1. INTRODUCTION

Spain is different. The perception of Spanish distinctiveness runs deep in its historiography, especially in the Anglo-Saxon literature. Spain, at least from the 18th century onward, and possibly earlier, was thought to be backward in economic, social, political, cultural and intellectual terms. At that time, so one of the arguments goes, financial development stagnated in Spain while commercial banks were flourishing in England. The sources of slow market development in early modern Spain can be traced back to the absence of a modern banking sector as an efficient network of financial institutions, which reduces transaction and informational costs, mitigates risks, monitors firms, mobilises savings and facilitates trade.Footnote 1 Until the creation of the Banco de San Isabel in 1844 and the deepening of the banking system through the French banks in the 1850s, modern banks were inexistent.Footnote 2

However, just like France or The Netherlands, the Spanish capital market could do without modern banks because it relied on other ways to finance the economy.Footnote 3 Public granaries (pósitos), public treasuries (erarios), pawnshops (montes de piedad), merchants and merchant companies or taulas supported consumer credit and production providing mainly short-term credit.Footnote 4 Other atypical financial actors also played a very important part in the financing of the economy, as long-term credit was supplied by ecclesiastical institutions. Thanks to the research of a very wide and flourishing Spanish historiography on Hispanic financial markets, we have a better understanding of early modern financial development in Spain.Footnote 5 Besides noblemen and large landowners, monasteries, convents, religious orders, cathedral chapters, parishes, pious foundations and confraternities behaved like so many financial institutions scattered across the country. Spain, then, does not seem to have suffered from a shortage of capital.

Recently, research has focused on the role of jurisdictional fragmentation on slow market development in early modern Europe, especially on grain markets.Footnote 6 Little is known however about the fragmentation of long-term capital markets. For public annuities, Álvarez-Nogal indicated the large differential between Spanish cities in juros yields between 1540 and 1740.Footnote 7 For private annuities, studies of convents’ credit activities confirmed that these markets were mainly local since they relied heavily on family ties and close relatives. For instance, the majority of the debtors of the monastery of Santa Catalina of Corbán in Cantabria lived near the monastery.Footnote 8 In León, 92 per cent of the debtors of the monastery of San Benito el Real of Sahagún lived in the city of Sahagún or in the region.Footnote 9 Indeed, these institutions were rather economically autonomous entities. This certainly favoured the fragmentation of the supply of long-term credit since they provided the bulk of private credit at that time. But the question is, to what extent?

If we go to the extreme, ecclesiastical institutions did sometimes lend to other places further away. As we will see, the merchant Co. of the Cinco Gremios in Madrid contracted a large number of loans from ecclesiastical institutions scattered all over Spain in the mid-18th century.Footnote 10 The capital came from areas surrounding Madrid, such as Ávila, Alcalá or Lerma, but also from others further away including Pamplona, or even Padrón and Santiago de Compostela. These credit operations that crossed borders and family ties raise the question of the extent to which these markets were fragmented. A close study of the economic governance and the credit operations of some ecclesiastical institutions clearly shows that ecclesiastical institutions were not all economically separate from each other. Let us use here as a telling example the Theresian Carmelite Order. This order managed to circumvent jurisdictional and asymmetric information obstacles. It managed large portfolios of long-term loans, financed from donations, dowries and pious foundations, and in so doing, it was not different from the vast majority of ecclesiastical institutions. However, a closer look at its lending activity and a detailed analysis of its economic governance bring to light an unexpected practice. The order not only collected resources but also pooled them. Indeed, the order developed into a highly sophisticated and integrated three-tier system able to offer everything from small loans to farmers to substantial amounts to peasants, nobles, officials, merchants, local treasuries and other ecclesiastical institutions across Spain. As we will see later, the practice of this order was certainly not exceptional. At this stage, let us assess how this institution used its endowments to provide credit and who benefited from it.

2. ECCLESIASTICAL INSTITUTIONS AND LONG-TERM CREDIT IN THE MORTGAGE MARKET

2.1. The Multiple Sources of Ecclesiastical Capital

In early modern Spain, ecclesiastical institutions were a significant source of long-term credit and were able to count on a vast network of convents and parishes scattered across the whole country. For example, in the middle of the 18th century, around 2,000 monasteries and convents for men were active alongside 1,000 monasteries and convents for women.Footnote 11 All of these institutions required considerable, regular income to fund all kinds of ceremonies and to maintain their members. Besides the selling of agricultural products, taxes and rents generated by land and urban properties, they could also lend the capital that they owned or managed in order to increase their income.

Indeed, the tithes, primicias, agricultural products, members’ contributions and rents sometimes generated a surplus which they could subsequently lend out. However, financial assets donated to the institution, dowries, and pious foundations were the main sources of the ecclesiastical stock of capital.Footnote 12 Pious works and chantries were the most popular ways of transferring capital. They differed from other sources since these were monetary trust funds established for specific purposes, for example in the case of chantries celebrating a stipulated number of masses over a certain time period for the spiritual benefit of a deceased person, generally the donor. In the case of a pious work, the proceedings were devoted, for example, to widows and orphans. These were endowed with real or financial assets donated by the donor. The ecclesiastical institution in charge could then lend the capital out or rent the house in order to generate the income needed for the purpose of the pious work or the chantry. The income stemming from these assets was ring-fenced for purposes specified by the donor and served strictly to accomplish the donor’s will. The church managed this capital endowment but did not own it.Footnote 13

All of these donations and pious foundations did not exist solely for the individual’s salvation; they were also very important in Hispanic territories for many other reasons. First, ecclesiastical institutions became the keystone of social structure by developing social networks.Footnote 14 Second, donations represented part of a strategy to preserve the family estate and to maintain a family member. The endowments bestowed to a foundation were inalienable, which made it possible to protect the family estate from extravagant heirs while ensuring them with some revenues.Footnote 15 When creating a pious foundation, the donor appointed an administrator and a beneficiary. Very often, these two people were very close family members. Lastly, giving money to a convent and putting a family member there may sometimes have been a good way of obtaining access to credit.Footnote 16

