1. INTRODUCTION

The idea that crises are good moments to introduce fiscal changes has been frequently stated by researchers (Mahon Reference Mahon2004; Bird Reference Bird2013; Alston et al. Reference Alston, Melo, Mueller and Pereira2016). There is a vast literature exploring the relationship between war and taxation (Tilly Reference Tilly, Evans, Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1985; Centeno Reference Centeno2002; Feldman and Slemrod Reference Feldman, Slemrod, Martin, Mehrotra and Prassad2009), and an increasing amount of evidence showing that other types of crises can unleash «windows of opportunity» for relevant fiscal changes (Peacock and Wiseman Reference Peacock and Wiseman1961; Legrenzi Reference Legrenzi2004; Alston et al. Reference Alston, Melo, Mueller and Pereira2016). Overall, it seems clear that certain events have a major potential for changes in the political and institutional arena in general, and taxation in particular. Those who study events in social sciences argue that events become significant when they are perceived as moments of rupture (Sewell Reference Sewell2005; Wagner-Pacifici Reference Wagner-Pacifici2016) and experienced as «discontinuous, disorienting and incoherent» (Wagner-Pacifici Reference Wagner-Pacifici2016, p. 63). These ruptures are powerful because they disarticulate society, therefore presenting an opportunity for rearticulating institutions in different ways.

Disasters prompted by extreme natural events such as earthquakes or hurricanes usually become ruptures that are followed by institutional changeFootnote 1. Earthquakes in particular are surprising and disruptive, multiplying social demands and overloading political systems, while disarticulating economies and revealing the administrative capacities of states (Oliver-Smith and Hoffman Reference Oliver-Smith and Hoffman1999). Yet, the impact of disasters on macroeconomic policy and taxation has seldom been examined in depth. In fact, Noy's (Reference Noy2009) review on the macroeconomic consequences of disaster found almost no research on the topic. Also, those who have considered fiscal variables when studying disasters have found it difficult to prove a significant connection (Rasmussen Reference Rasmussen2004; Cavallo et al. Reference Cavallo, Galiani, Noy and Pantano2010). In the case of Latin America, Albala-Bertrand (Reference Albala-Bertrand1993) studied the economic impact of disasters using a multiple case-study approach, showing that disasters usually call for higher government expenditure, and at the same time, tax revenue shrinks because of a contraction in production activities. However, no recent study has been carried out on the topic, even considering that in the last decades, catastrophes have confronted the world with its most demanding reconstruction challenges since World War II (Fengler et al. Reference Fengler, Ihsan and Kaiser2008), and the fact that in most cases, the available domestic resources are not sufficient to meet reconstruction needs (Parker Reference Parker2006; Cummins and Mahul Reference Cummins and Mahul2009). Consequently, international money-lending agencies are usually called on to finance reconstruction and provide support in terms of expertise, evaluations and technical advice. However, debt is not the only possible source of revenue; countries with higher state capacity can afford to deal with their own misfortunes using a combination of different funding sources, including loans, but also savings and taxation.

Considering that disasters are increasing globally, mostly due to the unregulated spread of metropolises and the adverse effects of climate change, it is important to research a possible relationship between catastrophes and institutional change historicallyFootnote 2. This paper contributes to this issue by exploring the case of Chile, a country that has been shaken by some of the biggest earthquakes in world history. These events have affected the country in terms of lives, health, infrastructures and the chances of economic development. Also, they have become moments of rupture, where important decisions have had to be made in order to deal with several problems, starting with the vast expansion of debris left by the earthquake. This paper explores the «fiscal aftershocks» of these catastrophes, with a focus on: (i) the influence of crises and ruptures, in this case disasters, that prompt windows of opportunity for policy change; and (ii) the role of values and narratives, such as patriotism and solidarity, in prompting and shaping those policies.

2. CRISES AND FISCAL REFORM

In recent decades, scholars have increasingly tried to understand when and how tax policies evolve (Steinmo Reference Steinmo2003; Bird Reference Bird2013). After all, taxes are «the nerve of the state» (Braun Reference Braun and Tilly1975, p. 243), since they influence state building, bring more people into the domain of state institutions and increase the provision of collective goods (Levi Reference Levi1988; Campbell Reference Campbell1993; Martin and Prasad Reference Martin and Prasad2014). Furthermore, it can be said that taxes «formalise the social contract» by way of institutionalising tolerable levels of inequality (Martin et al. Reference Martin, Mehrotra, Prasad, Martin, Mehrotra and Prasad2009) and acceptable means of redistribution (Martin et al. Reference Martin, Mehrotra, Prasad, Martin, Mehrotra and Prasad2009; Atria Reference Atria, Castillo and Maldonado2015; Agostini and Islas Reference Agostini and Islas2018). Thus, the question of taxation is not only about how a state is funded but also about how it constitutes itself and the relationship it establishes with its citizens. For some, this even means that the boundaries of the state can be exclusively defined in terms of its ability to tax constituents, to the point that we can see the history of state revenue production as a proxy for the history of the evolution of the state (Braun Reference Braun and Tilly1975; Levi Reference Levi1988).

As mentioned in the introduction, literature shows that relevant fiscal changes usually follow certain events that become ruptures. Chiefly, Tilly (Reference Tilly, Evans, Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1985) showed that war-making, extraction and bureaucracies to organise capital accumulation interacted to shape state-building in Western Europe. Wars require money, that is the bottom line. For developing nation-states in the 17th century, this meant taxation. In fact, scholars have repeatedly shown how in periods of war, public revenues and expenditures tend to rise abruptly, setting «a new, higher, floor beneath which peacetime revenues do not sink» (Tilly Reference Tilly, Evans, Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1985, p. 180). Among the first to argue in this line were Peacock and Wiseman (Reference Peacock and Wiseman1961) who showed that in the United Kingdom «people will accept, in a period of crisis, tax levels and methods of raising revenue that in quieter times would have thought intolerable» (Peacock and Wiseman Reference Peacock and Wiseman1961, p. 26). They came to this conclusion observing that public expenditures over time outlive periods of continuity separated by peaks that coincide with moments of disturbance, notably wars. Furthermore, after the crisis is over, there is a consistent post-war growth of governments, expenditure sometimes does fall afterwards, but usually not to pre-crisis levels. This phenomenon, called the displacement effect (Peacock and Wiseman Reference Peacock and Wiseman1961), means that crises not only provide the main stimulus to collect or create taxes, but they also set a new standard for acceptable taxation.

More recently, Legrenzi (Reference Legrenzi2004) has also shown that society usually tolerates a stable tax burden, but during wars and other «major social disturbances», ideas about the legitimacy of taxation change. In the case of Italy, the author claims that in wars «the public resistance against taxes is lowered in order to finance military expenditure. This lower resistance is maintained in the post-war period (to finance civil rather than military expending) and, as a consequence, government spending increases step-wide» (Legrenzi Reference Legrenzi2004, p. 191). These findings are consistent with what Bank et al. (Reference Bank, Stark and Thorndike2008) encountered in the United States; since the War of 1812, there have been special taxes to support every major military conflict in the United States, a trend that only stopped with G.W. Bush's administration. As a conclusion, they sustain that: «War has been the most important catalyst for long-term, structural change in the nation's fiscal system. Indeed, the history of America's tax system can be written largely as a history of America's wars» (Bank et al. Reference Bank, Stark and Thorndike2008, p. xii). In this case also, taxes have outlasted the wars they financed. Finally, Scheve and Stasavage (Reference Scheve and Stasavage2016) argue that wars can create an opportunity to increase taxes on the rich more than the rest of society. By analysing the cases of the United Kingdom, France, Canada and the United States before, during and after World War I, they show how the core principles of taxation changed, and calls for progressive taxes became stronger. To the extent that war created new inequalities in terms of the sacrifices required by states from its citizens—in the form of mass conscription and the need to fight—the notion of tax fairness was increasingly associated with higher taxes on the wealthy as a way of compensation. The introduction of conscription, meanwhile, implied that men with lower incomes were asked to fight; the «conscription of income» was demanded as a compensatory sacrifice via the contribution of more wealth in the form of taxes (Scheve and Stasavage Reference Scheve and Stasavage2016, p. 141).

