In a letter to Mersenne, Giovanni Battista Doni wrote of his contemporary Girolamo Frescobaldi that ‘all his knowledge is at the ends of his fingers’.Footnote 1 While acknowledging Frescobaldi's ability to compose fantasies and dances, Doni's comments capture a fundamental tension emerging in instrumental music of the early seventeenth century. Doni, unlike a practising musician, was immersed in the literate world of the Republic of Letters – an environment where information conveyed in writing had an authoritative status. His low opinion of Frescobaldi, based on the composer's apparent lack of theoretical prowess, suggests that he was unable to comprehend fully the working practices of an instrumental musician deeply embedded in unwritten compositional procedures that were realized first and foremost in sound. His comment represents in many ways the collision of two worlds at a crucial juncture in the history of instrumental music and of keyboard music, in particular, as it emerged from an oral-aural past, becoming not just a written, but a printed, repertory. Frescobaldi himself suggested in the dedication of his first book of toccatas addressed to Ferdinando Gonzaga, that the music presented in the book was created at the keyboard.Footnote 2 His note, addressed to the reader (al lettore) who must be the performer and not a silent reader for it to make sense, indicates his own awareness of the tension between the performative or artisan aspects, and the literate or representational elements in his music as he presents it to a reading rather than listening public. Although we can learn compositional rules from various performance manuals, some of which will be discussed below, paradoxically, it is only music that has survived in writing that can provide us with concrete evidence of how unwritten traditions or practices might have been woven together into larger musical structures.

Keyboard music preserved in a printed format perhaps suggests that as instrumental music emerged as a literate culture, it gradually acquired greater commercial value. The market for printed instrumental music before 1600 was dominated by lute tablatures, and keyboard music was slower to appear, and, even then, in a limited range of genres.Footnote 3 The keyboard toccata, which routinely used a large quantity of small note-values as well as textures that were not restricted to four equal voices, was particularly unsuited to typesetting. A strong manuscript tradition for keyboard music continued long after the introduction of the printing press, perhaps because of the incompatibility of the printing process with the genres associated with keyboard performance and composition.Footnote 4 Whatever the reasons for printing music that had long been the domain of the performer-composer, both Judd and Boncella have noted that genre and notational formats were inextricably linked.Footnote 5 Frescobaldi's decision to publish his toccatas, and his choice of printing by means of engraving rather than type, seems to have been carefully considered. Cypess has suggested that the Toccate e partite…libro primo was published with a specific function in mind, and that it can be read as a pedagogical text for the stil moderno.Footnote 6 A different view has been posited by Silbiger who takes an overview of the 1637 reprints of both the Libro primo and the Secondo libro di toccate which were issued at the same time. He suggests that they were Frescobaldi's attempt at creating a definitive edition of his own work.Footnote 7 Whatever the composer's motives for publication, what is clear is that these books mark a point of transition from the genuinely performative ‘improvisation’ that was composed mentally and not written down, to the apparently ‘finished’ composition, notated in some detail to mimic improvisation. Further, they indicate that the composer recognized the gap between the notation and what the original unwritten performance might have sounded like, providing the verbal instructions in his prefaces as an attempt to bridge that divide. The notation ‘freezes’ a version of a composition, the genesis and essence of which remained performative. It thus creates a repository from which we can extract and unravel some of the unwritten strategies of the composer at the keyboard.

The term improvisation in the early-modern context incorporates a range of unwritten composition techniques: singing one or more additional parts to a cantus firmus; singing imitative counterpoint in several parts; the spontaneous creation of embellishments and variations by single-line instrumentalists and singers on existing melodies; responding on the organ for specific liturgical needs; and so on. With regard to the organ, Banchieri identifies four ways of playing – fantasia, intavolatura, spartitura and basso seguente – all of which imply improvisation to a greater or lesser extent, but fantasia, or the playing of counterpoint, is accorded highest status.Footnote 8 Recent research has demonstrated that the term ‘counterpoint’ in Renaissance and Baroque treatises means ‘improvised counterpoint’, or what Zacconi called contrapunto alla mente.Footnote 9

With reference to the keyboard, improvisation implies more than the unwritten mental working out of voices in counterpoint, because it is also a physical act in which the capacities or limitations of the performer's hands and instrument play a part. Cypess, drawing on the work of Gauvin, uses the term habitus to describe the instrumentality or physicality of the creative, performative process of composers of instrumental music of the early seventeenth century.Footnote 10 Guido, Schubert, Bellotti and others have demonstrated that contrapuntal improvisation at the keyboard was a learned skill, acquired through methodical practice at the keyboard over long periods of time, as well as through memorization of contrapuntal rules and patterns of voice-leading and embellishment. All of these skills were developed through performance.Footnote 11 Memory and delivery were elements of rhetoric and were embedded in learning and teaching practices, which started with repetition and memorization, progressed to imitation of models drawing on materials already learned, and culminated in delivery or performance.

Unwritten traditions were not and are not confined to musicians. The early-modern period was still, to a large extent, an auditory rather than a visual culture. This does not necessarily indicate illiteracy, though levels of functional literacy were quite variable. To inform the analytical methodology used here, I have drawn on the work of scholars who have studied sound and listening, auditory cultures, and the long-standing traditions of oral poetry stretching back to Homer.Footnote 12 Orality in the early-modern period was multi-dimensional, and its complexity is reflected in the range of surviving evidence and, indeed, in the scope of literature on the subject that covers a range of disciplines. In this article, the term ‘oral composition’ is preferred over the more common ‘improvisation’ in order to capture all aspects of unwritten composition including counterpoint; single-line melodic diminutions and more complex embellishment; memory skills including theoretical aspects as well as the tactile or kinetic elements of habitus; and the combinations of techniques used at the keyboard in the repertory under discussion.

This article will use a selection of keyboard toccatas written in intavolatura rather than score format, and Frescobaldi's output as a primary, though not exclusive, point of reference. As my analyses rest to an extent on statistics, the choice of a single genre notated in a specific way ensured that numerical comparisons could not be affected by generic or notational differences. This does not necessarily mean that conclusions drawn from the analyses of toccatas are not applicable to other genres such as canzoni or partite or to toccatas for other instruments such as the lute. I have chosen c.1615 as my starting point to include the creation and publication of Frescobaldi's Toccate e partite…libro primo. This excludes the Neapolitan publications of the toccatas of Mayone and Trabaci which were printed in partitura format rather than in intavolatura. By doing this I do not imply that they were not of importance in informing the development of the toccata as a genre, but to ensure that my analyses were comparing like with like. I have also largely excluded the toccatas of Merulo, for stylistic reasons which will become clear in my discussion below.

My analyses will be situated within a framework of theoretical and documentary evidence that describes oral composition in various pertinent contexts contemporary with the music. These sources provide the evidence for an argument that will enlarge our understanding of an unwritten tradition that was still an ongoing part of the working musician's life well into the first half of the seventeenth century. In so doing it will also challenge the use of partial concordance of sources as one of the primary ways in which ascription of authorship is made in this repertory.

Oral composition: an overview

In the early-modern period the relationship between music as sounding number in a philosophical sense, music practised creatively as a sounding reality, and the complexities of music notation was intricate and operated on multiple levels. The inability of music notation to project the sounding reality of performance is evident in many sources. Vicentino, for example, in discussing performance gives advice about sharing diminutions around the singers and instrumentalists in a group, and goes on to state that

sometimes a composition is performed according to a certain method that cannot be written down, such as uttering softly and loudly or fast and slow, or changing the measure in keeping with the words, so as to show the effects of the passions and the harmony.Footnote 13

The echoes of classical rhetorical texts by Quintilian and Cicero are recognizable, and Vicentino continues his advice by referring his reader to the practices of the orator. Prefaces to music by Peri, Caccini, Frescobaldi, Marini and others all offer advice to the performer that indicates a relationship between sound and notation that might be described as non-linear, with the flexibility of performance being more akin to the verbal modes of rhetorical delivery.Footnote 14 There is evidence also that those engaged in verbal delivery, such as preachers, were pointed to musical models for shaping their own performance.Footnote 15 The fluid relationship between the written word and the voiced text, and reception of text as heard rather than read, have clear parallels in instrumental music.

Some components of unwritten practices are easier to understand if not to recreate in practice. The way in which a piece of music as a whole was structured conceptually during the process of improvised composition remains difficult to evaluate. Jessie Ann Owens's research into how composers worked in the sixteenth century, and Rebecca Herrisone's work on concepts of creativity in Restoration England, have made significant progress in unravelling some of the complexities, but there is still a great deal that remains to be discovered and understood, especially as applied to specific repertories.Footnote 16 In comparison, the rules of melodic embellishment, of counterpoint, and for playing from a bass line are all described in greater or lesser detail in a variety of treatises, the most important of which, for the purposes of this article, are those by Diruta, Banchieri and Spiridion a Monte Carmelo.Footnote 17 The two areas on which my analyses focus are melodic embellishment and diminution practices and combinatorial processes of counterpoint. While this material is discussed in the literature, some points germane to the analyses which follow are worth noting.

