For many reading this paper, it will no doubt come as a surprise to learn that the study of music subscription lists remains one of the most significant untouched areas in musicological research. This is in spite of the fact that most academics who write about eighteenth-century British music will regularly refer to these lists in their writings, and there are several papers and book chapters that specifically focus on this area.Footnote 1 Most authors will, however, only deal with a small handful of these lists and, as such, a wider study is long overdue. Due to the potential that subscription lists have to offer, I made a decision in 2010 to undertake a project that involves the location and indexing of every subscription list attached to a music-related publication issued in Britain before 1820. Then, in 2013, I came into contact with Martin Perkins of the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire. He had envisaged a similar project and it made sense to combine our efforts. With the assistance of the catalogue of subscription lists compiled by Peter Wallis, and the British Library's music subscription list card index, we have been able to produce a list of around 750 works issued by subscription, although hitherto unknown examples continue to emerge on a regular basis.Footnote 2 It is our intention that these lists will ultimately be searchable through an online database. At the time of writing we have been able to acquire 557 lists, all of which have been included in the research for this article, the second in a series relating to our project. A great deal of work remains to be done but it is clear that these lists are an incredibly valuable resource for both musicologists and those interested in British social history.Footnote 3

In deciding which lists to include in the subscription list project, it was agreed that we needed to be as broad as possible and encompass everything associated with music. As a result, this study not only incorporates musical works, but also volumes that may contain no music notation whatsoever. This includes books of songs, poetry, psalms, libretti to ballad operas, and autobiographies, as well as essays on music, dancing and music theory. There are also books that have at first glance no relationship to music, such as The History and Antiquities of Doncaster (1804), written by that town's organist, Edward Miller (1735–1807).Footnote 4 Another is Harriet English's Conversations and Amusing Tales (1799), which, even though it has little to do with music, included a printed score to the song ‘Address to the British Fair’, set to music by Samuel Webbe (1740–1816).Footnote 5 There has also been a decision to focus on works issued in Britain rather than on the continent. This was primarily done for practical reasons, although it was agreed that a few works that contained music composed by British musicians, but published on mainland Europe, should be included. Likewise, the project also incorporates several books published in other English-speaking communities outside Britain, including the United States, which until 1776 had been under British rule, some from Ireland, and one example from British India; these areas have not been covered extensively.

One important area for discussion that revealed itself as the subscription-list project proceeded was the issue of gender, and how the proportion of subscribers changed between works issued at different times, in different places and across different musical genres. In terms of this article, there was little decision making as to which lists to include. The primary reason for any particular list's inclusion was accessibility. The first port of call was my own collection, housed at Durham University's Palace Green Library, as well as those held at other libraries in relatively close proximity. They included Durham Cathedral's Dean and Chapter Library and the university libraries of Edinburgh, Nottingham, Leeds and Glasgow. I also availed myself of numerous trips to London to consult items held by the British Library and in the Gerald Coke Handel Collection at the Foundling Museum. The internet has also made accessing a significant number of lists relatively easy. Other copies or transcripts of lists were kindly provided by fellow academics or by dealers in antiquarian music.

Analysing the lists

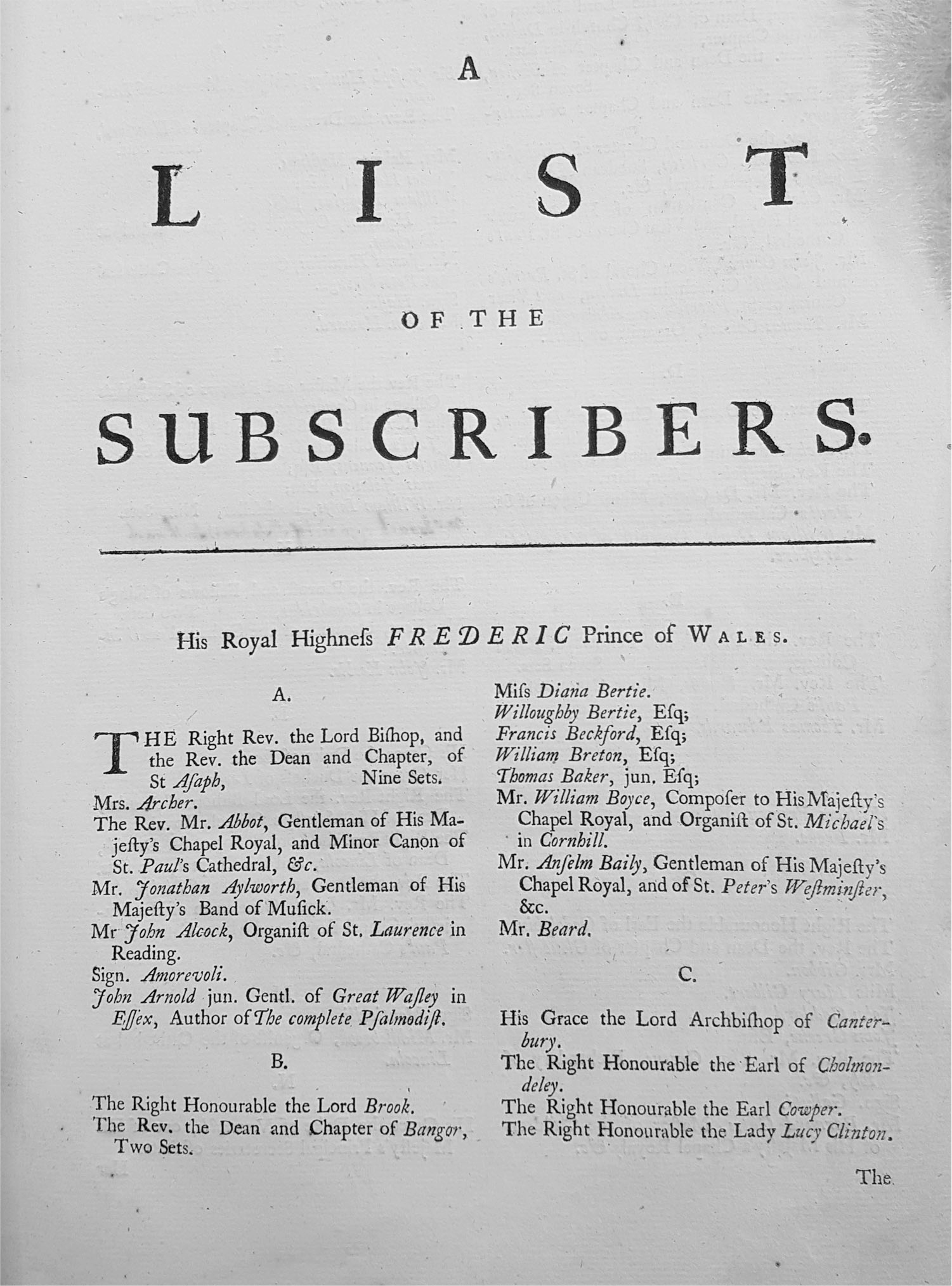

Although one might have expected it to be a relatively easy task to count the subscribers in any given list by their gender, this endeavour has been, to a degree, something of a minefield. (This data is presented in Appendix B). The biggest issue has been inconsistency between individual lists. Even the way lists are organized can differ considerably. Most lists tend to be grouped into sections by the first initial of a surname, although there are examples, such as James Fishar's Twelve New Country Dances (c.1780), where the names appear to be in the order in which subscriptions were received.Footnote 6 Important subscribers, particularly royalty, are not included in the main body of a list but appear at its head. Within each section, the subscribers are not normally listed alphabetically; aristocrats appear first, followed by the other subscribers and not normally in alphabetical order. Even the importance of individual members of a family is reflected in the lists, with the head of the household appearing first, followed by his wife and then children. In some lists it is evident that a few names were received late. These were sometimes added to the list by hand (Figure 1) or incorporated into a second issue.Footnote 7 In some cases, gaps were deliberately left in a list so that extra names might be added to the plates for a second volume. In such instances, the name of an aristocrat could potentially appear below the name of a person of more humble stature. This is particularly evident in Samuel Arnold's (1740–1802) edition of Handel's works, issued from 1789, in which there were so many changes to the plates over the course of publication that the engraving of an entirely new list became a necessity. Another method was to group subscribers by the place they lived, as can be seen in that attached to Charles Dibdin's (1745–1814) Musical Tour (1788); this is presumably due to the way subscriptions were received with agents in each town forwarding their lists of subscribers to the author.Footnote 8 Furthermore, in cases where a significant number of subscribers were received after the subscription list was produced, a list of extra subscribers was sometimes added at the end; an example can be found in Richard Neale's A Pocket Companion for Gentlemen and Ladies (1724).Footnote 9

Figure 1. Second page of the subscription list to the ‘Dedication Copy’ of John Pixell's (1725–84) Odes, Cantatas, Songs &c … . Opera Seconda (1775), which contains a number of manuscript additions in the composer's hand.

Note: GB-DRu: Fleming 367(c). All images are taken from the prints in the author's collection, held by Durham University's Palace Green Library. The Dedication Copy is discussed in Simon Fleming, ‘John Pixell: An 18th-century Vicar and Composer’, The Musical Times, 154 (2013), 71–83.