In summary, we know that crises such as wars are moments of rupture with the power to change established conceptions of a tolerable tax burden, generating a displacement effect that can raise revenue collection. In the words of Bird (Reference Bird2013, p. 32): «major changes in tax structure and administration are usually possible only when times are bad, during a crisis of some sort. Only then is it possible to overcome the coalition of political opposition and administrative inertia that normally blocks significant change». The main reason this happens is that wars are expensive; in fact, probably the most expensive activity a state can engage in. This does not mean that tax changes during war are easy to implement, there can certainly be resistance. In the case of the United States, for example, previously mentioned works have described not only reluctance from the population but also strong resistance (Bank et al. Reference Bank, Stark and Thorndike2008; Lavoie Reference Lavoie2011). However, even in these cases, the result has been changes in taxation.

Apart from sheer necessity, another explanation for a relationship between war and taxation is the emergence of new narratives and interpretative frameworks linked to values such as solidarity and patriotism, understood as a demonstration of acquiescence and active consent to specific revenue demands of governments due to a «feeling of devotion to one's country» (Geys and Konrad Reference Geys and Konrad2016, p. 2). Specifically, wars may foster a feeling of «civic engagement» and «national pride» where the maximum marginal tax increases (Bank et al. Reference Bank, Stark and Thorndike2008; Geys and Konrad Reference Geys and Konrad2016). For example, Feldman and Slemrod (Reference Feldman, Slemrod, Martin, Mehrotra and Prassad2009) have shown that people are more likely to resist new taxation when wars are unpopular or considered unjust. Similarly, Scheve and Stasavage (Reference Scheve and Stasavage2016) believe that the social cost of raising taxes is reduced when these taxes are perceived as fair. As mentioned before, part of the potential of crises for change is that they force institutions to rearticulate (Wagner-Pacifici Reference Wagner-Pacifici2016). Importantly, rearticulating involves meaning; in other words, narratives and representational processes to frame different actions and decisions (Wagner-Pacifici Reference Wagner-Pacifici2016). This helps us understand why wars can increase perceptions and feelings that impact the legitimacy and willingness for institutional changes.

These findings are particularly relevant for the study of taxation and expenditure in the aftermath of catastrophes. Certainly, there are important differences between wars and disasters; most catastrophes affect certain areas of a country while wars involve a whole state, and most disasters are sudden, while wars allow for certain preparation. However, both present significant disruption and threat to social order, endangering the state's basic role of protecting citizens from physical harm. Also, most disasters have a similar impact on infrastructure and economic activity, which translates into new demands for money and state intervention. Finally, wars and disasters coincide in the feelings of solidarity or patriotism that usually emerge under distress, especially those of «national» proportions (Clancey Reference Clancey2006; Dickie Reference Dickie2008; Borland Reference Borland2011).

3. CASES AND DATA

Chile is recognised as one of the Latin American countries with the most stable institutions and a prosperous economy, having entered the select group of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in 2010 with a GDP per capita of $15,854 (nominal). However, historically high levels of economic inequality have persisted in the country. Data from the national household survey (CASEN) indicate that disposable income distribution barely decreased in the last decade (from a Gini coefficient of 0.49 in 2006 to 0.48 in 2017), positioning Chile among the most unequal countries in the OECD. We can also see this trend by analysing tax data. Using a novel series of Chilean top-income shares covering half a century (1964-2017), Flores et al. (Reference Flores, Sanhueza, Atria and Mayer2020) show that the top 1 per cent of income shares remain high—close to 13 per cent on average—across the period. Moreover, when the value of undistributed profits reported in the national accounts is imputed, income concentration is about 4-9 percentage points higher for the top 1 per cent. This wealth concentration is partially explained by a limited state capacity to tax constituents directly, particularly high-income groups (OECD 2015; Agostini and Islas Reference Agostini and Islas2018; Atria Reference Atria2019). This is partially explained by the availability of natural resources and mining activities that have historically represented a substantial source of fiscal revenue. Also, indirect taxes—such as the value-added tax and trade taxes—have historically prevailed over direct taxes such as income or property tax (Sokoloff and Zolt Reference Sokoloff, Zolt, Edwards, Esquivel and Márquez2007). In this context, it is interesting to show that some of the most important reforms of different periods in Chilean history occurred in the aftermath of highly destructive natural events.

