Part 1. Introduction, terminology

To date, writers of standard music-history texts and musicologists generally have tended to assume that the violin family of instruments is the staple of Western instrumental art music.Footnote 1 But in adopting this viewpoint, some of the most important musicians of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Hautboisten (pronounced obo'ist∂n), have been neglected in musicological research. In The Eloquent Oboe, the most comprehensive monograph dealing with historical oboes published to date, Bruce Haynes has signalled the importance of Hautboisten by stating that they ‘provided much of the musical background that is today the job of the radio and Muzak’.Footnote 2 Yet despite this he devotes only ten pages to the ensemble he introduces as the ‘hautboy band’,Footnote 3 further strengthening the commonly received opinion that Hautboisten were a marginal phenomenon rather than a standard in the musical life of the Baroque era.

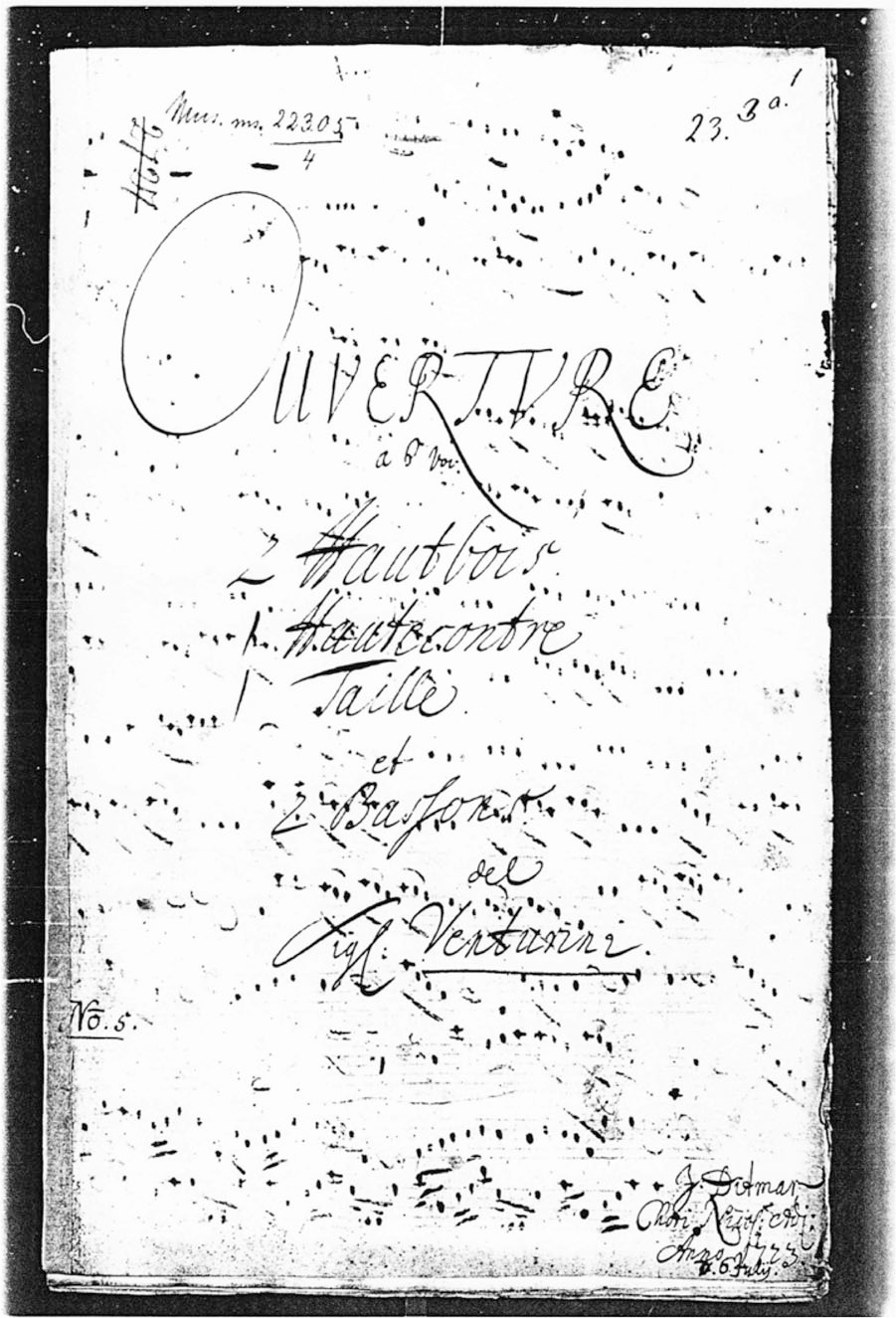

Haynes refers to more than 500 pieces for ‘hautboy band’ dating from the latter decades of the seventeenth century up until around the mid-eighteenth century that remain extant in libraries. Not surprisingly then, Haynes’ bibliography, Music for Oboe, 1650–1800, provides details of numerous compositions for Hautboisten, among them what he calls the Sonsfeldsche Musikalien Sammlung (the Sonsfeld Music Collection).Footnote 4 This Sonsfeld Collection, collated in the early eighteenth century by the Prussian General Friedrich Otto Freiherr (commonly translated as Baron) von Wittenhorst-Sonsfeld (1678–1755), contains those parts that still remain of his music library. Six extensive partbooks within this collection were almost certainly gathered together for the use of Hautboisten, and form the chief focus of this article. These partbooks represent the principal manuscript evidence of music performed by Hautboisten at the beginning of the eighteenth century and are now held in the Bibliotheca Fürstenbergiana, in the manor of the Freiherr von Fürstenberg in Herdringen, in the German region of Westphalia. This library belonged to Clemens Lothar von Fürstenberg (1725–1791) and has since been in the possession of the Fürstenberg family in Arnsberg/Herdringen.

Other sources of Hautboisten music are scant and often consist solely of one manuscript of a single composition in a library, and are usually not collated into a collection such as the six partbooks in focus here. The entry in Haynes’ bibliography of hautboy music contributes to the confusion of terminology regarding these sources by suggesting that the six partbooks were actually called the Sonsfeldsche Musikalien Sammlung. Therefore, the information given in Haynes’ bibliographic entry for this important source, which reads ‘52 multi-movement pieces of instrumental music for 2-3 Obs, Taille, 2 Bsns (usually 6 separate parts) and occasional Trp’,Footnote 5 will be questioned, since it appears that the Sonsfeld Collection comprises far more compositions in its entirety. Furthermore, as we shall see, David Whitwell's book chapter dealing with those compositions in the six partbooks that feature pure wind instrumentation will also be challenged.Footnote 6 As recently as 2003, he has assumed the partbooks were connected to ‘a Christian Friedrich Theodor von Fürstenberg’,Footnote 7 one of Clemens Lothar's earlier ancestors, who was in Paris in 1711 and 1712.

In order to make a clear distinction between Clemens Lothar's Bibliotheca Fürstenbergiana, Friedrich Otto's entire collection – the Sonsfeld Collection – and the six partbooks, the latter will be referred to as the Lilien Partbooks, since it appears that the three golden letters ‘G. v. L.’ embossed on the leather covers of the six partbooks refer most likely to Georg von Lilien (1652–1726), who appears to have been their original possessor, prior to them becoming part of the Sonsfeld Collection. For the catalogue numbering of the works in the Lilien Partbooks, which will be adopted from the partbooks, the abbreviation LPb has been devised for the incipit catalogue to clarify that these are the works in the Sonsfeld Collection that are found specifically in the Lilien Partbooks. Microfilms of the contents of the Bibliotheca Fürstenbergiana, including the six partbooks, are available at the Deutsches Musikgeschichtliches Archiv in Kassel.Footnote 8

Terminology – the profession of Hautboist

The word Hautboisten (also Hoboisten) is the plural form of the name for a musical profession once common in German-speaking countries. Their appearance in official eighteenth-century salary lists is relatively rare, and often the only surviving evidence of their existence comes in the form of documentation concerning conflicts with other groups of musicians such as Stadtpfeifer (town pipers), making research a challenging task.Footnote 9 Individual members of this profession were referred to by the title Hautboist (singular), which derives from the French hautbois (oboe). The term Hautboisten, however, cannot be simply translated as oboe-players, given that in addition to performing on double-reed instruments, such as oboes and bassoons, they were also able (and indeed expected) to play numerous other instruments. For this reason, even using the phrase ‘hautboy band’, as introduced by Haynes, seems to ignore the true versatility of these musicians.

The title Hautboisten was in use from the latter decades of the seventeenth century up until the end of World War I, by which time it had become a term used solely to describe military musicians. Not surprisingly then, many modern scholars were led to the conclusion that the term Hautboisten had at all times referred primarily to military musicians.

A further term in need of clarification here is ‘orchestra’. John Spitzer and Neal Zaslaw define the orchestra as an ensemble ‘based on string instruments of the violin family plus double basses’.Footnote 10 Among the additional key elements that constitute orchestras, they also require numerous violins, whose parts are doubled more than the other strings in the ensemble, as well as the presence of wind instruments, the latter usually not playing in unison and with the number employed depending on the era and location.

