Developed societies are characterised by open political and economic markets with general incorporation acts and competition between organisations (North et al. Reference North, Wallis and Weingast2009). One of the key elements sustaining open access orders is the existence of impersonal rules that treat everyone the same. From a historical perspective, however, the competition and establishment of impersonal rules are an exception rather than the rule. Impersonal rules have only been sustained by a handful of countries starting around 200 years ago (North et al. Reference North, Wallis and Weingast2009; Wallis Reference Wallis2011). For most of human history, social orders relied on coalitions of elites that created a dominant coalition maintained by the economic rents derived from privileged access to resources and the formation of organisations (what North et al. Reference North, Wallis and Weingast2009, call «natural states»).

Before North et al. proposed their theory of institutional development, Max Weber had emphasised the importance of impersonal rules and their coevolution with the organisation of the personnel of the state during the transition to modern societies. The German sociologist distinguished between patrimonial regimes—in which the nature of the office holders is fundamentally personal—and modern bureaucracies—where office-holding is structured by impersonal and functional purposes (Weber Reference Weber1978, p. 959). Thus, with respect to the personnel of the state, institutional development requires the transition from bureaucracies dominated by personal links across the hierarchy to a model characterised by impersonal rules, bureaucrats' professionalism, and meritocracy. In its ideal type, Weberian bureaucracies are rational–legal organisations that are «formalized, hierarchical, specialized with a clear functional division of labor and demarcation of jurisdiction, standardized, rule-based, and impersonal. Staff is appointed to office and rewarded on the basis of formal education, merit, and tenure» (Olsen Reference Olsen2006, p. 2).

In this study, La Parra-Perez's micro-data set of officers (Reference La Parra-Perez2019) has been used to study one of the most important bureaucratic structures in early 20th-century Spain (the army) in the context of a non-consolidated democracy (the Second Spanish Republic, 1931–1939). The data set comprises data from military yearbooks published by the Spanish Ministry of War in order to trace the professional trajectory of more than 10,000 officers who were active in the period 1931–1936. The results for the empirical analysis of officers' promotions under different ruling coalitions suggest that conservative factions within the army were favoured during the ruling of conservative governments (1934–35) and were harmed by some of the military policies (in particular the revision of promotions passed in the 1920s) introduced by the centre-left governments during the period 1931–33. To test the robustness of the results, I also use a new data set comprising all the colonels and generals active between 1932 and 1936. Rather than a modern Weberian bureaucracy, the army during the Second Republic was still subject to the politicised appointments that characterise patrimonial regimes and natural states.

The Second Republic represented an ambitious attempt to reform and modernise Spanish institutions. As part of the reformist efforts, Manuel Azaña, Minister of War between 1931 and 1933, implemented a series of military reforms that increased impersonality in officers' promotion but left the door open to discretionary powers to appoint personnel to the top ranks. The military is a relevant case study to explore the politicisation of the Spanish bureaucracy for at least three reasons. First, the army exemplifies the merits and limits of the centre-left reformist agenda in the early years of the Republic. Azaña's government took important steps to create a more impersonal system, but key elements of natural states persisted. Second, the Spanish Civil War (henceforth, SCW), which ended the Republic and led to Franco's dictatorship (1939–1975), began with a military coup that showed the animosity of some military factions against Azaña's Popular Front government in 1936. Politicisation in military appointments can shed some light on some of the officers' sources of animosity towards the government in 1936. Finally, the military was not under consolidated civilian control, a feature that Spain shared with many developing countries in the 1930s (Kamrava Reference Kamrava2000; Golts and Putnam Reference Golts and Putnam2004; North et al. Reference North, Wallis and Weingast2009, pp. 169–180), particularly in interwar Europe (Agøy Reference Agøy1996). The internal dynamics of the army is a relevant variable in its own right when analysing political change and the challenges faced by non-consolidated democracies such as the Second Republic (Agüero Reference Agüero, Gunther, Diamandouros and Puhle1995). In North et al.'s words:

«If active support of the military forces is necessary to hold or obtain control of the civilian government institutions, then a society does not have political control of the military. If military officers serve as officers (…) in the civilian government, for example as legislators or executives, then a society does not have political control of the military» (North et al. Reference North, Wallis and Weingast2009, p. 170).

The Republic inherited and operated an institutional arrangement lacking consolidated control of the military. It is not surprising then that some of the most important political figures of the Second Republic (such as Manuel Azaña and José María Gil Robles) occupied the post of Minister of War at different points between 1931 and 1936. Relationships between the government and the army were very important in the Spain of the 1930s and military policies «from above» interacted with the military's tendency to intervene «from below»Footnote 1.

Studying politicisation in military promotions is challenging due to officers' unobservable ideology. Few officers unequivocally signalled their beliefs and political affinities through affiliation to a political party or written political statementsFootnote 2. This article focuses on the members of the Africanist faction (officers who fought in wars against Berber tribes between 1910 and 1927) for two reasons. First, Africanist officers formed one of the most conservative groups within the army (Payne Reference Payne1967, p. 327; Graham Reference Graham2005, p. 9; Preston Reference Preston2012, p. 34). In other words, membership of the Africanist faction is a good proxy for officers' (conservative) ideology. Second, membership of the Africanist faction can be observed using the military yearbooks to identify the officers posted to the units that formed the core of the faction.

The results provide evidence of the politics driving military promotions and reforms. Africanists' careers slowed down under the rule of centre-left governments (1931–33) but significantly improved during the next two years under conservative rule (1934–36). The mechanisms used by each administration to affect Africanists' careers differed. Whereas conservative governments were more likely to choose Africanists for promotion to the top ranks in the army, the results do not unequivocally suggest that centre-left governments had a different propensity to promote Africanist and non-Africanist officers. It seems clear, however, that the revision of promotions performed by Azaña in 1933 targeted Africanists by slowing their careers and making them ineligible for promotion the next year.

Neoclassical theories of the state typically rely on single rulers or a homogenous bloc of elites (e.g. North Reference North1981; Levi Reference Levi1989; Tilly Reference Tilly1992; Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2006). The results in this article, however, are in line with the idea that intra-elite competition and conflict of interest play a key role in the dynamics of natural states and their patrimonial bureaucracies (North et al. Reference North, Wallis and Weingast2009, pp. 36, 148–149, 157). The vicissitudes of Africanist officers during the Second Republic are one example of the realignments of the Spanish dominant coalitions during the 1930s. Details on the military factionalism and institutional reforms are contingent to the Spanish case, but the need to study elite factionalism is generalisable to the agendas of empirical research on political and economic development.

There are many reasons why uncovering the evidence of the politicisation of the Spanish bureaucracy during the Republic is an important element to understand the challenges that the republican regime faced. Meritocratic, non-politicised bureaucracies with separate careers for politicians and bureaucrats have been found to lead to lower levels of corruption and more effective governments (Dahlström et al. Reference Dahlström, Lapuente and Teorell2012; Dahlström and Lapuente Reference Dahlström and Lapuente2017). More importantly for the Second Republic, Lapuente and Rothstein pointed out that «the (lack of) separation of politics and administration is a variable that, interacted with a given social divide, multiplies its effects by providing incentives for radicalization to a large number of state officials and would-be officials» (Reference Lapuente and Rothstein2014, p. 1425). Exploring the mechanisms that politicised the functioning of the Spanish military bureaucracy and the changing nature of alliances between the government and military factions adds to the many factors that fuelled tensions and ultimately contributed to the failure to consolidate a stable dominant coalition, the SCW, and the demise of Spain's first democracy.

