinitatis isto eodem Termino coram Domino Rege et Domina Regina apud Westmonasterium venit Henericus [sic] Purcell per Ricardum Bogan Attornatum suum et protulit hic in Curia dictorum Domini Regis et Domine Regine tunc et ibidem quandam billam suam versus Amiam Howlett Viduam in Custodia Marrescalli etc. de placito debiti Et sunt plegii de prosequendo scilicet Johannes Doe et Ricardus Roe que quidem billa sequitur in hec verba scilicet Londonie Henericus [sic] Purcell queritur de Amia Howlett Vidua in Custodia Marrescalli Marescalcie Domini Regis et Domine Regine coram ipsis Rege et Regina existente de placito quod reddat ei Quadringinta libras legalis monete Anglie quas ei debet et iniuste detinet pro eo videlicet quod cum predicta Amia vicesimo die Maij Ann o regni Domini Williemi et Domine Marie nunc Regis et Regine Anglie etc. tertio apud Londoniam predictam videlicet in parochia Beate Marie de Arcubus in Warda de Cheape mutuata fuisset de prefato Henrico predictas Quadringinta libras Solvendas eidem Henrico cum inde postea requisita esset predicta tamen Amia licet sepius requisita etc. predictas Quadringinta libras eidem Henrico nondum solvit sed illas ei hucusque soluere omnino contradixit et adhuc contradicit ad dampnum ipsius Henrici Centum librarum Et inde producit sectam etc.Et predicta Amia Howlett per Johannem Baptistam Peters Attornatum suum dicit quod ipsa non potest dedicere accionem predictam predicti Henrici Purcell supradictam nec quin ipsa debet dicto Henrico predictas Quadringinta libras modo et forma provt predictus Henricus versusFootnote 64 eamFootnote 65 narravit

cognovit Ideo consideratum est quod predictus Henricus Purcell recuperet versus prefatam

xxvijo die Amiam Howlett debitum suum predictum necnon Quadringinta et tres solidos et

Junij 1691 quatuor denarios pro dampnis suis que sustinuit tam occasione detencionis debiti illius quam pro misis et custagiis suis per ipsum circa sectam suam in hac parte appositis eidem Henrico per Curiam dictorum Domini Regis et Domine Regine nunc hic ex assensu suo adiudicatis Et predicta Amia Howlett in Misericordia etc.

MiaFootnote 66

TranslationFootnote 67

London Henry Purcell appointsFootnote 68 Richard Bogan as his attorney against Amy Howlett in a plea of debt etc.

London Amy Howlett appoints John Baptist Peters as her attorney against Henry Purcell in a plea of debt etc.

London Be it remembered that on Friday next after the morrow of the Holy TrinityFootnote 69 in this same term there came before the Lord King and Lady Queen at Westminster Henry Purcell by Richard Bogan his attorney, and he brought here into the court of the said Lord King and Lady Queen then and there a certain bill of his against Amy Howlett, widow, in the custody of the marshal [of the marshalsea] in a plea of debt. And there are pledges of prosecution, that is to say, John Doe and Richard Roe. Which bill follows in these words: London Henry Purcell complains of Amy Howlett, widow, being in the custody of the marshal of the Lord King and Lady Queen's marshalsea of the King's Bench, on a plea that she should render to him forty pounds of legal money of England which she owes him and unlawfully withholds; that is to say, that whereas the aforesaid Amy on the twentieth day of May in the third year of the reign of the Lord William and Lady Mary now King and Queen of England [1691], in London aforesaid, namely in the parish of St Mary-le-Bow in the Ward of Cheap, had borrowed of the abovementioned Henry the aforesaid forty pounds, to be paid to the same Henry whenever afterwards she should thereunto be requested. Nevertheless, the aforesaid Amy, although frequently asked etc., has not yet paid the aforesaid forty pounds to the same Henry, but has so far altogether refused to pay them [i.e. the £40] to him and still refuses, to the loss of him the said Henry one hundred pounds. And he produces suit thereof, [and good proof]. And the aforesaid Amy Howlett by John Baptist Peters, her attorney, says that she cannot gainsay the aforesaid action of the aforesaid Henry mentioned above, nor but that she oweth the said Henry the aforesaid forty pounds in the manner and form as the aforesaid Henry has declared against her.