The gender of a subscriber in these lists is principally determined by their title, as in most cases a Christian name is not provided. Female subscribers tend to be given the title of ‘Mrs’ or ‘Miss’, with ‘Miss’ without a Christian name referring to the eldest or only unmarried daughter.Footnote 10 Occasionally ‘Signora’ or ‘Madame’ is also used. For members of the aristocracy, the possible titles include ‘Lady’, ‘Duchess’ or ‘Dutchess’, ‘Countess’, ‘Viscountess’, ‘Baroness’, ‘Marchioness’ or even ‘Princess’. For men, there are the equivalents of the aristocratic titles; other male titles include ‘Mr’, ‘Master’, ‘Reverend’, ‘Captain’, ‘Colonel’ or ‘Doctor’, with gentlemen having the additional title of ‘Esquire’ or ‘Gent’. In some lists, a long dash symbol, ‘–’, is given. There appears to be several reasons as to why this symbol is used. It could be that the subscriber wanted their name omitted from the list, either in full or part, and this was put in its place. Alternatively, it could be that the name of the subscriber, which would have been taken down in handwritten form, was illegible.Footnote 11 However, this could also be used as a shorthand to avoid the need to duplicate a common title between consecutive subscribers. In most cases though, it would seem that any anonymous or wholly illegible subscribers were simply omitted.Footnote 12 Occasionally the absence of a title has made it impossible to determine the gender of a particular subscriber, such as when the subscriber is simply recorded by their initials or is simply described as ‘unknown’ or ‘anonymous’, presumably as the name was indecipherable. In these rare instances, the subscribers have been added to the ‘other’ category in Appendix B.

There are instances where two people, such as partners or siblings, jointly subscribed to a single copy of a work. On these occasions, only the first subscriber has been counted. In instances where two subscribers jointly subscribed to two or more copies but as a single entry in the list, both subscribers have been counted individually.Footnote 13 If the subscription list has manuscript additions, these names have been included in the count without comment (Figure 1). Music publishers, booksellers and instrument makers, as they tend to appear in these lists as individuals, have been included in the numbers of individual subscribers but only counted once even if they were in a partnership.Footnote 14

The third or ‘other’ category is essentially formed of non-individual or institutional subscribers. This includes musical societies, cathedral deans and chapters (Figure 2), churches, choirs, concert groups, schools and colleges at both Oxford and Cambridge. Occasionally the entry would additionally include the name of the person who sent in the subscription and, in such instances, the name has been ignored.

Figure 2. First page of the subscription list to Maurice Greene's (1696–1755) Forty Select Anthems in Score, vol. 1 (1743), which includes 24 cathedral deans and chapters amongst the subscribers.

Note: GB-DRu: Fleming 487.

Publication by subscription

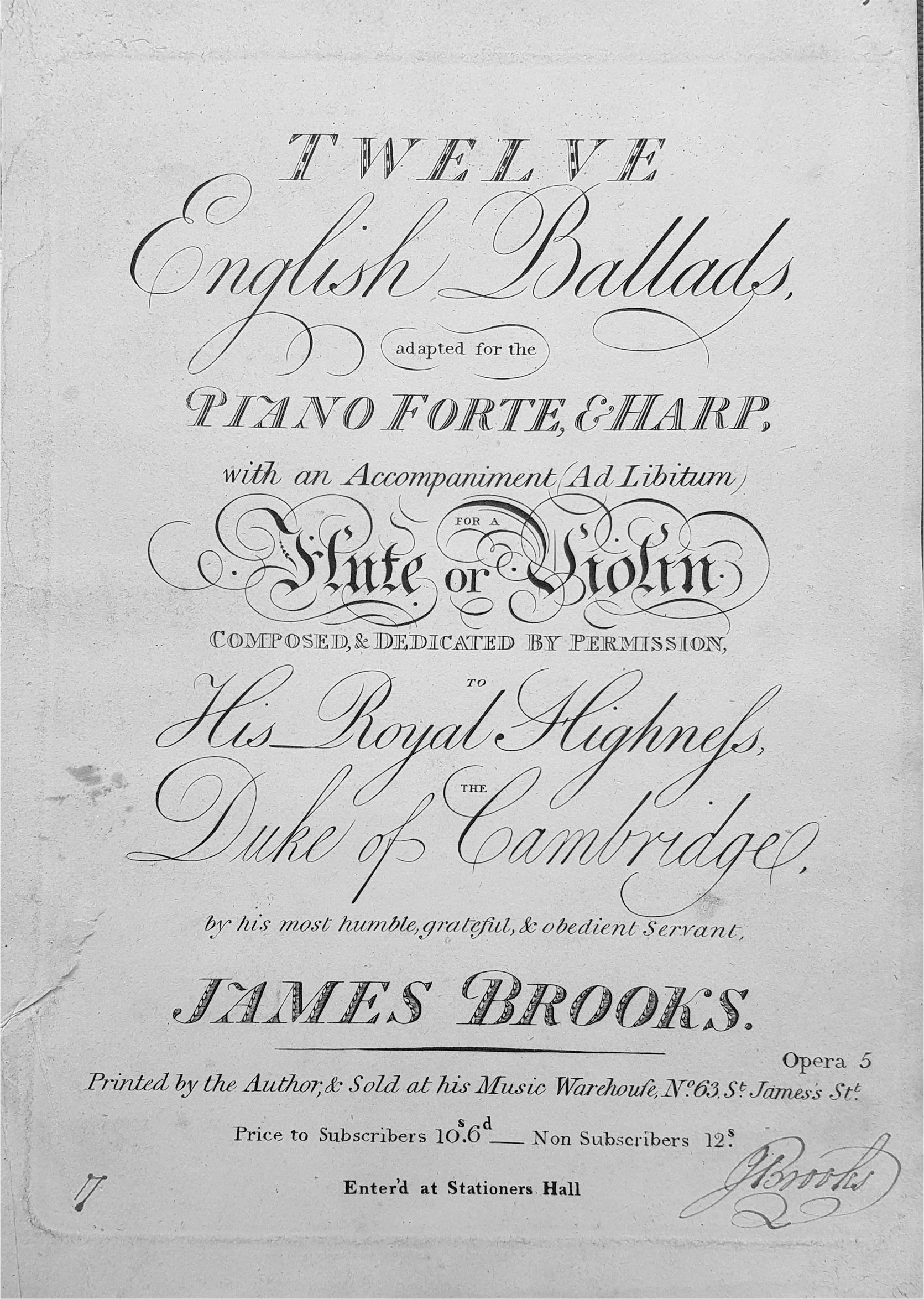

The issue of works by subscription was a common means of publication in eighteenth-century Britain although, certainly in regards to music publishing, it was a method that grew considerably in popularity as the eighteenth century progressed.Footnote 15 Evidence of this can be seen in the data where, of the publications recorded in Appendix B, the average year of publication is 1779 and the median year is 1786. The year with the most items issued by subscription was 1790 although, in reality, it is unlikely that this is the modal year, as since most items are not dated, the majority of dates are editorial and only approximate.Footnote 16 In England, the earliest known book produced by subscription was John Minsheu's (1560–1627) Ductor in Linguas from 1617; by the end of the seventeenth century, this method of publication had become a familiar concept, although it was still something of a rarity in music.Footnote 17 The earliest music-related work so far identified, for which a subscription list survives, is Thomas Mace's (c.1613–c.1706) Musick's Monument (1676), also the only work in this study from the seventeenth century.Footnote 18 Publishing by subscription was also not irreconcilable with individual patronage, where a work would be dedicated to a person of note in the hope of eliciting a financial reward. Some works, such as James Brooks’ (1760–1809) Twelve English Ballads (c.1805), employed both methods; in his case, the dedicatee was Prince Adolphus (1774–1850), the Duke of Cambridge and son of George III (Figure 3).Footnote 19 Issuing works by subscription was of clear benefit to composers, authors and editors who wished to undertake publication themselves, but did not have the means to finance such an expensive undertaking. Through subscription, it was possible to sell enough copies in advance to meet the costs involved in engraving the plates, undertaking any typesetting and the actual printing. Often, the title page would indicate as to who had undertaken the project through the addition of the phrase ‘for the author’ or something to that effect (Figure 3). However, such a marking in itself does not necessarily mean that a work was published by subscription and could instead mean that the composer or editor financed the publication themselves.Footnote 20

Figure 3. Title page to James Brooks’ Twelve English Ballads (c.1805), published and printed by the composer.

Those who paid to subscribe would often receive a discount on the intended sale price, and their name would be included in a list that was attached to the work. The title page to Brook's Twelve English Ballads, for instance, indicates that copies were 1s 6d cheaper for subscribers, but the inclusion of this information here is unusual, particularly since one would have expected the subscription process to have been largely complete by the time the printing of the title page was undertaken; it could be that Brooks had hoped to generate more subscribers for future publications by indicating that he offered a discount. Thomas Clark (c.1775–1859), in his A Sett of Psalm & Hymn Tunes (c.1800), advertised the second volume at the end of the first volume's subscription list; he reported that subscribers would receive a shilling off the full price (Figure 4).Footnote 21 There were various reasons as to why any individual might chose to subscribe. Naturally, many would have known the author personally and it is no surprise that, in the average list, a good number of the subscribers lived in the immediate vicinity of the composer's hometown or city. It is unsurprising, too, that a good number were professional musicians, some of whom subscribed reciprocally; others, particularly unmarried females, were probably pupils.Footnote 22 Further subscribers may have come into contact with the composer at the time a subscription was being taken, while some would have heard about the subscription through a notice, such as a printed handbill or a newspaper advertisement. The following example is typical:

To be published by Subscription,

Figure 4. Second page of the subscription list to Thomas Clark's A Sett of Psalm & Hymn Tunes (c.1800).