A variety of surviving performers’ manuals provide instructions on how to embellish existing melodies. That this was done without necessarily having a notated original is evident from early sources such as Ganassi's Opera intitulata Fontegara (Venice, 1535)Footnote 18 in which simple intervals are the building blocks of an ever-increasing density of notes. The complex multi-note patterns that emerge may ultimately ‘represent’ just one interval. Florid embellishment is of course a given in the ‘new music’ of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century; however, the handbooks of Ortiz (1553), Sancta Maria (1565) Dalla Casa (1584), Bovicelli (1594), Conforti (1601, 1607) and others all suggest that a rich tradition of embellishment existed long before it appeared in the printed outputs of Caccini and his contemporaries.Footnote 19 The techniques of embellishment outlined by these authors are fundamentally similar, in that they require the performer to identify the interval to be embellished, the temporal distance between the two notes that create that interval, and the number of notes required to fill the space thus identified. Decisions concerning temporal distance and number of notes to be used will determine the level of virtuosity required. The requirements for single-line instruments and keyboard instruments are essentially the same. The examples of vocal gorgie in Zacconi's Prattica di musica provide further examples of longer passages of embellishments.Footnote 20 The function of vocal gorgie too, parallels the diminutions expected in instrumental performance, to enrich the performance and to create meraviglia in the listener.

The lists of diminution patterns for each interval that may be extracted from these books suggest that a repertory of formulae was learnt by instrumentalists as part of the ‘stock in trade’ of performing. While this sort of feat may seem strange to modern ideas about composition, the concept of copia was well established in early-modern education. It was part of the study of rhetoric, the fundamentals of which were central to creative processes of the early-modern period. The idea of successively embellishing, enriching and amplifying passages drawn from classical authors was embedded in the teaching of Erasmus, and inspired by the revival of the works of Quintilian and Cicero.Footnote 21 It is easy to see the relationship between Erasmus's 200 variations on a single sentence in De Copia and the multitude of amplifications of musical intervals presented in performance manuals. Ganassi, for example, directly echoes Erasmus's virtuosic variations by providing 175 variants of a six-note cadence pattern.

That memory also played a key role in oral composition is indisputable. Lorenzetti has shown that in the sixteenth century concepts of fantasia were related to memory and rhetoric as well as to imagination.Footnote 22 Roger North, though writing somewhat later, indicates explicitly that musicians relied on their memories of common musical patterns:

his memory will be filled with numberless passages of approved ayre, and have ad unguem all the cursory graces of cadences and semi-cadences, and common descants, and breakings, as well as the ordinary ornaments of accord, or touch…. It is not to be expected that a master invents all he plays in that manner. No, he doth but play over those passages that are in his memory and habituall to him. But the choice, application, and connexion are his, and so is the measure, either grave, buisy or precipitate; also the severall keys to use as he pleaseth… Footnote 23

Studies of Medieval and Renaissance mnemonic practices indicate that from at least the ninth century memory skills were methodically learnt.Footnote 24 Even though we do not know precisely how a young musician would have been taught, it is highly likely that even in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, whether a choir boy or instrumentalist, he would have been expected to memorize large quantities of musical material. This might have included theoretical concepts; chants with their associated intonations, reciting tones and conclusions; the order of antiphons and psalms; and so on. The pages of contrapuntal rules, diminution patterns and cadences found in instrumental treatises were, in all likelihood, designed to be memorized so that they could be drawn on at will in different improvisational contexts.Footnote 25

Guido has demonstrated that the method of teaching diminutions for keyboard instruments outlined in Diruta's Il transilvano embeds fingering patterns in memory, and that the same sort of passages may be used in improvising contrapunto di note negri (counterpoint that requires multiple notes for each note of the cantus firmus).Footnote 26 While small-scale, specially written examples of toccatas are included in the treatise to convey his method, and further evidence of larger-scale pieces that match his miniatures is provided in the printed toccatas of Merulo, I will demonstrate below that with reference to toccatas from outside the Venetian area, Diruta's statement that ‘toccatas are all diminutions’ deserves further scrutiny.Footnote 27

It was not until the 1670s that reference to existing printed repertories is made in connection with embellishment practices. Spiridion, in his Nova instructio, uses reference to extracts from Frescobaldi's printed books as examples rather than teaching his techniques through purely theoretical methods that needed to be mastered through constant practice.Footnote 28 These were probably also intended to be memorized as models from which to develop new ideas. The eventual appearance of reference to printed repertories rather than specially written examples mirrors the emergence of references to printed vocal works in theoretical treatises in the late sixteenth century.Footnote 29

Harmony, too, could be composed mentally using a variety of formulae, though these are less evident in the theoretical literature when it comes to groups of instrumentalists. Van Orden has found evidence suggesting that in mid-sixteenth century France singers harmonized chansons in thirds and sixths, while the earliest treatises on playing the trumpet indicated harmonization at a step distant in the harmonic series as a required performance technique.Footnote 30 In relation to a slightly later period, Menke has found that early Baroque composition has parallels with earlier polyphonic strategies and that structures based on alternating thirds and fifths between outer voices provide a secure skeleton for unwritten practices including basso continuo.Footnote 31 If at least one given part was present, there was a range of strategies available to the keyboard player to creatively work out more complex textures.

Counterpoint during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries meant primarily mental counterpoint – a skill that was learnt by every choir boy and governed by strict rules.Footnote 32 It was practised at all levels of society and by singers and instrumentalists alike, as even the artisan classes sang sortisatio, a kind of orally composed polyphony.Footnote 33 Well into the seventeenth century, knowledge and skill in counterpoint is the most important attribute of the ‘perfect musician’ cited in a letter from cornettist Luigi Zenobi to his patron.Footnote 34 The evidence of tests for applicants for musical posts such as organist at St Marks in Venice or Maestro di Cappella at Toledo Cathedral, though geographically diverse and fragmentary, indicates that the professional musician of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century was expected to have extraordinary abilities in unwritten composition and performance.Footnote 35

While the reports of the skills of early-modern musicians may well be exaggerated in order to reflect the superior tastes of a patron or institution, their skills may be learned today. Schubert has distilled the elements of a number of counterpoint treatises into a modern guide for students of counterpoint, and together with Guido, has demonstrated that strict counterpoint in the form of the ricercar was frequently composed ‘at the keyboard’ as a practised technique. It seems highly likely that short bursts of contrapuntal activity within the otherwise free texture of the toccata would have been similarly composed.Footnote 36 The performed composing out of an accompaniment up from a given bass line in early basso continuo accompaniment is also mental counterpoint and provides an additional window on the improvisational skills of the performer.Footnote 37 Banchieri's addition of a ‘quinto registro’ to the 1611 edition of his L'organo suonarino, explaining how to work from a bass line, is testimony to the need for working keyboard players to acquire this skill, even if they were unable to produce complex polyphony.Footnote 38 While composing up from a bass line was evidently an increasingly important element of keyboard skills in the seventeenth century, toccatas do not appear as exemplars in demonstrating its rules in the treatises, and therefore bass-driven practices are not a primary consideration in my analyses.

We should not underestimate how much improvised counterpoint might have influenced compositional practice at the keyboard in genres other than those that are not strictly contrapuntal. That unwritten composition at the keyboard was a performative experiential activity is evident in Maugars’ account of hearing Frescobaldi on a visit to Rome in 1639. His description recounts how the composer made ‘a thousand sorts of inventions appear on his harpsichord’ but that even though his music had been printed, he needed to be heard to fully appreciate his skill in improvising.Footnote 39

The toccata: some generic evidence

Literary historians identify the use of formulae as a characteristic trait of oral poetry. The Italian keyboard toccata has likewise long been characterized as being formulaic, and it is tempting to see structural analogies to oral literature as described by Ong, Lord and others.Footnote 40 Nevertheless, how formulae are used, combined and processed into a larger structure as a matter of compositional choice, that is, choices made during composition at the keyboard as an oral process, at least in initial stages, is far harder to evaluate without the benefit of a verbal syntax. There is nonetheless an expectation of certain elements within a piece called a toccata. Kallberg's concept of a ‘generic contract’ between composer and listener is as germane to this type of improvised compositional process as it is to later genres.Footnote 41 Indeed, the manipulation of expected gestures may have been a key indicator of ‘modernity’ in instrumental music and may have implications for our understanding of the term affetti as used in instrumental music, especially with regard to rhetorical modes of delivery.Footnote 42 Formulae do not imply lack of structure or development, but are a tool in the creative process. However they do rest on an assumption of a shared language between listener and performer – a language the performer uses as a tool for creativity and the listener, for understanding – to be able to perceive norms, and departures from those norms that signpost meaning or direction in the narrative.