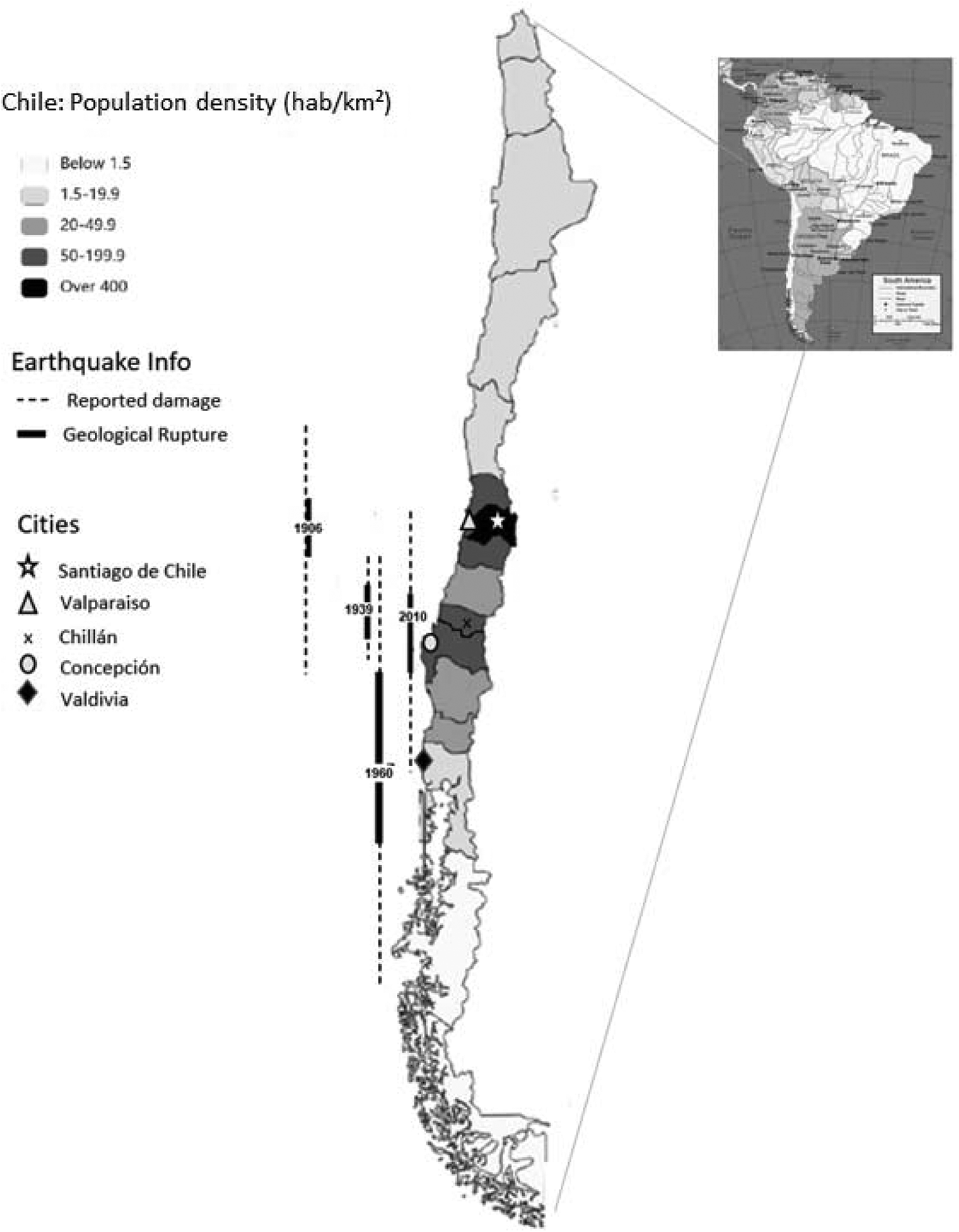

Located in the Pacific «Ring of Fire», Chile is regarded as one of the most highly seismic countries on earth (Lomnitz Reference Lomnitz2004). Since independence (1810), the country has experienced at least eighteen earthquakes considered «great earthquakes» (magnitude >8 Ms)Footnote 3. However, not all of this seismic activity has led to events in the political realm, since for an earthquake to become a disaster, there has to be a vulnerable population to experience the rupture (both geological and social). Taking this into account, geologists and historians coincide that four earthquakes constitute the greatest catastrophes in Chilean history: the 1906 earthquake of Valparaíso, the 1939 earthquake of Chillán, the 1960 earthquake and tsunami of Valdivia and the 2010 earthquake and tsunami that destroyed central-south Chile (see Figure 1). No other earthquake in Chilean history is comparable to these events in terms of the disruption caused to social order and, consequently, the challenges that they signified for the state. Importantly, all four earthquakes affected Chile's central and southern regionsFootnote 4. This means that they impacted heavily on the population, considering that 50 per cent of the population lives in the central area of Santiago and Valparaíso, and 35 per cent in the adjacent southern areaFootnote 5. This also means that the disasters spared the northern areas and had no direct effect on most of the mining sectorFootnote 6.

FIGURE 1 Location of events and their territorial impact.

Sources: Population density based on 2017 Census Data. Earthquake information calculated with data from U.S. Geological Services Database.

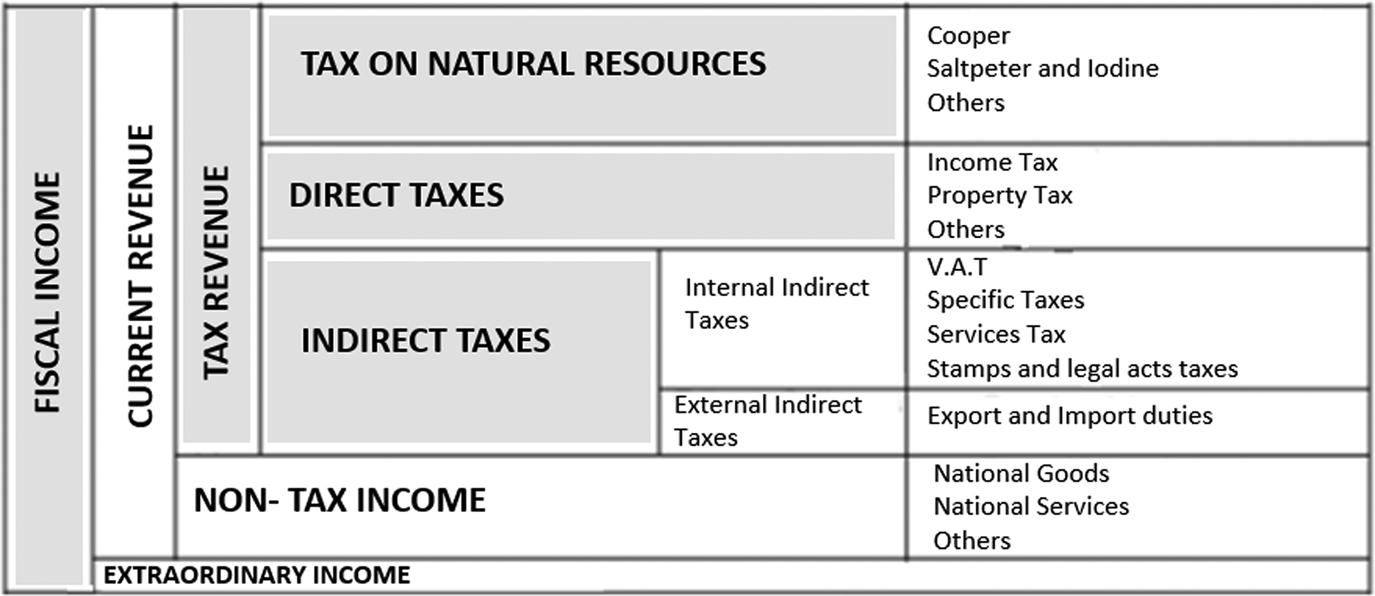

To analyse the «fiscal aftershocks» of these events, we rely on both qualitative and quantitative historical data. First, we present a qualitative analysis based on primary and secondary sources, mainly newspapers, congressional records and political discourses. With this, we intend to explain the disaster and the moment of rupture that followed. We then describe the narratives that were used to make sense of the event, with patriotism and solidarity as prominent frameworks for public and political discussion of events. Finally, we use quantitative historical data to describe Chilean fiscal structure in the period, and evaluate the changes brought about by the reforms made in the context of reconstruction in terms of its progressive or regressive nature. All tables were produced with data from EH-Clio Lab as described in Appendix A and organised according to Figure 2.

FIGURE 2 Structure of fiscal income and reported accounts.

Sources: Based on Jofré et al. (Reference Jofré, Lüders and Wagner2000).

4. THE VALPARAISO EARTHQUAKE OF 1906

On the rainy night of 16 August 1906, an earthquake magnitude 8.6 (ML) hit Valparaíso, followed by a small tsunami and several fires. The disaster left at least 7,000 casualties and more than 20,000 woundedFootnote 7. In one night, Chile's second largest city and most important port was almost completely destroyed, with no sanitation, electric power or telegraphic lines (Rodríguez and Gajardo Reference Rodríguez and Gajardo1906). The port itself was heavily damaged and left useless for several months. Apart from Valparaíso, most of central Chile was impacted; 200 kms north, the town of Illapel suffered significant destruction, as did Talca, 300 kms south (Rodríguez and Gajardo Reference Rodríguez and Gajardo1906; Zegers Reference Zegers1906). In Santiago—Chile's capital city—few casualties were reported but many buildings suffered significant damage, including the National Congress and the Presidential Palace. Chile is a country where earthquakes are part of life, but—because of recent urbanisation—this event was certainly the biggest disaster known to Chileans up until that date (Martland Reference Martland2006; Gil Reference Gil2017).

