1. INTRODUCTION

By the end of the 18th century, Buenos Aires had become the thriving commercial centre of the Spanish Viceroyalty of Rio de la Plata, an entity that roughly covered the modern-day territories of Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay and Uruguay. Despite the economic growth of the Plata region during the second half of the century, the city was dependent for its military and administrative expenses on the regular supply of funds from the treasuries of Upper Peru, mainly those of the Potosí mining area. These internal colonial subsidies, known as situados, formed the cement that held much of the Spanish Empire together; fiscal surpluses from revenue-rich areas financed the areas encumbered by administrative and military burdens, enabling Spain to retain her foothold in the Americas.

Around the turn of the century, however, the situado revenues started to decline and eventually disappeared altogether (Halperín Donghi Reference Halperín Donghi1982; Amaral Reference Amaral, Amaral and Prados de la Escosura1993, Reference Amaral2011). At the same time, the coming of the French Revolutionary Wars and the occupation of Spain by Napoleonic armies led to political instability in the La Plata region, accompanied by the need to mobilise resources for war. The occupation of Buenos Aires by British troops in 1806 and 1807 sparked a process that gave birth, after the revolution of 1810, to a de facto independent republican order, with major financial consequences. In 1813, the local authorities of Buenos Aires resorted to the expedient of forced loans, because taxes and other contributions had proved insufficient to pay for increasing war costs. The promissory notes (pagarés) issued against these loans—as well as the use of bills of exchange to finance military expenses—resulted in an unprecedented form of paper circulation in the region. The central objective of this essay is to analyse the mechanisms at work in such exchanges and to show how they contributed to institutional and economic change.

In a pioneering and still authoritative study, Amaral analysed the characteristics of forced loans and the use of pagarés as a substitute for coin when paying tax debts (Amaral Reference Amaral1981, pp. 40-49). Moutoukias recently added analyses of the circulation of these public promissory notes among individuals. This important issue, which researchers have tended to overlook until now (Moutoukias Reference Moutoukias2015, Reference Moutoukias, Bertrand and Moutoukias2018), will form the focus of the current study. We present a range of new evidence in order to examine the interactions among the circulation of financial paper, the financing of war and institutional change. We look at the local dismantling of the colonial legal framework for Atlantic trade that limited or prohibited direct commerce with foreign powers, as well as the weakening of the merchants' guild, which had controlled that trade and played a key role in the local political order of the ancien régime.

The problem of institutional transformation in revolutionary Latin America has been conceptualised by Irigoin and Grafe in terms of political fragmentation. They argue that the crisis of legitimacy of the Spanish monarchy and thus the collapse of the arbitrating power caused by the Napoleonic occupation of 1808, turned «fiscal interdependence between regions into beggar-thy-neighbour strategies and internecine conflict», and that this, in turn, led to territorial fragmentation (Irigoin and Grafe Reference Irigoin and Grafe2009). Territorial fragmentation is not similar to institutional change in every respect, however, and this aspect was not dominant in all cases; it did not affect New Spain, for instance. In fact, in the Rio de la Plata, competition for fiscal resources was not the cause but the consequence of the segmentation of territories based on a plurality of jurisdictional and political scopes (Morelli Reference Morelli2005; Ternavasio Reference Ternavasio2007; Dedieu Reference Dedieu2010). The particular relevance of the Buenos Aires case lies in the fact that the local mobilisation of resources for war produced major institutional innovations, which were by no means just the political effect of the Napoleonic occupation of Spain in 1808 and the ensuing crisis of the Spanish monarchy.

In contrast to Irigoin and Grafe's argument, the Spanish imperial political order in America could be conceptualised in terms of independent but articulated institutional spheres; the main ones being, on the one hand, the political community of the city and, on the other hand, the organisations and mechanisms of the financial, military and political power of the Crown, including the situado financial transfers. In fact, recent literature presents these institutional layers as a central feature of the customary constitution of the Kingdom of Castile (Herzog Reference Herzog2003; Dedieu Reference Dedieu2010). This paper conceptualises the institutional configuration as a complex system in which each component followed its own non-linear dynamics, but where all components had shifting reciprocal connections and affected each other more or less randomly (Morin Reference Morin1977). To some degree, the notion of the political order as an unintended or emergent combination of taxis and cosmos is useful here; an order where the success or failure of institutional solutions is not the result of specific actors' designs, but of unexpected outcomes of games played in several arenas (Hayek Reference Hayek1973). Castoriadis' theoretical contribution fits the idea of a non-teleological sequence of historical development as the intersection of manifold temporalities and causalities (Castoriadis Reference Castoriadis1975, pp. 63-82). We will thus address the institutional effects of paper circulation in Buenos Aires as part of this framework, by taking a micro-level approach, considering the issue from the perspective of political and social actors, and looking at how they responded to economic and military challenges and how their actions reshaped the political economy, creating new conditions that invited new responses.

2. THE FABRIC OF THE FISCAL CRISIS: ATLANTIC TRADE, URBAN INSTITUTIONS, MILITARY SPENDING AND THE SITUADO

Rio de la Plata's economy was based on a huge land supply, limited technological change, but increasing productivity thanks to the growing population. Migration and natural growth pushed up the population of Buenos Aires from almost 38,000 inhabitants in 1778 to no fewer than 77,000 in 1810 (Johnson Reference Johnson1979, pp. 114-116; Reference Johnson2011, pp. 28-31)Footnote 1. External trade entailed the exchange of silver from Upper Peru for European manufacturing goods and slaves, also generating growing exports of local staples. In the later 18th century, this exchange corresponded to an annual average of precious metals exports ranging from 3 to 4 million pesos (or piasters). Moutoukias has calculated that precious metals accounted for between 80 and 90 per cent of the value of exports between 1760 and 1796. Recent estimates show that the export of hides was becoming increasingly important around the turn of the century. The export of precious metals—stored in the port, thanks to the complex transactions that linked the Rio de la Plata to its hinterland, including the mining economies—created the conditions for the sale of this local staple to Atlantic markets. In turn, this had a huge impact on the regional economy; the value of the exported hides exceeded the total value of all other agricultural production (Moutoukias Reference Moutoukias1995, Reference Moutoukias2000; cf. Brown Reference Brown1979; Rosal and Schmit Reference Rosal and Schmit1999; Moraes Reference Moraes2012; Miguez Reference Miguez, Bertrand and Moutoukias2018).

In the final decades of the 18th century, the Atlantic trade of the Rio de la Plata region consisted of different flows: navigation to other Spanish possessions; intercolonial traffic with Brazil and the African coast, which extended to Mozambique and Asian trade in the late 1780s; trade with Europe, via Spanish ports or illegal trade with foreign powers; and, after the mid-1790s, trade with the United States (Cuenca Esteban Reference Cuenca Esteban, Barbier and Kuethe1984b; Cooney Reference Cooney1986; Borucki Reference Borucki2011; Prado Reference Prado2015, Reference Prado2017). The legal framework of this commercial activity was complex and smuggling was common. In 1777, 1 year after the creation of the Viceroyalty, Buenos Aires benefited from the commercial regime that had existed in Cuba since 1765. Limited to subjects of the Crown, this regime had created «free and protected trade between European and American Spaniards», designed as «national» trade on both sides of the Atlantic. This obviously prohibited foreigners from trading directly in American ports, while goods of foreign origin, re-exported from Spain to Spanish America, were overtaxed. The reform of the old monopoly of Cadiz—one of the main pillars of Charles III's economic reforms—therefore expanded and enhanced the mercantilist principle of exclusive colonial trade forbidden to foreign powers (Stein and Stein Reference Stein and Stein2009)Footnote 2. A series of privileges and specific authorisations was added to the general framework created in 1777 to produce an often-contradictory legal construction, which nevertheless preserved this principle. From the 1790s, these privileges and exemptions affected trade with foreign colonies, the slave trade and the temporary permission given to neutral foreign powers—including the Portuguese colonies—to trade in certain parts of Spanish America, when the war with England blocked the Spanish ports (de Studer Reference De Studer1958; Cooney Reference Cooney1989)Footnote 3. Meanwhile, smuggling, which had apparently been contained in the early 1780s, took off again at the end of this decade, with Luso-Brazilians, North Americans and the English being the main players (Cuenca Esteban Reference Cuenca Esteban, Barbier and Kuethe1984b; Moutoukias Reference Moutoukias2000; Prado Reference Prado2015).