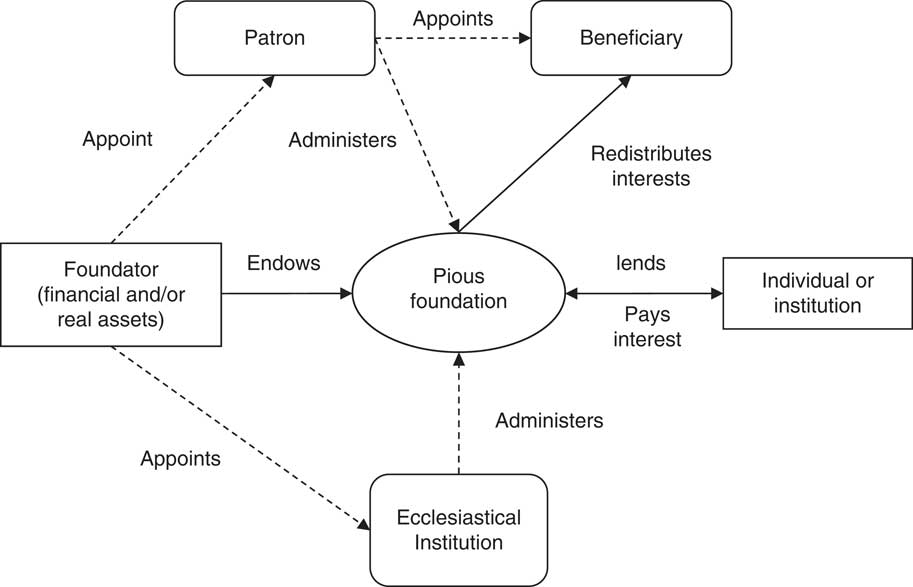

In short, as shown in Figure 1, ecclesiastical institutions received substantial amounts of capital from an array of sources, among which donations, dowries, pious works and chantries were the most important. They then lent this money to secure a steady income stream to support their members and fund all kinds of ceremonies. We now ask how large this supply of credit was.

FIGURE 1 PIOUS FOUNDATIONS AND CREDIT PROVISION

Source: Author’s elaboration.

2.2. The Contribution of Ecclesiastical Institutions to Long-Term Private Credit in the Mortgage Markets

Like many other regions in Europe, the predominant instruments of long-term private credit in Spain were redeemable annuities called censos consignativos.Footnote 17 The censo was a mortgage-backed loan supported by collateral that could be a real asset such as a piece of land, a farm, a house or another mortgage loan. One of the characteristics of the censo was that the lender could not demand the capital from the borrower; the latter repaid the capital whenever he wanted. The censo was drawn up in such a way that it represented a contract of sale of goods where the lender actually bought a rent sold by the debtor. It did not entitle the lender to recover the capital.Footnote 18 The censo was thus the only legal way to draft long-term credit contracts that explicitly involved interest at the time of usury prohibitions, as long as this did not exceed a legally enforced maximum rate.Footnote 19

In the mid-18th century, ecclesiastical institutions were largely dominant in the Spanish long-term mortgage credit market according to various historical studies and the Cadastre of Ensenada. In Castile, they received 72.9 per cent of the total rent generated by the censos, an amount of 27.86 million reales.Footnote 20 Since the legal maximum interest rate for the censos was 3 per cent at that time and the market interest rate was even lower (between 2.25 per cent and 3 per cent), the capital lent by ecclesiastical institutions in censos must have been between 890 million and 1,080 million reales, which represented between 14.5 per cent and 17.7 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP).Footnote 21 Studies on France show comparable results; in the second half of the 18th century, the stock of debt to GDP was between 15 per cent and 20 per cent or more.Footnote 22 Aragon is similar to Castile in this respect. In Girona, Congost shows that church-issued censos accounted for 75 per cent of the contracts in 1771.Footnote 23 In Navarra, ecclesiastical institutions received 75.5 per cent of the rent from censos in the municipalities of Cárcar, Guesálaz and Estella between 1750 and 1759.Footnote 24 In the kingdom of Aragon, Pérez Sarrión notes that ecclesiastical institutions lent the largest share of the capital of the censos in the second half of the 18th century. In particular, he calculates that they received 82.3 per cent of the censos rent in Zaragoza in 1725.Footnote 25

However, ecclesiastical institutions had not always been the main actors in the Spanish long-term credit market that they had certainly become in the 18th century. For previous periods, we do not have as good information on wealth as that provided by the Cadastre. But in 1638, a partial inventory of the censos in Castile revealed that ecclesiastical institutions accounted for 45 per cent of the total rent received (a figure which can be compared to that of 72.9 per cent in the mid-18th century from Ensenada).Footnote 26 This predominance of ecclesiastical institutions in the long-term credit market seems to have developed in the second half of the 17th century to reach its peak in the 18th century, which will be our main period of interest.

Thanks to the research of many scholars, we now know how ecclesiastical institutions were involved in mortgage credit activities. For instance, García García studied the economic structure of the convent of San Juan y San Pablo de Peñafiel between 1318 and 1512.Footnote 27 In the early modern period, García Martín explored the economic activities of the monastery of San Benito el Real de Sahagún, Sánchez Gómez examined the monastery of Santa Catalina de Corbán in Cantabria and Sánchez Meco the general evolution of the economy of the well-known monastery of El Escorial.Footnote 28 More recently, Maté Sardonil et al. scanned the 18th century accounting of the monastery of Silos and Siles Guerrero et al. looked at the Franciscan convent of Caños Santos in Andalusia and its credit activity in the province of Cádiz.Footnote 29 Other studies focus on broader geographical areas. Some work is at the city level; Atienza López looked at the credit activity of the convents of Zaragoza, Díaz López studied the city of Huéscar and Marcos Martín looked at Medina del Campo. Other research examines the entire regions; López Martínez evaluated the economy of feminine convents in the kingdom of Seville and Llopis Agelán studied the monasteries and convents in Extremadura.Footnote 30 They all confirm the crucial role of ecclesiastical institutions in the provision of long- and medium-term credit in rural and urban areas.