A COLLECTION of SACRED MUSIC, as used in

the Chapel of the KING of SARDINIA, in London.

Composed by SAMUEL WEBBE.

Subscriptions (10s. 6d. each) received at Longman and

Broderip's Music Warehouses, Cheapside and

Haymarket, and my Mr. Carpue, Duke-street, Lincoln's-

Inn-Fields.

*** To be delivered at Easter, after which, the Price will

be Twelve Shillings.Footnote 23

For some subscribers, particularly those in the upper classes, the presence of a list enabled them to demonstrate their patronage of the arts, and some would certainly have subscribed for outward show. This would to a degree also apply to the newly arrived members of the middle class; their inclusion would not only indicate their rise in affluence and social status, given that subscribing to new music was an expensive activity, but also provide them with a means by which their names might appear alongside those from the upper echelons of British society. For some, the music would almost certainly have been of less importance than the appearance of their name on the list; such subscribers may not even have minded if the music was of poor quality. A significant number of the clergy, who as well as being university-educated, were often capable musicians and drawn towards musical pursuits as amateurs, also tended to subscribe. Moreover, given the high incomes that many clergy received, they could afford to subscribe to the latest published works; some, such as William Felton (1715–69), were additionally active as composers and had their music published.Footnote 24

Gender and music in circa eighteenth-century Britain

Public music making was, during the long eighteenth century, a largely male-dominated activity. Professional musicians were, more often than not, men, and it was members of this gender that were primarily involved in concert promotion, theatre management and cathedral music.Footnote 25 Most female musicians, especially those of an upper or middling social status, had to be content with making music at home or in that of an acquaintance. There were of course exceptions to this rule, such as female organists or theatrical singers, but female performers often appear to have given up public music making once they were married.Footnote 26 Civic musicians, such as the town waits, were always, as far as current research indicates, male; this was also largely true of other town musicians, including the ‘blind fiddlers’. Again, there were exceptions, such as the female blind fiddler who perished in a fire in Mitchelstown, Ireland, in 1816.Footnote 27 However, her low social status would have meant that she would not have been bound by the norms that governed more polite society. Instruments such as the violin, flute, recorder, oboe, bassoon and cello were then seen, according to the lawyer Roger North (1653–1734), as more appropriate for men, as were thorough-bass instruments such as the organ, harpsichord and double bass.Footnote 28 Others, such as the physician John Berkenhout (1726–91), viewed the harpsichord as a more effeminate instrument and advised his son against its performance in public.Footnote 29

Suitable instruments for women, again according to North, were keyboard instruments such as the harpsichord or spinet, and stringed instruments such as the guitar or lute.Footnote 30 In the second half of the century the piano became the keyboard instrument of choice for most women.Footnote 31 The organ in some instances was also an acceptable instrument for a female to play and, for a few, it was a skill from which they might derive an income. Ann Howgill (bap. 1775), daughter of the Whitehaven organist William, was appointed organist at Staindrop Church, County Durham, in 1793 and then Penrith in 1797.Footnote 32 Other well-known female organists include Ann Valentine (bap. 1762–1842) of Leicester, and Mary Hudson (d.1801) and Theophania Cecil (1782–1879) of London.Footnote 33 Women were, as a rule, prohibited from playing instruments that involved blowing or were held in slightly awkward or unsightly ways. Richard Leppert pointed out that the flute had phallic associations and, as such, was viewed as an improper instrument for a woman, although they could still play the flageolet.Footnote 34 The common prejudices at the time are evident in the writings of the dancing master, John Essex (c.1680–1744), who said that:

The Harpsichord, Spinet, Lute and Base Violin, are Instruments most agreeable to the LADIES: There are some others that really are unbecoming the Fair Sex; as the Flute, Violin, and Hautboy; the last of which is too Manlike, and would look indecent in a Woman's Mouth; and the Flute is very improper, as taking away too much of the Juices, which are otherwise more necessary employ'd, to promote the Appetite, and assist Digestion.Footnote 35

Members of the upper classes would have learnt music in their youth, principally through private tuition, although again it was different between the genders. For boys, music was of little importance to their education; they tended to be taught in areas such as mathematics, languages, geography, history and the Classics. If they did study music, it was usually as an optional extra. For upper-class ladies, who had few opportunities outside the home, their education tended to have a focus on languages, needlework, music and dancing.Footnote 36 Many held music as a particularly important attribute for a lady. As Essex observed: ‘Musick is certainly a very great Accomplishment to the LADIES; it refines the Taste, polishes the Mind; and is an Entertainment, without other Views, that preserves them from the Rust of Idleness, the most pernicious Enemy to Virtue.’Footnote 37 Mary Granville (1700–88), who became Mrs Delaney, echoed this when she wrote: ‘There is, I think, no accomplishment so great for a lady as music, for it tunes the mind.’Footnote 38

For many parents, music became an important asset to their daughter's future.Footnote 39 Understandably, music developed into a passion for some, but for others, it was a means by which they might entice a husband. Existing evidence suggests that such women usually gave up music once they were married.Footnote 40 For the middling classes, music was an attribute to be admired and adopted in the hope that it would raise their social standing. Allatson Burgh (1769–1856) observed in the early nineteenth century that:

In the modern System of Female Education, this fascinating accomplishment is very generally considered, as an indispensable requisite; and the Daughters of Mechanics, even in humble stations, would fancy themselves extremely ill-treated, were they debarred the Indulgence of a piano-forte … . Music is not only a harmless amusement; but, if properly directed, capable of being eminently beneficial to his fair Countrywomen. In many instances, it may be the means of preventing that vacuity of mind, which is too frequently the parent of libertinism; of precluding the intrusion of idle and dangerous imaginations; and, more particularly, among the Daughters of ease and opulence, by occupying a considerable portion of time, may prove an antidote to the poison insidiously administered by the innumerable licentious Novels, which are hourly sapping the foundations of every moral and religious principle.Footnote 41

However, what the more widespread production of domestic music did was to make a pastime that had been largely restricted to the upper echelons of society, ordinary. Richard Lovell Edgeworth (1744–1817), and his daughter Maria (1768–1849), observed at the dawn of the nineteenth century that:

Every young lady (and every young woman is now a young lady) has some pretensions to accomplishments. She draws a little; or she plays a little; or she speaks French a little … . Stop at any good inn on the London roads, and you will probably find that the landlady's daughter can shew you some of her own framed drawing, can play a tune upon her spinnet, or support a dialogue in French … .accomplishments [that] have lost much of the value which they acquired from opinion, since they have become common … . In a wealthy mercantile nation there is nothing which can be bought for money, that will long continue to be an envied distinction.Footnote 42

That being said, many of the aspiring middle classes would have found it difficult to pay for private music tuition for their daughters. If they could afford to send their daughters to a boarding school, then they would have received the opportunity to learn music; these lessons, however, tended to be done in groups, which restricted the amount of time a teacher could spend with each student. Edward Miller, who had undertaken some of this type of teaching himself, observed that such girls ‘seldom make any great progress in Music’. He found that ‘the shortness of time a Master can allow to each Scholar, where there are numbers to be taught’ detrimental, since ‘a Master cannot allow a sufficient time to each Scholar for compleating [sic] these purposes; if, while he is engaged with one only, all the rest are unemployed.’Footnote 43 As a result, one suspects that those who learnt music in this manner would have only developed a very rudimentary level of skill and that, consequently, the quality of music produced in the average household could not have risen particularly high.

Overall subscribers before 1820

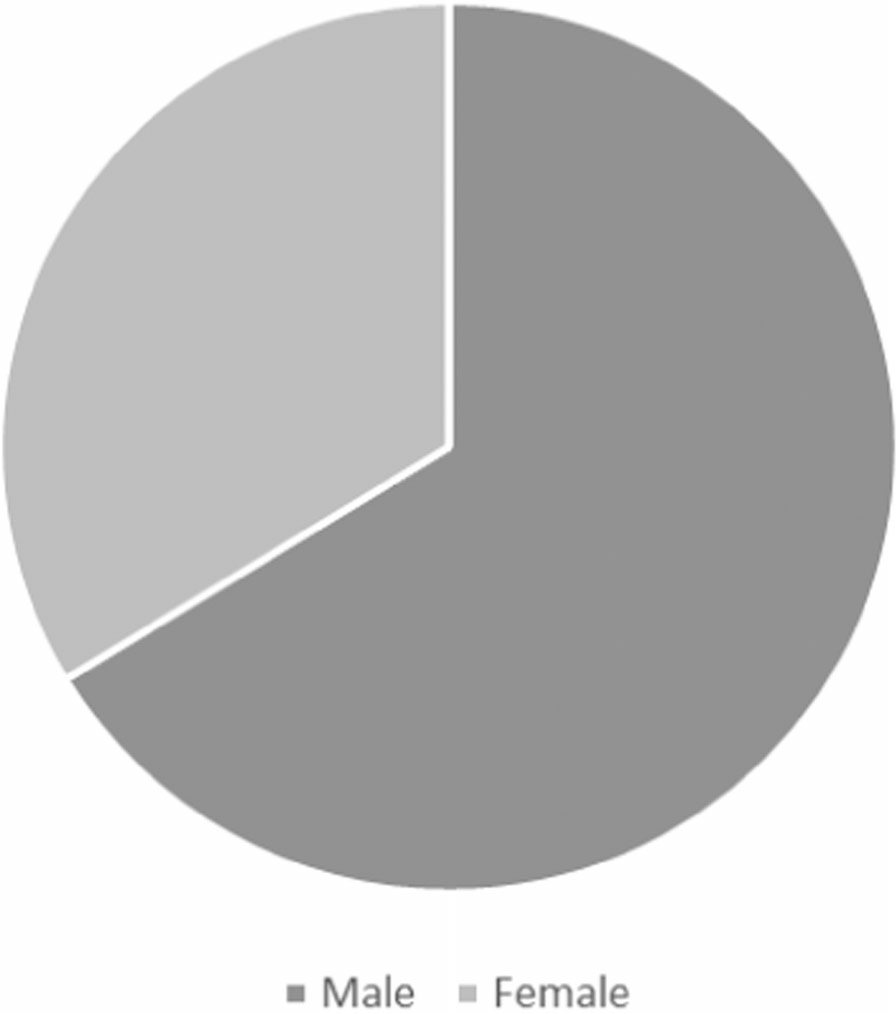

When the data in appendices A and B is examined, the total number of subscribers in the 557 lists is 116,310. Of these, 87,549 were male and 26,815 female, with 1,946 in the other or institutional category. This data is presented as a pie chart in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Subscribers to all works examined in Appendix B.