Action Therefore it is decided that Henry Purcell should recover against the afore

acknowledged mentioned Amy Howlett his aforesaid debt, and also forty-three shillings

27th day of and four pence for his damages which he sustained as much on account of the

June 1691 withholding of that debt as for his costs and charges laid out by him about his suit in that behalf, awarded to the same Henry with his assent by the court of the said Lord King and Lady Queen now here. And [be] the Mercy aforesaid Amy in mercy etc.

2. Mordant Cracherode v. Frances Purcell

KB27/2130 (Hilary 10 William III), part 1, rotulus ccccliFootnote 70

Middlesexie Mordant Cracherode ponit loco suo Josephum Dell Attornatum suum versus Franciscam Purcell viduam Executricem Testamenti et \vltime/ voluntatis Henrici Purcell nuper viri sui defuncti de placito transgressionis super Casum

Middlesexie Francisca Purcell vidua Executrix Testamenti et vltime voluntatis Henrici Purcell nuper viri sui defuncti ponit loco suo Johannem Baptistam Peters Attornatum suum adversus Mordant Cracherode de placito predicto

Middlesexie Memorandum quod die veneris proximo post Crastinum Sancte Trinitatis [1698] isto eodem Termino coram Domino Rege apud Westmonasterium venit Mordant Cracherode per Josephum Dell Attornatum suum Et protulit hic in Curia dicti domini Regis tunc ibidem quandam billam suam versus Franciscam Purcell viduam Executricem Testamenti et vltime voluntatis Henrici Purcell nuper viri sui defuncti in custodia Marrescalli etc de placito transgressionis super Casum Et sunt plegii de prosequendo scilicet Johannes Doe et Ricardus Roe que quidem \billa/ sequitur in hec verba Middlesexie Mordant Cracherode queritur de Francisca Purcell vidua Executrice Testamenti et vltime voluntatis Henrici Purcell vidua Footnote 71 nuper viri sui defuncti in custodia Marrescalli Marescalcie dicti domini Regis coram ipso Rege existente pro eo videlicet quod cum predictus Henricus Purcell in vita sua scilicet tercio die Junij anno domini Millesimo sexcentimo nonagesimo secundo apud parochiam Sancti Martini in Campis in \Comitatu/ Middlesexie predicto [1]Footnote 72 indebitatus fuisset prefato Mordant in Centum libris legalis monete Anglie pro diuersis Mercimoniis et Merchandizis ipsius Mordant per ipsum Mordant eidem Henrico in vita sua ad specialem instanciam et requisicionem ipsius Henrici in vita sua ante tempus illud venditis et deliberatis Et sic inde indebitatus existens idem Henricus in vita sua in consideratione inde postea scilicet eisdem die Anno et loco supradicto super se assumpsit et eidem Mordant adtunc et ibidem fideliter promisit quod ipse idem Henricus in vita sua predictas Centum libras eidem Mordant cum inde postea requisitus esset bene et fideliter soluere et contentare vellet [2] Cumque eciam predictus Henricus in vita sua postea scilicet eisdem die Anno et loco supradicto in consideratione quod predictus Mordant ad specialem instanciam et requisicionem ipsius Henrici in vita sua vendidisset et deliberasset eidem Henrico in vita sua diuersa \alia/ Mercimonia et Merchandiza super se assumpsit et eidem Mordant adtunc et ibidem fideliter promiset [sic] quod ipse idem Henricus in vita sua omnes tantas denarii summas quanta Mercimonia et Merchandiza predicta vltimo menccionata sic vt proferta vendita et deliberata tempore vendicionis et deliberacionis eorundem rationabiliter valebant eidem Mordant cum inde postea requisitus esset bene et fideliter soluere et contentare vellet Et idem Mordant in facto dicit quod Mercimonia et Merchandiza predicta vltimo mencionata sic vt proferta vendita et deliberata tempore vendicionis et deliberacionis eorundem rationabiliter valebant aliam summam Centum librarum consimilis legalis monete Anglie scilicet apud parochiam predictam in Comitatu predicto Et inde predictus \Henricus/ in vita sua postea scilicet eisdem die Anno et loco supradicto noticiam habuit Predictus [tamen] Henricus in vita sua et predicta Francisca post ipsius Henrici mortem promissiones et assumpciones predicti Henrici in vita sua in forma predicta factas minime curans sed machinans et fraudulenter intendens eundem Mordant in hac parte callide et subdole decipere et defraudare predictas separales denarii summas seu aliquem inde denarium eidem Mordant nondum solvit nec ei pro eisdem hucusque aliqualiter contentavit licet ad hoc faciendum idem Henricus in vita sua et predicta Francisca post ipsius Henrici mortem per prefatum Mordant (scilicet Decimo die Maij Anno domini Millesimo sexcentesimo nonagesimo octavo et sepius postea apud parochiam predictam in Comitatu predicto requisitus fuit) sed predictus Henricus in vita sua et predicta Francisca post ipsius Henrici mortem predictas separales denarii summas seu aliquem inde denarium eidem Mordant soluere seu eundem Mordant pro eisdem aliqualiter contentare omnino recusaverunt et predicta Francisca adhuc soluere recusat ad dampnum ipsius Mordant Ducentarum librarum Et inde producit Sectam etc.