One central dimension of the colonial trading system was the collective embeddedness of the group of great merchants in the political order of the city, as well as local structures of royal sovereignty. This institutional grid provided the framework for a range of strategies—including the defence of restrictive trade regulations, smuggling, service or contributions to the Crown and the negotiation of new exemptions, often adopted by the same individuals—whilst ensuring this community of rent-seekers' control over long-distance trade. At the beginning of the 19th century, this process—in which local traders were as active as the Crown—had already been under way for two centuries and these traders had formed a corporation, which collectively enjoyed the privileges negotiated with the Crown. Soon after the city was founded in the late 16th century, Buenos Aires saw the arrival of new settlers. They rapidly became an elite controlling diverse activities, such as the illegal export of silver, the import of slaves, access to land and overseas trade; mostly smuggling, but sometimes benefiting from royal dispensations. This elite also seized control of the organ of municipal administration and local justice, the Cabildo (Gelman Reference Gelman1984, Reference Gelman1985; Moutoukias Reference Moutoukias2000). It then emerged as a de facto corporation, the cuerpo del comercio. By the mid-18th century, corporate control of commercial justice had become the subject of a major conflict among the local governor, the Viceroy of Peru and a merchant faction (Moutoukias Reference Moutoukias, Bertrand, Andújar and Glessner2017). Later, in 1779, the formerly irregular merchants' councils (juntas) developed into a permanent form of representation, and the powerful traders eventually obtained a formal merchants' guild with its own court in 1796: the Consulado (Kraselsky Reference Kraselsky2011). As Adelman has argued, this completed the configuration of the «political property» of the major merchants in the maritime trade of Buenos Aires (Adelman Reference Adelman1999, pp. 29-30).

The Consulado and the city council (Cabildo) thus became the two major corporations that underpinned the political order of the city. Both collected specific duties related to the cost of their respective political and judicial functions and were consequently able to finance political support for the monarchy and its local agents in exchange for new privileges. This support usually took the form of financial assistance in difficult times, for which corporations also mobilised contributions from notable subjects. In a political world of plural hierarchies and fragmented sovereignty, such donations were demanded as part of «service» to the king; as such, they were the counterpoint of «grace, merit and reward» (Dedieu Reference Dedieu2010, Ch. 1; see also Fernández Albaladejo Reference Fernández Albaladejo1992; Grieco Reference Grieco2014).

Despite the commercial growth of the region, the fiscal revenues generated by local economic activity and Atlantic colonial trade failed to provide sufficient resources for running the local administrative and military machinery. Between 1791 and 1805, Potosí's Royal Treasury subsidies funded more than 70 per cent of local military and administrative spending (Halperín Donghi Reference Halperín Donghi1982, Chs. 1 and 2). The situado transfers for Buenos Aires became regular from the 1670s onwards, when Buenos Aires assumed a more pronounced military role. At the time of the Seven Years' War, Governor Cevallos obtained a considerable increase in the situado. Between 1760 and 1764, the Buenos Aires treasury received almost 1 million pesos from the situado. This amount increased to 8.3 million pesos in 1776-1780, with the establishment of the Viceroyalty of Rio de la PlataFootnote 4.

From the early 17th century onwards, silver transfers had given rise to a dense pattern of transactions along the roads between Potosí and Buenos Aires. The garrison officers responsible for the conveyance of the situado advanced coins or silver bars for commercial operations along the roads; traders provided subsistence to soldiers and used their return from the situado in foreign trade; and royal financial officers used the situado funds for their own personal investments. Clearing mechanisms arose between traders and treasuries, embedding the royal finances firmly in local trade. This resulted in a dense network that connected numerous large and small merchants to the military and to political and financial officials (Moutoukias Reference Nicolau1988, Reference Moutoukias1992; Saguier Reference Saguier1989; Grafe and Irigoin Reference Grafe and Irigoin2012, pp. 170-176; Wasserman Reference Wasserman2016).

The Potosí transfers are merely one of many examples of the massive revenue distributions within the Spanish Empire that served to finance both the defence in America and the war efforts in Europe. Irigoin and Grafe's authoritative «negotiated absolutism» model emphasises the bargaining processes between the sovereign power and local political communities. As part of the Crown's efforts to integrate the military finances within a rebalancing of resources between the imperial territories, the increases and decreases in the situado should be understood as a result of such negotiations (Grafe and Irigoin Reference Grafe and Irigoin2006; Marichal Reference Marichal2007, Reference Marichal2008; Irigoin and Grafe Reference Irigoin and Grafe2008, Reference Irigoin, Grafe, Ramos Palencia and Yun Casalilla2012; Marichal and Von Grafenstein Reference Marichal and Von Grafenstein2012).

The numerous fluctuations in the size of the situados were indeed dependent upon the negotiations that took place within the political networks that linked the authorities and colonial elites. However, the decline of the Potosí transfers to Buenos Aires at the beginning of the 19th century seems to have emanated from a more complex combination of factors. The total amount of tax revenue received by the Buenos Aires treasury via the situado reached 13,603 million pesos between 1792 and 1801. In the following decade, at 6,612 million pesos, this figure was more than halved, 1803 and 1806 being the years with the lowest inflows (see Figure 1). Expressed as percentages, this meant that for the first period the situado subsidies represented between 75 and 81 per cent of the fiscal revenues of Buenos Aires; whereas from 1802 to 1811, they shrank to roughly one-third of this amount, before coming to a complete halt in 1810-1811 as a consequence of the political and military developments that resulted in the loss of control over Upper Peru (Halperín Donghi Reference Halperín Donghi1982, Chs. 1 and 2; Amaral Reference Amaral2011, Appendix II). One critical factor in this evolution was the effort required from other treasuries to ensure that the situado was sent to Buenos Aires. Grafe and Irigoin underline the fact that Potosí both sent subsidies to other regions and received transfers from other Upper Peru treasuries (Grafe and Irigoin Reference Grafe and Irigoin2006, p. 266). To estimate the burden that the Buenos Aires situado placed on the available fiscal resources, we need to consider Amaral's figures for Buenos Aires and Klein's figures for the whole of Upper Peru. This burden was enormous. Between 1790 and 1809, an average amount of 911,275 pesos was sent to Buenos Aires each year; that is, 28 per cent of the 3.3 million-peso annual average tax revenue for all the nine treasuries of Upper Peru combined (Klein Reference Klein1994, pp. 67-78; Amaral Reference Amaral2011, Annex 2).