The first observation to make is that publishing by subscription was an endeavour that primarily targeted individual subscribers. If it had been aimed at institutional subscribers, it is unlikely that publishing by subscription would have been a success, given that only 1.7% of subscribers fall into the ‘other’ category. This chart also strongly indicates that music subscription was, throughout the time period examined, a predominantly male-dominated activity, with 75.3% of subscribers being of this gender and 23.1% female.Footnote 44 This data will, to some degree, be influenced by the situation at home, where the eldest male most likely controlled the purse strings and would have presumably paid for the subscription even if the music were intended for a female family member.Footnote 45 When the data is broken down into 20-year periods in time, starting from 1720, a general trend is revealed; the data in the earliest two groupings from 1680 has been omitted as these are unlikely to be representative, given that only one work from each time period was examined (Figures 6–10).Footnote 46

Figure 6. Subscribers 1721–40.

Figure 7. Subscribers 1741–60.

Figure 8. Subscribers 1761–80.

Figure 9. Subscribers 1781–1800.

Figure 10. Subscribers 1801–20.

It is evident from this series of pie charts that music subscription before 1820 was overwhelmingly male-dominated but, towards the end of the eighteenth century, the proportion of female subscribers increased so that, by the early nineteenth century, 28.4% of subscribers were members of this gender. This will be, to a degree, representative of changes in society during this period, with an increasing number of women having the financial freedom to subscribe under their own names. However, this data suggests that music subscription may have been more progressive in terms of gender equality than other types of subscription. Leonore Davidoff and Catherine Hall examined the extant subscription lists of the societies based in Birmingham between 1780 and 1850 to find that ‘at most women constituted 10 per cent of the subscribers’.Footnote 47 Six works included in Appendix B were published in Birmingham and, when their attached lists are viewed as a whole, 20.1% of the subscribers were female. Of these, the highest proportion of female subscribers was to James Lyndon's Six Solo's for a Violin (1751), where 40% of his subscribers were of this gender.Footnote 48

Those in the ‘other’ category remained only a tiny proportion of the total subscribers, with a marginal increase in the number of these subscribers from the 1740s through to the end of the century, which dropped slightly at the start of the nineteenth.

Sacred and secular music

Of the lists examined, 26.6% were attached to works primarily intended for sacred purposes, – whether that was collections of hymns, psalm-tunes, anthems or organ voluntaries – although, naturally, much of this music could also be performed in a secular environment.Footnote 49 That means that the majority of works published, 73.4%, were intended for secular use. This will again be representative of wider trends and indicates that there was a greater demand for secular music than sacred. However, the data also suggests that publication by subscription may have been more commonly employed for the publication of sacred music as, when one examines William Smith and Charles Humphries’ catalogue of the publications issued by John Walsh between 1721 and 1766, of the 1,564 numbered items, only 45 (2.9%) were intended for sacred purposes.Footnote 50 The subscription data also indicates that secular music was more popular than sacred music with female subscribers, attracting a higher proportion (25.7% against 15.7%). Sacred music did, however, attract more institutional subscriptions, particularly from cathedral deans and chapters and choral groups (3.6% sacred against 1% secular).

Subscribers to works by Handel

Of all the composers represented, it was Handel whose music was most commonly issued by subscription. Appendix B contains 57 items associated with this composer, including arrangements of his music by others and William Coxe's (1748–1828) book of Anecdotes (1799).Footnote 51 This is far higher than the ten items that David Hunter and Rose Mason identified, although they primarily limited their research to publications issued during Handel's lifetime.Footnote 52 The 57 items constitute 10% of the total lists examined. What is perhaps most interesting is that Handel did not take responsibility for issuing the works himself. The only work by him published ‘for the author’ is his 1740 set of Twelve Grand Concertos. Apparently, his publishers were happy enough to take responsibility for the publication of his works themselves, perhaps assuming that Handel was a well-known and highly regarded composer whose music was going to sell. However, the numbers of his subscribers do not indicate this at first glance. The average number of subscribers per list comes out at 209 while, for Handel, this works out as 187. When one only examines those lists issued in his lifetime, then the average number of subscribers is 104. These lists were issued between 1725 and 1740 and when all the lists from the same period are examined, the average comes to 189. So, the question is: why did Handel's music attract so few subscribers? Much of this could have been due to the way in which members of the public purchased Handel's music, where significantly more copies would be purchased after publication. Customers could come across the score or set of parts in a shop and, either having already heard the music at a concert, or being aware of the esteem in which the composer was held, would purchase a copy. The publication by subscription could have been a tactic employed by the publishers John Cluer and John Walsh to sell extra copies to those who were more interested in having their names included in the list than in the music itself.Footnote 53 Handel's music did grow in popularity after his death, with the average number of subscribers in the posthumous lists being 213. This figure includes the collections of his music produced by John Clarke-Whitfield (1770–1836), the second edition of which had an impressive 730 subscribers. When we examine the breakdown by gender, overall it reveals that Handel was more popular with a male audience, with 80.4% of subscribers being of this gender. This is only slightly above the total percentage of male subscribers before 1820 (75.3%).

When comparing the percentage of subscribers from before and after Handel's death, the breakdown between genders remains largely static, with 16% of subscribers being female, increasing to 17.2% after 1759. For Arnold's edition of Handel's music, 22% of subscribers were female, which can be accounted for in the general trends at the time, although it is important to note that a significant number of women continued to have an interest in Handel's music 30 years after the composer's death; this indicates that some women's taste in music was not merely driven by the fashion for what was new.

Subscribers by country

When the subscriptions are broken down by country some interesting trends emerge. Firstly, that there were proportionally more institutional subscribers to works issued in England.Footnote 54 Only one of the works issued in America had any institutional subscribers, and the sole work from India examined had none. This was presumably due to the situation in these countries, where there would have been far fewer formal organizations than in Britain, and certainly few that saw a benefit in subscribing to any of the works examined.Footnote 55 Some foreign-based groups did, however, subscribe to musical works published in Britain; for instance, a musical society based in New York subscribed to Capel Bond's (c.1730–90) Six Anthems in Score (1769).Footnote 56 The proportion of female subscribers is largely the same in England (23.3%) and Ireland (22.2%), with a reduction for both America (6.4%) and India (15.4%).Footnote 57 Scotland overall had a similar proportion of subscribers to England and Ireland (22.2%) but, as this research only includes 26 works issued in this country, small changes to the selection produces a markedly different figure. For instance, if we exclude the works issued in Scotland that contain no music notation, then the proportion of female subscribers increases to 36.1%.

If we look at those works issued in the capital cities of England and Scotland, the disparity in the proportion of subscribers is more evident. London was, at this time, one of Europe's most important centres for music production, so it is unsurprising that 424 (76%) of the works examined in this study indicate that they were published in this city.Footnote 58 Of the total number of subscriptions taken, 70% were to a London-published work. The 23.7% of female subscribers discovered across all the London-published works is not dissimilar to England as a whole (23.3%).

In Scotland's capital city of Edinburgh, the proportion of subscribers is markedly different to London, where 36.1% of subscribers were female. Much of this will have been due to differences, both socially and culturally, with more females having the means and freedom to subscribe. It also indicates that music in this city may have been an art more strongly associated with women and that it was one area where female patronage was particularly acceptable.

The differences between the Enlightenment culture in England and Scotland has already been discussed by Rosalind Carr, who observed that Scottish Enlightenment had a ‘specific national character’, evidence of which can be seen in the ‘different character of women's involvement’.Footnote 59 Nevertheless, Carr also observed that ‘Scottish intellectual culture was still manifestly male’. She went on to assert that:

Women were involved in informal, tea-party intellectual conversation, but they were excluded from intellectual clubs and their contribution to print culture was negligible … . Only in the early 1800s did female writers such as Elizabeth Hamilton orientate themselves towards the Scottish capital, and this orientation suggests a major cultural shift as Scotland entered the nineteenth century … . [Nevertheless,] time spent in Edinburgh or London participating in the social circuits of visiting, balls, and promenading was deemed to be an essential component of the education of elite young Scotswomen.Footnote 60

Carr did note, however, that from 1775 women were permitted to attend the debates of the Edinburgh Pantheon Society, and could even vote upon each meeting's discussion; she also observed that, from the 1790s, there was ‘increased female involvement in intellectual associational culture’.Footnote 61 This change in the position of women in Edinburgh society is also event in several music works, issued there in the final decade of the eighteenth century, which received considerably more female subscribers than male.