Et predicta Francisca per Johannem Baptistam Peters Attornatum suum venit et defendit vim et iniuriam quando etc Et quoad secundam promissionem et assumpcionem in narracione predicta superius fieri supponitur eadem Francisca dicit quod predictus Henricus non assumpsit super se modo et forma provt predictus Mordant superius versus eam queritur Et de hoc ponit se [super] patriam Et predictus Mordant inde similiter etc Et quoad primam promissionem et assumpcionem in narracione predicta superius fieri supponitur eadem Francisca dicit quod predictus Mordant Accionem suam predictam inde versus eam habere seu manutenere non debet quia quoad Nonaginta novem libras duodecim solidos et sex denarios de predictis Centum libris parcellam eadem Francisca dicit quod predictus Henricus non assumpsit super se modo et forma provt predictus Mordant superius versus eam queritur Et de hoc ponit se super patriam Et predictus Mordant inde similiter etc Et quoad Septem solidos et sex denarios de predictis Centum libris residuum eadem Francisca dicit quod ipsa eadem Francisca post confeccionem promissionis et assumpcionis illius et ante exhibicionem bille predicte Mordant \predicti/ scilicet Tricesimo die Aprilis Anno regni domini Regis nunc Decimo apud parochiam predictam parata fuit et obtulit ad solvendum eidem Mordant predicto septem solidos et sex denarios quos quidem septem solidos et sex denarios idem Mordant de prefata Francisca adtunc et ibidem recipere penitus recusavit Et eadem Francisca vlterius dicit quod ipsa eadem Francisca semper postea hucusque parata fuit et adhuc existit ad solvendum prefato Mordant eosdem septem solidos et sex denarios ac illos hic in Curia profert parata \prefato/ Mordant \solvendum/ si idem Mordant eosdem septem solidos et sex denarios recipere velit Et hoc parata est verificare vnde petit Judicium si predictus Mordant Accionem suam predictam inde versus eam habere seu manutenere debeat etc Et predictus Mordant petit diem ad predictum placitum prefate Francisce interloquendi et ei conceditur etc super hoc dies inde datus est partibus predictis coram Domino Rege apud Westmonasterium vsque diem lune proximum post Octavas Sancti Hillarii videlicet [1699] prefato Mordant ad placitum prefatum Francisce predicte interloquendum et tunc ad replicandum etc ad quem diem \coram/ Domino Rege apud Westmonasterium venit tam predictus Mordant quam predicta Francisca per Attornatos suos Et predictus Mordant quoad predictum placitum predicte Francisce quoad predictos septem solidos et sex denarios superius placitatum dicit quod ipse per aliqua in eodem placito preallegata ab accione sua predicta inde versus eandem Franciscam habenda precludi non debet quia dicit quod predicta Francisca non obtulit ad solvendum eidem Mordant eosdem septem solidos et sex denarios provt eadem Francisca superius inde placitando allegavit Et hoc petit quod inquiratur per patriam et predicta \Francisca/ similiter etc Ideo \tam/ ad triandum exitum istum quam predictum alium exitum inter partes predictas superius similiter iunctum veniat inde Jurata coram Domino Rege apud Westmonasterium diem [blank] proximum post [blank] et qui nec etc ad recognoscendum etc quia tam etc Idem dies datus est partibus predictis ibidem etc.