According to Michael Robertson the German Lullists, such as Johann Sigismund Kusser (1660–1727), followed the French tradition of doubling the outer parts in their orchestral works, scoring the bassoon along with the basses and both hautboys along with the first violin.Footnote 11 This seems to be true in many cases. In Kusser's opera Adonis, however, the composer employs five double-reed players among four of the five parts of the score. These are two hautboys, one Haut-contre d'hautbois (most likely another hautboy in C), one Taille d'hautbois and one bassoon. Regularly, the first hautboy plays in unison with the first violin, whilst the second and third hautboys join the second violin. The Taille doubles the part of the first viola and the bassoon plays the same part as the other basses.Footnote 12 In light of Kusser's instrumentation in Adonis it may be questionable, and warrants future investigation, whether Spitzer's and Zaslaw's definition was already the norm rather than one of many possibilities during the period they describe as the time of ‘the birth of the orchestra’, that is, 1680–1740.Footnote 13

From the mid-seventeenth century onwards the term Kapelle (chapel), which had previously been used largely to denote ensembles of vocalists, also came to refer to instrumentalists performing alongside the singers, and even to pure instrumental ensembles, which resembled an orchestra in today's commonly accepted sense, adding further to the confusion in terminology.Footnote 14

Although many courts, such as, for example, those based in Celle, Hanover, Dresden, Darmstadt, Stuttgart and Berlin, had orchestras established during the first half of the eighteenth century,Footnote 15 and the term ‘orchestra’ began to be established by that time, the vast majority of courts in the German-speaking territories comprised small earldoms and duchies, which did not have the financial means to support such large musical bodies. When Johann Mattheson (1681–1764) complained about every small court's desire for its own ‘orchestra’ in the 1725 issue of his periodical Critica Musica (published between 1722 and 1725), it may be understood that many such small groups of musicians did indeed exist.Footnote 16 Accordingly, it might be assumed that one-to-a-part instrumentation was still the norm rather than the exception at that time. Therefore, the term ‘orchestra’ will appear regularly with inverted commas throughout this article in order to remind the reader that different concepts of instrumentation existed in earlier periods.

Stadtpfeifer – Hautboisten

Prior to about 1680 when the hautboy came into fashion in German-speaking lands, there were already established ensembles specializing in wind instruments, comprising capable musicians who were required to perform on and teach string instruments as well. The tradition of these Stadtpfeifer groups can be traced back to the fourteenth century. They provided much of the music required in towns, including ceremonial music as well as music for pure entertainment. From the mid-seventeenth century they were organized into regional guilds, which provided them with the rights to perform music in their town of employment.Footnote 17 In addition to the income they received for their official work as civil servants, their guild affiliation entitled the Stadtpfeifer to earn a living by performing for any private occasion such as weddings and birthday celebrations.Footnote 18

When the newly developed hautboys arrived in German-speaking lands in the latter decades of the seventeenth century, naturally the Stadtpfeifer learned how to play these instruments and were required to show some proficiency on them;Footnote 19 however, there is also some evidence to suggest that on occasion Hautboisten groups were accorded a privileged status, and therefore provided competition to the Stadtpfeifer. For example, Renate Hildebrand has shown that in 1700 the so-called Hyntzsche Hautboistencompagnie was given the right to be the only ensemble to perform publicly on hautboys in the town of Halle.Footnote 20 On the other hand, in Leipzig, at the time when Johann Sebastian Bach was employed as the cantor of the St. Thomas’ Church (1723–50), it was the Stadtpfeifer Caspar Gleditsch who performed the parts for the first hautboy in Bach's works during the services.Footnote 21

The inclusion of the hautboy as part of already established groups, such as the Stadtpfeifer, as well as in the comparatively newly formed ensemble-type, the Hautboisten – both groups likely performed the same kind of music – makes a definitive investigation of their respective repertoire difficult. Yet although the professional titles of these groups differed, the similarity of the music they performed therefore serves as an indicator for the concept and understanding of Hautboisten ensembles in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Scope of this study

Where did these musicians usually find employment during the eighteenth century? What kind of music did they perform, and was this music really the same as that performed by the Stadtpfeifer, as implied above, or did their repertoire differ from that of the Stadtpfeifer? What were the typical instrumentations of the music they performed? What was the usual size of a group of Hautboisten? How can we identify whether music might have been intended specifically for Hautboisten? And, finally, can the analysis of the repertoire found in the Lilien Partbooks assist in establishing a fuller picture of the use of music in the daily life of Baroque society and the perception of the concept of Hautboisten by their contemporaries?

The analysis of a representative group of pieces contained within the Lilien Partbooks allows for significant light to be shed on Hautboisten and the role they played in the daily musical life of German towns, courts and the military. In addition to answering some of the questions outlined above, our understanding of the music profession in general during the eighteenth century may have to be revised in order to take into account this distinct, but often overlooked, group of musicians.

Achim Hofer investigated the extent and the significance of music composed specifically for regimental Hautboisten in his studies on the history of the military march.Footnote 22 The works collated in the Lilien Partbooks, however, are generally in a musical form that today would be categorized as ‘art music’. It is for this reason that the large number of marches still extant in libraries was ignored for the purposes of this article.

Furthermore, it is necessary to inform the reader that the number of secondary sources used for this article, not only in the parts concerning the general history of Hautboisten but also in the presentation of the provenance of the Lilien Partbooks, is due to the state of the manuscript data collated in the archives. Jacques Rensch from the Regionaal Historisch Centrum Limburg in Maastricht (Netherlands) stated in a personal conversation that the vast number of files concerning the history of the Sonsfeld family were yet to be catalogued and therefore could not be accessed by scholars.Footnote 23

Because not only the primary sources but also the recent output of research publications on Hautboisten are widely spread and require modern-day investigators to search in many different places, the following comprehensive summary of our current state of knowledge is warranted as an aid for future research.

Recalling the current state of knowledge of Hautboisten, their history, and the concept of homogeneous instrumental consorts (as evident in the scores of the time) will create a platform for an understanding of the music performed by these groups. The study of music that is known to have been composed for such groups aims to complement our historical knowledge. A comparison of these works, specifically composed for Hautboisten, with those contained within the Lilien Partbooks, will draw a picture of the types of music commonly heard as part of everyday life at the beginning of the eighteenth century.

Following this introduction, part 2 of this article details the French origins of these groups and further provides an overview of the current state of knowledge regarding the spread of Hautboisten from France to the German-speaking lands of the Holy Roman Empire. The prime source of information in this field remains a seminal book chapter published by Werner Braun in 1971,Footnote 24 and subsequently revised and translated into English in 1983: ‘The “Hautboist”: An Outline of Evolving Careers and Functions’.Footnote 25 Braun's chapter is therefore considered in some depth, together with a selection of more recent research.

Part 3 examines published music known to have been composed for use by Hautboisten during the first half of the eighteenth century, much of which was marketed directly to Hautboisten as potential buyers. Additionally, a selection of manuscript music for wind ensembles that features instrumentation typical for Hautboisten will be investigated.

Subsequently, the provenance and contents of the Lilien Partbooks within the Sonsfeldsche Musikalien Sammlung will be analysed in part 4. The distinct labelling of the six partbooks as the ‘Lilien Partbooks’ identifies them as a group and sets them apart from the rest of the entire collection currently owned by Wennemar Freiherr von Fürstenberg.

Part 2. The provenance of Hautboisten

France – the development of the Hautbois

Present-day scholars agree that the hautboy's origin can be found in France.Footnote 26 When King Louis XIV (1638–1715) reigned (from 1661), his passion for the arts provided musicians and instrument makers (often combined in one person) with employment and, more importantly, with the possibility, perhaps even the commission, to experiment and invent. The instruments in use at the beginning of the Sun King's sovereignty were still basically the same as they had been during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. In the 1660s, the woodwind instruments from these earlier periods, which at this stage had been in use for a long time, went through a number of experimental stages involving a series of modifications that led to the creation of the Baroque versions of the hautboy, the bassoon, the recorder and the transverse flute, among others. An exact date for the introduction of the newly invented hautboy into existing ensembles at the French court cannot be identified because the instruments now known as the shawm, Baroque oboe and modern oboe were at all times, in French, labelled hautbois. We are therefore reliant upon other sources, such as iconography, literature and music (which occasionally offers clues regarding scoring) to provide us with evidence of the change in the hautbois's use and appearance, in order to gauge the approximate date of structural changes made to the instrument.

About 30 years before the period of transformation of this double-reed instrument, Marin Mersenne, in his Harmonie universelle (Paris, 1636), described two versions of the hautbois in use in France. The illustration of the first, the hautbois (or as he also calls it, the ‘grands Haut-bois’), shows members of the instrument family today known as shawms.Footnote 27 In German sources of the same period this descant of the double-reed consort was referred to as the Schalmey and any lower versions, from the treble onwards, were called Pommer.Footnote 28 These were instruments with a double reed directly controlled by the lips with some support of a pirouette.Footnote 29 The distinct terminology in German-speaking lands, calling the earlier versions Schalmey and Pommer, whilst adopting the term Hautbois for the hautboy, makes it much easier to find particular dates as to when the newer version was first introduced into German music-making.

The second pertinent double-reed instrument discussed and illustrated in Mersenne's book is the Hautbois de Poictou (or Poitou), which appears to be an instrument with a wind cap covering the reed – similar to a crumhorn.Footnote 30 According to modern definitions this would perhaps no longer be classified as a member of the oboe family; however, surviving evidence seems to suggest that musicians may have experimented by playing without the cap for more direct control of the reed which is suggested by Bruce Haynes and Marc Ecochard, respectively, in their contribution to an anthology on evolving instruments and music from the Renaissance to the Baroque periods.Footnote 31

Ecochard discusses a letter by Michel de La Barre (ca. 1675–1745) that is an eighteenth-century report of the development of wind instruments at the French court between the 1660s to the 1680s.Footnote 32 Although La Barre omits to provide specific dates for the first use of the new hautboy (his testimony was written more than 80 years after the development of the new hautboy in ca. 1740), it provides us with a historical view of what might have happened.