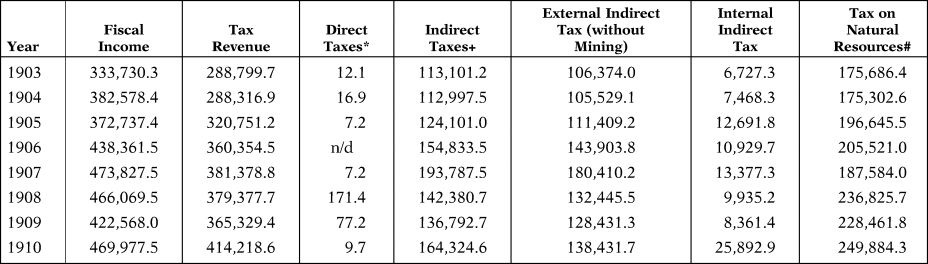

Valparaíso's earthquake happened during the last days of President Germán Riesco's rule, with Pedro Montt already elected for the next period. However, the country was at the time organised under a parliamentary system where the president held little power and appointed universal cabinets that were highly unstable (Fernández Reference Fernández2003). In this context, stability was assured by a shared understanding of the role of the state in society and a sound economy. Chilean politicians shared the basic ideas of liberalism (laissez faire, laissez passer); minimal state intervention on the economy. In terms of taxes, this meant that extraction from the population was almost non-existent (Fernández Reference Fernández2003). This was possible because the state co-opted half the surplus of the nitrate industry through export taxes, which constituted up to 60 per cent of the income of the Chilean state on average (Table 1). Another 39.9 per cent was income from other imports and exports and only 3 per cent was due to non-custom taxes. In this context, the destruction of Valparaíso was highly problematic since, at the time, ships with saltpeter coming from the northern regions were forced to stop in Valparaíso on their way to the southern channels. According to Pinto (Reference Pinto, Pinto and Baldomero1987), this meant that 75 per cent of the mining business was done in the city, whose elite had the economic control of the mines. Valparaíso also handled up to half the country's imports and internal coastal trade, which presented additional challenges for business (Schmutzer Reference Schmutzer, Estrada-Turra, Cavieres, Schmutzer and Méndez2000).

TABLE 1 Structure of fiscal income 1903-1910 [2013 million Chilean pesos]

Source: Calculated with data from EH-Clio Lab (see Appendix A for more information). Numbers and percentages have been rounded up to the nearest 0.1.

4.1 Unity From Pain

Almost immediately after the earthquake, a feeling of solidarity and unity started to arise in the press. Some narratives appeared with great clarity; there was a «public spirit» of Christian charity among citizens, accompanied by a strong show of political unity among parties. According to Onetto, the key to this narrative was «the pain citizens feel when observing the misfortune of their countrymen» (Onetto Reference Onetto2017, p. 61). However, even though a large part of the prerogatives for help were made in the name of Catholic values, patriotism also played an important role since these feelings reflected a renewed sense of identification with one's neighbour. Unity and solidarity were understood as «patriotic actions structuring the nation's identity» (Onetto Reference Onetto2017, p. 61). An expression of this feeling can be seen in the following poem by Samuel Fernández Montalva, published in the magazine La Lira Chilena:

An Earthquake of bloody footprint

It has only achieved in its rude work

To clean the dust in our superb star

To make it look brighter and more beautiful

Attached to the tricolor of our coat of armsFootnote 8

The poem appropriately reflects the sentiment expressed in the public sphere after the catastrophe. The message was strong: Chile's most beautiful city had been destroyed and it was a duty to rebuild it again, even better than before. This reconstruction imperative was seen among the elite as a patriotic endeavour that translated into a plan for a new, modern, Valparaíso (Gil Reference Gil2017). In fact, the rupture generated by the earthquake unlocked a long-standing debate to rearrange public space in the city, an opportunity for progress motivated by «patriotic pride» that meant to put «a good face» on the tragedy but also to commit to reconstruction (Martland Reference Martland2006; Gil Reference Gil2017). However, as we will show next, the plan for reconstruction did not consider the whole country, or even the whole city. It was an ambitious intra-elite agreement for a new «modern» city that was highly expensive (Gil Reference Gil2017). How to pay for it, therefore, was an important part of the discussion.

4.2 The Plan for the Reconstruction of Valparaíso

As previously mentioned, during the period of the Parliamentary Era in Chile, there were almost no direct taxes on the population and major country estates (haciendas) paid no property tax, even though agriculture was still the country's main economic activity (Fernández Reference Fernández2003). Also, whatever direct taxes existed in the country had been transferred to local governments in 1891 by the Law of the Autonomous MunicipalityFootnote 9. According to this law, the central government had very little to say in local politics; it was the municipality's duty to collect internal taxes, secure social order and even organise elections (Fernández Reference Fernández2003). Municipalities, then, levied property and other (albeit small) internal taxes, such as the sale of alcoholic beverages, sealed paper and automobile registration plates. The first direct taxations at the national level were not created until 1915. Thus, it is difficult to analyse this event by looking at macroeconomic numbers. As we can see in Table 1, there was no significant increase in tax revenue and taxes on natural resources (by way of export tax) continued to be the main source of revenue in the country.

In this context, it is remarkable that the «Law for the Reconstruction of Valparaíso» contemplated taxes to pay for the new city plan. As mentioned, public works and infrastructure projects were locally decided and locally financed; the reconstruction law, however, created a Reconstruction Board that responded to the central governmentFootnote 10. It also authorised an increase in property tax to 0.5 per cent to pay for the city's share of the plan, subject to presidential approval. The rest of the plan was paid by the National Treasury (by the way of a loan to be used in the reconstruction of public buildings and to pay for expropriations); the property owners (who had to pay 50 per cent of the money needed to rebuild their street front or choose the expropriation of their land); the sale of the expropriated land that was not going to be used for public space and, finally, reconstruction had to be paid by the Municipality of Valparaíso. Under this law, the state was considered a creditor of the municipality, since the money from property tax was used to pay the loans that the state had signed to help the city. For this reason, when the reconstruction of Valparaíso was already underway (1910), the tax was reaffirmed; the municipality was allowed to increase property tax once more (0.3 per cent) and to double the tax on industrial and professional activities in the city. In addition to these measures, it was decided that the taxes would pass directly to the state, in order to assure that the municipal government was going to fulfil their part of the deal (Martland Reference Martland2006). The foreign loans meant more debt, but external debt had been increasing steadily in the past decades with several international loans for public works (Vitale Reference Vitale1990) and the impact of the new loans was minor (online Appendix Table B1). In fact, the first loans used for reconstructing Valparaíso had been requested in January 1906, months before the earthquakeFootnote 11. It is also important to mention that the new loans generated more contestation in Congress than the taxes, since the tax changes were local, but loans had an impact on the national accountsFootnote 12. Many representatives argued that the loans benefited Valparaíso only, and therefore, the property taxes were created to ensure the city could pay its part.

As mentioned before, this law was discussed under a renewed sense of solidarity and unity; however, it is difficult to say that the final plan was truly solidary or progressive. On one side, property tax is a form of tax that affects elites the most, since lower-income people are not usually property owners. Yet, it must be taken into account that the project for the reconstruction of Valparaíso did not include the whole city but only the «flatlands»; this includes the port and some of the most affluent areas of the city (Martland Reference Martland2006; Gil Reference Gil2017). Also, the rest of the country received almost no help from the central government. As Savala (Reference Savala2018) has shown, solidarity and organisation in workers' communities was prompted by the earthquake, while they felt completely left behind by the state's response. Middle-class property owners were also dissatisfied with the plan and saw no gain from expropriations to build a «modern» city (Gil Reference Gil2017; Savala Reference Savala2018). Overall, it was a project that taxed elites, to develop a plan designed by elites to serve the values and objectives of elites. However, taxes developed under this law were significant, when understood in the context of the Chilean Parliamentary Republic. Since in this period taxes on citizens were almost non-existent, the increase in property taxes demanded by the state to pay for reconstruction was an important development, and marked the beginnings of a new relationship between the state and the city that later expanded to other parts of the country (Martland Reference Martland2006).

Taking everything into account, it is clear that the rupture generated by the 1906 earthquake constituted a «window of opportunity» for changes in the politics of taxation in Chile. As we will see repeatedly in our next cases, a state of laissez faire is very difficult to maintain under the pressure of destruction and calamity. We call this first mechanism of state-building under disaster the imperative of debris; someone has to do something with the ruins or everyone's future is in jeopardy. In Chile, from 1906 onward, this someone would be the state.