The modal theory prevalent at the end of the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries is likely to have played a role in the generation of formulaic procedures in compositional processes. It is relatively easy to see how outlining boundaries of species; positioning of the final; cadential patterns; recurrence of pitch patterns; and so on could be a used as a frame of reference – the assumed shared language – for unwritten compositional practices of all types. The relationship between improvisation and rhetoric likewise invites parallels in terms of building a macrostructure but will be beyond the scope of this article. My focus here is on foreground motivic activity, but my analyses are based on a framework in which modal boundaries and species relationships are assumed to be a unifying principle.Footnote 43

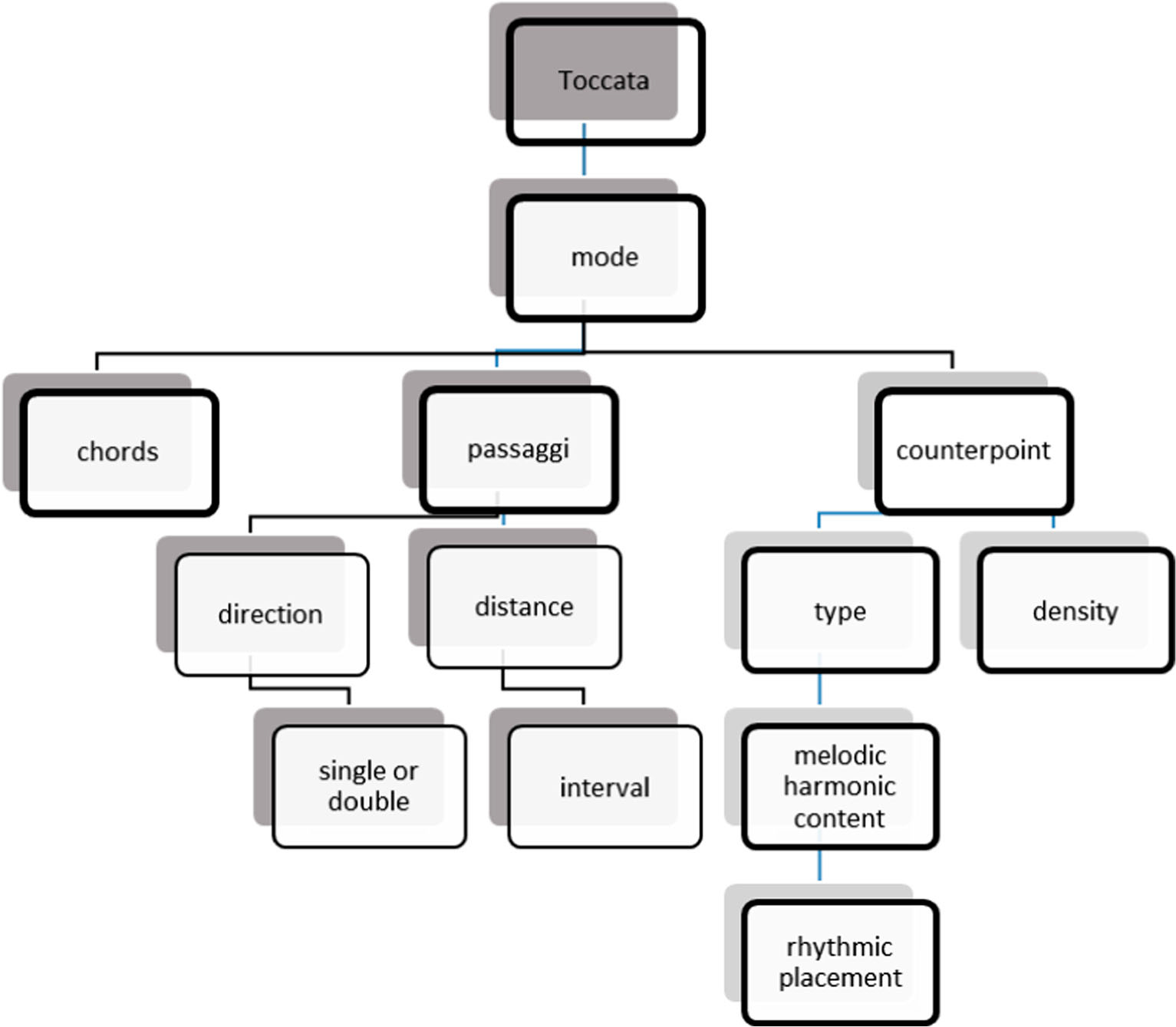

In seeking vestiges of oral composition, the most obvious starting point is the notion of ‘stock sections’ identified as typical of the early- to mid-seicento toccata.Footnote 44 From these ‘stock sections’, characteristic textural types may be drawn out, three of which predominate – chordal passages, running passaggi in one or both hands, and contrapuntal sections.Footnote 45 All three types rely on an underlying modal framework; tend to function at particular points in the piece; and can be categorised hierarchically, thus supporting a macrostructure. [Figure 1] Each textural type, in turn, is created from smaller motivic units, many of which echo the underlying modal boundaries or species relationships, and form a microstructure. The opening of the toccata almost invariably uses chordal textures to prolong the primary pitches of the mode. The position of the final is usually made clear in relation to the species boundaries of the fifth and fourth within the overall register. The ending of the toccata is often formed of running scale passages that both re-establish the mode after the diversions of the central portion of the piece, and serve to show the performer's skill. Each textural type may be reduced to sub-categories as indicated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Hierarchy of formulaic textures and their components.

Of the three main textural types, chordal passages are least divisible into sub-categories, but are the most likely places of greatest divergence between what is written and what is played. The examples in Diruta's Il transilvano suggest that the formulaic opening chordal passages are unembellished, as they are presented in long note-values.Footnote 46 In comparison, later pieces, particularly from Roman circles, indicate that such opening chords are frequently animated by trill type diminutions. One conclusion that may be drawn from this is that the simple exemplars in Diruta's book (largely by composers in the Venetian sphere of influence), were probably intended for the performer to embellish. It is worth noting that Diruta teaches how to play a toccata in the first part of his treatise, suggesting he regarded them as comparatively easy, while intabulating a vocal piece and creating four-part counterpoint is reserved for the second part. Although Frescobaldi suggests in his preface that the beginnings should be played slowly and arpeggiando, he frequently introduces an oscillating or trill type motif in the first few bars of a toccata that passes through different registers and from hand to hand. This notated embellishment is perhaps an attempt to capture the kind of diminutions that Diruta intended for his fictional student to insert into his exemplars.

Running passages of scales passing from one hand to another are, like diminutions, standard elements of keyboard style and are introduced by Diruta as an early stage of learning keyboard skills, just prior to learning diminutions.Footnote 47 In the context of the toccata, passaggi conform to the modal patterns introduced by the opening chords. In a liturgical context, the purpose of the toccata might have been to provide the pitch for a motet or vocal piece to follow, in which case, sections of chords and passaggi are functional, but little more.Footnote 48 As a formula for oral composition, all that is needed is the required mode or psalm tone from which the performer could create a simple toccata that would fulfil the required function. In a secular environment and played on the harpsichord, passaggi could become a vehicle for virtuosity.

Analysis of passaggi written out in printed texts provide a micro view of combinations of ascending and descending figurations that relate to the formulaic ‘composing out’ of intervals used by Ganassi and other instrumental tutors. Passaggi can be divided into sub-categories according to direction, distance travelled, left or right hand or both, and so on.Footnote 49 These formulas were stock in trade for ‘intabulating’ or embellishing vocal models, and it is unsurprising that many toccatas, especially in the Venetian style, seem similar. Murray Bradshaw's hypothesis that the toccata evolved from psalm tones was, no doubt, suggested by this rather skeletal pattern of chords and scales.Footnote 50 Bradshaw's view is not universally accepted, and Silbiger has argued that vocal polyphony rather than psalm tones acted as a model for the toccata, and has ‘detabulated’ examples in trying to expose such models.Footnote 51 If we take the view that the toccata is a repository for oral practices, there may be many different conceptual models that display similar surface formulae.

Of the three textural types, the presence, and increasing prevalence, of contrapuntal sections in the Roman toccata suggest a locus for a more fruitful search for vestiges of oral compositional techniques. While chords and scales require little overt compositional inventiveness, counterpoint demands a different skill. How motifs are used in contrapuntal contexts provides some more tangible evidence of oral procedures of composition at the keyboard that have become embedded in the printed music that has come down to us.

The analyses that follow draw on a sample of toccatas amounting to approximately 55 individual pieces by Merulo, Rossi, Ferrini, Salvatore, Froberger and Frescobaldi, as well as three toccatas from the Chigi manuscript I-Rvat Ms. Q.IV.25 (attributed to Frescobaldi but disputed), and three anonymous toccatas from the manuscript I-RAc Ms. Classense 545 (Ravenna 545).Footnote 52 The Frescobaldi sample was drawn from his Libro primo and Secondo libro, but not the Fiori musicali. This sample yielded the initial data concerning textural types and subsequent indicators of areas for deeper analysis.