La Barre claims that the newer version of the transverse flute was introduced much later than the hautboy, and that the constructional changes finally made the doublereed instruments ‘useful’ within an ensemble of other instruments such as violins, recorders, viola da gambas and plucked string instruments. He further names two players, Philibert Rebillé (1639–1717) and René Pignon dit Descoteaux (ca. 1645–1728), who were given new positions in 1667 to perform on the new transverse flutes.Footnote 33 Since these musicians are mentioned for the first time in official paylists in 1667,Footnote 34 La Barre's letter appears to prove that the hautboy was first introduced to the court music before that year.Footnote 35

Both types of hautbois presented by Mersenne are described as consort instruments of different sizes, thus confirming the fact that by the time Harmonie universelle was published in the early seventeenth century, the tradition of homogenous groups of instrument families was still in place. Combining these groups, in order to amalgamate the timbral characteristics of individual consorts, seems to have been the exception rather than the norm, and the idea of a large string ‘orchestra’ with an additional small number of wind instruments appears to be an innovation introduced by Jean-Baptiste Lully.Footnote 36

In trying to establish an accurate date before 1667 for the inclusion of the hautboy into existing ensembles at the French court it becomes clear that the process of development of the hautboy was one of transition over many years rather than a particular moment at which all the old instruments were exchanged with new ones. It is highly likely that for a long period the different versions of the hautbois coexisted.

According to Haynes, it is currently undoubtedly believed that a ‘useful’ hautbois (e.g. for joining a consort of various types of instruments) premiered in a performance with the Petite Bande in 1657 in Lully's work L'Amour malade.Footnote 37 His investigation of iconographic evidence within Mersenne's treatise and also on gobelins created in Charles Le Brun's (1619–1690) workshop led him to conclude that hautbois instruments between the mid-1650s and the early 1670s were ‘transitional’ versions which he calls ‘protomorphic hautboys’.Footnote 38 He further explains that Lully, apparently, did not score for hautbois in his stage works between 1664 and 1670, the latter being the year of the premiere of Le bourgeois gentilhomme.Footnote 39 Haynes concludes in his article that from towards the change of the decade up until 1664 protomorphic hautboys joined the strings of the Petite Bande, and that by 1670 the development of the new hautboy in its Baroque version was finalized.

France – provenance of double-reed ensembles

Initially, players of any type of wind instrument were generally employed by the Musique de l’Écurie; however, in the last decade of the seventeenth century, string consorts of the Musique de la Chambre and the Chapelle Royale began to engage double-reed players in permanent positions.Footnote 40 Whenever wind instruments were required within these groups prior to that time, they would have been specially invited for that particular occasion.

The Écurie was divided into five separate groups, of which the first four utilized double-reed instruments, while the fifth group, Les Trompettes, was an independent formation consisting of trumpets, timpani and drums:

Violon, Hautbois, Saqueboutes et Cornets

later known as the Douze Grands Hautbois du Roi

Hautbois et Musettes de Poitou

Fifres et Tambours

Cromornes et Trompettes Marines

Les Trompettes

By the sixteenth century it was not necessarily the case that the instruments mentioned in the title of a particular group were actually played by its members.Footnote 41 These titles were retained long after the musical style as well as the instruments themselves had changed. A further complicating factor is the fact that the majority of instrumentalists routinely performed on more than one instrument in this era, which makes it difficult to know exactly how the consorts were arranged. It seems likely, however, that the hautbois-instrumentsFootnote 42 were used initially in consort groupings as wind band instruments.

During the second half of the seventeenth century, double reeds were introduced, as a novelty, to the Petite Bande – the smaller of the two string consorts of the Musique de la Chambre. Although this may indicate the beginnings of the ‘orchestra’, with an instrumentation ratio of 4:1 for strings and woodwinds, it also suggests that the different consorts at court were still organized in the Renaissance tradition of smaller ensembles of like instruments, which retained their own qualities when performing together for special and rare occasions. Having one group taking the leading role, whilst others only provided additional tone colour, was the necessary innovation leading to the institutionalization of the ‘orchestra’.

The instruments used by the ensembles of the Écurie

The group at court that specialized above all in double-reed instruments was the Violons, Hautbois, Saqueboutes et Cornets, also known as the Douze Grands Hautbois du Roi, a formation that comprised ten hautbois and two bassons. A list of court employees dating from 1664 consulted by Marcelle Benoit makes it clear that each member of the Violon, Hautbois, Saqueboutes et Cornets was capable of performing on one string and one wind instrument.Footnote 43 It seems most likely that within this ensemble, wind instruments and string instruments did not perform together, but rather followed the long-standing tradition of employing ‘loud’ winds (hautbois) and strings in separate ensembles. This practice might also be evident in pitch differences between these instrumental families.Footnote 44

According to Anthony, the Douze Grands Hautbois performed in only three festivities throughout the year, and for the remaining time appeared with the string groups of the Chambre.Footnote 45 This reinforces the argument that this group usually performed as an independent consort on double-reed instruments at outdoor festivities. Furthermore, the versatility of this band also represents a prototype for those ensembles that were later to emerge as the popular groups of Hautboisten in German-speaking lands, with the flexibility in terms of instrumentation also in accordance with the music found in the Lilien Partbooks as well as other compositions extant in the Sonsfeld Collection.

The other groups of the Écurie that utilized the hautbois specialized in different instrumentations and appear to have had other duties within the musical life of the court. During the eighteenth century the Hautbois et Musettes de Poitou, for example, concentrated on flutes, recorders and musettes and was regularly associated with the Musique de la Chambre.Footnote 46 By the end of the seventeenth century the members of the Fifres et Tambours also seem to have exchanged their fifes for hautboys. They were involved with the Chambre as well, and may possibly have been the most commonly heard band of hautboy players at the court, performing in a variety of occasions.Footnote 47 Evidence of their work as outdoor musicians can be seen in the music of the so-called Philidor Collection (Partition de plusieurs marches, F-Pn Rés. F. 671) explored by Susan Sandman.Footnote 48 Ninety-one marches and airs for wind band and percussion within the collection were collated in 1705 by the musician André Danican Philidor (1647–1730), who was, along with Françcois Fossard (1642–1702), in charge of the music library at the French court during Louis XIV's reign.Footnote 49 These pieces, dating from the second half of the seventeenth century, are of great significance for research into the history of wind band music. Sandman states that this repertoire was possibly intended for an ensemble comprising some type of transitional hautbois,Footnote 50 rather than for the new hautboy and bassoon, which became the norm by the end of the seventeenth century.Footnote 51

The remaining group using the hautbois among the Écurie was the Cromornes Footnote 52et Trompettes Marines, members of which, according to Haynes, appear to have been paid less and were apparently of minor importance for music at the court.Footnote 53

One further ensemble that is crucial to this investigation was the Mousquetaires (sometimes also known as Plaisir du roi), up until 1683 the French military's double-reed band. Subsequently this group was no longer associated with the military, due to the king's decision not to engage double reeds in the battlefield anymore, but became one of the most utilized hautboy groups at court.Footnote 54 As with the other consorts of the Écurie, the Mousquetaires were known to be skilled players of string instruments in addition to their skill on the hautbois. They are yet another example of a prototype ensemble that was to become a common instrumental formation – the Hautboisten – in eighteenth-century German-speaking lands.

French musicians and their instruments in German-speaking lands

Towards the end of the seventeenth century, the number of players of the newly invented version of the hautbois had exceeded the availability of work at the French court. As the number of wind players at the Écurie had remained steady at 35 for more than a century,Footnote 55 and these positions were already occupied, it seems likely that many musicians had to apply for positions at smaller courts and towns or even outside of France.

Around this time, French music had become increasingly popular with members of the European nobility, many of whom also looked to France as a successful model of an absolute monarchy. French instrumentalists were made welcome in a number of countries, and many of them found employment in foreign lands including England, Spain and, of course, in German principalities. Since they brought the newly developed hautboy with them, and as this instrument was as yet unknown outside of France, there was an increasing interest in the employment of hautboy players who could teach the local double-reed musicians to play the new instrument. Among the German locations where French hautboy players were first engaged were the courts of Celle (1680), Stuttgart (1680), Hanover (1681) and Berlin (1681).Footnote 56

The context of the creation of the hautboy and the ensembles in which it was played, both before and after the constructional modifications undertaken at the French court, provides the background for a consideration of Hautboisten, in particular in the Holy Roman Empire, and is therefore crucial. As pointed out in this section, music at the French court in the seventeenth century was performed by groups of musicians rather than by virtuoso soloists. Those players who left France to work in the German-speaking lands were either employed as an existing group,Footnote 57 or, when seeking work as individuals, as teachers to create a group of players made up of local forces. At the Berlin court after 1690, for example, the Frenchman Pierre de La Buissière was employed to teach local players. In Dresden, two hautboy players with French names were employed in 1696, and in 1699 the famous François La Riche was part of the Dresden orchestra and most certainly educated a number of players.Footnote 58

Whilst the first part of this section has provided the reader with knowledge of the origins of the hautboy and its players, the following part will engage in a detailed discussion of previous research on Hautboisten to form the stage for understanding the situation in German-speaking lands, and, subsequently in Prussia.