The core ideas in this article are not new. First, the non-Weberian character of the Spanish (non-military) bureaucracy before and during the Second Republic has been documented before (Serrallonga i Urquidi Reference Serrallonga I Urquidi2007; Lapuente and Rothstein Reference Lapuente and Rothstein2014). In this sense, the Republic did not break with one key institutional feature of previous regimes. The Restoration (1873–1923) used clientelistic networks dominated by caciques—local rural elites—to manipulate elections. Changes in the governments also implied an almost complete restructuration of bureaucrats (there was even a term—cesante—to describe the public servant who would end his term after the party in government lost the elections). Second, the role of the army as an independent political player at the centre of the institutional dynamics during and before the Second Republic has also been extensively studied (see, e.g. Payne Reference Payne1967; Boyd Reference Boyd1980; Cardona Reference Cardona1983; La Parra-Perez Reference La Parra-Perez2016). This article provides, to the best of my knowledge, the first empirical case study at the intersection of the studies on the politicisation of the Spanish bureaucracy and the military. It also relates to the literature exploring the functioning of different organisations in the Spanish bureaucracy during the first third of the 20th century (Domenech Reference Domenech2015).

The rest of this article is organised as follows: Section 1 describes the political importance of the military in Spanish history and the military reforms implemented during the Second Republic; Section 2 presents the data used for the empirical analysis presented in Section 3; Section 4 concludes.

1. ARMY FACTIONALISM IN SPANISH HISTORY AND MILITARY REFORMS DURING THE SECOND REPUBLIC

Military intervention in politics was constant in Spanish history. During the 19th century, nine pronunciamientos (military coups) overthrew or successfully lobbied to reshuffle governments. More than thirty additional pronunciamientos were also attempted during the same period, but all failed (Barciela López et al. Reference Barciela López, Tafunell and Carreras2005, pp. 1,085–1,086). The regime established in Spain between 1873 and 1923—known as the Restoration—was characterised by its «praetorian politics» and the far-reaching powers that the Constitution gave to the army (Boyd Reference Boyd1980). The Restoration was followed by General Primo de Rivera's dictatorship (1923/30) after the officer came to power via a pronunciamiento with the King's acquiescence. Contrary to the precedent regimes, the Second Spanish Republic (1931–39) did not come into existence via a military coup. After the republican parties won the municipal elections in February 1931 in the biggest Spanish cities, the King fled the country and the Republic was established. The republican regime, however, did not escape the long shadow of military influence in Spanish politics; after a failed military coup in 1932, another coup in 1936 led to the SCW (1936–39) and General Francisco Franco's dictatorship (1939–75).

Military intervention in politics has often shown that the Spanish army was not a monolithic organisation (La Parra-Perez Reference La Parra-Perez2016). One of the most important divisions in the Spanish military in the early 20th century was the geographical divide between officers posted in the Spanish colonies in Northern Africa (Africanists) and officers posted in the Iberian Peninsula (Peninsulares). The main contention between these factions revolved around methods of promotion. Africanists were proponents of combat merits as a path towards promotion, whereas Peninsulares preferred a closed method of promotion exclusively based on seniority. It is not difficult to see how self-interest motivated the position of each faction; Peninsulares were not exposed to the battlefield and feared that a method that considered combat merits for promotion would harm their career advancement. Conversely, Africanists were exposed to conflict with Berber tribes—especially between 1910 and 1927—and would gain from a system that rewarded combat actions when determining promotions.

The disputes between Africanists and Peninsulares transcended purely military considerations. When, in 1917, the government passed a law that allowed promotions by combat merit, Peninsulares lobbied through the so-called Juntas de Defensa and forced the fall of the government. The new government ceded to Peninsulares' lobbying and restored the pre-eminence of promotions by strict seniority (Cardona Reference Cardona1983, p. 145). However, the controversy between Africanists and Peninsulares did not end there. During Primo's dictatorship, promotions by combat merit and election (i.e. freely determined by the dictator) were reintroduced; therefore, the Second Republic inherited a military hierarchy in which combat merit had played a significant role in the rank of many active officers (especially Africanists). The revision of the methods of promotion would be one of the main military reforms undertaken by Manuel Azaña, Minister of War between 1931 and 1933.

In addition to their shared economic interests, the Africanists developed a strong esprit de corps, and most of them were profoundly conservative. Graham points out that «the experience of the North African campaigns forged a brand of warrior nationalism that only further hardened military attitudes» (Graham Reference Graham2005, p. 9). Africanists' conservatism was at odds with the reformist programme of the centre-left government that ruled the Second Republic between 1931 and 1933. As Preston explains, «Africanista officers and Civil Guards were the most violent exponents of right-wing hostility towards the Second Republic and its working-class supporters» (Preston Reference Preston2012, p. 34). Talking about Millán Astray, a prominent Africanist who founded the Tercio de Extranjeros, Preston states that «the step from Africanista to fascista was a short one» (Preston Reference Preston2000, p. 34). It is then not surprising that Africanist officers were among the strongest backers of the military coup in 1936 (Payne Reference Payne1967, p. 327). The three successive leaders of the coup (Generals Mola, Sanjurjo and Franco) were prominent Africanists with stunning careers in large part due to their actions on African battlefieldsFootnote 3.

There are many possible explanations for Africanists' greater propensity to sustain harder militarist or conservative positions. First, self-selection surely played a role in the case of those officers who volunteered to serve in the Spanish African colonies between 1910 and 1927. The Spanish colonial adventures and military operations in Africa were very unpopular among leftist organisationsFootnote 4. It is possible, then, that those officers with leftist ideas were less likely to volunteer to serve in Africa. Second, there could be an «Africanist treatment» whereby those officers who served longer in Africa and those who were posted there without volunteering were more exposed, and internalised the conservative mentality and esprit de corps that characterised officers in the colonies more stronglyFootnote 5. In an interview in 1938, for example, Franco declared that «[m]y years in Africa live within me with indescribable force. There was founded the idea which today redeem us. Without Africa, I can scarcely explain myself to myself, nor can I explain myself properly to my comrades in arms» (Preston Reference Preston2000, p. 50).Footnote 6 Whatever the mechanism linking Africanism to officers' animosity towards the leftist Popular Front government in 1936, note that both channels above suggest that more years in Africa should correlate with greater conservatism (either because a longer stay in Africa signalled a greater commitment with the colonial cause or because it implied greater exposure to the «Africanist treatment»).

After the declaration of the Republic in April 1931, a centre-left government ruled until December 1933. The new government immediately started to draft a new Constitution and put an ambitious reformist programme in place: female suffrage was recognised for the first time in Spanish history, a land reform that redistributed land was approved in 1932 (but faced serious limitations and delays in its implementation), and the Constitution established the separation between the Church and the State. The conflict with the Catholic Church was exacerbated by the suppression of the Society of Jesus in 1932 and the end of the pre-eminence that the Catholic Church had enjoyed in the Spanish schooling system before the Republic.

The army did not escape the reformist wave. Manuel Azaña was in charge of reforming the Spanish Army. Azaña was the leader of the centre-left Acción Republicana and is considered as one of the most emblematic symbols of the Republic. At the start of the SCW, he was the President of the Republic and the leader of the Popular Front, the leftist coalition that had won the elections held in February 1936.

One of Azaña's main goals as the Minister of War was limiting the traditional influence that the army had in Spanish politics (Cardona Reference Cardona1983, pp. 117, 127; Preston Reference Preston2000, p. 199). Azaña knew the danger of military conspiracies against his government, but he was confident that his legislative reforms based on the «national will» would suffice to change the country (Cardona Reference Cardona1983, pp. 126, 129–131; Navajas Zubeldia Reference Navajas Zubeldia2011, p. 92; Juliá Reference Juliá2015, pp. 51, 282).