Using the account books of these institutions, local credit operations can easily be reconstructed. For instance, in Medina del Campo, Marcos Martín observed that ordinary people represented 72 per cent of the borrowers but only 35 per cent of the capital lent.Footnote 31 These could be farmers, small landowners, craftsmen or merchants.Footnote 32 For these people, borrowing capacity was related to land and was therefore limited, as most farmers owned little land to use as collateral. Usually, they borrowed no more than 2 years of a labourer’s wages.Footnote 33

With regards to rural credit, ecclesiastical institutions were the main providers of agricultural loans.Footnote 34 Spread throughout Spain, including the most remote parts of the country, they were able to address the basic credit needs of small landowners and farmers. All of the local convents were important credit centres for rural dwellers who ran short of capital. In his work on the province of Zamora, Álvarez Vázquez noted that the demand for agricultural credit in the absence of a modern banking system was satisfied by ecclesiastical institutions.Footnote 35 These loans, although usually small, were sufficient for the recipient to survive a storm or build a new house. Ecclesiastical institutions also participated actively in the agricultural improvement movement in early modern times. For instance, the large monasteries around Barcelona, the cathedral of Barcelona, as well as more scattered convents, such as the convent of Poblet, appear in the records of hydraulic establishments and participated in the construction of hydraulic infrastructures.Footnote 36

Usually, the two largest borrowers were the elite and the cities. They borrowed large sums of capital in Medina, almost three times the amount lent to the ordinary people in the case of the Don, and nearly fourteen times for the high nobility or the cities.Footnote 37 The purpose of the loan was scarcely mentioned. For the elite, whenever it is specified, the loan served to get through some financial difficulties, to build a new house or to refurbish an old one. In the case of the cities, these loans financed not only the donations to the king but also the maintenance and construction of public infrastructures and the provision of basic public services.Footnote 38 For example, in Elorrio, almost 60 per cent of the amount lent between 1780 and 1789 (367,000 reales), was invested in the construction of roads.Footnote 39

Sometimes, the borrower was another ecclesiastical institution. In Medina, 10 per cent of the capital lent involved two ecclesiastical parties.Footnote 40 In most cases, these loans allowed them to finance new infrastructures or confront financial difficulties.

In sum, ecclesiastical institutions received considerable amounts of capital through donations, dowries or pious foundations that they subsequently lent via censos. They came to dominate the mortgage market, representing 72 per cent of the capital lent in the mid-18th century. This dominant position was certainly unmatched in Europe. Studies on France, The Netherlands or England do not show such a large share of ecclesiastical institutions in long-term credit.Footnote 41

3. INTERREGIONAL FLOWS OF CAPITAL AND INFORMATION WITHIN A NATIONALLY INTEGRATED ORDER

In this section, I will further explore the credit operations of ecclesiastical institutions at this time via the detailed analysis of a single order, the Congregation of Spain of the Theresian Carmelite Order, a Spanish order established during the Counter-Reformation.Footnote 42 There are good reasons for this kind of case study. As mentioned earlier, a vast number of studies show the contribution of ecclesiastical institutions in long-term local credit markets. Such research is extremely valuable, but these studies all analyse particular institutions as isolated cases.Footnote 43 They therefore do not show the way in which an entire religious order functioned in terms of providing credit — including the different convents, monasteries and other local institutions — and are thus partial if one studies market integration. In this respect, the Congregation of Spain of the Theresian Carmelites developed a highly sophisticated three-tier system, divided between local convents, provincial houses and, at its centre, the General Curia.Footnote 44 In Madrid, the General Curia, located in the convent of San Hermenegildo, ruled the entire Congregation. Each province of the Congregation was then ruled by a provincial house, usually located in the provincial capital. Finally, each local convent was under the authority of its provincial house and, by transitivity, the General Curia. The analysis of the economic governance and lending activity at each level of this system (local, provincial and the General Curia) reveals an impressive credit organisation, nationally integrated, and able to lend, borrow and pool capital. The specialisation at each level of the system allowed the organisation to offer everything from small loans to local farmers to substantial loans to city councils, the monarchy, the Madrid elite and merchant companies.

I first studied the economic governance of the first tier of the order, namely local convents. The Theresian Carmelite Order, like all ecclesiastical institutions, had to keep records of its incoming and outgoing cash and other goods. Every credit operation was recorded in the annual account book (libro de cuentas generales) and loan book (libro de censos) in each convent.Footnote 45

The accountancy of the local convents was controlled by their respective provincial houses. Each year, the provincial bursar and the provincial prior would visit every convent in the province and check the validity of both the procedures and the accounts.Footnote 46 In addition to controlling for fairness and ensuring that the convent’s economy was in good health, this denotes the desire of the General Curia to standardise practices within the order. These visits were also an occasion for the provincial house to exchange information with its local convents. Indeed, the study of the economic governance of the order’s local convents reveals the impressive attention given by the monks to their credit activities at their own level, as well as their connection to the rest of the order. As such, they were simply a part of an activity which developed nationwide and contributed to a nationally integrated organisation.

The convent’s monks or nuns met every week in the library to discuss and vote on the convent’s daily decisions. Each convent had to take minutes and, in particular, to record the economic decisions taken, in meeting reports (libros de acuerdos). I was able to study two of these reports from two different convents of the Theresian Carmelite Order, which constitutes, to my knowledge, the first analysis of this type of source.Footnote 47 These reports have been enlightening to understand the economic governance of each convent.