Hautboist – a German profession

Werner Braun – ‘Typologie der Hautboisten’

Practically the only study to discuss the role of German Hautboisten in any detail is Werner Braun's chapter ‘Entwurf für eine Typologie der “Hautboisten”’, first published in 1971.Footnote 59 Its ongoing significance can be measured, in part, by the fact that the majority of subsequent publications focusing on Hautboisten have drawn heavily on Braun's work. To name two examples, Renate Hildebrand, in her Diplomarbeit (completed four years after the ‘Typologie’ was first published), gave a similar overview of the different employment possibilities for Hautboisten to that provided by Braun.Footnote 60 A more recent voice, Achim Hofer, indicated in a 2004 conference paper on the performance practices of Harmoniemusik that while Braun's chapter is somewhat obsolete, still no monograph has been dedicated to their existence, despite Braun's statement that there is plenty of evidence regarding Hautboisten.Footnote 61

Braun's information appears to have been gathered mostly from secondary sources. In particular, he uses Heinrich Christoph Koch's Musikalisches Lexicon (Frankfurt/Main, 1802) and Gustav Schilling's Enzyclopädie der gesamten musikalischen Wissenschaften (Stuttgart, 1835) to establish a detailed picture of Hautboisten and their role in German musical life. Yet, given that these two works were published almost a century later than Braun's era of interest – that is, the beginning of the eighteenth century – and provide the major body of evidence for his analysis, the relevance of this information needs to be challenged.

Recognizing that the majority of Braun's sources are secondary rather than primary ones, and bearing in mind his point that it is extremely difficult to investigate the many pieces of evidence in primary sources, most of which are not clearly organized, the present discussion is above all an analysis of the ‘Typologie’ as the first existing study into the role of Hautboisten.

If, as asserted by Haynes, these ensembles were indeed such a ubiquitous group,Footnote 62 we must ask ourselves why there is not more distinct evidence of their existence remaining in archives, libraries and private collections. With a sizeable number of bands of Hautboisten known to have been employed in Prussia alone,Footnote 63 and with the high numbers of Hautboisten active professionally at countless other smaller German courts as well as in towns and free cities, what has become of their music? Considering the enormous amount of music that has survived from the Baroque period, the 500-odd extant works for Hautboisten cited in Haynes’ bibliography appear to be relatively insignificant in terms of quantity. For this reason, the circumstance of the survival of the Lilien Partbooks fully justifies detailed research into their contents and provenance, and forms one important piece in the jigsaw that makes up the history of the Hautboisten.

It remains to be seen, however, whether these partbooks themselves are indeed so distinct, or if in fact they simply represent one facet of ordinary musical life at the beginning of the eighteenth century. Will an increased understanding of Hautboisten and the analysis of the music in the Lilien Partbooks perhaps call for us to redefine the term ‘orchestra’? Was Hautboisten music substantially different from, or merely identical to, the repertoire that any other instrumental ensemble would have performed for daily musical entertainment during this period? Does the music of the Lilien Partbooks represent music played by an Hautboisten Compagnie at the beginning of the eighteenth century? Furthermore, does any other music for Hautboisten remain extant that might illuminate further aspects of their professional activity?

Hautboist, Hautboistenbande, Hautboistencompagnie

Braun defines that ‘[a]n Hautboist or Hoboist, in the first half of the eighteenth century, […]’ must be ‘accomplished on the oboe, but […] also able to perform on other instruments’.Footnote 64 Skill on several instruments, which may have included the hautboy, bassoon, recorder and horn, as well as several string instruments such as the violin, violoncello and viola da gamba, was a general requirement for professional musicians in the first half of the eighteenth century.Footnote 65 Indeed, this had been the rule rather than the exception for all musicians prior to the specialization that led into the era of virtuosos at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Many recognized musicians and composers such as Johann Sebastian Bach, George Friderick Handel and Georg Philipp Telemann are all known to have been extremely proficient on a number of different instruments. One example can be seen in Johann Joachim Quantz's autobiography, in his description of his own music education:

| Das erste Instrument, welches ich erlernen mußte, war die Violine; zu welcher ich auch die größte Lust und Geschicklichkeit zu haben schien. Hierauf folgte der Hoboe, und die Trompete. Mit diesen drey Instrumenten habe ich mich in meinen Lehrjahren am meisten beschäftiget. Mit den übrigen Instrumenten, als Zincke, Posaunen, Waldhorn, Flöte a bec, Fagott, deutsche Baßgeige, Violoncell, Viola da gamba, und wer weis wie vielerley noch mehr, auf welchen allein ein rechter Kunstpfeifer muß spielen können, blieb ich auch nicht verschonet.Footnote 66 | The first instrument that I had to learn was the violin, at which I seemed to have the greatest pleasure and skill. This was followed by the oboe and trumpet. I occupied myself mostly with these three instruments during my apprenticeship. I was also not spared other instruments, such as cornets, sackbuts, horn, recorder, bassoon, German string bass, violoncello, viola da gamba, and who knows how many more, all of which a real Kunstpfeifer must be able to play. |

In addition to the skills on numerous instruments, many Hautboisten (usually the band leaders) were expected to be proficient composers. Hans Friedrich von Fleming (1670–1733), a contemporary writer on the organization of the military, noted in his book, Der vollkommene Teutsche Soldat (The Perfect German Soldier, 1726), that it was a requirement that every Premier (Hautboisten bandleader) should be able to compose and arrange for the needs of his ensemble: ‘The Premier among them has to be able to compose, in order for the music to be better adjusted [with regard to the arranging of existing works for the available instruments].Footnote 67

In 1724, Friedrich Wilhelm I, King in Prussia, founded an orphanage for the children of deceased soldiers in Potsdam, as a direct response to the increase in the number of such orphans in the aftermath of war.Footnote 68 Hans-Joachim Bandt cites the now lost General-Reglement, the foundational regulations for this institution (signed in Berlin on 1 November 1724), which establishes that the children were to receive a general education alongside instruction in a craft in preparation for a future profession:

| Nachdem Sr. Königlichen Majestät in Preußen usw. Unserm allergnädigsten Herrn allergnädigst gefallen, allhier in Potsdam ein Waysenhaus für Dero Grenadier- und Soldatenkinder von Dero Armee als höchster Stifter zu bauen und zu fundieren, so daß selbige darinnen nicht allein wohl versorget, und in ihrem Christentum, Schreiben und Rechnen gehörig informieret, sondern hiernächst auch zu einer annehmlichen Profession gebracht werden sollen, damit sie nicht allein einmahl zu Gottes Ehren leben, sondern sich auch ihr Brodt, wie es christlichen und rechtschaffnen Unter-thanen eignet und gebühret, mit ihrer Hände Arbeit hiernächst schaffen können.Footnote 69 | Since it has pleased our gracious Lord his Royal Majesty in Prussia etc. graciously to build and found an orphanage here in Potsdam for the children of the infantry's grenadiers and soldiers as its highest donor so they are not only cared for, properly educated in Christianity, writing and arithmetic, but also brought to an acceptable profession, so that they do not solely live to the glory of God, but can earn their bread with their own hand's work as it is proper and due to Christian and righteous subjects. |

In that same year, soon after its establishment, an Hoboistenschule was integrated into the school, in order to train talented students in music under the direction of Heinrich Gottfried Pepusch (after 1667–1750), the younger brother of Johann Christoph Pepusch (1666/67–1752). Not only did the school provide the orphans with the possibility of future employment, but it also supplied a pool of young Hautboisten to fill the many vacancies in the numerous Prussian regiments at the time. According to the school's regulations, students were obliged to work as military Hautboisten for eight, and later for 12, years after their education finished,Footnote 70 and as stated by Braun, the Hautboisten educated at the Hoboistenschule were generally taught composition by Johann Theile (1646–1724) for two years during their apprenticeship.Footnote 71

Origins and provenance of German Hautboisten

Regarding the origins of the Hautboisten, Braun points to the earliest double-reed ensembles, evidence of which he claims first appeared in archival records at the court in Burgundy at the end of the fifteenth century.Footnote 72 In the Middle Ages these ensembles were made up of treble and alto shawms. Later, lower instruments were added, including the larger shawm instruments (tenor and bass). The bass shawm was replaced by the dulcian, the Renaissance forerunner of the bassoon, towards the end of the sixteenth century. Bernhard Höfele states that Friedrich Wilhelm of Brandenburg (known as the ‘Great Elector’, 1620–88) added a group of four shawms to the standard band of four drummers for each of his dragoon regiments. This group would have comprised two trebles, one alto and one bass instrument, and thus marks the beginning of the double-reed ensemble, which by the end of the seventeenth century had been established as the hautboy quartet. Höfele further claims that the earliest known source mentioning trumpets in use together with fifes and shawms in Brandenburg military music dates from 1620.Footnote 73 He also draws attention, however, to the fact that these double-reed bands were employed above all to perform for entertainment purposes and to represent the glory of their employer, whereas trumpeters, pipers and percussion players were primarily engaged in signalling duties for the military and at court.Footnote 74 Remnants of medieval double-reed ensembles can still be found in the vast variety of shawm-like instruments played by French and Spanish folk musicians.Footnote 75

The most successful versions of either family of Renaissance instruments – shawms for the top and inner parts and dulcians for the bass – were subsequently chosen for future development by instrument makers, and by following this traditional instrumentation of Renaissance double-reed consorts, at the end of the seventeenth century hautboys were chosen for the higher and middle parts, whilst bassoons provided the bass in a Baroque double-reed ensemble.Footnote 76 Thus one standard configuration for an hautboy band around 1700 appears to have been a quartet featuring two treble instruments, one alto (or tenor)Footnote 77 and one bass instrument. This allowed these ensembles to perform any music written in four parts, including works for two violins, one viola and bass, which in modern concert practice would normally be performed by a string orchestra and harpsichord continuo; however, many different instrumental combinations were possible for Hautboisten, as will be explored below.