The military reforms that focused on officers' promotion fell into two categories: the establishment of a new system of promotions and the revision of some pre-republican policies which were deemed arbitrary. In the preamble to one decree, Azaña stated his intention to suppress favouritism in military appointments. He wrote: «[The commanding powers given to the Minister of War] have been used too often to establishing favoritism, promoting clientelism, hindering merit, and sowing unhappiness among [officers’] spirits»Footnote 7. Azaña was confident that the problem of favouritism could be solved through «hard work and disinterest». These goals were, at least in theory, consistent with the impersonal rules that must characterise a modern bureaucracy.

Before establishing the new methods of promotion in the republican army, Azaña revised the promotions that had taken place before 1931. Two types of promotions were under scrutiny. First, the promotions approved during Primo's dictatorship that contradicted the legislation passed before 1923 by the pseudo-democratic Parliament of the Restoration were revised and cancelled. Second, Primo's promotions deemed arbitrary (e.g. those by election) were revised and cancelled if they could not be maintained on purely seniority grounds at the time of the revision. The results of the revision were published in 1933, which resulted in a lower position for many officersFootnote 8. Franco, for example, went from being the first brigadier general in the 1933 yearbook to the fifteenth position in 1934.

In a law published on 12 September 1932, Azaña established the method of promotion for military officers. Seniority was the main channel to advance positions and ranks, thus rendering the promotion of officers more impersonal than in previous regimes and closer to a rational–legal Weberian military bureaucracy. Captains and colonels also had to pass a training course for promotion (Cursos de Preparación para el Ascenso) in order to be eligible for promotion to the position of major and brigadier general, respectively (see Table 1 for ranks and hierarchy in the Spanish Army). Officers' position on the scale would be changed depending on the grade obtained in the training courseFootnote 9. In 1923, Azaña had written that «intellectual test should be the first, if not the only one, criteria in the selection of a commander» (Azaña Reference Azaña1966, p. 507)Footnote 10. Reinforcing the importance of study and merit in promotion was another step towards a Weberian military bureaucracy.

TABLE 1 RANKS IN THE SPANISH ARMY

Despite the steps towards greater impersonality and meritocracy in officers' promotions, Azaña's reforms did not completely end with discretionary appointments in the army. In particular, the Minister could freely appoint the officers who would be promoted from colonel to brigadier general and from captain to major among those who had successfully passed the training course and were in the top third of their rank scale. Promotions from brigadier to division general were also at the Minister's discretionFootnote 11. Thus, both meritocracy (through study and the score obtained in the training course) and the Minister's election determined the promotion to the highest ranks of the army.

The tension between impersonal rules and discretionary appointments is a controversial question in military circles that has also existed in other countries. Speaking of the US Army in the 1920s, Huntington points out that «[t]he basic issue confronting the Army was still the old controversy of seniority versus selection» (Huntington Reference Huntington2008, p. 297). However, in contrast with the United States, Spain was a country lacking a consolidated control of the military and with a long history of politicisation of its bureaucracy that still continued in the 1930s (Lapuente and Rothstein Reference Lapuente and Rothstein2014). The government's discretionary powers for military promotions had different implications in the United States and in Spain.

Azaña's contemporary political rivals and some modern historians have suggested that despite his declared intentions, Azaña was actually guided by favouritism and political criteria when using his discretionary powers to promote officers (Ruiz Vidondo Reference Ruiz Vidondo2004, p. 102). Emilio Mola criticised Azaña's system of promotions arguing that it led to favouritism and intrigue (Mola Reference Mola1934, pp. 187–199). Stanley Payne described Azaña as «the last in a long line of nineteenth-century sectarian bourgeois politicians» (Payne Reference Payne2006, p. 356). Azaña's enemies coined the term «black cabinet» referring to the group that advised the Minister on military affairs and promotions (Alpert Reference Alpert2008, pp. 165–166; Navajas Zubeldia Reference Navajas Zubeldia2011, pp. 101–104).

Azaña's motivations for revising promotions implemented before the Republic were particularly controversial. Some argued that rather than political considerations, Azaña was motivated by the lack of legitimacy of Primo's dictatorship. The Ley de Bases of 1918 was the last regulation of promotions passed by the (pseudo) democratic parliament during the Restoration, which Azaña considered a more legitimate legislative source than Primo's regime (Alpert Reference Alpert2008, p. 130; Navajas Zubeldia Reference Navajas Zubeldia2011, p. 95). In the preamble of the decree that ordered the revision of Primo's promotions by election, Azaña declared:

«[Primo's decree allowing promotions by elections], besides being contrary to the Law, has produced within the Army undeniable troubling and concern that must be urgently remedied in two ways: first, reestablishing the system voted by the legislative Power, and second, rectifying the effects of the aforementioned decree in those instances in which it has altered the effects of seniority.» (p. 800)Footnote 12

Legitimacy considerations aside, Azaña was also aware of the harm that the revision of promotions would inflict on Africanists' careers. On 8 February 1933, he wrote

«[General Vera] told me that general Franco is very angry at the revisions of promotions. He passed from being the first brigadier general to the twenty fourth place. It is the least that could have happened to him. I thought that he would descend even more.» (Azaña Reference Azaña2011)Footnote 13

Salas Larrazábal, a historian and a military officer who fought in Franco's army during the SCW, probably had the revision of promotions in mind when he accused Azaña of harming officers who had advanced quickly in the regimes predating the Republic (Salas Larrazábal Reference Salas Larrazábal, Hernández Sánchez-Barba and Alonso Baquer1987).

Azaña had reasons to distrust Africanists. In August 1932, General Sanjurjo, an Africanist, led a failed military coup against the Republic to establish a dictatorship. The coup was in part a response to Azaña's military reforms and Sanjurjo's transfer to what he considered a less important post (Casanova Reference Casanova2014, p. 88). The coup was easily suppressed by the republican security forces, but it could have reinforced Azaña's determination to use his powers as Minister of War to ostracise those members of the Africanist faction who openly opposed him and his political coalition. The impact that the revision of promotions had on Africanists' careers (see empirical analysis below) is in line with this idea.

In the elections held in December 1933, the ruling centre-left coalition lost its majority in the parliament, and a centre-right coalition ruled between January 1934 and December 1935. Despite the fact that Azaña's methods of promotion remained in place, there is anecdotal evidence indicating changes in the selection of top military officers that took place under the different conservative coalitions that were in power. Cardona sees Diego Hidalgo's tenure as head of the Ministry of War (January to November 1934) as an attempt to detract from Azaña's reforms and benefit some of the former minister's enemies (Cardona Reference Cardona1983, p. 198). José María Gil Robles, the main figure of the leading conservative party who became Minister of War between May and December 1935, described his term as follows: «I relieved many officers of their post, I deprived of command many officers that did not deserve such responsibility and, consequently, I purged the Army of clearly undesirable elements» (Gil Robles and Beltrán de Heredia Reference Gil Robles and Beltrán De Heredia1968, p. 238). The «clearly undesirable elements» probably referred to Azaña's loyal officersFootnote 14.

Africanists were at the centre of the coalition realignments under different administrations. When Azaña was the Minister of War, only two Africanists were promoted to the rank of brigadier general in 1932–33 (Eliseo Álvarez Arenas-Moreno in 1932 and Alejandro Rodríguez González in 1933)Footnote 15. In 1934 and 1935, by contrast, three and four Africanists, respectively, were promoted to brigadier or division general or reintegrated into active service. Two distinguished Africanists and the leaders of the 1936 coup benefited from Hildago's policies in 1934: Francisco Franco was promoted to the rank of division general, and Emilio Mola was reintegrated into active service as brigadier general.