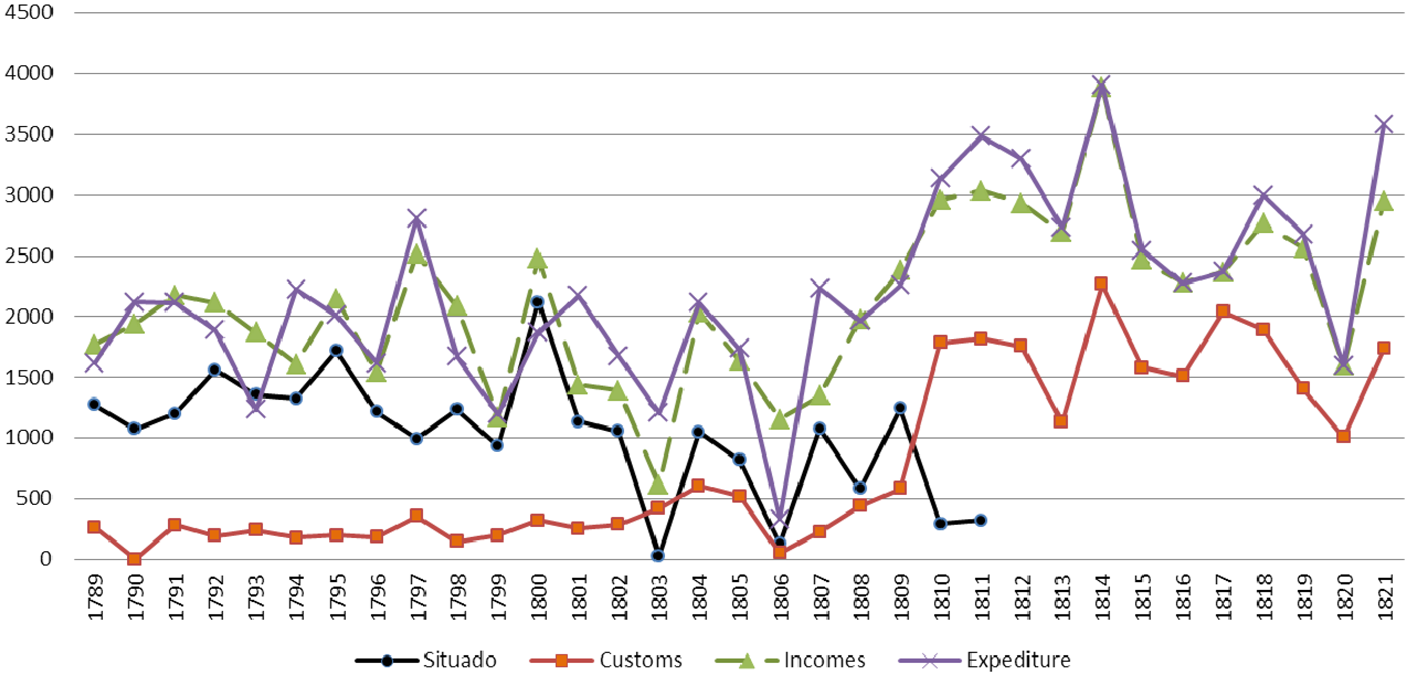

FIGURE 1 INCOME AND EXPENDITURE OF THE TREASURY OF BUENOS AIRES, 1789-1821 × 1,000 PESOS.

Sources: Amaral (Reference Amaral1988, Reference Amaral and Liehr1995, Reference Amaral2011). See also the Appendix.

These revenues included mining production taxes (16 per cent), the tribute from the Indians (a head tax, 24 per cent) and revenues from an array of other minor taxes on trade and monopolies. In these decades, the total tax revenue of Upper Peru continued to rise despite the decline in silver production. Figures published by TePaske and Brown show a gradual decrease in the output of silver, with a marked drop during the years 1801-1805. Klein has demonstrated how this development reduced the revenues from taxes on mining production and trade as part of the total tax revenue of Upper Peru. At the same time, the Indian contribution continued to rise (Klein Reference Klein1994, pp. 71-72, 77; TePaske and Brown Reference Tepaske and Brown2010, pp. 152-154, 186-193, 246), a paradox considered by Tandeter in his fine analysis of the crisis of 1800-1805. He looks at the chain of droughts, famines, epidemics and increased mortality that followed one another in parallel with the increase in fiscal income from the tributes. In the first years of the 19th century, the incomes of the treasuries in Upper Peru continued to rise, mainly because of the growing contribution of the Indian communities in a context of deep crisis. This brought numerous conflicts and social tensions to the major cities of Upper Peru (Tandeter Reference Tándeter1991, pp. 66-69). It can be assumed that this led to a redefinition of priorities in short-term negotiations about shipments to other offices, including Buenos Aires, before the loss of control over Bolivia resulted in the definitive halt of the situado in 1811.

Between 1792 and 1801, in order to cover current civil and military spending, Buenos Aires needed total revenues of between 16.7 and 18 million pesos, most of which came from the situado subsidies and just 2.3 million from taxes on trade. Occasional imbalances, such as that in 1794, were compensated for with transfers between the different accounts of the royal treasury. These transfers entailed the temporary use of the funds, over which the royal officers had custody but not the right to spend freely, anticipating the future arrival of the situado. This was by far the most important mechanism for offsetting imbalances in local accounts. Between 1797 and 1802, there were also loans and donations from corporations and individuals, but they were transferred to Spain, and amounted to no more than 20 per cent of the transfers between accounts in the same period (Amaral Reference Amaral2011, Reference Amaral, Bertrand and Moutoukias2018; Grieco Reference Grieco2014; see also the Appendix).

Nevertheless, this means that the financial system was already weak prior to the increasing military mobilisations after 1806 and the rise of political tensions and conflicts. With the crisis and collapse of the Spanish monarchy, war financing was to play a fundamental role in institutional and economic changes in the Río de la Plata region, starting immediately with the mobilisation of the urban militia during the English invasions of 1806-1807. The creation of new military units between 1807 and 1809—rather politicised militias, which also intervened in internal conflicts—cost 2.8 million pesos in those years, compared with the 1.7 million pesos of the annual budget 5 years previously. This rising trend was maintained by the further professionalisation of the troops and the creation of new armies. According to estimates by Halperín Donghi, military expenditure increased sharply between 1806 and 1815; it totalled 4.6 million pesos between 1801 and 1805, rising by 70 per cent to 7.9 million for the years 1806-1810, and reaching 8 million in 1811-1815. Considering the local net expenditure of Buenos Aires—that is, without the transfers to Spain and other treasuries and frontier areas—military expenditure accounted for 53 per cent in 1801-1805, 73 per cent in 1806-1810 and 67 per cent in 1811-1815. Henceforth, war finances were the main priority for the Buenos Aires authorities (Halperín Reference Halperín Donghi1982, pp. 77-85, 135, 142-175, 210-259).

Such increases were in line with the similar processes of militarisation in other parts of the former Spanish Empire (Thibaud Reference Thibaud2003; Sánchez Santiro Reference Sánchez Santiró2016, pp. 136, 150). Recent research shows that militarisation played a central role, bringing new dynamics of political participation, the rallying of popular support and the rise of new principles of legitimacy for the Rio de la Plata (Gonzalez Bernaldo Reference Gonzalez Bernaldo1990; Adelman Reference Adelman2010; Bragoni and Mata de Lopez Reference Bragoni and Mata De López2010). Ravinovich has emphasised the surprising ability of the belligerent sovereign powers to maintain a high degree of military mobilisation, estimating rates of male participation in the army that were even higher than in revolutionary France (Ravinovich Reference Ravinovich2012, p. 41).

The year 1806 marked the beginning of a 10-year period of financial difficulties, military contingencies and political instability. The expansion of military spending plunged the fragile Buenos Aires treasury into fiscal crisis. Figure 1 summarises the situation between 1789 and 1821. The revenues included the situado and contributions from urban corporations and individuals, as well as the forced loans after 1813. Expenditure comprised transfers to other accounts and reimbursements of the contributions (see the Appendix). Figure 1 also shows the share in income from the situado and customs, although other revenues are not specified (see Figure 2).