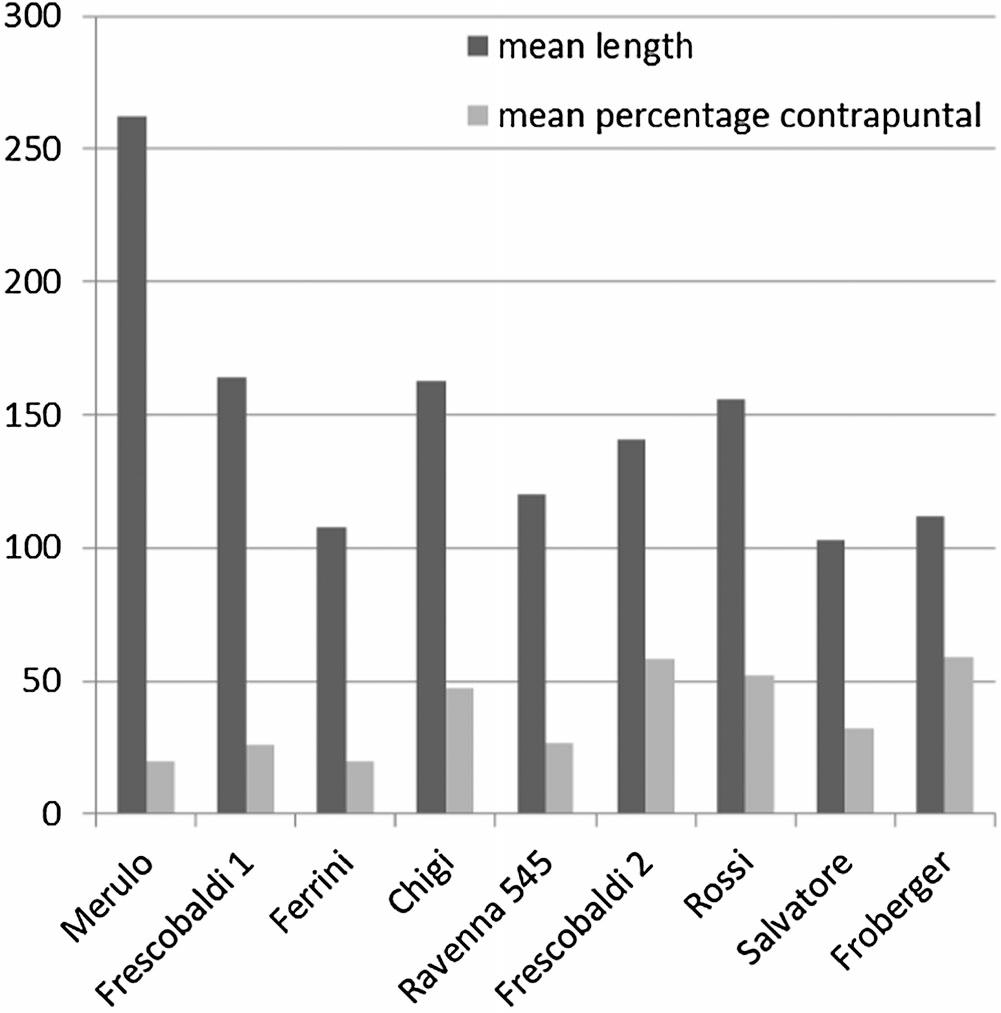

An initial overview of textures indicated a gradual shift in importance of counterpoint in relation to the toccata as a whole.Footnote 53 This shift can be measured quantitatively as a percentage of the total length, as indicated in Figure 2 which shows the raw data as a mean for each composer or, in the case of Frescobaldi, for each publication. In this and subsequent figures, the data is ordered according to the date or approximate date of publication or assumed composition. This graph shows that pieces produced towards the middle of the century contain a higher percentage of counterpoint in relation to a shorter total length. As can be seen in Figure 2, the pieces by Merulo are considerably longer but contain only a small percentage of contrapuntal textures compared to the rest of the sample. Almost all of Merulo's contrapuntal sections are derived from rhythmically offset scales, and many of them evolve into homorhythmic chordal passages.Footnote 54 As the character of Merulo's contrapuntal working is so different from that evident in the pieces with a provenance outside Venice, his toccatas were excluded from subsequent analysis of contrapuntal passages on stylistic grounds. The three anonymous toccatas from Ravenna 545 were also excluded, as they are not a unified group, varying significantly in length and distribution of textures. They were included in the survey as an additional point of comparison, but, for the purposes of the analyses that follow, they are statistically insignificant.

Figure 2. Contrapuntal sections in relation to whole length measured by tactus and expressed as percentages. Note that all the data represented in these graphs is raw data and has yet to be subject to statistical tests.

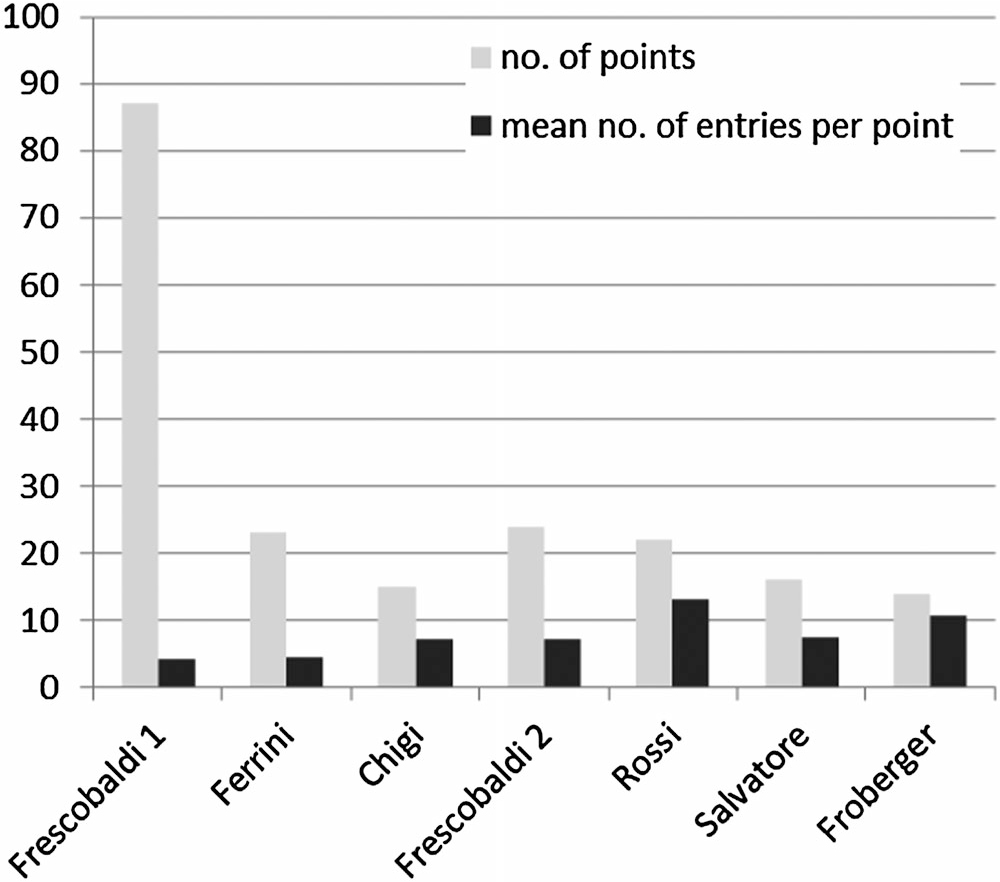

The status of contrapuntal passages can also be measured qualitatively in the relative density of points of imitation. Figure 3 shows the mean number of entries for each contrapuntal point. This includes all points in each toccata. It is apparent in Frescobaldi's early pieces that there are many points of imitation in relation to the whole. These are short and quite fragmentary, while in later toccatas, for example by Froberger, there are fewer and longer points, and in each point a greater concentration of entries. These initial findings suggest a shift in compositional procedures.

Figure 3. Relative density of points of imitation.

While chordal passages and running figurations might be obviously formulaic and based on a given mode or psalm tone, analysis of the points of imitation provides further data that may signpost an unwritten origin. First, an examination of the type of imitation provided a qualitative classification of these points based on the relative strictness of the imitation. Four categories emerged: real (exact transposition); tonal (with alterations to maintain the prevailing modal or tonal centre); variant; and pseudo imitation. Here I define variant imitation as an imitation in which a single interval or rhythm is alteredFootnote 55, while pseudo imitation is not truly an imitation but a contrapuntal texture in which following voices copy the rhythm patterns and general melodic direction of the leading voice, but change intervals apparently randomly.Footnote 56

The toccatas in Frescobaldi's Libro primo (1615/16) use a range of types of imitation, and include contrapuntal passages that start as variant or pseudo imitations, but are extended by using truncated versions of the motif already in use. In other words, they are not properly imitative at all. There is also a loose use of motifs that repeat in a different register or have significant gaps between apparent imitations. I have grouped these ‘pseudo’ imitations with variant imitations for the purposes of clarity in the graph in Figure 4, as the technique is rare in the work of the other composers under consideration. In his Secondo libro (1627) the imitations are more developed in terms of density though not at predictable temporal distances, and sometimes broken up with antiphonal rather than imitative extensions. This rather loose contrapuntal treatment gives way to more formalized, measured imitations that enter with some degree of temporal and intervallic predictability in Froberger's Libro secondo (1649), his earliest surviving collection, where the contrapuntal sections tend to use strict imitation. A summary of the analytical data is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Types of imitation measured by tactus and expressed as mean percentages.