In summary, the Minister of War's discretionary powers fuelled suspicions about top-rank officers' appointments despite Azaña's declared goals to end favouritism. The revision of promotions also affected the careers of many officers. Did Azaña's revisions especially target military factions (such as Africanists) perceived as more hostile to progressive governments? Did Azaña also implement an active discrimination against Africanists when appointing top officers, as his critics suggest? Is there evidence of conservative governments during 1934–35 significantly reversing the policies of the previous years in favour of ideologically akin military factions?

The interaction between politics and military promotions has long been discussed in historical studies with generally positive answers to the previous questions. The hypothesis, however, has not been put to the (econometric) test. The next section presents the data used to assess empirically whether different governments resulted in different chances of promotion for Africanists and the extent to which the revision of promotions affected their careers. The results generally agree with historians' conclusions but also suggest some nuances.

2. DATA DESCRIPTION

The empirical analysis first uses La Parra-Perez's data set (Reference La Parra-Perez2019) for active officers in 1936. The data set is also expanded to contain annual data for all active colonels and generals between 1931 and 1936.

La Parra-Perez's data set contains individual information for active officers in 1936 belonging to the corps more directly involved in combat (general staff, infantry, cavalry, engineers, artillery, aviation, transportation, civil guard, Tercio officers—officers deployed in Africa, and frontier guards). Information about officers' name, date of birth, tenure in the army (years since the officer entered the army), rank and corps come from the 1936 military yearbook. The data set also contains two key variables for the empirical analysis in this article: officers' years spent in special African units between 1910 and 1927 and officers' annual changes of position between 1931 and 1936.

In his study of the Africanist group, Mas Chao states that «the majority of the [Africanist] group was formed by officers who stayed many years in Morocco, Ifni or Sahara posted in La Legión [Spanish Foreign Legion], African regular Army, Marksmen, Nomads, Mehal-las, Police, Intervention Corps, and so on» (Mas Chao Reference Mas Chao1988, pp. 8–9). Balfour and La Porte similarly pointed out that «in the course of the intermittent wars with the tribes of northern Morocco between 1909 and 1927, a new military culture called Africanismo was forged among an elite of colonial officers» (Balfour and La Porte Reference Balfour and La Porte2000, p. 309). This elite excluded officers posted to Africa «who had not volunteered to fight in, but had been posted to Morocco, and for whom military intervention there had little ideological or political appeal» (Balfour and La Porte Reference Balfour and La Porte2000, p. 313). In the same line but more generally, Navajas affirms that «regular and Foreign Legion forces were the core of military Africanism» (Navajas Zubeldia Reference Navajas Zubeldia2011, p. 66). In all these definitions, a subset of officers posted to Africa between 1910 and 1927 form the Africanista faction. Following these definitions, military yearbooks between 1910 and 1927 are used to construct a variable called «Years Core Africa» that measures the number of years that officers spent posted to the special forces who were permanently posted to the Spanish Protectorate in Africa between 1910 and 1927 and were more directly engaged in military actions. These units were the Spanish Foreign Legion (Tercio de Extranjeros), the Native Regulars (Grupos de Fuerzas Regulares Indígenas), the Mehal·las, the Harkas, the Native Police (Policía Indígena) and African Military Intervention. In the rest of this article, the term «Africanist» will refer to those officers who spent at least one year in at least one of the previous special African units between 1910 and 1927.

In order to assess officers' careers and changes of position each year, officers' relative position (RP) is computed for each year. For any officer i, holding rank r, in corps c and in year t, RP i,c,r(t) is equal to i's position in the scale for rank r and corps c in t divided by the total number of officers in the scale. The officer at the bottom of the scale, for example, will have an RP equal to 1 and the officer at the median position will have an RP equal to 0.5. After computing officers' RPs, officers' yearly change of position (ΔCP i(t)) is calculated. For officers who keep the same rank in t − 1 and t, ΔCP i(t) is equal to RP i,c,r(t − 1)–RP i,c,r(t). By definition, the number will be between zero and one. The more the officer progressed within the scale, the closer ΔCP i(t) is to one. If the officer was promoted N ranks between t − 1 and t, ΔCP i(t) equals N + RP i,c,r(t − 1); where RP i,c,r(t − 1) measures the portion of his previous rank's scale that he advanced (this is typically a small number because promoted officers were at the top of the scale of the previous rank). If, however, the officer was demoted N ranks, ΔCP i(t) equals (RP i,c,r(t − 1)−1)−N, to account for the fall over his old rank's scale (RP i,c,r(t − 1)−1) and the number of ranks being demoted (N)Footnote 16. Because military yearbooks were published at the beginning of the year, ΔCP i(t) reflects changes that took place in t − 1 Footnote 17. The bottom line is that officers with a faster (slower) career progress in year t will have a larger (smaller) value for their ΔCP t. Alternatively, the data set also contains information for officers' changes of rank (number of ranks advanced or regressed) in a given year.