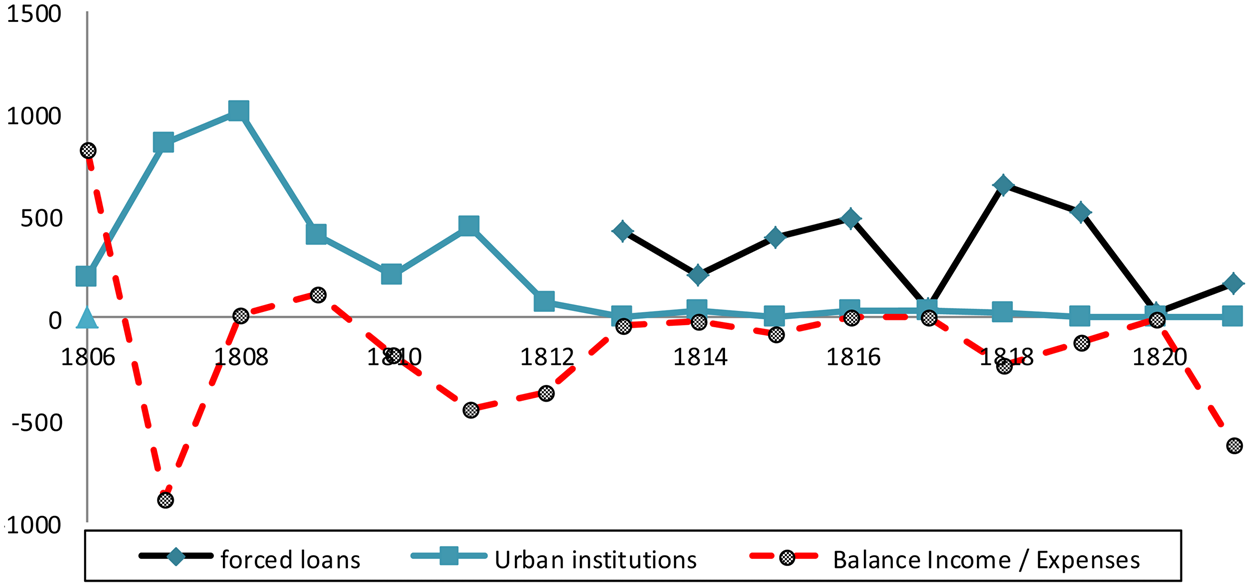

FIGURE 2 CONTRIBUTION OF URBAN INSTITUTIONS, FORCED LOANS AND DEFICIT, 1806-1821 (×000 PESOS).

Sources: Amaral (Reference Amaral1988, Reference Amaral and Liehr1995, Reference Amaral2011). See also the Appendix.

Until the beginning of the 19th century, the tax system seems to have responded well to the financial needs of the capital of the Viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata. As we saw above, the system was based on the redistribution of fiscal surpluses from Upper Peru that imposed a heavy burden on the royal treasuries in these regions. From 1802 onwards, with the situado decreasing, this tax system fell under increasing strain and the transfers between different accounts were no longer sufficient to overcome the imbalances. The fact that there was a decline in silver shipments to Spain and others treasuries near Buenos Aires provided some relief. Meanwhile, revenues from customs fell sharply in 1806, because of the British attacks and the disruption of trade at sea (O'Rourke Reference O'rourke2006). It was not until 1808-1809 that revenue levels were back at the 1803-1804 levels, yet expenditure continued to rise. With the start of militarisation in 1806-1807, a fiscal crisis was imminent; spending would exceed revenues by an annual average of 10 per cent until 1814.

Between 1806 and 1812, the local authorities resorted to the traditional repertoire of emergency finances: negotiating donations, contributions and loans from the Cabildo, the Consulado and individuals within the institutional universe depicted above. In Figure 2, «urban institutions» reflect the substantial input of both urban corporations, which exceeded customs revenue until 1809. Having started in 1806, donations and contributions from individuals—mostly forced, but some voluntary—were increasingly required after 1810. These contributions were still conceived as part of the traditional duty of personal service to the sovereign in times of emergency and did not include any specific capital repayment clause. Until very recently, some contributors could expect an institutional reward or rent for their contribution and, in the case of Cabildo and Consulado loans, the debt was recognised although rarely fully repaid (Amaral Reference Amaral2011, Reference Amaral, Bertrand and Moutoukias2018, Grieco Reference Grieco2014). During the period between 1806 and 1812, the contributions made by the Cabildo and the Consulado from their own funds represented 79 per cent of the total input from «urban institutions», the rest being donations from individuals made through these institutions and transfers from other accounts (the Monopoly of Tobacco, church levies (claveria de diezmo), and so forth (see the Appendix for sources and further details).

Spurred on by the fiscal crisis, in 1809 the authorities suspended the above-mentioned restrictions on foreign commerce, authorising foreign traders to operate in Buenos Aires. The opening of the Atlantic trade—partially at first, and gradually more extensively—resulted in substantially higher customs revenues (see also Figure 1). For another 2 to 3 years, «urban institutions» and wealthy individuals helped to counterbalance the deficit created by military spending but, in parallel with the gradual building of the new republican order, their input dwindled and eventually disappeared. The public finances inherited from the Old Colonial Regime thus reached, and even overran, their limit and subsequent revolutionary regimes were confronted with the need to find new mechanisms.

3. POLITICAL VOLATILITY AND FINANCIAL INNOVATION: FORCED LOANS

The new political context, the higher degree of militarisation and the unprecedented fiscal crisis created room for innovation. From the moment that British troops attacked Buenos Aires, political instability became a central element of the city's institutional life (Halperin Donghi Reference Halperín Donghi1971b). Sobremonte, the viceroy who had been appointed in 1804, fled the city when the British occupied Buenos Aires. After a second attempt at military occupation by the British, the urban institutions thereupon named Liniers, a Navy officer, as the new viceroy; he was confirmed in office by the Spanish Crown in 1807. This reflects the extreme political volatility and, at the same time, the role of the Consulado and the Cabildo in the local political order of the monarchy. Liniers was one of the two military leaders to emerge from these events, alongside his rival Alzaga, the previous prior (head and judge) of the merchant guild and mayor of the city council (Amaral and Moutoukias Reference Amaral and Moutoukias2012). The former was subsequently replaced by Viceroy Cisneros in 1809, put in place by the Spanish Junta Central that had resisted the Napoleonic occupation. Cisneros, in turn, was deposed during the May Revolution of 1810 in Buenos Aires. A de facto republican period followed, characterised by new forms of political competition and instability, with local sovereign governments operating in the emergent republican structure. In 1816, the United Provinces of South America declared independence from Spain, and between 1814 and 1820 the two successive Constituent Assemblies appointed «Supreme Directors» to govern the United Provinces of the Rio de la Plata (Halperin Donghi Reference Halperín Donghi1971b, Ternavasio Reference Ternavasio2007).

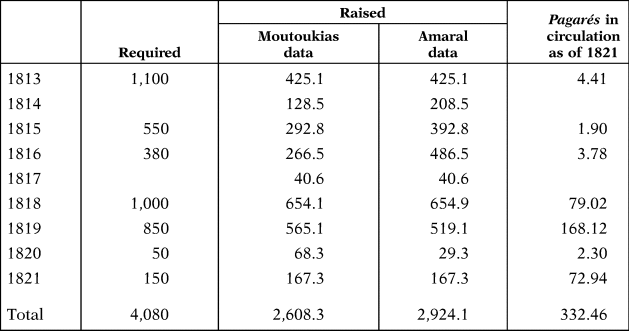

These successive unstable governments had to ensure the transfer of funds for armies intervening in different theatres. To raise funds, until 1812, they resorted to the «traditional» financial mechanisms mentioned above. In July 1813, however, the first Constituent Assembly «… ordained that the capitalists of all categories furnish a loan of 500 thousand pesos …» and decided on new conditions regarding forced loansFootnote 5. Between 1813 and 1821, sixteen loans were demanded for a total amount of 4 million pesos, of which more than 2.5 million was actually raised. Table 1 shows the amounts demanded and sums actually received by the government. In order to produce these data, we compared the figures obtained by Moutoukias from the balance sheets of the actual forced loans between 1820 and 1821 and the data registered in the Buenos Aires treasury, as published by Amaral (see the Appendix).

TABLE 1 FORCED LOANS 1813-1821: AMOUNTS REQUIRED AND ACTUALLY RAISED (PESOS ×000)

Sources: AGN, Sala X, legajos 2-9-7, 9-4-2, 9-4-3, 11-1-1, 11-5-1 and 22-2-7; RORA 1879. For Amaral data, see the Appendix.

In return for the loans, individuals received promissory notes (pagarés) from the authorities. Table 1 also lists the pagarés that were still extant in 1821, according to the year contracted. The mechanisms of these notes varied with the fortunes of war and political stability, but had the following central features:

• they were negotiable by endorsement.

• They could be used to pay all or part, usually half, of the debts that the holder (or the beneficiary of an endorsement) had accumulated at the Customs Office, caused by unpaid customs duties.