Translation

Middlesex Mordant Cracherode appoints Joseph Dell as his attorney against Frances Purcell, widow, executrix of the last will and testament of Henry Purcell, her late deceased husband, in a plea of trespass on the case.

Middlesex Frances Purcell, widow, executrix of the last will and testament of Henry Purcell, her late deceased husband, appoints John Baptist Peters as her attorney against Mordant Cracherode in the plea aforesaid.

Middlesex Be it remembered that on Friday next after the morrow of the Holy TrinityFootnote 73 in the present term there came before the Lord King at Westminster Mordant Cracherode by Joseph Dell his attorney, and he brought here in the said Lord King's court, then there, a certain bill of his against Frances Purcell, widow, executrix of the last will and testament of Henry Purcell, her late deceased husband, in the custody of the marshal etc., in a plea of trespass on the case. And there are pledges for prosecuting, namely John Doe and Richard Roe. Which bill follows in these words:

Middlesex Mordant Cracherode complains of Frances Purcell, widow, executrix of the last will and testament of Henry Purcell, her late deceased husband, who is in the custody of the marshal of the Lord King's Marshalsea before the King himself [i.e. the Marshalsea of the King's Bench], because, that is to say, whereas the aforesaid Henry during his lifetime, namely on 3 June in the year of our Lord 1692, in the parish of St Martin-in-the-Fields in the county of Middlesex aforesaid, (1) was indebted to the said Mordant in £100 of lawful money of England for divers of the same Mordant's goods and wares sold and delivered by the same Mordant unto the said Henry during his lifetime at the special instance and request of the said Henry…before that time.Footnote 74 And being so indebted, the said Henry afterwards in his lifetime in consideration thereof, that is to say, the same day, year and place abovementioned did take upon himself and to the said Mordant then and there faithfully promise that he the said Henry in his lifetime would well and truly pay and satisfy the aforesaid £100 to the said Mordant when he should be thereunto required. (2) And whereas also the said Henry afterwards in his lifetime, that is to say, the same day, year and place abovementioned, in consideration that the said Mordant at the special instance and request of the said Henry…had sold and delivered divers other goods and wares, did take upon himself and to the said Mordant then and there faithfully promise that he the said Henry in his lifetime would well and truly pay and satisfy all such sums of money to the said Mordant when he should be thereunto requested as the same last mentioned goods and wares, as produced, sold and delivered, were reasonably worth at the time of their sale and delivery. And the said Mordant in fact doth say that the same last mentioned goods, as produced, sold and delivered at the time of their sale and delivery, were reasonably worth the sum of another £100 of similar lawful money of England, namely in the aforesaid parish in the aforesaid county. And afterwards the aforesaid Henry in his lifetime, namely the same day, year and place abovementioned, had notice thereof. [Nevertheless]Footnote 75 the aforesaid Henry in his lifetime and the aforesaid Frances after the said Henry's death, paying scant regard to his aforesaid promises and undertakings made in the aforesaid way, but contriving and fraudulently intending craftily and subtly to deceive and defraud the said Mordant in that behalf, has not yet paid the aforesaid several sums of money or any penny thereof unto the said Mordant or contented him in any wise for the same, although the said Henry in his lifetime and the aforesaid Frances after the said Henry's death was requested so to do by the said Mordant (namely on 10 May 1698Footnote 76 and frequently thereafter in the aforesaid parish in the aforesaid county); but the aforesaid Henry in his lifetime and the aforesaid Frances after the said Henry's death have altogether refused to pay the said Mordant the aforesaid several sums of money or any penny thereof, or to content the same Mordant in any wise for the same, and the aforesaid Frances still refuses to pay, to the damage of him the said Mordant £200. And thereof he produces suit, [and good proof].