5. THE CHILLÁN EARTHQUAKE OF 1939

On 24 January 1939, more than a dozen Chilean cities suffered almost total destruction after a 7.8 Ms earthquake hit central Chile. The shock was felt from Santiago to Temuco, but Chillán—capital of the Ñuble province—suffered most. Because industrialisation and urbanisation had increased, destruction was significantly greater than in 1906. Throughout Chile, all communications and services were down; telephone, telegraph and electricity services were interrupted. Most roads and railways were also destroyed, as were at least 30,000 houses across the country (Behm Reference Behm1942). Not surprisingly, this event caused the highest death toll of any disaster in the history of the country with at least 20,000 casualtiesFootnote 13. Chile was, once again, at rock bottom, and this time people immediately looked to the state for answers.

President Aguirre-Cerda was a left-wing politician, governing with the Popular Front under a presidential systemFootnote 14. He had been a schoolteacher and his victory meant that, for the first time, non-elite groups were represented in Chile's executive government. He had campaigned with radical proposals, such as the complete change of the role of the state in the economy. However, he faced strong opposition in Congress, and some representatives even questioned the validity of his recently won election (Super Reference Super1975). The earthquake, however, gave him the leverage needed to do what he had campaigned to do. In the name of reconstruction and recovery, he proposed two new institutions: the Reconstruction and Assistantship Corporation (CRA), and the Production Development Corporation (CORFO) in charge of economic recovery. Taken together, these new institutions meant that, during the next period of Chilean history, the state would lead industrialisation in the country. Aguirre-Cerda had wanted to do something along these lines since before the earthquake, but he only managed to pass the bill in Congress due to the inclusion of the CRA in the same bill as the CORFO. For the government, reconstruction and industrialisation needed to go hand in hand because «there is no other way to recover lost value and economic depression than to augment production»Footnote 15. As Muñoz and Arriagada (Reference Muñoz and Arriagada1977) and others have shown, Chilean elites had been discussing the need for greater industrialisation in the country in recent decades; there was, however, no agreement on the role of the state in this agenda (Meller Reference Meller1996), and the earthquake helped create the circumstances that forced the decision (Muñoz and Arriagada Reference Muñoz and Arriagada1977). In fact, the bill was passed with the support of two opposition senators representing Chillán, who surrendered to the bill because of the social pressure to get reconstruction started (Super Reference Super1975). Overall, the earthquake of 1939 opened a window of opportunity for state-led industrialisation in the country with consequences that exceed the focus of this paper. Importantly, however, the creation of the CORFO and the CRA to deal with reconstruction meant a demand for fiscal income that was met, in part, with new taxation.

5.1 A Remedy of National Character

As previously argued, the narratives and frameworks used to interpret crises are crucial to understand how these events evolve (Wagner-Pacifi Reference Wagner-Pacifici2016). As Blyth (Reference Blyth2002) stated, ideas matter especially in periods of crisis because «agents must argue over, diagnose, proselytise and impose on others their notion of what a crisis actually is before collective action to resolve the uncertainty facing them can take any meaningful institutional form» (Blyth Reference Blyth2002, p. 9). In this case, we found, once again, that solidarity and patriotism are intrinsically linked to the discourse that the government employed to secure the votes of the opposition for the reconstruction project. While going on tour around the country addressing the population, Aguirre-Cerda argued:

The pain has been horrible, and it needs to be comforted with actions that will go into salving of the thousands of wounded that cover a fourth of the national territory. But it is known that here in Santiago, and across the country, people have responded with patriotism and generosity unknown until todayFootnote 16.

The government justified the project with a communitarian idea: «we all have suffered and we all need help»—claimed the president—«therefore, the remedy for the consequences of the catastrophe requires the cooperation of everybody, it is a remedy of national character»Footnote 17. This idea was shared by public opinion, as an editorial of the newspaper El Sur stated in order to support the government's project; «it is indispensable that all politicking is left aside and, instead, solutions are looked for with patriotic eagerness»Footnote 18. The result of Aguirre-Cerda's campaign and the support of the press was the approval of the CORFO Law in Congress, with its respective increase in taxes.

5.2 Reconstruction and Recovery

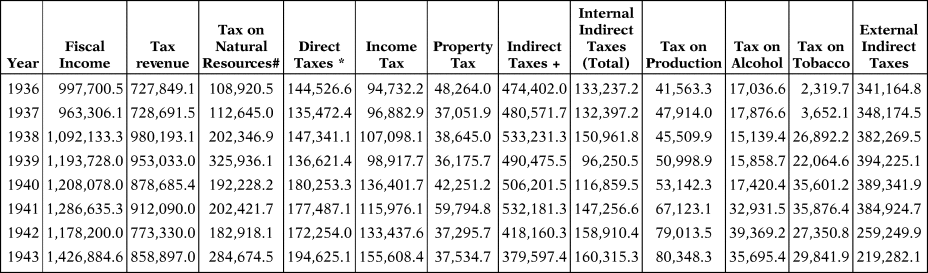

For Aguirre-Cerda, institutional developments such as the CORFO should be paid for by taxes. Consequently, the reconstruction bill included an ambitious tax reform. The position of the government was that «this situation must be considered as provoked by a state of war and, as such, must be financed with the resources of all citizens and those who reside in the territory»Footnote 19. However, the government was asking Congress for the authority to spend 2.5 billion pesos above regular national revenue, the equivalent of the entire public budget for a year. Thus, international loans were needed, and the Minister of Finance defended both measures in CongressFootnote 20. After weeks of arduous discussion and even fights (both from the opposition and allied parties), the final bill for the creation of the CORFOFootnote 21 contemplated a comprehensive fiscal reform that included a 2 per cent increase on income from property tax, 2 per cent on income for industry and commerce, 2 per cent on mining and metallurgic activity, and 1per cent on other additional sources of income, including salaries. Additionally, inheritance tax was increased by 50 per cent and the law also created new taxes on agriculture and a new patent for mining activities. Later, a 6 per cent tax on foreign corporations was added. As a newspaper of the time put it: «one can say that there will be an additional tax, more or less strong, to just every economic activity in the nation»Footnote 22. One of the changes that affected the original bill is that certain taxes that applied to national companies were extended to the (mostly foreign-owned) large-scale mining companies with an additional 10 per cent increase in corporate income tax on profits (12 per cent total). Since these companies also fell into other tax categories that experienced modifications, the reform was felt as a heavy blow by the sectorFootnote 23.

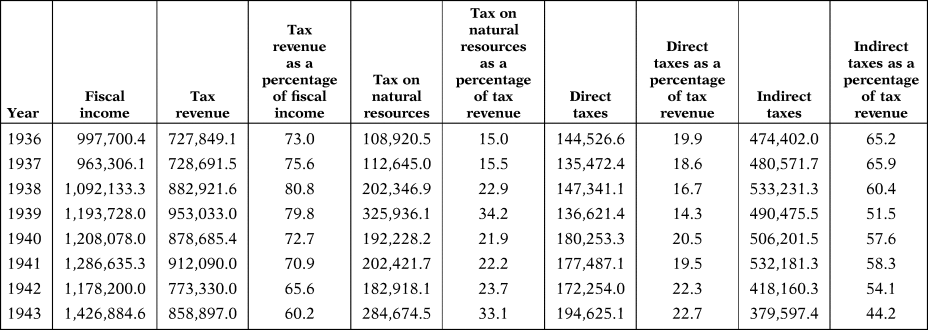

We can see the overall effect of this reform in Table 2. There is a small increase in the amounts of tax revenue, and some important changes in its composition: the relevance of direct taxes grew from about 14 per cent in 1939 to 20.5 per cent in 1940 and continued to increase until the end of the reported period. Most of the direct tax revenue corresponds to income tax (about 65 per cent, see online Appendix Table B6) which indicates that the reform was slightly progressive, even if indirect taxes continued to be the main source of taxation in the country. In terms of indirect taxes, all categories suffer a hike, but especially the tax on tobacco (online Appendix Table B6). The impact on taxation due to natural resources can be seen clearly in Table 2, but taking into account the fact that the reform was retroactive in practice and it considered the reported gains for 1938Footnote 24. Importantly, this tax increase was defined as temporary, but—as in the case of wars—in 1948, a new law made most of these taxes permanent.