• After a minimum period that varied in accordance with military fortunes, usually 6 months to a year, the Customs Office could also redeem government bonds drawing up bills of exchange, being the drawees debtors of the same Customs.

• They received an interest rate of 3.8 or 12 per cent—occasionally even 15 per cent—according to the terms of redemption and military circumstances (Amaral Reference Amaral1981; Moutoukias Reference Moutoukias, Bertrand and Moutoukias2018).

The government pagarés were thus exclusively redeemed by using them as a means of payment of the holder's tax debts at the Customs Office. Even if the repayment of paper by the Buenos Aires treasury was anticipated in the terms and conditions of forced loans, the delay was never defined but conditioned to the evolution of war. If the loanholder (the original owner or the beneficiary of an endorsement) immediately introduced the loan to pay customs duties, the title was accepted without a premium. However, if the loanholder waited for the minimum period stipulated in the loan, usually 3 months, the title benefited from 3 per cent interest. This could increase as long as the owner kept his title or promissory note before submission to the Customs Office. Between 1814 and 1816, the years of greatest political and military tension, the regulations changed temporarily, and the end-term of presentation to the Customs Office was fixed at «six months after the end of the war», or made subject to future, still unspecified, decrees. Not all forced loans entailed promissory notes that could be transferred by endorsement. Yet, such exceptional regulations did not modify the conditions of previous loans, nor did they create a precedent for later ones (Amaral Reference Amaral1981, pp. 42-44)Footnote 6.

The result was a complex and confusing patchwork of debts that were increasingly negotiated and circulated among individuals. The government tried to consolidate its debt in 1817, making the circulation of paper even more widespread. A decree issued by the Supreme Director Pueyrredón in March stipulated that all debts against the state—«all claims that weigh on the state», whatever their origin—could be replaced by a new promissory note. Again, this was negotiable by endorsement and the state accepted it as an equivalent to coins, but new titles could now be used to pay only half of the taxes on maritime and land trade that holders owed to the Customs Office. The rest was to be paid in coins. Thus, while redeeming a portion of the old debt, this consolidation encouraged the entry of coins into the treasury. Detailed official estimates show that the measure succeeded in reducing the confusion. By the end of 1817, the state treasuries had covered all of the notes presented, whereas the available income from customs covered the titles that were still in circulationFootnote 7.

To what degree were these loans «forced» or «voluntary»? History shows that few countries have been able to raise loans freely on the financial market, either because the market lacked reliable intermediaries or because financiers did not trust the government's fiscal management. Even highly advanced economies, such as those of Venice and Florence, relied on forced loans for centuries ('t Hart, Brandon and Torres Sánchez 2018). The contrast is not simply one of «forced» vs. «voluntary», however; in times of crisis, even «voluntary loans» were of a forced nature, since rich officers might feel obliged to grant funds to the government (Van der Heijden Reference Van Der Heijden2006). The sociology of organisations also shows how coercion depends upon negotiation, since power relations are dependent upon the latter (Crozier and Friedberg Reference Crozier and Friedberg1977). Forced loans were thus partly a matter of negotiation; for example, the rate of interest on forced loans needed to reflect market values to some extent. Scholars have also emphasised the high degree of consent that characterised the extraordinary contributions to the previous colonial ancien régime, often in an exchange of revenues for privileges or rewards that strengthened the social and economic position of local elites. The trade consulate of Buenos Aires had emerged as a result of such bargaining between forced levies and the granting of privileges (Kraselsky Reference Kraselsky2011; Grafe and Irigoin Reference Grafe and Irigoin2012; Grieco Reference Grieco2014).

Such were the dynamics of government loans when the military mobilisation started in 1806 and culminated in the revolution of 1810. The forced loans were dependent upon compromise for their implementation. Composing the list of lenders was undoubtedly a political act; ad hoc committees including representatives of the Cabildo and the Consulado usually drew up the list. In theory, the amounts were in proportion to the lenders' wealth and relied on a register of «capitalists» (large and small traders, craftsmen and any other head of household reporting economic activity) made in 1812 for fiscal purposes (Nicolau Reference Nicolau1988, Chs. II and III). There were other procedures, too; for example, the 200,000 peso loan imposed on Spanish and European citizens in 1816 was regulated by commissioners of the lenders themselvesFootnote 8. Finally, the alcaldes de barrio, a kind of judge with police powers, communicated the amount required to the lender and handed over the noticeFootnote 9. The personal networks of the most powerful merchants obviously gave them access to such management committees, which facilitated personal gains (Nicolau Reference Nicolau1988, p. 45). Yet, the majority of lenders did not belong to this category, as will be shown below.

4. DEBT TITLES AND BILLS OF EXCHANGE

The pagarés boosted the emergence of a local financial market and permitted new forms of brokerage and agency, and the number of traded bonds increased. Bills of exchange already featured prominently in that market and were used by merchants and officials from the Royal Treasury alike (Moutoukias Reference Moutoukias1992; Gelman Reference Gelman1996). In 1808-1809, interim Viceroy Liniers ordered officeholders to draw bills of exchange upon major debtors as drawees at a time of increased military spending and raising public debtFootnote 10. Later, between 1816 and 1820, these orders of payment represented—according to figures from Tulio Halperín—14 per cent of the gross revenues of the Buenos Aires treasury. Bills of exchange also played a central role in financing local supplies to armies operating in remote districts from Buenos Aires (Halperín Donghi Reference Halperín Donghi1982, Ch. 2). The liberalisation of foreign trade resulted in higher revenues from customs, which enabled the Customs Office to appear as the drawee of bills for which the drawer was the intendant of the army and the taker or payee was a merchant residing in Buenos Aires or a city close to an army, such as Tucuman or MendozaFootnote 11. According to Moutoukias, those latter merchants made advances to the army in goods and services, in exchange for which they received from the army intendant a bill drawn up at the Customs Office (the drawee), payable on demand in Buenos Aires. They could then endorse the bill of exchange to a merchant of that city, who thus became the taker or payee. Much more frequent was the operation in the opposite direction; at the request of the government, a large trader from Buenos Aires ordered one of his agents to advance goods or services to the army, creating in his accounts a credit in favour of the said agent for their usual operations, but reimbursed with a bill of exchange also payable on demand in Buenos Aires. The drawer, again, was the intendant of the army, the drawee the Customs Office, and the payee the merchant who had given order to his agent. For its part, the drawee—the Customs Office—only agreed to pay the bill by deducting the unpaid duties of the holder (or the beneficiary of a new endorsement) (Moutoukias Reference Moutoukias, Bertrand and Moutoukias2018, pp. 183-185, 191-193). According to Tulio Halperín, local resources financed 75 per cent of the expenditure of the army of the North in 1810-1811, yet advances by local traders were reimbursed by bills of exchange paid in Buenos Aires. The latter played an increasingly important role in the following years (Halperín Donghi Reference Halperín Donghi1971a, pp. 96-99). Bragoni has documented similar developments for the army of «Los Andes» (Bragoni Reference Bragoni2017). Between 1814 and 1819, the use of bills of exchange therefore became widespread, in order to transfer funds or pay for the supplies provided by local merchants (Halperín Donghi Reference Halperín Donghi1982, pp. 102-104, 123, 125, 130, 133).

Such transactions involved merchants and agents with various profiles, many of whom were connected to the networks of the most powerful merchants in the late colonial period. The new forced loans of 1813 enhanced their position in the political economy of Buenos Aires, because takers (payees) of bills of exchange could endorse them by paying part of the forced loan that the government had imposed. As we shall see below, these represented 16 per cent of all forced loans actually collected between 1813 and 1817, but only a limited group of merchants used them in this way. They formed part of the main kinship groups of the local Indiana (creole) elite and prominent members of the Consulado and the Cabildo (Tjarks Reference Tjarks1962; Socolow Reference Socolow1978; Moutoukias Reference Moutoukias2015).