Braun states that musical ensembles known as Hautboisten, Hautboistenbanden or Hautboistencompagnien were well established by the first half of the eighteenth century. He notes that in 1798, more than a century after the first hautboy bands were employed in German-speaking lands, these groups were still known by these names. Braun also explains, however, that by then they had evolved to become mainly large brass ensembles and normally the players were unable to perform on any type of oboe.Footnote 78

Indeed, the term Hautboisten remained in use until the beginning of the twentieth century, especially for German military bands: the Historischer Bilderdienst (an online archive of illustrations documenting military history, in particular uniforms),Footnote 79 provides reproductions of pictures of Hautboisten dating from the beginning of the twentieth century. In some of the images, percussion players are referred to as Hautboisten, which provides clear evidence that this had become the generic term for any military musician (see Figure 1). Thus, it appears to have been relatively easy for scholars, including Braun, to conclude that in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries Hautboisten had also generally been part of the military.

Figure 1. Anonymous, Musician (‘Hoboist, Lyraschläger’) of the Prussian Kaiser Alexander Garde-Grenadier-Regiment No. 1 (ca. 1910). Reproduced in Reinhard Quenstedt, ‘Alte Armee: Kesselpauker, Trompeter, Hautboisten’, Historischer Bilderdienst Website.

Braun believes it ‘is particularly difficult to describe the German hautboist because the documents referring to his existence – employment records like those often found for town pipers, cantors, organists, court musicians, trumpeters and drummers – are not usually available’,Footnote 80 a situation that would soon lead to frustration on the part of any scholar. He goes on to state that ‘a monograph devoted to them has not yet been written.’Footnote 81Hautboisten rarely appear on payrolls or similar lists, and most written evidence regarding non-regimental Hautboisten concerns disagreements between them and both the Stadtpfeifer and court musicians. Adequate research would therefore require considerable time spent in archives collecting data and, as the records on Hautboisten are scarce, Braun states that further collation of facts by any scholar would be a major achievement. Thus, the investigation of the Lilien Partbooks represented in this article is just one step towards a monograph on the subject of Hautboisten.

Despite the rather unaccommodating state of the primary-source material, Braun nevertheless attempts to categorize the different types of Hautboisten and the nature of their employment and duties. His chapter provides a detailed discussion of three main divisions: military; court; and town. Yet while this undoubtedly offers a basis for research in this field, each particular group still requires detailed research to be undertaken. Even establishing a clear differentiation between the Stadtpfeifer (town pipers), Hofmusici (court musicians) and Hautboisten seems to be a problematic task. The same group of players might have appeared in different situations under a different professional title, either as Hofmusici or as Hautboisten; indeed, some of them appeared with both titles in lists of courtly Kapellen.Footnote 82 Samantha Owens, for example, notes in her dissertation the existence of Hautboisten at the Württemberg court and provides information on their direct involvement with the courtly Kapelle.Footnote 83

Hautboisten in the military

Despite the fact that Hautboisten were often employed within military regiments, music that is nowadays considered ‘military music’ would rarely have been part of the Hautboisten repertoire. Even though each Hautboisten ensemble had its own march, similar in function to a national anthem, which was always dedicated to the highest ranked military leader of that particular regiment, the prevailing repertoire was for performance in the church, for concert entertainment (including Tafelmusik), and for music to portray the splendour of the general.Footnote 84

When Braun cites Johann Mattheson's complaint that every small principality employed poorly trained musicians who could also serve as lackeys,Footnote 85 he implies that such performers, likely Hautboisten, were held in low repute by the end of the seventeenth century, and had descended even further by the beginning of the eighteenth century. Clearly Braun's conception of Hautboisten was, first and foremost, as band musicians of minor talent. This did not indicate that they were players of signals, however, but rather that they were musicians charged with the responsibility of entertaining the general and his officers, brightening the soldiers’ moods and required to perform whenever music was needed. By the turn of the eighteenth century, signals relaying information to the soldiers during a battle were generally played by fifes and brass drums (tambours).Footnote 86 Beside his own categorization of Hautboisten as primarily military musicians, Braun suggests that their only connection to the military was the obligation to follow regimental orders and to be dressed in uniform.Footnote 87 As seen earlier, the musicians employed as part of the Écurie at the French court were administered by the military, a situation that was obviously not unusual in this period.

Braun concludes that Hautboisten were more interested in employment at courts than with the military,Footnote 88 largely due to the fact that a regimental Hautboist always risked losing his life on the battlefield.Footnote 89 Consequently, civic or court engagements seem to have been more desirable. One can assume that only the more advanced players gained a court appointment, with its attendant privileges, which in turn gives the impression that careers in military bands were inferior to those with the nobility and burghers.

One particularly important aspect of the category of regimental Hautboisten is the identification of the significance of French influence on military matters. This not only related to musical issues, but also impacted upon the terminology used at German courts more generally. Many aspects of general courtly ‘business’ appeared to have been organized in a military manner, even when not connected in any way to the army. For example, the Hofmarschall (court chamberlain) was the title allocated to the head administrator of the courtly household. The term Marschall might indicate membership of a military organization, and someone with a high rank in the army generally occupied this position, but a Hofmarschall’s job description in modern terms would equate more to a senior executive in the business world.

Compositions from the Lilien Partbooks can be taken as examples of music played by a band of regimental Hautboisten.Footnote 90 It seems plausible to assume that the Hautboisten employed by Friedrich von Wittenhorst-Sonsfelds's regiment, which also carried his name – ‘Regiment Sonsfeld’ – used this collection. Furthermore, it is likely that the players employed by this particular regiment would also have performed at the small Sonsfeld court, either just occasionally or perhaps as the sole provider of music at the court. If this is the case, these musicians were no different from the court musicians playing in ‘orchestras’ of the higher nobility. The discussion below, dedicated to the Lilien Partbooks in Sonsfeld's music collection, will attempt to clarify some of these assumptions.

Court and town Hautboisten

As noted earlier, Zaslaw and Spitzer demonstrate that members of the various ensembles at the French court also played different instruments, including players within the Grands Hautbois, for example, who were able to play string instruments and could be employed in several different configurations according to the type of music required on specific occasions.Footnote 91 With this in mind, Braun's explanation of the situation in German-speaking lands, after French musicians emigrated with their instruments to play and teach outside of their homeland towards the end of the seventeenth century, is unsurprising.

According to Braun, Hautboisten with French names appeared in Berlin from 1681 and were certainly teaching German musicians how to play this ‘modern’ instrument around this time.Footnote 92 Similarly, he refers to French Hautboisten in Celle (1681),Footnote 93 Bonn (1697) and Dresden (1699), dates that have been amended by Haynes’ research.Footnote 94 It seems plausible to assume that every major court in Germany employed a band of Hautboisten in the first half of the eighteenth century. Significantly, the French players employed at the court in Berlin in 1681 received the same salary as the ordinary court musicians and were obviously ranked at a similar level.Footnote 95 It is impossible to know, however, whether these players of the recently developed French hautboy were considered Hautboisten in the later German sense of the word – that is performers on multiple instruments – rather than as musicians who primarily taught and performed on double-reed instruments.

Employment in towns as Stadt-Hautboisten, as well as at court as Hof-Hautboisten, promised to be safer in nature than positions offered by the army. Since all towns regularly required music for a variety of occasions, this was certainly a secure place to work as a musician. Not only were the Hautboisten required by the town council for performance at official ceremonies, but they also provided music for church services, funerals, weddings and private festivities. Although Haynes claims that Stadtpfeifer and Stadt-Hautboisten were not the same and were, in fact, employed in different functions in towns,Footnote 96 this demonstrates once again that a problematic distinction existed between the types of work both groups engaged in.

The social status of Hautboisten

Later known as the ‘Soldier King’, the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm I, who commenced his reign in 1713, dismissed the entire court orchestra to save money immediately after he inherited the throne. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, Hautboisten were already so well established as part of the court music, as well as providers for military music, that his decision that all necessary court music was to be performed by the Hautboisten appears simply in accordance with common practice at those smaller courts in the Empire that did not have the financial means to support an orchestra.Footnote 97 The only novelty was his decision to order one trumpeter to join Prussian regimental Hautboisten bands. This order, nevertheless, was not to the liking of the trumpet players, who saw this move as a step downwards for them in the social order, as they had long been established members of the Imperial Guild of Trumpeters with their knowledge secretly guarded. The Prussian Hautboisten, on the other hand, rose in rank by playing with the king's trumpeters.