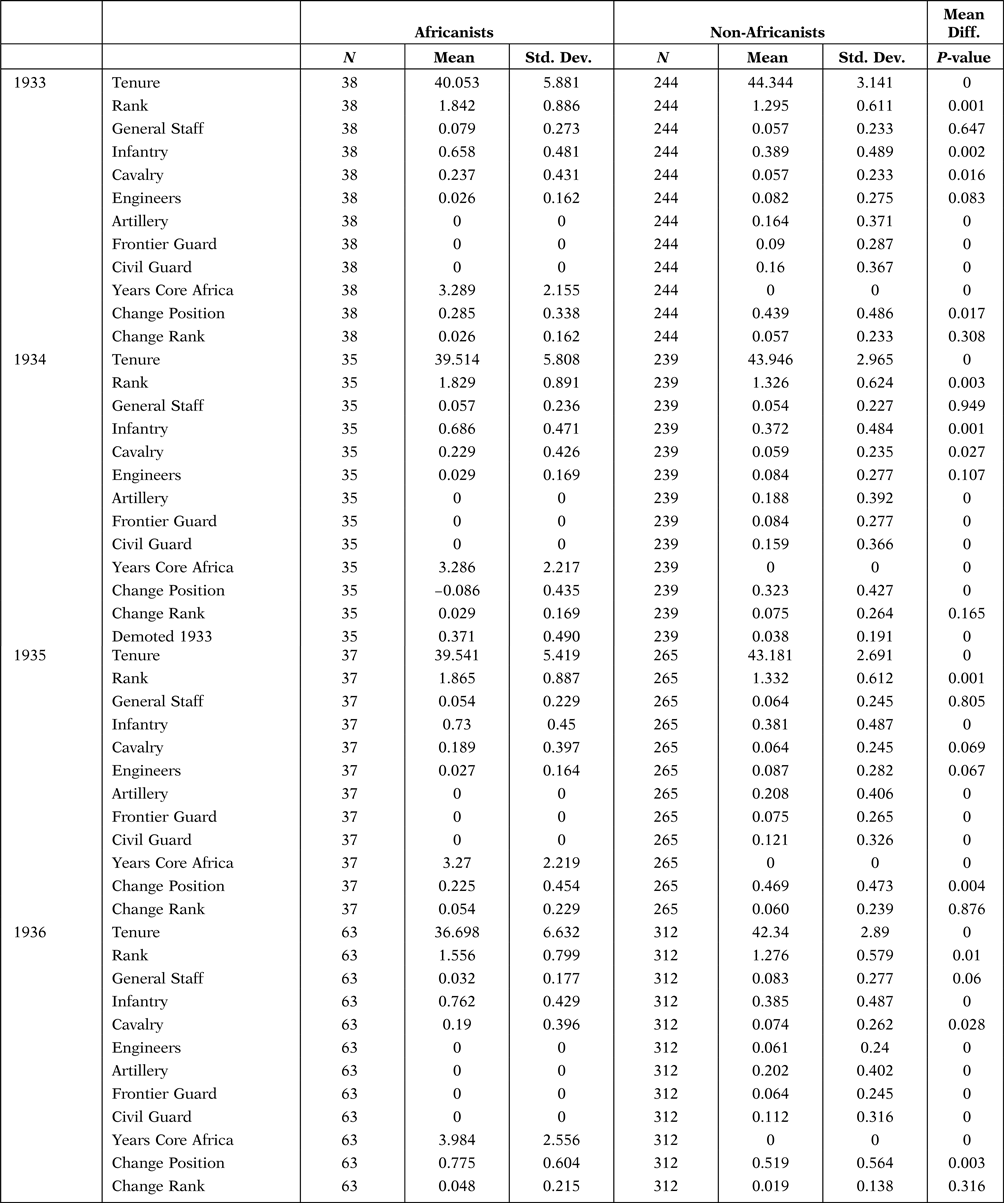

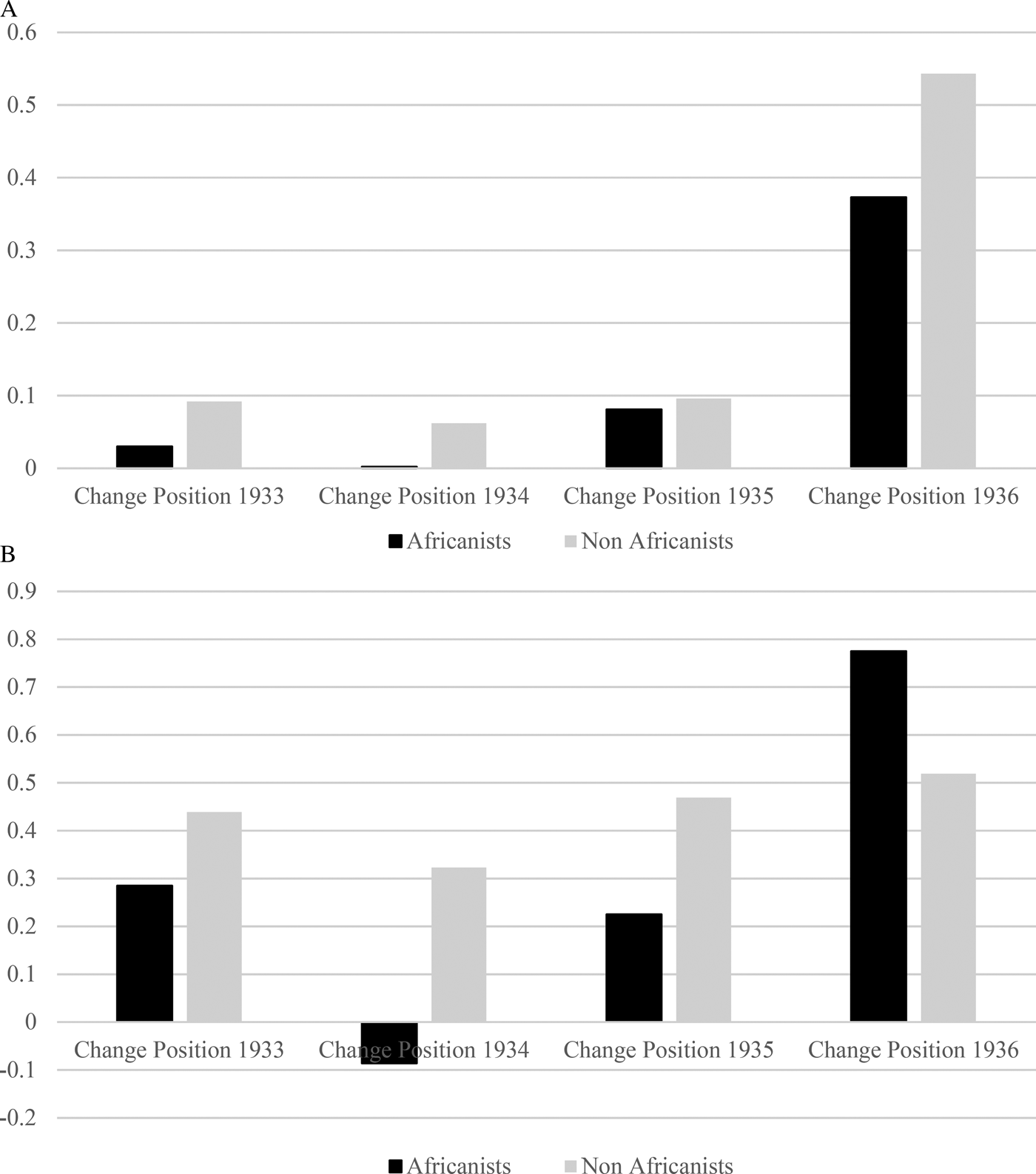

Table 2 shows the summary statistics for changes of RP, rank and other individual variables for active officers in 1936. Officers are divided into Africanists (those having spent at least one year in special African units) and non-Africanists. For reasons discussed in the next section, the empirical analysis also uses an alternative data set that contains the entire population of active colonels and generals for each year between 1932 and 1936Footnote 18. The summary of statistics for the alternative sample is shown in Table 3. Figure 1 also shows one of the variables of interest (change in RP) for both samples. Africanist officers had, on average, slower careers during the years of leftist rule (as shown by the average change of position in the 1933 and 1934 yearbooks). When a conservative coalition came to power in 1934, Africanists experienced faster careers on average. It is noteworthy that average change of position of Africanist colonels and generals in 1934—the year in which Azaña's revisions of promotions were reflected in the military yearbook—is negative (Figure 1, Panel B). One cannot infer much from these differences because Tables 2 and 3 also reveal consistent observable differences between Africanists and non-Africanist officersFootnote 19. Africanists overwhelmingly belonged to the Infantry and the Cavalry (the two most-used corps in warfare against Berber tribes) and despite having spent less time in the Army (21.59 against 22.33), on an average Africanists held higher ranks. This last fact probably reflects the meteoric careers thanks to the promotions by combat merits in the 1920s (Franco was promoted to the rank of brigadier general in 1926 when he was only 33 years old) and the personal favours obtained by Africanists via promotions by election during Primo's dictatorship (Ben-Ami Reference Ben-Ami1984, pp. 360–362; Alpert Reference Alpert2008, p. 131).

TABLE 2 SUMMARY STATISTICS (ACTIVE OFFICERS IN 1936)

Note: An officer is considered part of the Africanist group if he spent at least one year deployed in one of the special units that formed the core of the Spanish Army in Morocco (see main text).

TABLE 3 SUMMARY STATISTICS (COLONELS AND GENERALS 1933–36)

Note: An officer is considered part of the Africanist group if he spent at least one year deployed in one of the special units that formed the core of the Spanish Army in Morocco (see main text).

FIGURE 1 CHANGE IN THE RELATIVE POSITION OF AFRICANIST AND NON-AFRICANIST OFFICERS (1933–36). (A) ACTIVE OFFICERS IN 1936. (B) ACTIVE COLONELS AND GENERALS EACH YEAR (1933–36).

3. EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS

In order to test the impact of Azaña's military policies and the impact that different administrations had on Africanists' careers, we start with La Parra-Perez's data set for almost 12,000 officers who were active in 1936. The following regression equation is run for each year between 1933 and 1936:

Regressions use two dependent variables: ΔP i(t) and ΔRank i(t). ΔPi(t) measures officer i's change of position as reflected in the military yearbook for year t. ΔRank i(t) measures officer i's change of rank between t − 1 and t. ΔRank i(t) equals 0 if the officer kept his rank, 1 (−1) if the officer was promoted (demoted) one rank, 2 (−2) if the officer was promoted (demoted) 2 ranks, and so on. The main independent variable of interest is YCA, which measures the number of years that officer i spent posted to special African units between 1910 and 1927 and ranges from 0 to 10. T measures officer i's tenure (the number of years elapsed between his entry in the military and t). R(t − 1) controls for officer i's rank in t − 1 and ranges from 1 (second lieutenant) to 10 (lieutenant general). C is a dummy for an officer's corps. P i controls for an officer's position in the scale in t − 1. A dummy that identifies officers negatively affected by the revision of promotions implemented in 1933—Demoted 1933—is included in the regressions corresponding to 1934; therefore, I 1934 is an indicator variable that equals 1 when t = 1934 and 0 otherwise. When regressing y i(t), the sample is composed of those active officers in 1936 who were also active in t (observations range from 7,143 in 1933 to 8,702 in 1936).

If officers' promotions under different administrations were not favouring or discriminating against Africanists, the careers of the members of the faction should not differ throughout 1932–36. If Africanist officers had some particular unobservable characteristic that made them more (less) apt for professional progression (e.g. by being more likely to excel at the training course to become brigadier general) and merit was governments' only criteria to determine promotions to top ranks, Africanists should have been consistently more (less) likely to be promoted than non-Africanists. If Africanists did not differ from their peers in their abilities, being an Africanist should not have had any significant impact on the chances of progressing through the scale and the coefficient for Years Core Africa should be insignificant in all years.

Table 4 shows the coefficients for yearly regressions corresponding to 1933–36. During the ruling of centre-left governments (columns 1–4), each year an officer spent in a special African unit between 1910 and 1927 is associated with a lower change in their RP (−0.009 for 1932 and −0.006 for 1933; columns 1 and 3) but the coefficient for changing rank is insignificant (columns 2 and 4)Footnote 20. The lower change of position for the median Africanist was equal to 6 per cent of non-Africanists' standard deviation. During the ruling of conservative governments, the coefficient for Years Core Africa loses its negative sign and even becomes significantly positive for changes of RP and rank in the 1936 yearbook (columns 7 and 8). For the median Africanist, the coefficient implies a career in 1935 that was 16 per cent faster than non-Africanists' standard deviation. In case of rank change, the median Africanist had, on an average, a higher chance of promotion equivalent to 7.6 per cent of non-Africanists' standard deviation.

TABLE 4 CHANGE OF POSITION 1933–36 FOR ACTIVE OFFICERS IN 1936 (OLS)

Notes: Years Core Africa measures the number of years that the officer spent posted to special African units (Spanish Foreign Legion, Native Regulars, Mehal.las, Harkas, Native Police and African Military Intervention) between 1910 and 1927. Tenure measures the number that the officer has spent in the army. Rank ranges from 1 (second lieutenant) to 10 (lieutenant general). Demoted equals 1 of the officer occupied a lower (i.e. higher-numbered) position in the scale in 1934 than 1933 and 0 otherwise. Position equals officers' number in the scale for his rank in t−1.

Robust standard errors in brackets. ***P < 0.01, **P < 0.05, *P < 0.1.

In summary, the coefficients for Africanists' change of position and rank, albeit small, generally conform to the expectations: Africanists' careers advanced less rapidly than Peninsulares' during leftist governments. A reversal of fortunes took place with the arrival of conservative governments and particularly during Gil Robles' tenure as Minister of War in 1935, when Africanist officers still active in 1936 were promoted more rapidly.

The coefficient for Demoted 1933 in Column 3 also shows the expected negative sign. Officers affected by Azaña's revisions of promotions had a slower career. Column 1 in Table 5 shows the coefficients of probit regression studying the determinants of being affected by the revisions for the sample of officers who were active in both 1933 and 1936. The dependent variable takes the value 1 if the officer was demoted in 1933 (i.e. occupied a lower–higher numbered position in the scale for 1934 than in 1933) and 0 otherwise. Africanists were particularly affected by Azaña's revisions. For each year spent in African special units, the probability of being demoted in 1933 increases by 2.4 points. The median active Africanist in 1936 was 4.8 percentage points more likely to suffer a demotion in 1933 than his non-Africanist peers. The reasons for this are not hard to understand. First, the revisions were aimed at promotions by combat merit mostly enjoyed by Africanists between 1923 and 1926. In addition, Primo's promotions by election—the other type of promotions subject to revision and potential cancellation in 1933—disproportionally benefited Africanists (Ben-Ami Reference Ben-Ami1984, pp. 360–362; Alpert Reference Alpert2008, p. 131). Azaña's revisions of promotions harmed Africanists' careers by displacing them to a lower position in the scale and reducing or eliminating their chances of promotion. It has been suggested that the revisions significantly contributed to officers' animosity towards Azaña and his political coalition in 1936 (Puell de la Villa and Huerta Barajas Reference Puell De La Villa and Huerta Barajas2007, p. 45; Sánchez Pérez Reference Sánchez Pérez, Viñas, Puell de la Villa, Aróstegui, González Calleja, Raguer, Núñez Seixas, Hernández Sanchez, Ledesma and Sánchez Pérez2013, p. 24).

TABLE 5 DETERMINANTS OF DEMOTION IN 1933 (PROBIT AVERAGE MARGINAL EFFECTS)

Notes: See Table 4. Demoted 1933 equals 1 if the officer's position in the scale in 1934 was lower than in 1933 and 0 otherwise.

Robust standard errors in brackets.

***P < 0.01, **P < 0.05, *P < 0.1.

Finally, officers' position has the expected negative and significant sign because officers eligible to be promoted to the next rank had to be chosen among the officers in the top third of the scale (therefore having a lower-numbered position in the scale). The norm was that, for those promotions under the executive's discretion, the Minister of War chose the officers who were eligible and at the top of the scale.

Coefficients in Table 4 provide the first evidence that Azaña's revisions of promotions and the «colour» of the party in power affected Africanists' careers. The data has the advantage of using a large sample containing over 1,300 Africanist officers, but it also has limitations because officers who retired before 1936 are excluded from the sample. This could bias estimates if, for example, non-Africanists with unobservable characteristics that would slow their careers left the army at a greater rate than Africanists with similar unobservable characteristics. This is plausible because artillerymen and engineers (two corps in which Africanists were under-represented) had more outside professional opportunities, thanks to their technical education and skills. Cardona also points out that the incentives that Azaña gave officers for retirement in 1931 resulted in a more conservative army because rightist officers were more likely to stay active (Cardona Reference Cardona1983, pp. 141–144). The results are not driven by the 1931 law because that year is not included in the analysis, but a similar process of self-selection of active officers could have persisted between 1932 and 1936. It is reassuring that the coefficient for Africanists changes as soon as conservative governments came to power. In order to err on the side of caution, I built an alternative data set for the entire population of colonels and generals between 1933 and 1936 to test the robustness of the results in Table 4.

The main advantage of the alternative sample is that it contains the entire population of active colonels and generals for each year between 1933 and 1936. The main drawback with respect to the initial data set is that this sample is restricted to a subset of ranks. It must be noted, however, that colonels and generals were the most important ranks for which the Minister of War had discretionary powers to determine promotions. If promotions were politically driven, these top ranks should show evidence of it.

Table 6 shows the coefficients for the four annual regressions corresponding to 1932–1936. For colonels and generals, ΔRank(t) is binary (no one was demoted or promoted more than one rank at a time); therefore, a probit regression is used, and the coefficients in columns reflect the average marginal effects.

TABLE 6 CHANGE OF POSITION AND CHANGE OF RANK FOR COLONELS AND GENERALS 1933–36

Notes: See Table 4. Rank ranges from 1 (colonel) to 4 (lieutenant general).

Robust standard errors in brackets ***P < 0.01, **P < 0.05, *P < 0.1.