TABLE 2 Structure of fiscal income 1936-1943 [2013 million Chilean pesos]

Source: Calculated with data from EH-Clio Lab (see Appendix A for more information). Numbers and percentages have been rounded up to the nearest 0.1.

In terms of debt, Chile turned to the United States for loans, but the CORFO law authorised the government to apply for international loans with a maximum of 3 per cent interest, which made loans almost impossible to obtain (Vera Reference Vera1942; O'Brien Reference O'Brien1977). Loans requested under this law proved insufficient and Chile terminated payments on its external debt in 1940 (until 1945). Internal debt due to the CORFO Law did increase, but external debt was minor (online Appendix Table B2). An analysis of the state's ledgers shows that reconstruction was mostly managed with fiscal income (Vera Reference Vera1942, p. 919)Footnote 25.

Taking everything into account, the relationship between taxation and reconstruction is clearer here than in the 1906 case. Particularly, the state is no longer seen as responsible for reconstructing public infrastructures only, but also private houses (hence the creation of the CRA) and economic recovery (with the CORFO). Consequently, the need for revenue was larger this time too. Furthermore, ideas such as solidarity and patriotism helped shape the disaster, in a moment where Chilean people were eager for social change; therefore, these ideas were stamped more clearly in the reconstruction plan after the earthquake.

6. THE CATACLYSM OF 1960

In May of 1960, Chile suffered one of the worst catastrophes in the history of the world when two consecutive earthquakes (magnitude 7.3 Ms and 9.5 Mw) and a massive tsunami destroyed Chile's southern coastal cities. At least 3,000 lives were lost and 300,000 people were left homeless and exposed to the hardship of winter; additionally, 542,216 square miles containing one-third of the Chilean population and 65 per cent of the country's arable land had been impacted (World Bank 1961a). It was, by any standards, a true cataclysm.

Chilean President Jorge Alessandri had been in power considerably longer than Aguirre-Cerda when this disaster happened. When he took power, in 1958, he had some clear goals. First, he intended to reduce state intervention in the economy; and second, he wanted to increase the efficiency of the state in order to reduce taxes (Stallings Reference Stallings1978). Alessandri was an engineer who had avoided partisan politics for years and was considered politically independent, but to all intents and purposes, he represented the interests of the ruling economic class (Dominguez Reference Dominguez1981). After decades of leftist rule, Alessandri's government was intended to be a reorientation of political economy in Chile towards a more liberal state. However, after the earthquake, reconstruction and recovery forced Alessandri to change his strategy. First, he had to become more political, appointing some allied Radicals to his cabinet. Secondly, he had to take a step back in his stabilisation plan and increase the involvement of the state in the economy, including the creation of new taxes to pay for reconstruction. This was not a product of the government's convictions, but a direct result of the catastrophe (Dominguez Reference Dominguez1981), combined with the external pressure of the United States (World Bank 1961b).

6.1 A Chain of Solidarity

As mentioned in the other cases, the framework to discuss reconstruction efforts is crucial for understanding the changes that come as a solution, since ideas offering a diagnosis of «what is wrong» influence the way people think about «what is to be done» (Blyth Reference Blyth2002). This case is interesting in this regard because Alessandri was openly against increasing state capacity to deal with reconstruction and he refused to discuss new institutions for reconstructionFootnote 26. However, he could not avoid the need for money to reconstruct, and his reconstruction bill included both new taxes and permissions for loans. The argument for the new taxes was that they were needed to pay for the loans: «we should lead by example, and demonstrate our capacity to raise money to help our countrymen in disgrace. A country that is not moved by the misfortune of several of its members is not a country that deserves external help»Footnote 27.

The country had, in fact, been deeply moved; a feeling of solidarity and patriotism impregnated society, and this was also mobilised to argue for changes. As an editorial of the conservative newspaper Diario Ilustrado describes a few days after the quake:

Facing the extraordinary magnitude of the tragedy that has desolated great part of the territory, saddening the whole country, we have observed the most noble reactions from every area of national activity, because when confronted with pain and tragedy, Chileans have always proceeded with a profound patriotic consciousness and a noble Christian spirit, raising their hearts, fortifying their faith in the destiny of the nation, regrouping in the crucible of sacrifice their most high aspirations of common goodFootnote 28.

In the days that followed, the press both described and imposed a «spirit of unity and solidarity», highlighting how politicians had agreed an official «truce» in favour of helping in the emergency and facing reconstruction (Onetto Reference Onetto2017, p. 69). According to Ercilla magazine, Chile was overwhelmed by a «chain of solidarity» that made every Chilean available for the task of reconstructionFootnote 29.

6.2 The Project for Reconstruction and Economic Recovery

After the earthquake, thousands of new homes were needed to accommodate earthquake victims and thousands of kilometres of road had to be repaired, to mention but two of the major problems. To address these issues, the government sent a project to Congress with a comprehensive plan for reconstruction that was approved in about 5 months, after a long and difficult debate. The bill addressed several issues, giving special powers to the president, adding new functions to the Ministry of Economy, and coordinating the investment of fiscal resources in order to address the new priorities created by the event. As mentioned, this included changes in taxation. As proposed by Alessandri, the most contested part of the bill was a 1 per cent increase in income tax for everyone in employment, including workers. The opposition fervently refused but, in the end, the reconstruction law of 1960 included a 1 per cent increase in social security deposits in the name of the workers that was destined to «housing»Footnote 30. In terms of taxes, the law was very complex, with several changes in taxation including a rise in taxes on luxury items, alcoholic and non-alcoholic drinks, new tariffs for automobile registration plates, a tax on public entertainment (with the exception of soccer games), a 20 per cent increase in some categories of tax income, and a 23 per cent increase in property tax for the year of 1960 (except for the regions most affected), among many other small changes in indirect taxes. In terms of taxes on natural resources, mining companies were included in the income taxes that were increased by the new law. Also, the law revoked changes in the rate of some taxes made in 1958. Some of these taxes were only supposed to last 3 or 5 years, but as we have seen before, the taxes were confirmed later.

Table 3 shows the effect of the reform. We can clearly see that the importance of tax revenue in the finances of the country had increased significantly since 1939, and it increased even more after the 1960 earthquake. In terms of the actual structure of fiscal income, there is a moderate increase in the relevance of direct taxes. If we look into the data in more detail, we see that property tax declined while income tax increased its importance; while in 1959, income tax represented 13 per cent of tax revenue, in 1961, it was up to 19 per cent (online Appendix Table B7). In terms of indirect taxes, we can see a moderate increase in most entries, especially V.A.T (Table B7).

TABLE 3 Structure of fiscal income 1957-1964 [2013 million Chilean pesos]

Source: Calculated with data from EH-Clio Lab (see Appendix A for more information). Numbers and percentages have been rounded up to the nearest 0.1.

The spirit of reform did not die with the reconstruction law of 1960, and the government started to project new tax changes almost immediately, even though official discussion of a new bill in Congress did not start until mid-1962. This new law was promulgated in 1964, and included a general restructuring of income tax, together with modifications of inheritance taxFootnote 31. This reform explains the hike in direct taxes in 1964, since these modifications also included an increase of the top marginal income tax rate to 60 per cent. However, income tax maintained a low redistributive component in the 1960s due, firstly, to an erosion of the tax base by multiple tax exemptions and reductions, and secondly, due to high levels of evasion, which decreased the potential tax base by up to 40 per cent (Foxley et al. Reference Foxley, Aninat and Arellano1980, p. 111).