John Watlen, Natale Corri and John Valentine

The two sets of The Celebrated Circus Tunes (1791 and 1798) produced by the music publisher and composer John Watlen (c.1764–1833), received together 329 subscribers, of which an impressive 76.9% were female.Footnote 62 Watlen was well established in Edinburgh, where he had his own shop from which he could promote his forthcoming publications to potential subscribers, and was active as a music teacher; no doubt many of the unmarried females were pupils.Footnote 63 If we examine a breakdown of female subscribers to his first set of circus tunes, it is apparent that the majority (70%) of his female subscribers gave their title as ‘Miss’ (112 subscribers). This perhaps gives some indication of not only how large Watlen's teaching practice was, but also that, in the 1790s, domestic music production was booming among Edinburgh's young ladies, some of whom presumably were not only aspiring to rise socially, but also wanted to imitate the fashion for music south of the border (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Titles of Female Subscribers to John Watlen's The Celebrated Circus Tunes (1791).

Note: This data is based on the titles as given in the lists, whether this is Mrs, Miss or an aristocratic title. In reality some of those with aristocratic titles would have been married, others not, while some of those who are titled ‘Miss’ would have been from aristocratic families.

Watlen's subscribers were by no means limited to Scotland, and his lists include several from the North-East of England. One of the most notable of these is the organist of Durham Cathedral, Thomas Ebdon (1738–1811), who subscribed to the second collection. At this time, Edinburgh had grown significantly as an important centre for the publication of music; evidence of this can be seen in Frank Kidson's book on music publishers where, of the 36 Edinburgh-based printers and publishers he mentions, 17 (47%) were active in the 1780s and 1790s, as opposed to two (6%) before 1750.Footnote 64 Among the list of musicians from Newcastle and Durham to have works published in Edinburgh at around this time, and mostly by Watlen, we find Ebdon, the Durham Cathedral lay-clerks John Friend and Charles Stanley, and the Newcastle organists Thomas Hawdon (c.1765–93) and Thomas Thompson (1777–1830).Footnote 65

Watlen, given his occupation, would have been astutely aware of what sold well, and aimed his circus music specifically at the amateur keyboard market. There was clearly a vogue for circus-related music at this time, presumably as a result of the establishment, in 1790, of the Edinburgh Equestrian Circus, an adjunct of both the London-based Sadler's Wells and Royal Circus.Footnote 66 The pieces in Watlen's collection are relatively simple and suitable for a keyboardist of limited skill; they make use of typical left-hand devices such as the Alberti bass, broken chord figurations and parallel octaves. Much of the melodic material is based upon traditional Scottish music and it is certainly possible that the right-hand part could be played on an instrument such as the flute or violin. Walten was himself a prolific publisher of traditional Scottish music, or music that he composed in that style, which he arranged for piano.

Further evidence of this wider shift in the position of Edinburgh-based women as musical patrons can also be seen in the published works of Natale Corri (1765–1822), the younger brother of Domenico (1746–1825). He, like Watlen, was involved in music publication through his family firm Corri & Co., a business that had close connections with the London-based firm of the same name.Footnote 67 He also taught music, with the Irish tenor and theatre manager, Michael Kelly (1762–1826), referring to him as ‘the first singing master in Edinburgh’.Footnote 68 For Corri's Op 1 Three Sonatas, for the Piano Forte of Harpsichord, an astounding 91% of his subscribers were female.Footnote 69 This will again reflect his teaching practice, which primarily focused on the musical education of unmarried women; those titled ‘Miss’ accounted for 84% (103) of his subscribers (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Titles of the Female Subscribers to Natale Corri's Three Sonatas, op. 1 (c.1790).

As Watlen's and Corri's collections were published at around the same time, and are both primarily intended for performance on a keyboard instrument, one would expect some individual subscribers to appear on both lists, which they clearly do. However, due to the lack of information provided in the lists it is impossible to determine an exact number of those who subscribed to both works, although the number could potentially be as high as 30. This would mean that around 9% of Watlen's subscribers also subscribed to Corri; for Corri, it could have been 22% of his subscribers who also subscribed to Watlen. This indicates that both musicians had their own circles from which they might solicit subscriptions but, naturally, as they were both located in Edinburgh, there was some crossover between the two. However, this data also indicates who the most prominent music publisher was and who appears to have had the largest teaching practice.Footnote 70

At the other end of the spectrum was the Leicester-based musician, John Valentine (1730–91). He, like his Edinburgh counterparts, was active in music tuition, but the breakdown of his subscribers by gender paints a very different picture, where only 1.9% of his subscribers were female.Footnote 71 This indicates that Valentine's teaching practice, unlike that of his Edinburgh counterparts, was dominated by male students.Footnote 72 On the one side, it is no surprise that his Eight Easy Symphonies (1782) had no female subscribers.Footnote 73 The instruments they employ, and the fact that such works were intended for public performance, made them unsuitable for women. However, one might have expected some of his female supporters to have subscribed as purely a supportive measure or for outward show, which they clearly did not. For his other two works, his Thirty Psalm Tunes (1784) had only one female subscriber, and for his sole theatrical work, The Epithalamium in the Tragedy of Isabella (c.1765), only 4.7% of his subscribers were female.Footnote 74 Ultimately, many of Valentine's subscribers may have come from any male-only clubs in which he was involved, such as local music societies or the freemasons, but the subscription lists attached to his works even stand in stark contrast to the other London-published works of this period.Footnote 75

Music for strings

Given what we have already observed in relation to Valentine's symphonies, one might have expected orchestral works, such as concerti grossi, to have had few or no female subscribers. However, such an observation would be inaccurate, as a substantial 16% of subscribers to such works were women. The resistance to women playing stringed instruments has already been discussed; however, some are known to have played the violin in private. Elizabeth Ford reported on two female violinists, Lady Sophia Hope (d.1813) and Elizabeth Rose of Kilravock (1708–89).Footnote 76 The judge, historian and antiquary, Cosmo Innes (1798–1874), said of the latter:

She sung the airs of her own country, and she had learnt to take a part in catches and glees to make up the party with her father and brother. The same motive led her to study the violin, which she played admirably, handling it like male artists, supported against her shoulder.Footnote 77

Women could also have played the harpsichord part, although it was unlikely that they would have done so in public. However, some women were able to play a thorough bass, including Grisie, the eldest daughter of Lady Grisell of Mellerstain House, Berwickshire.Footnote 78 In addition, the 25.2% of female subscribers to George Jackson's A Treatise on Practical Thorough Bass … Op. 5 (1791) suggests that a significant number of women did indeed learn to play a figured bass.Footnote 79

The nature of concertos meant that it was usually possible to play them as quartets, and they were certainly known to have been played this way in the nineteenth century.Footnote 80 The Newcastle composer, Charles Avison (1709–70), in an attempt to increase sales, indicated that his op. 9 concertos (1766) were performable as concertos, quartets or keyboard solos, and he included a partially completed keyboard part to facilitate this. Avison was a prolific composer of concerti grossi, issuing six sets of six or more, including his set of Twelve Concerto's…done from the two Books of Lessons…by Sigr Domenico Scarlatti (1744). When the subscribers to these six works are compared, an average of 15.9% of his subscribers were female, which is comparable to the overall proportion for concerti grossi (16%). This is a slight increase on the proportion received for his op. 2, where 8.2% were female; this had risen by the time of his op. 4, where 19.2% were members of this gender.

Given that by including a realized keyboard part Avison was making his op. 9 concertos more suitable for the female domestic performer, one might have expected him to receive an increase in the number of this type of subscriber. Although Avison did receive, when compared with the op. 4, an extra 55 subscribers, the list to book 2 records that still only 19% of the total were female, indicating that the inclusion of a partially realized keyboard part did not make much of an impact. This could possibly be why Avison returned to a more standard thorough-bass part for his 1769 op. 10 concertos.

Keyboard concertos, like concerti grossi, were also intended for orchestral performance, but they tended to be arranged with a self-sufficient keyboard part, enabling their performance either as keyboard solos, or with one or more of the accompanying string parts. Such works understandably attracted more female subscribers, with 34.9% overall being female. Avison's only published keyboard concerto, the 1742 Two Concertos, did not come close to this, where a mere 11.8% were female.Footnote 81 Nevertheless, other composers did much better at appealing to female subscribers. The proportion of female subscribers to the two sets of keyboard concertos by the organist at Bath Abbey, Thomas Chilcot (c1707–1766), is 30.1%. However, this figure should not be taken at face value, as even if Chilcot did attract more subscriptions from women, he was not able to attract anywhere near as many subscribers in total for his first set (101) as Avison did for his op. 9 (253).Footnote 82

The trio sonata, although clearly more suitable for domestic performance than the concerto, was again string dominated, and, as such, primarily aimed at the male subscriber. Only 11.6% of the subscribers to such works were female, so less than what was typical for the string concerto (16%). Given that the type of instruments employed are the same as the concerto grosso, the use of strings cannot account for this difference. A possible reason could be the way in which subscribers were made aware of such works. Women who attended concerts would hear concertos performed and, if they knew the composer, may have decided to support them through subscription. There is some evidence of this in the lists themselves, such as in Avison's op. 4.Footnote 83 When one examines the non-aristocratic female subscribers who gave a place of residence, it is striking that most lived relatively close to Newcastle. Male subscribers could be located much further afield and this implies that it was they who responded to published advertisements. By implication this means that many female subscribers to Avison's concertos may not have utilized the music themselves.Footnote 84 Trio sonatas, which were primarily intended for domestic use, would have not have been as frequently performed at concerts, and certainly not in the lead-up to publication, which could account for the drop in the proportion of female subscribers.