5. ASYMMETRIC CIRCULATION OF PAPER BILLS

The new system of forced loans after 1813 can be summarised as the imposition of a loan to the sovereign authorities provided in coins but amortised by these authorities by deducting debts in customs duties. As we saw above, this principle was expanded to other state debts, such as those incurred in supplying the army; no evidence has been found for the treasury repaying pagarés directly in money. In certain cases, the treasury of Buenos Aires paid pagarés and bills of exchange grouped by endorsement with an order to the Customs Office to draw bills of exchange upon its different debtorsFootnote 12. In general, the system of amortising the forced loans by deducting customs debts seemed to have worked well, as shown in Table 1. In 1821, the still-unredeemed pagarés accounted for 13 per cent of the loans raised by the state since 1813Footnote 13. If we take into account only loans raised between 1813 and 1818, the percentage of unamortised paper in 1821 drops to 5 per cent.

The proper functioning of this mechanism enhanced an asymmetry in the financial market; namely, the inequality that existed between agents whose economic enterprises generated duties to be paid towards customs duties, and those whose activities did not generate such duties. Moreover, traders who received bills of exchange in return for equipping and furnishing the army could use these bonds to fulfil their lending obligations. These bills of exchange represented 16 per cent of all forced loans that were actually collected between 1813 and 1817, but they were only used by a limited group. During these years, successive forced loans led to the input of 1,153,500 pesos, 16 per cent of which was paid for by endorsed bills of exchange. Spanish-American (or creole) traders used these bills to pay 21 per cent of the amount stipulated to lend to the government, whilst this percentage was 15 per cent for «European» tradersFootnote 14. The names of the payees on the endorsed bills appear on preserved balance sheets of forced loans, which enable us to analyse who profited most from these arrangements. Of the sixty-seven identified creditors, twelve names frequently occur on the lists from between 1814 and 1817; names such as Achaval, Aguirre (father and son), Anchorena, Arana, Lezica, Riglos, Sarratea and others. All were descendants of Spanish migrants, second- or third-generation migrants born in Buenos Aires, and their fortunes were based on large-scale trade, the land, political connections and municipal offices, and participation in militias or other public and honorific functions. For example, Juan Pedro de Aguirre, a landowner and one of the most important merchants, used bills of exchange to cover more than half of the considerable sum of 48,750 pesos that he needed to pay in 1816Footnote 15. In other words, in response to the coercive loans that compelled agents to obtain increasingly scarce metallic currency, some lenders could use a substitute that was readily available due to the nature of their activities. Those lenders who were not involved in military enterprises or Customs found themselves in exactly the opposite position.

This disparity was the obvious result of the diverse social standing of those to whom the forced-loan levies were addressed. All social classes had to pay, ranging from artisans with small workshops paying 50 pesos, to large lenders such as Aguirre, mentioned above, who provided almost 50,000 pesos. In the six lists of forced loans that have survived, showing total amounts of more than 290,000 pesos—corresponding to the levies raised in 1813, 1815 and 1818—about 40 per cent of the sums was provided by about 800 lenders, in amounts ranging from 50 to 150 pesos. Allowing for the fact that even among those who paid over 150 pesos, a substantial minority would not profit from the fortuitous advantages of forced loans either, we arrive at the very rough estimation that around 60 per cent of the lenders would never enjoy the advantages of the other, large-scale lendersFootnote 16.

The protests against the forced loans came from this heterogeneous group with no or few links to the Customs Office. The supplicants requesting the reduction or simple cancellation of loans included farmers, artisans, shopkeepers, drivers, land transport contractors, middle-ranking traders and, occasionally, influential merchants. Most complained about the complicated nature of the loans and the burden of other contributions; all of them claimed that they could never use the titles at the Customs Office; numerous others referred to a shortage of liquidity and a lack of hard currency; and widows and wives claimed they were too poor to payFootnote 17.

In fact, public loanholders who had no dealings with taxes on maritime and inland trade had two options: either to wait until the end of the war, or to endorse and sell, which was the only real option for most. The authorities themselves raised the issue publicly as early as 1814, highlighting in particular the problem of very small holders. In 1814 and 1815, they granted the possibility of using the 50 and 100 pesos pagares to acquire subsistence in customs warehousesFootnote 18. According to official estimates, this situation caused a decline in their value, with a depreciation of 40 to 50 per cent in 1817, which particularly hurt the smallholders who needed to sell them in the short termFootnote 19. Some evidence on the price formation in these transactions reveals the obvious inequality engendered in this highly volatile financial market. A certain trader, Gaspar de Santa Coloma, and his heir in the commercial house could buy, for example, 252 endorsed promissory notes between 1813 and 1817, amounting to almost 24,000 pesos. He took them at various discounts, ranging from 25 to 62 per cent below the issue value, with an average of 36 per cent. The lenders were often limited to the prices being offered, whilst those who purchased the bonds multiplied their options. Among the latter, members of the former Indiana oligarchy who were involved in supplying armies stood out for creating more and more options for obtaining such bonds at a low price (Moutoukias Reference Moutoukias, Bertrand and Moutoukias2018)Footnote 20. As such, the innovative devices did solve a pressing problem for the local authorities in a flexible way, but they reinforced a new kind of social asymmetry. At the same time, the loans linked present spending to future revenues from customs, thereby creating a kind of «funded» debt, that is, debt guaranteed upon specific future revenues.

6. PUBLIC SPENDING AND THE INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK OF ATLANTIC TRADE

The authorities' awareness of this link between current expenditure and future income from customs is also evident from public documents. In 1817, the Secretary of Finance (Secretario de Hacienda) calculated that the import duties that the government expected to receive would be more than sufficient to amortise the pagarés of the forced loans in circulation. This enhanced the transparency of the whole fiscal operation and created trust in the forced loans, due to the secure funding of the future debt charges (cf. Amaral Reference Amaral, Bertrand and Moutoukias2018, ’t Hart et al. Reference ’T Hart, Brandon and Torres Sánchez2018)Footnote 21.

Customs revenues increased after the region opened up to foreign traders in 1809, which increased the trade flows to be taxed. Indeed, foreign trade had been on the rise since the 1790s, despite the disruption caused by war. Between 1791 and 1796, the port of Buenos Aires received sixty-five ships each year, on average; in the period between 1815 and 1819, this doubled to an average of 136 vessels. Before 1809, the city's Atlantic trade had consisted of a mix of legal shipping and more or less tolerated smuggling, the latter mainly with Brazil and Portuguese colonies in Africa. By 1808, however, British and North American ships were arriving in remarkable numbers, facilitated by the revolutionary events in the Atlantic and the transfer of the Portuguese Court to Brazil by the British Navy. Between 1815 and 1819, most vessels were of British origin (51 per cent), followed by North American (15 per cent), whilst the remainder consisted of Portuguese and French ships and vessels from the Rio de la Plata itself (Tjarks and Vidaurreta Reference Tjarks and Vidaurreta1962; Kroeber Reference Kroeber1967; Brown Reference Brown1979; Silva Reference Silva1993; Moutoukias Reference Moutoukias1995; Rosal and Schmit Reference Rosal and Schmit1999).

The city's opening up to Atlantic trade in 1809 thus entailed the legalisation and taxation of a trade that would otherwise have eluded tax due to smuggling practices. Scholars have interpreted the measures that led to this commercial freedom in different ways. According to the nation-building narrative inherited from the 19th century, the prosperous local elite imposed free trade out of a desire for emancipation, with claims embedded in the Enlightenment (Mitre [1857] Reference Mitre1889). Others view the measures as part of the wider transformation of political culture in the Atlantic world (Adelman Reference Adelman1999; Cardoso Reference Cardoso2009), whereas neo-institutionalist approaches stress how the authorities chose to build a more efficient institutional environment that would allow the economic growth of Rio de la Plata to outstrip that of other regions of Latin America (Coatsworth Reference Coatsworth, Bernecker and Tobler1993; Haber Reference Haber and Haber1997; Mahoney Reference Mahoney2003). Whatever their differences, all share, to some degree, a teleological vision.