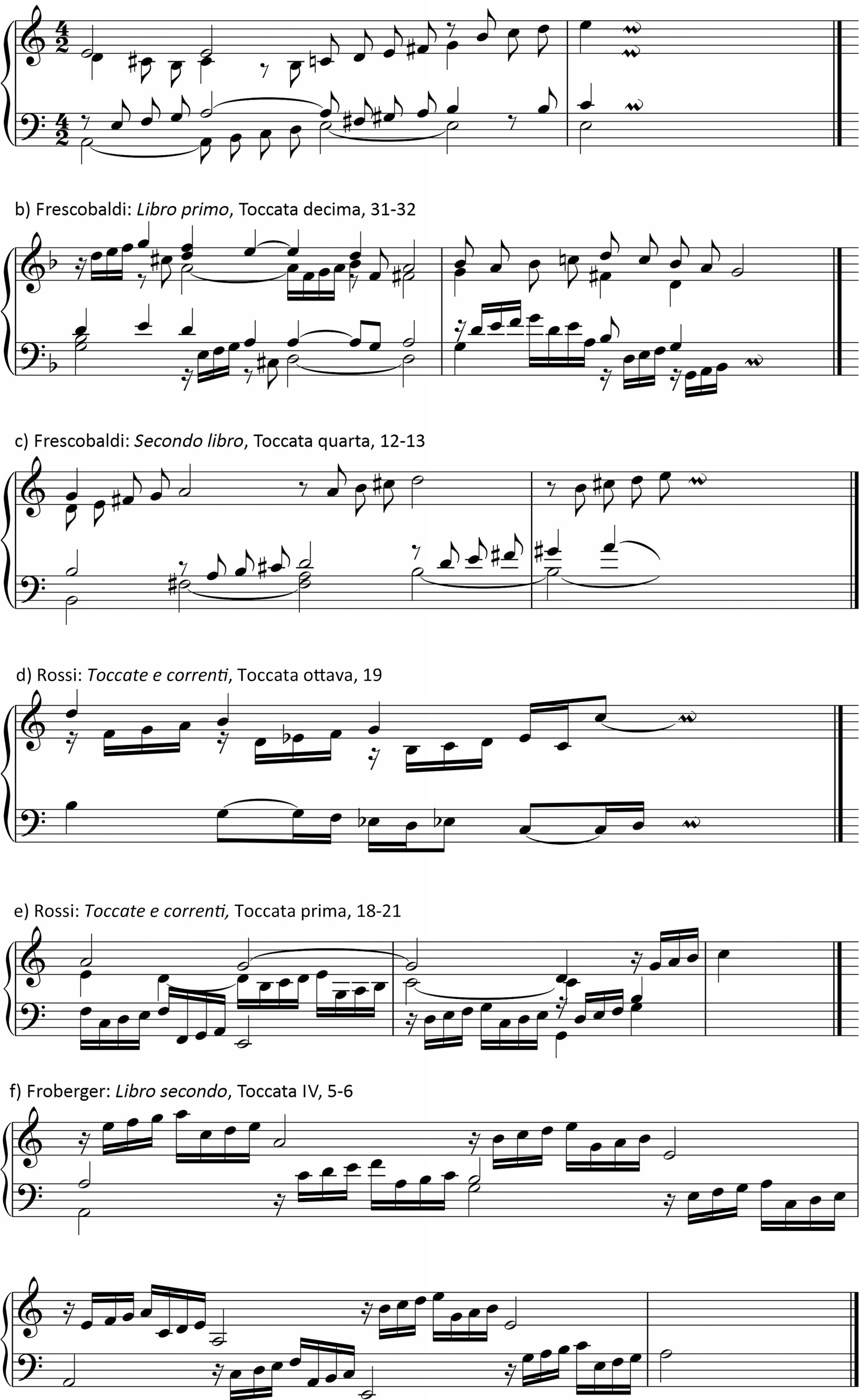

The shift towards stricter imitative counterpoint in the later pieces evident in Figure 4 may indicate several things. It could be symptomatic of the emergence of a stronger sense of harmonic tonality, or indicative of a more literate compositional approach in the younger Froberger. On the other hand, a residual oral approach in which modality was more prevalent directly influenced compositional choices in the work of Frescobaldi. Example 1 illustrates these differences.

Example 1a. Frescobaldi, Secondo libro, Toccata undecima 22–24. All Frescobaldi examples here and below are transcribed from Frescobaldi, Toccate e partite libro primo (Rome, 1637), and Frescobaldi, Secondo libro di toccata…(Rome, 1637); facsimile editions, ed. Laura Alvini, Archivium musicum: Collana di testi rari, 3–4 (Florence, 1980) with additional reference to Frescobaldi, Toccate e partite libro primo, ed. Christoper Stembridge (Kassel, 2010) and Secondo libro di toccate ed. Etienne Darbellay, Monumenti Musicali Italiani’, 3 (Milan, 1979).

Example 1b. Froberger, Libro secondo, Toccata IV, 16–19. All Froberger extracts in this example and those below are transcribed from Froberger Libro secondo, 1649 and Libro quarto (Ms Mus Hs 18706), Siegbert Rampe, ed., Neue Ausgabe samtlicher Clavier- und Orgelwerke, 1 and 2 (Kassel, 1993, 1995).

The passage from ‘Toccata undecima’ from Frescobaldi's Secondo libro demonstrates a fluid approach to imitation. The dux presents a simple rising scale over a third, followed by a descending skip of a perfect fifth, then ascending and descending skips of a third. In modern terms, it looks like a subject in A minor. The imitation that follows suggests it will be an imitation at the fifth below, but subsequent entries prove otherwise with real, tonal and variant entries eventually breaking down into a truncated pattern consisting only of the scalic third, which then breaks down into passaggi. This type of contrapuntal treatment accounts for the high levels of pseudo and variant imitation indicated in the graph. However, Froberger's dux presents a subject comprising a rising arpeggio, followed by a descending scale over a fifth, and then a pattern strikingly similar to Frescobaldi's. The whole is then imitated at the fifth and proceeds predictably at regular temporal distances.

An alternative interpretation of the data is that the differences in approach to counterpoint could simply be a ‘thumbprint’, or measure of the individual styles of these composers. If that is the case, then we have the basis of a way to assess authorship of anonymous pieces. I would argue though that, even if this is an individual measure of style, the presence of a looser contrapuntal style that rests on an older modal framework represents significant traces of unwritten procedures in the older composer. The evidence of the data shown in this graph indicating the loose treatment of imitative passages in Frescobaldi's work, especially contrapuntal writing that is only apparently, rather than strictly, imitative, may correlate with Annibaldi's identification of low identical entry ratios in the contrapuntal manipulations present in Frescobaldi's early Fantasie. This type of contrapuntal working in the toccatas, like that of the Fantasie, may also be indicative of the demands of a particular kind of patronage. It is beyond the scope of this article to pursue this line of enquiry.Footnote 57

Given the apparent emphasis on contrapuntal sections, further analysis of the microstructures of the head motifs for these sections points to other formulaic processes. The first order interval of a motif, that is, the distance between the first two notes, indicates whether the melodic figure is scalic or moves by skip. A sample of these motifs was extracted from the sources outlined above, and the first order intervals were identified and counted.Footnote 58 The results are reflected in Figure 5.

Figure 5. First order intervals of motifs represented as mean percentages of the total number of intervals counted for each composer.

This analysis makes no qualitative assessment of the imitation that follows each interval, which may be a pseudo imitation or variant imitation, nor does it evaluate the relationship between motifs across a single piece. A classification of motivic movement in this way may point to underlying performative habits that are embedded in the notated pieces. Further research and refinement of these statistics may, for example, enable ascending or descending movement to be mapped on to placement of a motif in left or right hand and thus correlated to potential fingering habits. In this sample, for all of the composers considered, the majority of motifs proceed by step and, in the case of Frescobaldi, the figure is highest at upwards of 70%. By quantifying the number of intervals of a third or greater, and including those same intervals in a count of intervals of a fourth or greater, it is possible to see the number of motifs that start with a skip of a third, either major or minor. Only a small number of motifs start with an initial skip of a fourth or larger, with Froberger scoring the highest incidence of these intervals. It is highly likely, given these statistics, that there may be underlying formulae that reflect the patterns of a modal macrostructure within the motivic microstructure.

Motivic patterns and formulaic figurations

The macrostructure created by successive sections of contrasting textures does not seem to have a predictable pattern, other than a chordal opening and increasing density of passaggi towards the close. However, within that loose framework, there are a sufficient number of predictable elements at the microstructural level appearing in different contexts and different pieces in the form of recurring melodic-harmonic patterns to justify their identification as formulae.

All of the toccatas in Frescobaldi's Libro primo and Secondo libro, including the elevation toccatas but not the durezze e ligature, contain two types of motif: trill-type motifs consisting of an oscillating figure with either a prefix or suffix or both; and melodic motifs which may be derived from an interval or interval progression, filled out and rhythmically activated. The trill-type diminution figure raises interpretational difficulties, not to mention problems of nomenclature. It is neither a true tremolo, tremoletto nor groppo as described by Diruta; nor a trillo, the term that Frescobaldi uses as a global descriptor in his prefaces, as this term has implications of the repercussive figure used in vocal ornamentation. They do seem to have similar functions to the groppi illustrated in Il Transilvano where, Diruta suggests, they may be rhythmically based on any note length, used ascending and descending and at cadences.Footnote 59 His examples of groppi used to embellish triads could easily represent the type of pattern used to navigate between chords in the opening of a toccata. As used by Frescobaldi, diminution motifs fall into five broad categories based on the distance (either tone or semitone), initial direction (ascending or descending) of the oscillation, and the prefix or suffix attached to them. These categories can be mapped against the most common contexts of diminutions, whether cadential, passage work or head motifs in contrapuntal sections. A sample of these types is shown in Example 2.Footnote 60 The type shown in Example 2 a) and b) are most commonly cadential, while those in Example 2 c) and d) may take on a more ‘thematic’ function and be used in imitative or pseudo-imitative passages. Some of these patterns are equally evident in the opening sections of toccatas from Froberger's Libro secondo and Libro quarto, though they appear less in later sections of these pieces. In Rossi's toccatas they are used more sparingly, but, nonetheless, do make an appearance from time to time. The simple fact that these motifs can so easily be grouped suggests a repertory of formulaic patterns, probably learned at the keyboard at an early stage of musical education, and recalled from memory in the process of composition at the keyboard. Their written survival is a residue of that oral practice.