Although Braun states in his ‘Typologie’ that Hautboisten belonged on the lower steps of the social ladder, he also notes later that extant contemporary documentation fails to provide a single, clear categorization of their social status. He cites Johann Mattheson's reference on the one hand to an ‘exquisite hautboy band’ that he had witnessed in Hanover,Footnote 98 and on the other, Mattheson's complaints that every minor court expected to employ an orchestra for little money, with music of poor quality being the end result. Accordingly, the situation at the many other German courts will need to be investigated in future research, since Braun also states as an example that the Hautboisten at the court of Saxony-Weissenfels around 1700 were ranked immediately below the trumpeters, which makes them a rather privileged group of musicians at that particular court, similar to their ranking in Prussia;Footnote 99 yet, having established this picture of Hautboisten as highly regarded musicians, he also refers to ‘the same court (Saxony-Weissenfels) as well as to the court in Zeitz, where the instrumentalists indeed also served as lackeys’.Footnote 100

In a source dating from 1696, Braun indicates that sometimes wind players were not allowed to play string instruments in public, a prohibition that he takes as evidence that they were regarded as lower in rank than string players.Footnote 101 It seems more likely, however, that this source deals with disputes originating from different musicians enviously guarding their employment territory. Braun clearly believed that a Baroque musician's ultimate ambition was to gain a position as a court musician; an Hautboist perhaps started as a military player, later working as a town Hautboist, subsequently being employed as a court Hautboist and finally being appointed a Hofmusicus. His assumption that ‘a large number’ of Hautboisten were ‘disappointed human beings who were more or less deceived in their life expectations’ seems more than a little overstated.Footnote 102

Clearly thinking along similar lines, Braun concludes that the duties of the Hautboisten, apart from those that comprised music making, demonstrate that they had a lackey's status rather than that of an artist. He outlines the duties of Hautboisten employed at the court of Saxony-Zeitz around the end of the seventeenth century, as follows:

… they accompanied their sovereign on journeys, led the processions of the court on either oboes or violins, played violins for an hour before the evening meal outside the rooms of the Duchess (Jan. 17, 1692), carried sauerkraut and bratwurst to the hunt (Oct. 14, 1698), played to the good health of a court official at his wedding, played minuets along with other pieces at a dance (Feb. 21, 1693), and played a courante for the performance of a tightrope walker and his wife (Aug. 15, 1696). From a socio-historical point of view, the hautboist can be placed somewhere between the peasant musician and the real court musician.Footnote 103

The concept of early-modern musicians being free from any obligations other than performing music seems to be, in any case, a romanticized idea that bears more in common with nineteenth-century notions of the profession, and the fact that Hautboisten were multi-instrumentalists does not render the classification of these ensembles as anything unusual.

The fact that Braun regards the Hautboisten to be of low status at court seems to be at odds with his earlier statement that they were second only in rank to the trumpeters at the court in Saxony-Weissenfels. Nevertheless, assuming that appointments at major courts were better paid than those with the military, it is understandable that musicians were naturally interested in applying for court positions. As mentioned before, a courtly life would have involved a considerably more comfortable lifestyle than life on the battlefield; however, an examination of the wages of different military musicians reveals that Hautboisten were consistently regarded as more highly ranked within the military than any other group of musicians the military employed – for example, the players employed solely to provide signals.Footnote 104

Given that Haynes refers to a total number of 1,266 military musicians in the Prussian Army in 1713,Footnote 105 and taking into account the large number of minor courts in the German-speaking lands around this time, one can estimate that there were vast numbers of Hautboisten employed in various positions during the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Daily musical life at courts and in towns, as well as in the army, would simply not have been possible without their skills. The many different options for their employment as outlined above also indicate that their social ranking must have been as wide-ranging as their working environments.