Hence, on the first page, the meeting report of the convent of Bolarque stipulates: «Our Definitory decided that in every convent there be a special book where written down and noted are the decisions made during the conventual chapters concerning their rents and economy».Footnote 48 The report added that this was a decision made by the General Definitory of the Theresian Carmelite on 17 September 1727, to fight against: «the serious inconveniences and disasters that our convents are enduring, that there is no special book in which to write down the agreements and determinations made in the conventual chapters concerning rents, economy, and well-being of the convents».Footnote 49 This means that the General Curia of the Theresian Carmelite not only controlled the good administration of local convents but also produced some rules of good management. In particular, decisions to lend or borrow money were recorded conscientiously.

The report of these decisions accounts for the economic rationale of the ecclesiastics. Problems of asymmetric information were crucial in early modern credit markets, especially regarding the quality of collateral. Local convents and churches knew almost everybody in the village and could check on collateral in case of doubt. For example, the monks of the convent of Bolarque agreed to lend 5,850 reales to Juan de Burgos after having checked his mortgage and deemed that it was sufficient: «Juan de Burgos el Menor, resident of Almonacid de Lurita, came asking for a censo and, the mortgages being examined, he gave a well-sufficient guarantee, and the holy community offered and agreed to give to Juan de Burgos the said 5,850 reales via a censo».Footnote 50 Before lending money, they analysed and examined the debtor’s guarantees and decided during their weekly meeting whether these were sufficient. It was not difficult to check collateral, since the house or the farm was usually close to the convent. As we have seen in the case of Medina, local convents – the first tier of the system — provided credit mostly to agriculture, the city council, and the local elite. This credit was mainly local and involved small loans. Collateral was also very important to negotiate the interest rate with ecclesiastics. The high nobility and cities were offered lower interest rates than ordinary people, in general below three per cent, which reveals the quality of their collateral compared with that of ordinary people.Footnote 51

More importantly, these reports show the way in which local convents were connected to the rest of the order relative to credit activities. A convent could either decide to lend money if it had excess capital, as we have just seen in the preceding example, or, on the contrary, it could borrow from the order, or other sorts of institutions or individuals, with the authorisation of the provincial prior, if it ran short of capital. The following example is particularly enlightening. The city of Almonacid asked the convent of Bolarque for a censo bearing a 2.5 per cent interest rate in order to pay off all the censos that the city had sold at 3 per cent. This was a mere debt restructuring operation in order to reduce the debt burden of the city. The loan of the city of Almonacid, however, also shows the economic links between the General Curia and local convents. The weekly report says:

On 14 September 1738, Our Father Joseph Thomas, Provincial of the Theresian Carmelite, granted license to this community so that it could take out a censo of forty or fifty thousand reales so that with them and other available portions that were in the three-key safe of this house, they could subrogate in this community and against the city of Almonacid all the censos, that in favour of different subjects had the said town bearing a three per cent interest rate, and now reduced to two and a half, whose reduction the said community deemed convenient … And indeed, [this community] sold a censo of 2,000 ducats at the rate of two and a half to the General Curia of Madrid, as it appears in the deed signed by the said community on 10 January 1739. Br. Juan de Jesus Maria. Br. Diego de la Madre de Dios.Footnote 52

The convent of Bolarque did not have enough cash to accept the request of the city of Almonacid. However, it was able to borrow it from the General Curia at a low-interest rate, and, as a result, offer a lower interest rate to the city than its competitors. This example indicates that local convents were able to offer an almost unlimited supply of capital, even in local and remote areas. This also shows that although ecclesiastical lending was mainly local, capital sometimes flowed across large distances and information gaps could be filled by these religious credit networks.

Another important fact derives from this example. Competition between lenders was indeed fierce in long-term credit markets. The convent of Bolarque was competing with other local residents and institutions. It offered a 2.5 per cent rate in order to win the tender. Not only did ecclesiastical institutions compete with other individuals or institutions but they also competed with each other. For instance, in 1758, the city of Toro requested a censo of 140,000 reales from the cathedral chapter of Zamora and specified that it was inclined to pay only 2 per cent adding that it already had an equivalent offer from another institution.Footnote 53 Interregional capital flows from the supply side actually fostered competition within local mortgage markets.

In short, analysis of the economic governance of the local convents of the Theresian Carmelite shows an impressive economic rationale for ecclesiastics. They competed with other ecclesiastical institutions and decided within the community whether to lend or not, and at what price considering the borrower’s identity and the collateral provided. In addition, meeting reports show that these local convents had economic links with their General Curia. If they ran short of capital because of financial difficulties or if they could not satisfy the demand for larger loans from a local individual or institution, they could borrow this sum from their order. This may appear obvious, but these intra-order and interregional capital flows have never been studied, resulting in an overly localised impression of the mortgage credit market.

At the second level of the three-tier system of the Theresian Carmelite, we have the order’s provincial houses (procuradurías provinciales). One of these provincial houses was that of the province of Old Castile, located in Valladolid in the convent of San Benito el Real. This second level pooled all the excess capital earned by the convents in the province in one sole fund, which was then lent to other ecclesiastical or non-ecclesiastical institutions and all kinds of individuals with sufficient collateral.Footnote 54 As opposed to local convents, provincial houses only lent little to ordinary people and larger amounts to local nobility and to people and institutions further away.Footnote 55 Finally, the provincial house could also lend to cities or even sometimes to public monopolies such as the Tobacco Monopoly (Renta de Tabaco).Footnote 56 Capital was also lent to Theresian convents at this level, as no less than 25 per cent of capital was sent to the convents in the province.