Example 2. Frescobaldi – Trill-type diminution motifs.

The melodic motifs derived from an interval or interval progression are related to the common patterns used for filling out simple intervals in the process of embellishment or intabulation that are described in sixteenth-century performance manuals.

A closer examination of the motifs used by Frescobaldi, Rossi and Froberger in their toccatas bears out the evidence of the theorists mentioned above, and suggests that they drew on a variety of note patterns that are common enough to be classified as memorized formulae. Melodic patterns that outline fourths and fifths, especially if these are stepwise, project the species boundaries of the prevailing mode. They can be manipulated to generate or to evade cadential closure and may be easily chromaticised to create passing tonicisations. Patterns of fourths and fifths, importantly, also lie ‘under the hand’ on the keyboard.

One of the most common gestures in the toccatas under scrutiny is a stepwise ascending fourth, usually commencing from a rest or tie, giving it an offbeat rhythmic shape. It is found in both contrapuntal contexts and in passaggi. In Frescobaldi's work this pattern may appear distributed across two voices, one of which has a sustained note, usually the lower extreme of the interval, while the other completes the ascent. Example 3a-c provides three different versions of this motif. The offbeat metrical position suggests movement toward the upper extreme of the interval and, depending on the position of tones and semitones, may infer a moment of perfect closure. If this is shifted to a strong-weak accentuation, it indicates movement away from the initial lower note, rather than progression toward the upper note. The fourth is a modal signifier, so this formula is embedded in the harmonic language of its context. Patterns ascending over a fourth from an offbeat are also found in Froberger and Rossi, but the distribution of such a motif over two voices seems peculiar to Frescobaldi.

Example 3. a–f. Offbeat ascending fourth patterns. All Rossi extracts in this example and those below are transcribed from Toccate e correnti d'intavolatura d'organo e cimbalo (Rome, 1657); Facsimile, ed. Laura Alvini, Archivium musicum, Collana di testi rari, 12 (Florence, 1982).

Rossi, in the ‘Ottava toccata’ (19) (Example 3d) for example, uses the offbeat ascending fourth to reach a longer note, inverting Frescobaldi's trick of sustaining the lower note, but creating an equally compelling frame for species boundaries. Then over a period of several bars (22–26), he opens the first interval of the ascent from a tone to a third, shifting the outlined interval from a fourth to a fifth. In the ‘Prima toccata’ (18–21) (Example 3e) he uses a succession of offbeat ascending scale segments separated by skips. The first scale segment is a fourth, but the subsequent segment of each group is more fluid, as demanded by the pseudo-imitative character of the passage. Froberger, likewise combines two ascents to create an imitative passage in the fourth toccata of the Secondo libro (5–7) (Example 3f) although in this case the second ascent is truncated.

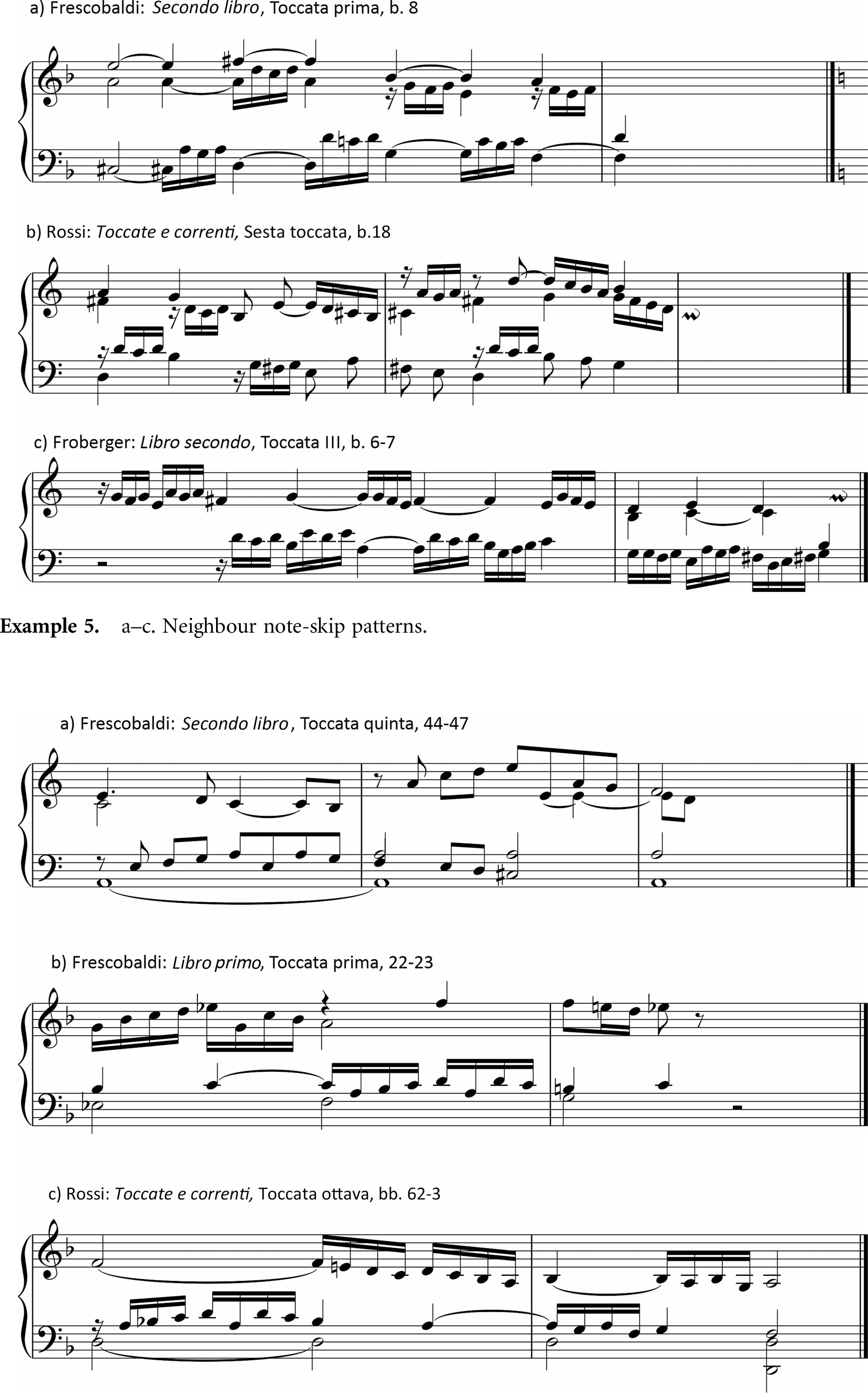

A second figuration or formula is created from two pairs of ascending steps, comprising either tones or semitones, separated by a skip (Example 4a-d). This pattern is harmonically mobile, nearly always contains some chromatic alteration, and may be manipulated to create or to avoid cadential expectations. This pattern too, is frequently positioned on an offbeat, creating forward movement, and may be split across ‘voice’ parts in sequential passages. Froberger uses it as a cadential approach in the final bars of the first two toccatas of his Libro secondo. Rossi uses a similar pattern in the ‘Decima toccata’ but, instead of creating cadential impetus, it is used in an imitative passage in which the rhythmic placing shifts the accent between stronger and weaker metrical positions. This figuration is related to patterns comprising an offbeat neighbour-note figure, followed by a skip. These appear both in the context of passaggi and as motifs used in imitation (Example 5a-c).

Example 4. a–d. Patterns of pairs of ascending steps.

Example 5. a–c. Neighbour note-skip patterns.

A further pattern used by Frescobaldi in both passaggi and in contrapuntally active contexts is composed of a stepwise ascending fourth and descending third, separated by a single note a skip away from both scale portions (Example 6a-c). The two scalic elements remain constant, but the distance of the skip is variable, making this a remarkably malleable figure. Its most frequent placing is between two chords, commencing from an offbeat. The central skip determines the pitch on which the figure ends, so the pattern may be used to prolong a single harmony or to change harmony. Rossi also uses this pattern in his ‘Ottava toccata’. Variants in which either the ascent or descent are shortened are also found, as in Example 7 from Frescobaldi's Libro primo which likewise uses a stronger rhythmic profile.

Example 6. a–c. Ascending and descending scale segments separated by a skip.

Example 7. Truncated scale segments separated by a skip.