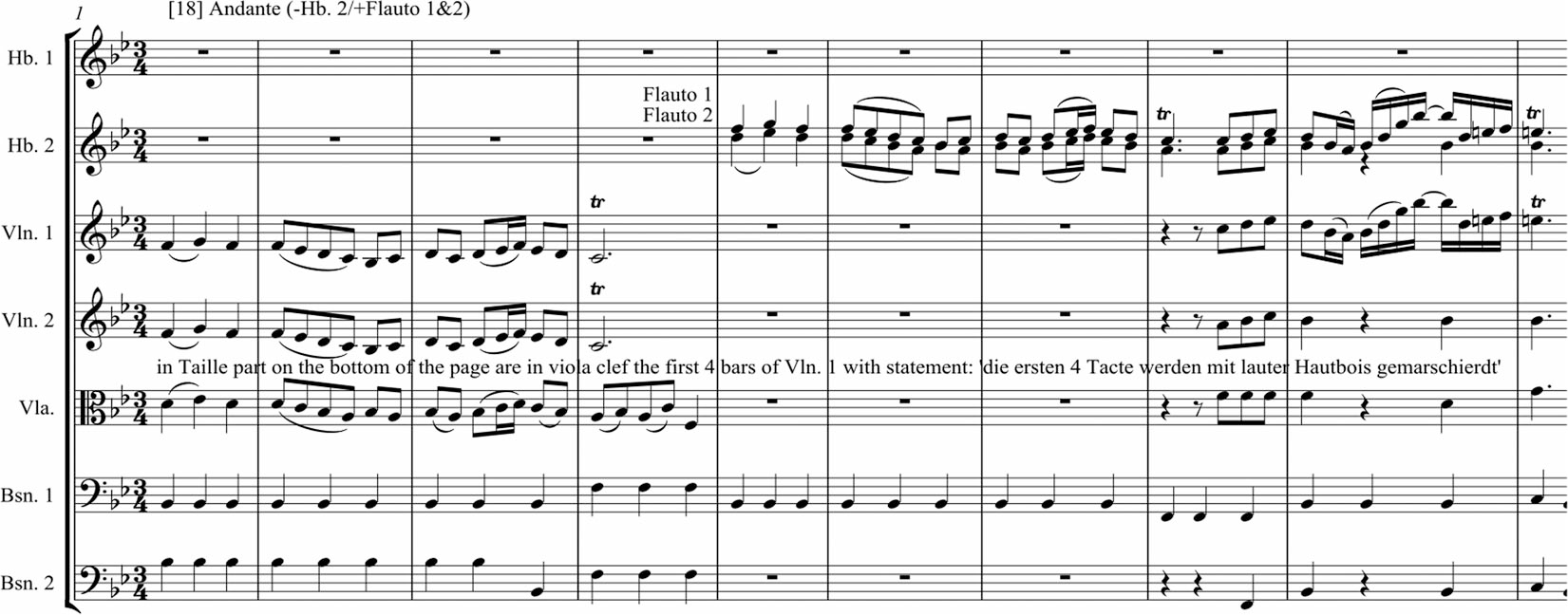

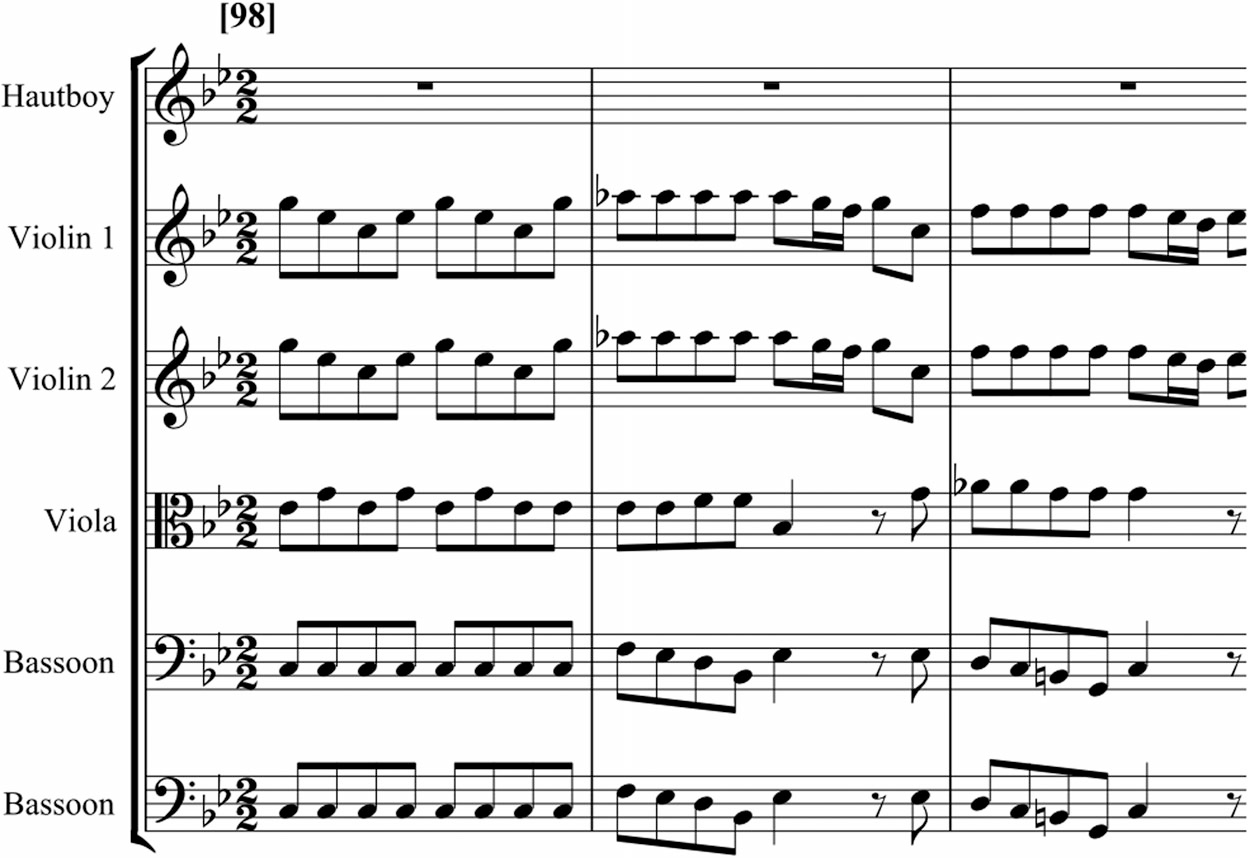

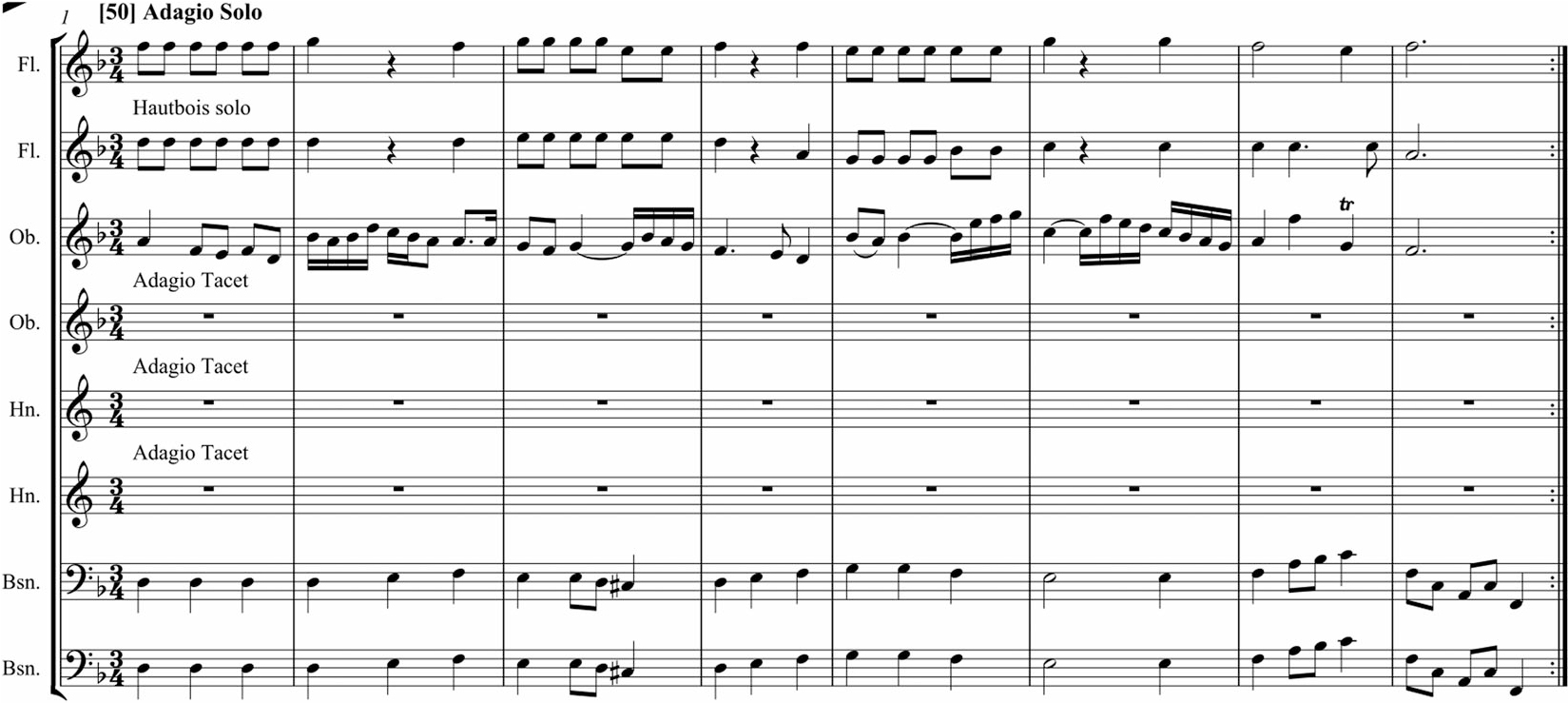

Hautboisten music

Citing Johannes ReschkeFootnote 106 and Peter Panoff,Footnote 107 Braun believes that music for Hautboisten was, initially, composed in three parts. Unfortunately, it is not clear whether he is referring to repertoire composed during times prior to the Baroque era, and therefore still for instruments of the shawm family, or works composed during the period after the structural changes of the instrument. Certainly, the alta capella, the early shawm band of the Middle Ages, and hence the forerunner of the Hautboisten band, had generally played music in three parts.Footnote 108 As Braun does not provide any musical examples for the period he investigates, and given that his information is drawn from secondary sources dating from the early twentieth century, the contents of the Lilien Partbooks assume even greater importance. Contrary to Braun's assertions regarding music for Hautboisten, the music in the Lilien Partbooks is in fact generally in six parts, with numerous exceptions of works in even more parts as well as some with fewer parts.Footnote 109

Braun describes the trios (scored for two hautboys and one bassoon) in Jean-Baptiste Lully's operas as a three-part double-reed ensemble, and goes on to conclude that these represent the origin of the wind section in the modern symphony orchestra. Whilst in some senses this may seem to be a valid conclusion, it has been suggested that these parts may have been played by a consort consisting of more than three players, rather than a trio of soloists joining an existing string ensemble. Haynes, for example, states there were 21 woodwind players and 47 string players involved in Lully's first production of Le triomphe de l'Amour in 1681.Footnote 110 He also explains that ten of these woodwind players performed on double-reed instruments. Assuming that these ten musicians would have been divided into the four parts stipulated in the score, a possible instrumentation may have been: three first hautboys; two second hautboys; two taille de hautbois; and three bassoons. Consequently, it seems plausible to assume that there may have been (as one of several possible instrumentations) more than one player per part for Lully's double-reed trios.Footnote 111 Additionally, Spitzer and Zaslaw's description of large festivities with combined wind and string ensembles seems to lead only to their conclusion that Lully's trios may have been performed by ‘two oboes and bassoon, perhaps doubled, perhaps not’.Footnote 112

Braun's conclusion that these ensembles had always been regarded as independent ‘choirs’ is, nevertheless, of major value. It opens up a field of research focusing on the music that Hautboisten ensembles played by themselves, as well as on a reconsideration of much music that at present is generally classified as ‘orchestral’ music. Future investigation is needed regarding the possibility that a number of ‘orchestral’ pieces were, in fact, written for several distinct ensembles of instruments. Compositions such as Bach's Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 and Telemann's overture suites for three hautboys, one bassoon and strings come to mind.

Braun believes the taille de hautbois to have been in a, while the oboe da caccia in f (which he also mentioned) – a curved instrument with a brass bell – was in fact only a solo instrument and, furthermore, is almost exclusively found in cantatas by J. S. Bach. Yet the results of research undertaken by Eric Halfpenny, together with analysis of extant music, demonstrate that it is more likely that a normal Hautboisten quartet would have comprised two hautboys in C, one taille de hautbois in f and one bassoon.Footnote 113

The taille – the direct forerunner of the cor anglais – was an ensemble instrument and provided the middle part, akin to a viola in a string quartet. Knowledge of the range of the instruments in such an ensemble is clearly of utmost importance when attempting to identify whether a composition was possibly intended for winds rather than strings, as the wider range of both the violin and viola allows performance with hautboys and bassoons to be ruled out when the music cannot be realized on these instruments. Fleming claims in his 1726 publication that both middle parts of a four-part composition were generally performed on the taille de hautbois in double-reed bands;Footnote 114 however, iconographic evidence provided by Halfpenny, as well as information on instrumentation found in manuscript music and printed editions from the seventeenth century, appear to support the opinion that only the lower middle part was performed on a taille de hautbois.

In his paragraphs dealing with specialized music for Hautboisten, Braun identifies several connections such repertoire has with other music genres of the time.Footnote 115 Although one might most readily consider wind bands to have been providers of outdoor entertainment music, he also points out their importance in church music, such as cantatas and motets. Amongst others, J. S. Bach, for example, clearly wrote for Hautboisten, as can be seen in the instrumentation of his motets.Footnote 116

Another genre of music that Braun believes was of importance for Hautboisten is the Tafelmusik (dining music) customarily performed at courts. It is worth noting that surviving collections of Tafelmusik from this era feature diverse instrumentation and the music is often of very high quality and difficulty – as, for example, Georg Philipp Telemann's Musique de table (Hamburg, 1733). If the performance of such music was indeed a typical part of the daily work of Hautboisten, then it is a very strong indicator of an advanced standard of playing, even though Braun describes this repertoire as Gebrauchsmusik (utility music) – that is, music for entertainment purposes, rather than as ‘high art’.

Given that by the end of the eighteenth century and during the nineteenth century wind band music was generally regarded as light and ‘easy to play’ entertainment, we must question how much of Braun's bias, as a scholar writing in the twentieth century, influenced his thoughts regarding groups of musicians whose traditions were derived more directly from the wind-instrument playing of the Middle Ages, and whose origins and professional development have been highlighted earlier. The questions asked at the beginning of this section recur throughout this entire article, albeit from different perspectives. For example, were the Hautboisten really an insignificant group of musicians (as some authors have suggested), whose existence was a mere adjunct to the ‘real’ music performed by court Kapellen? Or is the development of the orchestra the exception here, but one that in the following centuries happened to become the norm and subsequently the major musical institution? Is there really so little ‘art music’ for Hautboisten remaining?Footnote 117 And can the Lilien Partbooks in particular help our understanding of these groups and their music?

In order to be able to answer some of these questions, the following sections of the article will shed light on a small variety of relevant compositions. An analysis of printed music intended for performance by Hautboisten alone, alongside a discussion of the information found in original dedications and prefaces, will provide the body of knowledge necessary for the subsequent analysis of manuscript music. Details on the history of music for Hautboisten in Prussian lands during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries will be the focus of the beginning of part 4, thus providing important background knowledge for the subsequent examination of the Lilien Partbooks.

Part 3. Music for Hautboisten

Hautboisten were employed as military, court, municipal and freelance musicians. In any of these positions, their duties might include involvement in sacred music, both performing in elaborate cantatas with independent instrumental parts and playing in unison with the singers when performing motets,Footnote 118 providing music for ceremonies such as weddings and consecrations, and marching with muted hautboys in front of mourners in funeral processions.Footnote 119 Among other duties, their secular performances consisted of providing music for the visits of important guests to courts or towns, playing Tafelmusik and entertaining whenever music was needed. As a result of these numerous options for employment, and also because of their extensive education on multiple instruments (see earlier), the repertoire performed by Hautboisten included a vast variety of different types of Gebrauchsmusik (utility music, or music composed for a specific purpose, such as dancing). This diversity, however, makes it a challenging task to identify which music is specifically written for Hautboisten.