Yet, this interaction between forced loans and the opening up to foreign trade is in fact a typical example of unintended order, as mentioned in the Introduction. Imposed in November 1809 by Cisneros, the last viceroy before the May Revolution of 1810, the main aim of free trade was to restore the balance of local finances and to re-establish the silver shipments to Spain, which were important to the authorities resisting the Napoleonic occupation there. Initially, in fact, the measure was only a limited instruction to customs officers to allow British ships anchored in the Rio de la Plata to sell their cargo for a limited periodFootnote 22. Yet this triggered a path-dependent process, locked in by the forced loans regulations. During the intensified political conflicts in Buenos Aires, Viceroy Liniers—Cisneros' predecessor—and the chief of the Cabildo, Martin de Alzaga, vehemently exploited smuggling and trade-opening issues as part of their political game, accusing each other of maladministration. Later, in 1809, Cisneros helped the Spanish in Europe by responding to the request for commercial freedom for English merchants as an «Allied Power» against France (Tjarks Reference Tjarks1962).

The debate on the freedom of Atlantic commerce was a major issue in the political arena, but not the only one; another issue was the role of the Consulado with its territorial courts, through which it exercised jurisdiction and levied taxes (Kraselsky Reference Kraselsky2011; Kuethe and Adrien Reference Kuethe and Andrien2014, p. 353). Some factions preferred an institutional alternative in which the freedom of trade coexisted with such corporate mechanisms, thus enabling the Consulados to maintain their crucial role in the political economy and to capture a larger share of the tax benefits generated by the increase in Atlantic trade, from which they could finance the continuation of their previous substantial contributions and donations. Earlier examples of the financing of river privateers by the Buenos Aires guild and of military expeditions in America by the Consulado of Cadiz show that such an alternative was plausible (Tjarks Reference Tjarks1962, Ch. XI; Malamud Rikles Reference Malamud Rikles2007). However, the role of the Consulado was eroded after the May Revolution of 1810 as the new and complicated forced loan arrangements stimulated local bureaucracies to engage in more direct relationships with individual bondholders, rather than with large corporations.

The dismantling of the most important regulations of colonial trade took place in 1812 and 1813. In 1812, the opening of the port became permanent and the government eliminated the mediation of local merchants as a body by allowing foreigners to trade «in the general interest of the State»Footnote 23. In the following year, however, the Constituent Assembly restored the position of the Consulado and again obliged foreign traders to use the intermediation of a Consulado member. It was the local government that took the step of asking the Assembly to reconsider this measure, arguing that restricting the freedom of foreign traders would reduce import duty revenues and consequently undermine the region's capacity to finance the war. The Assembly accepted these arguments (Nicolau Reference Nicolau1988, pp. 50-51). Thereafter, new regulations on the export of local products and precious metals were introduced, as well as new import procedures. The authorities kept returning to the argument that the war needed to be financed and the forced loans servicedFootnote 24. This resulted in much greater flexibility and efficiency for local government than had previously been the case, including a higher degree of transparency in state finances (O'Brien Reference O'brien, Yun-Casalilla, O'Brien and Comin Comin2012).

7. UNINTENDED INSTITUTIONAL CHANGE

Let us now return to the claims made in the Introduction. The notion of a «complex system» conceptualises institutional change as a plurality of economic and political processes that follow their own dynamics while affecting each other. This approach challenges the Irigoin-Grafe model of the «Spanish path to the nation state». As we have seen, their arguments identify institutional change with the political fragmentation caused by the internalisation of external conflict, the Napoleonic occupation of Spain and the consequent collapse of the Crown's arbitrating capacity. Instead, we emphasised the background to this institutional change that started before the Napoleonic period, the dismantling of the legal regime of trade controlled by Spain, the weakening of the two pillars of local political order under Spanish rule and the emergence of a financial market. These developments cannot be identified with political fragmentation alone, as Irigoin and Grafa suggested. The external conflict was obviously a factor in our argument, but we followed these institutional changes by analysing where they took place—the internal dynamics of the Buenos Aires political community—and how these dynamics interacted with other processes in different parts of this complex system, the viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata and the Spanish Empire. This allowed us to track the path-dependent effects of innovation in public financial management.

The fall in the Potosí situado was mainly caused by local factors but represented an important external shock for the treasury of Buenos Aires that affected the political arena. At the other extreme, a minor episode in the European wars—the attempted occupation of Buenos Aires by British troops in 1806 and 1807—drove up the cost of the political and military conflicts, transforming this shock into a fiscal crisis. Initially intended to help the Spanish authorities who resisted the Napoleonic occupation and introduced by the last viceroy through political contingency, the opening up to foreign trade in 1809 sparked a rise in customs revenues before its adoption as part of the republican order. This, in turn, allowed forced loans to be backed up with coupons that were accepted as payment for customs duties, thereby postponing the direct burden of military spending, and later enabling this to be compensated again through future earnings from customs duties. In turn, the forced loan mechanism reinforced the growth of legal Atlantic trade. Introduced by the Constituent Assembly of 1813, the loans were also imposed on a new, much broader kind of public, which, although it did not yet consist of an imagined assembly of citizens, was no longer composed of privileged corporations within the political community of the city (Amaral and Moutoukias Reference Amaral and Moutoukias2008, Reference Amaral and Moutoukias2012; Amaral Reference Amaral, Bertrand and Moutoukias2018).

Forced-lending procedures developed in the context of existing financial institutions and practices. The resources available within the institutional culture of the Hispanic world included a range of mechanisms, some of which resembled forced lending. We have seen that before 1810, particularly after the English invasions, individuals were called upon to provide loans and donations, which were more or less forced or voluntary. These individuals contributed as members of a corporation or institution that conferred status, such as the Church, militias, a city council or mercantile corporation, and in the case of loans, there was no explicit remission clause. It was the Cabildo and Consulado which deposited individuals' contributions into the Buenos Aires treasury, and the total amount was also relatively small compared with the contributions the corporations made using their own funds, as we have seen. Yet, after 1813, the government directly managed public loans and accounted for almost all extraordinary fiscal inputs. Furthermore, the possibility of using debt bonds or pagarés as a monetary substitute to pay customs duties might resemble mechanisms of the former Spanish juros or other financial instruments yielding rents, but in this case, it functioned precisely as the rent that was paid on a city's tax revenues (Dedieu Reference Dedieu, Bertrand and Moutoukias2018). The innovative pagarés of Buenos Aires recognised the capital provided with specific repayment clauses, and agents negotiated their value within the new, emerging secondary market. The forced lenders obtained from the customs revenue neither the remission of capital nor the payment of interest; they could use the pagarés to, once again, reimburse their own debts.

Beyond providing an inventory of continuity and rupture this contribution has sought to highlight the path-dependent nature of the effects of this innovation, regardless of the importance of the novelty. It was neither political fragmentation nor the internalisation of external conflicts that made these path-dependent effects irreversible, but the link between current spending permitted by forced loans and future revenues from trade tax, as well as paper circulation mechanisms.

The pagarés of Buenos Aires cannot be considered an investment opportunity, since the government did not issue these bonds for investors who were free to decide whether to buy them or not, depending on the yield of the public debt. The actors were forced to lend, although their resistance could have caused the forced loans to fail. The fact that the mechanisms worked shows that the loans were based on at least a minimal degree of political consent. This consent was furthered because the process took place in parallel to an expansion of the role of large traders in the financing of armies; traders who could use bills of exchange to pay for forced loans and simultaneously benefit from the purchase of promissory notes below their face value, to be used to pay their tax debts. Former creole merchant elites continued to finance the military and thus engaged in a novel form of political relationship with the new sovereign power, establishing permanent ties. The extended use of bills of exchange, which were needed for the provisioning of the military, and the increased interactions in the secondary market for the bonds for the forced loans, stimulated the development of an incipient financial market.