These patterns all have identifiable intervallic derivations, predominantly thirds, fourths and fifths, which suggests that they may function in relation to modal boundaries, and place them in a theoretical framework based on projection of modal finals. In addition, their relationship to specific intervals allows for them to behave like diminutions as substitutes for those intervals. Not only does one find identical figures in different contexts and in different modes, but also derivatives of these figures created from the alteration of a single interval or change in melodic direction. While there are differences in the way these patterns are used by Frescobaldi, Rossi and Froberger, the fact that they appear in so many different contexts suggests that individually they do not carry a specific function, such as pre-cadential extension or building passaggi, but are flexible enough for a range of purposes including points of imitation, sequence, chromatic alteration to shift harmonic direction, or fulfilment of cadential expectation. However, they are not generally used as exordial motifs at the start of a composition, and seldom as head motifs initiating contrapuntal sections. However, the presence of such patterns does not mean that there is a lack of cohesion in the compositions or, conversely, that they are predictable. Indeed, some of Frescobaldi's toccatas indicate an almost organic treatment of motif.Footnote 61

Beyond single author collections: intertextuality and ascription

The repetition of figurations in single author collections, both print and manuscript, by different composers, raises the question as to whether such formulae have composer-specific variants, or whether they are more generally representative of an oral tradition that happens to have been preserved in a single-composer print or, in the case of Froberger, manuscript. In order to address this question, a manuscript collection that scholars agree is representative of the Roman keyboard tradition of the period 1630–50, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana – Vat Mus Chigi Q.IV.25 (henceforth Chigi 25), will present an illuminating case.

This manuscript bears an ascription to Frescobaldi on the flyleaf, but its authorship has been disputed for decades and the literature about it is sizeable.Footnote 62 The main scribal hand is that of Nicoló Borbone, one of Frescobaldi's pupils, who was also an organist and composer in his own right as well as the engraver of Frescobaldi's two toccata publications. Although the last three toccatas of the manuscript are the focus of most of the debates concerning the possible composer of the manuscript, they provide ideal case studies here. I have argued elsewhere that they may be examples of student work demonstrating the absorption of the Roman toccata idiom.Footnote 63 However, regardless of composer or purpose, these pieces represent compositional treatment of texture that is consistent with toccatas of a similar provenance and time period as can be seen in Figures 2–4 above.

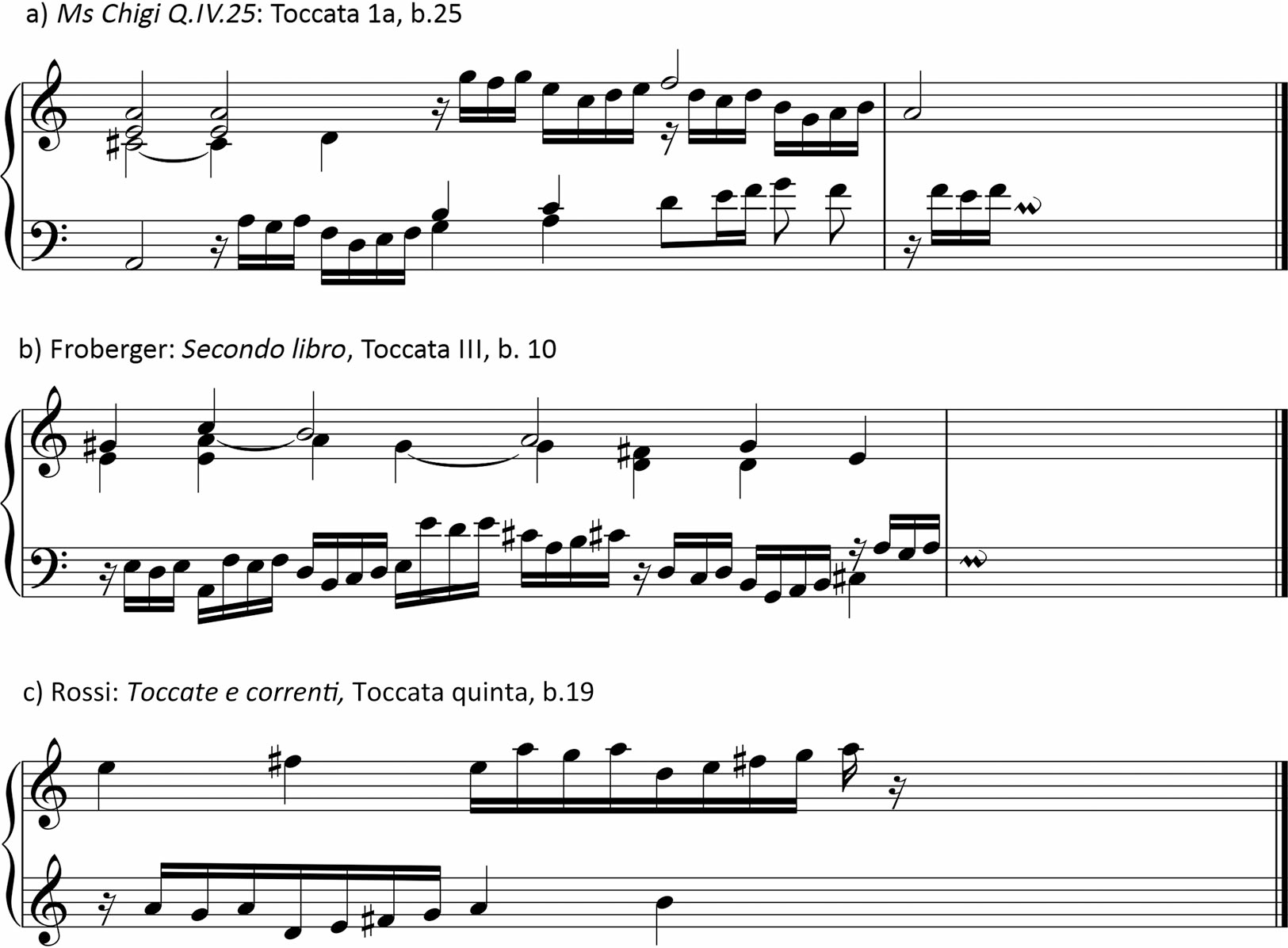

The typically Frescobaldian trill-type motifs appear, although there are fewer of them and they are not predictably near the start of each piece. Moreover, the types of motif used in contrapuntal sections are also consistent with generic expectations. Patterns based on an offbeat ascending fourth are present, though as with the trill-type motifs, there are fewer of them. However, the similarity of one occurrence of this gesture in the first of these toccatas to passages in Rossi and Froberger's work is evident (Example 8) The offbeat neighbour-note pattern also appears in the Chigi toccatas in passages that resemble Rossi and Froberger shown in Example 9.

Example 8. A comparison of passages using an offbeat ascending fourth pattern. Extracts from the Chigi toccatas are transcribed from the facsimile edition, Vatican, Biblioteca apostolica vaticana, MS Chigi Q.IV.25, ed. Alexander Silbiger (New York and London, 1988).

Example 9. A comparison of offbeat neighbour-note patterns.

In addition to the Frescobaldian motivic formulae in this manuscript, there are also some longer figurations that are used by Rossi and Frescobaldi, such as a scalic gesture in contrary motion that Kirkendale described as a circulatio figure, and the use of a persistent ostinato in one hand against a changing pattern in the other.Footnote 64 Both of these gestures are created by physical movement of the hands. In the case of the former, both hands move in opposite directions, in the latter, one hand remains stationary and the other moves away from it. The presence of such formulaic patterns and motifs suggests that a repertory of common gestures used by the performer-composers of the time has been absorbed by the composer of this manuscript, and in all probability was learnt working at the keyboard.

Where ‘stock’ patterns are used in different rhythmic and harmonic contexts, and in pieces with very different ‘thematic’ content, they cannot be considered concordant in the sense of establishing some kind of compositional priority between sources. Instead, these ‘concordances’ mark both sources as displaying evidence of oral composition. Intertextuality is likely to arise from the use or re-use of memorized and previously worked formulae while performing and composing at the keyboard. In itself, the presence of such patterns is perhaps not significant, but it brings into question the presence of partial concordances between sources as an argument for authorial identity, and demands a deeper understanding of composer-specific uses of common gestures and formulae. Concordances comprising patterns that are primarily derived from memorized diminution patterns that are also not genre-specific, are particularly problematic if used as indicators of common authorship.