Keyboard music

In terms of keyboard music, there was a substantial number of publications produced, aimed at those who wanted to perform such works domestically. There were essentially two types of keyboard sonata in this period: there are those that were issued with accompaniments and those that had none. Nevertheless, even when accompaniments were provided, the keyboard part was usually self-sufficient and could be performed on its own. The accompaniments themselves tended to be fairly simple and intended for performers with only a rudimentary skill. As expected, this genre was more popular with females, who account for 46.7% of the subscribers, than some of the genres previously discussed. With sonatas for solo keyboard, the proportion of female subscribers is higher still, achieving 49.4%. Given Michael Cole's observation that, in c.1765, around ‘eighty percent of [pianoforte] players were female’, the subscription list data indicates that a significant number of men did indeed subscribe on behalf of a female relative.Footnote 85 This data, however, only includes works that were entitled ‘sonatas’, while this term was interchangeable with ‘lessons’. Prior to 1756, all published keyboard sonatas in Britain were called lessons, irrespective of whether they were intended for tuition or not. Sets of lessons for keyboard had been published as far back as the seventeenth century, for example, those in Matthew Locke's 1673 collection, Melothesia: or, Certain General Rules for Playing upon a Continued-Bass.Footnote 86 Avison was the first British composer, in 1756 with his op. 5, to refer to his published keyboard works as ‘sonatas’. Curiously though, works called ‘lessons’ tended to attract proportionally fewer female subscribers (43.2%).

The organist of St Mary's, Nottingham, Samuel Wise, issued a set of keyboard works entitled Six Lessons for the Harpsichord in around 1763.Footnote 87 His six lessons are essentially multi-movement sonatas that incorporate a range of dances, including the allemande, courante, gavotte and jig; in this sense these are not too dissimilar from Locke's much earlier examples. The difficulty ranges from simple two-part textures through to the more challenging crossing of hands and demi-semi quaver runs. The range of different techniques employed indicates that this set was primarily put together as an aid to develop keyboardist technique and presumably would have been used by Wise as part of his teaching activities. However, as pieces of music for performance they are rather insipid. Wise's set attracted a higher proportion of female subscribers, with 118 (60%) being of this gender. Of the female subscribers, 100 (51% of the total) were unmarried. Many of them would have been Wise's students and would have purchased a copy for their own use. One of the married subscribers was Mrs Mary Gawthern, who most probably purchased a copy for the use of her daughter, Margaret.Footnote 88 It is also interesting that around a third of Wise's male subscribers (33%) were professional musicians, which gives some indication as to not only how well connected he was, but also to how few men might have bought this set for their personal improvement or pleasure.Footnote 89 Others, who presumably did not subscribe to use the music themselves, include the booksellers Daniel Fox of Derby and Mr Ward of Nottingham, and the Nottingham-based printer and publisher Samuel Creswell. It was not unusual for those in the book trade to appear in subscription lists, and they frequently purchased more than one copy of any individual work.Footnote 90 Their subscription, as well as demonstrating their support for the arts, could also be a way of advertising their business. In addition, any copies subscribed to would have been purchased at a discount and could then be sold on at full price in their shops.

Another popular genre of keyboard music was the organ voluntary. Although such works were, by their very nature, intended for use in church, the absence of pedals on British organs of this period meant that such pieces were playable on a variety of keyboard instruments and in both sacred and secular environments. In addition, such works could be very secular in style and, one wonders, given the more austere type of worship that was prevalent in the eighteenth century, if some examples were ever viewed as suitable for religious purposes.Footnote 91 Given that voluntaries could be played at home, one might have expected such works to attract a relatively high proportion of female subscribers, but only 27.3% were members of this gender, indicating that this genre was more closely associated with the male performer than other forms of keyboard music.

Ignace Pleyel

One distinct anomaly in the London-originated subscription lists is that to the arrangement of Ignaz Pleyel's (1757–1831) Three Celebrated Trios, produced by the harpist, John Elouis (1758–1833).Footnote 92 Although arranged as harp sonatas they, for the most part, are performable on a keyboard instrument. Of the subscribers, 91.2% were female. There are several reasons as to why this work might have received such a high proportion of female subscribers. Firstly, that the majority of subscribers, one assumes, were his female students. Secondly, that the harp was a predominantly feminine instrument, which would account for the low number of male subscribers (five in total). Such a view is supported by another collection of harp music, a Notturno & Quintetto, for the Harp … . Op. 14, by Marie Marin that attracted 142 subscribers, of which 72.5% were female.Footnote 93 A third possibility is that Pleyel's music was particularly popular with female amateurs. One cannot deny that Pleyel's music was held in particularly high esteem during the 1790s. As Rita Benton observed, the ‘most telling evidence of the appeal [of Pleyel] … lies in the thousands of manuscript copies that filled the shelves of archives, libraries, churches, castles and private homes and in the thousands of editions produced in Europe and North America.’Footnote 94 However, there is some evidence that the popularity of Pleyel's keyboard works lay with the female music-buying public, while his string music was more popular with men. The catalogue of the music assembled by Henry, the Tenth Earl of Exeter (1754–1804), contains two sets of string quartets by Pleyel, but none of his keyboard music. The one keyboard sonata by Pleyel in the Burghley House collection belonged to Isabella (1803–79), wife of Brownlaw, the Second Marquess of Exeter (1795–1867).Footnote 95 There is also a substantial amount of Pleyel's keyboard music in the collection at Tatton Park in Cheshire that once belonged to Elizabeth Egerton (1777–1853), and in the collections that belonged to Jane Austen (1775–1817) and Tryphena Wynne Pendarves (1780–1873).Footnote 96 Further research into the ownership of Pleyel's music may shed more light onto this matter, but this last point raises an interesting possibility, particularly when the ratio of subscribers to Handel's music is taken into account: certain composers could be more popular with women than men and vice versa.

Music and dance tutors

Given that most women learnt the rudiments of music as part of their schooling, one might expect that, unless they wished to push their musical knowledge above a basic level, few women would subscribe to music tutors. Edward Miller, writing in 1771, observed that there was a ‘great deficiency of Ladies in general with regard to the grammatical part of Music’ but thought: ‘Perhaps it is not necessary for them to enter into the Minutæ of the Science.’Footnote 97 Leppert also pointed out that, for men, the purchase of a book of lessons could be a means by which a gentleman might avoid dependence on a socially inferior music master while, for women, it might help reduce the need to spend money on a teacher.Footnote 98 However, such works were clearly more successful with men, who account for 83.6% of subscribers.Footnote 99

Given the resistance there was to female string players, it comes as no surprise to find that no ladies subscribed to John Gunn's (c.1765–c.1824) The Theory and Practice of Fingering the Violoncello (c.1790).Footnote 100 One may have expected a few female subscribers, purely as a supportive measure, or purchases on behalf of another family member, but it is possible, given the way a cello was held, that women did not want to be associated with what was then viewed as a distinctly masculine instrument. Nevertheless, there was an appreciable number of female subscribers to works advertised as being for the cello, such as the 21.5% who subscribed to Giacob Cervetto's Twelve Solos (1748).Footnote 101 Michael Talbot did wonder as to whether ‘one or two of them [Cervetto's subscribers] played the cello’, but thought that the majority probably subscribed for other reasons.Footnote 102

Tutors were also available for those who wanted to learn how to dance, a pastime favoured by both genders. As well as the health benefits of this activity, it also helped in the development of a good posture, greater social confidence, and the acquisition of a more assured bearing in any social situation.Footnote 103 It was also an important social pastime, with people attending balls and assemblies to see the great and good of local society, and to be seen themselves. Judith Milbanke (1751–1822) of Seaham Hall, County Durham, often recorded in her letters the events she had attended and whom she met. In July 1779, she attended the Durham race week, for which she wrote:

I danced a good deal at both Balls, at the first with Sir John Eden, at the second with Mr. Gowland: I made Count Yeo dance a Minuet to the entertainment of the whole Room by betting him a Guinea he would not which alas! I was obliged to pay! [Sir Ralph] Milbanke danced Minuets without end, and one night opened the Ball with the beauteous Countess of Strathmore.Footnote 104

Girls were taught to dance at an early age, and often at schools in groups.Footnote 105 Men, even though dancing was an important social activity, did not, so it is not surprising that most subscribers were male (57%). However, this does not provide a complete picture as Pemberton's 1711 instructor had no female subscribers, Tomlinson's 1735 primer had 112 male subscribers and 57 female, while Gallini's c.1770 primer had 218 female subscribers and only 195 male. When placed as a series of pie charts, the results give a clear indication that, as the eighteenth century progressed, books on dancing became increasingly popular with female subscribers (Figures 13–15).

Figure 13. Subscribers to E. Pemberton's An Essay for the Further Improvement of Dancing (1711).

Note: Viewed on ECCO.

Figure 14. Subscribers to Kellom Tomlinson's The Art of Dancing (1735).

Note: Viewed on ECCO.

Figure 15. Subscribers to Giovanni-Andrea Gallini's Critical Observations on the Art of Dancing (c.1770).

Note: Viewed on ECCO.