The last level of the three-tier system pushes the logic a step further. I here consider the account books of the General Curia. Two of these are of central importance: the annual account book of the General Curia, and the loan book recording all of its censos. These reveal that the General Curia was the keystone of the credit institution. They also provide the details of an important national institution present throughout Spain. Capital flowed from the top to the bottom and from the bottom to the top. Every 4 years, all the provincial priors of the Congregation of Spain had to sign a power of attorney before a notary in Madrid in favour of the general prior. This gave the general prior the ability to take out a loan and redeem it on behalf of any of the convents of the Congregation or represent them at court. Below is the proxy established in 1747 by the notary Don Manuel Miñon de Reynoso:

According to that public power of attorney, we Fr. Diego de San Rafael, General Prior of the Theresian Carmel Order, of the discalced Carmelite monks and nuns of Primitive Observance of the Congregation of Spain … and in behalf of the … definitors, prelates, and convents of monks and nuns of our Order … together, consent and give our complete power, that which is needed and necessary, to Fr. Paulino de San Joseph, member of our Order, and General Prior.Footnote 57

With this power of attorney from the order’s convents, the General Curia had complete authority to act for the whole community. In particular, it could act as a financial intermediary for the order.

Indeed, the General Curia could lend some capital on behalf of one particular convent. When a particular convent wanted to lend capital, it could choose between two options. It could either find a borrower nearby, within the city and its surroundings, or it could deposit the capital in the General Curia and charge it to lend this capital. In August 1791, for instance, the convent of monks of Medina del Campo deposited 8,000 reales in the General Curia and asked the mother cell to lend it: «Plus 8,000 reales that gave our Prior of Medina del Campo to be lent via a censo».Footnote 58 On 17 August 1791, the General Curia lent the said 8,000 reales of the convent of Medina del Campo to the pious schools of the San Fernando College in Madrid.Footnote 59 There are two striking facts here. First, Medina del Campo is 157 km from Madrid, which means that the General Curia could easily act as a financial intermediary for distant areas. Without the General Curia, the deal could not have been made. Second, we can note the speed of the General Curia’s actions. We do not have the exact day when the capital was deposited in the General Curia, but we do know that it was between the 1st and the 17th of August. As a result, a maximum of 2 weeks separated the General Curia’s receipt of the payment from Medina from its subsequent lending out.

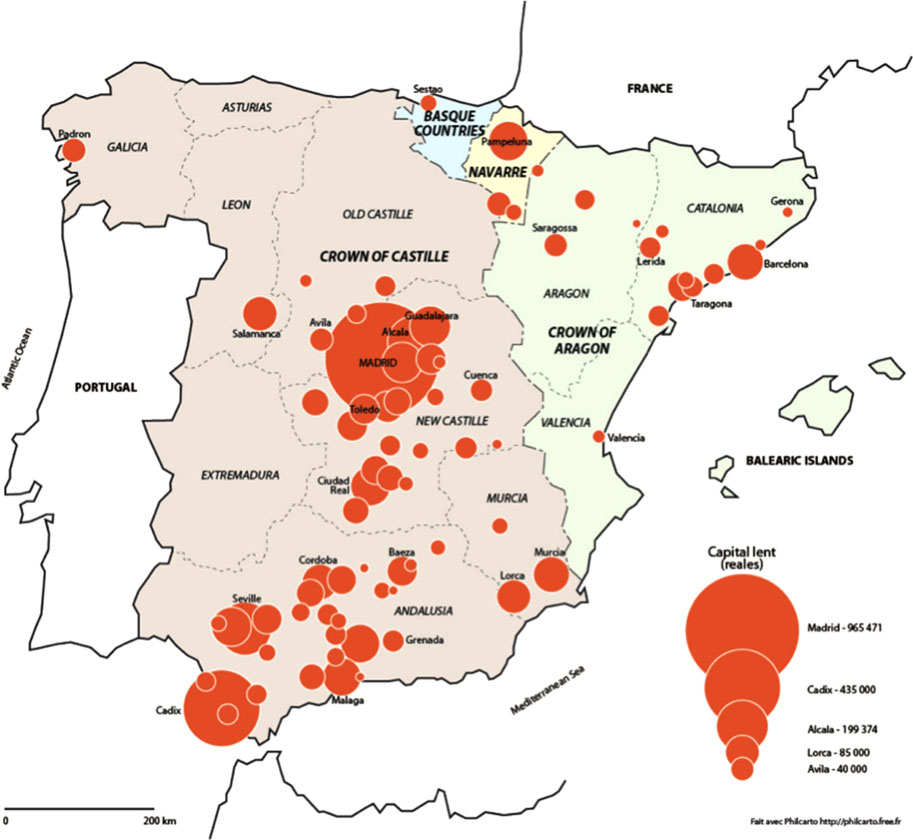

The General Curia not only lent capital on behalf of a particular convent but also pooled capital from a number of convents to meet the demand for larger loans. The example of the Marquis of San Juan de Tasso is particularly interesting.Footnote 60 The Marquis lived in Madrid and was a member of the Council of Castile, which was basically the Spanish government. He asked the General Curia of the Theresian Carmelite for a censo of 400,000 reales, a tidy sum in an era when a local day labourer might earn little more than 860 reales a year. The General Curia had to pool, in Madrid, the capital from nine convents of nuns and monks throughout Spain and draw on the beatification fund, which was one of the investment funds of the General Curia. As Figure 2 shows, thanks to the action of the General Curia, capital could come from as far as the city of Padrón, which is 620 km from Madrid. By 1 March 1762, the General Curia was able to lend the amount requested by the Marquis. Capital thus flowed across the whole of Spain. In addition, the Marquis did not make payments to each convent, but rather in Madrid to the General Curia, which was much more convenient for him. The General Curia then redistributed the money to each convent, since they had to meet their obligations, such as maintaining the chantry priest.

FIGURE 2 THE ORIGIN OF THE MONEY LENT BY THE GENERAL CURIA TO THE MARQUIS OF TASSO

Note: The capital was divided between the Pastrana fathers, Segovia fathers, Medina de Rioseco fathers, Toro fathers, Palencia fathers, Fontiveros fathers, Batuecas fathers, Padrón fathers, Madrid fathers, Lerma mothers and the beatification fund.