Table 6 suggests a slightly different picture than the one obtained when using the sample with active officers in 1936. Results for the new sample suggest that tailwinds for Africanists' promotions were much stronger under conservatives than headwinds under the ruling of the leftist coalition. Changes in position and rank during Gil Robles' tenure as Minister of War (columns 7 and 8) remain significantly positive for officers who had spent at least one year in special African units. The median Africanist was 5.4 percentage points more likely to be promoted than non-Africanist officers. Interestingly, the coefficient for Position is not significant for change of rank in 1935 (it has the expected negative and significant sign in all other years). This suggests that, against the norm, Gil Robles' strong desire to «purge the Army of clearly undesirable elements» probably came with a willingness to promote officers who were not necessarily at the top of the scale. During Hidalgo's tenure as Minister of War in 1934, Africanists' coefficient for change of rank has the expected positive sign but is only marginally significant (P-value = 0.078). Under Hidalgo and Gil Robles, prominent Africanists, such as Francisco Franco, became division general (1934) and Chief of the General Staff (1935). Emilio Mola (leader of the conspiracy leading to the military coup in 1936) was reintegrated into the second position of active brigadier generals after having been moved to the reserve without wage by Azaña's government in 1933Footnote 21. The number of Africanist generals—which had decreased from twenty-one to nineteen with centre-left governments in 1931–1933—increased to 24.

The numbers above might not seem large. However, given the importance of hierarchy in the army, generals' actions had a cascade effect among subordinates. Recent research suggests that during the SCW, subordinates were influenced by their superior's decision to rebel or remain loyal to the government (La Parra-Perez Reference La Parra-Perez2019). Also, Africanists were not the only faction in the Spanish army. Despite being a good proxy for officers' conservatism, not all conservative officers were Africanists, and there were many military cleavagesFootnote 22. Politicisation for (or against) Africanists in promotions almost surely implies that other manipulations were in place for factions that the ruling government considered loyal (or disloyal). In an ideal Weberian bureaucracy, meritocracy, not belonging to a given faction, should be the determinant of career advancement.

The main discrepancy in the coefficients of Table 6 with respect to Table 4 concerns the promotion of Africanist officers between 1931 and 1933. Results for the yearly population of colonels and generals do not suggest that leftist governments in 1931–33 had a lower propensity to promote Africanists. Both the coefficients for change of position and the average marginal effect for changing rank (columns 1–4 in Table 6) generally have the expected negative sign for years spent in African special units but are imprecisely estimated. The discrepancy between the two samples could be explained by a selection bias in the officers who retired between 1934 and 1936. If officers who did better with Azaña between 1931 and 1933 retired (willingly or because they were marginalised by conservative governments) at a higher rate between 1934 and 1936, the Popular Front in 1936 inherited an army where groups that did worse during Azaña's mandate as Minister of War were over-represented.

Even if the results in Table 6 do not show any direct discrimination against Africanists by Azaña's government, the results for the revisions of promotions are in line with those for the sample of active officers in 1936 and suggest that centre-left governments indirectly harmed Africanists' careers. First, it must be noted that the colonels and generals who were displaced to a lower position in the scale after the revisions in 1933 suffered a negative career shock by becoming ineligible for promotion. In fact, demoted officers are excluded from the probit regression in column 4 of Table 6 because displacement to a lower position perfectly predicts failure to be promoted. Second, column 2 in Table 5 repeats the analysis of the determinants of being negatively affected by Azaña's revisions in column 1 but using the entire population of colonels and generals in the 1934 yearbook. The results are very similar to those obtained in column 1, which focused on officers active in both 1934 and 1936. Africanist colonels and generals were significantly more likely to be affected by the revision of promotions, and the coefficient is remarkably similar to that in column 1. For each year spent in special African units, the likelihood of generals and colonels being demoted increases by 2.5 points. The median senior Africanist officer in 1933 was on an average 7.5 points more likely to be affected by the revision of promotions than non-Africanist peers. Azaña's revision of promotions effectively closed the doors of promotion to an important part of the Africanist factionFootnote 23.

In summary, with the pretext that some of Primo's promotions contravened the legislation of the Parliament during the Restoration, Azaña may have used the revisions of promotions as a strategy to form a coalition that excluded Africanists from the top posts in the army. Conservative ministers in 1934 and 1935 pushed in the opposite direction by favouring Africanists for promotions to brigadier and division general. Independently of strategies followed by different governments, it does not seem that the Spanish army worked according to the impersonal and meritocratic rules of a rational–legal bureaucracy.

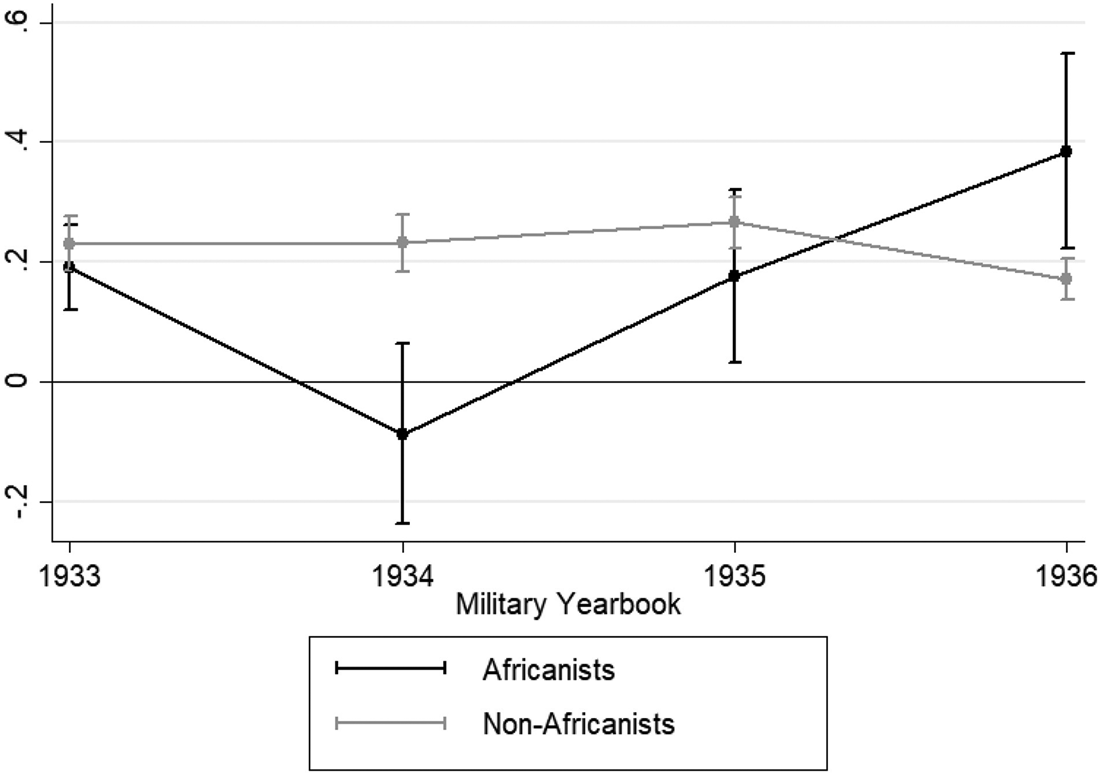

Figure 2 provides a visual representation of the main story suggested by the empirical results. The figure shows the average predicted change in relative position (APCRP) between 1933 and 1936 for Africanist and non-Africanist colonels and generals using coefficients from Table 6 (columns 1, 3, 5 and 7). Before 1934, when the Republic was ruled by a centre-left coalition, the Africanists' APCRP declined significantly. Azaña's revision of promotions even resulted in a negative APCRP for Africanists in the 1934 yearbook. With the arrival of conservative governments in November 1933, a reversal of fortunes took place. Africanist generals are predicted to experience an increasingly fast change in their APCRP after 1934, which contrasts with the slower careers predicted for non-Africanists during Gil Robles' term as Minister of War (as reflected in the 1936 yearbook).