This trend is probably representative of changes in society over the course of the century. Early on, most women would have learnt dancing as part of their education and had little need of a printed tutor, although it is certainly possible that a father might have subscribed under his own name when the book was intended for the use of a daughter. For men, dancing, as Leppert observed, increasingly became a required skill, although there were those who never learnt how to dance as a child, as the activity was frowned upon by a parent, and would have need for such a book.Footnote 106 Nevertheless, dancing became an activity enjoyed by all, a trend that ultimately blurred the distinction between the classes.Footnote 107 Events such as balls and assemblies became increasingly commonplace over the course of the eighteenth century and musical events, such as concerts, often concluded with a ball; there were also standalone balls, timed to coincide with important local events, such as race week.Footnote 108 Another factor in the growth in the number of female subscribers could have been the rise of the expanding middle classes, where presumably some of the women would have needed to learn how to dance, having not received a private education.

Vocal music

Given the association of cathedral music with male choirs, one would naturally expect there to be few female subscribers to such works, and this is certainly true of the two important collections of Cathedral Music by Boyce and Arnold. Only 4.6% of their subscribers were female, which is considerably less than the 17.4% in the ‘other’ category, the latter primarily made up of cathedral deans and chapters who purchased this music for the use of their choirs. When we examine Boyce's set more closely, in becomes apparent that the first edition did not appeal to women at all, as it attracted a single female subscriber, Miss Mary Ann Chase, who only subscribed to the first volume.Footnote 109 The poor reception greatly disappointed Boyce, who then decided against the publication of his own anthems, although his widow ultimately issued two collections in 1780 and 1790.Footnote 110

There was in England at this time a movement that aimed to, as Stanley Sadie put it, ‘retain the “ancient” style’ of music.Footnote 111 Two of the most notable groups associated with the performance of old music were The Academy of Ancient Music and The Madrigal Society. There were also some prominent musicians researching the music of the past, including Johann Christoph Pepusch, Charles Burney, John Hawkins, Maurice Greene and Boyce. Some composers even attempted to adopt the manner of the past, producing works such as madrigals.Footnote 112 However, the majority of those interested in the music of the past were male, with little interest in this area shown by women. Nevertheless, as time went on, it is clear that a small but increasing number of women did cultivate an interest in old music, including Elizabeth Egerton, whose brother presented to her a four-volume set of anthems, odes and other works by Henry Purcell, which had been transcribed by Philip Hayes between 1781 and 1785, and had formerly belonged to Samuel Arnold.Footnote 113 The 1788 reissue of Boyce's Cathedral Music was far more successful than the first edition, having more than three times the number of subscribers, of which an appreciable 8.9% were female.Footnote 114 Arnold's collection of Cathedral Music attracted a small number of female subscribers (4.1%), while the 1801 collection of Thomas Morley's Canzonets and Madrigals attracted 238 subscribers, of which 36 (15.1%) were female.Footnote 115

When we look at anthems in general, there are proportionally more female subscribers, but again the percentage is low, only 15.6%. However, this increase from the sets of Cathedral Music by Boyce and Arnold was probably because it was easier to convince a potential subscriber to purchase a copy of newly composed music, rather than an edition of old works. Collections of hymns and psalms attracted a slightly lower proportion of female subscribers (15.1%), presumably as most church choirs, like those in cathedrals, were often formed from men and boys.Footnote 116 Even Edward Miller's landmark collection, The Psalms of David (1790), which attracted 2,603 subscribers, had only 386 that were female (14.8%).Footnote 117 This indicates quite clearly that even simple parochial music was more popular with men.Footnote 118

Even if men more commonly subscribed to sacred and ancient vocal music, singing was an activity, much like dancing, that was popular with both genders. Collections of secular vocal music, however, still tended to attract more male subscribers, but a greater proportion were female, equating to 24.9%. However, this does not paint the full picture, as there was a considerable difference in the ratio of subscribers between individual collections. It perhaps comes as no surprise, given that it was published in Edinburgh, that Natale Corri's A Set of Six Italian Songs (1791) attracted a high proportion of female subscribers, in this case 87.4%.Footnote 119 For the London-published collection of songs by Ann Hodges, 56.8% of subscribers were female.Footnote 120 The music in this volume was harmonized by Nicolas-Joseph Hüllmandel and published by him for ‘the Benefit of Her Orphan Children’; it no doubt attracted a significant number of subscribers, including Queen Charlotte, the wife of George III, who wished to contribute to and be publicly associated with a charitable cause. In contrast to these, Broderick's Medley, which despite its title is a book of words, attracted no female subscribers.Footnote 121 Its target audience was the Freemasons, which could account for the lack of women, although some collections of music intended for use in masonic circles, such as Thomas Hale's Social Harmony (1763) and William Riley's Fraternal Melody (1773), did appeal to a few members of this gender (respectively 2.6% and 1.1%).Footnote 122

Another popular form of vocal music in the second half of the eighteenth century was the glee. This type of music is largely associated with club activity, where it would have been performed by men and, as expected, the majority of subscribers to such works were indeed male. Nevertheless, there were a significant number of female subscribers, accounting for 22.1% of the total.Footnote 123 Although women would not, as a rule, have performed such works in public, they are known to have done so in private.Footnote 124 For example, Mary Noel (1776–1802), in a letter from 1784, wrote: ‘We have spent the week pleasantly − in good truth we are as merry as so many Beggars in a Barn. Diana rides with me, we eat, drink & sing Catches & Glees.’Footnote 125 John Marsh (1752–1828) also reported on how he had accompanied the performance of a glee in 1794, sung by, among others, ‘Mrs S. Heming’.Footnote 126 The music books assembled in the early nineteenth century by Elizabeth Egerton, and Lydia Acland of Killerton House, Devon, contain large numbers of glees, catches and canons, including songs normally associated with more masculine topics, such as naval battles,Footnote 127 as does a volume of music that once belonged to Harriet Capell (c.1735–1821), the Countess of Essex. It contains, amongst other works, glees by John Percy (Figure 16) and Richard Stevens, and a catch by the Earl of Mornington.Footnote 128

Figure 16. Copy of a Glee by John Percy that belonged to Harriet Capell, the Countess of Essex.

Note: GB-DRu: Fleming b.38(a).

Glees were even composed by female musicians, including Maria Hester Park (1760–1813) whose op. 3 A Set of Glees (c.1790) was dedicated to Mary Bertie (c.1730–93), the Duchess of Ancaster.Footnote 129 Surprisingly, she had more female subscribers than male. Of the 131 subscribers, 57.3% were female and, of these female subscribers, 36% had aristocratic titles, 28% were titled ‘Mrs’, and 36% ‘Miss’. Although some of these subscribers would no doubt have subscribed for reasons not to do with the music, these figures would indicate that the performance of glees by female amateurs took place on all levels of society and whether a woman was married or not did not necessarily have an impact. Even for Park herself, being married did not mean that she had to leave music behind. Her 1785 op. 1 set of Sonatas for the Harpsichord were published under her maiden name of Reynolds, and she continued to issue music in the early nineteenth century, including A Divertimento for the Piano Forte, in around 1801 (Figure 17).Footnote 130

Figure 17. Titles of Female Subscribers to Maria Hester Park's A Set of Glees, op. 3 (c.1790).

Music for flute

The flute, as has already been observed, was viewed as a particularly unsuitable instrument for a woman, although, like the violin, ladies are known to have played this instrument in private. Ford, for instance, reported on Susanna Montgomerie (1690–1780), Lady Rachel Binning (1696–1773) and Lady Catherine Gairlies (d.1786), all of whom played the flute or recorder.Footnote 131 In December 1735 Alexander Baillie published his Airs for the Flute with a Thorough Bass for the Harpsichord, which he dedicated to Lady Gairlies. The dedication to this work indicates that she had studied the recorder for some time:

The following Airs have been composed by a Gentleman for your Ladyship's Use when you began to practice the Flute a Beque [Bec]; I thought I could not chuse a better Subject for my First Essay as an Engraver of Musick than these Airs; as well because they were made for Beginners on the Flute & Harpsichord, as that they were composed by a Gentleman who first put a Pencil in my Hand and then an Engraver. But chiefly because they were originally made for your Ladyship's Use which gives me so fair a Handle to send them into the World under the Protection of your Ladyship's Name.Footnote 132

Other closet flautists include Marianne Davies (c.1744–c.1818), the daughter of an Irish musician, and Anne Lister (1791–1814) of Shibden Hall, today best known for her intimate relationships with other women.Footnote 133 Although only 11.2% of subscribers to music advertised for the flute were women, their subscription indicates that some might have played this instrument in private. The issue, however, in assuming this is that such works were laid out on two staves, with the solo instrument on the treble stave and the keyboard part, with a figured bass, on the lower stave. As such, it is possible to play these works as keyboard solos. However, if the public generally viewed these as playable as keyboard solos, the question arises as to why the proportion of female subscribers is so much lower than what was seen with the set of keyboard lessons and sonatas. In terms of individual collections, Alexander Munro's A Collection Of the Best Scots Tunes Fited to the German Flute (1732), perhaps understandably, had no female subscribers, while Alessandro Besozzi's (1702–93) Six Solos for the German-Flute, Hautboy or Violin (1759) had 15 (6% of subscribers).Footnote 134 These subscribers come from different social strata and include aristocracy, married and unmarried women. Sadly, it has been impossible to ascertain if any of these subscribers played one of these instruments.