Source: BN, MSS/3644, Libro de censos de los conventos de Carmelitas Descalzos, p. 210.

The General Curia also acted as a lender. It had at its disposal two main investment funds: the common fund (caudal común) that was used for the daily expenses and investments of the Curia and the beatification fund (caudal de beatificaciones) that was used to support the beatification of the order’s nuns or monks and which served as an investment fund. Table 1 shows how the lending activity of the General Curia was divided between its various funds and the funds of each convent.

TABLE 1 INSIDE THE GENERAL CURIA: ORIGIN OF THE MONEY LENT, 1700-1807

Sources: BN, MSS/3644, Libro de censos de los conventos de Carmelitas Descalzos; BN, MSS/12843, Índice de los Censos y Escrituras de los Carmelitas Descalzos de España.

The Curia alone lent 52 per cent of the capital through its two main funds — the beatification and the common funds — and two pious memories — those of Santo Tomas and Doña Maria de Torres. It also participated in a pool of lenders contributing 21 per cent of the total lending. Finally, the Curia was responsible for matching lenders and borrowers for the remaining 26 per cent. As a result, roughly half of the capital lent by the General Curia came from its own coffers and the other half was pooled from Theresian convents.

The General Curia not only used these funds for its lending activities in Madrid but also mobilised them to send capital to its local convents, as we have seen through the local meeting reports. Whenever a convent needed money, it could take out a loan from one of these funds. Clearly, local convents were not limited by their own resources. At any time they could, if they wished, obtain supplementary resources from the General Curia, as the convent of Bolarque did for the loan to the city of Almonacid. In this respect, they were able to offer their neighbourhood (and in particular rural dwellers) an almost unlimited supply of capital.

Figure 3 shows the amounts lent by the General Curia to its local convents. Of 196 convents, 101 throughout Spain borrowed from the Curia. In New Castile, they received almost half of the capital lent by the Curia (44.3 per cent), of which 43 per cent remained in Madrid. Andalusia was the second main recipient of the General Curia’s resources (34.3 per cent) but also had the largest number of convents (26.9 per cent).Footnote 61 Figure 3 also provides evidence that the General Curia’s lending crossed strong jurisdictional borders. Almost 13 per cent of the capital lent was sent to historic territories that were not part of the Crown of Castile: Catalonia, Aragon, Valencia, Navarre and the Basque Countries.

FIGURE 3 GENERAL CURIA’S CROSS-BORDER LENDING TO ITS LOCAL CONVENTS, 1700-1807

Sources: BN, MSS/3644, Libro de censos de los conventos de Carmelitas Descalzos; BN, MSS/12843, Índice de los censos y escrituras de los Carmelitas Descalzos de España.

Thanks to its network of convents, the General Curia could therefore make loans in any part of Spain despite jurisdictional barriers. Indeed, local control over justice and the different legal systems inherited from the very nature of the Spanish composite monarchy imposed massive transaction costs on local credit market activities. Legal fragmentation increased legal risk in the capital market and impeded capital mobility between historic territories.Footnote 62 Even the promulgation of the Nueva Planta decrees by Philip V from 1707 to 1716 did not greatly affect the historic territories’ legal systems. Despite later claims to the contrary, the Crown of Aragon retained its essentially constitutionalist and contractual character.Footnote 63 For the General Curia and its local convents, lending to each other was thus a powerful way to bring capital close to the customer and a method for circumventing jurisdictional obstacles and solving asymmetric information problems. Still, Figure 3 suggests that less capital was sent to the Crown of Aragon than to Andalusia, which raises questions about the determinants of the destination of these loans. Only some hypotheses, rather than clear-cut answers, can be offered. This shows that strong jurisdictional barriers (between Castile and Aragon) still had a persistent effect even within a nationally integrated organisation. It could also have been simply the result of greater demand. However, Aragon (especially Cataluña) was one of the more dynamic regions at the time. An alternative explanation then lies in the different «investment» strategy adopted in Aragon by ecclesiastical institutions. Cuevas showed that from the mid-18th century, ecclesiastical institutions in Valencia withdrew from local credit markets. Inflation and the increase in crop yields led them to invest in land and to reduce their lending activities progressively, while commercial and urban credit developed.Footnote 64 Last, the destination of the loans could merely have been driven by the order’s own internal biases. Theresian convents in Castile had been established for longer periods of time and had developed a better network that allowed them to capture more loans than their counterparts in Aragon.

Was the Theresian Carmelite Order representative of other ecclesiastical institutions? The integrated multi-tiered economic structure described here was indeed very sophisticated and contrasts with what is commonly observed for the secular clergy. Secular clergy entities — parishes and bishoprics — seem to have been more autonomous. Studies of cathedral chapters’ lending activities do not reveal interregional credit relations between bishoprics or between parishes and bishoprics.Footnote 65 No national institution coordinated Spanish dioceses and the economic structure of this clergy was thus rather horizontal. It might have been the case that recent orders, born during the Counter-Reformation, developed modern management techniques.Footnote 66 At the same time, another order — the Society of Jesus — developed the same modern management techniques as the Theresian Carmelites.

The Jesuits, certainly the richest order in the first half of the 18th century, performed the same financial roles as the Theresian Carmel Order. Jesuits’ provincial houses were able to pool money in order to satisfy the demand for larger loans, administer colleges’ capital, and also send capital to colleges in need of funding. The loan book of the Jesuits’ provincial house of Old Castile bears testimony.Footnote 67 Table 2 records all the outstanding censos in 1764 and reveals a similar economic structure to that of the Theresian Carmelites.

TABLE 2 OUTSTANDING LOANS OF THE JESUIT PROVINCIAL HOUSE OF CASTILE, 1764

Sources: AHN, Sección Clero-Jesuitas, Legajo 941.