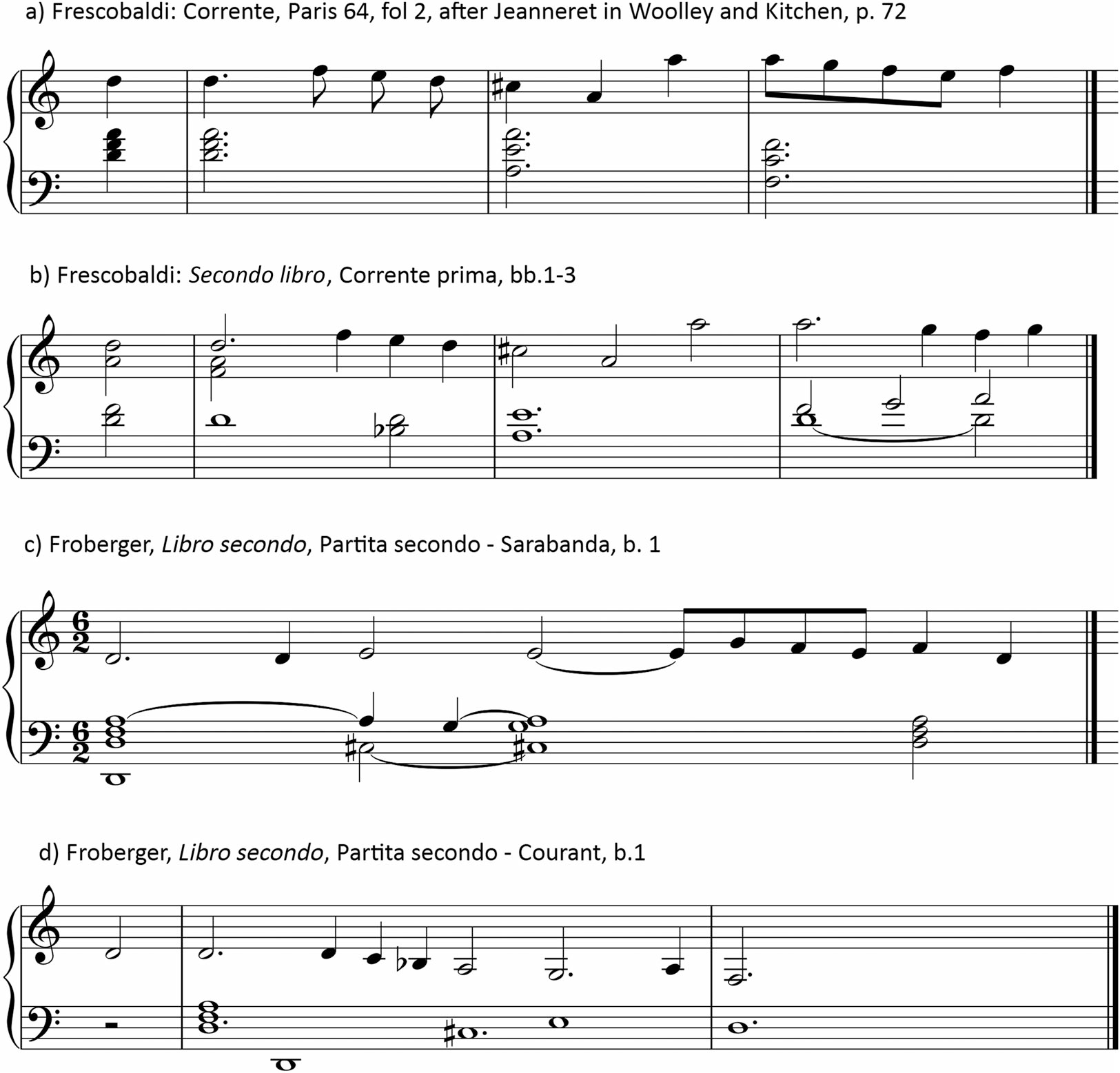

Jeanneret has argued that the correnti in the manuscript F-Pn, Rés.Vmc 64 (henceforth Paris 64) are evidence of a process of composition in which small motivic patterns form the basis of a composition that is worked out first in miniature, elaborated to form a more worked out second stage, and progressing to a final, finished composition – a process she terms ‘modular’.Footnote 65 The generic nature of the motivic pattern in question (Paris 64, fol. 2, bar 5 and bar 11) which is identical to formulae for one of the most basic embellishments of the interval of an ascending third in the ‘regola prima’ of Ganassi's Fontegara, and which also appears in Sancta Maria's treatise repeated to extend it to fill a longer note value, I would argue, is evidence of a performative compositional process.Footnote 66 This same ‘module’ is also found in the third of Rossi's published correnti. A very similar pattern that is essentially an inversion of it is used in Rossi's Corrente seconda.

Another pattern identified by Jeanneret as a concordance between Paris 64 fol. 2, and the corrente prima from Frescobaldi's Secondo libro (Example 10) also appears in the sarabanda from Froberger's ‘Partita seconda’. With one interval changed (the upward skip of a third, becomes a repetition of the same pitch), it appears also in the courant from the same suite. As with the module identified above, this pattern too derives from embellishment practices and can be found in Ganassi's regola prima as an embellishment of a descending second. There are enough of Froberger's other dances that contain gestures of a similar ‘shape’ (to use the Rétian terminology) that these patterns cannot be said to have an authorial identity, for example, the courantes of the Libro secondo, Partita seconda, and Partita quarta and Libro quarto Partita prima and Partita seconda. The patterns lie under the hand and are manipulated using memorized combinations and permutations, rather than demonstrating an evolving written process.

Example 10. Intertextuality of Frescobaldi's compositional module.

These generic embellishment patterns are perhaps more exposed in the simpler dances than they are in more complex pieces such as the toccatas. However, successive combinations of the same type of diminutions may add up to florid passaggi found in the keyboard toccatas. They should not therefore be used as a concordance to identify anonymous work, unless there is a substantial passage and an identical accompanying framework of other elements, including rhythmic character and harmonic or contrapuntal context.

Conclusions

The toccata, as a genre, fulfilled certain expectations in terms of sections of specific types of texture, starting with a chordal opening followed by a variety of contrapuntal sections and passage work of increasing density. That the composers were aware of the contrasts and different characters of such sections is evident in the prefaces that suggest ways of playing that separate and highlight affetti. The unwritten practices of performance, or ‘delivery’ to use the rhetorical term, thus map onto the generic formulation of the macrostructure. The contrast and balancing of one affetto, or texture, against another suggests a reading of the prefaces that indicates a performance practice informed by structural as well as affective considerations. It may also afford a new way of evaluating the musical syntax of the keyboard toccata in relation to other instrumental genres such as the emerging sonata.Footnote 67

Within the microstructure, the presence of multiple formulaic patterns in toccatas at one level reinforces Diruta's claim that toccatas are ‘all diminutions’ and, in the work of Merulo, this is proved to be the case by the tiny amount of contrapuntal activity in relation to the overall length of his toccatas. Embellishment and rearrangement of simple ideas in multiform ways as seen in the examples here, seem to parallel the Erasmian notion of copia. If common educational practice is a reliable model, we can assume a level of learning by rote and example, copying the work of the ‘great masters’, and using ‘master’ works as exemplars for deriving new pieces. Indeed, Ganassi's presentation of embellishments in his treatise suggests that the pupil should start from the simpler patterns, playing and memorizing them, and then move on to patterns that are rhythmically more complex. Diruta, in addition, teaches his fictional pupil about modes so, perhaps for the keyboard player, learning flourishes that map onto modal boundaries or common cadence formulae in both hands would also have featured in that process.

For composers beyond Venice, the picture is more complex, with passages that are provably ‘all diminutions’ broken up by contrapuntal sections, the motifs of which are in many cases themselves formulaic. The formulae used in more complex antiphonal or contrapuntal contexts identified above in the toccatas of Frescobaldi, Rossi and Froberger, are evidence of a compendium of gestures that the composer-performer may have drawn on while working at the keyboard. The frequency of note patterns that fill a fifth or fourth suggests not only allegiance to modal boundaries, but also that, for the performer at the keyboard, they ‘fall under the hand’. Analysis in order to map interval patterns and their placement in either left or right hand, along with evidence of fingering patterns, may provide further evidence of the performative origins of these formulae.

The formulaic patterns outlined in the analyses above all seem to signal memorizing, copying, embellishing and expanding as part of an oral compositional process that has been preserved in the written text. Learning processes based on repetition, memory and the embedding of physical movement in a kinetic memory results in elements of intertextuality almost by default, as finger patterns and hand movements are repeated in different contexts. It is this inadvertent intertextuality preserved in written compositions that betrays the oral and performative compositional process. The fact that these vestiges of the compositional processes can be extracted does not undermine suggestions that the books may have been pedagogical models, monuments of collected works or attempts to preserve a single outstanding performance, but they can add to our understanding of the unwritten conceptualization and genesis of the toccata as a genre.

How musicians learned compositional skills, and especially the question as to how sections of counterpoint created using unwritten techniques and passages more loosely based on motivic patterns or formulae are fitted together on a conceptual level, needs further research. My analysis has demonstrated that contrapuntal passages become increasingly important in the toccata over time. As the average length of the toccata decreased, the frequency, density and length of contrapuntal sections increased, marking the transition from the toccata that is ‘all diminutions’ to one that is texturally more varied. As part of this process, specific parts of the toccata were populated by specific textures: the opening with chords or chords with diminutions; the end with a complex contrapuntal section followed by passaggi or passi doppi to create a final flourish. Newcomb's description of Frescobaldi's toccatas as following a ‘flexible procedural paradigm’ is apt, as the flexibility of any underlying organizational principles of the central sections is precisely the problem.Footnote 68 However, formulaic gestures comprising both diminution patterns and combinatorial permutations may have been memorized in the way that artists used model books or orators used key phrases or quotations from classical sources, positioning them and combining them to suit a new context.Footnote 69 The presence of common types of section seems to suggest parallels with rhetoric which, like composition at the keyboard, was an unwritten skill derived from practices of verbal delivery. Testing the validity of a hypothetical rhetorical structure as a generic procedure in the keyboard toccata (as opposed to examining the use of surface figures as codified by later German theorists) would demand analysis of a significant sample and is an area for future research.

The presence of the many motivic formulae do not rule out the hypotheses of Bradshaw and Silbiger that toccatas are based on pre-existent models, whether those are cantus firmi or secular polyphonic madrigals. However, such models may be deeply hidden by the successive processes of learning by imitation, emulation and expansion over more than one generation of teacher–pupil transmission.

The need to preserve and transmit larger-scale compositions, even if the written medium was inadequate and however they were designed conceptually, ultimately has given us a window through which to view, albeit obliquely, a distant performative practice. Notwithstanding some considerable lacunae in our knowledge, the identification of different techniques and patterns within the toccata as a genre is a step toward understanding the performative skill of composing at the keyboard.

ORCID

Naomi J. Barker http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4377-3180