Other permutations of the data

Of all the lists examined, 20 (3.6%) were attached to works by female composers or authors, indicating just how much music publication in the eighteenth century was male dominated. Unsurprisingly, this music includes genres that were more popular with female performers, such as keyboard lessons, sonatas and concertos, along with songs and music for harp. There is also the 1809 set of Twelve Voluntaries by Theophania Cecil that attracted a higher proportion of female subscribers (45.5%) than was typically associated with this genre (27.3%).Footnote 135

Given what we have already observed in relation to books on music theory and the collections of Cathedral Music by Boyce and Arnold, one would anticipate that Charles Burney's (1726–1814) A General History of Music (1776) would receive a low proportion of female subscribers. This turns out be the situation: only 15.1% of subscribers were of this gender.Footnote 136 However, the autobiography of a practising musician and Polish immigrant, Joseph Boruwlaski (1739–1837), attracted more female subscribers, with the average proportion of female subscribers over the three editions of his memoirs being 29.5%. This is far higher than the 8.5% that Charles Dibdin attracted for his 1788 Musical Tour. Clearly the personal accounts of a musician were also, as a rule, more popular with male subscribers.

Conclusion

The material contained in subscription lists issued over the long eighteenth century has, before now, not been analysed in any great depth; nevertheless, the importance of this data and what it can reveal is more than evident from this study. This research has given an important insight into what types of music were popular with the music-buying public, and the changes in society that took place over the course of that century. It is obvious that the publication of music was a male-dominated activity, and it was members of this gender that primarily subscribed to the latest publications. However, a closer perusal of the data reveals that there were clear changes in the patterns of subscription over the course of the century, with an increasing proportion of female subscribers. There are, furthermore, distinct differences in the patterns of subscription, depending on in which country or city the music was issued. This not only reflects the way in which music was viewed by the population in these areas, but also the teaching practices and wider networking of the composers involved.

Women tended to have a preference for secular music rather than sacred, with the most popular genres for them being composed for the keyboard, a class of instrument that society thought particularly suitable for a lady. However, women also subscribed to works intended for inappropriate instruments, such as the violin, flute or cello, or for works primarily intended for public performance. Many of these subscriptions may have been taken out in support of the composer, for the benefit of a male family member, or for outward show, but it is intriguing that some of these women may have been involved with the performance of such works in private. Vocal music was performable by members of both genders, and even the music chiefly associated with male-only music clubs, such as glees, was performed by women. There was also little distinction between the classes; glees were equally performable by members of the aristocracy, gentry and middling classes.

There is, in addition, the realization that individual composers could have been more popular with a particular gender. Handel, for instance, was more popular with male subscribers, while there are indications that Pleyel's keyboard music may have been more popular with women. In addition, men had a stronger interest in old music, and it was they who sought to advance their musical understanding through the purchase of a primer. Dancing tutors, given the association of this activity with important social events, attracted an appreciable number of subscribers from both genders, although such works enticed a higher proportion of female subscribers later in the century; this again reflects broader changes in society.

The effort required to analyse a significant number of subscription lists has certainly been considerable, but the importance of these documents in our understanding of British society and the changes that took place during the Georgian period cannot be understated. They are a hugely valuable resource which, when linked with other types of documents such as diaries and advertisements, provides us with a far greater insight into the patterns of musical activity in eighteenth-century Britain than has ever been seen before.

ORCID

Simon D. I. Fleming http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7043-6908

Acknowledgments

I am grateful for the assistance of staff at the British Library, the Foundling Museum, the National Library of Scotland, the Royal Academy of Music, the Henry Watson Music Library, Manchester, the university libraries of Durham, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Leeds, Nottingham and Oxford, and the Dean and Chapter Library at Durham Cathedral. Thanks are also due to Travis and Emery, and Otto Haas, antiquarian music specialists. Individual thanks are due to Amélie Addison, Kim Baston, Michael Cole, Colin Coleman, Gordon Dixon, David Griffiths, Simon Heighes, Elias Mazzucco, Martin Perkins, Andrew Pink, Timothy Rishton and Michael Talbot, most of whom provided me with copies of lists used in this study. I also wish to extend my additional gratitude to Michael Talbot, who provided me with feedback on an early version of this article. Online resources used to source lists include the British Library website, Google Books, Eighteenth Century Collections Online, the Internet Archive, the National Library of Scotland website, the Hathi Trust and IMSLP.

Appendices

Appendix A. The percentage of subscribers (male/female/other-institutional) to each category and list discussed in this study, given to one decimal place.

| Category | Men% | Women% | Institutional/Other% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subscribers to all works | 75.3 | 23.1 | 1.7 |

| Subscribers before 1700 | 98.3 | 1.7 | 0 |

| Subscribers 1701-1720 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Subscribers 1721-1740 | 82.1 | 16.9 | 1 |

| Subscribers 1741-1760 | 80.2 | 17.9 | 2 |

| Subscribers 1761-1780 | 77.5 | 20.2 | 2.2 |

| Subscribers 1781-1800 | 73.3 | 25 | 1.7 |

| Subscribers 1801-1820 | 70.4 | 28.4 | 1.2 |

| Subscribers to works issued in Birmingham | 79.1 | 20.1 | 0.7 |

| Subscribers to James Lyndon's Six Solo's (1751) | 60 | 40 | 0 |

| Subscribers to Sacred Works | 80.7 | 15.7 | 3.6 |

| Subscribers to Secular Works | 73.3 | 25.7 | 1 |

| Subscribers to works by Handel | 80.4 | 17 | 2.5 |

| Subscribers to Handel's Works Issued in the Composer's Lifetime | 81.4 | 16 | 2.5 |

| Subscribers to Handel's Works Issued Posthumously | 80.3 | 17.2 | 2.5 |

| Subscribers to Samuel Arnold's Edition of Handel's Works | 76.2 | 22 | 1.7 |

| Subscribers to Works Issued in England | 74.8 | 23.3 | 1.9 |

| Subscribers to Works Issued in Scotland | 77.5 | 22.2 | 0.3 |

| Subscribers to Works Issued in Ireland | 77.5 | 22.2 | 0.3 |

| Subscribers to Works Issued in America | 92.4 | 6.4 | 1.3 |

| Subscribers to Works Issued in India | 84.6 | 15.4 | 0 |

| Subscribers to Works Issued in London | 74.3 | 23.7 | 2 |

| Subscribers to Works Issued in Edinburgh | 63.3 | 36.1 | 0.6 |

| Subscribers to John Watlen's Two Books of Circus Tunes (1791 & 1798) | 23.1 | 76.9 | 0 |

| Subscribers to Natale Corri's Three Sonatas, Op 1 (c.1790) | 9 | 91 | 0 |

| Subscribers to Works by John Valentine | 93.4 | 1.9 | 4.7 |

| Subscribers to John Valentine'sThe Epithalamium in the Tragedy of Isabella (c.1765) | 94.7 | 4.7 | 0.6 |

| Subscribers to String Concertos | 79.1 | 16 | 4.8 |

| Subscribers to George Jackson's A Treatise on Practical Thorough Bass….Op. 5 (1791) | 74.8 | 25.2 | 0 |

| Subscribers to Charles Avison's Concertos | 80 | 15.9 | 4.1 |

| Subscribers to Charles Avison's Six Concertos, Op 2 (1740) | 87.1 | 8.2 | 4.7 |

| Subscribers to Charles Avison's Eight Concertos, Op 4 (1755) | 75.8 | 19.2 | 5 |

| Subscribers to Charles Avison's Twelve Concertos, Op 9, Book 2 (1767) | 76.7 | 19 | 4.3 |

| Subscribers to Keyboard Concertos | 63.5 | 34.9 | 1.6 |

| Subscribers to Charles Avison's Two Concertos (1742) | 82.6 | 11.8 | 5.6 |

| Subscribers to Thomas Chilcot's Keyboard Concertos (1756 & 1765) | 67.6 | 30.1 | 2.3 |

| Subscribers to Trio Sonatas | 86.4 | 11.6 | 2 |

| Subscribers to Accompanied Keyboard Sonatas | 53 | 46.7 | 0.3 |

| Subscribers to Sonatas for Solo Keyboard | 50.6 | 49.4 | 0 |

| Subscribers to Lessons for Solo Keyboard | 56.7 | 43.2 | 0.1 |

| Subscribers to Samuel Wise's Six Lessons for the Harpsichord (c.1765) | 40 | 60 | 0 |

| Subscribers to John Elouis’ Arrangement of Three Celebrated Trios by Ignace Pleyel (1800) | 8.8 | 91.2 | 0 |

| Subscribers to Marie Marin's Notturno & Quintetto, for the Harp….Op. 14 (1801) | 27.5 | 72.5 | 0 |

| Subscribers to Organ Voluntaries | 72.5 | 27.3 | 0.2 |

| Subscribers to Music Tutors | 83.6 | 16.2 | 0.2 |

| Subscribers to John Gunn's The Theory and Practice of Fingering the Violoncello (c.1790) | 98.8 | 0 | 1.2 |

| Subscribers to Giacob Cervetto's Twelve Solos for a Violoncello (1748) | 78.5 | 21.5 | 0 |

| Subscribers to Music Advertised for the Cello | 90 | 10 | 0.1 |

| Subscribers to Dance Tutors | 57 | 43 | 0 |

| Subscribers to E. Pemberton's An Essay for the Further Improvement of Dancing (1711) | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Subscribers to Kellom Tomlinson's The Art of Dancing (1735) | 66.3 | 33.7 | 0 |