First, as a lender, the provincial house which was located in Valladolid lent 200,000 reales to the city council of Salamanca. Second, it was pooling capital for colleges all over the province. For example, on 5 September 1752, it pooled 110,000 reales from the college of Santiago, 84,000 from that of Segovia, 4,906 from that of Vitoria and 2,740 from its own fund to lend 201,646 reales to the Count of Ribadavia. Segovia, the closest city, is 116 km from Valladolid, and Santiago is 450 km away. Third, the provincial house could act simply as a financial intermediary. For example, on 24 April 1761, it lent 50,000 reales on behalf of different colleges of the province to the college of Arevalo located 90 km from Valladolid.

4. THE POSSIBILITIES OF THE INTERREGIONAL MARKET: BIG LOANS, BIG CREDITORS

Without any doubt, the possibilities of forming interregional capital flows also allowed for the potential of meeting the credit needs of what we might call the big censos market. Thanks to these capital flows, large corporations — cities, mayorazgos, etc., — and, gradually, important merchants who needed large amounts of money could take out very substantial loans and reduce the costs of a small local market, which in principle could lead to a multiplication of small censos with high transaction costs. This type of activity was not new. Since the 16th century, important merchants had used this type of credit — first as loans in the form of obligations that were consolidated as censos on the mayorazgos.Footnote 68 The interesting thing for us here is how consortia formed through religious orders, which in turn reduced transaction costs, were able to carry out that same function.

The account books provide detailed information on individual loans with the date of the contract, the borrower’s name, and the Theresian convents involved. The interest rate and the redemption date are provided in many contracts, but not systematically.Footnote 69

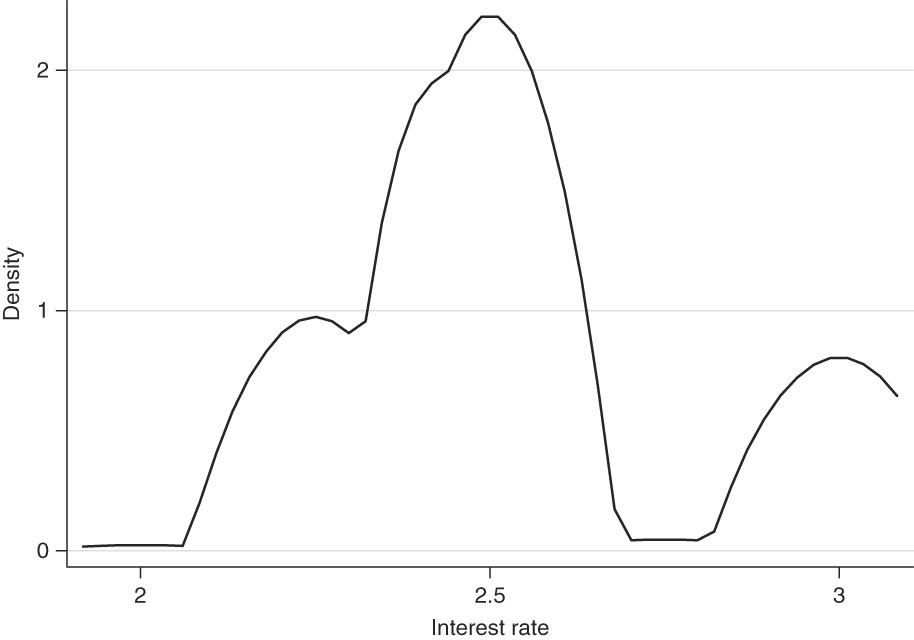

Until 1705, the Theresian Carmelite offered loans at the usury limit (5 per cent) or not at all. Figure 4 plots the distribution of loans by the interest rate charged after the reduction in interest rates in 1705. One peak is at the legal maximum for the period — 3 per cent — but most borrowers paid interest below the legal maximum, around 2.5 per cent. The amount of the loan did not seem to have been a clear determinant of the interest rate charged, unlike the type of borrower. Of those borrowers paying lower interest, ecclesiastical institutions borrowed on average at 2.5, whereas the nobility paid 2.75.

Figure 4 Distribution of interest rates, 1705-1807

Note: Epanechnikov kernel estimation.

Sources: BN, MSS/3644, Libro de Censos de los Conventos de Carmelitas Descalzos; BN, MSS/12843, Índice de los Censos y Escrituras de los Carmelitas Descalzos de España.

Table 3 summarises the General Curia’s lending activity between 1700 and 1807. Lending concentrated in the second half of the 18th century and then declined following the desamortización laws which started in 1798. By way of comparison, the General Curia was similar in size to Hoare’s Bank, a small goldsmith bank in London studied by Temin and Voth.Footnote 70

TABLE 3 LOANS OF THE GENERAL CURIA, 1700-1807

Sources: BN, MSS/3644, Libro de Censos de los Conventos de Carmelitas Descalzos; BN, MSS/12843, Índice de los Censos y Escrituras de los Carmelitas Descalzos de España.

We first note the small number of clients who were ordinary people. They borrowed on average 55,653 reales, which suggests that they were not so «ordinary». Unfortunately, there is no information on the purpose of the loan or the borrower’s profession. On the contrary, Dukes, Counts, Dones and Doñas are at the top of the list, accounting for 31.9 per cent of the capital lent, for an average amount of 100,538 reales. These individuals represented the high nobility, lived in Madrid, and held important official positions. Some were also part of Spain’s commercial and financial elite. Examples include Don Andres Diaz Navarro, a former minister, the Duke of Medina Sidonia, Pedro de Alcántara Pérez de Guzmán y Pacheco, a member of one of the most important and oldest families in Spain and fellow of the Royal Society from 1749, and Don Joseph Ignacio Goyeneche, a former Secretary of State.Footnote 71

Ecclesiastical institutions accounted for a large part of the loans of the General Curia, with 51.2 per cent of the amount lent, divided between Theresian Carmelite institutions, with 18.4 per cent of the loans, and other ecclesiastical institutions for the other 32.8 per cent. This reflects the substantial role of the General Curia in sending capital to convents that were short of it, confirming its central position within the order.Footnote 72