And the aforesaid Frances by John Baptist Peters, her attorney, comes and defends the force and tort when etc. And as for the second promise and undertaking supposed to have been made above in the aforesaid declaration, the same Frances says that the aforesaid Henry did not take upon himself in the manner and form as the aforesaid Mordant complains against him above. And of this she puts herself on the country. And the aforesaid Mordant does likewise etc. And as for the first promise and undertaking supposed to have been made above in the aforesaid declaration, the same Frances says that the aforesaid Mordant ought not to have or maintain his aforesaid action against her therein because, as for ninety-nine pounds twelve shillings and six pence, part of the aforesaid one hundred pounds, the same Frances says that the aforesaid Henry did not take upon himself in manner and form as the aforesaid Mordant complains against him above. And of this she puts herself upon the country. And the aforesaid Mordant likewise etc. And as for the seven shillings and six pence of the aforesaid one hundred pounds remaining, the same Frances says that she the same Frances, after the making of that promise and undertaking and before the exhibiting of the aforesaid bill of Mordant aforesaid, namely on 30 April in the tenth year of our Lord now King [1698] in the parish aforesaid, was prepared and offered to pay to the same Mordant aforesaid seven shillings and six pence, which seven shillings and six pence the same Mordant then and there altogether refused to accept from the said Frances. And the same Frances further says that afterwards she the same Frances has always been and still is prepared to pay the said Mordant the same seven shillings and six pence and she brings them here into court ready to pay the said Mordant if the same Mordant is willing to accept the same seven shillings and six pence. And she is prepared to prove this, whereof she prays judgment whether the aforesaid Mordant should have or maintain his aforesaid action against her therein etc. And the aforesaid Mordant asks for a day to imparl to the aforesaid plea of the said Frances, and it is granted to him etc. Whereupon a day thereof is given to the aforesaid parties before the Lord King at Westminster, namely till the Monday next after the Octaves of St HilaryFootnote 77 for the said Mordant to imparl to the plea of the aforesaid Frances and then to answer etc. At which day before the Lord King at Westminster come both the aforesaid Mordant and the aforesaid Frances by their attorneys. And as to the aforesaid plea of the aforesaid Frances regarding the aforesaid seven shillings and six pence pleaded above, the aforesaid Mordant says that he ought not to be barred from having his aforesaid action against the same Frances by anything alleged by the same plea, because he says that the aforesaid Frances did not offer to pay the same Mordant the same seven shillings and six pence as the same Frances alleged above in plea. And this he prays may be enquired into by the country, and the aforesaid Frances likewise etc. Therefore, as much to try this issue as the aforesaid other issue similarly joined above between the aforesaid parties, let a jury therein come before the Lord King at Westminster on [blank] next after [blank], and who neither [to the plaintiff nor defendant have any affinity], to make recognition [on their oath whether the defendant is guilty or not], because both [have put themselves upon that jury]. The same day is given to the aforesaid parties there etc.