The World Bank estimated that the reform would collect an extra 100 million dollars for the Chilean state (World Bank 1961a), an impressive but insufficient sum. With this knowledge, the law also authorised the government to take on new internal and external loans of up to US$500 million. The impact of debt was significant (online Appendix Table B3), as Chile became highly indebted to international agencies and the United States. The political influence and economic relevance of the United States as a financer of Chilean economic policies persisted for several decades. This means that money came with strings attached; in this case, a plan that considered social development or even specific «development projects» (World Bank 1961b; Dominguez Reference Dominguez1981). Still, changes in taxation were relevant, and especially because the reform was, to some extent, progressive.

Overall, this case shows how the window of opportunity created by this devastating earthquake and tsunami led to transformations in state capacity in the country. Broadly speaking, the earthquake—or more specifically, the imperative to do something about the debris—forced Alessandri's government to change the direction of his economically conservative plan. This happened because economic and social needs changed, and because money lending agencies demanded it. The tax modifications reluctantly included in the 1960s reconstruction law are relevant in the context of a historically regressive fiscal pact, even if they did not drastically change the redistributive capacity of the tax system in the long run.

7. EPILOGUE: THE MAULE EARTHQUAKE OF 2010

In 2010, Chileans were preparing to celebrate 200 years of independence when the plans were truncated by yet another major catastrophe. On the night of 27 February, an earthquake of 8.8 magnitude hit the central and southern areas of the country, followed by a huge tsunami. According to the Chilean government, the catastrophe killed 550 people and damaged more than 50 cities and 900 towns, leaving 75 per cent of the Chilean population affected and more than 220,000 families with severe damage to their homes. The economic cost of this destruction was calculated as US$30 billion, accounting for 15 per cent of the GDP of the country. The event surprised a country unprepared in terms of emergency management, even considering the relatively low fatality rate for such a large event.

This earthquake happened during the last days in office of socialist President Michelle Bachelet, with conservative Sebastián Piñera already elected for the next period. Piñera, a businessman who had previously held office as a senator, was the first democratically elected right-wing president of Chile since Alessandri in the 1960s. Piñera's campaign, like that of Alessandri, had centred on issues such as economic growth and government efficiency; he also intended to decrease some taxes in order to reduce the size of the state. Coincidences also include the fact that his initial cabinet was formed of businessmen considered «independent», even though they represented the Chilean elite. Together, they hoped to reform the Chilean state, but this time debris also forced them to change their plans.

7.1 An Exceptional Challenge

As with previous disasters, the event was framed within a narrative of strong patriotism and solidarity. The picture of a man holding a muddy Chilean flag among the debris left by the sea filled newspapers and social media, and the campaign «Chile helps Chile» ran for 25 hours on national television, collecting funds for recovery (doubling its goal). However, more was needed to pay for reconstruction and ensure economic recovery, and Piñera had to set the pace for how to fund this endeavour. In his own words:

We either walk slowly towards recovery, taking decades for returning to our previous state of development, or we assume an exceptional challenge, facing the task in a few years by asking all Chileans—and specially to those more affluent—a sacrifice that will put us back in the leading position we held before the tragedy (…) if we want Chile to achieve full development during this decade we must assume the risks and take bold decisions that will take us there. The model for financing this premise is based on fiscal stability, but it also has an inspiring angle: solidarityFootnote 32.

7.2 The Reconstruction Plan

The financial plan designed by the new government considered several sources of income, including taxes, tax benefits for donations, money from the copper industries and the abandonment of other expenses considered in the national budget. The four previous centre-left governments had scarcely addressed Chile's regressive tax system, and now Piñera had to lead a tax reform that was seen as an opportunity to discuss inequality and not only reconstruction. The financial plan, contemplated in a new reconstruction law, created the National Fund for Reconstruction, and considered permanent and transitory tax modifications to increase fiscal revenue. They included a temporary increase of 3 points in corporate tax, which rose from 17 to 20 per cent (for 2011)Footnote 33. Also, a second law to address reconstruction was enacted by the end of the year to modify the taxation of the mining industry, significantly increasing the tax on copper; this was nonetheless compensated with other tax benefits for the industry, such as a 6-year clause on tax invariability (Rivera Reference Rivera2012)Footnote 34. The debates regarding both laws were marked by the need to reconstruct, but also a strong ideological battle. The centre-left coalition valued the tax increases but regretted that some were transitory. On the other side, the parties loyal to the government disagreed about the necessity of such reform and only agreed in the end because most taxes were transitory (and probably, they felt the need to support President Piñera). Not surprisingly, in 2020, the taxes have remained beyond their expiration date.

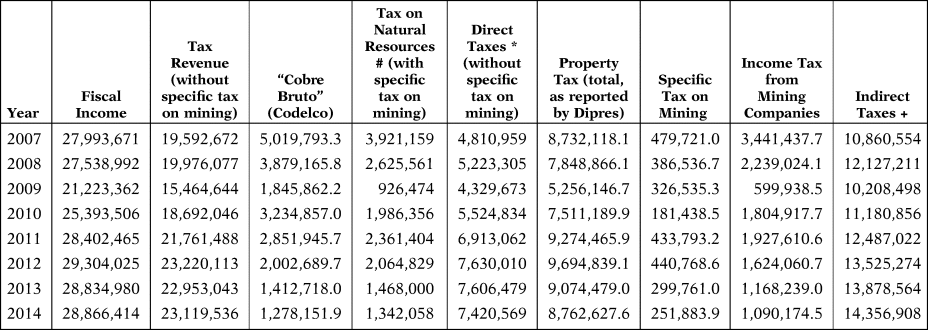

As we can see in Table 4, the reform had a visible impact on tax revenue, and particularly on direct taxes, even if not substantially changing the progressivity of the tax system. Indirect taxes are still the main source of tax revenue in Chile, but the increase in direct taxes is due mainly to a hike in income tax from 2010 onwards (online Appendix Table B8). It should be noted that we have not included as direct taxes those collected from the mining industry. Debt was also important, especially domestic debt which increased significantly after 2010 (online Appendix Table B4); by 2016, 60 per cent of Chilean debt was in local currency. Finally, however, 78 per cent of the official reconstruction plan was financed by tax revenue and budget reallocations (Ejsmentewicz Reference Ejsmentewicz2013).

TABLE 4 Structure of fiscal income 2007-2014 [2013 million Chilean pesos]

Source: Calculated with data from DIPRES, but following the classification system proposed by EH-Clio Lab (see Appendix A for more information). Numbers and percentages have been rounded up to the nearest 0.1.

However, this reform did not calm the voices asking for larger changes in taxation. Together with the other social demands motivated by numerous and massive student protests, this meant that in 2012, Piñera had to once again ask Congress to rethink the tax structure of the country and a new reform was approved in September of that yearFootnote 35. This new law established that the 2010 transitory increase in corporate tax became permanent, adding new taxes, regulations designed to eliminate loopholes and a reduction in the personal income tax rate aimed to help middle-class groupsFootnote 36. This reform, however, was also considered insufficient by those in favour of progressive and redistributive changes, and the fiscal debate remains very much present in Chile today (Atria Reference Atria, Castillo and Maldonado2015).