Data from Figures 1 and 2 reveal the options that were available to the authorities. The contributions from urban corporations had played an essential role in keeping the deficits of the city's early modern finances within manageable limits. With the erosion of both the situado and financial aid from the town hall and the merchants' guild, forced loans became indispensable. The obvious question is why the actors in question, particularly former members of the Consulado merchants' guild, accepted the dissolution of what had previously been exclusive privileges. Whilst the political context offers part of the explanation, the scarcity of metallic currency led to the lengthening of tax payment deadlines and increased the debts of traders; debts that needed to be repaid in one way or another. For the new sovereign power, forced loans constituted a flexible response to temporary shortages of money, whilst former colonial elites regarded the loan mechanisms as an acceptable way to preserve their position in the new political economy. The new order was thereby locked into the opening up of Atlantic free trade, which had the unintended consequence of weakening the old corporate order, in a complex form of institutional change.

APPENDIX: SOURCES FOR FIGURES 1 AND 2

Figures 1 and 2 aim to highlight the role played by the circulation of bonds (pagarés and bills of exchange) during the institutional changes of 1813-1820. The problem of the debt itself is a related topic, but one that is subordinate to these objectives. The graphs put the loans granted by individuals to the sovereign power of Buenos Aires from 1813 onwards in historical context. Furthermore, they show how financial support for the sovereign power changed from being a configuration of ancien régime actors and institutions to a republican order, a transition that was stimulated by the circulation of these bonds. The graphs reveal the financial constraints faced by various local governments and the nature of the resources they tried to mobilise.

Income and Expenditure of the Royal Treasury of Buenos Aires, 1789-1821

Four authors have published statistics on the finances of the Rio de la Plata: Klein (Reference Klein1973), Amaral (Reference Amaral1988, Reference Amaral and Liehr1995, Reference Amaral2011), Halperín Donghi (Reference Halperín Donghi1982) and TePaske and Klein (Reference Tepaske and Klein1982). Halperín Donghi presents the totals of revenue and expenditure in terms of 5-year periods, whereas TePaske and Klein stop in 1806/1808. Only Amaral's data enable us to reconstruct an annual series from 1790 to 1821. In addition, the author identified inter-account transfers to finance temporary deficits that are of major significance to the interpretation of the series.

The inter-account transfer mechanisms that Amaral discovered gave rise to a debate that ultimately confirmed the validity of his data. His analysis is based on contemporary texts describing the system and sources showing the actual practices of financial officials. The various types of income and expenditure were organised into three categories of accounts (Ramos): (a) the accounts of the royal budget (Ramos de Real Hacienda en común), which comprised the taxes and levies needed for all current and extraordinary administrative and military expenditure; (b) the accounts of the royal finances (Ramos particulares de Real Hacienda), containing the taxes and levies that belonged to the king and were destined for specific expenses, with funds that could not be disposed of freely, at least not in theory and (c) the specific accounts of other organisations and private persons (Ramos particulares ajenos), whose funds did not belong to the royal finances at all, such as the Montepíos, which was intended to support soldiers, retired members of the administration or their widows or funds that were destined to be transferred or returned to their rightful owners, such as the individual deposits in the bienes de difuntos, the property of estates with heirs in Spain.

The first category, Ramos (a), the accounts that maintained administrative and military structures, was by far the most important. Deficits in these accounts were financed by making temporary transfers (suplementos) from Ramos (b) and (c) to Ramos (a). Prior to the revolutionary wars, most deficits were a consequence of inevitable fluctuations in the arrival of the situado, the funds from Upper Peru. If such transfers proved insufficient, the authorities mobilised the necessary funds through loans and donations from the heads of notable families or institutions such as the Cabildo (city council) and the trade Consulado. Prior to their use by the administration of Ramos (a), these contributions were first recorded in Ramos (b) or Ramos (c), to be recorded later by the finance officers as internal transfers (suplementos) under the revenues for Ramos (a) under the heading of Otras instituciones, which also entailed tithes or the revenues of the tobacco monopoly (Amaral Reference Amaral1984, Reference Amaral2011, pp. 387-391, in particular Tables 1 and 4).

Amaral also describes the transfers in an accounting system based on a straightforward distinction between revenues/entrances (cargo) and expenses/withdrawals (data). Whilst it is impossible to reproduce the author's detailed account here, the recording of transfers (suplementos) of whatever nature and the corresponding restitutions (reintegros) had the effect of artificially inflating both the cargo and the data, but in different proportions (Amaral Reference Amaral2011, pp. 392-412). Amaral's first interpretation of the data gave rise to a debate in Reference Amaral1984. All of the participants in this debate recognised the existence of these transfer mechanisms, but interpreted them in different ways (Amaral Reference Amaral1984; Cuenca Esteban Reference Cuenca Esteban1984a; Fisher Reference Fisher1984; Halperín Donghi Reference Halperín Donghi1984; Klein Reference Klein1984; TePaske Reference Tepaske1984; see also Klein and Barbier Reference Klein and Barbier1988, pp. 43-44). Whilst the details of this debate are not of direct relevance to this paper, in the end, a degree of consensus arose around Amaral's interpretation and the quality of his research (Sánchez Santiró Reference Sánchez Santiró2013, pp. 14-28).

We thus have data for the period 1789-1821 that reflect the categories and procedures of the relevant financial officials, resulting in a homogeneous series for the whole period, despite the different contexts in which the figures were published (Amaral Reference Amaral1988, Reference Amaral and Liehr1995, Reference Amaral2011). According to the publications by Amaral used in Figures 1 and 2, suplementos to the treasury of Ramos (a) only proved necessary in 8 years between 1790 and 1821; they represented between 8 and 55 per cent of the additional funds. To estimate the level of indebtedness, one should discard the suplementos and their reintegros. This is not the purpose of our graphs here; however, we are interested in the changing institutional context of the transfers. We have identified and removed short-term transfers and compensations to offset the fluctuations in the arrival of the situado, but we have kept transfers to and from «other institutions». The latter were more or less in balance over a number of years—such as during the transfers of 1797, caused by the war with Britain—yet they no longer truly compensated for one another anymore after 1806. In maintaining the suplementos and their reintegros, it is possible to include the fact that custom revenues were used directly to pay 40 to 50 per cent of the debts after 1813, in particular for the amortisation of the forced loans, as is explained in the text.

Contributions from Urban Institutions, Forced Loans and Deficits, 1806-1821

Figure 2 mainly depicts the contributions from urban institutions that formed part of the ancien régime configuration of public finances. These were an aggregate of levies consisting of: (a) contributions from the Cabildo and the Consulado based upon their own funds, fed by their own taxes; (b) donations from individuals made through these institutions; (c) the Royal Monopoly of Tobacco and a tax administered by the Cabildo with a fixed aim (municipal de guerra) and (d) church levies (claveria de diezmo). Of these four categories, the contributions made by the Cabildo and the Consulado constituted 79 per cent of the total between 1806 and 1812. The data are from the «Other Institutions» series published by Amaral, which includes Grieco's individual grants and loans (Grieco Reference Grieco2014, Chs. 6 and 7).

The amounts of the forced loans in Figure 2 are estimated from the balance sheets of 1816 and 1819-1821, which provide details regarding claims made upon the public, the funds actually received by the authorities and the bonds in circulationFootnote 25. Our own figures from the archives suggest that a total of 2,608,280 pesos in loans was actually received by the sovereign power between 1813 and 1821. Amaral's data (Amaral Reference Amaral1988, Reference Amaral and Liehr1995) suggest a total of 2,924,100 pesos for the same types of loans. Despite the difference of around 300,000 pesos, the two sources complement each other, since his series are derived from the accounts of the Caja de Buenos Aires, which recorded public borrowing in cities in the interior that had been transferred to the capital, whereas the figures extracted from the aforementioned balance sheets refer only to the city of Buenos Aires. We retained the Amaral series for consistency.

The Income and Expenditure Balance Series therefore includes all contributions and reimbursements (suplementos and reintegros) in addition to taxes and current expenditures.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Samuel Amaral, the anonymous referees and the participants of the conference «The Economic Impact of War, 1648-1815» (Netherlands Institute for Advanced Studies, Wassenaar, 4-5 December 2014) and of the session «War and Economy. The consequences of wartime taxation, public debts and expenditure in the late medieval and early modern period» (World Economic History Conference, Kyoto, 5 August 2015) for their comments on the manuscript and its previous versions. The usual disclaimers apply.