FIGURE 2 AVERAGE PREDICTED CHANGE IN RELATIVE POSITION FOR AFRICANIST AND NON-AFRICANIST COLONELS AND GENERALS BY YEAR WITH 95 PER CENT-CONFIDENCE INTERVALS (1933–36).

Note: Average predicted change of relative position for colonels, brigadier, division and lieutenant generals between 1933 and 1936. Probabilities computed using the coefficients from Table 6 (Columns 1, 3, 5 and 7). Officers having spent at least 1 year in special African units between 1910 and 1927 are considered Africanists.

The interpretation of Africanists' different career pace under rightist and leftist government requires a final discussion of the role of skills in promotions. Promotion from colonel to brigadier general had two components: passing the training course and the Ministers' discretionary appointment. Because eligibility for promotion was conditional on officers' performance in the course, the interpretation of the previous coefficients implicitly relies on assumptions regarding Africanists' relative skills. If being an Africanist resulted in a similar or worse performance in the course than non-Africanist peers (i.e. being an Africanist did not increase professional competence as measured in the course), the results would be consistent with conservative governments favouring Africanists because there was no reason for their higher rate of promotions. If, on the contrary, Africanists signalled greater professional competence via higher grades in the training course, the correct interpretation of the results would be that leftist governments discriminated against the faction by not advancing Africanists' careers at a faster rate before 1934.

Officers' scores in the course are not publicly available, but, to the best of my knowledge, there is no evidence in the literature suggesting that Africanists were more professionally prepared than Peninsulares Footnote 24. There are two additional reasons to think that the previous results are not fundamentally driven by differences in skills in favour of Africanists. First, the decree of 2 May 1932, establishing the new methods of promotions during the Republic stated that «the grades [in the training course to promote to Colonel or Brigadier General] will rectify officers’ position in their scale since they left the Academy»Footnote 25. To the extent that officers with better grades obtained a higher new position in their scale, the variable «Position» is a proxy for officers' technical skills. The non-significance of «Position» in 1935 suggests that Gil Robles—Minister of War during most of that period—was strongly committed to selecting the officers for promotion on grounds other than seniority or merit. It is hard to believe that the significant coefficient for Africanists (a group traditionally linked to Gil Robles' ideological tendencies) is mostly due to their professional competence. Second, more than half (59 per cent) of Africanists in the top ranks of the army in 1932 were already generals. Promotion of officers at this level was entirely at the discretion of the government. Many of these generals (including some prominent Africanists such as Franco, Ordaz or Pozas) had not even passed a training course because they had been promoted to the rank of brigadier general in the 1920s. Their promotions probably responded to the Minister's choice rather than to any objective proof of professional competence.

4. CONCLUSION

Why did the Second Spanish Republic fail? The answer is inevitably complex and multicausal (Casanova Reference Casanova2007, pp. 176–184). This article provides empirical evidence for a factor that fuelled the tensions leading to the military coup that started the SCW: the politicisation of Spanish bureaucracy and, in particular, the military.

The army and its system of promotions exemplify the achievements and limitations of the Second Republic and its reformist attempts. On the one hand, Azaña's reform rationalised the army by reducing the excessive number of officers (a long-time goal of many previous governments) and took significant steps to make the system of promotions more impersonal and meritocratic, in line with the rules that characterise modern, Weberian bureaucracies. On the other hand, the reforms fell short of isolating the army from political manipulations, privilege and personalistic rules. The discretionary powers of the government to determine promotions, especially in the top ranks, persisted. In a social order that lacked consolidated control of the military, these discretionary powers resulted in the politicisation of promotions under different administrations. Africanists, a faction associated with the more conservative sectors of the army, were at the centre of the ups and downs in the military elite with each government.

The results suggest that the centre-right republican governments that ruled between November 1933 and February 1936 favoured Africanists, particularly in 1935 during Gil Robles' tenure. Conservative governments in 1935 went as far as not respecting the order in the scale when choosing the officers for promotion to brigadier or division general.

The results are also consistent with the idea that Azaña used the revision of promotions in 1933 to target Africanist officers. The data cannot ascertain whether the revisions were motivated by Azaña's concerns about the legitimacy of Primo's dictatorship or his desire to find a way to harm factions that he judged more disloyal. What seems certain is that Azaña was aware that the measure would hit Africanists' careers. The empirical analysis unequivocally supports the claim that revisions impacted the careers of those officers who had advanced more rapidly in the past, particularly those who, like Africanists, benefited from promotions by combat merit. Perhaps, as pointed out by Navajas Zubeldia, instead of revising all the promotions by combat merit, each promotion could have been evaluated independently to determine which ones were fair and which deserved to be cancelled (Navajas Zubeldia Reference Navajas Zubeldia2011, p. 101). When choosing the former rather than the latter option, Azaña might have been signalling that the negative shock to Africanists' careers was, at the very least, a desirable byproduct of the policy for him.

As suggested by Lapuente and Rothstein (Reference Lapuente and Rothstein2014), the politicisation of the bureaucracy can act as a catalyst that contributed to the violent end of the Republic. During the Second Republic, the army presented a special version of what Lapuente and Rothstein call politicisation «from above» and «from below»Footnote 26. The discretionary appointments for brigadier and division generals led to a politicisation «from above». Other countries such as the United States also allowed discretionary appointments for top ranks by a bureau. Spain in the 1930s was different from the United States in that it lacked consolidated control of its army. Spain had a well-established tradition of «military politicisation from below» in which the army acted as the arbiter of governments' fate. The two types of politicisation reinforced each other in a perverse «institutional praetorian trap». The lack of consolidated control of the military might explain why Azaña decided to maintain discretionary appointments. Against the perceived disloyalty of some military factions and given the influence that hierarchy can play in subordinates' actions following a coup, Ministers of War had incentives to make sure that the top ranks were filled with loyal officers. The expected changes in the top military ranks when the government changed, however, reinforced the army's tendency to intervene in politics when officers felt that their careers were threatened under the new government.

There are no shortcuts in the transition from natural states to open access orders. Development is a slow, gradual process (Hough and Grier Reference Hough and Grier2015). It has been noted that one feature of rational–legal bureaucracies is that «bureaucracy implies a larger organizational and normative structure where government is founded on authority» (Olsen Reference Olsen2006, p. 2). The Second Republic illustrates the difficulties that developing countries face to achieve this condition. As North, Wallis, and Weingast point out, «achieving consolidated control of the military appears to be the most difficult (…) [condition for transitioning to an open access order] for a natural state to achieve. (…) Consolidating control of the military involves severing the close links among economics, politics, and the military in natural states» (Reference North, Wallis and Weingast2009, p. 169). Solving this complicated question falls beyond the scope of this article. If anything, the perverse institutional reinforcement between politicisation from above and below adds another layer of complexity in the transition from natural states to open access orders with consolidated control of the military.

The republican reforms took promising steps towards severing the links between politics and the military, but they fell short of eradicating favouritism. The politicisation in military promotions was one of the factors that likely contributed to the final demise of the Second Republic. The consolidation of Spanish democracy had to wait.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank the participants at IX Iberometrics and in particular Diego Palacios Cerezales for their helpful comments and suggestions. The paper also benefited from comments and help from Jesús María Ruiz Vidondo, Miguel Artola Blanco and two anonymous referees. All errors are my own. The author is a member of the research project «La crisis española de 1917: contexto internacional e implicaciones domésticas» funded by the Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad of Spain, reference HAR2015-68348-R.