Overall, the more recent 2010 earthquake allows us to reflect on similar issues to the other cases. On one side, it was a rupture that allowed some important institutional changes. On the other hand, transformations were short-ranged and—for many Chileans—insufficient to fight persistent inequality. Still, the 2010 earthquake shows that disasters today also present themselves as windows of opportunity, and furthermore, windows to explore the inner workings of societies and political arrangements. As Sehnbruch et al. (Reference Sehnbruch, Agloni, Imilan and Sanhueza2017) have shown, reconstruction after the 2010 event revealed several institutional weaknesses of the Chilean state, such as a targeted approach to lower-income groups that ignores a vulnerable middle class much affected by the disaster. Similarly, the tax reforms after this earthquake also suggest that appeals to fiscal patriotism and solidarity involved neither a profound social transformation, nor a radical change in the fiscal structure. It seems that, in the process of rearticulating, there are windows of opportunity for changes, but power relationships also remain.

8. CONCLUSION: DISASTER AND TAXATION IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

To conclude, it is important to highlight what this study can tell us about a possible relationship between catastrophe and the politics of taxation. First, it is clear that crises and ruptures generated by socio-natural disasters can generate enough institutional fluidity to allow for institutional change in general, and fiscal policies in particular. These events disarticulate societies and institutions in different ways, and in the process of rearticulating, we found a «window of opportunity» for changes. The outcome of such a rupture and the institutions that are disrupted will depend on different factors, including the particular circumstances of the event and the actors involved. There are, however, at least two mechanisms that help understand how disasters and fiscal policies interact. First, catastrophes impose certain needs and amplify some public policy problems, therefore pressuring the state to intervene in society in new ways or with more intensity. We have called this the imperative of debris, but other types of disasters with less impact on infrastructure may also have a similar effect. Second, we argue that the outcome of a rupture will greatly depend on the power of political actors to frame the crisis in terms favourable for their objectives, even if they cannot always do as they please. In the case of Chile, the fact that disasters tend to generate a renewed sense of solidarity and patriotism is in itself a window of opportunity to discuss fiscal reform. Paraphrasing Bank et al. (Reference Bank, Stark and Thorndike2008), taxes may never be more popular than during wars, but they are certainly popular after disasters.

The importance of the patriotic narrative also deserves some attention. As Benedict Anderson famously argued, identification with the fellow members of our «imagined community» can highlight the feeling of «comradeship» that prevents individualism and selfishness (Anderson Reference Anderson1983). This could indicate that a certain sense of devotion to one's country can be more valuable than the literature about nationalism suggests. In fact, our research shows that this feeling of patriotism can serve as an argument for fiscal solidarity and a detriment for any free rider impulse. However, we need to understand patriotism as the development of a robust sense of solidarity among a political community of citizens, and not defined by race or nation. Also, our cases show that narratives of patriotism are constructed, and crises provide the perfect moment to shape their meaning. As Brubaker (Reference Brubaker2004) has suggested, the question of what «defines us as a nation» is not a matter of facts, but of public narratives shaped and reshaped by history and events. These narratives seem to become stronger and clearer when the community faces challenges such as catastrophe or war.

Still, it is not clear whether the reforms made after Chilean catastrophes, in the spirit of patriotism and solidarity, are as progressive as the narratives will have us believe. On the one hand, specific taxes or duties were increased after each catastrophe, legal loopholes were closed, and personal income and corporate tax rates were raised temporarily or permanently. On the other hand, changes to direct taxes were very small, and only slightly progressive in some cases. Even though in some reforms changes are more significant, the relative importance of direct taxation was not substantially altered after the four disasters presented here, and the introduction of some progressive taxation does not seem to have had a relevant impact on the tax structure. As a whole, the redistributive capacity of Chilean fiscal policy remains low, which leads to an inability to reduce persistent inequalities (OECD 2015) and to several limits to tax elites in a context where high-income concentration is severe (Flores et al. Reference Flores, Sanhueza, Atria and Mayer2020). Overall, we see that while patriotism and solidarity clearly work as a narrative to frame reconstruction and fiscal policy in the country, the reforms were not fully redistributive at their core. As a result, we conclude that catastrophes may generate windows of opportunity for institutional change, but they do not completely change power relations between economic and political actors. Major earthquakes remain, however, as an important explanatory factor for fiscal structure in Chile today.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0212610921000070

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Germán Alarcón and Cecilia Correa for their help with historical data and sources and the Observatory of Socioeconomic Transformations of the Max Planck Institute in Chile [ANID/PCI/MAX PLANCK INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF SOCIETIES/MPG190012] for supporting this project. This research was partially funded by the Research Center for Integrated Disaster Risk Management (CIGIDEN), [ANID/FONDAP/15110017], the National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development (FONDECYT), Grant number 11181223, and the Centre for Social Conflict and Cohesion Studies (COES), [ANID/FONDAP/15130009]. The study sponsors had no role in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

SOURCES AND OFFICIAL PUBLICATIONS

Sección Ley Chile del Departamento de Servicios Legislativos y Documentales de la Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional (BCN). Disponible en: https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/

Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile. Santiago de Chile. Actas del Congreso Nacional de Chile (1906, 1939, 1960); Sesiones Extraordinarias de la Cámara de Diputados (1906, 1939, 1960)

Biblioteca Nacional de Chile (BNCh). Santiago de Chile. Sección Periódicos. El Mercurio (1939 y 1960); La Lira Chilena (1906), El Sur (1939); La Nación (1939); Boletín Minero (1939); Diario Ilustrado (1960), Revista Ercilla (1960)

APPENDIX A

METHODOLOGICAL NOTE

The Economic History and Cliometrics Lab (EH-Clio Lab) at the Economics Institute of P. Universidad Católica de Chile provides information on historical economics in Chile. Several of their articles and working papers were consulted to build the tables. These sources are consistent with each other, but each one provides different information. See http://cliolab.economia.uc.cl/publicaciones.html

Díaz, J., Lüders, R., and Wagner, G. (2016a): Chile 1810-2010: La República en Cifras. Santiago de Chile: Ediciones Universidad Católica de Chile.

Diaz, J., Gómez, C., and Wagner, G. (2016b): «Construcción de Cuentas Fiscales 1810-2010: Dos Exploraciones Específicas». EH-Clio Lab. Working Paper #25.

Jofré, J., Lüders, R., and Wagner, G. (2000): «Economía Chilena 1810-1995: Cuentas Fiscales». EH-Clio Lab. Working Paper #188.

Unfortunately, these sources only contain data until 1990, 1995 or 2010; therefore, to build the table for the 2010 earthquake (2014–2017), we used the quarterly reports published by the Budget Office of the Chilean government (Dirección de Presupuesto, DIPRES) for the period 2007–2015, but following the classification system proposed by our historical data (EH-Clio Lab). To do so we used:

Rodríguez, J., Vega, A., Chamorro, J., and Acevedo, M. (2015): «Evolución, administración e impacto fiscal de los ingresos del cobre en Chile». Estudios de Finanzas Públicas de la Dirección de Presupuestos del Ministerio de Hacienda, Documento de Trabajo N 23.

To build the tables using the 2013 Chilean peso, we use the methodology proposed by the Central Bank of Chile based on the recommendations made by the European System of National Accounts.

Correa, V., Escandón, A., Luengo, R., and Venegas, J. (2002): «Empalme PIB: series anuales y trimestrales 1986–1995, Base 1996». BC Working Paper No 179.

APPENDIX B

TABLE B1: PUBLIC DEBT 1903-1910

TABLE B2: PUBLIC DEBT 1936-1943

TABLE B3: PUBLIC DEBT 1957-1964

TABLE B4: PUBLIC DEBT 2007-2014

TABLE B5: TAXATION 1903-1910 [2013 Chilean million pesos]

TABLE B6: TAXATION 1936-1943 [2013 Chilean million pesos]

TABLE B7: TAXATION 1957-1964 [2013 Chilean million pesos]

TABLE B8: TAXATION 2007-2014 [2013 Chilean million pesos]