While there still seems to be a gap regarding our knowledge of the typical repertoire played by these groups when supplying music for entertainment, significant research on the musical activities of regimental musicians, including military Hautboisten in Prussia during the eighteenth century, has been undertaken by Achim Hofer,Footnote 120 Peter C. MartenFootnote 121 and Sascha Möbius.Footnote 122

As part of his findings, Marten published marches for the different regiments of the Alt-Preussische Armee (that is, the Prussian Army prior to its defeat by French-backed forces in 1806–7). Most facsimiles of manuscript copies of marches and musical signals provided in Marten's volume date from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and feature only a single melody line, although occasionally there is also a part for a second treble instrument and even for drums. Fife players (Spielleute) are the focus of this first volume of his research (a planned second volume has yet to be published); nevertheless, Marten's introductory chapter contains information on Hautboisten. Recalling previously mentioned information that the leader of every band of Hautboisten was required to be able to compose as well as to arrange music, it can be assumed that they would have added other parts such as a second hautboy, a bassoon and perhaps brass to these pieces, as can be seen in existing marches composed by Johann Georg Christian Störl (1675–1719),Footnote 123 the Prussian Princess Amalie (1723–87)Footnote 124 and numerous others, which have parts for 2nd hautboy, bassoon and brass.Footnote 125

Whereas Marten investigates music for fifes, Möbius's article provides information regarding hymns played by Prussian Hautboisten whilst marching into battle.Footnote 126 These were presumably performed with the specific aim of raising the soldiers’ morale, although the atmosphere created by such sacred tunes might also have been intended to give the enemy a shiver of fear and demoralize them, in the same way Scottish bagpipes were used in battle. Military Hautboisten are also known to have performed first aid and certainly had a dangerous life in times of war, as can be seen, for example, by the large number of deserting players in the year 1714.Footnote 127

Whilst music performed by military Hautboisten was clearly important for providing both strategic and morale-boosting messages, it was also required off the battlefield for entertainment for the officers. Likewise, Hautboisten employed by town councils or at courts played signals such as music for curfew calls; however, these duties were only a minor part of their work and by the beginning of the eighteenth century many were freed of these obligations, as they had become increasingly occupied with other responsibilities.Footnote 128

It is important to mention that Achim Hofer challenges Möbius’ statements in a publication on Prussian military music.Footnote 129 Hofer claims that there is a lack of evidence of Hautboisten ‘marching’ into the battlefields and continues to argue that written records are unclear and contradictory. His doubts will need to be considered in future investigations, and will possibly necessitate updates to the summarized current knowledge presented here.

Whereas research on regimental Hautboisten may provide important information regarding the lives of musicians in the military, as well as supplying possible insights into the types of music performed by these groups in a wider context, investigation beyond the regimental realm offers further material on other aspects of the daily musical life of Hautboisten in the eighteenth century. The fact that they routinely provided entertainment such as Tafelmusik, for example, requires investigation into an extensive repertoire, which at first glance does not seem connected to Hautboisten. The following investigation of contemporary music dedicated to Hautboisten will provide us with a platform for the subsequent discussion of the Lilien Partbooks.

Early publications

Questions arise as to the typical instrumentation of a band of Hautboisten in the early eighteenth century, the occasions upon which they performed, and, last but not least, how to determine whether a composer had Hautboisten in mind when writing a particular piece of music. Two extant early publications will be investigated in the following paragraphs. This discussion will contribute substantially to the background required when determining what was considered ‘typical music’ for Hautboisten, and will therefore be crucial to answering some of the questions posed in this article.

Johann Philipp Krieger – Lustige Feld-Musik

A collection of the utmost importance for this research is the Lustige Feld-Musik of Johann Philipp Krieger (1649–1725), a collection that comprised six overture suites and was published in his birthplace, Nuremberg, in 1704. Krieger travelled extensively throughout Europe for his education, including study in Italy, Copenhagen, Holland and also Stuttgart. He worked for the courts in Bayreuth and Halle, and, for 45 years, from 1680 until his death in 1725, was Kapellmeister at the Saxon court in Weissenfels.Footnote 130

In Harold E. Samuel's entry on Krieger in Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart, the Lustige Feld-Musik is listed among the composer's extensive output under the heading ‘orchestral works’. Samuel discusses this collection alongside the publications of Johann Sigismund Kusser (Composition de musique, 1682; Apollon enjoüé, 1700) and Georg Muffat (Florilegium primum, 1695; Florilegium secundum, 1698) as examples of orchestral overture suites. Derived from collections of dance movements of French operas from the second half of the seventeenth century, the orchestral suite soon became an archetype of German composition of the beginning eighteenth century. Steven Zohn suggested that Georg Philipp Telemann took this form to its climax.Footnote 131

Muffat's works are clearly composed for a five-part string formation with hautboys and a bassoon added ad libitum instead of the concertino string group of two violins and a string bass. In the prefaces to Muffat's two collections (both printed in Passau), he explains the manner in which this French-style music should be performed, providing, in the process, important information on Jean-Baptiste Lully's performance practices. Muffat's compositions feature a typical instrumentation of two violins, two violas and bass; however, he also notes that in performances these suites can be adapted to the needs of the available musicians. The minimum-sized group would be a trio of two violins and a bass, whereas the most common ensemble would be one-per-part and basso continuo.Footnote 132 Any larger number is also possible according to Muffat, and he further states that: ‘If some of your musicians can play the French oboe or the shawm well, you can form the concertino or trio with two of the best of these instead of the two violins, and with a good bassoonist instead of the small bass…’.Footnote 133 Muffat's suggestion of the use of a concertino of clearly three players seems at odds with Haynes’ proposed possibility of doubling the parts in Lully's trios which was mentioned above. Future investigation needs to clarify whether these are possibilities or rules, whether one automatically excludes the other, and whether there may have been differences in performance practice in France and in German-speaking lands.

Whilst the typical French scoring in five parts was introduced into the German-speaking countries by Kusser and Muffat, and thereafter also copied by composers such as Philipp Heinrich Erlebach (1657–1714),Footnote 134 who never went to France, Lully's music would usually have been scored for one violin, three violas and bass (labelled dessus de violon, hautecontre, taille, quinte and basse de violon) rather than two violins, two violas and bass, as found with the German masters. Krieger's Lustige Feld-Musik is distinctly different. In common with all typical French-style ‘orchestral’ suites by German composers, the six works in his collection start with an overture followed by a number of dances; however, the instrumentation is in four parts rather than in five. For the double-reed band at the French court, the Douze Grands Hautbois, Lully scored in four parts when they performed together with the strings, omitting the lower viola part.Footnote 135 Since German composers continued to copy the typical French instrumentation for strings in five parts more than a decade after Lully died, this might suggest that the four-part set-up for Hautboisten was also in imitation of the common practice of omitting the second viola part when performing on double-reeds, as was shown, for example, in Kusser's instrumentation of his Adonis, and, furthermore, underlines the fact that Krieger had a wind band primarily in mind for his Lustige Feld-Musik rather than a string orchestra.

Unfortunately, no original print of Krieger's collection has survived. Therefore, our current knowledge must rely on editions of three of the six overture suites in secondary sources. To name the most important source, Robert Eitner's 1897/98 article in the Beilage zu den Monatsheften für Musikgeschichte not only offers the music of two of the six suites, but also includes a transcription of the invaluable preface of the original publication, in which information on potential customers and the collection's instrumentation can be found.Footnote 136 The overture suites in this collection are similar to other pieces of the same genre played by any Hofkapelle (court orchestra) during that period, and therefore provide essential information about the musical repertoire of Hautboisten.

Dedicated to the Nuremberg collegium musicum, the title page of Krieger's collection reads as follows:

| Johann Philipp Kriegers | Johann Philipp Krieger's |

| Lustige Feld-Musik, | Auf vier blasende oder andere Instrumenta gerichtet | welche zu starkerer Besetzung mehrfach, | Nemlich Premier Dessus dreyfach, | Second Dessus zweyfach, | Taille einfach | Basson dreyfach | gedruckt sind. | Zur Belustigung der Music Liebhaber und dann auch zum Dienst derer an | Höfen und im Feld sich aufhaltenden Hautboisten | herausgegeben Nürnberg | In Verlegung Wolfgang Moritz Endters. | Gedruckt bey Johann Ernst Adelbulner. | (1704). | Merry Field Music, set for four wind or other instruments, [and] which for a larger ensemble multiple parts are printed, namely three for the first treble, two for the second treble, one for the taille Footnote 137 and three for the bassoon. For the entertainment of music lovers [amateurs], and also to serve those Hautboisten employed at courts and on the [battle] field. Edited and published in Nuremberg by Wolfgang Moritz Endters. Printed by Johann Ernst Adelbulner. (1704). |

In his preface, Krieger explains the finer points of the work's instrumentation and intended purpose:

| Der Bass zum Cembalo ist darum beygefüget worden, damit diese Partien auch von wenigen Liebhabern mit Geigen können musiciert werden. | The bass for the harpsichord has been added so that small ensembles of amateurs also can perform these suites with violins. |

| Weiln der Setzer theils Zahlen verschoben und theils unrechte Zahlen gesetzet, so hat sich der Cembalist nicht an solche zu binden, sondern das Accompagnement nach dem Gehör zu richten. | Because the typesetter has both shifted figures and set incorrect figures, the harpsichordist should not depend on them, but create his accompaniment by ear. |