Another 7 per cent of the capital was lent to cities and to the state. The cities were often close to Madrid, such as Vicálvaro or Colmenar Viejo, but some were quite far away such as Rus (province of Jaén) or Salmeroncillos (province of Cuenca). Royal monopolies such as the Tobacco Monopoly and the Mail Monopoly were also the destination of various loans. These were long-term loans provided to the government, like the censos secured on the Tobacco Monopoly sold in the late 18th century to finance warfare during the American Independence War and the French Wars.Footnote 73

Last, I noted from the account books of the Theresian Carmelite that the order lent massively to merchant companies such as the Royal Co. of Trade of Toledo, the Co. of the Cinco Gremios, or the Co. of Buena Fe of Craftsmen & Silversmiths (Compañía de la Buena Fe de Artífices y Plateros). Indeed, a notable share goes to these companies, with a striking average amount lent of 201,318 reales. For instance, the Royal Co. of Trade of Toledo took out seven loans recorded here. This organisation was created in 1748 to encourage trade in the Toledo region. It borrowed large amounts of capital from the Theresian Carmelite Order at the time of its creation, with 520,000 reales in 1749, 1,045,000 in 1750, and 200,000 in 1751. The General Curia pooled the capital needed by the company from no less than 19 convents scattered across Spain from Salamanca to Santiago de Compostela and Pamplona, the beatification fund, the common fund, and Doña Maria de Torres’ pious memories.Footnote 74 Later, the General Curia provided 202,700 reales in two loans in 1754 and 1758 to the Co. of the Cinco Gremios. This shows that the Theresian Carmelite three-tier system managed to pool the necessary capital from everywhere in Spain and channel it to Madrid, to finance merchant companies. As far as trade is concerned, ecclesiastical institutions participated in the financing of commercial activities and international trade. The memorandum on the reduction of the interest rate borne by the censos written around 1720 by the cathedral of Valencia for the Council of Castile bears testimony. The cathedral chapter wanted to protect the development of manufacturing, stating that: «[the interest rate reduction] would cause difficulties to the desired development of so many manufacturers of silk and wool, that flourish in this kingdom: via the censos, [these manufacturers] would find considerable funds». Later in the document, the cathedral defended the censo arguing that: «With the censos, driving capital towards lay people, and supporting trade with this money».Footnote 75 For the cathedral chapter of Valencia, there is no doubt that the censo, by lending to merchants and fostering trading activities, was one of the keystones of Spanish commercial activity. These connections between ecclesiastical institutions and economic activities should not come as a surprise since ecclesiastical institutions and ecclesiastics could be very successful merchants. This can be illustrated by the case of the Jesuits. The Jesuits were well known for their agricultural activities, especially in New Spain.Footnote 76 Until their extinction in 1767, they traded goods between Spanish America and Spain and established contacts with other merchants across the whole of Europe.Footnote 77

To sum up, in contrast to many traditional banks that focused on only a small category of the population and thanks to the flows of capital based on the trust among different institutions belonging to the same order, the credit activity of the Theresian Carmelite Order covered the whole range of potential borrowers, from very small loans in rural areas, mainly to farmers, to a few large loans to the urban elite. The analysis of its economic governance shows that an important credit institution existed, one that was organised into a highly sophisticated three-tier system acting at a national level. The General and provincial houses were in charge of pooling and lending on a large scale, while the convents were more focussed on local credit. The General Curia lent much larger amounts of capital than provincial houses and local convents. It specialised in large loans, since it could pool capital from convents of the order all over Spain. Finally, thanks to its intra-order flows of capital, the order circumvented jurisdictional barriers and certainly reduced resource misallocation.

5. CONCLUSION

During early modern times, ecclesiastical institutions became the most important providers of long-term credit in Spain. Although they only engaged in mortgage lending and benefited from a particular kind of deposits since the depositor could not withdraw funds, the monks and the nuns acted almost like traditional bankers by pooling, lending and borrowing money. In this paper, I considered the case of the Theresian Carmelite Order during the 18th century, when ecclesiastical credit was largely dominant and characterised the functioning of that particular credit market. I found that ecclesiastical institutions acted through a vast network of convents and monasteries, supplying everything from small loans to farmers in a local market to substantial amounts to nobles, merchants, officials and local treasuries across the whole country and beyond. Their three-tier system, with the General Curia in Madrid at the top and then the provincial houses and the local convents scattered all over Spain, allowed them to address all kinds of demands, to solve asymmetric information problems and to circumvent the strong jurisdictional barriers inherent to these markets.

Indeed, like the majority of its European counterparts, Spain suffered from coordination problems inherent in a decentralised state. As a second best, some ecclesiastical institutions overcame these obstacles in the long-term capital market. Compared with modern banks, they had their own purposes and constraints which certainly had an impact on their economic efficiency. However, the interregional flows of capital that they performed undoubtedly alleviated misallocation at the time.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I thank Blanca Sánchez Alonso, the editor of Revista de Historia Económica — Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History and the anonymous referees for their excellent comments. I am grateful to my advisors, Jérôme Bourdieu and Gilles Postel-Vinay for their advice and support. I thank Oscar Gelderblom, Alejandra Irigoin, Enrique Jorge Sotello, Eric Monnet, Vigyan D. Ratnoo, Bartolomé Yun Casalilla, and my colleagues at the PSE as well as the participants of the seminars at the PSE and the LSE, and audiences at the World Economic History Conference 2018, the Historical Economics and the Economics of Religion Workshop 2015, the European Association for Banking and Financial History Workshop 2014 and the Deuxièmes Journées Res-Hist 2014. I am grateful to the Fonds Sarah Andrieux, the Fonds de Recherche PSE and the Région Ile-de-France for funding the project. All errors are mine.